The independent source for health policy research, polling, and news.

Headed Back to School: A Look at the Ongoing Effects of COVID-19 on Children’s Health and Well-Being

Elizabeth Williams and Patrick Drake Published: Aug 05, 2022

Children are now preparing to head back to school for the third time since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. Schools are expected to return in-person this fall, with most experts now agreeing the benefits of in-person learning outweigh the risks of contracting COVID-19 for children. Though children are less likely than adults to develop severe illness, the risk of contracting COVID-19 remains, with some children developing symptoms of long COVID following diagnosis. COVID-19 vaccines provide protection, and all children older than 6 months are now eligible to be vaccinated. However, vaccination rates have stalled and remain low for younger children. At this time, only a few states have vaccine mandates for school staff or students, and no states have school mask mandates, though practices can vary by school district. Emerging COVID-19 variants, like the Omicron subvariant BA.5 that has recently caused a surge in cases, may pose new risks to children and create challenges for the back-to-school season.

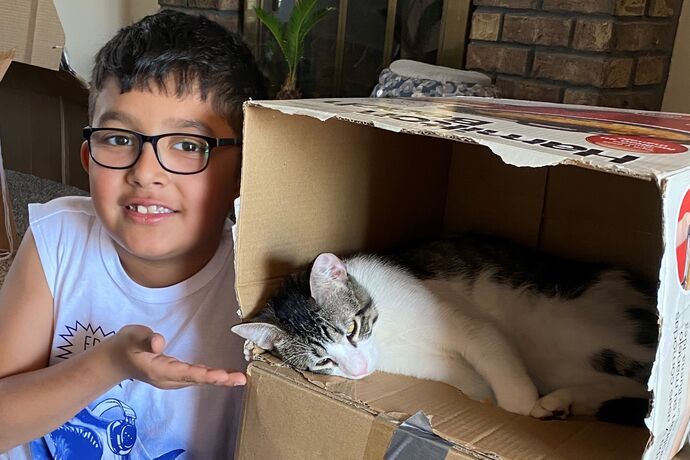

Children may also continue to face challenges due to the ongoing health, economic, and social consequences of the pandemic. Children have been uniquely impacted by the pandemic, having experienced this crisis during important periods of physical, social, and emotional development, with some experiencing the loss of loved ones. While many children have gained health coverage due to federal policies passed during the pandemic, public health measures to reduce the spread of the disease also led to disruptions or changes in service utilization and increased mental health challenges for children.

This brief examines how the COVID-19 pandemic continues to affect children’s physical and mental health, considers what the findings mean for the upcoming back-to-school season, and explores recent policy responses. A companion KFF brief explores economic effects of the pandemic and recent rising costs on households with children. We find households with children have been particularly hard hit by loss of income and food and housing insecurity, which all affect children’s health and well-being.

Children’s Health Care Coverage and Utilization

Despite job losses that threatened employer-sponsored insurance coverage early in the pandemic, uninsured rates have declined likely due to federal policies passed during in the pandemic and the safety net Medicaid and CHIP provided. Following growth in the children’s uninsured rate from 2017 to 2019, data from the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) show that the children’s uninsured rate held steady from 2019 to 2020 and then fell from 5.1% in 2020 to 4.1% in 2021. Just released quarterly NHIS data show the children’s uninsured rate was 3.7% in the first quarter of 2022, which was below the rate in the first quarter of 2021 (4.6%) but a slight uptick from the fourth quarter of 2021 (3.5%), though none of these differences are statistically significant. Administrative data show that children’s enrollment in Medicaid and CHIP increased by 5.2 million enrollees, or 14.7%, between February 2020 and April 2022 (Figure 1). Provisions in the Families First Coronavirus Response Act (FFCRA) require states to provide continuous coverage for Medicaid enrollees until the end of the month in which the public health emergency (PHE) ends in order to receive enhanced federal funding.

Children have missed or delayed preventive care during the pandemic, with a third of adults still reporting one or more children missed or delayed a preventative check-up in the past 12 months (Figure 2). However, the share missing or delaying care is slowly declining, with the share from April 27 – May 9, 2022 (33%) down 3% from almost a year earlier (July 21 – August 2, 2021) according to KFF analysis of the Household Pulse Survey . Adults in households with income less than $25,000 were significantly more likely to have a child that missed, delayed, or skipped a preventive appointment in the past 12 months compared to households with income over $50,000. These data are in line with findings from another study that found households reporting financial hardship were significantly more likely to report missing or delaying children’s preventive visits compared to those not reporting hardships. Hispanic households and households of other racial/ethnic groups were also significantly more likely to have a child that missed, delayed, or skipped a preventive appointment in the past 12 months compared to White households (based on race of the adult respondent).

Telehealth helped to provide access to care, but children with special health care needs and those in rural areas continued to face barriers. Overall, telehealth utilization soared early in the pandemic, but has since declined and has not offset the decreases in service utilization overall. While preventative care rates have increased since early in the pandemic, many children likely still need to catch up on missed routine medical care. One study found almost a quarter of parents reported not catching-up after missing a routine medical visit during the first year of the pandemic. The pandemic may have also exacerbated existing challenges accessing needed care and services for children with special health care needs , and low-income patients or patients in rural areas may have experienced barriers to accessing health care via telehealth .

The pandemic has also led to declines in children’s routine vaccinations, blood lead screenings, and vision screenings. The CDC reported vaccination coverage of all state-required vaccines declined by 1% in the 2020-2021 school year compared to the previous year, and some public health leaders note COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy may be spilling over to routine child immunizations. The CDC also report ed 34% fewer U.S. children had blood lead level testing from January-May 2020 compared to the same period in 2019. Further, data suggest declines in lead screenings during the pandemic may have exacerbated underlying gaps and disparities in early identification and intervention for lower-income households and children of color. Additionally, many children rely on in-school vision screenings to identity vision impairments, and some children went without vision checks while schools managed COVID-19 and turned to remote learning. These screenings are important for children in order to identify problems early; without treatment some conditions can worsen or lead to more serious health complications.

The pandemic has also led to difficulty accessing and disruptions in dental care. Data from the National Survey of Children’s Health (NSCH) show the share of children reporting seeing a dentist or other oral health provider or having a preventive dental visit in the past 12 months declined from 2019 to 2020, the first year of the pandemic (Figure 3). The share of children reporting their teeth are in excellent or very good conditions also declined from 2019 (80%) to 2020 (77%); the share of children reporting no oral health problems also declined but the change was not statistically significant.

Recently released preliminary data for Medicaid/CHIP beneficiaries under age 19 shows steep declines in service utilization early in the pandemic, with utilization then rebounding to a varying degree depending on the service type . Child screening services have rebounded to pre-PHE levels while blood lead screenings and dental services rates remain below per-PHE levels. Telehealth utilization mirrors national trends, increasing rapidly in April 2020 and then beginning to decline in 2021. When comparing the PHE period (March 2020 – January 2022) to the pre-PHE period (January 2018 – February 2020) overall, the data show child screening services and vaccination rates declined by 5% (Figure 4). Blood lead screening services and dental services saw larger declines when comparing the PHE period to before the PHE, declining by 12% and 18% respectively among Medicaid/CHIP children.

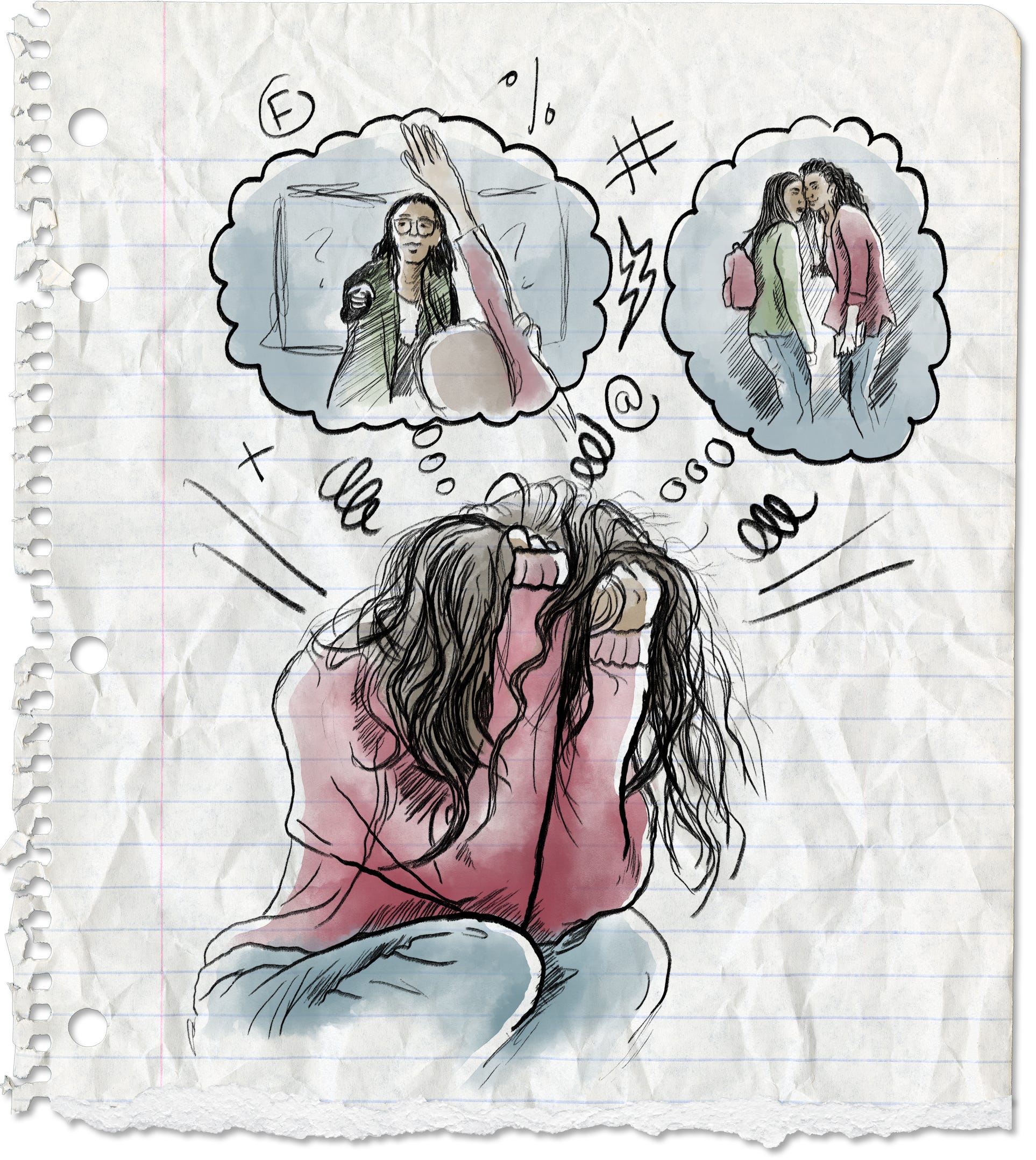

Children’s Mental Health Challenges

Children’s mental health challenges were on the rise even before the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. A recent KFF analysis found the share of adolescents experiencing anxiety and/or depression has increased by one-third from 2016 (12%) to 2020 (16%), although rates in 2020 were similar to 2019. Rates of anxiety and/or depression were more pronounced among adolescent females and White and Hispanic adolescents. A separate survey of high school students in 2021 found that lesbian, gay, or bisexual (LGB) students were more likely to report persistent feelings of sadness and hopelessness than their heterosexual peers. In the past few years, adolescents have experienced worsened emotional health, increased stress, and a lack of peer connection along with increasing rates of drug overdose deaths, self-harm, and eating disorders. Prior to the pandemic, there was also an increase in suicidal thoughts from 14% in 2009 to 19% in 2019.

The pandemic may have worsened children’s mental health or exacerbated existing mental health issues among children . The pandemic caused disruptions in routines and social isolation for children, which can be associated with anxiety and depression and can have implications for mental health later in life. A number of studies show an increase in children’s mental health needs following social isolation due to the pandemic, especially among children who experience adverse childhood experiences (ACEs). KFF analysis found the share of parents responding that adolescents were experiencing anxiety and/or depression held relatively steady from 2019 (15%) to 2020 (16%), the first year of the pandemic. However, the KFF COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor on perspectives of the pandemic at two years found six in ten parents say the pandemic has negatively affected their children’s schooling and over half saying the same about their children’s mental health. Researchers also note it is still too early to fully understand the impact of the pandemic on children’s mental health. The past two years have also seen much economic turmoil, and research has shown that as economic conditions worsen, children’s mental health is negatively impacted. Further, gun violence continues to rise and may lead to negative mental health impacts among children and adolescents. Research suggests that children and adolescents may experience negative mental health impacts, including symptoms of anxiety, in response to school shootings and gun-related deaths in their communities .

Access and utilization of mental health care may have also worsened during the pandemic. Preliminary data for Medicaid/CHIP beneficiaries under age 19 finds utilization of mental health services during the PHE declined by 23% when compared to prior to the pandemic (Figure 4); utilization of substance use disorder services declined by 24% for beneficiaries ages 15-18 for the same time period. The data show utilization of mental health services remains below pre-PHE levels and has seen the smallest improvement compared to other services utilized by Medicaid/CHIP children. Telehealth has played a significant role in providing mental health and substance use services to children early in the pandemic, but has started to decline . The pandemic may have widened existing disparities in access to mental health care for children of color and children in low-income households. NSCH data show 20% of children with mental health needs were not receiving needed care in 2020, with the lowest income children less likely to receive needed mental health services when compared to higher income groups (Figure 5).

Children’s Health and COVID-19

While less likely than adults to develop severe illness, children can contract and spread COVID-19 and children with underlying health conditions are at an increased risk of developing severe illness . Data through July 28, 2022 show there have been over 14 million child COVID-19 cases, accounting for 19% of all cases. Among Medicaid/CHIP enrollees under age 19, 6.4% have received a COVID-19 diagnosis through January 2022. Pediatric hospitalizations peaked during the Omicron surge in January 2022, and children under age 5, who were not yet eligible for vaccination, were hospitalized for COVID-19 at five times the rate during the Delta surge.

Some children who tested positive for the virus are now facing long COVID . A recent meta-analysis found 25% of children and adolescents had ongoing symptoms following COVID-19 infection, and finds the most common symptoms for children were fatigue, shortness of breath, and headaches, with other long COVID symptoms including cognitive difficulties, loss of smell, sore throat, and sore eyes. Another report found a larger share of children with a confirmed COVID-19 case experienced a new or recurring mental health diagnosis compared to children who did not have a confirmed COVID-19 case. However, researchers have noted it can be difficult to distinguish long COVID symptoms to general pandemic-associated symptoms. In addition, a small share of children are experiencing multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C), a serious condition associated with COVID-19 that has impacted almost 9,000 children . A lot of unknowns still surround long COVID in children; it is unclear how long symptoms will last and what impact they will have on children’s long-term health.

COVID-19 vaccines were recently authorized for children between the ages of 6 months and 5 years, making all children 6 months and older eligible to be vaccinated against COVID-19. Vaccination has already peaked for children under the age of 5, and is far below where 5-11 year-olds were at the same point in their eligibility. As of July 20, approximately 544,000 children under the age of 5 (or approximately 2.8%) had received at least one COVID-19 vaccine dose. Vaccinations for children ages 5-11 have stalled, with just 30.3% have been fully vaccinated as of July 27 compared to 60.2% of those ages 12-17. Schools have been important sites for providing access as well as information to help expand vaccination take-up among children, though children under 5 are not yet enrolled in school, limiting this option for younger kids. A recent KFF survey finds most parents of young children newly eligible for a COVID-19 vaccine are reluctant to get them vaccinated, including 43% who say they will “definitely not” do so.

Some children have experienced COVID-19 through the loss of one or more family members due to the virus. A study estimates that, as of June 2022, over 200,000 children in the US have lost one or both parents to COVID-19. Another study found children of color were more likely to experience the loss of a parent or grandparent caregiver when compared to non-Hispanic White children. Losing a parent can have long term impacts on a child’s health, increasing their risk of substance abuse, mental health challenges, poor educational outcomes , and early death . There have been over 1 million COVID-19 deaths in the US, and estimates indicate a 17.5% to 20% increase in bereaved children due to COVID-19, indicating an increased number of grieving children who may need additional supports as they head back to school.

Looking Ahead

Children will be back in the classroom this fall but may continue to face health risks due to their or their teacher’s vaccination status and increasing transmission due to COVID-19 variants. New, more transmissible COVID-19 variants continue to emerge, with the most recent Omicron subvariant BA.5 driving a new wave of infections and reinfections among those who have already had COVID-19. This could lead to challenges for the back-to-school season, especially among young children whose vaccination rates have stalled.

Schools, parents, and children will likely continue to catch up on missed services and loss of instructional time in the upcoming school year. Schools are likely still working to address the loss of instructional time and drops in student achievement due to pandemic-related school disruptions. Further, many children with special education plans experienced missed or delayed services and loss of instructional time during the pandemic. Students with special education plans may be entitled to compensatory services to make up for lost skills due to pandemic related service disruptions, and some children, such as those with disabilities related to long COVID, may be newly eligible for special education services.

To address worsening mental health and barriers to care for children, several measures have been taken or proposed at the state and federal level. Many states have recently enacted legislation to strengthen school based mental health systems, including initiatives such as from hiring more school-based providers to allowing students excused absences for mental health reasons. In July 2022, 988 – a federally mandated crisis number – launched, providing a single three-digit number for individuals in need to access local and state funded crisis centers, and the Biden Administration released a strategy to address the national mental health crisis in May 2022, building on prior actions. Most recently, in response to gun violence, the Bipartisan Safer Communities Act was signed into law and allocates funds towards mental health, including trauma care for school children.

The unwinding of the PHE and expiring federal relief may have implications for children’s health coverage and access to care. The American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) extended eligibility to ACA health insurance subsides for people with incomes over 400% of poverty and increased the amount of assistance for people with lower incomes. However, these subsidies are set to expire at the end of this year without further action from Congress, which would increase premium payments for 13 million Marketplace enrollees. In addition, provisions in the FFCRA providing continuous coverage for Medicaid enrollees will expire with the end of the PHE. Millions of people, including children, could lose coverage when the continuous enrollment requirement ends if they are no longer eligible or face administrative barriers during the process despite remaining eligible. There will likely be variation across states in how many people are able to maintain Medicaid coverage, transition to other coverage, or become uninsured. Lastly, there have also been several policies passed throughout the pandemic to provide financial relief for families with children, but some benefits, like the expanded Child Tax Credit, have expired and the cost of household items is rising, increasing food insecurity and reducing the utility of benefits like SNAP.

- Coronavirus (COVID-19)

- Coronavirus

Also of Interest

- A Look at the Economic Effects of the Pandemic for Children

- Recent Trends in Mental Health and Substance Use Concerns Among Adolescents

- Mental Health and Substance Use Considerations Among Children During the COVID-19 Pandemic

- COVID-19 Vaccination Rates Among Children Under 5 Have Peaked and Are Decreasing Just Weeks Into Their Eligibility

How to Write About Coronavirus in a College Essay

Students can share how they navigated life during the coronavirus pandemic in a full-length essay or an optional supplement.

Writing About COVID-19 in College Essays

Getty Images

Experts say students should be honest and not limit themselves to merely their experiences with the pandemic.

The global impact of COVID-19, the disease caused by the novel coronavirus, means colleges and prospective students alike are in for an admissions cycle like no other. Both face unprecedented challenges and questions as they grapple with their respective futures amid the ongoing fallout of the pandemic.

Colleges must examine applicants without the aid of standardized test scores for many – a factor that prompted many schools to go test-optional for now . Even grades, a significant component of a college application, may be hard to interpret with some high schools adopting pass-fail classes last spring due to the pandemic. Major college admissions factors are suddenly skewed.

"I can't help but think other (admissions) factors are going to matter more," says Ethan Sawyer, founder of the College Essay Guy, a website that offers free and paid essay-writing resources.

College essays and letters of recommendation , Sawyer says, are likely to carry more weight than ever in this admissions cycle. And many essays will likely focus on how the pandemic shaped students' lives throughout an often tumultuous 2020.

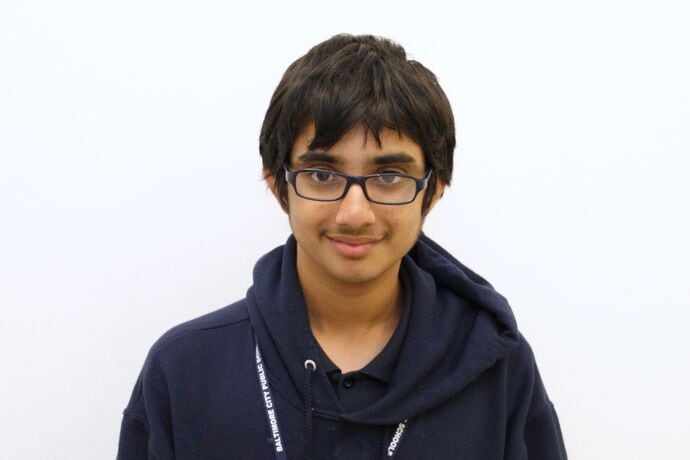

But before writing a college essay focused on the coronavirus, students should explore whether it's the best topic for them.

Writing About COVID-19 for a College Application

Much of daily life has been colored by the coronavirus. Virtual learning is the norm at many colleges and high schools, many extracurriculars have vanished and social lives have stalled for students complying with measures to stop the spread of COVID-19.

"For some young people, the pandemic took away what they envisioned as their senior year," says Robert Alexander, dean of admissions, financial aid and enrollment management at the University of Rochester in New York. "Maybe that's a spot on a varsity athletic team or the lead role in the fall play. And it's OK for them to mourn what should have been and what they feel like they lost, but more important is how are they making the most of the opportunities they do have?"

That question, Alexander says, is what colleges want answered if students choose to address COVID-19 in their college essay.

But the question of whether a student should write about the coronavirus is tricky. The answer depends largely on the student.

"In general, I don't think students should write about COVID-19 in their main personal statement for their application," Robin Miller, master college admissions counselor at IvyWise, a college counseling company, wrote in an email.

"Certainly, there may be exceptions to this based on a student's individual experience, but since the personal essay is the main place in the application where the student can really allow their voice to be heard and share insight into who they are as an individual, there are likely many other topics they can choose to write about that are more distinctive and unique than COVID-19," Miller says.

Opinions among admissions experts vary on whether to write about the likely popular topic of the pandemic.

"If your essay communicates something positive, unique, and compelling about you in an interesting and eloquent way, go for it," Carolyn Pippen, principal college admissions counselor at IvyWise, wrote in an email. She adds that students shouldn't be dissuaded from writing about a topic merely because it's common, noting that "topics are bound to repeat, no matter how hard we try to avoid it."

Above all, she urges honesty.

"If your experience within the context of the pandemic has been truly unique, then write about that experience, and the standing out will take care of itself," Pippen says. "If your experience has been generally the same as most other students in your context, then trying to find a unique angle can easily cross the line into exploiting a tragedy, or at least appearing as though you have."

But focusing entirely on the pandemic can limit a student to a single story and narrow who they are in an application, Sawyer says. "There are so many wonderful possibilities for what you can say about yourself outside of your experience within the pandemic."

He notes that passions, strengths, career interests and personal identity are among the multitude of essay topic options available to applicants and encourages them to probe their values to help determine the topic that matters most to them – and write about it.

That doesn't mean the pandemic experience has to be ignored if applicants feel the need to write about it.

Writing About Coronavirus in Main and Supplemental Essays

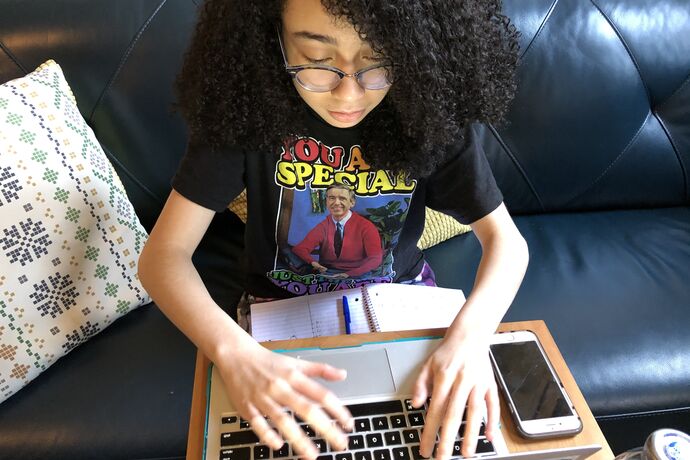

Students can choose to write a full-length college essay on the coronavirus or summarize their experience in a shorter form.

To help students explain how the pandemic affected them, The Common App has added an optional section to address this topic. Applicants have 250 words to describe their pandemic experience and the personal and academic impact of COVID-19.

"That's not a trick question, and there's no right or wrong answer," Alexander says. Colleges want to know, he adds, how students navigated the pandemic, how they prioritized their time, what responsibilities they took on and what they learned along the way.

If students can distill all of the above information into 250 words, there's likely no need to write about it in a full-length college essay, experts say. And applicants whose lives were not heavily altered by the pandemic may even choose to skip the optional COVID-19 question.

"This space is best used to discuss hardship and/or significant challenges that the student and/or the student's family experienced as a result of COVID-19 and how they have responded to those difficulties," Miller notes. Using the section to acknowledge a lack of impact, she adds, "could be perceived as trite and lacking insight, despite the good intentions of the applicant."

To guard against this lack of awareness, Sawyer encourages students to tap someone they trust to review their writing , whether it's the 250-word Common App response or the full-length essay.

Experts tend to agree that the short-form approach to this as an essay topic works better, but there are exceptions. And if a student does have a coronavirus story that he or she feels must be told, Alexander encourages the writer to be authentic in the essay.

"My advice for an essay about COVID-19 is the same as my advice about an essay for any topic – and that is, don't write what you think we want to read or hear," Alexander says. "Write what really changed you and that story that now is yours and yours alone to tell."

Sawyer urges students to ask themselves, "What's the sentence that only I can write?" He also encourages students to remember that the pandemic is only a chapter of their lives and not the whole book.

Miller, who cautions against writing a full-length essay on the coronavirus, says that if students choose to do so they should have a conversation with their high school counselor about whether that's the right move. And if students choose to proceed with COVID-19 as a topic, she says they need to be clear, detailed and insightful about what they learned and how they adapted along the way.

"Approaching the essay in this manner will provide important balance while demonstrating personal growth and vulnerability," Miller says.

Pippen encourages students to remember that they are in an unprecedented time for college admissions.

"It is important to keep in mind with all of these (admission) factors that no colleges have ever had to consider them this way in the selection process, if at all," Pippen says. "They have had very little time to calibrate their evaluations of different application components within their offices, let alone across institutions. This means that colleges will all be handling the admissions process a little bit differently, and their approaches may even evolve over the course of the admissions cycle."

Searching for a college? Get our complete rankings of Best Colleges.

10 Ways to Discover College Essay Ideas

Tags: students , colleges , college admissions , college applications , college search , Coronavirus

2024 Best Colleges

Search for your perfect fit with the U.S. News rankings of colleges and universities.

College Admissions: Get a Step Ahead!

Sign up to receive the latest updates from U.S. News & World Report and our trusted partners and sponsors. By clicking submit, you are agreeing to our Terms and Conditions & Privacy Policy .

Ask an Alum: Making the Most Out of College

You May Also Like

Scholarships for lesser-known sports.

Sarah Wood May 15, 2024

Should Students Submit Test Scores?

Sarah Wood May 13, 2024

Poll: Antisemitism a Problem on Campus

Lauren Camera May 13, 2024

Federal vs. Private Parent Student Loans

Erika Giovanetti May 9, 2024

14 Colleges With Great Food Options

Sarah Wood May 8, 2024

Colleges With Religious Affiliations

Anayat Durrani May 8, 2024

Protests Threaten Campus Graduations

Aneeta Mathur-Ashton May 6, 2024

Protesting on Campus: What to Know

Sarah Wood May 6, 2024

Lawmakers Ramp Up Response to Unrest

Aneeta Mathur-Ashton May 3, 2024

University Commencements Must Go On

Eric J. Gertler May 3, 2024

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

How schools and students have changed after 2 years of the pandemic

Anya Kamenetz

It's been two years since schools shut down around the world, and now masks are coming off in a move back to normalcy. What effect has the pandemic had on students' learning and development?

Copyright © 2022 NPR. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use and permissions pages at www.npr.org for further information.

NPR transcripts are created on a rush deadline by an NPR contractor. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of NPR’s programming is the audio record.

Health Issues

COVID-19 & School: Keeping Kids Safe

At the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, students had their world turned upside down. Schools closed their doors as the virus spread quickly through communities. Since then, we have learned a lot.

One of the biggest lessons: students learn best in-person, and many are also exposed to vital relationships, resources, and other experiences they need to thrive at school.

A recent federal study found that for all students, reading and math scores are lower this year than they were in 2020. Scores were worst among students who were struggling before COVID. Daily attendance can make a big impact on long-term success and good health.

Read on for ways to keep your child or teen healthy and in school.

Vaccines & boosters

The AAP recommends COVID vaccination for everyone 6 months of age and older. Kids who are fully vaccinated are at a much lower risk of missing school due to being ill with COVID-19. Fully vaccinated kids don’t have to spend more time away from learning, friendships, sports and other activities.

Remember that fully vaccinated people can still become infected and spread the virus to others, but less than if they were not vaccinated. If your child or teen has recovered from COVID illness, they should still get the vaccine to reduce the risk of getting sick again.

Your child or teen should be up-to-date on all recommended vaccines, including flu, HPV, meningococcal, measles and other vaccines. Routine childhood and adolescent immunizations can be given with COVID-19 vaccines or in the days before and after. Getting caught up will avoid outbreaks of other illnesses that could keep your kids home from school. See Back to School: How to Help Your Child Have a Healthy Year for more information.

Masks, testing & staying home when sick

Masks are still a good idea. Although not required in many school districts, indoor masking is still beneficial. Masks help stop the spread of COVID—and other infections like the common cold or the flu . It is especially important to use well-fitting masks if your child is ineligible for the vaccine for medical reasons; immunocompromised; if a family member is at high risk; or there is a high rate of COVID in your community. Masks can help protect kids with immune compromise or disabilities from getting COVID, so they won’t have to miss school.

Most children with medical conditions can wear face masks with practice, support and role-modeling by adults. Ask your pediatrician if:

- you need help choosing a mask or personal protective equipment that offers the best fit and comfort based on a child’s medical or developmental needs or

- you have concerns that a mask cannot be worn and want to explore all options.

Planning for outbreaks. Right now, COVID variants and other viruses are circulating. Schools need to plan for outbreaks that may occur. People who have symptoms or are at high risk should be tested, following Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) guidelines . And if you get a negative result on an at-home COVID-19 antigen test, the Food and Drug Administration advises repeat testing. This is because tests can sometimes show false-negative results.

COVID symptoms & what to do:

School-based support for students.

Many families will be recovering from the impacts of the pandemic for years to come. Here are some of the supports that families can access through school.

- Resources for families affected by housing or food insecurity

- Access to high-speed internet and devices to complete schoolwork

- Support, testing and necessary accommodations for students with an Individualized Education Program (IEP) or chronic, high-risk medical conditions

- Emotional and behavioral support and resources for students with anxiety , distress, suicidal thoughts and other needs

If your child needs support, do not hesitate to talk with your pediatrician and school staff (including school nurses). They are there to help you explore options and connect your family with support and resources.

More information

- Back to School: Tips to Help Kids Have a Healthy Year

- COVID-19 Guidance for Safe Schools and Promotion of In-Person Learning (AAP.org)

British Council Americas

- Show search Search Search Close search

- New Ways of Teaching

- Tips and Ideas

Returning to school after COVID-19?

Have you thought about what it will be like to return to face-to-face classes? In this article, we offer all relevant tips to return to class safely, to continue demonstrating your potential and your teaching skills.

Author: Andrew Foster.

Getting started

Finding out what students have been doing can help you to understand their needs now they are back at school.

Ask and answer: Ask them some questions about their time out of school, in either English or their home language (depending on their level). Write the questions on the board. Ask them to ask and answer the questions with a partner. Older students can then write on a piece of paper that you can collect and read afterwards. Let them choose which questions they want to talk about.

Choose some of the questions below and add your own.

- What did you do when the school was closed?

- What was good?

- What was difficult?

- Did you do anything different with your family or friends?

- Did you watch any TV programmes or listen to the radio in English?

- Did you use any websites or mobile apps for learning English?

- Did you speak in English at home? Who did you speak with?

- Did you read parts of your English coursebook or other books in English?

Ask some of the students to share their answers if they are too young to write their answers. Give encouragement and recognise any difficulties they have had. Use their replies to plan support for those learners who need it. After class, read anything that is written down and write a short reply to each student if you have time.

True or false: Ask students to write five sentences about what they did while school was closed, most true, but one or two that are not true. In pairs or groups, one student reads the sentences and the others listen to all, and then guess which are true and which are invented.

Ideas for classroom management and learning

Adapting activities: Your school or country may have important rules to protect teachers, staff, learners and the community. Think about how new rules affect activities you can do with students in the classroom. If some are not suitable now, can you adapt or replace them with safer activities? For example:

- Pair work or groupwork might need more space, which means that students find it harder to hear their partner(s). Try setting up activities where one student is the speaker and the other responds with signals (for example, for ‘Yes’, ‘No’ or ‘I don’t know’) or encourage learners to listen and use a number of brief, but suitable, responses which you teach them before they listen.

- Try some active listening tasks where the listener doesn’t speak but notes down the key points of what their partner says about a topic (for example, ‘Three things I liked or didn’t like about staying at home’. What were the three things? Were they likes or dislikes?).

Using the environment: If your school has outdoor space that is safe for children, can you use it? Is there anything there that you can use for language learning and to allow learners to use the space more? For example, could you use things in the area around the school for describing things by place, size or other description? Could you make a treasure hunt, using questions in English for children to find and answer?

Catching up: If learners have lost a lot of learning time, trying to cover the set syllabus may seem too much. Make sure that you keep checking what students are able to do with the language that they study. This may be through pair speaking, writing to another student, which you monitor, or a regular quiz.

Thinking about the future

Has any useful learning come from the experience of the closure? What could help to support learners when school is open, and which could be useful if any learners can’t come to school in the future? Are there things you can set up now to make it easier if school has to close again?

Try to find out if any learners or their parent need guidance to use information or activities that are sent to them. Can you give more time or attention to children or parents who could not access any support provided outside the school?

External links

- UNESCO guidance on preparing to return to school:

- UNESCO IIEP guidance on returning to school:

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Front Psychol

Stress-Related Growth in Adolescents Returning to School After COVID-19 School Closure

1 Centre for Positive Psychology, Melbourne Graduate School of Education, University of Melbourne, Parkville, VIC, Australia

Kelly-Ann Allen

2 Faculty of Education, Monash University, Clayton, VIC, Australia

Gökmen Arslan

3 Department of Psychological Counselling and Guidance, Burdur Mehmet Akif Ersoy University, Burdur, Turkey

4 International Network on Personal Meaning, Toronto, ON, Canada

Associated Data

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

The move to remote learning during COVID-19 has impacted billions of students. While research shows that school closure, and the pandemic more generally, has led to student distress, the possibility that these disruptions can also prompt growth in is a worthwhile question to investigate. The current study examined stress-related growth (SRG) in a sample of students returning to campus after a period of COVID-19 remote learning ( n = 404, age = 13–18). The degree to which well-being skills were taught at school (i.e., positive education) before the COVID-19 outbreak and student levels of SRG upon returning to campus was tested via structural equation modeling. Positive reappraisal, emotional processing, and strengths use in students were examined as mediators. The model provided a good fit [ χ 2 = 5.37, df = 3, p = 0.146, RMSEA = 0.044 (90% CI = 0.00–0.10), SRMR = 0.012, CFI = 99, TLI = 0.99] with 56% of the variance in SRG explained. Positive education explained 15% of the variance in cognitive reappraisal, 7% in emotional processing, and 16% in student strengths use during remote learning. The results are discussed using a positive education paradigm with implications for teaching well-being skills at school to foster growth through adversity and assist in times of crisis.

Introduction

Novel coronavirus (COVID-19) spread rapidly across the globe in 2020, infecting more than 70 million people and causing more than 1.5 million deaths at the time of submitting this paper (December 8, 2020; World Health Organization, 2020a ). The restrictions and disruptions stemming from this public health crisis have compromised the mental health of young people ( Hawke et al., 2020 ; UNICEF, 2020 ; Yeasmin et al., 2020 ; Zhou et al., 2020 ). A review assessing the mental health impact of COVID-19 on 6–21-year-olds ( n = 51 articles) found levels of depression and anxiety ranging between 11.78 and 47.85% across China, the United States of America, Europe, and South America ( Marques de Miranda et al., 2020 ). Researchers have also identified moderate levels of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in youth samples during the COVID-19 pandemic ( Guo et al., 2020 ; Liang et al., 2020 ; Wang et al., 2020 ).

Adolescence is a critical life stage for identity formation ( Allen and McKenzie, 2015 ; Crocetti, 2017 ) where teenagers strive for mastery and autonomy ( Featherman et al., 2019 ), individuate from their parents ( Levpuscek, 2006 ), and gravitate toward their peer groups to have their social and esteem needs met ( Allen and Loeb, 2015 ). The pandemic has drastically curtailed the conditions for teens to meet their developmental needs ( Loades et al., 2020 ). Gou et al. (2020 , p. 2) argue that adolescents are “more vulnerable than adults to mental health problems, in particular during a lockdown, because they are in a transition phase… with increasing importance of peers, and struggling with their often brittle self-esteem.”

In addition to the researching psychological distress arising from COVID-19, it is also important to identify positive outcomes that may arise through this pandemic. Dvorsky et al. (2020) caution that research focused only on distress may create a gap in knowledge about the resilience processes adopted by young people. In line with this, Bruining et al. (2020 , p. 1) advocate for research to keep “an open scientific mind” and include “positive hypotheses.” Waters et al. (2021) argue that researching distress during COVID-19 need not come at the expense of investigating how people can be strengthened through the pandemic. Hawke et al. (2020) , for example, found that more than 40% of their teen and early adult sample reported improved social relationships, greater self-reflection, and greater self-care.

Focusing on adolescents and adopting positive hypotheses , the current study will examine the degree to which a positive education intervention taught at school prior to the COVID-19 outbreak had an influence on three coping approaches during remote learning (i.e., positive reappraisal, emotional processing, and strengths use) and on student levels of stress-related growth (SRG) upon returning to school.

Can Adolescents Grow Through the COVID-19 Crisis? The Role of Positive Education

The calls for positive youth outcomes to be investigated during COVID-19 ( Bruining et al., 2020 ; Dvorsky et al., 2020 ; Waters et al., 2020 ) align with the field of positive education. Positive education is an applied science that weaves the research from positive psychology into schools following the principles of prevention-based psychology (e.g., teaching skills that enable students to prevent distress) and promotion-based psychology (e.g., teaching skills that enable students to build well-being; Slemp et al., 2017 ; Waters et al., 2017 ).

With the WHO focusing on student well-being as a top priority during the COVID-19 crisis ( World Health Organization, 2020b ), positive education is an essential research area. Burke and Arslan (2020 , p. 137) argue that COVID-19 could “become a springboard for positive change, especially in schools that draw on positive education research to …foster students’ social-emotional health.”

The field of positive education has developed a host of interventions that teach students the skills to support their mental health including mindfulness ( Waters et al., 2015 ), gratitude ( Froh et al., 2008 ), progressive relaxation ( Matsumoto and Smith, 2001 ), sense of belonging ( Allen and Kern, 2019 ) and, more specific to the current study, coping skills ( Collins et al., 2014 ; Frydenberg, 2020 ), cognitive reframing ( Sinclair, 2016 ), emotional management skills ( Brackett et al., 2012 ), and strengths use ( Quinlan et al., 2015 ). While prior research has shown that students can be successfully taught the skills to reduce ill-being and promote well-being, this research has been conducted predominantly with mainstream and at-risk students (for recent reviews, see Waters and Loton, 2019 ; Owens and Waters, 2020 ). Comparatively little research in positive education has been conducted with students who have experienced trauma ( Brunzell et al., 2019 ) yet, in the context of a global pandemic, the risks of trauma are amplified, hence is it worth considering the role of positive education in this context.

When it comes to trauma, a number of interventions have been developed based on cognitive behavioral principles (for example, see Little et al., 2011 ). These interventions teach students about trauma exposure and stress responses and then show students how to utilize skill such as relaxation, cognitive reframing, and social problem-solving skills to deal with PTSD symptoms ( Jaycox et al., 2010 ). Positive education ınterventions for trauma have been used with students who have experienced natural disasters, have been abused, have witnessed violence, or have been the victims of violent acts. These interventions have been shown to reduce depression, anxiety, and PTSD in students ( Stein et al., 2003 ; Cohen et al., 2006 ; National Child Traumatic Stress Network, 2008 ; Walker, 2008 ; Jaycox et al., 2010 ).

The findings above, that positive education interventions help reduce the negative symptomology experienced by students in the aftermath of trauma begs the question as to whether these interventions can also promote positive changes following adversity. After first coining the term “ stress-related growth ,” Vaughn et al. (2009 , p. 131) defined it as the “experience of deriving benefits from encountering stressful circumstances” and asserted that SRG goes beyond merely a state of recovery following adversity. SRG also includes the development of a higher level of ongoing adaptive functioning. Those who experience SRG come out of the adversity stronger, with a deeper sense of meaning, new coping skills, broadened perspectives and newly developed personal resources ( Park and Fenster, 2004 ; Park, 2013 ).

In turning to see if positive education interventions can foster SRG, two studies were identified in the literature. Ullrich and Lutgendorf (2002) conducted a journaling intervention with undergraduate students (mean age = 20.05 years) who were asked to write about a stressful or traumatic event in their life twice a week for 1 month. Results showed that engaging in both emotion-based and cognitive-based reflection helped students see the adversity’s benefits and increase SRG. In Dolbier et al. (2010) study, college students (median age = 21 years) were placed in an intervention group or a waitlist control group. The intervention group participated in a 4-week resilience program that taught problem-focused and emotion-focused coping strategies. At the end of the program, the intervention group showed more significant increases in SRG from pre- to post-test than the waitlist control group. The findings from these two studies suggest that positive education interventions can lead to SRG. However, given that both studies used college students, there remains a gap in researcher as to whether positive interventions can promote SRG for school-aged students. As such, the question remains, “Can positive education interventions help students grow from their experience of adversity?”

Cross-sectional and longitudinal findings from traumatology, coping psychology, and adolescent psychology have shown that young people can grow through adversity. Indeed, considerable research has shown the transformative capacity within young people to use aversive experiences as a platform for growth ( Levine et al., 2008 ; Meyerson et al., 2011 ). Children and teens have been found to grow following experiences such as severe illness (e.g., cancer; Currier et al., 2009 ), terrorist attacks ( Laufer, 2006 ), natural disasters (e.g., floods and earthquakes; Hafstad et al., 2010 ), death of a parent ( Wolchik et al., 2009 ), war ( Kimhi et al., 2010 ), abuse ( Ickovics et al., 2006 ), minority stress ( Vaughn et al., 2009 ), and even everyday stressors ( Mansfield and Diamond, 2017 ). These studies were not intervention-based but do provide consistent evidence that young people are capable of experiencing stress related growth. The findings above, showing that young people can use adversity as a springboard for growth, leads to our first hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1: Adolescents will demonstrate stress-related growth during COVID-19.

The bulk of evidence for SRG in youth samples comes from cross-sectional or longitudinal research rather than intervention-based studies. While there has been intervention-based research working with school-aged students focusing on reducing PTSD, there has been none on promoting SRG. Moreover, the CBT interventions outlined above were run with students after the trauma had occurred. As there is no research looking at whether learning skills through a positive education intervention before a trauma influences the likelihood of SRG during or following a crisis. Drawing on the principle of promotion-based positive education, the current study seeks to explore whether teaching well-being skills to students before COVID-19 was significantly related to SRG during the global pandemic. Aligning with past research findings that the coping skills existing in individuals before a traumatic event are significant predictors of growth during and after trauma ( Park and Fenster, 2004 ; Prati and Pietrantoni, 2009 ; Zavala and Waters, 2020 ), hypothesis two is put forward:

Hypothesis 2: The degree to which students were taught positive education skills at school prior to the pandemic will be directly and positively related to their SRG upon school entry.

Coping Approaches in Remote Lockdown and SRG Upon School Re-entry

The possibility that the stressors of COVID-19 can trigger SRG in teenagers leads to the question of what factors might increase the chances of this growth. With reduced social contact during the pandemic, Wang et al. (2020 , p. 40) suggest that the development of intrapersonal skills are needed to optimize “psychological, emotional and behavioral adjustment.” Examples provided by Wang et al. (2020) include: (1) cognitive approaches that help students challenge unhelpful thoughts and (2) emotional approaches that give students the ability to express and handle their emotions. In research on everyday stressors with teenagers, Mansfield and Diamond (2017) found that cognitive-affective resources are significantly linked to SRG.

The coping factors examined in the current study were guided by the findings of Mansfield and Diamond (2017) together with the findings from college samples that cognitive reflection and emotional reflection ( Ullrich and Lutgendorf, 2002 ) as well as problem-focused and emotion-focused coping ( Dolbier et al., 2010 ) are significantly related to SRG. The recommendations of Wang et al. (2020) to investigate a student’s “psychological, emotional and behavioral adjustment” were also followed. The effect of three well-known coping skills during remote learning on SRG was examined: a cognitive skill (positive reappraisal), an emotional technique (emotional processing), and a behavioral skill – (strengths use).

Transitioning back to school, although a welcome move for many students, is still likely to be experienced as a source of distress ( Capurso et al., 2020 ). Re-entry requires a process of adjustment and a rupture of the “new-normal” routines that students had experienced with their families at home ( Pelaez and Novak, 2020 ). Some students may experience separation anxiety, others may be afraid of contracting the virus, and others may find the pace and noise of school unsettling ( Levinson et al., 2020 ; Pelaez and Novak, 2020 ). Even for those who adjust well, a “post-lockdown school” takes time and energy to get used to – wearing masks, lining up for daily temperature checks, washing hands upon entry into classrooms, and maintaining a 1.5-meter distance from their friends are foreign for most students and will require psycho-emotional processing ( Levinson et al., 2020 ). The better a student has coped during the period of remote learning (through positive reappraisal, emotional processing, and strengths use), the higher the chance they may have of growing through stress when they return to campus.

Positive Reappraisal

Positive reappraisal is a meaning-based, adaptive cognitive process that motivates an individual to consider whether a good outcome can emerge from a stressful experience ( Carver et al., 1989 ; Folkman and Moskowitz, 2000 ). Positively reappraising a stressful experience in ways that look for any beneficial outcomes ( Garland et al., 2011 ) has been shown to make people more aware of their values in life and to act upon those values ( Folkman and Moskowitz, 2000 ), thus, in doing so, it is linked to a deeper sense of meaning in life emerging from the stressor ( Rood et al., 2012a ). Positive reappraisal has been shown to reduce distress and improve mental health outcomes across various crises such as chronic illness, war, and rape ( Sears et al., 2003 ; Helgeson et al., 2006 ). Concerning the COVID-19 crisis, Xie et al. (2020) assert that an optimistic outlook may be critical. The reverse pattern has also been found in two student samples ( Liang et al., 2020 ; Ye et al., 2020 ) during the coronavirus crisis. Negative rumination (i.e., repeated negative thoughts about the virus) has been related to higher distress levels. Learning how to re-construct obstacles into opportunities during COVID-19 (e.g., “I miss seeing my teachers in person, but I am learning to be a more independent student”) can help young people to emerge from the crisis with new mindsets and skillsets. This logic leads to the third hypothesis of the current study:

Hypothesis 3: Higher use of positive reappraisal during remote learning will be significantly related to higher levels of stress-related growth when students return to school.

Emotional Processing

Emotional processing is described as the technique of actively processing and expressing one’s emotions during times of stress (in contrast to avoidance; Stanton et al., 2000 ). Emotional processing is a positive factor in helping children cope with and grow through adverse events such as grief ( McFerran et al., 2010 ), identity conflict ( Davis et al., 2015 ), and natural disasters ( Prinstein et al., 1996 ). To date, the role of emotional processing during a pandemic has not been explicitly studied; however, there is indirect research to suggest the value of this coping approach. For example, students in Chen et al. (2020) study who knew how to manage their stress levels displayed fewer symptoms of depression during COVID-19. Similarly, in Duan et al. (2020) study, emotion-focused coping during the coronavirus crisis was significantly related to anxiety levels in students from Grade 3 to Grade 12. These findings lead to Hypothesis four:

Hypothesis 4: Higher use of emotional processing techniques during remote learning will be significantly related to higher levels of stress-related growth when students return to school.

Strengths Use

The third coping factor to be examined in the current study is the skill of strengths use. Strengths are defined as positive capacities and characteristics that are energizing and authentic ( Peterson and Seligman, 2004 ). Strengths use is described by Govindji and Linley (2007) as the extent to which individuals put their strengths into actions and draw upon their strengths in various settings. Shoshani and Slone (2016) showed that strengths have a moderating role in the relationship between political violence and PTSD for young people exposed to lengthy periods of war and political conflict. In an adult sample, strengths were found to enhance PTG in earthquake survivors ( Duan and Guo, 2015 ). In the current COVID-19 pandemic, Rashid and McGrath (2020 , p. 116) suggest that “using our strengths can enhance our immunity to stressors by building protective and pragmatic habits and actions.” Adding to this, research shows that strengths use leads to an increased sense of control/self-efficacy in young people ( Loton and Waters, 2018 ), which may be an important outcome to combat the “uncertainty distress” ( Freeston et al., 2020 ) that many young people are currently feeling ( Demkowicz et al., 2020 ). The research and reasoning outlined above about strengths use has been used to formulate Hypothesis five.

Hypothesis 5: Higher strengths use during remote learning will be significantly related to higher levels of stress-related growth when students return to school.

Having established that the three coping approaches above are likely to foster SRG during COVID-19, the final question remaining is whether positive education interventions can increase the use of these coping approaches. Garland et al. (2011) and Pogrebtsova et al. (2017) found that mindfulness interventions increase positive reappraisal. In a related outcome, positive education interventions have been shown to help students better understand their explanatory styles (i.e., how they interpret adversity; Quayle et al., 2001 ; Rooney et al., 2013 ). Adding to this, emotional processing is significantly enhanced in students due to undertaking various positive education interventions ( Qualter et al., 2007 ; Brackett et al., 2012 ; Castillo et al., 2013 ). Finally, positive education interventions have been shown to increase strengths use ( Marques et al., 2011 ; Quinlan et al., 2015 ; White and Waters, 2015 ). These findings inform our final two study hypotheses.

Hypothesis 6: The degree to which students were taught positive education skills at school prior to the pandemic will be directly and positively related to their use of positive reappraisal, emotional processing, and strengths use during remote learning.

Hypothesis 7: The degree to which students were taught positive education skills at school prior to the pandemic will be indirectly and positively related to SRG upon school entry via their use of positive reappraisal, emotional processing, and strengths use during remote learning.

Materials and Methods

Participants.

After receiving Ethics approval from the Human Ethics Research Committee at Monash University, data were collected from 404 students at a large independent school in New South Wales, Australia. Participants were recruited from Grades 7 to 12 and ranged in age from 11 to 18 ( M = 14.75, SD = 1.59; 50.2% female/46.8% male and 3% identified as non-/other gendered or declined to answer). The vast majority of the sample (93.1%) listed English as their primary language. Prior to conducting the survey, parents were sent information packages explaining the nature of the research, resources available to students feeling distress, security and anonymity of the data collected, and the opt-out process. Participation was voluntary and students could opt out at any time.

Students in the current study were part of a whole-school positive education intervention that focuses on six key pathways to well-being: strengths, emotional management, attention and awareness, relationships, coping, and habits and goals ( Waters, 2019 ; Waters and Loton, 2019 ). The first letter of each of these six pathways forms the acronym “SEARCH.” In 2019, all teachers at the school were trained in the “SEARCH” pathways and given activities to run in classrooms that help students learn skill that allow them to build up the six pathways of strengths (e.g., strengths pathways: strength surveys and strengths challenges), managing their emotions (e.g., learning how to label the full spectrum of emotions and identifying emotions through a mood-meter), focusing their attention (e.g., mindfulness), building their relationships (e.g., active-constructive responding), coping (e.g., cognitive reframing and breathing techniques), and building habits and setting goals (e.g., if-then intentions).

Positive Education

Students rated the degree to which they had been taught positive education skills at school prior to the COVID-19 pandemic along the six pathways of the SEARCH framework. Students rated the degree to which they had been taught how to use their strengths, manage their emotions, and build their capacity to have awareness and so on, prior to COVID-19. There was one item per SEARCH pathway (e.g., “Prior to COVID-19, to what degree did your school teach you about how to understand and manage your emotions?”). The alpha reliability for this scale was 0.91.

Students rated the degree to which they engaged in emotional processing techniques (“I took time to figure out what I was feeling,” “I thought about my feelings to get a thorough understanding of them,” etc.) during the COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown using the 4-item scale Emotional Processing Scale ( Stanton et al., 2000 ). Answers were given on a 4-point scale from “I didn’t do this at all” to “I did this a lot.” The internal reliability of the scale was α = 0.78.

Positive reappraisal was measured using the 4-item “Positive Reinterpretation and Growth Scale” of the COPE inventory ( Carver et al., 1989 ). Students were asked to rate the degree to which they engaged in positive reappraisal techniques (“I looked for something good in what was happening,” “I learned something from the experience,” etc.) during the COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown. Answers were given on a 4-point scale from “I didn’t do this at all” to “I did this a lot.” The internal reliability of the scale was α = 0.82.

Students rated the degree to which they used their strengths during the remote learning using an adapted three-item version of the Strengths Use Scale ( Govindji and Linley, 2007 ), a 14-item self-report scale designed to measure individual strengths use (e.g., items included “During remote learning and family lockdown I had lots of different ways to use my strengths,” “During remote learning and family lockdown I achieved what I wanted by using my strengths,” etc.). Answers were given on a 5-point scale from 1“Not at all” to 5 “A lot.” The internal reliability of the scale was α = 0.89.

Stress-Related Growth

Using an abbreviated Stress-Related Growth Scale ( Vaughn et al., 2009 ), students were asked to think about whether their experience with COVID-19 changed them in any specific ways, including internal growth (“I have learned to deal better with uncertainty,” “I learned not to let small hassles bother me the way they used to,” etc.) and social growth (“I reached out and helped others,” “I have learned to appreciate the strength of others who have had a difficult life,” etc.). Answers were given on a 5-point Likert scale from “Not at all” to “A lot.” The internal reliability of the scale was α = 0.85.

For students who elected to participate in this study, the school distributed the survey via an email link on the Qualtrics platform distributed by the teachers during the students’ mentor time. The first screen of the form provided information on the survey and reminded students that they could opt out or stop at any time. If distressed, several resources were made available, including teachers at the school, parents, and helplines. Teachers were present during the entire duration of the survey to provide clarification on instructions and/or support for students feeling distressed.

The data collected from the survey were anonymized and shared with the participating school administrators, and this was clearly stated to all participants of the study, including teachers, parents, and students. No personally identifiable information was made available in the data asset provided to the school. The original data source from the survey will be stored in a secure, password-protected file at Monash University for 5 years.

Through the survey, students were asked to reflect upon three different points in time: before school closures, during school closures, and after return to school. More specifically, students were asked to reflect on the positive education taught by their school prior to COVID-19. They were asked to reflect on what actions they took during COVID-19 lockdown to thrive cognitively (positive reappraisal), emotionally (emotional processing), and behaviorally (strengths use). And upon return to school, students were asked to reflect upon what they had learned as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown (SRG).

Data Analysis

We carried out a two-step analytic approach to examine the association between positive education indicators and student levels of SRG upon returning back to campus during the COVID-19 outbreak. Observed scale characteristics were first performed to investigate descriptive statistics and the assumptions of analysis. Normality assumption was checked using kurtosis and skewness scores, with their cut points for the normality. Skewness <|2| and kurtosis scores <|7| suggest that the assumption of normality is met ( Curran et al., 1996 ; Kline, 2015 ). Pearson correlation was additionally used to examine the association between the variables of the study.

Following this, structural equation modeling was used to test the mediating effect of positive reappraisal, emotional processing, and strengths use during the period of remote learning in the association between positive education (i.e., the degree to which well-being skills were taught at school prior to the COVID-19 outbreak) and SRG upon returning back to campus. Common data-model fit statistics and squared multiple correlations ( R 2 ) were examined to evaluate the results of structural equation modeling. Tucker-Lewis index (TLI) and comparative fit index (CFI) scores between 0.90 and 0.95 indicate adequate model fit, whereas their scores ≥0.95 provide a good or close data-model fit. The root mean square error of approximation scores (RMSEA; with 90% confidence interval) and the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) between 0.05 and 0.08 are accepted as an adequate model fit, while those scores ≤0.05 indicate a close model fit ( Hu and Bentler, 1999 ; Hooper et al., 2008 ; Kline, 2015 ). The results were also interrelated using the squared multiple correlations ( R 2 ) with: <0.13 = small, 0.13–0.26 = moderate, and ≥0.26 = large ( Cohen, 1988 ). All data analyses were performed using AMOS version 24 and SPSS version 25.

Observed Scale Characteristics and Inter-correlations

A check of observed scale characteristics showed that all measures in the study were relatively normally distributed, and that kurtosis and skewness scores ranged between −0.80 and 0.47 (see Table 1 ). As shown in Table 1 , correlation analysis found that teaching positive education prior to COVID-19 had positive correlations with the way students coped during remote learning (positive reappraisal, emotional processing, and strengths use) and with SRG when returning to campus. Additionally, positive reappraisal, emotional processing, and strengths use were moderately to largely, positively associated with SRG.

Descriptive statistics and correlation results.

Mediation Analyses

Several structural equation models were employed to analyze the mediating effect of positive reappraisal, emotional processing, and strengths use in the relationship between positive education and SRG. The first model, which was conducted to test the mediating role of emotional processing indicated good data-model fit statistics ( χ 2 = 1.20, df = 1, p = 0.273, RMSEA = 0.069 [90% CI for RMSEA: 0.00–0.13], SRMR = 0.010, CFI = 99, and TLI = 0.99). Standardized regression estimates revealed that positive education was a significant predictor of emotional processing and SRG. Moreover, emotional processing significantly predicted youths’ SRG. The indirect effect of positive education on SRG through emotional processing was significant, as seen in Table 2 . Positive education accounted for 7% of the variance in emotional processing, and positive education and emotional processing together explained 41% of the variance in SRG. These findings demonstrate the partial mediating effect of emotional processing on the link between positive education and student SRG upon returning to campus during the COVID-19 outbreak.

Standardized indirect effects.

Number of bootstrap samples for percentile bootstrap confidence intervals: 10,000 with 95% bias-corrected confidence interval.

The second model, which was conducted to test the mediating effect of positive reappraisal, indicated excellent data-model fit statistics ( χ 2 = 0.76, df = 1, p = 0.382, RMSEA = 0.00 [90% CI for RMSEA: 0.000–0.12], SRMR = 0.010, CFI = 1.00, and TLI = 1.00). Positive education had a significant predictive effect on positive reappraisal and SRG. Positive reappraisal also significantly predicted youths’ SRG. The indirect effect of positive education on SRG through positive reappraisal was significant, as seen in Table 2 . Positive education accounted for 15% of the variance in positive reappraisal, and positive education and positive reappraisal together explained 50% of the variance in SRG. Consequently, the findings of this model indicated the partial mediating effect of positive reappraisal in the relationship between positive education and student SRG.

The third model, which was carried out to examine the mediating effect of strengths use, indicated excellent data-model fit statistics ( χ 2 = 0.24, df = 1, p = 0.626, RMSEA = 0.00 [90% CI for RMSEA: 0.000–0.10], SRMR = 0.010, CFI = 1.00, and TLI = 1.00). Positive education significantly predicted strengths use and SRG. Strengths use also had a significant predictive effect on student SRG. The indirect effect of positive education on SRG through strengths use was significant, as seen in Table 2 . Positive education accounted for 16% of the variance in positive reappraisal, and positive education and strengths use together explained 40% of the variance in the SRG of youths. These results indicate the partial mediating effect of strengths on the association between positive education and student SRG.

The final and main model tested the mediating effects of emotional processing, positive reappraisal (see Figure 1 ), and strengths use yielded data-model fit statistics ( χ 2 = 5.37, df = 3, p = 0.146, RMSEA = 0.044 [90% CI = 0.00–0.10], SRMR = 0.012, CFI = 99, and TLI = 0.99). Standardized estimates showed that positive education had significant and positive predictive effect on emotional processing, positive reappraisal, strengths use, and SRG. Furthermore, SRG was significantly predicted by emotional processing, positive reappraisal, and strengths use. In this model, all variables together explained 56% of the variance in the SRG (before including mediators = 21%). The indirect effect of positive education on SRG through the mediators was significant, as shown in Table 2 . Taken together, the findings of this model demonstrate the partial mediating effect of emotional processing, positive reappraisal, and strengths use in the relationship between positive education and the SRG of students.

Structural equation model indicating the relationship between the variables of the study. ** p < 0.001.

As the COVID-19 global health disaster continues to unfold across the world, researchers are rushing to quantify adolescent psychological distress ( Marques de Miranda et al., 2020 ). Such investigation is important because children and teenagers have been identified as a particularly vulnerable group within our society during the pandemic ( Guo et al., 2020 ). Research into teen distress is crucial but it need not come at the expense of learning about the positive outcomes that young people might experience in a pandemic. In this time of global crisis triggered by the COVID-19 pandemic, studies investigating how young people can come out stronger is vitally important given the findings from earlier pandemics that psychopathology and PTSD can last for up to 3 years post the pandemic ( Sprang and Silman, 2013 ).

The current study adopted a positive education approach, specifically a promotion-based orientation, to explore a range of factors that increase a student’s likelihood of experiencing SRG. Previous research has shown that young people can, and do, grow through adverse experiences ( Salter and Stallard, 2004 ). This same finding was shown in the current study where the mean score for cognitive/affective growth (e.g., “I learned not to let small hassles bother me the way they used to”) was 2.57 + 1.2 out of 5 and the mean score for social growth (e.g., “I have learned to appreciate the strength of others who have had a difficult life”) was 2.96 + 1.3. These scores are higher than other youth samples who have experienced minority stress (cognitive/affective growth 2.30 + 0.65/social growth 2.45 + 0.63; Vaughn et al., 2009 ) and those who reported on everyday stressors (cognitive/affective growth 2.10 + 0.60/social growth 2.15 + 0.63; Mansfield and Diamond, 2017 ).

In addition to demonstrating that teenagers can experience growth during the global pandemic, this study also sought to explore the degree to which a set of cognitive, emotional, and behavioral coping skills used during remote learning could predict SRG upon school re-entry. All three coping skills significantly predicted the degree to which students reported they had grown through COVID-19. Positive reappraisal had the strongest effect, followed by strengths use and then emotional processing.

Positive reappraisal is a meaning-based, cognitive strategy that allows an individual to “attach a positive meaning to the event in terms of personal growth” ( Garnefski and Kraaij, 2014 , p. 1154). This cognitive coping skill has been shown to be an adaptive way to help teenagers deal with a range of distressing situations, including being bullied ( Garnefski and Kraaij, 2014 ) and coping with loss, health threats, and relational stress ( Garnefski et al., 2003 ). Interestingly, Garnefski et al. (2002) found that adolescents did not use positive reappraisal as frequently as adults, suggesting that this is a skill that is worth teaching in the positive education curriculum in the future. To this end, Rood et al. (2012b , p. 83) explored whether positive reappraisal could be experimentally induced in teenagers and found that it could by asking them to think of stressful event in their lives and then “try to think about the positive side effects of the stressful event. Examine what you have learned, and how it has made you stronger.” Moreover, Rood et al. (2012b) found that of the four cognitive coping skills induced in teenagers (rumination, distancing, positive reappraisal, and acceptance), it was positive reappraisal that had the largest impact on well-being.

The degree to which students reported using their strengths during remote learning was also significantly, positively related to the amount of SRG they reported once back on campus. Strengths use has been positively associated with a host of well-being indicators for adolescents during mainstream times (i.e., non-crisis times) including life satisfaction ( Proctor et al., 2011 ), subjective well-being ( Jach et al., 2018 ), and hope ( Marques et al., 2011 ). In the context of adversity, strengths have also been shown to assist coping. For example, Shoshani and Slone (2016) found that strengths were inversely related to psychiatric symptoms and PTSD in teenagers experiencing war and political violence. In times of natural disaster, Southwick et al. (2016) argued that strengths help young people deal with the crisis adaptively and find solutions for the obstacles. In the COVID-19 pandemic, Bono et al. (2020) found that the strengths of grit and gratitude fostered resilience and impacted grades in university students. Our study found that strengths use was a significant predictor of the degree to which teenagers experienced SRG, suggesting that teaching students to identify and use their strengths will be beneficial in preparing them to grow through the current pandemic and in future times of adversity.

The third coping skill tested in this study was that of emotional processing, which is characterized by the conscious way a person acknowledges and handles intense emotions that come along with a distressing event or experience ( Stanton and Cameron, 2000 ). Park et al. (1996) found that seeking emotional support from others and venting one’s emotions were significantly related to SRG in university students. The intensity, uncertainty, and fear surrounding the global pandemic has triggered youth depression and anxiety ( Ellis et al., 2020 ) as well as heightened the experience of many, sub-clinical, negative emotions such as loneliness, frustration, anger, and hopelessness ( Garbe et al., 2020 ; Horita et al., 2021 ). With this in mind, it is easy to see why it is important for students to have the skills to adaptively work through their emotions each day. The degree to which students identified, validated, and expressed, their emotions was a significant predictor of SRG in the current study.