Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Youth unemployment: a review of the literature

1985, Journal of Adolescence

Related Papers

Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis

Henry Levin

Journal of Adolescence

Lindsey Mean

aris accornero

ABSTRACT: This paper underlines, first of all, that diverse ways to define and compute the unemployed people used by various countries produces different figures, and images too, of this phenomenon. Using overly restricted criteria means depriving oneself of useful information. Secondly, the author explains the profound differences between traditional unemployment and contemporary joblessness, which concerns many young people in Western countries. Finally, the author discusses this new feature of the unemployment phenomenon, and affirms that joblessness is not a ‘non-use‘ but rather a ‘new-use‘ of young people by modern capitalistic societies.

Scottish Journal of Political Economy

Karsten Albæk

Michael Oddy

ABSTRACT Young people are particularly vulnerable to unemployment and the consequences of this for psychosocial development and mental health are not well understood.This study is an investigation of some of these consequences.The psychological well-being and mental health of employed and unemployed school-leavers of both sexes was investigated.Those school-leavers who were unemployed were found to be more depressed and more anxious than those in work and showed a higher incidence of minor psychiatric morbidity. Unemployed young people had lower self-esteem than their employed peers and poorer subjective wellbeing. They were also found to be less well socially adjusted. Young women showed poorer psychological well-being than young men, irrespective of employment status.The psychological impact of unemployment for young people is discussed in relation to individual and sex differences and the question of whether poor mental health is a cause or a consequence of unemployment is considered.

Procedia Economics and Finance

Barbora Gontkovičová

Alexander Nabiulin

RePEc: Research Papers in Economics

Barbara Petrongolo

RELATED PAPERS

Field Environmental Philosophy

KALAIVAANAN MURTHY

BENTHAM SCIENCE PUBLISHERS eBooks

Hyperfine Interactions

Journal of Pharmacognosy and Phytochemistry

Anubhuti sharma

Journal of computational neuroscience

Khánh Linh Nguyễn

International journal of systematic bacteriology

Karel Kersters

Shipbuilding & marine infrastructure

International Journal of Applied Mathematics and Theoretical Physics

Ravo Tokiniaina Ranaivoson

Raullyan Borja Lima e Silva

a/b Autobiography Studies

Anders Høg Hansen

Francisco Javier Tinajero

International Journal of Geometric Methods in Modern Physics

Partha Guha

CENTRAL EUROPEAN SYMPOSIUM ON THERMOPHYSICS 2019 (CEST)

Vladimir Kruchinin

DOAJ (DOAJ: Directory of Open Access Journals)

Rehmat Zaman

Mastozoología neotropical

Rubén Barquez

Said Goueli

Journal of Applied Science and Technology (JAST)

Collins Nana ANDOH

Anna Fogelberg Eriksson

Immunogenetics

Eduardo Vedovetto Santos

Academic Radiology

Gregory Diette

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 12 October 2020

A systematic review of employment outcomes from youth skills training programmes in agriculture in low- and middle-income countries

- W. H. Eugenie Maïga ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2735-8945 1 ,

- Mohamed Porgo ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-7325-3610 2 ,

- Pam Zahonogo 2 ,

- Cocou Jaurès Amegnaglo 3 ,

- Doubahan Adeline Coulibaly 2 ,

- Justin Flynn 4 ,

- Windinkonté Seogo 5 ,

- Salimata Traoré ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8373-4995 2 ,

- Julia A. Kelly ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-0796-0461 6 &

- Gracian Chimwaza 7

Nature Food volume 1 , pages 605–619 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

10k Accesses

11 Citations

16 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Agriculture

A Publisher Correction to this article was published on 20 October 2020

This article has been updated

Engagement of youth in agriculture in low- and middle-income countries may offer opportunities to curb underemployment, urban migration, disillusionment of youth and social unrest, as well as to lift individuals and communities from poverty and hunger. Lack of education or skills training has been cited as a challenge to engage youth in the sector. Here we systematically interrogate the literature for the evaluation of skills training programmes for youth in low- and middle-income countries. Sixteen studies—nine quantitative, four qualitative and three mixed methods—from the research and grey literature documented the effects of programmes on outcomes relating to youth engagement, including job creation, income, productivity and entrepreneurship in agriculture. Although we find that skills training programmes report positive effects on our chosen outcomes, like previous systematic reviews we find the topic to chronically lack evaluation. Given the interest that donors and policymakers have in youth engagement in agriculture, our systematic review uncovers a gap in the knowledge of their effectiveness.

Similar content being viewed by others

Investigating the effect of vocational education and training on rural women’s empowerment

Strained agricultural farming under the stress of youths’ career selection tendencies: a case study from Hokkaido (Japan)

Conceiving of and politically responding to NEETs in Europe: a scoping review

Youth in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC) disproportionately experience working poverty. In 2019, about 21% of employed youth in LMIC were living on less than US$2 a day, compared with 16% of the overall working population 1 . In sub-Saharan Africa, nearly 70% of working youth were found to be living in poverty; in South Asia, close to 50% were living in poverty 2 . Issues of youth unemployment and underemployment are linked to greater likelihood of future unemployment, decreased future job satisfaction, lower income and poorer health in adulthood 3 . National consequences include greater costs to support public programmes (such as public work programmes that provide temporary jobs) and indirect costs of lower earnings such as loss of investment in education 4 , 5 . Furthermore, youth underemployment is linked to disillusionment and the possibility of social unrest 6 .

The working-age population in LMIC is predicted to double in the next 35 years 7 and while this presents challenges, many LMIC are currently experiencing a demographic dividend phase where there is a high ratio of working-age population to dependents. This offers unique prospects for economic development with concomitant reductions in poverty and food insecurity. Addressing unemployment and underemployment is, therefore, a major policy priority for LMIC 6 , and a key sector for the creation of employment opportunities, especially in Africa and Asia, is agriculture 6 , 8 , 9 .

Many people in LMIC rely on agriculture for their livelihoods (32% in 2019) 10 , either directly, as farmers, or indirectly in sectors that derive their existence from agricultural production 8 , 9 , 11 . Agricultural development is estimated to be up to 3.2 times more effective in alleviating poverty in low-income, resource-rich countries than any other sector 12 . Due to the close links between poverty and food insecurity 13 , 14 , 15 , agricultural development could also have positive consequences for the alleviation of hunger, particularly for women, as their empowerment in agriculture improves households’ food security and nutrition 16 , 17 , 18 .

However, there has been a declining trend of youth participation in agriculture since 2000, mainly in favour of the service sector 6 , 19 , 20 , which precipitates migration from rural to urban areas. Increased educational attainment for rural youth coupled with inability to rent or own land is a driver of urban migration 21 . In addition, the increasing ageing farmer population in rural areas exacerbates the demographic pressure on land at the expense of the youth 22 .

A further constraint on youth engagement in agriculture is a lack of education in disciplines related to agriculture or skills training 23 , 24 , 25 . A study among Thailand’s youth reported that 71% identified knowledge of farming practices as a pre-requisite to setting up a viable farm 23 . In rural Ethiopia, government initiatives to increase skills and productivity, and introduce improved and modern farming methods have generated interest among youth in joining the sector, and in Indonesia, vocational training was noted as increasing the likelihood of a successful career in agriculture 26 . A study in Zambia on rural youth aspirations, opinions and perceptions on agriculture documented high interest among youth in more productive forms of farming, such as the use of draught animals, electricity and the increased application of fertilizers 24 . Such findings challenge an assumption common in policy proposals that youth are not interested in agriculture 25 . Today, with the development of information and communication technology (ICT), young people have more opportunities to strengthen their skills and access relevant information and are therefore well positioned to understand market dynamics, and institutional and financial systems, enabling them to initiate and capitalize on processes of change in the agricultural sector 27 , 28 . Human capital theory predicts a positive correlation between human capital accumulation and labour productivity. On that basis, skills training can be used to improve agricultural employment outcomes 29 . Where governments and policy interventions support skills training for youth, there is a real possibility for entrepreneurship, a competitive economy and ultimately national growth. But, despite the implementation of skills training interventions, generally via youth employment programmes 30 , few specifically target agricultural skills training in LMIC and very little is known about the effectiveness of youth agricultural interventions 30 , 31 .

Here we systematically review skills-based training interventions that aim to increase youth engagement in agricultural employment in LMIC to better inform investment decisions made by donors and policymakers. The interventions include agriculture-related courses, on-the-job training, technical or vocational education and training in agriculture, as well as general skills training including entrepreneurship, financial literacy and life skills for engagement in agriculture. The outcomes of interest we started out with were: employment along an agricultural value chain; employment in agribusiness; engagement in contract farming; development of agricultural entrepreneurship; agricultural business performance (productivity, profit, income, marketing rate); involvement in agricultural extension service provision. After data extraction, the outcomes of interest found in the selected studies are jobs created in the agricultural sector, self-employment and entrepreneurship, provision of and employment in extension services, profit/income/earnings from an agricultural activity or job, farm productivity, and the accessibility of employment opportunities in the sector. These outcomes pertain to the categories of jobs that can be found along the agricultural value chain.

We found among the studies yielded from the systematic literature search that skills training interventions reported employment in agriculture, agribusiness or agriculture-related activities, development of agricultural entrepreneurship, agricultural business performances (productivity, profit, income) and involvement in agricultural extension service provision for young participants . However, we also found a chronic lack of evaluation of the effectiveness of interventions designed to enhance agricultural opportunities and engagement for young people in LMIC, a finding previously shown 31 .

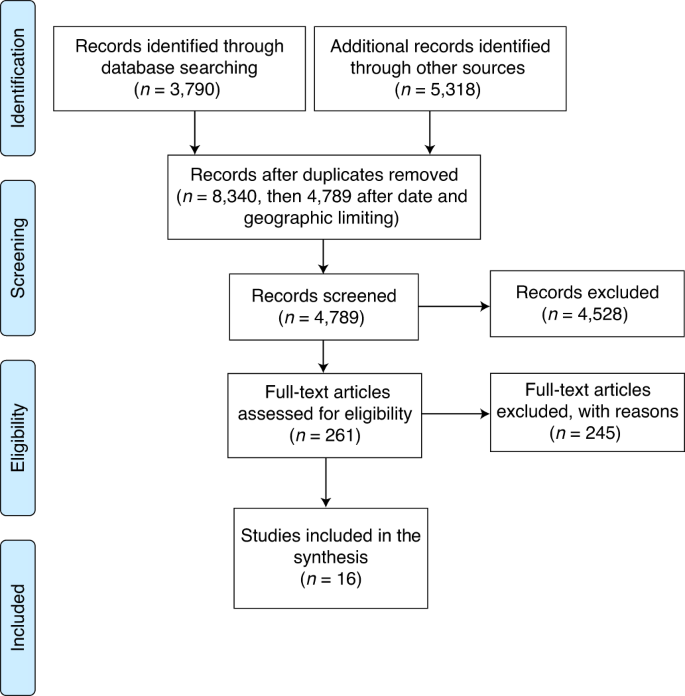

Sixteen studies were identified for review based on a priori inclusion and exclusion criteria (Fig. 1 ) detailed in our Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Protocol, PRISMA-P (Supplementary Material 1 , summarized in Methods and published on Open Science Framework, https://osf.io/bhegq// ).

Inclusion criteria were youth as the target population; inclusion of one or more outcome of interest (employment along an agricultural value chain; employment in agribusiness; engagement in contract farming; development of agricultural entrepreneurship; agricultural business performance (productivity, profit, income, marketing rate); involvement in agricultural extension service provision); agriculture sector as field of study; skills training as an intervention; publication in English or French between 1990 and 2019; original research or review of existing research or institutional reports; targets low- and middle-income country or countries as area(s) of study (see list of World Bank country classifications (Supplementary Table 1 ); a clear and well-accepted methodology (studies were excluded if there was no clear method on sampling, data analysis or discussion of results). Studies meeting the inclusion criteria and targeting mixed group (youth and other demographic groups) were also retained in the search strategy. A double-blind title and abstract screening were performed on 4,789 articles that were uploaded to systematic review software, Covidence, for title and abstract screening. Each article was reviewed by two independent reviewers and discrepancies were resolved by a third independent author within the team. After title and abstract screening, 261 articles remained. From title and abstract screening, 16 articles met a priori inclusion criteria.

Characteristics of selected studies

A data extraction template (Supplementary Table 2 ) was used to document all information of interest from each of the 16 studies, overviewed in Table 1 .

Eleven of the studies were based in Africa 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 and five in Asia 43 , 44 , 45 , 46 , 47 . Twelve of the studies were published in peer-reviewed journals 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 , 44 , 45 , 46 , 47 and the rest originated from the grey literature, including one dissertation 38 , one report 37 and two working papers 32 , 43 .

With regard to the study design, nine of the included studies were quantitative 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 43 , 44 , 45 , four were qualitative 41 , 42 , 46 , 47 and three used mixed non-experimental 38 , 39 , 40 methods. Only one study used randomized control trial (RCT) as a study design method of evaluation 32 . Quasi-experimental impact methods (difference-in-differences (DID) and propensity score matching (PSM)) and quantitative non-experimental methods (statistical and econometric methods) were used in two 33 , 43 and six 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 44 , 45 studies, respectively. Nine of the included studies relied on survey data 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 43 , 44 , 45 , one study used data from interviews 47 , one study used data from focus groups 42 and the rest of the studies used mixed sources of data 38 , 39 , 40 (Supplementary Table 3 ).

Table 2 collates information from the selected studies on the basis of types of intervention and participant characteristics. Technical education/training 35 , 41 , 42 , 46 and vocational training 37 , 40 , 44 , 45 constituted half of the interventions (four, each); youth programmes, agriculture-related courses and on-the-job training were identified as interventions in three 33 , 34 , 38 , two 39 , 47 and one 36 of the studies, respectively, and the remainder of the studies combined two types of intervention 32 , 43 . Twelve of the interventions were implemented through public policies 33 , 34 , 35 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 , 45 , 47 ; non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and a mix of institutions (public and private) were each identified as implementers in two 32 , 36 and one 46 of the studies, respectively, and one study reported intervention implemented by an international institution 40 .

Nine of the studies solely targeted youth 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 37 , 38 , 43 , 45 , 46 , and seven targeted mixed groups of youth and others 36 , 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 , 44 , 47 . In fourteen studies, the participants were from all genders. In nine of the studies, participants were a mixed group of those already and not yet engaged in agriculture 32 , 34 , 37 , 39 , 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 , 46 ; in five of the studies, participants were already engaged in agriculture before receiving skills training interventions 35 , 36 , 37 , 45 , 47 ; there was not enough information to determine whether the participants were already engaged in agriculture in two studies 33 , 40 . Six of the studies indicated that the participants resided in rural areas 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 46 , 47 , while participants located in urban areas and in both rural and urban areas were identified in four 32 , 38 , 40 , 45 and five 37 , 39 , 41 , 43 , 44 of the studies, respectively; there was not enough information to determine the location of the participants in one 42 study. The population targeted in the studies was both educated and non-educated youth. Among the nine studies 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 37 , 38 , 43 , 45 , 46 that focused exclusively on youth, two targeted youth with a secondary education background 34 , 46 , one 45 targeted youth with a university background and six 32 , 33 , 35 , 37 , 38 , 43 of the studies targeted youth with a mixed educational background.

Risk of bias assessment

We evaluated the risk of bias of the included studies based on a previous approach 48 . The domains of risk retained are (1) the sampling technique used for the study, (2) the type of intervention, (3) the choice of the area of study, (4) the population targeted, (5) the method of data collection, (6) the method of data analysis, (7) the measurement of outcome and (8) the statistical significance of the effect. For each domain of risk, the criteria evaluated were defined and rated by their relevance for assessing the effectiveness of the interventions. Supplementary Table 4 summarizes the criteria of each domain of risk and its assessment and rating.

Using this scale, 15% of our included studies are at low risk of bias, 60% at moderate risk of bias and the remaining 25% at serious risk of bias. The outcome of the risk of bias assessment of the included studies in this systematic review is presented in Table 3 .

The risk of bias assessment process highlighted differences in focus, methods used and standards of evidence across the included studies. Weaknesses in study design, survey methods and method of evaluation of the impact of the interventions were common in most of the studies (with the exception of the studies ranked at low risk of bias), leading to weak results and limited generalizability.

Effects on youth employment outcomes

The youth employment outcomes of interest to this systematic review are job creation, self-employment, engagement in entrepreneurship, provision of extension services, productivity of the farm/agriculture-related activities, profits/income, and job search or employment opportunity in agriculture-related activities. Here we elaborate on the study design and risk of bias of all studies, and highlight the effects on outcomes of interest for a selection of low and moderate risk studies.

Job creation in agriculture

Eight studies 32 , 38 , 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 , 45 looked at job creation in agriculture as an outcome. Among those studies, three are quantitative studies 32 , 43 , 45 , two are qualitative studies 41 , 42 and three are mixed-methods studies 38 , 39 , 40 .

In one quantitative study, deemed at low risk of bias (Table 3 ), 1,700 workers and 1,500 firms were followed over four years to compare the effects of offering workers vocational training and offering firms wage subsidies to train workers on-the-job (firm training) in Uganda 32 . The results showed that both interventions allowed participants to acquire sector-specific skills and firm-specific skills leading to higher employment rates post-training for each type of worker, but the effect was greater for vocational training compared with firm training (21% versus 14% post-training employment rate) and their total earnings rose by more compared with the firm-training intervention (34% versus 20%). The qualitative studies 41 , 42 , although not designed to assess the effectiveness of an intervention, highlighted a link between skills training and employment outcome. However, both studies were deemed at serious risk of bias. A mixed-methods study 38 on youth programmes in Ghana showed that about 86.4% of young people still pursued maize farming a year after exiting the Youth in Agriculture Programme (YIAP). This public intervention was implemented to address youth unemployment in Ghana with the goal of getting young people to engage in the agricultural sector. The four main components of the programme were crops/block farm, livestock and poultry, fisheries/aquaculture, and agribusiness. The study focuses on evaluating the crops/block farm component. The crops cultivated under the YIAP include maize (seed and grain), sorghum, soybean, tomato and onion. This study is ranked at moderate risk of bias.

Self-employment in agriculture

Six studies 36 , 39 , 41 , 45 , 46 , 47 indicated that skills training interventions resulted in self-employment in agriculture. Out of these studies, two studies are quantitative 36 , 45 , three are qualitative 41 , 46 , 47 and one is a mixed-methods study 39 .

In one quantitative study 36 , self-employment was stimulated by a skills training radio campaign on growing orange-fleshed sweet potatoes in Ghana, Tanzania, Burkina Faso and Uganda. A survey of the local communities where the radio campaign was run found that households that reported hearing the educational radio campaign in Ghana, Tanzania, Burkina Faso and Uganda were 8.9, 2.3, 1.7 and 1.1 times more likely, respectively, to engage in growing orange-fleshed sweet potatoes, than households that did not. This study is deemed at moderate risk of bias.

Engagement/entrepreneurship in agriculture

Five studies 34 , 38 , 39 , 41 , 42 showed that skills training interventions encourage youth engagement or entrepreneurship in agriculture. Among these studies, one is quantitative 34 , two are qualitative 41 , 42 and two are mixed-methods studies 38 , 39 . In the quantitative study, a youth programme including agriculture content (training in livestock production, crop production and dairy farming) in South Africa indicated that youth engagement or self-employment in agriculture is eight times higher when agricultural programmes that specifically target the youth are implemented compared with when agricultural programmes are not available. This study is deemed at moderate risk of bias. Regarding the mixed-methods studies, one study 38 , deemed at moderate risk of bias with youth programme (YIAP in Ghana) as intervention, showed that after exiting the programme, 86.4% of beneficiaries were still involved in farming within a year. The qualitative studies were deemed at serious risk of bias.

Productivity of the farm/agriculture

Two studies 35 , 41 found that skills training interventions lead to higher productivity of the farms. One of the studies is quantitative 35 and the other is qualitative 41 . In the quantitative study, estimated to be at moderate risk of bias, the National Agricultural Extension and Research Liaison Services (NAERLS) rural youth extension programmes (RUYEP) helped 84.2% of beneficiaries achieve yields that exceed one tonne per hectare for maize in Nigeria, compared with 66% of non-participants 35 . The qualitative study 41 , outlined in Table 1 , is deemed at serious risk of bias.

Profit/income earning of the farm

Ten studies 32 , 33 , 35 , 38 , 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 , 47 looked at profit/income earning of the farm as an outcome. Among those studies, five are quantitative 32 , 33 , 35 , 43 , 44 , three are qualitative 41 , 42 , 47 and two 38 , 40 are mixed-methoda studies. In one of the quantitative studies, the Training for Rural Economic Empowerment (TREE) programme increased beneficiaries’ income by US$787 compared with non-beneficiaries over the 2011–2014 programme implementation period 33 . This study is deemed at low risk of bias. Another quantitative study 44 , deemed at moderate risk of bias, found that the continued adopters of beekeeping and mushroom growing had increased their family income by 49% and 24%, respectively. The three qualitative studies, not described here but outlined in Table 1 , are deemed at serious risk of bias 41 , 42 , 47 . The mixed-methods study 40 showed that the creation of a company that recycled livestock by-product (bone crafts and soap production) allowed vulnerable women and youths to earn an additional US$44.6 from bone crafts and US$50.2 from soap production weekly. This study is at moderate risk of bias.

Job search or employment opportunity

Three studies 39 , 41 , 42 investigated the effect of skills training on this outcome. One study is a mixed-methods design 39 and two 41 , 42 are qualitative. All of these studies, not described here but outlined in Table 1 , are deemed at serious risk of bias.

Provision of agricultural extension service

One study 39 investigated on the effects of skills interventions on provision of agricultural extension service and found that the majority of graduates who benefited from student–farmer attachment and/or the Supervised Student Enterprise Project (SSEP) were engaged in extension work. This study, outlined in Table 1 , is deemed at serious risk of bias.

Intervention type and engagement in agriculture

Agriculture-related courses.

Two studies 39 , 47 used agriculture-related courses as interventions . One of these studies is a mixed-methods study 39 and the other is qualitative 47 . The mixed-methods study investigated several outcomes in agriculture, namely, job creation, entrepreneurship, self-employment, provision of agricultural extension service and job search opportunity, which were found to improve with the skills training interventions. The interventions consisted of introducing innovations in agricultural training curricula (community engagement and agri-enterprise development) at Gulu University in Uganda. The community engagement took the form of a one year (or less) placement of undergraduate students to work with smallholder farmers and farmer groups within a 10 km radius of the university. The agri-enterprise development consisted of having the students design business plans; the best plans were rewarded with start-up capital. The employment rate among the graduates was 84% six months after graduation and increased to 90% after one year; less than 2% of the graduates created their own businesses. The qualitative study 47 investigated two outcomes in agriculture, self-employment and income, which were found to increase after skills training on ready food mixes, maize products and mango products. The two studies are deemed to be at serious risk of bias.

Technical education/training

Four studies 35 , 41 , 42 , 46 used technical education/training as interventions. Only one of these studies is quantitative 35 ; the others are qualitative 41 , 42 , 46 . The quantitative study 35 investigated productivity and income of the farm, and found both to increase after the intervention. The NAERLS RUYEP objectives are to provide technical advisory services to boost agricultural production and raise living standards of the youth. The results showed that the intervention allowed 84.2% of beneficiaries to achieve yields that exceed one tonne per hectare for maize in Nigeria, compared with 66% of non-participants. This study is deemed at moderate risk of bias. Among the qualitative studies, one 46 looked at self-employment as an outcome and found a positive association with the intervention. The other two qualitative studies are deemed of serious risk of bias.

Youth programme

Youth programmes are programmes that target youth and train them in either specific skills (agricultural skills, ICT skills and so on) or broad skills (decision-making skills, business skills and so on) to enhance their employability. These have been used as interventions in three studies 33 , 34 , 38 . One of these studies is mixed methods 38 and the two others are quantitative 33 , 34 . The mixed-methods study 38 investigated the following outcomes in agriculture: job creation, engagement and income; a positive association was found between youth programme and both engagement and income. The results showed that about 86.4% of young people still pursued maize farming one year after exiting the programme and the mean income of GH¢758 obtained by beneficiaries was found to be greater than the national mean annual per capita income of GH¢734. Among the two quantitative studies 33 , 34 , one investigated the income of beneficiaries 33 and the other 34 looked at engagement in agriculture; both found a positive effect of the intervention on their outcome. The study that investigated the income of beneficiaries as an outcome revealed that the TREE programme increased beneficiaries’ income by US$787 compared with non-beneficiaries over the 2011–2014 programme implementation period 33 . In the other study 34 , a youth programme including agriculture content (training in livestock production, crop production and dairy farming) in South Africa indicated that youth engagement or self-employment in agriculture is eight times higher when agricultural programmes that specifically target the youth are implemented compared with when agricultural programmes are not available. Given that all three studies are at moderate or low risk of bias, we can conclude that the findings suggest that youth programmes have the potential to influence youth engagement in agriculture.

On-the-job training

Only one study 36 looked at on-the-job training as an intervention. The outcome investigated is self-employment, on which the intervention had a positive effect. The results showed that households that reported listening to an educational radio campaign in Ghana, Tanzania, Burkina Faso and Uganda were 8.9, 2.3, 1.7 and 1.1 times more likely, respectively, to engage in growing orange-fleshed sweet potatoes, than households that did not. The study was deemed at moderate risk of bias.

Vocational training

Vocational training has been used as an intervention by four studies 37 , 40 , 44 , 45 . Among these studies, three are quantitative 37 , 44 , 45 and one is a mixed-methods study 40 . One quantitative study 44 investigated income as an outcome, on which positive effects of the intervention were found in India. The findings indicated that vocational training programmes have resulted in continued adoption of beekeeping and mushroom cultivation enterprises by 20% and 51% of trained farmers, respectively, and increased their family income by 49% and 24%, respectively. The second quantitative study investigated job creation and self-employment as outcomes and found positive links with the training 45 . The results of the study highlighted that vocational training in agriculture in Iran resulted in employment of more than half of graduates. The third quantitative study found a positive effect of the intervention on job creation, the sole outcome it had investigated 37 . The study showed that vocational training for a youth employment programme in Ghana resulted in the creation of 16,383 jobs in agribusiness. All four studies are deemed at moderate risk of bias (Table 3 ); however, the use of descriptive methods in some of these studies preclude us from concluding that they are effective in improving employment outcomes for youth in the agricultural sector.

Vocational training and technical training

One study 43 investigated the combination of vocational training and technical training as an intervention. The outcomes investigated are job creation and income, on which the intervention had a positive effect. The study indicated that vocational training and technical training in agriculture (poultry technician) resulted in an increase in employment of 34.2% among the 41 beneficiaries who were trained as poultry technicians in Nepal. This study is deemed at low risk of bias, suggesting that combining vocational training and technical training may be a way of improving job prospects and income for youth in the agricultural sector.

Vocational training and on-the-job training

One study 32 investigated the combination of vocational training and on-the-job training as an intervention. The outcomes investigated are job creation and earnings, on which the intervention had a positive effect. The results showed that both interventions allowed participants to acquire sector-specific skills and firm-specific skills, leading to higher employment rates post-training for vocational-trained workers compared with firm-trained workers (21% versus 14% post-training employment rate) and their total earnings rose by more compared with the firm-trained workers (34% versus 20%). This study is deemed at low risk of bias.

Duration of training

Ten studies out of the 16 overviewed in Table 1 presented information on the duration of training. Eight of these have programmes that last one year or less. The remaining studies indicated a training duration between two and five years. This suggests that training programmes predominantly have a relatively short-term duration, which is consistent with many interventions taking the form of technical and vocational education/training. The popularity of technical and vocational/education training as a model of intervention may be due to the relatively short-term nature of the training, or due to the nature of technical and vocational training, which is well suited for out-of-school youth, which are found in large numbers in LMIC 49 .

Issues facing youth engagement in agriculture today are relatively well documented, including educational attainment, matrimonial status, gender, household size, parental income and occupation, membership in social organization, access to ICT, land tenure system and access to state-run agricultural youth programmes 50 , 51 , 52 . This present systematic review, which focused solely on interventions to engage youth in agriculture, yielded a limited set of studies—nine quantitative, four qualitative and three mixed-methods studies—so generalizable conclusions are difficult to draw. The risk of bias assessment yielded three studies 32 , 33 , 43 deemed at low risk of bias, nine studies 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 40 , 44 , 45 , 46 deemed at moderate risk of bias and four studies deemed at serious of risk bias 39 , 41 , 42 , 47 .

The results of our systematic review generally are in line with those found by the systematic review of Kluve et al. 53 on interventions to improve the labour market outcomes of youth. That systematic review of 107 interventions, including skills training, in 31 countries, found small positive effects for promoting entrepreneurship and skills training—especially integrated skills training programmes—but not for employment services and subsidized employment.

Our systematic review also demonstrated that in general, skills interventions seeking to motivate youth’s engagement in agriculture do not undergo a thorough evaluation for effectiveness, with hard outcomes related to employment. Our selected studies included case studies and qualitative methods, which are not adequate methods of evaluating impact and effectiveness of interventions. Only one study used an RCT 32 . The two studies relying on a quasi-experimental approach used DID and PSM methods 33 , 43 . Indeed, the results of the risk of bias assessment indicated the studies relying on RCT and quasi-experimental impact evaluation methods were at low risk of bias. However, these study designs are expensive to conduct. We found that of the studies that evaluate interventions, the majority did not use state-of-the-art impact evaluation methods. This has been corroborated by other studies 30 , 31 , showing a chronic lack of evaluation of interventions that aim to provide agricultural skills to youth.

Training on ICT is an important aspect for attracting and retaining youth in the agricultural sector 46 . ICT offers a method of delivering training to a large number of farmers, which could enhance the performance of the youth already in agriculture and attract new youth to the sector 36 . Radio campaigns have been shown to be effective in spurring adoption and consumption of orange-fleshed potatoes in Ghana, Tanzania, Burkina Faso and Uganda 36 . A study conducted in the Philippines found that ICT training helps motivate secondary school students whose parents are engaged in agriculture to work within the sector, especially when combined with offline activities such as exposure and hands-on experience as well as creative and motivational actitivites 46 .

It is important to note that heterogeneity in gender and education are not accounted for in the analysis of the impacts of education on youth participation in agriculture. Our systematic review revealed that most of the included studies failed to address the effectiveness of targeting the population of interest—educated and uneducated youth. Illiteracy and gender heterogeneity were not addressed in the included studies. Indeed, no studies assessed the effects of training interventions on illiterate youth. This calls for investigations to focus on this vulnerable group of society, which represent about 25% of youth in sub-Saharan Africa and 11% in Southern Asia 54 . Failing to account for such variation in the background of the youth participants limits the ability to assess the effectiveness of skills training interventions.

The absence of robust research and lack of effective evaluation of the available data on the effectiveness of agricultural youth employment interventions has notable consequences on potential investment. Ultimately, the commitment of policymakers is necessary to ensure the sustainability and success of interventions to boost youth’s engagement in agriculture. It is encouraging that the majority of interventions (12 studies out of 16) studied originated from public policy, compared with three originating from non-public policy programmes (NGOs, international institution) and one from mixed policies (public and non-public policies). However, to provide a compelling basis on which to convince governments and donors to fund future interventions, as well as encourage young people to partake in training, cost-effectiveness analysis and estimates of returns on investment in training programmes is necessary. Indeed, a 2018 stocktaking of the evidence on the effectiveness of youth employment interventions in Africa found that for the agricultural sector in particular, “there is very little literature and virtually no evaluation evidence to inform policymakers about what types of interventions can improve the prospects of young people in the [agricultural] sector” 31 . Our study supports this conclusion. Moreover, to ensure that the skills training provides long-term opportunities for youth, it is crucial to establish a periodic follow-up to assess how trainees are performing after completion of a training programme. This aspect was missing in most of the interventions reviewed in this systematic review, yet it is important to check that the youth who engage in agriculture after receiving skills training are still involved and thrive in their agriculture-related business in the long term.

In summary, there is a need to foster youth skills training programmes and more importantly to evaluate more rigourously these programmes so that knowledge on good practices may be generated and transferred from one developing country to another. Estimates of returns to investment of agricultural skills training programmes are warranted as they could provide governments and donors with the evidence and cost-based analysis to continue and increase support for such programmes. Interventions also need to account for heterogeneity in gender and educational background of the youth to foster sustainability in agricultural value chains, inform inclusive policy design and ultimately contribute to reducing poverty and food insecurity in LMIC.

This systematic review was prepared following guidelines from Petticrew and Roberts 55 . The approach comprises five steps: identifying the research question; identifying relevant studies; study selection; extracting and charting the data; and collating, summarizing and reporting the results. The protocol for this study was registered on the Open Science Framework before study selection and can be accessed at https://osf.io/bhegq// . The guiding question for this systematic review was: What are the effects of skills training interventions on educated and non-educated youth employment outcomes in agricultural value chains, agribusiness or contract farming in LMIC? The inclusion and exclusion criteria to identify and then select the relevant studies are shown in Table 4 .

Regarding the risk of bias assessment, each study was assessed following the criteria of the eight domains of risk of bias we considered. The maximum score a study can obtain in terms of minimizing all domains of risk of bias is 23 stars, which is 100% of the stars. A study is deemed to be at low risk of bias across all domains if its total score is in the interval 75–100%. If the total score is in the interval 50–75%, the study is said to be at moderate risk of bias across all domains. A study is at serious risk of bias if its score falls within the interval 25–50%. When the total score ranges from 0 to 25%, the study is deemed to be at critical risk of bias across all domains. See Supplementary Table 4 for details on the criteria used.

Search strategy

An exhaustive search strategy was developed and tested in CAB Abstracts to identify all available research pertaining to the effects of skills training interventions on educated and non-educated youth employment outcomes in agriculture in LMIC. Search terms were developed to address variations of the key concepts in the research question: skills training, youth, employment or engagement, and agriculture. Searches were performed on 9 May 2019 in the following electronic databases: CAB Abstracts (access via OVID); Web of Science Core Collection (access via Web of Science); EconLit (access via ProQuest); Agricola (access via OVID); and Scopus (access via Elsevier). Full search strategies for each database, including grey literature, can be accessed in their entirety at https://osf.io/xv56k/ .

A comprehensive search of grey literature sources was also conducted. A list of the resources that were searched can be found at https://osf.io/xv56k/ . The grey literature searches were performed using custom web-scraping scripts. The search strings were tested per website before initiating web-scraping. An existing Google Chrome extension was needed to scrape dynamically generated websites.

The results from the databases and the grey literature searches were combined and de-duplicated using a Python script. Duplicates were detected using title, abstract and same year of publication, where year of publication was a match, where title cosine similarity was greater than 85%, and where abstracts cosine similarity was greater than 80% or one of the abstracts (or both) was empty. When duplicates were found, the results from the databases and the grey literature searches were combined and duplicates were removed.

Following de-duplication, each citation was analysed using a machine-learning model. The model added more than 30 new metadata fields, such as identifying populations, geographies, interventions and outcomes of interest. This allowed for accelerated identification of potential articles for exclusion at the title/abstract screening stage.

Study selection and eligibility criteria

Systematic review software, Covidence, was used for both title/abstract and full-text screening decision-making with two independent reviewers evaluating each item. Citations were included in this study if they met all of the inclusion criteria noted above. Studies that did not meet all the inclusion criteria were excluded. Exclusion criteria were the inverse of the inclusion criteria. Each citation that met one of the exclusion criteria at the title, abstract or full-text screening phases were excluded. Studies included in the full-text screening stage were those that met all inclusion criteria and none of the exclusion criteria, or those whose eligibility could not be established during title/abstract screening. Reasons for exclusion were documented at the full-text screening phase.

The retrieval of hundreds of PDFs for full-text screening was done with a combination of automated and manual methods. For the automated method, a Python script was created that would handle the tasks of PDF discovery, download and file renaming using Google Scholar. The script read the bibliographic data from an Excel spreadsheet and then executed a script to retrieve the full-text PDF. If the article is spotted in the search results, the download link is clicked, and the article will be auto-renamed and marked as being downloaded. Manual methods were employed for those items that were not retrieved using the script.

A total of 245 records were identified for full-text screening. This screening process led to the identification of 16 studies that were considered adequate regarding the content and methodological rigour. The PRISMA flow diagram (Fig. 1 ) shows the steps followed during the screening process and the number of items that resulted after each step.

Data extraction

Data extraction was based on interventions and outcomes established in the research question and exclusion criteria. The data extraction focused on the outcomes of the studies, the methods used to obtain the outcomes, and the validity and reliability of those methods using a data-extraction form. To reduce risk of bias related to the extracted data, two separate researchers extracted data from each included study in the full-text review step. When disagreements occurred between researchers on data extracted from a study, a third researcher was engaged to resolve conflict by extracting data again from the study and the results were compared with those found previously. In total, 31 conflicts were solved among the 261 reviews. The critical appraisal of individual sources of evidence gave an indication of the strength of evidence provided and informed the standards followed for this systematic review.

Reporting Summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Code availability

The code used in this study is available upon request.

Change history

20 october 2020.

An amendment to this paper has been published and can be accessed via a link at the top of the paper.

World Employment and Social Outlook 2019: Trends for Youth (International Labour Office, 2019).

World Youth Report: Youth and the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (United Nations, 2018); https://www.un.org/development/desa/youth/wp-content/uploads/sites/21/2018/12/WorldYouthReport-2030Agenda.pdf

Kilimani, N. Youth employment in developing economies: evidence on policies and interventions. IDS Bull. 48 , 13–32 (2017).

Google Scholar

Global Employment Trends for Youth: Special Issue on the Impact of the Global Economic Crisis on Youth (ILO, 2010).

Pieters, J. Youth Employment in LMIC (Institute of Labor Economics, 2013).

Yeboah, F. K. & Jayne, T. S. Africa’s evolving employment trends. J. Dev. Stud. 54 , 803–832 (2018).

Article Google Scholar

World Population Prospects 2019: Highlights ST/ESA/SER. A/423 (UN DESA, 2019).

Ellis, F. Rural Livelihoods and Diversity in LMIC (Oxford Univ. Press, 2000).

Pellegrini, L. & Tasciotti, L. Crop diversification, dietary diversity and agricultural income: empirical evidence from eight LMIC. Can. J. Dev. Stud. 35 , 211–227 (2014).

Employment by sex and age—ILO modelled estimates. ILOSTAT Database (International Labour Organization, accessed 14 February 2020); https://ilostat.ilo.org/data

Carletto, G. et al. Rural income generating activities in LMIC: re-assessing the evidence. Electron. J. Agric. Dev. Econ. 4 , 146–193 (2007).

Christiaensen, L., Demery, L. & Kuhl, J. The (evolving) role of agriculture in poverty reduction—an empirical perspective. J. Dev. Econ. 96 , 239–254 (2011).

Reducing Poverty and Hunger: The Critical Role of Financing for Food, Agriculture and Rural Development (FAO, 2002).

Eicher, C. K. In Strategies for African Development (eds Berg, R. J. & Whitaker, J. S.) 242–275 (Univ. California Press, 1986).

de Alan, B. & MH, S. Linkages between poverty, food security and undernutrition: evidence from China and India. China Agric. Econ. Rev. 7 , 655–667 (2015).

Sraboni, E., Malapit, H. J., Quisumbing, A. R. & Ahmed, A. U. Women’s empowerment in agriculture: what role for food security in Bangladesh? World Dev. 61 , 11–52 (2014).

Sharaunga, S., Mudhara, M. & Bogale, A. Effects of ‘women empowerment’ on household food security in rural KwaZulu‐Natal province. Dev. Policy Rev. 34 , 223–252 (2016).

Malapit, H. J. L. & Quisumbing, A. R. What dimensions of women’s empowerment in agriculture matter for nutrition in Ghana? Food Policy 52 , 54–63 (2015).

Sumberg, J., Anyidoho, N. A., Leavy, J., te Lintelo, D. J. & Wellard, K. Introduction: the young people and agriculture ‘problem’ in Africa. IDS Bull. 43 , 1–8 (2012).

Bezu, S. & Holden, S. Are rural youth in Ethiopia abandoning agriculture? World Dev. 64 , 259–272 (2014).

Tadele, G. & Gella, A. A. Becoming a Young Farmer in Ethiopia: Processes and Challenges Working Paper 83 (Future Agricultures, 2014).

Lindsjö, K., Mulwafu, W., Andersson Djurfeldt, A. & Joshua, M. K. Generational dynamics of agricultural intensification in Malawi: challenges for the youth and elderly smallholder farmers. Int. J. Agric. Sustain. https://doi.org/10.1080/14735903.2020.1721237 (2020).

Salvago, M. R., Phiboon, K., Faysse, N. & Nguyen, T. P. L. Young people’s willingness to farm under present and improved conditions in Thailand. Outlook Agric. 48 , 282–291 (2019).

Daum, T. Of bulls and bulbs: aspirations, opinions and perceptions of rural adolescents and youth in Zambia. Dev. Pract. 29 , 882–897 (2018).

Yeboah, T. et al. Hard work and hazard: young people and agricultural commercialisation in Africa. J. Rural Stud. 76 , 142–151 (2020).

Leavy, J. & Hossain, N. Who wants to farm? Youth aspirations, opportunities and rising food prices. IDS Working Papers https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2040-0209.2014.00439.x (2014).

Roser, M. & Ortiz-Ospina, E. Global education. Our World in Data https://ourworldindata.org/global-education (2016).

Gyimah-Brempong, K. & Kimenyi, M. S. Youth Policy and the Future of African Development (African Growth Initiative, 2013).

Foster, A. D. & Rosenzweig, M. R. Learning by doing and learning from others: human capital and technical change in agriculture. J. Political Econ. 103 , 1176–1209 (1995).

Eichhorst, W. & Rinne, U. An Assessment of the Youth Employment Inventory and Implications for Germany’s Development Policy (Institute of Labor Economics, 2015).

Betcherman, G. & Khan, T. Jobs for Africa’s expanding youth cohort: a stocktaking of employment prospects and policy interventions. IZA J. Dev. Migr. 8 , 13 (2018).

Alfonsi, L. et al. Tackling Youth Unemployment: Evidence from a Labour Market Experiment in Uganda (STICERD, LSE, 2017).

Lachaud, M. A., Bravo-Ureta, B. E., Fiala, N. & Gonzalez, S. P. The impact of agri-business skills training in Zimbabwe: an evaluation of the Training for Rural Economic Empowerment (TREE) programme. J. Dev. Effect. 10 , 373–391 (2018).

Cheteni, P. Youth participation in agriculture in the Nkonkobe District Municipality, South Africa. J. Hum. Ecol. 55 , 207–213 (2016).

Gambo Akpoko, J. & Kudi, T. M. Impact assessment of university-based rural youth agricultural extension out-reach program in selected villages of Kaduna-State, Nigeria. J. Apppl. Sci. 7 , 3292–3296 (2007).

Hudson, H. E., Leclair, M., Pelletier, B. & Sullivan, B. Using radio and interactive ICTs to improve food security among smallholder farmers in sub-Saharan Africa. Telecomm. Policy 41 , 670–684 (2017).

Ghana—Job Creation and Skills Development: Main Report (World Bank, 2009).

Baah, C. Assessment of the Youth in Agriculture Programme in Ejura-Sekyedumase District (Kwame Nkrumah Univ. Science and Technology, 2014).

Odongo, W., Kalule, S. W., Kule, E. K., Ndyomugyenyi, E. & Ongeng, D. Responsiveness of agricultural training curricula in African universities to labour market needs: the case of Gulu University in Uganda. African J. Rural Dev. 2 , 67–76 (2017).

Kinyanjui, W. & Noor, M. S. From waste to employment opportunities and wealth creation: a case study of utilization of livestock by-products in Hargeisa, Somaliland. Food Nutr. Sci. 4 , 1287–1292 (2013).

Latopa, A.-L. A. & Rashid, S. N. S. A. The impacts of integrated youth training farm as a capacity building center for youth agricultural empowerment in Kwara State, Nigeria. Mediterr. J. Soc. Sci. 6 , 524–532 (2015).

Shoulders, C. W., Barrick, R. K. & Myers, B. E. An assessment of the impact of internship programs in the agricultural technical schools of Egypt as perceived by participant groups. J. Int. Agric. Ext. Educ. 18 , 18–29 (2011).

Chakravarty, S., Lundberg, M., Nikolov, P. & Zenker, J. The Role of Training Programs for Youth Employment in Nepal: Impact Evaluation Report on the Employment Fund (World Bank, 2016).

Singh, K., Peshin, R. & Saini, S. K. Evaluation of the agricultural vocational training programmes conducted by the Krishi Vigyan Kendras (Farm Science Centres) in Indian Punjab. J. Agric. Rural Dev. Trop. Subtrop. 111 , 65–77 (2010).

Khosravipour, B. & Soleimanpour, M. R. Comparison of students’ entrepreneurship spirit in agricultural scientific-applied higher education centers of Iran. Am. J. Agric. Environ. Sci. 12 , 1012–1015 (2012).

Manalo, J. A. IV, Balmeo, K. P., Domingo, O. C. & Saludez, F. M. Young allies of agricultural extension: the infomediary campaign in Aurora, Philippines. Philipp. J. Crop Sci. 39 , 30–40 (2014).

Channal, G. P., Kotikal, Y. K. & Pattar, P. S. Empowering rural women as a successful entrepreneur—through Krishi Vigyan Kendra. Agric. Update 12 , 498–501 (2017).

Sterne, J. A. et al. ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ 355 , i4919 (2016).

How Does the Short-Term Training Program Contribute to Skills Development in Bangladesh? A Tracer Study of the Short-Term Training Graduates South Asia Region, Education Global Practice Discussion Paper (World Bank, 2015).

Nnadi, F. N. & Akwiwu, C. D. Determinants of youths’ participation in rural agriculture in Imo State, Nigeria. J. Appl. Sci. 8 , 328–333 (2008).

Article ADS Google Scholar

Akpan, S. B., Patrick, I. V., James, S. U. & Agom, D. I. Determinants of decision and participation of rural youth in agricultural production: a case study of youth in southern region of Nigeria. Russ. J. Agric. Socio-Econ. Sci. 7 , 35–48 (2015).

Adesugba, M. & Mavrotas, G. Youth Employment, Agricultural Transformation, and Rural Labour Dynamics in Nigeria (International Food Policy Research Institute, 2016).

Kluve, J. et al. Interventions to Improve the Labour Market Outcomes of Youth: A Systematic Review of Training, Entrepreneurship Promotion, Employment Services and Subsidized Employment Interventions (The Campbell Collaboration, 2017).

Literacy Rates Continues to Rise from One Generation to the Next (UNESCO Institute for Statistics, 2017).

Petticrew, M. & Roberts, H. Systematic Reviews in the Social Sciences: A Practical Guide (John Wiley & Sons, 2008).

Download references

Acknowledgements

We thank J.-A. Porciello and M. Eber-Rose for helpful comments on earlier drafts of this manuscript. We gratefully acknowledge funding support from Bundesministerium für Wirtschaftliche Zusammenarbeit und Entwicklung (Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development in Germany) and The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation as part of Ceres2030: Sustainable Solutions to End Hunger, a project administered by Cornell University, USA.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Université Norbert Zongo, Koudougou, Burkina Faso

W. H. Eugenie Maïga

Université Thomas Sankara, Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso

Mohamed Porgo, Pam Zahonogo, Doubahan Adeline Coulibaly & Salimata Traoré

Université Nationale d’Agriculture de Kétou, Kétou, Benin

Cocou Jaurès Amegnaglo

Institute of Development Studies–University of Sussex, Brighton, UK

Justin Flynn

Centre Universitaire Polytechnique de Kaya, Kaya, Burkina Faso

Windinkonté Seogo

University of Minnesota, Saint Paul, MN, USA

Julia A. Kelly

Information Training and Outreach Centre for Africa, Centurion, South Africa

Gracian Chimwaza

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

W.H.E.M., M.P. and P.Z. developed the research question. J.A.K. and G.C. conducted the literature search. All authors drafted the PRISMA-P protocol for this study. W.H.E.M., M.P., P.Z, C.J.A, D.A.C., J.F., W.S. and S.T. conducted the full-text reviews and drafted the paper, and all authors contributed to the writing.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to W. H. Eugenie Maïga .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information.

Supplementary Tables 1–4.

Supplementary Material 1

PRISMA protocol for the systematic review.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Maïga, W.H.E., Porgo, M., Zahonogo, P. et al. A systematic review of employment outcomes from youth skills training programmes in agriculture in low- and middle-income countries. Nat Food 1 , 605–619 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43016-020-00172-x

Download citation

Received : 23 December 2019

Accepted : 16 September 2020

Published : 12 October 2020

Issue Date : October 2020

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s43016-020-00172-x

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

African women and young people as agriculture service providers—business models, benefits, gaps and opportunities.

- Mariam Kadzamira

- Florence Chege

- Joseph Mulema

CABI Agriculture and Bioscience (2024)

A scoping review on the impacts of smallholder agriculture production on food and nutrition security: Evidence from Ethiopia context

- Hadas Temesgen

- Chanyalew Seyoum Aweke

Agriculture & Food Security (2023)

Accelerating evidence-informed decision-making for the Sustainable Development Goals using machine learning

- Jaron Porciello

- Maryia Ivanina

Nature Machine Intelligence (2020)

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing: Anthropocene newsletter — what matters in anthropocene research, free to your inbox weekly.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Unemployment among younger and older individuals: does conventional data about unemployment tell us the whole story?

Hila axelrad.

1 Center on Aging & Work, Boston College, Chestnut Hill, MA 02467 USA

2 The School of Social and Policy Studies, The Faculty of Social Sciences, Tel Aviv University, P.O. Box 39040, 6997801 Tel Aviv, Israel

3 Department of Public Policy & Administration, Guilford Glazer Faculty of Business & Management, Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, Beer Sheva, Israel

Israel Luski

4 Department of Economics, The Western Galilee College, Akko, Israel

In this research we show that workers aged 30–44 were significantly more likely than those aged 45–59 to find a job a year after being unemployed. The main contribution is demonstrating empirically that since older workers’ difficulties are related to their age, while for younger individuals the difficulties are more related to the business cycle, policy makers must devise different programs to address unemployment among young and older individuals. The solution to youth unemployment is the creation of more jobs, and combining differential minimum wage levels and earned income tax credits might improve the rate of employment for older individuals.

Introduction

Literature about unemployment references both the unemployment of older workers (ages 45 or 50 and over) and youth unemployment (15–24). These two phenomena differ from one another in their characteristics, scope and solutions.

Unemployment among young people begins when they are eligible to work. According to the International Labor Office (ILO), young people are increasingly having trouble when looking for their first job (ILO 2011 ). The sharp increase in youth unemployment and underemployment is rooted in long-standing structural obstacles that prevent many youngsters in both OECD countries and emerging economies from making a successful transition from school to work. Not all young people face the same difficulties in gaining access to productive and rewarding jobs, and the extent of these difficulties varies across countries. Nevertheless, in all countries, there is a core group of young people facing various combinations of high and persistent unemployment, poor quality jobs when they do find work and a high risk of social exclusion (Keese et al. 2013 ). The rate of youth unemployment is much higher than that of adults in most countries of the world (ILO 2011 ; Keese et al. 2013 ; O’Higgins 1997 ; Morsy 2012 ). Official youth unemployment rates in the early decade of the 2010s ranged from under 10% in Germany to around 50% in Spain ( http://www.indexmundi.com/g/r.aspx?v=2229 ; Pasquali 2012 ). The youngest employees, typically the newest, are more likely to be let go compared to older employees who have been in their jobs for a long time and have more job experience and job security (Furlong et al. 2012 ). However, although unemployment rates among young workers are relatively higher than those of older people, the period of time they spend unemployed is generally shorter than that of older adults (O’Higgins 2001 ).

We would like to argue that one of the most important determinants of youth unemployment is the economy’s rate of growth. When the aggregate level of economic activity and the level of adult employment are high, youth employment is also high. 1 Quantitatively, the employment of young people appears to be one of the most sensitive variables in the labor market, rising substantially during boom periods and falling substantially during less active periods (Freeman and Wise 1982 ; Bell and Blanchflower 2011 ; Dietrich and Möller 2016 ). Several explanations have been offered for this phenomenon. First, youth unemployment might be caused by insufficient skills of young workers. Another reason is a fall in aggregate demand, which leads to a decline in the demand for labor in general. Young workers are affected more strongly than older workers by such changes in aggregate demand (O’Higgins 2001 ). Thus, our first research question is whether young adults are more vulnerable to economic shocks compared to their older counterparts.

Older workers’ unemployment is mainly characterized by difficulties in finding a new job for those who have lost their jobs (Axelrad et al. et al. 2013 ). This fact seems counter-intuitive because older workers have the experience and accumulated knowledge that the younger working population lacks. The losses to society and the individuals are substantial because life expectancy is increasing, the retirement age is rising in many countries, and people are generally in good health (Axelrad et al. 2013 ; Vodopivec and Dolenc 2008 ).

The difficulty that adults have in reintegrating into the labor market after losing their jobs is more severe than that of the younger unemployed. Studies show that as workers get older, the duration of their unemployment lengthens and the chances of finding a job decline (Böheim et al. 2011 ; De Coen et al. 2010 ). Therefore, our second research question is whether older workers’ unemployment stems from their age.

In this paper, we argue that the unemployment rates of young people and older workers are often misinterpreted. Even if the data show that unemployment rates are higher among young people, such statistics do not necessarily imply that it is harder for them to find a job compared to older individuals. We maintain that youth unemployment stems mainly from the characteristics of the labor market, not from specific attributes of young people. In contrast, the unemployment of older individuals is more related to their specific characteristics, such as higher salary expectations, higher labor costs and stereotypes about being less productive (Henkens and Schippers 2008 ; Keese et al. 2006 ). To test these hypotheses, we conduct an empirical analysis using statistics from the Israeli labor market and data published by the OECD. We also discuss some policy implications stemming from our results, specifically, a differential policy of minimum wages and earned income tax credits depending on the worker’s age.

Following the introduction and literary review, the next part of our paper presents the existing data about the unemployment rates of young people and adults in the OECD countries in general and Israel in particular. Than we present the research hypotheses and theoretical model, we describe the data, variables and methods used to test our hypotheses. The regression results are presented in Sect. 4 , the model of Business Cycle is presented in Sect. 5 , and the paper concludes with some policy implications, a summary and conclusions in Sect. 6 .

Literature review

Over the past 30 years, unemployment in general and youth unemployment in particular has been a major problem in many industrial societies (Isengard 2003 ). The transition from school to work is a rather complex and turbulent period. The risk of unemployment is greater for young people than for adults, and first jobs are often unstable and rather short-lived (Jacob 2008 ). Many young people have short spells of unemployment during their transition from school to work; however, some often get trapped in unemployment and risk becoming unemployed in the long term (Kelly et al. 2012 ).

Youth unemployment leads to social problems such as a lack of orientation and hostility towards foreigners, which in turn lead to increased social expenditures. At the societal level, high youth unemployment endangers the functioning of social security systems, which depend on a sufficient number of compulsory payments from workers in order to operate (Isengard 2003 ).

Workers 45 and older who have lost their jobs often encounter difficulties in finding a new job (Axelrad et al. 2013 ; Marmora and Ritter 2015 ) although today they are more able to work longer than in years past (Johnson 2004 ). In addition to the monetary rewards, work also offers mental and psychological benefits (Axelrad et al. 2016 ; Jahoda 1982 ; Winkelmann and Winkelmann 1998 ). Working at an older age may contribute to an individual’s mental acuity and provide a sense of usefulness.

On average, throughout the OECD, the hiring rate of workers aged 50 and over is less than half the rate for workers aged 25–49. The low re-employment rates among older job seekers reflect, among other things, the reluctance of employers to hire older workers. Lahey ( 2005 ) found evidence of age discrimination against older workers in labor markets. Older job applicants (aged 50 or older), are treated differently than younger applicants. A younger worker is more than 40% more likely to be called back for an interview compared to an older worker. Age discrimination is also reflected in the time it takes for older adults to find a job. Many workers aged 45 or 50 and older who have lost their jobs often encounter difficulties in finding a new job, even if they are physically and intellectually fit (Hendels 2008 ; Malul 2009 ). Despite the fact that older workers are considered to be more reliable (McGregor and Gray 2002 ) and to have better business ethics, they are perceived as less flexible or adaptable, less productive and having higher salary expectations (Henkens and Schippers 2008 ). Employers who hesitated in hiring older workers also mentioned factors such as wages and non-wage labor costs that rise more steeply with age and the difficulties firms may face in adjusting working conditions to meet the requirements of employment protection rules (Keese et al. 2006 ).

Thus, we have a paradox. On one hand, people live longer, the retirement age is rising, and older people in good health want or need to keep working. At the same time, employers seek more and more young workers all the time. This phenomenon might marginalize skilled and experience workers, and take away their ability to make a living and accrue pension rights. Thus, employers’ reluctance to hire older workers creates a cycle of poverty and distress, burdening the already overcrowded social institutions and negatively affecting the economy’s productivity and GDP (Axelrad et al. 2013 ).

OECD countries during the post 2008 crisis

The recent global economic crisis took an outsized toll on young workers across the globe, especially in advanced economies, which were hit harder and recovered more slowly than emerging markets and developing economies. Does this fact imply that the labor market in Spain and Portugal (with relatively high youth unemployment rates) is less “friendly” toward younger individuals than the labor market in Israel and Germany (with a relatively low youth unemployment rate)? Has the market in Spain and Portugal become less “friendly” toward young people during the last 4 years? We argue that the main factor causing the increasing youth unemployment rates in Spain and Portugal is the poor state of the economy in the last 4 years in these countries rather than a change in attitudes toward hiring young people.

OECD data indicate that adult unemployment is significantly lower than youth unemployment. The global economic crisis has hit young people very hard. In 2010, there were nearly 15 million unemployed youngsters in the OECD area, about four million more than at the end of 2007 (Scarpetta et al. 2010 ).

From an international perspective, and unlike other developed countries, Israel has a young age structure, with a high birthrate and a small fraction of elderly population. Israel has a mandatory retirement age, which differs for men (67) and women (62), and the labor force participation of older workers is relatively high (Stier and Endeweld 2015 ), therefore, we believe that Israel is an interesting case for studying.

The Israeli labor market is extremely flexible (e.g. hiring and firing are relatively easy), and mobile (workers can easily move between jobs) (Peretz 2016 ). Focusing on Israel’s labor market, we want to check whether this is true for older Israeli workers as well, and whether there is a difference between young and older workers.

The problem of unemployment among young people in Israel is less severe than in most other developed countries. This low unemployment rate is a result of long-term processes that have enabled the labor market to respond relatively quickly to changes in the economic environment and have reduced structural unemployment. 2 Furthermore, responsible fiscal and monetary policies, and strong integration into the global market have also promoted employment at all ages. With regard to the differences between younger and older workers in Israel, Stier and Endeweld ( 2015 ) determined that older workers, men and women alike, are indeed less likely to leave their jobs. This finding is similar to other studies showing that older workers are less likely to move from one employer to another. According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, the median employee tenure is generally higher among older workers than younger ones (BLS 2014 ). Movement in and out of the labor market is highest among the youngest workers. However, these young people are re-employed quickly, while older workers have the hardest time finding jobs once they become unemployed. The Bank of Israel calculated the chances of unemployed people finding work between two consecutive quarters using a panel of the Labor Force Survey for the years 1996–2011. Their calculations show that since the middle of the last decade the chances of unemployed people finding a job between two consecutive quarters increased. 3 However, as noted earlier, as workers age, the duration of their unemployment lengthens. Prolonged unemployment erodes the human capital of the unemployed (Addison et al. 2004 ), which has a particularly deleterious effect on older workers. Thus, the longer the period of unemployment of older workers, the less likely they will find a job (Axelrad and Luski 2017 ). Nevertheless, as Fig. 1 shows, the rates of youth unemployment in Israel are higher than those of older workers.

Unemployed persons and discouraged workers as percentages of the civilian labor force, by age group (Bank of Israel 2011 ). We excluded those living outside settled communities or in institutions. The percentages of discouraged workers are calculated from the civilian labor force after including them in it

(Source: Calculated by the authors by using data from the Labor Force survey of the Israeli CBS, 2011)

We argue that the main reason for this situation is the status quo in the labor market, which is general and not specific to Israel. It applies both to older workers and young workers who have a job. The status quo is evident in the situation in which adults (and young people) already in the labor market manage to keep their jobs, making the entrance of new young people into the labor market more difficult. What we are witnessing is not evidence of a preference for the old over the young, but the maintaining of the status quo.

The rate of employed Israelis covered by collective bargaining agreements increases with age: up to age 35, the rate is less than one-quarter, and between 50 and 64 the rate reaches about one-half. In effect, in each age group between 25 and 60, there are about 100,000 covered employees, and the lower coverage rate among the younger ages derives from the natural growth in the cohorts over time (Bank of Israel 2013 ). The wave of unionization in recent years is likely to change only the age profile of the unionization rate and the decline in the share of covered people over the years, to the extent that it strengthens and includes tens of thousands more employees from the younger age groups. 4

The fact that the percentage of employees covered by collective agreement increases with age implies that there is a status quo effect. Older workers are protected by collective agreements, and it is hard to dismiss them (Culpepper 2002 ; Palier and Thelen 2010 ). However, young workers enter the workforce with individual contracts and are not protected, making it is easier to change their working conditions and dismiss them.