Murdered women: A history of ‘honour’ crimes

Throughout history, women have been held responsible for upholding the ‘honour’ of their families – often with deadly consequences.

Listen to this story:

On a hot summer day in late May 1994, I drove to an eastern suburb of Jordan’s capital, Amman, to investigate the reported murder of a 16-year-old schoolgirl by her own brother.

Keep reading

‘as if she had never existed’: the graveyards for murdered women, jordan: man shoots and kills three sisters ‘over family dispute’, justice by scooter: amman’s famed female crime reporter, defending pakistani women against honour killings.

With limited information, questions roiled my mind as I drove up the hill towards the neighbourhood. Why had this girl’s life been cut short by her brother? What had her final thoughts been?

My questions would soon be partially answered by a man who was walking through the neighbourhood when I arrived. “Yes, I know why she was killed,” he answered calmly as if talking about the weather: “She was raped by one of her brothers and another sibling murdered her to cleanse his family’s honour.”

I asked him again if what he was saying was really true.

“Yes, it is true. That is why she was killed,” the man answered me, before ushering me to the house where the murder took place.

The same “justification” was used by the girl’s uncles when I sat with them to discuss the murder. Her name was Kifaya (“enough”) they told me. “She seduced her brother to sleep with her and she had to die for that,” they said.

That sentence rang in my head throughout my career as a senior reporter at the Jordan Times and as an activist on this topic.

A few months later, I was assigned to cover court hearings on homicides in Jordan. Again, I came across dozens of stories of women who had been murdered by their male relatives for reasons related to so-called “family honour”. Some of these cases I investigated, including Kifaya’s.

To my surprise at that time, the majority of perpetrators would get away with little more than a slap on the wrist. Their sentences would range from three months to two years in prison.

But in Kifaya’s case, the court rejected the “rape excuse that was uttered by her brother and handed him a 15-year prison term for manslaughter”, as I wrote in my report for the Jordan Times. It was an unusually harsh sentence for its time.

But that sentence, like most of those relating to “honour” crimes, was later cut in half because the victim’s family dropped their legal claims against the defendant, who was, of course, also a family member. While sentencing has gradually become more severe over the years, it is still possible in Jordan for defendants to have their sentences cut in half if the victim’s family drops the charges.

Locked up for being a victim

My career has exposed me to another unjust consequence of women being threatened with harm or murder by their family members. In Jordan, dozens of women used to be locked up in prison, without charge, for indefinite periods in “administrative detention”. In other words, the state was imprisoning them to stop them from being killed or harmed. The logic, surely, should have been to imprison the person who threatened them. But that is not what happened.

I discovered that this practice also took place in Yemen, when I went there to visit a women’s prison for my work in the late 1990s. Thankfully, Jordan no longer locks women up for being at risk of an “honour” crime – they are now sent to a safe house known as “Dar Amneh” instead, but this cruel practice only came to an end in 2018.

My reporting and activism on this topic began with Kifaya’s story. And my resolve only grew with each new story I heard. I took it upon myself to become the voice of those women who were unable to tell their own stories and to examine and expose the root causes of these types of murders.

If a wife violates her duty, she shall be ‘devoured by dogs’

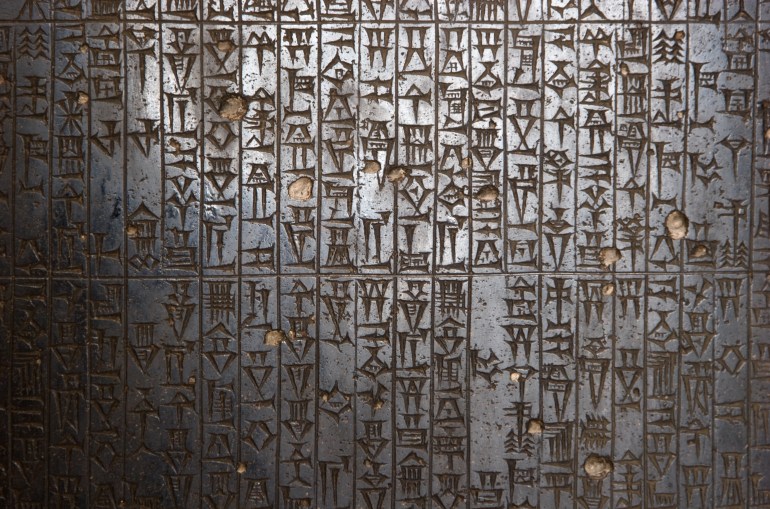

Violence against women has been documented throughout history. Most of the ancient civilisations – among them the Assyrian, Roman and Sumerian – had penal codes that condemned “women adulterers and their partners” while allowing men to publicly have mistresses with little or no punishment at all.

The late Dr Vivian Fox, a US university professor who specialised in family and women’s history, argued that Judeo-Christian religious ideas, Greek philosophy and the Common Law legal code have all influenced modern Western society’s views and treatment of women.

“All three traditions have, by and large, assumed patriarchy as natural – that is male domination stemming from the view of male superiority,” she wrote in the Journal of International Women’s Studies. “As part of the culture perpetuated by these ideologies, violence towards women was seen as a natural expression of male dominance.

“Ordained by the Gods, supported by the priests, implemented by the law, women came to accept and to psychologically internalise compliance as necessary. Violence towards women in all its forms has and still thrives in such an environment.”

Matthew A Goldstein, a historian who has studied honour killings in the Roman Empire, explains how at the root of such murders – and the concept of “honour” itself – was the desire of men to ensure the children their wives bore were their own. By placing the responsibility for this “honour” on the shoulders of women, those women could be more easily controlled and, therefore, men could be more certain of the progeny of their children. In essence, the simplest way to ensure that men produced offspring of their own lineage was the suppression and control of the sexuality of their female mates.

Fathers were in control of the life and death of their daughters. Once a woman married, her father’s authority over her was transferred to her husband. Adultery by women was considered a felony under Roman law – punishable by death – and the state prosecuted family members and others for not taking action against adulterous female relatives by confiscating their property, according to Goldstein.

The Romans were not the first to enshrine this concept of “honour” – as borne by women – in law. The Hammurabi Code, which was written in 1780 BC and made law by the Babylonian king, Hammurabi, who reigned in Mesopotamia (modern-day Iraq) from 1792 to 1750 BC, was also severe when it came to penalising women adulterers. Their punishment was to be tied up and thrown into the river to die. There was no punishment at all for male adulterers in this Code.

The Laws of Manu of ancient India were written around 200 BC. They stated: “Though destitute of virtue or seeking pleasure elsewhere, or devoid of good qualities, yet a husband must be constantly worshipped as a god by a faithful wife.” On the other hand: “If a wife, proud of the greatness of her relatives or [her own] excellence, violates the duty which she owes to her lord, the king shall cause her to be devoured by dogs in a place frequented by many.”

In the 1st century AD, chastity, virginity, and the “good behaviour” of women were highly prized across Europe. According to Jacob Burckhardt’s book, The Civilization of the Renaissance in Italy, for example, German adulteresses were flogged and buried alive.

“It was common throughout Europe for men to murder their wives because they suspected infidelity and to kill their daughters because they eloped. It was also common for brothers to kill their sisters because they refused to marry the man their family had chosen for them,” Burckhardt writes.

The situation remained the same in Europe during the Middle Ages.

In 1536, Anne Boleyn, the second wife of King Henry VIII and queen of England in the 1530s, was executed on charges including adultery, witchcraft, incest and conspiracy against the king. The charges against her were highly suspect. One admission of adultery from her music teacher, Marc Smeaton, was extracted under torture. It is widely accepted by historians today that all Anne was really guilty of was failing to produce a male heir – she gave birth to one daughter and suffered multiple miscarriages, at least one of a male foetus – and having a strong personality. Therefore, the charges against her were likely to have been concocted by the king or his aides as a way to get rid of a troublesome woman and make way for a more compliant consort – Jane Seymour, who was one of Anne’s own ladies-in-waiting – who might be able to produce a son.

The late Egyptian activist and feminist Nawal el-Saadawi pointed out in much of her research that murdering and burning women in the West for adultery was a common practice in the 14th century as well.

In the Dark Ages, “wise and smart women” were considered sorceresses by the Church in Europe and were killed, burned or locked in hospitals for the “mentally ill”, Saadawi explained. The real reason for these heinous acts, she argued, was that male priests were afraid of losing power. Women with knowledge of plants and other methods of treating the sick, offered an alternative to the priests’ use of “holy water and God’s powers”.

There were other reasons why a woman in Europe might find herself murdered by her relatives. In 1546 in Italy, Isabella Morra, the 25-year-old daughter of the baron of Favale, was murdered by her brothers. The reason: She had exchanged poetry with a Spanish nobleman, Don Diego Sandoval de Castro, the governor of Cosenza. Isabella had already been locked away in the family castle before this because her love of poetry was deemed unseemly for a woman.

In Europe, penal codes that punished women for adultery but excused it in men continued throughout the centuries. In France in the early 1800s, four jurists drafted the Napoleonic Code, which placed women under male guardianship, explained Georgina Dopico Black in her book, Perfect Wives, Other Women: Adultery and Inquisition in Early Modern Spain.

The Napoleonic Code stipulated that wives had to obey their husbands, while husbands had the power to send them to solitary confinement for adultery and to divorce them – but not the other way round. If a man caught his wife in the act of adultery and killed her, he was excused by law, Black wrote.

The depiction of women as evil and immoral was also reflected in the world of the arts. In her book, The Second Sex , French philosopher, novelist, and essayist Simone de Beauvoir argued that popular European culture in the 1880s frequently portrayed women as sinners. De Beauvoir argued that plays and operas based on this theme often gave communities the right to punish evil women since their “misbehaviour is offensive to the entire community”.

Meanwhile, Judy Mabro points out in her book, Veiled Half Truths: Western Travellers’ Perceptions of Middle Eastern Women, that in the Victorian era between 1837 and 1901, images of women in popular culture were frequently those of women who were “hysterical, mad and filled with mad diseases”.

Moving closer to our own time, in 1996, Jordanian scholar and feminist, Lama Abu Odeh tackled so-called “honour” killing. In particular, she addressed the issue of virginity, stating: “The hymen becomes the socio-physical sign that guarantees virginity and gives the woman a stamp of respectability and virtue.”

Abu Odeh, who examined several court verdicts pertaining to “honour” crimes in Jordan, pointed out that a woman might suffer violence if she was spotted conversing with a man behind a fence or seen leaving the car of a man and that, in both instances, “the woman is seen as having jeopardised not her vaginal hymen, but her physical and social one. She moved with a body and in a space where she is not supposed to be”.

‘Honour’ as a magic word

In 2002, former UN special rapporteur on violence against women, Radhika Coomaraswamy, described the term “honour” as a “magic word that can be used to cloak the most heinous of crimes”.

Much later, the UN Office on Drugs and Crime conducted a global study on homicide that was gender-related to women and girls for the year 2017.

The report indicated that a total of 87,000 women were intentionally killed that year, including 50,000 who were killed by intimate partners or family members, meaning that 137 women across the world are killed by a member of their own family every day.

Figures from the UN Population Fund from 2000 show that more than 5,000 women are killed annually for reasons related to “family honour”, although experts estimated the number to be much higher even back then.

In my own research, I found that many “honour” killings were not reported at all or were classified as suicide or accidents.

Signs of change

In Jordan, things started to take a positive turn in the late 2000s. It had been a long time coming.

In 1998, shortly after I had won the Reebok Human Rights Award for my activism and reporting on honour crimes, a Jordanian pharmacist approached me to suggest we form a group to tackle the problem at the grassroots level. I was excited by the idea. We emailed our friends and urged them to spread the word. The National Jordanian Committee to Eliminate So-called Crimes of Honor was founded the following year. We decided to hold our meetings in our houses. At the first one, 30 people turned up.

Within a few weeks, we had formed a core group of seven women and four men who would meet on a weekly basis to discuss the best means of raising awareness about the issue of “honour” killings and lobbying for the abolition of all laws that discriminate against women and afford the perpetrators of such crimes leniency.

We prepared a petition and collected 15,000 signatures. For the first time, Jordanians signed their names and gave their full contact details on a petition. In the past, people had always been reluctant to sign a petition for fear of being harassed by security agencies. The country had been under martial law from the 1950s to the 1980s, during which time political parties were banned and people were forbidden to distribute pamphlets or circulate petitions. Although these laws had ended in the late 1980s, people remained cautious for some time afterwards.

Our activities were also aimed at high school and university students because we hoped they would take up the cause. And they did.

It was clear that the public mood was in our favour. We used to take the petitions everywhere we went. We would encourage the (mostly male) waiting staff at restaurants and cafés we visited to sign, and most would after hearing our arguments. If we saw the chefs, we would also ask them to sign too. On one occasion, I saw a street cleaner and approached him with a pen. He grabbed it quickly and told me: “Of course I want to sign this petition. It is against our religion to kill a human being.”

On another occasion, we walked into a shop and identified ourselves. The shopkeeper replied, “I’ve been waiting for you,” and signed.

Of course, some people refused – either because the topic did not interest them or because they believed “honour” killings were justified.

We divided ourselves into teams and toured the governorates to talk to people from all walks of life. In general, we found most wanted to learn more and many signed.

Soon, the local dailies and other media outlets started reporting on our activities. With that came harassment from some conservative MPs and religious figures who accused us of being Western and Zionist agents whose ultimate goal was to destroy the morals of Jordanian families.

Columns and editorials were written attacking us. And one conservative member of the lower house of Parliament, Mahmoud Kharabsheh, told me in person: “Women adulterers cause a great threat to our society because they are the main reason that such acts [of adultery] happen. If men do not find women with whom to commit adultery, then they will become good on their own.”

He lobbied against us in the lower house and circulated a petition among his colleagues a few days before the reform of Article 340 – which allows reduced sentences for men who kill their wives or female members of their family for committing adultery – was due to be debated in November 1999. He criticised the government for allowing the debate, calling it an “invitation to obscenity”.

The great Article 340 debate

I was present in Parliament on the day Article 340 was debated. Kharabsheh was the first to speak. “This draft is one of the most dangerous legislation being reviewed by the House, because it is related to our women and society,” he told the assembly.

There were defenders of the proposal to abolish Article 340. Nash’at Hamarneh, a leftist from Madaba – a majority Christian town about an hour from the capital, Amman – argued that Jordanian society could not develop unless women were given their full rights. “This article has become a sword over the necks of our women. [Furthermore] we have never once heard of a man being killed in the name of honour,” he said, amidst vehement indignance from lawmakers.

At the end of the session, when it was time to vote, I took a peek from the balcony to see who might vote in favour of reforming the law. I was expecting a count of hands and for the names of the deputies and how they had voted to be called out. But, despite almost a dozen deputies speaking out against Article 340, one deputy asked: “Why are we wasting more time?”

The speaker asked who was against the proposed bill to reform the law. The majority of the deputies waved their hands and that was that. A decision had been taken and the bill had been rejected without even the pretence of a count of hands. Article 340 remains law to this day.

It was a blow, but during our activism, we also received signs of support from high-level officials, people who believed in the cause, and some columnists. The late Iyad Qatan, secretary-general of the Ministry of Information at the time, was a courageous man who helped us gain access to documents that facilitated our work. He also helped free some of our petition signature-collectors from police stations on a few occasions.

On another occasion, in February 2000, we organised a public march led by Prince Ali – the half brother of King Abdullah – and Prince Ghazi bin Mohammad to Parliament to demand an end to such crimes and the abolition of discriminatory laws, including Article 340.

Afterwards, Prince Ali posted on an internet chatroom: “Contrary to some opinions, the demonstrations were organised and carried out without any governmental or institutional help.

“In fact, the prime minister [Abdur-Raouf Rawabdeh] stood against it. He contacted Jordan TV and the papers and asked them not to publicise the demonstration. When we moved to the government, the prime minister was supposed to meet us. However, he sneaked out before we arrived…

“In reality, forces both within the government and Parliament had never intended the bill [to amend Article 340] to pass in the first place… the reason behind it is not about the article itself but fear that the article will lead to reforms…reforms that would hold them accountable, loosen their grip on power, by allowing people to move creatively and freely in progressing our country.

“It is an old game where parliament and government oppose each other outwardly to give the image of democracy at the expense of the people and our progress, and meanwhile innocents are murdered and our country remains economically stagnant.”

More and more people started to speak out against these crimes and the unjust laws that allowed them to continue.

They casually said they would ‘kill their sisters’

In the past, many Jordanian men would casually say they would kill their sisters if they did anything perceived to have damaged their family’s “honour”.

But for the past 10 years, I have found that men’s reactions to my lectures and to the topic, in general, have undergone a major shift. Many men have become much more interested in being part of the solution.

And there have been small changes along the way. In 2003, for example, a royal committee recommended changes to Article 98 of the Jordanian Penal Code that had been used as leeway for perpetrators of such murders by their lawyers. It stated: “Whoever commits a crime in a fit of fury which is the result of an unjustifiable and dangerous act committed by the victim, benefits from a mitigating excuse.”

The committee recommended that the principle be disallowed as an excuse for crimes against women unless a husband caught his wife in the act of adultery and it extended this right to women who caught their husbands in an act of adultery.

Lenient sentences against men accused of honour crimes have continued, of course. In 2014, for example, a court revoked the death sentence of a man convicted of shooting and killing his daughter, sentencing him to 10 years in prison instead. The daughter, who was in her late 20s, had left her marital home for several days, the court was told, and her father wanted to “cleanse the family’s honour”. His sentence was reduced after the family agreed to drop the charges against him.

But the changes that have taken place have filled me with hope. Still, the fight continues and demands dedication, commitment and patience.

Shafilea Ahmed, a victim of honour abuse

- Relationships and Family

- British Crime

When a person vanishes into thin air, and looks likely to have been killed, the police have to maintain the most cool-headed professionalism to resolve the mystery, even as the victim’s family deal with the emotional devastation. But what if those very loved ones turn out to be culpable?

The word ‘ideology’ is key here, presenting a thorny issue for police and social services in the UK, who must tackle the scourge of honour killings while also being sensitive to the religious and cultural context of this ideology. They have to tread carefully while investigating a community – most often Muslim – that’s already marginalized and subject to racism.

Shafilea’s parents, who claimed she’d run away, were savvy enough to weaponize the issues of race and religion, claiming they were being unfairly suspected because of being Muslim. It was only years later that they were convicted thanks to the testimony of another daughter, Shafilea’s sister Alesha, who told police the squalid story of how an argument over Shafilea’s ‘Westernised’ choice of clothes led to her parents holding her down and choking her to death with a plastic bag, right there in the living room in front of their other children.

A woman is killed every three days by a man in the UK

As is so often the case with honour killings, Shafilea had already tried to extract herself from the toxic household, running away from home and even telling social services that she was being beaten at home. Yet, like other victims of honour-based violence, she later downplayed the issue when speaking to a social worker, presumably because of her ingrained loyalty to her family. It must have been a hellish psychological tug-of-war – the pressure to conform and be loyal, versus the sheer desperation that led her at one point to drink from a bottle of bleach (her parents told hospital staff it was an accident, and it wasn’t investigated further).

The agonizing inability to escape a situation which you know full well may destroy you is something shared by many victims of honour-based crime. Take the case of Banaz Mahmod, an Iraqi Kurd who was strangled to death in London in 2006 on the orders of her own father and uncle. Her crime was her desire to leave her abusive arranged marriage. In the lead up to the murder, she had contacted the police for help, and even gave an interview in hospital after smashing a window to escape from her murderous father. The police dismissed her allegations as a warped fantasy.

There appears to be an apathy from the CPS when prosecuting cases where Asian women are victims of honour-based violence.

In 2016, a whistleblower named Det Sgt Pal Singh spoke out about the serious failings of the authorities when it comes to investigating honour-based abuse. ‘There appears to be an apathy from the CPS when prosecuting cases where Asian women are victims of honour-based violence,’ he said. ‘A conviction could lead to unrest in the affected community but if they discontinue a case they know most victims won’t complain due to their vulnerability.’

Killer Britain with Dermot Murnaghan Season Four: Episode Guide

Could the phrase ‘honour killing’ itself, as a categorization, be partly to blame by bathing such crimes in a problematically political light? In 2017, MP Nusrat Ghani called for the phrase to be dropped from official documents, because it leads to a politically correct queasiness when dealing with the crimes, and ‘intimidates the agencies of the states in pursuing and prosecuting these violent crimes’. She suggested that ‘honour’ came with too much cultural baggage, providing a kind of cultural rationalization for ‘what in our society we should call quite simply murder, rape, abuse and enslavement.’

However, others have disagreed, with women’s rights campaigner Diana Nammi saying that honour-based violence IS fundamentally distinct from other kinds of domestic abuse, and that this official categorization is needed so that specific risk factors can be assessed by the authorities.

It’s also important to note honour-based violence isn’t a phenomenon limited to one religion or culture. In 2018, Thomas Ward – a member of the travelling community – was jailed in Manchester for brutally beating his niece after realizing she wanted to leave the community and live with a man of her own choosing.

Inside the pressure cooker: The Luton woman murdered by her own sister

In 2011, a Sikh resident of Telford named Gurmeet Singh Ubhi was convicted of killing his daughter Amrit, for the all-too-familiar reason of 'Westernisation', and the fact she’d dared to fall in love with a non-Sikh. It’s perhaps significant to note that he was already known to have a savage temper, having served years in prison for stabbing and almost killing his wife. Similarly, Shafilea Ahmed’s father had also been known for his sudden and explosive bouts of violence, long before killing his daughter.

Such human failings – the private resentments and rages of certain troubled individuals – are perhaps just as critical to the understanding of honour killings as religious traditions or cultural conservatism. It’s these dense, dark layers of complexity that authorities must probe if they are to end this epidemic of violence in Britain and beyond.

Get true crime stories in your inbox

Sign up to our newsletter to receive email updates on new series, features, and more from your favourite Crime+Investigation shows:

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

‘Murdered for wanting a life’: Banaz Mahmod ‘honour killing' comes to TV

Honour stars Keeley Hawes as a police officer investigating a 2006 murder in the London Iraqi Kurd community. But does it focus too closely on the police, and not the victim?

W ith a track record in writing fact-based drama – including the award-winning sex trafficking drama Doing Money, which aired on the BBC in 2018 – Gwyneth Hughes is used to doing research. But her key source for Honour, an ITV two-parter that goes out next week, raised unusual issues.

“I can’t call her because I don’t have her number, and don’t know what her name is now,” Hughes explains. “So I had to wait for her to call me. I always kept a notebook by the phone in case she suddenly rang.”

The elusive interviewee was Bekhal Mahmod, who has lived in witness protection under a new identity since she helped the police with the prosecution of seven men from the London Iraqi Kurd community, who conspired to rape and murder her 20-year-old sister, Banaz Mahmod, in 2006. Banaz was the victim of a so-called “honour killing” after leaving the husband her family had arranged for her to marry, and loving a young Iranian man of her own choice. Banaz reported the risk to her life to the police on five separate occasions, but no action was taken.

Because of the protection she now requires, Bekhal’s contributions to this piece came through a web of intermediaries to prevent my knowing who or where she is now. The drama has taken six years to reach the screen, during which Bekhal has had long conversations with Hughes. “I explained to her some things about that time she might not have been aware of,” Bekhal says. “This is the truth. It’s amazing how she has done it. I actually didn’t think that she would relay word for word how I explained things to her, but she has.”

Understandably, Bekhal viewed an advance copy of Honour with some apprehension – “I was very, very emotional. It brought it all back. I was very choked up and tearful, and I didn’t sleep much after watching” – but feels happy to have cooperated with the project. “It shows how the police found the Iraqi Kurdish community; it’s such a tight-knit community, so hush-hush and secretive. I hope that by shining a light on this issue, it might prevent what happened to Banaz from happening again.”

A theme of Honour is the emotional impact on all those who worked on the case. The legal consultant was Nazir Afzal, a former chief crown prosecutor, who had overall charge of the prosecution of those who plotted against and killed Banaz. He prosecuted more than 1,000 murders in his career, but recalls this case as uniquely gruelling. “We were working against the victim’s family, whereas normally you’d expect to be working with them,” he says. “They didn’t even want to bury her.” Afzal, the police and a charity bought a gravestone for Banaz and held a memorial service. “It’s the only time I’ve ever done that as a prosecutor.”

The two-part drama is a legal procedural. That may be a common TV genre, but its use is justified here, Afzal believes, because of the unprecedented complexity of the prosecution. Two of the suspects had fled to Iraq and became the first successful extraditions from the country to Britain.

“We were determined,” says Afzal, “that every single person who was involved in that murder was brought to justice, as a statement of intent that no one should ever be allowed to kill a 20-year-old girl for kissing her boyfriend outside a tube station.”

Honour has attracted some controversy for telling the story from the perspective of DCI Caroline Goode, the Metropolitan police’s chief investigating officer, played by Keeley Hawes. For some, the point of view and casting perpetrate a “white saviour” trope.

Afzal is dismissive of this criticism. “The idea that it’s a ‘white saviour’ story is ludicrous. I cannot belittle the work of Caroline Goode and her team. They were fighting internally in the Met police to get this case taken seriously. You’re not normally fighting to persuade the police to investigate a homicide. So you cannot exaggerate the efforts of Caroline and her team. The story is told from the point of view of someone who was a pivotal figure in ensuring justice was done.”

Bekhal says she is “glad that it was produced from the police’s point of view. That side of this story has never been told and that is exactly what happened. It highlights how much the police team had to push in order to bring everyone to justice.”

“The important thing is that Caroline Goode didn’t save anyone,” adds Hughes. “The girl died. She brought the murderers to justice. But she did that in partnership with some amazing Kurds, principally Banaz’s sister. I’ve tried to write it from their dual point of view.”

Some commenters imply that the protagonist here ought to be Banaz. But, Hughes says: “If I’d told it from Banaz’s viewpoint, it can only end in a horrible sordid murder. I didn’t want to do that. Also, ITV is a commercial network – they want people to watch. Bekhal lost her sister, she wants people to watch. The point about Keeley Hawes, apart from being a great actress, is that she is a star who brings an audience. You want as many to watch as possible. Our aim in the drama is to say: this must never happen again, Banaz didn’t die in vain.”

Viewers will want to hope that Banaz’s death represented an extreme outlier of British society, which improvements to police and prosecution methods should now prevent. But is it still happening? Hannana Siddiqui, of Southall Black Sisters, which works with victims of violence against women in south Asian and African communities, says: “Our helpline gets about 7,500 calls a year. That’s a mixture of domestic violence and honour-based violence. And this year, during lockdown, there was a huge increase in helpline calls. There’s also research that suggests 12 honour killings [take place] a year. But it’s hard to say the figures because it is a hidden crime.”

Banaz’s case – and its dramatisation – also lead to conflicting instincts for some white liberals, whose feminist principles encourage support for coerced women, but whose desire to be anti-racist leads to fears of racially profiling and stereotyping Muslim men. Afzal faced this dilemma directly, having, in another part of his career as a crown prosecutor, overturned the original decision not to prosecute a group of largely Pakistani-heritage men who were grooming and sexually abusing young women in Rochdale.

“The law has to operate without fear or favour across the board,” Afzal says. “When you have [something which is] not a new crime, but one being prosecuted for the first time, you can’t afford to think about which communities might be disproportionately implicated. Eighty-four per cent of sex offenders in this country are British white men. Are we saying all white men are like that? Of course not. You have to take the same attitude to forced marriage and honour-based violence in the south Asian, African and Middle Eastern communities.”

“In the Banaz case,” adds Siddiqui, “one of the reasons police were reluctant to get involved was the fear of being accused of cultural insensitivity by the community. And, I think, increasingly, there are now religious sensitivities as well. So there is a fear of interfering in minority cultures or faiths. But you have to be able to intervene. That is mature multiculturalism.”

Hughes admits to concern about the issue. “With this material, you obviously worry about contributing to further social divisions in our country. But you can’t have a situation in which young women are dying and their voices are silenced because of some white liberal fear. For me, feminism outweighed that fear.”

She also points out that there are “male heroes” in the film, especially Banaz’s boyfriend, Rahmat (who, in another of the story’s horrors, later took his own life), and a Kurdish interpreter, Nawzad Gelly, who translated crucial communications.

“I was very concerned not to paint all Kurdish men as murderous bastards because clearly they’re not,” Hughes says. “The police told me about this marvellous Kurdish interpreter, but he’d disappeared from Home Office lists. It took me six months to track him down. He’d gone home to Kurdistan. So we spoke and everything he said to me is in the film. He explained to me that – apart from the misogyny that is obviously a big part of honour killings – it also has to be understood as economics: if nobody marries your daughters because of their so-called ‘shame’ then you’re stuffed within the terms of the community. Neither he nor I are endorsing that system, but it helped me to write about it in terms other than: you are evil.”

From her brave new life, Bekhal hopes Honour will reduce the risk of similar violence occurring. “I sometimes see a woman walking with her husband and, the way they are, I know something isn’t right. The women are so sheltered and dismissed by the male community. They aren’t allowed to mix the way a normal human being should be able to mix, and have a life. For wanting a life, you end up getting murdered. That’s not right, there has to be an end to that. The only way to end that is to make people more aware of it and to watch out for signs.”

She also hopes the drama will be a memorial to who her sister was. “Banaz was lovely. She was honestly the calmest person in any situation. It didn’t matter what it was. She never had any bad feelings towards anybody, even if you’d wronged her. She was very forgiving and very affectionate to people. She was more forgiving than people deserved, she was calm and collected. She was a lovely person. I’d like to think of her as a living person with her kids running around her, but obviously that’s not possible. So I’d like her to be remembered for the good things.”

Honour is on ITV at 9pm, 28 and 29 September

Most viewed

9 High-Profile Honor Killings We Should Remember

The horrendous murder of Pakistani media star Qandeel Baloch by her brother in an apparent "honor killing" this week has garnered world attention for numerous reasons: its brutality, its senselessness, and the horrendous context of sexism and ruthlessly-enforced "honor" that can so frequently endanger women in Pakistan and elsewhere. Baloch appears to have been killed for her brash, sensual, outspoken presence on social media, which was considered reprehensible and threatening to her male relatives. But "honor killings" are neither rare nor, unfortunately, considered particularly newsworthy; the Honor-Based Violence Awareness Network estimates that up to 5000 honor killings occur annually, mainly in India and Pakistan , with the potential for many more, as the vast majority go unreported. TRIGGER WARNING: This article contains violence.

Sadly, Qandeel Baloch's case is hardly unique. The pattern of honor killings as they've increasingly gained media attention, often when they happen among transplanted communities in Western countries, is depressingly familiar: young women disobey traditional rules or attempt to control their own sexual destiny, the family rejects them, and then, even if the girls succumb to pressure and come back into the fold, they are killed. Many perpetrators are unapologetic, saying that the death of the "dishonored" person is necessary to maintain the standing and status of the family in general. A disobedient girl can be a very dangerous thing.

Here are nine other instances of famous honor killings that prove that Qandeel Baloch is the latest tragic instance in a bitter and horrendous tradition.

1999: Samia Sarwar, Pakistan

Sarwar's case was unusual in that it actually happened in the office of a lawyer who was attempting to extricate her from her situation. The daughter of a prominent Pakistani family, Sarwar was attempting to divorce her cousin, who was allegedly abusive, and marry an army officer. After her family refused its permission, she fled to a woman's shelter. Her mother gained entrance to the lawyer's office on the assurance that she'd brought the divorce papers, but instead entered the building accompanied by an assassin, who gunned Sarwar down in her chair. The family has not admitted responsibility, but have said they have "forgiven" Sarwar's killer.

2005: Ghazala Khan, Denmark

A full nine members of Khan's extended family were arrested and convicted of helping to plot her murder and the attempted murder of her then-husband, Emal Khan. The family had punished Ghazala after she admitted that she was having an intimate relationship with Emal prior to marriage; she managed to escape the family home, marry him, and attempt to set up a life. Her family reached out with the pretense of reconciliation and invited her to a meeting at a railway station, at which Ghazala was killed and Emal shot twice by Ghazala's brother Akhtar Abbas. Her father, brother, aunts, and uncles and three family friends were all found guilty and jailed.

2005: Samaira Nazir, Great Britain

British Pakistani woman Samaira Nazir came into conflict with her family over her decision to marry her Afghan boyfriend, whom they believed was of the "wrong caste," instead of the suitors they had selected for her. The results were, as a lawyer described in the ensuing court case, "barbaric" : Nazir was held down in her family home, surrounded by her family (including two small children), and stabbed 18 times by her brother and cousin, including three wounds to her neck. The two murderers were found guilty and sent to prison, but Nazir's father managed to flee the country to Pakistan, where he was alleged to have died.

2007: Sadia Sheikh, Belgium

Sadia Sheikh's honor killing by her brother in 2007 made headlines across Belgium twice: once when it occurred, and again when the entire family were sentenced for it. Sheikh, a Belgian Pakistani, had refused a family-arranged marriage and moved in with a Belgian man , and her brother had shot her when she attempted to mend her relationship with her family. The perpetrator himself was given 15 years when found guilty in 2011, but Sheikh's mother and father, who were determined by the Belgian court to have ordered him to do it, got 20 and 25 years , and her sister received five.

2007: Manoj and Babli Banwala, India

The death of two newlyweds in India created a landmark legal case: Manoj and Babli Banwala, who had run away to be married against the rules of their religious caste, were kidnapped and murdered by members of the bride's family. After first attempting to interfere by alleging that Manoj had kidnapped his wife Babli, her family interrupted their flight by hauling them off a bus, forcing Babli to consume pesticide, and hanging Manoj, whose body was then mutilated. A film has since been made relating to the tragedy , and in a first for India, all five family perpetrators were ordered executed in 2001, and the head of the religious caste council, who ordered the killing, was given life imprisonment.

2008: Pela Atroshi, Iraqi Kurdistan

As with various other cases on this list, this honor killing came to worldwide attention because of its connection to a Western country: in this case, Australia and Sweden . The family of Pela Atroshi had emigrated to Sweden when she was a child, and Pela herself had repeated conflicts that led to her moving out. In 2008, however, she reconciled with them and accepted the offer of an arranged marriage, traveling with her family to Kurdistan to go through with it. Secretly, however, a collection of Atroshi relatives spread across the world, from Sweden to Australia, had orchestrated her trip to Kurdistan to kill her. Her sister Breen testified against the family and is now living in hiding, but only a few members of the family have been prosecuted for the crime, and her father and uncle were given probation in Iraq. Breen explained on television, “My uncles wanted to restore the family honor, but I in return had to restore the honor of Pela."

2008: Ahmet Yildiz, Turkey

The 2008 murder of 26-year-old Ahmet Yildiz was international news for the unusual, and tragic reason: that it may have been one of the first publicly recorded honor killings of a gay man . Having lived openly as a gay man and attended LGBT conferences in the U.S., Yildiz was shot several times while leaving his apartment in Turkey, and the New York Times reported at the time that his body was left unclaimed by his family. Yildiz's family reportedly wanted him to visit a doctor to be "cured" and then get married , and when he refused, they allegedly ordered his assassination. Two of his uncles have received sentences of life in prison for the murder.

2014: Farzana Paveen, Pakistan

Look away now if you can't handle gruesomeness: Farzana was stoned to death in public by her own family outside a courthouse in Lahore as she attempted to testify in a court case. Her family had laid kidnapping charges against her new husband, Mohammad Iqbal, and Farzana, who was pregnant, had turned up to defend him; but her family, who disapproved of the marriage, killed her in full public view with bricks from a local construction site. "I killed my daughter as she had insulted all of our family by marrying a man without our consent, and I have no regret over it," her father was reported to have said.

2014: Attempted Honor Killing Of Saba Qaiser, Pakistan

Saba Qaiser's shooting got our attention for two reasons. One, it was made into a film by Pakistani filmmaker Sharmeen Chinoy, A Girl In The River, which was nominated for a 2014 Academy Award ; and two, Saba survived. Despite being shot in the face by her father and uncle and left for dead in the river, she escaped with a severe head wound and recovered in a Pakistani hospital, where she and Chinoy first met. Her father said from jail, “She took away our honor. If you put one drop of piss in a gallon of milk, the whole thing gets destroyed. That’s what she has done. … So I said, ‘No, I will kill you myself.’”

Chinoy has been one of the most vocally angry responders to Qandeel Baloch's death, telling al-Jazeera that "it's upon the lawmakers to punish these people. We need to start making examples of people. It appears it is very easy to kill a woman in this country — and you can walk off scot-free."

'Honour' Killing and Violence

Theory, Policy and Practice

- © 2014

- Aisha K. Gill 0 ,

- Carolyn Strange 1 ,

- Karl Roberts 2

University of Roehampton, UK

You can also search for this editor in PubMed Google Scholar

Australian National University, Australia

University of western sydney, australia.

13k Accesses

46 Citations

17 Altmetric

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this book

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Other ways to access

Licence this eBook for your library

Institutional subscriptions

About this book

Similar content being viewed by others.

‘Honour’ Crimes

- criminology

Table of contents (11 chapters)

Front matter, introduction: ‘honour’ and ‘honour’-based violence: challenging common assumptions.

Aisha K. Gill

Conceptual Frameworks

Domestic violence or cultural tradition approaches to ‘honour killing’ as species and subspecies in english legal practice, adjusting the lens of honour-based violence: perspectives from euro-american history.

Carolyn Strange

Towards a Psychologically Oriented Motivational Model of Honour-Based Violence

Karl Roberts

Honour as Familial Value

- Johanna Bond

(Dis)honour, Death and Duress in the Courtroom

- Jocelynne A. Scutt

Operationalising/Practices of Honour and Violence

Ordinary v. other violence conceptualising honour-based violence in scandinavian public policies.

- Anja Bredal

‘If there were no khaps […] everything will go haywire […] young boys and girls will start marrying into the same gotra’ : Understanding Khap -Directed ‘Honour Killings’ in Northern India

- Suruchi Thapar-Björkert

‘All they think about is honour’: The Murder of Shafilea Ahmed

Same problem, different solutions: the case of ‘honour killing’ in germany and britain.

- Selen A. Ercan

‘No Place in Canada’: Triumphant Discourses, Murdered Women and the ‘Honour Crime’

- Dana M. Olwan

Back Matter

“The result is an interdisciplinary, comprehensive and unique collection which will provide practitioners, women’s groups, development workers, policy-makers, academics, students and researchers with a range of ideas and analyses on which to draw. … this book is an extremely useful addition to the academic and policy literature and to engendering social change for women across the world in terms of the horror of ‘honour’ violence and killings.” (Gill Hague, Gender & Development, Vol. 23 (3), November, 2015)

'Honour' Killing and Violence is an important resource for academics, practitioners and students working in the areas of gender-based violence internationally and within Britain. This well-written volume provides coverage of a number of important issues and contexts, including law and policy; and community and state responses in Britain, Europe, India and North America. It also benefits from its interdisciplinarity: the contributors use skills from a range of academic disciplines, including history, economics, law, criminology and psychology, to look at this issue, and together they provide a coherent and timely dialogue that will provide fresh and fascinating insight into the topical issue of 'honour' killing and violence.' Dr Geetanjali Gangoli, Centre for Gender and Violence Research, University of Bristol, UK

'The chapters in 'Honour' Killing and Violence bring an invaluable, interdisciplinary perspective to a topic that incites debates characterised more by heat than light. The contributors to this volume do not shy away from these controversies, which is what makes it so timely. At the same time, they do not allow those controversies to limit their analyses to well-trodden ground and blind alleys, which is why the volume is so illuminating. The chapters rely on original empirical evidence and argumentation informed by anthropology, criminology, legal reasoning, history, political science and psychology to urge a multilevel, multicausal approach to understanding honour violence and responses to it. No matter how much you think you know about 'honour'-based violence, you will learn something new and question some of your assumptions about it by reading this book.' Professor Rosemary Gartner, Centre for Criminology and Socio-Legal Studies, University of Toronto, Canada

'A worldwide investigation into a worldwide problem Gill, Strange and Roberts' collection is an excellent place to learn about current international efforts in the area of 'honour' killings and violence.' Professor Nicole Westmarland, Co-Director, Durham Centre for Research into Violence and Abuse, University of Durham, UK

'The contributions in this book skilfully analyse the intersectionality between gender, discrimination, violence and cultural notions of honour, and their interrelatedness in the killings of women. Gender-related killings are not isolated incidents that arise suddenly and unexpectedly, but are often the ultimate act of violence in a continuum of gender-based discrimination and violence.' Ms Rashida Manjoo, United Nations Special Rapporteur on Violence against Women, South Africa

Editors and Affiliations

About the editors, bibliographic information.

Book Title : 'Honour' Killing and Violence

Book Subtitle : Theory, Policy and Practice

Editors : Aisha K. Gill, Carolyn Strange, Karl Roberts

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137289568

Publisher : Palgrave Macmillan London

eBook Packages : Palgrave Social Sciences Collection , Social Sciences (R0)

Copyright Information : Palgrave Macmillan, a division of Macmillan Publishers Limited 2014

Hardcover ISBN : 978-1-137-28954-4 Published: 07 May 2014

Softcover ISBN : 978-1-137-28955-1 Published: 07 May 2014

eBook ISBN : 978-1-137-28956-8 Published: 07 May 2014

Edition Number : 1

Number of Pages : XX, 244

Topics : Personality and Social Psychology , Gender Studies , Criminology and Criminal Justice, general , Crime and Society , Human Rights , Ethics

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Honour-based crimes

What is it?

Honour-based crimes are violent crimes or other forms of abuse that are carried out in order to protect the so-called ‘honour’ of a family or community.

The code of ‘honour’ to which it refers is set by the male relatives of a family, and women who break the rules of the code are punished for bringing shame upon the family.

Women can be subjected to honour-based punishments for trying to:

Separate or divorce

Start a new relationship

Talk to or interact freely with men

Become pregnant or give birth outside of marriage

Have relationships or marry outside a particular religion

Have sex before marriage

Marry a person of their own choice

Attend college or university

Forms of honour-based crimes can include:

- Forced marriage

- Domestic abuse

Sexual violence and harassment

Threats to kill

Social ostracism or rejection and emotional pressure

Not being allowed access to your children

Pressure to go or move abroad

House arrest and restrictions of freedom

No access to telephone, internet, or passport

Isolation from friends and family

Is it a crime?

Yes, even if it doesn’t involve violence. It is a particularly under-reported crime, as often victims are too scared, coerced, idolated, or tied by family loyalties to speak out. While there is no specific offence of “honour based crime”, it is an umbrella term to encompass various offences covered by existing legislation.

Who is most at risk?

Women and girls from some black and minoritised ethnic (BAME) communities, particularly in South Asia and the Middle East.

What can you do if you are worried about someone you know?

If a person is in immediate danger, call 999.

If you are concerned that someone you know is a victim of honour-based violence, you could contact the Freephone Karma Nirvana Helpline on 0800 5999 247 , which is open from 9am to 5pm weekdays and supports victims of forced marriage and honour-based abuse. You can also contact the Freephone 24-hour National Domestic Violence Helpline on 0808 2000 247 run by Refuge .

You can also report your concerns to the police on 101 . If you are in London, the Metropolitan Police are very keen that people report any concerns about honour-based crimes, and will record and investigate all instances, even if there is only a small amount of information available or when a victim has not reported it themselves. Every London borough has a team of specially trained officers, in local specialist Community Safety Units, who are responsible for investigating hate crimes and honour-based violence.

However, if you are outside London, you can still contact your local police on 101 .

The police advise that you should talk to the suspected victim and encourage them to talk to someone else about it. This might be very scary for them, so even if they don’t talk about it, your support might help them in the future. You can encourage them to:

- Talk to their teacher or another responsible adult

- Contact ChildLine to talk to a professional who can offer help and advice

- Talk in confidence to one of the organisations and charities working to support survivors of honour-based crimes, such as Karma Nirvana , Southall Black Sisters, True Honour , or The Halo Project – or call the HM Government Forced Marriage Unit on 020 7708 0151.

To help you raise awareness among your community about honour-based crime and how to spot the signs, we’ve compiled a range of free campaign materials that you can use to educate and inform people in your neighbourhood.

Resources include:

Leaflets and posters that you can print off and hand out at events or leave in public places such as GP surgeries or schools, for people to pick up.

However, leaflets should not be put through letterboxes , just in case a perpetrator sees it and suspects the victim is seeking help or reporting their behaviour.

Online materials such as campaign websites, videos, GIFs and graphics that you can email to your local Neighbourhood Watch group members or share on social media sites such as your Neighbourhood Watch Facebook group or Twitter feed.

Printable resources

Neighbourhood Watch has produced a leaflet urging members to be aware of the signs of forced marriage, honour-based violence or female genital mutilation in their communities. You can find it in the Downloads section on this page .

Online resources

- The BBC has produced an Ethics guide to ‘honour’ crimes.

- Crimestoppers has produced a film called Hidden harms: Honour based abuse

- Southall Black Sisters has produced a film called My second name is Honour

- The University of Derby has produced a film called Rubie’s story – Forced marriages and honour based abuse

- Dr Moira Dustin: ‘Honour’ and violence against women – what’s in a name?

- Afrah Qassim, Savera UK – Breaking the silence within communities and service-providers

We are making this a better place to live. Together.

Belonging to Neighbourhood Watch has a host of benefits Find out more

- Our journey

- Neighbourhood Watch today

- Our research

- Ways to work with us

- Our statutory and voluntary partners

- ERA and Neighbourhood Watch

- SimpliSafe and Neighbourhood Watch

- Diversity, Equality and Inclusion Statement

- Ethics and standards

- Privacy and cookie policy

- Media & press

- Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

- What is an Association?

- Find my Association

- Find my local scheme

- Join our lottery

- Shop with us

- Crowdfunding

- Easyfundraising

- ASB, mental health and support

- Could it be a hate crime?

- Fly-tipping

- Need more support?

- ASB case study 1

- ASB case study 2

- ASB case study 3

- ASB case study 4

- ASB case study 5

- ASB case study 6

- Bicycle theft

- Burglary reporting and support

- Burglary prevention toolkit

- Child sexual exploitation

- Spotting the signs

- Talking about child sexual exploitation

- Child sexual exploitation campaign toolkit

- Coercing and controlling children and young people

- Reporting your concerns

- Financial abuse

- How to help

- Domestic abuse campaign toolkit

- Elder abuse

- Impact of hate crime

- Reporting hate crime

- Support for victims

- Disability hate crime

- Homophobic and transphobic hate crime

- Religious and racist hate crime

- Gender-based hate crime

- Heritage crime

- Modern slavery types and human trafficking

- Coercing and controlling victims

- Deer Poaching

- Hare Coursing

- Theft of livestock and machinery

- Using the countryside with respect

- Livestock worrying

- Common scams

- Doorstep scams

- Online scams

- Pension and investment fraud

- Phone scams

- Romance fraud

- Reporting scams

- Cyberhood Watch toolkit

- Scams campaigning toolkit

- Serious violence

- Talking to young people

- Serious violence campaign toolkit

- Password protection

- Understanding street harassment

- What can be done about it?

- Report and support

- Online extremism

- Terrorism campaign toolkit

- Cybercrime advice with Cyberhood Watch

- Join Cyberhood Watch!

- Have you been affected by cybercrime?

- Being an active bystander

- Ways to intervene

- Reporting a crime

- Loneliness and vulnerability

- Tackling loneliness

- Services and support

- Loneliness & vulnerability campaign toolkit

- Who's at risk

- Youth isolation toolkit

- Youth Council

- Student magazine The Lookout

- How crime affects students

- 7 steps to a safe student night out

- A student's guide to safe solo travel

- Focusing on your wellbeing at university

- How to help someone who's had their drink spiked

- If they can't hear you, make them!

- Night out SOS: a student's first aid kit

- Protecting your nudes: essential cybersecurity tips

- Let's talk drugs

- Community Safety Charter

- Recruitment - BETTER PLACE TO LIVE

- Become a Coordinator

- Volunteer Recognition Awards

- Become a Multi Scheme Administrator (MSA)

- Become a Hate Crime Community Ambassador

- Support your Association

- Become a Community Champion

- Become A Partner

- Knowledge Hub

- Starting your group step by step

- Branding and logo

- Safeguarding guidance for NW Coordinators

- Managing members' data

- Branding & logo

- Stickers & signage

- Public liability insurance

- Fundraising

- Our Community Grants Fund

- Using social media

- Running events

- Measuring your impact

- Set up and run an Association

- Self assess your Association

- Financial support, money-saving tips, help with energy and food costs

- Steps to help avoid becoming a victim of crime

- Support to help reduce loneliness and isolation

- Raise crime prevention awareness

- Build more inclusive networks

- Supporting your community and others

- Develop community cohesion

- Community environment and wellbeing

- Inspiring communities

- Nurturing communications

- Sustaining schemes

- Devon and Cornwall take action about Livestock Worrying

- Involving young people

- Recognising members

- Engaging technology

- Diversifying membership

- Find out more

- Our News eNewsletters

- Campaign news

- Crime prevention news

- North Warwickshire commended for supporting crime prevention

- Submit a local news story

- Build more local inclusive networks

- Improve community environment and wellbeing

- Volunteer Recognition Awards 2023 winners

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Abdullah Mohammed, 41, and his wife, Aysha, 39, died after they were overcome by smoke and fumes at their home in Blackburn, Lancashire in a bungled "honour" killing. Four men firebombed their ...

Honor crimes derive from a conceptualization of honor that ... 109) provide members of the community with a meaning for and justification of the woman's murder. In the case of honor killing, those who commit the murder believe that they have done the right thing. ... The study of honor killing requires a deeper understanding of the value ...

The documentaries chosen as case studies provide the perspectives of both the victims and the victimizers regarding the concepts of honor, dishonor, and honor killings. ... such killings has also been discussed through these films. Among themselves, the documentaries selected for the study bring insights into honor crime cases covering a period ...

This case study demonstrated how a crime shaped by the notion of honour starts with abuse and ends with it. Surjit's ordeal started with forced and early marriage; she survived domestic and emotional abuse, and she was killed for the sake of the so-called family honour. ... Box 5 Case Study 2: Flawed Trials Concerning Honour Killing. Fouzia ...

Abstract. On 3 August 2012, Shafilea Ahmed's parents were convicted of her murder, nine years after the brutal 'honour' killing. The case offers important insights into how 'honour'-based violence might be tackled without constructing non-Western cultures as inherently uncivilised. Critiquing the framing devices that structure British ...

Honour killings. Cellini roams between the great Italian courts, making art and causing trouble. On his return to Florence, Cellini experiences the horrors of the plague. Told by a classmate, the ...

'Honour' crime: a working definition of a contested concept Crimes such as forced marriage, kidnap, rape, murder, false imprison- ... 'Honour' Crimes 83 recent example being the case of Shafilea Ahmed, in which both of her parents were charged with her murder and sentenced to life imprison-ment (see discussion below). Moreover, albeit ...

The text begins with the problem of language and definition crippling understanding and responses to honour crimes in various countries. George Orwell famously wrote in 1984 that an idea (and in turn a feeling or a belief) cannot exist without the word for it. The editors and authors of 'Honour' Killing and Violence: Theory, Policy and Practice start from a different place: that, in a ...

There were other reasons why a woman in Europe might find herself murdered by her relatives. In 1546 in Italy, Isabella Morra, the 25-year-old daughter of the baron of Favale, was murdered by her ...

The case of Shafilea Ahmed is illustrative of the traumatic nuances of so-called 'honour killings' when parents or guardians expect a younger relative to abide by a rigid, uncompromising code of behaviour or face brutal punishment. The victims are women in the overwhelming number of cases. As veteran feminist campaigner Julie Bindel puts it ...

Honour killing is the murder of a person accused of "bringing shame" upon their family. Victims have been killed for refusing to enter a marriage, committing adultery or being in a relationship ...

A theme of Honour is the emotional impact on all those who worked on the case. The legal consultant was Nazir Afzal, a former chief crown prosecutor, who had overall charge of the prosecution of ...

The text begins with the problem of language and definition crippling understanding and responses to honour crimes in various countries. George Orwell famously wrote in 1984 that an idea (and in turn a feeling or a belief) cannot exist without the word for it. The editors and authors of 'Honour' Killing and Violence: Theory, Policy and Practice start from a different place: that, in a ...

The 2008 murder of 26-year-old Ahmet Yildiz was international news for the unusual, and tragic reason: that it may have been one of the first publicly recorded honor killings of a gay man. Having ...

The purpose of the study was to determine the causes of death as reported in court files of the female victims of honour crimes, the Jordanian penal codes regarding crimes of honour, the evidence ...

'Honour' Killing and Violence is an important resource for academics, practitioners and students working in the areas of gender-based violence internationally and within Britain. This well-written volume provides coverage of a number of important issues and contexts, including law and policy; and community and state responses in Britain, Europe ...

More than 11,000 cases of so-called honour crime were recorded by UK police forces from 2010-14, new figures show. ... Millions more middle-aged are obese, study suggests

honor killing, most often, the murder of a woman or girl by male family members. The killers justify their actions by claiming that the victim has brought dishonor upon the family name or prestige.. In patriarchal societies, the activities of girls and women are closely monitored. The maintenance of a woman's virginity and "sexual purity" are considered to be the responsibility of male ...

Because of data limitations, we analyze only honour killings (versus the spectrum of honour crimes), defined as a premeditated crime with the intention to take the life of a woman, and/or those associated with her, bringing shame to the family or community. ... the details in the case study reports indicate that women—and not just men—in ...

Honour-based crimes are violent crimes or other forms of abuse that are carried out in order to protect the so-called 'honour' of a family or community. The code of 'honour' to which it refers is set by the male relatives of a family, and women who break the rules of the code are punished for bringing shame upon the family.

for crimes pertaining to honor at 5,000 (UNFPA, 2000). However, individual studies maintain that the actual figure is closer to 20,000 per year worldwide (Kiener, 2011). In this study, we hypothesize that honor killings are per-petrated due to the (personal/social) belief that sexual misconduct of women which brings shame and dishonor to