- Review article

- Open access

- Published: 30 January 2021

Understanding students’ behavior in online social networks: a systematic literature review

- Maslin Binti Masrom 1 ,

- Abdelsalam H. Busalim ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5826-8593 2 ,

- Hassan Abuhassna 3 &

- Nik Hasnaa Nik Mahmood 1

International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education volume 18 , Article number: 6 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

182k Accesses

29 Citations

20 Altmetric

Metrics details

The use of online social networks (OSNs) has increasingly attracted attention from scholars’ in different disciplines. Recently, student behaviors in online social networks have been extensively examined. However, limited efforts have been made to evaluate and systematically review the current research status to provide insights into previous study findings. Accordingly, this study conducted a systematic literature review on student behavior and OSNs to explicate to what extent students behave on these platforms. This study reviewed 104 studies to discuss the research focus and examine trends along with the important theories and research methods utilized. Moreover, the Stimulus-Organism-Response (SOR) model was utilized to classify the factors that influence student behavior. This study’s results demonstrate that the number of studies that address student behaviors on OSNs have recently increased. Moreover, the identified studies focused on five research streams, including academic purpose, cyber victimization, addiction, personality issues, and knowledge sharing behaviors. Most of these studies focused on the use and effect of OSNs on student academic performance. Most importantly, the proposed study framework provides a theoretical basis for further research in this context.

Introduction

The rapid development of Web 2.0 technologies has caused increased usage of online social networking (OSN) sites among individuals. OSNs such as Facebook are used almost every day by millions of users (Brailovskaia et al. 2020 ). OSNs allow individuals to present themselves via virtual communities, interact with their social networks, and maintain connections with others (Brailovskaia et al. 2020 ). Therefore, the use of OSNs has continually attracted young adults, especially students (Kokkinos and Saripanidis 2017 ; Paul et al. 2012 ). Given the popularity of OSNs and the increased number of students of different ages, many education institutions (e.g., universities) have used them to market their educational programs and to communicate with students (Paul et al. 2012 ). The popularity and ubiquity of OSNs have radically changed education systems and motivated students to engage in the educational process (Lambić 2016 ). The children of the twenty-first century are technology-oriented, and thus their learning style differs from previous generations (Moghavvemi et al. 2017a , b ). Students in this era have alternatives to how and where they spend time to learn. OSNs enable students to share knowledge and seek help from other students. Lim and Richardson ( 2016 ) emphasized that one important advantage of OSNs as an educational tool is to increase connections between classmates, which increases information sharing. Furthermore, the use of OSNs has also opened new communication channels between students and teachers. Previous studies have shown that students strengthened connections with their teachers and instructors using OSNs (e.g., Facebook, and Twitter). Therefore, the characteristics and features of OSNs have caused many students to use them as an educational tool, due to the various facilities provided by OSN platforms, which makes learning more fun to experience (Moghavvemi et al. 2017a ). This has caused many educational institutions to consider Facebook as a medium and as a learning tool for students to acquire knowledge (Ainin et al. 2015 ).

OSNs including Facebook, YouTube, and Twitter have been the most utilized platforms for education purposes (Akçayır and Akçayır 2016 ). For instance, the number of daily active users on Facebook reached 1.73 billion in the first quarter of 2020, with an increase of 11% compared to the previous year (Facebook 2020 ). As of the second quarter of 2020, Facebook has over 2.7 billion active monthly users (Clement 2020 ). Lim and Richardson ( 2016 ) empirically showed that students have positive perceptions toward using OSNs as an educational tool. A review of the literature shows that many studies have investigated student behaviors on these sites, which indicates the significance of the current review in providing an in-depth understanding of student behavior on OSNs. To date, various studies have investigated why students use OSNs and explored different student behaviors on these sites. Although there is an increasing amount of literature on this emerging topic, little research has been devoted to consolidating the current knowledge on OSN student behaviors. Moreover, to utilize the power of OSNs in an education context, it is important to study and understand student behaviors in this setting. However, current research that investigates student behaviors in OSNs is rather fragmented. Thus, it is difficult to derive in-depth and meaningful implications from these studies. Therefore, a systematic review of previous studies is needed to synthesize previous findings, identify gaps that need more research, and provide opportunities for further research. To this end, the purpose of this study is to explore the current literature in order to understand student behaviors in online social networks. Accordingly, a systematic review was conducted in order to collect, analyze, and synthesize current studies on student behaviors in OSNs.

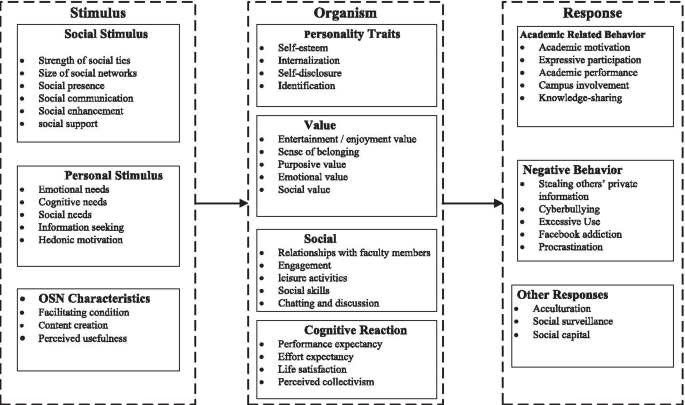

This study drew on the Stimulus-Organism-Response (SOR) model to classify factors and develop a framework for better understanding of student behaviors in the context of OSNs. The S-O-R model suggests that various aspects of the environment (S), incite individual cognitive and affective reactions (O), which in turn derives their behavioral responses (R) (Mehrabian and Russell 1974 ). In order to achieve effective results in a clear and understandable manner, five research questions were proposed as shown below.

What was the research regional context covered in previous studies?

What were the focus and trends of previous studies?

What were the research methods used in previous studies?

What were the major theories adopted in previous studies?

What important factors were studied to understand student usage behaviors in OSNs?

This paper is organized as follows. The second section discusses the concept of online social networks and their definition. The third section describes the review method used to extract, analyze, and synthesize studies on student behaviors. The fourth section provides the result of analyzing the 104 identified primary studies and summarizes their findings based on the research questions. The fifth section provides a discussion on the results based on each research question. The sixth section highlights the limitations associated with this study, and the final section provides a conclusion of the study.

- Online social networks

Since online social networks such as Facebook were introduced last decade, they have attracted millions of users and have become integrated into our daily routines. OSNs provide users with virtual spaces where they can find other people with similar interests to communicate with and share their social activities (Lambić et al. 2016 ). The concept of OSNs is a combination of technology, information, and human interfaces that enable users to create an online community and build a social network of friends (Borrero et al. 2014 ). Kum Tang and Koh ( 2017 ) defined OSNs as “web-based virtual communities where users interact with real-life friends and meet other people with shared interests” . A more detailed and well-cited definition of OSN was introduced by Boyd and Ellison ( 2008 ) who defined OSNs as “web-based services that allow individuals to (1) construct a public or semipublic profile within a bounded system, (2) articulate a list of other users with whom they share a connection, and (3) view and traverse their list of connections and those made by others within the system” . Due to its popularity, many researches have examined the effect of OSNs on different disciplines such as business (Kujur and Singh 2017 ), healthcare (Chung 2014 ; Lin et al. 2016 ; Mano 2014 ), psychology (Pantic 2014 ), and education (Hamid et al. 2016 , 2015 ; Roblyer et al. 2010 ).

The heavy use of OSNs by students has led many studies to examine both positive and negative effects of these sites on students, including the time spent on OSNs usage (Chang and Heo 2014 ; Wohn and Larose 2014 ), engagement in academic activities (Ha et al. 2018 ; Sheeran and Cummings 2018 ), as well as the effect of OSN on students’ academic performance. Lim and Richardson ( 2016 ) stated that the main reasons for students to use OSNs as an educational tool is to increase their interactions and establish connections with classmates. Tower et al. ( 2014 ) found that OSN platforms such as Facebook have the potential to improve student self-efficacy in learning and develop their learning skills to a higher level. Therefore, some education institutions have started to develop their own OSN learning platforms (Tally 2010 ). Mazman and Usluel ( 2010 ) highlighted that using OSNs for educational and instructional contexts is an idea worth developing because students spend a lot of time on these platforms. Yet, the educational activities conducted on OSNs are dependent on the nature of the OSNs used by the students (Benson et al. 2015 ). Moreover, for teaching and learning, instructors have begun using OSNs platforms for several other purposes such as increasing knowledge exchanges and effective learning (Romero-Hall 2017 ). On the other hand, previous studies have raised some challenges of using OSNs for educational purposes. For example, students tend to use OSNs as a social tool for entraining rather than an educational tool (Baran 2010 ; Gettman and Cortijo 2015 ). Moreover, the active use of OSNs on daily basis may develop students’ negative behavior such as addiction and distraction. In this context, Kitsantas et al. ( 2016 ) found that college students in the United States reported some concerns such as the OSNs usage can turn into addictive behavior, distraction, privacy threats, the negative impact on their emotional health, and the inability to complete the tasks on time. Another challenge of using OSNs as educational tools is gender differences. Kim and Yoo ( 2016 ) found some differences between male and female students concerning the negative impact of OSNs, for example, female students are more conserved about issues related to security, and the difficulty of task/work completion. Furthermore, innovation is a key aspect in the education process (Serdyukov 2017 ), however, using OSNs as an educational tool, students could lose creativity due to the easy access to everything using these platforms (Mirabolghasemi et al. 2016 ).

Review method

This study employed a Systematic Literature Review (SLR) approach in order to answer the research questions. The SLR approach creates a foundation that advances knowledge and facilitates theory development for a specific topic (Webster and Watson 2002 ). Kitchenham and Charters ( 2007 ) defined SLR as a process of identifying, evaluating, and synthesizing all available research that is related to research questions, area of research, or new phenomenon. This study follows Kitchenhand and Charters’ guidelines (Kitchenham 2004 ), which state that the SLR approach involves three main stages: planning the review, conducting the review, and reporting the review results. There are several motivations for carrying out this systematic review. First, to summarize existing knowledge and evidence on research related to OSNs such as the theories, methods, and factors that influence student behaviors on these platforms. Second, to discover the current research focus and trends in this setting. Third, to propose a framework that classifies the factors that influence student behaviors on OSNs using the S-O-R model. The reasons for using S-O-R model in this study are twofold. First, S-O-R is a crucial theoretical framework to understand individuals’ behavior, and it has been extensively used in previous studies on consumer behavior (Wang and Chang 2013 ; Zhang et al. 2014 ; Zhang and Benyoucef 2016 ), and online users’ behavior (Islam et al. 2018 ; Luqman et al. 2017 ). Second, using the S-O-R model can provide a structured manner to understand the effect of the technological features of OSNs as environmental stimuli on individuals’ behavior (Luqman et al. 2017 ). Therefore, the application of the S-O-R model can provide a guide in the OSNs literature to better understand the potential stimulus and organism factors that drive a student’s behavioral responses in the context of OSNs. The SLR was guided by five research questions (see “ Introduction ” section), which provide an in-depth understanding of the research topic. The rationale and motivation beyond considering these questions are stated in Table 1 .

Stage one: Planning

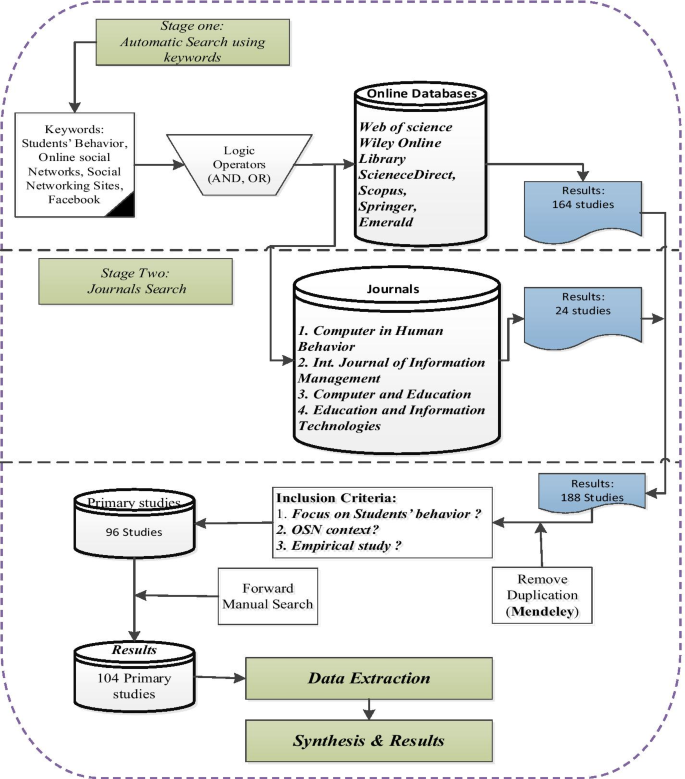

Before conducting any SLR, it is necessary to clarify the goal and the objectives of the review (Kitchenham and Charters 2007 ). After identifying the review objectives and the research questions, in the planning stage, it is important to design the review protocol that will be used to conduct the review (Kitchenham and Charters 2007 ). Using a clear review protocol will help define criteria for selecting the literature source, database, and search keywords. Review protocol reduce research bias and specifies the research method used to perform a systematic review (Kitchenham and Charters 2007 ). Figure 1 shows the review protocol used for this study.

Review protocol

Stage two: Conducting the review

In this stage relevant literature was collected using a two-stage approach, which was followed by the removal of duplicated articles using Mendeley software. Finally, the researchers applied selection criteria to identify the most relevant articles to the current review. The details of each step of this stage are discussed below:

Literature identification and collection

This study used a two-stage approach (Webster and Watson 2002 ) to identify and collect relevant articles for review. In the first stage, this study conducted a systematic search to identify studies that address student behaviors and the use of online social networks using selected academic databases, including the Web of Science, Wiley Online Library ScienceDirect, Scopus, Emerald, and Springer. The choice of these academic databases is consistent with previous SLR studies (Ahmadi et al. 2018 ; Balaid et al. 2016 ; Busalim and Hussin 2016 ). Derived from the structure of this review and the research questions, these online databases were searched by focusing on title, abstract, and keywords. The search in these databases started in May 2019 using the specific keywords of “students’ behavior”, “online social networking”, “social networking sites”, and “Facebook”. This study performed several searches in each database using Boolean logic operators (i.e., AND and OR) to obtain a large number of published studies related to the review topic.

The results from this stage were 164 studies published between 2010 and 2018. In the second stage, important peer-reviewed journals were checked to ensure that all relevant articles were collected. We used the same keywords to search on information systems and education journals such as Computers in Human Behavior, International Journal of Information Management, Computers and Education, and Education and Information Technologies. These journals among the top peer-reviewed journals that publish topics related to students' behavior, education technologies, and OSNs. The result from both stages was 188 studies related to student behaviors in OSN. Table 2 presents the journals with more than two articles published in these areas.

Study selection

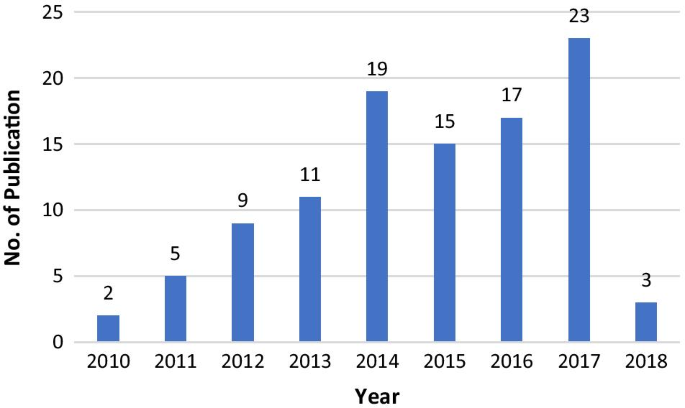

Following the identification of these studies, and after deleting duplicated studies, this study examined title, abstract, or the content of each study using three selection criteria: (1) a focus on student behavior; (2) an examination of the context of online social networks; (3) and a qualification as an empirical study. After applying these criteria, a total of 96 studies remained as primary studies for review. We further conducted a forward manual search on a reference list for the identified primary studies, through which an additional 8 studies were identified. A total of 104 studies were collected. As depicted in Fig. 2 , the frequency of published articles related to student behaviors in online social networks has gradually increased since 2010. In this regard, the highest number of articles were published in 2017. We can see that from 2010 to 2012 the number of published articles was relatively low and significant growth in published articles was seen from 2013 to 2017. This increase reveals that studying the behavior of students on different OSN platforms is increasingly attractive to researchers.

Timeline of publication

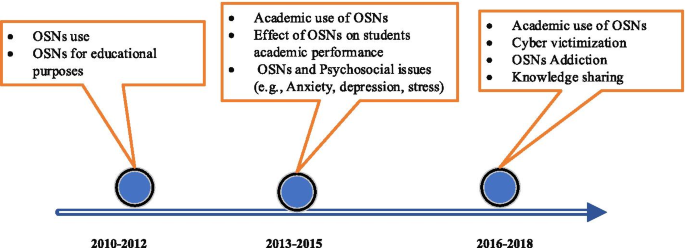

For further analysis, this study summarized the key topics covered during the review timeline. Figure 3 visualizes the development of OSNs studies over the years. Studies in the first three years (2010–2012) revolved around the use of OSNs by students and the benefits of using these platforms for educational purposes. The studies conducted between 2013 and 2015 mostly focused on the effect of using OSNs on student academic performance and achievement. In addition, in the same period, several studies examined important psychological issues associated with the use of OSNs such as anxiety, stress, and depression. In the years 2016 to 2018, OSNs studies were expanded to include cyber victimization behavior, OSN addiction behavior such as Facebook addiction, and how OSNs provide a collaborative platform that enables students to share information with their colleagues.

Evolution of OSNs studies over the years

Review results

To analyze the identified studies, this study guided its review using four research questions. Using research questions allows the researcher to synthesize findings from previous studies (Chan et al. 2017 ). The following subsection provides a detailed discussion of each of these research questions.

RQ1: What was the research regional context covered in previous studies?

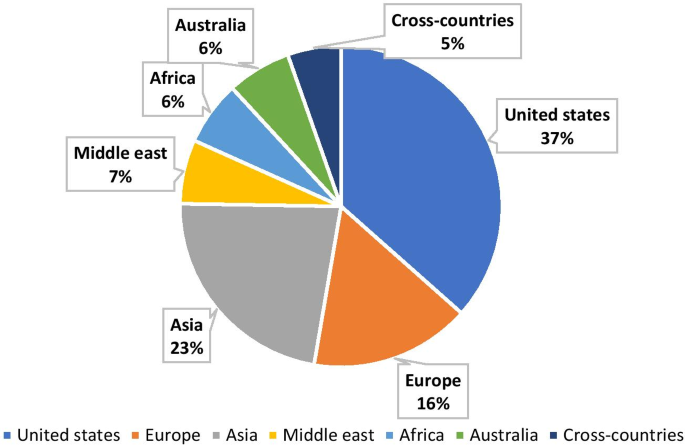

As shown in Fig. 3 , most primary studies were conducted in the United States (n = 37), followed by Asia (n = 21) and Europe (n = 15). Relatively few studies were conducted in Australia, Africa, and the Middle East (n = 6 each), and only five studies were conducted in more than one country. Most of these empirical studies used university or college students to examine and validate the research models. Furthermore, many of these studies examined student behavior by considering Facebook as an online social network (n = 58) and a few studies examined student behavior on Microblogging platforms like Twitter (n = 7). The rest of the studies used multiple online social networks such as Instagram, YouTube, and Moodle (n = 31).

As shown in Fig. 4 , most of the reviewed studies are conducted in the United States (US). Furthermore, these studies considered Facebook as the main OSN platform. However, the focus on examining the usage behavior of Facebook in Western countries, particularly the US, is one of the challenges of Facebook research, because Facebook is used in many countries with 80% of its users are outside of the US (Peters et al. 2015 ).

Distribution of published studies by region

RQ2: What were the focus and trends of previous studies?

The results indicate that the identified primary studies for student behaviors on online social networks covered a wide spectrum of different research contexts. Further examination shows that there are five research streams in the literature.

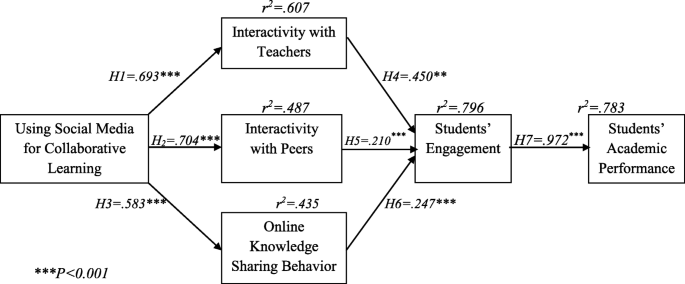

The first research stream focused on using OSNs for academic purposes. The educational usage of OSNs relies on their purpose of use. OSNs can improve student engagement in a course and provide them with a sense of connection to their colleagues (Lambić 2016 ). However, the use of OSNs by students can affect their education as students can easily shift from using OSNs for educational to entertainment purposes. Thus, many studies under this stream focus on the effect of OSNs use on student academic performance. For instance, Lambić ( 2016 ) examined the effect of frequent Facebook use on the academic performance of university students. The results showed that students using Facebook as an educational tool to facilitate knowledge sharing and discussion positively impacted academic performance. Consistent with this result, Ainin et al. ( 2015 ) found that data from 1165 university students revealed a positive relationship between Facebook use and student academic performance. On the other hand, Paul et al. ( 2012 ) found that time spent on OSNs negative impacted student academic behavior. Moreover, the results statistically highlight that increased student attention spans resulted in increased time spent on OSNs, which eventually results in a negatively effect on academic performance. The results from Karpinski et al. ( 2013 ) showed that the effect of OSNs usage on student academic performance could differ from one country to another.

In summary, previous studies on the relationship between OSN use and academic performance show mixed results. From the reviewed studies, there were disparate results due to a few reasons. For example, recent studies found that multitasking plays an important role in determining the relationship between OSN usage and student academic performance. Karpinski et al. ( 2013 ) found a negative relationship between using social network sites (SNSs) and Grade Point Average (GPA) that was moderated by multitasking. Moreover, results from Junco ( 2015 ), illustrated that besides multitasking, student class rank is another determinant of the relationship between OSN platforms like Facebook and academic performance. The results revealed that senior students spent significantly less time on Facebook while doing schoolwork than freshman and sophomore students.

The second research stream is related to cyber victimization. Studies in this stream focused on negative interactions on OSNs like Facebook, which is the main platform where cyber victimization occurs (Kokkinos and Saripanidis 2017 ). Moreover, most studies in this stream examined the cyberbullying concept on OSNs. Cyberbullying is defined as “any behavior performed through electronic media by individuals or groups of individuals that repeatedly communicates hostile or aggressive messages intended to inflict harm or discomfort on others” (Tokunaga 2010 , p. 278). For instance, Gahagan et al. ( 2016 ) investigated the experiences of college students with cyberbullying on SNSs, and the results showed that 46% of the tested sample witnessed someone who had been bullied through the use of SNSs. Walker et al. ( 2011 ) conducted an exploratory study among undergraduate students to investigate their cyberbullying experiences. The results of the study highlighted that the majority of respondents knew someone who had been bullied on SNSs (Benson et al. 2015 ).

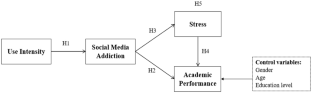

The third research stream focused on student addiction to OSNs use. Recent research has shown that excessive OSN use can lead to addictive behavior among students (Shettar et al. 2017 ). In this stream, Facebook was the main addictive ONS platform that was investigated (Shettar et al. 2017 ; Hong and Chiu 2016 ; Koc and Gulyagci 2013 ). Facebook addiction is defined as an excessive attachment to Facebook that interferes with daily activities and interpersonal relationships (Elphinston and Noller 2011 ). According to Andreassen et al. ( 2012 ), Facebook addiction has six general characteristics including salience, tolerance, mood modification, withdrawal, conflict, and relapse. As university students frequently have high levels of stress due to various commitments, such as assignment deadlines, exams, and high pressure to perform, they tend to use Facebook for mood modification (Brailovskaia and Margraf 2017 ; Brailovskaia et al. 2018 ). On further analysis, it was noticed that Facebook addiction among students was associated with other factors such as loneliness (Shettar et al. 2017 ), personality traits (i.e., openness agreeableness, conscientiousness, emotional stability, and extraversion) (Błachnio et al. 2017 ; Tang et al. 2016 ), and physical activities (Brailovskaia et al. 2018 ). Studies have examined student addiction behavior on different OSNs platforms. For instance, Ndasauka et al. ( 2016 ), empirically examined excessive Twitter use among college students. Kum Tang and Koh ( 2017 ) investigated the prevalence of different addiction behaviors (i.e., food and shopping addiction) and effective disorders among college students. In addition, a study by Chae and Kim (Chae et al. 2017 ) examined psychosocial differences in ONS addiction between female and male students. The results of the study showed that female students had a higher tendency towards OSNs addiction than male students.

The fourth stream of research highlighted in this review focused on student personality issues such as self-disclosure, stress, depression, loneliness, and self-presentation. For instance, Chen ( 2017 ) investigated the antecedents that predict positive student self-disclosure on SNSs. Tandoc et al. ( 2015 ) used social rank theory and Facebook envy to test the depression scale between college students. Skues et al. ( 2012 ) examined the relationship between three traits in the Big Five Traits model (neuroticism, extraversion, and openness) and student Facebook usage. Chang and Heo ( 2014 ) investigated the factors that explain the disclosure of a student’s personal information on Facebook.

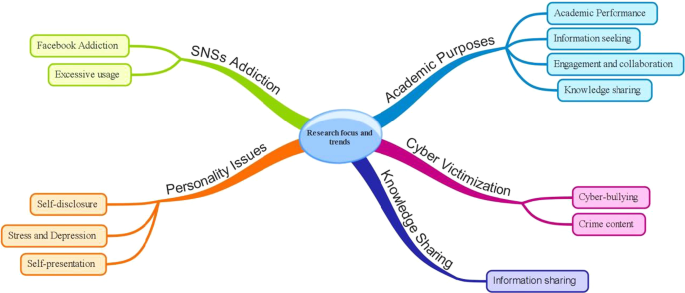

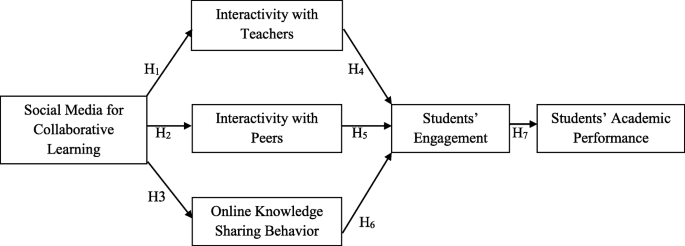

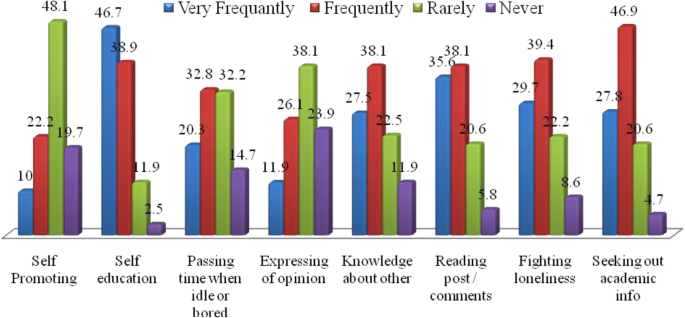

The fifth reviewed research stream focused on student knowledge sharing behavior. For instance, Kim et al. ( 2015 ) identified the personal factors (self-efficacy) and environmental factors (strength of social ties and size of social networks) that affect information sharing behavior amongst university students. Eid and Al-Jabri ( 2016 ) examined the effect of various SNS characteristics (file sharing, chatting and online discussion, content creation, and enjoyment and entertainment) on knowledge sharing and student learning performance. Moghavvemi et al. ( 2017a , b ) examined the relationship between enjoyment, perceived status, outcome expectations, perceived benefits, and knowledge sharing behavior between students on Facebook. Figure 5 provides a mind map that shows an overview of the research focus and trends found in previous studies.

Reviewed studies research focus and trends

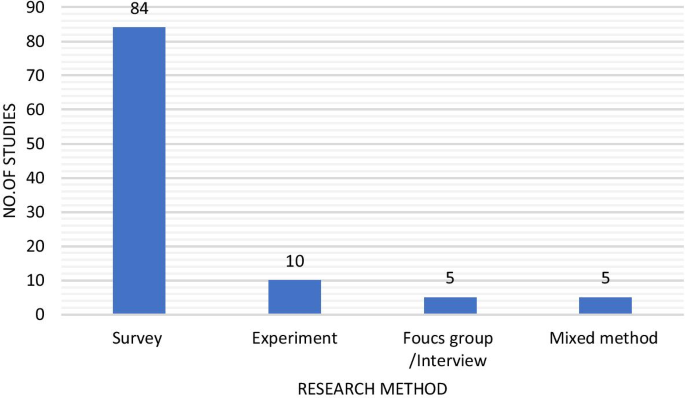

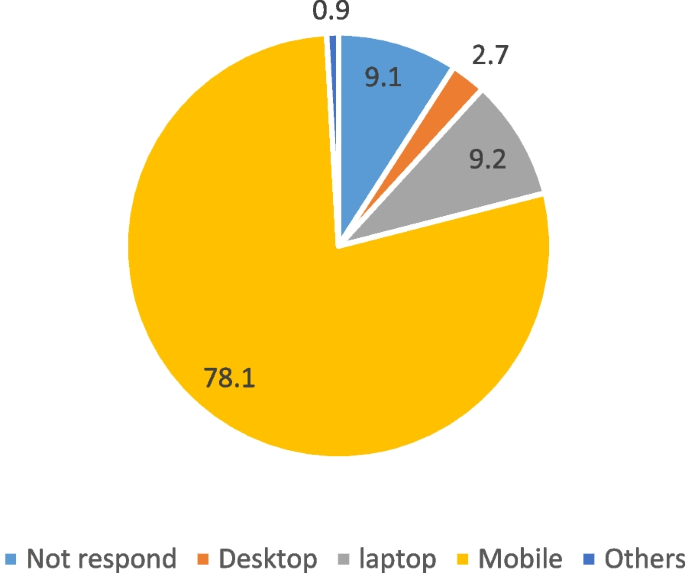

RQ3: What were the research methods used in previous studies?

As presented in Fig. 6 , previous studies used several research methods to examine student behavior on online social networks. Surveys were the method used most frequently in primary studies to understand the different types of determinants that effect student behaviors on online social networks, followed by the experiment method. Studies used the experiment method to examine the effect of online social networks content and features on student behavior, For example, Corbitt-Hall et al. ( 2016 ) had randomly assigned students to interact with simulated Facebook content that reflected various suicide risk levels. Singh ( 2017 ) used data mining techniques to collect student interaction data from different social networking sites such as Facebook and Twitter to classify student academic activities on these platforms. Studies that investigated student intentions, perceptions, and attitudes towards OSNs used survey data. For instance, Doleck et al. ( 2017 ) distributed an online survey to college students who used Facebook and found that perceived usefulness, attitude, and self-expression were influential factors towards the use of online social networks. Moreover, Ndasauka et al. ( 2016 ) used the survey method to assess the excessive use of Twitter among college students.

Research method distribution

RQ4: What were the major theories adopted in previous studies?

The results from the SLR show that previous studies used several theories to understand student behavior in online social networks. Table 3 depicts the theories used in these studies, with Use and Gratification Theory (UGT) being the most popular theory use to understand students' behaviors (Asiedu and Badu 2018 ; Chang and Heo 2014 ; Cheung et al. 2011 ; Hossain and Veenstra 2013 ). Furthermore, the social influence theory and the Big Five Traits model were applied in at least five studies each. The theoretical insights into student behaviors on online social networks provided by these theories are listed below:

Motivation aspect: since the advent of online social networks, many studies have been conducted to understand what motivates students to use online social networks. Theories such as UGT have been widely used to understand this issue. For example, Hossain and Veenstra ( 2013 ) conducted an empirical study to investigate what drives university students in the United States of America to use Social Networking Sites (SNSs) using the theoretical foundation of UGT. The study found that the geographic or physical displacement of students affects the use and gratification of SNSs. Zheng Wang et al. ( 2012a , b ) explained that students are motivated to use social media by their cognitive, emotional, social, and habitual needs as well as that all four categories significantly drive students to use social media.

Social-related aspect: Social theories such as Social Influence Theory, Social Learning Theory, and Social Capital Theory have also been used in several previous studies. Social Influence Theory determines what individual behaviors or opinions are affected by others. Venkatesh, Morris, Davis, and Davis (2003) defined social influence as “the degree to which an individual perceives that important others believe he or she should use a new system” . Cheung et al. ( 2011 ) applied Social Influence Theory to examine the effect of social influence factors (subjective norms, group norms, and social identity) on intentions to use online social networks. The empirical results from 182 students revealed that only Group Norms had a significant effect on student intentions to use OSNs. Other studies attempted to empirically examine the effect of other social theories. For instance, Liu and Brown ( 2014 ) adapted Social Capital Theory to investigate whether college students' self-disclosure on SNSs directly affected their social capital. Park et al. ( 2014a , b ) investigated the effect of using SNSs on university student learning outcomes using social learning theory.

Behavioral aspect: This study have noticed that the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB), Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA), Technology Acceptance Model (TAM), Unified Theory of Acceptance, and Use of Technology (UTAUT) were also utilized as a theoretical foundation in a number of primary studies. These theories have been widely applied in the information systems (IS) field to provide insights into information technology adoption among individuals (Zhang and Benyoucef 2016 ). In the context of online social networks, there were empirical studies that adapted these theories to understand student usage behaviors towards online social networks such as Facebook. For example, Doleck et al. ( 2017 ) applied TAM to investigate college student usage intentions towards SNSs. Chang and Chen ( 2014 ) applied TRA and TPB to investigate why college students share their location on Facebook. In addition, a recent study used UTAUT to examine student perceptions towards using Facebook as an e-learning platform (Moghavvemi et al. 2017a , b ).

RQ5: What important factors were studied to understand student usage behaviors in OSNs?

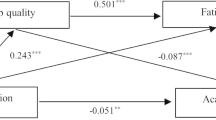

Throughout the SLR, this study has been able to identify the potential factors that influence student behaviors in online social networks. Furthermore, to synthesize these factors and provide a comprehensive overview, this study proposed a framework based on the Stimulus-Organism-Response (S-O-R) model. The S-O-R model was developed in environmental psychology by Mehrabian and Russell ( 1974 ). According to Mehrabian and Russell ( 1974 ), environmental cues act as stimuli that can affect an individual’s internal cognitive and affective states, which subsequently influences their behavioral responses. To do so, this study extracted all the factors examined in 104 identified primary studies and classified them into three key concepts: stimulus, organism, and response. The details on the important factors of each component are presented below.

Online social networks stimulus

Stimulus factors are triggers that encourage or prompt students to use OSNs. Based on the SLR results, there are three stimulus dimensions: social stimulus, personal stimulus, and OSN characteristics. Social stimuli are cues embedded in the OSN that drive students to use these platforms. As shown in Fig. 7 , this study has identified six social stimulus factors including social support, social presence, social communication, social enhancement, social network size, and strength of social ties. Previous studies found that social aspects are a potential driver of student usage of OSNs. For instance, Kim et al. ( 2011 ) explored the motivation behind college student use of OSNs and found that seeking social support is one of the primary usage triggers. Lim and Richardson ( 2016 ) stated that using OSNs as educational tools will increase interactions and establish connections between students, which will enhance their social presence. Consistent with this, Cheung et al. ( 2011 ) found that social presence and social enhancement both have a positive effect on student use of OSNs. Other studies have tested the effect of other social factors such as social communication (Lee 2015 ), social network size, and strength of social ties (Chang and Heo 2014 ; Kim et al. 2015 ). Personal stimuli are student motivational factors associated with a specific state that affects their behavioral response. As depicted in Table 4 , researchers have tested different personal student needs that stimulate OSN usage. For instance, Zheng Wang et al. ( 2012a , b ) examined the emotional, social, and cognitive needs that drive students to use OSNs. Moghavvemi et al. ( 2017a , b ) empirically showed that students with a hedonic motivation were willing to use Facebook as an e-learning tool.

Classification framework for student behaviors in online social networks

OSN website characteristics are stimuli related to the cues implanted in an OSN website. In the reviewed studies, it was found that the most well studied OSN characteristics are usefulness and ease of use. Ease of use refers to student perceptions on the extent to which OSN are easy to use whereas usefulness refers to the degree that students believed that using OSN was helpful in enhancing their task performance (Arteaga Sánchez et al. 2014 ). Although student behaviors in OSNs have been widely studied, few studies have focused on OSN characteristics that stimulate student behaviors. For example, Eid and Al-Jabri ( 2016 ) examined the effect of OSN characteristics such as chatting, discussion, content creation, and file sharing. The results showed that file sharing, chatting, and discussion had a positive impact on student knowledge sharing behavior. In summary, Table 4 shows the stimulus factors identified in previous studies and their classification.

Online social networks organisms

Organism in this study’s framework refers to student internal evaluations towards using OSNs. There are four types of organism factors that have been highlighted in the literature. These types include personality traits, values, social, and cognitive reactions. Student personality traits influence the use of OSNs (Skues et al. 2012 ). As shown in Table 4 , self-esteem and self-disclosure were the most examined personality traits associated with student OSN behaviors. Self-esteem refers to an individual’s emotional evaluation of their own worth (Chen 2017 ). For example, Wang et al. ( 2012a , b ) examined the effect of the Big Five personality traits on student use of specific OSN features. The results found that students with high self-esteem were more likely to comment on other student profiles. Self-disclosure refers to the process by which individuals share their feelings, thoughts, information, and experiences with others (Dindia 1995 ). Previous studies have examined student self-disclosure in OSNs to explore information disclosure behavior (Chang and Heo 2014 ), location disclosure (Chang and Chen 2014 ), self-disclosure, and mental health (Zhang 2017 ). The second type of organism factors is value. It has been noticed that there are several value related factors that affect student internal organisms in OSNs. As shown in Table 4 , entertainment and enjoyment factors were the most common value examined in previous studies. Enjoyment is one of the potential drivers of student OSN use (Nawi et al. 2017 ). Eid and Al-Jabri ( 2016 ) found that YouTube is the most dominant OSN platform used by students for enjoyment and entertainment. Moreover, enjoyment and entertainment directly affected student learning performance.

Social organism refers to the internal social behavior of students that affect their use of OSNs. Students interact with OSN platforms when they experience positive social reactions. Previous studies have examined some social organism factors including relationship with faculty members, engagement, leisure activities, social skills, and chatting and discussion. The fourth type of organism factors is cognitive reactions. Parboteeah et al. ( 2009 ) defined cognitive reaction as “the mental process that occurs in an individual’s mind when he or she interacts with a stimulus” . The positive or negative cognitive reaction of students influences their responses towards OSNs. Table 5 presents the most common organism reactions that effect student use of OSNs.

Online social networks response

In this study’s framework, response refers to student reactions to OSNs stimuli and organisms. As shown in Table 5 , academic related behavior and negative behavior are the most common student responses towards OSNs. Studying the effect of OSN usage on student academic performance has been the most common research topic (Lambić 2016 ; Paul et al. 2012 ; Wohn and Larose 2014 ). On the other hand, other studies have examined the negative behavior of students during their usage of ONS, mostly towards ONS addiction (Hong and Chiu 2016 ; Shettar et al. 2017 ) or cyberbullying (Chen 2017 ; Gahagan et al. 2016 ). Table 6 summarizes student responses associated with OSNs use in previous studies.

Discussion and implications

The last two decades have witnessed a dramatic growth in the number of online social networks used among the youth generation. Examining student behaviors on OSN platforms has increasingly attracted scholars. However, there has been little effort to summarize and synthesize these findings. In this review study, a systematic literature review was conducted to synthesize previous research on student behaviors in OSNs to consolidate the factors that influence student behaviors into a classification framework using the S-O-R model. A total of 104 journal articles were identified through a rigorous and systematic search procedure. The collected studies from the literature show an increasing interest in the area ever since 2010. In line with the research questions, our analysis offers insightful results of the research landscape in terms of research regional context, studies focus trends, methodological trends, factors, and theories leveraged. Using the S-O-R model, we synthesized the reviewed studies highlighting the different stimuli, organism, and response factors. We synthesize and classify these factors into social stimuli, personal stimuli, and OSN characteristics, organism factors; personality traits, value, social, and cognitive reaction, and response; academic related behavior, negative behavior, and other responses.

Research regional perspective

The first research question focused on research regional context. The review revealed that most of the studies were conducted in the US followed by European countries, with the majority focusing on Facebook. The results show that the large majority of the studies were based on a single country. This indicates a sustainable research gap in examining the multi-cultural factors in multiple countries. As OSN is a common phenomenon across many counties, considering the culture and background differences can play an essential role in understanding students’ behavior on these platforms. For example, Ifinedo ( 2016 ) collected data from four countries in America (i.e., USA, Canada, Argentina, and Mexico) to understand students’ pervasive adoption of SNSs. The results from the study revealed that the individualism–collectivism culture factor has a positive impact on students' pervasive adoption behavior of SNSs, and the result reported high level of engagement from students who have more individualistic cultures. In the same manner, Kim et al. ( 2011 ) found some cultural differences in use of the SNSs platforms between Korean and US students. For example, considering the social nature of SNSs, the study found that Korean students rely more on online social relationships to obtain social support, where US students use SNSs to seek entertainment. Furthermore, Karpinski et al. ( 2013 ) empirically found significant differences between US and European students in terms of the moderating effect of multitasking on the relationship between SNS use and academic achievement of students. The confirms that culture issues may vary from one country to another, which consequently effect students’ behavior to use OSNs (Kim et al. 2011 ).

Studies focus and trends

The second research question of this review focused on undersigning the topics and trends that have been discussed in extant studies. The review revealed evidence of five categories of research streams based on the research focus and trend. As shown in Fig. 5 , most of the reviewed studies are in the first stream, which is using OSNs for academic purposes. Moreover, the trend of these studies in this stream focus on examining the effect of using OSNs on students’ academic performance and investigating the use of OSNs for educational purposes. However, a number of other trends are noteworthy. First, as cyber victimization is a relatively new concept, most of the studies provide rigorous effort in exporting the concept, and the reasons beyond its existence among students; however, we have noticed that no effort has been made to investigate the consequences of this negative behavior on students’ academic performance, social life, and communication. Second, we identified only two studies that examined the differences between undergraduate and postgraduate students in terms of cyber victimization. Therefore, there are many avenues for further research to untangle the demographic, education level, and cultural differences in this context. Third, our analysis revealed that Facebook was the most studied ONS platform in terms of addiction behavior, however, over the last ten years, the rapid growth of using image-based ONS such as Instagram and Pinterest has attracted many students (Alhabash and Ma 2017 ). For example, Instagram represents the fastest growing OSNs among young adult users age between 18 and 29 years old (Alhabash and Ma 2017 ). The overwhelming majority of the studies focus on Facebook users, and very few studies have examined excessive Instagram use (Kırcaburun and Griffiths 2018 ; Ponnusamy et al. 2020 ). Although OSNs have many similar features, each platform has unique features and a different structure. These differences in OSNs platforms urge further research to investigate and understand the factors related to excessive and addiction use by students (Kircaburun and Griffiths 2018 ). Therefore, based on the current research gaps, future research agenda including three topics/trend need to be considered. We have developed research questions for each topic as a direction for any further research as shown in Table 7 .

Theories and research methods

The third and fourth research questions focused on understanding the trends in terms of research methods and theories leveraged in existing studies. In relation to the third research question, the review highlighted evidence of the four research methods (i.e., survey, experiment, focus group/interview, and mix method) with a heavy focus on using a quantitative method with the majority of studies conducting survey. This may call for utilizing a variety of other research methods and research design to have more in-depth understanding of students’ behavior on OSN. For example, we noticed that few studies leveraged qualitative methods such as interviews and focus groups (n = 5). In addition, using mix method may derive more results and answer research questions that other methods cannot answer (Tashakkori and Teddlie 2003 ). Experimental methods have been used sparingly (n = 10), this may trigger an opportunity for more experimental research to test different strategies that can be used by education institutions to leverage the potential of OSN platforms in the education process. Moreover, considering that students’ attitude and behavior will change over time, applying longitudinal research method may offer opportunities to explore students’ attitude and behavior patterns over time.

The fourth research question focused on understanding the theoretical underpinnings of the reviewed studies. The analysis revealed two important insights; (1) a substantial number of the reviewed studies do not explicitly use an applied theory, and (2) out of the 34 studies that used theory, nine studies applied UGT to understand the motivation beyond using the OSN. Our findings categorized these theories under three aspects; motivational, social, and behavioral. While each aspect and theory offers useful lenses in this context, there is a lack of leveraging other theories in the extant literature. This motivates researchers to underpin their studies in theories that provide more insights into these three aspects. For example, majority of the studies have applied UGT to understand students’ motivate for using OSNs. However, using other motivational theories could uncover different factors that influence students' motivation for using OSNs. For example, self-determination theory (SDT) focuses on the extent to which individual’s behavior is self-motivated and determined. According to Ryan and Deci ( 2000 ), magnitude and types both shape individuals’ extrinsic motivation. The extrinsic motivation is a spectrum and depends on the level of self-determination (Wang et al. 2019 ). Therefore, the continuum aspect proposed by SDT can provide in-depth understanding of the extrinsic motivation. Wang et al. ( 2016 ) suggested that applying SDT can play a key role in understanding SNSs user satisfaction.

Another theoretical perspective that is worth further exploration relates to the psychological aspect. Our review results highlighted that a considerable number of studies focused on an important issue arising from the daily use of OSNs, such as excessive use/addiction (Koc and Gulyagci 2013 ; Shettar et al. 2017 ), Previous studies have investigated the behavior aspect beyond these issues, however, understanding the psychological aspect of Facebook addiction is worth further investigation. Ryan et al. ( 2014 ) reviewed Facebook addiction related studies and found that Facebook addiction is also linked to psychological factors such as depression and anxiety.

Factors that influence students behavior: S-O-R Framework

The fifth research question focused on determining the factors studies in the extant literature. The review analysis showed that stimuli factors included social, personal, and OSNs website stimuli. However, different types of stimuli have received less attention than other stimuli. Most studies leveraged the social and students’ personal stimuli. Furthermore, few studies conceptualized the OSNs websites characterises in terms of students beliefs about the effect of OSNs features and functions (e.g., perceived ease of use, user friendly) on students stimuli; it would be significant to develop a typology of the OSNs websites stimuli and systematically examine their effect on students’ attitude and behavior. We recommend applying different theories (as mentioned in Theories and research methods section) as an initial step to further identify stimuli factors. The results also highlight that cognitive reaction plays an essential role in the organism dimension. When students encounter stimuli, their internal evaluation is dominated by emotions. Therefore, the cognitive process takes place between students’ usage behavior and their responses (e.g., effort expectancy). In this review, we reported few studies that examined the effect of the cognitive reaction of students.

Response factors encompass students’ reaction to OSNs platforms stimuli and organism. Our review revealed an unsurprisingly dominant focus on the academic related behavior such as academic performance. While it is important to examine the effect of various stimuli and organism factors on academic related behavior and OSNs negative behavior, the psychological aspect beyond OSNs negative behavior is equallty important.

Limitations

Similar to other systematic review studies, this study has some limitations. The findings of our review are constrained by only empirical studies (journal articles) that meet the inclusion criteria. For instance, we only used the articles that explicitly examined students’ behavior in OSNs. Moreover, other different types of studies such as conference proceedings are not included in our primary studies. Further research efforts can gain additional knowledge and understanding from practitioner articles, books and, white papers. Our findings offer a comprehensive conceptual framework to understand students’ behavior in OSNs; future studies are recommended to perform a quantitative meta-analysis to this framework and test the relative effect of different stimuli factors.

Conclusions

The use of OSNs has become a daily habit among young adults and adolescents these days (Brailovskaia et al. 2020 ). In this review, we used a rigorous systematic review process and identified 104 studies related to students’ behavior in OSNs. We systematically reviewed these studies and provide an overview of the current state of this topic by uncovering the research context, research focus, theories, and research method. More importantly, we proposed a classification framework based on S-O-R model to consolidate the factors that influence students in online social networks. These factors were classified under different dimensions in each category of the S-O-R model; stimuli (Social Stimulus, Personal Stimulus, and OSN Characteristics), organism (Personality traits, value, social, Cognitive reaction), and students’ responses (academic-related behavior, negative behavior, and other responses). This framework provides the researchers with a classification of the factors that have been used in previous studies which can motivate further research on the factors that need more empirical examination (e.g., OSN characteristics).

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Ahmadi, H., Arji, G., Shahmoradi, L., Safdari, R., Nilashi, M., & Alizadeh, M. (2018). The application of internet of things in healthcare: A systematic literature review and classification. Universal Access in the Information Society . https://doi.org/10.1007/s10209-018-0618-4 .

Article Google Scholar

Ainin, S., Naqshbandi, M. M., Moghavvemi, S., & Jaafar, N. I. (2015). Facebook usage, socialization and academic performance. Computers and Education, 83, 64–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2014.12.018 .

Akbari, E., Naderi, A., Simons, R.-J., & Pilot, A. (2016). Student engagement and foreign language learning through online social networks. Asian-Pacific Journal of Second and Foreign Language Education, 1 (1), 4. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40862-016-0006-7 .

Akcaoglu, M., & Bowman, N. D. (2016). Using instructor-led Facebook groups to enhance students’ perceptions of course content. Computers in Human Behavior, 65, 582–590. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.05.029 .

Akçayır, G., & Akçayır, M. (2016). Research trends in social network sites’ educational use: A review of publications in all SSCI journals to 2015. Review of Education, 4 (3), 293–319.

Alhabash, S., & Ma, M. (2017). A tale of four platforms: Motivations and uses of Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and Snapchat among college students. Social Media + Society, 3 (1), 205630511769154. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305117691544 .

Amador, P., & Amador, J. (2014). Academic advising via Facebook: Examining student help seeking. Internet and Higher Education, 21, 9–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2013.10.003 .

Andreassen, C. S., Torsheim, T., Brunborg, G. S., & Pallesen, S. (2012). Development of a Facebook addiction scale. Psychological Reports, 110 (2), 501–517. https://doi.org/10.2466/02.09.18.PR0.110.2.501-517 .

Arteaga Sánchez, R., Cortijo, V., & Javed, U. (2014). Students’ perceptions of Facebook for academic purposes. Computers and Education, 70, 138–149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2013.08.012 .

Asiedu, N. K., & Badu, E. E. (2018). Motivating issues affecting students’ use of social media sites in Ghanaian tertiary institutions. Library Hi Tech, 36 (1), 167–179. https://doi.org/10.1108/LHT-10-2016-0108 .

Asterhan, C. S. C., & Bouton, E. (2017). Teenage peer-to-peer knowledge sharing through social network sites in secondary schools. Computers & Education, 110, 16–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2017.03.007 .

Balaid, A., Abd Rozan, M. Z., Hikmi, S. N., & Memon, J. (2016). Knowledge maps: A systematic literature review and directions for future research. International Journal of Information Management, 36 (3), 451–475.

Baran, B. (2010). Facebook as a formal instructional environment. British Journal of Educational Technology, 41 (6), 146–149. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8535.2010.01115.x .

Benson, V., & Filippaios, F. (2015). Collaborative competencies in professional social networking: Are students short changed by curriculum in business education? Computers in Human Behavior, 51, 1331–1339. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.11.031 .

Benson, V., Saridakis, G., & Tennakoon, H. (2015). Purpose of social networking use and victimisation: Are there any differences between university students and those not in HE? Computers in Human Behavior, 51, 867–872. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.11.034 .

Błachnio, A., Przepiorka, A., Senol-Durak, E., Durak, M., & Sherstyuk, L. (2017). The role of personality traits in Facebook and Internet addictions: A study on Polish, Turkish, and Ukrainian samples. Computers in Human Behavior, 68, 269–275. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.11.037 .

Borrero, D. J., Yousafzai, Y. S., Javed, U., & Page, L. K. (2014). Perceived value of social networking sites (SNS) in students’ expressive participation in social movements. Journal of Research in Interactive Marketing, 8 (1), 56–78. https://doi.org/10.1108/JRIM-03-2013-0015 .

Borrero, J. D., Yousafzai, S. Y., Javed, U., & Page, K. L. (2014). Expressive participation in Internet social movements: Testing the moderating effect of technology readiness and sex on student SNS use. Computers in Human Behavior, 30, 39–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2013.07.032 .

Boyd, D. M., & Ellison, N. B. (2008). Social network sites: Definition, history, and scholarship. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 13 (1), 210–230. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1083-6101.2007.00393.x .

Brailovskaia, J., & Margraf, J. (2017). Facebook Addiction Disorder (FAD) among German students—A longitudinal approach. PLoS ONE, 12 (12), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0189719 .

Brailovskaia, J., Ströse, F., Schillack, H., & Margraf, J. (2020). Less Facebook use—More well-being and a healthier lifestyle? An experimental intervention study. Computers in Human Behavior, 108 (March), 106332. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2020.106332 .

Brailovskaia, J., Teismann, T., & Teismann, T. (2018). Physical activity mediates the association between daily stress and Facebook Addiction Disorder. Computers in Human Behavior, 86, 199–204. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.04.045 .

Busalim, A. H., & Hussin, A. R. C. (2016). Understanding social commerce: A systematic literature review and directions for further research. International Journal of Information Management, 36 (6), 1075–1088. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2016.06.005 .

Cain, J., Scott, D. R., Tiemeier, A. M., Akers, P., & Metzger, A. H. (2013). Social media use by pharmacy faculty: Student friending, e-professionalism, and professional use. Currents in Pharmacy Teaching and Learning, 5 (1), 2–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cptl.2012.09.002 .

Chae, D., Kim, H., & Kim, Y. A. (2017). Sex differences in the factors influencing Korean College Students’ addictive tendency toward social networking sites. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction . https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-017-9778-3 .

Chan, T. K. H., Cheung, C. M. K., & Lee, Z. W. Y. (2017). The state of online impulse-buying research: A literature analysis. Information & Management, 54 (2), 204–217. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2016.06.001 .

Chang, C. W., & Chen, G. M. (2014). College students’ disclosure of location-related information on Facebook. Computers in Human Behavior, 35, 33–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.02.028 .

Chang, C. W., & Heo, J. (2014). Visiting theories that predict college students’ self-disclosure on Facebook. Computers in Human Behavior, 30, 79–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2013.07.059 .

Chen, B., & Marcus, J. (2012). Students’ self-presentation on Facebook: An examination of personality and self-construal factors. Computers in Human Behavior, 28 (6), 2091–2099. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2012.06.013 .

Chen, H. (2017). Antecedents of positive self-disclosure online: An empirical study of US college students Facebook usage. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 10, 147–153. https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S136049 .

Cheung, C. M. K., Chiu, P. Y., & Lee, M. K. O. (2011). Online social networks: Why do students use facebook? Computers in Human Behavior, 27 (4), 1337–1343.

Chung, J. E. (2014). Social networking in online support groups for health: How online social networking benefits patients. Journal of Health Communication, 19 (6), 639–659. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2012.757396 .

Čičević, S., Samčović, A., & Nešić, M. (2016). Exploring college students’ generational differences in Facebook usage. Computers in Human Behavior, 56, 83–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.11.034 .

Clement, J. (2020). Facebook: Number of monthly active users worldwide 2008–2020 Published by J. Clement, Aug 10, 2020 How many users does Facebook have? With over 2.7 billion monthly active users as of the second quarter of 2020, Facebook is the biggest social network world . Retrieved from https://www.statista.com/statistics/264810/number-of-monthly-active-facebook-users-worldwide/

Corbitt-Hall, D. J., Gauthier, J. M., Davis, M. T., & Witte, T. K. (2016). College Students’ responses to suicidal content on social networking sites: An examination using a simulated facebook newsfeed. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 46 (5), 609–624. https://doi.org/10.1111/sltb.12241 .

Deng, L., & Tavares, N. J. (2013). From Moodle to Facebook: Exploring students’ motivation and experiences in online communities. Computers & Education, 68, 167–176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2013.04.028 .

Dindia, K. (1995). Self-disclosure: A sense of balance. Contemporary psychology: A journal of reviews . Vol. 40. New York: Sage Publications. https://doi.org/10.1037/003319 .

Book Google Scholar

Doleck, T., Bazelais, P., & Lemay, D. J. (2017). Examining the antecedents of social networking sites use among CEGEP students. Education and Information Technologies, 22 (5), 2103–2123. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-016-9535-4 .

Eid, M. I. M., & Al-Jabri, I. M. (2016). Social networking, knowledge sharing, and student learning: The case of university students. Computers and Education, 99, 14–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2016.04.007 .

Elphinston, R. A., & Noller, P. (2011). Time to Face It! Facebook intrusion and the implications for romantic jealousy and relationship satisfaction. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 14 (11), 631–635. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2010.0318 .

Enskat, A., Hunt, S. K., & Hooker, J. F. (2017). A generational examination of instructional Facebook use and the effects on perceived instructor immediacy, credibility and student affective learning. Technology, Pedagogy and Education, 26 (5), 545–557. https://doi.org/10.1080/1475939X.2017.1354065 .

Facebook. (2020). Facebook Reports First Quarter 2020 Results . Retrieved from http://investor.fb.com/releasedetail.cfm?ReleaseID=842071 .

Fasae, J. K., & Adegbilero-Iwari, I. (2016). Use of social media by science students in public universities in Southwest Nigeria. The Electronic Library, 34 (2), 213–222. https://doi.org/10.1108/EL-11-2014-0205 .

Gahagan, K., Vaterlaus, J. M., & Frost, L. R. (2016). College student cyberbullying on social networking sites: Conceptualization, prevalence, and perceived bystander responsibility. Computers in Human Behavior, 55, 1097–1105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.11.019 .

George, D. R., Dellasega, C., Whitehead, M. M., & Bordon, A. (2013). Facebook-based stress management resources for first-year medical students: A multi-method evaluation. Computers in Human Behavior, 29 (3), 559–562. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2012.12.008 .

Gettman, H. J., & Cortijo, V. (2015). “Leave Me and My Facebook Alone!” understanding college students’ relationship with Facebook and its use for academic purposes. International Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning Article, 9 (1), 1. https://doi.org/10.20429/ijsotl.2015.090108 .

Ha, L., Joa, C. Y., Gabay, I., & Kim, K. (2018). Does college students’ social media use affect school e-mail avoidance and campus involvement? Internet Research, 28 (1), 213–231. https://doi.org/10.1108/IntR-11-2016-0346 .

Hamid, S., Bukhari, S., Ravana, S. D., Norman, A. A., & Ijab, M. T. (2016). Role of social media in information-seeking behaviour of international students: A systematic literature review. Aslib Journal of Information Management, 68 (5), 643–666. https://doi.org/10.1108/AJIM-03-2016-0031 .

Hamid, S., Waycott, J., Kurnia, S., & Chang, S. (2015). Understanding students’ perceptions of the benefits of online social networking use for teaching and learning. Internet and Higher Education, 26, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2015.02.004 .

Hong, F. Y., & Chiu, S. L. (2016). Factors influencing facebook usage and facebook addictive tendency in university students: The role of online psychological privacy and facebook usage motivation. Stress and Health, 32 (2), 117–127. https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.2585 .

Hossain, M. D., & Veenstra, A. S. (2013). Online maintenance of life domains: Uses of social network sites during graduate education among the US and international students. Computers in Human Behavior, 29 (6), 2697–2702. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2013.07.007 .

Ifinedo, P. (2016). Applying uses and gratifications theory and social influence processes to understand students’ pervasive adoption of social networking sites: Perspectives from the Americas. International Journal of Information Management, 36 (2), 192–206. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2015.11.007 .

Islam, T., Sheikh, Z., Hameed, Z., Khan, I. U., & Azam, R. I. (2018). Social comparison, materialism, and compulsive buying based on stimulus-response- model: A comparative study among adolescents and young adults. Young Consumers, 19 (1), 19–37. https://doi.org/10.1108/MRR-09-2015-0216 .

Josefsson, P., Hrastinski, S., Pargman, D., & Pargman, T. C. (2016). The student, the private and the professional role: Students’ social media use. Education and Information Technologies, 21 (6), 1583–1594. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-015-9403-7 .

Junco, R. (2012). The relationship between frequency of Facebook use, participation in Facebook activities, and student engagement. Computers and Education, 58 (1), 162–171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2011.08.004 .

Junco, R. (2015). Student class standing, Facebook use, and academic performance. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 36, 18–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2014.11.001 .

Karpinski, A. C., Kirschner, P. A., Ozer, I., Mellott, J. A., & Ochwo, P. (2013). An exploration of social networking site use, multitasking, and academic performance among United States and European university students. Computers in Human Behavior, 29 (3), 1182–1192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2012.10.011 .

Kim, J., Lee, C., & Elias, T. (2015). Factors affecting information sharing in social networking sites amongst university students. Online Information Review, 39 (3), 290–309. https://doi.org/10.1108/OIR-01-2015-0022 .

Kim, S., & Yoo, S. J. (2016). Age and gender differences in social networking: effects on south Korean students in higher education. In Social networking and education (pp. 69–82). Switzerland: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-17716-8_5 .

Kim, Y., Sohn, D., & Choi, S. M. (2011). Cultural difference in motivations for using social network sites: A comparative study of American and Korean college students. Computers in Human Behavior, 27 (1), 365–372. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2010.08.015 .

Kircaburun, K., & Griffiths, M. D. (2018). Instagram addiction and the Big Five of personality: The mediating role of self-liking. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 7 (1), 158–170. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.7.2018.15 .

Kırcaburun, K., & Griffiths, M. D. (2018). Problematic Instagram use: The role of perceived feeling of presence and escapism. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction . https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-018-9895-7 .

Kitchenham, B. (2004). Procedures for performing systematic reviews. Keele University, UK and National ICT Australia, 33, 28.

Google Scholar

Kitchenham, B., & Charters, S. (2007). Guidelines for performing systematic literature reviews in software engineering. Keele University and University of Durham, 2, 1051.

Kitsantas, A., Dabbagh, N., Chirinos, D. S., & Fake, H. (2016). College students’ perceptions of positive and negative effects of social networking. In Social networking and education (pp. 225–238). Switzerland: Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-17716-8_14 .

Koc, M., & Gulyagci, S. (2013). Facebook addiction among Turkish College students: The role of psychological health, demographic, and usage characteristics. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 16 (4), 279–284. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2012.0249 .

Kokkinos, C. M., & Saripanidis, I. (2017). A lifestyle exposure perspective of victimization through Facebook among university students. Do individual differences matter? Computers in Human Behavior, 74, 235–245. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.04.036 .

Krasilnikov, A., & Smirnova, A. (2017). Online social adaptation of first-year students and their academic performance. Computers and Education, 113, 327–338. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2017.05.012 .

Kujur, F., & Singh, S. (2017). Engaging customers through online participation in social networking sites. Asia Pacific Management Review, 22 (1), 16–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmrv.2016.10.006 .

Kumar Bhatt, R., & Kumar, A. (2014). Student opinion on the use of social networking tools by libraries. The Electronic Library, 32 (5), 594–602. https://doi.org/10.1108/EL-09-2012-0110 .

Kuo, T., & Tang, H. L. (2014). Relationships among personality traits, Facebook usages, and leisure activities—A case of Taiwanese college students. Computers in Human Behavior, 31 (1), 13–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2013.10.019 .

Lambić, D. (2016). Correlation between Facebook use for educational purposes and academic performance of students. Computers in Human Behavior, 61, 313–320. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.03.052 .

Lee, S. (2015). Analyzing negative SNS behaviors of elementary and middle school students in Korea. Computers in Human Behavior, 43, 15–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.10.014 .

Lim, J., & Richardson, J. C. (2016). Exploring the effects of students’ social networking experience on social presence and perceptions of using SNSs for educational purposes. The Internet and Higher Education, 29, 31–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2015.12.001 .

Lin, W.-Y., Zhang, X., Song, H., & Omori, K. (2016). Health information seeking in the Web 2.0 age: Trust in social media, uncertainty reduction, and self-disclosure. Computers in Human Behavior, 56, 289–294. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.11.055 .

Liu, C. C., Chen, Y. C., & Diana Tai, S. J. (2017). A social network analysis on elementary student engagement in the networked creation community. Computers and Education, 115 (300), 114–125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2017.08.002 .

Liu, D., & Brown, B. B. (2014). Self-disclosure on social networking sites, positive feedback, and social capital among Chinese college students. Computers in Human Behavior, 38, 213–219. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.06.003 .

Luqman, A., Cao, X., Ali, A., Masood, A., & Yu, L. (2017). Empirical investigation of Facebook discontinues usage intentions based on SOR paradigm. Computers in Human Behavior, 70, 544–555. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.01.020 .

Mano, R. S. (2014). Social media and online health services: A health empowerment perspective to online health information. Computers in Human Behavior, 39, 404–412. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.07.032 .

Mazman, S. G., & Usluel, Y. K. (2010). Modeling educational usage of Facebook. Computers and Education, 55 (2), 444–453. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2010.02.008 .

Mehrabian, A., & Russell, J. A. (1974). An approach to environmental psychology . Cambridge: The MIT Press.

Meier, A., Reinecke, L., & Meltzer, C. E. (2016). Facebocrastination? Predictors of using Facebook for procrastination and its effects on students’ well-being. Computers in Human Behavior, 64, 65–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.06.011 .

Mirabolghasemi, M., Iahad, N. A., & Rahim, N. Z. A. (2016). Students’ perception towards the potential and barriers of social network sites in higher education. In Social networking and education (pp. 41–49). Switzerland: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-17716-8_3 .

Moghavvemi, S., Paramanathan, T., Rahin, N. M., & Sharabati, M. (2017). Student’s perceptions towards using e-learning via Facebook. Behaviour and Information Technology, 36 (10), 1081–1100. https://doi.org/10.1080/0144929X.2017.1347201 .

Moghavvemi, S., Sharabati, M., Paramanathan, T., & Rahin, N. M. (2017). The impact of perceived enjoyment, perceived reciprocal benefits and knowledge power on students’ knowledge sharing through Facebook. International Journal of Management Education, 15 (1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijme.2016.11.002 .

Mostafa, R. B. (2015). Engaging students via social media: Is it worth the effort? Journal of Marketing Education, 37 (3), 144–159. https://doi.org/10.1177/0273475315585825 .

Nawi, N. B. C., Al Mamun, A., Nasir, N. A. B. M., Shokery, N. B., Raston, N. B. A., & Fazal, S. A. (2017). Acceptance and usage of social media as a platform among student entrepreneurs. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 24 (2), 375–393. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSBED-09-2016-0136 .

Ndasauka, Y., Hou, J., Wang, Y., Yang, L., Yang, Z., Ye, Z., et al. (2016). Excessive use of Twitter among college students in the UK: Validation of the Microblog Excessive Use Scale and relationship to social interaction and loneliness. Computers in Human Behavior, 55, 963–971. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.10.020 .

Nwagwu, W. E. (2017). Social networking, identity and sexual behaviour of undergraduate students in Nigerian universities. The Electronic Library, 35 (3), 534–558. https://doi.org/10.1108/EL-01-2015-0014 .

Pantic, I. (2014). Online social networking and mental health. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 17 (10), 652–657. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2014.0070 .

Parboteeah, D. V., Valacich, J. S., & Wells, J. D. (2009). The influence of website characteristics on a consumer’s urge to buy impulsively. Information Systems Research, 20 (1), 60–78. https://doi.org/10.1287/isre.1070.0157 .

Park, N., Song, H., & Lee, K. M. (2014). Social networking sites and other media use, acculturation stress, and psychological well-being among East Asian college students in the United States. Computers in Human Behavior, 36, 138–146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.03.037 .

Park, S. Y., Cha, S.-B., Lim, K., & Jung, S.-H. (2014). The relationship between university student learning outcomes and participation in social network services, social acceptance and attitude towards school life. British Journal of Educational Technology, 45 (1), 97–111. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12013 .

Paul, J. A., Baker, H. M., & Cochran, J. D. (2012). Effect of online social networking on student academic performance. Computers in Human Behavior, 28 (6), 2117–2127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2012.06.016 .

Peters, A. N., Winschiers-Theophilus, H., & Mennecke, B. E. (2015). Cultural influences on Facebook practices: A comparative study of college students in Namibia and the United States. Computers in Human Behavior, 49, 259–271. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.02.065 .

Ponnusamy, S., Iranmanesh, M., Foroughi, B., & Hyun, S. S. (2020). Drivers and outcomes of Instagram addiction: Psychological well-being as moderator. Computers in Human Behavior, 107, 106294. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2020.106294 .

Rap, S., & Blonder, R. (2017). Thou shall not try to speak in the Facebook language: Students’ perspectives regarding using Facebook for chemistry learning. Computers and Education, 114, 69–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2017.06.014 .

Raymond, J., & Wang, H. (2015). Social network sites and international students ’ cross-cultural adaptation. Computers in Human Behavior, 49, 400–411. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.03.041 .

Roblyer, M. D., McDaniel, M., Webb, M., Herman, J., & Witty, J. V. (2010). Findings on Facebook in higher education: A comparison of college faculty and student uses and perceptions of social networking sites. Internet and Higher Education, 13 (3), 134–140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2010.03.002 .

Romero-Hall, E. (2017). Posting, sharing, networking, and connecting: Use of social media content by graduate students. TechTrends, 61 (6), 580–588. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11528-017-0173-5 .

Rui, J. R., & Wang, H. (2015). Social network sites and international students’ cross-cultural adaptation. Computers in Human Behavior, 49, 400–411. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.03.041 .

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation. Social Development, and Well-Being, 55 (1), 68–78.

Ryan, T., Chester, A., Reece, J., & Xenos, S. (2014). The uses and abuses of Facebook: A review of Facebook addiction. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 3 (3), 133–148. https://doi.org/10.1556/JBA.3.2014.016 .

Serdyukov, P. (2017). Innovation in education: What works, what doesn’t, and what to do about it? Journal of Research in Innovative Teaching & Learning, 10 (1), 4–33. https://doi.org/10.1108/jrit-10-2016-0007 .

Sheeran, N., & Cummings, D. J. (2018). An examination of the relationship between Facebook groups attached to university courses and student engagement. Higher Education, 76, 937–955.

Shettar, M., Karkal, R., Kakunje, A., Mendonsa, R. D., & Chandran, V. V. M. (2017). Facebook addiction and loneliness in the post-graduate students of a university in southern India. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 63 (4), 325–329. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764017705895 .

Shim, M., Lee-Won, R. J., & Park, S. H. (2016). The self on the Net: The joint effect of self-construal and public self-consciousness on positive self-presentation in online social networking among South Korean college students. Computers in Human Behavior, 63, 530–539. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.05.054 .

Sin, S. C. J., & Kim, K. S. (2013). International students’ everyday life information seeking: The informational value of social networking sites. Library and Information Science Research, 35 (2), 107–116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lisr.2012.11.006 .

Singh, A. (2017). Mining of social media data of University students. Education and Information Technologies, 22 (4), 1515–1526. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-016-9501-1 .

Skues, J. L., Williams, B., & Wise, L. (2012). The effects of personality traits, self-esteem, loneliness, and narcissism on Facebook use among university students. Computers in Human Behavior, 28 (6), 2414–2419. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2012.07.012 .

Smith, R., Morgan, J., & Monks, C. (2017). Students’ perceptions of the effect of social media ostracism on wellbeing. Computers in Human Behavior, 68, 276–285. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.11.041 .

Special, W. P., & Li-Barber, K. T. (2012). Self-disclosure and student satisfaction with Facebook. Computers in Human Behavior, 28 (2), 624–630. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2011.11.008 .

Tally, S. (2010). Mixable blends Facebook with academics to improve student success . Purdue: Purdue University News.

Tandoc, E. C., Ferrucci, P., & Duffy, M. (2015). Facebook use, envy, and depression among college students: Is facebooking depressing? Computers in Human Behavior, 43, 139–146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.10.053 .