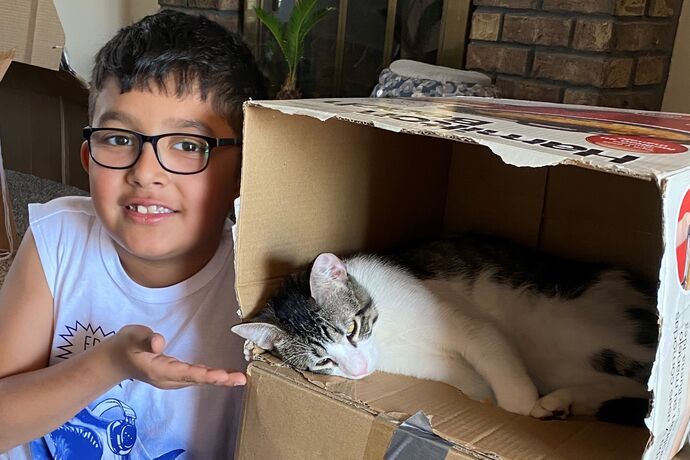

COVID-19 & School: Keeping Kids Safe At the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, students had their world turned upside down. Schools closed their doors as the virus spread quickly through communities. Since then, we have learned a lot. One of the biggest lessons: students learn best in-person, and many are also exposed to vital relationships, resources, and other experiences they need to thrive at school. A recent federal study found that for all students, reading and math scores are lower this year than they were in 2020. Scores were worst among students who were struggling before COVID. Daily attendance can make a big impact on long-term success and good health. Read on for ways to keep your child or teen healthy and in school. Vaccines & boostersThe AAP recommends COVID vaccination for everyone 6 months of age and older. Kids who are fully vaccinated are at a much lower risk of missing school due to being ill with COVID-19. Fully vaccinated kids don’t have to spend more time away from learning, friendships, sports and other activities. Remember that fully vaccinated people can still become infected and spread the virus to others, but less than if they were not vaccinated. If your child or teen has recovered from COVID illness, they should still get the vaccine to reduce the risk of getting sick again. Your child or teen should be up-to-date on all recommended vaccines, including flu, HPV, meningococcal, measles and other vaccines. Routine childhood and adolescent immunizations can be given with COVID-19 vaccines or in the days before and after. Getting caught up will avoid outbreaks of other illnesses that could keep your kids home from school. See Back to School: How to Help Your Child Have a Healthy Year for more information. Masks, testing & staying home when sickMasks are still a good idea. Although not required in many school districts, indoor masking is still beneficial. Masks help stop the spread of COVID—and other infections like the common cold or the flu . It is especially important to use well-fitting masks if your child is ineligible for the vaccine for medical reasons; immunocompromised; if a family member is at high risk; or there is a high rate of COVID in your community. Masks can help protect kids with immune compromise or disabilities from getting COVID, so they won’t have to miss school. Most children with medical conditions can wear face masks with practice, support and role-modeling by adults. Ask your pediatrician if: - you need help choosing a mask or personal protective equipment that offers the best fit and comfort based on a child’s medical or developmental needs or

- you have concerns that a mask cannot be worn and want to explore all options.

Planning for outbreaks. Right now, COVID variants and other viruses are circulating. Schools need to plan for outbreaks that may occur. People who have symptoms or are at high risk should be tested, following Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) guidelines . And if you get a negative result on an at-home COVID-19 antigen test, the Food and Drug Administration advises repeat testing. This is because tests can sometimes show false-negative results. COVID symptoms & what to do:✅

| If a child has , they should be picked up right away so they can isolate.

| ✅

| Keep your child home from school when they have symptoms so that others are not .

| ✅

| Follow the for details on when to get tested, how long to wear a mask and when to end isolation.

| ✅

| If your child had COVID within the past 90 days, follow the specific testing .

|

School-based support for studentsMany families will be recovering from the impacts of the pandemic for years to come. Here are some of the supports that families can access through school. - Resources for families affected by housing or food insecurity

- Access to high-speed internet and devices to complete schoolwork

- Support, testing and necessary accommodations for students with an Individualized Education Program (IEP) or chronic, high-risk medical conditions

- Emotional and behavioral support and resources for students with anxiety , distress, suicidal thoughts and other needs

If your child needs support, do not hesitate to talk with your pediatrician and school staff (including school nurses). They are there to help you explore options and connect your family with support and resources. More information- Back to School: Tips to Help Kids Have a Healthy Year

- COVID-19 Guidance for Safe Schools and Promotion of In-Person Learning (AAP.org)

The independent source for health policy research, polling, and news. Headed Back to School: A Look at the Ongoing Effects of COVID-19 on Children’s Health and Well-BeingElizabeth Williams and Patrick Drake Published: Aug 05, 2022 Children are now preparing to head back to school for the third time since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. Schools are expected to return in-person this fall, with most experts now agreeing the benefits of in-person learning outweigh the risks of contracting COVID-19 for children. Though children are less likely than adults to develop severe illness, the risk of contracting COVID-19 remains, with some children developing symptoms of long COVID following diagnosis. COVID-19 vaccines provide protection, and all children older than 6 months are now eligible to be vaccinated. However, vaccination rates have stalled and remain low for younger children. At this time, only a few states have vaccine mandates for school staff or students, and no states have school mask mandates, though practices can vary by school district. Emerging COVID-19 variants, like the Omicron subvariant BA.5 that has recently caused a surge in cases, may pose new risks to children and create challenges for the back-to-school season. Children may also continue to face challenges due to the ongoing health, economic, and social consequences of the pandemic. Children have been uniquely impacted by the pandemic, having experienced this crisis during important periods of physical, social, and emotional development, with some experiencing the loss of loved ones. While many children have gained health coverage due to federal policies passed during the pandemic, public health measures to reduce the spread of the disease also led to disruptions or changes in service utilization and increased mental health challenges for children. This brief examines how the COVID-19 pandemic continues to affect children’s physical and mental health, considers what the findings mean for the upcoming back-to-school season, and explores recent policy responses. A companion KFF brief explores economic effects of the pandemic and recent rising costs on households with children. We find households with children have been particularly hard hit by loss of income and food and housing insecurity, which all affect children’s health and well-being. Children’s Health Care Coverage and UtilizationDespite job losses that threatened employer-sponsored insurance coverage early in the pandemic, uninsured rates have declined likely due to federal policies passed during in the pandemic and the safety net Medicaid and CHIP provided. Following growth in the children’s uninsured rate from 2017 to 2019, data from the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) show that the children’s uninsured rate held steady from 2019 to 2020 and then fell from 5.1% in 2020 to 4.1% in 2021. Just released quarterly NHIS data show the children’s uninsured rate was 3.7% in the first quarter of 2022, which was below the rate in the first quarter of 2021 (4.6%) but a slight uptick from the fourth quarter of 2021 (3.5%), though none of these differences are statistically significant. Administrative data show that children’s enrollment in Medicaid and CHIP increased by 5.2 million enrollees, or 14.7%, between February 2020 and April 2022 (Figure 1). Provisions in the Families First Coronavirus Response Act (FFCRA) require states to provide continuous coverage for Medicaid enrollees until the end of the month in which the public health emergency (PHE) ends in order to receive enhanced federal funding. Children have missed or delayed preventive care during the pandemic, with a third of adults still reporting one or more children missed or delayed a preventative check-up in the past 12 months (Figure 2). However, the share missing or delaying care is slowly declining, with the share from April 27 – May 9, 2022 (33%) down 3% from almost a year earlier (July 21 – August 2, 2021) according to KFF analysis of the Household Pulse Survey . Adults in households with income less than $25,000 were significantly more likely to have a child that missed, delayed, or skipped a preventive appointment in the past 12 months compared to households with income over $50,000. These data are in line with findings from another study that found households reporting financial hardship were significantly more likely to report missing or delaying children’s preventive visits compared to those not reporting hardships. Hispanic households and households of other racial/ethnic groups were also significantly more likely to have a child that missed, delayed, or skipped a preventive appointment in the past 12 months compared to White households (based on race of the adult respondent). Telehealth helped to provide access to care, but children with special health care needs and those in rural areas continued to face barriers. Overall, telehealth utilization soared early in the pandemic, but has since declined and has not offset the decreases in service utilization overall. While preventative care rates have increased since early in the pandemic, many children likely still need to catch up on missed routine medical care. One study found almost a quarter of parents reported not catching-up after missing a routine medical visit during the first year of the pandemic. The pandemic may have also exacerbated existing challenges accessing needed care and services for children with special health care needs , and low-income patients or patients in rural areas may have experienced barriers to accessing health care via telehealth . The pandemic has also led to declines in children’s routine vaccinations, blood lead screenings, and vision screenings. The CDC reported vaccination coverage of all state-required vaccines declined by 1% in the 2020-2021 school year compared to the previous year, and some public health leaders note COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy may be spilling over to routine child immunizations. The CDC also report ed 34% fewer U.S. children had blood lead level testing from January-May 2020 compared to the same period in 2019. Further, data suggest declines in lead screenings during the pandemic may have exacerbated underlying gaps and disparities in early identification and intervention for lower-income households and children of color. Additionally, many children rely on in-school vision screenings to identity vision impairments, and some children went without vision checks while schools managed COVID-19 and turned to remote learning. These screenings are important for children in order to identify problems early; without treatment some conditions can worsen or lead to more serious health complications. The pandemic has also led to difficulty accessing and disruptions in dental care. Data from the National Survey of Children’s Health (NSCH) show the share of children reporting seeing a dentist or other oral health provider or having a preventive dental visit in the past 12 months declined from 2019 to 2020, the first year of the pandemic (Figure 3). The share of children reporting their teeth are in excellent or very good conditions also declined from 2019 (80%) to 2020 (77%); the share of children reporting no oral health problems also declined but the change was not statistically significant. Recently released preliminary data for Medicaid/CHIP beneficiaries under age 19 shows steep declines in service utilization early in the pandemic, with utilization then rebounding to a varying degree depending on the service type . Child screening services have rebounded to pre-PHE levels while blood lead screenings and dental services rates remain below per-PHE levels. Telehealth utilization mirrors national trends, increasing rapidly in April 2020 and then beginning to decline in 2021. When comparing the PHE period (March 2020 – January 2022) to the pre-PHE period (January 2018 – February 2020) overall, the data show child screening services and vaccination rates declined by 5% (Figure 4). Blood lead screening services and dental services saw larger declines when comparing the PHE period to before the PHE, declining by 12% and 18% respectively among Medicaid/CHIP children. Children’s Mental Health ChallengesChildren’s mental health challenges were on the rise even before the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. A recent KFF analysis found the share of adolescents experiencing anxiety and/or depression has increased by one-third from 2016 (12%) to 2020 (16%), although rates in 2020 were similar to 2019. Rates of anxiety and/or depression were more pronounced among adolescent females and White and Hispanic adolescents. A separate survey of high school students in 2021 found that lesbian, gay, or bisexual (LGB) students were more likely to report persistent feelings of sadness and hopelessness than their heterosexual peers. In the past few years, adolescents have experienced worsened emotional health, increased stress, and a lack of peer connection along with increasing rates of drug overdose deaths, self-harm, and eating disorders. Prior to the pandemic, there was also an increase in suicidal thoughts from 14% in 2009 to 19% in 2019. The pandemic may have worsened children’s mental health or exacerbated existing mental health issues among children . The pandemic caused disruptions in routines and social isolation for children, which can be associated with anxiety and depression and can have implications for mental health later in life. A number of studies show an increase in children’s mental health needs following social isolation due to the pandemic, especially among children who experience adverse childhood experiences (ACEs). KFF analysis found the share of parents responding that adolescents were experiencing anxiety and/or depression held relatively steady from 2019 (15%) to 2020 (16%), the first year of the pandemic. However, the KFF COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor on perspectives of the pandemic at two years found six in ten parents say the pandemic has negatively affected their children’s schooling and over half saying the same about their children’s mental health. Researchers also note it is still too early to fully understand the impact of the pandemic on children’s mental health. The past two years have also seen much economic turmoil, and research has shown that as economic conditions worsen, children’s mental health is negatively impacted. Further, gun violence continues to rise and may lead to negative mental health impacts among children and adolescents. Research suggests that children and adolescents may experience negative mental health impacts, including symptoms of anxiety, in response to school shootings and gun-related deaths in their communities . Access and utilization of mental health care may have also worsened during the pandemic. Preliminary data for Medicaid/CHIP beneficiaries under age 19 finds utilization of mental health services during the PHE declined by 23% when compared to prior to the pandemic (Figure 4); utilization of substance use disorder services declined by 24% for beneficiaries ages 15-18 for the same time period. The data show utilization of mental health services remains below pre-PHE levels and has seen the smallest improvement compared to other services utilized by Medicaid/CHIP children. Telehealth has played a significant role in providing mental health and substance use services to children early in the pandemic, but has started to decline . The pandemic may have widened existing disparities in access to mental health care for children of color and children in low-income households. NSCH data show 20% of children with mental health needs were not receiving needed care in 2020, with the lowest income children less likely to receive needed mental health services when compared to higher income groups (Figure 5). Children’s Health and COVID-19While less likely than adults to develop severe illness, children can contract and spread COVID-19 and children with underlying health conditions are at an increased risk of developing severe illness . Data through July 28, 2022 show there have been over 14 million child COVID-19 cases, accounting for 19% of all cases. Among Medicaid/CHIP enrollees under age 19, 6.4% have received a COVID-19 diagnosis through January 2022. Pediatric hospitalizations peaked during the Omicron surge in January 2022, and children under age 5, who were not yet eligible for vaccination, were hospitalized for COVID-19 at five times the rate during the Delta surge. Some children who tested positive for the virus are now facing long COVID . A recent meta-analysis found 25% of children and adolescents had ongoing symptoms following COVID-19 infection, and finds the most common symptoms for children were fatigue, shortness of breath, and headaches, with other long COVID symptoms including cognitive difficulties, loss of smell, sore throat, and sore eyes. Another report found a larger share of children with a confirmed COVID-19 case experienced a new or recurring mental health diagnosis compared to children who did not have a confirmed COVID-19 case. However, researchers have noted it can be difficult to distinguish long COVID symptoms to general pandemic-associated symptoms. In addition, a small share of children are experiencing multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C), a serious condition associated with COVID-19 that has impacted almost 9,000 children . A lot of unknowns still surround long COVID in children; it is unclear how long symptoms will last and what impact they will have on children’s long-term health. COVID-19 vaccines were recently authorized for children between the ages of 6 months and 5 years, making all children 6 months and older eligible to be vaccinated against COVID-19. Vaccination has already peaked for children under the age of 5, and is far below where 5-11 year-olds were at the same point in their eligibility. As of July 20, approximately 544,000 children under the age of 5 (or approximately 2.8%) had received at least one COVID-19 vaccine dose. Vaccinations for children ages 5-11 have stalled, with just 30.3% have been fully vaccinated as of July 27 compared to 60.2% of those ages 12-17. Schools have been important sites for providing access as well as information to help expand vaccination take-up among children, though children under 5 are not yet enrolled in school, limiting this option for younger kids. A recent KFF survey finds most parents of young children newly eligible for a COVID-19 vaccine are reluctant to get them vaccinated, including 43% who say they will “definitely not” do so. Some children have experienced COVID-19 through the loss of one or more family members due to the virus. A study estimates that, as of June 2022, over 200,000 children in the US have lost one or both parents to COVID-19. Another study found children of color were more likely to experience the loss of a parent or grandparent caregiver when compared to non-Hispanic White children. Losing a parent can have long term impacts on a child’s health, increasing their risk of substance abuse, mental health challenges, poor educational outcomes , and early death . There have been over 1 million COVID-19 deaths in the US, and estimates indicate a 17.5% to 20% increase in bereaved children due to COVID-19, indicating an increased number of grieving children who may need additional supports as they head back to school. Looking AheadChildren will be back in the classroom this fall but may continue to face health risks due to their or their teacher’s vaccination status and increasing transmission due to COVID-19 variants. New, more transmissible COVID-19 variants continue to emerge, with the most recent Omicron subvariant BA.5 driving a new wave of infections and reinfections among those who have already had COVID-19. This could lead to challenges for the back-to-school season, especially among young children whose vaccination rates have stalled. Schools, parents, and children will likely continue to catch up on missed services and loss of instructional time in the upcoming school year. Schools are likely still working to address the loss of instructional time and drops in student achievement due to pandemic-related school disruptions. Further, many children with special education plans experienced missed or delayed services and loss of instructional time during the pandemic. Students with special education plans may be entitled to compensatory services to make up for lost skills due to pandemic related service disruptions, and some children, such as those with disabilities related to long COVID, may be newly eligible for special education services. To address worsening mental health and barriers to care for children, several measures have been taken or proposed at the state and federal level. Many states have recently enacted legislation to strengthen school based mental health systems, including initiatives such as from hiring more school-based providers to allowing students excused absences for mental health reasons. In July 2022, 988 – a federally mandated crisis number – launched, providing a single three-digit number for individuals in need to access local and state funded crisis centers, and the Biden Administration released a strategy to address the national mental health crisis in May 2022, building on prior actions. Most recently, in response to gun violence, the Bipartisan Safer Communities Act was signed into law and allocates funds towards mental health, including trauma care for school children. The unwinding of the PHE and expiring federal relief may have implications for children’s health coverage and access to care. The American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) extended eligibility to ACA health insurance subsides for people with incomes over 400% of poverty and increased the amount of assistance for people with lower incomes. However, these subsidies are set to expire at the end of this year without further action from Congress, which would increase premium payments for 13 million Marketplace enrollees. In addition, provisions in the FFCRA providing continuous coverage for Medicaid enrollees will expire with the end of the PHE. Millions of people, including children, could lose coverage when the continuous enrollment requirement ends if they are no longer eligible or face administrative barriers during the process despite remaining eligible. There will likely be variation across states in how many people are able to maintain Medicaid coverage, transition to other coverage, or become uninsured. Lastly, there have also been several policies passed throughout the pandemic to provide financial relief for families with children, but some benefits, like the expanded Child Tax Credit, have expired and the cost of household items is rising, increasing food insecurity and reducing the utility of benefits like SNAP. - Coronavirus (COVID-19)

- Coronavirus

Also of Interest- A Look at the Economic Effects of the Pandemic for Children

- Recent Trends in Mental Health and Substance Use Concerns Among Adolescents

- Mental Health and Substance Use Considerations Among Children During the COVID-19 Pandemic

- COVID-19 Vaccination Rates Among Children Under 5 Have Peaked and Are Decreasing Just Weeks Into Their Eligibility

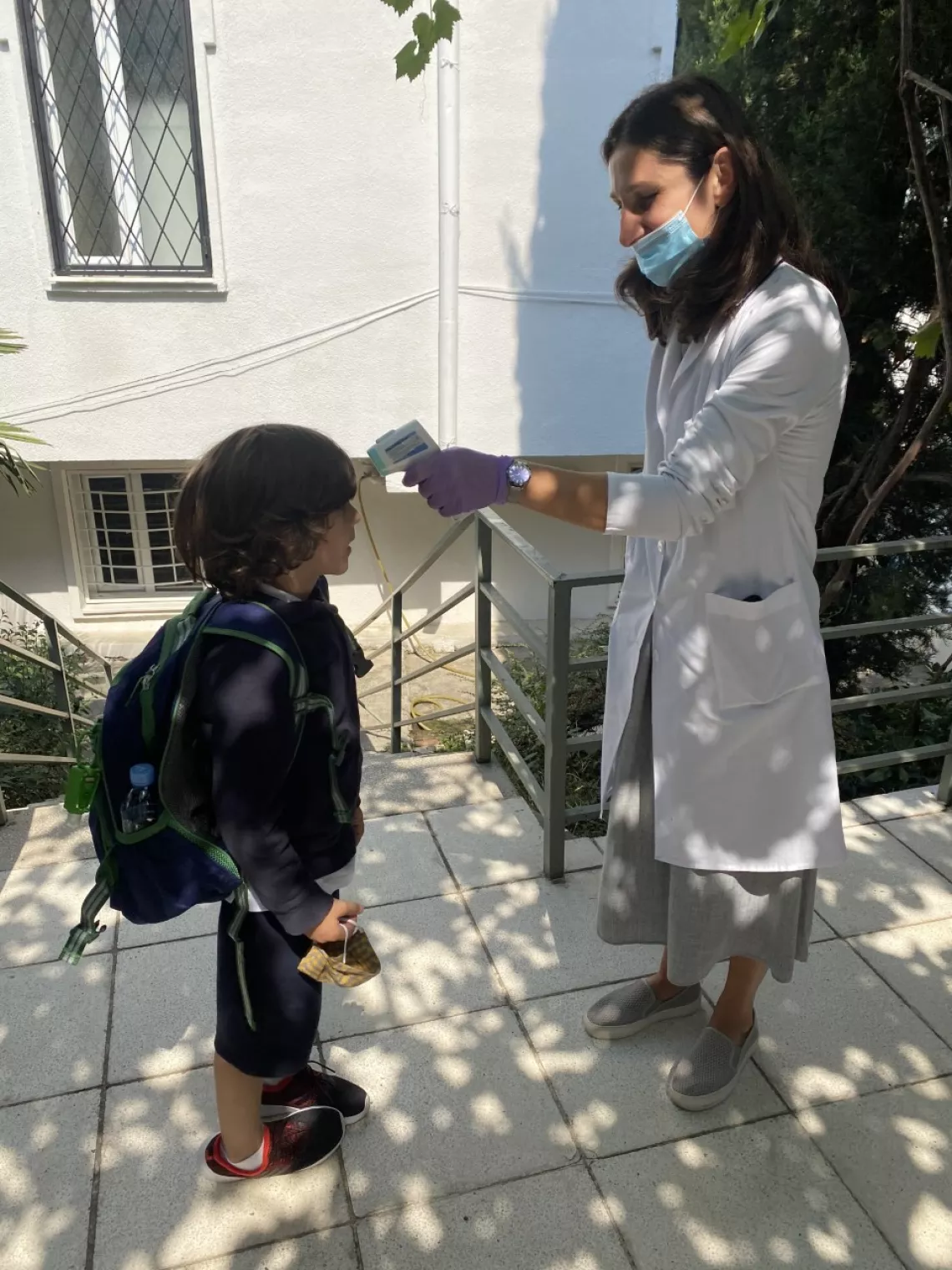

Mission: Recovering Education in 2021 THE CONTEXTThe COVID-19 pandemic has caused abrupt and profound changes around the world. This is the worst shock to education systems in decades, with the longest school closures combined with looming recession. It will set back progress made on global development goals, particularly those focused on education. The economic crises within countries and globally will likely lead to fiscal austerity, increases in poverty, and fewer resources available for investments in public services from both domestic expenditure and development aid. All of this will lead to a crisis in human development that continues long after disease transmission has ended. Disruptions to education systems over the past year have already driven substantial losses and inequalities in learning. All the efforts to provide remote instruction are laudable, but this has been a very poor substitute for in-person learning. Even more concerning, many children, particularly girls, may not return to school even when schools reopen. School closures and the resulting disruptions to school participation and learning are projected to amount to losses valued at $10 trillion in terms of affected children’s future earnings. Schools also play a critical role around the world in ensuring the delivery of essential health services and nutritious meals, protection, and psycho-social support. Thus, school closures have also imperilled children’s overall wellbeing and development, not just their learning. It’s not enough for schools to simply reopen their doors after COVID-19. Students will need tailored and sustained support to help them readjust and catch-up after the pandemic. We must help schools prepare to provide that support and meet the enormous challenges of the months ahead. The time to act is now; the future of an entire generation is at stake. THE MISSIONMission objective: To enable all children to return to school and to a supportive learning environment, which also addresses their health and psychosocial well-being and other needs. Timeframe : By end 2021. Scope : All countries should reopen schools for complete or partial in-person instruction and keep them open. The Partners - UNESCO , UNICEF , and the World Bank - will join forces to support countries to take all actions possible to plan, prioritize, and ensure that all learners are back in school; that schools take all measures to reopen safely; that students receive effective remedial learning and comprehensive services to help recover learning losses and improve overall welfare; and their teachers are prepared and supported to meet their learning needs. Three priorities:1. All children and youth are back in school and receive the tailored services needed to meet their learning, health, psychosocial wellbeing, and other needs. Challenges : School closures have put children’s learning, nutrition, mental health, and overall development at risk. Closed schools also make screening and delivery for child protection services more difficult. Some students, particularly girls, are at risk of never returning to school. Areas of action : The Partners will support the design and implementation of school reopening strategies that include comprehensive services to support children’s education, health, psycho-social wellbeing, and other needs. Targets and indicators | | | | Enrolment rates for each level of school return to pre-COVID level, disaggregated by gender. | | | Proportion of schools providing any services to meet children’s health and psychosocial needs, by level of education. | or |

2. All children receive support to catch up on lost learning. Challenges : Most children have lost substantial instructional time and may not be ready for curricula that were age- and grade- appropriate prior to the pandemic. They will require remedial instruction to get back on track. The pandemic also revealed a stark digital divide that schools can play a role in addressing by ensuring children have digital skills and access. Areas of action : The Partners will (i) support the design and implementation of large-scale remedial learning at different levels of education, (ii) launch an open-access, adaptable learning assessment tool that measures learning losses and identifies learners’ needs, and (iii) support the design and implementation of digital transformation plans that include components on both infrastructure and ways to use digital technology to accelerate the development of foundational literacy and numeracy skills. Incorporating digital technologies to teach foundational skills could complement teachers’ efforts in the classroom and better prepare children for future digital instruction. | | | | Proportion of schools offering remedial education by level of education. | or | | Proportion of schools offering instruction to develop children’s social-emotional skills by level of education. | or | | Proportion of schools incorporating digital technology to teach foundational literacy and numeracy skills, by level of education. | or |

While incorporating remedial education, social-emotional learning, and digital technology into curricula by the end of 2021 will be a challenge for most countries, the Partners agree that these are aspirational targets that they should be supporting countries to achieve this year and beyond as education systems start to recover from the current crisis. 3. All teachers are prepared and supported to address learning losses among their students and to incorporate digital technology into their teaching. Challenges : Teachers are in an unprecedented situation in which they must make up for substantial loss of instructional time from the previous school year and teach the current year’s curriculum. They must also protect their own health in school. Teachers will need training, coaching, and other means of support to get this done. They will also need to be prioritized for the COVID-19 vaccination, after frontline personnel and high-risk populations. School closures also demonstrated that in addition to digital skills, teachers may also need support to adapt their pedagogy to deliver instruction remotely. Areas of action : The Partners will advocate for teachers to be prioritized in COVID-19 vaccination campaigns, after frontline personnel and high-risk populations, and provide capacity-development on pedagogies for remedial learning and digital and blended teaching approaches. | | | | Teachers are on priority list for vaccination. | | | Proportion of teachers that have been offered training or other support for remedial education and social emotional learning, by level of education. | or Global Teachers Campus (link to come) | | Proportion of teachers that have been offered training or other support for delivering remote instruction, by level of education. | or Global Teachers Campus (link to come) |

Country level actions and global supportUNESCO, UNICEF, and World Bank are joining forces to support countries to achieve the Mission, leveraging their expertise and actions on the ground to support national efforts and domestic funding. Country Level Action 1. Mobilize team to support countries in achieving the three priorities The Partners will collaborate and act at the country level to support governments in accelerating actions to advance the three priorities. 2. Advocacy to mobilize domestic resources for the three priorities The Partners will engage with governments and decision-makers to prioritize education financing and mobilize additional domestic resources. Global level action 1. Leverage data to inform decision-making The Partners will join forces to conduct surveys; collect data; and set-up a global, regional, and national real-time data-warehouse. The Partners will collect timely data and analytics that provide access to information on school re-openings, learning losses, drop-outs, and transition from school to work, and will make data available to support decision-making and peer-learning. 2. Promote knowledge sharing and peer-learning in strengthening education recovery The Partners will join forces in sharing the breadth of international experience and scaling innovations through structured policy dialogue, knowledge sharing, and peer learning actions. The time to act on these priorities is now. UNESCO, UNICEF, and the World Bank are partnering to help drive that action. Last Updated: Mar 30, 2021 - (BROCHURE, in English) Mission: Recovering Education 2021

- (BROCHURE, in French) Mission: Recovering Education 2021

- (BROCHURE, in Spanish) Mission: Recovering Education 2021

- (BLOG) Mission: Recovering Education 2021

- (VIDEO, Arabic) Mission: Recovering Education 2021

- (VIDEO, French) Mission: Recovering Education 2021

- (VIDEO, Spanish) Mission: Recovering Education 2021

- World Bank Education and COVID-19

- World Bank Blogs on Education

This site uses cookies to optimize functionality and give you the best possible experience. If you continue to navigate this website beyond this page, cookies will be placed on your browser. To learn more about cookies, click here .  Forever Changed: A Timeline of How COVID Upended SchoolsEducators’ two-year journey with the coronavirus pandemic started as early as Feb. 25, 2020, with a blunt call for school and district leaders, staff, and families to prepare for the coming disruption: “You should ask your children’s schools about their plans for school dismissals or school closures,” Nancy Messonnier, an official at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, said during a press briefing that day. “Ask about plans for teleschool.” By the end of March 2020: - COVID-19 had been declared a global pandemic by The World Health Organization,

- Education Week had recorded the first death of an educator linked to the virus,

- School buildings faced a near-total shutdown nationwide, and

- Congress had passed the first of three federal financial aid packages, the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act, which included money to help schools with emergency costs related to mitigating the spread of the virus and supporting students.

In that same two-year timespan, educators were elevated as pandemic heroes—and later vilified as obstructionists for not opening school doors and classrooms quickly enough. Demands were just as vehement to keep schools closed and to deliver innovative processes, technology, and safeguards to keep students safe and learning productivity high. This timeline captures how policymakers, federal agencies, two presidents, teachers’ unions, public health officials, and others wrestled with the protocols needed to get students back in schools learning and thriving, amid illness, deaths, three viral variants, and unremitting public pressure. Coronavirus may yet graduate from pandemic to endemic status this calendar year, eased by vaccines, additional treatments, and immunity from prior infections. But the educational obstacles in the pandemic’s wake leave schools with a steep climb to boost academic growth and support the mental and emotional health issues that many students and educators carry from the pandemic. Staff writers Evie Blad, Catherine Gewertz, Sarah Schwartz, Madeline Will, senior digital news specialist Hyon-Young Kim, and associate art director Vanessa Solis contributed to this article. COVID-19 has shaken the education landscape. Here are key milestones.Click each tab below to explore educators’ two-year journey with the COVID-19 pandemic. Jan. 19, 2020: The first recorded COVID-19 illness in the United StatesAn urgent care clinic in Snohomish County, Wash., records the nation’s first COVID-19 case.  Feb. 25, 2020: CDC warns schools to prepare for ‘teleschool’ disruptionsNancy Messonnier, an official at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, holds a press briefing with a message to prepare for inevitable disruption in school routines because of COVID-19. Feb. 27, 2020: Coronavirus scare prompts a school to shut downThe first school shuts down because of COVID-19, the disease caused by the novel coronavirus. Bothell High School in Washington state closes for two days for disinfection after an employee’s relative gets sick and is tested for the coronavirus. March 11, 2020: The World Health Organization declares coronavirus a global pandemicBy month’s end, principals, superintendents, and then governors act to stop the virus’ spread and close schools across the nation . March 23, 2020: New York educator an early casualtyDez-Ann Romain, 36, a Brooklyn principal, is one of the first K-12 educators in the United States to die from COVID-19 . Romain was the principal of the 190-student Brooklyn Democracy Academy in Brooklyn’s Brownsville neighborhood. New York City—which was an early epicenter of the virus—had closed schools to students on March 16, but teachers and principals continued to come to work for a few days after the closure.  March 26, 2020: USDA waives school nutrition rules, making it easier for schools to serve grab-and-go mealsUnder a U.S. Department of Agriculture waiver, parents can pick up “grab-and-go” school meals from school nutrition workers , even if their children aren’t present. “Typically, children would need to be present to receive a meal through USDA’s child nutrition programs,” then-U.S. Secretary of Agriculture Sonny Perdue says in a memo. “However, USDA recognizes that this may not be practical during the current COVID-19 outbreak.”  March 27, 2020: Congress passes the CARES Act, with $13.2 billion for states and local school districtsThe first COVID assistance package, the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act, emerges from Congress as a response to the early days of the pandemic, as schools rack up emergency costs for remote learning and personal protective equipment. Read more: Everything You Need to Know About Schools and COVID Relief Funds April 2020: Educators’ stress skyrockets due to the pandemicIn the rush to distance-learning, the nation’s teachers scramble to manage unfamiliar technologies, to retrofit—or reinvent—their lessons, and to juggle emails, texts, and calls from principals, parents, and students. Read more: Exhausted and Grieving: Teaching During the Coronavirus Crisis  April 2, 2020: All states are excused from federally-required statewide testingThe Education Department excuses every state from administering standardized tests that are required by federal law , something that hasn’t happened since the federal government first required states to test students’ achievement in 1994. May 20, 2020: CDC issues first guidance on reopening schoolsEducation groups pressure federal agencies to provide clarity about how to safely operate schools as they begin to make plans for both academic and logistical issues associated with starting the new school year. The CDC offers guidance on issues like disinfecting surfaces, reducing students’ contact with peers on buses and in the classroom, and daily health checks. It also recommends that common areas like lunchrooms be closed. Read more: When Schools Reopen, All Staff Should Wear Masks, New CDC Guidance Says  May 2020: Nearly all states say school buildings would be closed for the rest of the academic yearForty-eight states, four U.S. territories, the District of Columbia, and the Department of Defense Education Activity have by this time ordered or recommended school building closures for the rest of the academic year, affecting at least 50.8 million public school students. By early May, 80 percent of teachers report in an EdWeek Research Center survey interacting with the majority of their students daily or weekly, either online or in-person. Read more: Map: Coronavirus and School Closures in 2019-2020 June 2020: Schools find creative ways to mark graduation day for Class of 2020From car parades and quarantine diplomas made of toilet paper to signs on lawns and across entire streets, schools take many different approaches to celebrating the Class of 2020. Read more: COVID-19’s Disproportionate Toll on Class of 2020 Graduates  Back to Top ⬆ July 8, 2020: Trump threatens to withhold federal funding to schools that do not reopenPresident Donald Trump says his administration “may cut off funding” for schools that don’t resume face-to-face instruction , and points to CDC reopening guidelines that he calls impractical and expensive. The next day, U.S. Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos says that rather than “pulling funding from education,” her department supports the idea that students in places where schools do not reopen should be able to take federal money and use it where they can get instruction in-person. July 23, 2020: CDC stresses the importance of in-person learningThe CDC revises its school guidance to stress the importance of in-person learning. About “7.1 million kids get their mental health service at schools,” then-CDC Director Dr. Robert Redfield says in a congressional hearing. “They get their nutritional support from their schools. We’re seeing an increase in drug use disorder as well as suicide in adolescent individuals. I do think that it’s really important to realize it’s not public health versus the economy about school reopening.” Read more: The Pandemic Is Causing Widespread Emotional Trauma. Schools Must Be Ready to Help July 28, 2020: AFT moves to delay reopening of schools to protect teachersAmerican Federation of Teachers President Randi Weingarten says the union would pursue various tactics, including lawsuits and strikes, to keep schools from reopening without adequate safety precautions. “If authorities don’t protect the safety and health of those we represent and those we serve ... nothing is off the table—not advocacy or protests, negotiations, grievances or lawsuits, or, if necessary and authorized by a local union, as a last resort, safety strikes,” she says at a remote meeting of the national teachers’ union’s biennial convention.  July 28, 2020: Fauci says there are still unanswered questions about how the coronavirus is spreadDr. Anthony Fauci, the top U.S. infectious disease expert, tells educators in a virtual town hall that when it comes to reopening school buildings for in-person instruction, there are still many unanswered questions about how the coronavirus is spread by children, and that teachers will be “part of the experiment.” His comment sparks uproar on Twitter from teachers, who say they didn’t sign up to be part of such an experiment. Fall 2020: Many districts opt to start the school year in remote learningSome districts provide hybrid instruction, and some are able to offer full in-person instruction to all students. Read more: School Districts’ Reopening Plans: A Snapshot  Sept. 2020: Federal vaccine distribution plan says states should prioritize teachers and school employees, alongside other critical workersNot only does a new federal plan identify teachers and school employees as priority recipients of a vaccine , it also identifies U.S. schools as a crucial partner for administering the shots. December 2020: Teachers in line for the first doses of COVID vaccinesA wave of states announce that they will prioritize teachers and school employees in the ir vaccine distribution plan s, but most states—if not all—are still focused on administering vaccines to health-care workers and long-term care residents.  Dec. 27, 2020: Second federal COVID aid package provides $54.3 billionThe Coronavirus Response and Relief Supplemental Appropriations Act allocates more than $190 billion to help schools pay for tutors and cleaning supplies and millions of computing devices.  January 2021: Biden calls for unified efforts to reopen schools within the first 100 days of his administrationA 200-page federal plan and executive orders from newly elected President Joe Biden call for “sustained and coordinated” efforts to reopen schools for in-person instruction, with the cooperation of states and new resources, guidance, and data. Read more: Biden Launches New Strategy to Combat COVID-19, Reopen Schools February 2021: In Chicago and other big cities, teachers’ unions influence school reopening plansThe Chicago teachers’ union reaches a reopening deal with the district that includes a delay that gives the district more time to vaccinate teachers, which was a sticking point in weeks of negotiations. Many big-city unions are in heated negotiations with their districts around this time period.  February 2021: CDC releases new guidelines as core part of Biden’s plan to reopen schools“I want to be clear,” CDC Director Rochelle Walenksy says. “With the release of this operational strategy, CDC is not mandating that schools reopen. CDC is simply providing schools with a long-needed road map for how to do so safely under different levels of disease in the community.” March 2021: Vaccine access speeds up for teachersThe vaccine landscape for teachers shifts dramatically the day after Biden announce s a federal push to get all teachers their first dose of the COVID-19 vaccine by the end of March. Read more: Vaccine Access Speeds Up for Teachers After Biden’s Declaration  March 2021: Schools get federal aid for homeless studentsThe American Rescue Plan, the third major package of federal COVID aid, includes $800 million for homeless children and youth (allocated through states), which is money that wasn’t set aside specifically for them in the two previous relief deals. March 19, 2021: CDC eases recommendations for social distancing in classroomsThe CDC issues recommendations saying 3 feet of space between students who are wearing masks is a sufficient safeguard in most classroom situations . Many educators and policymakers viewed the agency’s previous recommendation of 6 feet of space as a major hurdle to a full return to in-person school.  Early April 2021: Vaccines become available for teensStates begin to open vaccine eligibility to those 16 and up , a watershed moment for the pandemic. By early April 2021, two-thirds of teachers tell the EdWeek Research Center they’d been fully vaccinated against COVID-19. By the end of the month, that figure had shot up to 80 percent. April 20, 2021: USDA waives school meal regulations through June 2022After extending waivers of school meal regulations several times, the USDA says the flexibilities will last until June 2022 . The waivers will also allow schools to continue distributing meals to students who are learning remotely without red tape that can make it logistically difficult to do so. May 10, 2021: Pfizer vaccine approved for 12- to 15- year-oldsThe approval is a major development in the overall campaign to vaccinate more Americans and help ensure healthy and safe operations of middle and high schools in the pandemic. Schools begin opening their buildings to facilitate getting school-age children vaccinated. May 13, 2021: American Federation of Teachers says schools must reopen five days a week in fall“We can and we must reopen schools in the fall for in-person teaching, learning, and support,” AFT President Randi Weingarten says in virtual speech. “ And keep them open—fully and safely five days a week .” Graduation 2021: Health worries and financial instability impact college-going decisionsEdWeek Research Center surveys comparing the class of 2020 and 2021 graduates find that 74 percent of 2020 graduates who were planning on attending a four-year college followed through with their plans and ended up attending a university. Only 62 percent of the class of 2021 were able to do the same. Among students who had planned to attend a two-year college in 2021, only 44 percent succeeded in doing so, compared with 57 percent of graduates who wished to enter a two-year degree program in 2020.  July 9, 2021: CDC says students, educators, and staff should still wear masksThe CDC advises that all students, visitors, and staff should wear masks in schools , regardless of their vaccination status and maintain “layered mitigation strategies,” like handwashing, regular testing, contact tracing to identify threats of exposure to the virus, and cancelling certain extracurricular activities in high-risk areas. The recommendations also put a priority on getting schools reopened for in-person learning. Read more: Unvaccinated Students, Adults Should Continue Wearing Masks in Schools, CDC Says July 2021: Biden administration calls on school districts to host pop-up vaccination clinicsThe Biden administration pushes to increase the number of vaccinations for kids 12 and older as the Delta variant of the virus intensifies worries that the upcoming school year will be disrupted just like the last two were.  August 2021: First state requires all teachers and school staff get vaccinated or undergo weekly testingCalifornia requires all teachers and school staff to either get vaccinated for COVID-19 or undergo weekly testing—the first state in the nation to issue such a sweeping requirement. August 2021: Teachers face pressure to get vaccines, or face disciplineOregon and Washington states require teachers to get fully vaccinated or face discipline, which could include termination. A handful of school districts, including Chicago and Los Angeles, impose similar mandates. California, Connecticut, New Mexico, New Jersey, and Hawaii—as well as several more school districts, including Washington, D.C.—give teachers the choice between getting vaccinated or undergoing regular testing. Sept. 24, 2021: CDC director approves booster shots for teachers, reversing panel’s decisionHours after a federal vaccine advisory committee votes against recommending a booster shot for essential workers, including K-12 school staff, Rochelle Walensky, the director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention overrule s the decision . Read more: With Vaccine Mandates on the Rise, Some Teachers May Face Discipline Fall 2021: More schools adopt a ‘test-to-stay’ policyMany schools adopt a “test-to-stay” program to let students who test negative for COVID-19 keep attending school even if they have been in close contact with someone who tests positive. The policy is intended to minimize disruption to in-person learning.  Oct. 1, 2021: California announces statewide COVID vaccine mandate for studentsCalifornia’s first-in-the-nation requirement for students to get vaccinated against COVID also makes it easier for families to opt out than existing state rules that require vaccines for routine illnesses, like measles, as a condition of school attendance. The mandate will be phased in as vaccines win full approval from the Food and Drug Administration for different age groups. Read more: California Is Mandating COVID Vaccines for Kids. Will Other States Follow?  Nov. 2, 2021: Children as young as 5 can get vaccinesThe CDC approves the Pfizer-BioNTech pediatric vaccine for emergency use authorization for children as young as five. The White House develops a distribution plan, highlighting ways schools can contribute to the effort by vaccinating children on campus in partnership with local health providers as well as combating vaccine misinformation that may prevent families from getting vaccines. Read more: All K-12 Students Can Now Get the COVID-19 Vaccine. Here’s What It Means for Schools November 2021: Staffing shortages put a crimp on mandatory vaccine pushDistricts start backing off consequences for vaccine mandates due to staffing shortages.  Dec. 27, 2021: CDC shortens its recommendations for quarantiningThe CDC shorten s its recommendations for the length of isolation and quarantine periods . Under the new guidance, people who test positive for COVID-19 must isolate for five days, instead of the previously recommended 10, and then, if they have no symptoms or their symptoms are resolving, can resume normal activities wearing a mask for at least five more days. January 2022: Omicron variant causes concerns after winter breakAs COVID-19 cases rise due to the more-contagious Omicron variant, some districts push back their return to school after winter break, or pivot to remote instruction for one or two weeks. Read more: For Anxious Teachers, Omicron ‘Feels Like Walking Into a Trap’ Feb. 25, 2022: CDC relaxes mask guidelines for schoolsThe CDC releases guidance that universal masking in public settings, including schools, is only recommended in areas with high risk of serious illness or strained health-care resources .  March 15, 2022: Schools warn of hunger, higher costs when federal meal waivers endCongress passes a spending bill that does not include flexibility for school meal programs, alarming child hunger and education groups . Federal waivers that let schools feed all students free meals throughout the COVID-19 pandemic will expire this summer, leaving school nutrition directors braced as supply chain issues and spiking costs eat up their already tight budgets.  March 31, 2022: Federal survey of high school students sheds light on mental health strugglesHigh school students experienced mental health challenges during the pandemic including hopelessness, substance abuse, and suicidal thoughts or behaviors, the CDC finds. But those who felt close to people at school or reported strong virtual connections with family and peers were less likely to report such concerns. Read more: Teen Mental Health During COVID: What New Federal Data Reveal  Sign Up for The Savvy PrincipalEdweek top school jobs.  Sign Up & Sign In  An official website of the United States government The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site. The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely. - Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now . - Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Front Psychol