Search on OralHistory.ws Blog

The French Revolution: Liberty, Equality, and Fraternity

From 1789 to 1799, the French Revolution stands as one of the most pivotal episodes in world history. This tumultuous decade witnessed the dramatic overthrow of the Bourbon monarchy, the rise of radical political factions, and the eventual ascent of Napoleon Bonaparte. Rooted deeply in the Enlightenment ideals, the revolution was more than just a change in political leadership. It signified a profound metamorphosis of societal values, marked prominently by the revolutionary triad: Liberty, Equality, and Fraternity. These guiding principles did not merely serve as ideological rallying cries but were the bedrock upon which the new republic was built. Through a nuanced exploration of these core tenets, this essay will elucidate the essence of the French Revolution and its enduring imprint on the annals of democratic thought.

Table of content

Liberty – Breaking the Chains

Liberty, the very lifeblood of the French Revolution, embodied the deep-seated yearning of a populace stifled under absolute monarchy. This was not a fleeting desire but a fervent aspiration that echoed through the streets of Paris and the countryside of France alike.

Pre-revolutionary France was characterized by an entrenched system of royal absolutism, where the Bourbon kings wielded unchallenged power. Their unchecked authority, rampant corruption, and regressive taxation cultivated an environment of suffocation. The Enlightenment thinkers, such as Voltaire and Rousseau, sowed the seeds of liberty in the minds of the French. They championed the idea that individuals had inalienable rights, free from the whims and fancies of monarchs.

The storming of the Bastille, while a physical act, bore symbolic weight. It was not just dismantling a fortress prison but a resounding message against oppression. Liberty evolved from an abstract concept to concrete legislative reforms as the Revolution progressed. The suppression of censorship, the proclamation of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen, and the gradual diminishing of the king’s power were tangible manifestations of this pursuit.

However, it is crucial to note that this road to liberty was fraught with challenges. While the revolution sought to free the citizenry from the shackles of the old regime, new chains of radical factions and the Reign of Terror emerged. Nevertheless, once ignited, the spirit of liberty refused to be extinguished. Even amidst the revolution’s darkest hours, the flame of liberty continued to burn, guiding the nation toward a more democratic future.

Equality – Leveling the Field

The clarion call for Equality during the French Revolution was more than just a repudiation of the aristocratic privileges; it was a radical reimagining of societal structures. The ancien régime had perpetuated a stratified society where birthright and lineage overshadowed merit and individual capability. This systemic inequality was entrenched in the legal and political fabric and deeply woven into France’s cultural and social tapestry.

With its archaic representation, the Estates-General was a glaring example of this inequity. The First and Second Estates, representing the clergy and nobility, respectively, enjoyed disproportionate influence despite being a minuscule fraction of the population. In contrast, the Third Estate, representing most of the populace, was marginalized. The growing resentment of this imbalance paved the way for the revolutionaries to demand a more equitable society.

Revolutionary reforms sought to dismantle these outdated hierarchies. The abolition of feudalism in 1789 marked a seismic shift, toppling centuries-old structures of serfdom and manorial rights. Likewise, the Civil Constitution of the Clergy sought to break the ecclesiastical stronghold, making the Church subordinate to the state. This transformative period also witnessed the rise of the bourgeoisie, as wealth and education began to rival, if not surpass, nobility as markers of societal status.

However, the quest for equality was a double-edged sword. As much as the revolution aimed to flatten societal disparities, it also grappled with internal contradictions. The Reign of Terror, while championing the cause of the common man, often veered into a despotic purge of perceived counter-revolutionaries. This underscores the complexity of the revolution’s pursuit of equality: an aspiration both noble in its intent and intricate in its execution.

Fraternity – A Unified Nation

Fraternity, often overshadowed by the more tangible tenets of Liberty and Equality, played an integral role in shaping the ethos of the French Revolution. At its core, Fraternity evoked a sense of communal belonging, a shared destiny, and a collective purpose. It was not just about fostering bonds among citizens but was a call to stitch together a nation fragmented by centuries of divisions.

Before the Revolution, France was not the homogenous entity we envision today. It was a patchwork of regions, dialects, customs, and allegiances. While unifying to an extent, the Bourbon monarchy often played one faction against another, exacerbating regional and class distinctions for political gains.

The Revolution sought to mend these fractures. Fraternity became the rallying cry for creating a cohesive national identity. This was not just a sentiment but actualized through policies and symbols. The adoption of “La Marseillaise” as the national anthem, the establishment of a unified legal code in the form of the Napoleonic Code, and the promotion of the French language at the expense of regional dialects were all geared towards forging a united France.

However, the road to fraternity was not without its paradoxes. The desire for a unified nation sometimes clashed with recognizing individual and regional identities. The de-Christianization campaigns, while aimed at reducing the Church’s influence, alienated many devout citizens. Similarly, the aggressive promotion of French as the lingua franca often came at the expense of regional identities and cultures.

Nevertheless, despite these challenges, the spirit of Fraternity endured. The French Revolution may have been tumultuous and, at times, contradictory, but its emphasis on a united national identity laid the groundwork for the modern French nation-state. It served as a testament to the enduring human desire to belong, connect, and forge a shared destiny.

The French Revolution, with its whirlwind of events, ideologies, and personalities, remains a seminal chapter in the annals of history. Through its embrace of Liberty, Equality, and Fraternity, it not only redefined the contours of French society but also set a precedent for global movements advocating democratic principles.

In dissecting these tenets, we are offered a lens through which the revolution’s multifaceted nature becomes evident. Liberty, with its call for personal freedoms, was both an aspiration and a challenge constantly sought after and fought for in the face of evolving threats. Equality, a demand for societal leveling, was an endeavor to bridge the yawning chasm between the elite and the commoner, reimagining the societal structures that had held sway for centuries. Fraternity, perhaps the most nuanced of the three, sought to weave a tapestry of shared identity from the disparate threads of regional, class, and religious affiliations.

Nevertheless, beyond the theoretical lies the pragmatic. The French Revolution was not a linear progression of ideals but a crucible where these principles were tested, redefined, and, at times, compromised. It was a testament to the complexities of nation-building and the intricacies of balancing individual rights with collective responsibility.

As we reflect upon the legacy of the revolution, its resonances are palpable even today. From the Arab Spring to civil rights movements, the echoes of Liberty, Equality, and Fraternity reverberate, reminding us of the universality of these aspirations. The French Revolution, thus, is not just a historical event confined to textbooks but a living testament to humanity’s relentless quest for a more just, equitable, and united world.

History Cooperative

French Revolution: History, Timeline, Causes, and Outcomes

The French Revolution, a seismic event that reshaped the contours of political power and societal norms, began in 1789, not merely as a chapter in history but as a dramatic upheaval that would influence the course of human events far beyond its own time and borders.

It was more than a clash of ideologies; it was a profound transformation that questioned the very foundations of monarchical rule and aristocratic privilege, leading to the rise of republicanism and the concept of citizenship.

The causes of this revolution were as complex as its outcomes were far-reaching, stemming from a confluence of economic strife, social inequalities, and a hunger for political reform.

The outcomes of the French Revolution, embedded in the realms of political thought, civil rights, and societal structures, continue to resonate, offering invaluable insights into the power and potential of collective action for change.

Table of Contents

Time and Location

The French Revolution, a cornerstone event in the annals of history, ignited in 1789, a time when Europe was dominated by monarchical rule and the vestiges of feudalism. This epochal period, which spanned a decade until the late 1790s, witnessed profound social, political, and economic transformations that not only reshaped France but also sent shockwaves across the continent and beyond.

Paris, the heart of France, served as the epicenter of revolutionary activity , where iconic events such as the storming of the Bastille became symbols of the struggle for freedom. Yet, the revolution was not confined to the city’s limits; its influence permeated through every corner of France, from bustling urban centers to serene rural areas, each witnessing the unfolding drama of revolution in unique ways.

The revolution consisted of many complex factions, each representing a distinct set of interests and ideologies. Initially, the conflict arose between the Third Estate, which included a diverse group from peasants and urban laborers to the bourgeoisie, and the First and Second Estates, made up of the clergy and the nobility, respectively.

The Third Estate sought to dismantle the archaic social structure that relegated them to the burden of taxation while denying them political representation and rights. Their demands for reform and equality found resonance across a society strained by economic distress and the autocratic rule of the monarchy.

As the revolution evolved, so too did the nature of the conflict. The initial unity within the Third Estate fractured, giving rise to factions such as the Jacobins and Girondins, who, despite sharing a common revolutionary zeal, diverged sharply in their visions for France’s future.

The Jacobins , with figures like Maximilien Robespierre at the helm, advocated for radical measures, including the abolition of the monarchy and the establishment of a republic, while the Girondins favored a more moderate approach.

The sans-culottes , representing the militant working-class Parisians, further complicated the revolutionary landscape with their demands for immediate economic relief and political reforms.

The revolution’s adversaries were not limited to internal factions; monarchies throughout Europe viewed the republic with suspicion and hostility. Fearing the spread of revolutionary fervor within their own borders, European powers such as Austria, Prussia, and Britain engaged in military confrontations with France, aiming to restore the French monarchy and stem the tide of revolution.

These external threats intensified the internal strife, fueling the revolution’s radical phase and propelling it towards its eventual conclusion with the rise of Napoleon Bonaparte, who capitalized on the chaos to establish his own rule.

READ MORE: How Did Napoleon Die: Stomach Cancer, Poison, or Something Else?

Causes of the French Revolution

The French Revolution’s roots are deeply embedded in a confluence of political, social, economic, and intellectual factors that, over time, eroded the foundations of the Ancien Régime and set the stage for revolutionary change.

At the heart of the revolution were grievances that transcended class boundaries, uniting much of the nation in a quest for profound transformation.

Economic Hardship and Social Inequality

A critical catalyst for the revolution was France’s dire economic condition. Fiscal mismanagement, costly involvement in foreign wars (notably the American Revolutionary War), and an antiquated tax system placed an unbearable strain on the populace, particularly the Third Estate, which bore the brunt of taxation while being denied equitable representation.

Simultaneously, extravagant spending by Louis XVI and his predecessors further drained the national treasury, exacerbating the financial crisis.

The social structure of France, rigidly divided into three estates, underscored profound inequalities. The First (clergy) and Second (nobility) Estates enjoyed significant privileges, including exemption from many taxes, which contrasted starkly with the hardships faced by the Third Estate, comprising peasants , urban workers, and a rising bourgeoisie.

This disparity fueled resentment and a growing demand for social and economic justice.

Enlightenment Ideals

The Enlightenment , a powerful intellectual movement sweeping through Europe, profoundly influenced the revolutionary spirit. Philosophers such as Voltaire, Rousseau, and Montesquieu criticized traditional structures of power and authority, advocating for principles of liberty, equality, and fraternity.

Their writings inspired a new way of thinking about governance, society, and the rights of individuals, sowing the seeds of revolution among a populace eager for change.

Political Crisis and the Estates-General

The immediate catalyst for the French Revolution was deeply rooted in a political crisis, underscored by the French monarchy’s chronic financial woes. King Louis XVI, facing dire fiscal insolvency, sought to break the deadlock through the convocation of the Estates-General in 1789, marking the first assembly of its kind since 1614.

This critical move, intended to garner support for financial reforms, unwittingly set the stage for widespread political upheaval. It provided the Third Estate, representing the common people of France, with an unprecedented opportunity to voice their longstanding grievances and demand a more significant share of political authority.

The Third Estate, comprising a vast majority of the population but long marginalized in the political framework of the Ancien Régime, seized this moment to assert its power. Their transformation into the National Assembly was a monumental shift, symbolizing a rejection of the existing social and political order.

The catalyst for this transformation was their exclusion from the Estates-General meeting, leading them to gather in a nearby tennis court. There, they took the historic Tennis Court Oath, vowing not to disperse until France had a new constitution.

This act of defiance was not just a political statement but a clear indication of the revolutionaries’ resolve to overhaul French society.

Amidst this burgeoning crisis, the personal life of Marie Antoinette , Louis XVI’s queen, became a focal point of public scrutiny and scandal.

Married to Louis at the tender age of fourteen, Marie Antoinette, the youngest daughter of Holy Roman Emperor Francis I, was known for her lavish lifestyle and the preferential treatment she accorded her friends and relatives.

READ MORE: Roman Emperors in Order: The Complete List from Caesar to the Fall of Rome

Her disregard for traditional court fashion and etiquette, along with her perceived extravagance, made her an easy target for public criticism and ridicule. Popular songs in Parisian cafés and a flourishing genre of pornographic literature vilified the queen, accusing her of infidelity, corruption, and disloyalty.

Such depictions, whether grounded in truth or fabricated, fueled the growing discontent among the populace, further complicating the already tense political atmosphere.

The intertwining of personal scandals with the broader political crisis highlighted the deep-seated issues within the French monarchy and aristocracy, contributing to the revolutionary fervor.

As the political crisis deepened, the actions of the Third Estate and the controversies surrounding Marie Antoinette exemplified the widespread desire for change and the rejection of the Ancient Régime’s corruption and excesses.

Key Concepts, Events, and People of the French Revolution

As the Estates General convened in 1789, little did the world know that this gathering would mark the beginning of a revolution that would forever alter the course of history.

Through the rise and fall of factions, the clash of ideologies, and the leadership of remarkable individuals, this era reshaped not only France but also set a precedent for future generations.

From the storming of the Bastille to the establishment of the Directory, each event and figure played a crucial role in crafting a new vision of governance and social equality.

Estates General

When the Estates General was summoned in May 1789, it marked the beginning of a series of events that would catalyze the French Revolution. Initially intended as a means for King Louis XVI to address the financial crisis by securing support for tax reforms, the assembly instead became a flashpoint for broader grievances.

Representing the three estates of French society—the clergy, the nobility, and the commoners—the Estates General highlighted the profound disparities and simmering tensions between these groups.

The Third Estate, comprising 98% of the population but traditionally having the least power, seized the moment to push for more significant reforms, challenging the very foundations of the Ancient Régime.

The deadlock over voting procedures—where the Third Estate demanded votes be counted by head rather than by estate—led to its members declaring themselves the National Assembly, an act of defiance that effectively inaugurated the revolution.

This bold step, coupled with the subsequent Tennis Court Oath where they vowed not to disperse until a new constitution was created, underscored a fundamental shift in authority from the monarchy to the people, setting a precedent for popular sovereignty that would resonate throughout the revolution.

Rise of the Third Estate

The Rise of the Third Estate underscores the growing power and assertiveness of the common people of France. Fueled by economic hardship, social inequality, and inspired by Enlightenment ideals, this diverse group—encompassing peasants, urban workers, and the bourgeoisie—began to challenge the existing social and political order.

Their transformation from a marginalized majority into the National Assembly marked a radical departure from traditional power structures, asserting their role as legitimate representatives of the French people. This period was characterized by significant political mobilization and the formation of popular societies and clubs, which played a crucial role in spreading revolutionary ideas and organizing action.

This newfound empowerment of the Third Estate culminated in key revolutionary acts, such as the storming of the Bastille in July 1789, a symbol of royal tyranny. This event not only demonstrated the power of popular action but also signaled the irreversible nature of the revolutionary movement.

The rise of the Third Estate paved the way for the abolition of feudal privileges and the drafting of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen , foundational texts that sought to establish a new social and political order based on equality, liberty, and fraternity.

A People’s Monarchy

The concept of a People’s Monarchy emerged as a compromise in the early stages of the French Revolution, reflecting the initial desire among many revolutionaries to retain the monarchy within a constitutional framework.

This period was marked by King Louis XVI’s grudging acceptance of the National Assembly’s authority and the enactment of significant reforms, including the Civil Constitution of the Clergy and the Constitution of 1791, which established a limited monarchy and sought to redistribute power more equitably.

However, this attempt to balance revolutionary demands with monarchical tradition was fraught with difficulties, as mutual distrust between the king and the revolutionaries continued to escalate.

The failure of the People’s Monarchy was precipitated by the Flight to Varennes in June 1791, when Louis XVI attempted to escape France and rally foreign support for the restoration of his absolute power.

This act of betrayal eroded any remaining support for the monarchy among the populace and the Assembly, leading to increased calls for the establishment of a republic.

The people’s experiment with a constitutional monarchy thus served to highlight the irreconcilable differences between the revolutionary ideals of liberty and equality and the traditional monarchical order, setting the stage for the republic’s proclamation.

Birth of a Republic

The proclamation of the First French Republic in September 1792 represented a radical departure from centuries of monarchical rule, embodying the revolutionary ideals of liberty, equality, and fraternity.

This transition was catalyzed by escalating political tensions, military challenges, and the radicalization of the revolution, particularly after the king’s failed flight and perceived betrayal.

The Republic’s birth was a moment of immense optimism and aspiration, as it promised to reshape French society on the principles of democratic governance and civic equality. It also marked the beginning of a new calendar, symbolic of the revolutionaries’ desire to break completely with the past and start anew.

However, the early years of the Republic were marked by significant challenges, including internal divisions, economic struggles, and threats from monarchist powers in Europe.

These pressures necessitated the establishment of the Committee of Public Safety and the Reign of Terror, measures aimed at defending the revolution but which also led to extreme political repression.

Reign of Terror

The Reign of Terror, from September 1793 to July 1794, remains one of the most controversial and bloodiest periods of the French Revolution. Under the auspices of the Committee of Public Safety, led by figures such as Maximilien Robespierre, the French government adopted radical measures to purge the nation of perceived enemies of the revolution.

This period saw the widespread use of the guillotine , with thousands executed on charges of counter-revolutionary activities or mere suspicion of disloyalty. The Terror aimed to consolidate revolutionary gains and protect the nascent Republic from internal and external threats, but its legacy is marred by the extremity of its actions and the climate of fear it engendered.

The end of the Terror came with the Thermidorian Reaction on 27th July 1794 (9th Thermidor Year II, according to the revolutionary calendar), which resulted in the arrest and execution of Robespierre and his closest allies.

This marked a significant turning point, leading to the dismantling of the Committee of Public Safety and the gradual relaxation of emergency measures. The aftermath of the Terror reflected a society grappling with the consequences of its radical actions, seeking stability after years of upheaval but still committed to the revolutionary ideals of liberty and equality .

Thermidorians and the Directory

Following the Thermidorian Reaction , the political landscape of France underwent significant changes, leading to the establishment of the Directory in November 1795.

This new government, a five-member executive body, was intended to provide stability and moderate the excesses of the previous radical phase. The Directory period was characterized by a mix of conservative and revolutionary policies, aimed at consolidating the Republic and addressing the economic and social issues that had fueled the revolution.

Despite its efforts to navigate the challenges of governance, the Directory faced significant opposition from royalists on the right and Jacobins on the left, leading to a period of political instability and corruption.

The Directory’s inability to resolve these tensions and its growing unpopularity set the stage for its downfall. The coup of 18 Brumaire in November 1799, led by Napoleon Bonaparte, ended the Directory and established the Consulate, marking the end of the revolutionary government and the beginning of Napoleonic rule.

While the Directory failed to achieve lasting stability, it played a crucial role in the transition from radical revolution to the establishment of a more authoritarian regime, highlighting the complexities of revolutionary governance and the challenges of fulfilling the ideals of 1789.

French Revolution End and Outcome: Napoleon’s Rise

The revolution’s end is often marked by Napoleon’s coup d’état on 18 Brumaire , which not only concluded a decade of political instability and social unrest but also ushered in a new era of governance under his rule.

This period, while stabilizing France and bringing much-needed order, seemed to contradict the revolution’s initial aims of establishing a democratic republic grounded in the principles of liberty, equality, and fraternity.

Napoleon’s rise to power, culminating in his coronation as Emperor, symbolizes a complex conclusion to the revolutionary narrative, intertwining the fulfillment and betrayal of its foundational ideals.

Evaluating the revolution’s success requires a nuanced perspective. On one hand, it dismantled the Ancien Régime, abolished feudalism, and set forth the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, laying the cornerstone for modern democracy and human rights.

These achievements signify profound societal and legal transformations that resonated well beyond France’s borders, influencing subsequent movements for freedom and equality globally.

On the other hand, the revolution’s trajectory through the Reign of Terror and the subsequent rise of a military dictatorship under Napoleon raises questions about the cost of these advances and the ultimate realization of the revolution’s goals.

The French Revolution’s conclusion with Napoleon Bonaparte’s ascension to power is emblematic of its complex legacy. This period not only marked the cessation of years of turmoil but also initiated a new chapter in French governance, characterized by stability and reform yet marked by a departure from the revolution’s original democratic aspirations.

The Significance of the French Revolution

The French Revolution holds a place of prominence in the annals of history, celebrated for its profound impact on the course of modern civilization. Its fame stems not only from the dramatic events and transformative ideas it unleashed but also from its enduring influence on political thought, social reform, and the global struggle for justice and equality.

This period of intense upheaval and radical change challenged the very foundations of society, dismantling centuries-old institutions and laying the groundwork for a new era defined by the principles of liberty, equality, and fraternity.

At its core, the French Revolution was a manifestation of human aspiration towards freedom and self-determination, a vivid illustration of the power of collective action to reshape the world. It introduced revolutionary concepts of citizenship and rights that have since become the bedrock of democratic societies.

Moreover, the revolution’s ripple effects were felt worldwide, inspiring a wave of independence movements and revolutions across Europe, Latin America, and beyond. Its legacy is a testament to the idea that people have the power to overthrow oppressive systems and construct a more equitable society.

The revolution’s significance also lies in its contributions to political and social thought. It was a living laboratory for ideas that were radical at the time, such as the separation of church and state, the abolition of feudal privileges, and the establishment of a constitution to govern the rights and duties of the French citizens.

These concepts, debated and implemented with varying degrees of success during the revolution, have become fundamental to modern governance.

Furthermore, the French Revolution is famous for its dramatic and symbolic events, from the storming of the Bastille to the Reign of Terror, which have etched themselves into the collective memory of humanity.

These events highlight the complexities and contradictions of the revolutionary process, underscoring the challenges inherent in profound societal transformation.

Key Figures of the French Revolution

The French Revolutions were painted by the actions and ideologies of several key figures whose contributions defined the era. These individuals, with their diverse roles and perspectives, were central in navigating the revolution’s trajectory, capturing the complexities and contradictions of this tumultuous period.

Maximilien Robespierre , often synonymous with the Reign of Terror, was a figure of paradoxes. A lawyer and politician, his early advocacy for the rights of the common people and opposition to absolute monarchy marked him as a champion of liberty.

However, as a leader of the Committee of Public Safety, his name became associated with the radical phase of the revolution, characterized by extreme measures in the name of safeguarding the republic. His eventual downfall and execution reflect the revolution’s capacity for self-consumption.

Georges Danton , another prominent revolutionary leader, played a crucial role in the early stages of the revolution. Known for his oratory skills and charismatic leadership, Danton was instrumental in the overthrow of the monarchy and the establishment of the First French Republic.

Unlike Robespierre, Danton is often remembered for his pragmatism and efforts to moderate the revolution’s excesses, which ultimately led to his execution during the Reign of Terror, highlighting the volatile nature of revolutionary politics.

Louis XVI, the king at the revolution’s outbreak, represents the Ancient Régime’s complexities and the challenges of monarchical rule in a time of profound societal change.

His inability to effectively manage France’s financial crisis and his hesitancy to embrace substantial reforms contributed to the revolutionary fervor. His execution in 1793 symbolized the revolution’s radical break from monarchical tradition and the birth of the republic.

Marie Antoinette, the queen consort of Louis XVI, became a symbol of the monarchy’s extravagance and disconnect from the common people. Her fate, like that of her husband, underscores the revolution’s rejection of the old order and the desire for a new societal structure based on equality and merit rather than birthright.

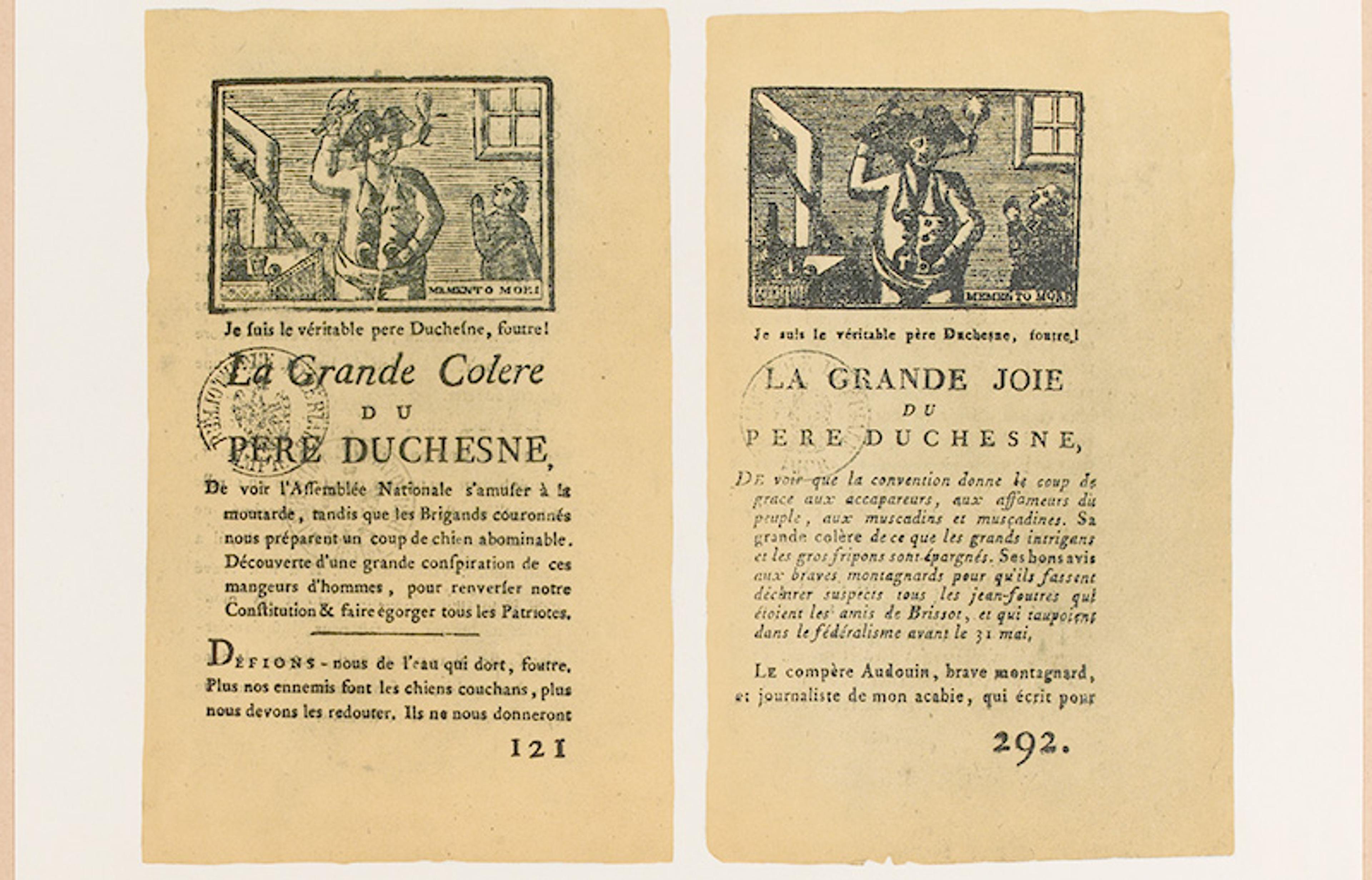

Jean-Paul Marat , a journalist and politician, used his publication, L’Ami du Peuple, to advocate for the rights of the lower classes and to call for radical measures against the revolution’s enemies.

His assassination by Charlotte Corday, a Girondin sympathizer, in 1793 became one of the revolution’s most famous episodes, illustrating the deep divisions within revolutionary France.

Finally, Napoleon Bonaparte, though not a leader during the revolution’s peak, emerged from its aftermath to shape France’s future. A military genius, Napoleon used the opportunities presented by the revolution’s chaos to rise to power, eventually declaring himself Emperor of the French.

His reign would consolidate many of the revolution’s reforms while curtailing its democratic aspirations, embodying the complexities of the revolution’s legacy.

These key figures, among others, played significant roles in the unfolding of the French Revolution. Their contributions, whether for the cause of liberty, the maintenance of order, or the pursuit of personal power, highlight the multifaceted nature of the revolution and its enduring impact on history.

References:

(1) Schama, Simon. Citizens: a Chronicle of the French Revolution. New York, Random House, 1990, pp. 119-221.

(2) Doyle, William. Oxford History of the French Revolution. Oxford University Press, 1989, pp. 11-12

(3) Hobsbawm, Eric. The Age of Revolution. Vintage Books, 1996, pp. 56-57.

(4) Doyle, William. Oxford History of the French Revolution. Oxford University Press, 1989, pp. 24-25

(5) Lewis, Gwynne. The French Revolution: Rethinking the Debate. Routledge, 2016, pp. 12-14.

(6) Doyle, William. Oxford History of the French Revolution. Oxford University Press, 1989, pp. 14-25

(7) Doyle, William. Oxford History of the French Revolution. Oxford University Press, 1989, pp. 63-65.

(8) Schama, Simon. Citizens: a Chronicle of the French Revolution. New York, Random House, 1990, pp. 242-244.

(9) Doyle, William. Oxford History of the French Revolution. Oxford University Press, 1989, pp. 74.

(10) Doyle, William. Oxford History of the French Revolution. Oxford University Press, 1989, pp. 82 – 84.

(11) Lewis, Gwynne. The French Revolution: Rethinking the Debate. Routledge, 2016, p. 20.

(12) Hampson, Norman. A Social History of the French Revolution. University of Toronto Press, 1968, pp. 60-61.

(13) https://pages.uoregon.edu/dluebke/301ModernEurope/Sieyes3dEstate.pdf (14) Doyle, William. Oxford History of the French Revolution. Oxford University Press, 1989, pp. 104-105.

(15) French Revolution. “A Citizen Recalls the Taking of the Bastille (1789),” January 11, 2013. https://alphahistory.com/frenchrevolution/humbert-taking-of-the-bastille-1789/.

(16) Hampson, Norman. A Social History of the French Revolution. University of Toronto Press, 1968, pp. 74-75.

(17) Hazan, Eric. A People’s History of the French Revolution, Verso, 2014, pp. 36-37.

(18) Lefebvre, Georges. The French Revolution: From its origins to 1793. Routledge, 1957, pp. 121-122.

(19) Schama, Simon. Citizens: A Chronicle of the French Revolution. Random House, 1989, pp. 428-430.

(20) Hampson, Norman. A Social History of the French Revolution. University of Toronto Press, 1968, p. 80.

(21) Doyle, William. Oxford History of the French Revolution. Oxford University Press, 1989, pp. 116-117.

(22) Fitzsimmons, Michael “The Principles of 1789” in McPhee, Peter, editor. A Companion to the French Revolution. Blackwell, 2013, pp. 75-88.

(23) Hazan, Eric. A People’s History of the French Revolution, Verso, 2014, pp. 68-81.

(24) Hazan, Eric. A People’s History of the French Revolution, Verso, 2014, pp. 45-46.

(25) Schama, Simon. Citizens: A Chronicle of the French Revolution. Random House, 1989,.pp. 460-466.

(26) Schama, Simon. Citizens: A Chronicle of the French Revolution. Random House, 1989, pp. 524-525.

(27) Hazan, Eric. A People’s History of the French Revolution, Verso, 2014, pp. 47-48.

(28) Hazan, Eric. A People’s History of the French Revolution, Verso, 2014, pp. 51.

(29) Doyle, William. Oxford History of the French Revolution. Oxford University Press, 1989, pp. 128.

(30) Lewis, Gwynne. The French Revolution: Rethinking the Debate. Routledge, 2016, pp. 30 -31.

(31) Hazan, Eric. A People’s History of the French Revolution, Verso, 2014, pp.. 53 -62.

(32) Doyle, William. Oxford History of the French Revolution. Oxford University Press, 1989, pp. 129-130.

(33) Hazan, Eric. A People’s History of the French Revolution, Verso, 2014, pp. 62-63.

(34) Doyle, William. Oxford History of the French Revolution. Oxford University Press, 1989, pp. 156-157, 171-173.

(35) Hazan, Eric. A People’s History of the French Revolution, Verso, 2014, pp. 65-66.

(36) Schama, Simon. Citizens: A Chronicle of the French Revolution. Random House, 1989, pp. 543-544.

(37) Doyle, William. Oxford History of the French Revolution. Oxford University Press, 1989, pp. 179-180.

(38) Doyle, William. Oxford History of the French Revolution. Oxford University Press, 1989, pp. 184-185.

(39) Hampson, Norman. Social History of the French Revolution. Routledge, 1963, pp. 148-149.

(40) Doyle, William. Oxford History of the French Revolution. Oxford University Press, 1989, pp. 191-192.

(41) Lefebvre, Georges. The French Revolution: From Its Origins to 1793. Routledge, 1962, pp. 252-254.

(42) Hazan, Eric. A People’s History of the French Revolution, Verso, 2014, pp. 88-89.

(43) Schama, Simon. Citizens: a Chronicle of the French Revolution. Random House, 1990, pp. 576-79.

(44) Schama, Simon. Citizens: a Chronicle of the French Revolution. New York, Random House, 1990, pp. 649-51

(45) Doyle, William. Oxford History of the French Revolution. Oxford University Press, 1989, pp. 242-243.

(46) Connor, Clifford. Marat: The Tribune of the French Revolution. Pluto Press, 2012.

(47) Schama, Simon. Citizens: A Chronicle of the French Revolution. Random House, 1989, pp. 722-724.

(48) Doyle, William. Oxford History of the French Revolution. Oxford University Press, 1989, pp. 246-47.

(49) Hampson, Norman. A Social History of the French Revolution. University of Toronto Press, 1968, pp. 209-210.

(50) Hobsbawm, Eric. The Age of Revolution. Vintage Books, 1996, pp 68-70.

(51) Doyle, William. Oxford History of the French Revolution. Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1989, pp. 205-206

(52) Schama, Simon. Citizens: a Chronicle of the French Revolution. New York, Random House, 1990, 784-86.

(53) Doyle, William. Oxford History of the French Revolution. Oxford University Press, 1989, pp. 262.

(54) Schama, Simon. Citizens: a Chronicle of the French Revolution. New York, Random House, 1990, pp. 619-22.

(55) Doyle, William. Oxford History of the French Revolution. Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1989, pp. 269-70.

(56) Doyle, William. Oxford History of the French Revolution. Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1989, p. 276.

(57) Robespierre on Virtue and Terror (1794). https://alphahistory.com/frenchrevolution/robespierre-virtue-terror-1794/. Accessed 19 May 2020.

(58) Doyle, William. Oxford History of the French Revolution. Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1989, pp. 290-91.

(59) Doyle, William. Oxford History of the French Revolution. Oxford University Press, 1989, pp. 293-95.

(60) Lewis, Gwynne. The French Revolution: Rethinking the Debate. Routledge, 2016, pp. 49-51.

How to Cite this Article

There are three different ways you can cite this article.

1. To cite this article in an academic-style article or paper , use:

<a href=" https://historycooperative.org/the-french-revolution/ ">French Revolution: History, Timeline, Causes, and Outcomes</a>

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

French Revolution

By: History.com Editors

Updated: October 12, 2023 | Original: November 9, 2009

The French Revolution was a watershed event in world history that began in 1789 and ended in the late 1790s with the ascent of Napoleon Bonaparte. During this period, French citizens radically altered their political landscape, uprooting centuries-old institutions such as the monarchy and the feudal system. The upheaval was caused by disgust with the French aristocracy and the economic policies of King Louis XVI, who met his death by guillotine, as did his wife Marie Antoinette. Though it degenerated into a bloodbath during the Reign of Terror, the French Revolution helped to shape modern democracies by showing the power inherent in the will of the people.

Causes of the French Revolution

As the 18th century drew to a close, France’s costly involvement in the American Revolution , combined with extravagant spending by King Louis XVI , had left France on the brink of bankruptcy.

Not only were the royal coffers depleted, but several years of poor harvests, drought, cattle disease and skyrocketing bread prices had kindled unrest among peasants and the urban poor. Many expressed their desperation and resentment toward a regime that imposed heavy taxes—yet failed to provide any relief—by rioting, looting and striking.

In the fall of 1786, Louis XVI’s controller general, Charles Alexandre de Calonne, proposed a financial reform package that included a universal land tax from which the aristocratic classes would no longer be exempt.

Estates General

To garner support for these measures and forestall a growing aristocratic revolt, the king summoned the Estates General ( les états généraux ) – an assembly representing France’s clergy, nobility and middle class – for the first time since 1614.

The meeting was scheduled for May 5, 1789; in the meantime, delegates of the three estates from each locality would compile lists of grievances ( cahiers de doléances ) to present to the king.

Rise of the Third Estate

France’s population, of course, had changed considerably since 1614. The non-aristocratic, middle-class members of the Third Estate now represented 98 percent of the people but could still be outvoted by the other two bodies.

In the lead-up to the May 5 meeting, the Third Estate began to mobilize support for equal representation and the abolishment of the noble veto—in other words, they wanted voting by head and not by status.

While all of the orders shared a common desire for fiscal and judicial reform as well as a more representative form of government, the nobles in particular were loath to give up the privileges they had long enjoyed under the traditional system.

Tennis Court Oath

By the time the Estates General convened at Versailles , the highly public debate over its voting process had erupted into open hostility between the three orders, eclipsing the original purpose of the meeting and the authority of the man who had convened it — the king himself.

On June 17, with talks over procedure stalled, the Third Estate met alone and formally adopted the title of National Assembly; three days later, they met in a nearby indoor tennis court and took the so-called Tennis Court Oath (serment du jeu de paume), vowing not to disperse until constitutional reform had been achieved.

Within a week, most of the clerical deputies and 47 liberal nobles had joined them, and on June 27 Louis XVI grudgingly absorbed all three orders into the new National Assembly.

The Bastille

On June 12, as the National Assembly (known as the National Constituent Assembly during its work on a constitution) continued to meet at Versailles, fear and violence consumed the capital.

Though enthusiastic about the recent breakdown of royal power, Parisians grew panicked as rumors of an impending military coup began to circulate. A popular insurgency culminated on July 14 when rioters stormed the Bastille fortress in an attempt to secure gunpowder and weapons; many consider this event, now commemorated in France as a national holiday, as the start of the French Revolution.

The wave of revolutionary fervor and widespread hysteria quickly swept the entire country. Revolting against years of exploitation, peasants looted and burned the homes of tax collectors, landlords and the aristocratic elite.

Known as the Great Fear ( la Grande peur ), the agrarian insurrection hastened the growing exodus of nobles from France and inspired the National Constituent Assembly to abolish feudalism on August 4, 1789, signing what historian Georges Lefebvre later called the “death certificate of the old order.”

Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen

IIn late August, the Assembly adopted the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen ( Déclaration des droits de l ’homme et du citoyen ), a statement of democratic principles grounded in the philosophical and political ideas of Enlightenment thinkers like Jean-Jacques Rousseau .

The document proclaimed the Assembly’s commitment to replace the ancien régime with a system based on equal opportunity, freedom of speech, popular sovereignty and representative government.

Drafting a formal constitution proved much more of a challenge for the National Constituent Assembly, which had the added burden of functioning as a legislature during harsh economic times.

For months, its members wrestled with fundamental questions about the shape and expanse of France’s new political landscape. For instance, who would be responsible for electing delegates? Would the clergy owe allegiance to the Roman Catholic Church or the French government? Perhaps most importantly, how much authority would the king, his public image further weakened after a failed attempt to flee the country in June 1791, retain?

Adopted on September 3, 1791, France’s first written constitution echoed the more moderate voices in the Assembly, establishing a constitutional monarchy in which the king enjoyed royal veto power and the ability to appoint ministers. This compromise did not sit well with influential radicals like Maximilien de Robespierre , Camille Desmoulins and Georges Danton, who began drumming up popular support for a more republican form of government and for the trial of Louis XVI.

French Revolution Turns Radical

In April 1792, the newly elected Legislative Assembly declared war on Austria and Prussia, where it believed that French émigrés were building counterrevolutionary alliances; it also hoped to spread its revolutionary ideals across Europe through warfare.

On the domestic front, meanwhile, the political crisis took a radical turn when a group of insurgents led by the extremist Jacobins attacked the royal residence in Paris and arrested the king on August 10, 1792.

The following month, amid a wave of violence in which Parisian insurrectionists massacred hundreds of accused counterrevolutionaries, the Legislative Assembly was replaced by the National Convention, which proclaimed the abolition of the monarchy and the establishment of the French republic.

On January 21, 1793, it sent King Louis XVI, condemned to death for high treason and crimes against the state, to the guillotine ; his wife Marie-Antoinette suffered the same fate nine months later.

Reign of Terror

Following the king’s execution, war with various European powers and intense divisions within the National Convention brought the French Revolution to its most violent and turbulent phase.

In June 1793, the Jacobins seized control of the National Convention from the more moderate Girondins and instituted a series of radical measures, including the establishment of a new calendar and the eradication of Christianity .

They also unleashed the bloody Reign of Terror (la Terreur), a 10-month period in which suspected enemies of the revolution were guillotined by the thousands. Many of the killings were carried out under orders from Robespierre, who dominated the draconian Committee of Public Safety until his own execution on July 28, 1794.

Did you know? Over 17,000 people were officially tried and executed during the Reign of Terror, and an unknown number of others died in prison or without trial.

Thermidorian Reaction

The death of Robespierre marked the beginning of the Thermidorian Reaction, a moderate phase in which the French people revolted against the Reign of Terror’s excesses.

On August 22, 1795, the National Convention, composed largely of Girondins who had survived the Reign of Terror, approved a new constitution that created France’s first bicameral legislature.

Executive power would lie in the hands of a five-member Directory ( Directoire ) appointed by parliament. Royalists and Jacobins protested the new regime but were swiftly silenced by the army, now led by a young and successful general named Napoleon Bonaparte .

French Revolution Ends: Napoleon’s Rise

The Directory’s four years in power were riddled with financial crises, popular discontent, inefficiency and, above all, political corruption. By the late 1790s, the directors relied almost entirely on the military to maintain their authority and had ceded much of their power to the generals in the field.

On November 9, 1799, as frustration with their leadership reached a fever pitch, Napoleon Bonaparte staged a coup d’état, abolishing the Directory and appointing himself France’s “ first consul .” The event marked the end of the French Revolution and the beginning of the Napoleonic era, during which France would come to dominate much of continental Europe.

Photo Gallery

French Revolution. The National Archives (U.K.) The United States and the French Revolution, 1789–1799. Office of the Historian. U.S. Department of State . Versailles, from the French Revolution to the Interwar Period. Chateau de Versailles . French Revolution. Monticello.org . Individuals, institutions, and innovation in the debates of the French Revolution. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences .

HISTORY Vault

Stream thousands of hours of acclaimed series, probing documentaries and captivating specials commercial-free in HISTORY Vault

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

French Revolution Essay: Writing Topics and Examples

The French Revolution is one of the most significant historical events, undeniably impacting the world. It marked the end of the monarchy, sparked a quest for freedom, and transformed societies forever. Understanding this pivotal moment requires diving into its layers of politics, social change, and passionate beliefs. In this article, we’ll share proven tips on how to write a French Revolution paper and provide vivid examples. If you need urgent and practical help with this assignment, hire an essay writer online right now!

When Was the French Revolution?

The French Revolution occurred between 1789 and 1799, marking France's tumultuous decade of radical social and political change. Here's a brief French Revolution timeline of key events during this period:

- May 5: Estates-General convenes for the first time since 1614, marking the beginning of the revolutionary process.

- June 17: The National Assembly is formed by members of the Third Estate, signaling defiance against the absolute monarchy.

- July 14: The storming of the Bastille, a symbol of royal tyranny, ignites widespread revolt across France.

- July 14: The National Constituent Assembly adopts the Constitution of 1791, establishing a constitutional monarchy.

- April 20: France declares war on Austria, initiating the French Revolutionary Wars.

- August 10: The storming of the Tuileries Palace led to the monarchy's fall and the establishment of the First French Republic.

- September 20: The National Convention abolishes the monarchy and proclaims the First French Republic.

- September 22: French troops achieve victory at the Battle of Valmy, halting the advance of Austrian and Prussian forces.

- January 21: King Louis XVI is executed by guillotine.

- June 2: The Montagnards seize control of the National Convention, leading to the Reign of Terror.

- July 13: Assassination of Jean-Paul Marat, a prominent Jacobin leader.

- September 17: The Law of Suspects is passed, leading to mass arrests and executions.

- October 16: Queen Marie Antoinette is executed.

- July 28: Maximilien Robespierre, a key figure in the Reign of Terror, is executed, marking the end of the most intense phase of the revolution.

- August 22: The National Convention adopts the Constitution of the Year III, establishing the Directory as the new form of government.

- November 9–10: Napoleon Bonaparte stages a coup d'état, overthrowing the Directory and establishing the Consulate, effectively ending the revolution and leading to the rise of Napoleon as the ruler of France.

French Revolution Essay Topics

Here are 10 compelling topics you can use to produce an essay connected to the French Revolution:

- Causes of the French Revolution and its effects.

- The economic factors behind the French Revolution: Struggles of the Third Estate.

- How did the American Revolution influence the French Revolution?

- The role of Enlightenment ideas in sparking the French Revolution.

- When did the French Revolution start, and how?

- Women in the French Revolution: Voices of resistance and reform.

- Who is Napoleon, French Revolution key figure?

- The impact of the French Revolution on European monarchies: A catalyst for change or consolidation of power?

- Reign of Terror: French Revolution.

- How does the French Revolution continue to shape national identity today?

If you need more interesting topics or even a custom-tailored paper, simply say, ‘ write my essays ,’ and our experts will cater to all your wishes.

What Caused the French Revolution?

The French Revolution causes were propelled by a complex interplay of political, social, and economic factors that simmered for decades before erupting into open rebellion. At its core, the revolution was sparked by deep resentment towards the monarchy and the aristocracy, who held disproportionate power and privileges. At the same time, much of the population suffered from poverty and oppression.

The financial crisis exacerbated by the extravagant spending of King Louis XVI and the French participation in the American Revolutionary War further strained the economy, burdening the already impoverished masses with heavy taxation and economic hardship. Meanwhile, the Enlightenment ideals of liberty, equality, and fraternity had permeated French society, inspiring a growing sense of political consciousness and a desire for reform among the educated bourgeoisie and the disenfranchised lower classes. As discontent simmered and economic grievances worsened, the stage was set for a revolution that would forever alter the course of French and world history.

Moreover, the rigid social structure of the Ancien Régime, with its entrenched privileges and hierarchical divisions, exacerbated tensions within French society. The feudal system, characterized by feudal dues and obligations imposed on peasants, fueled resentment and discontent among the rural population, who bore the brunt of the economic burden.

Meanwhile, the bourgeoisie, comprising the educated middle class, chafed against their exclusion from political power and sought to assert their influence. The Estates-General, which represented the three estates of French society – the clergy, the nobility, and the commoners – highlighted the stark disparities in representation and exacerbated social divisions. As grievances mounted and calls for reform intensified, the failure of the traditional institutions to address the burgeoning crisis laid the groundwork for a revolutionary uprising that would ultimately sweep away the old order and herald the dawn of a new era in French history. Are you struggling with analyzing historical events in the form of short compositions? We suggest you say, ‘ write my history essay for me ,’ so our authors can help you swiftly.

How to Write an Essay About What Caused the French Revolution?

Here are some useful tips for writing an essay about the causes of the French Revolution:

.png)

- Thematic Organization

Instead of simply listing causes chronologically, consider organizing your essay thematically. Group relevant causes under overarching themes such as social inequality, economic hardship, and political discontent. This approach allows for a more nuanced analysis and clearer presentation of your arguments.

- Primary Source Analysis

Incorporate primary sources, such as letters, diaries, and speeches from the period, into your essay. Analyzing primary sources provides firsthand accounts and perspectives that can enrich your understanding of the causes of the French Revolution and add depth to your analysis.

- Historiographical Debate

Engage with historiographical debates surrounding the causes of the French Revolution. Explore differing interpretations among historians and evaluate the strengths and weaknesses of various arguments. This demonstrates a critical approach to the topic and adds complexity to your essay.

- Global Context

Situate the French Revolution within a broader global context. Consider how Enlightenment ideas, revolutionary movements in other countries, and global economic trends influenced events in France. This global perspective adds depth and relevance to your analysis.

- Comparative Analysis

Compare the causes of the French Revolution with other historical revolutions or periods of social upheaval. Drawing parallels and contrasts can shed light on common patterns and unique factors contributing to revolutionary change, enriching your analysis and providing a broader perspective.

- Historical Contingency

Emphasize the contingency of historical events by considering alternative outcomes and turning points. Explore how different decisions or circumstances could have altered the events leading up to the French Revolution. This fosters a deeper understanding of the complex interplay of factors involved.

- Interdisciplinary Insights

Draw on insights from other disciplines, such as sociology, economics, and political science, to enrich your analysis of the causes of the French Revolution. Consider how social structures, economic systems, and political institutions interacted to shape historical outcomes.

- Critical Reflection

Reflect critically on the relevance and implications of studying the causes of the French Revolution today. Consider how historical narratives are constructed and shape our understanding of contemporary issues such as inequality, democracy, and social change.

- Revision and Peer Review

Seek feedback from peers or instructors on your essay drafts. Revision and peer review can help you identify areas for improvement, clarify your arguments, and strengthen your overall essay.

- Ethical Considerations

Reflect on the ethical dimensions of studying historical events such as the French Revolution. Consider whose voices are represented in historical narratives and whose perspectives may be marginalized or overlooked. Aim for a balanced and inclusive approach that acknowledges diverse experiences and viewpoints.

What Impact Did the French Revolution Have on the Rest of Europe?

In an essay on the French Revolution, writing about its historical impact is one of the most popular pathways for students. The French Revolution reverberated across Europe, igniting revolutionary fervor and political upheaval in many countries. Its impact was profound and far-reaching, influencing the course of European history for decades. In the immediate aftermath of the revolution, neighboring monarchies grew increasingly alarmed by the spread of revolutionary ideals and the threat they posed to the established order. This led to military interventions to quell revolutionary movements and restore monarchic authority, such as the Napoleonic Wars and the Congress of Vienna. Additionally, the French Revolution inspired nationalist movements and calls for constitutional reform in European countries, fueling demands for greater political participation and individual rights.

Furthermore, the French Revolution challenged the legitimacy of traditional monarchical rule and paved the way for the rise of new political ideologies, such as liberalism and socialism. The revolutionary upheaval prompted rulers to enact reforms to appease restless populations and prevent further unrest. In some cases, these reforms led to the gradual transition towards constitutional monarchy or representative government, as rulers sought to balance the demands of their subjects with the need to maintain stability and control. However, the spread of revolutionary ideas also incited conservative backlash and repression as ruling elites sought to suppress dissent and preserve their grip on power.

Ultimately, the French Revolution reshaped the political landscape of Europe, accelerating the decline of absolute monarchy and feudalism while laying the groundwork for modern democratic principles and institutions. Its legacy is evident in the waves of political reform, social change, and nationalist sentiment that swept across the continent in the 19th and 20th centuries. Although the revolution initially faced resistance and backlash from entrenched conservative forces, its ideals of liberty, equality, and fraternity inspired movements for social justice and political reform throughout Europe and beyond. We also have an insightful guide on how to write an essay on the American Revolution , so be sure to consult it, too!

The End of French Revolution

One of the themes for your essay is when did the French Revolution end and what came next. The French Revolution is generally considered to have ended with the rise of Napoleon Bonaparte to power in 1799. This marked the beginning of the Napoleonic era, which saw the consolidation of power under Napoleon's rule and the establishment of the French Consulate. While the revolutionary fervor of the early years subsided, many of the revolutionary ideals and reforms introduced during the Revolution continued to shape French society and politics throughout the Napoleonic period and beyond.

Napoleon's ascent to power marked a significant turning point in French history, ending the tumultuous revolutionary political turmoil and social upheaval. Under Napoleon's leadership, France experienced a period of relative stability and centralization of power as he implemented a series of reforms to modernize the country and consolidate his authority. However, Napoleon's ambitious military campaigns and imperial expansion eventually led to his downfall, culminating in the defeat of the French Empire in 1815 and the restoration of the Bourbon monarchy. While the French Revolution formally ended with Napoleon's rise to power, its legacy endured, shaping subsequent developments in France and influencing movements for social and political change worldwide. If you’re interested in other pivotal historical moments, read more about the Battle of Hastings 1066 .

The French Revolution Aftermath

The aftermath of the French Revolution was characterized by a complex interplay of political, social, and economic repercussions reverberating throughout France and beyond. While the revolution achieved significant political change, including abolishing the monarchy and establishing a republic, it also unleashed a period of internal conflict, violence, and instability known as the Reign of Terror.

The revolution's radicalism and upheaval led to the widespread destruction of traditional institutions and social norms, leaving a legacy of deep division and mistrust within French society. Additionally, the revolutionary wars sparked by France's expansionist ambitions resulted in widespread devastation and loss of life across Europe. Despite these challenges, the French Revolution also laid the groundwork for modern concepts of democracy, human rights, and citizenship, leaving an indelible mark on Western history. Before we get down to the most important facts about the French Revolution, use our political science essay writing service without hesitation if your deadlines are too short.

What Everyone Should Know About the French Revolution?

Here are 10 captivating French Revolution facts you should know:

- On July 14, 1789, angry Parisians stormed the Bastille, a symbol of royal tyranny and oppression, sparking the French Revolution.

- During the Reign of Terror (1793-1794), led by Maximilien Robespierre, thousands of perceived enemies of the revolution were executed, including King Louis XVI and Queen Marie Antoinette.

- The guillotine became synonymous with the French Revolution's brutality, providing a swift and "humane" method of execution for thousands, including high-profile figures like Robespierre himself.

- Robespierre attempted to create a new state religion, the Cult of the Supreme Being, to replace Catholicism but failed to gain widespread acceptance.

- In October 1789, thousands of women from Paris marched to Versailles to demand bread and protest against the high cost of living, forcing King Louis XVI to return to Paris.

- In June 1789, members of the National Assembly took a pivotal oath on a tennis court, vowing not to disband until a new constitution was established, signaling the end of absolute monarchy in France.

- Adopted in August 1789, the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen proclaimed the rights of all citizens, including liberty, equality, and fraternity, influencing future declarations of human rights worldwide.

- Passed in 1790, the Civil Constitution of the Clergy law aimed to subordinate the Catholic Church to the state, sparking conflict with the Pope and dividing French society along religious lines.

- In July 1794, Robespierre was overthrown in a coup known as the Thermidorian Reaction, leading to the end of the Reign of Terror and a period of political moderation in France.

- Despite its turbulent end, the French Revolution had a profound and lasting impact, inspiring subsequent revolutions, shaping modern concepts of democracy and human rights, and influencing political ideologies worldwide.

Examples of a French Revolution Essay

Writing a French Revolution essay may be difficult from a technical perspective due to the abundance of themes related to this event. However, with the French Revolution essay example in front of you, writer’s block will easily vanish, giving way to creativity and genuine interest in the topic.

The Role of Women in the French Revolution: Challenges to Gender Norms and Struggles for Equality

This essay explores the integral yet often overlooked role of women in the French Revolution, focusing on their defiance of traditional gender norms and their relentless pursuit of equality. Despite being confined to the domestic sphere before the revolution, women emerged as active participants in political activism, forming societies, participating in protests, and contributing to revolutionary discourse. While facing resistance from male-dominated institutions, women such as Pauline Léon, Claire Lacombe, and Olympe de Gouges challenged societal expectations, advocated for political rights, and demanded recognition of their inherent equality.

Economic Turmoil and Social Unrest: Exploring the Impact of Financial Crisis on Revolutionary France

This essay examines the profound interconnection between economic turmoil and social unrest in Revolutionary France, elucidating how financial crises, exacerbated by fiscal mismanagement and regressive taxation, ignited widespread discontent among the populace and catalyzed the collapse of the ancien régime. The economic hardships endured by rural peasants and urban workers alike fueled a climate of social upheaval, manifesting in uprisings, pamphleteering, and demands for political and social reform. The French Revolution of 1789, characterized by the storming of the Bastille and the subsequent establishment of the National Assembly, emerged as a response to the injustices of the existing social order, albeit fraught with political strife and violence. Ultimately, the essay underscores the pivotal role of economic instability in precipitating revolutionary change and shaping the trajectory of modern history.

Legacy of Terror: Assessing the Reign of Terror's Influence on Revolutionary Ideals and Political Discourse

This essay analyzes the enduring legacy of the Reign of Terror during the French Revolution, examining its profound impact on revolutionary ideals and political discourse. It explores how the terror, initially conceived to safeguard the revolution, ultimately devolved into a brutal campaign of violence and repression, betraying the very principles it purported to defend. The essay assesses the ramifications of the terror on revolutionary ideals, highlighting the skepticism it engendered towards violent means of achieving social change and the challenges it posed to the balance between liberty and security. Furthermore, it examines the terror's influence on political discourse, shaping responses to subsequent revolutions and revolutions globally, and underscores the importance of confronting its complexities to navigate contemporary challenges and safeguard democratic principles.

In conclusion, contributing to an essay on the French Revolution necessitates a comprehensive understanding of this transformative period's historical context, key events, and ideological underpinnings.

By employing a structured approach that includes thorough research, critical analysis, and clear argumentation, scholars and students can effectively navigate the complexities of this multifaceted topic.

Emphasizing the significance of economic, social, and political factors while acknowledging the diverse perspectives and interpretations surrounding the revolution enables writers to craft nuanced and insightful essays that contribute to our understanding of this pivotal historical moment.

Frequently asked questions

She was flawless! first time using a website like this, I've ordered article review and i totally adored it! grammar punctuation, content - everything was on point

This writer is my go to, because whenever I need someone who I can trust my task to - I hire Joy. She wrote almost every paper for me for the last 2 years

Term paper done up to a highest standard, no revisions, perfect communication. 10s across the board!!!!!!!

I send him instructions and that's it. my paper was done 10 hours later, no stupid questions, he nailed it.

Sometimes I wonder if Michael is secretly a professor because he literally knows everything. HE DID SO WELL THAT MY PROF SHOWED MY PAPER AS AN EXAMPLE. unbelievable, many thanks

You Might Also Like

New Posts to Your Inbox!

Stay in touch

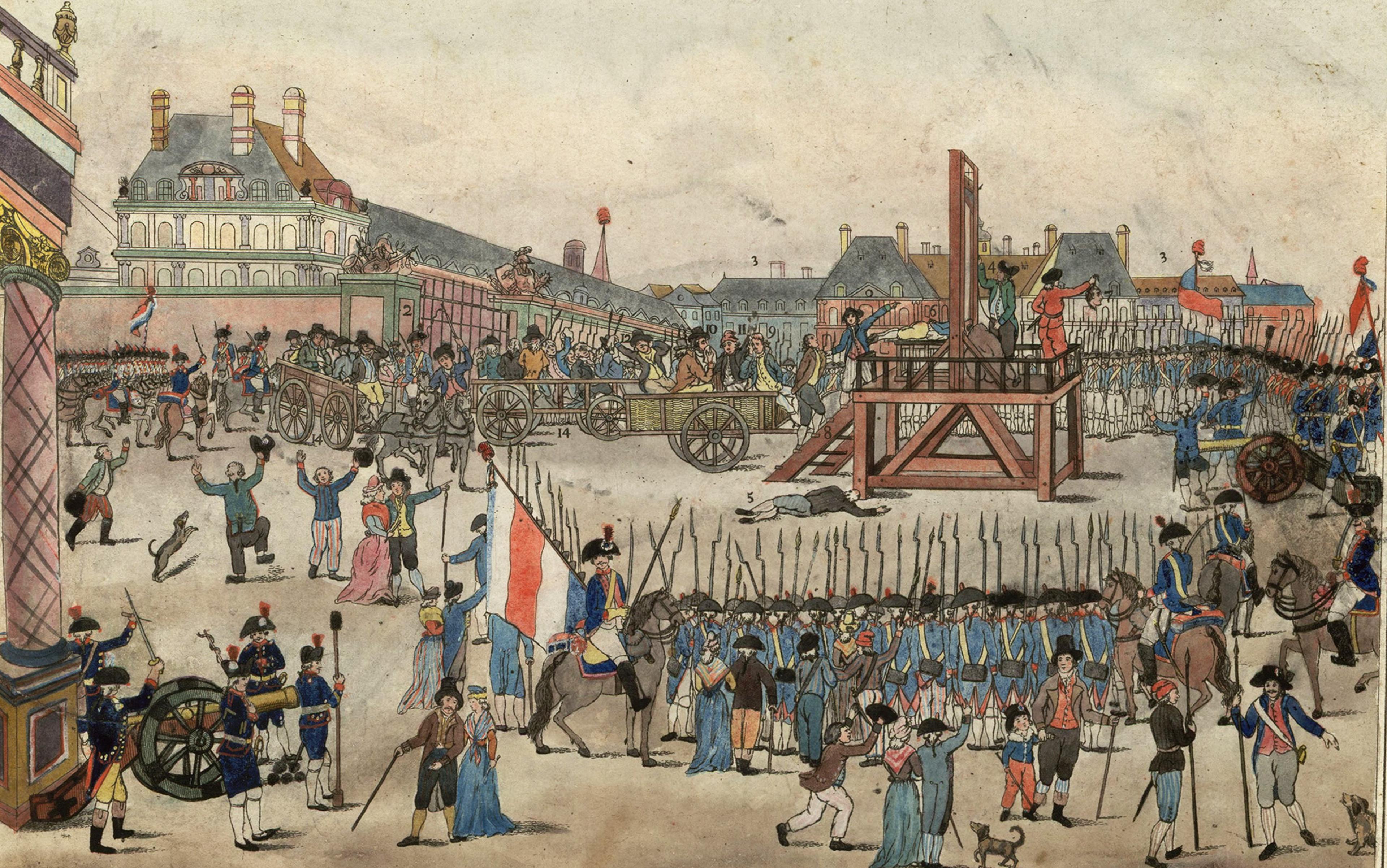

The execution of Robespierre and his accomplices, 17 July 1794 (10 Thermidor Year II). Robespierre is depicted holding a handkerchief and dressed in a brown jacket in the cart immediately to the left of the scaffold. Photo courtesy the Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Paris

Vive la révolution!

Must radical political change generate uncontainable violence the french revolution is both a cautionary and inspiring tale.

by Jeremy Popkin + BIO

If the French Revolution of 1789 was such an important event, visitors to France’s capital city of Paris often wonder, why can’t they find any trace of the Bastille, the medieval fortress whose storming on 14 July 1789 was the revolution’s most dramatic moment? Determined to destroy what they saw as a symbol of tyranny, the ‘victors of the Bastille’ immediately began demolishing the structure. Even the column in the middle of the busy Place de la Bastille isn’t connected to 1789: it commemorates those who died in another uprising a generation later, the ‘July Revolution’ of 1830.

The legacy of the French Revolution is not found in physical monuments, but in the ideals of liberty, equality and justice that still inspire modern democracies. More ambitious than the American revolutionaries of 1776, the French in 1789 were not just fighting for their own national independence: they wanted to establish principles that would lay the basis for freedom for human beings everywhere. The United States Declaration of Independence briefly mentioned rights to ‘liberty, equality, and the pursuit of happiness’, without explaining what they meant or how they were to be realised. The French ‘Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen’ spelled out the rights that comprised liberty and equality and outlined a system of participatory government that would empower citizens to protect their own rights.

Much more openly than the Americans, the French revolutionaries recognised that the principles of liberty and equality they had articulated posed fundamental questions about such issues as the status of women and the justification of slavery. In France, unlike the US, these questions were debated heatedly and openly. Initially, the revolutionaries decided that ‘nature’ denied women political rights and that ‘imperious necessity’ dictated the maintenance of slavery in France’s overseas colonies, whose 800,000 enslaved labourers outnumbered the 670,000 in the 13 American states in 1789.

As the revolution proceeded, however, its legislators took more radical steps. A law redefining marriage and legalising divorce in 1792 granted women equal rights to sue for separation and child custody; by that time, women had formed their own political clubs, some were openly serving in the French army, and Olympe de Gouges’s eloquent ‘Declaration of the Rights of Woman’ had insisted that they should be allowed to vote and hold office. Women achieved so much influence in the streets of revolutionary Paris that they drove male legislators to try to outlaw their activities. At almost the same time, in 1794, faced with a massive uprising among the enslaved blacks in France’s most valuable Caribbean colony, Saint-Domingue, the French National Convention abolished slavery and made its former victims full citizens. Black men were seated as deputies to the French legislature and, by 1796, the black general Toussaint Louverture was the official commander-in-chief of French forces in Saint-Domingue, which would become the independent nation of Haiti in 1804.

The French Revolution’s initiatives concerning women’s rights and slavery are just two examples of how the French revolutionaries experimented with radical new ideas about the meaning of liberty and equality that are still relevant. But the French Revolution is not just important today because it took such radical steps to broaden the definitions of liberty and equality. The movement that began in 1789 also showed the dangers inherent in trying to remake an entire society overnight. The French revolutionaries were the first to grant the right to vote to all adult men, but they were also the first to grapple with democracy’s shadow side, demagogic populism, and with the effects of an explosion of ‘new media’ that transformed political communication. The revolution saw the first full-scale attempt to impose secular ideas in the face of vocal opposition from citizens who proclaimed themselves defenders of religion. In 1792, revolutionary France became the first democracy to launch a war to spread its values. A major consequence of that war was the creation of the first modern totalitarian dictatorship, the rule of the Committee of Public Safety during the Reign of Terror. Five years after the end of the Terror, Napoleon Bonaparte, who had gained fame as a result of the war, led the first modern coup d’état , justifying it, like so many strongmen since, by claiming that only an authoritarian regime could guarantee social order.

The fact that Napoleon reversed the revolutionaries’ expansion of women’s rights and reintroduced slavery in the French colonies reminds us that he, like so many of his imitators in the past two centuries, defined ‘social order’ as a rejection of any expansive definition of liberty and equality. Napoleon also abolished meaningful elections, ended freedom of the press, and restored the public status of the Catholic Church. Determined to keep and even expand the revolutionaries’ foreign conquests, he continued the war that they had begun, but French armies now fought to create an empire, dropping any pretence of bringing freedom to other peoples.

T he relevance of the French Revolution to present-day debates is the reason why I decided to write A New World Begins: The History of the French Revolution (2020), the first comprehensive English-language account of that event for general readers in more than 30 years. Having spent my career researching and teaching the history of the French Revolution, however, I know very well that it was more than an idealistic crusade for human rights. If the fall of the Bastille remains an indelible symbol of aspirations for freedom, the other universally recognised symbol of the French Revolution, the guillotine, reminds us that the movement was also marked by violence. The American Founding Fathers whose refusal to consider granting rights to women or ending slavery we now rightly question did have the good sense not to let their differences turn into murderous feuds; none of them had to reflect, as the French legislator Pierre Vergniaud did on the eve of his execution, that their movement, ‘like Saturn, is devouring its own children’.