Select Your Interests

Customize your JAMA Network experience by selecting one or more topics from the list below.

- Academic Medicine

- Acid Base, Electrolytes, Fluids

- Allergy and Clinical Immunology

- American Indian or Alaska Natives

- Anesthesiology

- Anticoagulation

- Art and Images in Psychiatry

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assisted Reproduction

- Bleeding and Transfusion

- Caring for the Critically Ill Patient

- Challenges in Clinical Electrocardiography

- Climate and Health

- Climate Change

- Clinical Challenge

- Clinical Decision Support

- Clinical Implications of Basic Neuroscience

- Clinical Pharmacy and Pharmacology

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Consensus Statements

- Coronavirus (COVID-19)

- Critical Care Medicine

- Cultural Competency

- Dental Medicine

- Dermatology

- Diabetes and Endocrinology

- Diagnostic Test Interpretation

- Drug Development

- Electronic Health Records

- Emergency Medicine

- End of Life, Hospice, Palliative Care

- Environmental Health

- Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion

- Facial Plastic Surgery

- Gastroenterology and Hepatology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Genomics and Precision Health

- Global Health

- Guide to Statistics and Methods

- Hair Disorders

- Health Care Delivery Models

- Health Care Economics, Insurance, Payment

- Health Care Quality

- Health Care Reform

- Health Care Safety

- Health Care Workforce

- Health Disparities

- Health Inequities

- Health Policy

- Health Systems Science

- History of Medicine

- Hypertension

- Images in Neurology

- Implementation Science

- Infectious Diseases

- Innovations in Health Care Delivery

- JAMA Infographic

- Law and Medicine

- Leading Change

- Less is More

- LGBTQIA Medicine

- Lifestyle Behaviors

- Medical Coding

- Medical Devices and Equipment

- Medical Education

- Medical Education and Training

- Medical Journals and Publishing

- Mobile Health and Telemedicine

- Narrative Medicine

- Neuroscience and Psychiatry

- Notable Notes

- Nutrition, Obesity, Exercise

- Obstetrics and Gynecology

- Occupational Health

- Ophthalmology

- Orthopedics

- Otolaryngology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Care

- Pathology and Laboratory Medicine

- Patient Care

- Patient Information

- Performance Improvement

- Performance Measures

- Perioperative Care and Consultation

- Pharmacoeconomics

- Pharmacoepidemiology

- Pharmacogenetics

- Pharmacy and Clinical Pharmacology

- Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation

- Physical Therapy

- Physician Leadership

- Population Health

- Primary Care

- Professional Well-being

- Professionalism

- Psychiatry and Behavioral Health

- Public Health

- Pulmonary Medicine

- Regulatory Agencies

- Reproductive Health

- Research, Methods, Statistics

- Resuscitation

- Rheumatology

- Risk Management

- Scientific Discovery and the Future of Medicine

- Shared Decision Making and Communication

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports Medicine

- Stem Cell Transplantation

- Substance Use and Addiction Medicine

- Surgical Innovation

- Surgical Pearls

- Teachable Moment

- Technology and Finance

- The Art of JAMA

- The Arts and Medicine

- The Rational Clinical Examination

- Tobacco and e-Cigarettes

- Translational Medicine

- Trauma and Injury

- Treatment Adherence

- Ultrasonography

- Users' Guide to the Medical Literature

- Vaccination

- Venous Thromboembolism

- Veterans Health

- Women's Health

- Workflow and Process

- Wound Care, Infection, Healing

- Download PDF

- Share X Facebook Email LinkedIn

- Permissions

US Health Policy—2020 and Beyond : Introducing a New JAMA Series

- 1 Medicine/Cardiology, Washington University School of Medicine in St Louis, St Louis, Missouri

- 2 JAMA , Chicago, Illinois

- Viewpoint The Implications of “Medicare for All” for US Hospitals Kevin A. Schulman, MD; Arnold Milstein, MD JAMA

Health care is always on the minds of the public, usually ranking among the top 3 concerns. Virtually all of the Democratic presidential candidates have discussed or will shortly detail health care proposals, whereas President Trump and the current administration recently expressed support for repealing the Affordable Care Act. With the presidential election just 18 months away, it is an opportune time to introduce a new health policy series in JAMA .

While various proposals to improve US health care will certainly differ in content, they will all by necessity share a common theme—a focus on reducing health care costs. In 2017, US health care spending reached $3.5 trillion, and such costs now consume approximately 18% of the gross domestic product (GDP). 1 Even though there has been a slight slowing in the annual growth of health care expenditures, 2 a recent projection suggested that by 2027, health care will consume 22% of the GDP, 3 outpacing the annual rate of inflation and increases in GDP over the next 5 years. This is an unsustainable trajectory.

At the same time, there are also crises of access and equity. Recent estimates suggest that nearly 14% of US residents are uninsured, and these numbers are markedly higher among people living in poverty compared with those who are wealthier, as well as among racial and ethnic minority populations compared with white populations. According to the 2017 National Healthcare Quality and Disparities Report, an estimated 40% of adults reported lacking a usual source of care, of which 15% indicated a financial or insurance reason for lacking regular access; these figures are also higher among impoverished persons and individuals of racial or ethnic minority. 4 Quality, though improving overall, remains inequitable as well: substantial differences across a range of quality domains persist for black and Hispanic individuals compared with white individuals.

The key question for policy makers is whether there are achievable health policies that will reduce the annual increase in health care expenditures yet at the same time increase access to care (fewer uninsured or underinsured), improve quality, and reduce inequities. Feasible policies likely must also maintain choice, which the majority of people repeatedly maintain is important to them.

To set the stage for a constructive policy debate, the first step requires defining the current starting point in coverage and spending ( Table ). For its population of 325 million in 2017, the United States spent $3.5 trillion on health care. Private health insurance covered approximately 197 million individuals and accounted for $1.2 trillion in health care spending. Medicare covered approximately 57 million individuals and accounted for approximately $706 billion in expenditures, and Medicaid covered approximately 72 million individuals and accounted for approximately $582 billion in health care spending. 2

These coverage numbers represent a significant shift over the past decade. Medicare has had relatively stable enrollment growth in its core populations of individuals aged 65 years or older and individuals younger than 65 years with end-stage renal disease, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, or disabilities. However, the proportion of Medicare beneficiaries enrolled in private Medicare plans (ie, Medicare Advantage), which are administered by private insurance companies, has increased to approximately one-third in 2018. 5 Even more marked changes have taken place in Medicaid. Medicaid is a heterogeneous program and covers children, pregnant women, and adults living in poverty or with disabilities. Although children represent approximately 44% of Medicaid recipients (34 million of a total of 72 million), they account for only approximately 19% of the cost. 6 Medicaid has expanded substantially with the passage of the Affordable Care Act, with an increase in the number of individuals covered from approximately 50 million in 2010 to an estimated 76 million by 2020, as additional states have indicated that they will expand Medicaid. 7

Across these payers, how does the United States spend $3.5 trillion in health care dollars? Various estimates are available, but overall, hospitals account for approximately 33% of spending, 1 , 2 physician and clinical services approximately 20%, 1 , 2 and prescription drugs (including retail, ambulatory, and hospital costs) about 18%. 8 Skilled nursing facilities, nursing homes, dental care, home health care, other health and residential care services (such as mental health and substance abuse facilities and ambulance services), and durable and nondurable medical equipment also contribute to the $3.5 trillion, but virtually none of those services or products individually exceed 5% of total expenditures. 1 , 2 An additional important expense involves the cost of medical devices, and with a continued increase in the number of hip and knee replacements each year, and expanding use of devices like transcatheter aortic valves and mitral valve clips, it is likely that the cost of devices, like the costs of drugs, will increase substantially in the coming years.

Because of efforts to reduce costs and improve quality, the past 8 years have seen a number of new initiatives in payment reform. For example, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services has been at the center of a major transition to value-based payment via many programs created or expanded under the Affordable Care Act. These include mandatory hospital-based programs like the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program, voluntary programs like accountable care organizations and bundled payments, and ambulatory care payment programs like the Merit-based Incentive Payment System. 9 - 12 At the state level, there has been additional experimentation, including global budgeting in Maryland 13 and a rural hospital global payment model in Pennsylvania, 14 among others. Private insurers have also been involved, with major shifts toward value-based care, innovative delivery models, and new experiments in vertical and horizontal integration. Care delivery organizations have consolidated substantially as well. In part because of this complexity, it is difficult to estimate the percentage of the US insured population that receive care under a value-based or alternative payment model, although it is clear that the proportion continues to increase.

Even though the Affordable Care Act and the health care industry in general have been modestly successful at improving coverage, there has been less progress in improving quality or reducing health care costs. Most delivery system reform efforts have been iterative rather than transformative, although it may be too early to assess whether these efforts are at least setting the stage for more major and sustained effective subsequent changes. Nonetheless, even though current health statistics do not necessarily reflect the entire health of a nation, the recent decline in life expectancy, 15 the recent increase in cardiovascular disease deaths and prevalence of cardiovascular disease morbidity and mortality, 16 the ongoing epidemic of opioid-related deaths, 17 and the sustained high prevalence of obesity in the United States, with substantial differences by race, ethnicity, and extent of urbanization, 18 - 20 raise the issue of whether the United States is addressing the health of its population effectively and spending $3.5 trillion wisely.

Many potential solutions have been proposed or may be possible. Some may be market based and some may rely more on regulation; some may prioritize population health and wellness and others may focus on innovation in technology and cures. All will require difficult choices, compromise, and prioritization. Simply spending more on health care will not be an effective approach.

The new JAMA series on health policy will consist of scholarly and evidence-based Viewpoints that will focus on solutions aimed at controlling health care costs, expanding access to care, and improving quality and value, with an emphasis on needed modifications of current health care programs and policies, and analysis of various proposals introduced by governmental agencies and by presidential candidates. In the first article in this series, Schulman and Milstein 21 discuss the implications of proposals that advocate for a “Medicare for all” approach for US health insurance as it would relate to hospitals. The authors explore the potential ramifications of a universal application of Medicare payment rates to hospitals, which currently account for the largest share of US health care spending. As epitomized by this scholarly Viewpoint, the goal of this new series is to ensure robust, enlightened, and meaningful discussion and debate about how health care should be paid for and delivered in the United States—not just for today or in 2020, but importantly, well beyond.

Corresponding Author: Karen E. Joynt Maddox, MD, MPH, Medicine/Cardiology, Washington University School of Medicine in St Louis, 660 S Euclid, St Louis, MO 63110 ( [email protected] ).

Published Online: April 4, 2019. doi:10.1001/jama.2019.3451

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: Dr Joynt Maddox reported contract work for the US Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Assistant Secretary of Planning and Evaluation. No other disclosures were reported.

See More About

Joynt Maddox KE , Bauchner H , Fontanarosa PB. US Health Policy—2020 and Beyond : Introducing a New JAMA Series . JAMA. 2019;321(17):1670–1672. doi:10.1001/jama.2019.3451

Manage citations:

© 2024

Artificial Intelligence Resource Center

Cardiology in JAMA : Read the Latest

Browse and subscribe to JAMA Network podcasts!

Others Also Liked

- Register for email alerts with links to free full-text articles

- Access PDFs of free articles

- Manage your interests

- Save searches and receive search alerts

- Fact sheets

- Facts in pictures

Publications

- Questions and answers

- Tools and toolkits

- HIV and AIDS

- Hypertension

- Mental disorders

- Top 10 causes of death

- All countries

- Eastern Mediterranean

- South-East Asia

- Western Pacific

- Data by country

- Country presence

- Country strengthening

- Country cooperation strategies

- News releases

- Feature stories

- Press conferences

- Commentaries

- Photo library

- Afghanistan

- Cholera

- Coronavirus disease (COVID-19)

- Greater Horn of Africa

- Israel and occupied Palestinian territory

- Disease Outbreak News

- Situation reports

- Weekly Epidemiological Record

- Surveillance

- Health emergency appeal

- International Health Regulations

- Independent Oversight and Advisory Committee

- Classifications

- Data collections

- Global Health Estimates

- Mortality Database

- Sustainable Development Goals

- Health Inequality Monitor

- Triple Billion

- Data collection tools

- Global Health Observatory

- Insights and visualizations

- COVID excess deaths

- World Health Statistics

- Partnerships

- Committees and advisory groups

- Collaborating centres

- Technical teams

- Organizational structure

- Initiatives

- General Programme of Work

- WHO Academy

- Investment case

- WHO Foundation

- External audit

- Financial statements

- Internal audit and investigations

- Programme Budget

- Results reports

- Governing bodies

- World Health Assembly

- Executive Board

- Member States Portal

- Health topics /

Research is indispensable for resolving public health challenges – whether it be tackling diseases of poverty, responding to rise of chronic diseases, or ensuring that mothers have access to safe delivery practices.

Likewise, shared vulnerability to global threats, such as severe acute respiratory syndrome, Ebola virus disease, Zika virus and avian influenza has mobilized global research efforts in support of enhancing capacity for preparedness and response. Research is strengthening surveillance, rapid diagnostics and development of vaccines and medicines.

Public-private partnerships and other innovative mechanisms for research are concentrating on neglected diseases in order to stimulate the development of vaccines, drugs and diagnostics where market forces alone are insufficient.

Research for health spans 5 generic areas of activity:

- measuring the magnitude and distribution of the health problem;

- understanding the diverse causes or the determinants of the problem, whether they are due to biological, behavioural, social or environmental factors;

- developing solutions or interventions that will help to prevent or mitigate the problem;

- implementing or delivering solutions through policies and programmes; and

- evaluating the impact of these solutions on the level and distribution of the problem.

High-quality research is essential to fulfilling WHO’s mandate for the attainment by all peoples of the highest possible level of health. One of the Organization’s core functions is to set international norms, standards and guidelines, including setting international standards for research.

Under the “WHO strategy on research for health”, the Organization works to identify research priorities, and promote and conduct research with the following 4 goals:

- Capacity - build capacity to strengthen health research systems within Member States.

- Priorities - support the setting of research priorities that meet health needs particularly in low- and middle-income countries.

- Standards - develop an enabling environment for research through the creation of norms and standards for good research practice.

- Translation - ensure quality evidence is turned into affordable health technologies and evidence-informed policy.

- Prequalification of medicines by WHO

- Global Observatory on Health R&D

- Global Observatory on Health Research and Development

- Implementation research toolkit

- Ethics in implementation research: participant's guide

- Ethics in implementation research: facilitator's guide

- Ethics in epidemics, emergencies and disasters: Research, surveillance and patient care: WHO training manual

- WHA58.34 Ministerial Summit on Health Research

- WHA60.15 WHO's role and responsibilities in health research

- WHA63.21 WHO's role and responsibilities in health research

- EB115/30 Ministerial Summit on Health Research: report by the Secretariat

- Science division

WHO advisory group convenes its first meeting on responsible use of the life sciences in Geneva

Challenging harmful masculinities and engaging men and boys in sexual and reproductive health

Stakeholders convene in Uganda on responsible use of the life sciences

The Technical Advisory Group on the Responsible Use of the Life Sciences and Dual-Use Research meets for the first time

WHO Science Council meeting, Geneva, Switzerland, 30-31 January 2024: report

This is a visual summary of the meeting of the WHO Science Council which took place on 30 and 31 January 2024.

WHO Technical Advisory Group on the Responsible Use of the Life Sciences and Dual-Use Research (TAG-RULS...

The Technical Advisory Group on the Responsible Use of the Life Sciences and Dual-Use Research (TAG-RULS DUR) was established in November 2023 to provide...

Target product profile to detect "Dracunculus medinensis" presence in environmental samples

Dracunculiasis, also known as Guinea-worm disease, is caused by infection with the parasitic nematode (the Guinea worm). In May 1986, the Thirty-ninth...

Target product profile to detect prepatent "Dracunculus medinensis" infections in animals

Dracunculiasis, also known as Guinea-worm disease, is caused by infection with the parasitic nematode Dracunculus medinensis (the Guinea worm). In May...

Coordinating R&D on antimicrobial resistance

Ensuring responsible use of life sciences research

Optimizing research and development processes for accelerated access to health products

Prioritizing diseases for research and development in emergency contexts

Promoting research on Buruli ulcer

Research in maternal, perinatal, and adolescent health

Undertaking health law research

Feature story

One year on, Global Observatory on Health R&D identifies striking gaps and inequalities

Video: Open access to health: WHO joins cOAlition S

Video: Multisectional research on sleeping sickness in Tanzania in the context of climate change

Related health topics

Clinical trials

Global health ethics

Health Laws

Intellectual property and trade

Related links

Research and Development Blueprint

WHO Collaborating Centres

R&D Blueprint for Action to Prevent Epidemics

International Clinical Trials Registry Platform

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Public Health Rep

- v.133(1 Suppl); Nov-Dec 2018

The Importance of Policy Change for Addressing Public Health Problems

Keshia m. pollack porter.

1 Department of Health Policy and Management, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, MD, USA

2 Institute for Health and Social Policy, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, MD, USA

3 Policy Change Workgroup, Bloomberg American Health Initiative, Baltimore, MD, USA

Lainie Rutkow

Emma e. mcginty.

4 Johns Hopkins Center for Mental Health and Addiction Policy Research, Baltimore, MD, USA

Some of the nation’s greatest public health successes would not have been possible without policy change. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s list of “Ten Great Public Health Achievements”—including motor vehicle safety, tobacco control, and maternal and infant health—all involved policy change. 1 Because of these public health achievements, the average life expectancy at birth for people living in the United States increased by more than 30 years, from 47.3 years in 1900 to 76.8 years in 2000. 2 The age-adjusted death rate in the United States continued to increase to 78.8 years in 2014. However, it decreased to 78.7 years in 2015 and then to 78.6 years in 2016. 2 This emerging trend is the result of numerous public health challenges, especially the opioid and obesity epidemics, which continue to burden society.

In this Commentary , we make the case for the central role of policy in mitigating America’s public health challenges. We first define policy, then propose principles that are essential for policy change and are based on the authors’ collective experiences, and conclude with implications for local health departments, academics, and the next generation of public health leaders.

Defining Policy

The term “policy” refers to a standard set of principles that guide a course of action. 3 - 5 Public policies are established by the government, whereas private or institutional policies are created by organizations for institutional use. Many public policies are legally binding, meaning that individuals and institutions in the public and private sectors must comply with them. In contrast, policies created by private institutions do not carry the force of law; however, within an institution, compliance with such policies may be required ( Table 1 ).

Examples of policy types, by government level of enactment and category

| Governmental | ||||

| Federal | Created by US Congress Codified in US code | Created by federal administrative agencies Codified in Code of Federal Regulations | Cases heard within the federal court system US Supreme Court is highest court in the nation | Presidential and gubernatorial executive orders are legally binding and allow for rapid policy change Some policies do not have the force of law (eg, guidance documents produced by federal, state, or local agencies) |

| State | Created by state legislature Codified in state legislative code | Created by state administrative agencies Codified in state code of regulations | Cases heard within the state court system | |

| Local | Created by local legislative body Codified in local legislative code | Created by local administrative agencies Codified in local code of regulations | Cases heard by local courts | |

| Nongovernmental | ||||

| Private | ||||

| Institutional | Must comply with laws at the federal, state, and local levels | Must comply with regulations at the federal, state, and local levels | May initiate or be subject to litigation | May develop policies to be applied by institutions |

a Includes appropriations processes.

b Includes policies that do not carry the force of law and/or are created outside the processes associated with legislation, regulation, and litigation.

In the United States, public policies may be enacted by federal, state, or local governments. Typically, public policies created by a lower level of government (eg, local) must comport with policies created by a higher level of government (eg, state). In addition, in some instances, a higher level of government (eg, federal) may preempt, or prevent, a lower level of government (eg, state) from enacting policies in a particular area. 6 This process, known as “ceiling preemption,” may stifle policy innovation, particularly at the local level.

Legally binding public policies fall into 3 primary categories: legislation, regulation, and litigation. Legislation, or statutory law, is created by a legislative body comprising elected representatives (eg, from US Congress, state general assembly, or city council). Regulations, which are promulgated by federal, state, or local administrative agencies, typically add specificity to policies that are described broadly in legislation. Finally, litigation refers to the body of public policy created through judicial opinions. Other policy tools, such as presidential or gubernatorial executive orders, are legally binding and bypass traditional legislative or regulatory processes, allowing for more rapid policy change.

Of note, some public policies do not carry the force of law. Most often, these policies are guidance documents produced by administrative agencies. Although guidance cannot be enforced, the expectation is that it will be followed or will provide answers when the law is unclear.

Principles for Effective Public Health Policy Change

Effective policy change is more likely to improve health when key principles are considered. We outline 4 principles that we believe bolster effective public health policy change. We define public health policy as laws, regulations, plans, and actions that are undertaken to achieve public health goals in a society. These principles are based on the authors' collective public health policy experiences and are grounded in the policy sciences literature. These principles are listed, along with references and examples of experiences that informed them, in Table 2 .

Principles for effective public health policy change and examples of how each principle has been used

| Use evidence to inform policy | is a publication designed to provide policy makers and other audiences with information on injury problems in Maryland and offer solutions on how they can be addressed through policy decisions. Each topic includes 3 primary sections: (1) How does this affect the United States? (2) How does this affect Maryland? and (3) What do we know about solutions? The purpose of the publication is to help bridge the gap between injury research and policy and to provide policy makers with evidence-based policy interventions to guide their initiatives. |

| Consider health equity | Equity is one of the core values of a Health Impact Assessment (HIA). HIA is a pragmatic approach to determine the potential positive and negative health effects of proposed policies, projects, or programs. Health equity can be advanced through HIAs by having the HIA team authentically engage the community to address the social determinants of health and root causes of inequities in the assessment and recommendations. For example, an HIA of proposed changes was made to the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program as part of the reauthorization of the federal Farm Bill in 2013-2014 under the Agricultural Act of 2014. The HIA process and products highlighted health equity, and the analysis informed policy discussion about inequities in the social determinants of health (eg, food insecurity). |

| Design policy with implementation in mind | Multiple US jurisdictions are considering legalization and implementation of safe consumption sites, which are places where people can legally use opioids or other previously purchased drugs under medical supervision. Safe consumption sites have been implemented in Canada and Europe and have been shown to decrease overdose deaths, transmission of infections, and public drug use; however, until recently, such sites did not exist in the United States. San Francisco announced plans to open a safe consumption site in 2018, and several other jurisdictions are considering doing the same. Safe consumption sites are illegal under current federal law and unpopular with some segments of the public because of their goal of improving the safety of drug use rather than eliminating drug use. Thus, implementation must be carefully planned. One example of a jurisdiction designing a safe consumption site policy with implementation in mind is Baltimore. As that city began considering a safe consumption space, a local foundation partnered with research experts to create a safe consumption site implementation strategy for Baltimore. |

| Use proactive research: policy translation strategies | The Consortium for Risk-Based Firearm Policy is a partnership between researchers from across the United States and a Washington, DC–based advocacy group focused on advancing evidence-based firearm policy. The consortium developed a new evidence-informed gun violence prevention policy, the gun violence restraining order law, and other evidence-based federal and state firearm policy recommendations. The consortium engages in various policy translation activities, including hosting state forums in which consortium researchers discuss the evidence behind the group’s policy proposals with state legislators and advocates; developing state-specific policy memorandums to educate policy audiences about the group’s recommendation; leading advocacy activities, such as legislative testimony; and delivering technical assistance to states that implement the consortium’s policies. , |

1. Use Evidence to Inform Policy

Although policy formation is a complex process involving multiple factors, including feasibility considerations, stakeholder interests, and political values, 3 sound research evidence should serve as the public health community’s starting point when it designs and advocates for public health policy solutions. Policy design should be based on the best available research evidence, with an understanding that the strength of that evidence may vary across public health issues and change over time. 14 For emerging public health problems, research evidence in support of policy solutions may be limited. In these scenarios, research on related policy mechanisms from other fields or in nations outside the United States may help inform policy development. 15 All policies, but especially new policies, little-studied policies, or evidence-based policies that are tailored to meet the needs of various subpopulations, should include mechanisms for monitoring and evaluation to determine the policy’s effectiveness. 16 , 17 Evaluation results can be used to refine implementation and support policy scale-up in additional jurisdictions.

Numerous evidence-based policies address public health problems. For example, “The Community Guide” is a collection of evidence-based findings from the Community Preventive Services Task Force and is one source of information for these evidence-based policies. 18 With consistent implementation, these known evidence-based policies can lead to dramatic short-term and long-term improvements in public health.

2. Consider Health Equity

Health equity refers to every person having an opportunity to attain his or her highest level of health. 19 In formulating policy, considering health equity means “optimizing the conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work, learn, and age; working with other sectors to address the factors that influence health; and naming racism as a force in determining how these social determinants are distributed.” 20 For example, data support the important role that residential segregation of black and white people, because of racist housing policies, has played in health disparities by race in the United States, leading to higher rates of child poverty and adverse birth outcomes among black children than among white children. 21

Policies that address and dismantle these underlying political, economic, social, and physical determinants of health can advance health equity. 22 For example, when land development changes are proposed, planners and policy makers should consider how these changes may lead to gentrification and displacement of historically marginalized populations, which have implications for their health. 23 By considering health equity, questions such as how a policy will increase or decrease access and opportunity for communities of color, in addition to how a policy may lead to other unintended consequences, can also be raised. Equity considerations can also be included during policy implementation, evaluation, and monitoring, to ensure that equity is promoted through indicators that can document progress toward health equity–related goals (eg, percentage of policies that address the social determinants of health). 24

3. Design Policy With Implementation in Mind

Policy should be designed with implementation in mind. Too often, enactment of a new policy (eg, when a bill is signed into law) is seen as the end of the policy process. 25 Instead, it is only the beginning. Implementation determines the policy’s success or failure. Policies that include clear, concrete definitions of the target population and detailed regulations are more likely to be successfully implemented than policies that leave such criteria subject to interpretation. 26 , 27 For example, to be effectively implemented, a state law prohibiting the sale of sugar-sweetened beverages in schools should define which types of schools are subject to the law, criteria for defining a sugar-sweetened beverage, the date by which schools must comply with the law, and the sanctions that will be imposed on schools that do not comply with the law. These types of details are typically developed during the regulatory process, after enactment of federal, state, and local laws.

Implementation should be considered from the beginning of the policy design process. People who design policy should contemplate factors such as whether a new or existing agency will implement and enforce the policy, whether new personnel will need to be hired and/or whether existing personnel will need to be trained, and whether administrative changes (eg, creation of new eligibility forms or electronic monitoring systems) are needed. 28 - 30 Policies that make minor changes to existing policies are simpler and quicker to implement than policies that make major changes to the status quo, and those designing public health policies should plan accordingly, in terms of both resource allocation and timing. 27 , 29 Full implementation of policies that enact new programs, for example, will take substantially longer than full implementation of policies that change only eligibility criteria for, or categories of, services covered by existing policies.

4. Use Proactive Research-Policy Translation Strategies

To increase translation of research into policy, proactive strategies that bridge the research and policy worlds to increase adoption and implementation of policies shown to be effective in research studies are needed. 16 , 31 Researchers and policy makers have unique skill sets and professional incentives. For example, researchers are skilled in producing research evidence, and the academic promotion process emphasizes peer-reviewed publications of research findings. In contrast, policy makers are skilled in policy development, analysis, political negotiation, and coalition building, and their professional incentives are focused on reelection. 32 - 34 In addition, researchers have deep expertise in a narrowly defined field of study, whereas policy makers have working knowledge across an array of topics. Furthermore, although research can be slow, the policy process often moves quickly, with short windows of opportunity for new policies to be developed and enacted. For example, some state legislative sessions are as short as 30 days per year. 35 To advance evidence-based public health policy, research-policy translation models must bridge these differences. These models should include training for researchers about how to ask policy-relevant research questions, the steps of policy process, the politics of the policy process, and how to engage with policy makers. 16 , 36 - 38

To substantially increase translation of evidence into policy, however, research-policy translation initiatives must go beyond these activities to include long-term coalition building and formal partnerships between key research and policy stakeholders (eg, academic–public health department partnerships 39 , 40 and national coalitions focused on advancing evidence-based policy). 41 An example of the coalition model of research-policy translation is the Consortium for Risk-Based Firearm Policy, a partnership between researchers from across the United States and an advocacy group based in Washington, DC, that focuses on advancing evidence-based firearm policy. 42 Since its formation in 2013, the consortium has developed an evidence-informed gun violence prevention policy, created a gun violence restraining order law, and conducted a range of activities—including hosting forums in which consortium researchers discuss the evidence with state legislators and advocates 42 , 43 —that contributed to the law’s passage in 8 states. 44

These types of formal research-policy translation models can address multiple barriers to enactment and implementation of evidence-based policy. Engagement of broad coalitions can help increase stakeholders’ recognition of the value of policy change and facilitate partnerships between advocates and policy makers adept in formulating political strategy. In addition, these types of models can help to identify gaps in the evidence base of public health policy issues and, by strengthening partnerships between researchers and policy makers, inform the development of policy-relevant research to fill those gaps.

Implications for Public Health

Various actors play important roles in applying these principles to the design and implementation of evidence-based public health policy. Public health departments are responsible for numerous local and state public health policies. For these public health professionals, applying these principles involves engaging with stakeholders from other sectors (eg, transportation and planning) in other salient government agencies to promote strong cross-sector partnerships. Decisions made in sectors outside of public health and health care, such as education, transportation, and criminal justice, strongly influence health and well-being. 45 Thus, efforts to improve public health through policy change must involve decision makers and stakeholders from these other sectors. In the United States, more communities than before are adopting multisector approaches, and local and state health departments are initiating much of this activity. 46 Tools such as Health Impact Assessments (HIAs) are being used to identify potential public health effects of decisions proposed by other sectors ( Table 2 ). An HIA is a practical approach to determine the potential, and often overlooked, health effects of proposed policies, projects, or programs from nonhealth sectors, as well as provide practical recommendations to minimize risks and improve health. 47 Involving these other sectors in decisions that influence the determinants of health can also address underlying inequities and present an opportunity for health departments to consider health equity. 8

For academic practitioners, advancing policy change requires that academics not only generate policy-relevant research, but also translate and disseminate findings to practitioners, advocates, and policy makers. Having open communication channels between academics and public health practitioners provides opportunities for practitioners to share the types of data that are useful for policy debates and advocacy efforts, and it helps ensure that academics are asking the right questions needed to generate policy-relevant results. Some faculty are reluctant to engage in these translational and policy engagement activities because these activities are often not evaluated as part of their promotion process. Having institutional supports that recognize policy engagement and translational activities as part of scholarship and consider these activities during the faculty promotion process could bolster faculty participation in policy change activities. 48

Academics also have the important role of training future public health leaders to amplify public health policy change. Policy development is one of the core functions of public health 49 ; however, public health professionals have cited policy development as one of the areas in which training is needed. 50 Future leaders need to be trained in policy sciences, including policy analysis, communication, implementation, evaluation, and translational research, along with the politics of the policy process. In addition to these policy competencies, training in health equity and research translation will further prepare future leaders to engage in effective public health policy change.

Policy change can help address current and future public health issues in the United States. The 4 principles we outlined should undergird all policy efforts to optimize their impact.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors declared the following funding with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This article was produced with the support of the Bloomberg American Health Initiative, which is funded by a grant from the Bloomberg Philanthropies.

- News & Highlights

- Publications and Documents

- Postgraduate Education

- Browse Our Courses

- C/T Research Academy

- K12 Investigator Training

- Harvard Catalyst On-Demand

- Translational Innovator

- SMART IRB Reliance Request

- Biostatistics Consulting

- Regulatory Support

- Pilot Funding

- Informatics Program

- Community Engagement

- Diversity Inclusion

- Research Enrollment and Diversity

- Harvard Catalyst Profiles

Community Engagement Program

Supporting bi-directional community engagement to improve the relevance, quality, and impact of research.

- Getting Started

- Resources for Equity in Research

- Community-Engaged Student Practice Placement

- Maternal Health Equity

- Youth Mental Health

- Leadership and Membership

- Past Members

- Study Review Rubric

- Community Ambassador Initiative

- Implementation Science Working Group

- Past Webinars & Podcasts

- Policy Atlas

- Community Advisory Board

For more information:

Policy research.

Health Policy research aims to understand how policies, regulations, and practices may influence population health. Translating research into evidence-based policies is an important approach to improve population health and address health disparities.

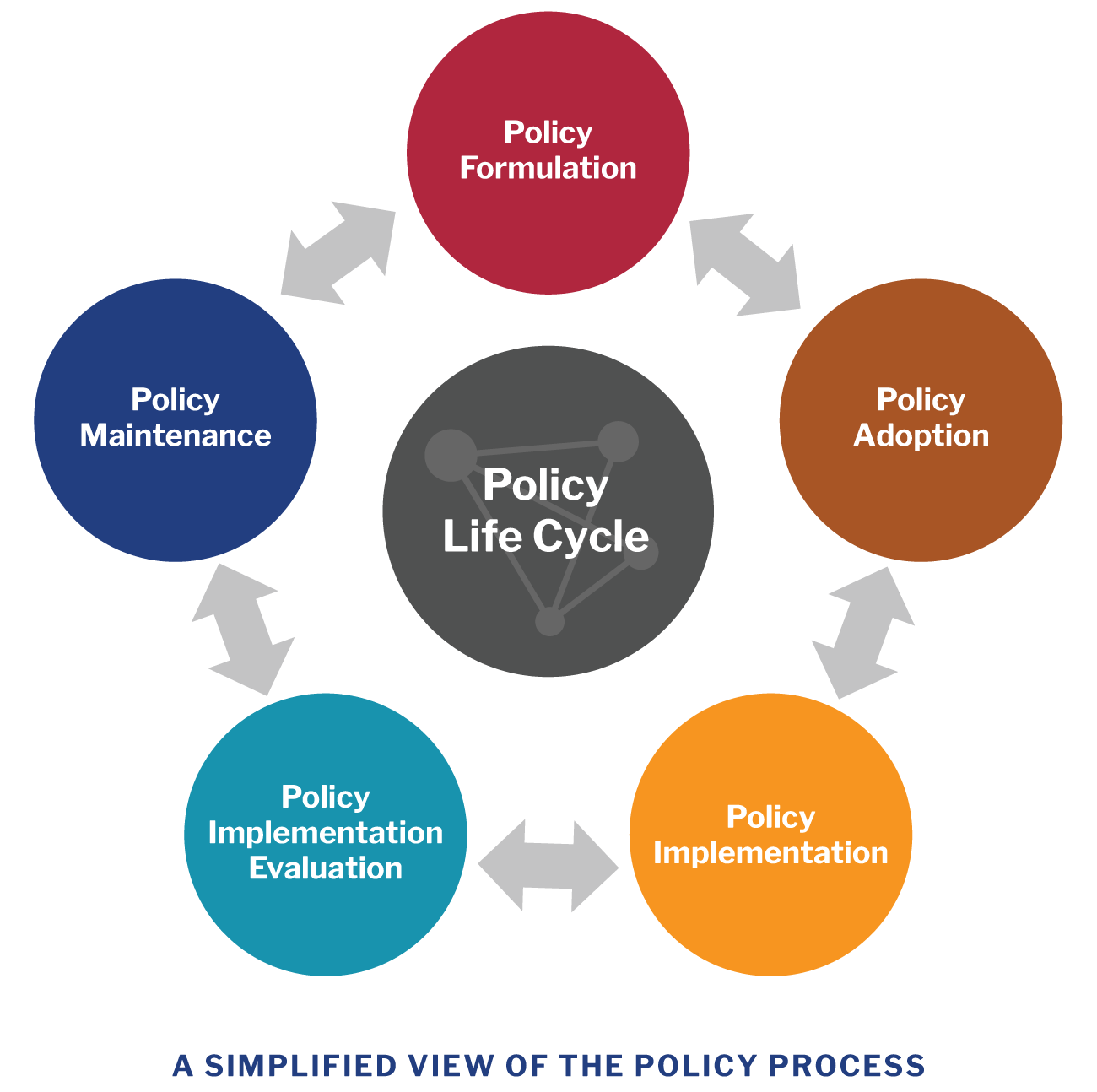

The policy process, although complex and dynamic, provides an opportunity to ask different types of research questions and apply various methodologies – from public health law to health services research to cost-effectiveness to policy implementation and dissemination.

View image description .

Harvard Catalyst Policy Atlas

Policy Atlas is a free, web-based, curated research platform that catalogues downloadable policy-relevant data, use cases, and instructional materials and tools to facilitate health policy research. The Policy Atlas includes data on various health topics and policies, and may be used for research, evaluation, or a quick summary of state rankings or health trends. The topics vary from health laws and bills, to social and environmental determinants of health, to health disparities, and other topics.

Examples of Policy Research

Policy adoption study: Examination of Trends and Evidence-Based Elements in State Physical Education Legislation: A Content Analysis

This study comprehensively reviewed existing state legislation on school physical education (PE) requirements to identify evidence-based policies. The authors found that despite frequent PE bill introduction, the number of evidence-based bills was relatively low.

Policy implementation study: Political Analysis for Health Policy Implementation

To better understand factors that may affect the process and the success of policy implementation, a political analysis was conducted to identify stakeholder groups that are likely to play a critical role in the process. The results revealed that six groups impact the implementation process: interest groups, bureaucratic, budget, leadership, beneficiary, and external actors.

Policy impact evaluation: Reducing Disparities in Tobacco Retailer Density by Banning Tobacco Product Sales Near Schools

This study examined whether a policy ban on tobacco product sales near schools could reduce existing socioeconomic and racial/ethnic disparities in tobacco retailer density in Missouri and New York. The findings suggested that the policy ban would reduce or eliminate existing disparities in tobacco retailer density by income level and by proportion of African American residents.

Other Resources

Health Policy Analysis and Evidence : Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) resource on health policy analysis and evidence-driven policy to improve population health.

Health in All Policies (American Public Health Association) : a policy approach to address social and other factors that influence health and equity.

Four-Part Webinar Series on Policy Evaluation (National Collaboration on Childhood Obesity Research) : This seminar series aims to increase skills of researchers and practitioners in policy evaluation effectiveness.

Research Tools (Center for Health Economics and Policy, Washington University in St. Louis) : health economics and policy research tools, including cost effectiveness, policy analysis toolkit, and policy analysis web series.

Theory & Methods (Center for Public Health Law Research) : public law/ legal epidemiology methods for conducting research on the impact of laws and legislation on public health.

Introduction to Legal Mapping (ChangeLab Solutions) : an introduction to legal mapping, a method to determine what laws exist on a certain topic, collect and summarize policy data, and ultimately estimate the effects of these policies on health outcomes.

The Methods Centers at Pardee RAND Graduate School : a resource on research methods for conducting policy research, including qualitative and mixed methods, decision making, causal inference, decision making and data science and gaming approaches.

View PDF of the above information.

Health Policy

Goal: use health policy to prevent disease and improve health..

Health policy can have a major impact on health and well-being. Healthy People 2030 focuses on keeping people safe and healthy through laws and policies at the local, state, territorial, and federal level.

Evidence-based health policies can help prevent disease and promote health. For example, smoke-free policies can help prevent smoking initiation and increase quit attempts. Similarly, policies requiring community water systems to provide fluoridated water can improve oral health.

Establishing informed policies is key to improving health nationwide.

Objective Status

Learn more about objective types

Related Objectives

The following is a sample of objectives related to this topic. Some objectives may include population data.

Health Policy — General

- Environmental Health

- Tobacco Use

Other topics you may be interested in

- Oral Conditions

The Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (ODPHP) cannot attest to the accuracy of a non-federal website.

Linking to a non-federal website does not constitute an endorsement by ODPHP or any of its employees of the sponsors or the information and products presented on the website.

You will be subject to the destination website's privacy policy when you follow the link.

- Biochemistry and Molecular Biology

- Biostatistics

- Environmental Health and Engineering

- Epidemiology

- Health Policy and Management

- Health, Behavior and Society

- International Health

- Mental Health

- Molecular Microbiology and Immunology

- Population, Family and Reproductive Health

- Program Finder

- Admissions Services

- Course Directory

- Academic Calendar

- Hybrid Campus

- Lecture Series

- Convocation

- Strategy and Development

- Implementation and Impact

- Integrity and Oversight

- In the School

- In the Field

- In Baltimore

- Resources for Practitioners

- Articles & News Releases

- In The News

- Statements & Announcements

- At a Glance

- Student Life

- Strategic Priorities

- Inclusion, Diversity, Anti-Racism, and Equity (IDARE)

- What is Public Health?

research@BSPH

The School’s research endeavors aim to improve the public’s health in the U.S. and throughout the world.

- Funding Opportunities and Support

- Faculty Innovation Award Winners

Conducting Research That Addresses Public Health Issues Worldwide

Systematic and rigorous inquiry allows us to discover the fundamental mechanisms and causes of disease and disparities. At our Office of Research ( research@BSPH), we translate that knowledge to develop, evaluate, and disseminate treatment and prevention strategies and inform public health practice. Research along this entire spectrum represents a fundamental mission of the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

From laboratories at Baltimore’s Wolfe Street building, to Bangladesh maternity wards in densely packed neighborhoods, to field studies in rural Botswana, Bloomberg School faculty lead research that directly addresses the most critical public health issues worldwide. Research spans from molecules to societies and relies on methodologies as diverse as bench science and epidemiology. That research is translated into impact, from discovering ways to eliminate malaria, increase healthy behavior, reduce the toll of chronic disease, improve the health of mothers and infants, or change the biology of aging.

120+ countries

engaged in research activity by BSPH faculty and teams.

of all federal grants and contracts awarded to schools of public health are awarded to BSPH.

citations on publications where BSPH was listed in the authors' affiliation in 2019-2023.

publications where BSPH was listed in the authors' affiliation in 2019-2023.

Departments

Our 10 departments offer faculty and students the flexibility to focus on a variety of public health disciplines

Centers and Institutes Directory

Our 80+ Centers and Institutes provide a unique combination of breadth and depth, and rich opportunities for collaboration

Institutional Review Board (IRB)

The Institutional Review Board (IRB) oversees two IRBs registered with the U.S. Office of Human Research Protections, IRB X and IRB FC, which meet weekly to review human subjects research applications for Bloomberg School faculty and students

Generosity helps our community think outside the traditional boundaries of public health, working across disciplines and industries, to translate research into innovative health interventions and practices

Introducing the research@BSPH Ecosystem

The research@BSPH ecosystem aims to foster an interdependent sense of community among faculty researchers, their research teams, administration, and staff that leverages knowledge and develops shared responses to challenges. The ultimate goal is to work collectively to reduce administrative and bureaucratic barriers related to conducting experiments, recruiting participants, analyzing data, hiring staff, and more, so that faculty can focus on their core academic pursuits.

Research at the Bloomberg School is a team sport.

In order to provide extensive guidance, infrastructure, and support in pursuit of its research mission, research@BSPH employs three core areas: strategy and development, implementation and impact, and integrity and oversight. Our exceptional research teams comprised of faculty, postdoctoral fellows, students, and committed staff are united in our collaborative, collegial, and entrepreneurial approach to problem solving. T he Bloomberg School ensures that our research is accomplished according to the highest ethical standards and complies with all regulatory requirements. In addition to our institutional review board (IRB) which provides oversight for human subjects research, basic science studies employee techniques to ensure the reproducibility of research.

Research@BSPH in the News

Four bloomberg school faculty elected to national academy of medicine.

Considered one of the highest honors in the fields of health and medicine, NAM membership recognizes outstanding professional achievements and commitment to service.

The Maryland Maternal Health Innovation Program Grant Renewed with Johns Hopkins

Lerner center for public health advocacy announces inaugural sommer klag advocacy impact award winners.

Bloomberg School faculty Nadia Akseer and Cass Crifasi selected winners at Advocacy Impact Awards Pitch Competition

The independent source for health policy research, polling, and news.

Congress and the Executive Branch and Health Policy

Published: May 28, 2024

KFF Author:

Julie Rovner

Table of Contents

Introduction.

The federal government is not the only place health policy is made in the U.S., but it is by far the most influential. Of the $4.5 trillion the U.S. spent on health in 2022, the federal government was responsible for roughly a third of all health services. The payment and coverage policies set for the Medicare program, in particular, often serve as a model for the private sector. Many health programs at the state and local levels are also impacted by federal health policy, either through direct spending or rules and requirements. Federal health policy is primarily guided by Congress, but carried out by the executive branch, predominantly by the Department of Health and Human Services.

The Federal Role in Health Policy

No one is “in charge” of the fragmented U.S. health system, but the federal government probably has the most influence, a role that has grown over the last 75 years. Today the federal government pays for care, provides it, regulates it, and sponsors biomedical research and medical training.

The federal government pays for health coverage for well over 100 million Americans through Medicare , Medicaid , the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), the Veterans’ Health Administration, the Indian Health Service, and the Affordable Care Act (ACA) . It also pays to help provide insurance coverage for tens of millions who are active-duty and retired military and for civilian federal workers.

Federal taxpayers also underwrite billions of dollars in health research, mainly through the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ).

Federal public health policy is spearheaded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Its portfolio includes tracking not just infectious disease outbreaks in the U.S. and worldwide, but also conducting and sponsoring public health research and tracking national health statistics.

The Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) funds critical health programs for underserved Americans (including Community Health Centers) and runs workforce education programs to bring more health services to places without enough health care providers.

Meanwhile, in addition to overseeing the nation’s largest health programs, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) also operates the federal insurance Marketplaces created by the ACA and enforces rules made by the law for private insurance policies.

While the federal government exercises significant authority over medical care and its practice and distribution, state and local governments still have key roles to play.

States oversee the licensing of health care professionals, distribution of health care resources, and regulation of health insurance plans that are not underwritten by employers themselves. State and local governments share responsibility for most public health activities and often operate safety-net facilities in areas with shortages of medical resources.

The Three Branches of Government and How They Impact Health Policy

All three branches of the federal government – Congress, the executive branch, and the judiciary – play important roles in health policy.

Congress makes laws that create new programs or modify existing ones. It also conducts “oversight” of how the executive branch implements the laws Congress has passed. Congress also sets the budget for “discretionary” and “mandatory” health programs ( see below ) and provides those dollar amounts.

The executive branch carries out the laws made by Congress and operates the federal health programs, often filling in details Congress has left out through rules and regulations. Federal workers in the health arena may provide direct patient care, regulate how others provide care, set payment rates and policies, conduct medical or health systems research, regulate products sold by the private sector, and manage the billions of dollars the federal government spends on the health-industrial complex.

Historically, the judiciary has had the smallest role in health policy but has played a pivotal role in recent cases. It passes judgment on how or whether certain laws or policies can be carried out and settles disputes between the federal government, individuals, states, and private companies over how health care is regulated and delivered. Recent significant decisions from the Supreme Court have affected the legality and availability of abortion and other reproductive health services and the constitutionality of major portions of the ACA.

The Executive Branch – The White House

Although most of the executive branch’s health policies are implemented by the Department of Health and Human Services (and to a smaller extent, the Departments of Labor and Justice), over the past several decades the White House itself has taken on a more prominent role in policy formation. The White House Office of Management and Budget not only coordinates the annual funding requests for the entire executive branch, but it also reviews and approves proposed regulations, Congressional testimony, and policy recommendations from the various departments. The White House also has its own policy support agencies – including the National Security Council, the National Economic Council, the Domestic Policy Council, and the Council of Economic Advisors, that augment what the President receives from other portions of the executive branch.

How the Department of Health and Human Services is Structured

Most federal health policy is made through the Department of Health and Human Services . Exceptions include the Veterans Health Administration , run by the Department of Veterans Affairs; TRICARE , the health insurance program for active-duty military members and dependents, run by the Defense Department; and the Federal Employees Health Benefits Program (FEHB), which provides health insurance for civilian federal workers and families and is run by the independent agency the Office of Personnel Management.

The health-related agencies within HHS are roughly divided into the resource delivery, research, regulatory, and training agencies that comprise the U.S. Public Health Service and the health insurance programs run by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS).

Nine of the 12 operating divisions of HHS are part of the U.S. Public Health Service, which also plays a role in U.S. global health programs. They are:

- The Administration for Strategic Preparedness and Response (ASPR)

- The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ)

- The Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR)

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)

- The Food and Drug Administration (FDA)

- The Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA)

- The Indian Health Service (IHS)

- The National Institutes of Health (NIH)

- The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA)

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) is by far the largest operating division of HHS. It oversees not just the Medicare and Medicaid programs, but also the federal Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) and the health insurance portions of the Affordable Care Act. Together, the programs under the auspices of CMS account for nearly a quarter of all federal spending in fiscal 2023 , cost an estimated $1.5 Trillion in fiscal 2023, and served more than 170 million Americans – more than half the population.

Who Makes Health Policy in Congress?

How Congress oversees the federal health care-industrial complex is almost as byzantine as the U.S. health system itself. Jurisdiction and responsibility for various health agencies and policies is divided among more than two dozen committees in the House and Senate (see Table 1 and Table 2 below).

In each chamber, however, three major committees deal with most health issues.

In the House, the Ways and Means Committee , which sets tax policy, oversees Part A of Medicare (because it is funded by the Social Security payroll tax) and shares jurisdiction over other parts of the Medicare program with the Energy and Commerce Committee. Ways and Means also oversees tax subsidies and credits for the Affordable Care Act and tax policy for most employer-provided insurance.

The Energy and Commerce Committee has sole jurisdiction over the Medicaid program in the House and shares jurisdiction over Medicare Parts B, C, and D with Ways and Means. Energy and Commerce also oversees the U.S. Public Health Service, whose agencies include the Food and Drug Administration, the National Institutes of Health, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

While Ways and Means and Energy and Commerce are in charge of the policymaking for most of the federal government’s health programs, the actual amounts allocated for many of those programs are determined by the House Appropriations Committee through the annual Labor-Health and Human Services-Education and Related Agencies spending bill.

In the Senate, responsibility for health programs is divided somewhat differently. The Senate Finance Committee , which, like House Ways and Means, is in charge of tax policy, oversees all of Medicare and Medicaid and most of the ACA.

The Senate counterpart to the House Energy and Commerce Committee is the Senate Health, Education, Labor and Pensions Committee , which has jurisdiction over the Public Health Service (but not Medicare or Medicaid).

The Senate Appropriations Committee , like the one in the House, sets actual spending for discretionary programs as part of its annual Labor-HHS-Education spending bill.

The Federal Budget Process

Under Article 1 of the U.S. Constitution , Congress is granted the exclusive power to “lay and collect Taxes, Duties, Imposts and Excises, and to pay the Debts and provide for the common Defence and General Welfare of the United States.”

In 1974, lawmakers passed the Congressional Budget and Impoundment Control Act in an effort to standardize the annual process for deciding tax and spending policy for each federal fiscal year and to prevent the executive branch from making spending policy reserved to Congress. Among other things, it created the House and Senate Budget Committees and set timetables for each step of the budget process.

Perhaps most significantly, the 1974 Budget Act also created the Congressional Budget Office (CBO). This non-partisan agency has come to play a pivotal role in not just the budget process, but in the lawmaking process in general. The CBO issues economic forecasts, policy options, and other analytical reports, but it most significantly produces estimates of how much individual legislation would cost or save the federal government. Those estimates can and do often determine if legislation passes or fails.

The annual budget process is supposed to begin the first Monday in February, when the President is to present his proposed budget for the fiscal year that begins the following Oct. 1. This is one of the few deadlines in the Budget Act that is usually met.

After that, the action moves to Congress. The House and Senate Budget Committees each write their own “Budget Resolution,” a spending blueprint for the year that includes annual totals for mandatory and discretionary spending. Because mandatory spending (roughly two-thirds of the budget) is automatic unless changed by Congress, the budget resolution may also include “reconciliation instructions” to the committees that oversee those programs (also known as “authorizing” committees) to make changes to bring the cost of the mandatory programs in line with the terms of the budget resolution. The discretionary total will eventually be divided by the House and Senate Appropriations Committees between the 12 subcommittees, each responsible for a single annual spending (appropriations) bill. Most of those bills cover multiple agencies – the appropriations bill for the Department of Health and Human Services, for example, also includes funding for the Departments of Labor and Education.

After the budget resolution is approved by each chamber’s Budget Committee, it goes to the House and Senate floor, respectively, for debate. Assuming the resolutions are approved, a “conference committee” comprised of members from each chamber is tasked with working out the differences between the respective versions. A final compromise budget resolution is supposed to be approved by both chambers by April 15 of each year. ( This rarely happens .) Because the final product is a resolution rather than a bill, the budget does not go to the President to sign or veto.

The annual appropriations process kicks off May 15, when the House may start considering the 12 annual spending bills for the fiscal year that begins Oct. 1. By tradition, spending bills originate in the House, although sometimes, if the House is delayed in acting, the Senate will take up its own version of an appropriation first. The House is supposed to complete action on all 12 spending bills by June 30, in order to provide enough time to let the Senate act, and for a conference committee to negotiate a final version that each chamber can approve by October 1.

That October 1 deadline is the only one with consequences if it is not met. Unless an appropriations bill for each federal agency is passed by Congress and signed by the President by the start of the fiscal year, that agency must shut down all “non-essential” activities funded by discretionary spending until funding is approved. Because Congress rarely passes all 12 of the appropriations bills by the start of the fiscal year (the last time was in 1996, for fiscal year 1997), it can buy extra time by passing a “continuing resolution” (CR) that keeps money flowing, usually at the previous fiscal year’s level. CRs can last as little as a day and as much as the full fiscal year and may cover all of the federal government (if none of the regular appropriations are done) or just the departments for the unfinished bills. Congress may, and frequently does, pass multiple CRs while it works to complete the appropriations process.

While each appropriations bill is supposed to be considered individually, to save time (and sometimes to win needed votes), a few, several, or all the bills may be packaged into a single “omnibus” measure. Bills that package only a handful of appropriations bills are cheekily known as “minibuses.”

Meanwhile, if the budget resolution includes reconciliation instructions, that process proceeds on a separate track. The committees in charge of the programs requiring alterations each vote on and report their proposals to the respective budget committees, which assemble all of the changes into a single bill. At this point, the budget committees’ role is purely ministerial; it may not change any of the provisions approved by the authorizing committees.

Reconciliation legislation is frequently the vehicle for significant health policy changes, partly because Medicare and Medicaid are mandatory programs. Reconciliation bills are subject to special rules, notably on the Senate floor, which include debate time limitations (no filibusters) and restrictions on amendments. Reconciliation bills also may not contain provisions that do not pertain directly to taxing or spending.

Unlike the appropriations bills, nothing happens if Congress does not meet the Budget Act’s deadline to finish the reconciliation process, June 15. In fact, in more than a few cases, Congress has not completed work on reconciliation bills until the calendar year AFTER they were begun.

A (Very Brief) Explanation of the Regulatory Process

Congress writes the nation’s laws, but it cannot account for every detail in legislation. So, it often leaves key decisions about how to interpret and enforce those laws to the various executive departments. Those departments write (and often rewrite) rules and regulations according to a very stringent process laid out by the 1946 Administrative Procedure Act (APA). The APA is intended to keep the executive branch’s decision-making transparent and to allow public input into how laws are interpreted and enforced.

Most federal regulations use the APA’s “informal rulemaking” process, also known as “notice and comment rulemaking,” which consists of four main parts:

- Publication of a “Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (NPRM)” in the Federal Register , a daily publication of executive branch activities.

- Solicitation to the public to submit written comments for a specific period of time (usually from 30 to 90 days).

- Agency consideration of public reaction to the proposed rule; and, finally

- Publication of a final rule, with an explanation including how the agency took the public comments into account and what changes, if any, were made from the proposed rule. Final rules also include an effective date, which can be no less than 30 days but may be more than a year in the future.

In situations where time is of the essence, federal agencies may truncate that process by issuing “interim final rules,” which can take effect even before the public is given a chance to comment. Such rules may or may not be revised later.

Not all federal interpretation of laws uses the APA’s specified regulatory process. Federal officials also distribute guidance, agency opinions, or “statements of policy.”

Future Outlook

Given how fragmented health policy is in both Congress and the executive branch, it should not be a surprise that major changes are difficult and rare.

Add to that an electorate divided over whether the federal government should be more involved or less involved in the health sector, and huge lobbying clout from various interest groups whose members make a lot of money from the current operation of the system, and you have a prescription for inertia.

Another problem is that when a new health policy can dodge the minefield of obstacles to become law, it almost by definition represents a compromise that may help it win enough votes for passage, but is more likely to complicate an already byzantine system further.

Unless the health system completely breaks down, it seems unlikely that federal policymakers will be able to move the needle very far in either a conservative or a liberal direction.

- FAQs on Health Spending, the Federal Budget, and Budget Enforcement Tools

- Medicare 101

- Medicaid 101

- The Affordable Care Act 101

- Employer-Sponsored Health Insurance

- The Regulation of Private Health Insurance

- The U.S. Government and Global Health

- The U.S. Congress and Global Health: A Primer

Rovner, Julie, Congress, the Executive Branch, and Health Policy. In Altman, Drew (Editor), Health Policy 101, (KFF, May 28, 2024) https://www.kff.org/health-policy-101-congress-and-the-executive-branch-and-health-policy/ (date accessed).

Mobile Menu Overlay

The White House 1600 Pennsylvania Ave NW Washington, DC 20500

White House Shares Government, Private Sector, Academic, and Non-Profit Actions to Accelerate Progress on Mental Health Research

The United States is facing an unprecedented mental health crisis impacting Americans of all ages. To tackle this crisis, the Biden-Harris Administration has taken bold steps to transform how mental health is understood, accessed, and treated. Under President Biden’s Unity Agenda, the Biden-Harris Administration released a comprehensive mental health strategy and mental health research priorities . These steps aim to make mental health care more affordable and accessible and improve health outcomes for all Americans.

As a part of Mental Health Awareness Month, the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy called on government agencies, the private sector, nonprofit organizations, and academia to share the actions they are taking to expand and improve mental health research in the United States. These actions address key research priorities and move us closer to a future where every American has access to the best available care when and where they need it.

Government Actions

- The National Institutes of Health (NIH) Common Fund’s Community Partnerships to Advance Science for Society (ComPASS) Program announced 25 community-led research awards. The ComPASS program provides an unprecedented opportunity for communities to lead innovative intervention projects that study ways to address the underlying structural factors that affect health and health equity. Awards include research focused on addressing stigmatization of behavioral health and services and improving access to behavioral health services in Hispanic, low-income, rural, and LGBTQ+ communities.

- Accelerating Medicines Partnership® Program for Schizophrenia (AMP SCZ) released its first research data set — AMP SCZ 1.0 —through a collaboration of the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), the Foundation for NIH, the Food and Drug Administration, and multiple public and private partners. To improve the understanding of schizophrenia and to identify new and better targets for treatment, AMP SCZ established a research network that examines trajectories for people who are at clinical high risk for psychosis. The network also develops psychosis prediction algorithms using biomarkers, clinical data, and existing clinical high risk-related datasets.

- NIMH’s Individually Measured Phenotypes to Advance Computational Translation in Mental Health program is a new initiative focused on using behavioral measures and computational methods to define novel clinical signatures that can be used for individual-level prediction and clinical decision making in treating mental disorders . As one example of research supported through this initiative, researchers at the University of Washington are applying computational modeling strategies to behavioral data collected through a smartphone app, with the goal of predicting and preventing serious negative outcomes for people who experience hallucinations.

- NIMH awarded research grants to develop and test innovative psychosocial interventions to prevent suicide. Researchers at San Diego State, one of the grant recipients, are combining an existing intervention—the Safety Planning Intervention—with patient navigator services, and testing the effectiveness of this novel combined intervention in reducing suicide risk among sexual and gender minority youth and young adults.