- Locations and Hours

- UCLA Library

- Research Guides

- Research Tips and Tools

Advanced Research Methods

- Writing a Research Proposal

- What Is Research?

- Library Research

What Is a Research Proposal?

Reference books.

- Writing the Research Paper

- Presenting the Research Paper

When applying for a research grant or scholarship, or, just before you start a major research project, you may be asked to write a preliminary document that includes basic information about your future research. This is the information that is usually needed in your proposal:

- The topic and goal of the research project.

- The kind of result expected from the research.

- The theory or framework in which the research will be done and presented.

- What kind of methods will be used (statistical, empirical, etc.).

- Short reference on the preliminary scholarship and why your research project is needed; how will it continue/justify/disprove the previous scholarship.

- How much will the research project cost; how will it be budgeted (what for the money will be spent).

- Why is it you who can do this research and not somebody else.

Most agencies that offer scholarships or grants provide information about the required format of the proposal. It may include filling out templates, types of information they need, suggested/maximum length of the proposal, etc.

Research proposal formats vary depending on the size of the planned research, the number of participants, the discipline, the characteristics of the research, etc. The following outline assumes an individual researcher. This is just a SAMPLE; several other ways are equally good and can be successful. If possible, discuss your research proposal with an expert in writing, a professor, your colleague, another student who already wrote successful proposals, etc.

- Author, author's affiliation

- Explain the topic and why you chose it. If possible explain your goal/outcome of the research . How much time you need to complete the research?

- Give a brief summary of previous scholarship and explain why your topic and goals are important.

- Relate your planned research to previous scholarship. What will your research add to our knowledge of the topic.

- Break down the main topic into smaller research questions. List them one by one and explain why these questions need to be investigated. Relate them to previous scholarship.

- Include your hypothesis into the descriptions of the detailed research issues if you have one. Explain why it is important to justify your hypothesis.

- This part depends of the methods conducted in the research process. List the methods; explain how the results will be presented; how they will be assessed.

- Explain what kind of results will justify or disprove your hypothesis.

- Explain how much money you need.

- Explain the details of the budget (how much you want to spend for what).

- Describe why your research is important.

- List the sources you have used for writing the research proposal, including a few main citations of the preliminary scholarship.

- << Previous: Library Research

- Next: Writing the Research Paper >>

- Last Updated: May 16, 2024 10:20 AM

- URL: https://guides.library.ucla.edu/research-methods

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Research process

- How to Write a Research Proposal | Examples & Templates

How to Write a Research Proposal | Examples & Templates

Published on 30 October 2022 by Shona McCombes and Tegan George. Revised on 13 June 2023.

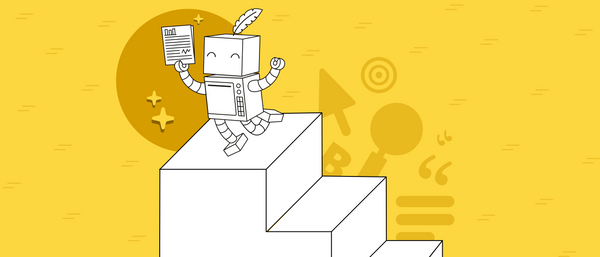

A research proposal describes what you will investigate, why it’s important, and how you will conduct your research.

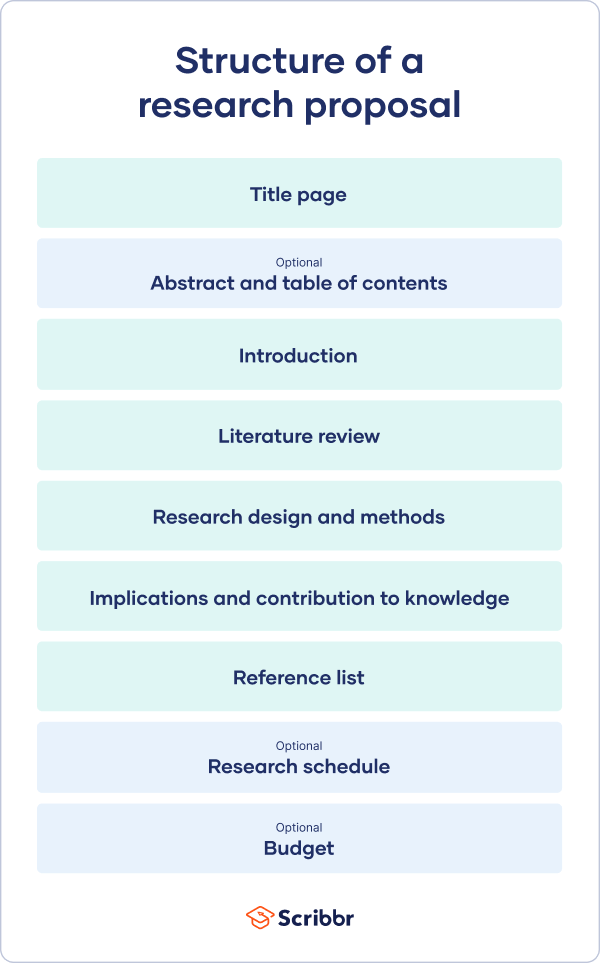

The format of a research proposal varies between fields, but most proposals will contain at least these elements:

Introduction

Literature review.

- Research design

Reference list

While the sections may vary, the overall objective is always the same. A research proposal serves as a blueprint and guide for your research plan, helping you get organised and feel confident in the path forward you choose to take.

Table of contents

Research proposal purpose, research proposal examples, research design and methods, contribution to knowledge, research schedule, frequently asked questions.

Academics often have to write research proposals to get funding for their projects. As a student, you might have to write a research proposal as part of a grad school application , or prior to starting your thesis or dissertation .

In addition to helping you figure out what your research can look like, a proposal can also serve to demonstrate why your project is worth pursuing to a funder, educational institution, or supervisor.

| Show your reader why your project is interesting, original, and important. | |

| Demonstrate your comfort and familiarity with your field. Show that you understand the current state of research on your topic. | |

| Make a case for your . Demonstrate that you have carefully thought about the data, tools, and procedures necessary to conduct your research. | |

| Confirm that your project is feasible within the timeline of your program or funding deadline. |

Research proposal length

The length of a research proposal can vary quite a bit. A bachelor’s or master’s thesis proposal can be just a few pages, while proposals for PhD dissertations or research funding are usually much longer and more detailed. Your supervisor can help you determine the best length for your work.

One trick to get started is to think of your proposal’s structure as a shorter version of your thesis or dissertation , only without the results , conclusion and discussion sections.

Download our research proposal template

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

Writing a research proposal can be quite challenging, but a good starting point could be to look at some examples. We’ve included a few for you below.

- Example research proposal #1: ‘A Conceptual Framework for Scheduling Constraint Management’

- Example research proposal #2: ‘ Medical Students as Mediators of Change in Tobacco Use’

Like your dissertation or thesis, the proposal will usually have a title page that includes:

- The proposed title of your project

- Your supervisor’s name

- Your institution and department

The first part of your proposal is the initial pitch for your project. Make sure it succinctly explains what you want to do and why.

Your introduction should:

- Introduce your topic

- Give necessary background and context

- Outline your problem statement and research questions

To guide your introduction , include information about:

- Who could have an interest in the topic (e.g., scientists, policymakers)

- How much is already known about the topic

- What is missing from this current knowledge

- What new insights your research will contribute

- Why you believe this research is worth doing

As you get started, it’s important to demonstrate that you’re familiar with the most important research on your topic. A strong literature review shows your reader that your project has a solid foundation in existing knowledge or theory. It also shows that you’re not simply repeating what other people have already done or said, but rather using existing research as a jumping-off point for your own.

In this section, share exactly how your project will contribute to ongoing conversations in the field by:

- Comparing and contrasting the main theories, methods, and debates

- Examining the strengths and weaknesses of different approaches

- Explaining how will you build on, challenge, or synthesise prior scholarship

Following the literature review, restate your main objectives . This brings the focus back to your own project. Next, your research design or methodology section will describe your overall approach, and the practical steps you will take to answer your research questions.

| ? or ? , , or research design? | |

| , )? ? | |

| , , , )? | |

| ? |

To finish your proposal on a strong note, explore the potential implications of your research for your field. Emphasise again what you aim to contribute and why it matters.

For example, your results might have implications for:

- Improving best practices

- Informing policymaking decisions

- Strengthening a theory or model

- Challenging popular or scientific beliefs

- Creating a basis for future research

Last but not least, your research proposal must include correct citations for every source you have used, compiled in a reference list . To create citations quickly and easily, you can use our free APA citation generator .

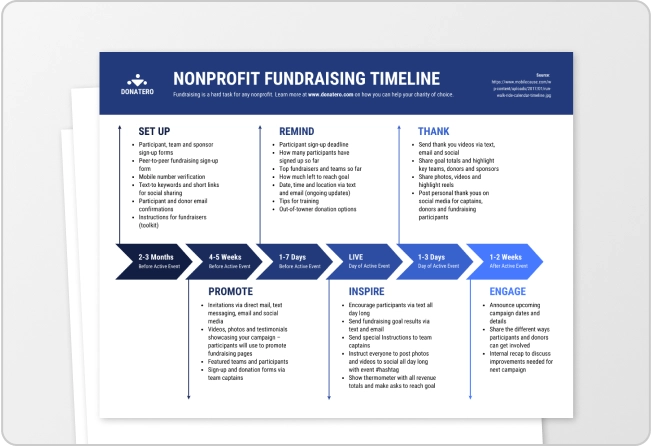

Some institutions or funders require a detailed timeline of the project, asking you to forecast what you will do at each stage and how long it may take. While not always required, be sure to check the requirements of your project.

Here’s an example schedule to help you get started. You can also download a template at the button below.

Download our research schedule template

| Research phase | Objectives | Deadline |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Background research and literature review | 20th January | |

| 2. Research design planning | and data analysis methods | 13th February |

| 3. Data collection and preparation | with selected participants and code interviews | 24th March |

| 4. Data analysis | of interview transcripts | 22nd April |

| 5. Writing | 17th June | |

| 6. Revision | final work | 28th July |

If you are applying for research funding, chances are you will have to include a detailed budget. This shows your estimates of how much each part of your project will cost.

Make sure to check what type of costs the funding body will agree to cover. For each item, include:

- Cost : exactly how much money do you need?

- Justification : why is this cost necessary to complete the research?

- Source : how did you calculate the amount?

To determine your budget, think about:

- Travel costs : do you need to go somewhere to collect your data? How will you get there, and how much time will you need? What will you do there (e.g., interviews, archival research)?

- Materials : do you need access to any tools or technologies?

- Help : do you need to hire any research assistants for the project? What will they do, and how much will you pay them?

Once you’ve decided on your research objectives , you need to explain them in your paper, at the end of your problem statement.

Keep your research objectives clear and concise, and use appropriate verbs to accurately convey the work that you will carry out for each one.

I will compare …

A research aim is a broad statement indicating the general purpose of your research project. It should appear in your introduction at the end of your problem statement , before your research objectives.

Research objectives are more specific than your research aim. They indicate the specific ways you’ll address the overarching aim.

A PhD, which is short for philosophiae doctor (doctor of philosophy in Latin), is the highest university degree that can be obtained. In a PhD, students spend 3–5 years writing a dissertation , which aims to make a significant, original contribution to current knowledge.

A PhD is intended to prepare students for a career as a researcher, whether that be in academia, the public sector, or the private sector.

A master’s is a 1- or 2-year graduate degree that can prepare you for a variety of careers.

All master’s involve graduate-level coursework. Some are research-intensive and intend to prepare students for further study in a PhD; these usually require their students to write a master’s thesis . Others focus on professional training for a specific career.

Critical thinking refers to the ability to evaluate information and to be aware of biases or assumptions, including your own.

Like information literacy , it involves evaluating arguments, identifying and solving problems in an objective and systematic way, and clearly communicating your ideas.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

McCombes, S. & George, T. (2023, June 13). How to Write a Research Proposal | Examples & Templates. Scribbr. Retrieved 18 June 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/the-research-process/research-proposal-explained/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, what is a research methodology | steps & tips, what is a literature review | guide, template, & examples, how to write a results section | tips & examples.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Dissertation

- What Is a Research Methodology? | Steps & Tips

What Is a Research Methodology? | Steps & Tips

Published on August 25, 2022 by Shona McCombes and Tegan George. Revised on November 20, 2023.

Your research methodology discusses and explains the data collection and analysis methods you used in your research. A key part of your thesis, dissertation , or research paper , the methodology chapter explains what you did and how you did it, allowing readers to evaluate the reliability and validity of your research and your dissertation topic .

It should include:

- The type of research you conducted

- How you collected and analyzed your data

- Any tools or materials you used in the research

- How you mitigated or avoided research biases

- Why you chose these methods

- Your methodology section should generally be written in the past tense .

- Academic style guides in your field may provide detailed guidelines on what to include for different types of studies.

- Your citation style might provide guidelines for your methodology section (e.g., an APA Style methods section ).

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

How to write a research methodology, why is a methods section important, step 1: explain your methodological approach, step 2: describe your data collection methods, step 3: describe your analysis method, step 4: evaluate and justify the methodological choices you made, tips for writing a strong methodology chapter, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about methodology.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

Your methods section is your opportunity to share how you conducted your research and why you chose the methods you chose. It’s also the place to show that your research was rigorously conducted and can be replicated .

It gives your research legitimacy and situates it within your field, and also gives your readers a place to refer to if they have any questions or critiques in other sections.

You can start by introducing your overall approach to your research. You have two options here.

Option 1: Start with your “what”

What research problem or question did you investigate?

- Aim to describe the characteristics of something?

- Explore an under-researched topic?

- Establish a causal relationship?

And what type of data did you need to achieve this aim?

- Quantitative data , qualitative data , or a mix of both?

- Primary data collected yourself, or secondary data collected by someone else?

- Experimental data gathered by controlling and manipulating variables, or descriptive data gathered via observations?

Option 2: Start with your “why”

Depending on your discipline, you can also start with a discussion of the rationale and assumptions underpinning your methodology. In other words, why did you choose these methods for your study?

- Why is this the best way to answer your research question?

- Is this a standard methodology in your field, or does it require justification?

- Were there any ethical considerations involved in your choices?

- What are the criteria for validity and reliability in this type of research ? How did you prevent bias from affecting your data?

Once you have introduced your reader to your methodological approach, you should share full details about your data collection methods .

Quantitative methods

In order to be considered generalizable, you should describe quantitative research methods in enough detail for another researcher to replicate your study.

Here, explain how you operationalized your concepts and measured your variables. Discuss your sampling method or inclusion and exclusion criteria , as well as any tools, procedures, and materials you used to gather your data.

Surveys Describe where, when, and how the survey was conducted.

- How did you design the questionnaire?

- What form did your questions take (e.g., multiple choice, Likert scale )?

- Were your surveys conducted in-person or virtually?

- What sampling method did you use to select participants?

- What was your sample size and response rate?

Experiments Share full details of the tools, techniques, and procedures you used to conduct your experiment.

- How did you design the experiment ?

- How did you recruit participants?

- How did you manipulate and measure the variables ?

- What tools did you use?

Existing data Explain how you gathered and selected the material (such as datasets or archival data) that you used in your analysis.

- Where did you source the material?

- How was the data originally produced?

- What criteria did you use to select material (e.g., date range)?

The survey consisted of 5 multiple-choice questions and 10 questions measured on a 7-point Likert scale.

The goal was to collect survey responses from 350 customers visiting the fitness apparel company’s brick-and-mortar location in Boston on July 4–8, 2022, between 11:00 and 15:00.

Here, a customer was defined as a person who had purchased a product from the company on the day they took the survey. Participants were given 5 minutes to fill in the survey anonymously. In total, 408 customers responded, but not all surveys were fully completed. Due to this, 371 survey results were included in the analysis.

- Information bias

- Omitted variable bias

- Regression to the mean

- Survivorship bias

- Undercoverage bias

- Sampling bias

Qualitative methods

In qualitative research , methods are often more flexible and subjective. For this reason, it’s crucial to robustly explain the methodology choices you made.

Be sure to discuss the criteria you used to select your data, the context in which your research was conducted, and the role you played in collecting your data (e.g., were you an active participant, or a passive observer?)

Interviews or focus groups Describe where, when, and how the interviews were conducted.

- How did you find and select participants?

- How many participants took part?

- What form did the interviews take ( structured , semi-structured , or unstructured )?

- How long were the interviews?

- How were they recorded?

Participant observation Describe where, when, and how you conducted the observation or ethnography .

- What group or community did you observe? How long did you spend there?

- How did you gain access to this group? What role did you play in the community?

- How long did you spend conducting the research? Where was it located?

- How did you record your data (e.g., audiovisual recordings, note-taking)?

Existing data Explain how you selected case study materials for your analysis.

- What type of materials did you analyze?

- How did you select them?

In order to gain better insight into possibilities for future improvement of the fitness store’s product range, semi-structured interviews were conducted with 8 returning customers.

Here, a returning customer was defined as someone who usually bought products at least twice a week from the store.

Surveys were used to select participants. Interviews were conducted in a small office next to the cash register and lasted approximately 20 minutes each. Answers were recorded by note-taking, and seven interviews were also filmed with consent. One interviewee preferred not to be filmed.

- The Hawthorne effect

- Observer bias

- The placebo effect

- Response bias and Nonresponse bias

- The Pygmalion effect

- Recall bias

- Social desirability bias

- Self-selection bias

Mixed methods

Mixed methods research combines quantitative and qualitative approaches. If a standalone quantitative or qualitative study is insufficient to answer your research question, mixed methods may be a good fit for you.

Mixed methods are less common than standalone analyses, largely because they require a great deal of effort to pull off successfully. If you choose to pursue mixed methods, it’s especially important to robustly justify your methods.

Don't submit your assignments before you do this

The academic proofreading tool has been trained on 1000s of academic texts. Making it the most accurate and reliable proofreading tool for students. Free citation check included.

Try for free

Next, you should indicate how you processed and analyzed your data. Avoid going into too much detail: you should not start introducing or discussing any of your results at this stage.

In quantitative research , your analysis will be based on numbers. In your methods section, you can include:

- How you prepared the data before analyzing it (e.g., checking for missing data , removing outliers , transforming variables)

- Which software you used (e.g., SPSS, Stata or R)

- Which statistical tests you used (e.g., two-tailed t test , simple linear regression )

In qualitative research, your analysis will be based on language, images, and observations (often involving some form of textual analysis ).

Specific methods might include:

- Content analysis : Categorizing and discussing the meaning of words, phrases and sentences

- Thematic analysis : Coding and closely examining the data to identify broad themes and patterns

- Discourse analysis : Studying communication and meaning in relation to their social context

Mixed methods combine the above two research methods, integrating both qualitative and quantitative approaches into one coherent analytical process.

Above all, your methodology section should clearly make the case for why you chose the methods you did. This is especially true if you did not take the most standard approach to your topic. In this case, discuss why other methods were not suitable for your objectives, and show how this approach contributes new knowledge or understanding.

In any case, it should be overwhelmingly clear to your reader that you set yourself up for success in terms of your methodology’s design. Show how your methods should lead to results that are valid and reliable, while leaving the analysis of the meaning, importance, and relevance of your results for your discussion section .

- Quantitative: Lab-based experiments cannot always accurately simulate real-life situations and behaviors, but they are effective for testing causal relationships between variables .

- Qualitative: Unstructured interviews usually produce results that cannot be generalized beyond the sample group , but they provide a more in-depth understanding of participants’ perceptions, motivations, and emotions.

- Mixed methods: Despite issues systematically comparing differing types of data, a solely quantitative study would not sufficiently incorporate the lived experience of each participant, while a solely qualitative study would be insufficiently generalizable.

Remember that your aim is not just to describe your methods, but to show how and why you applied them. Again, it’s critical to demonstrate that your research was rigorously conducted and can be replicated.

1. Focus on your objectives and research questions

The methodology section should clearly show why your methods suit your objectives and convince the reader that you chose the best possible approach to answering your problem statement and research questions .

2. Cite relevant sources

Your methodology can be strengthened by referencing existing research in your field. This can help you to:

- Show that you followed established practice for your type of research

- Discuss how you decided on your approach by evaluating existing research

- Present a novel methodological approach to address a gap in the literature

3. Write for your audience

Consider how much information you need to give, and avoid getting too lengthy. If you are using methods that are standard for your discipline, you probably don’t need to give a lot of background or justification.

Regardless, your methodology should be a clear, well-structured text that makes an argument for your approach, not just a list of technical details and procedures.

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Normal distribution

- Measures of central tendency

- Chi square tests

- Confidence interval

- Quartiles & Quantiles

Methodology

- Cluster sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Thematic analysis

- Cohort study

- Peer review

- Ethnography

Research bias

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Conformity bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Availability heuristic

- Attrition bias

Methodology refers to the overarching strategy and rationale of your research project . It involves studying the methods used in your field and the theories or principles behind them, in order to develop an approach that matches your objectives.

Methods are the specific tools and procedures you use to collect and analyze data (for example, experiments, surveys , and statistical tests ).

In shorter scientific papers, where the aim is to report the findings of a specific study, you might simply describe what you did in a methods section .

In a longer or more complex research project, such as a thesis or dissertation , you will probably include a methodology section , where you explain your approach to answering the research questions and cite relevant sources to support your choice of methods.

In a scientific paper, the methodology always comes after the introduction and before the results , discussion and conclusion . The same basic structure also applies to a thesis, dissertation , or research proposal .

Depending on the length and type of document, you might also include a literature review or theoretical framework before the methodology.

Quantitative research deals with numbers and statistics, while qualitative research deals with words and meanings.

Quantitative methods allow you to systematically measure variables and test hypotheses . Qualitative methods allow you to explore concepts and experiences in more detail.

Reliability and validity are both about how well a method measures something:

- Reliability refers to the consistency of a measure (whether the results can be reproduced under the same conditions).

- Validity refers to the accuracy of a measure (whether the results really do represent what they are supposed to measure).

If you are doing experimental research, you also have to consider the internal and external validity of your experiment.

A sample is a subset of individuals from a larger population . Sampling means selecting the group that you will actually collect data from in your research. For example, if you are researching the opinions of students in your university, you could survey a sample of 100 students.

In statistics, sampling allows you to test a hypothesis about the characteristics of a population.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. & George, T. (2023, November 20). What Is a Research Methodology? | Steps & Tips. Scribbr. Retrieved June 19, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/dissertation/methodology/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, what is a theoretical framework | guide to organizing, what is a research design | types, guide & examples, qualitative vs. quantitative research | differences, examples & methods, get unlimited documents corrected.

✔ Free APA citation check included ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

Research Proposal Example/Sample

Detailed Walkthrough + Free Proposal Template

If you’re getting started crafting your research proposal and are looking for a few examples of research proposals , you’ve come to the right place.

In this video, we walk you through two successful (approved) research proposals , one for a Master’s-level project, and one for a PhD-level dissertation. We also start off by unpacking our free research proposal template and discussing the four core sections of a research proposal, so that you have a clear understanding of the basics before diving into the actual proposals.

- Research proposal example/sample – Master’s-level (PDF/Word)

- Research proposal example/sample – PhD-level (PDF/Word)

- Proposal template (Fully editable)

If you’re working on a research proposal for a dissertation or thesis, you may also find the following useful:

- Research Proposal Bootcamp : Learn how to write a research proposal as efficiently and effectively as possible

- 1:1 Proposal Coaching : Get hands-on help with your research proposal

PS – If you’re working on a dissertation, be sure to also check out our collection of dissertation and thesis examples here .

FAQ: Research Proposal Example

Research proposal example: frequently asked questions, are the sample proposals real.

Yes. The proposals are real and were approved by the respective universities.

Can I copy one of these proposals for my own research?

As we discuss in the video, every research proposal will be slightly different, depending on the university’s unique requirements, as well as the nature of the research itself. Therefore, you’ll need to tailor your research proposal to suit your specific context.

You can learn more about the basics of writing a research proposal here .

How do I get the research proposal template?

You can access our free proposal template here .

Is the proposal template really free?

Yes. There is no cost for the proposal template and you are free to use it as a foundation for your research proposal.

Where can I learn more about proposal writing?

For self-directed learners, our Research Proposal Bootcamp is a great starting point.

For students that want hands-on guidance, our private coaching service is recommended.

Psst… there’s more!

This post is an extract from our bestselling short course, Research Proposal Bootcamp . If you want to work smart, you don't want to miss this .

You Might Also Like:

10 Comments

I am at the stage of writing my thesis proposal for a PhD in Management at Altantic International University. I checked on the coaching services, but it indicates that it’s not available in my area. I am in South Sudan. My proposed topic is: “Leadership Behavior in Local Government Governance Ecosystem and Service Delivery Effectiveness in Post Conflict Districts of Northern Uganda”. I will appreciate your guidance and support

GRADCOCH is very grateful motivated and helpful for all students etc. it is very accorporated and provide easy access way strongly agree from GRADCOCH.

Proposal research departemet management

I am at the stage of writing my thesis proposal for a masters in Analysis of w heat commercialisation by small holders householdrs at Hawassa International University. I will appreciate your guidance and support

please provide a attractive proposal about foreign universities .It would be your highness.

comparative constitutional law

Kindly guide me through writing a good proposal on the thesis topic; Impact of Artificial Intelligence on Financial Inclusion in Nigeria. Thank you

Kindly help me write a research proposal on the topic of impacts of artisanal gold panning on the environment

I am in the process of research proposal for my Master of Art with a topic : “factors influence on first-year students’s academic adjustment”. I am absorbing in GRADCOACH and interested in such proposal sample. However, it is great for me to learn and seeking for more new updated proposal framework from GRADCAOCH.

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

We use essential cookies to make Venngage work. By clicking “Accept All Cookies”, you agree to the storing of cookies on your device to enhance site navigation, analyze site usage, and assist in our marketing efforts.

Manage Cookies

Cookies and similar technologies collect certain information about how you’re using our website. Some of them are essential, and without them you wouldn’t be able to use Venngage. But others are optional, and you get to choose whether we use them or not.

Strictly Necessary Cookies

These cookies are always on, as they’re essential for making Venngage work, and making it safe. Without these cookies, services you’ve asked for can’t be provided.

Show cookie providers

- Google Login

Functionality Cookies

These cookies help us provide enhanced functionality and personalisation, and remember your settings. They may be set by us or by third party providers.

Performance Cookies

These cookies help us analyze how many people are using Venngage, where they come from and how they're using it. If you opt out of these cookies, we can’t get feedback to make Venngage better for you and all our users.

- Google Analytics

Targeting Cookies

These cookies are set by our advertising partners to track your activity and show you relevant Venngage ads on other sites as you browse the internet.

- Google Tag Manager

- Infographics

- Daily Infographics

- Popular Templates

- Accessibility

- Graphic Design

- Graphs and Charts

- Data Visualization

- Human Resources

- Beginner Guides

Blog Business How to Write a Research Proposal: A Step-by-Step

How to Write a Research Proposal: A Step-by-Step

Written by: Danesh Ramuthi Nov 29, 2023

A research proposal is a structured outline for a planned study on a specific topic. It serves as a roadmap, guiding researchers through the process of converting their research idea into a feasible project.

The aim of a research proposal is multifold: it articulates the research problem, establishes a theoretical framework, outlines the research methodology and highlights the potential significance of the study. Importantly, it’s a critical tool for scholars seeking grant funding or approval for their research projects.

Crafting a good research proposal requires not only understanding your research topic and methodological approaches but also the ability to present your ideas clearly and persuasively. Explore Venngage’s Proposal Maker and Research Proposals Templates to begin your journey in writing a compelling research proposal.

What to include in a research proposal?

In a research proposal, include a clear statement of your research question or problem, along with an explanation of its significance. This should be followed by a literature review that situates your proposed study within the context of existing research.

Your proposal should also outline the research methodology, detailing how you plan to conduct your study, including data collection and analysis methods.

Additionally, include a theoretical framework that guides your research approach, a timeline or research schedule, and a budget if applicable. It’s important to also address the anticipated outcomes and potential implications of your study. A well-structured research proposal will clearly communicate your research objectives, methods and significance to the readers.

How to format a research proposal?

Formatting a research proposal involves adhering to a structured outline to ensure clarity and coherence. While specific requirements may vary, a standard research proposal typically includes the following elements:

- Title Page: Must include the title of your research proposal, your name and affiliations. The title should be concise and descriptive of your proposed research.

- Abstract: A brief summary of your proposal, usually not exceeding 250 words. It should highlight the research question, methodology and the potential impact of the study.

- Introduction: Introduces your research question or problem, explains its significance, and states the objectives of your study.

- Literature review: Here, you contextualize your research within existing scholarship, demonstrating your knowledge of the field and how your research will contribute to it.

- Methodology: Outline your research methods, including how you will collect and analyze data. This section should be detailed enough to show the feasibility and thoughtfulness of your approach.

- Timeline: Provide an estimated schedule for your research, breaking down the process into stages with a realistic timeline for each.

- Budget (if applicable): If your research requires funding, include a detailed budget outlining expected cost.

- References/Bibliography: List all sources referenced in your proposal in a consistent citation style.

How to write a research proposal in 11 steps?

Writing a research proposal template in structured steps ensures a comprehensive and coherent presentation of your research project. Let’s look at the explanation for each of the steps here:

Step 1: Title and Abstract Step 2: Introduction Step 3: Research objectives Step 4: Literature review Step 5: Methodology Step 6: Timeline Step 7: Resources Step 8: Ethical considerations Step 9: Expected outcomes and significance Step 10: References Step 11: Appendices

Step 1: title and abstract.

Select a concise, descriptive title and write an abstract summarizing your research question, objectives, methodology and expected outcomes. The abstract should include your research question, the objectives you aim to achieve, the methodology you plan to employ and the anticipated outcomes.

Step 2: Introduction

In this section, introduce the topic of your research, emphasizing its significance and relevance to the field. Articulate the research problem or question in clear terms and provide background context, which should include an overview of previous research in the field.

Step 3: Research objectives

Here, you’ll need to outline specific, clear and achievable objectives that align with your research problem. These objectives should be well-defined, focused and measurable, serving as the guiding pillars for your study. They help in establishing what you intend to accomplish through your research and provide a clear direction for your investigation.

Step 4: Literature review

In this part, conduct a thorough review of existing literature related to your research topic. This involves a detailed summary of key findings and major contributions from previous research. Identify existing gaps in the literature and articulate how your research aims to fill these gaps. The literature review not only shows your grasp of the subject matter but also how your research will contribute new insights or perspectives to the field.

Step 5: Methodology

Describe the design of your research and the methodologies you will employ. This should include detailed information on data collection methods, instruments to be used and analysis techniques. Justify the appropriateness of these methods for your research.

Step 6: Timeline

Construct a detailed timeline that maps out the major milestones and activities of your research project. Break the entire research process into smaller, manageable tasks and assign realistic time frames to each. This timeline should cover everything from the initial research phase to the final submission, including periods for data collection, analysis and report writing.

It helps in ensuring your project stays on track and demonstrates to reviewers that you have a well-thought-out plan for completing your research efficiently.

Step 7: Resources

Identify all the resources that will be required for your research, such as specific databases, laboratory equipment, software or funding. Provide details on how these resources will be accessed or acquired.

If your research requires funding, explain how it will be utilized effectively to support various aspects of the project.

Step 8: Ethical considerations

Address any ethical issues that may arise during your research. This is particularly important for research involving human subjects. Describe the measures you will take to ensure ethical standards are maintained, such as obtaining informed consent, ensuring participant privacy, and adhering to data protection regulations.

Here, in this section you should reassure reviewers that you are committed to conducting your research responsibly and ethically.

Step 9: Expected outcomes and significance

Articulate the expected outcomes or results of your research. Explain the potential impact and significance of these outcomes, whether in advancing academic knowledge, influencing policy or addressing specific societal or practical issues.

Step 10: References

Compile a comprehensive list of all the references cited in your proposal. Adhere to a consistent citation style (like APA or MLA) throughout your document. The reference section not only gives credit to the original authors of your sourced information but also strengthens the credibility of your proposal.

Step 11: Appendices

Include additional supporting materials that are pertinent to your research proposal. This can be survey questionnaires, interview guides, detailed data analysis plans or any supplementary information that supports the main text.

Appendices provide further depth to your proposal, showcasing the thoroughness of your preparation.

Research proposal FAQs

1. how long should a research proposal be.

The length of a research proposal can vary depending on the requirements of the academic institution, funding body or specific guidelines provided. Generally, research proposals range from 500 to 1500 words or about one to a few pages long. It’s important to provide enough detail to clearly convey your research idea, objectives and methodology, while being concise. Always check

2. Why is the research plan pivotal to a research project?

The research plan is pivotal to a research project because it acts as a blueprint, guiding every phase of the study. It outlines the objectives, methodology, timeline and expected outcomes, providing a structured approach and ensuring that the research is systematically conducted.

A well-crafted plan helps in identifying potential challenges, allocating resources efficiently and maintaining focus on the research goals. It is also essential for communicating the project’s feasibility and importance to stakeholders, such as funding bodies or academic supervisors.

Mastering how to write a research proposal is an essential skill for any scholar, whether in social and behavioral sciences, academic writing or any field requiring scholarly research. From this article, you have learned key components, from the literature review to the research design, helping you develop a persuasive and well-structured proposal.

Remember, a good research proposal not only highlights your proposed research and methodology but also demonstrates its relevance and potential impact.

For additional support, consider utilizing Venngage’s Proposal Maker and Research Proposals Templates , valuable tools in crafting a compelling proposal that stands out.

Whether it’s for grant funding, a research paper or a dissertation proposal, these resources can assist in transforming your research idea into a successful submission.

Discover popular designs

Infographic maker

Brochure maker

White paper online

Newsletter creator

Flyer maker

Timeline maker

Letterhead maker

Mind map maker

Ebook maker

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Chapter 14: The Research Proposal

14.3 Components of a Research Proposal

Krathwohl (2005) suggests and describes a variety of components to include in a research proposal. The following sections – Introductions, Background and significance, Literature Review; Research design and methods, Preliminary suppositions and implications; and Conclusion present these components in a suggested template for you to follow in the preparation of your research proposal.

Introduction

The introduction sets the tone for what follows in your research proposal – treat it as the initial pitch of your idea. After reading the introduction your reader should:

- understand what it is you want to do;

- have a sense of your passion for the topic; and

- be excited about the study’s possible outcomes.

As you begin writing your research proposal, it is helpful to think of the introduction as a narrative of what it is you want to do, written in one to three paragraphs. Within those one to three paragraphs, it is important to briefly answer the following questions:

- What is the central research problem?

- How is the topic of your research proposal related to the problem?

- What methods will you utilize to analyze the research problem?

- Why is it important to undertake this research? What is the significance of your proposed research? Why are the outcomes of your proposed research important? Whom are they important?

Note : You may be asked by your instructor to include an abstract with your research proposal. In such cases, an abstract should provide an overview of what it is you plan to study, your main research question, a brief explanation of your methods to answer the research question, and your expected findings. All of this information must be carefully crafted in 150 to 250 words. A word of advice is to save the writing of your abstract until the very end of your research proposal preparation. If you are asked to provide an abstract, you should include 5 to 7 key words that are of most relevance to your study. List these in order of relevance.

Background and significance

The purpose of this section is to explain the context of your proposal and to describe, in detail, why it is important to undertake this research. Assume that the person or people who will read your research proposal know nothing or very little about the research problem. While you do not need to include all knowledge you have learned about your topic in this section, it is important to ensure that you include the most relevant material that will help to explain the goals of your research.

While there are no hard and fast rules, you should attempt to address some or all of the following key points:

- State the research problem and provide a more thorough explanation about the purpose of the study than what you stated in the introduction.

- Present the rationale for the proposed research study. Clearly indicate why this research is worth doing. Answer the “so what?” question.

- Describe the major issues or problems to be addressed by your research. Do not forget to explain how and in what ways your proposed research builds upon previous related research.

- Explain how you plan to go about conducting your research.

- Clearly identify the key or most relevant sources of research you intend to use and explain how they will contribute to your analysis of the topic.

- Set the boundaries of your proposed research, in order to provide a clear focus. Where appropriate, state not only what you will study, but what will be excluded from your study.

- Provide clear definitions of key concepts and terms. Since key concepts and terms often have numerous definitions, make sure you state which definition you will be utilizing in your research.

Literature review

This key component of the research proposal is the most time-consuming aspect in the preparation of your research proposal. As described in Chapter 5 , the literature review provides the background to your study and demonstrates the significance of the proposed research. Specifically, it is a review and synthesis of prior research that is related to the problem you are setting forth to investigate. Essentially, your goal in the literature review is to place your research study within the larger whole of what has been studied in the past, while demonstrating to your reader that your work is original, innovative, and adds to the larger whole.

As the literature review is information dense, it is essential that this section be intelligently structured to enable your reader to grasp the key arguments underpinning your study. However, this can be easier to state and harder to do, simply due to the fact there is usually a plethora of related research to sift through. Consequently, a good strategy for writing the literature review is to break the literature into conceptual categories or themes, rather than attempting to describe various groups of literature you reviewed. Chapter 5 describes a variety of methods to help you organize the themes.

Here are some suggestions on how to approach the writing of your literature review:

- Think about what questions other researchers have asked, what methods they used, what they found, and what they recommended based upon their findings.

- Do not be afraid to challenge previous related research findings and/or conclusions.

- Assess what you believe to be missing from previous research and explain how your research fills in this gap and/or extends previous research.

It is important to note that a significant challenge related to undertaking a literature review is knowing when to stop. As such, it is important to know when you have uncovered the key conceptual categories underlying your research topic. Generally, when you start to see repetition in the conclusions or recommendations, you can have confidence that you have covered all of the significant conceptual categories in your literature review. However, it is also important to acknowledge that researchers often find themselves returning to the literature as they collect and analyze their data. For example, an unexpected finding may develop as you collect and/or analyze the data; in this case, it is important to take the time to step back and review the literature again, to ensure that no other researchers have found a similar finding. This may include looking to research outside your field.

This situation occurred with one of this textbook’s authors’ research related to community resilience. During the interviews, the researchers heard many participants discuss individual resilience factors and how they believed these individual factors helped make the community more resilient, overall. Sheppard and Williams (2016) had not discovered these individual factors in their original literature review on community and environmental resilience. However, when they returned to the literature to search for individual resilience factors, they discovered a small body of literature in the child and youth psychology field. Consequently, Sheppard and Williams had to go back and add a new section to their literature review on individual resilience factors. Interestingly, their research appeared to be the first research to link individual resilience factors with community resilience factors.

Research design and methods

The objective of this section of the research proposal is to convince the reader that your overall research design and methods of analysis will enable you to solve the research problem you have identified and also enable you to accurately and effectively interpret the results of your research. Consequently, it is critical that the research design and methods section is well-written, clear, and logically organized. This demonstrates to your reader that you know what you are going to do and how you are going to do it. Overall, you want to leave your reader feeling confident that you have what it takes to get this research study completed in a timely fashion.

Essentially, this section of the research proposal should be clearly tied to the specific objectives of your study; however, it is also important to draw upon and include examples from the literature review that relate to your design and intended methods. In other words, you must clearly demonstrate how your study utilizes and builds upon past studies, as it relates to the research design and intended methods. For example, what methods have been used by other researchers in similar studies?

While it is important to consider the methods that other researchers have employed, it is equally, if not more, important to consider what methods have not been but could be employed. Remember, the methods section is not simply a list of tasks to be undertaken. It is also an argument as to why and how the tasks you have outlined will help you investigate the research problem and answer your research question(s).

Tips for writing the research design and methods section:

Specify the methodological approaches you intend to employ to obtain information and the techniques you will use to analyze the data.

Specify the research operations you will undertake and the way you will interpret the results of those operations in relation to the research problem.

Go beyond stating what you hope to achieve through the methods you have chosen. State how you will actually implement the methods (i.e., coding interview text, running regression analysis, etc.).

Anticipate and acknowledge any potential barriers you may encounter when undertaking your research, and describe how you will address these barriers.

Explain where you believe you will find challenges related to data collection, including access to participants and information.

Preliminary suppositions and implications

The purpose of this section is to argue how you anticipate that your research will refine, revise, or extend existing knowledge in the area of your study. Depending upon the aims and objectives of your study, you should also discuss how your anticipated findings may impact future research. For example, is it possible that your research may lead to a new policy, theoretical understanding, or method for analyzing data? How might your study influence future studies? What might your study mean for future practitioners working in the field? Who or what might benefit from your study? How might your study contribute to social, economic or environmental issues? While it is important to think about and discuss possibilities such as these, it is equally important to be realistic in stating your anticipated findings. In other words, you do not want to delve into idle speculation. Rather, the purpose here is to reflect upon gaps in the current body of literature and to describe how you anticipate your research will begin to fill in some or all of those gaps.

The conclusion reiterates the importance and significance of your research proposal, and provides a brief summary of the entire proposed study. Essentially, this section should only be one or two paragraphs in length. Here is a potential outline for your conclusion:

Discuss why the study should be done. Specifically discuss how you expect your study will advance existing knowledge and how your study is unique.

Explain the specific purpose of the study and the research questions that the study will answer.

Explain why the research design and methods chosen for this study are appropriate, and why other designs and methods were not chosen.

State the potential implications you expect to emerge from your proposed study,

Provide a sense of how your study fits within the broader scholarship currently in existence, related to the research problem.

Citations and references

As with any scholarly research paper, you must cite the sources you used in composing your research proposal. In a research proposal, this can take two forms: a reference list or a bibliography. A reference list lists the literature you referenced in the body of your research proposal. All references in the reference list must appear in the body of the research proposal. Remember, it is not acceptable to say “as cited in …” As a researcher you must always go to the original source and check it for yourself. Many errors are made in referencing, even by top researchers, and so it is important not to perpetuate an error made by someone else. While this can be time consuming, it is the proper way to undertake a literature review.

In contrast, a bibliography , is a list of everything you used or cited in your research proposal, with additional citations to any key sources relevant to understanding the research problem. In other words, sources cited in your bibliography may not necessarily appear in the body of your research proposal. Make sure you check with your instructor to see which of the two you are expected to produce.

Overall, your list of citations should be a testament to the fact that you have done a sufficient level of preliminary research to ensure that your project will complement, but not duplicate, previous research efforts. For social sciences, the reference list or bibliography should be prepared in American Psychological Association (APA) referencing format. Usually, the reference list (or bibliography) is not included in the word count of the research proposal. Again, make sure you check with your instructor to confirm.

Research Methods for the Social Sciences: An Introduction Copyright © 2020 by Valerie Sheppard is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Indian J Anaesth

- v.60(9); 2016 Sep

How to write a research proposal?

Department of Anaesthesiology, Bangalore Medical College and Research Institute, Bengaluru, Karnataka, India

Devika Rani Duggappa

Writing the proposal of a research work in the present era is a challenging task due to the constantly evolving trends in the qualitative research design and the need to incorporate medical advances into the methodology. The proposal is a detailed plan or ‘blueprint’ for the intended study, and once it is completed, the research project should flow smoothly. Even today, many of the proposals at post-graduate evaluation committees and application proposals for funding are substandard. A search was conducted with keywords such as research proposal, writing proposal and qualitative using search engines, namely, PubMed and Google Scholar, and an attempt has been made to provide broad guidelines for writing a scientifically appropriate research proposal.

INTRODUCTION

A clean, well-thought-out proposal forms the backbone for the research itself and hence becomes the most important step in the process of conduct of research.[ 1 ] The objective of preparing a research proposal would be to obtain approvals from various committees including ethics committee [details under ‘Research methodology II’ section [ Table 1 ] in this issue of IJA) and to request for grants. However, there are very few universally accepted guidelines for preparation of a good quality research proposal. A search was performed with keywords such as research proposal, funding, qualitative and writing proposals using search engines, namely, PubMed, Google Scholar and Scopus.

Five ‘C’s while writing a literature review

BASIC REQUIREMENTS OF A RESEARCH PROPOSAL

A proposal needs to show how your work fits into what is already known about the topic and what new paradigm will it add to the literature, while specifying the question that the research will answer, establishing its significance, and the implications of the answer.[ 2 ] The proposal must be capable of convincing the evaluation committee about the credibility, achievability, practicality and reproducibility (repeatability) of the research design.[ 3 ] Four categories of audience with different expectations may be present in the evaluation committees, namely academic colleagues, policy-makers, practitioners and lay audiences who evaluate the research proposal. Tips for preparation of a good research proposal include; ‘be practical, be persuasive, make broader links, aim for crystal clarity and plan before you write’. A researcher must be balanced, with a realistic understanding of what can be achieved. Being persuasive implies that researcher must be able to convince other researchers, research funding agencies, educational institutions and supervisors that the research is worth getting approval. The aim of the researcher should be clearly stated in simple language that describes the research in a way that non-specialists can comprehend, without use of jargons. The proposal must not only demonstrate that it is based on an intelligent understanding of the existing literature but also show that the writer has thought about the time needed to conduct each stage of the research.[ 4 , 5 ]

CONTENTS OF A RESEARCH PROPOSAL

The contents or formats of a research proposal vary depending on the requirements of evaluation committee and are generally provided by the evaluation committee or the institution.

In general, a cover page should contain the (i) title of the proposal, (ii) name and affiliation of the researcher (principal investigator) and co-investigators, (iii) institutional affiliation (degree of the investigator and the name of institution where the study will be performed), details of contact such as phone numbers, E-mail id's and lines for signatures of investigators.

The main contents of the proposal may be presented under the following headings: (i) introduction, (ii) review of literature, (iii) aims and objectives, (iv) research design and methods, (v) ethical considerations, (vi) budget, (vii) appendices and (viii) citations.[ 4 ]

Introduction

It is also sometimes termed as ‘need for study’ or ‘abstract’. Introduction is an initial pitch of an idea; it sets the scene and puts the research in context.[ 6 ] The introduction should be designed to create interest in the reader about the topic and proposal. It should convey to the reader, what you want to do, what necessitates the study and your passion for the topic.[ 7 ] Some questions that can be used to assess the significance of the study are: (i) Who has an interest in the domain of inquiry? (ii) What do we already know about the topic? (iii) What has not been answered adequately in previous research and practice? (iv) How will this research add to knowledge, practice and policy in this area? Some of the evaluation committees, expect the last two questions, elaborated under a separate heading of ‘background and significance’.[ 8 ] Introduction should also contain the hypothesis behind the research design. If hypothesis cannot be constructed, the line of inquiry to be used in the research must be indicated.

Review of literature

It refers to all sources of scientific evidence pertaining to the topic in interest. In the present era of digitalisation and easy accessibility, there is an enormous amount of relevant data available, making it a challenge for the researcher to include all of it in his/her review.[ 9 ] It is crucial to structure this section intelligently so that the reader can grasp the argument related to your study in relation to that of other researchers, while still demonstrating to your readers that your work is original and innovative. It is preferable to summarise each article in a paragraph, highlighting the details pertinent to the topic of interest. The progression of review can move from the more general to the more focused studies, or a historical progression can be used to develop the story, without making it exhaustive.[ 1 ] Literature should include supporting data, disagreements and controversies. Five ‘C's may be kept in mind while writing a literature review[ 10 ] [ Table 1 ].

Aims and objectives

The research purpose (or goal or aim) gives a broad indication of what the researcher wishes to achieve in the research. The hypothesis to be tested can be the aim of the study. The objectives related to parameters or tools used to achieve the aim are generally categorised as primary and secondary objectives.

Research design and method

The objective here is to convince the reader that the overall research design and methods of analysis will correctly address the research problem and to impress upon the reader that the methodology/sources chosen are appropriate for the specific topic. It should be unmistakably tied to the specific aims of your study.

In this section, the methods and sources used to conduct the research must be discussed, including specific references to sites, databases, key texts or authors that will be indispensable to the project. There should be specific mention about the methodological approaches to be undertaken to gather information, about the techniques to be used to analyse it and about the tests of external validity to which researcher is committed.[ 10 , 11 ]

The components of this section include the following:[ 4 ]

Population and sample

Population refers to all the elements (individuals, objects or substances) that meet certain criteria for inclusion in a given universe,[ 12 ] and sample refers to subset of population which meets the inclusion criteria for enrolment into the study. The inclusion and exclusion criteria should be clearly defined. The details pertaining to sample size are discussed in the article “Sample size calculation: Basic priniciples” published in this issue of IJA.

Data collection

The researcher is expected to give a detailed account of the methodology adopted for collection of data, which include the time frame required for the research. The methodology should be tested for its validity and ensure that, in pursuit of achieving the results, the participant's life is not jeopardised. The author should anticipate and acknowledge any potential barrier and pitfall in carrying out the research design and explain plans to address them, thereby avoiding lacunae due to incomplete data collection. If the researcher is planning to acquire data through interviews or questionnaires, copy of the questions used for the same should be attached as an annexure with the proposal.

Rigor (soundness of the research)

This addresses the strength of the research with respect to its neutrality, consistency and applicability. Rigor must be reflected throughout the proposal.

It refers to the robustness of a research method against bias. The author should convey the measures taken to avoid bias, viz. blinding and randomisation, in an elaborate way, thus ensuring that the result obtained from the adopted method is purely as chance and not influenced by other confounding variables.

Consistency

Consistency considers whether the findings will be consistent if the inquiry was replicated with the same participants and in a similar context. This can be achieved by adopting standard and universally accepted methods and scales.

Applicability

Applicability refers to the degree to which the findings can be applied to different contexts and groups.[ 13 ]

Data analysis

This section deals with the reduction and reconstruction of data and its analysis including sample size calculation. The researcher is expected to explain the steps adopted for coding and sorting the data obtained. Various tests to be used to analyse the data for its robustness, significance should be clearly stated. Author should also mention the names of statistician and suitable software which will be used in due course of data analysis and their contribution to data analysis and sample calculation.[ 9 ]

Ethical considerations

Medical research introduces special moral and ethical problems that are not usually encountered by other researchers during data collection, and hence, the researcher should take special care in ensuring that ethical standards are met. Ethical considerations refer to the protection of the participants' rights (right to self-determination, right to privacy, right to autonomy and confidentiality, right to fair treatment and right to protection from discomfort and harm), obtaining informed consent and the institutional review process (ethical approval). The researcher needs to provide adequate information on each of these aspects.

Informed consent needs to be obtained from the participants (details discussed in further chapters), as well as the research site and the relevant authorities.

When the researcher prepares a research budget, he/she should predict and cost all aspects of the research and then add an additional allowance for unpredictable disasters, delays and rising costs. All items in the budget should be justified.

Appendices are documents that support the proposal and application. The appendices will be specific for each proposal but documents that are usually required include informed consent form, supporting documents, questionnaires, measurement tools and patient information of the study in layman's language.

As with any scholarly research paper, you must cite the sources you used in composing your proposal. Although the words ‘references and bibliography’ are different, they are used interchangeably. It refers to all references cited in the research proposal.

Successful, qualitative research proposals should communicate the researcher's knowledge of the field and method and convey the emergent nature of the qualitative design. The proposal should follow a discernible logic from the introduction to presentation of the appendices.

Financial support and sponsorship

Conflicts of interest.

There are no conflicts of interest.

- Academic Writing

How to Write a Research Proposal | A Guide for Students

What is a research proposal.

A research proposal is a short piece of academic writing that outlines the research a graduate student intends to carry out. It starts by explaining why the research will be helpful or necessary, then describes the steps of the potential research and how the research project would add further knowledge to the field of study. A student submits this as part of the application process for a graduate degree program.

If you’re thinking of pursuing a master’s or doctorate degree, you may need to learn more about how to write a research proposal that will get you into your desired program.

QuillBot is here to help—first, let’s look at why you might write a research proposal. Then we’ll cover the parts it should include, how long it should be, and the tools that can help you write a great one.

What is the purpose of a research proposal?

A student writes a research proposal to describe a research area where a question needs to be answered and to show that they can answer that question by adding new information to the field.

A research committee will read the proposals and decide whether each student will qualify for admittance to the graduate degree program.

To ensure that your proposal fulfils its purpose, take care to include all of the key parts.

What are the parts of a research proposal?

Every research proposal contains a few standard sections, and some include extra sections specific to the program. Below we list the components of most research proposals.

Many schools, like the University of Houston, provide a research proposal example for students . Check with your university to see if they can offer you a similar resource. It can help you understand which parts you’re required to have while writing about your proposed research.

Of course, you’ll need to come up with an effective title. Though a title is less substantial than a section, it makes the first impression on the research committee. It’s also the most concise representation of what you hope to accomplish with your research paper .

A good title conveys your research goal in enough detail to show uniqueness. However, it’s not so detailed that reading and understanding it is tedious. Aim for 10 to 12 words and avoid using abbreviations, such as the ampersand (&).

Introduction

The introduction is your chance to get the research committee enthused about your proposed research. You’re excited about the topic; explain why they should be excited too.

The introduction of a research proposal usually includes a few essential components that are minor in length but major in importance:

- Statement of the problem: a clear description of the gap in existing research that you want to address

- Research questions: the questions you hope to answer by carrying out your study

- Aims and objectives: goals for the research. Aims are big-picture goals: what are you trying to do? Objectives point to smaller goals within the larger ones: what steps will you take to accomplish your aims?

- Rationale: why the research needs to be done

- Significance: how the research will contribute to the field

While it’s common to include these in the introduction, some proposals devote a separate section to them. As you compose these small parts, word them concisely but thoroughly. They must be clear and cover all the most vital aspects of your proposed research.

By the time the research committee has finished reading your introduction, they should have a foundational grasp of why you need to conduct this proposed research, how you plan to do so, and what new ideas it will add to the field. But remember, give only a summary of your methods and new ideas—save the finer points for later sections.

Many writers struggle to write concisely, but it’s an indispensable skill when you’re working on an introduction. QuillBot’s Summarizer can help you condense your thoughts to the perfect length for the introduction.

Background or literature review

Now that you’ve finished the introductory parts of your research proposal, you can begin to go into more detail on your research design. The literature review is likely to be the largest portion of your paper.

The purpose of the background or literature review section is to show that you’re familiar with the existing body of knowledge on your topic. By describing the most pertinent studies related to your research questions, you show that there is truly a knowledge gap in the field and that your proposed research will help close it.

As you write the literature review, you’ll need to draw on other researchers' work. It's crucial that you cite all of your sources properly, or you'll be committing plagiarism .

Method and design

In the next section, you have the chance to show the research committee that you have thought deeply about how to answer your proposed research questions.

Remember to draw on the studies you mentioned in your literature review, which often provide good models. How can you build on them? What theoretical framework(s) have they contributed that you can use to approach your problem effectively?

Based on what you’ve found in the existing literature, describe how you plan to conduct the research. Include the specific research methods you plan to use and how you will analyze any data you collect. Explain why and how these methods will help you achieve your aim and objectives, while other methods won’t.

Your research design should also define the scope of your study, which must fit the time frame of the degree program. A scope that’s too wide may make the research committee think you won’t go deep enough into your topic. Conversely, a scope that’s too narrow could leave you with too few resources to draw from. If the work you plan to do is not enough to fill the time, you could appear lazy or unmotivated, so consider the best way to cover your topic carefully.

After you’ve finished the main sections of your paper, you’ll need to be sure you’ve cited every source correctly. Create a reference list that includes all the sources you mentioned in your literature review and elsewhere.

It's helpful to keep a list and add to it as you're doing your research. That way you'll be sure not to miss a citation.

Other parts of a research proposal

Besides the standard sections above, some proposals also include the following parts:

- An abstract to briefly summarize the proposal

- A research budget section to break down what funding might be needed and where it might come from