Cell-Phone Addiction: A Review

Affiliations.

- 1 Department of Psychobiology, Psychology Faculty, Complutense University of Madrid (Universidad Complutense de Madrid) , Madrid , Spain.

- 2 Department of Psychobiology, Psychology Faculty, Complutense University of Madrid (Universidad Complutense de Madrid), Madrid, Spain; Clinical Management of Mental Health Unit, Biomedical Research Institute of Málaga, Regional University Hospital of Málaga (Unidad de Gestión Clínica de Salud Mental, Hospital Regional Universitario de Málaga, Instituto de Investigación Biomédica de Málaga - IBIMA), Málaga, Spain.

- 3 Istituto de Investigación i+12, Hospital Universitario 12 de Octubre de Madrid , Madrid , Spain.

- PMID: 27822187

- PMCID: PMC5076301

- DOI: 10.3389/fpsyt.2016.00175

We present a review of the studies that have been published about addiction to cell phones. We analyze the concept of cell-phone addiction as well as its prevalence, study methodologies, psychological features, and associated psychiatric comorbidities. Research in this field has generally evolved from a global view of the cell phone as a device to its analysis via applications and contents. The diversity of criteria and methodological approaches that have been used is notable, as is a certain lack of conceptual delimitation that has resulted in a broad spread of prevalent data. There is a consensus about the existence of cell-phone addiction, but the delimitation and criteria used by various researchers vary. Cell-phone addiction shows a distinct user profile that differentiates it from Internet addiction. Without evidence pointing to the influence of cultural level and socioeconomic status, the pattern of abuse is greatest among young people, primarily females. Intercultural and geographical differences have not been sufficiently studied. The problematic use of cell phones has been associated with personality variables, such as extraversion, neuroticism, self-esteem, impulsivity, self-identity, and self-image. Similarly, sleep disturbance, anxiety, stress, and, to a lesser extent, depression, which are also associated with Internet abuse, have been associated with problematic cell-phone use. In addition, the present review reveals the coexistence relationship between problematic cell-phone use and substance use such as tobacco and alcohol.

Keywords: addiction; behavioral addiction; cell-phone addiction; dependence; internet addiction.

Publication types

Advertisement

Is Mobile Addiction a Unique Addiction: Findings from an International Sample of University Students

- Original Article

- Published: 12 December 2019

- Volume 18 , pages 1360–1388, ( 2020 )

Cite this article

- Mark Douglas Whitaker 1 &

- Suzana Brown 1

853 Accesses

6 Citations

1 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

This research explores whether addictions around mobile phones should be treated more as a physiological or a psychological problem. A new survey about mobile addiction and time use (MATU), constructed from several studies, tests to what degree time use on mobile phones (a physiological cause) is correlated with four behavioral factors predicting proneness to addiction, respectively one physiological problem and three psychological problems: sensation seeking, impulsiveness, anxiety, and hopelessness. Equally, an index on how strongly students interpret that they have a mobile addiction problem was tested for whether it was correlated to the same four factors. A sample of 1219 students was drawn from four universities, three in the USA and one in South Korea. Correlations between six indexes were analyzed. Students who think they have a “mobile phone time use problem” do not report high (physiological) sensation seeking at all (0.18, p < 0.01) yet have higher correlations only with three psychological problems: impulsiveness (0.64, p < 0.01), hopelessness (0.47, p < 0.01), and anxiety (0.31, p < 0.01). On the other hand, the exact inverse occurs among actual sensation seekers with high time use (0.85, p < 0.01) who lack high correlations with three psychological problems (each below 0.15, p < .01). The pattern held across four different universities and two countries with minimal variations. Mobile addictions appear to be two different types of individualized problems instead of one: physiological problems for some (without major psychological problems) and psychological problems for others (without high time use). This research may help influence policy to target different individual problems in mobile addiction.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Problematic mobile phone use in adolescents: derivation of a short scale mppus-10.

Mobile phone dependence: Secondary school pupils’ attitudes

The prevalence and predictors of problematic mobile phone use: a 14-country empirical survey.

Nonetheless, for those interested in the ancillary question of whether our school-based samples are more or less representative than larger national samples, see Appendix 3.

As noted in Appendix 2, for this sole correlation, different disaggregated meso-level schools fail to show this same result as the full sample: sometimes showing the same lack of statistical significance as the full sample (School D), sometimes weakly positive and statistically significant (School B & C) and sometimes weakly negative and statistically significant (School A). This would seem to indicate varying meso-level issues of school culture or macro-level issues (as School A is the Korean university) equally are important in some way in mobile addiction as well. However, since this study is concerned with only the micro-level of analysis of mobile addiction, and since these micro-level findings are stronger than these meso-level findings in general, the discussion continues to discuss mostly Fig. 1 . Equally noted in Appendix 2 for the micro-level correlations, even disaggregated schools regularly show the same results as the full sample on the four micro-level behavioral factors. This indicates strong micro-level universalities and external validity to the micro-level findings.

Instead of a universal physiological relationship between school problems and mobile phone time use, as noted in disaggregated analysis in Appendix 2’s Table 4 , an intervening variable of a varying school culture (a meso-level correlation) seems to matter for a relatively minor influential relationship developing between school problems and mobile phone time use, instead of this correlation being a physiological universal. Moreover, across the four schools, disaggregated meso-level findings of correlation are mostly always smaller than more regularly stronger micro-level findings of correlation. These findings are seen as complementary factors in mobile addiction instead of opposed to each other.

This may be because some kinds of mobile phone use can be a connecting solace and socially affirming, instead of always escapist. Only a future analysis classifying which particular kinds of “apps” or behaviors on a mobile phone are interpreted by their users as individually escapist or socially affirming can resolve such an issue (Depner 2017 ).

Excluded analysis of a resilience index showed the same result. Contact authors for more information.

The authors will share the MATU survey with other researchers interested in widening the comparative analysis of mobile addition with the same survey instrument whether on these or other points.

Results not included for lack of space.

Akin, A., Altundag, Y., Turan, M., & Akin, U. (2014). The validity and reliability of the Turkish version of the smartphone addiction scale-short form for adolescent. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 152 , 74–77.

Google Scholar

Alexander, B. (2001). The roots of addiction in free market society . Vancouver, Canada: Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives. ( www.policyalternatives.ca )

Alexander, B. (2010). Globalization of addiction: A study in poverty of the spirit . Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5). American Psychiatric Pub.

Andreassen, C. S., Billieux, J., Griffiths, M. D., Kuss, D. J., Demetrovics, Z., Mazzoni, E., & Pallesen, S. (2016). The relationship between addictive use of social media and video games and symptoms of psychiatric disorders: A large-scale cross-sectional study. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 30 ( 2 ), 252–262. https://doi.org/10.1037/adb0000160 .

Article Google Scholar

Andreassen, C. S., Pallesen, S., & Griffiths, M. D. (2017). The relationship between addictive use of social media, narcissism, and self-esteem: Findings from a large national survey. Addictive Behaviors, 64 , 287–293. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2016.03.006 .

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Barratt, E. S., Patton, J., & Stanford, M. (1975). Barratt Impulsiveness Scale . Texas: Barratt-Psychiatry Medical Branch, University of Texas.

Bax, T. (2014). Youth and Internet addiction in China . New York City, NY: Routledge.

Beck, A. T., Weissman, A., Lester, D., & Trexler, L. (1974). The measurement of pessimism: The hopelessness scale. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 42 (6), 861.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Billieux, J., Philippot, P., Schmid, C., Maurage, P., & Mol, J. (2014). Is dysfunctional use of the mobile phone a behavioural addiction? Confronting symptom based versus process-based approaches. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 22 (5), 460–468. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.1910 .

Billieux, J., Maurage, P., Lopez-Fernandez, O., Kuss, D., & Griffiths, M. D. (2015). Can disordered mobile phone use be considered a behavioral addiction? An update on current evidence and a comprehensive model for future research. Current Addiction Reports, 2 (2), 156–162. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40429-015-0054-y .

Boumosleh, J., & Jaalouk, D. (2017). Smartphone addiction among university students and its relationship with academic performance. Global Journal of Health Science, 10 (1), 48–59.

Cain, G. (2014). South Korean teens are so addicted to their smartphones that the government is taking action, The Business Insider , http://www.businessinsider.com/south-korea-concerned-about-smart-phone-usage-2014-4 (Accessed: December 14, 2017)

Ching, S. M., Yee, A., Ramachandran, V., Lim, S. M., Sulaiman, W. A., Foo, Y. L., & KeeHoo, F. (2015). Validation of a Malay Version of the Smartphone Addiction Scale among medical students in Malaysia. PLoS One, 10 (10), e0139337. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0139337 .

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Chiu, S-I. (2014). The relationship between life stress and smartphone addiction on taiwanese university student: A mediation model of learning self-Efficacy and social self-Efficacy. Computers in Human Behavior, 34 , 49-57

Choi, S. W., Kim, D. J., Choi, J. S., Ahn, H., Choi, E. J., Song, W. Y., & Youn, H. (2015). Comparison of risk and protective factors associated with smartphone addiction and Internet addiction. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 4 (4), 308–314.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Chóliz, M., Pinto, L., Phansalkar, S. S., Corr, E., Mujjahid, A., Flores, C., & Barrientos, P. E. (2016). Development of a brief multicultural version of the test of mobile phone dependence (TMDbrief) questionnaire. Frontiers in Psychology, 7 , 650. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00650 .

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Cohen, J. (1992). A power primer. Psychological Bulletin, 112 (1), 155.

Conrod, P. J. (2016). Personality-targeted interventions for substance use and misuse. Current Addiction Reports, 3 , 426–436.

Conrod, P. J., Pihl, R. O., & Vassileva, J. (1998). Differential sensitivity to alcohol reinforcement in groups of men at risk for distinct alcoholism subtypes in Alcoholism. Clinical and Experimental Research, 22 (3), 585–597.

CAS Google Scholar

Conrod, P. J., Stewart, S. H., Pihl, R. O., Côté, S., Fontaine, V., & Dongier, M. (2000). Efficacy of brief coping skills interventions that match different personality profiles of female substance abusers. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 14 (3), 231.

Conrod, P. J., Stewart, S. H., Comeau, N., & Maclean, A. M. (2006). Efficacy of cognitive–behavioral interventions targeting personality risk factors for youth alcohol misuse. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 35 (4), 550–563.

PubMed Google Scholar

Conrod, P. J., Castellanos-Ryan, N., & Strang, J. (2010). Brief, personality-targeted coping skills interventions and survival as a non–drug user over a 2-year period during adolescence. Archives of General Psychiatry, 67 (1), 85–93.

Cortina, J. M. (1993). What is coefficient alpha? An examination of theory and applications. Journal of Applied Psychology, 78 (1), 98.

Costello, A. B., & Osborne, J. W. (2005). Best practices in exploratory factor analysis: Four recommendations for getting the most from your analysis. Practical Assessment, Research, & Evaluation, 10 , 1-9

Courtwright, D. (2002). Forces of habit: Drugs and the making of the modern world . Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

Cronbach, L. J. (1951). Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika, 16 (3), 297–334.

Demirci, K., Orhan, H., Demirdas, A., Akpinar, A., & Sert, H. (2014). Validity and reliability of the Turkish version of the smartphone addiction scale in a younger population. Klinik Psikofarmakoloji Bulteni/Bulletin of Clinical Psychopharmacology, 24 ( 3 ), 226–234. https://doi.org/10.5455/bcp.20140710040824 .

Demirci, K., Akgonul, M., & Akpinar, A. (2015). Relationship of smartphone use severity with sleep quality, depression, and anxiety in university students. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 4 ( 2 ), 85–92. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.4.2015.010 .

Depner, R. A. (2017). In search of wholeness: An exploration of social connection as a mediating factor in addiction. Thesis, Masters of Counseling, City University of Seattle, Vancouver BC, Canada site.

DiClemente, C. C. (2003). Addiction and change: How addictions develop and addicted people recover . New York City: Guilford Press.

Dunckley, Victoria L. (2015). Chapter 1: Electronic screen syndrome: An unrecognized disorder, in Reset Your Child’s Brain: A Four Week Plan to End Meltdowns, Raise Grades, and Boost Social Skills by Reversing the Effects of Electronic Screen Time . Novato, California: New World Library.

Gentile, D. (2009). Pathological video game use among youth 8 to 18: A national study. Psychological Science, 20 (5), 594–602.

George, D. (2001). Preference pollution: How markets create the desires we dislike . University of Michigan Press.

Goodman, A. (1990). Addiction: Definition and implications. British Journal of Addiction, 85 ( 11 ), 1403–1408.

Griffiths, M. (2005). A ‘components’ model of addiction within a biopsychosocial framework. Journal of Substance Use, 10 (4), 191–197.

Griffiths, M. D. (2017). Behavioural addiction and substance addiction should be defined by their similarities not their dissimilarities. Addiction, 112 (10), 1718–1720.

Ha, J. H., Chin, B., Park, D. H., Ryu, S. H., & Yu, J. (2008). Characteristics of excessive cellular phone use in Korean adolescents. Cyberpsychology & Behavior, 11 ( 6 ), 783–784. https://doi.org/10.1089/cpb.2008.0096 .

Hamilton, M. A. X. (1959). The assessment of anxiety states by rating. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 32 (1), 50–55.

Haug, S., Castro, R., Kwon, M., Filler, A., Kowatsch, T., & Schaub, M. (2015). Smartphone use and smartphone addiction among young people in Switzerland. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 4 (4), 299–307. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.4.2015.037 .

Hawi, N., & Samaha, M. (2016). To excel or not to excel: Strong evidence on the adverse effect of smartphone addiction on academic performance. Computers & Education, 98 , 81e89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2016.03.007 .

Hong, F. Y., Chiu, S. I., & Huang, D. H. (2012). A model of the relationship between psychological characteristics, mobile phone addiction and use of mobile phones by Taiwanese university female students. Computers in Human Behavior, 28 (6), 2152-2159.

Im, K. G., Hwang, S. J., Choi, M. A., Seo, N. R., & Byun, J. N. (2013). The correlation between smartphone addiction and psychiatric symptoms in college students. Journal of the Korean Society of School Health, 26 ( 2 ), 124–131.

Jenaro, C., Flores, N., Gómez-Vela, M., González-Gil, F., & Caballo, C. (2007). Problematic internet and cell phone use: Psychological, behavioral, and health correlates. Addiction Research & Theory, 15 (3), 309–320.

Jeong, S. H., Kim, H., Yum, J. Y., & Hwang, Y. (2016). What type of content are smartphone users addicted to? SNS vs. games. Computers in Human Behavior, 54 , 10–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.07.035 .

Jun, S. (2016). The reciprocal longitudinal relationships between mobile phone addiction and depressive symptoms among Korean adolescents. Computers in Human Behavior, 58 , 179–186.

Junco, R., & Cotten, S. R. (2012). No A 4 U: The relationship between multitasking and academic performance. Computers & Education, 59 , 505–514.

Kardaras, N. (2016). Glow kids: How screen addiction is hijacking our kids-and how to break the trance . St. Martin’s Press.

Khoury, J. M., de Freitas, A. A. C., Roque, M. A. V., Albuquerque, M. R., das Neves, M. D. C. L., & Garcia, F. D. (2017). Assessment of the accuracy of a new tool for the screening of smartphone addiction. PLoS One, 12 (5), e0176924. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0176924 .

Kibona, L., & Mgaya, G. (2015). Smartphones’ effects on academic performance of higher learning students. Journal of Multidisciplinary Engineering Science and Technology, 2 (4), 777–784.

Kim D, Lee Y, Lee J, Nam JK. & Chung (2014). Development of Korean Smartphone Addiction Proneness Scale for Korean youth, PLoS One 9(5): e97920. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/jouornal.phone.0097920

Ko, C. H., Liu, G. C., Hsiao, S., Yen, Y. J., Yang, M. J., Lin, W. C., Yen, C. F., & Chen, C. S. (2009). Brain activities associated with gaming urge of online gaming addiction. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 43 (7), 739–747.

Kwon, M., Lee, J. Y., Won, W. Y., Park, J. W., Min, J. A., Hahn, C., & Kim, D. J. (2013). Development and Validation of a Smartphone Addiction Scale (SAS). PLoS One, 8 (2), e56936. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0056936 .

Lee, E. B. (2015). Too much information heavy smartphone and Facebook utilization by African American young adults. Journal of Black Studies, 46 ( 1 ), 44–61. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021934714557034 .

Article CAS Google Scholar

Lee, M. J., Lee, J. S., Kang, M. H., Kim, C. E., Bae, J. N., & Choo, J. S. (2010). Characteristics of cellular phone use and its association with psychological problems among adolescents. Journal of the Korean Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 21 ( 1 ), 31–36. https://doi.org/10.5765/jkacap.2010.21.1.031 .

Lepp, A., Barkley, J. E., & Karpinski, A. C. (2014). The relationship between cell phone use, academic performance, anxiety, and satisfaction with life in college students. Computers in Human Behavior, 31 , 343–350. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2013.10.049 .

Lepp, A., Barkley, J. E., & Karpinski, A. C. (2015) The relationship between cell phone use and academic performance in a sample of U.S. college students, SAGE Open January-March (1):1-9. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244015573169

Lettieri, D., Sayers, M., & Wallenstein, P. H. (Eds.). (1980). Theories on drug abuse: Selected contemporary perspectives, National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) Research Monograph #30, Part of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services . Washington, D. C.: US Gov’t Printing Office.

Leung, L. (2008). Linking psychological attributes to addiction and improper use of the mobile phone among adolescents in Hong Kong. Journal of Children and Media, 2 ( 2 ), 93–113. https://doi.org/10.1080/17482790802078565 .

Lin, Y. H., Chang, L. R., Lee, Y. H., Tseng, H. W., Kuo, T., & Chen, S. (2014). Development and validation of the Smartphone Addiction Inventory (SPAI). PLoS One, 9 ( 6 ), e98312.

Lin, T. T. C., Chiang, Y., & Jiang, Q. (2015). Sociable people beware? Investigating smartphone versus nonsmartphone dependency among young Singaporeans. Social Behavior and Personality, 43 ( 7 ), 1209–1216. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.2015.43.7.1209 .

Lindesmith, A. (1938). A sociological theory of drug addiction. American Journal of Sociology, 43 (4), 593–613. https://doi.org/10.1086/217773 .

Long, J., Liu, T.-Q., Liao, Y. H., Qi, C., He, H. Y., Chen, S. B., & Billieux, J. (2016). Prevalence and correlates of problematic smartphone use in a large random sample of Chinese undergraduates. BMC Psychiatry, 16 ( 1 ), 408. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-016-1083-3 .

Lopez-Fernandez, O., Griffiths, M. D., Kuss, D. J., Dawes, C., Pontes, H. M., Justice, L., Männikkö, N., et al. (2019). Cross-cultural validation of the Compulsive Internet Use Scale in four forms and eight languages. Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking, 22 ( 7 ), 451 – 464 .

Lu, X., Watanabe, J., Liu, Q., Uji, M., Shono, M., & Kitamura, T. (2011). Internet and mobile phone text-messaging dependency: Factor structure and correlation with dysphoric mood among Japanese adults. Computers in Human Behavior, 27 ( 5 ), 1702–1709. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2011.02.009 .

Mak, K. K., Lai, C. M., Watanabe, H., Kim, D. I., Bahar, N., Ramos, M., & Cheng, C. (2014). Epidemiology of internet behaviors and addiction among adolescents in six Asian countries. Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking, 17 (11), 720–728.

Marlatt, G. A., Baer, J. S., Donovan, D. M., & Kivlahan, D. R. (1988). Addictive behaviors: Etiology and treatment. Annual Review of Psychology, 39 (1), 223–252.

Martinotti, G., Villella, C., Di Thiene, D., Di Nicola, M., Bria, P., Conte, G., Cassano, M., Petruccelli, F., Corvasce, N., Janiri, L., & La Torre, G. (2011). Problematic mobile phone use in adolescence: A cross-sectional study. Journal of Public Health, 19 ( 6 ), 545–551. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-011-0422-6 .

McAuliffe, W., & Gordon, R. (1974). A test of Lindesmith’s theory of addiction: The frequency of euphoria among long-term addicts. American Journal of Sociology, 79 (4), 795–840 http://www.jstor.org/stable/2776345 .

Meerkerk, G.-J., Van Den Eijnden, R. J. J. M., Vermulst, A. A., & Garretsen, H. F. L. (2009). The Compulsive Internet Use Scale (CIUS): Some psychometric properties. CyberPsychology and Behavior, 12 ( 1 ), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1089/cpb.2008.0181 .

Muñoz-Miralles, R., Raquel, O.-G., Rosa López-Morón, M., Batalla-Martínez, C., Manresa, J. M., Montellà-Jordana, N., Chamarro, A., Carbonell, X., & Torán-Monserrat, P. (2016). The problematic use of Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) in adolescents by the cross sectional JOITIC study. BMC Pediatrics, 16 , 140. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-016-0674-y .

Park, P. (1985). The supply side of drinking: Alcohol production and consumption in the United States before prohibition, Contemporary Drug Problems 12.

Park, N., & Lee, H. (2012). Social implications of smartphone use: Korean college students’ smartphone use and psychological well-being. Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking, 15 ( 9 ), 491–497. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2011.0580 .

Pinna, F., Dell’Osso, B., Di Nicola, M., Janiri, L., Altamura, A. C., Carpiniello, B., & Hollander, E. (2015). Behavioural addictions and the transition from DSM-IV-TR to DSM-5. J Psychopathol, 21 ( 4 ), 380–389.

Pombo, S., & da Costa, N. F. (2016). Heroin addiction patterns of treatment-seeking patients, 1992-2013: comparison between pre- and post-drug policy reform in Portugal, in. Heroin Addiction: Related Clinical Problems, 18 (6), 51–60.

Sapacz, M., Rockman, G., & Clark, J. (2016). Are we addicted to our cell phones? Computers inHuman Behavior, 57 , 153–159.

Smart, RG. (1980). An availability-proneness theory of illicit drug abuse, in Theories on Drug Abuse: Selected Contemporary Perspectives , National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) Research Monograph #30, part of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (eds., Dan J. Lettieri, Mollie Sayers, Helen Wallenstein Pearson) Washington, D. C.: US Gov’t Printing Office. Pp. 46-49.

Starcevic, V., & Aboujaoude, E. (2016). Internet addiction: Reappraisal of an increasingly inadequate concept. CNS Spectrums, 22 (1), 7–13. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1092852915000863 .

Szasz, T. (2003/1974). Ceremonial chemistry: The ritual persecution of drugs, addicts, and pushers. Syracuse, New York: Syracuse University Press. Reprint.

Tavakolizadeh, J., Atarodi, A., Ahmadpour, S., & Pourgheisar, A. (2014). The prevalence of excessive mobile phone use and its relation with mental health status and demographic factors among the students of Gonabad University of Medical Sciences in 2011-2012. Razavi International Journal of Medicine, 2 ( 1 ), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.5812/rijm.15527 .

Teeson, M. (2002). Theories of addiction: causes and maintenance of addiction. In M. Teeson & L. Degenhardt (Eds.), Addictions: An Introduction . Psychology Press.

Walsh, S. P., White, K. M., & Young, R. M. (2008). Over-connected? A qualitative exploration of the relationship between Australian youth and their mobile phones. Journal of Adolescence, 31 ( 1 ), 77–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2007.04.004 .

Wang, J. L., Jackson, L. A., Zhang, D. J., & Su, Z. Q. (2012). The relationships among the Big Five Personality factors, self-esteem, narcissism, and sensation-seeking to Chinese University students’ uses of social networking sites (SNSs). Computers in Human Behavior, 28 ( 6 ), 2313–2319. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2012.07.001 .

Wang, H., Wang, M., & Wu, S. (2015). Mobile phone addiction symptom profiles related to interpersonal relationship and loneliness for college students: A latent profile analysis. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 23(5), 881-885. Retrieved from http://caod.oriprobe.com/articles/46926496/Mobile_Phone_Addiction_symptom_Profiles_Related_to_Interpersonal_Relat.htm (Accessed: October, 14, 2019)

Weinstein, A., & Lejoyeux, M. (2010). Internet addiction or excessive Internet use. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 36 , 277–283.

Wu, A., Cheung, V., Ku, L., & Hung, W. (2013). Psychological risk factors of addiction to social networking sites among Chinese smartphone users. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 2 ( 3 ), 160–166. https://doi.org/10.1556/JBA.2.2013.006 .

Young, K. S. (1996). Psychology of computer use: XL. Addictive use of the Internet: A case that breaks the stereotype. Psychological Reports, 79 (3), 899–902.

Young, K. S. (2004). Internet addiction: A new clinical phenomenon and its consequences. American Behavioral Scientist, 48 (4), 402–415.

Young, E. (2017). Iceland knows how to stop teen substance abuse but the rest of the world isn’t listening, Mosaic: The Science of Life https://mosaicscience.com/story/iceland-prevent-teensubstance-abuse (Accessed: December 22, 2017); Published by the Welcome Charitable Trust ( https://wellcome.ac.uk/ ).

Zuckerman, M., Kolin, E. A., Price, L., & Zoob, I. (1964). Development of a sensation-seeking scale. Journal of Consulting Psychology, 28 (6), 477.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Technology and Society, Stony Brook University, SUNY Korea, Incheon, Incheon Global Campus, B310, 119 SongdoMoonhwa-Ro, Yeonsu-gu, 406-840, South Korea

Mark Douglas Whitaker & Suzana Brown

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Mark Douglas Whitaker .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest. No external funding was used in the creation of the Mobile Addiction and Time Use Survey (MATU) or ongoing data analysis.

The necessary ethical permissions were received from the Institutional Review Board at all four universities. Before completing the survey, participants were informed about the study protocol and gave their consent electronically.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in this study involving human participants were approved by and in accordance with the ethical standards of Institutional Research Review Boards of the four universities involved and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix 1. Indices in the analysis based on questions from the survey on mobile addiction and time use (MATU)

In all indices, an asterisk on the question (*) indicates a reverse-coded question.

Index 1: School outcomes regarding mobile phone use

My school grades dropped because I use my mobile phone excessively.

I have a hard time finishing things because of using my mobile phone.

When I use my mobile phone, I think I would be more productive if I did not use it so much.

When I use my mobile phone, I feel I should be concentrating on study/work instead.

My mobile phone does not distract me from my studies.*

Index 2: Time use of mobile phones

Texting on mobile phones and on apps with chat options

Taking selfies or self-videos

Using a mobile phone for emails

Using a mobile phone for games

Using a mobile phone for social media, SNS, or community

Using a mobile phone for entertainment, TV, videos, audio, or radio

Using a mobile phone for shopping and consumer services (includes paying bills)

Using a mobile phone for web browsing

Using a mobile phone for learning and education

Using a mobile phone for daily personal appointments and contact information

Using mobile phone for ongoing coordination with groups for events and meetings

Index 3: Sensation seeking connected to mobile phone use

Using a mobile phone for shopping and consumer services

It passes the time when I am bored.

I use it when I have to wait for someone or something rather than do nothing.

Index 4: Impulsiveness connected to mobile phone use

Friends and acquaintances comment on my excessive use of mobile phone.

Family members complain that I use my mobile phone too much.

When I use my mobile phone, family members get angry.

People are offended that I’m not paying attention when I’m on my mobile phone.

Index 5: Anxiety connected to mobile phone use

I can’t imagine life without my mobile phone.

It would be painful for me if I couldn’t use my mobile phone.

I get anxious when I am without my mobile phone.

I panic when I can’t use my mobile phone.

It would be impossible for me to give up my mobile phone.

Index 6: Hopelessness associated with mobile phone use

How often do you feel sad?

How often do you avoid dealing with problems in your life?

How often do you feel hopeful about the future?*

When I can’t use my mobile phone, I feel like I have lost an entire world.

Using my mobile phone allows me to escape an unpleasant aspect of my life for a while.

When I use my mobile phone, I feel bad but I can’t stop using it.

Have you ever felt bad or guilty about your mobile phone usage?

Have people annoyed you by criticizing your mobile phone usage?

My whole personal and social life depends on my phone.

Using my mobile phone is more enjoyable than spending time with my family.

Using my mobile phone is more enjoyable than spending time with my friends.

Appendix 2. Disaggregated analysis of the six indices and the four schools show a lack of bias from any of the four schools in the sample and a lack of bias in the results as well

There were two potential problems identified, and both resolved, since either difference in respondent rates across all four schools or demographics of one school itself could skew the whole sample, the creation of the indices, and the results from the whole sample. Therefore before the main analysis, it was important first to validate that the aggregate sample lacks skew and is thus a legitimate basis to construct the analysis. Equally, it was important to provide evidence the indices are legitimate bases upon which to construct such analysis. Therefore, the same six indices were tested using the discrete school samples themselves via EFA and Cronbach’s alpha, and these results were compared to the results from the full sample on these two measures. It was reassuring that both these two potential problems of sample size differences and skewed index construction can be rejected. In comparing these disaggregated four samples’ index statistics to the full samples’ index statistics, all these indices’ statistics showed consistency in EFA Footnote 7 and in Cronbach’s alpha when compared to the full sample as shown in Table 3 .

Both tests upon the indices (Table 3 ) and the data findings (Table 4 ) indicated no school is a major outlier skewing the formation of the indices or the analysis in one way or another. For ease of comparison, Table 3 repeats Cronbach’s alpha for each of the six derived indexes using the full four-school sample ( n = 1219) from Table 2 , while presenting an additional 24 separate tests of Cronbach’s alpha for each of the six derived indexes for each of the four schools sampled, showing the major pattern is consistency across all four schools. This test of Cronbach’s alpha upon the disaggregated samples of data indicated all six indices are consistent across different schools in this sample. In addition, no single school in all six indices is an outlier skewing the indices or the later analysis, since noticeably either 3 of 4 schools or 4 of 4 schools in all rows all had generally the same Cronbach’s alpha for each index. Out of 24 tests, only School A in one index had a slightly lower Cronbach’s alpha than all the other 23 tests. Any Cronbach’s alpha above 0.7 is considered reasonable, and the single example of 0.58 is at a level considered only questionable, instead of doubtful. In short, the idea of a bias and skewing from uneven sampling and from particular school subsamples was rejected.

However, after assuring the lack of skew of any one particular school on the six indices, a similar question arises if any schools’ discrete samples themselves show different analytic results than the eight correlations in Fig. 1 and thus were potentially another source of bias and skew in the full sample. Therefore, in Table 4 below, a further test of pairwise correlation upon the disaggregated samples of data shows the same nine correlations as in Fig. 1 . It was found that all four disaggregated school samples have generally the same scored consistencies as the full sample even across these four widely different schools. As before, no single school in all indices is an outlier skewing the micro-level analysis since (once more) either 3 of 4 schools or 4 of 4 schools all had generally the same correlations or patterns for each index. For the micro-level analysis, out of 32 additional correlation tests in Table 4 , only 5 differences are observed. For School A, one index was without statistical significance between school problems and sensation seeking. School A had three other indices without statistical significance between raw actual time use and impulsiveness, anxiety, or hopelessness, and School C was the same between raw actual time use and impulsiveness. For the latter four, it will be shown that these lacks of statistical significance in only these four discrete areas (while holding to very high statistical significance in all other 28 areas) actually makes the unique bimodal argument in the main discussion about mobile addiction stronger rather than weaker by foreshadowing a stronger case about a lack of strong correlation between raw mobile phone time use and many behavioral problems.

In short, both tests of Cronbach’s alpha on the indices for individual schools and the tests of pairwise correlations on the relationships between the indices for individual schools in the results indicated no single school in all indices is a major outlier skewing results of the overall analysis. In Tables 3 and 4 , it is intriguing that the same comparative statistical patterns or ratios hold across all four schools’ discrete samples and internationally. In addition, Table 4 shows both internal validity of the indices as well as somewhat an external validity in the analysis since all four samples generally have the same patterns of mobile addiction. In conclusion to this Appendix, we tested and confirmed both the internal validity of the indices and the external validity of the results by showing four separate samples had generally the same indices and analysis results as the full sample.

Appendix 3. Distributions for the six indices based on the full sample ( n = 1219)

In Fig. 2 below, compared with two different national findings (Korea and US) or Korean-municipal findings (Cain 2014 ; Gentile 2009 ), our sample lacks any unrepresentative larger or smaller scale of extreme internet/mobile addictions. First, if around 4% of the wider population of Seoul was found to be extreme mobile addicts in terms of time use (Cain, 2005), this is comparable to the below distribution for time use (Index 2) in our international sample. Equally, given a rare national US sample judging youth on a similar internet gaming addiction, 8.5% were found to be in the most extreme category of internet gaming addicts (Gentile 2009 ). This is hardly different than similar measures of sensation seeking or impulsive behavior extremes in our international sample (below, Index 3 and 4). However, it has to be said that to our defense, our sample was not designed to answer questions about national prevalence of addiction or whether our sample was representative or not compared to a national study on our hypotheses (since such a national study on our hypotheses have yet to be done, so no comparisons are possible yet). Our sampled higher educational youth population is the one best chosen to fit the two literatures drawn upon that use the same demographics (about mobile phone influenced school outcomes, and about proneness to addictive behavior employed in Conrod’s research) that allow more legitimately used questions or conceptual ideas adapted from these literatures and allow comparisons there.

Distributions for the six indices based on the full sample ( n = 1219)

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Whitaker, M.D., Brown, S. Is Mobile Addiction a Unique Addiction: Findings from an International Sample of University Students. Int J Ment Health Addiction 18 , 1360–1388 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-019-00155-5

Download citation

Published : 12 December 2019

Issue Date : October 2020

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-019-00155-5

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Psychological

- Physiological

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 11 September 2020

The relationship of smartphone addiction with psychological distress and neuroticism among university medical students

- Leonard Yik-Chuan Lei 1 ,

- Muhd Al-Aarifin Ismail ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5117-0489 1 ,

- Jamilah Al-Muhammady Mohammad 1 &

- Muhamad Saiful Bahri Yusoff 1

BMC Psychology volume 8 , Article number: 97 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

28k Accesses

41 Citations

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

Smartphone plays a vital role in higher education as it serves as a device with multiple functions. Smartphone addiction was reported on the rise among college and university students. The addiction may result in unwanted consequences on their academic performance and psychological health. One factor that consistently relates to psychological distress and smartphone addiction is the neurotic personality trait. This study explored the relationship of smartphone addiction with psychological health and neuroticism among USM medical students.

A cross-sectional study was carried out on medical students in a public medical school. DASS-21, the neuroticism-subscale of USMaP-i and SAS-SV were administered to measure psychological distress, neuroticism, and smartphone addiction of the medical students. Spearman correlation was performed to examine the correlation between smartphone addiction with psychological distress and neuroticism. Simple linear regression was performed to investigate relationship factors of smartphone addiction.

A total of 574 medical students participated in this study. The prevalence of smartphone addiction was 40.6%. It was higher among male (49.2%) compared to female (36.6%) medical students. The result showed a fair positive correlation between smartphone addiction and psychological health (rdepression = 0.277, p -value < 0.001; ranxiety = 0.312, p-value < 0.001; rstress = 0.329, p-value < 0.001). However, there was a poor positive correlation between smartphone addiction and neuroticism (r = 0.173, p -value < 0.001). The simple linear regression showed a significant increase in the levels of depression, anxiety, stress and neuroticism upon one unit increase in smartphone addiction (bdepression = 0.101, p -value < 0.001; banxiety = 0.120, p-value < 0.001; bstress = 0.132, p-value < 0.001; bneuroticism = 0.404, p-value < 0.05). These results indicated significant relationships between smartphone addiction, psychological health and neuroticism.

This study suggested a high prevalence of smartphone addiction among medical students, particularly in male medical students. The smartphone addiction might lead to psychological problems and the most vulnerable group is the medical student with the neurotic personality trait.

Peer Review reports

Smartphones possess the means to enrich learning activities from medical education in undergraduate and postgraduate training [ 1 ]. For example, smartphones are used in the pursuit of finding solutions to patient care, improving lifelong medical education, and professional partners through the use of social media [ 2 ]. With the advent of smartphones, its uses in higher education cannot be ignored and need to be examined to explore the consequences of its application. Smartphones can be defined as a hand-held device built as a mobile computing platform with advanced computing ability and connectivity. It serves to combine the functions of portable media players, low-end compact digital cameras, pocket video cameras, and GPS navigation units [ 3 ]. Furthermore, smartphones are being used for more than just a phone but rather a device that provides multiple functions including surfing the internet, email, navigation, social networking, and games [ 4 ].

Smartphones are gaining increasing importance in health care and researchers and developers are enticed with their applications related to health [ 5 ]. These devices have multiple features that can be positively employed which include speedy access to information, enhanced organization, and instantaneous communication [ 6 ] and can with certainty be used to enhance education [ 7 ]. However, smartphone addiction is a vital issue in the global population with problems comprising physical difficulties like muscular pain and eye illnesses, and psychological difficulties such as auditory and tactile delusion [ 8 ].

The use of smartphones reached figures over 50% in the majority of developed countries [ 9 ]. Malaysian Communications and Multimedia Commission (MCMC) has reported that in Malaysia, 24.5 million users have access to the internet in 2016 [ 10 ]. Smartphone stays as the most popular gadget for users to enter the internet (89.4%) creating a mobile-oriented country [ 10 ]. Over the past several years, there has been an increasing amount of studies that explored smartphone addiction [ 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 ]. The bulk of these studies focused on smartphone addiction and its potential influences on individuals [ 15 ]. On top of that, among Malaysian medical schools, two studies showed the prevalence of at-risk cases of developing smartphone addiction: 46.9% in Universiti Putra Malaysia (UPM) [ 16 ] and 52.2% in Universiti Teknologi MARA (UiTM) [ 17 ]. Several studies have reported a high prevalence of smartphone addiction: the prevalence of smartphone addiction in a Malaysian medical school was 46.9% [ 16 ], Saudi Arabian university students was 48% [ 18 ], Saudi Arabian dental students was 71.9% [ 19 ] and Indian medical students was 85.4% [ 20 ]. Conversely, some studies have reported a low prevalence of smartphone addiction: the prevalence of smartphone addiction in Chinese medical college students was 29.8% [ 4 ], Saudi Arabian students was 33.2% [ 21 ] and Saudi Arabian medical students was 36.5% [ 22 ]. These results suggested more than a quarter of students in higher education experienced smartphone addiction that requires further exploration of possible factors contributing to it as well as its consequences on students’ wellbeing.

Previous studies have shown links between smartphone addiction and depression [ 23 , 24 , 25 ], smartphone addiction and anxiety [ 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 ], smartphone addiction and stress [ 11 , 30 ], smartphone addiction and neuroticism [ 27 , 31 ]. However, these studies are in the general population and university students. Our study is looking at the specific population of medical students in a public medical school. Also, to the best of our knowledge, there are no studies in medical students that links smartphone addiction, psychological distress, and neurotic traits. Medical students use smartphones to facilitate retrieving information resources [ 32 , 33 , 34 ]. There is almost universal ownership of smartphones among medical students [ 35 ]. The applications on smartphones in medical education have reported to increase student involvement, improve the feedback process, and enhance communication between student and teacher [ 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 ]. Instant messaging smartphone applications such as WhatsApp can be used as a method to facilitate communication and education among groups of medical students [ 40 ]. It is important to know the effect of the increased use of smartphones in relation to psychological distress among medical students.

The study of smartphone addiction among medical students become vital as it enlightens us on smartphone usage. In Malaysia, there have been numerous studies on smartphone addiction [ 41 , 42 ]. However, there are not many studies done on smartphone addiction and its effects on medical undergraduates. Individuals measured with the personality trait that is high in neuroticism may be predisposed to addiction and behavioural problems [ 43 ]. Thus, we also decided to include the personality trait neuroticism as it is linked to addiction [ 44 , 45 ], and we are interested in studying the relationship between neuroticism and smartphone addiction. Neuroticism is present among medical students [ 46 ]. Medical students with neurotic tendencies behave negatively to academic stress, and this becomes a contributing factor to low academic performance [ 46 ]. Students with neuroticism are more vulnerable to smartphone addiction which can lead to psychological distress. The current research may play a role in developing intervention measures such as behavioral therapies and counseling. It also may serve to help medical students improve their awareness of their emotionality and its effect on smartphone use. Therefore, the primary focus of this study is to investigate the relationship of smartphone addiction with psychological distress and neuroticism among medical students.

Research hypothesis

The prevalence of smartphone addiction among USM medical students is more than 40%.

There is a significant correlation between smartphone addiction and depression among USM medical students.

There is a significant correlation between smartphone addiction and anxiety among USM medical students.

There is a significant correlation between smartphone addiction and stress among USM medical students.

There is a significant correlation between smartphone addiction and neuroticism among USM medical students.

Depression, anxiety, stress, and neuroticism significantly predict the smartphone addiction level.

Study sample

A cross-sectional study was carried out on year 1 to year 5 medical students in a public medical school in Malaysia. Before handing out the questionnaires, all students were informed about the study and their participation was voluntary. An informed consent to participate and publication was obtained from all participants. Bias was not explored in this study.

Sampling method and calculation

The sample size was determined by the single proportion size formula. The initial sample size calculation was based on a pilot study that involved students and staff [ 17 ] and the largest sample size needed was 384. After taking into account, 30% drop-out rate, the total number of sample size was 384/ (1–0.3) = 548. All medical students were included, those who did not sign the consent form were excluded from the study.

Data collection tools

There were three psychometric instruments used in this study; 1) Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS-21); 2) modified USM Personality Inventory (USMaP-i); and 3) Smartphone Addiction Scale – Short Version (SAS-SV).

The DASS instrument was first introduced by Lovibond and Lovibond (1995) and delivered a self-reporting measure, which was created to evaluate the features associated to anxiety, stress, and depression. For each DASS-21 subscale, the score must be multiplied by two to simulate the DASS-42 version: the range of score from 0 to 42. A high score in each subscale is equal to a high degree of symptoms [ 47 ]. In a validation study done, the internal consistency of each subscale was high ranging from 0.70 for the stress sub-scale to 0.88 for the overall scale. The scores on each of the three subscales and the combinations of two or three of them were able to identify mental disorders of depression and anxiety in women with a sensitivity of 79.1% and a specificity of 77% at the optimal cut off of > 33 [ 23 ].

Modified USMaP-i

The USM Personality Inventory was created to measure the Big-Five Personality traits and is identified to be a reliable and valid instrument to evaluate the personality traits of prospective medical students [ 48 ]. This inventory was created explicitly to identify personal traits of Malaysian candidates who seek to apply to the medical course in USM [ 48 ]. The 15-item version of USMaP-i showed an acceptable level of internal consistency with each personality domain ranged from 0.64 and 0.84 as reported on the International Personality Item Pool Website [ 49 ]. We selected the 3 items that represent neuroticism to assess the neuroticism personality trait. Neuroticism is usually associated with features like depression, distress, anxiety, moodiness, poor coping ability, and sadness [ 50 ]. The total Cronbach alpha for the neuroticism subscale for USMaP-I is 0.722 [ 26 , 49 ].

The smartphone addiction scale was first developed and validated by Kwon, Lee et al. (2013) as a way to evaluate smartphone addiction in teenagers. This scale has shown to be validated with high psychometric sound properties in various countries [ 3 , 12 , 16 , 27 , 51 ]. The Smartphone Addiction Scale - Short Version (SAS-SV) is a validated scale that consists of ten items in the questionnaire that are used to measure the levels of smartphone addiction [ 3 ]. The total score is from 10 to 60. The coefficient for Cronbach alpha correlation obtained is 0.91 for Smartphone Addiction Short Version [ 3 ]. The strength of SAS-SV is that it can be used to discern a potentially high-risk group for smartphone addiction, both in the educational field and community [ 3 ]. The cut-off point for significant smartphone addiction for male is 31 and female is 33 based on the recommendation by Kwon et al. (2013).

Data collection

Data collection was performed via a self-guided questionnaire. Individuals were screened for one inclusion criteria and one exclusion criteria. Individuals who were medical students were eligible to participate (inclusion criteria). Individuals who were not willing to participate were not included in the study (exclusion criteria). Participants who submitted incomplete responses were excluded from this study.

Ethical consideration

Ethical clearance was obtained from the Human Research Ethics Committee of USM (JEPeM) with study protocol code (USM/JEPeM/18070352). Signed consents were taken from medical students. Instructions and information about this study were given to them. Each medical student was given an ID for tracing and profiling purposes. They were informed that the results of this study will not affect their academic results in any way. The questionnaires were distributed to all medical students after lecture sessions.

Statistical analysis

The data was analyzed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 24. Spearman correlation and simple linear regression tests were performed to examine the relationships of smartphone addiction with psychological distress and neuroticism. To accurately represent the relationship of smartphone addiction and neuroticism, the items in the modified USMaP-i were recoded due to negative items present in the neuroticism subscale: (Question 6 + Question 10 + Question 14). In the regression analysis, depression, anxiety, stress and neuroticism are independent variables and smartphone addiction is the dependent variable. A single regression analysis is used to account for the effects of multicollinearity because the correlation coefficient values of stress, depression, anxiety and neurotic tendencies are large. This research was not designed to investigate the gender differences and its correlations with depression, anxiety, stress and neuroticism. Further gender issues are not within the scope of this study.

Response rate

The survey’s response rate was 83.9% (574 out of 674). There was a higher proportion of female medical students (68.5%) than male medical students (31.5%). Malay students were the majority (65.3%) followed by Chinese (16%), Indian (15.5%) and other races (3.1%). The majority of students were between 19 and 23 years old. The proportion of students in each year of study was more or less similar or equal in numbers. Medical students that did not participate in the survey for reasons of lack of interest, time constraints, and fatigue.

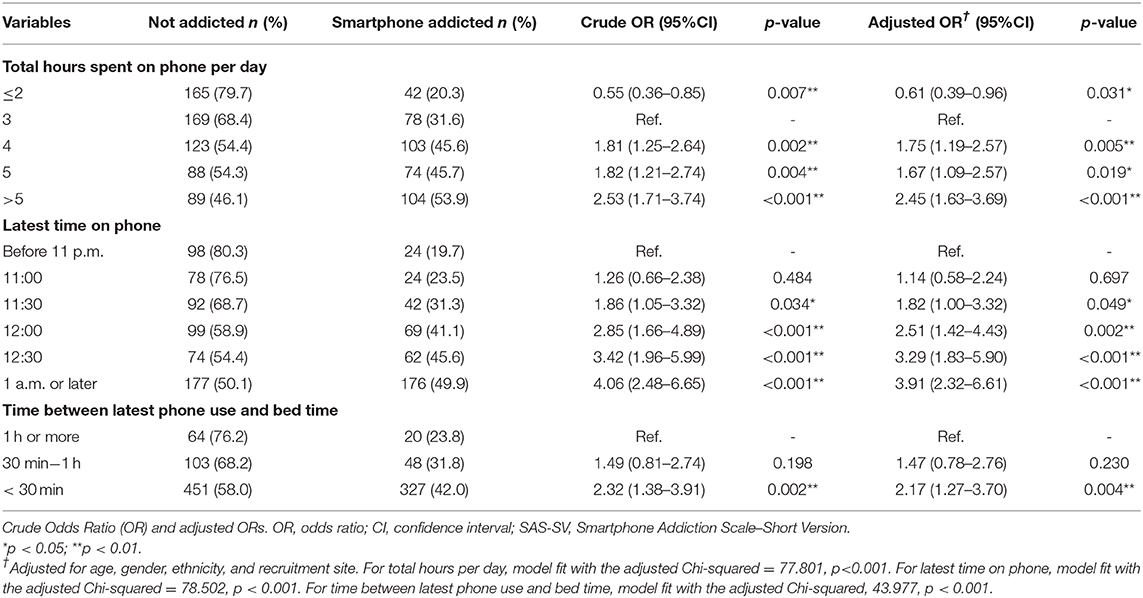

In this study, the prevalence of smartphone addiction found was 40.6%. There is a higher prevalence of male students addicted to smartphone (49.2%) compared to the female students (36.6%). The results of this analysis can be seen in Table 1 .

Correlation of smartphone addiction, psychological distress and neuroticism

The correlation analysis for smartphone addiction with psychological health and neuroticism is shown in Table 2 . The result showed a fair positive correlation between smartphone addiction and psychological health among USM medical students (rdepression = 0.277, p -value < 0.001; ranxiety = 0.312, p-value < 0.001; rstress = 0.329, p-value < 0.001). However, there was a poor positive correlation between smartphone addiction and neuroticism (r = 0.173, p -value < 0.001).

Assumption was not met as normality of distribution was violated.

Linear regression of smartphone addiction, psychological distress and neuroticism

The regression analysis for smartphone addiction with psychological health and neuroticism is shown in Table 3 . The simple linear regression study showed a significant increase in depression, anxiety, stress and neuroticism levels upon one unit increase in smartphone addiction (bdepression = 0.101, p -value < 0.001; banxiety = 0.120, p-value < 0.001; bstress = 0.132, p -value < 0.001; bneuroticism = 0.404, p-value < 0.05). These results indicated significant relationships between smartphone addiction, psychological health and neuroticism. Smartphone addiction is a significant relationship factor of depression, anxiety and stress, while neuroticism is a significant relationship factor of smartphone addiction.

Prevalence of smartphone addiction

The prevalence of smartphone addiction among USM medical students was 40.6%; hypothesis 1 assumes the prevalence of smartphone addiction among USM medical students is more than 40%. This study reported that there is a higher prevalence of smartphone addiction among male medical students compared to female medical students, which is similar to a few other studies [ 4 , 52 , 53 ]. Other studies found a higher prevalence of smartphone addiction in females compared to males [ 3 , 12 , 22 , 54 , 55 ]. Interestingly, previous studies [ 24 , 25 ] did not report that gender is associated with smartphone addiction. The high prevalence of smartphone addiction (40.6%) in this study may be explained by smartphones becoming the main communication device among Malaysians and elsewhere. The percentage of smartphone consumers gradually rose from 68.7% in 2016 to 75.9% in 2017 [ 10 ]. Another observation is that medical students are using smartphones for social media messaging services such as WhatsApp and WeChat for communication purposes as well as for their studies, hence smartphones are becoming a vital tool in personal and professional life [ 56 ]. A study reported that WhatsApp assisted in easy learning and provided a way for clear communication of knowledge in shorter periods [ 57 ]. The higher prevalence of smartphone addiction in male medical students may be due to male medical students using their smartphone more for their entertainment such as online games while females use their smartphones for social interactions [ 58 , 59 , 60 ].

Relationship between smartphone addiction and depression

This study found a significant and fair positive correlation (r = 0.277) between smartphone addiction and depression, as in research hypothesis 2. Likewise, previous studies among adults reported a strong positive correlation between smartphone addiction and depression [ 28 ]. Other findings further support the fact that high levels of smartphone addiction were correlated with depression [ 29 ]. In the Malaysian context, a study among university students showed students who had high scores of smartphone addiction reported high scores of depression [ 61 ] that suggests a relationship between smartphone addiction and depression. Another study found that the group with high smartphone use showed greater levels of depression compared to the low smartphone use group among university students in Turkey [ 12 ]. However, other studies have found no relationship between smartphone addiction and depression [ 62 ]. These facts consistently suggested a positive correlation between smartphone addiction and depression.

The regression analysis showed the increase of smartphone addiction scores leads to the increase of depression scores, indicating it is a relationship factor. These results are similar to previous findings, in which smartphone addiction was reported to be found as a predictor of depression for undergraduates in a local Malaysian university [ 61 ]. Another study also supports this finding, in which it reported the severity of smartphone use predicted depression [ 12 ]. Conversely, previous studies reported vice-versa whereby depression predicted smartphone addiction among university students [ 25 , 30 , 63 ]. These facts suggested that smartphone uses among university students should be considered as high-risk behaviour that negatively affects their psychological health. There are several possible explanations for our results. Individuals with mood disorders are more prone to become a smartphone addict [ 64 ]. Lemola et.al (2015) reported that using electronic media at night is associated with sleep disturbances and depressive symptoms. One study stated that individuals with lower levels of self-perceived health conditions and emotions tended to display an excessive use of smartphones [ 65 ]. This suggested that individuals were in a constant cycle of attempting to compensate for their perceived health status, without being fully aware that smartphone addiction has undesirable implications to their physical, emotional, and social well-being.

The relationship between smartphone addiction and depression is evident in this study and shows that medical students that have smartphone addiction are at risk of having depression. Medical students displaying high levels of smartphone addiction and depression should be observed and given help if necessary. This can be done by promoting the responsible usage of smartphone use among medical students in activities. Sensible usage of smartphones is suggested, especially on younger adults who could be at greater risk of depression [ 28 ].

Relationship between smartphone addiction and anxiety

The results of our study indicate that there was a fair positive correlation between (r = 0.312) smartphone addiction and anxiety, as in research hypothesis 3. Demirci et, al. (2015) has found that smartphone use severity was positively correlated with anxiety and that corresponds with the findings in our study. Several other studies describe smartphone addictions are reported to increase with anxiety levels [ 54 , 55 , 66 , 67 ].

Our regression analysis revealed that increased smartphone addiction scores are a significant relationship factor in increased anxiety scores. Demirci et, al. (2015) reported that smartphone use severity predicted anxiety and it is consistent with our findings. A study reported that smartphone addiction was reported to be found as a predictor of anxiety in Malaysian undergraduate students [ 61 ]. In contrast, previous studies reported that anxiety significantly predicted smartphone addiction [ 25 , 31 , 63 ].

A possible explanation for our results is medical students may habitually check their smartphones in the likelihood of reducing their anxiety by receiving assurance through messages from their friends. The pattern of an individual checking his or her phone and receiving notifications also function in getting social reassurance behaviour from friends [ 68 ]. This behaviour of seeking reassurance can generally include symptoms of loneliness, depression, and anxiety that is the driving factor for reassurance seeking [ 68 ].

Relationship between smartphone addiction and stress

The results of this study indicate that there was a fair positive correlation between (r = 0.329) smartphone addiction and stress, as in research hypothesis 4. In another important finding, Samaha et, al. (2016) show the results between the risk of smartphone and perceived stress, reporting a slight positive correlation with an elevated risk of smartphone addiction associated with elevated levels of perceived stress which supports our study. Previous studies reported that stress leads to smartphone use [ 56 , 69 ], while another study proposes that smartphone use may cause stress [ 70 ]. In our regression analysis, increased smartphone addiction scores are a significant relationship factor in increased stress scores. Conversely, in a sample of Taiwanese university students reported a positive predictive effect of family and emotional stresses on smartphone addiction [ 11 ].

There are several explanations for the study results. Medical students are under stressful medical training [ 71 ], therefore they are prone to being under stress which in turn lowers self-control which may increase their chances of smartphone addiction. Smartphone addiction is influenced by self-control [ 72 ]. Self-control is defined as the capacity to alter one’s responses, such as overriding some impulses to bring behavior in line with goals and standards [ 73 ]. According to Cho et, al. (2017), an increase in stress degree results in a lowered self-control ability, and reduction in self-control further increases the chances of smartphone addiction.

Relationship between smartphone addiction and neuroticism

In this study, the results indicate that there is a poor positive correlation between (r = 0.173) smartphone addiction and neuroticism, as in research hypothesis 5. Neuroticism was reported to be significantly related to excessive use of smartphones [ 55 ] and corresponded with the findings of our study. These results are similar to other study findings reported that individuals who possessed high levels of neuroticism also report a high level of smartphone addiction [ 74 ]. In another study, neuroticism predicts problematic smartphone use [ 75 ]. However, the study [ 76 ] did not report a significant relationship between neuroticism and problematic phone use. In our regression analysis, increased neuroticism scores are a significant relationship factor in increased smartphone addiction scores. It was found neurotic personality increased the degree of smartphone addiction [ 55 ]. Problematic mobile use is positively associated with neuroticism [ 77 ]. There are several explanations for this result, medical students may be more vulnerable to smartphone addiction. The neuroticism trait has been linked to smartphone addiction [ 78 , 79 ]. A study stated that neuroticism is associated with a chain-mediating effect with smartphone addiction and depression, all vital variables that deteriorate the quality of life [ 80 ]. Apart from that, another study showed that there is a positive relationship between neuroticism and smartphone use while driving [ 81 ]. Another possible explanation is that medical students with neuroticism may depend on their smartphones to get reassurance from their friends. Individuals with high neuroticism tend to use their smartphones to get emotional and social reassurance from their relationships [ 82 ].

Implications and future research

Depression, anxiety, stress and neuroticism significantly predict smartphone addiction level, as in research hypothesis 6. The results show that there is a high prevalence of smartphone addiction among medical students. This means that a large proportion of students are affected by smartphone over usage and suggests a widespread occurrence that needs to be addressed by all relevant parties. It raises a deep concern because academic performances may be affected by a large number of medical students with smartphone addiction. As a consequence of smartphone addiction, individuals with smartphone addiction might meet with difficulties such as interpersonal adjustments, managing time, and academic performance [ 83 ]. This might affect the performance of the medical school as a whole in terms of academic results. The high prevalence of smartphone addiction in this study shows that they are at risk to have problems. Medical students displaying high levels of smartphone addiction should be monitored and given further help. Prevention is better than cure, thus smartphone addiction among medical students is recommended for early detection so that appropriate interventions can be planned accordingly. We also have to take into account the high prevalence of male medical students. Several approaches can be suggested to medical students who require further help for smartphone addiction; namely cognitive-behavioral approach, motivational interviewing, and behavioural cognitive treatment [ 84 ]. The implications for the intervention from the results of the study are to provide a baseline for research incorporating approaches tailored for medical students with smartphone addiction. This should address the most vulnerable group of students with the neuroticism personality trait.

Limitations and future research

Considering limited undergraduate smartphone addiction studies in the local setting, the results reported in this study provide insights into the professional health care team. It should be noted that smartphone usage is culturally bound experience and will contrast across countries with varying degrees of technology availability and advances in that region. This study does not report cause and effect relationships. Confounding variables were not studied. For example, in the curriculum at the medical school, each student has to go through e-learning (teaching and learning activities) and assessment that requires smartphone use. This suggests that in reality the medical students may be tasked with activities that require them to use their smartphones for education purposes, i.e. hours spent on smartphones for assignments and lectures. Further research can build upon our findings and investigate screening and interventions for smartphone addiction among medical students.

Conclusions

This study found the prevalence of smartphone addiction among medical students was high, particularly in male medical students. The smartphone addiction might lead to psychological problems and the most vulnerable group was students with the neuroticism personality trait. Thus, there is a need to create and implement programs to promote healthy smartphone usage to minimize the impact of smartphone addiction on psychological health. By doing so, one may implement effective intervention and prevention strategies to groups of students with smartphone addiction. We believe that with a proper guidance; students may be able to use their smartphones more responsibly.

Availability of data and materials

Data generated and analysed during the current study are not publicly available as individual privacy could be comprised; however, may be available from the corresponding author on reasonable request and with the permission of the medical school.

Abbreviations

Depression Anxiety Stress Scale

Human Research Ethics Committee of University Sains Malaysia

Malaysian Communication and Multimedia Commission

Smartphone Addiction Scale Short Version

School of Medical Sciences

Universiti Teknologi MARA

Universiti Putra Malaysia

Universiti Sains Malaysia

iUniversiti Sains Malaysia Personality Inventory

Masters K, Ellaway RH, Topps D, Archibald D, Hogue RJ. Mobile technologies in medical education: AMEE guide no. 105. Med Teach. 2016;38(6):537–49.

PubMed Google Scholar

Joshi N, Lin M. The smartphone: how it is transforming medical education, patient care, and professional collaboration. African J Emergency Med. 2013;4(3):152–4.

Google Scholar

Kwon M, Kim D-J, Cho H, Yang S. The smartphone addiction scale: development and validation of a short version for adolescents. PLoS One. 2013;8(12):e83558.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Chen B, Liu F, Ding S, Ying X, Wang L, Wen Y. Gender differences in factors associated with smartphone addiction: a cross-sectional study among medical college students. BMC Psychiatry. 2017;17(1):341.

Sandholzer M, Deutsch T, Frese T, Winter A. Predictors of students’ self-reported adoption of a smartphone application for medical education in general practice. BMC Med Educ. 2015;15(1):91.

Robinson T, Cronin T, Ibrahim H, Jinks M, Molitor T, Newman J, et al. Smartphone use and acceptability among clinical medical students: a questionnaire-based study. J Med Syst. 2013;37(3):9936.

Almunawar MN, Anshari M, Susanto H, Chen CK. Revealing customer behavior on smartphones. Int J Asian Business Information Manage (IJABIM). 2015;6(2):33–49.

De-Sola J, Talledo H, Rubio G, de Fonseca FR. Development of a mobile phone addiction craving scale and its validation in a Spanish adult population. Front Psych. 2017;8:90.

Van Deursen AJ, Bolle CL, Hegner SM, Kommers PA. Modeling habitual and addictive smartphone behavior: the role of smartphone usage types, emotional intelligence, social stress, self-regulation, age, and gender. Comput Hum Behav. 2015;45:411–20.

Malaysian Communications And Multimedia Comission. Hand phone users Survery 2017; 2017. Available from: https://www.mcmc.gov.my/skmmgovmy/media/General/pdf/HPUS2017.pdf .

Chiu S-I. The relationship between life stress and smartphone addiction on Taiwanese university student: a mediation model of learning self-efficacy and social self-efficacy. Comput Hum Behav. 2014;34:49–57.

Demirci K, Akgönül M, Akpinar A. Relationship of smartphone use severity with sleep quality, depression, and anxiety in university students. J Behav Addict. 2015;4(2):85–92.

Ghosh A, Jha R, Malakar SK. Pattern of smartphone use among MBBS students in an Indian medical college. IJAR. 2016;2(5):389–92.

Gowthami S, Kumar S. Impact of smartphone: a pilot study on positive and negative effects. Int J Scientific Eng Appl Sci (IJSEAS). 2016;2(3):473–8.

Toda M, Monden K, Kubo K, Morimoto K. Mobile phone dependence and health-related lifestyle of university students. Soc Behav Personal Int J. 2006;34(10):1277–84.

Ching SM, Yee A, Ramachandran V, Lim SMS, Sulaiman WAW, Foo YL, et al. Validation of a Malay version of the smartphone addiction scale among medical students in Malaysia. PLoS One. 2015;10(10):e0139337.

Nikmat AW, Hashim NA, Saidi MF, Zaki NSM, Shukri NNH, Abdulla NB. The use and addiction to smart phones among medical students and staffs in a public University in Malaysia. Asean J Psychiatry. 2018;19(1):98–104.

Aljomaa SS, Qudah MFA, Albursan IS, Bakhiet SF, Abduljabbar AS. Smartphone addiction among university students in the light of some variables. Comput Hum Behav. 2016;61:155–64.

Venkatesh E, Al Jemal MY, Al Samani AS. Smart phone usage and addiction among dental students in Saudi Arabia: a cross sectional study. Int J Adolesc Med Health. 2017;31(1). https://doi.org/10.1515/ijamh-2016-0133 .

Sethuraman AR, Rao S, Charlette L, Thatkar PV, Vincent V. Smartphone addiction among medical college students in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands. Int J Commun Med Public Health. 2018;5(10):4273–7.

Qudah MFA, Albursan IS, Bakhiet SFA, Hassan EMAH, Alfnan AA, Aljomaa SS, et al. Smartphone Addiction and Its Relationship with Cyberbullying Among University Students. Int J Ment Health Ad. 2019;17(3):628–43.

Alhazmi AA, Alzahrani SH, Baig M, Salawati EM, Alkatheri A. Prevalence and factors associated with smartphone addiction among medical students at king Abdulaziz University, Jeddah; 2018.

Tran TD, Tran T, Fisher J. Validation of the depression anxiety stress scales (DASS) 21 as a screening instrument for depression and anxiety in a rural community-based cohort of northern Vietnamese women. BMC Psychiatry. 2013;13(1):24.

Alosaimi FD, Alyahya H, Alshahwan H, Mahyijari NA, Shaik SA. Smartphone addiction among university students in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med J. 2016;37(6):675–83.

Matar Boumosleh J, Jaalouk D. Depression, anxiety, and smartphone addiction in university students- a cross sectional study. PLoS One. 2017;12(8):e0182239.

Yusoff MSB, Rahim AFA, Aziz RA, Pa MNM, Mey SC, Ja'afar R, et al. The validity and reliability of the USM personality inventory (USMaP-i): its use to identify personality of future medical students. Intern Med J. 2011;18(4):283–7.

Kwon M, Lee J-Y, Won W-Y, Park J-W, Min J-A, Hahn C, et al. Development and validation of a smartphone addiction scale (SAS). PLoS One. 2013;8(2):e56936.

Alhassan AA, Alqadhib EM, Taha NW, Alahmari RA, Salam M, Almutairi AF. The relationship between addiction to smartphone usage and depression among adults: a cross sectional study. BMC Psychiatry. 2018;18(1):148.

Bian M, Leung L. Linking loneliness, shyness, smartphone addiction symptoms, and patterns of smartphone use to social capital. Soc Sci Comput Rev. 2015;33(1):61–79.

M-o K, Kim H, Kim K, Ju S, Choi J, Yu M. Smartphone addiction: (focused depression, aggression and impulsion) among college students. Indian J Sci Technol. 2015;8(25):1–6.

Hong ENC, Hao LZ, Kumar R, Ramendran C, Kadiresan V. An effectiveness of human resource management practices on employee retention in institute of higher learning: a regression analysis. Int J Bus Res Manag. 2012;3(2):60–79.

Jamal A, Temsah M-H, Khan SA, Al-Eyadhy A, Koppel C, Chiang MF. Mobile phone use among medical residents: a cross-sectional multicenter survey in Saudi Arabia. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2016;4(2):e61.

Robinson R. Spectrum of tablet computer use by medical students and residents at an academic medical center. PeerJ. 2015;3:e1133.

Pulijala Y, Ma M, Ju X, Benington P, Ayoub A. Efficacy of three-dimensional visualization in mobile apps for patient education regarding orthognathic surgery. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2016;45(9):1081–5.

Browne G, O’Reilly D, Waters C, Tummon O, Devitt D, Stewart B, et al. Smart-phone and medical app use amongst Irish medical students: a survey of use and attitudes. In: BMC proceedings; 2015. BioMed Central.

Cochrane T, editor Mobile social media as a catalyst for pedagogical change. EdMedia+ innovate learning; 2014: Association for the Advancement of computing in education (AACE).

Makoe M. Exploring the use of MXit: a cell-phone social network to facilitate learning in distance education. Open Learning. 2010;25(3):251–7.

Nicholson S. Socialization in the “virtual hallway”: instant messaging in the asynchronous web-based distance education classroom. Internet High Educ. 2002;5(4):363–72.

Rambe P, Bere A. Using mobile instant messaging to leverage learner participation and transform pedagogy at a S outh a frican U niversity of T echnology. Br J Educ Technol. 2013;44(4):544–61.

Raiman L, Antbring R, Mahmood A. WhatsApp messenger as a tool to supplement medical education for medical students on clinical attachment. BMC Med Educ. 2017;17(1):7.

Parasuraman S, Sam AT, Yee SWK, Chuon BLC, Ren LY. Smartphone usage and increased risk of mobile phone addiction: a concurrent study. Int J Pharmaceutical Investigation. 2017;7(3):125–31.