- PRO Courses Guides New Tech Help Pro Expert Videos About wikiHow Pro Upgrade Sign In

- EDIT Edit this Article

- EXPLORE Tech Help Pro About Us Random Article Quizzes Request a New Article Community Dashboard This Or That Game Popular Categories Arts and Entertainment Artwork Books Movies Computers and Electronics Computers Phone Skills Technology Hacks Health Men's Health Mental Health Women's Health Relationships Dating Love Relationship Issues Hobbies and Crafts Crafts Drawing Games Education & Communication Communication Skills Personal Development Studying Personal Care and Style Fashion Hair Care Personal Hygiene Youth Personal Care School Stuff Dating All Categories Arts and Entertainment Finance and Business Home and Garden Relationship Quizzes Cars & Other Vehicles Food and Entertaining Personal Care and Style Sports and Fitness Computers and Electronics Health Pets and Animals Travel Education & Communication Hobbies and Crafts Philosophy and Religion Work World Family Life Holidays and Traditions Relationships Youth

- Browse Articles

- Learn Something New

- Quizzes Hot

- This Or That Game

- Train Your Brain

- Explore More

- Support wikiHow

- About wikiHow

- Log in / Sign up

- Education and Communications

- College University and Postgraduate

- Academic Writing

How to Cite a Graph in a Paper

Last Updated: March 18, 2024 Fact Checked

This article was co-authored by Megan Morgan, PhD . Megan Morgan is a Graduate Program Academic Advisor in the School of Public & International Affairs at the University of Georgia. She earned her PhD in English from the University of Georgia in 2015. There are 14 references cited in this article, which can be found at the bottom of the page. This article has been fact-checked, ensuring the accuracy of any cited facts and confirming the authority of its sources. This article has been viewed 298,174 times.

Sometimes you may find it useful to include a graph from another source when writing a research paper. This is acceptable if you give credit to the original source. To do so, you generally provide a citation under the graph. The form this citation takes depends upon the citation style used in your discipline. Modern Language Association (MLA) style is used by English scholars and many humanities disciplines, while authors working in psychology, the social sciences and hard sciences often use the standards of the American Psychological Association (APA). Other humanities specialists and social scientists, including historians, use the Chicago/Turabian style, and engineering-related fields utilize the standards of the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE). Consult your instructor before writing a paper to determine which citation style is required.

Citing a Graph in MLA Style

- For example, you might refer to a graph showing tomato consumption patterns this way: "Due to the increasing popularity of salsa and ketchup, tomato consumption in the US has risen sharply in recent years (see fig. 1)."

- Figures should be numbered in the order they appear; your first graph or other illustration is "Fig. 1," your second "Fig. 2," and so on.

- Do not italicize the word “Figure” or “Fig.” or the numeral.

- For example, “Fig. 1. Rise in tomato consumption in the US, 1970-2000...”

- “Fig. 1. Rise in tomato consumption in the US, 1970-2000. Graph from John Green...”

- You also italicize the title of a website, such as this: Graph from State Fact Sheets...

- “Fig. 1. Rise in tomato consumption in the US, 1970-2000. Graph from John Green, Growing Vegetables in Your Backyard', (Hot Springs: Lake Publishers, 2002).

- If the graph came from an online source, follow the MLA guidelines for citing an online source: give the website name, publisher, date of publication, media, date of access, and pagination (if any -- if not, type “n. pag.”).

- For example, if your graph came from the USDA website, your citation would look like this: “Fig. 1. Rise in tomato consumption in the US, 1970-2000. Graph from State Fact Sheets. USDA. 1 Jan 2015. Web. 4 Feb. 2015. n. pag.”

- Fig. 1. Rise in tomato consumption in the US, 1970-2000. Graph from John Green, Growing Vegetables in Your Garden , (Hot Springs: Lake Publishers, 2002), 43. Print." [6] X Research source

- If you give the complete citation information in the caption, you do not need to also include it in your Works Cited page.

Citing a Graph in APA Format

- For example, you could write: “As seen in Figure 1, tomato consumption has risen sharply in the past three decades.”

- Figures should be numbered in the order they appear; your first graph or other illustration is Figure 1 , the second is Figure 2 , etc.

- If the graph has an existing title, give it in “sentence case.” This means you only capitalize the first letter of the first word in the sentence, as well as the first letter after a colon.

- For example: Figure 1. Rise in tomato consumption,1970-2000.

- Use sentence case for the description too.

- If the graph you’re presenting is your original work, meaning you collected all the data and compiled it yourself, you don’t need this phrase.

- For example: Figure 1. Rise in tomato consumption,1970-2000. Reprinted from...

- For example: Figure 1. Rise in tomato consumption,1970-2000. Reprinted from Growing Vegetables in Your Backyard (p. 43),

- For example: Figure 1. Rise in tomato consumption,1970-2000. Reprinted from Growing Vegetables in Your Backyard (p. 43), by J. Green, 2002, Hot Springs: Lake Publishers.

- Figure 1. Rise in tomato consumption, 1970-2000. Reprinted from Growing Vegetables in Your Backyard (p. 43), by J. Green, 2002, Hot Springs: Lake Publishers. Copyright 2002 by the American Tomato Growers' Association. Reprinted with permission. [13] X Research source

Citing a Graph Using Chicago/Turabian Standards

- For example, “Fig. 1. Rise in tomato consumption..."

- Fig. 1. Rise in tomato consumption (Graph by American Tomato Growers' Association. In Growing Vegetables in Your Backyard . John Green. Hot Springs: Lake Publishers, 2002, 43). [18] X Research source

Citing a Graph in IEEE Format

- If this marks the first time you've used this source, assign it a new number.

- If you've already used this source, refer back to the original source number.

- In our example, let's say this is the fifth source used in your paper. Your citation, then, will begin with a bracket and then "5": "[5..."

- TOMATO CONSUMPTION FIGURES [5, p. 43].

- Be sure to list complete source information in your endnotes. [21] X Research source

Community Q&A

You Might Also Like

- ↑ https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/research_and_citation/mla_style/mla_formatting_and_style_guide/mla_tables_figures_and_examples.html

- ↑ https://research.moreheadstate.edu/c.php?g=610039&p=4234946

- ↑ https://otis.libguides.com/mla_citations/images

- ↑ https://owl.english.purdue.edu/owl/resource/747/14/

- ↑ https://aut.ac.nz.libguides.com/APA7th/figures

- ↑ https://www.lib.sfu.ca/help/cite-write/citation-style-guides/apa/tables-figures

- ↑ https://guides.himmelfarb.gwu.edu/c.php?g=27779&p=170358

- ↑ https://graduate.asu.edu/sites/default/files/chicago-quick-reference.pdf

- ↑ https://guides.unitec.ac.nz/chicagoreferencing/images

- ↑ https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/research_and_citation/chicago_manual_17th_edition/cmos_formatting_and_style_guide/general_format.html

- ↑ https://libguides.dickinson.edu/c.php?g=56073&p=360111

- ↑ https://guides.lib.monash.edu/c.php?g=219786&p=6610144

- ↑ https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/research_and_citation/ieee_style/tables_figures_and_equations.html

- ↑ https://www.york.ac.uk/integrity/ieee.html

About This Article

To cite a graph in MLA style, refer to the graph in the text as Figure 1 in parentheses, and place a caption under the graph that says "Figure 1." Then, include a short description, such as the title of the graph, and list the authors first and last name, as well as the publication name, with the location, publisher, and year in parentheses. Finish the citation with the page number and resource format, which might be print or digital. If you want to cite a graph in APA, Chicago, or IEEE format, scroll down for tips from our academic reviewer. Did this summary help you? Yes No

- Send fan mail to authors

Reader Success Stories

Lilian Sumole

Nov 4, 2020

Did this article help you?

Nov 5, 2016

Savannah Caceres

Mar 25, 2017

Tiffany Taylor

Mar 6, 2017

E. Almaslam

May 15, 2017

Featured Articles

Trending Articles

Watch Articles

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Do Not Sell or Share My Info

- Not Selling Info

Get all the best how-tos!

Sign up for wikiHow's weekly email newsletter

- Databases for Keyword Searches

- Login to databases

- Guides by Librarians

- Advanced Search

- Renew a book

- Journals by Name

- Textbooks & Course Reserves

- Textbooks & Course Reserves

Statistics, Data, Graphs, and Other Factual Support: Citing a Graph with Data

- Using These Statistics

- General Statistics

- Children & Education

- Demographics

- Environment

- Health & Safety

- Human Rights

- International Statistics

- Politics & Economy

- Sports & Recreation

- Transportation

- Citing a Graph with Data

Citing a Photo, Image, Graph, or Chart with MLA

Cite a graph.

The rules for citing a graph are the same for citing a photo, illustration, map, or diagram. Place the image in the body of the essay where it is pertinent to the subject matter, and give the citation after labeling it with "Fig." and a number. Use the numbers consecutively from 1 on.

Fig. 1. Party agree graph from: McCready, Ryan. "5 Ways Writers Use Misleading Graphs To Manipulate You [INFOGRAPHIC]." Venngage, 9 Sep 2018.

Continue to Use Double Spacing

The citation should be double spaced and the only difference should be the notation "Fig." and the number which should be bold with periods after the notation and number as shown here.

Using Statistics in a Paper

- Writing and Reading Statistics A guide from University of North Carolina's Writing Center on using statistics to make your argument useful.

- Writing with statistics From the OWL Purdue Website

- << Previous: Transportation

- Last Updated: Jul 20, 2023 8:57 AM

- URL: https://shoreline.libguides.com/statistics

- AUT Library

- Library Guides

- Referencing styles and applications

APA 7th Referencing Style Guide

- Figures (graphs and images)

- Referencing & APA style

- In-text citation

- Elements of a reference

- Format & examples of a reference list

- Conferences

- Reports & grey literature

General guidelines

From a book, from an article, from a library database, from a website, citing your own work.

- Theses and dissertations

- Audio works

- Films, TV & video

- Visual works

- Computer software, games & apps

- Lecture notes & Intranet resources

- Legal resources

- Personal communications

- PowerPoint slides

- Social media

- Specific health examples

- Standards & patents

- Websites & webpages

- Footnotes and appendices

- Frequently asked questions

A figure may be a chart, a graph, a photograph, a drawing, or any other illustration or nontextual depiction. Any type of illustration or image other than a table is referred to as a figure.

Figure Components

- Number: The figure number (e.g., Figure 1 ) appears above the figure in bold (no period finishing).

- Title: The figure title appears one double-spaced line below the figure number in Italic Title Case (no period finishing).

- Image: The image portion of the figure is the chart, graph, photograph, drawing, or illustration itself.

- Legend: A figure legend, or key, if present, should be positioned within the borders of the figure and explain any symbols used in the figure image.

- Note: A note may appear below the figure to describe contents of the figure that cannot be understood from the figure title, image, and/or legend alone (e.g., definitions of abbreviations, copyright attribution). Not all figures include notes. Notes are flush left, non-italicised. If present they begin with Note. (italicised, period ending). The notes area will include reference information if not an original figure, and copyright information as required.

General rules

- In the text, refer to every figure by its number, no italics, but with a capital "F" for "Figure". For example, "As shown in Figure 1, ..."

- There are two options for the placement of figures in a paper. The first option is to place all figures on separate pages after the reference list. The second option is to embed each figure within the text.

- If you reproduce or adapt a figure from another source (e.g., an image you found on the internet), you should include a copyright attribution in the figure note, indicating the origin of the reproduced or adapted material, in addition to a reference list entry for the work. Include a permission statement (Reprinted or Adapted with permission) only if you have sought and obtained permission to reproduce or adapt material in your figure. A permission statement is not required for material in the public domain or openly licensed material. For student course work, AUT assignments and internal assessments, a permission statement is also not needed, but copyright attribution is still required.

- Important note for postgraduate students and researchers: If you wish to reproduce or adapt figures that you did not create yourself in your thesis, dissertation, exegesis, or other published work, you must obtain permission from the copyright holder/s, unless the figure is in the public domain (copyright free), or licensed for use with a Creative Commons or other open license. Works under a Creative Commons licence should be cited accordingly. See Using works created by others for more information.

Please check the APA style website for an illustration of the basic figure component & placement of figure in a text.

More information & examples from the APA Style Manual , s. 7.22-7.36, pp. 225–250

Figure reproduced in your text

Note format - for notes below the figure

In-text citation:

Reference list entry:

Referring to a figure in a book

If you refer to a figure included in a book but do not include it in your text, format the in-text citation and the reference list entry in the usual way, citing the page number where the figure appears.

Note format - for notes below the figure

Referring to a figure in an article

If you refer to a figure in an article but do not include it in your text, format the in-text citation and the reference list entry in the usual way for an article, citing the page number where the figure appears.

Note format - for notes below the figure

Reference list:

Referring to a figure on a webpage

If you refer to a figure on a webpage and do not include it in your text, format the in-text citation and the reference list entry in the usual way for a webpage,

Not every reference to an artwork needs a reference list entry. For example, if you refer to a famous painting, as below, it would not need a reference.

Most Popular

13 days ago

How To Cite A Lab Manual

How to reference a movie in an essay, how to cite scientific papers, how to cite a patent, how to cite a letter, how to cite a graph.

Did you ever notice, that most research articles you can look up include not only textual material but also some type of visualization? We are talking about graphs, diagrams, and tables. These are all the types of material that can help you strengthen or support your arguments as well as show your own findings in the paper. If you are planning on including (or already attached) one of these figures to your research, you need to know how to properly cite them. In this guide, we will give you some guidelines on how to properly cite graphs in APA and MLA.

However, before we move straight to the rules, we want to make a small note. Despite the formatting style you choose for your paper, the arrangement of your citation will largely depend on the source, and where the graph or diagram is coming from. So in both instances of APA and MLA citations, we will be looking into citation of graphs that come from online sources, and those that were found in books.

Citing a Graph: APA 7th Edition

APA 7th is a popular formatting style, especially in social sciences. And graphs are very widely used in that field so let’s quickly break down the general guidelines and move on to the examples.

General Guidelines for Citing Graphs

- Label the graph as a Figure followed by a number in bold: Figure 1

- Add a descriptive title in italic title case on the next line underneath

- The image of the graph itself should be clear, with any necessary legends or keys included within the figure to explain the symbols or colors used.

- If the graph is not original, a note should be included below the figure to provide copyright attribution, and if applicable, a statement of permission if the graph has been reproduced or adapted.

- This note should also contain the source of the graph. Here, though, there are a few differences. So, if your graphs come from: – a book, include: the title, author, year, and publisher; – an article, include: the title, author, year, journal title, volume, issue, and page number

- Additionally, in-text citations should refer to the figure by its number, and a corresponding reference list entry should be provided with full details of the source.

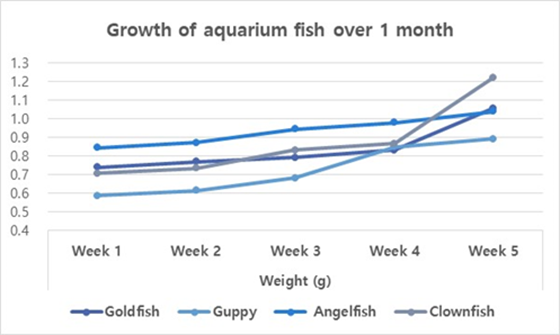

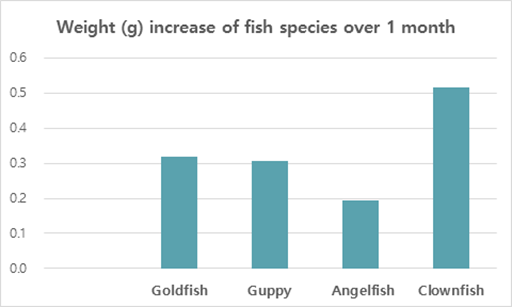

Now, as we sorted out the key rules, let’s take a look at a bright example of properly formatted APA 7th graph citations.

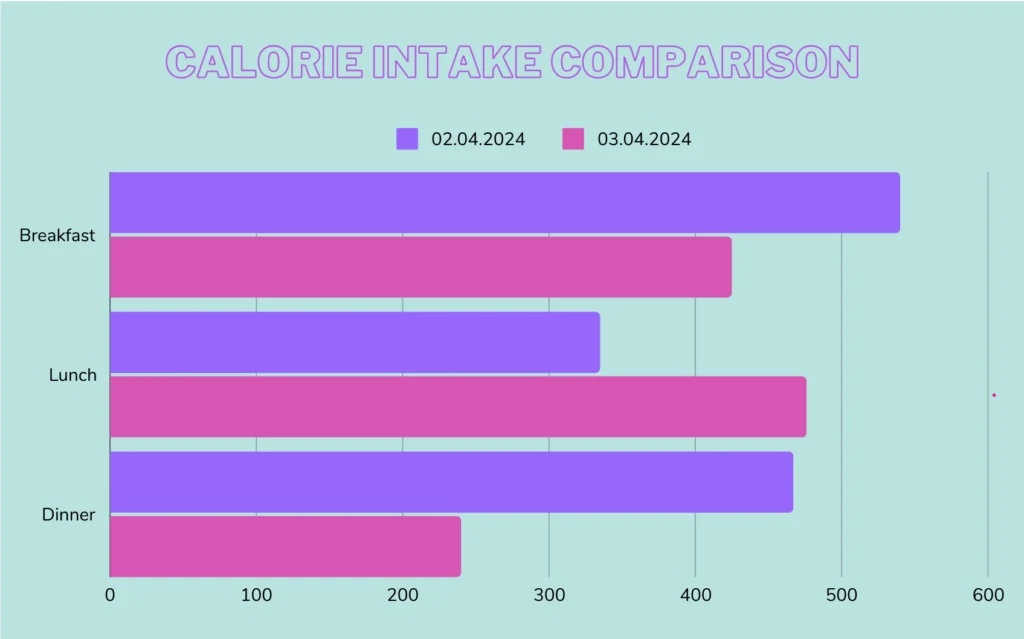

Figure 1. Calorie intake comparison by day

When mentioned in the text, this graph should be referenced the following way

“According to Figure 1, we see that…”

As to the reference list entry, you should use the structure in the picture below as an example:

It’s also important to consider the requirements for your work suggested by your professor. Sometimes, you might not be allowed to add colorful graphs, so be sure to check out those rules and whether they influence the information you present in your paper.

Let’s take a quick look at what a graph citation of a figure taken from an outside source would look like.

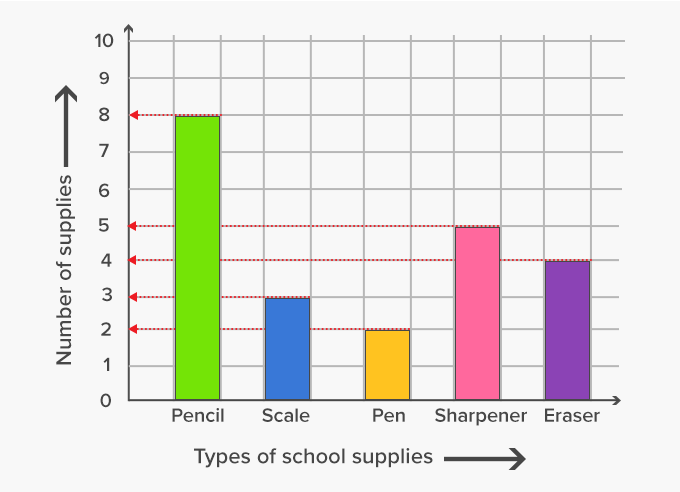

Figure 2. The usage of school supplies across different types

Reference list entry :’Graph – Definition, Types, FAQs, Practice Problems, Examples’. Retrieved from https://www.splashlearn.com/math-vocabulary/geometry/graph

How to Cite a Graph in MLA

As we mentioned earlier, it is very important to consider which source your graphs are coming from before moving on to cite them. When a graph is published in a journal article, book, or book chapter, it is common practice to cite the work and provide the page number in the in-text citation. If the graph is found online and not published in a conventional source, refer to MLA photo citation guides for appropriate formatting.

- Include an author’s last name and name as presented in the source. For two authors, reverse only the first name, followed by ‘and’ and the second name in normal order. For three or more authors, list the first name followed by et al.

- Then list the title of the graph. Here, italicize the title if it’s independent. However, if it’s a part of the bigger name, put the title in “quotes” and don’t italicize it.

- If the source presents the year of publication – state it after the title.

- List the title of the website (using UP for University Press where applicable, if there’s no name, the Press should be spelled out fully)

- and then add a URL, including the http:// or https:// prefix.

As to the in-text citations for a graph, they should include the surname of the creator and the page number in parentheses. If the creator is not mentioned, use the graph’s title or description instead. For online sources, do not list a page number at all.

Graph citation from a digital source : Mason, Clara. “Classroom media usage in young adults.” 2015. Psych Publish, psychology-now.org/graphs/social-media-stats/.

In-text citation of a graph from a book on page 208 : “Survey showed that 80% of high-school students were sleep-deprived” (Aldi, 208). If without author : “Survey showed that 80% of high-school students were sleep-deprived” (“Sleep deprivation in Students”, 208)

In-text citation of a graph found online : “It is estimated that 60% of start-ups go bankrupt in the first 10 years” (Eid).

How do you cite a graph from a website?

How do you cite a graph from a website? To cite a graph from a website in APA style, include the author’s name, the year of publication, the title of the graph in italics, the website name, and the URL.

For example: Smith, J. (2020). Trends in Renewable Energy . Energy Insights. Retrieved from http://www.energyinsights.com/trends-graph

If the graph is from an online academic journal, include the DOI instead of the URL. In MLA style, the citation would look like this: Smith, John. Trends in Renewable Energy . 2020, Energy Insights, www.energyinsights.com/trends-graph.

How do you cite a graph without an author?

If a graph does not have an author, start the citation with the title of the graph. For APA style: Trends in Renewable Energy . (2020). Energy Insights. Retrieved from http://www.energyinsights.com/trends-graph

For MLA style: Trends in Renewable Energy . Energy Insights, 2020, www.energyinsights.com/trends-graph.

How do you cite a graph from a book?

To cite a graph from a book in APA style, include the author’s name, the year of publication, the title of the graph (if available), the book title in italics, the page number, and the publisher. For example: Smith, J. (2020). Trends in Renewable Energy. In Energy Statistics Yearbook (p. 123). Energy Publishing.

In MLA style, the citation would look like this: Smith, John. “Trends in Renewable Energy.” Energy Statistics Yearbook , Energy Publishing, 2020,

Follow us on Reddit for more insights and updates.

Comments (0)

Welcome to A*Help comments!

We’re all about debate and discussion at A*Help.

We value the diverse opinions of users, so you may find points of view that you don’t agree with. And that’s cool. However, there are certain things we’re not OK with: attempts to manipulate our data in any way, for example, or the posting of discriminative, offensive, hateful, or disparaging material.

Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

More from Citation Guides

34 mins ago

How To Cite A Quote Within A Quote

6 hours ago

How to Cite Yourself

Remember Me

Is English your native language ? Yes No

What is your profession ? Student Teacher Writer Other

Forgotten Password?

Username or Email

University Libraries University of Nevada, Reno

- Skill Guides

- Subject Guides

MLA Citation Guide (MLA 9th Edition): Charts, Graphs, Images, and Tables

- Understanding Core Elements

- Formatting Appendices and Works Cited List

- Writing an Annotated Bibliography

- Academic Honesty and Citation

- In-Text Citation

- Charts, Graphs, Images, and Tables

- Class Notes and Presentations

- Encyclopedias and Dictionaries

- Generative AI

- In Digital Assignments

- Interviews and Emails

- Journal and Magazine Articles

- Newspaper Articles

- Social Media

- Special Collections

- Videos and DVDs

- When Information Is Missing

- Citation Software

Is it a Figure or a Table?

There are two types of material you can insert into your assignment: figures and tables. A figure is a photo, image, map, graph, or chart. A table is a table of information. For a visual example of each, see the figure and table to the right.

Still need help? For more information on citing figures, visit Purdue OWL .

Reproducing Figures and Tables

Reproducing happens when you copy or recreate a photo, image, chart, graph, or table that is not your original creation. If you reproduce one of these works in your assignment, you must create a note (or "caption") underneath the photo, image, chart, graph, or table to show where you found it. If you do not refer to it anywhere else in your assignment, you do not have to include the citation for this source in a Works Cited list.

Citing Information From a Photo, Image, Chart, Graph, or Table

If you refer to information from the photo, image, chart, graph, or table but do not reproduce it in your paper, create a citation both in-text and on your Works Cited list.

If the information is part of another format, for example a book, magazine article, encyclopedia, etc., cite the work it came from. For example if information came from a table in an article in National Geographic magazine, you would cite the entire magazine article.

Figure Numbers

The word figure should be abbreviated to Fig. Each figure should be assigned a figure number, starting with number 1 for the first figure used in the assignment. E.g., Fig. 1.

Images may not have a set title. If this is the case give a description of the image where you would normally put the title.

A figure refers to a chart, graph, image or photo. This is how to cite figures.

The caption for a figure begins with a description of the figure followed by the complete citation for the source the figure was found in. For example, if it was found on a website, cite the website. If it was in a magazine article, cite the magazine article.

- Label your figures starting at 1.

- Information about the figure (the caption) is placed directly below the image in your assignment.

- If the image appears in your paper the full citation appears underneath the image (as shown below) and does not need to be included in the Works Cited List. If you are referring to an image but not including it in your paper you must provide an in-text citation and include an entry in the Works Cited.

Fig. 1. Man exercising from: Green, Annie. "Yoga: Stretching Out." Sports Digest, 8 May 2006, p. 22.

Fig. 2. Annakiki skirt from: Cheung, Pauline. "Short Skirt S/S/ 15 China Womenswear Commercial Update." WGSN.

Images: More Examples

In the works cited examples below, the first one is seeing the artwork in person, the second is accessing the image from a website, the third is accessing it through a database, and the last example is using an image from a book.

Viewing Image in Person

Hopper, Edward. Nighthawks . 1942, Art Institute of Chicago.

Accessing Image from a Website

Hopper, Edward. Nighthawks . 1942. Art Institute of Chicago, www.artic.edu/aic/collections/artwork/111628 .

Note : Notice the period after the date in the example above, rather than a comma as the other examples use. This is because the date refers to the painting's original creation, rather than to its publication on the website. It is considered an "optional element."

Accessing Image from a Database

Hopper, Edward. Nighthawks . 1942, Art Institute of Chicago. Artstor , https://library.artstor.org/#/asset/AWSS35953_35953_41726475 .

Using an Image from a Book

Hopper, Edward. Nighthawks . 1942, Art Institute of Chicago. Staying Up Much Too Late: Edward Hopper's Nighthawks and the Dark Side of the American Psyche , by Gordon Theisen, Thomas Dunne Books, 2006, p. 118.

Above the table, label it beginning at Table 1, and add a description of what information is contained in the table.

The caption for a table begins with the word Source, then the complete Works Cited list citation for the source the table was found in. For example, if it was found on a website, cite the website. If it was in a journal article, cite the journal article.

Information about the table (the caption) is placed directly below the table in your assignment.

If the table is not cited in the text of your assignment, you do not need to include it in the Works Cited list.

Variables in determining victims and aggressors

Source: Mohr, Andrea. "Family Variables Associated With Peer Victimization." Swiss Journal of Psychology, vol . 65, no. 2, 2006, pp. 107-116. Psychology Collection , doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1024/1421-0185.65.2.107.

- << Previous: Books

- Next: Class Notes and Presentations >>

APA Citation Guide (7th edition) : Images, Charts, Graphs, Maps & Tables

- What Kind of Source Is This?

- Advertisements

- Books & eBooks

- Book Reviews

- Class Handouts, Presentations, and Readings

- Encyclopedias & Dictionaries

- Government Documents

- Images, Charts, Graphs, Maps & Tables

- Journal Articles

- Magazine Articles

- Newspaper Articles

- Personal Communication (Interviews, Emails)

- Social Media

- Videos & DVDs

- Paraphrasing

- Works Cited in Another Source

- No Author, No Date etc.

- Sample Paper, Reference List & Annotated Bibliography

- Powerpoint Presentations

On This Page

Image reproduced from a magazine or journal, image reproduced from a website.

Reproducing Images, Charts, Tables & Graphs

Reproducing happens when you copy or recreate an image, table, graph or chart that is not your original creation. If you reproduce one of these works in your assignment, you must create a note underneath the image, chart, table or graph to show where you found it. You do not include this information in a Reference list.

Citing Information From an Image, Chart, Table or Graph

If you refer to information from an image, chart, table or graph, but do not reproduce it in your paper, create a citation both in-text and on your Reference list.

If the information is part of another format, for example a book, magazine article, encyclopedia, etc., cite the work it came from. For example if information came from a table in an article in National Geographic magazine, you would cite the entire article.

If you are only making a passing reference to a well known image, you would not have to cite it, e.g. describing someone as having a Mona Lisa smile.

Figure Numbers

Each image you reproduce should be assigned a figure number, starting with number 1 for the first image used in the assignment.

Images may not have a set title. If this is the case give a description of the image where you would normally put the title.

Copyright Information

When reproducing images, include copyright information in the citation if it is given, including the year and the copyright holder. Copyright information on a website may often be found at the bottom of the home page.

Note: Applies to Graphs, Charts, Drawings, Maps, Tables and Photographs

Figure X . Description of the image or title of the image. From "Title of Article," by Article Author's First Initial. Second Initial. Last Name, year, day, (for a magazine) or year (for a journal), Title of Magazine or Journal, volume number, page(s). Copyright year by name of copyright holder.

Note : Information about the image is placed directly below the image in your assignment. If the image has been changed, use "Adapted from" instead of "From" before the source information.

Figure 1 . Man exercising. Adapted from "Yoga: Stretching Out," by A. N. Green, and L. O. Brown, 2006, May 8, Sports Digest, 15 , p. 22. Copyright 2006 by Sports Digest Inc.

Note: Applies to Graphs, Charts, Drawings, Tables and Photographs

Figure x. Description of the image or image title if given. Adapted from "Title of web page," by Author/Creator's First Initial. Second Initial. Last Name if given, publication date if given, Title of Website . Retrieved Month, day, year that you last viewed the website, from url. Copyright date by Name of Copyright Holder.

Note : Information about the image is placed directly below the image in your assignment. If the image has not been changed but simply reproduced use "From" instead of "Adapted from" before the source information.

Figure 2 . Table of symbols. Adapted from Case One Study Results by G. A. Black, 2006, Strong Online. https://www.strongonline/ casestudies/one.html. Copyright 2010 by G.L. Strong Ltd.

- << Previous: Government Documents

- Next: Journal Articles >>

- Last Updated: Apr 15, 2024 11:26 AM

- URL: https://columbiacollege-ca.libguides.com/apa

- How to Cite

- Language & Lit

- Rhyme & Rhythm

- The Rewrite

- Search Glass

How Do You Cite a Graph per APA Formatting?

A graph can be a useful addition to any research paper, as it provides a visual reference to the point you are trying to convey. Graphs are generally used to display data in an interesting and easy-to-read manner. As with any other piece of research, cite a graph properly per American Psychological Association rules.

Reference Page

The manner in which you cite a graph depends on the type of source. The two most common sources are books and websites. When citing a graph from a book on the reference page, use this format: Author. (Publication Date). Title of graph, chart, or table [graph]. In author or editor of work, Title of work. Place of Publication: Publisher.

If the graph was found online, cite it like this: Author. (Publication Date). Title of graph, chart, or table [graph]. Title of website. Available/Retrieved from URL. Italicize either the title of the book or website. If your graph does not have a title, replace this section with a brief description of the item, and place this inside brackets.

In-Text Citation

When citing a graph in the text, place the citation in the body of your paper directly under the graph.

For example, cite a graph found in a book as follows: Note. From Name of Book (in italics) p. number, by Author, Year, Publishing Information.

List a journal citation as: Note. From "Article name" by Author, Year, Journal Name (italics), Volume number (italics)(Issue number), p. number.

- Golden Gate University: APA Citation

- Butler University Libraries: Tables, Figures and Images

Jen has been a professional writer since 2002 in the education nonprofit industry. Her work has been featured in the New Jersey SEEDS Annual Report, as well as several Centenary College publications, including "Centenary in the News" and the "Trustee Times." In 2009, Jen earned a Master of Arts degree in leadership and public administration from Centenary College.

MLA Style: Writing & Citation

- Advertisements

- Books, eBooks & Pamphlets

- Class Notes & Presentations

- Encyclopedias & Dictionaries

- Government Documents

- Images, Charts, Graphs, Maps & Tables

Is It a Figure or a Table?

Figure (photo, image, graph, or chart) inserted into a research paper, image reproduced from google maps, table inserted into a research paper.

- Interviews and Emails (Personal Communications)

- Journal Articles

- Magazine Articles

- Newspaper Articles

- Religious Texts

- Social Media

- Videos & DVDs

- When Information Is Missing

- Works Quoted in Another Source

- MLA Writing Style

- Unknown or Multiple Authors

- Paraphrasing

- Long Quotes

- Repeated Sources

- In-Text Citation For More Than One Source

- Works Cited List & Sample Paper

- Annotated Bibliography

Need Help? Virtual Chat with a Librarian, 24/7

You Can Also:

There are two types of material you can insert into your assignment: figures and tables.

A figure is a photo, image, map, graph, or chart.

A table is a table of information.

For a visual example of each, see the figure and table to the right.

Still need help?

For more information on citing figures in MLA, see Purdue OWL .

The caption for a figure begins with a description of the figure, then the complete Works Cited list citation for the source the figure was found in. For example, if it was found on a website, cite the website. If it was in a magazine article, cite the magazine article.

Label your figures starting at 1.

Information about the figure (the caption) is placed directly below the image in your assignment.

If the image appears in your paper the full citation appears underneath the image (as shown below) and does not need to be included in the Works Cited List. If you are referring to an image but not including it in your paper you must provide an in-text citation and include an entry in the Works Cited List.

Fig. 1. Man exercising from: Green, Annie. "Yoga: Stretching Out." Sports Digest, 8 May 2006, p. 22.

Fig. 2. Annakiki skirt from: Cheung, Pauline. "Short Skirt S/S/ 15 China Womenswear Commercial Update." WGSN.

Note: This is a Seneca Libraries recommendation.

Fig. X. Description of the figure from: "City, Province." Map, Google Maps. Accessed Access Date.

Fig. 1. Map of Newnham Campus, Seneca College from: "Toronto, Ontario." Map, Google Maps. Accessed 23 Apr. 2014.

Source: Citation for source table was found in.

Above the table, label it beginning at Table 1, and add a description of what information is contained in the table.

The caption for a table begins with the word Source, then the complete Works Cited list citation for the source the table was found in. For example, if it was found on a website, cite the website. If it was in a journal article, cite the journal article.

Information about the table (the caption) is placed directly below the table in your assignment.

If the table is not cited in the text of your assignment, you do not need to include it in the Works Cited list.

Variables in determining victims and aggressors

Source: Mohr, Andrea. "Family Variables Associated With Peer Victimization." Swiss Journal of Psychology, vol . 65, no. 2, 2006, pp. 107-116, Psychology Collection , doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1024/1421-0185.65.2.107.

Reproducing Figures and Tables

Reproducing happens when you copy or recreate a photo, image, chart, graph, or table that is not your original creation. If you reproduce one of these works in your assignment, you must create a note (or "caption") underneath the photo, image, chart, graph, or table to show where you found it. If you do not refer to it anywhere else in your assignment, you do not have to include the citation for this source in a Works Cited list.

Citing Information From a Photo, Image, Chart, Graph, or Table

If you refer to information from the photo, image, chart, graph, or table but do not reproduce it in your paper, create a citation both in-text and on your Works Cited list.

If the information is part of another format, for example a book, magazine article, encyclopedia, etc., cite the work it came from. For example if information came from a table in an article in National Geographic magazine, you would cite the entire magazine article.

Figure Numbers

The word figure should be abbreviated to Fig. Each figure should be assigned a figure number, starting with number 1 for the first figure used in the assignment. E.g., Fig. 1.

Images may not have a set title. If this is the case give a description of the image where you would normally put the title.

- << Previous: Government Documents

- Next: Interviews and Emails (Personal Communications) >>

- Last Updated: May 6, 2024 1:45 PM

- URL: https://libguides.gvltec.edu/MLAcitation

In-text citation

Reference list.

- Artificial intelligence

- Audiovisual

- Books and chapters

- Government and industry publications

- Legal sources

- Theses and course materials

- Web and social media

Other sources

- Print this page

- Other styles AGLC4 APA 7th Chicago 17th (A) Notes Chicago 17th (B) Author-Date Harvard MLA 9th Vancouver

- Referencing home

(Author's surname Year)

Author's surname (Year)

This was seen in an Australian study (Couch 2017)

Couch (2017) suggests that . . .

- List the authors names in the same order as they appear in the article.

- Go to Getting started > In-text citation to view other examples such as multiple authors.

Use tables for exact values and information that is too detailed for the text. Use a table only if there isn't a simpler way to present your content such as a list or a diagram.

Tables should include a caption title row and column headings, information (exact values)

In-text table section

Use Table 1, Table 2 etc to caption tables and refer to them in the text.

See the Style Manual section on tables .

Author A or Name of Agency (Year) Title of data set [data set], Name of Website, accessed DD Month YYYY. URL

National Native Title Tribunal (2014) Native Title determination outcomes [data set], accessed 4 January 2020. data.gov.au/data/dataset/native-title-determination-outcomes

- If no date, use n.d.

- If name of website is the same as author, do not include the name of the website.

Personal communication and confidential unpublished material

A Author, personal communication, Day Month Year.

A Author, Type of Confidential Unpublished Material, Day Month Year.

M Smith (personal communication, 8 February 2020) wrote . . .

The radiologist's findings were further confirmed (P Alan, radiology report, 6 March 2021) . . .

- Don’t include an entry in the reference list.

- Personal communication may include materials such as emails from unarchived sources, private memos or unrecorded interview conversations.

- Confidential material may include medical charts, patient health records and other internal reports containing private information.

- Permission from the source is necessary before paraphrasing or citing from a confidential document.

- << Previous: Web and social media

- Next: Get help >>

- Last Updated: May 9, 2024 10:07 AM

- URL: https://guides.lib.monash.edu/harvard

Citing Sources: Images, Charts, Graphs, Maps & Tables

- APA Citation Style - 7th ed.

- Advertisements

- Books, eBooks & Pamphlets

- Class Notes, Class Lectures and Presentations

- Encyclopedias & Dictionaries

- Government Documents

- Images, Charts, Graphs & Tables

- Indigenous Knowledge

- Interviews and Emails

- Journal Articles

- Legal Resources

- Magazine Articles

- Newspaper Articles

- Social Media

- Videos, Films and TV

- When Information Is Missing

- Works Quoted in Another Source

- Citing ChatGPT

- APA for Fashion and Jewelry

- Citing for Architecture / Construction

- MLA Citation Style

- Business Reports from Library Databases

- Class Notes & Presentations

- Creative Commons Licensed Works

- Images, Charts, Graphs, Maps & Tables

- Interviews and Emails (Personal Communications)

- Videos, Films, and TV

- ChatGPT and AI tools

- Chicago Style

- Vancouver Style

- APA Inclusive Language Guidelines This link opens in a new window

- APA Citation for Business

How do I cite...

- Figure (Photo, Image, Graph, or Chart)

Is It a Figure or a Table?

There are two types of material you can insert into your assignment: figures and tables.

A figure is a photo, image, map, graph, or chart.

A table is a table of information.

For a visual example of each, see the figure and table to the right.

Still need help?

For more information on citing figures in MLA, see Purdue OWL .

Reproducing Figures and Tables

Reproducing happens when you copy or recreate a photo, image, chart, graph, or table that is not your original creation. If you reproduce one of these works in your assignment, you must create a note (or "caption") underneath the photo, image, chart, graph, or table to show where you found it. If you do not refer to it anywhere else in your assignment, you do not have to include the citation for this source in a Works Cited list.

Citing Information From a Photo, Image, Chart, Graph, or Table

If you refer to information from the photo, image, chart, graph, or table but do not reproduce it in your paper, create a citation both in-text and on your Works Cited list.

If the information is part of another format, for example a book, magazine article, encyclopedia, etc., cite the work it came from. For example if information came from a table in an article in National Geographic magazine, you would cite the entire magazine article.

Figure Numbers

The word figure should be abbreviated to Fig. Each figure should be assigned a figure number, starting with number 1 for the first figure used in the assignment. E.g., Fig. 1.

Images may not have a set title. If this is the case give a description of the image where you would normally put the title.

Figure (Photo, Image, Graph, or Chart) Inserted Into a Paper

Label your figures starting at 1.

Information about the figure (the caption) is placed directly below the image in your assignment.

If the image appears in your paper the full citation appears underneath the image (as shown below) and does not need to be included in the Works Cited List. If you are referring to an image but not including it in your paper you must provide an in-text citation and include an entry in the Works Cited List.

Fig. 1. Annie Green. "Yoga: Stretching Out." Sports Digest, 8 May 2006, p. 22.

Fig. 2. Pauline Cheung. "Short Skirt S/S/ 15 China Womenswear Commercial Update." WGSN. 4 June 2016, p. 2.

Table Inserted Into a Research Paper

Source: Citation for source table was found in.

Above the table, label it beginning at Table 1, and add a description of what information is contained in the table.

The caption for a table begins with the Adapted from, then the complete Works Cited list citation for the source the table was found in. For example, if it was found on a website, cite the website. If it was in a journal article, cite the journal article.

Information about the table (the caption) is placed directly below the table in your assignment.

If the table is not cited in the text of your assignment, you do not need to include it in the Works Cited list.

Variables in determining victims and aggressors

Adapted From: Mohr, Andrea. "Family Variables Associated With Peer Victimization." Swiss Journal of Psychology, vol . 65, no. 2, 2006, pp. 107-116, Psychology Collection , doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1024/1421-0185.65.2.107.

- << Previous: Government Documents

- Next: Interviews and Emails (Personal Communications) >>

- Last Updated: Apr 2, 2024 12:47 PM

- URL: https://researchguides.georgebrown.ca/citingsources

Citation guides

All you need to know about citations

How to cite a graph in MLA

It is common practice to cite the work the graph has been published in and provide the page number in the in-text citation. In case the graph has not been published in a journal article, book, or book chapter, but is rather found online take a look at our MLA photo citation guides below.

MLA citation format for a graph

- Google Docs

To cite a graph in a reference entry in MLA style 8th edition include the following elements:

- Author: Give the last name and name as presented in the source (e. g. Watson, John). For two authors, reverse only the first name, followed by ‘and’ and the second name in normal order (e. g. Watson, John, and John Watson). For three or more authors, list the first name followed by et al. (e. g. Watson, John, et al.)

- Title of the graph: Titles are italicized when independent. If part of a larger source add quotation marks and do not italize.

- Year of publication: Give the year of publication as presented in the source.

- Title of website: If the name of an academic press contains the words University and Press, use UP e.g. Oxford UP instead of Oxford University Press. If the word "University" doesn't appear, spell out the Press e.g. MIT Press.

- URL: Copy URL in full from your browser, include http:// or https:// and do not list URLs created by shortening services.

Here is the basic format for a reference list entry of a graph in MLA style 8th edition:

Author . Title of the graph . Year of publication . Title of website , URL .

- Author(s) of the book: Give the last name and name as presented in the source (e. g. Watson, John). For two authors, reverse only the first name, followed by ‘and’ and the second name in normal order (e. g. Watson, John, and John Watson). For three or more authors, list the first name followed by et al. (e. g. Watson, John, et al.)

- Title of the book:

- Publisher: If the name of an academic press contains the words University and Press, use UP e.g. Oxford UP instead of Oxford University Press. If the word "University" doesn't appear, spell out the Press e.g. MIT Press.

Author(s) of the book . Title of the book Publisher , Year of publication .

Take a look at our works cited examples that demonstrate the MLA style guidelines in action:

Graph citation from a digital source

Masoud, Carla . Social media usage in young adults . 2017 . Psych Publish , psychology-now.org/graphs/social-media-stats/ .

Graph citation from a book

Devito, Roberto . Cheese consumption in the USA . Chicago Publishing , 2021 .

How to do an in-text citation for a graph in MLA

When citing a graph in-text using the MLA style, you'll use the surname of the creator followed by the page number in parentheses.

In practice, you can expect your graph's in-text citation to be in this format (Author, Page Number) .

If you were to cite a graph from a book, the graph should be cited in-text using the creator's name, along with the corresponding year of publication.

Citation of a graph from a book on page 193

Survey showed that 80% of high-school students were sleep-deprived (Eid, 193) .

If the creator is not mentioned, you can place the graph's title or description instead.

Citation of a graph from a source with no creator

Zinc was found to be one of the most prevalent heavy metals in the Nile River ("Levels of heavy metals in the Nile River", 198) .

If the graph is found online, do not list a page number.

Citation of a graph found online

It is estimated that 60% of start-ups go bankrupt in the first 10 years (Eid) .

This citation style guide is based on the MLA Handbook (9 th edition).

More useful guides

- Citing Images in MLA 8th Edition

- MLA Style Center Citing online images

More great BibGuru guides

- MLA: how to cite a book chapter

- AMA: how to cite a software manual

- MLA: how to cite a PhD thesis

Automatic citations in seconds

Citation generators

Alternative to.

- NoodleTools

- Getting started

From our blog

- 📚 How to write a book report

- 📝 APA Running Head

- 📑 How to study for a test

Advertisement

- Previous Article

- Next Article

1. INTRODUCTION

2. the citation graph: concepts and limits, 3. extending the citation graph, 4. data in the citation graph, 5. discussion, 6. related work, 7. conclusions and future work, acknowledgments, author contributions, competing interests, funding information, data availability, data citation and the citation graph.

- Cite Icon Cite

- Open the PDF for in another window

- Permissions

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

- Peer Review

- Search Site

Peter Buneman , Dennis Dosso , Matteo Lissandrini , Gianmaria Silvello; Data citation and the citation graph. Quantitative Science Studies 2022; 2 (4): 1399–1422. doi: https://doi.org/10.1162/qss_a_00166

Download citation file:

- Ris (Zotero)

- Reference Manager

The citation graph is a computational artifact that is widely used to represent the domain of published literature. It represents connections between published works, such as citations and authorship. Among other things, the graph supports the computation of bibliometric measures such as h -indexes and impact factors. There is now an increasing demand that we should treat the publication of data in the same way that we treat conventional publications. In particular, we should cite data for the same reasons that we cite other publications. In this paper we discuss what is needed for the citation graph to represent data citation. We identify two challenges: to model the evolution of credit appropriately (through references) over time and to model data citation not only to a data set treated as a single object but also to parts of it. We describe an extension of the current citation graph model that addresses these challenges. It is built on two central concepts: citable units and reference subsumption. We discuss how this extension would enable data citation to be represented within the citation graph and how it allows for improvements in current practices for bibliometric computations, both for scientific publications and for data.

1.1. Citations and the Citation Graph

Citation is essential to the creation and propagation of knowledge and is a well-understood part of scholarship and scientific publishing. Citations allow us to identify the cited material, retrieve it, give credit to its creator, date it, and provide partial knowledge of its subject and quality.

Exploration of the graph to find publications of interest.

Tracking of authorship of papers: Citing and following citations is one way to attribute credit to authors and to keep up to date with the work of others.

Dissemination of research findings: The exploration of citations and cited authors enables the dispersed communities of researchers to share their findings and engage in discussions.

Computation of bibliometrics for the analysis of one researcher, venue, or publication impact in particular fields. The citation graph is the basis for nearly all the currently used bibliometrics, such as impact factor and h-index .

Throughout this paper, we refer to an idealized “citation graph” as though it were a real and unique digital artifact that represents papers and the citations between them. Of course, it is not unique: Various organizations have distinct implementations of it. Among these, we count: Google Scholar, the Microsoft Academic Graph (MAG) 1 , the Open Academic Graph (OAG) ( Tang et al., 2008 ), Semantic Scholar (SS) 2 , AMiner (AM) 3 , and PubMed 4 (this is more a linked collection of documents than a full-fledged citation graph), Scopus 5 , and the Web of Science 6 . These graphs differ in many aspects, such as their coverage, their being open- or closed-access, and their schema; but in all of these, the basic structure is a directed graph, in which the vertices represent publications and the edges represent citations from one publication to another ( Price, 1965 ).

Most of the information about papers is contained in annotations of the nodes. The edges are generally typed but not annotated (an exception is MAG, which carries context , as we discuss later). Although in early models, nodes only represented papers and the only edges were “cites” edges, recently, citation graphs have been extended with richer information ( Peroni & Shotton, 2020 ). These extensions may carry author nodes with a “wrote” edge to papers, journal/conference nodes with a “part of” edge from papers, and subject nodes with the corresponding edges. Although representations differ, the purpose is similar: to provide the services described above.

1.2. The Need for Data Citation

Scientific publications increasingly rely on curated databases, which are numerous, “populated and updated with a great deal of human effort” ( Buneman, Cheney et al., 2008 ), and at the core of current scientific research 7 . In this context, references to data are starting to be placed alongside traditional references. Hence, there has been a strong demand ( FORCE-11, 2014 ; CODATA-ICSTI Task Group on Data Citation Standards and Practices, 2013 ) to give databases the same scholarly status as traditional scientific works and to define a shared methodology to cite data. Scientific publishers (e.g., Elsevier, PLoS, Springer, Nature) have taken up data citation by instituting policies to include data citations in the reference lists.

The open research culture ( Nosek, Alter et al., 2015 ) is based on methods and tools to share, discover, and access experimental data. Moreover papers, journals, and articles should provide access to all the data that they use ( Cousijn, Feeney et al., 2019 ). Researchers and practitioners (e.g., journalists and data scientists) who make use of electronic data should be able to cite the relevant data as they would cite a document from which they had extracted information ( Cousijn, Kenall et al., 2017 ; Nature Physics Editorial, 2016 ). As we shall see, the citation graphs can become a fundamental tool in the pursuit of the goal of accessibility and networking between papers and data.

We also observe that data occupy a crucial role today in research, emerging as a driving instrument in science ( Candela, Castelli et al., 2015 ). Data citations should be given the same scholarly status as traditional citations and contribute to bibliometrics indicators ( Belter, 2014 ; Peters, Kraker et al., 2016 ). Principles such as Findability, Accessibility, Interoperability, and Reusability (FAIR) ( Wilkinson, Dumontier et al., 2016 ) require data to be easily findable and accessible, qualities that are more readily available once data can be appropriately cited. In this sense, we can say that the FAIR principles encourage the adoption of data citation.

The reasons given for data citation are the same those given for a conventional citation ( CODATA-ICSTI Task Group on Data Citation Standards and Practices, 2013 ): recognition of the source (e.g., a title); credit for the author, curator, or agent; establishment of its currency (when it was created); where it was located; and how it was extracted. The last three of these fall under the general heading of provenance and are important when one wants to reproduce some analysis on the data or establish the trustworthiness of a claim.

Data sets and databases are usually more complex and varied than textual documents, and they introduce significant challenges for citation ( Silvello, 2018 ). Text publications have a fixed form, do not change over time, are interpretable as independent units, share a standard format and representation model, and are composed of predetermined, albeit domain-dependent, sets of elements that are considered as citable (e.g., the whole paper or book or a chapter). Scientific databases are structured according to diverse data models and accessed with a variety of query languages. What can be cited may range from a single datum to data subsets or aggregations specified by the person or agent that extracts the relevant data, and deciding a priori what can and cannot be cited is rarely feasible. Data citation introduces multiple citation types, besides the classical papers citing papers. These are papers citing data, data citing papers, and data citing data.

1.3. Data Citation in the Citation Graph

Our purpose in this paper is to discuss whether, in its current form, the current model of the citation graph can properly accommodate data citation. We claim that, despite all the features and modifications that have been added to various implementations of the citation graph, at least two significant features are generally missing or poorly represented. These shortcomings already limit what we can represent with existing implementations, and we argue that they make impossible the proper representation of data citations.

The first shortcoming concerns the assignment of credit when a referenced scientific work is corrected or augmented with another version. A typical example case is that of a preprint paper that gets cited before its peer-reviewed version is published. It is common for the authors to prefer that the preprint citations are merged with those of the peer-reviewed version. Something similar happens also when an updated version of a data set is published.

In the case of data, we need to consider that a database may be composed of multiple independently citable parts (e.g., a single record, a table, a view). Every single citable part can evolve and change over time and obtain citations (also views or downloads, when monitoring other scientometrics signals) at a different point in time. Therefore, it can be necessary to aggregate these statistics over all the versions of the same part to measure its impact and that of the database. The MAG and S2ORC databases have also an explicit notion of multiple versions of a paper, for example preprints and final published versions. It is however uncommon to “move” citations from one version to another, following some criteria or algorithm to correctly allocate citations. Yet, aggregating citation to a single version of a scientific work would have, among other things, the desirable effect of allowing proper evaluation of the impact of the work.

The second feature is the representation of context of a citation. Context is required for various reasons. It is typically used to describe the relevant part (e.g., page number) of a cited document. It may also carry, as in MAG, the surrounding text within the citing document helping to understand the reason for the citation; for example, a simple mention, a confutation, or a validation, such as those described in the OpenCitations ontology ( Daquino, Peroni et al., 2020 ). In the case of data citations, the context can contain the query identifying the cited data, expressed in different format (e.g., a URL, a filename, a SQL or SPARQL query, etc.). Despite a great deal of attention dedicated to the citation context—see, for instance, the Citation Context Analysis (CCA) discussed as early as the 1980s ( Freeman, Ding, & Milojevic, 2013 )—there is no systematic approach to representing it within citation graphs.

In fact, none of the largest citation-based systems, such as Scopus, MAG, and Google Scholar, properly take into account scientific databases as objects for use in the research literature. Google Data Search 8 allows us to search for indexed data sets, but it does not keep track of the citations to data or other types of statistics, such as clicks or downloads. Web of Science is one notable exception because it models data citations, even though only at the database level, via the Data Citation Index (DCI), now maintained by Clarivate Analytics ( Force, Robinson et al., 2016 ). Note that DCI is not publicly available and the data sets are indexed after a validation process.

Another effort is the Scholix framework ( Burton, Koers et al., 2017 ), which can be regarded as a set of guidelines and lightweight models that can be quickly adopted and expanded to facilitate interoperability among link providers. Finally, an example of an initiative that includes data and databases among the entities of the graph is the OpenAIRE Research Graph Data Model ( Manghi, Bardi et al., 2019 ), which leverages the OpenAIRE services to populate a research graph whose nodes include scientific results, organizations, funding agencies, communities, and data sources.

The conventional approach is to treat a data set as a single entity, in the same way, one would treat a scientific publication. However, this is far from ideal as typically only a small part of the data set or database is cited, and the authorship—the people who have contributed to the database—can vary widely with the part of the database being cited ( Buneman, Davidson, & Frew, 2016 ).

In this paper, we discuss the extension of the current model to enable the proper inclusion of data citations in the citation graph; and we discuss the evolution of a database: What happens to citations when new versions of the database appear? For the versioning issue, we describe a relation between scientific works (either papers or data) called subsumption . Through different policies, this relationship models effectively how credit should be transferred through time when updated versions of data appear in the graph. Finally, we discuss how to introduce data in the citation graph, considering the most common data citation strategies currently used in the world of research. In particular, we take inspiration from one of the solutions proposed by the Research Data Alliance ( RDA ) 9 . The RDA is a community-driven initiative launched in 2013 by different commissions. One of its working groups, the “Working Group on Data Citation: Making Dynamic Data Citable” (WGDC), has as one of its goals the identification and citation of arbitrary views of data. As a potential solution, the WGDC recommends an identification method based on PIDs assigned to queries.

The focus of this work is on data citation; but to ease the comprehension of the paper, we first discuss the limitations of the citation graph and the possible extensions we propose by focusing on textual documents, and then we extend the reasoning to data citation.

The paper is organized as follows: Section 2 describes some preliminary concepts and the limits of the citation graphs; in Section 3 we discuss the proposed solutions for the first three issues; Section 4 presents the proposed solution for the introduction of data in the citation graph; Section 5 sums up our main proposals and discusses possible lines of research and development; Section 6 describes the related work; finally, Section 7 presents conclusions and future work.

2.1. Core Concepts

2.1.1. citable unit.

By citable unit (CU), we mean a published entity—be it a paper, a chapter, or portion of data—which presents all the qualities necessary to be considered as a “citable work.” The characterization of a CU that we use, given in Wilke (2015) , requires that: it must be uniquely and unambiguously identifiable and citable; it must be available in perpetuity and in unchanged form; it must be accessible ; and it must be self-contained and complete . Self-contained and complete means that whatever new contribution is contained inside the piece of work, that contribution needs to be fully and clearly explained. This is not always the case for certain publications. Consider the slides of a scientific presentation. As they are used merely as a support for the oral presentation, they often cannot be fully understood without the corresponding talk. Also, the combination slides/registration of the talk may be incomplete, as many presenters tend to skip technical details during their presentations, referring to the complete published work.

Although some of these requirements are subjective, and not straightforward in databases, they still provide a workable starting point. The requirement that is most problematic for databases is that the citable unit must be unchanged . Databases evolve rapidly, and creating a citable unit for each version may be counterproductive. This is something we address in Section 4.2. Generally, what constitutes a citable unit is decided by convention. We should also note that some citable units comprise other citable units. The proceedings of a conference may be cited as may be a book on a topic whose chapters are written by different people and may also be individually cited. There is thus a “part-of” relationship between CUs that we discuss later.

In ( Daquino et al., 2020 ) a similar concept, bibliographic resource , is defined as a resource that cites and can be cited by other resources.

2.1.2. Reference

At the end of this paper, there is a list of references. Traditionally, a reference is a pointer to, and a brief description of, another publication in the literature. It is a short text composed of fields such as title, authors, year, venue, and others, that enables us to identify and find the entity (i.e., a paper, a book, or a survey) being referenced. Depending on aspects of the citing CU’s nature, like its field of research, the publication venue, or even language, different attributes of the reference may vary such as the format or the fields composing the reference. In physics, for example, titles are often omitted.

The important point is that, apart from the stylistic rendition of the reference, its contents are determined by the cited CU; hence, to within stylistic variations, the reference to a CU will be the same in any paper. In this paper, the reference determines the existence of a directed edge between two CUs: the citing and the cited one.

2.1.3. Citation

There is no universal agreement on the distinction between reference and citation , and the two terms are often used interchangeably ( Altman & Crosas, 2014 ; Daquino et al., 2020 ; Osareh, 1996 ; Price & Richardson, 2008 ).

One distinction proposed in Gilbert and Woolgar (1974) is that “reference” refers to the works mentioned in the reference section or bibliography of a paper. A reference may be mentioned once or many times in an article. Each of these mentions is considered a citation.

The distinction is crucial to our understanding of the citation graph. If we look at what goes in the body of a paper, we may find, for example, “Austen, J. (2004). pp 101–104.” We note that this textual artifact contains two parts. The first one is “Austen, J. (2004),” which we call a reference pointer . A reference pointer is, in general, a textual means that is used to denote a single bibliographic reference in the reference section when mentioned in the body of a paper. The second part of the citation is composed of some additional information, in this case “pp 101–104,” which may help the reader locate specific information within the cited paper. Note that the same reference pointer can occur several times in a paper and may have differing additional information, such as “pp 10–25” and “pp 110–120.”

Therefore, we can say that a citation is composed of the combination of the reference pointer with the (optional) information added to it in the paper’s body. The optional information in the paper’s body may be referred to as a form of context for the citation. This implies that there is a many-one relationship between citations and references, a fact that is supported by some discussions on the topic, for example “… the second necessary part of the citation or reference is the list of full references, which provides complete, formatted detail about the source, so that anyone reading the article can find it and verify it.” ( Wikipedia, 2021 ).

2.1.4. Reference annotation

We shall call this extra information, such as “pp 101–104,” reference annotation . In this paper, the reference annotation consists of all the information added to a reference pointer to qualify how it is used. This information is not part of the reference and can change depending on how that particular resource is used.

The Citation Typing Ontology ( Shotton, 2010 ) is replete with examples of other kinds of annotations such as “refutes,” or “ridicules,” which are clearly about the relationship between the citing and cited documents. In the Microsoft Academic Graph ( Sinha, Shen et al., 2015 ), the context —the text surrounding a citation in the source document—may be recorded as another form of annotation. The OpenCitations ontology ( Daquino et al., 2020 ) contains a class called annotation 10 attached to the in-text citation and to a reference which has a similar role. Here, we do not need to distinguish between the context of a reference pointer and its reference annotation: For our purposes these two concepts are the same, however it may be that certain applications will require some finer distinctions.

These definitions differ slightly from those in Daquino, Peroni, and Shotton (2018) and Daquino et al. (2020) , where a reference (called a bibliographic reference) and a reference pointer are manifestations of a citation. Moreover, in our example, the part “pp. 101–104” is a reference annotation, whereas in Daquino et al. (2020) it is a specialization of the citation. We do not specifically model the concept of specialization, as it can be inferred from the content of the reference annotation. Also, in Daquino et al. (2020) the pointer may include additional information, but the citation does not.

Summing up, we consider a reference annotation as a “box” that can contain information derived from the context of a reference pointer.

Generally speaking, the Citation Context Analysis (CCA), whose basis was first developed in the early 1980s, is the syntactic and semantic analysis of citation content, used to analyze the context of research behavior ( Freeman et al., 2013 ). CCA has been used as a promising addition to traditional quantitative citation analysis methods. One of the main aspects of CCA is that it incorporates qualitative factors, such as how one cites. In Daquino et al. (2020) this idea is captured by the concept of citation function , which is the function or purpose of the citation (e.g., to cite as background, extend, agree with the cited entity) to which each in-text reference pointer relates. In our proposal, this qualitative factor, or citation function, can be located in the reference annotation, and it could be inferred from the context of the reference pointer.

Even in a citation graph that represents conventional citations it is necessary to be able to attach information to a reference to create proper citations. Yet, in some citation graph implementations, this is impossible, because the reference relationship is represented as a directed but unannotated edge. As noted above, an exception is the Microsoft Academic Graph, which contains two kinds of edges between publications: unannotated edges and edges annotated with context. The reason for this omission may be the difficulty of collecting the relevant information; it may also be that it is not needed in the computation of most bibliometrics.

2.1.5. Part-of

The part-of relationship exists between two citable units in the graph; it describes the situation where one citation unit is somehow “contained” in the other. This is the case of papers published in an instance of a venue (e.g., the 2020 version of the ACM SIGMOD), and these issues being part of the venues themselves (e.g., ACM SIGMOD). This information is present for example in databases such as MAG and AMiner.

In the case of data, the part-of relationship is particularly important. Many databases and data sets have a hierarchical structure and may be cited at different levels of detail.

2.1.6. Database categories and citation

Static databases , which are used to support claims in a publication. These are typically “one-off” results of a set of experiments. For these databases, systems such as Mendeley 11 store data alongside the publication, so that a citation to the publication also serves as a citation to the data. Data journals ( Candela et al., 2015 ) (i.e., journals publishing papers describing data sets) are also employed as proxies to cite static data sets.

Evolving databases of source data such as weather data ( Philipp, Bartholy et al., 2010 ) or satellite image data ( Shanableh, Al-Ruzouq et al., 2019 ) that are collected for a wide range of purposes. Zenodo 12 , like Mendeley, stores data together with its representative publication. However, a publication about a data set and the data set itself can also have separate and unrelated DOIs. In this case the citation to the publication and to the database are distinguished. Moreover, it allows multiple versions of the same database to be deposited, with new DOIs for each one, thus keeping track of usage statistics like the number of downloads and views on each version. A citation to the database, or even to a document that describes the whole database, is generally regarded as inadequate. Usually, only a portion is used; hence, one needs to know the part (the sensor, the location of the image, or the time range) from which the data was extracted.

Finally, we have curated databases . These have largely replaced conventional biological reference works ( Buneman et al., 2008 ), and like the works they replace, involve substantial human effort. One advantage is that they are readily accessible and easy to search. Moreover, there are few limits on their size and complexity, and they can evolve rapidly with the subject matter. For these, the citation is a complex issue but it is just as crucial for curated databases as it is for the reference works that they replace.

The distinction between these three categories is not sharp, and there are many examples that lie in the overlap. For example, most source data databases involve a degree of curation.

2.2. Existing Limitations of the Citation Graph

Although implementations of the citation graph differ, the basic model consists of a directed graph 𝒢 = ( V , E ), where V is the set of papers and E ⊆ V × V is the set of directed edges corresponding to the citations among them: An edge 〈 p 1 , p 2 〉 connects the papers p 1 and p 2 , if p 1 cites p 2 . The following limitations of this simple model are obstacles to the representation of data citation, but can already be seen in conventional citations to papers.

2.2.1. Lack of context