Institute for the Study of Societal Issues

Center for research on social change.

The Center for Research on Social Change (CRSC), formerly named the Institute for the Study of Social Change (ISSC), was founded in 1976. CRSC researchers use a combination of qualitative and quantitative social science research methods to undertake empirical investigations into critical social issues in the United States and abroad, with a particular focus on how immigration, globalization, economic restructuring, and development of new technologies are shaping and changing the structure and culture of various spheres within societies throughout the world. Center research seeks to illuminate the lived experiences of people whose social locations are profoundly affected by broad processes of social change. Over the years, research projects at CRSC have helped to establish new research agendas and fields of study in the social sciences, and key findings have influenced academic research, public debate and social policy.

Center for Research on Social Change continues to examine pressing social issues concerning national and global processes of social change.

Center for Research on Social Change News

Aera awards in education research.

Two affiliates of the Center for Research on Social Change, Kris Gutiérrez and Travis Bristol , received awards from the American Educational ... Read more about AERA Awards in Education Research

Caste-Class Discrimination of Law Enforcement Officers

Cecilia Mo , Center for Research on Social Change faculty affiliate, is ... Read more about Caste-Class Discrimination of Law Enforcement Officers

Congratulations to Tianna Paschel!

Tianna Paschel , Center for Research on Social Change faculty affiliate, has been selected as this year's recipient of the Carol D. Soc Distinguished Graduate Student Mentoring Award for Early Career ... Read more about Congratulations to Tianna Paschel!

- 1 of 23 Center for Research on Social Change News (Current page)

- 2 of 23 Center for Research on Social Change News

- 3 of 23 Center for Research on Social Change News

- 4 of 23 Center for Research on Social Change News

- 5 of 23 Center for Research on Social Change News

- 6 of 23 Center for Research on Social Change News

- 7 of 23 Center for Research on Social Change News

- 8 of 23 Center for Research on Social Change News

- 9 of 23 Center for Research on Social Change News

- next › Center for Research on Social Change News

- last » Center for Research on Social Change News

Subscribe to our email list

Stay up-to-date on our events and news

Events (stay tuned for info coming soon!)

Module 18: Social Movements and Social Change

Causes of social change, learning outcomes.

- Explain how technology, social institutions, population, and the environment can bring about social change

Collective behavior and social movements are just two of the forces driving social change , which is the change in society created through social movements as well as external factors like environmental shifts or technological innovations. Essentially, any disruptive shift in the status quo, be it intentional or random, human-caused or natural, can lead to social change. Below are some of the likely causes.

Changes to technology, social institutions, population, and the environment, alone or in some combination, create change. Below, we will discuss how these act as agents of social change, and we’ll examine real-world examples. We will focus on four agents of change that social scientists recognize: technology, social institutions, population, and the environment.

Some would say that improving technology has made our lives easier. Imagine what your day would be like without the Internet, the automobile, or electricity. In The World Is Flat , Thomas Friedman (2005) argues that technology is a driving force behind globalization, while the other forces of social change (social institutions, population, environment) play comparatively minor roles. He suggests that we can view globalization as occurring in three distinct periods. First, globalization was driven by military expansion, powered by horsepower and wind power. The countries best able to take advantage of these power sources expanded the most, and exert control over the politics of the globe from the late fifteenth century to around the year 1800. The second shorter period from approximately 1800 C.E. to 2000 C.E. consisted of a globalizing economy. Steam and rail power were the guiding forces of social change and globalization in this period. Finally, Friedman brings us to the post-millennial era. In this period of globalization, change is driven by technology, particularly the Internet (Friedman 2005).

But also consider that technology can create change in the other three forces social scientists link to social change. Advances in medical technology allow otherwise infertile women to bear children, which indirectly leads to an increase in population. Advances in agricultural technology have allowed us to genetically alter and patent food products, which changes our environment in innumerable ways. From the way we educate children in the classroom to the way we grow the food we eat, technology has impacted all aspects of modern life.

Of course there are drawbacks. The increasing gap between the technological haves and have-nots––sometimes called the digital divide––occurs both locally and globally. Further, there are added security risks: the loss of privacy, the risk of total system failure (like the Y2K panic at the turn of the millennium), and the added vulnerability created by technological dependence. Think about the technology that goes into keeping nuclear power plants running safely and securely. What happens if an earthquake or other disaster, like in the case of Japan’s Fukushima plant, causes the technology to malfunction, not to mention the possibility of a systematic attack to our nation’s relatively vulnerable technological infrastructure?

Technology and Crowdsourcing

Millions of people today walk around with their heads tilted toward a small device held in their hands. Perhaps you are reading this textbook on a phone or tablet. People in developed societies now take communication technology for granted. How has this technology affected social change in our society and others? One very positive way is crowdsourcing.

Thanks to the web, digital crowdsourcing is the process of obtaining needed services, ideas, or content by soliciting contributions from a large group of people, and especially from an online community rather than from traditional employees or suppliers. Web-based companies such as Kickstarter have been created precisely for the purposes of raising large amounts of money in a short period of time, notably by sidestepping the traditional financing process. This book, or virtual book, is the product of a kind of crowdsourcing effort. It has been written and reviewed by several authors in a variety of fields to give you free access to a large amount of data produced at a low cost. The largest example of crowdsourced data is Wikipedia, the online encyclopedia which is the result of thousands of volunteers adding and correcting material.

Perhaps the most striking use of crowdsourcing is disaster relief. By tracking tweets and e-mails and organizing the data in order of urgency and quantity, relief agencies can address the most urgent calls for help, such as for medical aid, food, shelter, or rescue. On January 12, 2010 a devastating earthquake hit the nation of Haiti. By January 25, a crisis map had been created from more than 2,500 incident reports, and more reports were added every day. The same technology was used to assist victims of the Japanese earthquake and tsunami in 2011, and many more times in disasters since then.

The Darker Side of Technology: Electronic Aggression in the Information Age

One dark side of technology is known as “electronic aggression”. The U.S. Center for Disease Control (CDC) uses the term to describe “any type of harassment or bullying that occurs through e-mail, a chat room, instant messaging, a website (including blogs), or text messaging” (CDC, n.d.). We generally think of this as cyberbullying. Cyberbullying represents a powerful change in modern society. A 2011 study by the U.S. Department of Education found that 27.8 percent of students aged twelve through eighteen reported experiencing bullying. From the same sample 9 percent specifically reported having been a victim of cyberbullying (Robers et al. 2013). A more recent study conducted in 2016 on 5700 high school and middle school students between the ages of 12 and 17 found that 34% of students reported being cyber-bullied in their lifetime ( [1]

Cyberbullying is a special feature of the Internet. Something unique to electronic aggression is that it can happen twenty-four hours a day, every day—it can reach a child (or an adult) even though she or he might otherwise feel safe in a locked house. The messages and images may be posted anonymously and to a very wide audience, and they might even be impossible to trace. Finally, once posted, the texts and images are very hard to delete. Its effects range from the use of alcohol and drugs to lower self-esteem, health problems, and even suicide (CDC, n.d.).

The Story of Megan Meier

According to the Megan Meier Foundation web site (2014a), Megan Meier had a lifelong struggle with weight, attention deficit disorder, and depression. But then a sixteen-year-old boy named Josh Evans asked Megan, who was thirteen years old, to be friends on the social networking web site MySpace. The two began communicating online regularly, though they never met in person or spoke on the phone. Now Megan finally knew a boy who, she believed, really thought she was pretty.

But things changed, according to the Megan Meier Foundation web site (2014b). Josh began saying he didn’t want to be friends anymore, and the messages became cruel on October 16, 2006, when Josh concluded by telling Megan, “The world would be a better place without you.” The cyberbullying escalated when additional classmates and friends on MySpace began writing disturbing messages and bulletins. That night Megan hanged herself in her bedroom closet, three weeks before what would have been her fourteenth birthday.

According to an ABC News article titled, “Parents: Cyber Bullying Led to Teen’s Death” (2007), it was only later that a neighbor informed Megan’s parents that Josh was not a real person. Instead, “Josh’s” account was created by the mother of a girl who used to be friends with Megan.

You can find out more of Megan’s story at her mother’s web site .

or through her Ted Talk, “What Kids Have To Say About Bullying And How To End It” .

Social Institutions

Each change in a single social institution leads to changes in all social institutions. For example, the industrialization of society meant that there was no longer a need for large families to produce enough manual labor to run a farm. Further, new job opportunities were in close proximity to urban centers where living space was at a premium. The result is that the average family size shrunk significantly.

This same shift toward industrial corporate entities also changed the way we view government involvement in the private sector, created the global economy, provided new political platforms, and even spurred new religions and new forms of religious worship like Scientology. It has also informed the way we educate our children: originally schools were set up to accommodate an agricultural calendar so children could be home to work the fields in the summer, and even today, teaching models are largely based on preparing students for industrial jobs, despite that being an outdated need. A shift in one area, such as industrialization, means an interconnected impact across social institutions.

Population composition is changing at every level of society. Births increase in one nation and decrease in another. Some families delay childbirth while others start bringing children into their folds early. Population changes can be due to random external forces, like an epidemic, or shifts in other social institutions, as described above. But regardless of why and how it happens, population trends have a tremendous interrelated impact on all other aspects of society. For example, because we are experiencing an increase in our senior population as baby boomers begin to retire, this will in turn change the way many of our social institutions are organized. For instance, there is an increased demand for housing in warmer climates, a massive shift in the need for elder care and assisted living facilities, and growing awareness of elder abuse. There is concern about labor shortages as boomers retire, not to mention the knowledge gap as the most senior and accomplished leaders in different sectors start to leave. Further, as this large generation leaves the workforce, the loss of tax income and pressure on pension and retirement plans means that the financial stability of the country is threatened.

Globally, often the countries with the highest fertility rates are least able to absorb and attend to the needs of a growing population. Family planning is a large step in ensuring that families are not burdened with more children than they can care for. On a macro level, the increased population, particularly in the poorest parts of the globe, also leads to increased stress on the planet’s resources.

The Environment

Turning to human ecology, we know that individuals and the environment affect each other. As human populations move into more vulnerable areas, we see an increase in the number of people affected by natural disasters, and we see that human interaction with the environment increases the impact of those disasters. Part of this is simply the numbers: the more people there are on the planet, the more likely it is that some will be affected by a natural disaster.

But it goes beyond that. Movements like 350.org describe how we have already seen five extinctions of massive amounts of life on the planet, and the crisis of global change has put us on the verge of yet another. According to their website, “The number 350 means climate safety: to preserve a livable planet, scientists tell us we must reduce the amount of CO2 in the atmosphere from its current level of 400 parts per million to below 350 ppm” (350.org).

The environment is best described as an ecosystem, one that exists as the interplay of multiple parts including 8.7 million species of life. However dozens of species are going extinct every day, a number 1,000 times to 10,000 times the normal “background rate” and the highest rate since the dinosaurs disappeared 65 million years ago. The Center for Biological Diversity states that this extinction crisis, unlike previous ones caused by natural disasters, is “caused almost entirely by us” (Center for Biological Diversity, n.d.). The growth of the human population, currently over seven billion and expected to rise to nine or ten billion by 2050, perfectly correlates with the rising extinction rate of life on earth.

Hurricane Katrina: When It All Comes Together

We’ve mentioned that four key elements that affect social change are the environment , technology , social institutions , and population . In 2005, New Orleans was struck by a devastating hurricane. But it was not just the hurricane that was disastrous. It was the converging of all four of these elements, and the text below will connect the elements by putting the words in parentheses.

Before Hurricane Katrina (environment) hit, poorly coordinated evacuation efforts had left about 25 percent of the population, almost entirely African Americans who lacked private transportation, to suffer the consequences of the coming storm (demographics). Then “after the storm, when the levees broke, thousands more [refugees] came. And the city buses, meant to take them to proper shelters, were underwater” (Sullivan 2005). No public transportation was provided, drinking water and communications were delayed, and FEMA, the Federal Emergency Management Agency (institutions), was headed by an appointee with no real experience in emergency management. Those who were eventually evacuated did not know where they were being sent or how to contact family members. African Americans were sent the farthest from their homes. When the displaced began to return, public housing had not been reestablished, yet the Superdome stadium, which had served as a temporary disaster shelter, had been rebuilt. Homeowners received financial support, but renters did not.

As it turns out, it was not entirely the hurricane that cost the lives of 1,500 people, but the fact that the city’s storm levees (technology), which had been built too low and which failed to meet numerous other safety specifications, gave way, flooding the lower portions of the city, occupied almost entirely by African Americans.

Journalist Naomi Klein, in her book The Shock Doctrine: The Rise of Disaster Capitalism, presents a theory of a “triple shock,” consisting of an initial disaster, an economic shock that replaces public services with private (for-profit) ones, and a third shock consisting of the intense policing of the remaining public. Klein supports her claim by quoting then-Congressman Richard Baker as saying, “We finally cleaned up public housing in New Orleans. We couldn’t do it, but God did.” She quotes developer Joseph Canizaro as stating, “I think we have a clean sheet to start again. And with that clean sheet we have some very big opportunities.”

One clean sheet opportunity was that New Orleans began to replace public schools with charters, breaking the teachers’ union and firing all public school teachers (Mullins 2014). Public housing was seriously reduced and the poor were forced out altogether or into the suburbs far from medical and other facilities (The Advocate 2013). Finally, by relocating African Americans and changing the ratio of African Americans to whites, New Orleans changed its entire demographic makeup.

Think It Over

- Consider one of the major social movements of the twentieth century, from civil rights in the United States to Gandhi’s nonviolent protests in India. How would technology have changed it? Would change have come more quickly or more slowly? Defend your opinion.

- Discuss the digital divide in the context of modernization. Is there a real concern that poorer communities are lacking in technology? Why, or why not?

- Which theory do you think better explains the global economy: dependency theory (global inequity is due to the exploitation of peripheral and semi-peripheral nations by core nations) or modernization theory? Remember to justify your answer and provide specific examples.

- Do you think that modernization is beneficial or detrimental to societies? Explain, using examples.

- https://cyberbullying.org/2016-cyberbullying-data ↵

- Modification, adaptation, and original content. Authored by : Rebecca Vonderhaar for Lumen Learning. Provided by : Lumen Learning. License : CC BY: Attribution

- Social Change. Authored by : OpenStax CNX. Located at : https://cnx.org/contents/[email protected]:vi4eB2eh@5/Social-Change . License : CC BY: Attribution . License Terms : Download for free at http://cnx.org/contents/[email protected]

- Arts & Culture

- Civic Engagement

- Economic Development

- Environment

- Human Rights

- Social Services

- Water & Sanitation

- Foundations

- Nonprofits & NGOs

- Social Enterprise

- Collaboration

- Design Thinking

- Impact Investing

- Measurement & Evaluation

- Organizational Development

- Philanthropy & Funding

- Current Issue

- Sponsored Supplements

- Global Editions

- In-Depth Series

- Stanford PACS

- Submission Guidelines

Addressing Trauma as a Pathway to Social Change

How understanding intergenerational trauma can help people working toward social change solve problems more effectively.

- order reprints

- related stories

By Ijeoma Njaka & Duncan Peacock Jan. 21, 2021

In the 1860s, American abolitionist Frederick Douglass noted that people invested in social change “ endeavor to remove the contradiction ” between “what ought to be” and “what is.” This contradiction seems ubiquitous today as social change advocates struggle to address multiple, overlapping crises. Systemic racism, climate change , the forced displacement of millions of people , a devastating global pandemic, and other widespread social issues highlight how far we are from “what ought to be.” And each of these problems requires urgent and sustained attention.

At the same time, another problem is inhibiting and limiting sustained attention to these complex crises: trauma. We are learning that trauma, or distress resulting from exposure to chronic or extreme mental or physical stress, is a common human experience with the power to spread across people and time. Research reveals that if nothing is done to mitigate the influence of traumatic experiences, individuals afflicted by today’s challenges may pass their trauma to the next generation. This kind of transfer, known as “intergenerational trauma,” isn’t new to human experience, but research on it didn’t begin in earnest until the 1960s. Currently, the American Psychological Association describes it as “a phenomenon in which the descendants of a person who has experienced a terrifying event show adverse emotions and behavioral reactions to the event that are similar to those of the person him/herself.” Intergenerational trauma can persist long after the memory of the initial traumatic event has faded.

Related concepts about the way sources, experiences, or effects of trauma include but are not limited to individuals also sheds light on the problem. Collective trauma, for example, is a shared traumatic experience that can negatively affect entire communities. The “demoralization, disorientation, and loss of connection” of survivors at the Buffalo Creek disaster of 1972 is just one example. It can also refer to mass suffering incurred by the kind of high death rates and economic and social shutdowns we’ve seen during the COVID-19 pandemic. While researchers and others make appropriate distinctions between terms such as collective, historical , cultural , multigenerational, transgenerational , and generational trauma based on context, each expresses the phenomena of inherited or shared trauma.

As previous articles in this series have discussed, change makers—those actively engaged in building a healthy and just society—not only face and address trauma among the populations they serve, but also commonly experience personal harm and trauma as a result of their work. There is also growing evidence that these experiences impair their ability to foster organizational and social change, and that supporting personal well-being lies at the heart of effectively addressing social challenges. Until we better recognize the impact trauma has on individuals, organizations, and society, those working for social change will be limited in their ability to support human dignity, well-being, and resilience. Indeed, we must better understand trauma, discuss it, and integrate awareness of it into the culture of social change if we are to effectively address issues in which trauma and intergenerational trauma are factors.

With this in mind, a think tank launched by The Wellbeing Project and Georgetown University recently started a research program to better understand the connection between inner work (including self-inquiry, reflection, and self-care), outer change (work that individuals do to effect change in the world), and intergenerational trauma. The program is exploring intergenerational trauma with the idea that understanding its impact might advance the well-being of individuals working toward social change and the communities they work with, as well as increase the impact of their work. An initial field scan and literature review conducted in 2020 has revealed a diverse range of perspectives on intergenerational trauma through human stories and a variety of research-based disciplinary approaches. Here’s a look at what we’ve learned so far.

Defining the Challenge

Intergenerational trauma was initially documented in 1960s and 1970s studies of the Holocaust. Helen Epstein’s article “ Children of the Holocaust ” investigates how the experience and wounds of Holocaust survivors effected the lives of the following generation. Over time, the field has expanded to examine intergenerational trauma as a result of war, genocide, refugee experiences , health disparities , apartheid in South Africa , India’s caste system , American slavery and its legacies, poverty , and the oppression and violence against Indigenous Peoples . These and similar phenomena have been the source of mass trauma that has directly or indirectly affected multiple generations. However, intergenerational trauma doesn’t necessarily result from widespread social calamity. It can also result from unresolved trauma endured by mothers, or from trauma experienced by parents, grandparents, and further descendants, who can, knowingly or unknowingly, pass it down through feelings, memories, and even language .

Defining the problem isn’t just about identifying historical or ongoing instances of violence that cause this sort of trauma; it’s also about using the questions, methods, and tools of different fields and disciplines, as well as human stories, to examine and ultimately heal the damage at hand. A range of documented cases that incorporate epigenetics , or the study of heritable changes in gene function that aren’t part of the genetic code, show that stressors and trauma can change gene expression, and thus pass between generations . Historical trauma, such as trauma resulting from the forced displacement and destruction of Native American communities, has deleterious effects on physiological, psychological, and social dimensions of generations of lives. In addition to biology, this complex challenge is therefore also a concern of psychology, economics, and education. Given the relationship between social media, mental health, and democracy, the spread of trauma is also a concern of technology and ethics .

We are all situated in relation to historical and cultural narratives. If marked by trauma, the narratives people tell themselves and concepts of self can be maladaptive and can become mechanisms of historical trauma . The arts and storytelling are necessary tools for creating healthier narratives, and for creating narratives that honor the past but enable healing in the present and future. Going forward, researchers and practitioners must use a wide spectrum of interdisciplinary approaches informed by cross-sector and global perspectives to explore and document this topic.

Intergenerational Trauma as a Lens for Practicing Social Change

Over the past year, we’ve gleaned five initial insights about the connection between intergenerational trauma and the social change sector. In addition to undergirding our future research, we hope these insights can offer thought-provoking framing for current social change leaders.

1. Finding root causes and compounding factors . Recognizing intergenerational trauma can help spotlight and define the roots of social change issues.

Consider the high costs of poverty in the United States . Getting to the roots of the problem includes recognizing that the problem is not simply about individual failures and shortcomings. Addressing poverty requires that we ask questions about underlying systemic factors, such as structural racism , which compounds impoverishment by the mechanisms of discrimination and racial health disparities. It also raises questions about the unequal distribution of power and wealth , which affects economic, social, and political agency, including mobility in any of these areas.

Poverty also creates major challenges to mental well-being, not only due to lack of access to vital resources, but also because the chronic stress of living through poverty can lead to atrophy of the prefrontal cortex , an area of the brain needed for higher reasoning and control, judgement, and decision making. In other words, trauma caused by poverty itself can become a compounding factor that makes it more difficult to exit the cycle of poverty.

By looking at root causes and compounding circumstances, social change makers can deepen their understanding of the challenges they wish to solve and, in turn, shape more effective, future interventions.

2. Supporting change makers and the communities they serve . Addressing intergenerational trauma can help support change makers who have experienced intergenerational trauma themselves, including those who have chosen to work in social change partly to address the source of their trauma.

During the Rhodes Must Fall movement at the University of Cape Town (UCT), for example, student activists demanded the removal of a statue of imperialist Cecil Rhodes, who implemented policies that enabled the institutionalization of apartheid. Although many of the students were born after apartheid formally ended, the legacy of apartheid and colonial trauma remained . In 2016, the students created The Fall , a play about two UCT movements: Rhodes Must Fall and Fees Must Fall. These activist-artists found the process of creating the play and sharing their experiences therapeutic and healing for both themselves and their audience.

This type of process, which links the inner work of confronting intergenerational trauma with social change focused on its effects, is an effective way to both enhance well-being for change makers and broaden the reach of social change.

3. Recognizing trauma in the interconnectedness of the world . We are also learning that there are porous boundaries between the social problems we face today and the collective trauma that exacerbates them. In some instances, foundations of trauma cascade across seemingly unrelated areas of life and society.

Road congestion and gridlock in Atlanta, Georgia, for example , have roots in its interstate’s design to accommodate racial segregation while prioritizing white neighborhoods. They also reflect resistance to expanded public transit access from predominantly white areas. More broadly, capitalistic mechanisms that lead to increased economic mobility for certain populations (for example, educated or corporate groups) have negative impacts on personal health and families and the futures of low-income children .

For social change leaders, examining interconnectivity adds nuance to the social problems they work on and expands the possible types of resources that may address these issues. The interconnectedness of the world necessitates the use of many disciplines and human perspectives in concert with one another.

4. Activating healing from trauma . In his book, “The Body Keeps the Score,” trauma expert Bessel Van der Kolk explains that trauma compromises a person’s agency and ability to cope with overwhelming situations, implicating the well-being of the body, brain, and mind. However, it’s important to note that factors such as social support can mitigate the degree to which trauma takes hold in any given individual, and how it impacts even those who experienced the same event or conditions . And while trauma has the pernicious ability to become a vicious cycle, the pursuit of agency, dignity, and well-being can create the reverse—a virtuous cycle of healing.

The story of Desmond Meade, president of the Florida Rights Restoration Coalition, provides an example on the individual level. Voting for the first time in 2020 motivated him more than ever to continue restoring millions of other people’s right to vote. The agency he experienced when voting helped him reconnect with a sense of dignity—his inherent value as a participant in the democratic process. It also helped his psychological well-being, particularly as he considered the challenges of both his life and the lives of his historically disenfranchised Black American ancestors.

Another example is the therapeutic storytelling practice Testimony Therapy , which has helped survivors of war and political violence, and political refugees heal from trauma by sharing their personal stories in a way that rigorously documents and preserves their testimony.

Social change initiatives of all kinds can also incorporate measures to heal trauma. For example, restorative-justice initiatives such as the Truth and Reconciliation Commission in South Africa and the Colombia Peace Process both included reparation and rehabilitation measures, with the aim of giving formerly oppressed people a voice and fostering agency. And from their inception in the United States, both the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s , and the current Black Lives Matter movement have asserted the dignity of all, and demanded political, economic, and social agency for those who have been oppressed and excluded.

These examples illustrate how social change leaders can develop their own initiatives and movements in ways that use agency, dignity, and well-being as methods for addressing cycles of trauma.

5. Honoring the role of time and connection . When American civil rights leader Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. emphasized the maxim , “Justice too long delayed is justice denied,” he recognized the role of time in achieving justice. In a similar way, healing that is too long delayed not only is denied, but also can allow problems to worsen. The longer people experience traumatizing conditions or unresolved trauma, the more trauma can compound , and the more it can fatigue people , even spreading to others who otherwise may have remained resilient or whose particular experiences were radically different.

Scholar Suraj Yengde has described the traumas he and other generations of Dalits have endured from the caste system. In addition to shared conditions of diminished mobility, poverty, abuse , and cultural erasure , Yengde notes how trauma can even limit the dreams and aspirations other community members. Time is therefore of the essence when it comes to healing. And just as unaddressed trauma can permeate through generations over time , addressing trauma requires sustained attention and support .

Connection—between body to mind, one human to another, one generation to the next, and inner selves to outer environments—is another distinctive element of healing. Interoception (awareness of what’s going on in the body), somatic therapy (grounding in the body through movement), and relationships and a sense of belonging all facilitate healing by re-establishing connections that are fundamental for humans.

Writer and founder of the Academy of Inner Science Thomas Hübl suggests that one of the most important connections for healing collective and intergenerational trauma is between science and spirit, which he argues brings together the “double helix of ancient wisdom and contemporary understanding.” Humans experience well-being when we have agency, dignity, and health, and are connected to ourselves, each other, and our world in sustainable and life-giving ways. Trauma is the disconnection from these things. Those working on social change, therefore, need to identify the connections and disconnections in the issues they care about. They also need support when they experience disconnection in their own lives.

A Call to Action

The social sector needs to take a few steps to address intergenerational trauma, and achieve the inner well-being of individuals and communities. First, we must recognize intergenerational trauma as a widespread challenge to achieving well-being at scale—one that requires ongoing attention and healing in different forms for different human experiences. Second, we need to advocate for the active exploration of intergenerational trauma within the social change sector—indeed, for it to become a core focus, integrated with mainstream work. Third, we must deepen scholarship on intergenerational trauma using an interdisciplinary approach informed by a range of diverse human experiences and stories. And finally, we must develop methods and practices for healing that join inner and outer work, and connect dignity, agency, and well-being to avenues for social change.

Over the next year, The Wellbeing Project and Georgetown University—in conjunction with a global, multidisciplinary panel of experts and associate voices—will continue to explore the effects of intergenerational trauma on individuals, communities, and the social sector, with the following principles in mind:

1. Examine the roots, not just the symptoms of these problems. Instances of intergenerational trauma can often be broken down into a multitude of interrelated factors.

2. Synthesize a range of perspectives and connect them in new ways. This includes using many disciplines, examining many sectors of human life, and listening to many human stories to understand how intergenerational trauma begins and unfolds.

3. Establish a range of approaches to healing, including using varied forms of therapy or well-being practices , using the arts and storytelling, bridging cultural divides, advocating , researching , enacting policy, and changing laws .

4. Engage and contribute to the work of various sectors, including social change, policy, and education.

In a November 2020 interview , former US President Barack Obama said that the country will continue to fall short in the change Americans seek if we only address symptoms and ignore the underlying causes of social problems. He described how the deaths of too many Black Americans “is part and parcel with a legacy of discrimination, and Jim Crow, and segregation,” and that the only way to address the injustices of the criminal justice system is to look at the economy, housing, and other interconnected factors that impede progress. “The good news,” he said, “is that we can all take responsibility.” These insights also apply to social change leaders addressing intergenerational trauma and well-being. We can begin to address traumatic experiences that have permeated communities through identifying root causes, supporting change makers’ healing, and understanding interconnected problems and outcomes. The ubiquity of these obstacles means that the opportunity for change is ubiquitous as well.

Support SSIR ’s coverage of cross-sector solutions to global challenges. Help us further the reach of innovative ideas. Donate today .

Read more stories by Ijeoma Njaka & Duncan Peacock .

SSIR.org and/or its third-party tools use cookies, which are necessary to its functioning and to our better understanding of user needs. By closing this banner, scrolling this page, clicking a link or continuing to otherwise browse this site, you agree to the use of cookies.

We're tackling these complex questions around social movement impacts and success factors using a cluster-thinking approach, where we try approach our research question from many different angles. See our various projects below.

What was the impact of the Insulate Britain campaign?

Insulate Britain were a campaign group who carried out a series of nonviolent disruptive actions on UK motorways between September and November 2021. Social Change Lab undertook an impact analysis of the campaign to assess the extent to which Insulate Britain achieved their aims and changed UK Government policy. We assessed quantitative evidence including media coverage, parliamentary mentions, Google searches, and opinion polls, and qualitative evidence from interviews with MPs, NGOs, academics, industry representatives and activists. You can read the full research report here .

The effects of different protest tactics and messaging strategies on attitudes towards animals

Animal Rising disrupted the 2023 Grand National, the biggest horse racing event in the UK, kickstarting a national conversation about society’s relationship with animals. We conducted nationally representative public opinion polling to understand the impact this had on UK public attitudes towards animals. Additionally, we used internal data from Animal Rising to understand the impact of this protest on their mobilisation of activists, donations and media coverage.

We discover mixed signals - whilst these protests led to significantly increased public salience of animal issues and increased sign-ups for Animal Rising's future actions, they had some negative consequences on UK public attitudes towards animals. This research report can also be read as a Google Document here . You can see our updated findings from 6-months later here .

We conducted a randomised controlled trial experiment with 4,757 participants to study how people’s attitudes towards animals are affected by descriptions of different animal rights protests and different messaging strategies. We tested the effects of three different protest campaign types (horse race disruptions, open rescues and KFC blockades) and three different messaging strategies (values/norms-led, problem-led and solution-led messaging). We found that most types of disruptive protest negatively affected participants' views, and that values/norms-led and problem-led messaging performed better than messaging focused on solutions.

The short and long term effects of disruptive animal rights protest

February 2024

Social Change Lab evaluated the short and longer term effects of Animal Rising's protest at the 2023 Grand National, using nationally representative longitudinal and cross-sectional polls, a controlled vignette study, media analysis, and mobilisation analysis. Following the protest, there was a noticeable deterioration in people's attitudes towards animals linked to the extent to which they were aware of the protest. However, six months later, these negative effects had dissipated,. We also found an overall improvement in attitudes towards animals, regardless of people's awareness of the protest.

Mapping the UK Farmed Animal Advocacy Movement

December 2023

Social Change Lab surveyed 17 nonprofit organisations involved in the UK farmed animal movement. Collectively, these organisations account for over £13m of resources, which we believe is the vast majority of UK farmed animal funding. This report outlines the resource allocation within the sector, considering funding allocated to different strategies and stakeholders (e.g. corporate welfare campaigns vs government advocacy).

We hope that having the whole farmed animal landscape mapped in this way will help organisations evaluate the approaches they are using or considering, as well as identify gaps and new opportunities in the movement as a whole. You can also read this report as a Google Doc here .

Animal Rising's Grand National protest: Public opinion impacts and beyond

August 2023

What do experts think about social movements and protest?

Working with Apollo Academic Surveys, we surveyed 120 academics who study social movements and protest, across Political Science, Sociology and other relevant disciplines.

We asked them a range of questions about disruptive protest, the main reasons social movements fail to achieve their goals, the most important factors for success, polarisation, and more . Check out the summarised results on the Apollo

website here , or read our full report, with additional analysis and interpretation, here .

How philanthropists can support social movements - and why it matters

In this piece , we examine the funding landscape for social movement organisations: How much do grassroots organisations get relative to more traditional nonprofits? And what role do these grassroots organisations play in the ecosystem of social change?

We also explore common barriers for philanthropists in funding grassroots organisations, and offer five practical recommendations for how to meaningfully support social movement organisations.

What makes a protest movement successful?

January 2023

Social Change Lab undertook six months of research looking into what makes a protest movement successful. We examine factors such as numbers, nonviolence, diversity, external factors, the radical flank effect, and more. We conducted this research using a range of methods: literature review, public opinion polling, expert interviews and a case study.

You can also read a Google Docs version of the full report, as well as a summary blog post

How do radical tactics affect moderate groups? Public opinion polling from a Just Stop Oil campaign

December 2022

We conducted two longitudinal and nationally representative surveys (N=1415), using YouGov, to understand whether a Just Stop Oil campaign had any impact on support for or identification with more moderate climate organisations. This was for the November 2022 Just Stop Oil campaign targeting the M25 motorway. In this polling, w e detected a positive radical flank effect, whereby increased awareness of Just Stop Oil resulted in increased support for and identification with Friends of the Earth.

Literature Review: What makes a protest movement successful?

October 2022

A literature review of existing sociological and political science literature on success factors for protest movements. We examine work primarily looking at nonviolence, numbers, the radical flank effect, and external contextual factors.

A case study of UK anti-animal testing activism: SHAC

November 2022

A case study looking at the successes, potential shortcomings and lessons from Stop Huntingdon Animal Cruelty, an animal rights campaign in the 2000s. We identify some key reasons why they achieved significant successes, as well as potential reasons that led to their later decline.

Protest Movements: How effective are they?

Social Change Lab undertook six months of research looking into the outcomes of protests and protest movements. In this report, we synthesise our research, which we conducted using various research methods, such as literature reviews, public opinion polling, expert interviews, policymaker interviews and a cost-effectiveness analysis. We focus specifically on examining the impact of protest movements on public opinion, policy change, public discourse and media coverage, voting behaviour, and corporate behaviour.

You can also read a Google Docs version here.

Policymaker interviews

We interviewed 3 UK Civil Servants to understand the impact of protest movements on UK policymaking. We wanted to elicit questions such as

What role do protest movements play in policymakers' perceptions of public opinion?

Why do some social movements seem to be more successful in influencing policy?

See an analysis of our interviews here and our full summary notes of our conversations here.

Just Stop Oil: Public Opinion Polling

We conducted 3x 2,000 person nationally representative public opinion polls before, during and after a major protest campaign in the UK, Just Stop Oil. Despite disruptive protests, there was no loss of support for climate policies, providing some evidence against the notion that disruptive protests tend to cause a negative public reaction. Furthermore, our findings suggest that the protests had increased respondents’ self-perceived likelihood of participating in environmental activism (p=0.09)

What are the key bottlenecks of social movement organisations?

This report presents results from an informal survey of 16 individuals across 13 grassroots social movement organisations, (SMOs) focusing on climate and animal advocacy. We discuss the key limiting factors of these SMOs, as well as recommendations for how funders or external actors can support them.

Animal Rebellion: Public Opinion Polling

We conducted 2 x 1,500 person longitudinal and nationally representative public opinion polls before and after a major animal advocacy campaign in the UK, organised by Animal Rebellion.

Expert Interviews

We've interviewed 12 academics and movement experts to elicit answers to questions that we believe are not yet answered in existing literature. Examples include:

How important are external factors relative to a movement's own strategy and tactics?

To what degree does existing literature generalise to other countries, issues or time periods?

See full summary notes from our conversations here.

Protest Outcomes: Literature Review

A literature review of existing sociological and political science literature on movement outcomes. We examined outcomes ranging from policy change, public opinion shifts, voting behaviour, public discourse, and corporate behaviour.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 29 May 2024

How does the circular economy achieve social change? Assessment in terms of sustainable development goals

- Dolores Gallardo-Vázquez ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-4749-6034 1 ,

- Sabina Scarpellini 2 ,

- Alfonso Aranda-Usón 2 &

- Carlos Fernández-Bandera 1

Humanities and Social Sciences Communications volume 11 , Article number: 692 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

Metrics details

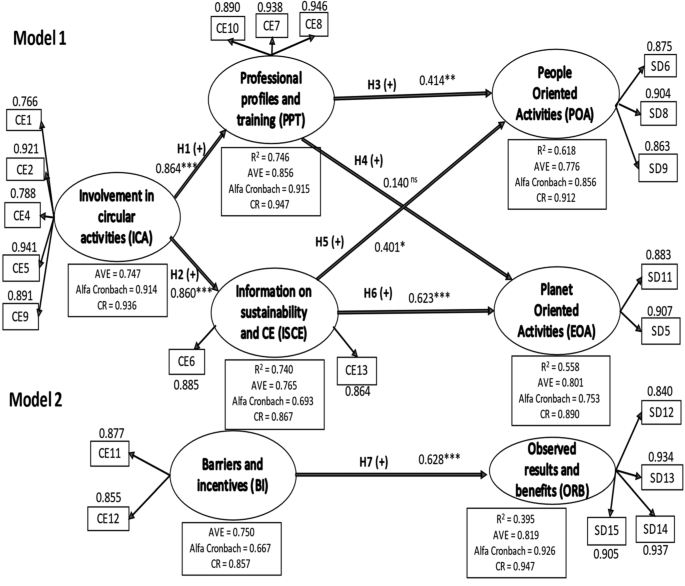

- Business and management

Achieving sustainable development is today a basic premise for all companies and governments. The 2030 Agenda has outlined an action plan focused on all areas and interest groups. Achieving economic growth and technological progress, social development, peace, justice, environmental protection, inclusion and prosperity represent the main areas to achieve social change. Furthermore, the circular economy is capable of improving the efficiency of products and resources, and can contribute to this social change, but there is a gap in the literature regarding whether the orientation of the companies in their circular economy strategy can lead to the achievement of the sustainable development goals. The objective of this study is to develop an initial circular economy-sustainable development goals (CE-SDGs) framework that considers the circular economy as the precedent and sustainable development goals as a consequence of implementing a circular economy. With respect to the methodology, the literature linking the relationship between the circular economy and sustainable development goals was reviewed first. A Structural Equation Model with the Partial Least Squares technique was also employed, analyzing two complementary models in enterprises involved in the Social Economy in the Autonomous Community of Extremadura (Spain). Regarding the results obtained, a link has been observed between professional profiles and training in people-oriented activities. The same does not occur for activities oriented toward the planet. Moreover, the existence of corporate reports that obtain data on circular activities is crucial to achieving orientation toward the sustainable development goals, for activities oriented toward both people and the planet. Finally, the results confirm that the existence of barriers and incentives determines the observed results, being aware that the lack of specialized training in human resources always has a significant incidence. Using resource and capability and dynamic capabilities theories, this study contributes with an initial framework by joining two lines of research and analyzing the CE-SDGs link in SE enterprises. Future research and empirical validations could contribute more deeply to the literature. As key recommendations, social economy managers must be committed to introducing circular economy practices to achieve people- and planet-oriented objectives, being proactive in fostering CE-SDGs frameworks .

Similar content being viewed by others

Toward a new understanding of environmental and financial performance through corporate social responsibility, green innovation, and sustainable development

Assessing regional performance for the Sustainable Development Goals in Italy

Integration of Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) criteria: their impacts on corporate sustainability performance

Introduction.

Sustainability-oriented social and environmental changes imply the need to reconsider ecosystem limitations within the framework of ecological transitions and economic inequalities to promote fairer, more equitable, and democratic economic models (Villalba-Eguiluz et al., 2020 ; Llena-Macarulla et al., 2023 ; Schaltegger et al., 2023 ). The problem of inequality is addressed from the context of the Social Economy (SE), seeing the Circular Economy (CE) as an economic model for sustainability and the approach to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) as a mirror of this sustainable model. The natural and social focus of these enterprises leads us to consider these actions being linked to severe repercussions, not only economic but also social and environmental.

Both the CE and the SDGs are interrelated concepts that complement each other in the context of the SE. Both approaches share similar objectives in terms of promoting environmental, social and economic sustainability (García-Saravia Ortiz-de-Montellano et al., 2023 ). CE is intended to offer an alternative to the traditional linear economy, which is based on the extraction, manufacturing, use and disposal of resources (Bocken et al., 2014 ; Scarpellini, 2022 ). The SDGs provide a global vision of sustainable development, encompassing economic, social and environmental dimensions (Khaskheli et al., 2020 ; Brodny and Tutak, 2023a ). SE entities can adopt circular approaches in their business operations, such as material reuse, product recycling, a sharing economy and cleaner production. They can also contribute significantly to the achievement of the SDGs by creating decent employment, reducing poverty, promoting gender equality, protecting the environment and promoting social inclusion.

More recently, the literature has highlighted the importance of these two lines of research as separate streams (Hussain et al., 2023 ). However, only a few studies have linked both lines or explored the importance of this connection (Merli et al., 2018 ; Dwivedi et al., 2022 ; García-Saravia Ortiz-de-Montellano et al., 2023 ). Joint approaches in CE and SDGs have determined the existence of gaps between the orientation toward products/materials and toward people and socioeconomic aspects, and therefore toward social change (García-Saravia Ortiz-de-Montellano et al., 2023 ). Other studies have linked CE and the SDGs in the technology sector as being capable of generating the corresponding social change (Dantas et al., 2021 ). The use of ICT tools is also missing, such as circular resources, capable of supporting circularity and generating circular value creation, as well as the identification of sustainable communities with a value-generating product-service orientation (Pollard et al., 2023 ). It should not be forgotten that innovation plays an important role in this transition toward a CE that promotes the development of new technologies, the creation of more efficient and sustainable production processes, and business models and practices that facilitate the reduction, reuse and recycling of resources, as well as reduction of the environmental impact (Ghisellini et al., 2016 ; Brodny and Tutak, 2023b ). Innovation in the design of products and services will at the same time create more durable, repairable and recyclable products, facilitating the transition to a CE (Kirchherr et al., 2017 ). Innovation also can drive the creation of new business models that promote circularity, on-demand production and product services (Geissdoerfer et al., 2017 ). In terms of collaboration and co-creation, open innovation and collaboration between different actors (i.e., companies, governments, academic institutions and civil society) can boost CE by promoting the exchange of knowledge, resources, best practices and co-creation of sustainable solutions (Schiederig et al., 2012 ; Brodny and Tutak, 2023b ). Economic and employment growth will be achieved with all of the above, important factors derived from successful innovation and in line with the 2030 Agenda (Szopik-Depczynska et al., 2018 ).

There are opinions focused on the need to establish policies that promote CE in all EU countries (Rodríguez-Antón et al., 2022 ). Recent opinions indicate that the incorporation of CE into companies will encourage a debate on the measurement of monetary value versus the value of the physical economy in the framework of sustainability (Llena-Macarulla et al., 2023 ), leading to economic and financial aspects being considered, as well as social variables. Furthermore, Scarpellini ( 2022 ) advocates the construction of a new conceptual framework that promotes the integration of CE with sustainability in new circular business models. Having identified possible gaps in the literature (social/economic orientation, application of ICTs, policies promoting CE, monetary value/sustainable value and creation of a conceptual framework), this research has focused on the last of them and, more precisely, with a SE-based approach, grouping together the experience of those entities capable of covering these social, economic and environmental areas, something which constitutes the novelty of the study.

The current concern is to delve into how the SE can contribute to the implementation of circular models in Extremadura, particularly within the framework of the “ Green and circular economy strategy. Extremadura 2030” (Junta de Extremadura, 2022 ). It is possible to identify synergies and complementarities between the SE and CE models and analyze different common aspects in which SE enterprises are involved within the framework of the aforementioned strategy. A comprehensive map of CE’s role as a driver of the CE-SDGs relationship has as a result yet to be developed (García-Saravia Ortiz-de-Montellano et al., 2023 ). The resulting gap in the literature creates uncertainty about whether companies’ orientation in their CE strategy can affect their achievement of SDGs, namely, attaining economic growth while protecting the environment and society (Pomponi and Moncaster, 2017 ; Schöggl et al., 2020 ). The present study sought to answer the following research questions (RQ):

RQ1: Is it possible to achieve the sustainable development goals through involvement in circular economy and activities of this kind?

RQ2: Does the information on sustainability and circular economy make it possible to achieve the sustainable development goals?

RQ3: Do professional profiles and training in circular economy make it possible to achieve the sustainable development goals?

RQ4: Can the barriers and incentives to the circular economy strategy condition the achievement of sustainable development goals?

To answer these questions, this study developed a novel CE-SDGs framework, with CE as the precedent and SDGs as the consequence of joining the CE. More specifically, the proposed CE precedent model was tested to determine whether the enterprises involved in CE activities have adequately defined their professional profiles, provided sufficient training to their stakeholders, and gathered enough information on sustainability and the CE. In addition, the analysis focused on whether these organizations are oriented toward achieving SDGs and are capable of achieving them, especially in terms of people- and planet-oriented activities. These features are part of an SDG consequence model developed for this research that reflects the greater emphasis on these goals proposed by García-Saravia Ortiz-de-Montellano et al., 2023 , Rodríguez-Antón et al. ( 2022 ) and Dantas et al. ( 2021 ). The present study thus aimed to develop a more holistic perspective than that offered by other authors who have concentrated on CE strategies and their contributions to achieving SDGs (i.e., SDGs 8, 12, and 13 to a greater extent and SDGs 4, 5, 10, and 16 to a lesser extent) (García-Saravia Ortiz-de-Montellano et al., 2023 ). The current results provide objective evidence of a relationship between the SDGs and the CE that the literature has previously failed to provide (Millar et al., 2019 ), thereby expanding the existing knowledge through more in-depth research (Schroeder et al., 2019 ).

To do this, the literature linking the relationship between CE and SDGs was reviewed first; secondly, two complementary structural equation models (SEMs), applying the partial least squares (PLS) technique, were used to analyze the models in Social Economy enterprises in the Autonomous Community of Extremadura (Spain). Using resources and capabilities and dynamic capabilities theories, this study contributes with an initial framework by joining two lines of research and analyzing the CE-SDGs link in SE enterprises.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 presents the theoretical background for defining the hypotheses. Section 3 deals with the method applied, explaining the data analysis, samples, measurement scales, and the methodology employed. Section 4 presents the results of the empirical models, evaluates the measurement and structural models, and discusses their predictive power. Section 5 presents the discussion, and Section 6 concludes the paper with outlines, implications, limitations, and future research directions.

Literature review

Resources and capabilities theory, and dynamic capabilities theory.

With respect to the theoretical framework, this study contributes to a combination of resource-based view (RBV) and dynamic capabilities (DC) theories. According to the RBV, companies can be viewed as an integrated set of heterogeneously distributed resources and capabilities (R&C) incorporated into their strategy, generating social and environmental impacts (Sassanelli et al., 2020 ; Abeysekera, 2022 ). These R&C are valuable, rare, inimitable, and non-substitutable assets that can obtain competitive advantage and contribute to sustainable value creation (Hitt et al., 2020 ; Asiaei et al., 2020 ; Caby et al., 2020 ). These intangible assets affect corporate performance (Asiaei et al., 2020 ; Asiaei et al., 2021 ), and companies must integrate and accumulate critical assets to create value-creating potential. Once the performance has been evaluated, the efficiency and effectiveness of actions can be quantified (Kamble and Gunasekaran, 2020 ), determining the possible benefits of the strategic resources used (Asiaei and Jusoh, 2017 ). Companies can support the integration and engagement of sustainability through their supply chains in particular and their different activities in general, implementing a business strategy that provides corporate performance through efficient resources (Gallardo-Vázquez and Valdez Juárez, 2022 ). The vision is that by implementing CE activities in companies, the resources and capacities applied in their development correspond to intangible assets and can influence organizational performance and generate an impact that results in the achievement of the SDGs.

The dynamic capabilities theory has its roots in resource-based theory, with this new approach seeking to take companies to a higher level of responsibility with a dual-benefit approach (i.e., company-society) (Gallardo-Vázquez and Valdez Juárez, 2022 ). In addition, this theory includes the detection and exploitation of opportunities in potential markets, helping organizations execute and apply internal and external resources to achieve sustainable results (Kachouie et al., 2018 ; Belhadi et al., 2022 ). Strategic and dynamic capabilities are pillars that can sustain an organization’s growth, such as CE activities and knowledge generated to facilitate the development and execution of strategic plans (Ledesma-Chaves et al., 2020 ; Bitencourt et al., 2020 ).

Social economy enterprises and circular economy: Precedent

The SE comprises a set of economic and business activities carried out by enterprises in the private sphere that pursue general economic or social interests, or both (Law 5/ 2011 , of March 29, on Social Economy). Its guiding principles are as follows: (i) Prioritizing people and the social purpose over profit, promoting autonomous, transparent, democratic, and participatory management; (ii) applying the results obtained to the corporate purpose of the entity; and (iii) promoting internal solidarity with society, contributing to local development, gender equality opportunities, social cohesion, the integration of people at risk of social exclusion, the generation of stable employment and quality, the reconciliation of personal, family, and work life, and sustainability in all its aspects.

The CE has in addition been proposed by different fields as an alternative to linear models based on extraction, production, use, and disposal, forecasting an adaptation of the current models to an economy of zero emissions and waste (Schaltegger et al., 2023 ; Llena-Macarulla et al., 2023 ; Ahmad et al., 2023 ). This includes both new business models based on the rental or leasing of services (Scarpellini, 2022 ), as well as the closing of material loops in different activities and sectors in the CE framework, and improving the efficiency of products in both the manufacturing and use phases (Benito-Bentué et al., 2022 ; Marco-Fondevila et al., 2021 ; Matos et al., 2023 ). This model of closing material loops is being introduced both at a macroeconomic level and in companies and organizations that are increasingly adopting CE principles in the production and provision of services (Aranda-Usón et al., 2020 ), and it is equally applicable to SE enterprises (Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, OECD, 2022 ).

With a holistic focus on the conservation of resources and an orientation toward obtaining corporate performance, this study addresses CE, which has the potential to bring economic activities back within environmental boundaries (Garcia-Saravia Ortiz-de-Montellano and van der Meer, 2022 ; Scarpellini, 2022 ; Ahmad et al., 2023 ; Skare et al., 2024 ). The CE seeks to convert waste into new resources and make innovative changes in current production systems to encourage regeneration within a sustainable development framework (Chaves Ávila and Monzón Campos, 2018 ; Llena-Macarulla et al., 2023 ). Consumption and production cycles can in this way become more sustainable while promoting economic prosperity and social equity (Kirchherr et al., 2017 ). Concurrently, the CE is expected to contribute to ensuring development that respects the environmental limits of natural resource exploitation, thereby enhancing environmental quality (Marco-Fondevila et al., 2018 ). This approach is oriented toward social, environmental, and technological change, which can come together within the CE.

In Spain, the First Circular Economy Action Plan 2021–2023 (Government of Spain, 2021 ) contemplates the active participation of SE enterprises in different areas of the CE, and it is worth mentioning the recycling of products, the market for second-hand goods (with the transfer of municipal spaces to SE associations and enterprises), the reuse of products within the social and solidarity economy (directly or indirectly through their prior preparation), or the promotion of responsible consumption and training activities. The Plan also recognizes that the SE has been a pioneer in the creation of employment linked to the CE and that its potential will be strengthened by the mutual benefits that support ecological transition and the reinforcement of social inclusion. There is a dynamic capacity for complementary resources and activities that determines sustainable development.

SE enterprises have pioneered the expansion of CE practices in the European Union. An analysis of complementarities between CE and SE has been undertaken in recent years at local and regional levels (FEMP, 2019 ; Villalba-Eguiluz et al., 2020 ), in the European Union (EU) (European Economic and Social Committee, 2016 ), internationally (OECD, 2022 ), and in Spain (Government of Spain, 2021 ). Among the most important aspects common to the SE and CE are those related to the principles of equity (which distinguishes between SE enterprises and private sector enterprises based on competitive advantage objectives) and democratic and collaborative governance, favoring a prioritization of the reduction/reuse of materials more typical of the CE in a framework of common good advocated by the SE and of undoubted interest in accountability practices (Pesci et al., 2020 ). However, the contribution of SE to CE has not yet been fully developed and requires further study for its definition and, in particular, for its measurement to define strategies and action plans that directly link these two fields.

Within this framework, the CE and SE have several aspects in common, as they are models based on sustainable development and people (European Economic and Social Committee, 2016 ). The CE primarily pursues the creation and retention of environmental and economic values, and there is a clear complementarity between the CE and SE models. SE and circular models can in particular reinforce the positive social impact of circular activities and accelerate the transition to a CE that requires creative and innovative capacity, particularly at a local level, in order to close material loops in the CE through integrated business models focused on proximity to the place of use of the product or service (Villalba-Eguiluz et al., 2020 ; Ahmad et al., 2023 ; Matos et al., 2023 ; Skare et al., 2024 ). The possibility of merging approaches based on SE, social innovation, and social entrepreneurship with the ecological potential of CE for the social good has therefore been explored (Soufani et al., 2018 ).

In the EU, the synergies of the SE with the CE arise from the fact that these enterprises carry out waste reuse and recycling processes in addition to being seen in sectors such as energy and agriculture (European Economic and Social Committee, 2016 ). The European Commission, in its EU action plan for CE, recognized that SE companies can make a key contribution to CE (European Commission, 2015 ), and the link between CE and SE can be viewed in the three pillars of sustainable development: Environmental, economic and social development, the latter being explored less (Scarpellini, 2022 ).

The common guidelines between the SE and CE models focus on collaborative and symbiotic governance measures that allow the introduction of business models in these enterprises. Among the points both models have in common, the following stand out (Villalba-Eguiluz et al., 2020 ; Dantas et al., 2021 ; Pollard et al., 2023 ; Brodny and Tutak, 2023b ): (i) The principle of cooperation and collaboration in the face of free market competition. (ii) The need for regional and industry networks, prioritizing aspects of a local or regional scope. (iii) The centrality of work in both models with labor-intensive processes (such as repair, remanufacturing or recycling in the case of CE). (iv) The systemic transition proposed by the institutions based on the externalities generated. (v) The changes in market paradigms through servitization (typical of CE) and the collaborative economy (intrinsic to SE) that come together in both models.

Social economy enterprises and sustainable development goals: Consequence

SE enterprises have pioneered the expansion of sustainable social development (Khaskheli et al., 2020 ). SE supposes a complementary concept of business efficiency and the social responsibility of private institutions, giving rise to a rational and social reconciliation of private action that makes them ideal for contributing to the achievement of the SDGs and their objectives, as well as being undertaken according to the SDGs established (Mozas, 2019 ; Flores, 2021 ; García-Saravia Ortiz-de-Montellano et al., 2023 ; Allen et al., 2024 ). This situation makes these enterprises fundamental agents for the sustainable development of current societies, helping them to develop social innovation processes that implement sustainable actions oriented toward the triple bottom line, i.e., economic, social, and environmental benefits (Hoang et al., 2021 ; Henry et al., 2019 ).

Mention should be made of the United Nations General Assembly ( 2015 ) resolution in which a set of global objectives was approved and the SDGs were included in the 2030 Agenda, aiming to eradicate or at least alleviate some structural problems of various kinds that the planet is currently facing, and proposing a time horizon that extends to 2030 (Calabrese et al., 2021 ). These SDGs comprise an action plan that seeks to benefit people and the planet, as well as increasing prosperity to strengthen universal peace based on a broader concept of freedom. The goals also promote the eradication of poverty worldwide and the achievement of sustainable production and consumption (Khaskheli et al., 2020 ; Brodny and Tutak, 2023a ).

The literature contains many studies that have focused on the achievement of different SDGs. More specifically, research has concentrated on SDG 1 (i.e., end of poverty), seeking to foster inclusive development by analyzing quality of growth, inequality, and poverty in developing countries (Asongu and Odhiambo, 2019 ). Other researchers have explored SDG 7 (i.e., affordable and clean energy) by evaluating the positive impact of foreign investment used to complete projects, but taking into account possible adverse environmental consequences for recipient countries (Schroeder et al., 2019 ; Aust and Isabel, 2020 ; D’Orazio and Löwenstein, 2020 ; Xiao et al., 2024 ). Studies of SDG 8 (i.e., decent work and economic growth) have analyzed participation and cooperation between governments, financial institutions, companies, and consumers, as well as examining the evolution of green finance, improvements in innovation capacity, and green economy transformation (John et al., 2019 ; Schroeder et al., 2019 ; Cui et al., 2020 ; Szopik-Depczynska et al., 2018 ).

Research on SDG 10 (i.e., reduction of inequalities) has found that sustainable banking plays an important role by generating two-way trust in loan recipients’ ability to overcome institutional limitations, especially in countries with a weak rule of law (Úbeda et al., 2022 ). Research has further focused on SDG 11 (i.e., sustainable cities and communities), highlighting the positive effect of urban green areas while identifying areas with a higher potential for improvement (Lorenzo-Sáez et al., 2021 ). Finally, researchers have examined specific aspects of SDG 12 (i.e., responsible consumption and production through the appropriate use of resources and energy), e.g., waste minimization and increased investment in optimizing operating systems (Rodríguez-Antón et al., 2019 ; Schroeder et al., 2019 ; Dantas et al., 2021 ) and of SDG 13 (i.e., climate action).

In the present research context, some studies have linked SE enterprises with the achievement and development of SDGs and the 2030 Agenda and have explored these organizations’ strategies (Silva and Bucheli, 2019 ; Cis, 2020 ; Calabrese et al., 2021 ). It should be noted that the SDGs with the most important place in the SE model are SDG 1. End of poverty , SDG 7. Affordable and clean energy , SDG 10. Reduction of inequalities and SDG 13. Climate action . Conversely, Canales Gutiérrez ( 2022 ) highlights compliance with SDG 8. Decent work and economic growth, SDG 11. Sustainable cities and communities, and SDG 12. Responsible consumption and production .

Social enterprises are a source of regional development (Mozas and Bernal, 2006 ; Li and Espinach, 2020 ), particularly in depressed or rural areas (Ruíz, 2012 ; Flores, 2021 ), which allows us to affirm that they are effective tools for achieving the goals associated with SDG 1. End of poverty . These enterprises seek to end poverty as a mechanism that generates entrepreneurship in areas where entrepreneurship and gross capital formation are low (Chaves and Pérez, 2012 ; Khaskheli et al., 2020 ; Blind and Heb, 2023 ).

Concerning the link between social enterprises and SDG 8. Decent work and economic growth , we mentioned that by establishing regulations, social enterprises, particularly employment companies, originated in response to the 1970 crisis in order to maintain and guarantee employment. This is carried out by promoting associations between workers to create a joint company in which decision-making is carried out through a model that is as associative and democratic as possible (Rodríguez-Antón et al., 2019 ; Schroeder et al., 2019 ; Dantas et al., 2021 ). Cooperatives also stand out as a means to comply with SDG 8 (Cermelli and Llamosas Trápaga, 2021 ). In these types of enterprises, particularly in cooperatives and worker-owned companies, economic growth is linked to the capacity to generate employment associated with cooperative entrepreneurship among workers (Generelo, 2016 ; Melián and Campos, 2010 ; Kolade et al., 2022 ). Currently, business models frequently pursue twin objectives: The environmental improvement of society and job creation, often for people at risk of exclusion. Thus, the participation of SE enterprises in SDGs and CE-related activities implies concern for local community social issues that gain in relevance, as well as the involvement of governments in the development of green financial and regulatory incentives to support the CE-SDGs framework (Mies and Gold, 2021 ).