An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- HHS Author Manuscripts

Belonging: A Review of Conceptual Issues, an Integrative Framework, and Directions for Future Research

Kelly-ann allen.

1 Educational Psychology and Inclusive Education, Faculty of Education, Monash University, Clayton Australia.

2 Centre for Positive Psychology, Melbourne Graduate School of Education, The University of Melbourne, Parkville, Australia.

Margaret L. Kern

Christopher s. rozek.

3 Department of Education, Washington University in St. Louis, U.S.A.

Dennis McInereney

4 Department of Special Education and Counselling, The Education University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong.

George M. Slavich

5 Cousins Center for Psychoneuroimmunology and Department of Psychiatry and Biobehavioral Sciences, University of California, Los Angeles, U.S.A.

A sense of belonging—the subjective feeling of deep connection with social groups, physical places, and individual and collective experiences—is a fundamental human need that predicts numerous mental, physical, social, economic, and behavioural outcomes. However, varying perspectives on how belonging should be conceptualised, assessed, and cultivated has hampered much-needed progress on this timely and important topic. To address these critical issues, we conducted a narrative review that summarizes existing perspectives on belonging, describes a new integrative framework for understanding and studying belonging, and identifies several key avenues for future research and practice.

We searched relevant databases, including Google Scholar, PubMed, Scopus, PsycInfo, and ClinicalTrials.gov, for articles describing belonging, instruments for assessing belonging, and interventions for increasing belonging.

By identifying the core components of belonging, we introduce a new integrative framework for understanding, assessing, and cultivating belonging that focuses on four interrelated components: competencies, opportunities, motivations, and perceptions.

Conclusion:

This integrative framework enhances our understanding of the basic nature and features of belonging, provides a foundation for future interdisciplinary research on belonging and belongingness, and highlights how a robust sense of belonging may be cultivated to improve human health and resilience for individuals and communities worldwide.

Although the importance of social relationships, cultural identity, and — especially for indigenous people — place have long been apparent in research across multiple disciplines (e.g., Baumeister & Leary, 1995 ; Cacioppo, & Hawkley, 2003 ; Carter et al., 2017; Maslow, 1954 ; Rouchy, 2002 ; Vaillant, 2012), the year 2020 — with massive bushfires in Australia and elsewhere destroying ancient lands, the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic, and the Black Lives Matter movement in the U.S., amongst other events — brought the importance of belonging to the forefront of public attention. Belonging can be defined as a subjective feeling that one is an integral part of their surrounding systems, including family, friends, school, work environments, communities, cultural groups, and physical places ( Hagerty et al., 1992 ). Most people have a deep need to feel a sense of belonging, characterized as a positive but often fluid and ephemeral connection with other people, places, or experiences ( Allen, 2020a ).

There is general agreement that belonging is a fundamental human need that all people seek to satisfy ( Baumeister & Leary, 1995 ; Deci & Ryan 2000 ; Leary & Kelly, 2009 ; Maslow 1954 ). However, there is less agreement about the belonging construct itself, how belonging should be measured, and what people can do to satisfy the need for belonging. These issues arise in part because the belonging literature is broad and theoretically diverse, with authors approaching the topic from many different perspectives, with little integration across these perspectives. Therefore, there is a clear need to bring together disparate perspectives to understand better belonging as a construct, how it can be assessed, and how it can be developed. This narrative review describes several central issues in belonging research, bringing together disparate perspectives on belonging and harnessing the strengths of the multitude of perspectives. We also present an integrative framework on belonging and consider implications of this framework for future research and practice.

A need to belong — to connect deeply with other people and secure places, to align with one’s cultural and subcultural identities, and to feel like one is a part of the systems around them — appears to be buried deep inside our biology, all the way down to the human genome ( Slavich & Cole, 2013 ). Physical safety and well-being are intimately linked with the quality of human relationships and the characteristics of the surrounding social world (Hahn, 2017), and connection with other people and places is crucial for survival ( Boyd & Richerson, 2009 ). Indeed, for Indigenous people, “others” and “place” are synonymous and are inextricably entwined, where country provides a deep sense of belonging and identity as Aboriginal people ( Harrison & McLean, 2017 ).

The so-called “need to belong” has been observed at both the neural and peripheral biological levels (e.g., Blackhart et al., 2007 ; Kross et al., 2007 ; Slavich et al., 2014 ; Slavich, Way et al., 2010 ), as well as behaviourally and socially (e.g., Brewer, 2007 ; Filstad et al., 2019 ). Disparate research lines suggest that the principal design of the human brain and immune system is to keep the body biologically and physically safe by motivating people to avoid social threats and seek out social safety, connection, and belonging ( Slavich, 2020 ). Indeed, a sense of belonging may be just as important as food, shelter, and physical safety for promoting health and survival in the long run ( Baumeister & Leary, 1995 ; Maslow, 1954 ).

A Dynamic, Emergent Construct

Although belonging occurs as a subjective feeling, it exists within a dynamic social milieu. Biological needs complement, accentuate, and interact with social structures, norms, contexts, and experiences ( Slavich, 2020 ). Social, cultural, environmental, and geographical structures, broadly defined, provide an orientation for the self to determine who and what is acceptable, the nature of right and wrong, and a sense of belonging or alienation ( Allen, 2020 ). The sense of self emerges from one’s predominant social and environmental contexts, reinforcing and challenging the subjective sense of belonging. Belonging is facilitated and hindered by people, things, and experiences of the social milieu, which dynamically interact with the individual’s character, experiences, culture, identity, and perceptions. That is, belonging exists “because of and in connection with the systems in which we reside” ( Kern et al., 2020 , p. 709).

Despite its importance, many people struggle to feel a sense of belonging. Socially, a significant portion of people suffer from social isolation, loneliness, and a lack of connection to others ( Anderson & Thayer, 2018 ). For example, in 2017, in Australia, half of the adults reported lacking companionship at least some of the time, and one in four adults could be classified as being lonely ( Australian Psychological Society, 2018 ). Similar findings have been reported in the United States, where 63% of men and 58% of women reported feeling lonely ( Cigna, 2018 ). Social disconnection has become a concerning trend across many developed cultures for several reasons, including social mobility, shifts in technology, broken family and community structures, and the pace of modern life ( Baumeister & Robson, 2021 ). The COVID-19 pandemic magnified and accelerated the struggles that already existed. Early studies pointed to increases in loneliness and mental illness, especially among vulnerable populations, that is caused at least in part from extended periods of isolation, social distancing, and rising distrust of others ( Ahmed et al., 2020 ; Allen, 2020b ; Dsouza et al., 2020 ; Gruber et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2020 ).

Struggles to belong are particularly evident in minorities and other groups that have been historically excluded from mainstream culture. For instance, even as many Indigenous people experience a sense of well-being when they connect with and participate in their traditional culture (e.g., Colquhoun & Dockery, 2012 ; Dockery 2010 ; O’Leary, 2020 ), many Aboriginal people also experience ongoing grief from country dispossession ( Williamson et al., 2020 ). As bushfires ravaged Australian lands early in 2020, the grief of the fires was significantly worse than nonIndigenous people, as they not only watched the fires decimate their land, but also their memories, sacred places, and the hearts of who they are as a people ( Williamson et al., 2020 ). Several months later, the killing of George Floyd, a Black man in the U.S., initiated protests worldwide that provided a sense of meaning in connecting with others against racism ( Ramsden, 2020 ), bringing to light the systemic exclusions that Black people have long experienced in the U.S. and beyond ( Corbould, 2020 ; Yulianto, 2020 ).

A Narrative Review of Belonging Research

With this background in mind, we narratively review existing studies on belonging, considering different perspectives on how belonging has been defined and operationalised, along with correlates, predictors, and outcomes associated with belonging. Although belonging is not merely the opposite of loneliness, social isolation, or feelings of disconnection, across the literature, low and high belonging have been placed on a continuum conceptually ( Allen & Kern, 2017 , 2019 ; for a review of belonging and loneliness, see Lim et al., 2021 ). Furthermore, because of the shared similarities and close relationships between the constructs, we include studies that have considered the presence of belonging, low levels of belonging, and disconnection indicators.

Defining Belonging

The constructs of “belonginess” and “belonging” lack conceptual clarity and consistency across studies, hence limiting advances in this research field. Belonging has been defined and operationalised in several ways (e.g., Goodenow, 1993 ; Hagerty & Patusky, 1995 ; Malone et al., 2012 ; Nichols & Webster, 2013 ), which has enabled investigators to test whether interventions increase a sense of belonging over days, weeks, or months. However, definitions have often explicitly focused on social belonging, thus missing other essential aspects, such as connection to place and culture, and the dynamic interactions with the social milieu, as described above.

Because of the increased importance of belonging during adolescence, much of the research on belonging has involved students in school settings ( Abdollahi et al., 2020 ; Arslan et al., 2020 ; Yeager et al., 2018 ). Definitions have tended to include school-based experiences, relationships with peers and teachers, and students’ emotional connection with or feelings toward their school ( Allen et al., 2016 , 2018 ; Allen & Bowles, 2012 ; O’Brien & Bowles, 2013 ; Slaten et al., 2016 ). Goodenow and Grady’s (1993) definition remains the most common definition: “the extent to which students feel personally accepted, respected, included, and supported by others in the school social environment” (p. 80).

A distinction can be made between trait (i.e., belonging as a core psychological need) and state (i.e., situation-specific senses of belonging) belongingness. Studies suggest that state belonging is influenced by various daily life events and stressors ( Ma, 2003 ; Sedgwick & Rougeau, 2010 ; Walton & Cohen, 2011 ). Depending on the variability of situations and experiences that one encounters, along with one’s perceptions of those situations and experiences, a person’s subjective sense of belonging can change as frequently as several times a day in much the same way that happiness and other emotions change over time ( Trampe et al., 2015 ). However, people can also have relatively stable experiences of belonging. For example, some individuals demonstrate generally high or low levels of belonging with relatively little variability across time and different situations. In contrast, for others, a sense of belonging is more variable, depending on one’s awareness of and perceptions of environmental context and social cues (Schall et al., 2013). For instance, whereas one individual might perceive a smile from a coworker as a sign that they are part of a community, another might suspect a contrived behaviour and see it as a sign of exclusion. Indeed, research suggests that the effects of belonging-related stressors can be more intense for those who identify with outgroups ( Walton & Brady, 2017 ). Such outgroups include those from racial minorities, those who identify as sexually or gender diverse, or individuals with behaviours, attributes, or abilities that depart from the social norm, such as those that stem from mental health issues ( Gardner et al., 2019 ; Harrist & Bradley, 2002 ; Rainey et al., 2018 ; Spencer et al., 2016 ; Steger & Kashdan, 2009 ).

It appears that multiple processes must converge for a stable, trait-like sense of belonging to emerge and support well-being and other positive outcomes ( Cacioppo et al., 2015 ; Erzen & Çikrikci, 2018 ; Mellor et al., 2008 ; Rico-Uribe et al., 2018 ; Walton & Cohen, 2011 ). For instance, a successful singer is motivated to sing and has skills and capacity to sing well, confidence, opportunities to sing, and support by others. It would seem that trait belongingness is more crucial for mental health and well-being; that is, a more stable and lasting sense of belonging as opposed to a state of belonging (i.e., a temporary feeling of belonging based on thoughts, feelings, and behaviours ( Clark et al., 2003 ).

Assessing Belonging

Several different instruments have been used to assess belonging, but there is no consensus, gold-standard measure. The differentiation between state and trait belongingness has made defining and measuring belonging even more complicated. Most belonging measures are unidimensional, subjective, and static, representing a snapshot of a person’s perception at the administration time. Instruments such as Walton’s measures of belonging and belonging uncertainty have been used in many studies within education and social psychology ( Pyne, Rozek, & Borman, 2018 ; Walton & Cohen, 2007 ). These measures assess belonging from a more state-based sense of belonging, capturing transitory feelings of belonging or lack of situation-specific belonging ( Walton, 2014 ; Walton & Brady, 2017 ). Other measures, such as the UCLA Loneliness Scale, potentially assess a more stable, trait-like sense of belonging, pointing to belonging as a core psychological need ( Mahar et al., 2014 ). It could be argued that commonly used belonging measures are more accurate in assessing state-like experiences due to their propensity to assess belonging in a single snapshot of time ( Cruwys et al., 2014 ; Feser, 2020; Leary et al., 2013 ; Martin, 2007 ). This is also the case with more applied belonging studies, such as those focused on school belonging ( Allen et al., 2018 ; Arslan & Allen, 2020 ).

Given that no single measure of belonging exists, research has examined numerous belonging surveys to identify commonalities that can be applied across a variety of disciplines. Mahar et al. (2014) reviewed several instruments for assessing belongingness and found that belonging was often measured as related to the performance indicators of specific types of service organisations. For example, the sense of belonging to a church congregation may depend on the amount of support one receives from that congregation while belonging to a university is dependent not just on social connections but also on how well a student performs academically. Therefore, every social science discipline, unfortunately, has its own measure and scale of belonging.

However, there are some commonalities in all of the studies reviewed by Maher et al. (2014). First, a sense of belonging is based on an individual’s perception of their connection to a chosen group or place. Most instruments Maher and colleagues reviewed contained at least one question that referenced the feeling of belonging, whether to a large group such as a country or race or a small group such as a church or school. Second, the sense of belonging is dependent on opportunities for interaction with others. Each survey reviewed referenced this variable differently, using words such as “relationships,” “making friends,” “spending time,” and “bonding.” Whatever term is used, the instruments all appear to be measuring the same thing — namely, the opportunities a person has to belong to a desired group.

A few scales specifically ask respondents to evaluate their motivations to connect and build relationships with a desired group. Motivations appear to be an area of importance that is often ignored in previous survey tools. The importance of this element will be further explored below.

In addition, several measures consider the ability to belong. Specifically, does the individual have the social skills and abilities it takes to belong to a group? The reviewed instruments might include a question such as “I find it easy to make friends” ( Mahar et al., 2014 , p. 23); however, the questions do not specifically address whether an individual is unable to belong to the desired group because of their behaviours or attitudes.

Correlates, Predictors, and Outcomes Associated with Belonging

Regardless of how belonging has been defined and measured, the fundamental importance of belonging combined with elevated levels of social disconnection evident in modern society has led to several fruitful research and application areas. A sense of belonging has been used as a dependent, independent, and correlated variable in a wide range of studies demonstrating the salience of this construct across various contexts (e.g., Allen et al., 2018 ; Freeman et al., 2007 ). For instance, Mahar et al. (2014) reviewed how a sense of belonging was measured and actioned as a service outcome among persons with intellectual and developmental disabilities, concluding that belonging is an important outcome in this domain. Other studies have found a positive association between students’ belonging needs and psychological well-being ( Karaman & Tarim, 2018 ; Kitchen et al., 2015 ). Undergraduates’ involvement in courses that use technology was related to higher belonging levels ( Long, 2016 ). Additionally, a sense of belonging positively relates to persistence in course study ( Akiva et al., 2013 ; Hausmann et al., 2007 ; Moallem, 2013 ). Across these and other studies, greater belonging is consistently associated with more positive psychosocial outcomes.

Other studies have considered the implications for belonging interventions that target (a) characteristics of the individual including personality, social skills, and cognitions (e.g., Durlak et al., 2011 ; Frydenberg et al., 2004 ; Walton & Cohen, 2011 ); (b) their social relationships (e.g., Aron et al., 1997 ; Kanter et al., 2018 ); or (c) the environment that individuals inhabit, such as the physical attributes of the workplace, sense of space, and opportunities to connect (e.g., Gustafson, 2009 ; Jaitli & Hua, 2013 ; Trawalter et al., 2020 ). Most intervention studies have treated belonging as a secondary outcome rather than directly targeting belonging ( Allen et al., 2020 ), although there are some exceptions. For instance, in a brief social belonging intervention in a college setting for Black Americans, positive effects appeared to be long-lasting (i.e., from 7 to 11 years; Brady et al., 2020 ). A brief social belonging intervention among minority students had positive impacts on academic and health outcomes among minority students by encouraging students to understand that the feeling of not belonging is normal and temporary ( Walton & Cohen, 2011 ). Additionally, Borman et al. (2019) found that improvement in students’ sense of belonging partially mediated the effects of a similar intervention on academic achievement and disciplinary problems in secondary school.

Other studies have examined the benefits that arise from a sense of belonging. Studies have identified numerous positive effects of having a healthy sense of belonging, including more positive social relationships, academic achievement, occupational success, and better physical and mental health (e.g., Allen et al., 2018 , Goodenow & Grady, 1993 , Hagerty et al., 1992 ). A lack of belonging, in turn, has been linked to an increased risk for mental and physical health problems ( Cacioppo et al., 2015 ; Hari, 2019 ). Indeed, a meta-analysis of 70 studies concluded that the health risks of social isolation are equivalent to smoking 15 cigarettes a day and is twice as harmful as obesity ( Holt-Lunstad et al., 2015 ). Likewise, studies have found that deficits in social relationships across the lifespan are associated with depression, poor sleep quality, rapid cognitive decline, cardiovascular difficulties, and reduced immunity ( Hawkley & Capitanio, 2015 ). More specifically, the adverse effects of not belonging or being rejected include increased risk for mental illness, antisocial behaviour, lowered immune functioning, physical illness, and early mortality (e.g., Cacioppo & Hawkley, 2003 ; Cacioppo et al., 2011 ; Choenarom et al., 2005 ; Cornwell & Waite, 2009 ; Holt-Lunstad, 2018 ; Leary, 1990 ; Slavich, O’Donovan, et al., 2010 ).

An Integrative Framework for Belonging

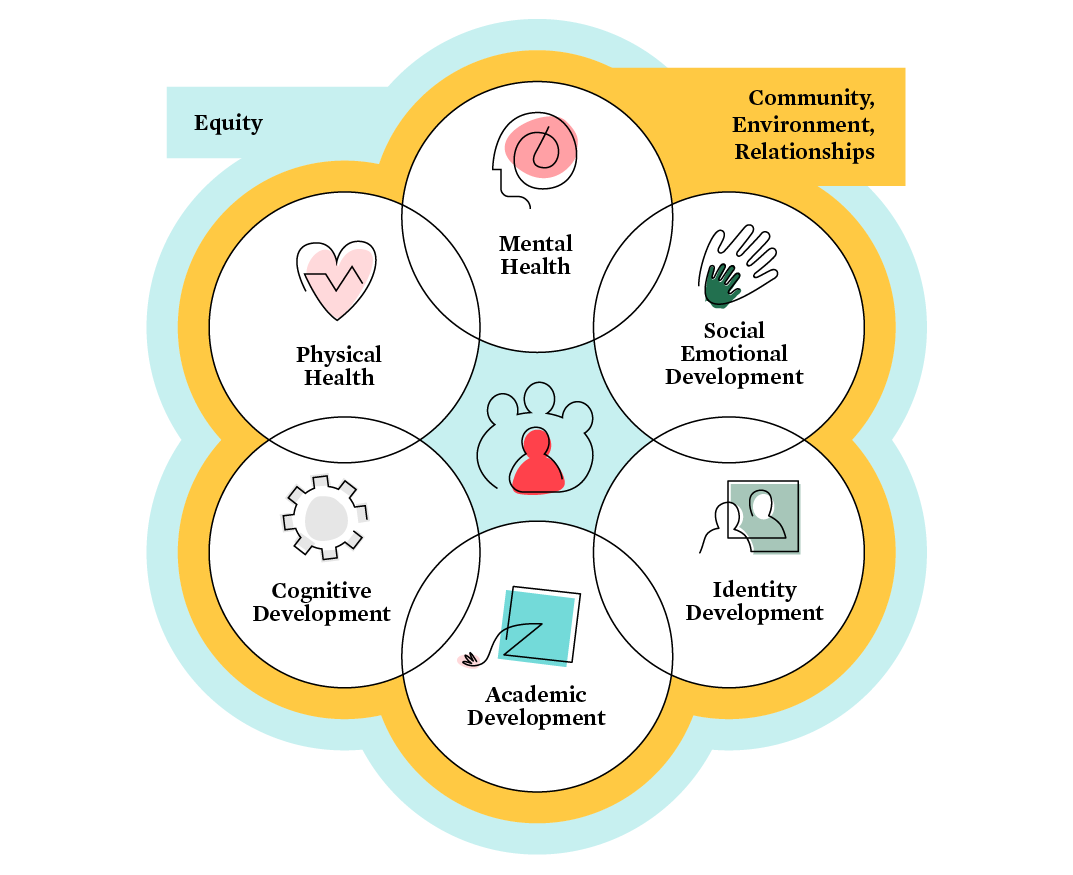

From this review, the take-home message is that belonging is a central construct in human health, behaviour, and experience. However, studies on this topic have used inconsistent terminology, definitions, and measures. At times, belonging has been treated as a predictor, outcome, correlate, and covariate. Therefore, it is unclear whether the lack of a sense of belonging is equivalent to negative constructs such as loneliness, disconnection, and isolation, or if these are separate dimensions. These inconsistencies arise, in part, from the multiple theoretical and empirical perspectives present in the belonging literature. Building on these different perspectives and insights, we propose an integrative framework to conceptualise belonging measures and inform interventions. In brief, we suggest that belonging is a dynamic feeling and experience that emerges from four interrelated components that arise from and are supported by the systems in which individuals reside. As illustrated in Figure 1 , the four components are:

- competencies for belonging (skills and abilities);

- opportunities to belong (enablers, removal/ reduction of barriers);

- motivations to belong (inner drive); and

- perceptions of belonging (cognitions, attributions, and feedback mechanisms — positive or negative experiences when connecting).

As a dynamic social system, these four components dynamically reinforce and influence one another over time, as a person moves through different social, environmental, and temporal contexts and experiences. Together they dynamically interact with, are supported or hindered by, and impact relevant social milieus. The narrative of how these components interconnect results in consistently high belonging levels, which support positive life outcomes.

An integrative framework for understanding, assessing, and fostering belonging. Four interrelated components (i.e., Competencies, Opportunities, Motivations, and Perceptions) dynamically interact and influence one another, shifting, evolving, and adapting as an individual traverses temporal, social, and environmental contexts and experiences.

Competencies for Belonging

The first component we suggest belonging emerges from is competencies : having a set of (both subjective and objective) skills and abilities needed to connect and experience belonging. Skills enable individuals to relate with others, identify with their cultural background, develop a sense of identity, and connect to place and country. Competencies enable people to ensure that their behaviour is consistent with group social norms, align with cultural values, and treat the place and land with respect. The development of social competencies is central to social and emotional learning approaches (e.g., CASEL, 2018 ), and plays a critical role in supporting positive youth development ( Durlak et al., 2011 ; Kern et al., 2017). In turn, social competencies deficits can limit relationship quality, social relations, and social positions ( Frostad & Pijl, 2007 ).

With some exceptions, most people can develop skills to improve their ability to connect with people, things, and places. Social skills include being aware of oneself and others, emotion and behaviour regulation, verbal and nonverbal communication, acknowledgement and alignment with social norms, and active listening ( Blackhart et al., 2011 ). Cultural skills include understanding one’s heritage, mindful acknowledgement of place, and alignment with relevant values. Social, emotional, and cultural competencies complement and reinforce one another, and contribute to and are reinforced by feeling a sense of belonging. The ability to regulate emotions, for example, may reduce the likelihood of social rejection or ostracisation from others ( Harrist & Bradley, 2002 ). Competencies can also help individuals cope effectively with feelings of not belonging when they arise ( Frydenberg et al., 2009 ). Pointing to the social nature of competencies, the display and use of skills may be socially reinforced through acceptance and inclusion, while feeling a sense of belonging may also assist in using socially appropriate skills ( Blackhart et al., 2011 ).

Opportunities to Belong

The second component we suggest belonging emerges from is opportunities : the availability of groups, people, places, times, and spaces that enable belonging to occur. The ability to connect with others is useless if opportunities to connect are lacking. For instance, studies with people from rural or isolated areas, first- and second-generation migrants, and refugees have found that these groups have more difficulty managing psychological well-being, physical health, and transitions ( Correa-Velez et al., 2010 ; Keyes & Kane, 2004 ). They might have social competencies, but their circumstances limit opportunities. For example, Correa-Velez et al. (2010) studied nearly 100 adolescent refugees who had been in Melbourne, Australia, for three years or less. Even with deliberate steps taken to help the students integrate into their new schools, including language development, they overwhelmingly reported feelings of discrimination and bullying. They subsequently reported a lower sense of well-being. Although these students had the skills to connect with their schoolmates, they were not given opportunities to connect. Similarly, legacies of racism, dispossession, and assimilation have continued to exclude Aboriginal people from connecting with and managing their homelands ( Williamson et al., 2020 ).

The need for opportunities became poignantly evident during the COVID-19 pandemic, as social distancing was enforced in countries around the world, and many human interactions went virtual. Active membership of extracurricular groups, schools, universities, workplaces, church groups, families, friendship groups, and participation in hobbies provide opportunities for human connections. For instance, school attendance is a prerequisite for students to feel a sense of belonging with their school ( Akar-Vural et al., 2013 ; Bowles & Scull, 2018). In the absence of physical opportunities for belonging, technologies such as social media and online gaming may help meet this need, especially for youth ( Allen et al., 2014 ; Davis, 2012 ) and for those who are introverted, shy, or who suffer from social anxiety ( Amichai-Hamburger et al., 2002 ; Moore & McElroy, 2012 ; Ryan et al., 2017 ; Seabrook et al., 2016 ; Seidman, 2013 ). However, it remains uncertain the extent to which technologically mediated approaches can fully compensate for face-to-face relationships.

The Black Lives Matter movement particularly points to opportunities for those that are often excluded by building social capital that strengthens connections, allows activists to share their messages, and illuminates the inequities existing within and across cultures. In Putnam’s (2000) work on social capital identified social networks as fundamental principles for creating opportunity. Putnam described the concepts of bridging and bonding social capital, in which the former was later referred to as inclusive belonging, whereas the latter pertains to exclusive belonging ( Putnam, 2000 ; Roffey, 2013 ). Bridging social capital is inclusive because it creates broader social networks and a higher degree of social reciprocity between members ( Putnam, 2000 ). Whereas bonding social capital highlights the connections found within a community of people sharing similar characteristics or backgrounds, including interests, attitudes, and demographics ( Claridge, 2018 ). This might be observed with close friends and family members ( Claridge, 2018 ) or other homogenous groups such as a church-based women’s reading group or an over-50s mens’ basketball team ( Putnam 2000 ). In contrast, bridging social capital may emerge from the connection people build to share their resources ( Murray et al., 2020 ). Most members are interconnected through this type of social capital, which transcends class, race, religion, and sociodemographic characteristics. Bridging social capital occurs when there is an opportunity for any person to interact with others (Putnam, 2010). This might look like a sporting event, a gathering of concerned about a common concern like climate change or racism, or even attendance at a public concert. In the same way, inclusive belonging represents mutual benefits for all parties involved. In contrast, exclusive belonging presents the idea that a selected group will benefit from membership, particularly those who are members of the group ( Roffey, 2013 ). Communities and organisations can employ inclusive belonging principles that may improve the experience of belonging for people, particularly vulnerable to rejection and prone to social isolation and loneliness ( Allen et al., 2019 ; Roffey, 2013 ; Roffey et al., 2019 ).

There are numerous ways for individuals, groups, and communities to create opportunities for belonging, and some of these opportunities can even be motivated by a sense of not belonging ( Leary & Allen, 2011 ; London et al., 2007 ). For example, those who have been disenfranchised, have suffered abuse or trauma, or have been ostracised or rejected may look for alternative sources for belonging ( Gerber & Wheeler, 2009 ; Hagerty et al., 2002 ). This search for belonging outside, or in opposition to, established norms provides one explanation for the rise of radicalisation and extremism ( Leary et al., 2006 ; Lyons-Padilla et al., 2015 ), participation in gangs and organised crime ( Voisin et al., 2014 ), and school violence ( Leary et al., 2003 ). It can also be an incentive for more socially acceptable pathways to belonging, such as through joining support groups, or bonding together with diverse others to fight against racism ( Ramsden, 2020 ). At individual, institutional, and societal levels, there is a need to create opportunities and reduce barriers to allow positive connection to occur so that people are less likely to seek out problematic contexts for belonging.

Motivations to Belong

The third component we suggest belonging emerges from is motivations : a need or desire to connect with others. Belonging motivation refers to the fundamental need for people to be accepted, belong, and seek social interactions and connections ( Leary & Kelly, 2009 ). Socially, a person who is motivated to belong is someone who enjoys positive interactions with others, seeks out interpersonal connections, has positive experiences of long-term relationships, dislikes negative social experiences, and resists the loss of attachments ( Baumeister & Leary, 1995 ). In social situations, people who are motivated to belong will actively seek similarities and things in common with others. This characteristic may not always be accounted for by personality type or attributes ( Leary & Kelly, 2009 ). Similarly, a person might be motivated to connect with a place, their culture or ethnic background, or other belonging contributors.

The degree to which people are motivated to belong varies ( Leary & Kelly, 2009 ). Weak motivation to belong can be associated with psychological dysfunction ( Baumeister & Leary, 1995 ), and weak motivation may, alongside other socially mediated criteria, become a predictor of psychological pathology ( Leary & Kelly, 2009 ). A lack of motivation may arise in part from repeated rejection and thwarting of one’s basic psychological needs of relatedness, competence, and autonomy (Deci & Ryan, 2001), resulting in a learned helplessness response ( Nelson et al., 2019 ) that manifests as a reduced motivation to belong. Nevertheless, Baumeister and Leary (1995) suggest that people can still be driven and motivated to connect with others, even under the most traumatic circumstances.

Hence, individual differences and context play central roles in our understanding of belonging motivation. The range of possible motivators for belonging are vast and will reflect diverse sociocultural and economic environments such as indigenous-non-indigenous, collectivist-individualist, urban-rural, developed-developing. It is essential that any examination of the nature and function of motivators of belonging acknowledges this diversity and includes it in any conceptualisation of this construct.

Perceptions of Belonging

The fourth component we suggest belonging emerges from is perceptions : a person’s subjective feelings and cognitions concerning their experiences. A person may have skills related to connecting, opportunities to belong, and be motivated, yet still report great dissatisfaction. Either consciously or subconsciously, most human beings evaluate whether they belong or fit in with those around them ( Baumeister & Leary, 1995 ; Walton & Brady, 2017 ).

Perceptions about one’s experiences, self-confidence, and desire for connection can be informed by past experiences ( Coie, 2004 ). For example, a person with a history of rejection or ostracization might question their belonging or seek to belong through other means ( London et al., 2007 ). This seeking could involve groups that are considered to be antisocial, such as cults, street or criminal gangs or group memberships characterised by radicalised social, political or religious ideas ( Hunter, 1998 ). This might involve returning to one’s home or place of origin or trying to find one’s place within a world that has systemically erased their value. A rejected student may engage in maladaptive behaviours in a classroom to seek approval from peers ( Flowerday & Shaughnessy, 2005 ). Indeed, in one study, indigenous children reported underperforming at school so that they would not be ostracised from their group ( McInerney, 1989 ). In other words, maintaining belonging with their indigenous peers was more salient than doing well at school; doing well at school was a white thing ( Herbert et al., 2014 ; McInerney, 1989 ). It was also apparent that perceptions of themselves as successful students (i.e., a feeling of belongingness at school) were weak for many Indigenous students but for “adaptive” reasons. Repeated social rejection experiences can create the perception (by both the individual and others who witness the repeated social rejection) that the person is not socially acceptable ( Walton & Cohen, 2007 ). Negative perceptions of the self or others, stereotypes, and attribution errors can also undermine motivation ( Mello et al., 2012 ; Walton & Wilson, 2018 ; Yeager & Walton, 2011 ). These subjective experiences and perceptions of those experiences thus act as feedback mechanisms that increase or decrease one’s desire to connect with others.

Just as the need to belong can shape emotions and cognitions ( Baumeister & Leary, 1995 ; Lambert et al., 2013 ), cognitions and emotions also impact a person’s capacities, opportunities, and motivations for belonging. To address these links and help enhance belonging, a variety of psychosocial interventions grounded in cognitive therapy aim to (a) reframe cognitions concerning negative social interactions and experiences, (b) normalise feelings of not belonging that everyone experiences from time to time, and (c) alter the extent to which the events that caused the feeling are internal vs. external to the individual (e.g., Walton & Cohen, 2007 ). These interventions have been shown to alter not just cognitions about other people and the world ( Borman et al., 2019 ; Butler et al., 2006 ) but also basic biological processes involved in the immune system that are known to affect human health and behaviour ( Shields et al., 2020 ).

Implications for Research and Practice

As we have alluded to, belonging research has been the subject of decades of development and broad multidisciplinary input and insights. As a result of this history, though, perspectives on this topic are highly diverse, as are methods for assessing this construct. Strategies for enhancing a sense of belonging exist, but identifying effective solutions depends on integrating multiple disciplinary approaches to theory, research, and practice, rather than relying on the silos of single disciplines. Arising from the framework described above, we point to six main challenges and issues related to understanding, measuring, and building belonging, highlighting areas that would benefit from additional attention and research.

First, belonging research has occurred within multiple disciplines but primarily siloed into separate domains. Understanding and support for belonging is a subject of concern in many fields, including psychology ( Baumeister & Leary, 1995 ), sociology ( May, 2011 ), education ( Morieson et al., 2013 ), urban education ( Riley, 2017 ), medicine ( Cacioppo & Hawkley, 2003 ), public health ( Stead et al., 2011 ), economics ( Bhalla & Lapeyre, 1997 ), design ( Schein, 2009 ; Trudeau, 2006 ; Weare, 2010 ), and political science ( Yuval-Davis, 2006 ). However, little work has integrated these different disciplines’ findings, with differing language, measures, and approaches used, yielding a fractured and inconsistent perspective on belonging. Thus, there is a need for authentic attempts to synthesise these findings fully and integrate, develop, and extend belonging research through genuinely interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary approaches ( Choi & Pak, 2006 ). Our integrative framework provides an initial attempt at bringing these different perspectives together, but the extent to which it is sufficient and applicable within different disciplines remains to be seen.

Second, there is a need for belonging researchers to develop a more robust understanding of the existing literature. The theoretical, methodological, and conceptual gaps need to be bridged to make this literature much more widely accessible. Knowledge development in this area will lead to improved research measurement and practitioner tools, potentially based on multitheoretical, empirically driven perspectives that will, in turn, make the bridging of future theory, research, practice, and lived application easier for all stakeholders. Our framework provides an initial organising structure to map out the literature, identify gaps, and support further knowledge development in the future. Numerous theories across disciplines contribute to each of the components, and future work could identify how different theories map onto, intersect with, and inform understanding, assessment, and enhancement of belonging.

Third, there are significant gaps between research and practice in the context of belonging. One important factor contributing to this gap is the sheer breadth and complexity of belonging research. Thus, researchers in this field make conscious — and conscientious — efforts to collaborate and translate their work to and for other researchers and practitioners. We suggest that our framework provides an accessible entry point into the research for practitioners. The four components provide specific areas to focus interventions, identifying enablers and barriers of each of the components. Building belonging begins with a need to ensure that communities have a foundational understanding of the importance of belonging for psychological and physical health and that individuals can draw on and advance their competencies, opportunities, motivations, and perceptions to increase their sense of belonging. Still, there is a need to identify specific strategies within each component that can help people develop and harness their competencies, opportunities, motivations, and perceptions across different situations, experiences, and interactions.

Fourth, consideration needs to be given to how belonging is best measured. Existing instruments for assessing belonging primarily focus on social belonging, rather than on the broader, more inclusive construct of a sense of belonging as a whole. It is unclear whether positive and negative aspects of belonging are unidimensional or multidimensional. For instance, positive affect is not merely the absence of negative affect. Positive cognitive biases are different from low levels of negative cognitive bias, and disengagement is not necessarily the same as low engagement levels. Belonging and loneliness tend to be inversely correlated ( Mellor et al., 2008 ), but the extent to which this is true across different individuals and contexts, and depends upon the measures used, is unknown.

Existing measures also generally provide a state-like assessment of a person’s sense of belonging (i.e., at a given point in time). However, as a dynamic emergent construct, measuring and targeting singular (or even multiple) components in a fixed manner is insufficient. Studies will benefit by examining the best way to capture and track dynamic patterns and identifying (a) when and how a sense of belonging emerges from competencies, opportunities, motivations, and perceptions; (b) the contextual factors needed to enable this emergence to occur; (c) and the feedback mechanisms that reinforce or block the emergence of belonging in a person.

Fifth, although we suggested that four components are necessary for belonging to emerge, it is unknown how much of each component is needed, whether specific sequencing amongst the components matters (i.e., one needs to come before the other) and the extent to which that depends upon the person and the context. For example, culture can intensely affect an individual’s competencies for belonging, opportunities to belong, motivations to belong, and even perceptions of belonging ( Cortina et al., 2017 ). As a dynamic, emergent construct, each likely component impacts upon and interacts with the others. Still, for some individuals or across different contexts, there might be specific sequences that are more likely to support a sense of belonging. Aligned with other psychological and sociological studies, the existing belonging literature primarily has used variable-centred approaches. Person-centred research that exists points to belonging as being a nonlinear construct, with the ability for the sense of belonging to grow, stall, disappear, or flourish within an individual over the life course ( George & Selimons, 2019 ). Longitudinal, person-centred approaches might be a useful complement to traditional study designs because they allow the opportunity to track experiences of belonging in diverse populations, identify the combination of the four components described above, and when belonging emerges, with consideration of personal, social, and environmental moderators.

Finally, multilevel research is needed to elucidate social, neural, immunologic, and behavioural processes associated with belonging. This integrative research can help researchers understand how experiences of belonging “get under the skin” affect human behaviour and health. Equally important is the need to understand the biological processes that are affected by experiences of disconnection versus belonging, which can help researchers elucidate the regulatory logic of these systems to understand better what aspects of belonging are most critical or essential for health ( Slavich, 2020 ; Slavich & Irwin, 2014 ). Such knowledge can ultimately help investigators develop more effective interventions for increasing perceptions of belonging and lead to entirely new ways of conceptualising this fundamental construct.

In conclusion, a sense of belonging is a core part of what makes one a human being ( Baumeister & Leary, 1995 ; Deci & Ryan, 2000 ; Slavich, 2020 ; Vaillant, 2012). Just as harbouring a healthy sense of belonging can lead to many positive life outcomes, feeling as though one does not belong is robustly associated with a lack of meaning and purpose, increased risk for experiencing mental and physical health problems, and reduced longevity. As technology continues to develop, the pace of modern life has sped up, traditional social structures have broken down, and cultural and ethnic values have been threatened, increasing the importance of helping people establish and sustain a fundamental sense of belonging. Focusing on competencies, opportunities, motivations, and perceptions can be a useful framework for developing strategies aimed at increasing peoples’ sense of belonging at both the individual and collective level. To fully realize this framework’s potential to aid society, much work is needed.

G.M.S. was supported by a Society in Science—Branco Weiss Fellowship, NARSAD Young Investigator Grant #23958 from the Brain & Behavior Research Foundation, and National Institutes of Health grant K08 MH103443.

Conflicts of Interest : The authors declare no conflicts of interest with regard to this work.

- Abdollahi A, Panahipour S, Tafti MA, & Allen KA (2020). Academic hardiness as a mediator for the relationship between school belonging and academic stress . Psychology in the Schools . 10.1002/pits.22339 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ahmed MZ, Ahmed O, Aibao Z, Hanbin S, Siyu L, & Ahmad A (2020). Epidemic of COVID-19 in China and associated psychological problems . Asian Journal of Psychiatry , 51 , 102092. 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102092 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Akar-Vural R, Yilmaz-Özelçi S, Çengel M, & Gömleksiz M (2013). The development of the “Sense of Belonging to School” scale . Eurasian Journal of Educational Research , 53 , 215–230. [ Google Scholar ]

- Akiva T, Cortina KS, Eccles JS, & Smith C (2013). Youth belonging and cognitive engagement in organized activities: A large-scale field study . Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology , 34 ( 5 ), 208–218. 10.1016/j.appdev.2013.05.001 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Allen KA (2020). Commentary of Lim, M., Eres, R., Gleeson, J., Long, K., Penn, D., & Rodebaugh, T. (2019). A pilot digital intervention targeting loneliness in youth mental health . Frontiers in Psychiatry . 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00959 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Allen KA (2020a). Psychology of belonging . Routledge. [ Google Scholar ]

- Allen KA (2020b). Commentary of Lim, M., Eres, R., Gleeson, J., Long, K., Penn, D., & Rodebaugh, T. (2019). A pilot digital intervention targeting loneliness in youth mental health . Frontiers in Psychiatry . 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00959 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Allen KA, & Bowles T (2012). Belonging as a guiding principle in the education of adolescents . Australian Journal of Educational and Developmental Psychology , 12 , 108–119. [ Google Scholar ]

- Allen KA, & Kern ML (2017). School Bbelonging in adolescents: Theory, research, and practice . Springer Social Sciences. ISBN 978-981-10-5996-4 [ Google Scholar ]

- Allen KA, & Kern P (2019). Boosting school belonging in adolescents: Interventions for teachers and mental health professionals . Routledge. [ Google Scholar ]

- Allen KA, Boyle C, & Roffey S (2019). Creating a culture of belonging in a school context. Educational and Child Psychology, special issue school belonging . Educational and Child Psychology , 36 ( 4 ), 5–7. [ Google Scholar ]

- Allen KA, Kern ML, Vella-Brodrick D, Hattie J, & Waters L (2018). What schools need to know about fostering school belonging: A meta-analysis . Educational Psychology Review , 30 , 1–34. 10.1007/s10648-016-9389-8 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Allen KA, Vella-Brodrick D, & Waters L (2016). Fostering school belonging in secondary schools using a socio-ecological framework . The Educational and Developmental Psychologist , 33 ( 1 ), 97–121. 10.1017/edp.2016.5 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Allen KA, Ryan T, Gray DL, McInerney D, & Waters L (2014). Social media use and social connectedness in adolescents: The positives and the potential pitfalls . The Australian Educational and Developmental Psychologist , 31 ( 1 ), 18–31. 10.1017/edp.2014.2 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Amichai-Hamburger Y, Wainapel G, & Fox S (2002). On the Internet no one knows I’m an introvert: Extroversion, neuroticism, and Internet interaction . Cyberpsychology & Behavior , 5 ( 2 ), 125–128. 10.1089/109493102753770507 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Anderson GO, & Thayer C (2018, September). Loneliness and social connections: A national survey of adults 45 and older . https://www.aarp.org/research/topics/life/info-2018/loneliness-social-connections.html

- Aron A, Melinat E, Aron EN, Vallone RD, & Bator RJ (1997). The experimental generation of interpersonal closeness: A procedure and some preliminary findings . Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin , 23 ( 4 ), 363–377. 10.1177/0146167297234003 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Arslan G, Allen KA, & Ryan T (2020). Exploring the impacts of school belonging on youth wellbeing and mental health: A longitudinal study . Child Indicators Research , 13 , 1619–1635. 10.1007/s12187-020-09721-z [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Arslan G, & Allen KA (2020). School bullying, mental health, and wellbeing in adolescents: Mediating impact of positive psychological orientations . Child Indicators Research . 10.1007/s12187-020-09780-2 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Australian Psychological Society. (2018). Australian loneliness report . https://psychweek.org.au/wp/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/Psychology-Week-2018-Australian-Loneliness-Report-1.pdf

- Baumeister RF, & Leary MR (1995). The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation . Psychological Bulletin , 117 ( 3 ), 497–529. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Baumeister RF & Robson, (2021) [This issue]

- Bhalla A, & Lapeyre F (1997). Social exclusion: Towards an analytical and operational framework . Development and Change , 28 ( 3 ), 413–433. 10.1111/1467-7660.00049 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Blackhart GC, Eckel LA, & Tice DM (2007). Salivary cortisol in response to acute social rejection and acceptance by peers . Biological Psychology , 75 ( 3 ), 267–276. 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2007.03.005 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Blackhart GC, Nelson BC, Winter A, & Rockney A (2011). Self-control in relation to feelings of belonging and acceptance . Self and Identity , 10 ( 2 ), 152–165. 10.1080/15298861003696410 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Borman GD, Rozek CS, Pyne JR, & Hanselman P (2019). Reappraising academic and social adversity improves middle-school students’ academic achievement, behavior, and well-being . Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences , 116 ( 33 ), 16286–16291. 10.1073/pnas.1820317116 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bowles T, & Scull J (2019). The centrality of Cconnectedness: A conceptual synthesis of attending, belonging, engaging and flowing . Journal of Psychologists and Counsellors in Schools , 29 ( 1 ),1–23. 10.1017/jgc.2018.13 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Boyd R, & Richerson PJ (2009). Culture and the evolution of human cooperation . Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences , 364 ( 1533 ), 3281–3288. 10.1098/rstb.2009.0134 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Brady ST, Cohen GL, Shoshana NJ, & Walton GM (2020). A brief social-belonging intervention in college improves adult outcomes for Black Americans . Science Advances , 6 ( 18 ), eaay3689. 10.1126/sciadv.aay3689 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Brewer MB (2007). The importance of being we: Human nature and intergroup relations . American Psychologist , 62 ( 8 ), 728–738. 10.1037/0003-066X.62.8.728 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Butler AC, Chapman JE, Forman EM, & Beck AT (2006). The empirical status of cognitive-behavioral therapy: A review of meta-analyses . Clinical Psychology Review , 26 ( 1 ), 17–31. 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.07.003 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cacioppo JT, & Hawkley LC (2003). Social isolation and health, with an emphasis on underlying mechanisms . Perspectives in Biology and Medicine , 46 ( 3 ), S39–S52. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cacioppo JT, Hawkley LC, Norman GJ, & Berntson GG (2011). Social isolation . Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences , 1231 ( 1 ), 17–22. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2011.06028.x [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cacioppo S, Grippo AJ, London S, Goossens L, & Cacioppo JT (2015). Loneliness: clinical import and interventions . Perspectives in Psychological Science , 10 ( 2 ), 238–249. 10.1177/1745691615570616 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Carter J, Hollinsworth D, Raciti M, & Gilbey K (2018). Academic ‘place-making’: fostering attachment, belonging and identity for Indigenous students in Australian universities . Teaching in Higher Education , 23 ( 2 ), 243–260. 10.1080/13562517.2017.1379485 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Choenarom C, Williams RA, & Hagerty BM (2005). The role of sense of belonging and social support on stress and depression in individuals with depression . Archives of Psychiatric Nursing , 19 ( 1 ), 18–29. 10.1016/j.apnu.2004.11.003 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Choi BC, & Pak AW (2006). Multidisciplinarity, interdisciplinarity and transdisciplinarity in health research, services, education and policy: Definitions, objectives, and evidence of effectiveness . Clinical Investigative Medicine , 29 ( 6 ), 351–364 [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cigna. (2018). Cigna U.S. loneliness index: Survey of 20,000 Americans behaviors driving loneliness in the United States. Cigna/Ipsos National Report https://www.cigna.com/static/www-cigna-com/docs/about-us/newsroom/studies-and-reports/combatting-loneliness/loneliness-survey-2018-full-report.pdf

- Claridge T (2018). Functions of social capital—Bonding, bridging, linking . Social Capital Research , 1–7. [ Google Scholar ]

- Clark LA, Vittengl J, Kraft D, & Jarrett RB (2003). Separate personality traits from states to predict depression . Journal of Personality Disorders , 17 ( 2 ), 152–172. 10.1521/pedi.17.2.152.23990 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Coie JD (2004). The impact of negative social experiences on the development of antisocial behavior. In Kupersmidt JB & Dodge KA (Eds.), Decade of behavior. Children’s peer relations: From development to intervention (pp. 243–267). American Psychological Association. 10.1037/10653-013 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (CASEL). (2018). The collaborative for academic, social, and emotional learning . https://casel.org/

- Colquhoun S, & Dockery AM (2012). The link between Indigenous culture and wellbeing: Qualitative evidence for Australian Aboriginal peoples . The Centre for Labour Market Research; (ISSN 1329–2676). http://www.ncsehe.edu.au/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/2012.01_LSIC_qualitative_CLMR1.pdf [ Google Scholar ]

- Corbould C (2020, June). The fury in US cities is rooted in a long history of racist policing, violence and inequality . The Conversation . https://theconversation.com/the-fury-in-us-cities-is-rooted-in-a-long-history-of-racist-policing-violence-and-inequality-139752 [ Google Scholar ]

- Cornwell EY, & Waite LJ (2009). Social disconnectedness, perceived isolation, and health among older adults . Journal of Health and Social Behavior , 50 ( 1 ), 31–48. 10.1177/002214650905000103 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Correa-Velez I, Gifford SM, & Barnett AG (2010). Longing to belong: Social inclusion and well-being among youth with refugee backgrounds in the first three years in Melbourne, Australia . Social Science & Medicine , 71 ( 8 ), 1399–1408. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.07.018 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cortina KS, Arel S, & Smith-Darden JP (2017, November). School belonging in different cultures: The effects of individualism and power distance . Frontiers in Education , 2 , 56. [ Google Scholar ]

- Cruwys T, Haslam SA, Dingle GA, Haslam C, & Jetten J (2014). Depression and social identity: An integrative review . Personality and Social Psychology Review , 18 ( 3 ), 215–238. 10.1177/1088868314523839 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Davis K (2012). Friendship 2.0: Adolescents’ experiences of belonging and self-disclosure online . Journal of Adolescence , 35 ( 6 ), 1527–1536. 10.1016/j.adolescence.2012.02.013 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Deci EL, & Ryan RM (2000). The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior . Psychological Inquiry , 11 ( 4 ), 227–268. 10.1207/S15327965PLI1104_01 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Dockery AM (2010). Culture and wellbeing: The case of Indigenous Australians . Social indicators research , 99 ( 2 ), 315–332. 10.1007/s11205-010-9582-y [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Dsouza DD, Quadros S, Hyderabadwala ZJ, & Mamun MA (2020). Aggregated COVID-19 suicide incidences in India: Fear of COVID-19 infection is the prominent causative factor . Psychiatry Research , 290 , e113145. 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113145 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Durlak JA, Weissberg RP, Dymnicki AB, Taylor RD, & Schellinger K (2011). The impact of enhancing students’ social and emotional learning: A meta-analysis of school-based universal interventions . Child Development , 82 ( 1 ), 405–432. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01564.x [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Erzen E, & Çikrikci Ö (2018). The effect of loneliness on depression: A meta-analysis. International . Journal of Social Psychiatry , 64 ( 5 ), 427–435. 10.1177/0020764018776349 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Filstad C, Traavik LE, & Gorli M (2019). Belonging at work: The experiences, representations and meanings of belonging . Journal of Workplace Learning , 31 ( 2 ), 116–142. https://doi-org.ezproxy.lib.monash.edu.au/10.1108/JWL-06-2018-0081 [ Google Scholar ]

- Flowerday T, & Shaughnessy M (2005). An interview with Dennis McInerney . Educational Psychology Review , 17 , 83–97. 10.1007/s10648-005-1637-2. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Freeman TM, Anderman LH, & Jensen JM (2007). Sense of belonging in college freshmen at the classroom and campus levels . The Journal of Experimental Education , 75 ( 3 ), 203–220. 10.3200/JEXE.75.3.203-220 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Frostad P, & Pijl SJ (2007). Does being friendly help in making friends? The relation between the social position and social skills of pupils with special needs in mainstream education . European Journal of Special Needs Education , 22 ( 1 ), 15–30. 10.1080/08856250601082224 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Frydenberg E, Care E, Freeman E, & Chan E (2009). Interrelationships between coping, school connectedness and well-being . Australian Journal of Education , 53 ( 3 ), 261–276. [ Google Scholar ]

- Frydenberg F, Lewis R, Bugalski K, Cotta A, McCarthy C, Luscombe‐Smith N, & Poole C (2004). Prevention is better than cure: Coping skills training for adolescents at school . Educational Psychology in Practice , 20 ( 2 ), 117–134. 10.1080/02667360410001691053 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gardner A, Filia K, Killacky E, & Cotton S (2019). The social inclusion of young people with serious mental illness: A narrative review of the literature and suggested future directions . Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry , 53 ( 1 ), 15–26. 10.1177/0004867418804065 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- George G, & Selimos ED (2019). Searching for belonging and confronting exclusion: a person-centred approach to immigrant settlement experiences in Canada . Social Identities , 25 ( 2 ), 125–140. 10.1080/13504630.2017.1381834 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gerber J, & Wheeler L (2009). On being rejected: A meta-analysis of experimental research on rejection . Perspectives on Psychological Science , 4 ( 5 ), 468–488. 10.1111/j.1745-6924.2009.01158.x [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Goodenow C (1993). The psychological sense of school membership among adolescents: Scale development and educational correlates . Psychology in the Schools , 30 ( 1 ), 79–90. 10.1002/1520-6807(199301)30:1<79::AID-PITS2310300113>3.0.CO;2-X [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Goodenow C, & Grady KE (1993). The relationship of school belonging and friends’ values to academic motivation among urban adolescent students . Journal of Experimental Education , 62 ( 1 ), 60–71. [ Google Scholar ]

- Gruber J, Prinstein MJ, Clark LA, Rottenberg J, Abramowitz JS, Albano AM, Aldao A, Borelli JL, Chung T, Davila J, Forbes EE, Gee DG, Hall GCN, Hallion LS, Hinshaw SP, Hofmann SG, Hollon SD, Joormann J, Kazdin AE, … Weinstock LM (in press). Mental health and clinical psychological science in the time of COVID-19: Challenges, opportunities, and a call to action . American Psychologist . 10.1037/amp0000707 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gustafson P (2009). Mobility and territorial belonging . Environment and Behavior , 41 ( 4 ), 490–508. 10.1177/0013916508314478 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hagerty BM, Lynch-Sauer JL, Patusky K, Bouwsema M, & Collier P (1992). Sense of belonging: A vital mental health concept . Archives of Psychiatric Nursing , 6 ( 3 ), 172–177. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hagerty BM, & Patusky K (1995). Developing a measure of sense of belonging . Nursing Research , 44 ( 1 ), 9–13. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hagerty BM, Williams RA, & Oe H (2002). Childhood antecedents of adult sense of belonging . Journal of Clinical Psychology , 58 ( 7 ), 793–801. 10.1002/jclp.2007 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hanh TN (2017). The art of living . Ebury. [ Google Scholar ]

- Hari J (2019). Lost connections: Uncovering the real causes of depression—and the unexpected solutions . Permanente Journal , 23 , 18–231. 10.7812/TPP/18-231 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Harrison N, & McLean R (2017). Getting yourself out of the way: Aboriginal people listening and belonging in the city . Geographical Research , 55 ( 4 ), 359–368. 10.1111/1745-5871.12238 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Harrist AW, & Bradley KD (2002). Social exclusion in the classroom: Teachers and students as agents of change. In Aronson J (Ed.), Improving academic achievement (pp. 363–383). Academic Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Hausman LRM, Schofield JW, & Woods RL (2007). Sense of belonging as a predictor of intentions to persist among African American and White first-year college students . Research in Higher Education , 48 ( 7 ), 803–839. https://www.jstor.org/stable/25704530 [ Google Scholar ]

- Hawkley LC, & Capitanio JP (2015). Perceived social isolation, evolutionary fitness and health outcomes: a lifespan approach . Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences , 370 ( 1669 ), 20140114. 10.1098/rstb.2014.0114 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Herbert J, McInerney DM, Fasoli L, Stephenson P, & Ford L (2014). Indigenous secondary education in the Northern Territory: Building for the future . The Australian Journal of Indigenous Education , 43 , 85–95. 10.1017/jie2014.17 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Holt-Lunstad J (2018). Why social relationships are important for physical health: A systems approach to understanding and modifying risk and protection . Annual Review of Psychology , 69 , 437–458. 10.1146/annurev-psych-122216-011902 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Holt-Lunstad J, Smith TB, Baker M, Harris T, & Stephenson D (2015). Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for mortality: A meta-analytic review . Perspectives on Psychological Science , 10 ( 2 ), 227–237. 10.1177/1745691614568352 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hunter E (1998). Adolescent attraction to cults . Adolescence , 33 ( 131 ), 709–714. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Jaitli R, & Hua Y (2013). Measuring sense of belonging among employees working at a corporate campus: Implication for workplace planning and management . Journal of Corporate Real Estate , 15 ( 2 ), 117–135. 10.1108/JCRE-04-2012-0005 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kanter JW, Kuczynski AM, Tsai M, & Kohlenberg RJ (2018). A brief contextual behavioral intervention to improve relationships: A randomized trial . Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science , 10 , 75–84. 10.1016/j.jcbs.2018.09.001 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Karaman Ö, & Tarim B (2018). Investigation of the correlation between belonging needs of students attending university and well-being . Universal Journal of Educational Research , 6 ( 4 ), 781–788. 10.13189/ujer.2018.060422 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kern ML, Williams P, Spong C, Colla R, Sharma K, Downie A, Taylor JA, Sharp S, Siokou C, & Oades LG (2020). Systems informed positive psychology . Journal of Positive Psychology , 15 , 705–715. 10.1080/17439760.2019.1639799 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Keyes EF, & Kane CF (2004). Belonging and adapting: Mental health of Bosnian refugees living in the United States . Issues in Mental Health Nursing , 25 ( 8 ), 809–831. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kitchen P, Williams AM, & Gallina M (2015). Sense of belonging to local community in small-to-medium sized Canadian urban areas: A comparison of immigrant and Canadian-born residents . B.M.C. Psychology , 3 ( 1 ), 28. 10.1186/s40359-015-0085-0 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kross E, Egner T, Ochsner K, Hirsch J, & Downey G (2007). Neural dynamics of rejection sensitivity . Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience , 19 ( 6 ), 945–956. 10.1162/jocn.2007.19.6.945 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lambert NM, Stillman TF, Hicks JA, Kamble S, Baumeister RF, & Fincham FD (2013). To belong is to matter: Sense of belonging enhances meaning in life . Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin , 39 ( 11 ), 1418–1427. 10.1177/0146167213499186 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Leary MR (1990). Responses to social exclusion: Social anxiety, jealousy, loneliness, depression, and low self-esteem . Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology , 9 ( 2 ), 221–229. 10.1521/jscp.1990.9.2.221 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Leary MR, & Allen AB (2011). Belonging motivation: Establishing, maintaining, and repairing relational value. In Dunning D (Ed.), Frontiers of social psychology. Social motivation (pp. 37–55). Psychology Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Leary MR, & Kelly KM (2009). Belonging motivation. In Leary MR & Hoyle RH (Eds.), Handbook of individual differences in social behavior (pp. 400–409). Guilford. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2009-12071-027 [ Google Scholar ]

- Leary MR, Kelly KM, Cottrell CA, & Schreindorfer LS (2013). Construct validity of the need to belong scale: Mapping the nomological network . Journal of Personality Assessment , 95 ( 6 ), 610–624. 10.1080/00223891.2013.819511 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Leary MR, Kowalski RM, Smith L, & Phillips S (2003). Teasing, rejection, and violence: Case studies of the school shootings . Aggressive Behavior , 29 ( 3 ), 202–214. 10.1002/ab.10061 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Leary MR, Twenge JM, & Quinlivan E (2006). Interpersonal rejection as a determinant of anger and aggression . Personality and Social Psychology Review , 10 ( 2 ), 111–132. 10.1207/s15327957pspr1002_2 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lim M Allen KA, Craig H, Smith D & Furlong MJ (2021, in this issue). Feeling lonely and a need to belong: What is shared and distinct? Australian Journal of Psychology . [ Google Scholar ]

- London B, Downey G, Bonica C, & Paltin I (2007). Social causes and consequences of rejection sensitivity . Journal of Research on Adolescence , 17 ( 3 ), 481–506. 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2007.00531.x [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Long LL (2016). How undergraduate’s involvement affects sense of belonging in courses that use technology . Proceedings from 2016 American Society of Engineering Education (ASEE) Annual Conference and Exposition. New Orleans, LA. 10.18260/p.25491 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Luchetti M, Lee JH, Aschwanden D, Sesker A, Strickhouser JE, Terracciano A, & Sutin AR (2020). The trajectory of loneliness in response to COVID-19 . American Psychologist . 10.1037/amp0000690 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lyons-Padilla S, Gelfand MJ, Mirahmadi H, Farooq M, & van Egmond M (2015). Belonging nowhere: Marginalization & radicalization risk among Muslim immigrants . Behavioral Science & Policy , 1 ( 2 ), 1–12. 10.1353/bsp.2015.0019 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ma X (2003). Sense of belonging to school: Can schools make a difference? The Journal of Educational Research , 96 ( 6 ), 340–349. 10.1080/00220670309596617 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Mahar AL, Cobigo V, & Stuart H (2014). Comments on measuring belonging as a service outcome . Journal on Developmental Disabilities , 20 ( 2 ), 20–33. [ Google Scholar ]

- Malone GP, Pillow DR, & Osman A (2012). The general belongingness scale (G.B.S.): Assessing achieved belongingness . Personality and Individual Differences , 52 ( 3 ), 311–316. 10.1016/j.paid.2011.10.027 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Martin A (2007). The Motivation and Engagement Scale (M.E.S.) Lifelong Achievement Group. [ Google Scholar ]

- Maslow AH (1954). Motivation and personality . Harper and Row. [ Google Scholar ]

- May V (2011). Self, belonging and social change . Sociology , 45 ( 3 ), 363–378. 10.1177/0038038511399624 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- McInerney DM (1989). Urban Aboriginals parents’ views on education: A comparative analysis . Journal of Intercultural Studies , 10 , 43–65. 10.1080/07256868.1989.9963353 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Mello ZR, Mallett RK, Andretta JR, & Worrell FC (2012). Stereotype threat and school belonging in adolescents from diverse racial/ethnic backgrounds . Journal of At-Risk Issues , 17 ( 1 ), 9–14. [ Google Scholar ]

- Mellor D, Stokes M, Firth L, Hayashi Y, & Cummins R (2008). Need for belonging, relationship satisfaction, loneliness, and life satisfaction . Personality and Individual Differences , 45 ( 3 ), 213–218. 10.1016/j.paid.2008.03.020 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Moallem I (2013). A meta-analysis of school belonging and academic success and persistence [Doctoral Dissertation, Loyola University Chicago; ]. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss/726 [ Google Scholar ]

- Moore K, & McElroy JC (2012). The influence of personality on Facebook usage, wall postings, and regret . Computers in Human Behavior , 28 ( 1 ), 267–274. 10.1016/j.chb.2011.09.009 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Morieson L, Carlin D, Clarke B, Lukas K, & Wilson R (2013). Belonging in education: Lessons from the Belonging Project . The International Journal of the First Year in Higher Education , 4 , 87–96. 10.5204/intjfyhe.v4i2.173 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Murray B, Domina T, Petts A, Renzulli L, & Boylan R (2020). “We’re in This Together”: Bridging and Bonding Social Capital in Elementary School PTOs . American Educational Research Journal , 57 ( 5 ), 2210–2244. 10.3102/0002831220908848 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Nelson CA III, Zeanah CH, & Fox NA (2019). How early experience shapes human development: The case of psychosocial deprivation . Neural Plasticity , 2019 , 1676285. 10.1155/2019/1676285 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Nichols AL, & Webster GD (2013). The single-item need to belong scale . Personality and Individual Differences , 55 ( 2 ), 189–192. 10.1016/j.paid.2013.02.018 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- O’Brien KA, & Bowles TV (2013). The importance of belonging for adolescents in aecondary achool aettings . The European Journal of Social & Behavioural Sciences , 5 ( 2 ), 976–984. [ Google Scholar ]

- O’Leary C (2020). An examination of Indigenous Australians who are flourishing [Master’s thesis, The University of Melbourne; ]. [ Google Scholar ]

- Pyne J, Rozek CS, & Borman GD (2018). Assessing malleable social-psychological academic attitudes in early adolescence . Journal of School Psychology , 71 , 57–71. 10.1016/j.jsp.2018.10.004 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Putnam R (2000). Bowling alone: The collapse and revival of American community . Simon & Schuster. [ Google Scholar ]

- Rainey K, Dancy M, Mickelson R, Stearns E, & Moller S, (2018). Race and gender differences in how sense of belonging influences decisions to major in STEM . International Journal of STEM Education , 5 ( 1 ), 1–10. 10.1186/s40594-018-0115-6 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ramsden P (2020, June). How the pandemic changed social media and George Floyd’s death created a collective conscience . The Conversation . https://theconversation.com/how-the-pandemic-changed-social-media-and-george-floyds-death-created-a-collective-conscience-140104 [ Google Scholar ]

- Rico-Uribe LA, Caballero FF, Martín-María N, Cabello M, Ayuso-Mateos JL, & Miret M (2018). Association of loneliness with all-cause mortality: A meta-analysis . PloS one , 13 ( 1 ), e0190033. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Riley K (2017). Place, belonging and school leadership: Researching to make the difference . Bloomsbury. [ Google Scholar ]

- Roffey S (2013). Inclusive and exclusive belonging -the impact on individual and community well-being . Educational and Child Psychology , 30 , 38–49. [ Google Scholar ]

- Roffey S, Boyle C, & Allen KA (2019). School belonging — Why are our students longing to belong to school? Educational and Child Psychology , 36 ( 2 ), 6–8. [ Google Scholar ]

- Rouchy JC (2002). Cultural identity and groups of belonging . Group , 26 ( 3 ), 205–217. [ Google Scholar ]

- Ryan RM, & Deci EL (2001). On happiness and human potentials: A review of research on hedonic and eudaimonic well-being . Annual Review of Psychology , 52 , 141–166. 10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.141 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ryan T, Allen KA, Gray DL, & McInerney DM (2017). How social are social media? A review of online social behaviour and connectedness . Journal of Relationship Research , 8 ( e8 ), 1–8. 10.1017/jrr.2017.13 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Schall J, LeBaron Wallace T, & Chhuon V (2016). ‘Fitting in’ in high school: how adolescent belonging is influenced by locus of control beliefs , International Journal of Adolescence and Youth , 21 ( 4 ), 462–475. 10.1080/02673843.2013.866148 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Schein RH (2009). Belonging through land/scape . Environment and Planning A , 41 ( 4 ), 811–826. 10.1068/a41125 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Seabrook EM, Kern ML, & Rickard R (2016). Social networking sites, depression, and anxiety: A systematic review . JMIR Mental Health , 3 ( 4 ): e50. 10.2196/mental.5842 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Sedgwick MG, & Rougeau J (2010). Points of tension: A qualitative descriptive study of significant events that influence undergraduate nursing students’ sense of belonging . Rural and Remote Health , 10 ( 4 ), 1–12. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Seidman G (2013). Self-presentation and belonging on Facebook: How personality influences social media use and motivations . Personality and Individual Differences , 54 ( 3 ), 402–407. 10.1016/j.paid.2012.10.009 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Shields GS, Spahr CM, & Slavich GM (2020). Psychosocial interventions and immune system function: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials . JAMA Psychiatry , 77 , 1031–1043. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.0431 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Slaten CD, Ferguson JK, Allen KA, Vella-Brodrick D, & Waters L (2016). School belonging: A review of the history, current trends, and future directions . The Educational and Developmental Psychologist , 33 ( 1 ), 1–15. 10.1017/edp.2016.6 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Slavich GM (2020). Social safety theory: A biologically based evolutionary perspective on life stress, health, and behavior . Annual Review of Clinical Psychology , 16 , 265–295. 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032816-045159 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Slavich GM, & Cole SW (2013). The emerging field of human social genomics . Clinical Psychological Science , 1 , 331–348. 10.1177/2167702613478594 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]