Choose Your Test

Sat / act prep online guides and tips, getting college essay help: important do's and don’ts.

College Essays

If you grow up to be a professional writer, everything you write will first go through an editor before being published. This is because the process of writing is really a process of re-writing —of rethinking and reexamining your work, usually with the help of someone else. So what does this mean for your student writing? And in particular, what does it mean for very important, but nonprofessional writing like your college essay? Should you ask your parents to look at your essay? Pay for an essay service?

If you are wondering what kind of help you can, and should, get with your personal statement, you've come to the right place! In this article, I'll talk about what kind of writing help is useful, ethical, and even expected for your college admission essay . I'll also point out who would make a good editor, what the differences between editing and proofreading are, what to expect from a good editor, and how to spot and stay away from a bad one.

Table of Contents

What Kind of Help for Your Essay Can You Get?

What's Good Editing?

What should an editor do for you, what kind of editing should you avoid, proofreading, what's good proofreading, what kind of proofreading should you avoid.

What Do Colleges Think Of You Getting Help With Your Essay?

Who Can/Should Help You?

Advice for editors.

Should You Pay Money For Essay Editing?

The Bottom Line

What's next, what kind of help with your essay can you get.

Rather than talking in general terms about "help," let's first clarify the two different ways that someone else can improve your writing . There is editing, which is the more intensive kind of assistance that you can use throughout the whole process. And then there's proofreading, which is the last step of really polishing your final product.

Let me go into some more detail about editing and proofreading, and then explain how good editors and proofreaders can help you."

Editing is helping the author (in this case, you) go from a rough draft to a finished work . Editing is the process of asking questions about what you're saying, how you're saying it, and how you're organizing your ideas. But not all editing is good editing . In fact, it's very easy for an editor to cross the line from supportive to overbearing and over-involved.

Ability to clarify assignments. A good editor is usually a good writer, and certainly has to be a good reader. For example, in this case, a good editor should make sure you understand the actual essay prompt you're supposed to be answering.

Open-endedness. Good editing is all about asking questions about your ideas and work, but without providing answers. It's about letting you stick to your story and message, and doesn't alter your point of view.

Think of an editor as a great travel guide. It can show you the many different places your trip could take you. It should explain any parts of the trip that could derail your trip or confuse the traveler. But it never dictates your path, never forces you to go somewhere you don't want to go, and never ignores your interests so that the trip no longer seems like it's your own. So what should good editors do?

Help Brainstorm Topics

Sometimes it's easier to bounce thoughts off of someone else. This doesn't mean that your editor gets to come up with ideas, but they can certainly respond to the various topic options you've come up with. This way, you're less likely to write about the most boring of your ideas, or to write about something that isn't actually important to you.

If you're wondering how to come up with options for your editor to consider, check out our guide to brainstorming topics for your college essay .

Help Revise Your Drafts

Here, your editor can't upset the delicate balance of not intervening too much or too little. It's tricky, but a great way to think about it is to remember: editing is about asking questions, not giving answers .

Revision questions should point out:

- Places where more detail or more description would help the reader connect with your essay

- Places where structure and logic don't flow, losing the reader's attention

- Places where there aren't transitions between paragraphs, confusing the reader

- Moments where your narrative or the arguments you're making are unclear

But pointing to potential problems is not the same as actually rewriting—editors let authors fix the problems themselves.

Bad editing is usually very heavy-handed editing. Instead of helping you find your best voice and ideas, a bad editor changes your writing into their own vision.

You may be dealing with a bad editor if they:

- Add material (examples, descriptions) that doesn't come from you

- Use a thesaurus to make your college essay sound "more mature"

- Add meaning or insight to the essay that doesn't come from you

- Tell you what to say and how to say it

- Write sentences, phrases, and paragraphs for you

- Change your voice in the essay so it no longer sounds like it was written by a teenager

Colleges can tell the difference between a 17-year-old's writing and a 50-year-old's writing. Not only that, they have access to your SAT or ACT Writing section, so they can compare your essay to something else you wrote. Writing that's a little more polished is great and expected. But a totally different voice and style will raise questions.

Where's the Line Between Helpful Editing and Unethical Over-Editing?

Sometimes it's hard to tell whether your college essay editor is doing the right thing. Here are some guidelines for staying on the ethical side of the line.

- An editor should say that the opening paragraph is kind of boring, and explain what exactly is making it drag. But it's overstepping for an editor to tell you exactly how to change it.

- An editor should point out where your prose is unclear or vague. But it's completely inappropriate for the editor to rewrite that section of your essay.

- An editor should let you know that a section is light on detail or description. But giving you similes and metaphors to beef up that description is a no-go.

Proofreading (also called copy-editing) is checking for errors in the last draft of a written work. It happens at the end of the process and is meant as the final polishing touch. Proofreading is meticulous and detail-oriented, focusing on small corrections. It sands off all the surface rough spots that could alienate the reader.

Because proofreading is usually concerned with making fixes on the word or sentence level, this is the only process where someone else can actually add to or take away things from your essay . This is because what they are adding or taking away tends to be one or two misplaced letters.

Laser focus. Proofreading is all about the tiny details, so the ability to really concentrate on finding small slip-ups is a must.

Excellent grammar and spelling skills. Proofreaders need to dot every "i" and cross every "t." Good proofreaders should correct spelling, punctuation, capitalization, and grammar. They should put foreign words in italics and surround quotations with quotation marks. They should check that you used the correct college's name, and that you adhered to any formatting requirements (name and date at the top of the page, uniform font and size, uniform spacing).

Limited interference. A proofreader needs to make sure that you followed any word limits. But if cuts need to be made to shorten the essay, that's your job and not the proofreader's.

A bad proofreader either tries to turn into an editor, or just lacks the skills and knowledge necessary to do the job.

Some signs that you're working with a bad proofreader are:

- If they suggest making major changes to the final draft of your essay. Proofreading happens when editing is already finished.

- If they aren't particularly good at spelling, or don't know grammar, or aren't detail-oriented enough to find someone else's small mistakes.

- If they start swapping out your words for fancier-sounding synonyms, or changing the voice and sound of your essay in other ways. A proofreader is there to check for errors, not to take the 17-year-old out of your writing.

What Do Colleges Think of Your Getting Help With Your Essay?

Admissions officers agree: light editing and proofreading are good—even required ! But they also want to make sure you're the one doing the work on your essay. They want essays with stories, voice, and themes that come from you. They want to see work that reflects your actual writing ability, and that focuses on what you find important.

On the Importance of Editing

Get feedback. Have a fresh pair of eyes give you some feedback. Don't allow someone else to rewrite your essay, but do take advantage of others' edits and opinions when they seem helpful. ( Bates College )

Read your essay aloud to someone. Reading the essay out loud offers a chance to hear how your essay sounds outside your head. This exercise reveals flaws in the essay's flow, highlights grammatical errors and helps you ensure that you are communicating the exact message you intended. ( Dickinson College )

On the Value of Proofreading

Share your essays with at least one or two people who know you well—such as a parent, teacher, counselor, or friend—and ask for feedback. Remember that you ultimately have control over your essays, and your essays should retain your own voice, but others may be able to catch mistakes that you missed and help suggest areas to cut if you are over the word limit. ( Yale University )

Proofread and then ask someone else to proofread for you. Although we want substance, we also want to be able to see that you can write a paper for our professors and avoid careless mistakes that would drive them crazy. ( Oberlin College )

On Watching Out for Too Much Outside Influence

Limit the number of people who review your essay. Too much input usually means your voice is lost in the writing style. ( Carleton College )

Ask for input (but not too much). Your parents, friends, guidance counselors, coaches, and teachers are great people to bounce ideas off of for your essay. They know how unique and spectacular you are, and they can help you decide how to articulate it. Keep in mind, however, that a 45-year-old lawyer writes quite differently from an 18-year-old student, so if your dad ends up writing the bulk of your essay, we're probably going to notice. ( Vanderbilt University )

Now let's talk about some potential people to approach for your college essay editing and proofreading needs. It's best to start close to home and slowly expand outward. Not only are your family and friends more invested in your success than strangers, but they also have a better handle on your interests and personality. This knowledge is key for judging whether your essay is expressing your true self.

Parents or Close Relatives

Your family may be full of potentially excellent editors! Parents are deeply committed to your well-being, and family members know you and your life well enough to offer details or incidents that can be included in your essay. On the other hand, the rewriting process necessarily involves criticism, which is sometimes hard to hear from someone very close to you.

A parent or close family member is a great choice for an editor if you can answer "yes" to the following questions. Is your parent or close relative a good writer or reader? Do you have a relationship where editing your essay won't create conflict? Are you able to constructively listen to criticism and suggestion from the parent?

One suggestion for defusing face-to-face discussions is to try working on the essay over email. Send your parent a draft, have them write you back some comments, and then you can pick which of their suggestions you want to use and which to discard.

Teachers or Tutors

A humanities teacher that you have a good relationship with is a great choice. I am purposefully saying humanities, and not just English, because teachers of Philosophy, History, Anthropology, and any other classes where you do a lot of writing, are all used to reviewing student work.

Moreover, any teacher or tutor that has been working with you for some time, knows you very well and can vet the essay to make sure it "sounds like you."

If your teacher or tutor has some experience with what college essays are supposed to be like, ask them to be your editor. If not, then ask whether they have time to proofread your final draft.

Guidance or College Counselor at Your School

The best thing about asking your counselor to edit your work is that this is their job. This means that they have a very good sense of what colleges are looking for in an application essay.

At the same time, school counselors tend to have relationships with admissions officers in many colleges, which again gives them insight into what works and which college is focused on what aspect of the application.

Unfortunately, in many schools the guidance counselor tends to be way overextended. If your ratio is 300 students to 1 college counselor, you're unlikely to get that person's undivided attention and focus. It is still useful to ask them for general advice about your potential topics, but don't expect them to be able to stay with your essay from first draft to final version.

Friends, Siblings, or Classmates

Although they most likely don't have much experience with what colleges are hoping to see, your peers are excellent sources for checking that your essay is you .

Friends and siblings are perfect for the read-aloud edit. Read your essay to them so they can listen for words and phrases that are stilted, pompous, or phrases that just don't sound like you.

You can even trade essays and give helpful advice on each other's work.

If your editor hasn't worked with college admissions essays very much, no worries! Any astute and attentive reader can still greatly help with your process. But, as in all things, beginners do better with some preparation.

First, your editor should read our advice about how to write a college essay introduction , how to spot and fix a bad college essay , and get a sense of what other students have written by going through some admissions essays that worked .

Then, as they read your essay, they can work through the following series of questions that will help them to guide you.

Introduction Questions

- Is the first sentence a killer opening line? Why or why not?

- Does the introduction hook the reader? Does it have a colorful, detailed, and interesting narrative? Or does it propose a compelling or surprising idea?

- Can you feel the author's voice in the introduction, or is the tone dry, dull, or overly formal? Show the places where the voice comes through.

Essay Body Questions

- Does the essay have a through-line? Is it built around a central argument, thought, idea, or focus? Can you put this idea into your own words?

- How is the essay organized? By logical progression? Chronologically? Do you feel order when you read it, or are there moments where you are confused or lose the thread of the essay?

- Does the essay have both narratives about the author's life and explanations and insight into what these stories reveal about the author's character, personality, goals, or dreams? If not, which is missing?

- Does the essay flow? Are there smooth transitions/clever links between paragraphs? Between the narrative and moments of insight?

Reader Response Questions

- Does the writer's personality come through? Do we know what the speaker cares about? Do we get a sense of "who he or she is"?

- Where did you feel most connected to the essay? Which parts of the essay gave you a "you are there" sensation by invoking your senses? What moments could you picture in your head well?

- Where are the details and examples vague and not specific enough?

- Did you get an "a-ha!" feeling anywhere in the essay? Is there a moment of insight that connected all the dots for you? Is there a good reveal or "twist" anywhere in the essay?

- What are the strengths of this essay? What needs the most improvement?

Should You Pay Money for Essay Editing?

One alternative to asking someone you know to help you with your college essay is the paid editor route. There are two different ways to pay for essay help: a private essay coach or a less personal editing service , like the many proliferating on the internet.

My advice is to think of these options as a last resort rather than your go-to first choice. I'll first go through the reasons why. Then, if you do decide to go with a paid editor, I'll help you decide between a coach and a service.

When to Consider a Paid Editor

In general, I think hiring someone to work on your essay makes a lot of sense if none of the people I discussed above are a possibility for you.

If you can't ask your parents. For example, if your parents aren't good writers, or if English isn't their first language. Or if you think getting your parents to help is going create unnecessary extra conflict in your relationship with them (applying to college is stressful as it is!)

If you can't ask your teacher or tutor. Maybe you don't have a trusted teacher or tutor that has time to look over your essay with focus. Or, for instance, your favorite humanities teacher has very limited experience with college essays and so won't know what admissions officers want to see.

If you can't ask your guidance counselor. This could be because your guidance counselor is way overwhelmed with other students.

If you can't share your essay with those who know you. It might be that your essay is on a very personal topic that you're unwilling to share with parents, teachers, or peers. Just make sure it doesn't fall into one of the bad-idea topics in our article on bad college essays .

If the cost isn't a consideration. Many of these services are quite expensive, and private coaches even more so. If you have finite resources, I'd say that hiring an SAT or ACT tutor (whether it's PrepScholar or someone else) is better way to spend your money . This is because there's no guarantee that a slightly better essay will sufficiently elevate the rest of your application, but a significantly higher SAT score will definitely raise your applicant profile much more.

Should You Hire an Essay Coach?

On the plus side, essay coaches have read dozens or even hundreds of college essays, so they have experience with the format. Also, because you'll be working closely with a specific person, it's more personal than sending your essay to a service, which will know even less about you.

But, on the minus side, you'll still be bouncing ideas off of someone who doesn't know that much about you . In general, if you can adequately get the help from someone you know, there is no advantage to paying someone to help you.

If you do decide to hire a coach, ask your school counselor, or older students that have used the service for recommendations. If you can't afford the coach's fees, ask whether they can work on a sliding scale —many do. And finally, beware those who guarantee admission to your school of choice—essay coaches don't have any special magic that can back up those promises.

Should You Send Your Essay to a Service?

On the plus side, essay editing services provide a similar product to essay coaches, and they cost significantly less . If you have some assurance that you'll be working with a good editor, the lack of face-to-face interaction won't prevent great results.

On the minus side, however, it can be difficult to gauge the quality of the service before working with them . If they are churning through many application essays without getting to know the students they are helping, you could end up with an over-edited essay that sounds just like everyone else's. In the worst case scenario, an unscrupulous service could send you back a plagiarized essay.

Getting recommendations from friends or a school counselor for reputable services is key to avoiding heavy-handed editing that writes essays for you or does too much to change your essay. Including a badly-edited essay like this in your application could cause problems if there are inconsistencies. For example, in interviews it might be clear you didn't write the essay, or the skill of the essay might not be reflected in your schoolwork and test scores.

Should You Buy an Essay Written by Someone Else?

Let me elaborate. There are super sketchy places on the internet where you can simply buy a pre-written essay. Don't do this!

For one thing, you'll be lying on an official, signed document. All college applications make you sign a statement saying something like this:

I certify that all information submitted in the admission process—including the application, the personal essay, any supplements, and any other supporting materials—is my own work, factually true, and honestly presented... I understand that I may be subject to a range of possible disciplinary actions, including admission revocation, expulsion, or revocation of course credit, grades, and degree, should the information I have certified be false. (From the Common Application )

For another thing, if your academic record doesn't match the essay's quality, the admissions officer will start thinking your whole application is riddled with lies.

Admission officers have full access to your writing portion of the SAT or ACT so that they can compare work that was done in proctored conditions with that done at home. They can tell if these were written by different people. Not only that, but there are now a number of search engines that faculty and admission officers can use to see if an essay contains strings of words that have appeared in other essays—you have no guarantee that the essay you bought wasn't also bought by 50 other students.

- You should get college essay help with both editing and proofreading

- A good editor will ask questions about your idea, logic, and structure, and will point out places where clarity is needed

- A good editor will absolutely not answer these questions, give you their own ideas, or write the essay or parts of the essay for you

- A good proofreader will find typos and check your formatting

- All of them agree that getting light editing and proofreading is necessary

- Parents, teachers, guidance or college counselor, and peers or siblings

- If you can't ask any of those, you can pay for college essay help, but watch out for services or coaches who over-edit you work

- Don't buy a pre-written essay! Colleges can tell, and it'll make your whole application sound false.

Ready to start working on your essay? Check out our explanation of the point of the personal essay and the role it plays on your applications and then explore our step-by-step guide to writing a great college essay .

Using the Common Application for your college applications? We have an excellent guide to the Common App essay prompts and useful advice on how to pick the Common App prompt that's right for you . Wondering how other people tackled these prompts? Then work through our roundup of over 130 real college essay examples published by colleges .

Stressed about whether to take the SAT again before submitting your application? Let us help you decide how many times to take this test . If you choose to go for it, we have the ultimate guide to studying for the SAT to give you the ins and outs of the best ways to study.

Anna scored in the 99th percentile on her SATs in high school, and went on to major in English at Princeton and to get her doctorate in English Literature at Columbia. She is passionate about improving student access to higher education.

Ask a Question Below

Have any questions about this article or other topics? Ask below and we'll reply!

Improve With Our Famous Guides

- For All Students

The 5 Strategies You Must Be Using to Improve 160+ SAT Points

How to Get a Perfect 1600, by a Perfect Scorer

Series: How to Get 800 on Each SAT Section:

Score 800 on SAT Math

Score 800 on SAT Reading

Score 800 on SAT Writing

Series: How to Get to 600 on Each SAT Section:

Score 600 on SAT Math

Score 600 on SAT Reading

Score 600 on SAT Writing

Free Complete Official SAT Practice Tests

What SAT Target Score Should You Be Aiming For?

15 Strategies to Improve Your SAT Essay

The 5 Strategies You Must Be Using to Improve 4+ ACT Points

How to Get a Perfect 36 ACT, by a Perfect Scorer

Series: How to Get 36 on Each ACT Section:

36 on ACT English

36 on ACT Math

36 on ACT Reading

36 on ACT Science

Series: How to Get to 24 on Each ACT Section:

24 on ACT English

24 on ACT Math

24 on ACT Reading

24 on ACT Science

What ACT target score should you be aiming for?

ACT Vocabulary You Must Know

ACT Writing: 15 Tips to Raise Your Essay Score

How to Get Into Harvard and the Ivy League

How to Get a Perfect 4.0 GPA

How to Write an Amazing College Essay

What Exactly Are Colleges Looking For?

Is the ACT easier than the SAT? A Comprehensive Guide

Should you retake your SAT or ACT?

When should you take the SAT or ACT?

Stay Informed

Get the latest articles and test prep tips!

Looking for Graduate School Test Prep?

Check out our top-rated graduate blogs here:

GRE Online Prep Blog

GMAT Online Prep Blog

TOEFL Online Prep Blog

Holly R. "I am absolutely overjoyed and cannot thank you enough for helping me!”

Ultimate Guide to Writing Your College Essay

Tips for writing an effective college essay.

College admissions essays are an important part of your college application and gives you the chance to show colleges and universities your character and experiences. This guide will give you tips to write an effective college essay.

Want free help with your college essay?

UPchieve connects you with knowledgeable and friendly college advisors—online, 24/7, and completely free. Get 1:1 help brainstorming topics, outlining your essay, revising a draft, or editing grammar.

Writing a strong college admissions essay

Learn about the elements of a solid admissions essay.

Avoiding common admissions essay mistakes

Learn some of the most common mistakes made on college essays

Brainstorming tips for your college essay

Stuck on what to write your college essay about? Here are some exercises to help you get started.

How formal should the tone of your college essay be?

Learn how formal your college essay should be and get tips on how to bring out your natural voice.

Taking your college essay to the next level

Hear an admissions expert discuss the appropriate level of depth necessary in your college essay.

Student Stories

Student Story: Admissions essay about a formative experience

Get the perspective of a current college student on how he approached the admissions essay.

Student Story: Admissions essay about personal identity

Get the perspective of a current college student on how she approached the admissions essay.

Student Story: Admissions essay about community impact

Student story: admissions essay about a past mistake, how to write a college application essay, tips for writing an effective application essay, sample college essay 1 with feedback, sample college essay 2 with feedback.

This content is licensed by Khan Academy and is available for free at www.khanacademy.org.

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Welcome to the Purdue Online Writing Lab

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

The Online Writing Lab at Purdue University houses writing resources and instructional material, and we provide these as a free service of the Writing Lab at Purdue. Students, members of the community, and users worldwide will find information to assist with many writing projects. Teachers and trainers may use this material for in-class and out-of-class instruction.

The Purdue On-Campus Writing Lab and Purdue Online Writing Lab assist clients in their development as writers—no matter what their skill level—with on-campus consultations, online participation, and community engagement. The Purdue Writing Lab serves the Purdue, West Lafayette, campus and coordinates with local literacy initiatives. The Purdue OWL offers global support through online reference materials and services.

A Message From the Assistant Director of Content Development

The Purdue OWL® is committed to supporting students, instructors, and writers by offering a wide range of resources that are developed and revised with them in mind. To do this, the OWL team is always exploring possibilties for a better design, allowing accessibility and user experience to guide our process. As the OWL undergoes some changes, we welcome your feedback and suggestions by email at any time.

Please don't hesitate to contact us via our contact page if you have any questions or comments.

All the best,

Social Media

Facebook twitter.

Totally Free Essay Database

Most popular subjects.

- Film Studies (1735)

- Paintings (518)

- Music (460)

- Management (5595)

- Case Study (4335)

- Company Analysis (3057)

- Cultural Studies (617)

- Cultural Issues (218)

- Ethnicity Studies (177)

- Architecture (412)

- Fashion (201)

- Construction (132)

Diet & Nutrition

- Nutrition (347)

- Food Safety (153)

- World Cuisines & Food Culture (103)

- Economic Systems & Principles (922)

- Finance (672)

- Investment (559)

- Education Issues (768)

- Education Theories (743)

- Teacher Career (427)

Entertainment & Media

- Advertising (436)

- Documentaries (395)

- Media and Society (381)

Environment

- Environmental Studies (604)

- Ecology (586)

- Environmental Management (438)

Family, Life & Experiences

- Personal Experiences (354)

- Parenting (224)

- Marriage (171)

Health & Medicine

- Nursing (2891)

- Healthcare Research (2477)

- Public Health (1881)

- United States (1500)

- World History (1100)

- Criminology (1018)

- Criminal Law (895)

- Business & Corporate Law (709)

Linguistics

- Languages (199)

- Language Use (173)

- Language Acquisition (152)

- American Literature (2041)

- World Literature (1483)

- Poems (902)

- Philosophical Theories (494)

- Philosophical Concept (379)

- Philosophers (287)

Politics & Government

- Government (1504)

- International Relations (1137)

- Social & Political Theory (613)

- Psychological Issues (1100)

- Cognition and Perception (595)

- Behavior (573)

- Religion, Culture & Society (802)

- World Religions (382)

- Theology (352)

- Biology (809)

- Scientific Method (783)

- Chemistry (417)

- Sociological Issues (2107)

- Sociological Theories (1145)

- Gender Studies (887)

- Sports Culture (171)

- Sports Science (151)

- Sport Games (112)

Tech & Engineering

- Other Technology (601)

- Project Management (566)

- Technology Effect (525)

- Hospitality Industry (162)

- Trips and Tours (149)

- Tourism Destinations (122)

Transportation

- Air Transport (174)

- Transportation Industry (151)

- Land Transport (136)

- Terrorism (315)

- Modern Warfare (308)

- World War II (195)

Most Popular Essay Topics

Papers by essay type.

- Analytical Essay

- Application Essay

- Argumentative Essay

- Autobiography Essay

- Cause and Effect Essay

- Classification Essay

- Compare & Contrast Essay

- Creative Writing Essay

- Critical Essay

- Deductive Essay

- Definition Essay

- Descriptive Essay

- Evaluation Essay

- Exemplification Essay

- Explicatory Essay

- Exploratory Essay

- Expository Essay

- Inductive Essay

- Informative Essay

- Narrative Essay

- Opinion Essay

- Personal Essay

- Persuasive Essay

- Problem Solution Essay

- Proposal Essay

- Qualitative Research

- Quantitative Research

- Reflective Essay

- Response Essay

- Rhetorical Essay

- Satire Essay

- Self Evaluation Essay

- Synthesis Essay

Essays by Number of Pages

Papers by word count, view recent free essays, marketing: response to starbucks special fall drink.

- Subjects: Business , Marketing

Response to Starbucks Special Fall Drink

How do enzymes help healthcare providers check for diseases.

- Subjects: Health & Medicine , Public Health

Discussion: Taboo Words, Language

- Subjects: Importance of Language , Linguistics

Project Evaluation and Closure in Healthcare

- Subjects: Health & Medicine , Health IT

Autoimmunity: Impact on the Human Body

- Subjects: Health & Medicine , Immunology

The Documentary “Scared Straight 1999” by Bob Niemack

- Subjects: Documentaries , Entertainment & Media

Response to Johnson’s “Old Black Men” Poem

- Subjects: Literature , Poems

Strategic Leadership: Coaching Exercise with Reflection

- Subjects: Business , Leadership Styles

- Words: 1625

Torsion of Circular Sections: A Mechanical Experiment

- Subjects: Physics , Sciences

The 2026 FIFA World Cup in North America

- Subjects: Sport Events , Sports

- Words: 2318

Functional and Context Analysis

- Subjects: Sciences , Scientific Method

- Words: 3327

The Radio Frequency Identification System for Events

- Subjects: Business , Management

- Words: 2141

Discussion: The Goals of Early Education

- Subjects: Aspects of Education , Education

Creative Response to Reservation Dogs

- Subjects: Art , Film Studies

Discussion: Measures of Central Tendency

- Subjects: Sciences , Statistics

Business: Airbnb Company Analysis

- Subjects: Business , Company Analysis

Black Robe (1991) Movie Review

Healthcare rationing problematic solutions.

- Subjects: Health & Medicine , Nursing

Communication Objectives and Budget Requests

Frequently asked questions.

Places on our 2024 summer school are filling fast. Don’t miss out. Enrol now to avoid disappointment

- 40 Useful Words and Phrases for Top-Notch Essays

To be truly brilliant, an essay needs to utilise the right language. You could make a great point, but if it’s not intelligently articulated, you almost needn’t have bothered.

Developing the language skills to build an argument and to write persuasively is crucial if you’re to write outstanding essays every time. In this article, we’re going to equip you with the words and phrases you need to write a top-notch essay, along with examples of how to utilise them.

It’s by no means an exhaustive list, and there will often be other ways of using the words and phrases we describe that we won’t have room to include, but there should be more than enough below to help you make an instant improvement to your essay-writing skills.

If you’re interested in developing your language and persuasive skills, Oxford Royale offers summer courses at its Oxford Summer School , Cambridge Summer School , London Summer School , San Francisco Summer School and Yale Summer School . You can study courses to learn english , prepare for careers in law , medicine , business , engineering and leadership.

General explaining

Let’s start by looking at language for general explanations of complex points.

1. In order to

Usage: “In order to” can be used to introduce an explanation for the purpose of an argument. Example: “In order to understand X, we need first to understand Y.”

2. In other words

Usage: Use “in other words” when you want to express something in a different way (more simply), to make it easier to understand, or to emphasise or expand on a point. Example: “Frogs are amphibians. In other words, they live on the land and in the water.”

3. To put it another way

Usage: This phrase is another way of saying “in other words”, and can be used in particularly complex points, when you feel that an alternative way of wording a problem may help the reader achieve a better understanding of its significance. Example: “Plants rely on photosynthesis. To put it another way, they will die without the sun.”

4. That is to say

Usage: “That is” and “that is to say” can be used to add further detail to your explanation, or to be more precise. Example: “Whales are mammals. That is to say, they must breathe air.”

5. To that end

Usage: Use “to that end” or “to this end” in a similar way to “in order to” or “so”. Example: “Zoologists have long sought to understand how animals communicate with each other. To that end, a new study has been launched that looks at elephant sounds and their possible meanings.”

Adding additional information to support a point

Students often make the mistake of using synonyms of “and” each time they want to add further information in support of a point they’re making, or to build an argument . Here are some cleverer ways of doing this.

6. Moreover

Usage: Employ “moreover” at the start of a sentence to add extra information in support of a point you’re making. Example: “Moreover, the results of a recent piece of research provide compelling evidence in support of…”

7. Furthermore

Usage:This is also generally used at the start of a sentence, to add extra information. Example: “Furthermore, there is evidence to suggest that…”

8. What’s more

Usage: This is used in the same way as “moreover” and “furthermore”. Example: “What’s more, this isn’t the only evidence that supports this hypothesis.”

9. Likewise

Usage: Use “likewise” when you want to talk about something that agrees with what you’ve just mentioned. Example: “Scholar A believes X. Likewise, Scholar B argues compellingly in favour of this point of view.”

10. Similarly

Usage: Use “similarly” in the same way as “likewise”. Example: “Audiences at the time reacted with shock to Beethoven’s new work, because it was very different to what they were used to. Similarly, we have a tendency to react with surprise to the unfamiliar.”

11. Another key thing to remember

Usage: Use the phrase “another key point to remember” or “another key fact to remember” to introduce additional facts without using the word “also”. Example: “As a Romantic, Blake was a proponent of a closer relationship between humans and nature. Another key point to remember is that Blake was writing during the Industrial Revolution, which had a major impact on the world around him.”

12. As well as

Usage: Use “as well as” instead of “also” or “and”. Example: “Scholar A argued that this was due to X, as well as Y.”

13. Not only… but also

Usage: This wording is used to add an extra piece of information, often something that’s in some way more surprising or unexpected than the first piece of information. Example: “Not only did Edmund Hillary have the honour of being the first to reach the summit of Everest, but he was also appointed Knight Commander of the Order of the British Empire.”

14. Coupled with

Usage: Used when considering two or more arguments at a time. Example: “Coupled with the literary evidence, the statistics paint a compelling view of…”

15. Firstly, secondly, thirdly…

Usage: This can be used to structure an argument, presenting facts clearly one after the other. Example: “There are many points in support of this view. Firstly, X. Secondly, Y. And thirdly, Z.

16. Not to mention/to say nothing of

Usage: “Not to mention” and “to say nothing of” can be used to add extra information with a bit of emphasis. Example: “The war caused unprecedented suffering to millions of people, not to mention its impact on the country’s economy.”

Words and phrases for demonstrating contrast

When you’re developing an argument, you will often need to present contrasting or opposing opinions or evidence – “it could show this, but it could also show this”, or “X says this, but Y disagrees”. This section covers words you can use instead of the “but” in these examples, to make your writing sound more intelligent and interesting.

17. However

Usage: Use “however” to introduce a point that disagrees with what you’ve just said. Example: “Scholar A thinks this. However, Scholar B reached a different conclusion.”

18. On the other hand

Usage: Usage of this phrase includes introducing a contrasting interpretation of the same piece of evidence, a different piece of evidence that suggests something else, or an opposing opinion. Example: “The historical evidence appears to suggest a clear-cut situation. On the other hand, the archaeological evidence presents a somewhat less straightforward picture of what happened that day.”

19. Having said that

Usage: Used in a similar manner to “on the other hand” or “but”. Example: “The historians are unanimous in telling us X, an agreement that suggests that this version of events must be an accurate account. Having said that, the archaeology tells a different story.”

20. By contrast/in comparison

Usage: Use “by contrast” or “in comparison” when you’re comparing and contrasting pieces of evidence. Example: “Scholar A’s opinion, then, is based on insufficient evidence. By contrast, Scholar B’s opinion seems more plausible.”

21. Then again

Usage: Use this to cast doubt on an assertion. Example: “Writer A asserts that this was the reason for what happened. Then again, it’s possible that he was being paid to say this.”

22. That said

Usage: This is used in the same way as “then again”. Example: “The evidence ostensibly appears to point to this conclusion. That said, much of the evidence is unreliable at best.”

Usage: Use this when you want to introduce a contrasting idea. Example: “Much of scholarship has focused on this evidence. Yet not everyone agrees that this is the most important aspect of the situation.”

Adding a proviso or acknowledging reservations

Sometimes, you may need to acknowledge a shortfalling in a piece of evidence, or add a proviso. Here are some ways of doing so.

24. Despite this

Usage: Use “despite this” or “in spite of this” when you want to outline a point that stands regardless of a shortfalling in the evidence. Example: “The sample size was small, but the results were important despite this.”

25. With this in mind

Usage: Use this when you want your reader to consider a point in the knowledge of something else. Example: “We’ve seen that the methods used in the 19th century study did not always live up to the rigorous standards expected in scientific research today, which makes it difficult to draw definite conclusions. With this in mind, let’s look at a more recent study to see how the results compare.”

26. Provided that

Usage: This means “on condition that”. You can also say “providing that” or just “providing” to mean the same thing. Example: “We may use this as evidence to support our argument, provided that we bear in mind the limitations of the methods used to obtain it.”

27. In view of/in light of

Usage: These phrases are used when something has shed light on something else. Example: “In light of the evidence from the 2013 study, we have a better understanding of…”

28. Nonetheless

Usage: This is similar to “despite this”. Example: “The study had its limitations, but it was nonetheless groundbreaking for its day.”

29. Nevertheless

Usage: This is the same as “nonetheless”. Example: “The study was flawed, but it was important nevertheless.”

30. Notwithstanding

Usage: This is another way of saying “nonetheless”. Example: “Notwithstanding the limitations of the methodology used, it was an important study in the development of how we view the workings of the human mind.”

Giving examples

Good essays always back up points with examples, but it’s going to get boring if you use the expression “for example” every time. Here are a couple of other ways of saying the same thing.

31. For instance

Example: “Some birds migrate to avoid harsher winter climates. Swallows, for instance, leave the UK in early winter and fly south…”

32. To give an illustration

Example: “To give an illustration of what I mean, let’s look at the case of…”

Signifying importance

When you want to demonstrate that a point is particularly important, there are several ways of highlighting it as such.

33. Significantly

Usage: Used to introduce a point that is loaded with meaning that might not be immediately apparent. Example: “Significantly, Tacitus omits to tell us the kind of gossip prevalent in Suetonius’ accounts of the same period.”

34. Notably

Usage: This can be used to mean “significantly” (as above), and it can also be used interchangeably with “in particular” (the example below demonstrates the first of these ways of using it). Example: “Actual figures are notably absent from Scholar A’s analysis.”

35. Importantly

Usage: Use “importantly” interchangeably with “significantly”. Example: “Importantly, Scholar A was being employed by X when he wrote this work, and was presumably therefore under pressure to portray the situation more favourably than he perhaps might otherwise have done.”

Summarising

You’ve almost made it to the end of the essay, but your work isn’t over yet. You need to end by wrapping up everything you’ve talked about, showing that you’ve considered the arguments on both sides and reached the most likely conclusion. Here are some words and phrases to help you.

36. In conclusion

Usage: Typically used to introduce the concluding paragraph or sentence of an essay, summarising what you’ve discussed in a broad overview. Example: “In conclusion, the evidence points almost exclusively to Argument A.”

37. Above all

Usage: Used to signify what you believe to be the most significant point, and the main takeaway from the essay. Example: “Above all, it seems pertinent to remember that…”

38. Persuasive

Usage: This is a useful word to use when summarising which argument you find most convincing. Example: “Scholar A’s point – that Constanze Mozart was motivated by financial gain – seems to me to be the most persuasive argument for her actions following Mozart’s death.”

39. Compelling

Usage: Use in the same way as “persuasive” above. Example: “The most compelling argument is presented by Scholar A.”

40. All things considered

Usage: This means “taking everything into account”. Example: “All things considered, it seems reasonable to assume that…”

How many of these words and phrases will you get into your next essay? And are any of your favourite essay terms missing from our list? Let us know in the comments below, or get in touch here to find out more about courses that can help you with your essays.

At Oxford Royale Academy, we offer a number of summer school courses for young people who are keen to improve their essay writing skills. Click here to apply for one of our courses today, including law , business , medicine and engineering .

Comments are closed.

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Letter of Recommendation

What I’ve Learned From My Students’ College Essays

The genre is often maligned for being formulaic and melodramatic, but it’s more important than you think.

By Nell Freudenberger

Most high school seniors approach the college essay with dread. Either their upbringing hasn’t supplied them with several hundred words of adversity, or worse, they’re afraid that packaging the genuine trauma they’ve experienced is the only way to secure their future. The college counselor at the Brooklyn high school where I’m a writing tutor advises against trauma porn. “Keep it brief , ” she says, “and show how you rose above it.”

I started volunteering in New York City schools in my 20s, before I had kids of my own. At the time, I liked hanging out with teenagers, whom I sometimes had more interesting conversations with than I did my peers. Often I worked with students who spoke English as a second language or who used slang in their writing, and at first I was hung up on grammar. Should I correct any deviation from “standard English” to appeal to some Wizard of Oz behind the curtains of a college admissions office? Or should I encourage students to write the way they speak, in pursuit of an authentic voice, that most elusive of literary qualities?

In fact, I was missing the point. One of many lessons the students have taught me is to let the story dictate the voice of the essay. A few years ago, I worked with a boy who claimed to have nothing to write about. His life had been ordinary, he said; nothing had happened to him. I asked if he wanted to try writing about a family member, his favorite school subject, a summer job? He glanced at his phone, his posture and expression suggesting that he’d rather be anywhere but in front of a computer with me. “Hobbies?” I suggested, without much hope. He gave me a shy glance. “I like to box,” he said.

I’ve had this experience with reluctant writers again and again — when a topic clicks with a student, an essay can unfurl spontaneously. Of course the primary goal of a college essay is to help its author get an education that leads to a career. Changes in testing policies and financial aid have made applying to college more confusing than ever, but essays have remained basically the same. I would argue that they’re much more than an onerous task or rote exercise, and that unlike standardized tests they are infinitely variable and sometimes beautiful. College essays also provide an opportunity to learn precision, clarity and the process of working toward the truth through multiple revisions.

When a topic clicks with a student, an essay can unfurl spontaneously.

Even if writing doesn’t end up being fundamental to their future professions, students learn to choose language carefully and to be suspicious of the first words that come to mind. Especially now, as college students shoulder so much of the country’s ethical responsibility for war with their protest movement, essay writing teaches prospective students an increasingly urgent lesson: that choosing their own words over ready-made phrases is the only reliable way to ensure they’re thinking for themselves.

Teenagers are ideal writers for several reasons. They’re usually free of preconceptions about writing, and they tend not to use self-consciously ‘‘literary’’ language. They’re allergic to hypocrisy and are generally unfiltered: They overshare, ask personal questions and call you out for microaggressions as well as less egregious (but still mortifying) verbal errors, such as referring to weed as ‘‘pot.’’ Most important, they have yet to put down their best stories in a finished form.

I can imagine an essay taking a risk and distinguishing itself formally — a poem or a one-act play — but most kids use a more straightforward model: a hook followed by a narrative built around “small moments” that lead to a concluding lesson or aspiration for the future. I never get tired of working with students on these essays because each one is different, and the short, rigid form sometimes makes an emotional story even more powerful. Before I read Javier Zamora’s wrenching “Solito,” I worked with a student who had been transported by a coyote into the U.S. and was reunited with his mother in the parking lot of a big-box store. I don’t remember whether this essay focused on specific skills or coping mechanisms that he gained from his ordeal. I remember only the bliss of the parent-and-child reunion in that uninspiring setting. If I were making a case to an admissions officer, I would suggest that simply being able to convey that experience demonstrates the kind of resilience that any college should admire.

The essays that have stayed with me over the years don’t follow a pattern. There are some narratives on very predictable topics — living up to the expectations of immigrant parents, or suffering from depression in 2020 — that are moving because of the attention with which the student describes the experience. One girl determined to become an engineer while watching her father build furniture from scraps after work; a boy, grieving for his mother during lockdown, began taking pictures of the sky.

If, as Lorrie Moore said, “a short story is a love affair; a novel is a marriage,” what is a college essay? Every once in a while I sit down next to a student and start reading, and I have to suppress my excitement, because there on the Google Doc in front of me is a real writer’s voice. One of the first students I ever worked with wrote about falling in love with another girl in dance class, the absolute magic of watching her move and the terror in the conflict between her feelings and the instruction of her religious middle school. She made me think that college essays are less like love than limerence: one-sided, obsessive, idiosyncratic but profound, the first draft of the most personal story their writers will ever tell.

Nell Freudenberger’s novel “The Limits” was published by Knopf last month. She volunteers through the PEN America Writers in the Schools program.

How to Write a Research Paper

- Smodin Editorial Team

- Updated: May 17, 2024

Most students hate writing research papers. The process can often feel long, tedious, and sometimes outright boring. Nevertheless, these assignments are vital to a student’s academic journey. Want to learn how to write a research paper that captures the depth of the subject and maintains the reader’s interest? If so, this guide is for you.

Today, we’ll show you how to assemble a well-organized research paper to help you make the grade. You can transform any topic into a compelling research paper with a thoughtful approach to your research and a persuasive argument.

In this guide, we’ll provide seven simple but practical tips to help demystify the process and guide you on your way. We’ll also explain how AI tools can expedite the research and writing process so you can focus on critical thinking.

By the end of this article, you’ll have a clear roadmap for tackling these essays. You will also learn how to tackle them quickly and efficiently. With time and dedication, you’ll soon master the art of research paper writing.

Ready to get started?

What Is a Research Paper?

A research paper is a comprehensive essay that gives a detailed analysis, interpretation, or argument based on your own independent research. In higher-level academic settings, it goes beyond a simple summarization and includes a deep inquiry into the topic or topics.

The term “research paper” is a broad term that can be applied to many different forms of academic writing. The goal is to combine your thoughts with the findings from peer-reviewed scholarly literature.

By the time your essay is done, you should have provided your reader with a new perspective or challenged existing findings. This demonstrates your mastery of the subject and contributes to ongoing scholarly debates.

7 Tips for Writing a Research Paper

Often, getting started is the most challenging part of a research paper. While the process can seem daunting, breaking it down into manageable steps can make it easier to manage. The following are seven tips for getting your ideas out of your head and onto the page.

1. Understand Your Assignment

It may sound simple, but the first step in writing a successful research paper is to read the assignment. Sit down, take a few moments of your time, and go through the instructions so you fully understand your assignment.

Misinterpreting the assignment can not only lead to a significant waste of time but also affect your grade. No matter how patient your teacher or professor may be, ignoring basic instructions is often inexcusable.

If you read the instructions and are still confused, ask for clarification before you start writing. If that’s impossible, you can use tools like Smodin’s AI chat to help. Smodin can help highlight critical requirements that you may overlook.

This initial investment ensures that all your future efforts will be focused and efficient. Remember, thinking is just as important as actually writing the essay, and it can also pave the wave for a smoother writing process.

2. Gather Research Materials

Now comes the fun part: doing the research. As you gather research materials, always use credible sources, such as academic journals or peer-reviewed papers. Only use search engines that filter for accredited sources and academic databases so you can ensure your information is reliable.

To optimize your time, you must learn to master the art of skimming. If a source seems relevant and valuable, save it and review it later. The last thing you want to do is waste time on material that won’t make it into the final paper.

To speed up the process even more, consider using Smodin’s AI summarizer . This tool can help summarize large texts, highlighting key information relevant to your topic. By systematically gathering and filing research materials early in the writing process, you build a strong foundation for your thesis.

3. Write Your Thesis

Creating a solid thesis statement is the most important thing you can do to bring structure and focus to your research paper. Your thesis should express the main point of your argument in one or two simple sentences. Remember, when you create your thesis, you’re setting the tone and direction for the entire paper.

Of course, you can’t just pull a winning thesis out of thin air. Start by brainstorming potential thesis ideas based on your preliminary research. And don’t overthink things; sometimes, the most straightforward ideas are often the best.

You want a thesis that is specific enough to be manageable within the scope of your paper but broad enough to allow for a unique discussion. Your thesis should challenge existing expectations and provide the reader with fresh insight into the topic. Use your thesis to hook the reader in the opening paragraph and keep them engaged until the very last word.

4. Write Your Outline

An outline is an often overlooked but essential tool for organizing your thoughts and structuring your paper. Many students skip the outline because it feels like doing double work, but a strong outline will save you work in the long run.

Here’s how to effectively structure your outline.

- Introduction: List your thesis statement and outline the main questions your essay will answer.

- Literature Review: Outline the key literature you plan to discuss and explain how it will relate to your thesis.

- Methodology: Explain the research methods you will use to gather and analyze the information.

- Discussion: Plan how you will interpret the results and their implications for your thesis.

- Conclusion: Summarize the content above to elucidate your thesis fully.

To further streamline this process, consider using Smodin’s Research Writer. This tool offers a feature that allows you to generate and tweak an outline to your liking based on the initial input you provide. You can adjust this outline to fit your research findings better and ensure that your paper remains well-organized and focused.

5. Write a Rough Draft

Once your outline is in place, you can begin the writing process. Remember, when you write a rough draft, it isn’t meant to be perfect. Instead, use it as a working document where you can experiment with and rearrange your arguments and evidence.

Don’t worry too much about grammar, style, or syntax as you write your rough draft. Focus on getting your ideas down on paper and flush out your thesis arguments. You can always refine and rearrange the content the next time around.

Follow the basic structure of your outline but with the freedom to explore different ways of expressing your thoughts. Smodin’s Essay Writer offers a powerful solution for those struggling with starting or structuring their drafts.

After you approve the outline, Smodin can generate an essay based on your initial inputs. This feature can help you quickly create a comprehensive draft, which you can then review and refine. You can even use the power of AI to create multiple rough drafts from which to choose.

6. Add or Subtract Supporting Evidence

Once you have a rough draft, but before you start the final revision, it’s time to do a little cleanup. In this phase, you need to review all your supporting evidence. You want to ensure that there is nothing redundant and that you haven’t overlooked any crucial details.

Many students struggle to make the required word count for an essay and resort to padding their writing with redundant statements. Instead of adding unnecessary content, focus on expanding your analysis to provide deeper insights.

A good essay, regardless of the topic or format, needs to be streamlined. It should convey clear, convincing, relevant information supporting your thesis. If you find some information doesn’t do that, consider tweaking your sources.

Include a variety of sources, including studies, data, and quotes from scholars or other experts. Remember, you’re not just strengthening your argument but demonstrating the depth of your research.

If you want comprehensive feedback on your essay without going to a writing center or pestering your professor, use Smodin. The AI Chat can look at your draft and offer suggestions for improvement.

7. Revise, Cite, and Submit

The final stages of crafting a research paper involve revision, citation, and final review. You must ensure your paper is polished, professionally presented, and plagiarism-free. Of course, integrating Smodin’s AI tools can significantly streamline this process and enhance the quality of your final submission.

Start by using Smodin’s Rewriter tool. This AI-powered feature can help rephrase and refine your draft to improve overall readability. If a specific section of your essay just “doesn’t sound right,” the AI can suggest alternative sentence structures and word choices.

Proper citation is a must for all academic papers. Thankfully, thanks to Smodin’s Research Paper app, this once tedious process is easier than ever. The AI ensures all sources are accurately cited according to the required style guide (APA, MLA, Chicago, etc.).

Plagiarism Checker:

All students need to realize that accidental plagiarism can happen. That’s why using a Plagiarism Checker to scan your essay before you submit it is always useful. Smodin’s Plagiarism Checker can highlight areas of concern so you can adjust accordingly.

Final Submission

After revising, rephrasing, and ensuring all citations are in order, use Smodin’s AI Content Detector to give your paper one last review. This tool can help you analyze your paper’s overall quality and readability so you can make any final tweaks or improvements.

Mastering Research Papers

Mastering the art of the research paper cannot be overstated, whether you’re in high school, college, or postgraduate studies. You can confidently prepare your research paper for submission by leveraging the AI tools listed above.

Research papers help refine your abilities to think critically and write persuasively. The skills you develop here will serve you well beyond the walls of the classroom. Communicating complex ideas clearly and effectively is one of the most powerful tools you can possess.

With the advancements of AI tools like Smodin , writing a research paper has become more accessible than ever before. These technologies streamline the process of organizing, writing, and revising your work. Write with confidence, knowing your best work is yet to come!

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Published: 08 May 2024

Accurate structure prediction of biomolecular interactions with AlphaFold 3

- Josh Abramson ORCID: orcid.org/0009-0000-3496-6952 1 na1 ,

- Jonas Adler ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-9928-3407 1 na1 ,

- Jack Dunger 1 na1 ,

- Richard Evans ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-4675-8469 1 na1 ,

- Tim Green ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-3227-1505 1 na1 ,

- Alexander Pritzel ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-4233-9040 1 na1 ,

- Olaf Ronneberger ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-4266-1515 1 na1 ,

- Lindsay Willmore ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-4314-0778 1 na1 ,

- Andrew J. Ballard ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-4956-5304 1 ,

- Joshua Bambrick ORCID: orcid.org/0009-0003-3908-0722 2 ,

- Sebastian W. Bodenstein 1 ,

- David A. Evans 1 ,

- Chia-Chun Hung ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-5264-9165 2 ,

- Michael O’Neill 1 ,

- David Reiman ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-1605-7197 1 ,

- Kathryn Tunyasuvunakool ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8594-1074 1 ,

- Zachary Wu ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2429-9812 1 ,

- Akvilė Žemgulytė 1 ,

- Eirini Arvaniti 3 ,

- Charles Beattie ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-1840-054X 3 ,

- Ottavia Bertolli ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8578-3216 3 ,

- Alex Bridgland 3 ,

- Alexey Cherepanov ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-5227-0622 4 ,

- Miles Congreve 4 ,

- Alexander I. Cowen-Rivers 3 ,

- Andrew Cowie ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-4491-1434 3 ,

- Michael Figurnov ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-1386-8741 3 ,

- Fabian B. Fuchs 3 ,

- Hannah Gladman 3 ,

- Rishub Jain 3 ,

- Yousuf A. Khan ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-0201-2796 3 ,

- Caroline M. R. Low 4 ,

- Kuba Perlin 3 ,

- Anna Potapenko 3 ,

- Pascal Savy 4 ,

- Sukhdeep Singh 3 ,

- Adrian Stecula ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6914-6743 4 ,

- Ashok Thillaisundaram 3 ,

- Catherine Tong ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7570-4801 4 ,

- Sergei Yakneen ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7827-9839 4 ,

- Ellen D. Zhong ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6345-1907 3 ,

- Michal Zielinski 3 ,

- Augustin Žídek ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-0748-9684 3 ,

- Victor Bapst 1 na2 ,

- Pushmeet Kohli ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-7466-7997 1 na2 ,

- Max Jaderberg ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9033-2695 2 na2 ,

- Demis Hassabis ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2812-9917 1 , 2 na2 &

- John M. Jumper ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6169-6580 1 na2

Nature ( 2024 ) Cite this article

261k Accesses

1 Citations

1189 Altmetric

Metrics details

We are providing an unedited version of this manuscript to give early access to its findings. Before final publication, the manuscript will undergo further editing. Please note there may be errors present which affect the content, and all legal disclaimers apply.

- Drug discovery

- Machine learning

- Protein structure predictions

- Structural biology

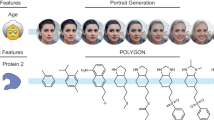

The introduction of AlphaFold 2 1 has spurred a revolution in modelling the structure of proteins and their interactions, enabling a huge range of applications in protein modelling and design 2–6 . In this paper, we describe our AlphaFold 3 model with a substantially updated diffusion-based architecture, which is capable of joint structure prediction of complexes including proteins, nucleic acids, small molecules, ions, and modified residues. The new AlphaFold model demonstrates significantly improved accuracy over many previous specialised tools: far greater accuracy on protein-ligand interactions than state of the art docking tools, much higher accuracy on protein-nucleic acid interactions than nucleic-acid-specific predictors, and significantly higher antibody-antigen prediction accuracy than AlphaFold-Multimer v2.3 7,8 . Together these results show that high accuracy modelling across biomolecular space is possible within a single unified deep learning framework.

You have full access to this article via your institution.

Similar content being viewed by others

Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold

De novo generation of multi-target compounds using deep generative chemistry

Augmenting large language models with chemistry tools

Author information.

These authors contributed equally: Josh Abramson, Jonas Adler, Jack Dunger, Richard Evans, Tim Green, Alexander Pritzel, Olaf Ronneberger, Lindsay Willmore

These authors jointly supervised this work: Victor Bapst, Pushmeet Kohli, Max Jaderberg, Demis Hassabis, John M. Jumper

Authors and Affiliations

Core Contributor, Google DeepMind, London, UK

Josh Abramson, Jonas Adler, Jack Dunger, Richard Evans, Tim Green, Alexander Pritzel, Olaf Ronneberger, Lindsay Willmore, Andrew J. Ballard, Sebastian W. Bodenstein, David A. Evans, Michael O’Neill, David Reiman, Kathryn Tunyasuvunakool, Zachary Wu, Akvilė Žemgulytė, Victor Bapst, Pushmeet Kohli, Demis Hassabis & John M. Jumper

Core Contributor, Isomorphic Labs, London, UK

Joshua Bambrick, Chia-Chun Hung, Max Jaderberg & Demis Hassabis

Google DeepMind, London, UK

Eirini Arvaniti, Charles Beattie, Ottavia Bertolli, Alex Bridgland, Alexander I. Cowen-Rivers, Andrew Cowie, Michael Figurnov, Fabian B. Fuchs, Hannah Gladman, Rishub Jain, Yousuf A. Khan, Kuba Perlin, Anna Potapenko, Sukhdeep Singh, Ashok Thillaisundaram, Ellen D. Zhong, Michal Zielinski & Augustin Žídek

Isomorphic Labs, London, UK

Alexey Cherepanov, Miles Congreve, Caroline M. R. Low, Pascal Savy, Adrian Stecula, Catherine Tong & Sergei Yakneen

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding authors

Correspondence to Max Jaderberg , Demis Hassabis or John M. Jumper .

Supplementary information

Supplementary information.

This Supplementary Information file contains the following 9 sections: (1) Notation; (2) Data pipeline; (3) Model architecture; (4) Auxiliary heads; (5) Training and inference; (6) Evaluation; (7) Differences to AlphaFold2 and AlphaFold-Multimer; (8) Supplemental Results; and (9) Appendix: CCD Code and PDB ID tables.

Reporting Summary

Rights and permissions.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Abramson, J., Adler, J., Dunger, J. et al. Accurate structure prediction of biomolecular interactions with AlphaFold 3. Nature (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-07487-w

Download citation

Received : 19 December 2023

Accepted : 29 April 2024

Published : 08 May 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-07487-w

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

Major alphafold upgrade offers boost for drug discovery.

- Ewen Callaway

Nature (2024)

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines . If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing: Translational Research newsletter — top stories in biotechnology, drug discovery and pharma.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Have a fresh pair of eyes give you some feedback. Don't allow someone else to rewrite your essay, but do take advantage of others' edits and opinions when they seem helpful. ( Bates College) Read your essay aloud to someone. Reading the essay out loud offers a chance to hear how your essay sounds outside your head.

Sample College Essay 2 with Feedback. This content is licensed by Khan Academy and is available for free at www.khanacademy.org. College essays are an important part of your college application and give you the chance to show colleges and universities your personality. This guide will give you tips on how to write an effective college essay.

Argumentative essays test your ability to research and present your own position on a topic. This is the most common type of essay at college level—most papers you write will involve some kind of argumentation. The essay is divided into an introduction, body, and conclusion: The introduction provides your topic and thesis statement

Essay writing process. The writing process of preparation, writing, and revisions applies to every essay or paper, but the time and effort spent on each stage depends on the type of essay.. For example, if you've been assigned a five-paragraph expository essay for a high school class, you'll probably spend the most time on the writing stage; for a college-level argumentative essay, on the ...

Mission. The Purdue On-Campus Writing Lab and Purdue Online Writing Lab assist clients in their development as writers—no matter what their skill level—with on-campus consultations, online participation, and community engagement. The Purdue Writing Lab serves the Purdue, West Lafayette, campus and coordinates with local literacy initiatives.

Making an all-state team → outstanding achievement. Making an all-state team → counting the cost of saying "no" to other interests. Making a friend out of an enemy → finding common ground, forgiveness. Making a friend out of an enemy → confront toxic thinking and behavior in yourself.

Harvard College Writing Center 2 Tips for Reading an Assignment Prompt When you receive a paper assignment, your first step should be to read the assignment prompt carefully to make sure you understand what you are being asked to do. Sometimes your assignment will be open-ended ("write a paper about anything in the course that interests you").

Tips for Reading an Assignment Prompt. Asking Analytical Questions. Thesis. Introductions. What Do Introductions Across the Disciplines Have in Common? Anatomy of a Body Paragraph. Transitions. Tips for Organizing Your Essay. Counterargument.

Tips for better writing. Ask for feedback on your paper from a classmate, writing center tutor, or instructor. Budget time to implement suggestions. Use spell-check and grammar-check to identify potential errors, and then manually check those flagged. Proofread the paper by reading it slowly and carefully aloud to yourself.

Step 2: Pick one of the things you wrote down, flip your paper over, and write it at the top of your paper, like this: This is your thread, or a potential thread. Step 3: Underneath what you wrote down, name 5-6 values you could connect to this. These will serve as the beads of your essay.

At IvyPanda, we pride ourselves on compiling one of the largest databases of free essay samples. It's big enough to cover most academic subjects and topics, and you can filter your search to find precisely what you need. There are plenty of paper types to choose from, including case studies, reviews, research essays, reports, and much more.

Revised on July 23, 2023. An essay outline is a way of planning the structure of your essay before you start writing. It involves writing quick summary sentences or phrases for every point you will cover in each paragraph, giving you a picture of how your argument will unfold. You'll sometimes be asked to submit an essay outline as a separate ...

College Essay Guy believes that every student should have access to the tools and guidance necessary to create the best application possible. That's why we're a one-for-one company, which means that for every student who pays for support, we provide free support to a low-income student. Learn more.

The following two sample papers were published in annotated form in the Publication Manual and are reproduced here as PDFs for your ease of use. The annotations draw attention to content and formatting and provide the relevant sections of the Publication Manual (7th ed.) to consult for more information.. Student sample paper with annotations (PDF, 5MB)

Writing 101: The 8 Common Types of Essays. Written by MasterClass. Last updated: Jun 7, 2021 • 3 min read. Whether you're a first-time high school essay writer or a professional writer about to tackle another research paper, you'll need to understand the fundamentals of essay writing before you put pen to paper and write your first sentence.

4. That is to say. Usage: "That is" and "that is to say" can be used to add further detail to your explanation, or to be more precise. Example: "Whales are mammals. That is to say, they must breathe air.". 5. To that end. Usage: Use "to that end" or "to this end" in a similar way to "in order to" or "so".

May 14, 2024. Most high school seniors approach the college essay with dread. Either their upbringing hasn't supplied them with several hundred words of adversity, or worse, they're afraid ...