23 Advantages and Disadvantages of Qualitative Research

Investigating methodologies. Taking a closer look at ethnographic, anthropological, or naturalistic techniques. Data mining through observer recordings. This is what the world of qualitative research is all about. It is the comprehensive and complete data that is collected by having the courage to ask an open-ended question.

Print media has used the principles of qualitative research for generations. Now more industries are seeing the advantages that come from the extra data that is received by asking more than a “yes” or “no” question.

The advantages and disadvantages of qualitative research are quite unique. On one hand, you have the perspective of the data that is being collected. On the other hand, you have the techniques of the data collector and their own unique observations that can alter the information in subtle ways.

That’s why these key points are so important to consider.

What Are the Advantages of Qualitative Research?

1. Subject materials can be evaluated with greater detail. There are many time restrictions that are placed on research methods. The goal of a time restriction is to create a measurable outcome so that metrics can be in place. Qualitative research focuses less on the metrics of the data that is being collected and more on the subtleties of what can be found in that information. This allows for the data to have an enhanced level of detail to it, which can provide more opportunities to glean insights from it during examination.

2. Research frameworks can be fluid and based on incoming or available data. Many research opportunities must follow a specific pattern of questioning, data collection, and information reporting. Qualitative research offers a different approach. It can adapt to the quality of information that is being gathered. If the available data does not seem to be providing any results, the research can immediately shift gears and seek to gather data in a new direction. This offers more opportunities to gather important clues about any subject instead of being confined to a limited and often self-fulfilling perspective.

3. Qualitative research data is based on human experiences and observations. Humans have two very different operating systems. One is a subconscious method of operation, which is the fast and instinctual observations that are made when data is present. The other operating system is slower and more methodical, wanting to evaluate all sources of data before deciding. Many forms of research rely on the second operating system while ignoring the instinctual nature of the human mind. Qualitative research doesn’t ignore the gut instinct. It embraces it and the data that can be collected is often better for it.

4. Gathered data has a predictive quality to it. One of the common mistakes that occurs with qualitative research is an assumption that a personal perspective can be extrapolated into a group perspective. This is only possible when individuals grow up in similar circumstances, have similar perspectives about the world, and operate with similar goals. When these groups can be identified, however, the gathered individualistic data can have a predictive quality for those who are in a like-minded group. At the very least, the data has a predictive quality for the individual from whom it was gathered.

5. Qualitative research operates within structures that are fluid. Because the data being gathered through this type of research is based on observations and experiences, an experienced researcher can follow-up interesting answers with additional questions. Unlike other forms of research that require a specific framework with zero deviation, researchers can follow any data tangent which makes itself known and enhance the overall database of information that is being collected.

6. Data complexities can be incorporated into generated conclusions. Although our modern world tends to prefer statistics and verifiable facts, we cannot simply remove the human experience from the equation. Different people will have remarkably different perceptions about any statistic, fact, or event. This is because our unique experiences generate a different perspective of the data that we see. These complexities, when gathered into a singular database, can generate conclusions with more depth and accuracy, which benefits everyone.

7. Qualitative research is an open-ended process. When a researcher is properly prepared, the open-ended structures of qualitative research make it possible to get underneath superficial responses and rational thoughts to gather information from an individual’s emotional response. This is critically important to this form of researcher because it is an emotional response which often drives a person’s decisions or influences their behavior.

8. Creativity becomes a desirable quality within qualitative research. It can be difficult to analyze data that is obtained from individual sources because many people subconsciously answer in a way that they think someone wants. This desire to “please” another reduces the accuracy of the data and suppresses individual creativity. By embracing the qualitative research method, it becomes possible to encourage respondent creativity, allowing people to express themselves with authenticity. In return, the data collected becomes more accurate and can lead to predictable outcomes.

9. Qualitative research can create industry-specific insights. Brands and businesses today need to build relationships with their core demographics to survive. The terminology, vocabulary, and jargon that consumers use when looking at products or services is just as important as the reputation of the brand that is offering them. If consumers are receiving one context, but the intention of the brand is a different context, then the miscommunication can artificially restrict sales opportunities. Qualitative research gives brands access to these insights so they can accurately communicate their value propositions.

10. Smaller sample sizes are used in qualitative research, which can save on costs. Many qualitative research projects can be completed quickly and on a limited budget because they typically use smaller sample sizes that other research methods. This allows for faster results to be obtained so that projects can move forward with confidence that only good data is able to provide.

11. Qualitative research provides more content for creatives and marketing teams. When your job involves marketing, or creating new campaigns that target a specific demographic, then knowing what makes those people can be quite challenging. By going through the qualitative research approach, it becomes possible to congregate authentic ideas that can be used for marketing and other creative purposes. This makes communication between the two parties to be handled with more accuracy, leading to greater level of happiness for all parties involved.

12. Attitude explanations become possible with qualitative research. Consumer patterns can change on a dime sometimes, leaving a brand out in the cold as to what just happened. Qualitative research allows for a greater understanding of consumer attitudes, providing an explanation for events that occur outside of the predictive matrix that was developed through previous research. This allows the optimal brand/consumer relationship to be maintained.

What Are the Disadvantages of Qualitative Research?

1. The quality of the data gathered in qualitative research is highly subjective. This is where the personal nature of data gathering in qualitative research can also be a negative component of the process. What one researcher might feel is important and necessary to gather can be data that another researcher feels is pointless and won’t spend time pursuing it. Having individual perspectives and including instinctual decisions can lead to incredibly detailed data. It can also lead to data that is generalized or even inaccurate because of its reliance on researcher subjectivisms.

2. Data rigidity is more difficult to assess and demonstrate. Because individual perspectives are often the foundation of the data that is gathered in qualitative research, it is more difficult to prove that there is rigidity in the information that is collective. The human mind tends to remember things in the way it wants to remember them. That is why memories are often looked at fondly, even if the actual events that occurred may have been somewhat disturbing at the time. This innate desire to look at the good in things makes it difficult for researchers to demonstrate data validity.

3. Mining data gathered by qualitative research can be time consuming. The number of details that are often collected while performing qualitative research are often overwhelming. Sorting through that data to pull out the key points can be a time-consuming effort. It is also a subjective effort because what one researcher feels is important may not be pulled out by another researcher. Unless there are some standards in place that cannot be overridden, data mining through a massive number of details can almost be more trouble than it is worth in some instances.

4. Qualitative research creates findings that are valuable, but difficult to present. Presenting the findings which come out of qualitative research is a bit like listening to an interview on CNN. The interviewer will ask a question to the interviewee, but the goal is to receive an answer that will help present a database which presents a specific outcome to the viewer. The goal might be to have a viewer watch an interview and think, “That’s terrible. We need to pass a law to change that.” The subjective nature of the information, however, can cause the viewer to think, “That’s wonderful. Let’s keep things the way they are right now.” That is why findings from qualitative research are difficult to present. What a research gleans from the data can be very different from what an outside observer gleans from the data.

5. Data created through qualitative research is not always accepted. Because of the subjective nature of the data that is collected in qualitative research, findings are not always accepted by the scientific community. A second independent qualitative research effort which can produce similar findings is often necessary to begin the process of community acceptance.

6. Researcher influence can have a negative effect on the collected data. The quality of the data that is collected through qualitative research is highly dependent on the skills and observation of the researcher. If a researcher has a biased point of view, then their perspective will be included with the data collected and influence the outcome. There must be controls in place to help remove the potential for bias so the data collected can be reviewed with integrity. Otherwise, it would be possible for a researcher to make any claim and then use their bias through qualitative research to prove their point.

7. Replicating results can be very difficult with qualitative research. The scientific community wants to see results that can be verified and duplicated to accept research as factual. In the world of qualitative research, this can be very difficult to accomplish. Not only do you have the variability of researcher bias for which to account within the data, but there is also the informational bias that is built into the data itself from the provider. This means the scope of data gathering can be extremely limited, even if the structure of gathering information is fluid, because of each unique perspective.

8. Difficult decisions may require repetitive qualitative research periods. The smaller sample sizes of qualitative research may be an advantage, but they can also be a disadvantage for brands and businesses which are facing a difficult or potentially controversial decision. A small sample is not always representative of a larger population demographic, even if there are deep similarities with the individuals involve. This means a follow-up with a larger quantitative sample may be necessary so that data points can be tracked with more accuracy, allowing for a better overall decision to be made.

9. Unseen data can disappear during the qualitative research process. The amount of trust that is placed on the researcher to gather, and then draw together, the unseen data that is offered by a provider is enormous. The research is dependent upon the skill of the researcher being able to connect all the dots. If the researcher can do this, then the data can be meaningful and help brands and progress forward with their mission. If not, there is no way to alter course until after the first results are received. Then a new qualitative process must begin.

10. Researchers must have industry-related expertise. You can have an excellent researcher on-board for a project, but if they are not familiar with the subject matter, they will have a difficult time gathering accurate data. For qualitative research to be accurate, the interviewer involved must have specific skills, experiences, and expertise in the subject matter being studied. They must also be familiar with the material being evaluated and have the knowledge to interpret responses that are received. If any piece of this skill set is missing, the quality of the data being gathered can be open to interpretation.

11. Qualitative research is not statistically representative. The one disadvantage of qualitative research which is always present is its lack of statistical representation. It is a perspective-based method of research only, which means the responses given are not measured. Comparisons can be made and this can lead toward the duplication which may be required, but for the most part, quantitative data is required for circumstances which need statistical representation and that is not part of the qualitative research process.

The advantages and disadvantages of qualitative research make it possible to gather and analyze individualistic data on deeper levels. This makes it possible to gain new insights into consumer thoughts, demographic behavioral patterns, and emotional reasoning processes. When a research can connect the dots of each information point that is gathered, the information can lead to personalized experiences, better value in products and services, and ongoing brand development.

16 Key Advantages and Disadvantages of Qualitative Research Methods

Qualitative research is the process of natural inquisitiveness which wants to find an in-depth understanding of specific social phenomena within a regular setting. It is a process that seeks to find out why people act the way that they do in specific situations. By relying on the direct experiences that each person has every day, it becomes possible to define the meaning of a choice – or even a life.

Researchers who use the qualitative process are looking at multiple methods of inquiry to review human-related activities. This process is a way to measure the very existence of humanity. Multiple options are available to complete the work, including discourse analysis, biographies, case studies, and various other theories.

This process results in three primary areas of focus, which are individual actions, overall communication, and cultural influence. Each option must make the common assumption that knowledge is subjective instead of objective, which means the researchers must learn from their participants to understand what is valuable and what is not in their studies.

List of the Pros of Qualitative Research

1. Qualitative research is a very affordable method of research. Qualitative research is one of the most affordable ways to glean information from individuals who are being studied. Focus groups tend to be the primary method of collecting information using this process because it is fast and effective. Although there are research studies that require an extensive period of observation to produce results, using a group interview session can produce usable information in under an hour. That means you can proceed faster with the ideas you wish to pursue when compared to other research methods.

2. Qualitative research provides a predictive element. The data which researchers gather when using the qualitative research process provides a predictive element to the project. This advantage occurs even though the experiences or perspectives of the individuals participating in the research can vary substantially from person-to-person. The goal of this work is not to apply the information to the general public, but to understand how specific demographics react in situations where there are challenges to face. It is a process which allows for product development to occur because the pain points of the population have been identified.

3. Qualitative research focuses on the details of personal choice. The qualitative research process looks at the purpose of the decision that an individual makes as the primary information requiring collection. It does not take a look at the reasons why someone would decide to make the choices that they do in the first place. Other research methods preferred to look at the behavior, but this method wants to know the entire story behind each individual choice so that the entire population or society can benefit from the process.

4. Qualitative research uses fluid operational structures. The qualitative research process relies on data gathering based on situations that researchers are watching and experiencing personally. Instead of relying on a specific framework to collect and preserve information under rigid guidelines, this process finds value in the human experience. This method makes it possible to include the intricacies of the human experience with the structures required to find conclusions that are useful to the demographics involved – and possible to the rest of society as well.

5. Qualitative research uses individual choices as workable data. When we have an understanding of why individual choices occurred, then we can benefit from the diversity that the human experience provides. Each unique perspective makes it possible for every other person to gather more knowledge about a situation because there are differences to examine. It is a process which allows us to discover more potential outcomes because there is more information present from a variety of sources. Researchers can then take the perspectives to create guidelines that others can follow if they find themselves stuck in a similar situation.

6. Qualitative research is an open-ended process. One of the most significant advantages of qualitative research is that it does not rely on specific deadlines, formats, or questions to create a successful outcome. This process allows researchers to ask open-ended questions whenever they feel it is appropriate because there may be more data to collect. There are not the same time elements involved in this process either, as qualitative research can continue indefinitely until those working on the project feel like there is nothing more to glean from the individuals participating.

Because of this unique structure, researchers can look for data points that other methods might overlook because a greater emphasis is often placed on the interview or observational process with firm deadlines.

7. Qualitative research works to remove bias from its collected information. Unconscious bias is a significant factor in every research project because it relies on the ability of the individuals involved to control their thoughts, emotions, and reactions. Everyone has preconceived notions and stereotypes about specific demographics and nationalities which can influence the data collected. No one is 100% immune to this process. The format of qualitative research allows for these judgments to be set aside because it prefers to look at the specific structures behind each choice of person makes.

This research method also collects information about the events which lead up to a specific decision instead of trying to examine what happens after the fact. That’s why this advantage allows the data to be more accurate compared to the other research methods which are in use.

8. Qualitative research provides specific insight development. The average person tends to make a choice based on comfort, convenience, or both. We also tend to move forward in our circumstances based on what we feel is comfortable to our spiritual, moral, or ethical stances. Every form of communication that we use becomes a potential foundation for researchers to understand the demographics of humanity in better ways. By looking at the problems we face in everyday situations, it becomes possible to discover new insights that can help us to solve do you need problems which can come up. It is a way for researchers to understand the context of what happens in society instead of only looking at the outcomes.

9. Qualitative research requires a smaller sample size. Qualitative research studies wrap up faster that other methods because a smaller sample size is possible for data collection with this method. Participants can answer questions immediately, creating usable and actionable information that can lead to new ideas. This advantage makes it possible to move forward with confidence in future choices because there is added predictability to the results which are possible.

10. Qualitative research provides more useful content. Authenticity is highly demanded in today’s world because there is no better way to understand who we are as an individual, a community, or a society. Qualitative research works hard to understand the core concepts of how each participant defines themselves without the influence of outside perspectives. It wants to see how people structure their lives, and then take that data to help solve whatever problems they might have. Although no research method can provide guaranteed results, there is always some type of actionable information present with this approach.

List of the Cons of Qualitative Research

1. Qualitative research creates subjective information points. The quality of the information collected using the qualitative research process can sometimes be questionable. This approach requires the researchers to connect all of the data points which they gather to find the answers to their questions. That means the results are dependent upon the skills of those involved to read the non-verbal cues of each participate, understand when and where follow-up questions are necessary, and remember to document each response. Because individuals can interpret this data in many different ways, there can sometimes be differences in the conclusion because each researcher has a different take on what they receive.

2. Qualitative research can involve significant levels of repetition. Although the smaller sample sizes found in qualitative research can be an advantage, this structure can also be a problem when researchers are trying to collect a complete data profile for a specific demographic. Multiple interviews and discovery sessions become necessary to discover what the potential consequences of a future choice will be. When you only bring in a handful of people to discuss a situation, then these individuals may not offer a complete representation of the group being studied. Without multiple follow-up sessions with other participants, there is no way to prove the authenticity of the information collected.

3. Qualitative research is difficult to replicate. The only way that research can turn into fact is through a process of replication. Other researchers must be able to come to the similar conclusions after the initial project publishers the results. Because the nature of this work is subjective, finding opportunities to duplicate the results are quite rare. The scope of information which a project collects is often limited, which means there is always some doubt found in the data. That is why you will often see a margin of error percentage associated with research that uses this method. Because it never involves every potential member of a demographic, it will always be incomplete.

4. Qualitative research relies on the knowledge of the researchers. The only reason why opportunities are available in the first place when using qualitative research is because there are researchers involved which have expertise that relates to the subject matter being studied. When interviewers are unfamiliar with industry concepts, then it is much more challenging to identify follow-up opportunities that would be if the individual conducting the session was familiar with the ideas under discussion. There is no way to correctly interpret the data if the perspective of the researcher is skewed by a lack of knowledge.

5. Qualitative research does not offer statistics. The goal of qualitative research is to seek out moments of commonality. That means you will not find statistical data within the results. It looks to find specific areas of concern or pain points that are usable to the organization funding to research in the first place. The amount of data collected using this process can be extreme, but there is no guarantee that it will ever be usable. You do not have the same opportunities to compare information as you would with other research methods.

6. Qualitative research still requires a significant time investment. It is true that there are times when the qualitative research process is significantly faster than other methods. There is also the disadvantage in the fact that the amount of time necessary to collect accurate data can be unpredictable using this option. It may take months, years, or even decades to complete a research project if there is a massive amount of data to review. That means the researchers involve must make a long-term commitment to the process to ensure the results can be as accurate as possible.

These qualitative research pros and cons review how all of us come to the choices that we make each day. When researchers understand why we come to specific conclusions, then it becomes possible to create new goods and services that can make our lives easier. This process then concludes with solutions which can benefit a significant majority of the people, leading to better best practices in the future.

HARMONY PLATFORM .css-vxhqob{display:inline-block;line-height:1em;-webkit-flex-shrink:0;-ms-flex-negative:0;flex-shrink:0;color:currentColor;vertical-align:middle;fill:currentColor;stroke:none;margin-left:var(--chakra-space-4);height:var(--chakra-sizes-4);width:var(--chakra-sizes-2);margin-bottom:var(--chakra-space-1);}

Harmony platform.

Engage employees, inform customers and manage your workplace in one platform.

- Workplace Mobile App

HOW IT WORKS

- Omnichannel Feeds

- Integrations

- Analytics & Insights

- Workplace Management

- Consultancy

Find our how the Poppulo Harmony platform can help you to engage employees and customers, and deliver a great workplace experience.

- Employee Comms

- Customer Comms

- Workplace Experience

- Leadership Comms

- Change and Transformation

- Wayfinding & Directories

- Patient Comms

FEATURED CASE STUDIES

Using Digital Signage to Elevate the Workplace Experience

Aligning people and business goals through integrated employee communications

Valley Health

Launching an internal mobile app to keep frontline and back office employees informed

INDUSTRY OVERVIEW

Find out how our platform provides tailored support to your industry

- Hospitality & Entertainment

- Manufacturing

- Transportation

FEATURED CASE STUDY

Implementing an internal Mobile App in the software industry

OUR COMPANY

Our company overview.

- About Poppulo

RESOURCES OVERVIEW

We bring the best minds in employee comms together to share their knowledge and insights across our webinars, blogs, guides, and much more.

- Webinars & Guides

- Case Studies

- Maturity Model

FEATURED CONTENT

The Ultimate Guide to Internal Comms Strategy

The way we work, where we work, and how we work has fundamentally changed...

The Multi-Million Dollar Impact of Communication on Employee & Customer Experience

The stats speak for themselves—and the facts are unarguable...

10 Advantages and Disadvantages of Qualitative Research

— August 5th, 2021

Research is about gathering data so that it can inform meaningful decisions. In the workplace, this can be invaluable in allowing informed decision-making that will meet with wider strategic organizational goals.

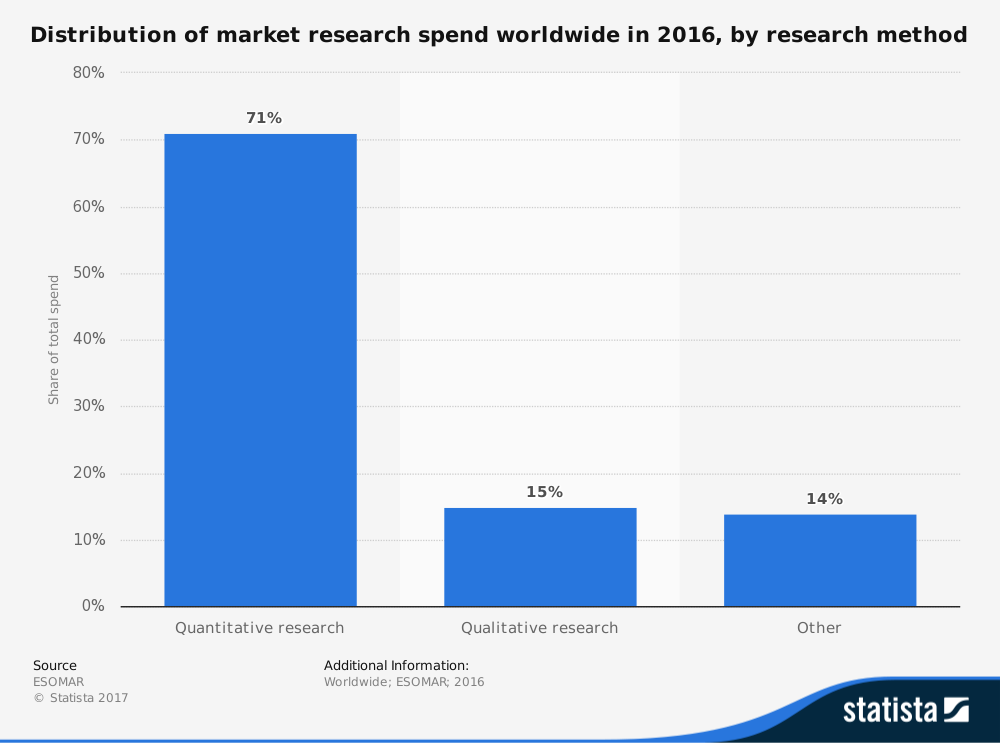

However, research comes in a variety of guises and, depending on the methodologies applied, can achieve different ends. There are broadly two key approaches to research -- qualitative and quantitative.

Focus Group Guide: Top Tips and Traps for Employee Focus Groups

Qualitative v quantitative – what’s the difference.

Qualitative Research is at the touchy-feely end of the spectrum. It’s not so much about bean-counting and much more about capturing people’s opinions and emotions.

“Research following a qualitative approach is exploratory and seeks to explain ‘how’ and ‘why’ a particular phenomenon, or behavior, operates as it does in a particular context.” (simplypsychology.org)

Examples of the way qualitative research is often gathered includes:

Interviews are a conversation based inquiry where questions are used to obtain information from participants. Interviews are typically structured to meet the researcher’s objectives.

Focus Groups

Focus group discussions are a common qualitative research strategy . In a focus group discussion, the interviewer talks to a group of people about their thoughts, opinions, beliefs, and attitudes towards a topic. Participants are typically a group who are similar in some way, such as income, education, or career. In the context of a company, the group dynamic is likely their common experience of the workplace.

Observation

Observation is a systematic research method in which researchers look at the activity of their subjects in their typical environment. Observation gives direct information about your research. Using observation can capture information that participants may not think to reveal or see as important during interviews/focus groups.

Existing Documents

This is also called secondary data. A qualitative data collection method entails extracting relevant data from existing documents. This data can then be analyzed using a qualitative data analysis method called content analysis. Existing documents might be work documents, work email , or any other material relevant to the organization.

Quantitative Research is the ‘bean-counting’ bit of the research spectrum. This isn’t to demean its value. Now encompassed by the term ‘ People Analytics ’, it plays an equally important role as a tool for business decision-making.

Organizations can use a variety of quantitative data-gathering methods to track productivity. In turn, this can help:

- To rank employees and work units

- To award raises or promotions.

- To measure and justify termination or disciplining of staff

- To measure productivity

- To measure group/individual targets

Examples might include measuring workforce productivity. If Widget Makers Inc., has two production lines and Line A is producing 25% more per day than Line B, capturing this data immediately informs management/HR of potential issues. Is the slower production on Line B due to human factors or is there a production process issue?

Quantitative Research can help capture real-time activities in the workplace and point towards what needs management attention.

The Pros & Cons of the Qualitative approach

By its nature, qualitative research is far more experiential and focused on capturing people’s feelings and views. This undoubtedly has value, but it can also bring many more challenges than simply capturing quantitative data. Here are a few challenges and benefits to consider.

- Qualitative Research can capture changing attitudes within a target group such as consumers of a product or service, or attitudes in the workplace.

- Qualitative approaches to research are not bound by the limitations of quantitative methods. If responses don’t fit the researcher’s expectation that’s equally useful qualitative data to add context and perhaps explain something that numbers alone are unable to reveal .

- Qualitative Research provides a much more flexible approach . If useful insights are not being captured researchers can quickly adapt questions, change the setting or any other variable to improve responses.

- Qualitative data capture allows researchers to be far more speculative about what areas they choose to investigate and how to do so. It allows data capture to be prompted by a researcher’s instinctive or ‘gut feel’ for where good information will be found.

Qualitative research can be more targeted . If you want to compare productivity across an entire organization, all parts, process, and participants need to be accounted for. Qualitative research can be far more concentrated, sampling specific groups and key points in a company to gather meaningful data. This can both speed the process of data capture and keep the costs of data-gathering down.

Business acumen in internal communications – Why it matters and how to build it

- Sample size can be a big issue. If you seek to infer from a sample of, for example, 200 employees, based upon a sample of 5 employees, this raises the question of whether sampling will provide a true reflection of the views of the remaining 97.5% of the company?

- Sample bias - HR departments will have competing agendas. One argument against qualitative methods alone is that HR tasked with finding the views of the workforce may be influenced both consciously or unconsciously, to select a sample that favors an anticipated outcome .

- Self-selection bias may arise where companies ask staff to volunteer their views . Whether in a paper, online survey , or focus group, if an HR department calls for participants there will be the issue of staff putting themselves forward. The argument goes that this group, in self-selecting itself, rather than being a randomly selected snapshot of a department, will inevitably have narrowed its relevance to those that typically are willing to come forward with their views. Quantitative data is gathered whether someone volunteered or not.

- The artificiality of qualitative data capture. The act of bringing together a group is inevitably outside of the typical ‘norms ’ of everyday work life and culture and may influence the participants in unforeseen ways.

- Are the right questions being posed to participants? You can only get answers to questions you think to ask . In qualitative approaches, asking about “how” and “why” can be hugely informative, but if researchers don’t ask, that insight may be missed.

The reality is that any research approach has both pros and cons. The art of effective and meaningful data gathering is thus to be aware of the limitations and strengths of each method.

In the case of Qualitative research, its value is inextricably linked to the number-crunching that is Quantitative data. One is the Ying to the other’s Yang. Each can only provide half of the picture, but together, you get a more complete view of what’s occurring within an organization.

The best on communications delivered weekly to your inbox.

UPCOMING WEBINAR – MAY 30TH

Proving it: leveraging analytics to showcase the value of internal comms.

- Privacy Policy

Home » Qualitative Research – Methods, Analysis Types and Guide

Qualitative Research – Methods, Analysis Types and Guide

Table of Contents

Qualitative Research

Qualitative research is a type of research methodology that focuses on exploring and understanding people’s beliefs, attitudes, behaviors, and experiences through the collection and analysis of non-numerical data. It seeks to answer research questions through the examination of subjective data, such as interviews, focus groups, observations, and textual analysis.

Qualitative research aims to uncover the meaning and significance of social phenomena, and it typically involves a more flexible and iterative approach to data collection and analysis compared to quantitative research. Qualitative research is often used in fields such as sociology, anthropology, psychology, and education.

Qualitative Research Methods

Qualitative Research Methods are as follows:

One-to-One Interview

This method involves conducting an interview with a single participant to gain a detailed understanding of their experiences, attitudes, and beliefs. One-to-one interviews can be conducted in-person, over the phone, or through video conferencing. The interviewer typically uses open-ended questions to encourage the participant to share their thoughts and feelings. One-to-one interviews are useful for gaining detailed insights into individual experiences.

Focus Groups

This method involves bringing together a group of people to discuss a specific topic in a structured setting. The focus group is led by a moderator who guides the discussion and encourages participants to share their thoughts and opinions. Focus groups are useful for generating ideas and insights, exploring social norms and attitudes, and understanding group dynamics.

Ethnographic Studies

This method involves immersing oneself in a culture or community to gain a deep understanding of its norms, beliefs, and practices. Ethnographic studies typically involve long-term fieldwork and observation, as well as interviews and document analysis. Ethnographic studies are useful for understanding the cultural context of social phenomena and for gaining a holistic understanding of complex social processes.

Text Analysis

This method involves analyzing written or spoken language to identify patterns and themes. Text analysis can be quantitative or qualitative. Qualitative text analysis involves close reading and interpretation of texts to identify recurring themes, concepts, and patterns. Text analysis is useful for understanding media messages, public discourse, and cultural trends.

This method involves an in-depth examination of a single person, group, or event to gain an understanding of complex phenomena. Case studies typically involve a combination of data collection methods, such as interviews, observations, and document analysis, to provide a comprehensive understanding of the case. Case studies are useful for exploring unique or rare cases, and for generating hypotheses for further research.

Process of Observation

This method involves systematically observing and recording behaviors and interactions in natural settings. The observer may take notes, use audio or video recordings, or use other methods to document what they see. Process of observation is useful for understanding social interactions, cultural practices, and the context in which behaviors occur.

Record Keeping

This method involves keeping detailed records of observations, interviews, and other data collected during the research process. Record keeping is essential for ensuring the accuracy and reliability of the data, and for providing a basis for analysis and interpretation.

This method involves collecting data from a large sample of participants through a structured questionnaire. Surveys can be conducted in person, over the phone, through mail, or online. Surveys are useful for collecting data on attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors, and for identifying patterns and trends in a population.

Qualitative data analysis is a process of turning unstructured data into meaningful insights. It involves extracting and organizing information from sources like interviews, focus groups, and surveys. The goal is to understand people’s attitudes, behaviors, and motivations

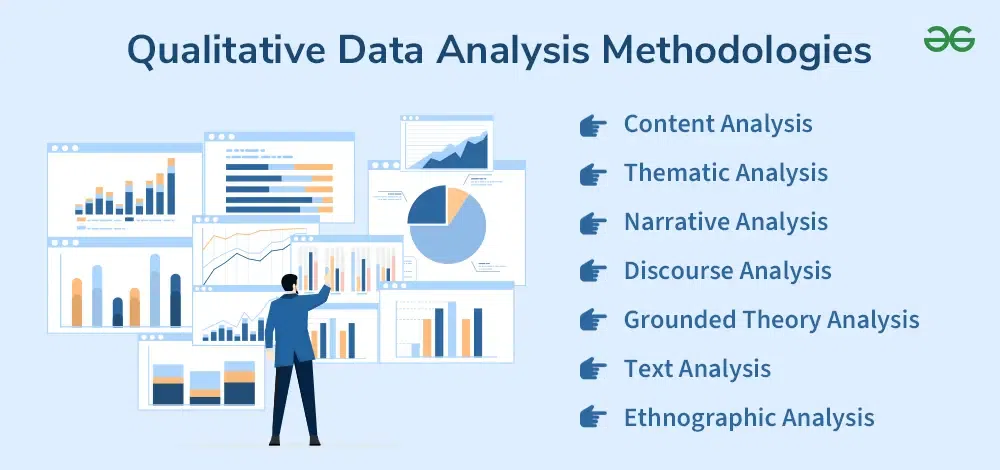

Qualitative Research Analysis Methods

Qualitative Research analysis methods involve a systematic approach to interpreting and making sense of the data collected in qualitative research. Here are some common qualitative data analysis methods:

Thematic Analysis

This method involves identifying patterns or themes in the data that are relevant to the research question. The researcher reviews the data, identifies keywords or phrases, and groups them into categories or themes. Thematic analysis is useful for identifying patterns across multiple data sources and for generating new insights into the research topic.

Content Analysis

This method involves analyzing the content of written or spoken language to identify key themes or concepts. Content analysis can be quantitative or qualitative. Qualitative content analysis involves close reading and interpretation of texts to identify recurring themes, concepts, and patterns. Content analysis is useful for identifying patterns in media messages, public discourse, and cultural trends.

Discourse Analysis

This method involves analyzing language to understand how it constructs meaning and shapes social interactions. Discourse analysis can involve a variety of methods, such as conversation analysis, critical discourse analysis, and narrative analysis. Discourse analysis is useful for understanding how language shapes social interactions, cultural norms, and power relationships.

Grounded Theory Analysis

This method involves developing a theory or explanation based on the data collected. Grounded theory analysis starts with the data and uses an iterative process of coding and analysis to identify patterns and themes in the data. The theory or explanation that emerges is grounded in the data, rather than preconceived hypotheses. Grounded theory analysis is useful for understanding complex social phenomena and for generating new theoretical insights.

Narrative Analysis

This method involves analyzing the stories or narratives that participants share to gain insights into their experiences, attitudes, and beliefs. Narrative analysis can involve a variety of methods, such as structural analysis, thematic analysis, and discourse analysis. Narrative analysis is useful for understanding how individuals construct their identities, make sense of their experiences, and communicate their values and beliefs.

Phenomenological Analysis

This method involves analyzing how individuals make sense of their experiences and the meanings they attach to them. Phenomenological analysis typically involves in-depth interviews with participants to explore their experiences in detail. Phenomenological analysis is useful for understanding subjective experiences and for developing a rich understanding of human consciousness.

Comparative Analysis

This method involves comparing and contrasting data across different cases or groups to identify similarities and differences. Comparative analysis can be used to identify patterns or themes that are common across multiple cases, as well as to identify unique or distinctive features of individual cases. Comparative analysis is useful for understanding how social phenomena vary across different contexts and groups.

Applications of Qualitative Research

Qualitative research has many applications across different fields and industries. Here are some examples of how qualitative research is used:

- Market Research: Qualitative research is often used in market research to understand consumer attitudes, behaviors, and preferences. Researchers conduct focus groups and one-on-one interviews with consumers to gather insights into their experiences and perceptions of products and services.

- Health Care: Qualitative research is used in health care to explore patient experiences and perspectives on health and illness. Researchers conduct in-depth interviews with patients and their families to gather information on their experiences with different health care providers and treatments.

- Education: Qualitative research is used in education to understand student experiences and to develop effective teaching strategies. Researchers conduct classroom observations and interviews with students and teachers to gather insights into classroom dynamics and instructional practices.

- Social Work : Qualitative research is used in social work to explore social problems and to develop interventions to address them. Researchers conduct in-depth interviews with individuals and families to understand their experiences with poverty, discrimination, and other social problems.

- Anthropology : Qualitative research is used in anthropology to understand different cultures and societies. Researchers conduct ethnographic studies and observe and interview members of different cultural groups to gain insights into their beliefs, practices, and social structures.

- Psychology : Qualitative research is used in psychology to understand human behavior and mental processes. Researchers conduct in-depth interviews with individuals to explore their thoughts, feelings, and experiences.

- Public Policy : Qualitative research is used in public policy to explore public attitudes and to inform policy decisions. Researchers conduct focus groups and one-on-one interviews with members of the public to gather insights into their perspectives on different policy issues.

How to Conduct Qualitative Research

Here are some general steps for conducting qualitative research:

- Identify your research question: Qualitative research starts with a research question or set of questions that you want to explore. This question should be focused and specific, but also broad enough to allow for exploration and discovery.

- Select your research design: There are different types of qualitative research designs, including ethnography, case study, grounded theory, and phenomenology. You should select a design that aligns with your research question and that will allow you to gather the data you need to answer your research question.

- Recruit participants: Once you have your research question and design, you need to recruit participants. The number of participants you need will depend on your research design and the scope of your research. You can recruit participants through advertisements, social media, or through personal networks.

- Collect data: There are different methods for collecting qualitative data, including interviews, focus groups, observation, and document analysis. You should select the method or methods that align with your research design and that will allow you to gather the data you need to answer your research question.

- Analyze data: Once you have collected your data, you need to analyze it. This involves reviewing your data, identifying patterns and themes, and developing codes to organize your data. You can use different software programs to help you analyze your data, or you can do it manually.

- Interpret data: Once you have analyzed your data, you need to interpret it. This involves making sense of the patterns and themes you have identified, and developing insights and conclusions that answer your research question. You should be guided by your research question and use your data to support your conclusions.

- Communicate results: Once you have interpreted your data, you need to communicate your results. This can be done through academic papers, presentations, or reports. You should be clear and concise in your communication, and use examples and quotes from your data to support your findings.

Examples of Qualitative Research

Here are some real-time examples of qualitative research:

- Customer Feedback: A company may conduct qualitative research to understand the feedback and experiences of its customers. This may involve conducting focus groups or one-on-one interviews with customers to gather insights into their attitudes, behaviors, and preferences.

- Healthcare : A healthcare provider may conduct qualitative research to explore patient experiences and perspectives on health and illness. This may involve conducting in-depth interviews with patients and their families to gather information on their experiences with different health care providers and treatments.

- Education : An educational institution may conduct qualitative research to understand student experiences and to develop effective teaching strategies. This may involve conducting classroom observations and interviews with students and teachers to gather insights into classroom dynamics and instructional practices.

- Social Work: A social worker may conduct qualitative research to explore social problems and to develop interventions to address them. This may involve conducting in-depth interviews with individuals and families to understand their experiences with poverty, discrimination, and other social problems.

- Anthropology : An anthropologist may conduct qualitative research to understand different cultures and societies. This may involve conducting ethnographic studies and observing and interviewing members of different cultural groups to gain insights into their beliefs, practices, and social structures.

- Psychology : A psychologist may conduct qualitative research to understand human behavior and mental processes. This may involve conducting in-depth interviews with individuals to explore their thoughts, feelings, and experiences.

- Public Policy: A government agency or non-profit organization may conduct qualitative research to explore public attitudes and to inform policy decisions. This may involve conducting focus groups and one-on-one interviews with members of the public to gather insights into their perspectives on different policy issues.

Purpose of Qualitative Research

The purpose of qualitative research is to explore and understand the subjective experiences, behaviors, and perspectives of individuals or groups in a particular context. Unlike quantitative research, which focuses on numerical data and statistical analysis, qualitative research aims to provide in-depth, descriptive information that can help researchers develop insights and theories about complex social phenomena.

Qualitative research can serve multiple purposes, including:

- Exploring new or emerging phenomena : Qualitative research can be useful for exploring new or emerging phenomena, such as new technologies or social trends. This type of research can help researchers develop a deeper understanding of these phenomena and identify potential areas for further study.

- Understanding complex social phenomena : Qualitative research can be useful for exploring complex social phenomena, such as cultural beliefs, social norms, or political processes. This type of research can help researchers develop a more nuanced understanding of these phenomena and identify factors that may influence them.

- Generating new theories or hypotheses: Qualitative research can be useful for generating new theories or hypotheses about social phenomena. By gathering rich, detailed data about individuals’ experiences and perspectives, researchers can develop insights that may challenge existing theories or lead to new lines of inquiry.

- Providing context for quantitative data: Qualitative research can be useful for providing context for quantitative data. By gathering qualitative data alongside quantitative data, researchers can develop a more complete understanding of complex social phenomena and identify potential explanations for quantitative findings.

When to use Qualitative Research

Here are some situations where qualitative research may be appropriate:

- Exploring a new area: If little is known about a particular topic, qualitative research can help to identify key issues, generate hypotheses, and develop new theories.

- Understanding complex phenomena: Qualitative research can be used to investigate complex social, cultural, or organizational phenomena that are difficult to measure quantitatively.

- Investigating subjective experiences: Qualitative research is particularly useful for investigating the subjective experiences of individuals or groups, such as their attitudes, beliefs, values, or emotions.

- Conducting formative research: Qualitative research can be used in the early stages of a research project to develop research questions, identify potential research participants, and refine research methods.

- Evaluating interventions or programs: Qualitative research can be used to evaluate the effectiveness of interventions or programs by collecting data on participants’ experiences, attitudes, and behaviors.

Characteristics of Qualitative Research

Qualitative research is characterized by several key features, including:

- Focus on subjective experience: Qualitative research is concerned with understanding the subjective experiences, beliefs, and perspectives of individuals or groups in a particular context. Researchers aim to explore the meanings that people attach to their experiences and to understand the social and cultural factors that shape these meanings.

- Use of open-ended questions: Qualitative research relies on open-ended questions that allow participants to provide detailed, in-depth responses. Researchers seek to elicit rich, descriptive data that can provide insights into participants’ experiences and perspectives.

- Sampling-based on purpose and diversity: Qualitative research often involves purposive sampling, in which participants are selected based on specific criteria related to the research question. Researchers may also seek to include participants with diverse experiences and perspectives to capture a range of viewpoints.

- Data collection through multiple methods: Qualitative research typically involves the use of multiple data collection methods, such as in-depth interviews, focus groups, and observation. This allows researchers to gather rich, detailed data from multiple sources, which can provide a more complete picture of participants’ experiences and perspectives.

- Inductive data analysis: Qualitative research relies on inductive data analysis, in which researchers develop theories and insights based on the data rather than testing pre-existing hypotheses. Researchers use coding and thematic analysis to identify patterns and themes in the data and to develop theories and explanations based on these patterns.

- Emphasis on researcher reflexivity: Qualitative research recognizes the importance of the researcher’s role in shaping the research process and outcomes. Researchers are encouraged to reflect on their own biases and assumptions and to be transparent about their role in the research process.

Advantages of Qualitative Research

Qualitative research offers several advantages over other research methods, including:

- Depth and detail: Qualitative research allows researchers to gather rich, detailed data that provides a deeper understanding of complex social phenomena. Through in-depth interviews, focus groups, and observation, researchers can gather detailed information about participants’ experiences and perspectives that may be missed by other research methods.

- Flexibility : Qualitative research is a flexible approach that allows researchers to adapt their methods to the research question and context. Researchers can adjust their research methods in real-time to gather more information or explore unexpected findings.

- Contextual understanding: Qualitative research is well-suited to exploring the social and cultural context in which individuals or groups are situated. Researchers can gather information about cultural norms, social structures, and historical events that may influence participants’ experiences and perspectives.

- Participant perspective : Qualitative research prioritizes the perspective of participants, allowing researchers to explore subjective experiences and understand the meanings that participants attach to their experiences.

- Theory development: Qualitative research can contribute to the development of new theories and insights about complex social phenomena. By gathering rich, detailed data and using inductive data analysis, researchers can develop new theories and explanations that may challenge existing understandings.

- Validity : Qualitative research can offer high validity by using multiple data collection methods, purposive and diverse sampling, and researcher reflexivity. This can help ensure that findings are credible and trustworthy.

Limitations of Qualitative Research

Qualitative research also has some limitations, including:

- Subjectivity : Qualitative research relies on the subjective interpretation of researchers, which can introduce bias into the research process. The researcher’s perspective, beliefs, and experiences can influence the way data is collected, analyzed, and interpreted.

- Limited generalizability: Qualitative research typically involves small, purposive samples that may not be representative of larger populations. This limits the generalizability of findings to other contexts or populations.

- Time-consuming: Qualitative research can be a time-consuming process, requiring significant resources for data collection, analysis, and interpretation.

- Resource-intensive: Qualitative research may require more resources than other research methods, including specialized training for researchers, specialized software for data analysis, and transcription services.

- Limited reliability: Qualitative research may be less reliable than quantitative research, as it relies on the subjective interpretation of researchers. This can make it difficult to replicate findings or compare results across different studies.

- Ethics and confidentiality: Qualitative research involves collecting sensitive information from participants, which raises ethical concerns about confidentiality and informed consent. Researchers must take care to protect the privacy and confidentiality of participants and obtain informed consent.

Also see Research Methods

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Questionnaire – Definition, Types, and Examples

Case Study – Methods, Examples and Guide

Observational Research – Methods and Guide

Quantitative Research – Methods, Types and...

Qualitative Research Methods

Explanatory Research – Types, Methods, Guide

19 Advantages and Disadvantages of Qualitative Research

Qualitative research is a method that involves collecting and analyzing non-numerical data to understand social phenomena.

This approach allows researchers to explore and gain in-depth insights into complex issues that cannot be easily measured or quantified.

However, like any research method, there are both advantages and disadvantages associated with qualitative research.

- Redaction Team

- September 9, 2023

- Professional Development , Thesis Writing

Advantages of Qualitative Research

- Rich and In-Depth Data : Qualitative research provides rich and detailed data, allowing researchers to explore complex social phenomena, experiences, and contexts in depth.

- Contextual Understanding : It emphasizes the importance of context, enabling researchers to understand the social, cultural, and environmental factors that influence behavior and perceptions.

- Flexibility : Qualitative research is flexible and adaptable, allowing researchers to change their research focus, questions, or methods based on emerging insights during the study.

- Exploratory Nature : It is well-suited for generating hypotheses and theories by exploring new or under-researched topics. Researchers can uncover unexpected findings.

- Participant Perspectives : Qualitative research prioritizes the voices and perspectives of participants, providing insight into their lived experiences, beliefs, and worldviews.

- Holistic Understanding : Researchers can capture the complexity of human behavior and experiences, including emotions, motivations, and interpersonal dynamics.

- Useful for Small Sample Sizes : Qualitative research can be effective with small sample sizes when a deep understanding of a specific group or context is required.

- Complementary to Quantitative Research : It can complement quantitative research by providing qualitative insights that help explain or interpret numerical data.

- Validity and Authenticity : Qualitative research often focuses on establishing the validity and authenticity of findings, emphasizing the importance of rigor and transparency in the research process.

Disadvantages of Qualitative Research

- Subjectivity : Qualitative research is subjective in nature, and findings can be influenced by the researcher's biases, interpretations, and values.

- Limited Generalizability : The small sample sizes and context-specific nature of qualitative research may limit the generalizability of findings to broader populations or contexts.

- Time-Consuming : Qualitative research can be time-consuming, as it involves data collection methods such as interviews, participant observation, and content analysis, which require significant time and effort.

- Data Analysis Complexity : Analyzing qualitative data can be complex, requiring skills in coding, thematic analysis, and interpretation. It can be challenging to ensure intercoder reliability.

- Resource-Intensive : Qualitative research may require more resources than quantitative research, particularly when conducting in-depth interviews or ethnographic fieldwork.

- Ethical Considerations : Researchers must navigate ethical considerations, such as informed consent, confidentiality, and ensuring the well-being of participants, which can be complex in qualitative studies.

- Interpretation Challenges : Qualitative research findings are open to interpretation, and different researchers may draw different conclusions from the same data.

- Limited Quantification : Qualitative research does not produce numerical data, which can make it challenging to quantify and compare findings across studies.

- Potential for Researcher Influence : Researchers may inadvertently influence participant responses or behaviors through their presence or questioning, leading to potential bias.

- Difficulty in Sampling : Choosing a representative sample can be challenging in qualitative research, as the emphasis is on depth rather than breadth.

In practice, the choice between qualitative and quantitative research methods depends on the research objectives, questions, and the nature of the phenomenon being studied.

Often, researchers use mixed methods, combining both qualitative and quantitative approaches, to gain a more comprehensive understanding of a research topic.

Conclusion of Pros and Cons of Qualitative Research Method

In conclusion, qualitative research offers several advantages, such as capturing rich, detailed data, providing flexibility in data collection methods, and allowing for exploratory studiesfrom market research, focus group, interviews with follow-up questions and open-ended questions by the interviewer.

However, it also has limitations, including small sample sizes, subjective data analysis, resource-intensiveness, and challenges in establishing validity and reliability, as in contrast from quantitative methods with quantitative data.

Therefore, researchers should consider both the strengths and weaknesses of qualitative research and advantages and disadvantages of quantitative research approach when selecting the appropriate type of research methodology for their study.

By understanding these advantages and disadvantages, researchers can make informed decisions and maximize the potential of qualitative research in generating meaningful insights.

Read more here on how to write a Master Thesis .

Privacy Overview

Qualitative Study

Affiliations.

- 1 University of Nebraska Medical Center

- 2 GDB Research and Statistical Consulting

- 3 GDB Research and Statistical Consulting/McLaren Macomb Hospital

- PMID: 29262162

- Bookshelf ID: NBK470395

Qualitative research is a type of research that explores and provides deeper insights into real-world problems. Instead of collecting numerical data points or intervening or introducing treatments just like in quantitative research, qualitative research helps generate hypothenar to further investigate and understand quantitative data. Qualitative research gathers participants' experiences, perceptions, and behavior. It answers the hows and whys instead of how many or how much. It could be structured as a standalone study, purely relying on qualitative data, or part of mixed-methods research that combines qualitative and quantitative data. This review introduces the readers to some basic concepts, definitions, terminology, and applications of qualitative research.

Qualitative research, at its core, asks open-ended questions whose answers are not easily put into numbers, such as "how" and "why." Due to the open-ended nature of the research questions, qualitative research design is often not linear like quantitative design. One of the strengths of qualitative research is its ability to explain processes and patterns of human behavior that can be difficult to quantify. Phenomena such as experiences, attitudes, and behaviors can be complex to capture accurately and quantitatively. In contrast, a qualitative approach allows participants themselves to explain how, why, or what they were thinking, feeling, and experiencing at a particular time or during an event of interest. Quantifying qualitative data certainly is possible, but at its core, qualitative data is looking for themes and patterns that can be difficult to quantify, and it is essential to ensure that the context and narrative of qualitative work are not lost by trying to quantify something that is not meant to be quantified.

However, while qualitative research is sometimes placed in opposition to quantitative research, where they are necessarily opposites and therefore "compete" against each other and the philosophical paradigms associated with each other, qualitative and quantitative work are neither necessarily opposites, nor are they incompatible. While qualitative and quantitative approaches are different, they are not necessarily opposites and certainly not mutually exclusive. For instance, qualitative research can help expand and deepen understanding of data or results obtained from quantitative analysis. For example, say a quantitative analysis has determined a correlation between length of stay and level of patient satisfaction, but why does this correlation exist? This dual-focus scenario shows one way in which qualitative and quantitative research could be integrated.

Copyright © 2024, StatPearls Publishing LLC.

- Introduction

- Issues of Concern

- Clinical Significance

- Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

- Review Questions

Publication types

- Study Guide

- Interesting

- Scholarships

- UGC-CARE Journals

Advantages and Disadvantages of Qualitative Research Methodologies

Unlock the benefits and drawbacks of qualitative research methodologies.

Qualitative research methodologies offer in-depth understanding and context, fostering rich insights into complex phenomena. However, they may lack generalizability and could be subject to researcher bias, requiring careful interpretation and analysis.

Qualitative research method offers unique advantages and disadvantages that researchers should consider when choosing their approach:

Unlock the benefits and drawbacks of the qualitative research method. Delve into nuanced insights and potential biases, guiding your approach to in-depth understanding and critical analysis in academic exploration.

Advantages of Qualitative Research Methodologies

Qualitative research allows participants to express their thoughts and views freely, leading to authentic responses

1 . Trustworthiness

Information gathered in qualitative studies is based on participants’ thoughts and experiences, making it more trustworthy and accurate

2 . In-depth Questioning

Qualitative methods like focus groups and interviews enable researchers to research deeply into topics, providing rich insights

3. Flexibility

Qualitative research offers a flexible approach, allowing researchers to adapt questions or settings quickly to improve responses

4. Creativity

This methodology encourages creativity and genuine ideas to be collected from specific demographics, fostering innovation

Disadvantages of Qualitative Research Methodologies

Qualitative research does not provide statistical representation, limiting the ability to make quantitative comparisons

1 . Data Duplication

Responses in qualitative research cannot usually be measured, leading to potential data duplication over time

2 . Time-Consuming

Qualitative research can be time-consuming and labor-intensive due to the detailed nature of data collection and analysis

3. Difficulty in Replicating Results

Due to the subjective nature of qualitative data, replicating results can be challenging, impacting the reliability of findings

4. Dependence on Researchers’ Experience:

The quality of data collected in qualitative research relies heavily on the experience and skills of the researchers involved

In conclusion, while qualitative research methodologies offer valuable insights into human behavior and social interactions, researchers must carefully weigh these advantages and disadvantages to ensure the effectiveness and reliability of their studies

Also Read: Quantitative Vs Qualitative Research

- advantages of qualitative research

- contextual understanding

- Critical Analysis

- data interpretation

- disadvantages of qualitative research

- pros and cons

- Qualitative Insights

- Research Bias

- Research Methodology

- research validity

Effective Tips on How to Read Research Paper

Six effective tips to identify research gap, 24 best free plagiarism checkers in 2024, most popular, 100 connective words for research paper writing, phd supervisors – unsung heroes of doctoral students, india-canada collaborative industrial r&d grant, call for mobility plus project proposal – india and the czech republic, iitm & birmingham – joint master program, anna’s archive – download research papers for free, fulbright-kalam climate fellowship: fostering us-india collaboration, fulbright specialist program 2024-25, best for you, what is phd, popular posts, how to check scopus indexed journals 2024, how to write a research paper a complete guide, 480 ugc-care list of journals – science – 2024, popular category.

- POSTDOC 317

- Interesting 258

- Journals 234

- Fellowship 128

- Research Methodology 102

- All Scopus Indexed Journals 92

iLovePhD is a research education website to know updated research-related information. It helps researchers to find top journals for publishing research articles and get an easy manual for research tools. The main aim of this website is to help Ph.D. scholars who are working in various domains to get more valuable ideas to carry out their research. Learn the current groundbreaking research activities around the world, love the process of getting a Ph.D.

Contact us: [email protected]

Google News

Copyright © 2024 iLovePhD. All rights reserved

- Artificial intelligence

Qualitative vs Quantitative Research Methods & Data Analysis

Saul Mcleod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul Mcleod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

On This Page:

What is the difference between quantitative and qualitative?

The main difference between quantitative and qualitative research is the type of data they collect and analyze.

Quantitative research collects numerical data and analyzes it using statistical methods. The aim is to produce objective, empirical data that can be measured and expressed in numerical terms. Quantitative research is often used to test hypotheses, identify patterns, and make predictions.

Qualitative research , on the other hand, collects non-numerical data such as words, images, and sounds. The focus is on exploring subjective experiences, opinions, and attitudes, often through observation and interviews.

Qualitative research aims to produce rich and detailed descriptions of the phenomenon being studied, and to uncover new insights and meanings.

Quantitative data is information about quantities, and therefore numbers, and qualitative data is descriptive, and regards phenomenon which can be observed but not measured, such as language.

What Is Qualitative Research?

Qualitative research is the process of collecting, analyzing, and interpreting non-numerical data, such as language. Qualitative research can be used to understand how an individual subjectively perceives and gives meaning to their social reality.

Qualitative data is non-numerical data, such as text, video, photographs, or audio recordings. This type of data can be collected using diary accounts or in-depth interviews and analyzed using grounded theory or thematic analysis.

Qualitative research is multimethod in focus, involving an interpretive, naturalistic approach to its subject matter. This means that qualitative researchers study things in their natural settings, attempting to make sense of, or interpret, phenomena in terms of the meanings people bring to them. Denzin and Lincoln (1994, p. 2)

Interest in qualitative data came about as the result of the dissatisfaction of some psychologists (e.g., Carl Rogers) with the scientific study of psychologists such as behaviorists (e.g., Skinner ).

Since psychologists study people, the traditional approach to science is not seen as an appropriate way of carrying out research since it fails to capture the totality of human experience and the essence of being human. Exploring participants’ experiences is known as a phenomenological approach (re: Humanism ).

Qualitative research is primarily concerned with meaning, subjectivity, and lived experience. The goal is to understand the quality and texture of people’s experiences, how they make sense of them, and the implications for their lives.

Qualitative research aims to understand the social reality of individuals, groups, and cultures as nearly as possible as participants feel or live it. Thus, people and groups are studied in their natural setting.

Some examples of qualitative research questions are provided, such as what an experience feels like, how people talk about something, how they make sense of an experience, and how events unfold for people.

Research following a qualitative approach is exploratory and seeks to explain ‘how’ and ‘why’ a particular phenomenon, or behavior, operates as it does in a particular context. It can be used to generate hypotheses and theories from the data.

Qualitative Methods

There are different types of qualitative research methods, including diary accounts, in-depth interviews , documents, focus groups , case study research , and ethnography.

The results of qualitative methods provide a deep understanding of how people perceive their social realities and in consequence, how they act within the social world.

The researcher has several methods for collecting empirical materials, ranging from the interview to direct observation, to the analysis of artifacts, documents, and cultural records, to the use of visual materials or personal experience. Denzin and Lincoln (1994, p. 14)

Here are some examples of qualitative data:

Interview transcripts : Verbatim records of what participants said during an interview or focus group. They allow researchers to identify common themes and patterns, and draw conclusions based on the data. Interview transcripts can also be useful in providing direct quotes and examples to support research findings.

Observations : The researcher typically takes detailed notes on what they observe, including any contextual information, nonverbal cues, or other relevant details. The resulting observational data can be analyzed to gain insights into social phenomena, such as human behavior, social interactions, and cultural practices.

Unstructured interviews : generate qualitative data through the use of open questions. This allows the respondent to talk in some depth, choosing their own words. This helps the researcher develop a real sense of a person’s understanding of a situation.

Diaries or journals : Written accounts of personal experiences or reflections.

Notice that qualitative data could be much more than just words or text. Photographs, videos, sound recordings, and so on, can be considered qualitative data. Visual data can be used to understand behaviors, environments, and social interactions.

Qualitative Data Analysis

Qualitative research is endlessly creative and interpretive. The researcher does not just leave the field with mountains of empirical data and then easily write up his or her findings.

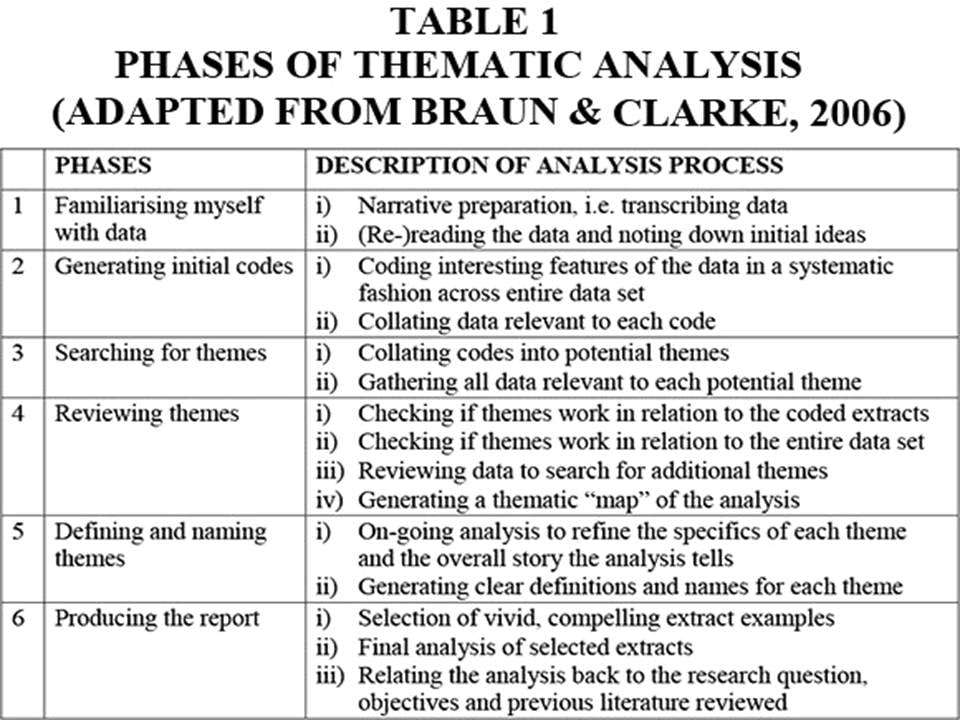

Qualitative interpretations are constructed, and various techniques can be used to make sense of the data, such as content analysis, grounded theory (Glaser & Strauss, 1967), thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006), or discourse analysis.

For example, thematic analysis is a qualitative approach that involves identifying implicit or explicit ideas within the data. Themes will often emerge once the data has been coded.

Key Features