- Link to facebook

- Link to linkedin

- Link to twitter

- Link to youtube

- Knowledge Hub

How to Choose the Right Type of Grant Proposal + Tips

- 13-minute read

- 26th April 2024

Grant proposals play a crucial role for businesses by securing funding for various projects and initiatives and serving as a roadmap for potential funders to understand the purpose and impact of a project they’re being asked to support. Understanding each type of proposal is essential to maximize your chances of successfully securing grant money for your endeavors.

In this guide, we’ll explore the different types of grant proposals – research, project, and operating – and provide insights into navigating them effectively . Let’s dive into the world of grant writing and learn how to craft a compelling proposal that will stand out to potential funders.

1. Research Grants

Research grants are financial awards provided to researchers, scholars, and institutions to support the investigation of specific topics or projects. These grants play a critical role in advancing knowledge and innovation across various fields such as science, technology, social sciences, and humanities. They enable researchers to conduct experiments, collect data, and disseminate their findings.

Research grants can help you pay for equipment purchases, hire research assistants, take care of travel expenses for fieldwork or conferences, and cover publication fees. Grant writing varies among academic disciplines, but there are several criteria and tips to keep in mind to heighten your chances of securing funding.

Criteria for Qualifying for a Research Grant

Securing research grants is highly competitive. They’re usually awarded based on the quality of the proposed research project , the researcher’s track record, and the potential impact of the study. When applying for a research grant, meeting specific criteria is essential to increase your chances of qualifying for funding. Here are some common criteria for researchers to be eligible for a research grant:

- Research proposal: A well-defined and compelling research proposal outlining the expected outcomes, methodology , and potential impact of the study is crucial.

- Relevance: The proposed project should align with the funding organization’s or grant provider’s priorities and focus areas. Be sure to research your prospective funder thoroughly.

- Qualifications: Researchers often must demonstrate their expertise in the field through academic qualifications , publications, and relevant experience.

- Budget: A clear and realistic budget plan detailing how the grant funds will be utilized is usually necessary.

- Ethical considerations: Researchers must adhere to ethical standards when conducting their research, including obtaining necessary approvals for studies involving human subjects or sensitive data.

- 6. Timeline: Research grant applications will likely require a detailed timeline outlining key milestones and deliverables throughout the research project.

Tips for Writing a Compelling Research Grant Proposal

1. clearly define your research objectives.

Start by clearly outlining the objectives of your research project . Clearly state the problem you’re addressing, the significance of the work, and the expected outcomes.

2. Provide a Detailed Methodology

Describe in detail the methodology you’ll use to conduct your research. Explain why this approach is suitable and how it will help you achieve your research objectives.

3. Demonstrate Feasibility

Show that your research project is feasible by providing a realistic timeline, budget, and the resources required to complete the study successfully.

4. Highlight Your Qualifications

Emphasize your qualifications and experience in the field to demonstrate that you’re capable of carrying out the proposed research.

Common Mistakes to Avoid in Research Grant Proposals

When it comes to preparing research grant proposals, there are several common mistakes that you should watch out for to increase your chances of success.

One of the most common mistakes in research grant proposals is providing an inadequate literature review . Failure to demonstrate a thorough understanding of the existing research on your topic can weaken your proposal’s credibility and impact.

Another critical mistake is ignoring or failing to adhere to the specific guidelines the granting agency provides. Carefully read and follow these guidelines to ensure your proposal is compliant and competitive.

Finally, overlooking proofreading and editing can significantly diminish the quality of a research grant proposal. Typos, grammatical errors, or inconsistencies can detract from the overall professionalism of the document.

2. Project Grants

Project grants are a valuable source of funding for initiatives in various fields, such as education, training, demonstration, and technical assistance. These grants are typically used to support specific projects that aim to achieve certain objectives or outcomes within a designated timeframe.

A benefit of project grants is that they can provide financial support for activities that may not be feasible through regular funding sources.

Entry Criteria for Project Grants

When applying for project grants, it’s essential to clearly outline the goals, methodology, budget requirements, and expected outcomes of the proposed project. These components play a significant role in demonstrating the feasibility and impact of the project to potential funders.

- Goals: Define the overarching goals of your project along with specific objectives that outline what you aim to achieve through the proposed activities . What problem does the project solve? Make sure your goals are realistic, measurable, and in line with the funding organization’s mission.

- Methodology: Describe in detail how you plan to execute the project, including the strategies, activities, and timeline. Provide information on any research methods or tools you’ll use to measure your progress toward your goals.

- Budget: Create a detailed research budget that outlines all the anticipated costs associated with implementing your project. Include expenses such as employee salaries, equipment purchases, travel costs, supplies, and any other relevant expenditures.

- Expected outcomes: Articulate what you expect to accomplish by the end of the project period. Underscore the significance of your research project by explaining how these outcomes will help you address the problem that your project is focused on and how they align with your goals and those of potential funders.

By incorporating these criteria into your project grant proposal, you can effectively communicate your vision for the project while demonstrating its feasibility and potential impact on achieving its desired goals.

Key Considerations of a Successful Project Grant Proposal

1. highlight the potential impact and sustainability of your project.

Grant-making organizations are often interested in supporting sustainable projects that have a lasting effect beyond the funding period. Clearly outline how your project will create positive change and continue to thrive after the grant ends, as this can make your proposal more compelling.

2. Demonstrate Strong Partnerships

Demonstrating strong partnerships and collaborations can enhance the credibility of your proposal. Showcase any existing partnerships or plans for collaboration with other organizations or stakeholders to indicate to funders that your project has a solid foundation for success.

3. Tell a Compelling Story

Use storytelling techniques to engage the reader and make them care about your project. Highlight personal anecdotes, case studies, or statistics that demonstrate the impact of your work.

Common Mistakes to Avoid in Project Grant Proposals

There are several potential mistakes to be aware of when writing project grant proposals. One of the most common is failing to clearly articulate the project’s goals , objects, and expected outcomes. Be concise yet detailed in explaining what your project aims to achieve.

Another common mistake is not following a funder’s guidelines . With project grants, each grant proposal will come with specific guidelines and requirements set by the funding organization. Ignoring or deviating from these guidelines can lead to immediate disqualification.

Finally, failing to proofread and edit can reflect poorly on your professionalism and attention to detail. Always proofread and edit your proposal before submission.

3. Operating Grants

Operating grants provide funding for organizations to cover essential expenses, such as rent, utilities, salaries, building maintenance, and day-to-day operational costs. These types of grants provide financial support to ensure the smooth functioning of an organization’s daily expenditures so that it can focus on its mission.

Eligibility Requirements for Operating Grants

Unique eligibility requirements are often in place for operating grants to ensure the funding is allocated to organizations that have a genuine need for financial support. Common eligibility requirements include:

- Nonprofit status: Many operating grants are exclusively available to nonprofit organizations. Applicants must provide proof of their nonprofit status through registration documents or tax-exempt certification.

- Mission alignment: Grant providers often look for organizations with missions that align with the goals and values of the funding source. It’s essential to demonstrate how your organization’s activities and objectives align with those of the grant provider.

- Financial stability: Grantmakers may assess an organization’s financial stability and sustainability before awarding an operating grant. This process could involve submitting financial statements, budgets, and other relevant financial documents.

- Impact assessment: Organizations may be required to demonstrate their impact on the community or target population they serve. Grant applications often ask for information on past achievements, outcomes, and evaluation methods.

- Regulation compliance: Operating grants typically have specific regulations and reporting requirements that grantees must adhere to. Organizations must ensure that they can comply with these regulations before applying for funding.

By understanding and meeting these eligibility requirements, organizations can increase their chances of securing operating grants to support their mission-driven work effectively.

Strategies for Crafting a Successful Operating Grant Proposal

Crafting a successful operating grant proposal requires careful planning and execution. Here are some key strategies to help you increase your chances of securing funding for your organization:

1. Budget Wisely

Develop a detailed budget that aligns with the proposed activities and outcomes outlined in your operating grant proposal. Ensure that all expenses are clearly justified and realistic.

2. Engage Stakeholders

Involve key stakeholders , such as board members, staff, volunteers, or beneficiaries in the grant writing process. Their insights and perspectives can enrich the narrative of your proposal.

3. Review and Revise

Take the time to review and revise your grant proposal multiple times before submission. Check for errors, clarity of language, consistency in formatting, and adherence to guidelines.

Common Mistakes to Avoid in Operating Grant Proposals

Creating a successful operating grant proposal requires careful planning and execution. A common mistake seen with operating grant proposals is a lack of clarity in the objectives and goals of the organization to justify the need for the grant. Be specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound ( SMART ) when defining objectives.

Another misstep is weak budget justification . A strong budget justification is essential to demonstrate that the requested funds will be used effectively. Avoid vague or unrealistic budget allocations and ensure that each expense is clearly justified and aligns with the project’s goals.

Finally, omitting an evaluation plan from your proposal can be detrimental, as it shows a lack of foresight in measuring the impact and success of the project. Including a robust evaluation plan demonstrates accountability and commitment to achieving results.

Which Grant Is Right for my Business?

When considering a grant for your business, study up on the different types to determine which one aligns best with your goals. Here’s a quick recap:

Research grants:

- Research grants are typically awarded to support scientific or academic research projects.

- They’re designed to fund investigations that contribute new knowledge or address specific research questions.

- These grants often require detailed proposals outlining the research methodology, objectives, and expected outcomes.

Project grants:

- Project grants focus on supporting specific initiatives or projects within an organization.

- They can be used for activities such as community programs, educational initiatives, or capacity-building projects.

- Project grants may require a clear outline of how the funds will be utilized and the expected impact on the target audience.

Operating grants:

- Operating grants provide funding to support the overall operations and sustainability of a nonprofit organization or business.

- They can cover expenses such as salaries, overhead costs, program development, and capacity-building efforts.

- Applicants for operating grants may need to demonstrate their organizational structure, financial stability, and long-term goals.

To sum up, research grants focus on advancing knowledge, project grants support specific initiatives, and operating grants sustain overall operations.

Factors to Consider When Choosing the Right Grant Type for Your Organization

When deciding on the most suitable grant type for your organization, several factors come into play to ensure a successful application process:

- Purpose and goals: Consider the primary purpose of your organization and its current goals. Research grants are typically geared toward funding specific research projects, while project grants support initiatives that align with a particular cause. Operating grants provide general operating support for overall sustainability.

- Scope of work: Evaluate the scope of work involved in your project or program. Research grants focus on conducting studies or experiments to advance activities to achieve desired outcomes, while project grants emphasize implementing specific activities to achieve desired outcomes. Operating grants support the day-to-day operations and infrastructure of an organization.

- Budget and funding needs: Assess the budget requirements and funding needs for your proposed project or organizational activities. Research grants often provide funding for equipment, personnel, and research-related expenses. Project grants cover costs associated with implementing programs or services, while operating grants help cover operational expenses such as rent, utilities, salaries, and overhead costs.

Grant Writing Tips for Success

Despite the differences between the grant proposal types we’ve discussed, there are overlaps in the eligibility criteria and recommended strategies for success. Here are some general tips to enhance the effectiveness of your grant proposals:

- Clearly define your project goals and objectives: Clearly outline what you aim to achieve with your grant funding. Provide a detailed description of the project, including its purpose, target audience , and expected outcomes.

- Tailor your proposal to the funder: Research the funder’s priorities , guidelines, and requirements before drafting your proposal. Customize your proposal to align with their mission and objectives for a better chance of success.

- Use clear and concise language: Avoid jargon or technical terms that may be difficult for non-experts to understand. Use simple language to clearly communicate your ideas and make a strong case for why your project deserves funding.

- Highlight the impact of your project: Clearly demonstrate how your project will make a difference to the community or the field it serves. Provide evidence of past successes or outcomes that support the effectiveness of your proposed activities.

- Include a realistic budget: Present a detailed budget that accurately reflects the costs associated with implementing your project. Ensure that all expenses are justified and reasonable based on industry standards.

- Proofreading and editing: One of the most crucial steps in creating a successful grant application is thorough proofreading and editing . Before submitting your grant proposal, review it multiple times to catch any grammatical errors, typos, and inconsistencies. Remember, a polished and error-free proposal demonstrates professionalism and attention to detail, which can significantly impact its success in securing funding.

In this post, we navigated the differences between the main types of grant proposals, discussed how to choose the right type for your organization, and shared some strategies on how to increase the likelihood of each type’s success. We also went over some general tips to enhance the effectiveness of all three types of grant proposals, including clearly defining the project goals, tailoring the proposal to the funder, using clear and concise language, highlighting the impact of the project, including a realistic budget, and proofreading and editing your grant proposal documents thoroughly.

If you’d like help with editing or proofreading your grant proposal, Proofed for Business is here for you. Learn more about how our team of experts can proofread, edit, and polish your professional content by scheduling a call with us today !

Jump to Section

Share this article:, want to save time on your content editing, our expert proofreaders have you covered., learn more about proofreading & editing.

- Top Content Marketing Platforms for Editorial Teams (2024)

- The Role of AI in Multilingual Content Editing and Localization

- How to Outsource Your Copy Editing for Content Growth and Scalability

- Five Signs It’s Time to Invest in Professional Proofreading

- The Dos and Don'ts of Proofreading for Legal Documents

- Data Storytelling: What It Is and How to Ace It

- The Benefits of Fact-Checking Your Content

- Your Guide to Efficient Enterprise Copy Editing

- Copyediting Versus Line Editing: What’s the Difference?

- How to Edit Grant Applications – and Increase Your Chance of Success

- How to Copyedit Anything Step by Step

- What Is Developmental Editing?

- Copy Editing vs. Proofreading: What's the Difference?

- What Is Copy Editing?

- Top Tips for Training Editors on Your Team

- How Proofed Slashed Delivery Times for IoT Analytics

Looking For The Perfect Partner?

Let’s talk about the support you need.

Book a call with a Proofed expert today

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- CAREER FEATURE

- 20 December 2019

Secrets to writing a winning grant

- Emily Sohn 0

Emily Sohn is a freelance journalist in Minneapolis, Minnesota.

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

When Kylie Ball begins a grant-writing workshop, she often alludes to the funding successes and failures that she has experienced in her career. “I say, ‘I’ve attracted more than $25 million in grant funding and have had more than 60 competitive grants funded. But I’ve also had probably twice as many rejected.’ A lot of early-career researchers often find those rejections really tough to take. But I actually think you learn so much from the rejected grants.”

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$29.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

$199.00 per year

only $3.90 per issue

Rent or buy this article

Prices vary by article type

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Nature 577 , 133-135 (2020)

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-019-03914-5

Related Articles

- Communication

How to network with the brightest minds in science

Career Feature 26 JUN 24

What it means to be a successful male academic

Career Column 26 JUN 24

Is science’s dominant funding model broken?

Editorial 26 JUN 24

How I’m using AI tools to help universities maximize research impacts

World View 26 JUN 24

We can make the UK a science superpower — with a radical political manifesto

World View 18 JUN 24

Securing your science: the researcher’s guide to financial management

Career Feature 14 JUN 24

How researchers and their managers can build an actionable career-development plan

Career Column 17 JUN 24

‘Rainbow’, ‘like a cricket’: every bird in South Africa now has an isiZulu name

News 06 JUN 24

PostDoc Researcher, Magnetic Recording Materials Group, National Institute for Materials Science

Starting date would be after January 2025, but it is negotiable.

National Institute for Materials Science

Tenure-Track/Tenured Faculty Positions

Tenure-Track/Tenured Faculty Positions in the fields of energy and resources.

Suzhou, Jiangsu, China

School of Sustainable Energy and Resources at Nanjing University

Postdoctoral Associate- Statistical Genetics

Houston, Texas (US)

Baylor College of Medicine (BCM)

Senior Research Associate (Single Cell/Transcriptomics Senior Bioinformatician)

Metabolic Research Laboratories at the Clinical School, University of Cambridge are recruiting 3 senior bioinformatician specialists to create a dynam

Cambridge, Cambridgeshire (GB)

University of Cambridge

Cancer Biology Postdoctoral Fellow

Tampa, Florida

Moffitt Cancer Center

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Educational resources and simple solutions for your research journey

How to Write a Successful Research Grant Proposal: An Overview

Writing a research grant proposal can be a challenging task, especially for those who are new to the process. However, a well-written proposal can increase the chances of receiving the necessary funding for your research.

This guide discusses the key criteria to consider when writing a grant proposal and what to include in each section.

Table of Contents

Key criteria to consider

When writing a grant proposal, there are five main criteria that you need to consider. These are:

- Significance

- Innovation

- Investigators

- Environment

The funding body will look for these criteria throughout your statement, so it’s important to tailor what you say and how you say it accordingly.

1. Significance

Significance refers to the value of the research you are proposing. It should address an important research problem and be significant in your field or for society. Think about what you are hoping to find and how it could be valuable in the industry or area you are working in. What does success look like? What could follow-on work lead to?

2. Approach

Approach refers to the methods and techniques you plan to use. The funding body will be looking at how well-developed and integrated your framework, design, methods, and analysis are. They will also want to know if you have considered any problem areas and alternative approaches. Experimental design, data collection and processing, and ethical considerations all fall under this group.

3. Innovation

Innovation means that you are proposing something new and original. Your aims should be original and innovative, or your proposed methods and approaches should be new and novel . Ideally both would be true. Your project should also challenge existing paradigms or develop new methodologies or technologies.

4. Investigators

Investigators here refer to you and your team, or proposed team. The funding body will want to know if you are well-trained and have the right qualifications and experience to conduct the research . This is important as it shows you have the ability to undertake the research successfully. One part of this evaluation will be, have you been awarded grants in the past. This is one reason to start early in your career with grant applications to smaller funds to build up a track record.

5. Environment

Environment refers to the scientific environment in which the work will be done. The funding body will want to know if the scientific environment will contribute to the overall probability of success. This could include your institution, the building or lab you will be working in, and any collaborative arrangements you have in place. Any similar research work conducted in your institution in the past will show that your environment is likely to be appropriate.

Writing the grant proposal

It’s almost impossible to generalize across funders, since each has its own highly specific format for applications, but most applications have the following sections in common.

1. Abstract

The abstract is a summary of your research proposal. It should be around 150 to 200 words and summarize your aims, the gap in literature, the methods you plan to use, and how long you might take.

2. Literature Review

The literature review is a review of the literature related to your field. It should summarize the research within your field, speaking about the top research papers and review papers. You should mention any existing knowledge about your topic and any preliminary data you have. If you have any hypotheses, you can add them at the end of the literature review.

The aims section needs to be very clear about what your aims are for the project. You should have a couple of aims if you are looking for funding for two or three years. State your aims clearly using strong action words.

4. Significance

In this section, you should sell the significance of your research. Explain why your research is important and why you deserve the funding.

Defining Your Research Questions

It’s essential to identify the research questions you want to answer when writing a grant proposal. It’s also crucial to determine the potential impact of your research and narrow your focus.

1.Innovation and Originality

Innovation is critical in demonstrating that your research is original and has a unique approach compared to existing research. In this section, it’s essential to highlight the importance of the problem you’re addressing, any critical barriers to progress in the field, and how your project will improve scientific knowledge and technical capabilities. You should also demonstrate whether your methods, technologies, and approach are unique.

2. Research approach and methodology

Your research approach and methodology are crucial components of your grant proposal. In the approach section, you should outline your research methodology, starting with an overview that summarizes your aims and hypotheses. You should also introduce your research team and justify their involvement in the project, highlighting their academic background and experience. Additionally, you should describe their roles within the team. It’s also important to include a timeline that breaks down your research plan into different stages, each with specific goals.

In the methodology section, detail your research methods, anticipated results, and limitations. Be sure to consider the potential limitations that could occur and provide solutions to overcome them. Remember, never give a limitation without providing a solution.

Common reasons for grant failure

Knowing the common reasons why grant proposals fail can help you avoid making these mistakes. The five key reasons for grant failure are:

- Poor science – The quality of the research is not high enough.

- Poor organization – The proposal is not organized in a clear way.

- Poor integration – The proposal lacks clear integration between different sections.

- Contradiction – The proposal contradicts itself.

- Lack of qualifications or experienc e – The researcher lacks the necessary qualifications or experience to conduct the research.

By avoiding these pitfalls, you will increase your chances of receiving the funding you need to carry out your research successfully.

Tips for writing a strong grant proposal

Writing a successful grant proposal requires careful planning and execution. Here are some tips to help you create a strong grant proposal:

- Begin writing your proposal early. Grant proposals take time and effort to write. Start as early as possible to give yourself enough time to refine your ideas and address any issues that arise.

- Read the guidelines carefully . Make sure to read the guidelines thoroughly before you start writing. This will help you understand the requirements and expectations of the funding agency.

- Use clear, concise language . Avoid using technical jargon and complex language. Write in a way that is easy to understand and conveys your ideas clearly. It’s important to note that grant reviewers are not likely to be domain experts in your field.

- Show, don’t tell . Use specific examples and evidence to support your claims. This will help to make your grant proposal more convincing.

- Get feedback . Ask colleagues, mentors, or other experts to review your proposal and provide feedback. This will help you identify any weaknesses or areas for improvement.

Conclusion

Writing a successful grant proposal is an important skill for any researcher. By following the key criteria and tips outlined in this guide, you can increase your chances of securing funding for your research. Remember to be clear, concise, and innovative in your writing, and to address any potential weaknesses in your proposal. With a well-written grant proposal, you can make your research goals a reality.

If you are looking for help with your grant application, come talk to us at GrantDesk. We have grant experts who are ready to help you get the research funding you need.

Related Posts

What is a Case Study in Research? Definition, Methods, and Examples

Take Top AI Tools for Researchers for a Spin with the Editage All Access 7-Day Pass!

Grant Proposals (or Give me the money!)

What this handout is about.

This handout will help you write and revise grant proposals for research funding in all academic disciplines (sciences, social sciences, humanities, and the arts). It’s targeted primarily to graduate students and faculty, although it will also be helpful to undergraduate students who are seeking funding for research (e.g. for a senior thesis).

The grant writing process

A grant proposal or application is a document or set of documents that is submitted to an organization with the explicit intent of securing funding for a research project. Grant writing varies widely across the disciplines, and research intended for epistemological purposes (philosophy or the arts) rests on very different assumptions than research intended for practical applications (medicine or social policy research). Nonetheless, this handout attempts to provide a general introduction to grant writing across the disciplines.

Before you begin writing your proposal, you need to know what kind of research you will be doing and why. You may have a topic or experiment in mind, but taking the time to define what your ultimate purpose is can be essential to convincing others to fund that project. Although some scholars in the humanities and arts may not have thought about their projects in terms of research design, hypotheses, research questions, or results, reviewers and funding agencies expect you to frame your project in these terms. You may also find that thinking about your project in these terms reveals new aspects of it to you.

Writing successful grant applications is a long process that begins with an idea. Although many people think of grant writing as a linear process (from idea to proposal to award), it is a circular process. Many people start by defining their research question or questions. What knowledge or information will be gained as a direct result of your project? Why is undertaking your research important in a broader sense? You will need to explicitly communicate this purpose to the committee reviewing your application. This is easier when you know what you plan to achieve before you begin the writing process.

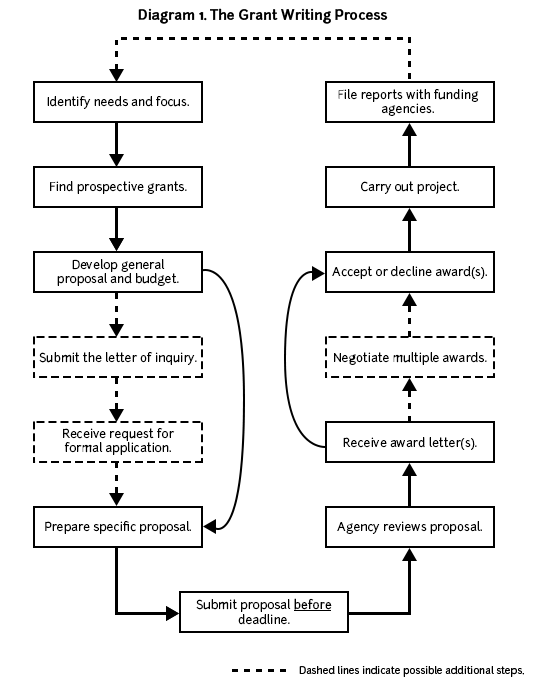

Diagram 1 below provides an overview of the grant writing process and may help you plan your proposal development.

Applicants must write grant proposals, submit them, receive notice of acceptance or rejection, and then revise their proposals. Unsuccessful grant applicants must revise and resubmit their proposals during the next funding cycle. Successful grant applications and the resulting research lead to ideas for further research and new grant proposals.

Cultivating an ongoing, positive relationship with funding agencies may lead to additional grants down the road. Thus, make sure you file progress reports and final reports in a timely and professional manner. Although some successful grant applicants may fear that funding agencies will reject future proposals because they’ve already received “enough” funding, the truth is that money follows money. Individuals or projects awarded grants in the past are more competitive and thus more likely to receive funding in the future.

Some general tips

- Begin early.

- Apply early and often.

- Don’t forget to include a cover letter with your application.

- Answer all questions. (Pre-empt all unstated questions.)

- If rejected, revise your proposal and apply again.

- Give them what they want. Follow the application guidelines exactly.

- Be explicit and specific.

- Be realistic in designing the project.

- Make explicit the connections between your research questions and objectives, your objectives and methods, your methods and results, and your results and dissemination plan.

- Follow the application guidelines exactly. (We have repeated this tip because it is very, very important.)

Before you start writing

Identify your needs and focus.

First, identify your needs. Answering the following questions may help you:

- Are you undertaking preliminary or pilot research in order to develop a full-blown research agenda?

- Are you seeking funding for dissertation research? Pre-dissertation research? Postdoctoral research? Archival research? Experimental research? Fieldwork?

- Are you seeking a stipend so that you can write a dissertation or book? Polish a manuscript?

- Do you want a fellowship in residence at an institution that will offer some programmatic support or other resources to enhance your project?

- Do you want funding for a large research project that will last for several years and involve multiple staff members?

Next, think about the focus of your research/project. Answering the following questions may help you narrow it down:

- What is the topic? Why is this topic important?

- What are the research questions that you’re trying to answer? What relevance do your research questions have?

- What are your hypotheses?

- What are your research methods?

- Why is your research/project important? What is its significance?

- Do you plan on using quantitative methods? Qualitative methods? Both?

- Will you be undertaking experimental research? Clinical research?

Once you have identified your needs and focus, you can begin looking for prospective grants and funding agencies.

Finding prospective grants and funding agencies

Whether your proposal receives funding will rely in large part on whether your purpose and goals closely match the priorities of granting agencies. Locating possible grantors is a time consuming task, but in the long run it will yield the greatest benefits. Even if you have the most appealing research proposal in the world, if you don’t send it to the right institutions, then you’re unlikely to receive funding.

There are many sources of information about granting agencies and grant programs. Most universities and many schools within universities have Offices of Research, whose primary purpose is to support faculty and students in grant-seeking endeavors. These offices usually have libraries or resource centers to help people find prospective grants.

At UNC, the Research at Carolina office coordinates research support.

The Funding Information Portal offers a collection of databases and proposal development guidance.

The UNC School of Medicine and School of Public Health each have their own Office of Research.

Writing your proposal

The majority of grant programs recruit academic reviewers with knowledge of the disciplines and/or program areas of the grant. Thus, when writing your grant proposals, assume that you are addressing a colleague who is knowledgeable in the general area, but who does not necessarily know the details about your research questions.

Remember that most readers are lazy and will not respond well to a poorly organized, poorly written, or confusing proposal. Be sure to give readers what they want. Follow all the guidelines for the particular grant you are applying for. This may require you to reframe your project in a different light or language. Reframing your project to fit a specific grant’s requirements is a legitimate and necessary part of the process unless it will fundamentally change your project’s goals or outcomes.

Final decisions about which proposals are funded often come down to whether the proposal convinces the reviewer that the research project is well planned and feasible and whether the investigators are well qualified to execute it. Throughout the proposal, be as explicit as possible. Predict the questions that the reviewer may have and answer them. Przeworski and Salomon (1995) note that reviewers read with three questions in mind:

- What are we going to learn as a result of the proposed project that we do not know now? (goals, aims, and outcomes)

- Why is it worth knowing? (significance)

- How will we know that the conclusions are valid? (criteria for success) (2)

Be sure to answer these questions in your proposal. Keep in mind that reviewers may not read every word of your proposal. Your reviewer may only read the abstract, the sections on research design and methodology, the vitae, and the budget. Make these sections as clear and straightforward as possible.

The way you write your grant will tell the reviewers a lot about you (Reif-Lehrer 82). From reading your proposal, the reviewers will form an idea of who you are as a scholar, a researcher, and a person. They will decide whether you are creative, logical, analytical, up-to-date in the relevant literature of the field, and, most importantly, capable of executing the proposed project. Allow your discipline and its conventions to determine the general style of your writing, but allow your own voice and personality to come through. Be sure to clarify your project’s theoretical orientation.

Develop a general proposal and budget

Because most proposal writers seek funding from several different agencies or granting programs, it is a good idea to begin by developing a general grant proposal and budget. This general proposal is sometimes called a “white paper.” Your general proposal should explain your project to a general academic audience. Before you submit proposals to different grant programs, you will tailor a specific proposal to their guidelines and priorities.

Organizing your proposal

Although each funding agency will have its own (usually very specific) requirements, there are several elements of a proposal that are fairly standard, and they often come in the following order:

- Introduction (statement of the problem, purpose of research or goals, and significance of research)

Literature review

- Project narrative (methods, procedures, objectives, outcomes or deliverables, evaluation, and dissemination)

- Budget and budget justification

Format the proposal so that it is easy to read. Use headings to break the proposal up into sections. If it is long, include a table of contents with page numbers.

The title page usually includes a brief yet explicit title for the research project, the names of the principal investigator(s), the institutional affiliation of the applicants (the department and university), name and address of the granting agency, project dates, amount of funding requested, and signatures of university personnel authorizing the proposal (when necessary). Most funding agencies have specific requirements for the title page; make sure to follow them.

The abstract provides readers with their first impression of your project. To remind themselves of your proposal, readers may glance at your abstract when making their final recommendations, so it may also serve as their last impression of your project. The abstract should explain the key elements of your research project in the future tense. Most abstracts state: (1) the general purpose, (2) specific goals, (3) research design, (4) methods, and (5) significance (contribution and rationale). Be as explicit as possible in your abstract. Use statements such as, “The objective of this study is to …”

Introduction

The introduction should cover the key elements of your proposal, including a statement of the problem, the purpose of research, research goals or objectives, and significance of the research. The statement of problem should provide a background and rationale for the project and establish the need and relevance of the research. How is your project different from previous research on the same topic? Will you be using new methodologies or covering new theoretical territory? The research goals or objectives should identify the anticipated outcomes of the research and should match up to the needs identified in the statement of problem. List only the principle goal(s) or objective(s) of your research and save sub-objectives for the project narrative.

Many proposals require a literature review. Reviewers want to know whether you’ve done the necessary preliminary research to undertake your project. Literature reviews should be selective and critical, not exhaustive. Reviewers want to see your evaluation of pertinent works. For more information, see our handout on literature reviews .

Project narrative

The project narrative provides the meat of your proposal and may require several subsections. The project narrative should supply all the details of the project, including a detailed statement of problem, research objectives or goals, hypotheses, methods, procedures, outcomes or deliverables, and evaluation and dissemination of the research.

For the project narrative, pre-empt and/or answer all of the reviewers’ questions. Don’t leave them wondering about anything. For example, if you propose to conduct unstructured interviews with open-ended questions, be sure you’ve explained why this methodology is best suited to the specific research questions in your proposal. Or, if you’re using item response theory rather than classical test theory to verify the validity of your survey instrument, explain the advantages of this innovative methodology. Or, if you need to travel to Valdez, Alaska to access historical archives at the Valdez Museum, make it clear what documents you hope to find and why they are relevant to your historical novel on the ’98ers in the Alaskan Gold Rush.

Clearly and explicitly state the connections between your research objectives, research questions, hypotheses, methodologies, and outcomes. As the requirements for a strong project narrative vary widely by discipline, consult a discipline-specific guide to grant writing for some additional advice.

Explain staffing requirements in detail and make sure that staffing makes sense. Be very explicit about the skill sets of the personnel already in place (you will probably include their Curriculum Vitae as part of the proposal). Explain the necessary skill sets and functions of personnel you will recruit. To minimize expenses, phase out personnel who are not relevant to later phases of a project.

The budget spells out project costs and usually consists of a spreadsheet or table with the budget detailed as line items and a budget narrative (also known as a budget justification) that explains the various expenses. Even when proposal guidelines do not specifically mention a narrative, be sure to include a one or two page explanation of the budget. To see a sample budget, turn to Example #1 at the end of this handout.

Consider including an exhaustive budget for your project, even if it exceeds the normal grant size of a particular funding organization. Simply make it clear that you are seeking additional funding from other sources. This technique will make it easier for you to combine awards down the road should you have the good fortune of receiving multiple grants.

Make sure that all budget items meet the funding agency’s requirements. For example, all U.S. government agencies have strict requirements for airline travel. Be sure the cost of the airline travel in your budget meets their requirements. If a line item falls outside an agency’s requirements (e.g. some organizations will not cover equipment purchases or other capital expenses), explain in the budget justification that other grant sources will pay for the item.

Many universities require that indirect costs (overhead) be added to grants that they administer. Check with the appropriate offices to find out what the standard (or required) rates are for overhead. Pass a draft budget by the university officer in charge of grant administration for assistance with indirect costs and costs not directly associated with research (e.g. facilities use charges).

Furthermore, make sure you factor in the estimated taxes applicable for your case. Depending on the categories of expenses and your particular circumstances (whether you are a foreign national, for example), estimated tax rates may differ. You can consult respective departmental staff or university services, as well as professional tax assistants. For information on taxes on scholarships and fellowships, see https://cashier.unc.edu/student-tax-information/scholarships-fellowships/ .

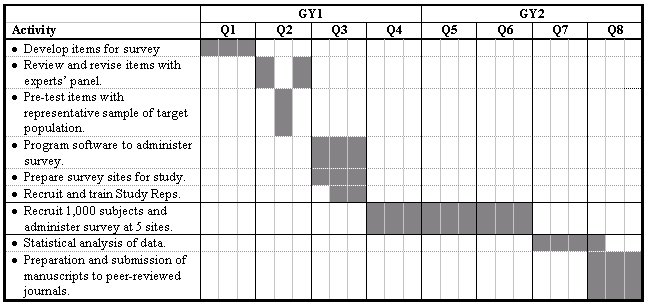

Explain the timeframe for the research project in some detail. When will you begin and complete each step? It may be helpful to reviewers if you present a visual version of your timeline. For less complicated research, a table summarizing the timeline for the project will help reviewers understand and evaluate the planning and feasibility. See Example #2 at the end of this handout.

For multi-year research proposals with numerous procedures and a large staff, a time line diagram can help clarify the feasibility and planning of the study. See Example #3 at the end of this handout.

Revising your proposal

Strong grant proposals take a long time to develop. Start the process early and leave time to get feedback from several readers on different drafts. Seek out a variety of readers, both specialists in your research area and non-specialist colleagues. You may also want to request assistance from knowledgeable readers on specific areas of your proposal. For example, you may want to schedule a meeting with a statistician to help revise your methodology section. Don’t hesitate to seek out specialized assistance from the relevant research offices on your campus. At UNC, the Odum Institute provides a variety of services to graduate students and faculty in the social sciences.

In your revision and editing, ask your readers to give careful consideration to whether you’ve made explicit the connections between your research objectives and methodology. Here are some example questions:

- Have you presented a compelling case?

- Have you made your hypotheses explicit?

- Does your project seem feasible? Is it overly ambitious? Does it have other weaknesses?

- Have you stated the means that grantors can use to evaluate the success of your project after you’ve executed it?

If a granting agency lists particular criteria used for rating and evaluating proposals, be sure to share these with your own reviewers.

Example #1. Sample Budget

| Jet Travel | ||||

| RDU-Kigali (roundtrip) | 1 | $6,100 | $6,100 | |

| Maintenance Allowance | ||||

| Rwanda | 12 months | $1,899 | $22,788 | $22,788 |

| Project Allowance | ||||

| Research Assistant/Translator | 12 months | $400 | $4800 | |

| Transportation within country | ||||

| –Phase 1 | 4 months | $300 | $1,200 | |

| –Phase 2 | 8 months | $1,500 | $12,000 | |

| 12 months | $60 | $720 | ||

| Audio cassette tapes | 200 | $2 | $400 | |

| Photographic and slide film | 20 | $5 | $100 | |

| Laptop Computer | 1 | $2,895 | ||

| NUD*IST 4.0 Software | $373 | |||

| Etc. | ||||

| Total Project Allowance | $35,238 | |||

| Administrative Fee | $100 | |||

| Total | $65,690 | |||

| Sought from other sources | ($15,000) | |||

| Total Grant Request | $50,690 |

Jet travel $6,100 This estimate is based on the commercial high season rate for jet economy travel on Sabena Belgian Airlines. No U.S. carriers fly to Kigali, Rwanda. Sabena has student fare tickets available which will be significantly less expensive (approximately $2,000).

Maintenance allowance $22,788 Based on the Fulbright-Hays Maintenance Allowances published in the grant application guide.

Research assistant/translator $4,800 The research assistant/translator will be a native (and primary) speaker of Kinya-rwanda with at least a four-year university degree. They will accompany the primary investigator during life history interviews to provide assistance in comprehension. In addition, they will provide commentary, explanations, and observations to facilitate the primary investigator’s participant observation. During the first phase of the project in Kigali, the research assistant will work forty hours a week and occasional overtime as needed. During phases two and three in rural Rwanda, the assistant will stay with the investigator overnight in the field when necessary. The salary of $400 per month is based on the average pay rate for individuals with similar qualifications working for international NGO’s in Rwanda.

Transportation within country, phase one $1,200 The primary investigator and research assistant will need regular transportation within Kigali by bus and taxi. The average taxi fare in Kigali is $6-8 and bus fare is $.15. This figure is based on an average of $10 per day in transportation costs during the first project phase.

Transportation within country, phases two and three $12,000 Project personnel will also require regular transportation between rural field sites. If it is not possible to remain overnight, daily trips will be necessary. The average rental rate for a 4×4 vehicle in Rwanda is $130 per day. This estimate is based on an average of $50 per day in transportation costs for the second and third project phases. These costs could be reduced if an arrangement could be made with either a government ministry or international aid agency for transportation assistance.

Email $720 The rate for email service from RwandaTel (the only service provider in Rwanda) is $60 per month. Email access is vital for receiving news reports on Rwanda and the region as well as for staying in contact with dissertation committee members and advisors in the United States.

Audiocassette tapes $400 Audiocassette tapes will be necessary for recording life history interviews, musical performances, community events, story telling, and other pertinent data.

Photographic & slide film $100 Photographic and slide film will be necessary to document visual data such as landscape, environment, marriages, funerals, community events, etc.

Laptop computer $2,895 A laptop computer will be necessary for recording observations, thoughts, and analysis during research project. Price listed is a special offer to UNC students through the Carolina Computing Initiative.

NUD*IST 4.0 software $373.00 NUD*IST, “Nonnumerical, Unstructured Data, Indexing, Searching, and Theorizing,” is necessary for cataloging, indexing, and managing field notes both during and following the field research phase. The program will assist in cataloging themes that emerge during the life history interviews.

Administrative fee $100 Fee set by Fulbright-Hays for the sponsoring institution.

Example #2: Project Timeline in Table Format

| Exploratory Research | Completed |

| Proposal Development | Completed |

| Ph.D. qualifying exams | Completed |

| Research Proposal Defense | Completed |

| Fieldwork in Rwanda | Oct. 1999-Dec. 2000 |

| Data Analysis and Transcription | Jan. 2001-March 2001 |

| Writing of Draft Chapters | March 2001 – Sept. 2001 |

| Revision | Oct. 2001-Feb. 2002 |

| Dissertation Defense | April 2002 |

| Final Approval and Completion | May 2002 |

Example #3: Project Timeline in Chart Format

Some closing advice

Some of us may feel ashamed or embarrassed about asking for money or promoting ourselves. Often, these feelings have more to do with our own insecurities than with problems in the tone or style of our writing. If you’re having trouble because of these types of hang-ups, the most important thing to keep in mind is that it never hurts to ask. If you never ask for the money, they’ll never give you the money. Besides, the worst thing they can do is say no.

UNC resources for proposal writing

Research at Carolina http://research.unc.edu

The Odum Institute for Research in the Social Sciences https://odum.unc.edu/

UNC Medical School Office of Research https://www.med.unc.edu/oor

UNC School of Public Health Office of Research http://www.sph.unc.edu/research/

Works consulted

We consulted these works while writing this handout. This is not a comprehensive list of resources on the handout’s topic, and we encourage you to do your own research to find additional publications. Please do not use this list as a model for the format of your own reference list, as it may not match the citation style you are using. For guidance on formatting citations, please see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial . We revise these tips periodically and welcome feedback.

Holloway, Brian R. 2003. Proposal Writing Across the Disciplines. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Prentice Hall.

Levine, S. Joseph. “Guide for Writing a Funding Proposal.” http://www.learnerassociates.net/proposal/ .

Locke, Lawrence F., Waneen Wyrick Spirduso, and Stephen J. Silverman. 2014. Proposals That Work . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Przeworski, Adam, and Frank Salomon. 2012. “Some Candid Suggestions on the Art of Writing Proposals.” Social Science Research Council. https://s3.amazonaws.com/ssrc-cdn2/art-of-writing-proposals-dsd-e-56b50ef814f12.pdf .

Reif-Lehrer, Liane. 1989. Writing a Successful Grant Application . Boston: Jones and Bartlett Publishers.

Wiggins, Beverly. 2002. “Funding and Proposal Writing for Social Science Faculty and Graduate Student Research.” Chapel Hill: Howard W. Odum Institute for Research in Social Science. 2 Feb. 2004. http://www2.irss.unc.edu/irss/shortcourses/wigginshandouts/granthandout.pdf.

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

Reference management. Clean and simple.

How to write a grant proposal: a step-by-step guide

What is a grant proposal?

Why should you write a grant proposal, format of a grant proposal, how to write a grant proposal, step 1: decide what funding opportunity to apply for, and research the grant application process, step 2: plan and research your project, preliminary research for your grant proposal, questions to ask yourself as you plan your grant proposal, developing your grant proposal, step 3: write the first draft of your grant proposal, step 4: get feedback, and revise your grant proposal accordingly, step 5: prepare to submit your grant proposal, what happens after submitting the grant proposal, final thoughts, other useful sources for writing grant proposals, frequently asked questions about writing grant proposals, related articles.

You have a vision for a future research project, and want to share that idea with the world.

To achieve your vision, you need funding from a sponsoring organization, and consequently, you need to write a grant proposal.

Although visualizing your future research through grant writing is exciting, it can also feel daunting. How do you start writing a grant proposal? How do you increase your chances of success in winning a grant?

But, writing a proposal is not as hard as you think. That’s because the grant-writing process can be broken down into actionable steps.

This guide provides a step-by-step approach to grant-writing that includes researching the application process, planning your research project, and writing the proposal. It is written from extensive research into grant-writing, and our experiences of writing proposals as graduate students, postdocs, and faculty in the sciences.

A grant proposal is a document or collection of documents that outlines the strategy for a future research project and is submitted to a sponsoring organization with the specific goal of getting funding to support the research. For example, grants for large projects with multiple researchers may be used to purchase lab equipment, provide stipends for graduate and undergraduate researchers, fund conference travel, and support the salaries of research personnel.

As a graduate student, you might apply for a PhD scholarship, or postdoctoral fellowship, and may need to write a proposal as part of your application. As a faculty member of a university, you may need to provide evidence of having submitted grant applications to obtain a permanent position or promotion.

Reasons for writing a grant proposal include:

- To obtain financial support for graduate or postdoctoral studies;

- To travel to a field site, or to travel to meet with collaborators;

- To conduct preliminary research for a larger project;

- To obtain a visiting position at another institution;

- To support undergraduate student research as a faculty member;

- To obtain funding for a large collaborative project, which may be needed to retain employment at a university.

The experience of writing a proposal can be helpful, even if you fail to obtain funding. Benefits include:

- Improvement of your research and writing skills

- Enhancement of academic employment prospects, as fellowships and grants awarded and applied for can be listed on your academic CV

- Raising your profile as an independent academic researcher because writing proposals can help you become known to leaders in your field.

All sponsoring agencies have specific requirements for the format of a grant proposal. For example, for a PhD scholarship or postdoctoral fellowship, you may be required to include a description of your project, an academic CV, and letters of support from mentors or collaborators.

For a large research project with many collaborators, the collection of documents that need to be submitted may be extensive. Examples of documents that might be required include a cover letter, a project summary, a detailed description of the proposed research, a budget, a document justifying the budget, and the CVs of all research personnel.

Before writing your proposal, be sure to note the list of required documents.

Writing a grant proposal can be broken down into three major activities: researching the project (reading background materials, note-taking, preliminary work, etc.), writing the proposal (creating an outline, writing the first draft, revisions, formatting), and administrative tasks for the project (emails, phone calls, meetings, writing CVs and other supporting documents, etc.).

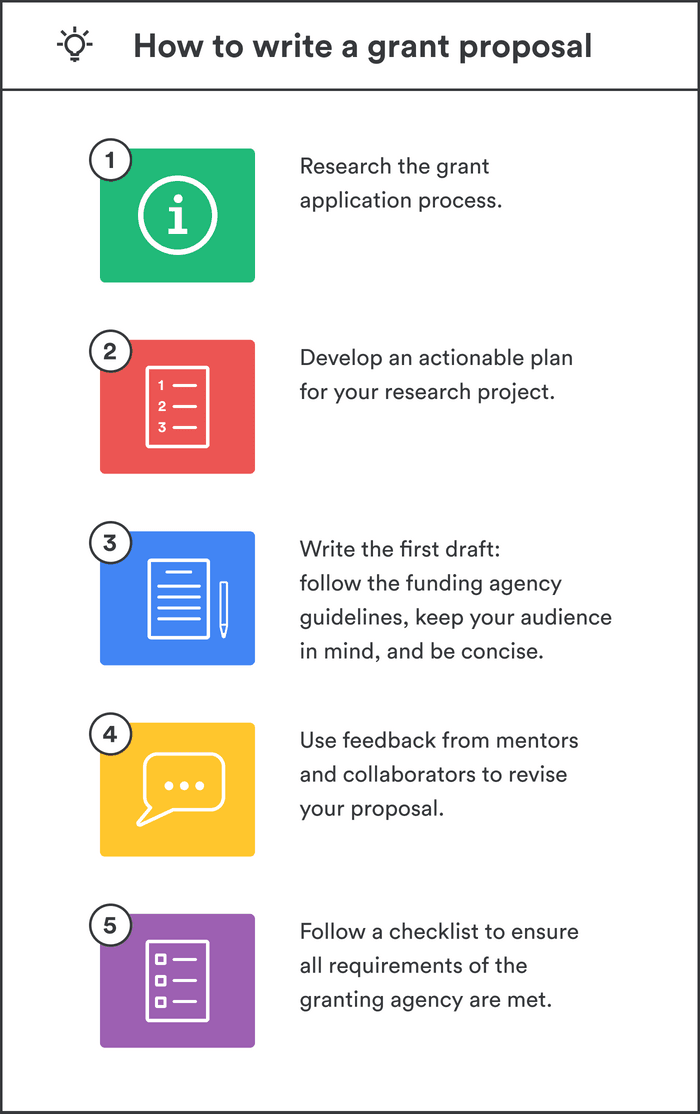

Below, we provide a step-by-step guide to writing a grant proposal:

- Decide what funding opportunity to apply for, and research the grant application process

- Plan and research your project

- Write the first draft of your grant proposal

- Get feedback, and revise your grant proposal accordingly

- Prepare to submit your grant proposal

- Start early. Begin by searching for funding opportunities and determining requirements. Some sponsoring organizations prioritize fundamental research, whereas others support applied research. Be sure your project fits the mission statement of the granting organization. Look at recently funded proposals and/or sample proposals on the agency website, if available. The Research or Grants Office at your institution may be able to help with finding grant opportunities.

- Make a spreadsheet of grant opportunities, with a link to the call for proposals page, the mission and aims of the agency, and the deadline for submission. Use the information that you have compiled in your spreadsheet to decide what to apply for.

- Once you have made your decision, carefully read the instructions in the call for proposals. Make a list of all the documents you need to apply, and note the formatting requirements and page limits. Know exactly what the funding agency requires of submitted proposals.

- Reach out to support staff at your university (for example, at your Research or Grants Office), potential mentors, or collaborators. For example, internal deadlines for submitting external grants are often earlier than the submission date. Make sure to learn about your institution’s internal processes, and obtain contact information for the relevant support staff.

- Applying for a grant or fellowship involves administrative work. Start preparing your CV and begin collecting supporting documents from collaborators, such as letters of support. If the application to the sponsoring agency is electronic, schedule time to set up an account, log into the system, download necessary forms and paperwork, etc. Don’t leave all of the administrative tasks until the end.

- Map out the important deadlines on your calendar. These might include video calls with collaborators, a date for the first draft to be complete, internal submission deadlines, and the funding agency deadline.

- Schedule time on your calendar for research, writing, and administrative tasks associated with the project. It’s wise to group similar tasks and block out time for them (a process known as ” time batching ”). Break down bigger tasks into smaller ones.

Now that you know what you are applying for, you can think about matching your proposed research to the aims of the agency. The work you propose needs to be innovative, specific, realizable, timely, and worthy of the sponsoring organization’s attention.

- Develop an awareness of the important problems and open questions in your field. Attend conferences and seminar talks and follow all of your field’s major journals.

- Read widely and deeply. Journal review articles are a helpful place to start. Reading papers from related but different subfields can generate ideas. Taking detailed notes as you read will help you recall the important findings and connect disparate concepts.

- Writing a grant proposal is a creative and imaginative endeavor. Write down all of your ideas. Freewriting is a practice where you write down all that comes to mind without filtering your ideas for feasibility or stopping to edit mistakes. By continuously writing your thoughts without judgment, the practice can help overcome procrastination and writer’s block. It can also unleash your creativity, and generate new ideas and associations. Mind mapping is another technique for brainstorming and generating connections between ideas.

- Establish a regular writing practice. Schedule time just for writing, and turn off all distractions during your focused work time. You can use your writing process to refine your thoughts and ideas.

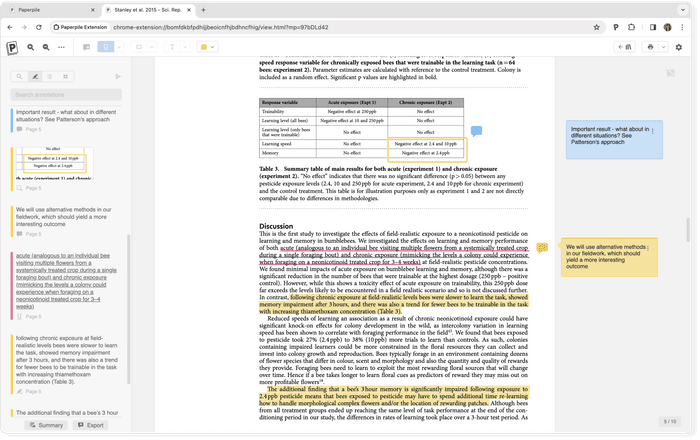

- Use a reference manager to build a library of sources for your project. You can use a reference management tool to collect papers , store and organize references , and highlight and annotate PDFs . Establish a system for organizing your ideas by tagging papers with labels and using folders to store similar references.

To facilitate intelligent thinking and shape the overall direction of your project, try answering the following questions:

- What are the questions that the project will address? Am I excited and curious about their answers?

- Why are these questions important?

- What are the goals of the project? Are they SMART (Specific, Measurable, Actionable, Relevant, and Timely)?

- What is novel about my project? What is the gap in current knowledge?

- What methods will I use, and how feasible is my approach?

- Can the work be done over the proposed period, and with the budget I am requesting?

- Do I have relevant experience? For example, have I completed similar work funded by previous grants or written papers on my proposed topic?

- What pilot research or prior work can I use, or do I need to complete preliminary research before writing the proposal?

- Will the outcomes of my work be consequential? Will the granting agency be interested in the results?

- What solutions to open problems in my field will this project offer? Are there broader implications of my work?

- Who will the project involve? Do I need mentors, collaborators, or students to contribute to the proposed work? If so, what roles will they have?

- Who will read the proposal? For example, experts in the field will require details of methods, statistical analyses, etc., whereas non-experts may be more concerned with the big picture.

- What do I want the reviewers to feel, and take away from reading my proposal?

- What weaknesses does my proposed research have? What objections might reviewers raise, and how can I address them?

- Can I visualize a timeline for my project?

Create an actionable plan for your research project using the answers to these questions.

- Now is the time to collect preliminary data, conduct experiments, or do a preliminary study to motivate your research, and demonstrate that your proposed project is realistic.

- Use your plan to write a detailed outline of the proposal. An outline helps you to write a proposal that has a logical format and ensures your thought process is rational. It also provides a structure to support your writing.

- Follow the granting agency’s guidelines for titles, sections, and subsections to inform your outline.

At this stage, you should have identified the aims of your project, what questions your work will answer, and how they are relevant to the sponsoring agency’s call for proposals. Be able to explain the originality, importance, and achievability of your proposed work.

Now that you have done your research, you are ready to begin writing your proposal and start filling in the details of your outline. Build on the writing routine you have already started. Here are some tips:

- Follow the guidelines of the funding organization.

- Keep the proposal reviewers in mind as you write. Your audience may be a combination of specialists in your field and non-specialists. Make sure to address the novelty of your work, its significance, and its feasibility.

- Write clearly, concisely, and avoid repetition. Use topic sentences for each paragraph to emphasize key ideas. Concluding sentences of each paragraph should develop, clarify, or summarize the support for the declaration in the topic sentence. To make your writing engaging, vary sentence length.

- Avoid jargon, where possible. Follow sentences that have complex technical information with a summary in plain language.

- Don’t review all information on the topic, but include enough background information to convince reviewers that you are knowledgeable about it. Include preliminary data to convince reviewers you can do the work. Cite all relevant work.

- Make sure not to be overly ambitious. Don’t propose to do so much that reviewers doubt your ability to complete the project. Rather, a project with clear, narrowly-defined goals may prove favorable to reviewers.

- Accurately represent the scope of your project; don’t exaggerate its impacts. Avoid bias. Be forthright about the limitations of your research.

- Ensure to address potential objections and concerns that reviewers may have with the proposed work. Show that you have carefully thought about the project by explaining your rationale.

- Use diagrams and figures effectively. Make sure they are not too small or contain too much information or details.

After writing your first draft, read it carefully to gain an overview of the logic of your argument. Answer the following questions:

- Is your proposal concise, explicit, and specific?

- Have you included all necessary assumptions, data points, and evidence in your proposal?

- Do you need to make structural changes like moving or deleting paragraphs or including additional tables or figures to strengthen your rationale?

- Have you answered most of the questions posed in Step 2 above in your proposal?

- Follow the length requirements in the proposal guidelines. Don't feel compelled to include everything you know!

- Use formatting techniques to make your proposal easy on the eye. Follow rules for font, layout, margins, citation styles , etc. Avoid walls of text. Use bolding and italicizing to emphasize points.

- Comply with all style, organization, and reference list guidelines to make it easy to reviewers to quickly understand your argument. If you don’t, it’s at best a chore for the reviewers to read because it doesn’t make the most convincing case for you and your work. At worst, your proposal may be rejected by the sponsoring agency without review.

- Using a reference management tool like Paperpile will make citation creation and formatting in your grant proposal quick, easy and accurate.

Now take time away from your proposal, for at least a week or more. Ask trusted mentors or collaborators to read it, and give them adequate time to give critical feedback.

- At this stage, you can return to any remaining administrative work while you wait for feedback on the proposal, such as finalizing your budget or updating your CV.

- Revise the proposal based on the feedback you receive.

- Don’t be discouraged by critiques of your proposal or take them personally. Receiving and incorporating feedback with humility is essential to grow as a grant writer.

Now you are almost ready to submit. This is exciting! At this stage, you need to block out time to complete all final checks.

- Allow time for proofreading and final editing. Spelling and grammar mistakes can raise questions regarding the rigor of your research and leave a poor impression of your proposal on reviewers. Ensure that a unified narrative is threaded throughout all documents in the application.

- Finalize your documents by following a checklist. Make sure all documents are in place in the application, and all formatting and organizational requirements are met.

- Follow all internal and external procedures. Have login information for granting agency and institution portals to hand. Double-check any internal procedures required by your institution (applications for large grants often have a deadline for sign-off by your institution’s Research or Grants Office that is earlier than the funding agency deadline).

- To avoid technical issues with electronic portals, submit your proposal as early as you can.

- Breathe a sigh of relief when all the work is done, and take time to celebrate submitting the proposal! This is already a big achievement.

Now you wait! If the news is positive, congratulations!

But if your proposal is rejected, take heart in the fact that the process of writing it has been useful for your professional growth, and for developing your ideas.

Bear in mind that because grants are often highly competitive, acceptance rates for proposals are usually low. It is very typical to not be successful on the first try and to have to apply for the same grant multiple times.

Here are some tips to increase your chances of success on your next attempt:

- Remember that grant writing is often not a linear process. It is typical to have to use the reviews to revise and resubmit your proposal.

- Carefully read the reviews and incorporate the feedback into the next iteration of your proposal. Use the feedback to improve and refine your ideas.

- Don’t ignore the comments received from reviewers—be sure to address their objections in your next proposal. You may decide to include a section with a response to the reviewers, to show the sponsoring agency that you have carefully considered their comments.

- If you did not receive reviewer feedback, you can usually request it.

You learn about your field and grow intellectually from writing a proposal. The process of researching, writing, and revising a proposal refines your ideas and may create new directions for future projects. Professional opportunities exist for researchers who are willing to persevere with submitting grant applications.

➡️ Secrets to writing a winning grant

➡️ How to gain a competitive edge in grant writing

➡️ Ten simple rules for writing a postdoctoral fellowship

A grant proposal should include all the documents listed as required by the sponsoring organization. Check what documents the granting agency needs before you start writing the proposal.

Granting agencies have strict formatting requirements, with strict page limits and/or word counts. Check the maximum length required by the granting agency. It is okay for the proposal to be shorter than the maximum length.

Expect to spend many hours, even weeks, researching and writing a grant proposal. Consequently, it is important to start early! Block time in your calendar for research, writing, and administration tasks. Allow extra time at the end of the grant-writing process to edit, proofread, and meet presentation guidelines.

The most important part of a grant proposal is the description of the project. Make sure that the research you propose in your project narrative is new, important, and viable, and that it meets the goals of the sponsoring organization.

A grant proposal typically consists of a set of documents. Funding agencies have specific requirements for the formatting and organization of each document. Make sure to follow their guidelines exactly.

10 Tips on how to write an effective research grant proposal

Grant Application

Marisha Fonseca

External funding is often essential for successful research. The importance of grant-writing skills is increasing, because the pressure to publish is putting a strain on resources and funding is now becoming more difficult to obtain. Nowadays, it doesn’t matter if researchers have path-breaking research ideas in mind; they need to put forth very persuasive proposals to convince grant committees to fund their project. Unfortunately, grant writing is generally considered very difficult, more so than the actual research. In this post, we will discuss how to write a grant proposal.

10 characteristics of an effective scientific research grant proposal

- Aims to advance science and benefit human knowledge, society, or the environment

- Has focused and measurable aims

- Has a sample whose results can be generalized (women, minorities, etc., should be adequately represented in the sample if necessary)

- Uses methods that are sufficiently rigorous, well developed, and appropriate to achieve the aims of the study

- Takes into consideration potential problems that can arise during the study and proposes alternatives to overcome these problems

- Is conducted by researchers with adequate training, experience, and expertise

- Is conducted in an environment that is likely to make it successful (e.g., with adequate institutional support or access to necessary facilities)

- Requires time and money commensurate to the tasks to be carried out

- Complies with ethical standards and is approved by an appropriate ethics committee

- Has a principal investigator who is independent and can lead others

Before you start writing your grant proposal

Although the requirements of grant applications may differ according to subject area and agency specifications, there are several key points to keep in mind while writing grant proposals, irrespective of your research topic or target funding agency.

a. Learn as much about the funding agency as possible