Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Data Descriptor

- Open access

- Published: 20 January 2022

Psychophysiology of positive and negative emotions, dataset of 1157 cases and 8 biosignals

- Maciej Behnke ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2455-4556 1 , 2 ,

- Mikołaj Buchwald 3 ,

- Adam Bykowski 3 ,

- Szymon Kupiński ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-4704-6802 3 &

- Lukasz D. Kaczmarek 1

Scientific Data volume 9 , Article number: 10 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

15k Accesses

13 Citations

37 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Cardiovascular biology

Subjective experience and physiological activity are fundamental components of emotion. There is an increasing interest in the link between experiential and physiological processes across different disciplines, e.g., psychology, economics, or computer science. However, the findings largely rely on sample sizes that have been modest at best (limiting the statistical power) and capture only some concurrent biosignals. We present a novel publicly available dataset of psychophysiological responses to positive and negative emotions that offers some improvement over other databases. This database involves recordings of 1157 cases from healthy individuals (895 individuals participated in a single session and 122 individuals in several sessions), collected across seven studies, a continuous record of self-reported affect along with several biosignals (electrocardiogram, impedance cardiogram, electrodermal activity, hemodynamic measures, e.g., blood pressure, respiration trace, and skin temperature). We experimentally elicited a wide range of positive and negative emotions, including amusement, anger, disgust, excitement, fear, gratitude, sadness, tenderness, and threat. Psychophysiology of positive and negative emotions (POPANE) database is a large and comprehensive psychophysiological dataset on elicited emotions.

Machine-accessible metadata file describing the reported data: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.17061512

Similar content being viewed by others

Microdosing with psilocybin mushrooms: a double-blind placebo-controlled study

Dimensionality reduction beyond neural subspaces with slice tensor component analysis

Emotions and brain function are altered up to one month after a single high dose of psilocybin

Background & summary.

The emotional response involves changes in subjective experience and physiology that mobilize individuals towards a behavioral response 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 . Theorists have debated for decades on the psychophysiology of human emotions focusing on several questions 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 . For instance, whether specific emotions produce a specific physiological response 3 , how different biosignals are correlated within an emotional response 5 , 6 , whether the physiological response allows predicting concurrent subjective experience 11 , what new features within a specific biosignal (e.g., the ECG wave) are influenced by emotions 12 , what improved methods of data processing can be used 13 , how emotions influence physiological patterns related to health 14 , 15 .

Physiological responses to the emotional stimuli were primarily of interest in psychology. However, emotions have recently also gained attention in other scientific fields, such as neuroscience 16 , product and experience design 17 , and computer science 18 . For instance, Affective Computing (an interdisciplinary field also known as Emotional AI) uses psychophysiological signals for developing algorithms that allow detecting, processing, and adapting to others’ emotions 19 , 20 . To allow machines to learn about specific emotion features, researchers have to provide these machines with multiple descriptors of emotional response, including subjective experience of affect (e.g., valence and motivational tendency) and objective physiological measures (e.g., cardiovascular, electrodermal, and respiratory measures).

These basic science and applied problems require robust empirical material that provides a large and comprehensive dataset that offers abundant emotions, diverse physiological signals, and the number of participants providing high statistical power. Moreover, researchers use various methods to elicit emotions 21 , including film clips 22 , 23 , pictures 24 , video recording/social pressure 25 , 26 , and behavioral manipulations 27 . Thus, accounting for various methods of emotion elicitation might contribute to database versatility.

A considerable amount of work has been done during the last two decades for creating multimodal datasets with psychophysiological responses to affective stimuli, including DEAP 28 , RECOLA 29 , CASE 30 , or K-EmoCon 31 . The strengths of our database – Psychophysiology of Positive and Negative Emotions (POPANE) 32 are:

a wide range of positive and negative emotions, including amusement, anger, disgust, excitement, fear, gratitude, sadness, tenderness, and threat;

multiple methods to elicit emotions, namely: films, pictures, and affective social interactions (anticipated social exposition or expressing gratitude)

continuous emotional responses via self-reports and autonomic nervous system (ANS) activity using electrocardiography, impedance cardiography, electrodermal activity sensors, photoplethysmography (the hemodynamic measures), respiratory sensors, and a thermometer;

the length of our data is up to 725 hours of recordings, depending on the signal type. Table 1 presents the signal length for specific measures, stimuli, and emotion categories.

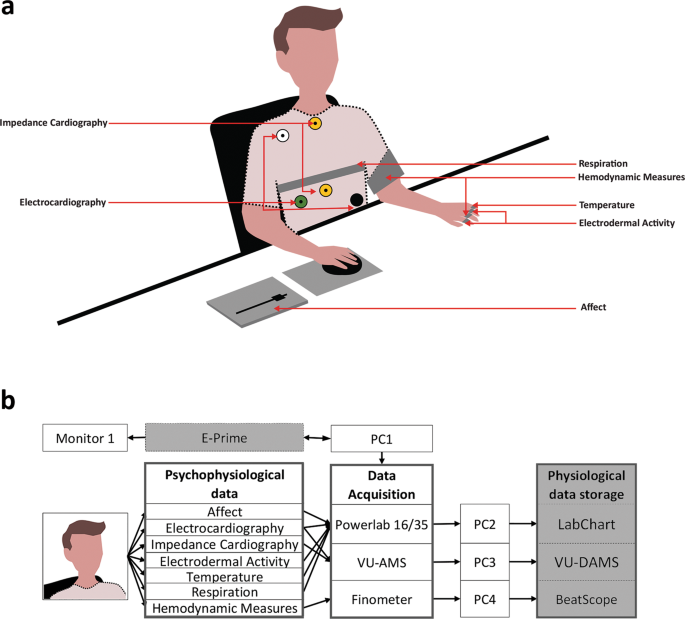

POPANE contains psychophysiological data from seven large-scale experiments that investigated the functions of positive and negative emotions. The studies tested how emotions influence the speed of cardiovascular recovery (Study 1 & 2) 33 , motivation to engage in a positive psychological intervention (Study 3) 34 , economic decisions (Study 4) 35 , responses to others successes (Study 5) 36 , responses to an unfair offer (Study 6) 37 , and gaming efficacy (Study 7) 38 , 39 . Tables 1 and 2 summarize the POPANE dataset. Figure 1 presents a schematic overview of the experimental setup used to collect the data.

A schematic visualization of the data acquisition procedure. Panel a presents the approximate placement of the sensors. Panel b presents hardware (in white) and software (in grey) used for data acquisition. This figure was created by Katarzyna Janicka. The copyright of the figure is held by Katarzyna Janicka.

We present data collected in the Psychophysiological Laboratory, at the Faculty of Psychology and Cognitive Science, Adam Mickiewicz University, from November 2016 to July 2019 in Poznan, Poland. All methods are described in detail in the following works: Study 1 & 2 33 , Study 3 34 , Study 4 35 , Study 5 36 , Study 6 37 , Study 7 38 .

Participants

The database includes 1157 cases (45% female) between the ages of 18 and 38 ( M = 22.01, SD = 2.80). Table 2 presents participants’ characteristics for each study. We recruited participants via advertisements on Facebook and internal University communication channels. We asked participants to reschedule if they felt sick or experienced a serious negative life event and to abstain from vigorous exercise, food, and caffeine for two hours before testing. In recruitment, we invited participants that: 1) were healthy – had no significant health problems, 2) did not use drugs nor medications that might affect cardiovascular functions, 3) had no prior diagnosis of cardiovascular disease or hypertension. We introduced the above exclusion criteria to limit factors that might influence cardiovascular functions. We measured the participants’ height using an anthropometer and weight using an Omron BF511 scale (Omron Europe B.V., Netherlands). Each participant provided written informed consent and received vouchers for a cinema ticket for participation in the study. Of the participants, 895 participated in a single study, 101 in two studies, 19 in three studies, and two in four studies. The participants’ numerical IDs are presented in a metadata file. Next to specific within-study ID, we present the participants’ IDs from other studies so that within-person analyses might be possible to perform.

Ethics statement

All studies were approved by and performed in accordance with guidelines and regulations of the Institutional Ethics Committee at the Faculty of Psychology and Cognitive Science, Adam Mickiewicz University.

Procedures common across the studies

In most of our studies, participants were tested individually in a sound-attenuated and air-conditioned room. Study 5 involved opposite-sex couples tested together in the same room but in separate cubicles, with no interaction with each other. Participants were randomly assigned to the experimental conditions. We also randomized the order of affective stimuli within the studies. Detailed information on the order of affective stimuli in each study is available in the metadata file. All instructions were presented, and responses were collected via a PC with a 23-inch screen. The experiments were run in the e-Prime 2.0 (Study 1, 2, 3, 4) and 3.0 (Study 5, 6, 7) Professional Edition environment (Psychology Software Tools).

Upon arrival in the lab, participants provided informed consent, and the researcher applied sensors to obtain psychophysiological measurements. Studies began with a five-minute resting baseline (only Study 3 began with a three-minute baseline). During baseline, participants were asked to sit and remain still. Upon completing all studies, biosensors were removed, and the participants were debriefed.

After the baseline, participants completed the speech preparation task, which aimed at threat elicitation. Later, depending on randomization, affective pictures were presented on the PC screen to elicit high-approach motivation positive affect, low-approach motivation positive affect, or the neutral state for three minutes.

After the baseline, participants watched affective pictures (high-approach positive affect, low-approach positive affect, or neutral depending on randomization) for three minutes. Afterward, they were asked to prepare the speech which aimed at threat or anger elicitation (depending on randomization).

After completing the baseline, participants were requested to send two text messages: one expressing gratitude and one neutral. The order in which the messages were sent was counterbalanced. Before sending each SMS, participants were instructed to relax for three minutes and report their appraisals. Next, for another three minutes, participants were asked to think about a person to whom they were grateful for something. Afterward, participants were asked to send the message and wait for three minutes as the time needed for physiological recovery.

Participants were told that they would be participating in two unrelated studies. The purpose of the first study was presented as determining the relationship between language orientation and the psychophysiological reactions to film clips. The purpose of the second study was presented as evaluating consumer products. After baseline, participants solved linguistic tasks. Next, they watched fear or neutral state eliciting film clips (depending on randomization). After the emotion manipulation, participants reported social needs and evaluated six pairs of commercial products.

After completing the baseline, each participant was told to wait for their partner who would solve complex tasks. In fact, there were no tasks to be actually solved by any of the participants. Next, each participant completed three rounds consisting of 1) two minutes of watching the film clips while waiting for the partner; 2) receiving bogus information about the partners’ success; and 3) sending the feedback. Participants watched one of the three film sets, including only positive emotions, negative emotions, or a neutral condition (depending on randomization). The film clips were presented in a counterbalanced order.

After the baseline, participants watched one of four 12-minute films’ presentations eliciting only positive emotions, only negative emotions, the mix of positive and negative emotions, and neutral states (depending on randomization). After watching the set of films, participants were instructed to play an ultimatum social game 40 . Participants received the offer, which was considered unfair by most people taking part in this type of research (“6 USD for me and 0.80 USD for you”). Next, participants were asked to decide to accept or reject the offer. Before receiving the offer and after deciding to accept or reject the offer, there was a 2-minute waiting period for recording physiological processes.

After the baseline, participants completed five rounds consisting of (1) a 2-minute resting period; (2) 2-minute emotion elicitation (watching a film clip); (3) self-reports; and (4) playing a FIFA 19 match.

Affective stimuli

Study 1 and 2 used validated pictures 33 from the Nencki Affective Pictures System 24 . We chose three sets of pictures to elicit: high-approach positive affect (Faces340; Landscapes008, L023, L100, L110, L117, L,140, L149, Objects078, O081, O096, O183, O254, O291, O323, People108, P173, P189), low-approach positive affect (Animals099, A153, Faces076, F113, F179, F228, F232, F234, F238, F330, F332, F337, F344, F347, F353, F358, Objects192, O260), and neutral experience (Faces157, F166, F167, F309, F312, Landscapes012, L016, L024, L056, L061, L067, L076, L079, Objects112, O204, O210, O310, O314). Study 1 & 2 used the same set of pictures.

Speech preparation

In Study 1, we elicited threat with a well-validated social threat protocol 25 , 26 , 41 . Participants were asked to prepare a 2-minute speech on the topic “Why are you a good friend?”. We informed participants that the speech would be recorded. Furthermore, participants received the information that they would be randomly selected to deliver the speech or not after the 30 s of speech preparation. However, after 30 s of preparations (anticipatory stress), each participant was informed that they were selected not to deliver the speech.

In Study 2, we randomly assigned participants to prepare a threat or anger-related speech. We used a similar method to elicit a threat as in Study 1, but participants were given 3 min to prepare the speech. Study 2 also intended to elicit anger with a similar method, i.e., anger recall task 42 , 43 , 44 . Participants were asked to prepare a speech on the topic “What makes you angry?”. Participants had 3 minutes to prepare the speech. After 3 minutes of both threat- and anger-related speeches, we informed participants that they were selected not to deliver the speech.

Interpersonal communication

In Study 3, participants expressed their gratitude (a positive relational emotion) towards their benefactors via texting. This intervention was developed within the field of positive psychology 45 . Participants express their gratitude towards their acquaintance by sending a text message during the laboratory session (Gratitude Texting). This intervention involved the essential elements of gratitude expression, including identification and appreciation of a good event, recognition of the benefactors’ role in generating the positive outcome, and the act of communicating gratitude itself 46 . In the control condition, we asked participants to send a neutral text message to their acquaintance with no suggestion regarding the topic. The control condition accounts for psychophysiological responses associated with texting in general 47 . Participants prepared their messages for three minutes.

We used validated and reliable film clips selected from emotion-eliciting video clip databases 22 , 23 , 48 , 49 , 50 . Each clip lasted two minutes (except for films in Study 4 that, in sum, lasted for 3 minutes 41 seconds). Most of the film clips were short excerpts from commercially available films. Within the sessions, clips were presented in a counterbalanced order. Table 1 , along with the metadata spreadsheet, presents which films were used to elicit emotions in the studies. The names of the film descriptions used for emotion elicitation are also available in the metadata file (the “ stimuli ” spreadsheet).

We elicited positive emotions with the following film clips: 1) A Fish Called Wanda (Surprisingly, the homeowners get inside and discover Archie dancing while naked); 2) The Visitors (Visitors damage the letter carrier’s car); 3) When Harry Met Sally (Sally pretends to have an orgasm in a restaurant); 4) The Dead Poets Society (Students climb on their desks to show their solidarity with their professor); 5) Life Is Beautiful (In a second world war prisoner’s camp, a father and a boy talk to the mother through a loudspeaker); 6) Benny & Joone (Benny plays dumb in the café); and 7) Summer Olympic Games (Athletes performing successfully and showing their joyful reactions). We used films 1–3 in Study 5, films 1–6 in Study 6, and films 1 & 7 in Study 7.

We elicited negative emotions with the following film clips: (1) The Blair Witch Project (the characters die in an abandoned house); (2) A Tale of Two Sister s (the clip begins with suspense and ends with an intense explosion) (3) American History X (A neo-nazi kills Blackman’s by smashing his head on the curb); (4) Man Bites Dog ( A hitman pulls out a gun, yelling at an elderly woman); (5) In the Name of the Fathe r (Interrogation scene); (6) Seven (the police find a decomposing corpse); (7) Dangerous Minds (The teacher informs the class about the death of their classmate); and (8) The Champ (the boy cries after his father dies). We used films 1 & 2 in Study 4, films 1 & 3–7 in Study 6, films 3–5 in Study 5, and films 3 & 8 in Study 7.

For neutral conditions, we used the following film clips: (1) Blue 1 (A man organizes the drawers in his desk, or a woman walks down an alley); (2) The Lover (The character walks around town); (3) Blue 3 (The character passes a piece of aluminum foil through a car window); (4) The Last Emperor 1 (Conversation between the Emperor and his teacher); (5) Blue 2 (A woman rides up on an escalator, carrying a box); (6) The Last Emperor 2 (City life scenes); (7) Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me (the character sweeps the floor in the bar). We used films 2 & 5 in Study 4, films 1, 3 & 4 in Study 5, films 1 & 3–7 in Study 6, and film 5 in Study 7.

Sensors & instruments

We present sensors and instruments used in our studies with examples illustrating their possible research applications.

Participants reported the affective experience to the emotional stimuli continuously with an electronic rating scale 51 . We investigated two dimensions of affect: valence (Study 3, 5, & 6) and approach/avoidance motivational tendency (Study 1,2, & 7). Valence is the degree of feeling pleasure or displeasure in response to a stimulus (e.g., object, event, or a person). Individuals experience positive valence while facing favorable objects or situations (e.g., smiling people or amusing events), and negative valence while facing unfavorable objects or situations (e.g., sad individuals) 24 . The approach/avoidance motivational tendency is the urge to move toward or away from an object 52 . Individuals experience high-approach motivation while facing desirable or appetitive objects or situations (e.g., delicious food or sexually attractive individuals), and high-avoidance motivation while facing undesirable or aversive objects or situations (e.g., accidents or infected individuals). We focused on valence because it is the most fundamental and well-studied dimension of the affect, and we focused on the approach/avoidance motivational tendency that is a rather novel dimension considered in the literature that might advance understanding emotions’ functions 53 .

Participants reported valence on a scale from 1 ( extremely negative ) to 10 ( extremely positive ) or approach/avoidance motivational tendency on a scale from 1 ( extreme avoidance motivational tendency ) to 10 ( extreme approach motivational tendency ). Participants were asked to adjust the rating scale position as often as necessary so that it always reflected how they felt at a given moment. For valence, we asked the participants to move the tag to the right side of the scale when they felt more positive or pleasant and to move the tag to the left side of the scale when they felt more negative or unpleasant. For the approach/avoidance motivational tendency, we asked the participants to move the tag to the right side of the scale when they felt the motivation to go toward or engage with the stimulus and to move the tag to the left side of the scale when they felt the motivation to go away or disengage with the stimulus. Previous research indicated that rating scales are valid for reporting the intensity of valence and approach/avoidance motivation 24 , 51 , 54 .

The signal was sampled at a rate of 1 kHz by Powerlab 16/35 (ADInstruments). Furthermore, we provided a validated positive-negative (Study 3–6) or approach-avoidance (Study 1,2 & 7) graphical scale modeled after the self-assessment manikin above the numeric scale 38 , 55 .

Electrocardiography

We used two electrocardiographs (ECG), BioAmp with Powerlab 16/35 AD converter (ADInstruments, New Zealand) (Study 1,2,4 & 5) and Vrije Universiteit Ambulatory Monitoring System (VU-AMS, the Netherlands) (Study 3, 6 & 7). We used pre-gelled AgCl electrodes placed in a modified Lead II configuration. The signal was stored on a computer with other biosignals using a computer‐based data acquisition and analysis system (LabChart 8.1; ADInstruments or VU-AMS Data, Analysis & Management Software; VU-DAMS 3.0). The ECG signal was sampled at a frequency of 1 kHz. ECG signal allows the computation of numerous indexes with the most popular involving 1) heart rate, which reflects the autonomic arousal, associated with, e.g., dually innervated sympathetic nervous system (SNS) and parasympathetic nervous system (PNS) activity, and is related to motivational intensity, action readiness, and engagement 56 , 57 , and 2) heart rate variability linked with stress, self-regulatory efforts, and recovery from stress 58 .

Impedance Cardiography

We recorded the impedance cardiography (ICG) signal continuously and noninvasively with the Vrije Universiteit Ambulatory Monitoring System (VU-AMS, the Netherlands) following psychophysiological guidelines 59 , 60 . We used pre-gelled AgCl electrodes placed in a four-spot electrode array for ICG 59 . The signal was stored on a computer with other biosignals using a computer‐based data acquisition and analysis system (VU-DAMS 3.0). The ICG signal was sampled at a frequency of 1 kHz. ICG provided three channels: baseline impedance (Z0), sensed impedance signal (dZ), and its derivative over time (dZ/dt). In addition to ECG signal, ICG signal allows the computation of indexes linked to the pace and blood volume of the heartbeats, including (1) pre-ejection period reflecting sympathetic cardiac efferent activity which is associated, e.g., with motivational intensity and engagement 56 , 57 ; (2) stroke volume which is linked with stress 61 ; and (3) cardiac output which is used, e.g., to discriminate between challenge vs. threat stress response 62 .

Hemodynamic measures

We recorded hemodynamic responses using two models of the Finometer: Finometer MIDI (Finapres Medical Systems, Netherlands) (Study 1, 2, 4 & 5) and Finometer NOVA (Finapres Medical Systems, Netherlands) (Study 3, 5 & 6). Finometers provided systolic blood pressure (SBP), diastolic blood pressure (DBP), cardiac output (CO), and total peripheral resistance (TPR). SBP, DBP, CO, TPR were recorded continuously beat-by-beat (only in Study 1, we recorded SBP and DBP as a raw signal). Finometers use the volume-clamp method first developed by Penaz 63 to measure finger arterial pressure waveforms with finger cuffs. The data were exported to the Powerlab 16/35 data acquisition system (ADInstruments, New Zealand) and LabChart 8.1 (ADInstruments, New Zealand) (Study 1, 3 & 4) or collected with BeatScope 2.0 (Finapres Medical Systems, Netherlands) 64 (Study 2, 5 & 6). SBP and DBP is used to assess, e.g., effort investment 54 or cardiovascular health risk 65 , whereas CO and TPR are used to differentiate between challenge vs. threat stress response 56 .

Electrodermal activity

We recorded the electrodermal activity (EDA) with the GSR Amp (ADInstruments) at 1 kHz. We used electrodes with adhesive collars and sticky tape attached to the medial phalanges of digits II and IV of the left hand. The electrodes had a contact area of 8 mm diameter and were filled with a TD‐246 sodium chloride skin conductance paste. The signal was stored on a computer with other biosignals using a computer‐based data acquisition and analysis system (LabChart 8.1; ADInstruments). Skin conductance reflects beta-adrenergic sympathetic activity, and some examples of its use comprise mental stress, cognitive load, and autonomic arousal 66 .

Respiration

In Study 1, we recorded respiratory action with a piezo-electric belt, Pneumotrace II (UFI, USA), sampled at 1 kHz. The belt was attached around the upper chest near the level of maximum amplitude for thoracic respiration. The signal was stored on a computer with other biosignals using a computer‐based data acquisition and analysis system (LabChart 8.1; ADInstruments). The respiratory action allows the computation of respiratory rate and depth associated, e.g., with mental stress 67 , arousal 68 , and increases in negative emotion, e.g., anger and fear 5 .

Fingertip skin temperature

In Study 1, we measured fingertip temperature with a temperature probe attached to a Thermistor Pod (ADInstruments, New Zealand). The thermometer was attached at the distal phalange of the left hand’s V finger, sampled at 1 kHz. The signal was stored on a computer with other biosignals using a computer‐based data acquisition and analysis system (LabChart 8.1; ADInstruments). Changes in digit temperature reflect sympathetically innervated peripheral vasoconstriction and vasodilation that decreases or increases the fingertip temperature due to lower or higher blood supply. For instance, the fingertip temperature decreases in response to stress 69 and increases in response to joy 70 . Fingertip temperature is usually lower than other body temperature measures, e.g., the axillary or oral temperature 71 . Moreover, fingertip skin temperature can be much lower for some participants due to individual differences in hand morphology as well as ambient temperature. For instance, thermoregulatory cold-induced vasodilation occurs when hands are exposed to cold weather in winter 72 .

Data acquisition

Figure 1 presents the experiments and the data acquisition setup. Stimuli were managed through E-Prime (Psychology Software Tools, Inc.). E-Prime software sent the markers to the data acquisition devices (LabChart and VU-AMS), by which we were able to synchronize and merge the recordings from different devices into a single data file. The rating scale, ECG, EDA, thermometer, and respiratory belt were directly connected to the Powerlab 16/35 and then to the acquisition personal computer (PC) over a USB port. The ECG and ICG were directly connected to the VU-AMS and then to the acquisition PC3 over a USB port. The blood pressure measures were collected via a finger cuff directly connected to the Finometers and then to the acquisition PC over a USB port. We synchronized LabChart and VU-AMS with Finometer data by manually adding the markers at the same time during data recording. Data were managed in the following manner: 1) Powerlab data was stored in LabChart 8.0; 2) VU-AMS data was stored in VU-DAMS; and 3) Finometer data were stored in BeatScope. The acquired data from each participant was exported with the timestamp provided by the acquisition PC and markers into the TXT data files.

Data preprocessing

Physiological data collected across seven studies were exported from the acquisition formats by the first author [MBe]. The participants’ number differs from the initial studies due to various issues such as device malfunction, signal artifacts, and missing data files. We presented data that had high signal quality. Thus, some participants’ data from some channels (devices) were excluded, resulting in an 8% decrease in the participants’ pool.

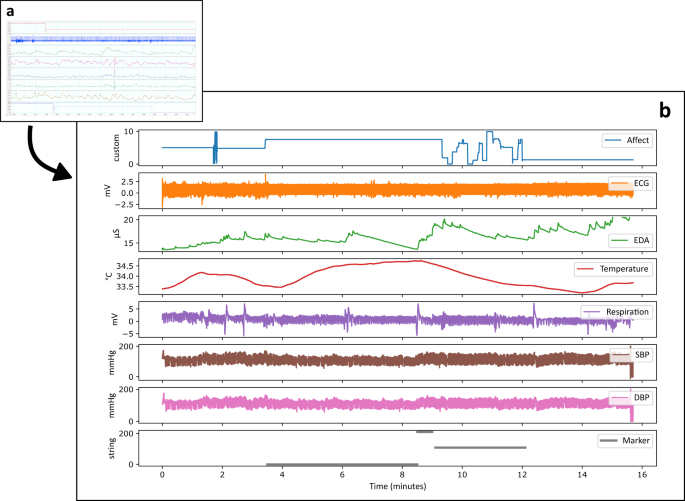

The exported TXT, CSV, and metadata files were preprocessed using Python 73 , 74 scientific libraries (e.g., pandas 1.1.5, numpy 1.19.2; see Code Availability, for detailed information) (Fig. 2a ). All signals were resampled to 1 kHz, using the previous neighbor interpolation method (Fig. 2b ). Signals from different devices were time-synchronized using synchronization markers generated during experiments. We marked the baselines and emotion elicitations within the files. Finally, data across studies were exported to a normalized form, consisting of a header, a predefined file structure, and a standardized subject naming convention.

Schematic presentation of data preprocessing. The data were first exported from the acquisition software (panel a) and then preprocessed and integrated into CSV files. The resulting CSV files can be easily loaded into most statistical software and packages, such as IBM’s SPSS or Python Pandas & SciPy modules (for visualization in Python’s Pandas module, see panel b).

Data Records

The POPANE dataset is publicly available at the Open Science Framework repository 32 .

We present auxiliary information about the experiments in the metadata spreadsheet. The metadata file includes participants’ ID, sex, age, height, weight, experimental conditions for each study, stimuli order within a session, and information about missing data, outliers, and artifacts (sheets “Study 1–7”). Furthermore, the metadata file provides information on individuals that participated more than once across the studies by showing all their study-related IDs. The description of labels used for tagging discrete emotions is also available in the metadata file (the “ stimuli ” spreadsheet).

Dataset structure

The data repository consists of seven ZIP-compressed directories (folders), one for each study, e.g., “Study1” directory was compressed to “Study1.zip” archive file, “Study2” was compressed as “Study2.zip”, etc. Each of these directories contains a set of CSV files with psychophysiological information for particular subjects. We used a consistent CSV file naming convention, i.e.: “S < study_id > _P < participant_id > _ < phase_name > .csv”, where “S” stands for study, “P” for participants, e.g.: S1_P10_Baseline.csv, or S6_P4_Amusement1.csv. The “ < study_id > ” & “ < particpant_id > ” are natural numbers identifying a study and a participant. The “ < phase_name > “ is the name of the phase of an experiment, e.g., “Baseline”, or “Amusement1”. The description of all experimental-phase labels is explained in the metadata spreadsheet. All psychophysiological signals recorded during the experiment for each individual are also available in a single CSV datafile named “S < study_id > _P < participant_id > _All.csv”. All the other files for a particular participant named in the following manner: “S < study_id > _P < participant_id > _ < phase_name > .csv” are files containing a subset of records (an excerpt) extracted from a basic “S < study_id > _P < participant_id > _All.csv” file. Thus, “S < study_id > _P < participant_id > _All.csv” files store either signals related to a particular experimental phase or signals gathered during time intervals, where no experimental conditions were present, i.e., signals that were not related to the affective manipulation.

Furthermore, we also included one additional component, i.e., “POPANE dataset”. This component contains a set of ZIP-compressed directories with a set of CSV files with psychophysiological information for particular participants, baselines, and emotions. We grouped the datafiles from all studies into a single folder sorted by emotions. This simplifies the usage of our dataset as the single set of emotion-related data from all 1157 cases.

A sample from Study 1 is available for preview and testing and can be obtained from the data repository as “Study1_sample.zip”. The compressed sample file size is 42 MB (208 MB uncompressed), as compared to 2.0 GB (9.3 uncompressed) of the complete dataset for Study 1. This provides potential users of the dataset with an opportunity to get the notion of the data without downloading the whole dataset. For the visualization of these sample data, see Fig. 2b .

Single file structure

Each of the CSV files in the dataset has a 11-line header, i.e., each file’s first eleven rows start with a hash sign (“#“). In the header, file metadata is available, including:

ID of the study as a variable “Study_name”, e.g., “Study_7”;

participant’s ID within the study as a variable “Subject_ID”, e.g., “119”;

participant’s age as a variable “Participant_Age”, e.g., “23”;

participant’s sex coded as man = 0, woman = 1, as a variable “Subject_Sex”;

participant’s height in centimeters as a variable “Participants_Height”, e.g. “178”;

participant’s weight in kilograms as a variable “Participants_Weight”, e.g. “74”;

channel/sensor name as a variable “Channel_Name”, e.g., “timestamp”, “affect”, “ECG”, “dzdt”, “dz”, “z0”, or “marker”;

category of the data in each column as a variable “Data_Category”, e.g., “timestamp”, “data”, and “marker”;

units of the measurement as a variable “Data_Unit”, e.g.: “second”, “millivolt”, or “ohm”;

sample rate of data collection as a variable “Data_Sample_rate”, e.g.: “1000 Hz”, or “beat to beat”;

name of the device (manufacturer) used for data collection as a variable “Data_Device”, e.g., “LabChart_8.19_(ADInstruments,_New Zealand)”, “Response_Meter_(ADInstruments,_New Zealand)”, or “ECG (Vrije_Universiteit_Ambulatory_Monitoring_System,_VU-AMS,_the Netherlands)”.

If no data are available for the participant’s age, sex, height, and weight, we inserted a value of “−1”.

Following the header, each CSV file contains 7–12 columns, depending on the study. For studies in which data were gathered from more channels, there are more columns in CSV files. Sensor names used in all studies are consistent across all CSV files (see the metadata file). The first column of the data table (except for the header) contains timestamps, as provided by a clock on the main data acquisition (logging) computer – the timestamp format is time in seconds. In the last column, there is a marker that identifies the specific phase of the experiment. The metadata file provides a full explanation of the stimulus IDs used to mark the specific phase of the experiment, e.g., “−1” indicates the experimental baseline, while “107” indicates the neutral film clip “The Lover”. The columns in between the timestamp and the marker contain the physiological data (see Table 3 for details).

We used different acquisition programs; therefore, the exported data had to be integrated into a common format. An automatic preprocessing procedure was implemented in Python scripts. We converted the raw acquired data (obtained with a proprietary acquisition software) into a consistent format and saved it in CSV files. Consequently, data from several sources were integrated to be easily imported into all common statistical software packages. We also prepared examples in IPython Jupyter Notebooks presenting how to load and visualize psychophysiological data from sample files for Study 1. Both the conversion scripts and the Notebooks can be obtained from our source code repository available at GitHub: https://github.com/psychosensing/popane-2021 .

Technical Validation

Qualitative validation.

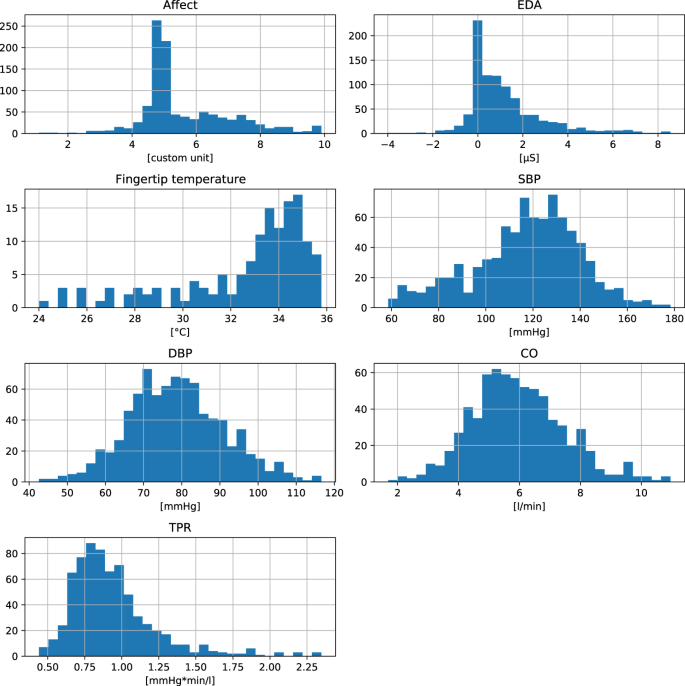

The data quality was assured by following recommendations in affective science 3 . First, we used validated methods (e.g., protocols and stimuli) to elicit emotions in our experiments. We used stimuli in line with well-established methods in the affective science 21 . Second, the data were collected by experimenters that completed 30 h training in psychophysiological research provided by MBe and LDK. Third, prior to performing preprocessing, the first author (MBe) visually inspected all physiological signals. Before inclusion in the database, MBe manually double-checked all datasets for missing or corrupted data. Table 4 presents missing data for each stimulus and physiological signal. The histograms in Figure 3 show the distributions of the selected physiological signals during the resting baseline. Figure 3 also presents that collected signals had standard ranges. For instance, most participants presented a healthy SBP and DBP range during the resting baseline of the experiments 75 . This figure does not present raw recordings (e.g., ECG in mV) that require further processing (e.g., breathing rate based on peak analysis).

Data histograms of baseline psychophysiological levels. This figure presents the distribution of the mean psychophysiological levels for resting baseline but does not present raw recordings (e.g., ECG in mV) that require further processing (e.g., analysis to calculate HR or HRV).

Quantitative validation

We evaluated the quality of the signal with the Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR). In order to calculate SNR across the diverse physiological signals, we used an algorithm based on the autocorrelation function of the signal, using the second-order polynomial for fitting the autocorrelation function curve 76 . The script we used for calculating SNR is available in the project’s GitHub repository ( https://github.com/psychosensing/popane-2021 ). We calculated SNR for all baselines and emotion elicitations across seven studies (Table 5 ). The calculated SNR indicated the high quality of all collected signals 77 , SNR min = 5.67 dB, with mean SNR ranging from 37.82 dB to 67.39 dB depending on physiological signal and study. We identified outliers above SNRs’ z -scores higher than 3.29 78 , resulting in 290 parts (1.09% of all calculated SNR values) identified as SNR outliers. Next, the first author (MBe) visually inspected all flagged data to determine whether it should be classified as artifacts, resulting in 257 SNR outlying data points being identified as artifacts (88% of the low SNR data; less than 0.96% of all calculated SNR values). Both outliers and artifacts are presented in the metadata file.

Previous studies

For each study represented in the dataset, we ran manipulation checks that contributed to the technical validation. We found that the stimuli produced expected affective and physiological responses in participants 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 . For instance, in Study 5, we found that individuals who watched the positive film clips reported more positive valence, whereas individuals who watched the negative film clips reported more negative valence, compared to individuals who watched the neutral film clips 36 . Furthermore, individuals in the positive and negative emotion conditions displayed greater physiological reactivity (e.g., SBP and DBP) than individuals in the neutral conditions 36 .

Usage Notes

The POPANE dataset is available at https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/94BPX . The data in the datasets are saved in CSV format. The dataset can be used to test hypotheses on positive and negative emotions, create psychophysiological models and/or standards, or as an example data for testing technical aspects of the analyses and/or validation of mathematical models. These data can be of interest for several scientific fields such as psychology, e.g., for investigating human emotions based on physiological and psychometric information, or computer science (machine learning) for implementing automatic emotion recognition, or clustering data related to particular emotions.

Limitations

There are some shortcomings of our dataset. First, some data are missing because recordings for some of the participants could not be reliably collected due to technical reasons. Second, this dataset cannot be employed to investigate psychophysiological differences between ethnicities, neither between the group ages, as more than 99% of the participants were Caucasian young adults. This is an important limitation because some studies indicated physiological differences in baseline levels and reactivity to some stressors depending on the participant’s age 79 , 80 and ethnicity 81 . Moreover, some studies in the dataset recruited only male participants. This is important to control if the whole dataset would be used for testing hypotheses regarding sex differences 82 . Third, our dataset does not include participants diagnosed with cardiovascular disease. However, we did not collect information about other health issues, e.g., psychiatric or neurological diagnosis.

Fourth, this dataset is a posteriori use of the previously acquired data in already published independent studies. However, some participants (12%) took part in more than one study. We identified these participants in the metadata file. Thus, if the whole dataset is used to test hypotheses, researchers should consider this issue. In contrast, some authors might be particularly interested in the use of repeated data collected from the same participants, e.g., to test intraperson stability or change.

Fifth, most of the film clips were short excerpts from commercially available films. Thus, some of our participants might have already been familiar with them.

Sixth, in our studies, we measured autonomic nervous system (ANS) reactivity to nine discrete emotions. This is not an exhaustive list of affective states related to ANS activity. Future studies may focus on emotions that are examined less often in psychophysiological studies, including pride, craving, love, or embarrassment 6 . Furthermore, the emotions elicited in our studies were not balanced in valence, as some studies were focused on the differences between neutral conditions and positive emotions (Study 3) or negative emotions (Study 4).

In summary, the POPANE database is a large and comprehensive psychophysiological dataset on emotions. We hope that POPANE will provide individuals, companies, and laboratories with the data they need to perform their analyses to advance the fields of affective science, physiology, and psychophysiology. We invite you to visit the project website https://data.psychosensing.psnc.pl/popane/index.hml .

GitHub repository

Scripts for converting data from proprietary acquisition software formats into consistent CSV files, as well as IPython Jupyter Notebooks presenting how to load the data from POPANE CSV files into Python Pandas DataFrame structure are available at the following GitHub repository: https://github.com/psychosensing/popane-2021 .

Code availability

The code can be accessed on the public GitHub repository: https://github.com/psychosensing/popane-2021 . It is licensed under MIT OpenSource license, i.e., the permission is granted, free of charge, to obtaining a copy of this software and associated files (e.g., the Jupyter IPython Notebooks), subject to the following conditions: the copyright notice and the MIT license permission notice shall be included in all copies or substantial portions of the software based on the scripts we published.

Scripts that we used to transform the data from proprietary acquisition formats into coherent CSV files utilized Python 3.6 83 . The list of the specific modules and their versions is available in the “requirements.txt” file in the GitHub repository.

Jupyter Notebooks use Python version: 3.5.3, as well as the following Python modules: packages related to Jupyter Notebook: notebook module v. 6.1.4; jupyter-core module v. 4.6.3, jupyter-client v. 6.1.7; ipython v. 7.9.0; ipykernel v. 5.3.4 84 ; and a data organization and manipulation module – pandas v. 0.25.3 73 .

Gross, J. J. Emotion regulation: Current status and future prospects. Psychol. Inq. 26 , 1–26 (2015).

Article Google Scholar

Mauss, I. B., Levenson, R. W., McCarter, L., Wilhelm, F. H. & Gross, J. J. The tie that binds? Coherence among emotion experience, behavior, and physiology. Emotion 5 , 175–190 (2005).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Levenson, R. W. The autonomic nervous system and emotion. Emot. Rev. 6 , 100–112 (2014).

Mendes, W. B., & Park, J. in Advances in Motivation Science: Vol. 1 (ed. Elliot, A. J.) Neurobiological concomitants of motivational states . (Elsevier Academic Press, 2014).

Siegel, E. H. et al . Emotion fingerprints or emotion populations? A meta-analytic investigation of autonomic features of emotion categories. Psychol. Bull. 144 , 343–393 (2018).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Kreibig, S. D. Autonomic nervous system activity in emotion: A review. Biol Psychol. 84 , 394–421 (2010).

Cannon, W. B. Bodily Changes in Pain, Hunger, Fear and Rage: An Account of Recent Researches into the Function of Emotional Excitement (D Appleton & Company, 1915).

Cannon, W. B. The James-Lange theory of emotions: a critical examination and an alternative theory. Am. J. Psychol. 39 , 106–124 (1927).

James, W. What is an emotion? Mind 9 , 188–205 (1884).

Lange, C. G. in The Classical Psychologist (ed. Rand B.) The mechanism of the emotions. (Houghton Mifflin, 1885).

Brown, C. L. et al . Coherence between subjective experience and physiology in emotion: Individual differences and implications for well-being. Emotion 20 , 818–829 (2020).

Kaczmarek, L. D. et al . Effects of emotions on heart rate asymmetry. Psychophysiology. 56 , e13318 (2019).

Kukolja, D., Popović, S., Horvat, M., Kovač, B. & Ćosić, K. Comparative analysis of emotion estimation methods based on physiological measurements for real-time applications. Int. J. Hum-Comput. St. 72 , 717–727 (2014).

Boehm, J. K. et al . Positive emotions and favorable cardiovascular health: A 20-year longitudinal study. Prev. Med. 136 , 106103 (2020).

Ekman, P. & Cordaro, D. What is meant by calling emotions basic. Emot. Rev. 3 , 364–370 (2011).

Davidson, R. J. Affective neuroscience and psychophysiology: toward a synthesis. Psychophysiology 40 , 655–665 (2003).

Kivikangas, J. M. et al . A review of the use of psychophysiological methods in game research. J. Gaming Virtual Worlds. 3 , 181–199 (2011).

Brave, S. & Nass, C. Emotion in human–computer interaction. Hum-Comput. Interact. 53 , 53–68 (2003).

Google Scholar

McStay, A. Emotional AI: The Rise of Empathic Media (SAGE, 2018).

Picard, R. W. Affective computing: from laughter to IEEE. IEEE T. Affect. Comput. 1 , 11–17 (2010).

Joseph, D. L. et al . The manipulation of affect: A meta-analysis of affect induction procedures. Psychol. Bull. 146 , 355–375 (2020).

Gross, J. J. & Levenson, R. W. Emotion elicitation using films. Cognition Emotion. 9 , 87–108 (1995).

Schaefer, A., Nils, F., Sanchez, X. & Philippot, P. Assessing the effectiveness of a large database of emotion-eliciting films: A new tool for emotion researchers. Cognition Emotion. 24 , 1153–1172 (2010).

Marchewka, A., Żurawski, Ł., Jednoróg, K. & Grabowska, A. The Nencki Affective Picture System (NAPS): Introduction to a novel, standardized, wide-range, high-quality, realistic picture database. Behav. Res. Methods 46 , 596–610 (2014).

Mendes, W. B., Major, B., McCoy, S. & Blascovich, J. How attributional ambiguity shapes physiological and emotional responses to social rejection and acceptance. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 94 , 278–291 (2008).

Wager, T. D. et al . Brain mediators of cardiovascular responses to social threat: part I: Reciprocal dorsal and ventral sub-regions of the medial prefrontal cortex and heart-rate reactivity. Neuroimage 47 , 821–835 (2002).

Kirschbaum, C., Pirke, K. M. & Hellhammer, D. H. The ‘Trier Social Stress Test’–a tool for investigating psychobiological stress responses in a laboratory setting. Neuropsychobiology 28 , 76–81 (1993).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Koelstra, S. et al . Deap: A database for emotion analysis; using physiological signals. IEEE T. Affect. Comput. 3 , 18–31 (2011).

Ringeval, F., Sonderegger, A., Sauer, J., & Lalanne, D. Introducing the RECOLA multimodal corpus of remote collaborative and affective interactions. In 2013 10th IEEE international conference and workshops on automatic face and gesture recognition , 1–8 (2013).

Sharma, K., Castellini, C., van den Broek, E. L., Albu-Schaeffer, A. & Schwenker, F. A dataset of continuous affect annotations and physiological signals for emotion analysis. Sci. Data 6 , 196 (2019).

Park, C. Y. et al . K-EmoCon, a multimodal sensor dataset for continuous emotion recognition in naturalistic conversations. Sci. Data 7 , 1–16 (2020).

Article CAS Google Scholar

Behnke, M. et al . POPANE DATASET - Psychophysiology Of Positive And Negative Emotions. Open Science Framework https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/94BPX (2021).

Kaczmarek, L. D. et al . High-approach and low-approach positive affect influence physiological responses to threat and anger. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 138 , 27–37 (2019).

Enko, J., Behnke, M., Dziekan, M., Kosakowski, M. & Kaczmarek, L. D. Gratitude texting touches the heart: challenge/threat cardiovascular responses to gratitude expression predict self-initiation of gratitude interventions in daily life. J. Happiness Stud. 22 , 49–69 (2021).

Drążkowski, D., Behnke, M. & Kaczmarek, L. D. I am afraid to buy this! Manipulating with consumer’s anxiety and self-construal. PLOS One. 16 , e0256483 (2021).

Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar

Kaczmarek, L.D. et al . Positive emotions boost enthusiastic responsiveness to capitalization attempts. Dissecting self-report, physiology, and behavior, J Happiness Stud . (Accepted Manuscript) (2021).

Kosakowski, M. The effect of emodiversity on cardiovascular responses during the interpersonal limited resources conflict. Examinations of affective states and traits within the framework of polyvagal theory. Unpublished doctoral dissertation . Adam Mickiewicz University, Poznan, Poland (2021).

Behnke, M., Gross, J.J., Kaczmarek, L.D. The Role of Emotions in Esports Performance. Emotion . (2020).

Behnke, M., Hase, A., Kaczmarek, L. D. & Freeman, P. Blunted Cardiovascular Reactivity May Serve as an Index of Psychological Task Disengagement in the Motivated Performance Situations. Sci. Rep. 11 , 18083 (2021).

Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Bearden, J. N. Ultimatum bargaining experiments: The state of the art (SSRN eLibrary, 2001).

Fredrickson, B. L., Mancuso, R. A., Branigan, C. & Tugade, M. M. The undoing effect of positive emotions. Motiv. Emotion 24 , 237–258 (2000).

Neumann, S. A., Sollers, J. J., Thayer, J. F. & Waldstein, S. R. Alexithymia predicts attenuated autonomic reactivity, but prolonged recovery to anger recall in young women. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 53 , 183–195 (2004).

Waldstein, S. R. et al . Frontal electrocortical and cardiovascular reactivity during happiness and anger. Biol. Psychol. 55 , 3–23 (2000).

Why, Y. P. & Johnston, D. W. Cynicism, anger and cardiovascular reactivity during anger recall and human–computer interaction. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 68 , 219–227 (2008).

Seligman, M. E. P., Steen, T. A., Park, N. & Peterson, C. Positive psychology progress. Empirical validation of interventions. Am. Psychol. 60 , 410–421 (2005).

Wood, A. M., Froh, J. J. & Geraghty, A. W. Gratitude and well-being: A review and theoretical integration. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 30 , 890–905 (2010).

Lin, I. & Peper, E. Psychophysiological patterns during cell phone text messaging: a preliminary study. Appl. Psychophys. Biof. 34 , 53–57 (2009).

Hewig, J. et al . Brief Report: A revised film set for the induction of basic emotions. Cognition Emotion. 19 , 1095–1109 (2005).

Kaczmarek, L. D. et al . Splitting the affective atom: Divergence of valence and approach-avoidance motivation during a dynamic emotional experience, Curr. Psychol . 1–12 (2019).

Reynaud, E., El Khoury-Malhame, M., Rossier, J., Blin, O. & Khalfa, S. Neuroticism modifies psychophysiological responses to fearful films. PloS One. 7 , e32413 (2012).

Ruef, A. M., & Levenson, R. W. in Series in Affective Science. Handbook of Emotion Elicitation and Assessment (eds. Coan, J. A. & Allen, J. J. B.). Continuous measurement of emotion: The affect rating dial (Oxford University Press, 2007).

Harmon-Jones, E., Harmon-Jones, C. & Price, T. F. What is approach motivation? Emot. Rev. 5 , 291–295 (2013).

Gable, P. & Harmon-Jones, E. The motivational dimensional model of affect: Implications for breadth of attention, memory, and cognitive categorization. Cognition Emotion. 24 , 322–337 (2010).

Cowen, A. S. & Keltner, D. Self-report captures 27 distinct categories of emotion bridged by continuous gradients. P. Natl. A. Sci. 114 , E7900–E7909 (2017).

Bradley, M. M., & Lang, P. J. Measuring emotion: the self-assessment manikin and the semantic differential. J. Behav. Ther. Exp. Psy . 25 , 49–59 (1994).

Blascovich, J. in Handbook of Approach and Avoidance Motivation (eds. Elliot, A. J.) Challenge and threat (Psychology Press, 2008).

Richter, M., Gendolla, G. H., & Wright, R. A. In Advances in Motivation Science (ed. Elliot, A. J.) Three decades of research on motivational intensity theory: What we have learned about effort and what we still don’t know (Waltham, MA: Academic Press. 2016).

Balzarotti, S., Biassoni, F., Colombo, B. & Ciceri, M. R. Cardiac vagal control as a marker of emotion regulation in healthy adults: A review. Biol. Psychol. 130 , 54–66 (2017).

Sherwood, A. et al . Methodological guidelines for impedance cardiography. Psychophysiology 27 , 1–23 (1990).

van Lien, R., Neijts, M., Willemsen, G. & de Geus, E. J. Ambulatory measurement of the ECG T‐wave amplitude. Psychophysiology 52 , 225–237 (2015).

Nelesen, R., Dar, Y., Thomas, K. & Dimsdale, J. E. The relationship between fatigue and cardiac functioning. Arch. Intern. Med. 168 , 943–949 (2008).

Behnke, M. & Kaczmarek, L. D. Successful performance and cardiovascular markers of challenge and threat: A meta-analysis. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 130 , 73–79 (2018).

Penaz, J. Photoelectric measurement of blood pressure, volume and flow in the finger. In Digest of the 10th International Conference on Medical and Biological Engineering . 104 (1973).

Wesseling, K. H., Wit de, B., Hoeven van der, G. M. A., Goudoever van, J. & Settels, J. J. Physiocal, calibrating finger vascular physiology for finapres. Homeostasis Hlth. Dis. 36 , 67–82 (1995).

Bundy, J. D. et al . Systolic blood pressure reduction and risk of cardiovascular disease and mortality: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. JAMA Cardiol. 2 , 775–781 (2017).

Boucsein, W. Electrodermal Activity (Springer, 2012).

Grossman, P. Respiration, stress, and cardiovascular function. Psychophysiology. 20 , 284–300 (1983).

Boiten, F. A., Frijda, N. H. & Wientjes, C. J. Emotions and respiratory patterns: review and critical analysis. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 17 , 103–128 (1994).

Vinkers, C. H. et al . The effect of stress on core and peripheral body temperature in humans. Stress 16 , 520–530 (2013).

Rimm-Kaufman, S. E. & Kagan, J. The psychological significance of changes in skin temperature. Motiv. Emotion. 20 , 63–78 (1996).

Tansey, E. A., Roe, S. M. & Johnson, C. D. The sympathetic release test: a test used to assess thermoregulation and autonomic control of blood flow. Adv. Physiol. Educ. 38 , 87–92 (2014).

Mekjavic, I. B., Dobnikar, U., Kounalakis, S. N., Musizza, B. & Cheung, S. S. The trainability and contralateral response of cold-induced vasodilatation in the fingers following repeated cold exposure. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 104 , 193–199 (2008).

McKinney, W. Data Structures for Statistical Computing in Python. Proceedings of the 9th Python in Science Conference, 1 56–61 (2010).

Virtanen, P. et al . SciPy 1.0: fundamental algorithms for scientific computing in Python. Nat. Methods 17 , 261–272 (2020).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Prospective Studies Collaboration. Age-specific relevance of usual blood pressure to vascular mortality: a meta-analysis of individual data for one million adults in 61 prospective studies. The Lancet 360 , 1903–1913 (2002).

Thong, J. T. L., Sim, K. S. & Phang, J. C. H. Single image signal to noise ratio estimation. Scanning 23 , 328–336 (2001).

Sijbers, J., Scheunders, P., Bonnet, N., Van Dyck, D. & Raman, E. Quantification and improvement of the signal-to-noise ratio in a magnetic resonance image acquisition procedure. Magn. Reason. Imaging 14 , 1157–1163 (1996).

Field, A. Discovering statistics using IBM SPSS statistics (Sage, 2013).

Steenhaut, P., Demeyer, I., De Raedt, R. & Rossi, G. The role of personality in the assessment of subjective and physiological emotional reactivity: a comparison between younger and older adults. Assessment 25 , 285–301 (2018).

Charles, S. T. & Carstensen, L. L. Unpleasant situations elicit different emotional responses in younger and older adults. Psychol. Aging 23 , 495–504 (2008).

Vrana, S. R. & Rollock, D. The role of ethnicity, gender, emotional content, and contextual differences in physiological, expressive, and self-reported emotional responses to imagery. Cognition Emotion 16 , 165–192 (2002).

Bradley, M. M., Codispoti, M., Sabatinelli, D. & Lang, P. J. Emotion and motivation II: sex differences in picture processing. Emotion 1 , 300–319 (2001).

Van Rossum, G., & Drake Jr, F. L. Python Tutorial (Vol. 620). (Amsterdam: Centrum voor Wiskunde en Informatica, 1995).

Kluyver, T. et al . in Positioning and Power in Academic Publishing: Players, Agents and Agendas - Proceedings of the 20th International Conference on Electronic Publishing, ELPUB 2016 (eds. Loizides, F. & Schmidt, B.) Jupyter Notebooks—a publishing format for reproducible computational workflows (IOS Press, 2016).

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Michał Kosakowski, Jolanta Enko, Martyna Dziekan, Dariusz Drążkowski and other members of Psychophysiology and Health Lab at Adam Mickiewicz University for helping in data collection. The authors thanks Katarzyna Janicka ([email protected]) for creating Fig. 1. Preparation of this article was supported by the National Science Center (Poland) research grants (UMO-2017/25/N/HS6/00814; UMO-2012/05/B/HS6/00578; UMO-2013/11/N/HS6/01122; UMO-2014/15/B/HS6/02418; UMO-2014-15/N/HS6/04151; UMO-2015/17/N/HS6/02794; UMO-2016/21/B/ST6/01463) and doctoral scholarship (UMO-2019/32/T/HS6/00039) and by Faculty of Psychology and Cognitive Sciences, Adam Mickiewicz University research grant #18/11/2020.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Adam Mickiewicz University, Faculty of Psychology and Cognitive Science, Poznan, 61-664, Poland

Maciej Behnke & Lukasz D. Kaczmarek

Wrocław University of Science and Technology, Faculty of Information and Communication Technology, Wrocław, 50-370, Poland

Maciej Behnke

Poznan Supercomputing and Networking Center, Network Services Division, Poznan, 61-139, Poland

Mikołaj Buchwald, Adam Bykowski & Szymon Kupiński

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

A.B. coded the software for the data preprocessing, developed the dataset, contributed to the technical validation, and composed the manuscript’s first draft. L.D.K. collaborated in the design of all the experimental setups, supervised the data collection and technical validation, secured funding for the work, and managed the project. M.Be. designed the experimental setup for Study 7, supported the data collection in all studies, verified the dataset, developed the dataset, contributed to the technical validation, composed the manuscript’s first draft, secured funding for the work, and managed the project. M.Bu. developed the dataset, contributed to the technical validation, and composed the manuscript’s first draft. S.K. supervised the data processing and technical validation. All authors critically reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Maciej Behnke .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ applies to the metadata files associated with this article.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Behnke, M., Buchwald, M., Bykowski, A. et al. Psychophysiology of positive and negative emotions, dataset of 1157 cases and 8 biosignals. Sci Data 9 , 10 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-021-01117-0

Download citation

Received : 12 April 2021

Accepted : 09 December 2021

Published : 20 January 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-021-01117-0

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

Physiological data for affective computing in hri with anthropomorphic service robots: the affect-hri data set.

- Judith S. Heinisch

- Jérôme Kirchhoff

- Klaus David

Scientific Data (2024)

From face detection to emotion recognition on the framework of Raspberry pi and galvanic skin response sensor for visual and physiological biosignals

- Varsha Kiran Patil

- Vijaya R. Pawar

- Aditya Kiran Patil

Journal of Electrical Systems and Information Technology (2023)

A physiological signal database of children with different special needs for stress recognition

- Buket Coşkun

- Devrim Tarakci

Scientific Data (2023)

The hybrid discrete–dimensional frame method for emotional film selection

- Xuanyi Wang

- Huiling Zhou

- Shulin Chen

Current Psychology (2023)

Emognition dataset: emotion recognition with self-reports, facial expressions, and physiology using wearables

- Stanisław Saganowski

- Joanna Komoszyńska

- Przemysław Kazienko

Scientific Data (2022)

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Current Issues The place of Physiological Psychology in Neuroscience

- Published: 04 November 2013

- Volume 12 , pages 3–7, ( 1984 )

Cite this article

- Duane Shuttlesworth 1 ,

- Darryl Neill 2 &

- Paul Ellen 3

2834 Accesses

23 Citations

Explore all metrics

The development of Neuroscience has raised questions about the place of Physiological Psychology in both Psychology and Neuroscience. The present paper addresses the identity crisis of Physiological Psychology by focusing on the concept of the localization of function in the explanation of brain-behavior relationships. The physiological psychologist, dependent upon the reductionistic assumption that behavior can be explained by reduction to some brain event, and the notion that we have a firm understanding of behavioral events and processes, has turned to Neuroscience for both academic identity and research sustenance. But Neuroscience lacks a molar framework, and the consequence of the flight into Neuroscience has been the deterrence of integrative theorizing about brain-behavior relationships. Only through a return to the basic intellectual tradition of our discipline can we negate this trend. By attempting to identify and understand the natural fracture lines of complex adaptive behavioral functions, physiological psychologists can begin to develop the integrative theories that will foster an understanding of brain-behavioral relationships. Doing so has significant implications for what we teach, as well as for the role we play in the Psychology-Neuroscience endeavor of the future.

Article PDF

Download to read the full article text

Similar content being viewed by others

Psychology’s Status as a Science: Peculiarities and Intrinsic Challenges. Moving Beyond its Current Deadlock Towards Conceptual Integration

Who, what, and when: skinner’s critiques of neuroscience and his main targets, psychology and neuroscience: the distinctness question.

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Boring, E. G. (1949). A history of experimental psychology. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts.

Google Scholar

Goldstein, K. (1939). The organism . New York: American Book.

Gregory, R. (1961). The brain as an engineering problem. In R. Thorpe & O. Zangwill (Eds.), Current problems in animal behavior (pp. 307–330). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kandel, E. (1981). Brain and behavior. In E. KANDEL & J. SCHWARTZ (Eds.), Principles of neural science (p. 11). New York: Elsevier-North Holland.

Lashley, K. (1960). Basic neural mechanisms in behavior. In F. Beach, D. Hebb, C. Morgan, & H. Nissen (Eds.), The neuropsychology of Lashley (pp. 207–208). New York: McGraw-Hill.

Laurence, S., & Stein, D. (1978). Recovery after brain damage and the concept of localization of function. In S. Finger (Ed.), Recovery from brain damage: Research and theory . New York: Plenum Press.

Luria, A. (1966). Higher cortical functions in man . New York: Basic Books.

Nadel, L., & O’Keefe, J. (1974). The hippocampus in pieces and patches: An essay on modes of explanation in physiological psychology. In R. Bellairs & E. Gray (Eds.), Essays on the nervous system. A festschrift for Professor J. Z. Young (pp. 367–390). Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Neill, D. (1983, March). Physiological psychology’s place in neuroscience . Paper presented at the 1983 Annual Meeting of the Southeastern Psychological Association, Atlanta, Georgia.

O’Keefe, J., & Nadel, L. (1978). The hippocampus as a cognitive map. London: Oxford University Press.

Olds, J. (1959). High functions of the nervous system. Annual Review of Physiology , 21 , 381–402.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Psychology, Kennesaw College, Marietta, Georgia, 30061, USA

Duane Shuttlesworth

Department of Psychology, Emory University, Atlanta, Georgia, 30322, USA

Darryl Neill

Department of Psychology, Georgia State University, Atlanta, Georgia, 30303, USA

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Additional information

This article is based upon papers presented as part of a symposium entitled “A question of identity: Physiological psychology’s place in neuroscience,” which was held during the 1983 annual meeting of the Southeastern Psychological Association in Atlanta, Georgia. Symposium participants and the titles of their presentations were: D. Shuttlesworth, “Issues underlying the identity crisis within physiological psychology”; D. Neill, “Physiological psychology’s place in neuroscience“; P. Ellen, “Physiological psychology: Alive and well within psychology“; and R. Levitt, “Physiological psychology and clinical neuropsychology.” Discussants were James Kalat and Walter Isaac.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Shuttlesworth, D., Neill, D. & Ellen, P. Current Issues The place of Physiological Psychology in Neuroscience. Psychobiology 12 , 3–7 (1984). https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03332156

Download citation

Received : 17 February 1984

Accepted : 23 February 1984

Published : 04 November 2013

Issue Date : March 1984

DOI : https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03332156

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Physiological Psychology

- Behavioral Function

- Identity Crisis

- Logical Psychology

- Academic Identity

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Aging (Albany NY)

- v.12(18); 2020 Sep 30

Psychological aging, depression, and well-being

Maria mitina.

1 Deep Longevity, Inc., Three Exchange Square, The Landmark, Hong Kong, China

Sergey Young

2 Longevity Vision Fund, New York, NY 10022, USA

Alex Zhavoronkov

3 Insilico Medicine, Hong Kong Science and Technology Park (HKSTP), Hong Kong, China

4 The Buck Institute for Research on Aging, Novato, CA 94945, USA

Aging is a multifactorial process, which affects the human body on every level and results in both biological and psychological changes. Multiple studies have demonstrated that a lower subjective age is associated with better mental and physical health, cognitive functions, well-being and satisfaction with life. In this work we propose a list of non-modifiable and modifiable factors that may possibly be influenced by subjective age and its changes across an individual’s lifespan. These factors can be used for a future development of individual psychological aging clocks, which may be utilized as a sensitive measure for health status and overall life satisfaction. Furthermore, recent progress in artificial intelligence and biomarkers of biological aging have enabled scientists to discover and evaluate the efficacy of potential aging- and disease-modifying drugs and interventions. We propose that biomarkers of psychological age, which are just as important as those for biological age, may likewise be used for these purposes. Indeed, these two types of markers complement one another. We foresee the development of a broad range of parametric and deep psychological and biopsychological aging clocks, which may have implications for drug development and therapeutic interventions, and thus healthcare and other industries.

INTRODUCTION

Like many other species, humans have a shorter lifespan in the absence of medical interventions [ 1 ]. Since the dawn of the 20 th century, life expectancy in developed countries has been steadily increasing primarily due to the decreases in child mortality but also due to the many advances in biotechnology and medicine [ 2 ]. Humans have had to adjust to this increase both as a society and at an individual level. Increasing life expectancy has led to substantial variability in the perception of age, as individuals may perceive themselves and others as substantially younger or older than their chronological age. The perception of subjective age may have profound effects on behavior and well-being, and is connected to an individual’s lifespan [ 3 ]. The socioemotional selectivity theory developed by Laura L. Carstensen at Stanford University, maintains that “the perception of time plays a fundamental role in the selection and pursuit of social goals” [ 4 ]. An extended perception of time may lead to knowledge-based motivations and choices. Conversely, when the perception of time is limited, a person may be motivated to preferentially make emotion-based decisions [ 5 ]. This theory and associated studies have highlighted the importance of the psychology of aging as a field and laid the foundation for studies of psychological and psychophysiological aging markers. While substantial progress has been made in identifying biomarkers of human biological aging, psychological aging is still poorly understood. There is a need for reliable tools for measuring and analyzing psychological aging, and methods for modulating longevity expectations and psychological aging states. In this paper we reflect upon the recent progress in the development of biomarkers of biological aging. We further provide a brief overview of the psychology of aging. We propose that this body of knowledge will lay the foundations for the development of next-generation biomarkers of psychological aging, dubbed psychological aging clocks, as well as deep multi-modal biopsychological and psychophysiological biomarkers of aging.

Numerous studies have demonstrated that molecular and phenotypic biomarkers may be used as effective tools for tracking healthy aging ( Table 1 ). Since 2016, multiple deep biomarkers of aging, identified using artificial intelligence, have been proposed. These include blood biochemistry-based clocks [ 6 ], transcriptomic and proteomic aging clocks [ 7 ], epigenetic aging clocks [ 8 ], microbiome aging clocks [ 9 ], photographic aging clocks [ 10 ], and many others. These clocks may be applied very broadly to industries that are dependent on consumer health and longevity, including the pharmaceutical and consumer industries [ 11 – 13 ].

These clocks can be used to assess the value of human data [ 14 ], perform data quality control [ 15 ], and many other applications. Substantial progress has been made in recent years in the use of artificial intelligence for drug discovery and biomarker development [ 16 , 17 ]. Additionally, neuroimaging techniques like magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and electroencephalogram (EEG) may be used in studies of potential biomarkers for healthy brain aging.

However, as discussed earlier, developing psychological aging clocks is also of great importance. Unlike the biological features used in biological aging clocks, many modifiable psychological aging features are easily interpretable by individuals and scientific specialists. Furthermore, methods and protocols developed for psychological age reversal may be also used in biological research for biomarker development and establishing causality. Here we review the history and state of the art in psychological aging approaches and provide a perspective on the future of psychophysiology and the psychology of aging.

The study of psychological aging

When it comes to psychological health, a person's subjective psychological constructs may be more valuable than previously thought. Various studies have examined a number of subjective psychological concepts to understand psychological aging, including subjective age, age identity, the aging self, attitudes toward one’s own aging, self-perceptions of aging, and satisfaction with aging [ 29 ]. Historically, a single question has been used to formalize the concept of subjective age: “What age do you feel?” [ 30 , 31 ] ( Table 2 ). The answer is known as age identity, which is calculated as the difference between subjective age and chronological age [ 32 ]. Another approach for determining subjective age involves asking participants whether they feel psychologically and physically younger, older, or the same as their chronological age [ 33 ]. Further variations on this approach include asking participants to match themselves with a specific age group, such as middle-aged or older, or with a cognitive age (i.e., feel-age, look-age, do-age, and interest-age [ 34 ]. These classifications require greater implementation in longitudinal studies. In a recent study by Veenstra and colleagues [ 35 ], an analysis of longitudinal national survey data showed that a desire to be younger than one’s chronological age may be associated with lower life satisfaction and lower physical activity in the second half of a person’s life. Thus, enhanced life enjoyment is correlated with higher age satisfaction. These data raise the question of what an individual’s ideal age is, which can be interrogated by the following prompt: “If you could choose your age, what age would you like to be?” Another measure, which could be applied in clinical practice are questions about visual perceived age. This approach defines the age of participants by the perception of digital photos or physical appearance. The Longitudinal Study of Aging Danish Twins demonstrated that perceived age estimated from photographs could be used as a predictor of mortality in the volunteers. In our review we employ the term “perceived age” as related to the subjective perception of age, as opposed to visual perception [ 36 ].