What roles Co-author and Corresponding Author play in Research Papers

Introduction

In current academic research, nothing exists in isolation. Good research requires collaboration, thus giving rise to the guild of co-authors and corresponding authors. These terms often raise questions about their significance and differences. Let’s delve into the distinctions between co-authors and corresponding authors, their roles, and how to appropriately mention the corresponding author in a paper.

Co-author vs. Corresponding Author: Unveiling the Differences

Co-author Meaning

- A co-author is a researcher who has contributed significantly to a research paper, sharing responsibility for its content and findings.

- Co-authors collaborate to design experiments, analyze results, and contribute to the overall intellectual content of the paper.

Corresponding Author Meaning

- The corresponding author is the designated point of contact for the paper. They facilitate communication with the journal, handle revisions, and address queries.

- The corresponding author isn’t necessarily the primary contributor but takes on administrative responsibilities.

How to Mention the Corresponding Author in a Paper

- Typically, the corresponding author’s name and contact information are provided at the top of the first page of the paper.

- Including an asterisk (*) next to the corresponding author’s name and explaining their role in a footnote is common practice.

- Mention the corresponding author’s email address for efficient communication.

Co-author vs. Second Author: Clarifying the Distinction

- Co-author: Holds equal responsibility for the content contributed substantially.

- Second Author: Holds a significant role but might not have been as involved as co-authors.

Who Should Be the Corresponding Author?

- Usually, the corresponding author is a senior researcher who can effectively handle communication.

- The corresponding author need not be the primary author; any co-author familiar with the research can take on this role.

Differences Between Co-author and Corresponding Author

- Responsibility : Co-authors share content responsibility; the corresponding author manages communication.

- Involvement : Co-authors are deeply involved in research; the corresponding author handles administrative aspects.

- Listing : All co-authors are listed in the byline; only the corresponding author’s contact details are visible.

- Primary Contribution : Co-authors contribute intellectually; the corresponding author manages logistics.

Main Author vs. Corresponding Author: Unraveling the Contrast

- Main Author : Often referred to as the first author, contributes significantly to research and writing.

- Corresponding Author : Handles communication, edits, and revisions after accepting the paper.

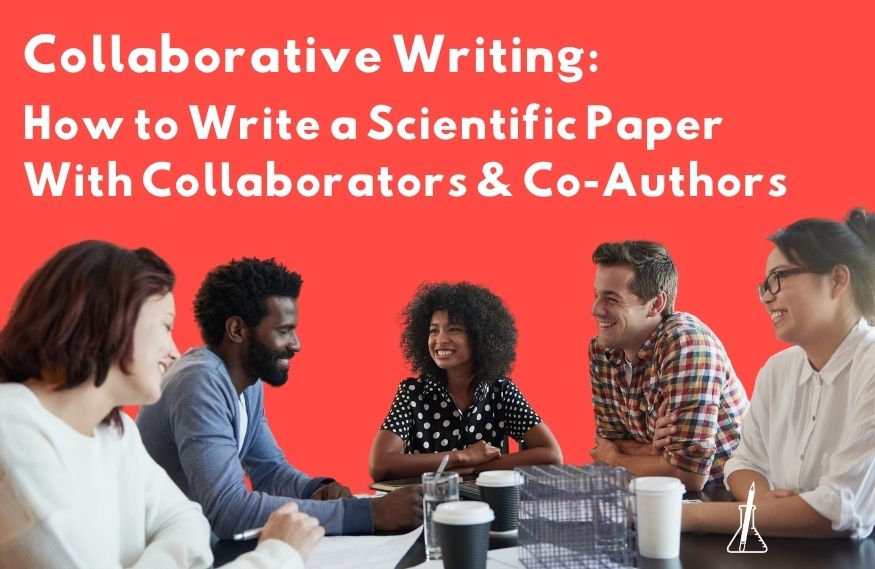

Collaborative Writing: Can Two Authors Pen a Book Together?

- Multiple authors can co-write a book, combining their expertise and perspectives.

The Merits of Being a Co-author

- Learning Opportunity : Co-authoring exposes you to diverse ideas and research methods.

- Networking : Collaboration connects you with other researchers in your field.

- Shared Workload : Co-authors distribute the research and writing burden.

Conclusion: Navigating the Authorship Landscape

Understanding the roles of co-authors and corresponding authors is vital in the intricate realm of academic authorship. Collaborative efforts enrich research and foster academic growth. As you embark on research journeys, remember the unique contributions of co-authors and the crucial responsibilities shouldered by corresponding authors. So, cheer up if you are a co-author or corresponding author; your contributions to this evolving knowledge domain are unparalleled.

Explore, Collaborate, and Illuminate. Connect with us at Manuscriptedit.com .

Related Posts

How to find funding for research.

Research is an essential aspect of scientific advancement. It requires time, resources, and funding to carry out experiments, collect data, and analyze results. However, finding funding for research can be challenging, especially for early-career researchers or those working in underfunded fields. In this blog, we will discuss some ways to find funding for your research. […]

The Process of Publishing a Research paper in a Journal

The publication of a research paper in a journal is a long and painstaking process. It involves many stages that need to be completed at the author’s end before submission to a journal. After submission, there are further steps at the publisher’s end over which the author has no control. In order to get a […]

Avoiding rejection of your paper due to Language Errors

Nowadays, it is relatively normal for a paper to get rejected. Every researcher has experienced manuscript rejection in their career at some point. But it’s somewhat demotivating considering the amount of time and effort that has gone behind it, starting from the whole research process to writing and formatting. There are various reasons for the […]

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Loading metrics

Open Access

Ten simple rules for collaboratively writing a multi-authored paper

* E-mail: [email protected]

¶ ‡ MAF is the lead author. All authors contributed equally to this work. Besides for MAF, author order was computed randomly.

Affiliation Australian Rivers Institute, Griffith University, Nathan, Queensland, Australia

Affiliation Department of Ecology and Environmental Science, Umeå University, Umeå, Sweden

Affiliation Marine Institute, Furnace, Newport, Co. Mayo, Ireland

Affiliation Center for Environmental Research, Education and Outreach, Washington State University, Pullman, Washington, United States of America

Affiliation UFZ, Helmholtz Centre for Environmental Research, Department of Lake Research, Magdeburg, Germany

Affiliation Department of Biology, York University, Toronto, Ontario, Canada

Affiliation Department of Biology, Pomona College, Claremont, California, United States of America

Affiliation Department of Ecology and Genetics/Limnology, Uppsala University, Uppsala, Sweden

Affiliation Department of Geography, Geology, and the Environment, Illinois State University, Normal, Illinois, United States of America

Affiliation Department of Biological Sciences, Virginia Tech, Blacksburg, Virginia, United States of America

Affiliation Catalan Institute for Water Research (ICRA), Girona, Spain

- Marieke A. Frassl,

- David P. Hamilton,

- Blaize A. Denfeld,

- Elvira de Eyto,

- Stephanie E. Hampton,

- Philipp S. Keller,

- Sapna Sharma,

- Abigail S. L. Lewis,

- Gesa A. Weyhenmeyer,

Published: November 15, 2018

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1006508

- Reader Comments

Citation: Frassl MA, Hamilton DP, Denfeld BA, de Eyto E, Hampton SE, Keller PS, et al. (2018) Ten simple rules for collaboratively writing a multi-authored paper. PLoS Comput Biol 14(11): e1006508. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1006508

Editor: Fran Lewitter, Whitehead Institute, UNITED STATES

Copyright: © 2018 Frassl et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Funding: This work was supported by the Global Lake Ecological Observatory Network (GLEON; www.gleon.org ). ML and PK received the GLEON student travel fund. GW was supported by the Swedish Research Council, Grant No. 2016-04153. NC had the support of the Beatriu de Pinós postdoctoral programme (BP-2016-00215). PK was supported by the DFG (Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, grant SP 1570/1-1). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Introduction

Science is increasingly done in large teams [ 1 ], making it more likely that papers will be written by several authors from different institutes, disciplines, and cultural backgrounds. A small number of “Ten simple rules” papers have been written on collaboration [ 2 , 3 ] and on writing [ 4 , 5 ] but not on combining the two. Collaborative writing with multiple authors has additional challenges, including varied levels of engagement of coauthors, provision of fair credit through authorship or acknowledgements, acceptance of a diversity of work styles, and the need for clear communication. Miscommunication, a lack of leadership, and inappropriate tools or writing approaches can lead to frustration, delay of publication, or even the termination of a project.

To provide insight into collaborative writing, we use our experience from the Global Lake Ecological Observatory Network (GLEON) [ 6 ] to frame 10 simple rules for collaboratively writing a multi-authored paper. We consider a collaborative multi-authored paper to have three or more people from at least two different institutions. A multi-authored paper can be a result of a single discrete research project or the outcome of a larger research program that includes other papers based on common data or methods. The writing of a multi-authored paper is embedded within a broader context of planning and collaboration among team members. Our recommended rules include elements of both the planning and writing of a paper, and they can be iterative, although we have listed them in numerical order. It will help to revisit the rules frequently throughout the writing process. With the 10 rules outlined below, we aim to provide a foundation for writing multi-authored papers and conducting exciting and influential science.

Rule 1: Build your writing team wisely

The writing team is formed at the beginning of the writing process. This can happen at different stages of a research project. Your writing team should be built upon the expertise and interest of your coauthors. A good way to start is to review the initial goal of the research project and to gather everyone’s expectations for the paper, allowing all team members to decide whether they want to be involved in the writing. This step is normally initiated by the research project leader(s). When appointing the writing team, ensure that the team has the collective expertise required to write the paper and stay open to bringing in new people if required. If you need to add a coauthor at a later stage, discuss this first with the team ( Rule 8 ) and be clear as to how the person can contribute to the paper and qualify as a coauthor (Rules 4 and 10 ). When in doubt about selecting coauthors, in general we suggest to opt for being inclusive. A shared list with contact information and the contribution of all active coauthors is useful for keeping track of who is involved throughout the writing process.

In order to share the workload and increase the involvement of all coauthors during the writing process, you can distribute specific roles within the team (e.g., a team leader and a facilitator [see Rule 2 ] and a note taker [see Rule 8 ]).

Rule 2: If you take the lead, provide leadership

Leadership is critical for a multi-authored paper to be written in a timely and satisfactory manner. This is especially true for large, joint projects. The leader of the writing process and first author typically are the same person, but they don’t have to be. The leader is the contact person for the group, keeps the writing moving forward, and generally should manage the writing process through to publication. It is key that the leader provides strong communication and feedback and acknowledges contributions from the group. The leader should incorporate flexibility with respect to timelines and group decisions. For different leadership styles, refer to [ 7 , 8 ].

When developing collaborative multi-authored papers, the leader should allow time for all voices to be heard. In general, we recommend leading multi-authored papers through consensus building and not hierarchically because the manuscript should represent the views of all authors ( Rule 9 ). At the same time, the leader needs to be able to make difficult decisions about manuscript structure, content, and author contributions by maintaining oversight of the project as a whole.

Finally, a good leader must know when to delegate tasks and share the workload, e.g., by delegating facilitators for a meeting or assigning responsibilities and subleaders for sections of a manuscript. At times, this may include recognizing that something has changed, e.g., a change in work commitments by a coauthor or a shift in the paper’s focus. In such a case, it may be timely for someone else to step in as leader and possibly also as first author, while the previous leader’s work is acknowledged in the manuscript or as a coauthor ( Rule 4 ).

Rule 3: Create a data management plan

If not already implemented at the start of the research project, we recommend that you implement a data management plan (DMP) that is circulated at an early stage of the writing process and agreed upon by all coauthors (see also [ 9 ] and https://dmptool.org/ ; https://dmponline.dcc.ac.uk/ ). The DMP should outline how project data will be shared, versioned, stored, and curated and also details of who within the team will have access to the (raw) data during and post publication.

Multi-authored papers often use and/or produce large datasets originating from a variety of sources or data contributors. Each of these sources may have different demands about how data and code are used and shared during analysis and writing and after publication. Previous articles published in the “Ten simple rules” series provide guidance on the ethics of big-data research [ 10 ], how to enable multi-site collaborations through open data sharing [ 3 ], how to store data [ 11 ], and how to curate data [ 12 ]. As many journals now require datasets to be shared through an open access platform as a prerequisite to paper publication, the DMP should include detail on how this will be achieved and what data (including metadata) will be included in the final dataset.

Your DMP should not be a complicated, detailed document and can often be summarized in a couple of paragraphs. Once your DMP is finalized, all data providers and coauthors should confirm that they agree with the plan and that their institutional and/or funding agency obligations are met. It is our experience within GLEON that these obligations vary widely across the research community, particularly at an intercontinental scale.

Rule 4: Jointly decide on authorship guidelines

Defining authorship and author order are longstanding issues in science [ 13 ]. In order to avoid conflict, you should be clear early on in the research project what level of participation is required for authorship. You can do this by creating a set of guidelines to define the contributions and tasks worthy of authorship. For an authorship policy template, see [ 14 ] and check your institute’s and the journal’s authorship guidelines. For example, generating ideas, funding acquisition, data collection or provision, analyses, drafting figures and tables, and writing sections of text are discrete tasks that can constitute contributions for authorship (see, e.g., the CRediT system: http://docs.casrai.org/CRediT [ 15 ]). All authors are expected to participate in multiple tasks, in addition to editing and approving the final document. It is debated whether merely providing data does qualify for coauthorship. If data provision is not felt to be grounds for coauthorship, you should acknowledge the data provider in the Acknowledgments [ 16 ].

Your authorship guidelines can also increase transparency and help to clarify author order. If coauthors have contributed to the paper at different levels, task-tracking and indicating author activity on various tasks can help establish author order, with the person who contributed most in the front. Other options include groupings based on level of activity [ 17 ] or having the core group in the front and all other authors listed alphabetically. If every coauthor contributed equally, you can use alphabetical order [ 18 ] or randomly assigned order [ 19 ]. Joint first authorship should be considered when appropriate. We encourage you to make a statement about author order (e.g., [ 19 ]) and to generate authorship attribution statements; many journals will include these as part of the Acknowledgments if a separate statement is not formally required. For those who do not meet expectations for authorship, an alternative to authorship is to list contributors in the Acknowledgments [ 15 ]. Be aware of coauthors’ expectations and disciplinary, cultural, and other norms in what constitutes author order. For example, in some disciplines, the last author is used to indicate the academic advisor or team leader. We recommend revisiting definitions of authorship and author order frequently because roles and responsibilities may change during the writing process.

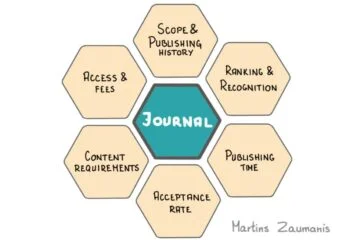

Rule 5: Decide on a writing strategy

The writing strategy should be adapted according to the needs of the team (white shapes in Fig 1 ) and based on the framework given through external factors (gray shapes in Fig 1 ). For example, a research paper that uses wide-ranging data might have several coauthors but one principal writer (e.g., a PhD candidate) who was conducting the analysis, whereas a comment or review in a specific research field might be written jointly by all coauthors based on parallel discussion. In most cases, the approach that everyone writes on everything is not possible and is very inefficient. Most commonly, the paper is split into sub-sections based on what aspects of the research the coauthors have been responsible for or based on expertise and interest of the coauthors. Regardless of which writing strategy you choose, the importance of engaging all team members in defining the narrative, format, and structure of the paper cannot be overstated; this will preempt having to rewrite or delete sections later.

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

Different writing strategies ranging from very inclusive to minimally inclusive: group writing = everyone writes on everything; subgroup writing = document is split up into expertise areas, each individual contributes to a subsection; core writing group = a subgroup of a few coauthors writes the paper; scribe writing = one person writes based on previous group discussions; principal writer = one person drafts and writes the paper (writing styles adapted from [ 20 ]). Which writing strategy you choose depends on external factors (filled, gray shapes), such as the interdisciplinarity of the study or the time pressure of the paper to be published, and affects the payback (dashed, white shapes). An increasing height of the shape indicates an increasing quantity of the decision criteria, such as the interdisciplinarity, diversity, feasibility, etc.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1006508.g001

For an efficient writing process, try to use the active voice in suggestions and make direct edits rather than simply stating that a section needs revision. For all writing strategies, the lead author(s) has to ensure that the completed text is cohesive.

Rule 6: Choose digital tools to suit your needs

A suitable technology for writing your multi-authored paper depends upon your chosen writing approach ( Rule 5 ). For projects in which the whole group writes together, synchronous technologies such as Google Docs or Overleaf work well by allowing for interactive writing that facilitates version control (see also [ 21 ]). In contrast, papers written sequentially, in parallel by subsections, or by only one author may allow for using conventional programs such as Microsoft Word or LibreOffice. In any case, you should create a plan early on for version control, comments, and tracking changes. Regularly mark the version of the document, e.g., by including the current date in the file name. When working offline and distributing the document, add initials in the file name to indicate the progress and most recent editor.

High-quality communication is important for efficient discussion on the paper’s content. When picking a virtual meeting technology, consider the number of participants permitted in a single group call, ability to record the meeting, audio and visual quality, and the need for additional features such as screencasting or real-time notes. Especially for large groups, it can be helpful for people who are not currently speaking to mute their microphones (blocking background noise), to use the video for nonverbal communication (e.g., to show approval or rejection and to help nonnative speakers), or to switch off the video when internet speeds are slow. More guidelines for effective virtual meetings are available in Hampton and colleagues [ 22 ].

In between virtual meetings, virtual technologies can help to streamline communication (e.g., https://slack.com ) and can facilitate the writing process through shared to-do lists and task boards including calendar features (e.g., http://trello.com ).

With all technologies, accessibility, ease of use, and cost are important decision criteria. Note that some coauthors will be very comfortable with new technologies, whereas others may not be. Both should be ready to compromise in order to be as efficient and inclusive as possible. Basic training in unfamiliar technologies will likely pay off in the long term.

Rule 7: Set clear timelines and adhere to them

As for the overall research project, setting realistic and effective deadlines maintains the group’s momentum and facilitates on-schedule paper completion [ 23 ]. Before deciding to become a coauthor, consider your own time commitments. As a coauthor, commit to set deadlines, recognize the importance of meeting them, and notify the group early on if you realize that you will not be able to meet a deadline or attend a meeting. Building consensus around deadlines will ensure that internally imposed deadlines are reasonably timed [ 23 ] and will increase the likelihood that they are met. Keeping to deadlines and staying on task require developing a positive culture of encouragement within the team [ 14 ]. You should respect people’s time by being punctual for meetings, sending out drafts and the meeting agenda on schedule, and ending meetings on time.

To develop a timeline, we recommend starting by defining the “final” deadline. Occasionally, this date will be set “externally” (e.g., by an editorial request), but in most cases, you can set an internal consensus deadline. Thereafter, define intermediate milestones with clearly defined tasks and the time required to fulfill them. Look for and prioritize strategies that allow multiple tasks to be completed simultaneously because this allows for a more efficient timeline. Keep in mind that “however long you give yourself to complete a task is how long it will take” [ 24 ] and that group scheduling will vary depending on the selected writing strategy ( Rule 5 ). Generally, collaborative manuscripts need more draft and revision rounds than a “solo” article.

Rule 8: Be transparent throughout the process

This rule is important for the overall research project but becomes especially important when it comes to publishing and coauthorship. Being as open as possible about deadlines ( Rule 7 ) and expectations (including authorship, Rule 4 ) helps to avoid misunderstandings and conflict. Be clear about the consequences if someone does not follow the group’s rules but also be open to rediscuss rules if needed. Potential consequences of not following the group’s rules include a change in author order or removing authorship. It should also be clear that a coauthor’s edits might not be included in the final text if s/he does not contribute on time. Bad experience from past collaboration can lead to exclusion from further research projects.

As for collaboration [ 2 ], communication is key. During meetings, decide on a note taker who keeps track of the group’s discussions and decisions in meeting notes. This will help coauthors who could not attend the meeting as well as help the whole group follow up on decisions later on. Encourage everyone to provide feedback and be sincere and clear if something is not working—writing a multi-authored paper is a learning process. If you feel someone is frustrated, try to address the issue promptly within the group rather than waiting and letting the problem escalate. When resolving a conflict, it is important to actively listen and focus the conversation on how to reach a solution that benefits the group as a whole [ 25 ]. Democratic decisions can often help to resolve differing opinions.

Rule 9: Cultivate equity, diversity, and inclusion

Multi-authored papers will likely have a team of coauthors with diverse demographics and cultural values, which usually broadens the scope of knowledge, experience, and background. While the benefit of a diverse team is clear [ 14 ], successfully integrating diversity in a collaborative team effort requires increased awareness of differences and proactive conflict management [ 25 ]. You can cultivate diversity by holding members accountable to equity, diversity, and inclusivity guidelines (e.g., https://www.ryerson.ca/edistem/ ).

If working across cultures, you will need to select the working language (both for verbal and written communications); this is most commonly the publication language. When team members are not native speakers in the working language, you should always speak slowly, enunciate clearly, and avoid local expressions and acronyms, as well as listen closely and ask questions if you do not understand. Besides language, be empathetic when listening to others’ opinions in order to genuinely understand your coauthors’ points of view [ 26 ].

When giving verbal or written feedback, be constructive but also be aware of how different cultures receive and react to feedback [ 27 ]. Inclusive writing and speaking provide engagement, e.g., “ we could do that,” and acknowledge input between peers. In addition, you can create opportunities for expression of different personalities and opinions by adopting a participatory group model (e.g., [ 28 ]).

Rule 10: Consider the ethical implications of your coauthorship

Being a coauthor is both a benefit and a responsibility: having your name on a publication implies that you have contributed substantially, that you are familiar with the content of the paper, and that you have checked the accuracy of the content as best you can. To conduct a self-assessment as to whether your contributions merit coauthorship, start by revisiting authorship guidelines for your group ( Rule 4 ).

Be sure to verify the scientific accuracy of your contributions; e.g., if you contributed data, it is your responsibility that the data are correct, or if you performed laboratory or data analyses, it is your responsibility that the analyses are correct. If an author is accused of scientific misconduct, there are likely to be consequences for all the coauthors. Although there are currently no clear rules for coauthor responsibility [ 29 ], be aware of your responsibility and find a balance between trust and control.

One of the final steps before submission of a multi-authored paper is for all coauthors to confirm that they have contributed to the paper, agree upon the final text, and support its submission. This final confirmation, initiated by the lead author, will ensure that all coauthors have considered their role in the work and can affirm contributions. It is important that you repeat the confirmation step each time the paper is revised and resubmitted. Set deadlines for the confirmation steps and make clear that coauthorship cannot be guaranteed if confirmations are not done.

When writing collaborative multi-authored papers, communication is more complex, and consensus can be more difficult to achieve. Our experience shows that structured approaches can help to promote optimal solutions and resolve problems around authorship as well as data ownership and curation. Clear structures are vital to establish a safe and positive environment that generates trust and confidence among the coauthors [ 14 ]. The latter is especially challenging when collaborating over large distances and not meeting face-to-face.

Since there is no single “right approach,” our rules can serve as a starting point that can be modified specifically to your own team and project needs. You should revisit these rules frequently and progressively adapt what works best for your team and the project.

We believe that the benefits of working in diverse groups outweigh the transaction costs of coordinating many people, resulting in greater diversity of approaches, novel scientific outputs, and ultimately better papers. If you bring curiosity, patience, and openness to team science projects and act with consideration and empathy, especially when writing, the experience will be fun, productive, and rewarding.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Meredith Holgerson and Samantha Oliver for their input in the very beginning of this project. We thank the Global Lake Observatory Network (GLEON), which has provided a trustworthy and collaborative work environment.

- View Article

- PubMed/NCBI

- Google Scholar

- 7. Bass BM, Avolio BJ. Improving Organizational Effectiveness Through Transformational Leadership. 1st ed. London: SAGE Publications; 1994.

- 8. Braun S, Peus C, Frey D, Knipfer K. Leadership in Academia: Individual and Collective Approaches to the Quest for Creativity and Innovation. In: Peus C, Braun S, Schyns B, editors. Leadership Lessons from Compelling Contexts: Emerald Group Publishing Limited; 2016. pp. 349–365.

- 24. Northcote Parkinson C. Parkinson’s Law: Or the Pursuit of Progress. 1st ed. London: John Murray; 1958.

- 25. Bennett LM, Gadlin H, Levine-Finley S. Collaboration & Team Science: A Field Guide. National Institutes of Health. August 2010. https://ccrod.cancer.gov/confluence/display/NIHOMBUD/Home . [cited 19 February 2018].

- 26. Covey SR. The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People: Powerful Lessons in Personal Change. London: Simon & Schuster; 2004.

- 27. Meyer E. The Culture Map (INTL ED): Decoding How People Think, Lead, and Get Things Done Across Cultures. 1st ed. New York: PublicAffairs; 2016.

- 28. Kaner S. Facilitator’s guide to participatory decision-making. 1st ed. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2014.

Defining authorship in your research paper

Co-authors, corresponding authors, and affiliations, quick links, why does authorship matter.

Authorship gives credit and implies accountability for published work, so there are academic, social and financial implications.

It is very important to make sure people who have contributed to a paper, are given credit as authors. And also that people who are recognized as authors, understand their responsibility and accountability for what is being published.

There are a couple of types of authorship to be aware of.

Co-author Any person who has made a significant contribution to a journal article. They also share responsibility and accountability for the results of the published research.

Corresponding author If more than one author writes an article, you’ll choose one person to be the corresponding author. This person will handle all correspondence about the article and sign the publishing agreement on behalf of all the authors. They are responsible for ensuring that all the authors’ contact details are correct, and agree on the order that their names will appear in the article. The authors also will need to make sure that affiliations are correct, as explained in more detail below.

Open access publishing

There is increasing pressure on researchers to show the societal impact of their research.

Open access can help your work reach new readers, beyond those with easy access to a research library.

How common is co-authorship and what are the challenges collaborating authors face? Our white paper Co-authorship in the Humanities and Social Sciences: A global view explores the experiences of 894 researchers from 62 countries.

If you are a named co-author, this means that you:

Made a significant contribution to the work reported. That could be in the conception, study design, execution, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation, or in all these areas.

Have drafted or written, substantially revised or critically reviewed the article.

Have agreed on the journal to which the article will be submitted.

Reviewed and agreed on all versions of the article before submission, during revision, the final version accepted for publication, and any significant changes introduced at the proofing stage.

Agree to take responsibility and be accountable for the contents of the article. Share responsibility to resolve any questions raised about the accuracy or integrity of the published work.

Every submission to our medical and health science journals should comply with the International Committee on Medical Journal Ethics’ definition of authorship .

Please include any other form of specific personal contribution in the acknowledgments section of your paper.

Affiliations: get it right

Your affiliation in the manuscript should be the institution where you conducted the research. You should also include details of any funding received from that institution.

If you have changed affiliation since completing the research, your new affiliation can be acknowledged in a note. We can’t normally make changes to affiliation after the journal accepts your article.

Changes to authorship

Authorship changes post-submission should only be made in exceptional circumstances, and any requests for authors to be removed or added must be in line with our authorship criteria.

If you need to make an authorship change, you will need to contact the Journal Editorial Office or Editorial team in the first instance. You will be asked to complete our Authorship Change request form ; all authors (including those you are adding or removing) must sign this form. This will be reviewed by the Editor (and in some instances, the publisher).

Please note any authorship change is at the Editor’s discretion; they have the right to refuse any authorship change they do not believe conforms with our authorship policies.

Some T&F journals do not allow any authorship changes post-submission; where this is applicable, this will be clearly indicated on the journal homepage or on the ‘instructions for authors’ page.

If the corresponding author changes before the article is published (for example, if a co-author becomes the corresponding author), you will need to write to the editor of the journal and the production editor. You will need to confirm to them that both authors have agreed the change.

Requested changes to the co-authors or corresponding authors following publication of the article may be considered, in line with the authorship guidelines issued by COPE , the Committee on Publication Ethics. Please see our corrections policy for more details. Any requests for changes must be made by submitting the completed Authorship Change Request form .

Authorship Change Request form

Important: agree on your corresponding author and the order of co-authors, and check all affiliations and contact details before submitting.

Taylor & Francis Editorial Policies on Authorship

The following instructions (part of our Editorial Policies ) apply to all Taylor & Francis Group journals.

Corresponding author

Co-authors must agree on who will take on the role of corresponding author. It is then the responsibility of the corresponding author to reach consensus with all co-authors regarding all aspects of the article, prior to submission. This includes the authorship list and order, and list of correct affiliations.

The corresponding author is also responsible for liaising with co-authors regarding any editorial queries. And, they act on behalf of all co-authors in any communication about the article throughout: submission, peer review, production, and after publication. The corresponding author signs the publishing agreement on behalf of all the listed authors.

AI-based tools and technologies for content generation

Authors must be aware that using AI-based tools and technologies for article content generation, e.g. large language models (LLMs), generative AI, and chatbots (e.g. ChatGPT), is not in line with our authorship criteria.

All authors are wholly responsible for the originality, validity and integrity of the content of their submissions. Therefore, LLMs and other similar types of tools do not meet the criteria for authorship.

Where AI tools are used in content generation, they must be acknowledged and documented appropriately in the authored work.

Changes in authorship

Any changes in authorship prior to or after publication must be agreed upon by all authors – including those authors being added or removed. It is the responsibility of the corresponding author to obtain confirmation from all co-authors and to provide a completed Authorship Change Request form to the editorial office.

If a change in authorship is necessary after publication, this will be amended via a post-publication notice. Any changes in authorship must comply with our criteria for authorship. And requests for significant changes to the authorship list, after the article has been accepted, may be rejected if clear reasons and evidence of author contributions cannot be provided.

Assistance from scientific, medical, technical writers or translators

Contributions made by professional scientific, medical or technical writers, translators or anyone who has assisted with the manuscript content, must be acknowledged. Their source of funding must also be declared.

They should be included in an ‘Acknowledgments’ section with an explanation of their role, or they should be included in the author list if appropriate.

Authors are advised to consult the joint position statement from American Medical Writers Association (AMWA), European Medical Writers Association (EMWA), and International Society of Medical Publication Professionals (ISMPP).

Assistance with experiments and data analysis

Any significant contribution to the research reported, should be appropriately credited according to our authorship criteria.

If any parts of the research were outsourced to professional laboratories or to data analysts, this should be clearly stated within the manuscript, alongside an explanation of their role. Or, they should be included in the author list if appropriate.

Authors are responsible for retaining all of the original data related to their work, and should be prepared to share it with the journal editorial office if requested.

Acknowledgments

Any individuals who have contributed to the article (for example, technical assistance, formatting-related writing assistance, translators, scholarly discussions which significantly contributed to developing the article), but who do not meet the criteria for authorship, should be listed by name and affiliation in an ‘Acknowledgments’ section.

It is the responsibility of the authors to notify and obtain permission from those they wish to identify in this section. The process of obtaining permission should include sharing the article, so that those being identified can verify the context in which their contribution is being acknowledged.

Any assistance from AI tools for content generation (e.g. large language models) and other similar types of technical tools which generate article content, must be clearly acknowledged within the article. It is the responsibility of authors to ensure the validity, originality and integrity of their article content. Authors are expected to use these types of tools responsibly and in accordance with our editorial policies on authorship and principles of publishing ethics.

Biographical note

Please supply a short biographical note for each author. This could be adapted from your departmental website or academic networking profile and should be relatively brief (e.g. no more than 200 words).Authors are responsible for retaining all of the original data related to their work, and should be prepared to share it with the journal editorial office if requested.

Author name changes on published articles

There are many reasons why an author may change their name in the course of their career. And they may wish to update their published articles to reflect this change, without publicly announcing this through a correction notice. Taylor & Francis will update journal articles where an author makes a request for their own name change, full or partial, without the requirement for an accompanying correction notice. Any pronouns in accompanying author bios and declaration statements will also be updated as part of the name change, if required.

When an author requests a name change, Taylor & Francis will:

Change the metadata associated with the article on our Taylor & Francis Online platform.

Update the HTML and PDF version of the article.

Resupply the new metadata and article content to any abstracting and indexing services that have agreements with the journal. Note: such services may have their own bibliographic policies regarding author name changes. Taylor \u0026amp; Francis cannot be held responsible for controlling updates to articles on third party sites and services once an article has been disseminated.

If an author wishes for a correction notice to be published alongside their name change, Taylor & Francis will accommodate this on request. But, it is not required for an author name change to be made.

To request a name change, please contact your Journal’s Production Editor or contact us.

Taylor & Francis consider it a breach of publication ethics to request a name change for an individual without their explicit consent.

Additional resources

Co-authorship in the Humanities and Social Sciences – our white paper based on a global survey of researchers’ experiences of collaboration.

Discussion Document: Authorship – produced by COPE (Committee on Publication Ethics), this updated guide includes practical advice on addressing the most common ethical issues in this area

Taylor & Francis Editorial Policies

Ethics for authors – guidelines, support, and your checklist.

What does co-authorship mean and who gets to be one?

In the Laskowski Lab, we believe that co-authorship should be an outgoing discussion throughout the life of a research project. To us, co-authorship represents both credit for work done on the project and also, just as importantly, responsibility for the contents of the resulting paper. This does not mean that every co-author should necessarily have a detailed understanding of each method or technique, but it does mean that they should have a broad understanding of the contents of the paper and the major decisions that were made to produce the results. On highly collaborative projects, each co-author may have a deeper or shallower understanding of certain parts of a paper, based on their contributions. For example, one co-author was responsible for writing the code that extracts behavioral variables from videos; this co-author will have a deep understanding of that method. And while this co-author might not be expected to understand the details of how a particular brain imaging protocol was performed, they should understand what protocol was used and what data were collected from the protocol.

Co-authorship decisions .

Because of the dual role of co-authorship in that it confers both credit and responsibility, there is no single rule that can fully cover all scenarios where co-authorship decisions need to be made. But we find that the general guideline that a person should to contribute to at least two key aspects of any project/paper to be a good starting point for discussions about inclusion as a co-author:

- Research question development

- Experimental design or methodology development

- Data collection

- Data processing and analysis

- Manuscript writing

- Providing funding for the specific project

- Significant and constructive feedback on written drafts

That said, if any project component would not have been possible without the contributions of a particular person, or if they have made a very significant investment in any one project component, then that may be reason alone to include them as a co-author, assuming they are willing to hold responsibility for the contents of the paper. Regardless of contribution, all co-authors are always expected to read and approve the submitted version of the manuscript.

Discussions about co-authorship should happen early on and with regularity throughout a project. It is the responsibility of the project lead to discuss co-authorship options with people that are contributing to the project. For example, if two undergraduate students are assisting in data collection with a graduate student, this contribution alone (i.e. data collection) would not necessarily warrant co-authorship. However, the graduate student can explain to the undergraduate students about the roles and responsibilities of co-authorship and the undergraduate students may then become more actively involved in other aspects of the project such as analysis or writing and editing. As another example, simply providing general funding for a project participant (e.g. a PI that provides funding for a postdoc’s position) does not automatically assume co-authorship for the funder as these funds were not specific to the project.

Author order.

Once co-authorship is agreed upon, the next step is determining author order. In our field (ecology and evolution) the positions that generally carry the most weight are the first and last authors. In addition to author order, corresponding authorship is a role that any co-author can take.

Typically, but not always, the first author is the project lead and is generally the person that writes the initial draft of the manuscript. Co-first authors could be possible in some cases, for example, when two people have equal significant contributions to the study. Typically, but not always, the last author is an advisor that helps guide the first author and rest of the team of higher-level decisions. Finally, the corresponding author is the person who will handle communication about the manuscript during the submission process and will ultimately be the person contacted by anyone with questions about the paper. They hold perhaps the most responsibility for the paper in the long term and usually the corresponding author will be either the first or last author on the paper. Determining co-author positions and roles can be difficult as many projects often have more than two people that significantly contributed to that project and so discussions of author order should occur early in the process. However, author order is never set in stone and further discussions should happen any time there is any change in co-author contributions, such as when a particular co-author may contribute more or less than what was initially discussed.

Published in Advice & guidelines

- Publication Recognition

What is a Corresponding Author?

- 3 minute read

- 418.5K views

Table of Contents

Are you familiar with the terms “corresponding author” and “first author,” but you don’t know what they really mean? This is a common doubt, especially at the beginning of a researcher’s career, but easy to explain: fundamentally, a corresponding author takes the lead in the manuscript submission for publication process, whereas the first author is actually the one who did the research and wrote the manuscript.

The order of the authors can be arranged in whatever order suits the research group best, but submissions must be made by the corresponding author. It can also be the case that you don’t belong in a research group, and you want to publish your own paper independently, so you will probably be the corresponding author and first author at the same time.

Corresponding author meaning:

The corresponding author is the one individual who takes primary responsibility for communication with the journal during the manuscript submission, peer review, and publication process. Normally, he or she also ensures that all the journal’s administrative requirements, such as providing details of authorship, ethics committee approval, clinical trial registration documentation, and gathering conflict of interest forms and statements, are properly completed, although these duties may be delegated to one or more co-authors.

Generally, corresponding authors are senior researchers or group leaders with some – or a lot of experience – in the submission and publishing process of scientific research. They are someone who has not only contributed to the paper significantly but also has the ability to ensure that it goes through the publication process smoothly and successfully.

What is a corresponding author supposed to do?

A corresponding author is responsible for several critical aspects at each stage of a study’s dissemination – before and after publication.

If you are a corresponding author for the first time, take a look at these 6 simple tips that will help you succeed in this important task:

- Ensure that major deadlines are met

- Prepare a submission-ready manuscript

- Put together a submission package

- Get all author details correct

- Ensure ethical practices are followed

- Take the lead on open access

In short, the corresponding author is the one responsible for bringing research (and researchers) to the eyes of the public. To be successful, and because the researchers’ reputation is also at stake, corresponding authors always need to remember that a fine quality text is the first step to impress a team of peers or even a more refined audience. Elsevier’s team of language and translation professionals is always ready to perform text editing services that will provide the best possible material to go forward with a submission or/and a publication process confidently.

Who is the first author of a scientific paper?

The first author is usually the person who made the most significant intellectual contribution to the work. That includes designing the study, acquiring and analyzing data from experiments and writing the actual manuscript. As a first author, you will have to impress a vast group of players in the submission and publication processes. But, first of all, if you are in a research group, you will have to catch the corresponding author’s eye. The best way to give your work the attention it deserves, and the confidence you expect from your corresponding author, is to deliver a flawless manuscript, both in terms of scientific accuracy and grammar.

If you are not sure about the written quality of your manuscript, and you feel your career might depend on it, take full advantage of Elsevier’s professional text editing services. They can make a real difference in your work’s acceptance at each stage, before it comes out to the public.

Language Editing Services by Elsevier Author Services:

Through our Language Editing Services , we correct proofreading errors, and check for grammar and syntax to make sure your paper sounds natural and professional. We also make sure that editors and reviewers can understand the science behind your manuscript.

With more than a hundred years of experience in publishing, Elsevier is trusted by millions of authors around the world.

Check our video Elsevier Author Services – Language Editing to learn more about Author Services.

Find more about What is a corresponding author on Pinterest:

- Research Process

What is Journal Impact Factor?

What is a Good H-index?

You may also like.

How to Make a PowerPoint Presentation of Your Research Paper

How to Submit a Paper for Publication in a Journal

Input your search keywords and press Enter.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

How to Handle Co-authorship When Not Everyone’s Research Contributions Make It into the Paper

Gert helgesson.

1 Stockholm Centre for Healthcare Ethics (CHE), Department of Learning, Informatics, Management and Ethics, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden

Zubin Master

2 Biomedical Ethics Research Program and Center for Regenerative Medicine, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN USA

William Bülow

3 Department of Philosophy, Stockholm University, Stockholm, Sweden

Associated Data

Not applicable.

While much of the scholarly work on ethics relating to academic authorship examines the fair distribution of authorship credit, none has yet examined situations where a researcher contributes significantly to the project, but whose contributions do not make it into the final manuscript. Such a scenario is commonplace in collaborative research settings in many disciplines and may occur for a number of reasons, such as excluding research in order to provide the paper with a clearer focus, tell a particular story, or exclude negative results that do not fit the hypothesis. Our concern in this paper is less about the reasons for including or excluding data from a paper and more about distributing credit in this type of scenario. In particular, we argue that the notion ‘substantial contribution’, which is part of the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) authorship criteria, is ambiguous and that we should ask whether it concerns what ends up in the paper or what is a substantial contribution to the research process leading up to the paper. We then argue, based on the principles of fairness, due credit, and ensuring transparency and accountability in research, that the latter interpretation is more plausible from a research ethics point of view. We conclude that the ICMJE and other organizations interested in authorship and publication ethics should consider including guidance on authorship attribution in situations where researchers contribute significantly to the research process leading up to a specific paper, but where their contribution is finally omitted.

Introduction

Research typically proceeds in less predictable ways than we like to acknowledge. While a scientific ideal is that every part of a study is well considered and planned beforehand, and the research process thereafter mainly consists in performing according to protocol, a typical experience from the field is that such description is far from the truth. Planning and execution of plans are rarely that straightforward. To the contrary, many decisions are made along the way regarding both data collection and analysis: new experiments, comparisons, interviews, and surveys may be decided as the work proceeds, and additional analyses may be added to the ones originally decided upon. Sometimes these changes are driven by peer review. Some of the research contributions eventually pass critical scrutiny and make it into the paper, while others for one reason or another end up in the waste bin or are shelved for possible future use.

There may be positive as well as negative things to say about such practice in relation to the philosophy of science and meta science, relating to curiosity and creativity on the one hand and hypothesis testing and reproducibility issues on the other. Furthermore, some of the choices made regarding what results get included in papers may be objectionable from a research ethics perspective, such as excluding ‘negative results’ because they contradict the main results of the paper or are considered unworthy of publication, hence contributing to the positive publication bias (Chalmers et al., 1990 ; Connor, 2008 ; Dirnagl & Lauritzen, 2010 ). Other exclusions may be fully acceptable, based on estimations of relevance and the consideration that you cannot include everything in the paper if it is to be readable.

The present paper does not deal with what exclusions of research results are acceptable or not, but with a related issue, namely how to handle authorship attributions in papers where plans change along the way, so that some of the results derived are not included in the final version of the paper. This topic is a special case of the larger topic of who should be included as authors on research papers, which involves ethical aspects like appropriate allocation of credit in research (and, hence, fairness), transparency and accountability (Shamoo & Resnik, 2009 ). Given the frequency of authorship disagreements (Marušić et al., 2011 ; Nylenna et al., 2014 ; Okonta & Rossouw, 2013 ), this analysis is important also because good authorship practices serve to foster positive team dynamics and collaboration and are less likely to lead to authorship disputes, which could impact interpersonal and professional relationships and possibly lead to subsequent misbehaviors (Smith et al., 2020 ; Tijdink et al., 2016 ).

The International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) has produced the most widely acknowledged authorship recommendations, which serve as guidance for the biomedical sciences among other areas of scholarship (ICMJE, 2019 ). The recommendations provide a set of criteria that are jointly necessary and sufficient in order to determine authorship (see Box Box1). 1 ). While these authorship criteria have met their due share of criticism (Laflin et al. 2005 ; Osborne & Holland, 2009 ; Puljak & Sambunjak, 2000 ; Smith et al. 2014 ), we find them reasonable, although not flawless (see e.g. Helgesson & Eriksson, 2018 ; Helgesson et al 2019 ). We therefore treat the ICMJE criteria as the starting point for our discussion of whether granting authorship to someone can be justified even when that person’s specific contributions do not make it into the final version of the manuscript. However, the problem we have identified, having to do with the first criterion–that authors should have made a ‘substantial contribution’ to the work–is not clearly addressed by the ICMJE recommendations. In fact, the problem is overlooked by most suggestions for how to think about the allocation of authorship in co-researched papers (see e.g., Shamoo & Resnik, 2009 ; Hansson, 2017 ; Moffatt, 2018 ).

ICMJE Authorship recommendations

| The International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) recommends that authorship be given to researchers who have contributed substantially and have satisfied the following 4 criteria: |

Substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work; or the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data for the work; AND Drafting the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content; AND Final approval of the version to be published; AND Agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. |

| The ICMJE explain that the four criteria are not meant to be used to disqualify researchers from authorship credit by denying them the ability to be involved in drafting or revising the manuscript or approving the final version to be published. All researchers meeting the first criterion should be given the opportunity to participate in drafting, revising and approving the manuscript. Contributors who are unable to meet all four criteria for authorship should be acknowledged in an Acknowledgement section after obtaining their permission (ICMJE 2019) |

Hence, the aim of this paper is to determine, in relation to the ICMJE authorship criteria, how authorship should be handled in situations where researchers have contributed substantively to the research and drafting of the manuscript, but the results themselves are not included in the final manuscript. Before we discuss this issue in greater detail, we would like to flesh out the problem by providing a case.

A Case of Omitted Results

To recognize the problem we have in mind, consider the following case: Two senior researchers and three junior researchers work together on a study. One of the senior researchers take the main responsibility for conception and design of the study and assume the role of principal investigator (PI), while the other senior researcher helps substantially with suggestions and input regarding specific analyses, and also provides support in the lab, where the empirical data is obtained. The empirical work is divided among the three junior researchers Ann, Bo, and Choi in such a way that they are individually fully responsible for some part of the design and conducting the lab work, resulting in data collection, analysis and interpretation of results. As times passes, Ann, Bo, and Choi all spend many hours working hard and eventually deliver according to plan. When looking at the results and discussing the study further, all researchers on the team agree on the contents of the paper. It turns out that while the analyses made by Ann and Bo fit well with the final idea of the paper, Choi’s analyses fall outside the scope of the narrative eventually decided upon and are therefore at the end not included. This is where the discussion starts in the group. Should Choi be included as co-author? She will surely do her part in revising the manuscript and approve the final version to satisfy the second and third ICMJE criteria, but did she make a ‘substantial contribution’ to the work under the first criterion of the ICMJE recommendations? Choi has contributed to discussions throughout the life of the project at team meetings and did help in the design of her part of the experiments and conducted those studies, collected and analyzed the data, and helped interpret the results. However, she was unable to contribute to the overall conception and design of the project at this early stage of her career, similar to Ann and Bo. On an honest estimation, it can be concluded that she has not made a substantial contribution to the paper if the excluded results, her main contribution, do not make it into the final manuscript. So what to do?

Before we move on, let us notice that there are several possible reasons for not including Choi’s contribution in the paper. One reason could be that the quality of her work is too low. Another reason could be that her results are relevant but do not support the overall thesis of the paper–they are in this respect so-called negative results. As we have already indicated, omitting negative results might be problematic from a research ethics perspective, especially if the reason for omitting them is that they contradict one’s hypothesis. 1 However, another reason for not including Choi’s contribution could be that the results are taken not to be relevant (or relevant enough) to the paper eventually decided upon, meaning that her results helped shape the final story being told in the paper but were not being reported in the publication. For the sake of argument, our discussion in what follows assumes that the reason for omitting Choi’s contribution is ethically sound and does not constitute a research misbehaviour in its own right.

Substantial Contribution and Intellectual Involvement

As noted in the introduction, the problem we describe concerns the first ICMJE criterion for authorship. This criterion does two things: it tells us the broad categories of contributions that count towards authorship on the byline (conception or design, acquisition, analysis or interpretation of data), and it tells us the extent of contribution needed, namely that the contribution(s) have to be ‘substantial.’ For the sake of argument, let us assume that Choi’s research contributions would clearly have been substantial enough to grant a position on the paper if her data and analyses had been included in the manuscript. Now if they are not included, does it mean that Choi should not be listed as an author? And if she should, how is this compatible with the idea of a substantial contribution?

We believe that situations like Choi’s reveal that the ‘substantial contribution’ requirement of the ICMJE recommendations is not only vague in terms of what is required for a contribution to be large enough to be substantial (Cutas & Shaw, 2015 ; Laflin et al. 2005 ; Osborne & Holland, 2009 ), but also ambiguous in terms of what specifically counts as a contribution. In particular, we hold that we should distinguish between two interpretations of this criterion, namely whether it concerns a substantial contribution to what ends up in the paper or whether it concerns a substantial contribution to the research process leading up to the paper . While Choi does not qualify as an author in the former sense, she might do so if we accept the latter interpretation of the substantial contribution criterion. The question remains which of the two interpretations of ‘substantial contribution’ is the most plausible one.

To be certain, making a substantial contribution is not enough to qualify for authorship according to the ICMJE criteria. Critical revision and final approval of the manuscript outlined in the second and third ICMJE criteria is needed as well. The critical revision requires intellectual involvement in the paper under production. Hence, intellectual involvement in the research at hand is part of the ICMJE authorship requirements (Helgesson, 2015 ).

Before returning to our case, let us first present and consider another one in which the main point is to clearly show that one might make a substantial contribution to the research of a paper without contributing to what ends up in the paper. Assume that a group is writing a paper on research methods for accomplishing X in the research field of Z . They proceed by examining all existing methods mentioned in the literature potentially relevant for the specific purpose at hand, dividing the work among them so that each researcher involved analyzes the same number of methods each. The results from the analyses of the methods found to work are described at some length in the final paper, while failing methods are merely mentioned (although they are as completely documented by the research group). Since it is not known beforehand which methods will work and which ones will not, each analysis will be equally relevant to the fulfillment of the aim of the paper–to clarify the best methods to accomplish X . If the research contribution is substantial, and other authorship criteria are fulfilled, all researchers should be included as co-authors of the paper irrespective of whether their method is presented in the manuscript or not. Hence, there is a case to be made that substantial research contributions sometimes should count towards authorship even if they are not represented equally in the final paper.

Fairness, Transparency and Accountability

As previously detailed, we believe that cases like Choi’s reveal an ambiguity concerning the notion of ‘substantial contribution.’ It might be understood as saying that what is required is either a substantial contribution to what ends up in the paper or a substantial contribution to the research leading up to the paper. If the first interpretation is correct, then Choi should be excluded from authorship, despite the work and effort that she has put into this collaborative work. If Choi ought to be included in the paper, which we think she should, this is because it is enough, with respect to the first authorship criterion, that she has contributed in a substantial and relevant way to the research leading up to the paper, even if her specific empirical contributions did not end up in the paper. We will therefore defend this interpretation of the substantial contribution requirement of the ICMJE recommendations.

Generally, there are two sets of reasons for caring about how authorship is handled when a researcher makes a substantial contribution that is not reported in the manuscript. First, it is a matter of transparency and accountability about the research process: what happened and who were involved? From this perspective, it is misleading if people who were deeply involved in the work are not described in the paper. Also for reasons of accountability, those responsible for the work should be identifiable to others. Admittedly, both of these aspects could be fulfilled by some other means than that of attribution of authorship, such as a sufficiently detailed description of everyone’s contributions, including those not included as authors. But with present practices, including someone as co-author or merely listing that person in the contributor list or acknowledgements communicates two quite different messages about the person’s contribution and its relative importance. Our argument here for the interpretation that what counts as ground for co-authorship is a substantial contribution to the research leading to the paper is that excluding Choi would be misleading about her role in the project, hence not fulfilling the need for transparency and accountability.

Second, authorship is a matter of due scientific credit and fairness, which to our mind provides a strong reason for including Choi. In particular, our argument for the interpretation that what counts is a substantial contribution to the research leading to the paper is that excluding Choi seems unfair. After all, Choi has contributed as much to the research leading to the paper as her colleagues. Admittedly, the aim of the paper shifted, or took a form that made Choi’s contribution less relevant to what was reported in the paper, but not less relevant to the end product leading to the research publication. Also, we should note that this interpretation clearly ties Choi’s claim to authorship to the good work she has done rather than to the results being reported only. In contrast, if what is required is a substantial contribution to the research presented in the paper, then it seems that whether any of the junior researchers end up in the authorship byline will be, to some degree, a matter of luck , since neither an initial agreement or great efforts along the way is sufficient. This too seems unfair. Contributing with a considerable amount of good work and then not receiving authorship because of a change of plans seems unfair in a vein similar to misuse of the ICMJE authorship criteria by letting people contribute substantially to the work, then not offer them the opportunity to revise, and finally not include them as authors since they do not fulfill all criteria (ICMJE, 2019 ).

Counter Arguments

There are several possible counterarguments to our thesis that should be addressed. First, it might be argued that Choi’s contribution is rather general in its nature, and hence should not count towards authorship. After all, authorship is not about general research contributions, such as having contributed substantially to a large research application providing financial support for the production of many papers (reaching a level of detail that the application did not), but contributions to the specific paper (Smith & Master, 2017 ). Similarly, being a member of the research group does not mean that one should be included as co-author on every paper produced by the group. Instead, you need to contribute substantially to every paper in order to be listed as author. However, one may agree with the general thrust of this argument without agreeing that it works as an argument against including Choi. That is because it is an open question what should be meant by ‘contributions to the specific paper’–is it what the final version of the paper contains or is it the work specifically concerning and leading up to that paper? It seems to us that the better understanding of ‘research contribution’ is the work and intellectual engagement contributed in the context of a study or project around a specified research aim and/or a set of specified research questions, rather than what of that work was eventually included in the paper–as long as the work, as it was carried out, was perceived by the research group as relevant to what they were doing.

Second, one might ask why it would not be enough if Choi’s contribution were recognized through an acknowledgement, especially if it contains a clear statement of her contribution. Important contributions that do not qualify for authorship are often handled that way, so why shouldn’t we think that it is enough in this case? There are two connected responses to this inquiry. First, as already argued, Choi has made contributions qualifying her for authorship. Leaving her out would therefore be misleading in the sense that it would give a false impression about the relative value of her contribution to the research. Second, it would be utterly unfair to grant her an acknowledgement if her colleagues, making contributions of equal importance (according to our reasoning above), are included as authors. Again, as discussed above, allocation of authorship concerns transparency and accountability on the one hand, and credit and fairness on the other. Acknowledgements contribute to transparency, but are useless from a career perspective in most, if not all, research areas, hence leaving Choi with an inappropriate credit for her work. 2

Third, there is a complication with our interpretation of the substantial contribution requirement that we may call the multiplicity problem . Imagine that the overall thrust of our argument was followed by the research group and that Choi was included as co-author in the paper based on her substantial contributions to the work with the paper even though her work was not presented in the paper. Further imagine that later on, the senior researchers find it a good idea to include the previously excluded work by Choi in another paper where it becomes more relevant. The work then included is indeed substantial, which provides an argument why Choi should be included as co-author also in this second paper. But doesn’t this amount to an unfair form of double counting? In response, we think that it might be acceptable to include Choi as co-author on both papers, insofar as she fulfills the following two conditions: the contribution under the first criterion has to be different in the two papers (which is not the same thing as saying that the contribution has to concern different data sets), and the other ICMJE authorship criteria need to be fulfilled in relation to the second paper as well. Admittedly, Choi was not part of the research process, and perhaps not intellectually involved in the questions particularly addressed in this second paper, at an early stage. But once included with her empirical contribution (originally omitted and hence different from her contribution to the first paper), she could engage in the larger questions of this second paper and could contribute intellectually as well. For example, she could participate in the process of revising versions of the manuscript critically for important intellectual content, as put in the second criterion of the ICMJE authorship criteria. If so, then it seems right that she is included as an author also in the second paper since she fulfils criteria 1–4 in relation to that paper. 3

But then there seems to be a further complication with our account that we might call the backfire problem (which is a counter argument to our response to the multiplicity problem). Again, assume that Choi was included as an author on the first paper where her work was not presented in the paper itself, but that the work has also begun with the second paper based on Choi’s contribution. Ann and Bo now enter the scene and ask why they are not included in the second paper–should they be? After all, if Choi ought to be included as an author on the first paper, on the basis that her work with the omitted empirical contribution was an important part of the research process leading up to the first paper, then doesn’t this suggest that Ann and Bo can raise similar legitimate demands on being included as authors on the second paper? In response, we suggest that the answer can certainly not be a general ‘Yes,’ but that their inclusion in the second paper is justifiable if they were sufficiently involved in the second paper to be correctly described as having contributed substantially to the process leading up to that specific paper. For example, the second paper might be a natural follow-up of the first paper, covering further issues already considered while they were working on the first paper. 4 However, it all hinges on whether Ann and Bo contributed substantially, in the sense we have defended in the above.