April 23, 2019

The Tragedy of the Tragedy of the Commons

The man who wrote one of environmentalism’s most-cited essays was a racist, eugenicist, nativist and Islamaphobe—plus his argument was wrong

By Matto Mildenberger

Garrett Hardin in 1972.

Bill Johnson Getty Images

This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

Fifty years ago, University of California professor Garrett Hardin penned an influential essay in the journal Science . Hardin saw all humans as selfish herders: we worry that our neighbors’ cattle will graze the best grass. So, we send more of our cows out to consume that grass first. We take it first, before someone else steals our share. This creates a vicious cycle of environmental degradation that Hardin described as the “tragedy of the commons.”

It's hard to overstate Hardin’s impact on modern environmentalism. His views are taught across ecology, economics, political science and environmental studies. His essay remains an academic blockbuster, with almost 40,000 citations . It still gets republished in prominent environmental anthologies .

But here are some inconvenient truths: Hardin was a racist, eugenicist, nativist and Islamophobe . He is listed by the Southern Poverty Law Center as a known white nationalist. His writings and political activism helped inspire the anti-immigrant hatred spilling across America today.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing . By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

And he promoted an idea he called “ lifeboat ethics ”: since global resources are finite, Hardin believed the rich should throw poor people overboard to keep their boat above water.

To create a just and vibrant climate future, we need to instead cast Hardin and his flawed metaphor overboard.

People who revisit Hardin’s original essay are in for a surprise. Its six pages are filled with fear-mongering. Subheadings proclaim that “freedom to breed is intolerable.” It opines at length about the benefits if “children of improvident parents starve to death.” A few paragraphs later Hardin writes: “If we love the truth we must openly deny the validity of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.” And on and on. Hardin practically calls for a fascist state to snuff out unwanted gene pools.

Or build a wall to keep immigrants out. Hardin was a virulent nativist whose ideas inspired some of today’s ugliest anti-immigrant sentiment. He believed that only racially homogenous societies could survive. He was also involved with the Federation for American Immigration Reform (FAIR), a hate group that now cheers President Trump’s racist policies. Today, American neo-Nazis cite Hardin’s theories to justify racial violence.

These were not mere words on paper. Hardin lobbied Congress against sending food aid to poor nations, because he believed their populations were threatening Earth’s “carrying capacity.”

Of course, plenty of flawed people have left behind noble ideas. That Hardin’s tragedy was advanced as part of a white nationalist project should not automatically condemn its merits.

But the facts are not on Hardin’s side. For one, he got the history of the commons wrong. As Susan Cox pointed out , early pastures were well regulated by local institutions. They were not free-for-all grazing sites where people took and took at the expense of everyone else.

Many global commons have been similarly sustained through community institutions. This striking finding was the life’s work of Elinor Ostrom, who won the 2009 Nobel Prize in Economics (technically called the Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel). Using the tools of science—rather than the tools of hatred—Ostrom showed the diversity of institutions humans have created to manage our shared environment.

Of course, humans can deplete finite resources. This often happens when we lack appropriate institutions to manage them. But let’s not credit Hardin for that common insight. Hardin wasn’t making an informed scientific case. Instead, he was using concerns about environmental scarcity to justify racial discrimination.

We must reject his pernicious ideas on both scientific and moral grounds. Environmental sustainability cannot exist without environmental justice. Are we really prepared to follow Hardin and say there are only so many lead pipes we can replace? Only so many bodies that should be protected from cancer-causing pollutants? Only so many children whose futures matter?

This is particularly important when we deal with climate change. Despite what Hardin might have said, the climate crisis is not a tragedy of the commons . The culprit is not our individual impulses to consume fossil fuels to the ruin of all. And the solution is not to let small islands in Chesapeake Bay or whole countries in the Pacific sink into the past, without a seat on our planetary lifeboat.

Instead, rejecting Hardin’s diagnosis requires us to name the true culprit for the climate crisis we now face. Thirty years ago, a different future was available. Gradual climate policies could have slowly steered our economy towards gently declining carbon pollution levels. The costs to most Americans would have been imperceptible.

But that future was stolen from us. It was stolen by powerful, carbon-polluting interests who blocked policy reforms at every turn to preserve their short-term profits. They locked each of us into an economy where fossil fuel consumption continues to be a necessity, not a choice.

This is what makes attacks on individual behavior so counterproductive. Yes, it’s great to drive an electric vehicle (if you can afford it) and purchase solar panels (if powerful utilities in your state haven’t conspired to make renewable energy more expensive). But the point is that interest groups have structured the choices available to us today. Individuals don’t have the agency to steer our economic ship from the passenger deck.

As Harvard historian Naomi Oreskes reminds us , “[abolitionists] wore clothes made of cotton picked by slaves. But that did not make them hypocrites … it just meant that they were also part of the slave economy, and they knew it. That is why they acted to change the system, not just their clothes.”

Or as Representative Alexandria Ocasio Cortez tweeted : “Living in the world as it is isn’t an argument against working towards a better future.” The truth is that two-thirds of all the carbon pollution ever released into the atmosphere can be traced to the activities of just ninety companies.

These corporations’ efforts to successfully thwart climate action are the real tragedy .

We are left with very little time. We need political leaders to pilot our economy through a period of rapid economic transformation, on a grand scale unseen since the Second World War. And to get there, we are going to have make sure our leaders listen to us, not—as my colleagues and I show in our research—fossil fuel companies.

Hope requires us to start from an unconditional commitment to one another, as passengers aboard a common lifeboat being rattled by heavy winds. The climate movement needs more people on this lifeboat, not fewer. We must make room for every human if we are going to build the political power necessary to face down the looming oil tankers and coal barges that send heavy waves in our direction. This is a commitment at the heart of proposals like the Green New Deal.

Fifty years on, let’s stop the mindless invocation of Hardin. Let’s stop saying that we are all to blame because we all overuse shared resources. Let’s stop championing policies that privilege environmental protection for some human beings at the expense of others. And let’s replace Hardin’s flawed metaphor with an inclusive vision for humanity—one based on democratic governance and cooperation in this time of darkness.

Instead of writing a tragedy, we must offer hope for every single human on Earth. Only then will the public rise up to silence the powerful carbon polluters trying to steal our future.

Locals at the Marienfluss Conservancy in Namibia meet to discuss conservation. Photo courtesy of NACSO/WWF Namibia

The miracle of the commons

Far from being profoundly destructive, we humans have deep capacities for sharing resources with generosity and foresight.

by Michelle Nijhuis + BIO

In December 1968, the ecologist and biologist Garrett Hardin had an essay published in the journal Science called ‘The Tragedy of the Commons’. His proposition was simple and unsparing: humans, when left to their own devices, compete with one another for resources until the resources run out. ‘Ruin is the destination toward which all men rush, each pursuing his own best interest,’ he wrote. ‘Freedom in a commons brings ruin to all.’ Hardin’s argument made intuitive sense, and provided a temptingly simple explanation for catastrophes of all kinds – traffic jams, dirty public toilets, species extinction. His essay, widely read and accepted, would become one of the most-cited scientific papers of all time.

Even before Hardin’s ‘The Tragedy of the Commons’ was published, however, the young political scientist Elinor Ostrom had proven him wrong. While Hardin speculated that the tragedy of the commons could be avoided only through total privatisation or total government control, Ostrom had witnessed groundwater users near her native Los Angeles hammer out a system for sharing their coveted resource. Over the next several decades, as a professor at Indiana University Bloomington, she studied collaborative management systems developed by cattle herders in Switzerland, forest dwellers in Japan, and irrigators in the Philippines. These communities had found ways of both preserving a shared resource – pasture, trees, water – and providing their members with a living. Some had been deftly avoiding the tragedy of the commons for centuries; Ostrom was simply one of the first scientists to pay close attention to their traditions, and analyse how and why they worked.

The features of successful systems, Ostrom and her colleagues found, include clear boundaries (the ‘community’ doing the managing must be well-defined); reliable monitoring of the shared resource; a reasonable balance of costs and benefits for participants; a predictable process for the fast and fair resolution of conflicts; an escalating series of punishments for cheaters; and good relationships between the community and other layers of authority, from household heads to international institutions.

When it came to humans and their appetites, Hardin assumed that all was predestined. Ostrom showed that all was possible, but nothing was guaranteed. ‘We are neither trapped in inexorable tragedies nor free of moral responsibility,’ she told an audience of fellow political scientists in 1997.

What Hardin had portrayed as a tragedy was, in fact, more like a comedy. While its human participants might be foolish or mistaken, they are rarely evil, and while some choices lead to disaster, others lead to happier outcomes. The story is far less predictable than Hardin thought, and its twists and turns can lead to uncomfortable places. But in those surprises lie the possibilities that Hardin never saw.

Y ou might think that scientists, and the public, would eagerly trade Hardin’s dark speculations about human nature for Ostrom’s sunnier findings about our capabilities. But as I learned while researching and writing my book Beloved Beasts (2021), a history of the modern conservation movement, Ostrom’s conclusions have faced stubborn resistance. During the early years of her career, colleagues criticised her for spending too much time studying the differences among systems and too little time looking for a unifying theory. ‘When someone told you that your work was “too complex”, that was meant as an insult,’ she recalled.

Ostrom insisted that complexity was as important to social science as it was to ecology, and that institutional diversity needed to be protected along with biological diversity. ‘I still get asked, “What is the way of doing something?” There are many, many ways of doing things that work in different environments,’ she told an audience in Nepal in 2010. ‘We have got to get to the point that we can understand complexity, and harness it, and not reject it.’

Her research gained global prominence in 2009, when, aged 76, Ostrom became the first woman to be awarded the Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences. But for a variety of reasons – perhaps because she was a woman in a male-dominated field, or perhaps because her sophisticated work didn’t lend itself to a catchy name – her carefully collected data hasn’t dislodged Hardin’s metaphor from the public imagination.

When Ostrom died in 2012, she was celebrated by her colleagues for her pioneering work, her plainspoken humility, and her steady resistance to what she called ‘panaceas’. She knew from experience how corrosive simple stories could be. Hardin, for his part, seemed bent on making his own ideas as repugnant as possible. Among his proposed solutions to the tragedy of the commons was coercive population control: ‘Freedom to breed is intolerable,’ he wrote in his 1968 essay, and should be countered with ‘mutual coercion, mutually agreed upon’. He feared not only runaway human population growth but the runaway growth of certain populations. What if, he asked in his essay, a religion, race or class ‘adopts overbreeding as a policy to secure its own aggrandisement’? Several years after the publication of ‘The Tragedy of the Commons’, he discouraged the provision of food aid to poorer countries: ‘The less provident and less able will multiply at the expense of the abler and more provident, bringing eventual ruin upon all who share in the commons,’ he predicted. He compared wealthy nations to lifeboats that couldn’t accept more passengers without sinking.

Hardin compared wealthy nations to lifeboats that couldn’t accept more passengers without sinking.

In his later years, Hardin’s racism became more explicit. ‘My position is that this idea of a multiethnic society is a disaster,’ he told an interviewer in 1997. ‘A multiethnic society is insanity. I think we should restrict immigration for that reason.’ Hardin died in 2003, but the nonprofit Southern Poverty Law Center, alert to the longevity of his ideas, maintains his profile in its ‘extremist files’ and classifies him as a white nationalist.

Still, many of those who abhor Hardin’s racist ideas – or would if they were aware of them – are seduced by the simplicity of his tragedy. If academic citation indexes are any guide, the tragedy of the commons remains far better known to scholars than any of Ostrom’s findings. It continues to be taught, uncritically, to high-school students in environmental science courses. It’s used as a justification by those who support severe restrictions on human immigration and reproduction. Even more frequently, it’s casually invoked as an explanation for human failures: even the eminent biologist E O Wilson, in his book Half-Earth (2016), describes the weakness of international climate-change agreements and the ongoing depletion of ocean resources as tragedies of the commons, without making clear that such tragedies can be averted.

Despite the evidence gathered by Ostrom and her colleagues, it seems, many are still all too willing to believe the worst of their fellow humans – to the detriment of conservation efforts worldwide. Like Hardin, many conservationists assume that humans can only be destructive, not constructive, and that meaningful conservation can be achieved only through total privatisation or total government control. Those assumptions, whether conscious or unconscious, close off an entire universe of alternatives.

W hile Ostrom’s ideas are not yet familiar maxims, they haven’t been ignored. In southern Africa in the 1980s, some conservationists recognised that parks and reserves, many created by colonial governments, had divided subsistence hunters and farmers from much of the wildlife that had long sustained them – and which, in some cases, they’d managed as a commons for generations. The resulting lack of local support meant that even the best-patrolled park boundaries were vulnerable to incursions by human neighbours, people unlikely to tolerate – much less protect – the large, sometimes troublesome species that ranged beyond even the largest reserves.

In response, new initiatives attempted to redistribute the burdens and benefits of conservation: the Communal Areas Management Programme for Indigenous Resources (CAMPFIRE) project in Zimbabwe directed revenue from hunting and tourism on communal lands to district councils, incentivising those councils and their communities to control illegal hunting. In neighbouring Zambia, the Administrative Management Design (ADMADE) programme trained local people as wildlife rangers, then transferred some wildlife management responsibilities, and benefits, from the national government to community boards. These and similar efforts became known as community-based conservation.

In 1987, when the South African conservationist Garth Owen-Smith attended a conference on community-based conservation in Zimbabwe, a comment by Harry Chabwela, the director of Zambia’s national parks, left a lasting impression. ‘At this conference we have talked a lot about giving local people this and giving them that, but what has been forgotten is that they also want power,’ Chabwela said. ‘They want a say over the resources that affect their lives. That is more important than money.’

Owen-Smith had already spent years living in Namibia, which was controlled by South Africa and known as South West Africa. When severe drought and an epidemic of illegal hunting threatened livelihoods and wildlife in the territory’s northwestern desert in the early 1980s, Owen-Smith had supported the creation of a system of community game guards. The unarmed guards – many of whom were hunters themselves – were so effective at tracking illegal hunters that, after a few years, the killing of elephants and rhinos in the region stopped completely. Antelope numbers improved so much that Owen-Smith was able to persuade the national conservation department to reopen limited game hunting in the area – a development much appreciated by locals.

Chabwela’s comment about power motivated Owen-Smith to think bigger. When he returned home, he and his partner Margaret Jacobsohn began to talk with community leaders and members about ways of restoring some local authority over wildlife. After Namibia won independence from South Africa in 1990, the new government recruited Jacobsohn and Owen-Smith to survey rural attitudes toward conservation, and the survey confirmed what the two had by then been hearing for years: most people didn’t want the occasionally dangerous species they lived with to be killed or removed – but they did, as Chabwela had suggested, want a say in their management. In 1996, the Namibian National Assembly passed a law that allowed groups of people living on communal land to establish institutions called conservancies. Conservancies would be governed by elected committees, and all members would share the benefits of any tourism or commercial hunting within conservancy boundaries.

Trophy hunters are sometimes directed toward lions and elephants who have become aggressive toward people.

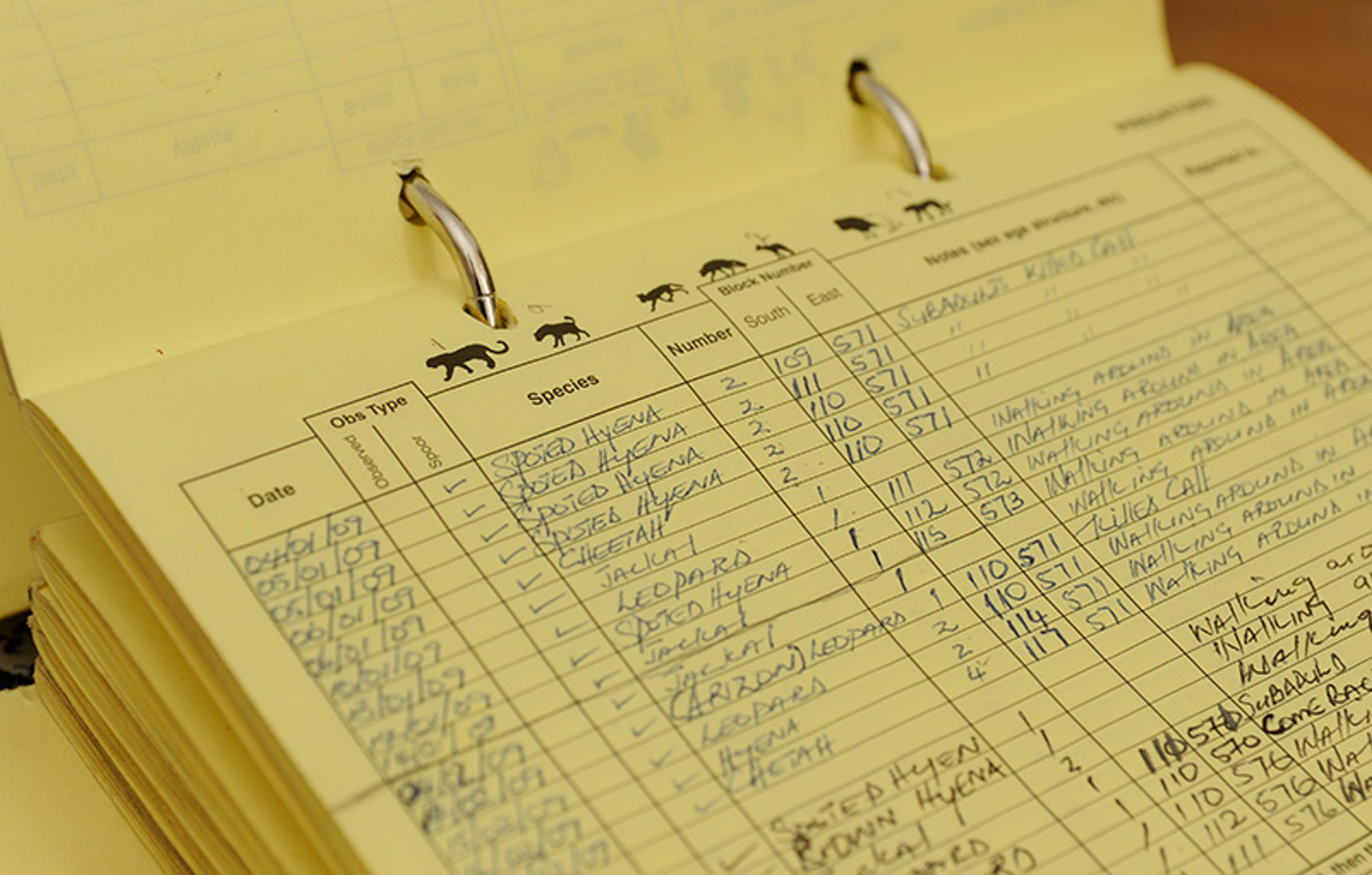

The first conservancies on communal land were formalised in 1998, and there are now more than 80 of them in Namibia. They cover more than 40 million acres of land, and stretch from the northwestern desert to the humid, densely populated Zambezi Region in the northeast. They earn revenue from lodges, campgrounds and guide services, both as partners in joint ventures and as solo operators. They participate in annual surveys of game and wildlife populations and, in cooperation with the national conservation ministry, set quotas for both subsistence and commercial hunting within their boundaries. They employ their own game guards, who are currently fending off a continent-wide wave of rhino poaching driven by Asian demand for powdered rhino horn (a discredited traditional medicine). And, every year, the members of each conservancy assemble to call their governing committees to account.

In August 2019, I attended the general meeting of Orupembe Conservancy, held in an open-air pavilion on the outskirts of Onjuva, a tiny town hundreds of miles from the nearest gas station, and even further from a paved road. Most of the people at the meeting were semi-nomadic herders, many of whom had travelled long distances from even more isolated corners of the conservancy. (I was present thanks to the expert off-road driving skills of the guide Edison Kasupi, who grew up in nearby Purros Conservancy.) When the Onjuva committee called the meeting to order, there were 95 people seated inside the pavilion, about half of the conservancy members and just enough for a quorum. The chairman Henry Tjambiru commented that the current drought had forced many people to take their herds further afield, preventing them from attending.

Orupembe Conservancy has several sources of income, all relatively modest: a campsite, a small lodge that it co-owns with two other conservancies, and contracts with a handful of hunting guides. (Some conservancies have very little income, and fund their operations with donations from international conservation groups; others, such as the neighbouring Marienfluss Conservancy, have joint venture agreements with upscale lodges that can net more than $100,000 a year in salaries and fees.)

After a review of the year’s earnings, the committee distributed a list of local species and the current hunting quotas for each. Because the drought had worsened since the quotas were set, conservancy members had voluntarily left most of them unfilled. While wildlife surveys earlier in the year had suggested that 75 oryx could be killed without harming the population, for example, only three had been shot so far. The meat from two of those was currently boiling in a nearby row of pots, about to be served for lunch.

The meeting, which lasted several hours, was disrupted by procedural inefficiencies, lively sideline arguments and, at one point, an accusation of petty corruption. But as the sun sank and the meeting came to a ragged end, I realised with surprise that I was exhilarated. During an exceptionally difficult year, these conservancy members had taken the trouble to travel to the meeting, consider the long-term future of other species, and recommit themselves to ensuring it.

I n reviving the commons, the Namibian conservancies have revived the relationships between people and wildlife – and the results, as Ostrom would be unsurprised to learn, are complex. Where parks and reserves separate land into clearly defined categories, community-based conservation proposes that land can be simultaneously protected and utilised – through the cooperative efforts of the people who live on it. It’s a profound challenge to Hardin’s assumptions, and while some of its outcomes are easy to applaud – the recovery of elephants and rhinos, the arrival of new jobs – others make outsiders squirm.

John Kasaona, who grew up in northwestern Namibia and, as a boy, watched Owen-Smith and his father set out on game-guard patrols, is now the executive director of Integrated Rural Development and Nature Conservation, a nonprofit organisation that provides technical support to the conservancies. When he travels overseas to talk about the accomplishments of the Namibian conservancy system, he mentions only briefly, if at all, that its success depends in part on income from trophy hunters – tourists who pay for the privilege of shooting an animal for sport, and who in some cases keep hides or horns for display. For many conservancies, trophy hunting is not only a source of income but a tool for preserving the peace between humans and other species, since trophy hunters are sometimes directed toward individual lions or elephants who have become aggressive toward people.

Kasaona is well aware of the images that trophy hunting conjures in his listeners’ minds: Theodore Roosevelt standing next to a fallen elephant, dwarfed by the carcass and its upturned tusks; Eric Trump grinning as he hefts the limp body of a leopard, his brother Don Jr beside him; the Zimbabwean lion named Cecil, whose illegal killing by a dentist from Minnesota during a guided hunt in 2015 caused a global outcry. For some in North America and Europe, trophy hunting in Africa has come to symbolise human sins against other species.

In 2017, after Kasaona spoke at a Smithsonian Institution conference in Washington, DC, a young woman stood to speak at the audience microphone. ‘I think that some pieces were missing from the presentation,’ she began. Kasaona had not shown images of the animals slain by trophy hunters, she said. He had neglected to mention that the lion or elephant spotted by a visiting family on safari might be killed the next day. Kasaona, at the podium, acknowledged the international controversy over trophy hunting, but said that regulated commercial hunts remained an important source of revenue for the Namibian conservancies. There was more to say, but the session was over, and any further discussion was washed away by chatter.

Even in the darkest times, Ostrom’s work reminds us that the future is unpredictable and full of opportunity.

More than two years later, I met up with Kasaona in the town of Swakopmund, about halfway down the Namibian coast. We talked over generous plates of springbok curry at the colonial-era Hansa Hotel, where German is spoken more frequently than English, and both are far more common than any of Namibia’s 20-plus Indigenous languages and dialects.

I asked Kasaona to finish answering his questioner at the Smithsonian conference. ‘People say: “I don’t like what they’re doing to animals,” but most of them wouldn’t want to live next to a lion that could harm their family,’ he said. The majority of tourists who hunt for sport in Namibia pursue more common species such as springbok, whose hunting is permitted through the conservancy quota system. In the case of globally threatened species, the number of animals (if any) that can be shot each year is set by the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES). In 2004, the parties to the convention approved applications by Namibia and South Africa to allow limited hunting of black rhinos, determining that the population had recovered to the point that five male rhinos could be shot in each country each year. In Namibia, the national conservation ministry chooses which rhinos will be hunted – usually older animals that have become aggressive or territorial – and issues permits for the hunts. The permit fee is deposited in a national conservation trust fund, and in one recent case a hunter paid $400,000 to shoot a single male rhino, far more than most conservancies earn in a year.

The trophy-hunting system in Namibia isn’t perfect, Kasaona acknowledges – there are cases where hunters have killed the wrong animal – but over the long term, he said, it benefits both the conservancies and the species in question by reducing conflicts between people and wildlife. When international conservation groups promise to regulate and censure trophy hunting out of existence, Kasaona hears what he calls ‘another kind of colonisation’ – a violation of the local authority that he and others have spent decades building up, and a threat to the revenue it depends on. ‘What do they say to the people whose livelihood depends on what they are trying to ban?’ he says.

Global restrictions on trophy hunting, Kasaona argues, are a simplistic response to a complex situation – what Ostrom might call a panacea. Not all countries are alike; not all conservancies are alike; not all conservancy members are alike; not even all trophy hunters are alike. And a few individual lions and elephants are far more dangerous than others, as those who have lost loved ones and livelihoods to rogue animals can attest.

While those viral images of trophy hunters with carcasses might all seem to say the same thing, they don’t. Some, surely, are symbols of corruption or needless violence. But, in the best cases, they’re examples of sustainable utilisation: colonial nostalgia, harnessed by the formerly colonised to further multispecies survival.

O strom’s principles of commons management now underlie not only the Namibian conservancy system but hundreds of similar efforts throughout the world. Many have revived and adapted conservation practices developed centuries ago, developing new rules suited to current circumstances. Their creators cooperate in the management of coral reefs in Fiji, highland forests in Cameroon, fisheries in Bangladesh, oyster farms in Brazil, community gardens in Germany, elephants in Cambodia, and wetlands in Madagascar. They operate in thinly populated deserts, crowded river valleys, and abandoned urban spaces.

While conservation almost always carries at least some short-term costs, researchers have found that many community-based conservation projects reduce those costs and, over time, deliver significant benefits to their human participants, tangible and intangible alike. And while community-based conservation began as a reaction to top-down conservation strategies, it can operate in parallel with large parks and reserves – and even foster their creation. In northwestern Namibia, two neighbouring conservancies have proposed to establish a ‘people’s park’ where livestock would be excluded and tourist numbers would be limited by a permit system, allowing lions and other large predators to more easily avoid conflicts with humans. Should the national legislature approve the conservancies’ proposal, the region could serve as a core habitat from which large carnivores can range in relative safety – since the region’s biological diversity is now protected not only by law, but by supportive human neighbours.

Community-based conservation can’t solve everything, and it doesn’t always succeed in protecting the commons. In many cases, national governments don’t recognise the longstanding land claims of Indigenous and other rural communities, creating uncertainty that interferes with community efforts to manage for the long term. Even well-established systems are vulnerable to internal conflict, and to external pressures ranging from drought to war to global market forces. As Ostrom often reminded her audiences, any strategy can succeed or fail. Community-based conservation is distinctive because many societies have only begun to understand – or remember – its potential. ‘What we have ignored is what citizens can do,’ she said.

At Indiana, Ostrom and her husband Vincent, also a political scientist, founded the Workshop in Political Theory and Policy Analysis, affectionately known as ‘The Workshop’ to the researchers who continue to gather there. Current students of commons management struggle, as Ostrom did, with the difficulty of managing large-scale resource problems such as air pollution at the community level. They wrestle with the implications of her findings for the digital landscape, where the veneration of open access often collides with Ostrom’s definition of the commons as a boundaried, regulated space. And despite what one researcher in 2011 dubbed ‘Ostrom’s Law’ – that whatever works in practice can work in theory – even Ostrom’s admirers sometimes echo her earliest critics, lamenting that the field lacks an overarching theory.

The challenge of understanding the complexity of all species continues, as does the challenge of seeing possibility in what so often looks like a collective tragedy. But even in the darkest times, Ostrom’s work can remind us that the future is deliciously unpredictable, and full of opportunities for us to stumble away from the edge.

This original essay draws on the book ‘Beloved Beasts: Fighting for Life in an Age of Extinction’ (2021) by Michelle Nijhuis, published by W W Norton & Co.

Stories and literature

On Jewish revenge

What might a people, subjected to unspeakable historical suffering, think about the ethics of vengeance once in power?

Shachar Pinsker

Building embryos

For 3,000 years, humans have struggled to understand the embryo. Now there is a revolution underway

John Wallingford

Design and fashion

Sitting on the art

Given its intimacy with the body and deep play on form and function, furniture is a ripely ambiguous artform of its own

Emma Crichton Miller

Learning to be happier

In order to help improve my students’ mental health, I offered a course on the science of happiness. It worked – but why?

Consciousness and altered states

How perforated squares of trippy blotter paper allowed outlaw chemists and wizard-alchemists to dose the world with LSD

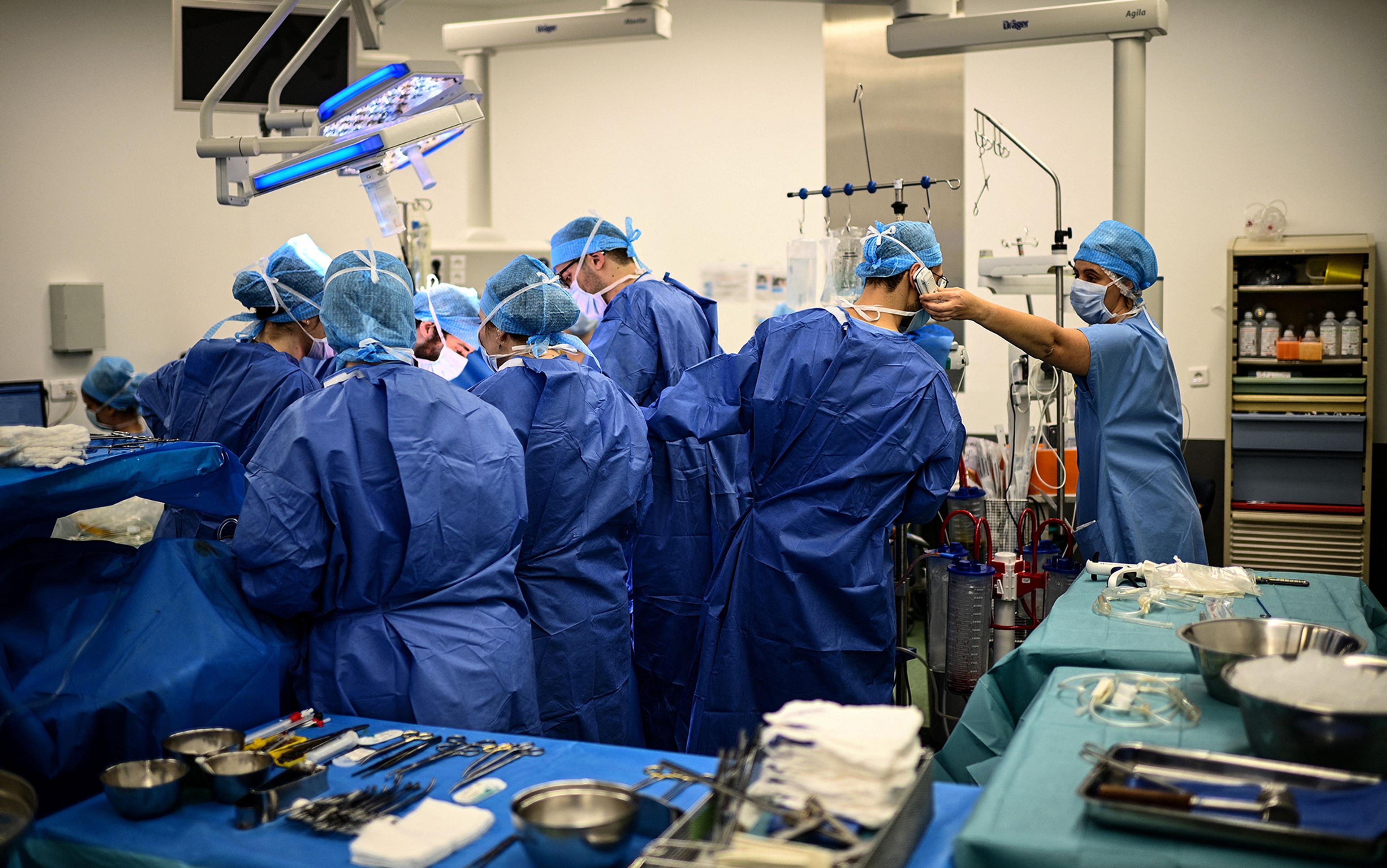

Last hours of an organ donor

In the liminal time when the brain is dead but organs are kept alive, there is an urgent tenderness to medical care

Ronald W Dworkin

Tragedy of the Commons Analytical Essay

The “tragedy of the commons” idea was first brought to fore by Garrett Hardin. By it, Hardin refers to a scenario where selfish utilization of resources by an individual ends up having negative effects on the entire community. People have various private and selfish needs that they seek to satisfy at any given moment. On the other hand, the community as a whole has collective interests which may not necessarily be the same as individual needs (Manning 32).

In this regard, the way one person will want to use certain resources may not be in the best interest of the group as a whole. In his view, people should be regulated in that how they use various resources so that society at large can benefit. Tragedy of the commons affects continuity of life in an ecosystem. Hardin refers to common resources whose unregulated consumption can affect the community negatively (Hetzel 3).

According to Hardin, common resources should be regulated so as to ensure that their consumption is beneficial to the community as a whole. Tragedy of the commons occurs because people are given too much freedom when it comes to making choices about resource utilization. In his view, if a common resource is used while taking into consideration the collective interests of a community, each individual will benefit (Manning 112). Tragedy of the commons can lead to overuse of various resources and inability of an ecosystem to sustain itself.

It is important to note that tragedy of the commons is catastrophic to the community if it is allowed to happen. Depletion of one resource can lead to extinction of various organisms. I disagree with Hardin on his argument that tragedy of the commons is a problem with no technical solution, as the solution to tragedy of the commons calls for both technical and non-technical approaches.

It should be noted that for tragedy of the commons to be avoided, values and believes of people must be changed (Dauvergne 223). People should learn the virtue of sharing and avoid egocentric desires for the benefit of everybody in the society. To achieve this, the change of moral values in individuals will be required.

Nonetheless, one cannot be prevented from using a given resource if he or she is not given a substitute (Hetzel 9). Therefore, tragedy of the commons requires a technological solution in order to be averted. To ensure sustainable energy sources in the future we have to come up with renewable sources of energy and embrace them.

Notably, common resources have to be utilized albeit in a manner that serves the interests of the whole community. It is important to note that there are circumstances when it is acceptable to use common resources without necessarily depleting them. One of the ways is when the rate of consumption is lower than the rate of replacement or renewal (Manning 134). This will ensure that resources are saved for future generations.

Moreover, if there are regulations that control utilization of common resources, then their depletion can be put under control. Any resource will be depleted if it is over used and control is necessary. Also when societal interests are put first before the individual interests, utilization of communal resources would be reasonable (Dauvergne 256). These can be achieved through regulation or by exhorting people to change their values. These circumstances can help avert the tragedy of the commons.

Works Cited

Dauvergne, Peter. Handbook of Global Environmental Politics . Northampton: Edward Elgar Publishing, 2005. Print.

Hetzel, Julia. To What Extent is the Tragedy of the Commons Restricting Option When Dealing with a Gloabal Ecological Crisis . Munchen: GRIN Verlag, 2011. Print.

Manning, Robert E. Parks and Carrying Capacity: Commons Without Tragedy . Washington: Island Press, 2007. Print.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2019, June 11). Tragedy of the Commons. https://ivypanda.com/essays/tragedy-of-the-commons/

"Tragedy of the Commons." IvyPanda , 11 June 2019, ivypanda.com/essays/tragedy-of-the-commons/.

IvyPanda . (2019) 'Tragedy of the Commons'. 11 June.

IvyPanda . 2019. "Tragedy of the Commons." June 11, 2019. https://ivypanda.com/essays/tragedy-of-the-commons/.

1. IvyPanda . "Tragedy of the Commons." June 11, 2019. https://ivypanda.com/essays/tragedy-of-the-commons/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Tragedy of the Commons." June 11, 2019. https://ivypanda.com/essays/tragedy-of-the-commons/.

- Natural Selection by Charles Darwin: Comparative Analysis

- Shadow Assignment, The Presentation Technique by Thompson

- Can Conscience Save Us?

- “The Future of Life” by Edward O. Wilson

- “Silent Spring” by Rachel Carson

- World Bank’s Transformation of Human-Environmental Relations in the Global South

- Effects of Lead and Lead Compounds on Soil, Water, and Air

- E-Waste Management Plan for Melbourne School

Want a daily email of lesson plans that span all subjects and age groups?

What is the tragedy of the commons - nicholas amendolare.

2,965,836 Views

54,233 Questions Answered

Let’s Begin…

Is it possible that overfishing, super germs, and global warming are all caused by the same thing? In 1968, a man named Garrett Hardin sat down to write an essay about overpopulation. Within it, he discovered a pattern of human behavior that explains some of history’s biggest problems. Nicholas Amendolare describes the tragedy of the commons.

About TED-Ed Animations

TED-Ed Animations feature the words and ideas of educators brought to life by professional animators. Are you an educator or animator interested in creating a TED-Ed Animation? Nominate yourself here »

Meet The Creators

- Educator Nicholas Amendolare

- Director Lisa LaBracio

- Script Editor Eleanor Nelsen

- Composer Nicolas Martigne

- Animator Lisa LaBracio

- Background Artist Tara Sunil Thomas

- Clean Up Animator Tara Sunil Thomas

- Associate Producer Jessica Ruby

- Content Producer Gerta Xhelo

- Editorial Producer Alex Rosenthal

- Narrator Addison Anderson

More from How Things Work

How do gas masks actually work?

Lesson duration 04:31

417,426 Views

This piece of paper could revolutionize human waste

Lesson duration 05:35

2,533,419 Views

Why can't you put metal in a microwave?

Lesson duration 05:49

918,173 Views

This is what happens when you hit the gas

Lesson duration 06:05

717,720 Views

- Phone This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

- Climate Change

- Policy & Economics

- Biodiversity

- Conservation

Get focused newsletters especially designed to be concise and easy to digest

- ESSENTIAL BRIEFING 3 times weekly

- TOP STORY ROUNDUP Once a week

- MONTHLY OVERVIEW Once a month

- Enter your email *

- Email This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

Explainer: What Is the ‘Tragedy of the Commons’?

First posited in 1968 by American ecologist Garret Hardin, the Tragedy of the Commons describes a situation where shared environmental resources are overused and exploited, and eventually depleted, posing risks to everyone involved. Hardin argues that to prevent this, there should be some restrictions to the amount of usage, for example, property rights must be affixed.

What Is the Tragedy of the Commons?

The definition of the Tragedy of the Commons is an economic and environmental science problem where individuals have access to a shared resource and act in their own interest, at the expense of other individuals. This can result in overconsumption, underinvestment, and depletion of resources.

Garrett Hardin, an evolutionary biologist, wrote a paper called “The Tragedy of the Commons” in the journal Science in 1968. In summary of the Hardin paper, the Tragedy of the Commons addressed the growing concern of overpopulation, and Hardin used an example of sheep grazing land when describing the adverse effects of overpopulation. In this case, grazing lands held as private property will see their use limited by the prudence of the land holder in order to preserve the value of the land and health of the herd. Grazing lands held in common will become over-saturated with livestock because the food the animals consume is shared among all herdsmen.

Hardin argues that individual short-term interest – to take as much of a resource as possible – is in opposition to societal good. If everyone was to act on this individual interest, the situation would worsen for society as a whole- demand for a shared resource would overshadow the supply, and the resource would eventually become entirely unavailable.

Conversely, exercising restraint would yield benefits for all in the long-term, as the shared resource would remain available.

Tragedy of the Commons: Examples

Arguably the best examples of Tragedy of the Commons occur in situations that lead to environmental degradation.

Among many things, pollution is caused by wastewater. As the number of households and companies increase and dump their waste into the water, the water loses its ability to clean itself. This results in water that is toxic to wildlife and the people that live around and rely on it.

Overfishing

Another example of the Tragedy of the Commons lies in overfishing. In Canada, the Grand Banks fishery off the coast of Newfoundland was a means of livelihood for regional fishermen. Abundant in cod, the fishery allowed fishermen to catch as many cod as they desired without negatively impacting their population.

Then, in the 1960s, advancements in technology allowed fishermen to catch vast quantities of cod, far more than before. However, with each passing season, the amount of cod deteriorated and by the 1990s, the fishing industry in the region collapsed because there wasn’t enough fish to go around. This situation where individual fishermen took advantage of opportunities to benefit themselves in the short term, even when their actions were clearly detrimental to society in the long term, encapsulates the self-preserving mindset behind the Tragedy of the Commons. These fishermen thought logically, but not collectively, which led to their downfall.

The Tragedy of the Commons can also be applied to the COVID-19 pandemic. In its early days, people were generally wary of mixing with anyone outside their immediate family, leaving their homes less and working from home. However, another result of the pandemic was that people began to stock up on food and utilities. People likely assumed that everyone else would stock up as well and so the only solution was to preempt this scenario and stockpile food before the next person could. Again, people were thinking logically, but not collectively, and herein lies the relevance of the Tragedy of the Commons. Individuals took advantage of opportunities that benefited themselves, but spread out the harmful effects of their consumption across society.

Retailers responded by imposing restrictions on the number of items one could buy, but it was too late. Entire grocery aisles were empty, wiped clean.

You might also like: Carbon Tax: A Shared Global Responsibility For Carbon Emissions

What About the Environment?

Shared resources that mitigate the impacts of the climate crisis are abused constantly.

No single authority can pass laws that protect the entire ocean. Each country can only manage and protect the ocean resources along its coastlines, leaving the shared common space beyond any particular jurisdiction vulnerable to pollution. This has led to obscene amounts of ocean pollution, as seen in garbage patches that accumulate in the centre of circular currents, for example. This will affect everyone as these pollutants cycle through the marine food chain, and then humans as we consume fish. Another problem facing the oceans are dead zones , areas in lakes and oceans where no marine life can live because of the lack of oxygen caused by excessive pollution and fertiliser runoff.

The atmosphere is another resource being used and abused, as are forests. Unregulated and illegal logging pose great risks to forests’ ability to store carbon. In some parts of the world, vast expanses of rainforests aren’t governed in a way that allows effective management for resource extraction. Timber producers are driven to take as much timber as possible as cheaply as possible, without considering the wider impacts of doing so.

Poor governance exacerbates the problem of the Tragedy of the Commons.

Who Is Meant to Fix It?

Ideally, governments at the local, state, national and international levels would define and manage shared resources . However, there are problems with this. Management inside clear boundaries is quite straightforward, but more problematic are resources shared across jurisdictions. For example, at the international level, states are not bound by a common authority and may view restrictions on resource extraction as a threat to their sovereignty. Additionally, more difficulties arise when resources cannot be divided, such as in whale treaties when the fishing of the whales’ food source is separately regulated.

Economist Scott Barrett at Columbia University in New York says that international law “has no teeth, so treaties are essentially voluntary. “Even when countries decide to take part in collective conservation efforts, they can simply pull out again when they want to,” as Canada did in 2011 when it pulled out of the Kyoto Protocol and when America withdrew from the Paris Agreement in late 2019 – though they rejoined shortly in the following year by the Biden Administration.

As the global population increases and demand for resources follows, the downsides of the Commons become more apparent. Some may argue that this will test the role and practicality of nation-states, leading to a redefinition of international governance. Further, it may lead some to question the role of supranational governments, such as the UN or the World Trade Organization; as resources become more limited, some may argue that managing the commons may not have a solution at all.

What Can Be Done?

A potential solution to this is to affix property rights to public spaces. For example, charging a toll to use a freeway or implementing a tax for dumping wastewater would reduce the number of users to those who act in the best interests of others, not only themselves. Other solutions could include government intervention or developing strategies to trigger collective behaviour, such as assigning small groups in a community a plot of land to look after.

Overall, regulating consumption and use can reduce over-consumption and government investment in conservation and renewal of the resource can help prevent its depletion.

Featured image by: Matteo de Mayda

This story is funded by readers like you

Our non-profit newsroom provides climate coverage free of charge and advertising. Your one-off or monthly donations play a crucial role in supporting our operations, expanding our reach, and maintaining our editorial independence.

About EO | Mission Statement | Impact & Reach | Write for us

15 Biggest Environmental Problems of 2024

Water Shortage: Causes and Effects

International Day of Forests: 10 Deforestation Facts You Should Know About

Hand-picked stories weekly or monthly. We promise, no spam!

Boost this article By donating us $100, $50 or subscribe to Boosting $10/month – we can get this article and others in front of tens of thousands of specially targeted readers. This targeted Boosting – helps us to reach wider audiences – aiming to convince the unconvinced, to inform the uninformed, to enlighten the dogmatic.

- Business Essentials

- Leadership & Management

- Credential of Leadership, Impact, and Management in Business (CLIMB)

- Entrepreneurship & Innovation

- Digital Transformation

- Finance & Accounting

- Business in Society

- For Organizations

- Support Portal

- Media Coverage

- Founding Donors

- Leadership Team

- Harvard Business School →

- HBS Online →

- Business Insights →

Business Insights

Harvard Business School Online's Business Insights Blog provides the career insights you need to achieve your goals and gain confidence in your business skills.

- Career Development

- Communication

- Decision-Making

- Earning Your MBA

- Negotiation

- News & Events

- Productivity

- Staff Spotlight

- Student Profiles

- Work-Life Balance

- AI Essentials for Business

- Alternative Investments

- Business Analytics

- Business Strategy

- Business and Climate Change

- Design Thinking and Innovation

- Digital Marketing Strategy

- Disruptive Strategy

- Economics for Managers

- Entrepreneurship Essentials

- Financial Accounting

- Global Business

- Launching Tech Ventures

- Leadership Principles

- Leadership, Ethics, and Corporate Accountability

- Leading Change and Organizational Renewal

- Leading with Finance

- Management Essentials

- Negotiation Mastery

- Organizational Leadership

- Power and Influence for Positive Impact

- Strategy Execution

- Sustainable Business Strategy

- Sustainable Investing

- Winning with Digital Platforms

Tragedy of the Commons: What It Is and 5 Examples

- 06 Feb 2019

Have you ever thought about the environmental impact of the items used in your daily life? Are they harming the environment? Perhaps they have a positive effect. For some individuals, this may be the reason they chose these items in the first place.

Yet, this isn’t always the case. What if the production or use of your favorite products threatens the ecosystem? Or worse, what if your consumption threatens the very existence of those products?

While this notion may seem implausible, it turns out there are many goods that are being produced unsustainably, endangering resources, or negatively impacting the environment.

What Is the Tragedy of the Commons?

The tragedy of the commons refers to a situation in which individuals with access to a public resource (also called a common) act in their own interest and, in doing so, ultimately deplete the resource.

This economic theory was first conceptualized in 1833 by British writer William Forster Lloyd. In 1968, the term “tragedy of the commons” was used for the first time by Garret Hardin in Science Magazine .

This theory explains individuals’ tendency to make decisions based on their personal needs, regardless of the negative impact it may have on others. In some cases, an individual’s belief that others won’t act in the best interest of the group can lead them to justify selfish behavior. Potential overuse of a common-pool resource—hybrid between a public and private good— can also influence individuals to act with their short-term interest in mind, resulting in the use of an unsustainable product and disregard the harm it could cause to the environment or general public.

It’s helpful for both firms and individuals to understand the tragedy of the commons so they can make more sustainable and environmentally-friendly choices. Here are five real-world examples of the tragedy of the commons and an exploration of the solution to this problem.

Check out our video on the tragedy of the commons below, and subscribe to our YouTube channel for more explainer content!

5 Tragedy of the Commons Examples

1. coffee consumption.

While a simple cup of coffee might seem harmless, coffee consumption is a prime example of the tragedy of the commons. Coffee plants are a naturally occurring shared resource, but overconsumption has led to habitat loss endangering 60 percent of the plants' species —including the most commonly brewed Arabica coffee.

2. Overfishing

As the global population continues to rise, the food supply needs to increase just as quickly. However, overhunting and overfishing have the potential to push many species into extinction. For example, overfishing of the Pacific bluefin tuna has caused an all-time population low of approximately three percent of their original population. This not only endangers the Pacific bluefin tuna, but also risks further marine ecosystem endangerment as a result.

3. Fast Fashion

Overproduction by fashion brands has created extreme product surplus to the point that luxury brand Burberry burnt $37.8 million worth of its 2018 season’s leftovers to avoid offering a discount on unsold wares. Furthermore, as new trends emerge rapidly within social networks on the Internet and social media, consumers are constantly purchasing new clothing items and disposing of old, out-of-trend items that ultimately end up in landfills and contribute to pollution.

4. Traffic Congestion

Traffic congestion is one of the best-known modern examples of the tragedy of the commons. According to a study by the Harvard School of Public Health , air pollution from traffic congestion in urban areas contributes to more than 2,200 premature deaths annually in the United States alone. As more people decide that roads and highways are the fastest way to travel to work, more cars end up on the roads, ultimately slowing down traffic and polluting the air.

5. Groundwater Use

In the United States, groundwater is the source of drinking water for about half the population, and roughly 50 billion gallons are used each day for agriculture. Because of this, groundwater supply is decreasing faster than it can be replenished. In drought-prone areas, the risk for water shortage is high and restrictions are often put in place to mitigate it. Some individuals, however, ignore water restrictions and the supply ultimately becomes smaller for everyone.

Related: The Parlor Room Podcast: HBS Professor Forest Reinhardt on Climate Change and the Tragedy of the Commons

How Can the Tragedy of the Commons Be Avoided?

How would you react to discovering that your consumption habits are depleting natural resources? You have two primary options: finding alternative, sustainable products and preventing overconsumption.

Finding Alternative and Sustainable Products

To drive change and avoid the tragedy of the commons, it’s important to boycott the products or brands causing the alleged harm and search for alternatives. Finding sustainable options, rather than carrying on with what Sustainable Business Strategy Professor Rebecca Henderson calls, “business as usual,” directly addresses the impact of your consumption habits. Unfortunately this response has not grown in popularity, since many consumers feel boycotting a product won’t make a large enough impact to make a difference.

The tragedy of the commons shows us how, without some sort of regulation or public transparency of choices and actions associated with public goods, there's no incentive for individuals to hold themselves back from taking too much. In fact, individuals may even have a “use it or lose it” mentality; if they’re aware of the inevitability that the good itself will be depleted, they may think, “I better get my share while I still can.”

Related: What Does "Sustainability" Mean in Business?

Preventing Overconsumption

You’ve likely encountered examples of the tragedy of the commons in your everyday life; these hypothetical scenarios can offer insight into how to prevent the overconsumption of resources. Consider how you’d respond in the following scenarios:

- If everyone in your community abides by the town’s lawn-watering regulations, you're more likely to follow them as well. Who wants a bright green lawn while the rest of the town's lawns are brown?

- No one wants to pay a premium for something they’ll likely throw away or use as a trash bag. Charging for grocery bags raises the stakes, because it involves the customer’s bottom line. Chances are, this change will lead you to keep reusable bags in your car, just in case you need to stop at the grocery store on the way home.

These examples show how, when faced with a public good, individuals can be motivated to cooperate through monetary or moral incentives or penalties. What’s truly fascinating is that this also holds true on a larger scale.

Remember the previous example of luxury fashion brands burning surplus clothing? Well, Burberry—having heard its customers’ reactions to the burning of inventory, regardless of how sustainably its products were disposed of—has since pledged to stop burning clothes and using real fur.

Developing a Sustainable Mindset

It’s easy for both individuals and organizations to fall victim to the tragedy of the commons. However, it doesn’t have to be this way. By developing a more sustainable mindset , you can become better aware of the long-term impact that your short-term choices have on the environment both in your personal life and at work.

Are you interested in learning more? Explore our Sustainable Business Strategy course and other business in society courses to discover how you can make a difference and become a purpose-driven leader.

This post was updated on August 17, 2022. It was originally published on February 6, 2019.

About the Author

- Liberty Fund

- Adam Smith Works

- Law & Liberty

- Browse by Author

- Browse by Topic

- Browse by Date

- Search EconLog

- Latest Episodes

- Browse by Guest

- Browse by Category

- Browse Extras

- Search EconTalk

- Latest Articles

- Liberty Classics

- Book Reviews

- Search Articles

- Books by Date

- Books by Author

- Search Books

- Browse by Title

- Biographies

- Search Encyclopedia

- #ECONLIBREADS

- College Topics

- High School Topics

- Subscribe to QuickPicks

- Search Guides

- Search Videos

- Library of Law & Liberty

- Home /

ECONLIB CEE

Tragedy of the Commons

By garrett hardin.

By Garrett Hardin,

I n 1974 the general public got a graphic illustration of the “tragedy of the commons” in satellite photos of the earth. Pictures of northern Africa showed an irregular dark patch 390 square miles in area. Ground-level investigation revealed a fenced area inside of which there was plenty of grass. Outside, the ground cover had been devastated.

The explanation was simple. The fenced area was private property, subdivided into five portions. Each year the owners moved their animals to a new section. Fallow periods of four years gave the pastures time to recover from the grazing. The owners did this because they had an incentive to take care of their land. But no one owned the land outside the ranch. It was open to nomads and their herds. Though knowing nothing of Karl Marx , the herdsmen followed his famous advice of 1875: “To each according to his needs.” Their needs were uncontrolled and grew with the increase in the number of animals. But supply was governed by nature and decreased drastically during the drought of the early 1970s. The herds exceeded the natural “carrying capacity” of their environment, soil was compacted and eroded, and “weedy” plants, unfit for cattle consumption, replaced good plants. Many cattle died, and so did humans.

The rational explanation for such ruin was given more than 170 years ago. In 1832 William Forster Lloyd, a political economist at Oxford University, looking at the recurring devastation of common (i.e., not privately owned) pastures in England, asked: “Why are the cattle on a common so puny and stunted? Why is the common itself so bare-worn, and cropped so differently from the adjoining inclosures?”

Lloyd’s answer assumed that each human exploiter of the common was guided by self-interest. At the point when the carrying capacity of the commons was fully reached, a herdsman might ask himself, “Should I add another animal to my herd?” Because the herdsman owned his animals, the gain of so doing would come solely to him. But the loss incurred by overloading the pasture would be “commonized” among all the herdsmen. Because the privatized gain would exceed his share of the commonized loss, a self-seeking herdsman would add another animal to his herd. And another. And reasoning in the same way, so would all the other herdsmen. Ultimately, the common property would be ruined.

Even when herdsmen understand the long-run consequences of their actions, they generally are powerless to prevent such damage without some coercive means of controlling the actions of each individual. Idealists may appeal to individuals caught in such a system, asking them to let the long-term effects govern their actions. But each individual must first survive in the short run. If all decision makers were unselfish and idealistic calculators, a distribution governed by the rule “to each according to his needs” might work. But such is not our world. As James Madison said in 1788, “If men were angels, no Government would be necessary” ( Federalist, no. 51). That is, if all men were angels. But in a world in which all resources are limited, a single nonangel in the commons spoils the environment for all.

The spoilage process comes in two stages. First, the non-angel gains from his “competitive advantage” (pursuing his own interest at the expense of others) over the angels. Then, as the once noble angels realize that they are losing out, some of them renounce their angelic behavior. They try to get their share out of the commons before competitors do. In other words, every workable distribution system must meet the challenge of human self-interest. An unmanaged commons in a world of limited material wealth and unlimited desires inevitably ends in ruin. Inevitability justifies the epithet “tragedy,” which I introduced in 1968.

Whenever a distribution system malfunctions, we should be on the lookout for some sort of commons. Fish populations in the oceans have been decimated because people have interpreted the “freedom of the seas” to include an unlimited right to fish them. The fish were, in effect, a commons. In the 1970s, nations began to assert their sole right to fish out to two hundred miles from shore (instead of the traditional three miles). But these exclusive rights did not eliminate the problem of the commons. They merely restricted the commons to individual nations. Each nation still has the problem of allocating fishing rights among its own people on a noncommonized basis. If each government allowed ownership of fish within a given area, so that an owner could sue those who encroach on his fish, owners would have an incentive to refrain from overfishing. But governments do not do that. Instead, they often estimate the maximum sustainable yield and then restrict fishing either to a fixed number of days or to a fixed aggregate catch. Both systems result in a vast overinvestment in fishing boats and equipment as individual fishermen compete to catch fish quickly.

Some of the common pastures of old England were protected from ruin by the tradition of stinting—limiting each herdsman to a fixed number of animals (not necessarily the same for all). Such cases are spoken of as “managed commons,” which is the logical equivalent of socialism . Viewed this way, socialism may be good or bad, depending on the quality of the management. As with all things human, there is no guarantee of permanent excellence. The old Roman warning must be kept constantly in mind: Quis custodiet ipsos custodes? (Who shall watch the watchers themselves?)

Under special circumstances even an unmanaged commons may work well. The principal requirement is that there be no scarcity of goods. Early frontiersmen in the American colonies killed as much game as they wanted without endangering the supply, the multiplication of which kept pace with their needs. But as the human population grew larger, hunting and trapping had to be managed. Thus, the ratio of supply to demand is critical.

The scale of the commons (the number of people using it) also is important, as an examination of Hutterite communities reveals. These devoutly religious people in the northwestern United States live by Marx’s formula: “From each according to his ability, to each according to his needs.” (They give no credit to Marx, however; similar language can be found several places in the Bible.) At first glance Hutterite colonies appear to be truly unmanaged commons. But appearances are deceiving. The number of people included in the decision unit is crucial. As the size of a colony approaches 150, individual Hutterites begin to undercontribute from their abilities and overdemand for their needs. The experience of Hutterite communities indicates that below 150 people, the distribution system can be managed by shame; above that approximate number, shame loses its effectiveness.

If any group could make a commonistic system work, an earnest religious community like the Hutterites should be able to. But numbers are the nemesis. In Madison’s terms, nonangelic members then corrupt the angelic. Whenever size alters the properties of a system, engineers speak of a “scale effect.” A scale effect, based on human psychology, limits the workability of commonistic systems.

Even when the shortcomings of the commons are understood, areas remain in which reform is difficult. No one owns the Earth’s atmosphere. Therefore, it is treated as a common dump into which everyone may discharge wastes. Among the unwanted consequences of this behavior are acid rain, the greenhouse effect, and the erosion of the Earth’s protective ozone layer. Industries and even nations are apt to regard the cleansing of industrial discharges as prohibitively expensive. The oceans are also treated as a common dump. Yet continuing to defend the freedom to pollute will ultimately lead to ruin for all. Nations are just beginning to evolve controls to limit this damage.

The tragedy of the commons also arose in the savings and loan (S&L) crisis. The federal government created this tragedy by forming the Federal Savings and Loan Insurance Corporation (FSLIC). The FSLIC relieved S&L depositors of worry about their money by guaranteeing that it would use taxpayers’ money to repay them if an S&L went broke. In effect, the government made the taxpayers’ money into a commons that S&Ls and their depositors could exploit. S&Ls had the incentive to make overly risky investments, and depositors did not have to care because they did not bear the cost. This, combined with faltering federal surveillance of the S&Ls, led to widespread failures. The losses were “commonized” among the nation’s taxpayers, with serious consequences to the federal budget (see savings and loan crisis ).

Congestion on public roads that do not charge tolls is another example of a government-created tragedy of the commons. If roads were privately owned, owners would charge tolls and people would take the toll into account in deciding whether to use them. Owners of private roads would probably also engage in what is called peak-load pricing, charging higher prices during times of peak demand and lower prices at other times. But because governments own roads that they finance with tax dollars, they normally do not charge tolls. The government makes roads into a commons. The result is congestion.

About the Author

The late Garrett Hardin was professor emeritus of human ecology at the University of California at Santa Barbara. He died in 2003.

Further Reading

Related content, terry anderson on the environment and property rights.

Skip to Content

The tragedy of the ‘Tragedy of the Commons’

- Share via Twitter

- Share via Facebook

- Share via LinkedIn

- Share via E-mail

On the 50 th anniversary of Garrett Hardin’s influential essay about the 'freedom to breed,' the director of the CU Population Center contends he missed the mark

“Freedom to breed will bring ruin to all.”

The ominous statement reads more like a line from a dystopian novel than a peer-reviewed journal article. But it is, in fact, the punch-line of one of the most influential scientific essays to date.

Published in Science in December 1968 by the late University of California ecologist Garrett Hardin, the 6,000-word Tragedy of the Commons has been cited more than 38,000 times and informed policies on everything from climate change to intellectual property to digital content.

Lori Mae Hunter

Its bold assertion that, left unchecked, population growth will inevitably outpace the earth’s resources helped ignite a zero-population fervor in the 1970s, was often used to justify China’s now-defunct one-child policy, and is still conjured today in op-eds about immigration, Front Range overpopulation and fertility planning in the developing world.

But on the 50 th anniversary of its publication, a new CU Boulder-led paper published this month in the journal Nature Sustainability argues that Hardin’s theories about overpopulation were “simplistic” and “underdeveloped” and run the risk of leading to ill-informed policy.

“Pointing fingers at people who live in Tanzania and have large families or people who migrate here from elsewhere is not going to solve our environmental problems,” contends lead author Lori Mae Hunter, director of the CU Population Center at the Institute of Behavioral Science .

“It distracts us from looking at the way we live our own lives, our own consumption patterns and the way we build our own transportation and energy systems.”

Selfish herdsmen, a growing flock, and climate change

Hardin’s parable centers around a flock of hypothetical herdsman who, if given access to a communal pasture, will increase their herd size until they collectively degrade the pasture. “Ultimately, the commons collapses, hence the tragedy,” summarizes Hunter, who also chairs the sociology department.

The metaphor is most often conjured in the context of environmental protection: The global atmosphere is the “commons.” Owned by no one, used by everyone, and left unregulated it, like the pasture, is doomed to be overexploited and ruined.

Hardin’s parable centers around a flock of hypothetical herdsman who, if given access to a communal pasture, will increase their herd size until they collectively degrade the pasture. “Ultimately, the commons collapses, hence the tragedy,” summarizes Hunter.

That prediction has been debated for years, with one challenger, the late Elinor Ostrom, winning a Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences for her elucidation of a more optimistic real-life scenario—one in which small communities around the globe have managed to devise ways to successfully manage common resources like grazing land, forests and irrigation waters.

But Hardin’s second argument—the overpopulation argument—has not received the same critical attention.

That’s the task that Hunter and co-author Aseem Prakash, a political scientist at University of Washington, set out to do.

“It’s time to move past Hardinesque population alarmism … in order to develop better-informed policy,” they write.

Relinquishing the freedom to breed

In his essay, Hardin bluntly applies the “tragedy of the commons” idea to parenting, suggesting that the availability of food and other resources as part of the “welfare state” drives people to procreate and overpopulate:

“If each human family were dependent only on its own resources; if the children of improvident parents starved to death; if, thus, overbreeding brought its own punishment to the germ line—then there would be no public interest in controlling the breeding of families. But our society is deeply committed to the welfare state,” he wrote. His solution: Mandated population control:

“The only way we can preserve and nurture other and more precious freedoms is by relinquishing the freedom to breed.”

That argument had ripple effects, notes Prakash, indirectly fueling heated arguments within the Sierra Club over whether population control, including stronger checks against U.S. immigration, should be a central pillar of their environmental agenda. (It is not).

We would not argue that population doesn’t matter at all when it comes to the environment. Of course it matters. But simply pointing a finger at others and saying you shouldn’t be here obscures all the other things we should be thinking about.”

“Even today, with all the discussions of the border wall, in the back of the mind is Hardin’s overpopulation thesis again. That if you have too many resources, people will in-migrate and procreate,” said Prakash. “What we are pointing out is that is much more complex than that.”

They note that while the birth rate in the United States is at its lowest in 30 years, 51 percent of people here still believe the population is growing too fast.

Meanwhile, they add, in the places where the population is truly growing rapidly, carbon emissions per capita are minuscule compared to those in the West. For instance, U.S. residents emit 16.49 tons per capita in carbon emissions, while in Tanzania, per capita emissions run around 0.22 tons.

The complex reasons women get pregnant, or don’t

While Hardin drew a simple conclusion—that availability of resources drives procreation—Prakash and Hunter also point to a complex web of factors, including social values, cultural norms and local reproductive health policies, that contribute to family planning.

For instance, in Nepal, where resources are scarce, women tend to want to have more children to help them to gather those resources—such as firewood and food for their animals.

In Rwanda, which had notoriously high fertility levels prior to 2005, fertility rates have declined a stunning 25 percent—from 6.1 to 4.6 children per woman—not due to a shrinking of the “welfare state” but due to a national prioritization of family planning and a greater exposure to mass media, which shifted male attitudes about birth control. Together, that led to a huge boost in contraceptive use.

“People don’t just procreate because they know they can feed their family,” says Prakash. “We shouldn’t take these simplistic notions—a la Hardin—and use them to support misinformed policies.”

Instead, he and Hunter suggest, policymakers and others concerned about overpopulation should consider the key role sociocultural factors can play in fertility decisions and take steps to empower women to control their own family planning.

And when it comes to the environment, they argue, they should stop pointing fingers at large families, and take a close look at their own house.

“We would not argue that population doesn’t matter at all when it comes to the environment. Of course it matters,” said Hunter. “But simply pointing a finger at others and saying you shouldn’t be here obscures all the other things we should be thinking about.”

Related Articles

CU Boulder research to focus on often-overlooked rural America

To confront wildfire risk, experts get social

Evidence of climate-driven conflicts is piling up

- Institute of Behavioral Science

- Spring 2019

The Tragedy of the Commons

29 pages • 58 minutes read

A modern alternative to SparkNotes and CliffsNotes, SuperSummary offers high-quality Study Guides with detailed chapter summaries and analysis of major themes, characters, and more.

Essay Analysis

Key Figures

Index of Terms

Literary Devices

Important Quotes

Essay Topics

Discussion Questions

Describe how a small annual increase in a human population can lead to exponential growth in that population.

What process limits the populations of plants and animals in the natural world? How do humans get around that limitation?

Explain how individuals using an unregulated common resource can gradually overuse that resource until it collapses.

Don't Miss Out!

Access Study Guide Now

Featured Collections

Business & Economics

View Collection

Science & Nature

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Santa Barbara. "The Tragedy of the Commons" was originally given as an address to the Pacific Division of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, is copyrighted by the AAAS, and is reprinted with their permission from Science, 13 December 1968, vol. 162, pp. 1243-48. The Tragedy of the Commons by Garrett Hardin A t the end ...

The Tragedy of the Tragedy of the Commons. The man who wrote one of environmentalism's most-cited essays was a racist, eugenicist, nativist and Islamaphobe—plus his argument was wrong

The Tragedy of the Commons Author(s): Garrett Hardin Source: Science, New Series, Vol. 162, No. 3859 (Dec. 13, 1968), pp. 1243-1248 Published by: American Association for the Advancement of Science