Random Assignment in Psychology: Definition & Examples

Julia Simkus

Editor at Simply Psychology

BA (Hons) Psychology, Princeton University

Julia Simkus is a graduate of Princeton University with a Bachelor of Arts in Psychology. She is currently studying for a Master's Degree in Counseling for Mental Health and Wellness in September 2023. Julia's research has been published in peer reviewed journals.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Saul Mcleod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul Mcleod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

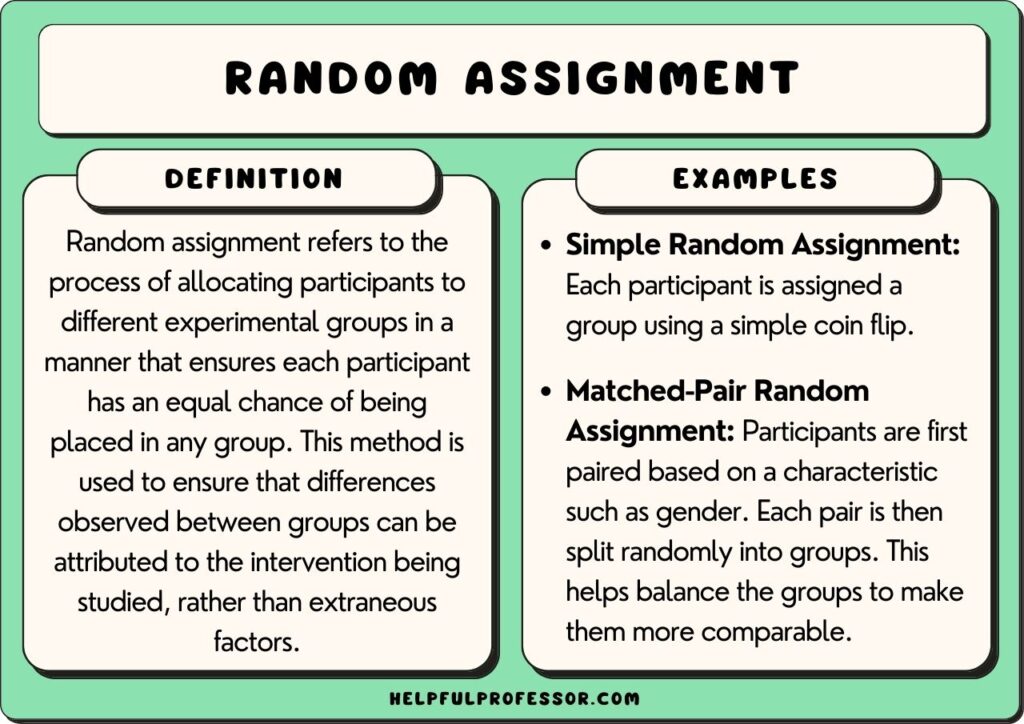

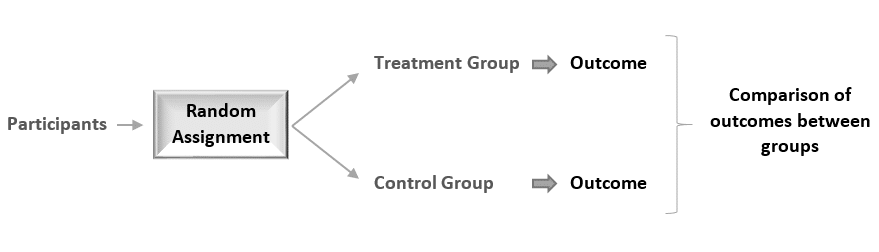

In psychology, random assignment refers to the practice of allocating participants to different experimental groups in a study in a completely unbiased way, ensuring each participant has an equal chance of being assigned to any group.

In experimental research, random assignment, or random placement, organizes participants from your sample into different groups using randomization.

Random assignment uses chance procedures to ensure that each participant has an equal opportunity of being assigned to either a control or experimental group.

The control group does not receive the treatment in question, whereas the experimental group does receive the treatment.

When using random assignment, neither the researcher nor the participant can choose the group to which the participant is assigned. This ensures that any differences between and within the groups are not systematic at the onset of the study.

In a study to test the success of a weight-loss program, investigators randomly assigned a pool of participants to one of two groups.

Group A participants participated in the weight-loss program for 10 weeks and took a class where they learned about the benefits of healthy eating and exercise.

Group B participants read a 200-page book that explains the benefits of weight loss. The investigator randomly assigned participants to one of the two groups.

The researchers found that those who participated in the program and took the class were more likely to lose weight than those in the other group that received only the book.

Importance

Random assignment ensures that each group in the experiment is identical before applying the independent variable.

In experiments , researchers will manipulate an independent variable to assess its effect on a dependent variable, while controlling for other variables. Random assignment increases the likelihood that the treatment groups are the same at the onset of a study.

Thus, any changes that result from the independent variable can be assumed to be a result of the treatment of interest. This is particularly important for eliminating sources of bias and strengthening the internal validity of an experiment.

Random assignment is the best method for inferring a causal relationship between a treatment and an outcome.

Random Selection vs. Random Assignment

Random selection (also called probability sampling or random sampling) is a way of randomly selecting members of a population to be included in your study.

On the other hand, random assignment is a way of sorting the sample participants into control and treatment groups.

Random selection ensures that everyone in the population has an equal chance of being selected for the study. Once the pool of participants has been chosen, experimenters use random assignment to assign participants into groups.

Random assignment is only used in between-subjects experimental designs, while random selection can be used in a variety of study designs.

Random Assignment vs Random Sampling

Random sampling refers to selecting participants from a population so that each individual has an equal chance of being chosen. This method enhances the representativeness of the sample.

Random assignment, on the other hand, is used in experimental designs once participants are selected. It involves allocating these participants to different experimental groups or conditions randomly.

This helps ensure that any differences in results across groups are due to manipulating the independent variable, not preexisting differences among participants.

When to Use Random Assignment

Random assignment is used in experiments with a between-groups or independent measures design.

In these research designs, researchers will manipulate an independent variable to assess its effect on a dependent variable, while controlling for other variables.

There is usually a control group and one or more experimental groups. Random assignment helps ensure that the groups are comparable at the onset of the study.

How to Use Random Assignment

There are a variety of ways to assign participants into study groups randomly. Here are a handful of popular methods:

- Random Number Generator : Give each member of the sample a unique number; use a computer program to randomly generate a number from the list for each group.

- Lottery : Give each member of the sample a unique number. Place all numbers in a hat or bucket and draw numbers at random for each group.

- Flipping a Coin : Flip a coin for each participant to decide if they will be in the control group or experimental group (this method can only be used when you have just two groups)

- Roll a Die : For each number on the list, roll a dice to decide which of the groups they will be in. For example, assume that rolling 1, 2, or 3 places them in a control group and rolling 3, 4, 5 lands them in an experimental group.

When is Random Assignment not used?

- When it is not ethically permissible: Randomization is only ethical if the researcher has no evidence that one treatment is superior to the other or that one treatment might have harmful side effects.

- When answering non-causal questions : If the researcher is just interested in predicting the probability of an event, the causal relationship between the variables is not important and observational designs would be more suitable than random assignment.

- When studying the effect of variables that cannot be manipulated: Some risk factors cannot be manipulated and so it would not make any sense to study them in a randomized trial. For example, we cannot randomly assign participants into categories based on age, gender, or genetic factors.

Drawbacks of Random Assignment

While randomization assures an unbiased assignment of participants to groups, it does not guarantee the equality of these groups. There could still be extraneous variables that differ between groups or group differences that arise from chance. Additionally, there is still an element of luck with random assignments.

Thus, researchers can not produce perfectly equal groups for each specific study. Differences between the treatment group and control group might still exist, and the results of a randomized trial may sometimes be wrong, but this is absolutely okay.

Scientific evidence is a long and continuous process, and the groups will tend to be equal in the long run when data is aggregated in a meta-analysis.

Additionally, external validity (i.e., the extent to which the researcher can use the results of the study to generalize to the larger population) is compromised with random assignment.

Random assignment is challenging to implement outside of controlled laboratory conditions and might not represent what would happen in the real world at the population level.

Random assignment can also be more costly than simple observational studies, where an investigator is just observing events without intervening with the population.

Randomization also can be time-consuming and challenging, especially when participants refuse to receive the assigned treatment or do not adhere to recommendations.

What is the difference between random sampling and random assignment?

Random sampling refers to randomly selecting a sample of participants from a population. Random assignment refers to randomly assigning participants to treatment groups from the selected sample.

Does random assignment increase internal validity?

Yes, random assignment ensures that there are no systematic differences between the participants in each group, enhancing the study’s internal validity .

Does random assignment reduce sampling error?

Yes, with random assignment, participants have an equal chance of being assigned to either a control group or an experimental group, resulting in a sample that is, in theory, representative of the population.

Random assignment does not completely eliminate sampling error because a sample only approximates the population from which it is drawn. However, random sampling is a way to minimize sampling errors.

When is random assignment not possible?

Random assignment is not possible when the experimenters cannot control the treatment or independent variable.

For example, if you want to compare how men and women perform on a test, you cannot randomly assign subjects to these groups.

Participants are not randomly assigned to different groups in this study, but instead assigned based on their characteristics.

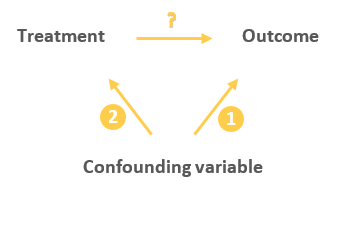

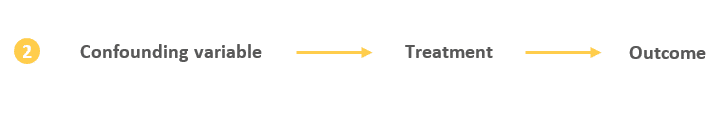

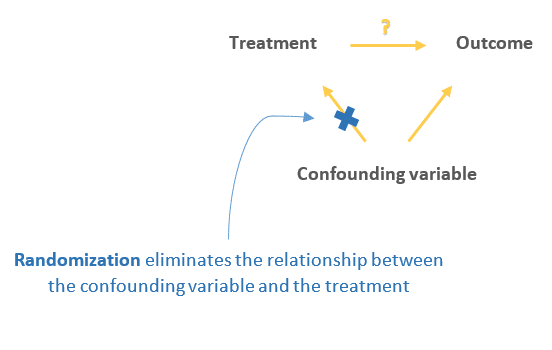

Does random assignment eliminate confounding variables?

Yes, random assignment eliminates the influence of any confounding variables on the treatment because it distributes them at random among the study groups. Randomization invalidates any relationship between a confounding variable and the treatment.

Why is random assignment of participants to treatment conditions in an experiment used?

Random assignment is used to ensure that all groups are comparable at the start of a study. This allows researchers to conclude that the outcomes of the study can be attributed to the intervention at hand and to rule out alternative explanations for study results.

Further Reading

- Bogomolnaia, A., & Moulin, H. (2001). A new solution to the random assignment problem . Journal of Economic theory , 100 (2), 295-328.

- Krause, M. S., & Howard, K. I. (2003). What random assignment does and does not do . Journal of Clinical Psychology , 59 (7), 751-766.

Related Articles

Research Methodology

Qualitative Data Coding

What Is a Focus Group?

Cross-Cultural Research Methodology In Psychology

What Is Internal Validity In Research?

Research Methodology , Statistics

What Is Face Validity In Research? Importance & How To Measure

Criterion Validity: Definition & Examples

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

The Definition of Random Assignment According to Psychology

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Emily is a board-certified science editor who has worked with top digital publishing brands like Voices for Biodiversity, Study.com, GoodTherapy, Vox, and Verywell.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Emily-Swaim-1000-0f3197de18f74329aeffb690a177160c.jpg)

Materio / Getty Images

Random assignment refers to the use of chance procedures in psychology experiments to ensure that each participant has the same opportunity to be assigned to any given group in a study to eliminate any potential bias in the experiment at the outset. Participants are randomly assigned to different groups, such as the treatment group versus the control group. In clinical research, randomized clinical trials are known as the gold standard for meaningful results.

Simple random assignment techniques might involve tactics such as flipping a coin, drawing names out of a hat, rolling dice, or assigning random numbers to a list of participants. It is important to note that random assignment differs from random selection .

While random selection refers to how participants are randomly chosen from a target population as representatives of that population, random assignment refers to how those chosen participants are then assigned to experimental groups.

Random Assignment In Research

To determine if changes in one variable will cause changes in another variable, psychologists must perform an experiment. Random assignment is a critical part of the experimental design that helps ensure the reliability of the study outcomes.

Researchers often begin by forming a testable hypothesis predicting that one variable of interest will have some predictable impact on another variable.

The variable that the experimenters will manipulate in the experiment is known as the independent variable , while the variable that they will then measure for different outcomes is known as the dependent variable. While there are different ways to look at relationships between variables, an experiment is the best way to get a clear idea if there is a cause-and-effect relationship between two or more variables.

Once researchers have formulated a hypothesis, conducted background research, and chosen an experimental design, it is time to find participants for their experiment. How exactly do researchers decide who will be part of an experiment? As mentioned previously, this is often accomplished through something known as random selection.

Random Selection

In order to generalize the results of an experiment to a larger group, it is important to choose a sample that is representative of the qualities found in that population. For example, if the total population is 60% female and 40% male, then the sample should reflect those same percentages.

Choosing a representative sample is often accomplished by randomly picking people from the population to be participants in a study. Random selection means that everyone in the group stands an equal chance of being chosen to minimize any bias. Once a pool of participants has been selected, it is time to assign them to groups.

By randomly assigning the participants into groups, the experimenters can be fairly sure that each group will have the same characteristics before the independent variable is applied.

Participants might be randomly assigned to the control group , which does not receive the treatment in question. The control group may receive a placebo or receive the standard treatment. Participants may also be randomly assigned to the experimental group , which receives the treatment of interest. In larger studies, there can be multiple treatment groups for comparison.

There are simple methods of random assignment, like rolling the die. However, there are more complex techniques that involve random number generators to remove any human error.

There can also be random assignment to groups with pre-established rules or parameters. For example, if you want to have an equal number of men and women in each of your study groups, you might separate your sample into two groups (by sex) before randomly assigning each of those groups into the treatment group and control group.

Random assignment is essential because it increases the likelihood that the groups are the same at the outset. With all characteristics being equal between groups, other than the application of the independent variable, any differences found between group outcomes can be more confidently attributed to the effect of the intervention.

Example of Random Assignment

Imagine that a researcher is interested in learning whether or not drinking caffeinated beverages prior to an exam will improve test performance. After randomly selecting a pool of participants, each person is randomly assigned to either the control group or the experimental group.

The participants in the control group consume a placebo drink prior to the exam that does not contain any caffeine. Those in the experimental group, on the other hand, consume a caffeinated beverage before taking the test.

Participants in both groups then take the test, and the researcher compares the results to determine if the caffeinated beverage had any impact on test performance.

A Word From Verywell

Random assignment plays an important role in the psychology research process. Not only does this process help eliminate possible sources of bias, but it also makes it easier to generalize the results of a tested sample of participants to a larger population.

Random assignment helps ensure that members of each group in the experiment are the same, which means that the groups are also likely more representative of what is present in the larger population of interest. Through the use of this technique, psychology researchers are able to study complex phenomena and contribute to our understanding of the human mind and behavior.

Lin Y, Zhu M, Su Z. The pursuit of balance: An overview of covariate-adaptive randomization techniques in clinical trials . Contemp Clin Trials. 2015;45(Pt A):21-25. doi:10.1016/j.cct.2015.07.011

Sullivan L. Random assignment versus random selection . In: The SAGE Glossary of the Social and Behavioral Sciences. SAGE Publications, Inc.; 2009. doi:10.4135/9781412972024.n2108

Alferes VR. Methods of Randomization in Experimental Design . SAGE Publications, Inc.; 2012. doi:10.4135/9781452270012

Nestor PG, Schutt RK. Research Methods in Psychology: Investigating Human Behavior. (2nd Ed.). SAGE Publications, Inc.; 2015.

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

Chapter 6: Experimental Research

6.2 experimental design, learning objectives.

- Explain the difference between between-subjects and within-subjects experiments, list some of the pros and cons of each approach, and decide which approach to use to answer a particular research question.

- Define random assignment, distinguish it from random sampling, explain its purpose in experimental research, and use some simple strategies to implement it.

- Define what a control condition is, explain its purpose in research on treatment effectiveness, and describe some alternative types of control conditions.

- Define several types of carryover effect, give examples of each, and explain how counterbalancing helps to deal with them.

In this section, we look at some different ways to design an experiment. The primary distinction we will make is between approaches in which each participant experiences one level of the independent variable and approaches in which each participant experiences all levels of the independent variable. The former are called between-subjects experiments and the latter are called within-subjects experiments.

Between-Subjects Experiments

In a between-subjects experiment , each participant is tested in only one condition. For example, a researcher with a sample of 100 college students might assign half of them to write about a traumatic event and the other half write about a neutral event. Or a researcher with a sample of 60 people with severe agoraphobia (fear of open spaces) might assign 20 of them to receive each of three different treatments for that disorder. It is essential in a between-subjects experiment that the researcher assign participants to conditions so that the different groups are, on average, highly similar to each other. Those in a trauma condition and a neutral condition, for example, should include a similar proportion of men and women, and they should have similar average intelligence quotients (IQs), similar average levels of motivation, similar average numbers of health problems, and so on. This is a matter of controlling these extraneous participant variables across conditions so that they do not become confounding variables.

Random Assignment

The primary way that researchers accomplish this kind of control of extraneous variables across conditions is called random assignment , which means using a random process to decide which participants are tested in which conditions. Do not confuse random assignment with random sampling. Random sampling is a method for selecting a sample from a population, and it is rarely used in psychological research. Random assignment is a method for assigning participants in a sample to the different conditions, and it is an important element of all experimental research in psychology and other fields too.

In its strictest sense, random assignment should meet two criteria. One is that each participant has an equal chance of being assigned to each condition (e.g., a 50% chance of being assigned to each of two conditions). The second is that each participant is assigned to a condition independently of other participants. Thus one way to assign participants to two conditions would be to flip a coin for each one. If the coin lands heads, the participant is assigned to Condition A, and if it lands tails, the participant is assigned to Condition B. For three conditions, one could use a computer to generate a random integer from 1 to 3 for each participant. If the integer is 1, the participant is assigned to Condition A; if it is 2, the participant is assigned to Condition B; and if it is 3, the participant is assigned to Condition C. In practice, a full sequence of conditions—one for each participant expected to be in the experiment—is usually created ahead of time, and each new participant is assigned to the next condition in the sequence as he or she is tested. When the procedure is computerized, the computer program often handles the random assignment.

One problem with coin flipping and other strict procedures for random assignment is that they are likely to result in unequal sample sizes in the different conditions. Unequal sample sizes are generally not a serious problem, and you should never throw away data you have already collected to achieve equal sample sizes. However, for a fixed number of participants, it is statistically most efficient to divide them into equal-sized groups. It is standard practice, therefore, to use a kind of modified random assignment that keeps the number of participants in each group as similar as possible. One approach is block randomization . In block randomization, all the conditions occur once in the sequence before any of them is repeated. Then they all occur again before any of them is repeated again. Within each of these “blocks,” the conditions occur in a random order. Again, the sequence of conditions is usually generated before any participants are tested, and each new participant is assigned to the next condition in the sequence. Table 6.2 “Block Randomization Sequence for Assigning Nine Participants to Three Conditions” shows such a sequence for assigning nine participants to three conditions. The Research Randomizer website ( http://www.randomizer.org ) will generate block randomization sequences for any number of participants and conditions. Again, when the procedure is computerized, the computer program often handles the block randomization.

Table 6.2 Block Randomization Sequence for Assigning Nine Participants to Three Conditions

Random assignment is not guaranteed to control all extraneous variables across conditions. It is always possible that just by chance, the participants in one condition might turn out to be substantially older, less tired, more motivated, or less depressed on average than the participants in another condition. However, there are some reasons that this is not a major concern. One is that random assignment works better than one might expect, especially for large samples. Another is that the inferential statistics that researchers use to decide whether a difference between groups reflects a difference in the population takes the “fallibility” of random assignment into account. Yet another reason is that even if random assignment does result in a confounding variable and therefore produces misleading results, this is likely to be detected when the experiment is replicated. The upshot is that random assignment to conditions—although not infallible in terms of controlling extraneous variables—is always considered a strength of a research design.

Treatment and Control Conditions

Between-subjects experiments are often used to determine whether a treatment works. In psychological research, a treatment is any intervention meant to change people’s behavior for the better. This includes psychotherapies and medical treatments for psychological disorders but also interventions designed to improve learning, promote conservation, reduce prejudice, and so on. To determine whether a treatment works, participants are randomly assigned to either a treatment condition , in which they receive the treatment, or a control condition , in which they do not receive the treatment. If participants in the treatment condition end up better off than participants in the control condition—for example, they are less depressed, learn faster, conserve more, express less prejudice—then the researcher can conclude that the treatment works. In research on the effectiveness of psychotherapies and medical treatments, this type of experiment is often called a randomized clinical trial .

There are different types of control conditions. In a no-treatment control condition , participants receive no treatment whatsoever. One problem with this approach, however, is the existence of placebo effects. A placebo is a simulated treatment that lacks any active ingredient or element that should make it effective, and a placebo effect is a positive effect of such a treatment. Many folk remedies that seem to work—such as eating chicken soup for a cold or placing soap under the bedsheets to stop nighttime leg cramps—are probably nothing more than placebos. Although placebo effects are not well understood, they are probably driven primarily by people’s expectations that they will improve. Having the expectation to improve can result in reduced stress, anxiety, and depression, which can alter perceptions and even improve immune system functioning (Price, Finniss, & Benedetti, 2008).

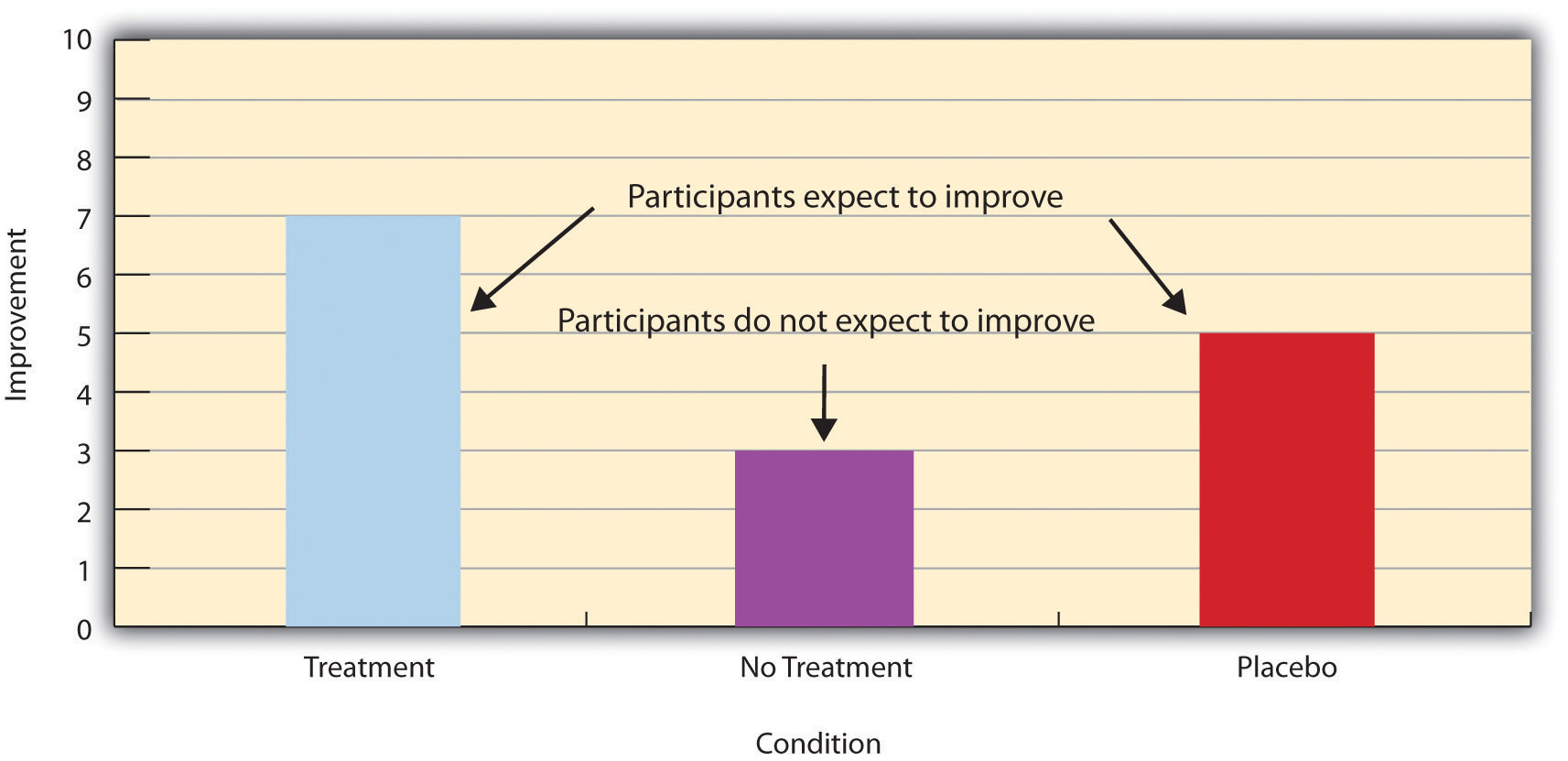

Placebo effects are interesting in their own right (see Note 6.28 “The Powerful Placebo” ), but they also pose a serious problem for researchers who want to determine whether a treatment works. Figure 6.2 “Hypothetical Results From a Study Including Treatment, No-Treatment, and Placebo Conditions” shows some hypothetical results in which participants in a treatment condition improved more on average than participants in a no-treatment control condition. If these conditions (the two leftmost bars in Figure 6.2 “Hypothetical Results From a Study Including Treatment, No-Treatment, and Placebo Conditions” ) were the only conditions in this experiment, however, one could not conclude that the treatment worked. It could be instead that participants in the treatment group improved more because they expected to improve, while those in the no-treatment control condition did not.

Figure 6.2 Hypothetical Results From a Study Including Treatment, No-Treatment, and Placebo Conditions

Fortunately, there are several solutions to this problem. One is to include a placebo control condition , in which participants receive a placebo that looks much like the treatment but lacks the active ingredient or element thought to be responsible for the treatment’s effectiveness. When participants in a treatment condition take a pill, for example, then those in a placebo control condition would take an identical-looking pill that lacks the active ingredient in the treatment (a “sugar pill”). In research on psychotherapy effectiveness, the placebo might involve going to a psychotherapist and talking in an unstructured way about one’s problems. The idea is that if participants in both the treatment and the placebo control groups expect to improve, then any improvement in the treatment group over and above that in the placebo control group must have been caused by the treatment and not by participants’ expectations. This is what is shown by a comparison of the two outer bars in Figure 6.2 “Hypothetical Results From a Study Including Treatment, No-Treatment, and Placebo Conditions” .

Of course, the principle of informed consent requires that participants be told that they will be assigned to either a treatment or a placebo control condition—even though they cannot be told which until the experiment ends. In many cases the participants who had been in the control condition are then offered an opportunity to have the real treatment. An alternative approach is to use a waitlist control condition , in which participants are told that they will receive the treatment but must wait until the participants in the treatment condition have already received it. This allows researchers to compare participants who have received the treatment with participants who are not currently receiving it but who still expect to improve (eventually). A final solution to the problem of placebo effects is to leave out the control condition completely and compare any new treatment with the best available alternative treatment. For example, a new treatment for simple phobia could be compared with standard exposure therapy. Because participants in both conditions receive a treatment, their expectations about improvement should be similar. This approach also makes sense because once there is an effective treatment, the interesting question about a new treatment is not simply “Does it work?” but “Does it work better than what is already available?”

The Powerful Placebo

Many people are not surprised that placebos can have a positive effect on disorders that seem fundamentally psychological, including depression, anxiety, and insomnia. However, placebos can also have a positive effect on disorders that most people think of as fundamentally physiological. These include asthma, ulcers, and warts (Shapiro & Shapiro, 1999). There is even evidence that placebo surgery—also called “sham surgery”—can be as effective as actual surgery.

Medical researcher J. Bruce Moseley and his colleagues conducted a study on the effectiveness of two arthroscopic surgery procedures for osteoarthritis of the knee (Moseley et al., 2002). The control participants in this study were prepped for surgery, received a tranquilizer, and even received three small incisions in their knees. But they did not receive the actual arthroscopic surgical procedure. The surprising result was that all participants improved in terms of both knee pain and function, and the sham surgery group improved just as much as the treatment groups. According to the researchers, “This study provides strong evidence that arthroscopic lavage with or without débridement [the surgical procedures used] is not better than and appears to be equivalent to a placebo procedure in improving knee pain and self-reported function” (p. 85).

Research has shown that patients with osteoarthritis of the knee who receive a “sham surgery” experience reductions in pain and improvement in knee function similar to those of patients who receive a real surgery.

Army Medicine – Surgery – CC BY 2.0.

Within-Subjects Experiments

In a within-subjects experiment , each participant is tested under all conditions. Consider an experiment on the effect of a defendant’s physical attractiveness on judgments of his guilt. Again, in a between-subjects experiment, one group of participants would be shown an attractive defendant and asked to judge his guilt, and another group of participants would be shown an unattractive defendant and asked to judge his guilt. In a within-subjects experiment, however, the same group of participants would judge the guilt of both an attractive and an unattractive defendant.

The primary advantage of this approach is that it provides maximum control of extraneous participant variables. Participants in all conditions have the same mean IQ, same socioeconomic status, same number of siblings, and so on—because they are the very same people. Within-subjects experiments also make it possible to use statistical procedures that remove the effect of these extraneous participant variables on the dependent variable and therefore make the data less “noisy” and the effect of the independent variable easier to detect. We will look more closely at this idea later in the book.

Carryover Effects and Counterbalancing

The primary disadvantage of within-subjects designs is that they can result in carryover effects. A carryover effect is an effect of being tested in one condition on participants’ behavior in later conditions. One type of carryover effect is a practice effect , where participants perform a task better in later conditions because they have had a chance to practice it. Another type is a fatigue effect , where participants perform a task worse in later conditions because they become tired or bored. Being tested in one condition can also change how participants perceive stimuli or interpret their task in later conditions. This is called a context effect . For example, an average-looking defendant might be judged more harshly when participants have just judged an attractive defendant than when they have just judged an unattractive defendant. Within-subjects experiments also make it easier for participants to guess the hypothesis. For example, a participant who is asked to judge the guilt of an attractive defendant and then is asked to judge the guilt of an unattractive defendant is likely to guess that the hypothesis is that defendant attractiveness affects judgments of guilt. This could lead the participant to judge the unattractive defendant more harshly because he thinks this is what he is expected to do. Or it could make participants judge the two defendants similarly in an effort to be “fair.”

Carryover effects can be interesting in their own right. (Does the attractiveness of one person depend on the attractiveness of other people that we have seen recently?) But when they are not the focus of the research, carryover effects can be problematic. Imagine, for example, that participants judge the guilt of an attractive defendant and then judge the guilt of an unattractive defendant. If they judge the unattractive defendant more harshly, this might be because of his unattractiveness. But it could be instead that they judge him more harshly because they are becoming bored or tired. In other words, the order of the conditions is a confounding variable. The attractive condition is always the first condition and the unattractive condition the second. Thus any difference between the conditions in terms of the dependent variable could be caused by the order of the conditions and not the independent variable itself.

There is a solution to the problem of order effects, however, that can be used in many situations. It is counterbalancing , which means testing different participants in different orders. For example, some participants would be tested in the attractive defendant condition followed by the unattractive defendant condition, and others would be tested in the unattractive condition followed by the attractive condition. With three conditions, there would be six different orders (ABC, ACB, BAC, BCA, CAB, and CBA), so some participants would be tested in each of the six orders. With counterbalancing, participants are assigned to orders randomly, using the techniques we have already discussed. Thus random assignment plays an important role in within-subjects designs just as in between-subjects designs. Here, instead of randomly assigning to conditions, they are randomly assigned to different orders of conditions. In fact, it can safely be said that if a study does not involve random assignment in one form or another, it is not an experiment.

There are two ways to think about what counterbalancing accomplishes. One is that it controls the order of conditions so that it is no longer a confounding variable. Instead of the attractive condition always being first and the unattractive condition always being second, the attractive condition comes first for some participants and second for others. Likewise, the unattractive condition comes first for some participants and second for others. Thus any overall difference in the dependent variable between the two conditions cannot have been caused by the order of conditions. A second way to think about what counterbalancing accomplishes is that if there are carryover effects, it makes it possible to detect them. One can analyze the data separately for each order to see whether it had an effect.

When 9 Is “Larger” Than 221

Researcher Michael Birnbaum has argued that the lack of context provided by between-subjects designs is often a bigger problem than the context effects created by within-subjects designs. To demonstrate this, he asked one group of participants to rate how large the number 9 was on a 1-to-10 rating scale and another group to rate how large the number 221 was on the same 1-to-10 rating scale (Birnbaum, 1999). Participants in this between-subjects design gave the number 9 a mean rating of 5.13 and the number 221 a mean rating of 3.10. In other words, they rated 9 as larger than 221! According to Birnbaum, this is because participants spontaneously compared 9 with other one-digit numbers (in which case it is relatively large) and compared 221 with other three-digit numbers (in which case it is relatively small).

Simultaneous Within-Subjects Designs

So far, we have discussed an approach to within-subjects designs in which participants are tested in one condition at a time. There is another approach, however, that is often used when participants make multiple responses in each condition. Imagine, for example, that participants judge the guilt of 10 attractive defendants and 10 unattractive defendants. Instead of having people make judgments about all 10 defendants of one type followed by all 10 defendants of the other type, the researcher could present all 20 defendants in a sequence that mixed the two types. The researcher could then compute each participant’s mean rating for each type of defendant. Or imagine an experiment designed to see whether people with social anxiety disorder remember negative adjectives (e.g., “stupid,” “incompetent”) better than positive ones (e.g., “happy,” “productive”). The researcher could have participants study a single list that includes both kinds of words and then have them try to recall as many words as possible. The researcher could then count the number of each type of word that was recalled. There are many ways to determine the order in which the stimuli are presented, but one common way is to generate a different random order for each participant.

Between-Subjects or Within-Subjects?

Almost every experiment can be conducted using either a between-subjects design or a within-subjects design. This means that researchers must choose between the two approaches based on their relative merits for the particular situation.

Between-subjects experiments have the advantage of being conceptually simpler and requiring less testing time per participant. They also avoid carryover effects without the need for counterbalancing. Within-subjects experiments have the advantage of controlling extraneous participant variables, which generally reduces noise in the data and makes it easier to detect a relationship between the independent and dependent variables.

A good rule of thumb, then, is that if it is possible to conduct a within-subjects experiment (with proper counterbalancing) in the time that is available per participant—and you have no serious concerns about carryover effects—this is probably the best option. If a within-subjects design would be difficult or impossible to carry out, then you should consider a between-subjects design instead. For example, if you were testing participants in a doctor’s waiting room or shoppers in line at a grocery store, you might not have enough time to test each participant in all conditions and therefore would opt for a between-subjects design. Or imagine you were trying to reduce people’s level of prejudice by having them interact with someone of another race. A within-subjects design with counterbalancing would require testing some participants in the treatment condition first and then in a control condition. But if the treatment works and reduces people’s level of prejudice, then they would no longer be suitable for testing in the control condition. This is true for many designs that involve a treatment meant to produce long-term change in participants’ behavior (e.g., studies testing the effectiveness of psychotherapy). Clearly, a between-subjects design would be necessary here.

Remember also that using one type of design does not preclude using the other type in a different study. There is no reason that a researcher could not use both a between-subjects design and a within-subjects design to answer the same research question. In fact, professional researchers often do exactly this.

Key Takeaways

- Experiments can be conducted using either between-subjects or within-subjects designs. Deciding which to use in a particular situation requires careful consideration of the pros and cons of each approach.

- Random assignment to conditions in between-subjects experiments or to orders of conditions in within-subjects experiments is a fundamental element of experimental research. Its purpose is to control extraneous variables so that they do not become confounding variables.

- Experimental research on the effectiveness of a treatment requires both a treatment condition and a control condition, which can be a no-treatment control condition, a placebo control condition, or a waitlist control condition. Experimental treatments can also be compared with the best available alternative.

Discussion: For each of the following topics, list the pros and cons of a between-subjects and within-subjects design and decide which would be better.

- You want to test the relative effectiveness of two training programs for running a marathon.

- Using photographs of people as stimuli, you want to see if smiling people are perceived as more intelligent than people who are not smiling.

- In a field experiment, you want to see if the way a panhandler is dressed (neatly vs. sloppily) affects whether or not passersby give him any money.

- You want to see if concrete nouns (e.g., dog ) are recalled better than abstract nouns (e.g., truth ).

- Discussion: Imagine that an experiment shows that participants who receive psychodynamic therapy for a dog phobia improve more than participants in a no-treatment control group. Explain a fundamental problem with this research design and at least two ways that it might be corrected.

Birnbaum, M. H. (1999). How to show that 9 > 221: Collect judgments in a between-subjects design. Psychological Methods, 4 , 243–249.

Moseley, J. B., O’Malley, K., Petersen, N. J., Menke, T. J., Brody, B. A., Kuykendall, D. H., … Wray, N. P. (2002). A controlled trial of arthroscopic surgery for osteoarthritis of the knee. The New England Journal of Medicine, 347 , 81–88.

Price, D. D., Finniss, D. G., & Benedetti, F. (2008). A comprehensive review of the placebo effect: Recent advances and current thought. Annual Review of Psychology, 59 , 565–590.

Shapiro, A. K., & Shapiro, E. (1999). The powerful placebo: From ancient priest to modern physician . Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Research Methods in Psychology. Provided by : University of Minnesota Libraries Publishing. Located at : http://open.lib.umn.edu/psychologyresearchmethods . License : CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

Privacy Policy

Random Assignment in Psychology (Definition + 40 Examples)

Have you ever wondered how researchers discover new ways to help people learn, make decisions, or overcome challenges? A hidden hero in this adventure of discovery is a method called random assignment, a cornerstone in psychological research that helps scientists uncover the truths about the human mind and behavior.

Random Assignment is a process used in research where each participant has an equal chance of being placed in any group within the study. This technique is essential in experiments as it helps to eliminate biases, ensuring that the different groups being compared are similar in all important aspects.

By doing so, researchers can be confident that any differences observed are likely due to the variable being tested, rather than other factors.

In this article, we’ll explore the intriguing world of random assignment, diving into its history, principles, real-world examples, and the impact it has had on the field of psychology.

History of Random Assignment

Stepping back in time, we delve into the origins of random assignment, which finds its roots in the early 20th century.

The pioneering mind behind this innovative technique was Sir Ronald A. Fisher , a British statistician and biologist. Fisher introduced the concept of random assignment in the 1920s, aiming to improve the quality and reliability of experimental research .

His contributions laid the groundwork for the method's evolution and its widespread adoption in various fields, particularly in psychology.

Fisher’s groundbreaking work on random assignment was motivated by his desire to control for confounding variables – those pesky factors that could muddy the waters of research findings.

By assigning participants to different groups purely by chance, he realized that the influence of these confounding variables could be minimized, paving the way for more accurate and trustworthy results.

Early Studies Utilizing Random Assignment

Following Fisher's initial development, random assignment started to gain traction in the research community. Early studies adopting this methodology focused on a variety of topics, from agriculture (which was Fisher’s primary field of interest) to medicine and psychology.

The approach allowed researchers to draw stronger conclusions from their experiments, bolstering the development of new theories and practices.

One notable early study utilizing random assignment was conducted in the field of educational psychology. Researchers were keen to understand the impact of different teaching methods on student outcomes.

By randomly assigning students to various instructional approaches, they were able to isolate the effects of the teaching methods, leading to valuable insights and recommendations for educators.

Evolution of the Methodology

As the decades rolled on, random assignment continued to evolve and adapt to the changing landscape of research.

Advances in technology introduced new tools and techniques for implementing randomization, such as computerized random number generators, which offered greater precision and ease of use.

The application of random assignment expanded beyond the confines of the laboratory, finding its way into field studies and large-scale surveys.

Researchers across diverse disciplines embraced the methodology, recognizing its potential to enhance the validity of their findings and contribute to the advancement of knowledge.

From its humble beginnings in the early 20th century to its widespread use today, random assignment has proven to be a cornerstone of scientific inquiry.

Its development and evolution have played a pivotal role in shaping the landscape of psychological research, driving discoveries that have improved lives and deepened our understanding of the human experience.

Principles of Random Assignment

Delving into the heart of random assignment, we uncover the theories and principles that form its foundation.

The method is steeped in the basics of probability theory and statistical inference, ensuring that each participant has an equal chance of being placed in any group, thus fostering fair and unbiased results.

Basic Principles of Random Assignment

Understanding the core principles of random assignment is key to grasping its significance in research. There are three principles: equal probability of selection, reduction of bias, and ensuring representativeness.

The first principle, equal probability of selection , ensures that every participant has an identical chance of being assigned to any group in the study. This randomness is crucial as it mitigates the risk of bias and establishes a level playing field.

The second principle focuses on the reduction of bias . Random assignment acts as a safeguard, ensuring that the groups being compared are alike in all essential aspects before the experiment begins.

This similarity between groups allows researchers to attribute any differences observed in the outcomes directly to the independent variable being studied.

Lastly, ensuring representativeness is a vital principle. When participants are assigned randomly, the resulting groups are more likely to be representative of the larger population.

This characteristic is crucial for the generalizability of the study’s findings, allowing researchers to apply their insights broadly.

Theoretical Foundation

The theoretical foundation of random assignment lies in probability theory and statistical inference .

Probability theory deals with the likelihood of different outcomes, providing a mathematical framework for analyzing random phenomena. In the context of random assignment, it helps in ensuring that each participant has an equal chance of being placed in any group.

Statistical inference, on the other hand, allows researchers to draw conclusions about a population based on a sample of data drawn from that population. It is the mechanism through which the results of a study can be generalized to a broader context.

Random assignment enhances the reliability of statistical inferences by reducing biases and ensuring that the sample is representative.

Differentiating Random Assignment from Random Selection

It’s essential to distinguish between random assignment and random selection, as the two terms, while related, have distinct meanings in the realm of research.

Random assignment refers to how participants are placed into different groups in an experiment, aiming to control for confounding variables and help determine causes.

In contrast, random selection pertains to how individuals are chosen to participate in a study. This method is used to ensure that the sample of participants is representative of the larger population, which is vital for the external validity of the research.

While both methods are rooted in randomness and probability, they serve different purposes in the research process.

Understanding the theories, principles, and distinctions of random assignment illuminates its pivotal role in psychological research.

This method, anchored in probability theory and statistical inference, serves as a beacon of reliability, guiding researchers in their quest for knowledge and ensuring that their findings stand the test of validity and applicability.

Methodology of Random Assignment

Implementing random assignment in a study is a meticulous process that involves several crucial steps.

The initial step is participant selection, where individuals are chosen to partake in the study. This stage is critical to ensure that the pool of participants is diverse and representative of the population the study aims to generalize to.

Once the pool of participants has been established, the actual assignment process begins. In this step, each participant is allocated randomly to one of the groups in the study.

Researchers use various tools, such as random number generators or computerized methods, to ensure that this assignment is genuinely random and free from biases.

Monitoring and adjusting form the final step in the implementation of random assignment. Researchers need to continuously observe the groups to ensure that they remain comparable in all essential aspects throughout the study.

If any significant discrepancies arise, adjustments might be necessary to maintain the study’s integrity and validity.

Tools and Techniques Used

The evolution of technology has introduced a variety of tools and techniques to facilitate random assignment.

Random number generators, both manual and computerized, are commonly used to assign participants to different groups. These generators ensure that each individual has an equal chance of being placed in any group, upholding the principle of equal probability of selection.

In addition to random number generators, researchers often use specialized computer software designed for statistical analysis and experimental design.

These software programs offer advanced features that allow for precise and efficient random assignment, minimizing the risk of human error and enhancing the study’s reliability.

Ethical Considerations

The implementation of random assignment is not devoid of ethical considerations. Informed consent is a fundamental ethical principle that researchers must uphold.

Informed consent means that every participant should be fully informed about the nature of the study, the procedures involved, and any potential risks or benefits, ensuring that they voluntarily agree to participate.

Beyond informed consent, researchers must conduct a thorough risk and benefit analysis. The potential benefits of the study should outweigh any risks or harms to the participants.

Safeguarding the well-being of participants is paramount, and any study employing random assignment must adhere to established ethical guidelines and standards.

Conclusion of Methodology

The methodology of random assignment, while seemingly straightforward, is a multifaceted process that demands precision, fairness, and ethical integrity. From participant selection to assignment and monitoring, each step is crucial to ensure the validity of the study’s findings.

The tools and techniques employed, coupled with a steadfast commitment to ethical principles, underscore the significance of random assignment as a cornerstone of robust psychological research.

Benefits of Random Assignment in Psychological Research

The impact and importance of random assignment in psychological research cannot be overstated. It is fundamental for ensuring the study is accurate, allowing the researchers to determine if their study actually caused the results they saw, and making sure the findings can be applied to the real world.

Facilitating Causal Inferences

When participants are randomly assigned to different groups, researchers can be more confident that the observed effects are due to the independent variable being changed, and not other factors.

This ability to determine the cause is called causal inference .

This confidence allows for the drawing of causal relationships, which are foundational for theory development and application in psychology.

Ensuring Internal Validity

One of the foremost impacts of random assignment is its ability to enhance the internal validity of an experiment.

Internal validity refers to the extent to which a researcher can assert that changes in the dependent variable are solely due to manipulations of the independent variable , and not due to confounding variables.

By ensuring that each participant has an equal chance of being in any condition of the experiment, random assignment helps control for participant characteristics that could otherwise complicate the results.

Enhancing Generalizability

Beyond internal validity, random assignment also plays a crucial role in enhancing the generalizability of research findings.

When done correctly, it ensures that the sample groups are representative of the larger population, so can allow researchers to apply their findings more broadly.

This representative nature is essential for the practical application of research, impacting policy, interventions, and psychological therapies.

Limitations of Random Assignment

Potential for implementation issues.

While the principles of random assignment are robust, the method can face implementation issues.

One of the most common problems is logistical constraints. Some studies, due to their nature or the specific population being studied, find it challenging to implement random assignment effectively.

For instance, in educational settings, logistical issues such as class schedules and school policies might stop the random allocation of students to different teaching methods .

Ethical Dilemmas

Random assignment, while methodologically sound, can also present ethical dilemmas.

In some cases, withholding a potentially beneficial treatment from one of the groups of participants can raise serious ethical questions, especially in medical or clinical research where participants' well-being might be directly affected.

Researchers must navigate these ethical waters carefully, balancing the pursuit of knowledge with the well-being of participants.

Generalizability Concerns

Even when implemented correctly, random assignment does not always guarantee generalizable results.

The types of people in the participant pool, the specific context of the study, and the nature of the variables being studied can all influence the extent to which the findings can be applied to the broader population.

Researchers must be cautious in making broad generalizations from studies, even those employing strict random assignment.

Practical and Real-World Limitations

In the real world, many variables cannot be manipulated for ethical or practical reasons, limiting the applicability of random assignment.

For instance, researchers cannot randomly assign individuals to different levels of intelligence, socioeconomic status, or cultural backgrounds.

This limitation necessitates the use of other research designs, such as correlational or observational studies , when exploring relationships involving such variables.

Response to Critiques

In response to these critiques, people in favor of random assignment argue that the method, despite its limitations, remains one of the most reliable ways to establish cause and effect in experimental research.

They acknowledge the challenges and ethical considerations but emphasize the rigorous frameworks in place to address them.

The ongoing discussion around the limitations and critiques of random assignment contributes to the evolution of the method, making sure it is continuously relevant and applicable in psychological research.

While random assignment is a powerful tool in experimental research, it is not without its critiques and limitations. Implementation issues, ethical dilemmas, generalizability concerns, and real-world limitations can pose significant challenges.

However, the continued discourse and refinement around these issues underline the method's enduring significance in the pursuit of knowledge in psychology.

By being careful with how we do things and doing what's right, random assignment stays a really important part of studying how people act and think.

Real-World Applications and Examples

Random assignment has been employed in many studies across various fields of psychology, leading to significant discoveries and advancements.

Here are some real-world applications and examples illustrating the diversity and impact of this method:

- Medicine and Health Psychology: Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs) are the gold standard in medical research. In these studies, participants are randomly assigned to either the treatment or control group to test the efficacy of new medications or interventions.

- Educational Psychology: Studies in this field have used random assignment to explore the effects of different teaching methods, classroom environments, and educational technologies on student learning and outcomes.

- Cognitive Psychology: Researchers have employed random assignment to investigate various aspects of human cognition, including memory, attention, and problem-solving, leading to a deeper understanding of how the mind works.

- Social Psychology: Random assignment has been instrumental in studying social phenomena, such as conformity, aggression, and prosocial behavior, shedding light on the intricate dynamics of human interaction.

Let's get into some specific examples. You'll need to know one term though, and that is "control group." A control group is a set of participants in a study who do not receive the treatment or intervention being tested , serving as a baseline to compare with the group that does, in order to assess the effectiveness of the treatment.

- Smoking Cessation Study: Researchers used random assignment to put participants into two groups. One group received a new anti-smoking program, while the other did not. This helped determine if the program was effective in helping people quit smoking.

- Math Tutoring Program: A study on students used random assignment to place them into two groups. One group received additional math tutoring, while the other continued with regular classes, to see if the extra help improved their grades.

- Exercise and Mental Health: Adults were randomly assigned to either an exercise group or a control group to study the impact of physical activity on mental health and mood.

- Diet and Weight Loss: A study randomly assigned participants to different diet plans to compare their effectiveness in promoting weight loss and improving health markers.

- Sleep and Learning: Researchers randomly assigned students to either a sleep extension group or a regular sleep group to study the impact of sleep on learning and memory.

- Classroom Seating Arrangement: Teachers used random assignment to place students in different seating arrangements to examine the effect on focus and academic performance.

- Music and Productivity: Employees were randomly assigned to listen to music or work in silence to investigate the effect of music on workplace productivity.

- Medication for ADHD: Children with ADHD were randomly assigned to receive either medication, behavioral therapy, or a placebo to compare treatment effectiveness.

- Mindfulness Meditation for Stress: Adults were randomly assigned to a mindfulness meditation group or a waitlist control group to study the impact on stress levels.

- Video Games and Aggression: A study randomly assigned participants to play either violent or non-violent video games and then measured their aggression levels.

- Online Learning Platforms: Students were randomly assigned to use different online learning platforms to evaluate their effectiveness in enhancing learning outcomes.

- Hand Sanitizers in Schools: Schools were randomly assigned to use hand sanitizers or not to study the impact on student illness and absenteeism.

- Caffeine and Alertness: Participants were randomly assigned to consume caffeinated or decaffeinated beverages to measure the effects on alertness and cognitive performance.

- Green Spaces and Well-being: Neighborhoods were randomly assigned to receive green space interventions to study the impact on residents’ well-being and community connections.

- Pet Therapy for Hospital Patients: Patients were randomly assigned to receive pet therapy or standard care to assess the impact on recovery and mood.

- Yoga for Chronic Pain: Individuals with chronic pain were randomly assigned to a yoga intervention group or a control group to study the effect on pain levels and quality of life.

- Flu Vaccines Effectiveness: Different groups of people were randomly assigned to receive either the flu vaccine or a placebo to determine the vaccine’s effectiveness.

- Reading Strategies for Dyslexia: Children with dyslexia were randomly assigned to different reading intervention strategies to compare their effectiveness.

- Physical Environment and Creativity: Participants were randomly assigned to different room setups to study the impact of physical environment on creative thinking.

- Laughter Therapy for Depression: Individuals with depression were randomly assigned to laughter therapy sessions or control groups to assess the impact on mood.

- Financial Incentives for Exercise: Participants were randomly assigned to receive financial incentives for exercising to study the impact on physical activity levels.

- Art Therapy for Anxiety: Individuals with anxiety were randomly assigned to art therapy sessions or a waitlist control group to measure the effect on anxiety levels.

- Natural Light in Offices: Employees were randomly assigned to workspaces with natural or artificial light to study the impact on productivity and job satisfaction.

- School Start Times and Academic Performance: Schools were randomly assigned different start times to study the effect on student academic performance and well-being.

- Horticulture Therapy for Seniors: Older adults were randomly assigned to participate in horticulture therapy or traditional activities to study the impact on cognitive function and life satisfaction.

- Hydration and Cognitive Function: Participants were randomly assigned to different hydration levels to measure the impact on cognitive function and alertness.

- Intergenerational Programs: Seniors and young people were randomly assigned to intergenerational programs to study the effects on well-being and cross-generational understanding.

- Therapeutic Horseback Riding for Autism: Children with autism were randomly assigned to therapeutic horseback riding or traditional therapy to study the impact on social communication skills.

- Active Commuting and Health: Employees were randomly assigned to active commuting (cycling, walking) or passive commuting to study the effect on physical health.

- Mindful Eating for Weight Management: Individuals were randomly assigned to mindful eating workshops or control groups to study the impact on weight management and eating habits.

- Noise Levels and Learning: Students were randomly assigned to classrooms with different noise levels to study the effect on learning and concentration.

- Bilingual Education Methods: Schools were randomly assigned different bilingual education methods to compare their effectiveness in language acquisition.

- Outdoor Play and Child Development: Children were randomly assigned to different amounts of outdoor playtime to study the impact on physical and cognitive development.

- Social Media Detox: Participants were randomly assigned to a social media detox or regular usage to study the impact on mental health and well-being.

- Therapeutic Writing for Trauma Survivors: Individuals who experienced trauma were randomly assigned to therapeutic writing sessions or control groups to study the impact on psychological well-being.

- Mentoring Programs for At-risk Youth: At-risk youth were randomly assigned to mentoring programs or control groups to assess the impact on academic achievement and behavior.

- Dance Therapy for Parkinson’s Disease: Individuals with Parkinson’s disease were randomly assigned to dance therapy or traditional exercise to study the effect on motor function and quality of life.

- Aquaponics in Schools: Schools were randomly assigned to implement aquaponics programs to study the impact on student engagement and environmental awareness.

- Virtual Reality for Phobia Treatment: Individuals with phobias were randomly assigned to virtual reality exposure therapy or traditional therapy to compare effectiveness.

- Gardening and Mental Health: Participants were randomly assigned to engage in gardening or other leisure activities to study the impact on mental health and stress reduction.

Each of these studies exemplifies how random assignment is utilized in various fields and settings, shedding light on the multitude of ways it can be applied to glean valuable insights and knowledge.

Real-world Impact of Random Assignment

Random assignment is like a key tool in the world of learning about people's minds and behaviors. It’s super important and helps in many different areas of our everyday lives. It helps make better rules, creates new ways to help people, and is used in lots of different fields.

Health and Medicine

In health and medicine, random assignment has helped doctors and scientists make lots of discoveries. It’s a big part of tests that help create new medicines and treatments.

By putting people into different groups by chance, scientists can really see if a medicine works.

This has led to new ways to help people with all sorts of health problems, like diabetes, heart disease, and mental health issues like depression and anxiety.

Schools and education have also learned a lot from random assignment. Researchers have used it to look at different ways of teaching, what kind of classrooms are best, and how technology can help learning.

This knowledge has helped make better school rules, develop what we learn in school, and find the best ways to teach students of all ages and backgrounds.

Workplace and Organizational Behavior

Random assignment helps us understand how people act at work and what makes a workplace good or bad.

Studies have looked at different kinds of workplaces, how bosses should act, and how teams should be put together. This has helped companies make better rules and create places to work that are helpful and make people happy.

Environmental and Social Changes

Random assignment is also used to see how changes in the community and environment affect people. Studies have looked at community projects, changes to the environment, and social programs to see how they help or hurt people’s well-being.

This has led to better community projects, efforts to protect the environment, and programs to help people in society.

Technology and Human Interaction

In our world where technology is always changing, studies with random assignment help us see how tech like social media, virtual reality, and online stuff affect how we act and feel.

This has helped make better and safer technology and rules about using it so that everyone can benefit.

The effects of random assignment go far and wide, way beyond just a science lab. It helps us understand lots of different things, leads to new and improved ways to do things, and really makes a difference in the world around us.

From making healthcare and schools better to creating positive changes in communities and the environment, the real-world impact of random assignment shows just how important it is in helping us learn and make the world a better place.

So, what have we learned? Random assignment is like a super tool in learning about how people think and act. It's like a detective helping us find clues and solve mysteries in many parts of our lives.

From creating new medicines to helping kids learn better in school, and from making workplaces happier to protecting the environment, it’s got a big job!

This method isn’t just something scientists use in labs; it reaches out and touches our everyday lives. It helps make positive changes and teaches us valuable lessons.

Whether we are talking about technology, health, education, or the environment, random assignment is there, working behind the scenes, making things better and safer for all of us.

In the end, the simple act of putting people into groups by chance helps us make big discoveries and improvements. It’s like throwing a small stone into a pond and watching the ripples spread out far and wide.

Thanks to random assignment, we are always learning, growing, and finding new ways to make our world a happier and healthier place for everyone!

Related posts:

- 19+ Experimental Design Examples (Methods + Types)

- Cluster Sampling vs Stratified Sampling

- 41+ White Collar Job Examples (Salary + Path)

- 47+ Blue Collar Job Examples (Salary + Path)

- McDonaldization of Society (Definition + Examples)

Reference this article:

About The Author

Free Personality Test

Free Memory Test

Free IQ Test

PracticalPie.com is a participant in the Amazon Associates Program. As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases.

Follow Us On:

Youtube Facebook Instagram X/Twitter

Psychology Resources

Developmental

Personality

Relationships

Psychologists

Serial Killers

Psychology Tests

Personality Quiz

Memory Test

Depression test

Type A/B Personality Test

© PracticalPsychology. All rights reserved

Privacy Policy | Terms of Use

2.3 Analyzing Findings

Learning objectives.

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Explain what a correlation coefficient tells us about the relationship between variables

- Recognize that correlation does not indicate a cause-and-effect relationship between variables

- Discuss our tendency to look for relationships between variables that do not really exist

- Explain random sampling and assignment of participants into experimental and control groups

- Discuss how experimenter or participant bias could affect the results of an experiment

- Identify independent and dependent variables

Did you know that as sales in ice cream increase, so does the overall rate of crime? Is it possible that indulging in your favorite flavor of ice cream could send you on a crime spree? Or, after committing crime do you think you might decide to treat yourself to a cone? There is no question that a relationship exists between ice cream and crime (e.g., Harper, 2013), but it would be pretty foolish to decide that one thing actually caused the other to occur.

It is much more likely that both ice cream sales and crime rates are related to the temperature outside. When the temperature is warm, there are lots of people out of their houses, interacting with each other, getting annoyed with one another, and sometimes committing crimes. Also, when it is warm outside, we are more likely to seek a cool treat like ice cream. How do we determine if there is indeed a relationship between two things? And when there is a relationship, how can we discern whether it is attributable to coincidence or causation?

Correlational Research

Correlation means that there is a relationship between two or more variables (such as ice cream consumption and crime), but this relationship does not necessarily imply cause and effect. When two variables are correlated, it simply means that as one variable changes, so does the other. We can measure correlation by calculating a statistic known as a correlation coefficient. A correlation coefficient is a number from -1 to +1 that indicates the strength and direction of the relationship between variables. The correlation coefficient is usually represented by the letter r .

The number portion of the correlation coefficient indicates the strength of the relationship. The closer the number is to 1 (be it negative or positive), the more strongly related the variables are, and the more predictable changes in one variable will be as the other variable changes. The closer the number is to zero, the weaker the relationship, and the less predictable the relationship between the variables becomes. For instance, a correlation coefficient of 0.9 indicates a far stronger relationship than a correlation coefficient of 0.3. If the variables are not related to one another at all, the correlation coefficient is 0. The example above about ice cream and crime is an example of two variables that we might expect to have no relationship to each other.

The sign—positive or negative—of the correlation coefficient indicates the direction of the relationship ( Figure 2.12 ). A positive correlation means that the variables move in the same direction. Put another way, it means that as one variable increases so does the other, and conversely, when one variable decreases so does the other. A negative correlation means that the variables move in opposite directions. If two variables are negatively correlated, a decrease in one variable is associated with an increase in the other and vice versa.

The example of ice cream and crime rates is a positive correlation because both variables increase when temperatures are warmer. Other examples of positive correlations are the relationship between an individual’s height and weight or the relationship between a person’s age and number of wrinkles. One might expect a negative correlation to exist between someone’s tiredness during the day and the number of hours they slept the previous night: the amount of sleep decreases as the feelings of tiredness increase. In a real-world example of negative correlation, student researchers at the University of Minnesota found a weak negative correlation ( r = -0.29) between the average number of days per week that students got fewer than 5 hours of sleep and their GPA (Lowry, Dean, & Manders, 2010). Keep in mind that a negative correlation is not the same as no correlation. For example, we would probably find no correlation between hours of sleep and shoe size.