Introduction to Logic and Critical Thinking

(10 reviews)

Matthew Van Cleave, Lansing Community College

Copyright Year: 2016

Publisher: Matthew J. Van Cleave

Language: English

Formats Available

Conditions of use.

Learn more about reviews.

Reviewed by "yusef" Alexander Hayes, Professor, North Shore Community College on 6/9/21

Formal and informal reasoning, argument structure, and fallacies are covered comprehensively, meeting the author's goal of both depth and succinctness. read more

Comprehensiveness rating: 5 see less

Formal and informal reasoning, argument structure, and fallacies are covered comprehensively, meeting the author's goal of both depth and succinctness.

Content Accuracy rating: 5

The book is accurate.

Relevance/Longevity rating: 5

While many modern examples are used, and they are helpful, they are not necessarily needed. The usefulness of logical principles and skills have proved themselves, and this text presents them clearly with many examples.

Clarity rating: 5

It is obvious that the author cares about their subject, audience, and students. The text is comprehensible and interesting.

Consistency rating: 5

The format is easy to understand and is consistent in framing.

Modularity rating: 5

This text would be easy to adapt.

Organization/Structure/Flow rating: 5

The organization is excellent, my one suggestion would be a concluding chapter.

Interface rating: 5

I accessed the PDF version and it would be easy to work with.

Grammatical Errors rating: 5

The writing is excellent.

Cultural Relevance rating: 5

This is not an offensive text.

Reviewed by Susan Rottmann, Part-time Lecturer, University of Southern Maine on 3/2/21

I reviewed this book for a course titled "Creative and Critical Inquiry into Modern Life." It won't meet all my needs for that course, but I haven't yet found a book that would. I wanted to review this one because it states in the preface that it... read more

Comprehensiveness rating: 4 see less

I reviewed this book for a course titled "Creative and Critical Inquiry into Modern Life." It won't meet all my needs for that course, but I haven't yet found a book that would. I wanted to review this one because it states in the preface that it fits better for a general critical thinking course than for a true logic course. I'm not sure that I'd agree. I have been using Browne and Keeley's "Asking the Right Questions: A Guide to Critical Thinking," and I think that book is a better introduction to critical thinking for non-philosophy majors. However, the latter is not open source so I will figure out how to get by without it in the future. Overall, the book seems comprehensive if the subject is logic. The index is on the short-side, but fine. However, one issue for me is that there are no page numbers on the table of contents, which is pretty annoying if you want to locate particular sections.

Content Accuracy rating: 4

I didn't find any errors. In general the book uses great examples. However, they are very much based in the American context, not for an international student audience. Some effort to broaden the chosen examples would make the book more widely applicable.

Relevance/Longevity rating: 4

I think the book will remain relevant because of the nature of the material that it addresses, however there will be a need to modify the examples in future editions and as the social and political context changes.

Clarity rating: 3

The text is lucid, but I think it would be difficult for introductory-level students who are not philosophy majors. For example, in Browne and Keeley's "Asking the Right Questions: A Guide to Critical Thinking," the sub-headings are very accessible, such as "Experts cannot rescue us, despite what they say" or "wishful thinking: perhaps the biggest single speed bump on the road to critical thinking." By contrast, Van Cleave's "Introduction to Logic and Critical Thinking" has more subheadings like this: "Using your own paraphrases of premises and conclusions to reconstruct arguments in standard form" or "Propositional logic and the four basic truth functional connectives." If students are prepared very well for the subject, it would work fine, but for students who are newly being introduced to critical thinking, it is rather technical.

It seems to be very consistent in terms of its terminology and framework.

Modularity rating: 4

The book is divided into 4 chapters, each having many sub-chapters. In that sense, it is readily divisible and modular. However, as noted above, there are no page numbers on the table of contents, which would make assigning certain parts rather frustrating. Also, I'm not sure why the book is only four chapter and has so many subheadings (for instance 17 in Chapter 2) and a length of 242 pages. Wouldn't it make more sense to break up the book into shorter chapters? I think this would make it easier to read and to assign in specific blocks to students.

Organization/Structure/Flow rating: 4

The organization of the book is fine overall, although I think adding page numbers to the table of contents and breaking it up into more separate chapters would help it to be more easily navigable.

Interface rating: 4

The book is very simply presented. In my opinion it is actually too simple. There are few boxes or diagrams that highlight and explain important points.

The text seems fine grammatically. I didn't notice any errors.

The book is written with an American audience in mind, but I did not notice culturally insensitive or offensive parts.

Overall, this book is not for my course, but I think it could work well in a philosophy course.

Reviewed by Daniel Lee, Assistant Professor of Economics and Leadership, Sweet Briar College on 11/11/19

This textbook is not particularly comprehensive (4 chapters long), but I view that as a benefit. In fact, I recommend it for use outside of traditional logic classes, but rather interdisciplinary classes that evaluate argument read more

Comprehensiveness rating: 3 see less

This textbook is not particularly comprehensive (4 chapters long), but I view that as a benefit. In fact, I recommend it for use outside of traditional logic classes, but rather interdisciplinary classes that evaluate argument

To the best of my ability, I regard this content as accurate, error-free, and unbiased

The book is broadly relevant and up-to-date, with a few stray temporal references (sydney olympics, particular presidencies). I don't view these time-dated examples as problematic as the logical underpinnings are still there and easily assessed

Clarity rating: 4

My only pushback on clarity is I didn't find the distinction between argument and explanation particularly helpful/useful/easy to follow. However, this experience may have been unique to my class.

To the best of my ability, I regard this content as internally consistent

I found this text quite modular, and was easily able to integrate other texts into my lessons and disregard certain chapters or sub-sections

The book had a logical and consistent structure, but to the extent that there are only 4 chapters, there isn't much scope for alternative approaches here

No problems with the book's interface

The text is grammatically sound

Cultural Relevance rating: 4

Perhaps the text could have been more universal in its approach. While I didn't find the book insensitive per-se, logic can be tricky here because the point is to evaluate meaningful (non-trivial) arguments, but any argument with that sense of gravity can also be traumatic to students (abortion, death penalty, etc)

No additional comments

Reviewed by Lisa N. Thomas-Smith, Graduate Part-time Instructor, CU Boulder on 7/1/19

The text covers all the relevant technical aspects of introductory logic and critical thinking, and covers them well. A separate glossary would be quite helpful to students. However, the terms are clearly and thoroughly explained within the text,... read more

The text covers all the relevant technical aspects of introductory logic and critical thinking, and covers them well. A separate glossary would be quite helpful to students. However, the terms are clearly and thoroughly explained within the text, and the index is very thorough.

The content is excellent. The text is thorough and accurate with no errors that I could discern. The terminology and exercises cover the material nicely and without bias.

The text should easily stand the test of time. The exercises are excellent and would be very helpful for students to internalize correct critical thinking practices. Because of the logical arrangement of the text and the many sub-sections, additional material should be very easy to add.

The text is extremely clearly and simply written. I anticipate that a diligent student could learn all of the material in the text with little additional instruction. The examples are relevant and easy to follow.

The text did not confuse terms or use inconsistent terminology, which is very important in a logic text. The discipline often uses multiple terms for the same concept, but this text avoids that trap nicely.

The text is fairly easily divisible. Since there are only four chapters, those chapters include large blocks of information. However, the chapters themselves are very well delineated and could be easily broken up so that parts could be left out or covered in a different order from the text.

The flow of the text is excellent. All of the information is handled solidly in an order that allows the student to build on the information previously covered.

The PDF Table of Contents does not include links or page numbers which would be very helpful for navigation. Other than that, the text was very easy to navigate. All the images, charts, and graphs were very clear

I found no grammatical errors in the text.

Cultural Relevance rating: 3

The text including examples and exercises did not seem to be offensive or insensitive in any specific way. However, the examples included references to black and white people, but few others. Also, the text is very American specific with many examples from and for an American audience. More diversity, especially in the examples, would be appropriate and appreciated.

Reviewed by Leslie Aarons, Associate Professor of Philosophy, CUNY LaGuardia Community College on 5/16/19

This is an excellent introductory (first-year) Logic and Critical Thinking textbook. The book covers the important elementary information, clearly discussing such things as the purpose and basic structure of an argument; the difference between an... read more

This is an excellent introductory (first-year) Logic and Critical Thinking textbook. The book covers the important elementary information, clearly discussing such things as the purpose and basic structure of an argument; the difference between an argument and an explanation; validity; soundness; and the distinctions between an inductive and a deductive argument in accessible terms in the first chapter. It also does a good job introducing and discussing informal fallacies (Chapter 4). The incorporation of opportunities to evaluate real-world arguments is also very effective. Chapter 2 also covers a number of formal methods of evaluating arguments, such as Venn Diagrams and Propositional logic and the four basic truth functional connectives, but to my mind, it is much more thorough in its treatment of Informal Logic and Critical Thinking skills, than it is of formal logic. I also appreciated that Van Cleave’s book includes exercises with answers and an index, but there is no glossary; which I personally do not find detracts from the book's comprehensiveness.

Overall, Van Cleave's book is error-free and unbiased. The language used is accessible and engaging. There were no glaring inaccuracies that I was able to detect.

Van Cleave's Textbook uses relevant, contemporary content that will stand the test of time, at least for the next few years. Although some examples use certain subjects like former President Obama, it does so in a useful manner that inspires the use of critical thinking skills. There are an abundance of examples that inspire students to look at issues from many different political viewpoints, challenging students to practice evaluating arguments, and identifying fallacies. Many of these exercises encourage students to critique issues, and recognize their own inherent reader-biases and challenge their own beliefs--hallmarks of critical thinking.

As mentioned previously, the author has an accessible style that makes the content relatively easy to read and engaging. He also does a suitable job explaining jargon/technical language that is introduced in the textbook.

Van Cleave uses terminology consistently and the chapters flow well. The textbook orients the reader by offering effective introductions to new material, step-by-step explanations of the material, as well as offering clear summaries of each lesson.

This textbook's modularity is really quite good. Its language and structure are not overly convoluted or too-lengthy, making it convenient for individual instructors to adapt the materials to suit their methodological preferences.

The topics in the textbook are presented in a logical and clear fashion. The structure of the chapters are such that it is not necessary to have to follow the chapters in their sequential order, and coverage of material can be adapted to individual instructor's preferences.

The textbook is free of any problematic interface issues. Topics, sections and specific content are accessible and easy to navigate. Overall it is user-friendly.

I did not find any significant grammatical issues with the textbook.

The textbook is not culturally insensitive, making use of a diversity of inclusive examples. Materials are especially effective for first-year critical thinking/logic students.

I intend to adopt Van Cleave's textbook for a Critical Thinking class I am teaching at the Community College level. I believe that it will help me facilitate student-learning, and will be a good resource to build additional classroom activities from the materials it provides.

Reviewed by Jennie Harrop, Chair, Department of Professional Studies, George Fox University on 3/27/18

While the book is admirably comprehensive, its extensive details within a few short chapters may feel overwhelming to students. The author tackles an impressive breadth of concepts in Chapter 1, 2, 3, and 4, which leads to 50-plus-page chapters... read more

While the book is admirably comprehensive, its extensive details within a few short chapters may feel overwhelming to students. The author tackles an impressive breadth of concepts in Chapter 1, 2, 3, and 4, which leads to 50-plus-page chapters that are dense with statistical analyses and critical vocabulary. These topics are likely better broached in manageable snippets rather than hefty single chapters.

The ideas addressed in Introduction to Logic and Critical Thinking are accurate but at times notably political. While politics are effectively used to exemplify key concepts, some students may be distracted by distinct political leanings.

The terms and definitions included are relevant, but the examples are specific to the current political, cultural, and social climates, which could make the materials seem dated in a few years without intentional and consistent updates.

While the reasoning is accurate, the author tends to complicate rather than simplify -- perhaps in an effort to cover a spectrum of related concepts. Beginning readers are likely to be overwhelmed and under-encouraged by his approach.

Consistency rating: 3

The four chapters are somewhat consistent in their play of definition, explanation, and example, but the structure of each chapter varies according to the concepts covered. In the third chapter, for example, key ideas are divided into sub-topics numbering from 3.1 to 3.10. In the fourth chapter, the sub-divisions are further divided into sub-sections numbered 4.1.1-4.1.5, 4.2.1-4.2.2, and 4.3.1 to 4.3.6. Readers who are working quickly to master new concepts may find themselves mired in similarly numbered subheadings, longing for a grounded concepts on which to hinge other key principles.

Modularity rating: 3

The book's four chapters make it mostly self-referential. The author would do well to beak this text down into additional subsections, easing readers' accessibility.

The content of the book flows logically and well, but the information needs to be better sub-divided within each larger chapter, easing the student experience.

The book's interface is effective, allowing readers to move from one section to the next with a single click. Additional sub-sections would ease this interplay even further.

Grammatical Errors rating: 4

Some minor errors throughout.

For the most part, the book is culturally neutral, avoiding direct cultural references in an effort to remain relevant.

Reviewed by Yoichi Ishida, Assistant Professor of Philosophy, Ohio University on 2/1/18

This textbook covers enough topics for a first-year course on logic and critical thinking. Chapter 1 covers the basics as in any standard textbook in this area. Chapter 2 covers propositional logic and categorical logic. In propositional logic,... read more

This textbook covers enough topics for a first-year course on logic and critical thinking. Chapter 1 covers the basics as in any standard textbook in this area. Chapter 2 covers propositional logic and categorical logic. In propositional logic, this textbook does not cover suppositional arguments, such as conditional proof and reductio ad absurdum. But other standard argument forms are covered. Chapter 3 covers inductive logic, and here this textbook introduces probability and its relationship with cognitive biases, which are rarely discussed in other textbooks. Chapter 4 introduces common informal fallacies. The answers to all the exercises are given at the end. However, the last set of exercises is in Chapter 3, Section 5. There are no exercises in the rest of the chapter. Chapter 4 has no exercises either. There is index, but no glossary.

The textbook is accurate.

The content of this textbook will not become obsolete soon.

The textbook is written clearly.

The textbook is internally consistent.

The textbook is fairly modular. For example, Chapter 3, together with a few sections from Chapter 1, can be used as a short introduction to inductive logic.

The textbook is well-organized.

There are no interface issues.

I did not find any grammatical errors.

This textbook is relevant to a first semester logic or critical thinking course.

Reviewed by Payal Doctor, Associate Professro, LaGuardia Community College on 2/1/18

This text is a beginner textbook for arguments and propositional logic. It covers the basics of identifying arguments, building arguments, and using basic logic to construct propositions and arguments. It is quite comprehensive for a beginner... read more

This text is a beginner textbook for arguments and propositional logic. It covers the basics of identifying arguments, building arguments, and using basic logic to construct propositions and arguments. It is quite comprehensive for a beginner book, but seems to be a good text for a course that needs a foundation for arguments. There are exercises on creating truth tables and proofs, so it could work as a logic primer in short sessions or with the addition of other course content.

The books is accurate in the information it presents. It does not contain errors and is unbiased. It covers the essential vocabulary clearly and givens ample examples and exercises to ensure the student understands the concepts

The content of the book is up to date and can be easily updated. Some examples are very current for analyzing the argument structure in a speech, but for this sort of text understandable examples are important and the author uses good examples.

The book is clear and easy to read. In particular, this is a good text for community college students who often have difficulty with reading comprehension. The language is straightforward and concepts are well explained.

The book is consistent in terminology, formatting, and examples. It flows well from one topic to the next, but it is also possible to jump around the text without loosing the voice of the text.

The books is broken down into sub units that make it easy to assign short blocks of content at a time. Later in the text, it does refer to a few concepts that appear early in that text, but these are all basic concepts that must be used to create a clear and understandable text. No sections are too long and each section stays on topic and relates the topic to those that have come before when necessary.

The flow of the text is logical and clear. It begins with the basic building blocks of arguments, and practice identifying more and more complex arguments is offered. Each chapter builds up from the previous chapter in introducing propositional logic, truth tables, and logical arguments. A select number of fallacies are presented at the end of the text, but these are related to topics that were presented before, so it makes sense to have these last.

The text is free if interface issues. I used the PDF and it worked fine on various devices without loosing formatting.

1. The book contains no grammatical errors.

The text is culturally sensitive, but examples used are a bit odd and may be objectionable to some students. For instance, President Obama's speech on Syria is used to evaluate an extended argument. This is an excellent example and it is explained well, but some who disagree with Obama's policies may have trouble moving beyond their own politics. However, other examples look at issues from all political viewpoints and ask students to evaluate the argument, fallacy, etc. and work towards looking past their own beliefs. Overall this book does use a variety of examples that most students can understand and evaluate.

My favorite part of this book is that it seems to be written for community college students. My students have trouble understanding readings in the New York Times, so it is nice to see a logic and critical thinking text use real language that students can understand and follow without the constant need of a dictionary.

Reviewed by Rebecca Owen, Adjunct Professor, Writing, Chemeketa Community College on 6/20/17

This textbook is quite thorough--there are conversational explanations of argument structure and logic. I think students will be happy with the conversational style this author employs. Also, there are many examples and exercises using current... read more

This textbook is quite thorough--there are conversational explanations of argument structure and logic. I think students will be happy with the conversational style this author employs. Also, there are many examples and exercises using current events, funny scenarios, or other interesting ways to evaluate argument structure and validity. The third section, which deals with logical fallacies, is very clear and comprehensive. My only critique of the material included in the book is that the middle section may be a bit dense and math-oriented for learners who appreciate the more informal, informative style of the first and third section. Also, the book ends rather abruptly--it moves from a description of a logical fallacy to the answers for the exercises earlier in the text.

The content is very reader-friendly, and the author writes with authority and clarity throughout the text. There are a few surface-level typos (Starbuck's instead of Starbucks, etc.). None of these small errors detract from the quality of the content, though.

One thing I really liked about this text was the author's wide variety of examples. To demonstrate different facets of logic, he used examples from current media, movies, literature, and many other concepts that students would recognize from their daily lives. The exercises in this text also included these types of pop-culture references, and I think students will enjoy the familiarity--as well as being able to see the logical structures behind these types of references. I don't think the text will need to be updated to reflect new instances and occurrences; the author did a fine job at picking examples that are relatively timeless. As far as the subject matter itself, I don't think it will become obsolete any time soon.

The author writes in a very conversational, easy-to-read manner. The examples used are quite helpful. The third section on logical fallacies is quite easy to read, follow, and understand. A student in an argument writing class could benefit from this section of the book. The middle section is less clear, though. A student learning about the basics of logic might have a hard time digesting all of the information contained in chapter two. This material might be better in two separate chapters. I think the author loses the balance of a conversational, helpful tone and focuses too heavily on equations.

Consistency rating: 4

Terminology in this book is quite consistent--the key words are highlighted in bold. Chapters 1 and 3 follow a similar organizational pattern, but chapter 2 is where the material becomes more dense and equation-heavy. I also would have liked a closing passage--something to indicate to the reader that we've reached the end of the chapter as well as the book.

I liked the overall structure of this book. If I'm teaching an argumentative writing class, I could easily point the students to the chapters where they can identify and practice identifying fallacies, for instance. The opening chapter is clear in defining the necessary terms, and it gives the students an understanding of the toolbox available to them in assessing and evaluating arguments. Even though I found the middle section to be dense, smaller portions could be assigned.

The author does a fine job connecting each defined term to the next. He provides examples of how each defined term works in a sentence or in an argument, and then he provides practice activities for students to try. The answers for each question are listed in the final pages of the book. The middle section feels like the heaviest part of the whole book--it would take the longest time for a student to digest if assigned the whole chapter. Even though this middle section is a bit heavy, it does fit the overall structure and flow of the book. New material builds on previous chapters and sub-chapters. It ends abruptly--I didn't realize that it had ended, and all of a sudden I found myself in the answer section for those earlier exercises.

The simple layout is quite helpful! There is nothing distracting, image-wise, in this text. The table of contents is clearly arranged, and each topic is easy to find.

Tiny edits could be made (Starbuck's/Starbucks, for one). Otherwise, it is free of distracting grammatical errors.

This text is quite culturally relevant. For instance, there is one example that mentions the rumors of Barack Obama's birthplace as somewhere other than the United States. This example is used to explain how to analyze an argument for validity. The more "sensational" examples (like the Obama one above) are helpful in showing argument structure, and they can also help students see how rumors like this might gain traction--as well as help to show students how to debunk them with their newfound understanding of argument and logic.

The writing style is excellent for the subject matter, especially in the third section explaining logical fallacies. Thank you for the opportunity to read and review this text!

Reviewed by Laurel Panser, Instructor, Riverland Community College on 6/20/17

This is a review of Introduction to Logic and Critical Thinking, an open source book version 1.4 by Matthew Van Cleave. The comparison book used was Patrick J. Hurley’s A Concise Introduction to Logic 12th Edition published by Cengage as well as... read more

This is a review of Introduction to Logic and Critical Thinking, an open source book version 1.4 by Matthew Van Cleave. The comparison book used was Patrick J. Hurley’s A Concise Introduction to Logic 12th Edition published by Cengage as well as the 13th edition with the same title. Lori Watson is the second author on the 13th edition.

Competing with Hurley is difficult with respect to comprehensiveness. For example, Van Cleave’s book is comprehensive to the extent that it probably covers at least two-thirds or more of what is dealt with in most introductory, one-semester logic courses. Van Cleave’s chapter 1 provides an overview of argumentation including discerning non-arguments from arguments, premises versus conclusions, deductive from inductive arguments, validity, soundness and more. Much of Van Cleave’s chapter 1 parallel’s Hurley’s chapter 1. Hurley’s chapter 3 regarding informal fallacies is comprehensive while Van Cleave’s chapter 4 on this topic is less extensive. Categorical propositions are a topic in Van Cleave’s chapter 2; Hurley’s chapters 4 and 5 provide more instruction on this, however. Propositional logic is another topic in Van Cleave’s chapter 2; Hurley’s chapters 6 and 7 provide more information on this, though. Van Cleave did discuss messy issues of language meaning briefly in his chapter 1; that is the topic of Hurley’s chapter 2.

Van Cleave’s book includes exercises with answers and an index. A glossary was not included.

Reviews of open source textbooks typically include criteria besides comprehensiveness. These include comments on accuracy of the information, whether the book will become obsolete soon, jargon-free clarity to the extent that is possible, organization, navigation ease, freedom from grammar errors and cultural relevance; Van Cleave’s book is fine in all of these areas. Further criteria for open source books includes modularity and consistency of terminology. Modularity is defined as including blocks of learning material that are easy to assign to students. Hurley’s book has a greater degree of modularity than Van Cleave’s textbook. The prose Van Cleave used is consistent.

Van Cleave’s book will not become obsolete soon.

Van Cleave’s book has accessible prose.

Van Cleave used terminology consistently.

Van Cleave’s book has a reasonable degree of modularity.

Van Cleave’s book is organized. The structure and flow of his book is fine.

Problems with navigation are not present.

Grammar problems were not present.

Van Cleave’s book is culturally relevant.

Van Cleave’s book is appropriate for some first semester logic courses.

Table of Contents

Chapter 1: Reconstructing and analyzing arguments

- 1.1 What is an argument?

- 1.2 Identifying arguments

- 1.3 Arguments vs. explanations

- 1.4 More complex argument structures

- 1.5 Using your own paraphrases of premises and conclusions to reconstruct arguments in standard form

- 1.6 Validity

- 1.7 Soundness

- 1.8 Deductive vs. inductive arguments

- 1.9 Arguments with missing premises

- 1.10 Assuring, guarding, and discounting

- 1.11 Evaluative language

- 1.12 Evaluating a real-life argument

Chapter 2: Formal methods of evaluating arguments

- 2.1 What is a formal method of evaluation and why do we need them?

- 2.2 Propositional logic and the four basic truth functional connectives

- 2.3 Negation and disjunction

- 2.4 Using parentheses to translate complex sentences

- 2.5 “Not both” and “neither nor”

- 2.6 The truth table test of validity

- 2.7 Conditionals

- 2.8 “Unless”

- 2.9 Material equivalence

- 2.10 Tautologies, contradictions, and contingent statements

- 2.11 Proofs and the 8 valid forms of inference

- 2.12 How to construct proofs

- 2.13 Short review of propositional logic

- 2.14 Categorical logic

- 2.15 The Venn test of validity for immediate categorical inferences

- 2.16 Universal statements and existential commitment

- 2.17 Venn validity for categorical syllogisms

Chapter 3: Evaluating inductive arguments and probabilistic and statistical fallacies

- 3.1 Inductive arguments and statistical generalizations

- 3.2 Inference to the best explanation and the seven explanatory virtues

- 3.3 Analogical arguments

- 3.4 Causal arguments

- 3.5 Probability

- 3.6 The conjunction fallacy

- 3.7 The base rate fallacy

- 3.8 The small numbers fallacy

- 3.9 Regression to the mean fallacy

- 3.10 Gambler's fallacy

Chapter 4: Informal fallacies

- 4.1 Formal vs. informal fallacies

- 4.1.1 Composition fallacy

- 4.1.2 Division fallacy

- 4.1.3 Begging the question fallacy

- 4.1.4 False dichotomy

- 4.1.5 Equivocation

- 4.2 Slippery slope fallacies

- 4.2.1 Conceptual slippery slope

- 4.2.2 Causal slippery slope

- 4.3 Fallacies of relevance

- 4.3.1 Ad hominem

- 4.3.2 Straw man

- 4.3.3 Tu quoque

- 4.3.4 Genetic

- 4.3.5 Appeal to consequences

- 4.3.6 Appeal to authority

Answers to exercises Glossary/Index

Ancillary Material

About the book.

This is an introductory textbook in logic and critical thinking. The goal of the textbook is to provide the reader with a set of tools and skills that will enable them to identify and evaluate arguments. The book is intended for an introductory course that covers both formal and informal logic. As such, it is not a formal logic textbook, but is closer to what one would find marketed as a “critical thinking textbook.”

About the Contributors

Matthew Van Cleave , PhD, Philosophy, University of Cincinnati, 2007. VAP at Concordia College (Moorhead), 2008-2012. Assistant Professor at Lansing Community College, 2012-2016. Professor at Lansing Community College, 2016-

Contribute to this Page

PHIL102: Introduction to Critical Thinking and Logic

Course introduction.

- Time: 40 hours

- College Credit Recommended ($25 Proctor Fee) -->

- Free Certificate

The course touches upon a wide range of reasoning skills, from verbal argument analysis to formal logic, visual and statistical reasoning, scientific methodology, and creative thinking. Mastering these skills will help you become a more perceptive reader and listener, a more persuasive writer and presenter, and a more effective researcher and scientist.

The first unit introduces the terrain of critical thinking and covers the basics of meaning analysis, while the second unit provides a primer for analyzing arguments. All of the material in these first units will be built upon in subsequent units, which cover informal and formal logic, Venn diagrams, scientific reasoning, and strategic and creative thinking.

Course Syllabus

First, read the course syllabus. Then, enroll in the course by clicking "Enroll me". Click Unit 1 to read its introduction and learning outcomes. You will then see the learning materials and instructions on how to use them.

Unit 1: Introduction and Meaning Analysis

Critical thinking is a broad classification for a diverse array of reasoning techniques. In general, critical thinking works by breaking arguments and claims down to their basic underlying structure so we can see them clearly and determine whether they are rational. The idea is to help us do a better job of understanding and evaluating what we read, what we hear, and what we write and say.

In this unit, we will define the broad contours of critical thinking and learn why it is a valuable and useful object of study. We will also introduce the fundamentals of meaning analysis: the difference between literal meaning and implication, the principles of definition, how to identify when a disagreement is merely verbal, the distinction between necessary and sufficient conditions, and problems with the imprecision of ordinary language.

Completing this unit should take you approximately 5 hours.

Unit 2: Argument Analysis

Arguments are the fundamental components of all rational discourse: nearly everything we read and write, like scientific reports, newspaper columns, and personal letters, as well as most of our verbal conversations, contain arguments. Picking the arguments out from the rest of our often convoluted discourse can be difficult. Once we have identified an argument, we still need to determine whether or not it is sound. Luckily, arguments obey a set of formal rules that we can use to determine whether they are good or bad.

In this unit, you will learn how to identify arguments, what makes an argument sound as opposed to unsound or merely valid, the difference between deductive and inductive reasoning, and how to map arguments to reveal their structure.

Completing this unit should take you approximately 7 hours.

Unit 3: Basic Sentential Logic

This unit introduces a topic that many students find intimidating: formal logic. Although it sounds difficult and complicated, formal (or symbolic) logic is actually a fairly straightforward way of revealing the structure of reasoning. By translating arguments into symbols, you can more readily see what is right and wrong with them and learn how to formulate better arguments. Advanced courses in formal logic focus on using rules of inference to construct elaborate proofs. Using these techniques, you can solve many complicated problems simply by manipulating symbols on the page. In this course, however, you will only be looking at the most basic properties of a system of logic. In this unit, you will learn how to turn phrases in ordinary language into well-formed formulas, draw truth tables for formulas, and evaluate arguments using those truth tables.

Completing this unit should take you approximately 13 hours.

Unit 4: Venn Diagrams

In addition to using predicate logic, the limitations of sentential logic can also be overcome by using Venn diagrams to illustrate statements and arguments. Statements that include general words like "some" or "few" as well as absolute words like "every" and "all" – so-called categorical statements – lend themselves to being represented on paper as circles that may or may not overlap.

Venn diagrams are especially helpful when dealing with logical arguments called syllogisms. Syllogisms are a special type of three-step argument with two premises and a conclusion, which involve quantifying terms. In this unit, you will learn the basic principles of Venn diagrams, how to use them to represent statements, and how to use them to evaluate arguments.

Completing this unit should take you approximately 6 hours.

Unit 5: Fallacies

Now that you have studied the necessary structure of a good argument and can represent its structure visually, you might think it would be simple to pick out bad arguments. However, identifying bad arguments can be very tricky in practice. Very often, what at first appears to be ironclad reasoning turns out to contain one or more subtle errors.

Fortunately, there are many easily identifiable fallacies (mistakes of reasoning) that you can learn to recognize by their structure or content. In this unit, you will learn about the nature of fallacies, look at a couple of different ways of classifying them, and spend some time dealing with the most common fallacies in detail.

Completing this unit should take you approximately 3 hours.

Unit 6: Scientific Reasoning

Unlike the syllogistic arguments you explored in the last unit, which are a form of deductive argument, scientific reasoning is empirical. This means that it depends on observation and evidence, not logical principles. Although some principles of deductive reasoning do apply in science, such as the principle of contradiction, scientific arguments are often inductive. For this reason, science often deals with confirmation and disconfirmation.

Nonetheless, there are general guidelines about what constitutes good scientific reasoning, and scientists are trained to be critical of their inferences and those of others in the scientific community. In this unit, you will investigate some standard methods of scientific reasoning, some principles of confirmation and disconfirmation, and some techniques for identifying and reasoning about causation.

Completing this unit should take you approximately 4 hours.

Unit 7: Strategic Reasoning and Creativity

While most of this course has focused on the types of reasoning necessary to critique and evaluate existing knowledge or to extend our knowledge following correct procedures and rules, an enormous branch of our reasoning practice runs in the opposite direction. Strategic reasoning, problem-solving, and creative thinking all rely on an ineffable component of novelty supplied by the thinker.

Despite their seemingly mystical nature, problem-solving and creative thinking are best approached by following tried and tested procedures that prompt our cognitive faculties to produce new ideas and solutions by extending our existing knowledge. In this unit, you will investigate problem-solving techniques, representing complex problems visually, making decisions in risky and uncertain scenarios, and creative thinking in general.

Completing this unit should take you approximately 2 hours.

Study Guide

This study guide will help you get ready for the final exam. It discusses the key topics in each unit, walks through the learning outcomes, and lists important vocabulary terms. It is not meant to replace the course materials!

Course Feedback Survey

Please take a few minutes to give us feedback about this course. We appreciate your feedback, whether you completed the whole course or even just a few resources. Your feedback will help us make our courses better, and we use your feedback each time we make updates to our courses.

If you come across any urgent problems, email [email protected].

Certificate Final Exam

Take this exam if you want to earn a free Course Completion Certificate.

To receive a free Course Completion Certificate, you will need to earn a grade of 70% or higher on this final exam. Your grade for the exam will be calculated as soon as you complete it. If you do not pass the exam on your first try, you can take it again as many times as you want, with a 7-day waiting period between each attempt.

Once you pass this final exam, you will be awarded a free Course Completion Certificate .

Saylor Direct Credit

Take this exam if you want to earn college credit for this course . This course is eligible for college credit through Saylor Academy's Saylor Direct Credit Program .

The Saylor Direct Credit Final Exam requires a proctoring fee of $5 . To pass this course and earn a Credly Badge and official transcript , you will need to earn a grade of 70% or higher on the Saylor Direct Credit Final Exam. Your grade for this exam will be calculated as soon as you complete it. If you do not pass the exam on your first try, you can take it again a maximum of 3 times , with a 14-day waiting period between each attempt.

We are partnering with SmarterProctoring to help make the proctoring fee more affordable. We will be recording you, your screen, and the audio in your room during the exam. This is an automated proctoring service, but no decisions are automated; recordings are only viewed by our staff with the purpose of making sure it is you taking the exam and verifying any questions about exam integrity. We understand that there are challenges with learning at home - we won't invalidate your exam just because your child ran into the room!

Requirements:

- Desktop Computer

- Chrome (v74+)

- Webcam + Microphone

- 1mbps+ Internet Connection

Once you pass this final exam, you will be awarded a Credly Badge and can request an official transcript .

Saylor Direct Credit Exam

This exam is part of the Saylor Direct College Credit program. Before attempting this exam, review the Saylor Direct Credit page for complete requirements.

Essential exam information:

- You must take this exam with our automated proctor. If you cannot, please contact us to request an override.

- The automated proctoring session will cost $5 .

- This is a closed-book, closed-notes exam (see allowed resources below).

- You will have two (2) hours to complete this exam.

- You have up to 3 attempts, but you must wait 14 days between consecutive attempts of this exam.

- The passing grade is 70% or higher.

- This exam consists of 50 multiple-choice questions.

Some details about taking your exam:

- Exam questions are distributed across multiple pages.

- Exam questions will have several plausible options; be sure to pick the answer that best satisfies each part of the question.

- Your answers are saved each time you move to another page within the exam.

- You can answer the questions in any order.

- You can go directly to any question by clicking its number in the navigation panel.

- You can flag a question to remind yourself to return to it later.

- You will receive your grade as soon as you submit your answers.

Allowed resources:

Gather these resources before you start your exam.

- Blank paper

What should I do before my exam?

- Gather these before you start your exam:

- A photo I.D. to show before your exam.

- A credit card to pay the automated proctoring fee.

- (optional) Blank paper and pencil.

- (optional) A glass of water.

- Make sure your work area is well-lit and your face is visible.

- We will be recording your screen, so close any extra tabs!

- Disconnect any extra monitors attached to your computer.

- You will have up to two (2) hours to complete your exam. Try to make sure you won't be interrupted during that time!

- You will require at least 1mbps of internet bandwidth. Ask others sharing your connection not to stream during your exam.

- Take a deep breath; you got this!

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

Margin Size

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

3.E: Chapter Three (Exercises)

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 223821

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

How can I tell one from the other?

- The objection is that the inference itself is incomplete or weak or invalid or simply doesn’t make any sense.

- An objection to a hidden premise is actually an objection to an inference: you’re claiming that the inference rests on a weak hidden premise and so is an incomplete inference.

- The objection is that some particular claim is false or at least is likely or plausibly false.

Exercise \(\PageIndex{1}\): Conjoint vs Independent Support

For each, determine whether the support offered by the premises is conjoint or independent. Deploy the negative test when you’re unsure.

A. Eating healthy food is important and Figs are super healthy, so we should eat more figs.

B. I have to have a steady income to support my family, I already have a stable job, and grad school would require me to quit my job, so I shouldn’t go to grad school.

C. All of the nurses have gone on the strike, the custodial staff is threatening the same, and the doctors are demanding better legal support. This hospital is in trouble right now.

D. He is ten years younger than you and no one should date anyone ten years younger, so you can’t date him!

E. An ergonomic desk can prevent permanent injury, is more comfortable to use, and is cost-effective, so can I please buy one for my office?

F. A robust economic recovery will require higher taxes on the wealthy, and we need to have a strong recovery to prevent melt downs in the near future, so we must raise taxes on the wealthy.

G. We’ve always been honest with each other and the honest thing to do right now is to tell you that that outfit is terrible, so I need to tell you the truth about that outfit.

Exercise \(\PageIndex{2}\): Terminology

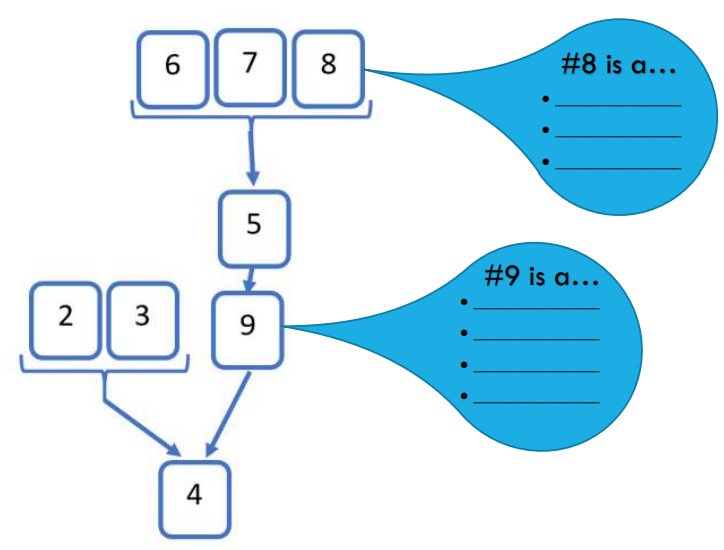

Fill in the blank labels using one of each of the following key terms: (A) Sub-Conclusion, (B) Sub-Premise, (C) Main Premise, (D) A premise on level 4 of the argument map, (E) A premise on level 2 of the argument map, (F) Conjoint Premise, (G) Independent Premise.

Exercise \(\PageIndex{3}\): Simple Argument Maps

For each, create an argument map. Be sure to distinguish between conjoint and independent support.

A. (1) Eating healthy food is the most effective weight-loss strategy, since (2) the amount of calories one takes in while eating even small snacks takes a long time to burn off by exercising, and (3) almost no one can afford to spend hours and hours exercising throughout the day.

B. (1) We’ve been out here in the sun all day, and (2) being in the sun for too long is unhealthy, so (3) let’s go inside.

C. (1) He’s so popular. (2) Everyone wanted to be invited to his birthday party and (3) he had five people invite him to the dance.

D. (1) We should ban all guns. (2) Guns are especially effective killing machines for mass killings. Also, (3) children often have fatal accidents with guns. Furthermore, (4) guns don’t have a non-violent use.

E. (1) Having intercourse before 18 is wrong because, (2) you are not emotionally mature enough to deal with the awkwardness and intimacy of the situation, and (3) you are not mature enough to deal with the potential consequences of the situation (pregnancy or STIs).

F. (1) Treating others with respect is important, so (2) we should all respect each other, and (3) we should try to teach our children to respect others.

G. (1) Oreos aren’t healthy, since (2) Nabisco products generally aren’t healthy. Think about it: (3) Pringles aren’t healthy, (4) Pop Tarts aren’t healthy, and (5) neither are Chips Ahoy.

H. (1) People are starting not to like you. (2) Tina said she wasn’t your friend anymore, (3) Beto said he doesn’t like you, and (4) I certainly don’t want to be around you.

Exercise \(\PageIndex{4}\): More Complex Argument Maps

A. (1) I know that Sally went to the park with Billy because (2) Sally said she’d go with him if he asked, and (3) Billy likes Sally (so he wouldn’t ask her as a prank) and (4) Billy asked Sally to go to the park.

B. (1) Eating any meat is wrong because, (2) most meat is produced in factory farms, (3) animals in factory farms suffer greatly, and (4) even ‘free range’ and ‘organic’ meat causes animal suffering.

C. (1) We already have almost all of the technology needed to clone dinosaurs and (2) human beings tend to do whatever they find they can do. (3) So, killer dinosaurs will roam the Earth one day. And since this is true, we can expect two things: (4) an armed response leading to the loss of innocent life, and (5) movie producers trying to buy the rights to the story.

D. (1) Burning fossil fuels like petrol, coal, and natural gas contributes to global warming. (2) According to experts, the combustion reaction releases free molecules of CO 2 into the atmosphere, and (3) Scientists wouldn’t lie about this. Think about it: (4) there’s no profit incentive for scientists to lie about this, but (5) there is a profit motive for other people to deny that it is true.

E. The Republicans have argued repeatedly that (1) the Affordable Care Act is in a death spiral. Because, they say, (2) premiums are getting higher, and (3) as premiums get higher, the people will stop purchasing policies and (4) if the people stop purchasing policies, then the insurance companies will pull out of the exchanges, and (5) if that happens, then the whole system collapses.

F. (1) We need to protect the environment, since (2) biodiversity is necessary to protect future food sources and (3) biodiversity is sustainable only in a relatively healthy global environment. Furthermore, (4) We take great pleasure in the natural wonders that the Earth has to offer (5) [suppressed premise]

Exercise \(\PageIndex{5}\): Even More Complex Argument Maps

A. (1) We need to buy a new trampoline, since (2) our son almost hurt himself really badly when this one broke last week, and (3) I don’t want to risk it again. (4) Even if you’re able to fix it, there’s no guarantee that it will be as safe as a new one. Think about it: (5) older trampolines like ours don’t have a net around them, and (6) the net makes it less likely that a kid will bounce off onto the ground and hurt themselves. Finally, (7) older trampolines like ours don’t have good spring covers, and (8) without spring covers, the risk of pinching oneself or falling through the springs and breaking a limb are very high.

B. (1) Eating kale is sometimes unsatisfying, but the fact is that (2) Kale has countless health benefits. (3) It is rich in folate and (4) folate helps guard against bad epigenetic changes. (5) It has more minerals and vitamins than most meat sources and (6) vitamins and minerals got from whole food sources are better than those got from multivitamins and other supplements since (7) whole foods contain more bioavailable forms of vitamins and minerals.

C. (1) We’ve already been in Afghanistan for over a decade and (2) no other American war has lasted this long, so (3) Afghanistan is the longest running American war. (4) We’ve shown little sign of progress in the past few years, and (5) we’ve sunk countless dollars into Afghan infrastructure and security projects with little to show for it. Given all of this, (6) we should pull out of Afghanistan and (7) we should divest interest in the Afghan society. (8) Since we’ve already tried so hard to fix it, (9) we should let them try to solve their own problems!

D. (1) Epigenetics is the most important frontier in genetic research. (2) Countless traits and processes depend not on genetic changes, but on epigenetic changes, (3) epigenetic changes are easier to induce through therapies, chemicals, and other interventions in a clinical setting, and (4) we already know the basic rules of genetics, but are far behind in our understanding of epigenetics. Given all that, it follows that (5) we should shift the balance of funding in favor of epigenetic research and (6) we should fund more PhD’s in epigenetics as well.

E. (1) We should put more direct emphasis in school and college on thinking clearly and critically. (2) The most important skill in life is thinking well. I think this because (3) other important skills like decision making and communication rely centrally on thinking well, and (4) a good citizen, employee, and overall person is one who can think clearly and rationally. (5) Citizens must weigh complex values in voting on candidates and referenda, (6) employees must make decisions in the workplace based on complex policies and competing needs, and (7) people in general need to have habits of self-critical and careful thinking in order to live good lives.

Exercise \(\PageIndex{6}\): Hidden Assumptions

For each inference, identify the most direct hidden assumption.

A. Moby Dick is a whale. So Moby Dick is a mammal.

B. Giving students a fail grade will damage their self-confidence. Therefore, we should not fail students.

C. It should not be illegal for adults to smoke pot. After all, it does not harm anyone.

D. There is nothing wrong with texting during lectures. Other students do it all the time.

E. Traces of ammonia have been found in Mars' atmosphere. So there must be life on Mars.

F. I don't like people who spit on the sidewalk, so littering should be illegal.

G. No one even cares what you think, so what you think isn't important.

H. Americans believe in freedom, so any law that restricts our freedom should be abolished.

I. Trees are beautiful, so we should plant more of them.

J. Carbon emissions contribute to global warming, so we should tax them.

Exercise \(\PageIndex{7}\): Mapping Hidden Assumptions

For each inference, identify the hidden assumption and then create a map of the inference including the hidden assumption.

A. The truth is, (1) we can’t vote for the Republican candidate. (2) She doesn’t believe in global warming.

B. (1) Nobody has ever been there and come back, and (2) I have children, so (3) I’m not going.

C. (1) Freedom isn’t free. (2) So, someone has to pay the price for freedom. (3) The way people pay the price of freedom is by serving in the armed forces. (4) So we should institute a draft. [at least two hidden assumptions]

D. (1) Nobody has ever seen a dinosaur, so (3) dinosaurs don’t exist.

E. (1) We should reduce the penalty for drunken driving, as (2) a milder penalty would mean more convictions. (3) The only way to reduce the penalty is to elect more liberal judges and prosecutors, so (4) we should elect liberal judges and prosecutors.

F. (1) Never again should we bow to tyrants, because (2) tyranny has been the mark of rule throughout human history, (3) as has cruelty and abject want. It follows that (4) we must rebel against the Imperial rule of England.

G. (1) Only real marriages should be recognized by the state, so (2) polygamist marriages shouldn't be recognized by the state. (3) Any marriage not recognized by the state should be illegal. So (4) polygamist marriages should be illegal. (5) Another reason they should be illegal is that, polygamist marriages often result in abusive situations. [the hidden assumption is between 1 and 2]

H. (1) No one believes in Odin anymore, so (2) why should anyone believe in God? [this is a rhetorical question, which is a claim that is disguised as a question. The claim appears to be "no one should believe in God”]. (3) If no one should rationally believe in something, then we should actively fight against belief in it. It follows that (4) we should actively fight against belied in the existence of God. (5) A world without believers would be a better world to live in. [the hidden assumption is between 1 and 2]

I. (1) We can't let terrorists live here with us in Pakistan, so (2) we should expel all Christians from our country. (3) Christians also don't contribute to the economy and (4) could potentially be spies for the Americans. [Where's the most blatant hidden assumption? There are more than one, but one in particular is relatively clearly a missing assumption of the argument]

Exercise \(\PageIndex{8}\): Identifying Types of Objections

Identify which type of objection is illustrated: an objection to a premise or an objection to an inference (including pointing out that there’s a hidden premise and/or rejecting a hidden premise)?

A. I agree with your conclusion, but it doesn’t follow from your assumptions.

B. Interesting argument, but what I don’t understand is your claim that every case of tyranny is a case of injustice. That doesn’t seem quite right.

C. You claim that there isn’t a threat to the Amazon. On the contrary, there are countless threats, one of which is people claiming that there isn’t a threat to the Amazon!

D. So if I accept all of your assumptions, it doesn’t seem to me that I must accept your conclusion.

E. If I have it right, it seems to me that your inference rests on a hidden assumption that we ought to do whatever is in our national interest. That’s not clearly true. Think about cases of humanitarian aid that only very indirectly if at all are in our national interest.

F. I think I understand the general thrust of this argument, but one claim makes me uncomfortable. Your inference rests on the claim, as you stated it, that Great Britain is to blame for more historical atrocities than any other European nation. That’s not clearly right.

G. I don’t think this is a good argument. We won’t clearly advance well beyond where we are today in terms of computing power because of the physical limits of the hardware we have available.

Exercise \(\PageIndex{9}\): Mapping Ojections

Identify which kind of objection is illustrated and then map the objection along with the original argument.

A. Person A: (1) Edward Snowden released petabytes of classified data. (2) He should be convicted of treason.

Person B: Wait a minute! (3) We shouldn’t just convict anyone who releases that much data of treason!

Person A: (4) If we don’t, then we’ll be opening the door to more dangerous leaks.

Person B: (5) Actually, come to think of it, I don’t think he did release petabytes. I think it was only Terabytes.

B. The Republicans have argued repeatedly that (1) the Affordable Care Act is in a death spiral. Because, they say, (2) premiums are getting higher, and (3) as premiums get higher, the people will stop purchasing policies and (4) if the people stop purchasing policies, then the insurance companies will pull out of the exchanges, and (5) if that happens, then the whole system collapses. But their conclusion doesn't follow, since (6) people need health insurance and won't stop purchasing it if prices continue to rise incrementally.

C. Person A: (1) College isn't designed around the goal of producing good plumbers and electricians and welders. (2) Furthermore, college is expensive and (3) college is time-consuming. So (4) we shouldn't expect everyone to go to college.

Person B: I understand your inference, but (5) college does make one a better plumber, electrician, and welder because it gives you a host of intellectual resources to bring to bear on solving the many unforeseen problems that arise on jobs like that.

Person C: I actually take issue with the inference here from your first claim to your conclusion, since (6) college isn't about job training, but is instead about creating a well-informed citizenry that can make rational and informed decisions at the voting booth.

D. Obama argued that (1) we should pass the ACA, claiming that (2) there is an epidemic of chronically-ill citizens without health insurance due to their pre-existing conditions and that (3) many citizens simply can’t afford health insurance.

But (4) the ACA won’t provide health insurance to a large group of relatively poor Americans.

E. Her argument was as follows: “(1) No one wants to be put in the position where they are faced with a deadly intruder without the proper means to protect theirself and their family. (2) Gun laws make it probable that someone will end up in that situation. (3) Therefore, we can’t enact gun control legislation.”

But that argument isn’t convincing. (4) Even if we accept the premises, we need not accept the conclusion. After all, there are reasons to pass gun control that must be addressed.

Exercise \(\PageIndex{10}\): Hidden Assumptions and Objections

Identify the hidden assumptions in the first argument and then map both the argument and the objections. Remember that objections to hidden assumptions are objections to inferences and so they should be mapped as such.

A. Frank: (1) We'll never make it to the party on time, so (2) let's just turn around and head home. (3) Samir and Imani live miles away and (4) we can't go very fast in this traffic.

Margaret: That's ridiculous, we'll absolutely make it on time. First, (5) we have 30 minutes to get there and also (6) we could be 15 minutes late and still be "on time" since it's a party.

B. Tamil: (1) We need to protect the environment, since (2) biodiversity is necessary to protect future food sources and (3) biodiversity is sustainable only in a relatively healthy global environment. Furthermore, (4) we take great pleasure in the natural wonders that the Earth has to offer (5) [suppressed premise]

Jamal: (6) I agree with your conclusion, but even if we accept that biodiversity is necessary and that protecting the environment is necessary for protecting biodiversity, we need not accept your conclusion.

C. (1) Counting Crows wrote and performed Mrs. Robinson, so (2) They’re the best band ever.

Ummm... (3) they wrote and performed “Mr. Jones”, not Mrs. Robinson. And either way (4) neither song would make them the best band ever.

D. He said “(1) I need some space, so (2) we need to break up.” But (3) he doesn’t need space. And either way, (4) needing space isn’t a good enough reason to break up with someone.

E. She said “(1) Potato chips are high in saturated fat and salt, and so (2) they should be consumed very sparingly.” But that’s a bad inference since (3) dietary research is overturning the idea that saturated fat is bad for humans and (4) humans need salt to maintain proper blood volume and electrolyte concentrations.

F. Pablo: (1) We shouldn’t eat even fake animal meat since (2) we wouldn’t think it’s okay to eat fake human meat. Afterall, (3) eating fake human meat would be tacitly affirming that cannibalism is morally acceptable. Marisela: I disagree, (4) there’s a faulty hidden premise there: that eating fake animal meat is analogous to eating fake human meat. Furthermore, (5) the other inference for the claim that eating fake human Meat is wrong has a hidden assumption as well and I’m not so sure it’s correct.

Pursuing Truth: A Guide to Critical Thinking

Chapter 2 arguments.

The fundamental tool of the critical thinker is the argument. For a good example of what we are not talking about, consider a bit from a famous sketch by Monty Python’s Flying Circus : 3

2.1 Identifying Arguments

People often use “argument” to refer to a dispute or quarrel between people. In critical thinking, an argument is defined as

A set of statements, one of which is the conclusion and the others are the premises.

There are three important things to remember here:

- Arguments contain statements.

- They have a conclusion.

- They have at least one premise

Arguments contain statements, or declarative sentences. Statements, unlike questions or commands, have a truth value. Statements assert that the world is a particular way; questions do not. For example, if someone asked you what you did after dinner yesterday evening, you wouldn’t accuse them of lying. When the world is the way that the statement says that it is, we say that the statement is true. If the statement is not true, it is false.

One of the statements in the argument is called the conclusion. The conclusion is the statement that is intended to be proved. Consider the following argument:

Calculus II will be no harder than Calculus I. Susan did well in Calculus I. So, Susan should do well in Calculus II.

Here the conclusion is that Susan should do well in Calculus II. The other two sentences are premises. Premises are the reasons offered for believing that the conclusion is true.

2.1.1 Standard Form

Now, to make the argument easier to evaluate, we will put it into what is called “standard form.” To put an argument in standard form, write each premise on a separate, numbered line. Draw a line underneath the last premise, the write the conclusion underneath the line.

- Calculus II will be no harder than Calculus I.

- Susan did well in Calculus I.

- Susan should do well in Calculus II.

Now that we have the argument in standard form, we can talk about premise 1, premise 2, and all clearly be referring to the same thing.

2.1.2 Indicator Words

Unfortunately, when people present arguments, they rarely put them in standard form. So, we have to decide which statement is intended to be the conclusion, and which are the premises. Don’t make the mistake of assuming that the conclusion comes at the end. The conclusion is often at the beginning of the passage, but could even be in the middle. A better way to identify premises and conclusions is to look for indicator words. Indicator words are words that signal that statement following the indicator is a premise or conclusion. The example above used a common indicator word for a conclusion, ‘so.’ The other common conclusion indicator, as you can probably guess, is ‘therefore.’ This table lists the indicator words you might encounter.

| Therefore | Since |

| So | Because |

| Thus | For |

| Hence | Is implied by |

| Consequently | For the reason that |

| Implies that | |

| It follows that |

Each argument will likely use only one indicator word or phrase. When the conlusion is at the end, it will generally be preceded by a conclusion indicator. Everything else, then, is a premise. When the conclusion comes at the beginning, the next sentence will usually be introduced by a premise indicator. All of the following sentences will also be premises.

For example, here’s our previous argument rewritten to use a premise indicator:

Susan should do well in Calculus II, because Calculus II will be no harder than Calculus I, and Susan did well in Calculus I.

Sometimes, an argument will contain no indicator words at all. In that case, the best thing to do is to determine which of the premises would logically follow from the others. If there is one, then it is the conclusion. Here is an example:

Spot is a mammal. All dogs are mammals, and Spot is a dog.

The first sentence logically follows from the others, so it is the conclusion. When using this method, we are forced to assume that the person giving the argument is rational and logical, which might not be true.

2.1.3 Non-Arguments

One thing that complicates our task of identifying arguments is that there are many passages that, although they look like arguments, are not arguments. The most common types are:

- Explanations

- Mere asssertions

- Conditional statements

- Loosely connected statements

Explanations can be tricky, because they often use one of our indicator words. Consider this passage:

Abraham Lincoln died because he was shot.

If this were an argument, then the conclusion would be that Abraham Lincoln died, since the other statement is introduced by a premise indicator. If this is an argument, though, it’s a strange one. Do you really think that someone would be trying to prove that Abraham Lincoln died? Surely everyone knows that he is dead. On the other hand, there might be people who don’t know how he died. This passage does not attempt to prove that something is true, but instead attempts to explain why it is true. To determine if a passage is an explanation or an argument, first find the statement that looks like the conclusion. Next, ask yourself if everyone likely already believes that statement to be true. If the answer to that question is yes, then the passage is an explanation.

Mere assertions are obviously not arguments. If a professor tells you simply that you will not get an A in her course this semester, she has not given you an argument. This is because she hasn’t given you any reasons to believe that the statement is true. If there are no premises, then there is no argument.

Conditional statements are sentences that have the form “If…, then….” A conditional statement asserts that if something is true, then something else would be true also. For example, imagine you are told, “If you have the winning lottery ticket, then you will win ten million dollars.” What is being claimed to be true, that you have the winning lottery ticket, or that you will win ten million dollars? Neither. The only thing claimed is the entire conditional. Conditionals can be premises, and they can be conclusions. They can be parts of arguments, but that cannot, on their own, be arguments themselves.

Finally, consider this passage:

I woke up this morning, then took a shower and got dressed. After breakfast, I worked on chapter 2 of the critical thinking text. I then took a break and drank some more coffee….

This might be a description of my day, but it’s not an argument. There’s nothing in the passage that plays the role of a premise or a conclusion. The passage doesn’t attempt to prove anything. Remember that arguments need a conclusion, there must be something that is the statement to be proved. Lacking that, it simply isn’t an argument, no matter how much it looks like one.

2.2 Evaluating Arguments

The first step in evaluating an argument is to determine what kind of argument it is. We initially categorize arguments as either deductive or inductive, defined roughly in terms of their goals. In deductive arguments, the truth of the premises is intended to absolutely establish the truth of the conclusion. For inductive arguments, the truth of the premises is only intended to establish the probable truth of the conclusion. We’ll focus on deductive arguments first, then examine inductive arguments in later chapters.

Once we have established that an argument is deductive, we then ask if it is valid. To say that an argument is valid is to claim that there is a very special logical relationship between the premises and the conclusion, such that if the premises are true, then the conclusion must also be true. Another way to state this is

An argument is valid if and only if it is impossible for the premises to be true and the conclusion false.

An argument is invalid if and only if it is not valid.

Note that claiming that an argument is valid is not the same as claiming that it has a true conclusion, nor is it to claim that the argument has true premises. Claiming that an argument is valid is claiming nothing more that the premises, if they were true , would be enough to make the conclusion true. For example, is the following argument valid or not?

- If pigs fly, then an increase in the minimum wage will be approved next term.

- An increase in the minimum wage will be approved next term.

The argument is indeed valid. If the two premises were true, then the conclusion would have to be true also. What about this argument?

- All dogs are mammals

- Spot is a mammal.

- Spot is a dog.

In this case, both of the premises are true and the conclusion is true. The question to ask, though, is whether the premises absolutely guarantee that the conclusion is true. The answer here is no. The two premises could be true and the conclusion false if Spot were a cat, whale, etc.

Neither of these arguments are good. The second fails because it is invalid. The two premises don’t prove that the conclusion is true. The first argument is valid, however. So, the premises would prove that the conclusion is true, if those premises were themselves true. Unfortunately, (or fortunately, I guess, considering what would be dropping from the sky) pigs don’t fly.

These examples give us two important ways that deductive arguments can fail. The can fail because they are invalid, or because they have at least one false premise. Of course, these are not mutually exclusive, an argument can be both invalid and have a false premise.

If the argument is valid, and has all true premises, then it is a sound argument. Sound arguments always have true conclusions.

A deductively valid argument with all true premises.

Inductive arguments are never valid, since the premises only establish the probable truth of the conclusion. So, we evaluate inductive arguments according to their strength. A strong inductive argument is one in which the truth of the premises really do make the conclusion probably true. An argument is weak if the truth of the premises fail to establish the probable truth of the conclusion.

There is a significant difference between valid/invalid and strong/weak. If an argument is not valid, then it is invalid. The two categories are mutually exclusive and exhaustive. There can be no such thing as an argument being more valid than another valid argument. Validity is all or nothing. Inductive strength, however, is on a continuum. A strong inductive argument can be made stronger with the addition of another premise. More evidence can raise the probability of the conclusion. A valid argument cannot be made more valid with an additional premise. Why not? If the argument is valid, then the premises were enough to absolutely guarantee the truth of the conclusion. Adding another premise won’t give any more guarantee of truth than was already there. If it could, then the guarantee wasn’t absolute before, and the original argument wasn’t valid in the first place.

2.3 Counterexamples

One way to prove an argument to be invalid is to use a counterexample. A counterexample is a consistent story in which the premises are true and the conclusion false. Consider the argument above: