- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Montgomery Bus Boycott

By: History.com Editors

Updated: January 10, 2023 | Original: February 3, 2010

The Montgomery Bus Boycott was a civil rights protest during which African Americans refused to ride city buses in Montgomery, Alabama, to protest segregated seating. The boycott took place from December 5, 1955, to December 20, 1956, and is regarded as the first large-scale U.S. demonstration against segregation. Four days before the boycott began, Rosa Parks , an African American woman, was arrested and fined for refusing to yield her bus seat to a white man. The U.S. Supreme Court ultimately ordered Montgomery to integrate its bus system, and one of the leaders of the boycott, a young pastor named Martin Luther King Jr. , emerged as a prominent leader of the American civil rights movement .

Rosa Parks' Bus

In 1955, African Americans were still required by a Montgomery, Alabama , city ordinance to sit in the back half of city buses and to yield their seats to white riders if the front half of the bus, reserved for whites, was full.

But on December 1, 1955, African American seamstress Rosa Parks was commuting home on Montgomery’s Cleveland Avenue bus from her job at a local department store. She was seated in the front row of the “colored section.” When the white seats filled, the driver, J. Fred Blake, asked Parks and three others to vacate their seats. The other Black riders complied, but Parks refused.

She was arrested and fined $10, plus $4 in court fees. This was not Parks’ first encounter with Blake. In 1943, she had paid her fare at the front of a bus he was driving, then exited so she could re-enter through the back door, as required. Blake pulled away before she could re-board the bus.

Did you know? Nine months before Rosa Parks' arrest for refusing to give up her bus seat, 15-year-old Claudette Colvin was arrested in Montgomery for the same act. The city's Black leaders prepared to protest, until it was discovered Colvin was pregnant and deemed an inappropriate symbol for their cause.

Although Parks has sometimes been depicted as a woman with no history of civil rights activism at the time of her arrest, she and her husband Raymond were, in fact, active in the local chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People ( NAACP ), and Parks served as its secretary.

Upon her arrest, Parks called E.D. Nixon, a prominent Black leader, who bailed her out of jail and determined she would be an upstanding and sympathetic plaintiff in a legal challenge of the segregation ordinance. African American leaders decided to attack the ordinance using other tactics as well.

The Women’s Political Council (WPC), a group of Black women working for civil rights, began circulating flyers calling for a boycott of the bus system on December 5, the day Parks would be tried in municipal court. The boycott was organized by WPC President Jo Ann Robinson.

Montgomery’s African Americans Mobilize

As news of the boycott spread, African American leaders across Montgomery (Alabama’s capital city) began lending their support. Black ministers announced the boycott in church on Sunday, December 4, and the Montgomery Advertiser , a general-interest newspaper, published a front-page article on the planned action.

Approximately 40,000 Black bus riders—the majority of the city’s bus riders—boycotted the system the next day, December 5. That afternoon, Black leaders met to form the Montgomery Improvement Association (MIA). The group elected Martin Luther King Jr. , the 26-year-old-pastor of Montgomery’s Dexter Avenue Baptist Church , as its president, and decided to continue the boycott until the city met its demands.

Initially, the demands did not include changing the segregation laws; rather, the group demanded courtesy, the hiring of Black drivers, and a first-come, first-seated policy, with whites entering and filling seats from the front and African Americans from the rear.

Ultimately, however, a group of five Montgomery women, represented by attorney Fred D. Gray and the NAACP, sued the city in U.S. District Court, seeking to have the busing segregation laws totally invalidated.

Although African Americans represented at least 75 percent of Montgomery’s bus ridership, the city resisted complying with the protester’s demands. To ensure the boycott could be sustained, Black leaders organized carpools, and the city’s African American taxi drivers charged only 10 cents—the same price as bus fare—for African American riders.

Many Black residents chose simply to walk to work or other destinations. Black leaders organized regular mass meetings to keep African American residents mobilized around the boycott.

Integration at Last

On June 5, 1956, a Montgomery federal court ruled that any law requiring racially segregated seating on buses violated the 14th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution . That amendment, adopted in 1868 following the U.S. Civil War , guarantees all citizens—regardless of race—equal rights and equal protection under state and federal laws.

The city appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court , which upheld the lower court’s decision on December 20, 1956. Montgomery’s buses were integrated on December 21, 1956, and the boycott ended. It had lasted 381 days.

Bus Boycott Meets With Violence

Integration, however, met with significant resistance and even violence. While the buses themselves were integrated, Montgomery maintained segregated bus stops. Snipers began firing into buses, and one shooter shattered both legs of a pregnant African American passenger.

In January 1957, four Black churches and the homes of prominent Black leaders were bombed; a bomb at King’s house was defused. On January 30, 1957, the Montgomery police arrested seven bombers; all were members of the Ku Klux Klan , a white supremacist group. The arrests largely brought an end to the busing-related violence.

Boycott Puts Martin Luther King Jr. in Spotlight

The Montgomery Bus Boycott was significant on several fronts. First, it is widely regarded as the earliest mass protest on behalf of civil rights in the United States, setting the stage for additional large-scale actions outside the court system to bring about fair treatment for African Americans.

Second, in his leadership of the MIA, Martin Luther King Jr. emerged as a prominent national leader of the civil rights movement while also solidifying his commitment to nonviolent resistance. King’s approach remained a hallmark of the civil rights movement throughout the 1960s.

Shortly after the boycott’s end, he helped found the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), a highly influential civil rights organization that worked to end segregation throughout the South. The SCLC was instrumental in the civil rights campaign in Birmingham, Alabama, in the spring of 1963, and the March on Washington in August of that same year, during which King delivered his famous “I Have a Dream” speech .

The boycott also brought national and international attention to the civil rights struggles occurring in the United States, as more than 100 reporters visited Montgomery during the boycott to profile the effort and its leaders.

Rosa Parks, while shying from the spotlight throughout her life, remained an esteemed figure in the history of American civil rights activism. In 1999, the U.S. Congress awarded her its highest honor, the Congressional Gold Medal.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Montgomery Bus Boycott

December 5, 1955 to December 20, 1956

Sparked by the arrest of Rosa Parks on 1 December 1955, the Montgomery bus boycott was a 13-month mass protest that ended with the U.S. Supreme Court ruling that segregation on public buses is unconstitutional. The Montgomery Improvement Association (MIA) coordinated the boycott, and its president, Martin Luther King, Jr., became a prominent civil rights leader as international attention focused on Montgomery. The bus boycott demonstrated the potential for nonviolent mass protest to successfully challenge racial segregation and served as an example for other southern campaigns that followed. In Stride Toward Freedom , King’s 1958 memoir of the boycott, he declared the real meaning of the Montgomery bus boycott to be the power of a growing self-respect to animate the struggle for civil rights.

The roots of the bus boycott began years before the arrest of Rosa Parks. The Women’s Political Council (WPC), a group of black professionals founded in 1946, had already turned their attention to Jim Crow practices on the Montgomery city buses. In a meeting with Mayor W. A. Gayle in March 1954, the council's members outlined the changes they sought for Montgomery’s bus system: no one standing over empty seats; a decree that black individuals not be made to pay at the front of the bus and enter from the rear; and a policy that would require buses to stop at every corner in black residential areas, as they did in white communities. When the meeting failed to produce any meaningful change, WPC president Jo Ann Robinson reiterated the council’s requests in a 21 May letter to Mayor Gayle, telling him, “There has been talk from twenty-five or more local organizations of planning a city-wide boycott of buses” (“A Letter from the Women’s Political Council”).

A year after the WPC’s meeting with Mayor Gayle, a 15-year-old named Claudette Colvin was arrested for challenging segregation on a Montgomery bus. Seven months later, 18-year-old Mary Louise Smith was arrested for refusing to yield her seat to a white passenger. Neither arrest, however, mobilized Montgomery’s black community like that of Rosa Parks later that year.

King recalled in his memoir that “Mrs. Parks was ideal for the role assigned to her by history,” and because “her character was impeccable and her dedication deep-rooted” she was “one of the most respected people in the Negro community” (King, 44). Robinson and the WPC responded to Parks’ arrest by calling for a one-day protest of the city’s buses on 5 December 1955. Robinson prepared a series of leaflets at Alabama State College and organized groups to distribute them throughout the black community. Meanwhile, after securing bail for Parks with Clifford and Virginia Durr , E. D. Nixon , past leader of the Montgomery chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), began to call local black leaders, including Ralph Abernathy and King, to organize a planning meeting. On 2 December, black ministers and leaders met at Dexter Avenue Baptist Church and agreed to publicize the 5 December boycott. The planned protest received unexpected publicity in the weekend newspapers and in radio and television reports.

On 5 December, 90 percent of Montgomery’s black citizens stayed off the buses. That afternoon, the city’s ministers and leaders met to discuss the possibility of extending the boycott into a long-term campaign. During this meeting the MIA was formed, and King was elected president. Parks recalled: “The advantage of having Dr. King as president was that he was so new to Montgomery and to civil rights work that he hadn’t been there long enough to make any strong friends or enemies” (Parks, 136).

That evening, at a mass meeting at Holt Street Baptist Church , the MIA voted to continue the boycott. King spoke to several thousand people at the meeting: “I want it to be known that we’re going to work with grim and bold determination to gain justice on the buses in this city. And we are not wrong.… If we are wrong, the Supreme Court of this nation is wrong. If we are wrong, the Constitution of the United States is wrong. If we are wrong, God Almighty is wrong” ( Papers 3:73 ). After unsuccessful talks with city commissioners and bus company officials, on 8 December the MIA issued a formal list of demands: courteous treatment by bus operators; first-come, first-served seating for all, with blacks seating from the rear and whites from the front; and black bus operators on predominately black routes.

The demands were not met, and Montgomery’s black residents stayed off the buses through 1956, despite efforts by city officials and white citizens to defeat the boycott. After the city began to penalize black taxi drivers for aiding the boycotters, the MIA organized a carpool. Following the advice of T. J. Jemison , who had organized a carpool during a 1953 bus boycott in Baton Rouge, the MIA developed an intricate carpool system of about 300 cars. Robert Hughes and others from the Alabama Council for Human Relations organized meetings between the MIA and city officials, but no agreements were reached.

In early 1956, the homes of King and E. D. Nixon were bombed. King was able to calm the crowd that gathered at his home by declaring: “Be calm as I and my family are. We are not hurt and remember that if anything happens to me, there will be others to take my place” ( Papers 3:115 ). City officials obtained injunctions against the boycott in February 1956, and indicted over 80 boycott leaders under a 1921 law prohibiting conspiracies that interfered with lawful business. King was tried and convicted on the charge and ordered to pay $500 or serve 386 days in jail in the case State of Alabama v. M. L. King, Jr. Despite this resistance, the boycott continued.

Although most of the publicity about the protest was centered on the actions of black ministers, women played crucial roles in the success of the boycott. Women such as Robinson, Johnnie Carr , and Irene West sustained the MIA committees and volunteer networks. Mary Fair Burks of the WPC also attributed the success of the boycott to “the nameless cooks and maids who walked endless miles for a year to bring about the breach in the walls of segregation” (Burks, “Trailblazers,” 82). In his memoir, King quotes an elderly woman who proclaimed that she had joined the boycott not for her own benefit but for the good of her children and grandchildren (King, 78).

National coverage of the boycott and King’s trial resulted in support from people outside Montgomery. In early 1956 veteran pacifists Bayard Rustin and Glenn E. Smiley visited Montgomery and offered King advice on the application of Gandhian techniques and nonviolence to American race relations. Rustin, Ella Baker , and Stanley Levison founded In Friendship to raise funds in the North for southern civil rights efforts, including the bus boycott. King absorbed ideas from these proponents of nonviolent direct action and crafted his own syntheses of Gandhian principles of nonviolence. He said: “Christ showed us the way, and Gandhi in India showed it could work” (Rowland, “2,500 Here Hail”). Other followers of Gandhian ideas such as Richard Gregg , William Stuart Nelson , and Homer Jack wrote the MIA offering support.

On 5 June 1956, the federal district court ruled in Browder v. Gayle that bus segregation was unconstitutional, and in November 1956 the U.S. Supreme Court affirmed Browder v. Gayle and struck down laws requiring segregated seating on public buses. The court’s decision came the same day that King and the MIA were in circuit court challenging an injunction against the MIA carpools. Resolved not to end the boycott until the order to desegregate the buses actually arrived in Montgomery, the MIA operated without the carpool system for a month. The Supreme Court upheld the lower court’s ruling, and on 20 December 1956 King called for the end of the boycott; the community agreed. The next morning, he boarded an integrated bus with Ralph Abernathy, E. D. Nixon, and Glenn Smiley. King said of the bus boycott: “We came to see that, in the long run, it is more honorable to walk in dignity than ride in humiliation. So … we decided to substitute tired feet for tired souls, and walk the streets of Montgomery” ( Papers 3:486 ). King’s role in the bus boycott garnered international attention, and the MIA’s tactics of combining mass nonviolent protest with Christian ethics became the model for challenging segregation in the South.

Joe Azbell, “Blast Rocks Residence of Bus Boycott Leader,” 31 January 1956, in Papers 3:114–115 .

Baker to King, 24 February 1956, in Papers 3:139 .

Burks, “Trailblazers: Women in the Montgomery Bus Boycott,” in Women in the Civil Rights Movement , ed. Crawford et al., 1990.

“Don’t Ride the Bus,” 2 December 1955, in Papers 3:67 .

U. J. Fields, Minutes of Montgomery Improvement Association Founding Meeting, 5 December 1955, in Papers 3:68–70 .

Gregg to King, 2 April 1956, in Papers 3:211–212 .

Indictment, State of Alabama v. M. L. King, Jr., et al. , 21 February 1956, in Papers 3:132–133 .

Introduction, in Papers 3:3–7 ; 17–21 ; 29 .

Jack to King, 16 March 1956, in Papers 3:178–179 .

Judgment and Sentence of the Court, State of Alabama v. M. L. King, Jr. , 22 March 1956, in Papers 3:197 .

King, Statement on Ending the Bus Boycott, 20 December 1956, in Papers 3:485–487 .

King, Stride Toward Freedom , 1958.

King, Testimony in State of Alabama v. M. L. King, Jr. , 22 March 1956, in Papers 3:183–196 .

King to the National City Lines, Inc., 8 December 1955, in Papers 3:80–81 .

“A Letter from the Women’s Political Council to the Mayor of Montgomery, Alabama,” in Eyes on the Prize , ed. Carson et al., 1991.

MIA Mass Meeting at Holt Street Baptist Church, 5 December 1955, in Papers 3:71–79 .

Nelson to King, 21 March 1956, in Papers 3:182–183 .

Parks and Haskins, Rosa Parks , 1992.

Robinson, Montgomery Bus Boycott , 1987.

Stanley Rowland, Jr., “2,500 Here Hail Boycott Leader,” New York Times , 26 March 1956.

Rustin to King, 23 December 1956, in Papers 3:491–494 .

If you're seeing this message, it means we're having trouble loading external resources on our website.

If you're behind a web filter, please make sure that the domains *.kastatic.org and *.kasandbox.org are unblocked.

To log in and use all the features of Khan Academy, please enable JavaScript in your browser.

Course: US history > Unit 8

- Introduction to the Civil Rights Movement

- African American veterans and the Civil Rights Movement

- Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka

- Emmett Till

The Montgomery Bus Boycott

- "Massive Resistance" and the Little Rock Nine

- The March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom

- The Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965

- SNCC and CORE

- Black Power

- The Civil Rights Movement

- On December 1, 1955, Rosa Parks , a black seamstress, was arrested in Montgomery, Alabama for refusing to give up her bus seat so that white passengers could sit in it.

- Rosa Parks’s arrest sparked the Montgomery Bus Boycott , during which the black citizens of Montgomery refused to ride the city’s buses in protest over the bus system’s policy of racial segregation. It was the first mass-action of the modern civil rights era, and served as an inspiration to other civil rights activists across the nation.

- Martin Luther King, Jr. , a Baptist minister who endorsed nonviolent civil disobedience, emerged as leader of the Boycott.

- Following a November 1956 ruling by the Supreme Court that segregation on public buses was unconstitutional, the bus boycott ended successfully. It had lasted 381 days.

Rosa Parks’s arrest

Origins of the bus boycott, the boycott succeeds, what do you think.

- William H. Chafe, The Unfinished Journey: America Since World War II , eighth edition (New York: Oxford U.P., 2015), 153-154. For the details of her arrest see, “Police Department, City of Montgomery—Rosa Parks Arrest Report,” December 1, 1955.

- See James Patterson, *Grand Expectations: The United States, 1945-1974 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1996), 400; Davis Houck, and Matthew Grindy, Emmett Till and the Mississippi Press (Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi, 2008), x.

- See Patterson, Grand Expectations , 400-401.

- Patterson, Grand Expectations , 405.

- Quoted in Chafe, The Unfinished Journey , 156.

Want to join the conversation?

- Upvote Button navigates to signup page

- Downvote Button navigates to signup page

- Flag Button navigates to signup page

- Skip to global NPS navigation

- Skip to the main content

- Skip to the footer section

Exiting nps.gov

The montgomery bus boycott.

Years before the boycott, Dexter Avenue minister Vernon Johns sat down in the "whites-only" section of a city bus. When the driver ordered him off the bus, Johns urged other passengers to join him. On March 2, 1955, a black teenager named Claudette Colvin dared to defy bus segregation laws and was forcibly removed from another Montgomery bus.

Nine months later, Rosa Parks - a 42-year-old seamstress and NAACP member- wanted a guaranteed seat on the bus for her ride home after working as a seamstress in a Montgomery department store. After work, she saw a crowded bus stop. Knowing that she would not be able to sit, Parks went to a local drugstore to buy an electric heating pad. After shopping, Parks entered the less crowded Cleveland Avenue bus and was able to find an open seat in the 'colored' section of the bus for her ride home.

Despite having segregated seating arrangements on public buses, it was routine in Montgomery for bus drivers to force African Americans out of their seats for a white passenger. There was very little African Americans could do to stop the practice because bus drivers in Montgomery had the legal ability to arrest passengers for refusing to obey their orders. After a few stops on Parks’ ride home, the white seating section of the bus became full. The driver demanded that Parks give up her seat on the bus so a white passenger could sit down. Parks refused to surrender her seat and was arrested for violating the bus driver’s orders.

Organizing the Boycott

Montgomery's black citizens reacted decisively to the incident. By December 2, schoolteacher Jo Ann Robinson had mimeographed and delivered 50,000 protest leaflets around town. E.D. Nixon, a local labor leader, organized a December 4 meeting at Dexter Avenue Baptist Church , where local black leaders formed the Montgomery Improvement Association (MIA)to spearhead a boycott and negotiate with the bus company.

Over 70% of the cities bus patrons were African American and the one-day boycott was 90% effective. The MIA elected as their president a new but charismatic preacher, Martin Luther King Jr. Under his leadership, the boycott continued with astonishing success. The MIA established a carpool for African Americans. Over 200 people volunteered their car for a car pool and roughly 100 pickup stations operated within the city. To help fund the car pool, the MIA held mass gatherings at various African American churches where donations were collected and members heard news about the success of the boycott.

Roots in Brown v Board

Fred Gray, member and lawyer of the MIA, organized a legal challenge to the city ordinances requiring segregation on Montgomery buses. Before 1954, the Plessy v. Ferguson decision ruled that segregation was constitutional as long as it was equal. Yet, the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education U.S. Supreme Court decision outlawed segregation in public schools. Therefore, it opened the door to challenge segregation in other areas as well, such as city busing. Gray gathered Aurelia Browder, Susie McDonald, Claudette Colvin and Mary Louise Smith to challenge the constitutionality of the city busing laws. All four of the women had been previously mistreated on the city buses because of their race. The case took the name Browder v. Gayle. Gray argued their 14th Amendment right to equal protection of the law was violated, the same argument made in the Brown v. Board of Education case.

On June 5, 1956, a three-judge U.S. District Court ruled 2-1 that segregation on public buses was unconstitutional. The majority cited Brown v. Board of Education as a legal precedent for desegregation and concluded, “In fact, we think that Plessy v. Ferguson has been impliedly, though not explicitly, overruled,…there is now no rational basis upon which the separate but equal doctrine can be validly applied to public carrier transportation...”

The city of Montgomery appealed the U.S. District Court decision to the U.S. Supreme Court and continued to practice segregation on city busing.

For nearly a year, buses were virtually empty in Montgomery. Boycott supporters walked to work--as many as eight miles a day--or they used a sophisticated system of carpools with volunteer drivers and dispatchers. Some took station-wagon "rolling taxis" donated by local churches.

Montgomery City Lines lost between 30,000 and 40,000 bus fares each day during the boycott. The bus company that operated the city busing had suffered financially from the seven month long boycott and the city became desperate to end the boycott. Local police began to harass King and other MIA leaders. Car pool drivers were arrested and taken to court for petty traffic violations. Despite all the harassment, the boycott remained over 90% successful. African Americans took pride in the inconveniences caused by limited transportation. One elderly African American woman replied that, “My soul has been tired for a long time. Now my feet are tired, and my soul is resting.” The promise of equality declared in Brown v. Board of Education for Montgomery African Americans helped motivate them to continue the boycott.

The company reluctantly desegregated its buses only after November 13, 1956, when the Supreme Court ruled Alabama's bus segregation laws unconstitutional.

Beginning a Movement

The Montgomery bus boycott began the modern Civil Rights Movement and established Martin Luther King Jr. as its leader. King instituted the practice of massive non-violent civil disobedience to injustice, which he learned from studying Gandhi. Montgomery, Alabama became the model of massive non-violent civil disobedience that was practiced in such places as Birmingham, Selma, and Memphis. Even though the Civil Rights Movement was a social and political movement, it was influenced by the legal foundation established from Brown v. Board of Education.

Brown overturned the long held practice of the “separate but equal” doctrine established by Plessy. From then on, any legal challenge on segregation cited Brown as a precedent for desegregation. Without Brown, it is impossible to know what would have happened in Montgomery during the boycott.

The boycott would have been difficult to continue because the city would have won its challenge to shut down the car pool. Without the car pool and without any legal precedent to end segregation, the legal process could have lasted years. Those involved in the boycott might have lost hope and given up with the lack of progress. However, the precedent established by Brown gave boycotters hope that a legal challenge would successfully end segregation on city buses. Therefore, the influence of Brown on the Montgomery Bus Boycott and the Civil Rights Movement is undeniable. King described Brown’s influence as, “To all men of good will, this decision came as a joyous daybreak to end the long night of human captivity. It came as a great beacon light of hope to millions of colored people throughout the world who had had a dim vision of the promised land of freedom and justice . . . this decision came as a legal and sociological deathblow to an evil that had occupied the throne of American life for several decades.”

You Might Also Like

- selma to montgomery national historic trail

- montgomery bus boycott

- civil rights

Selma To Montgomery National Historic Trail

Last updated: September 21, 2022

- Modern History

Why was the Montgomery Bus Boycott so successful?

On December 1, 1955, a single act of defiance by Rosa Parks against racial segregation on a Montgomery, Alabama, bus ignited a year-long boycott that would become a pivotal moment in the Civil Rights Movement.

The Montgomery Bus Boycott, led by a young Martin Luther King Jr., mobilized the African American community in a collective stand against injustice, challenging the deeply entrenched laws of segregation in the South.

This historic protest signaled the power of nonviolent resistance and grassroots activism in the fight for racial equality.

Here is how it happened.

What were the causes of the boycott?

Before the Montgomery Bus Boycott, the city of Montgomery, Alabama, like much of the American South, enforced strict racial segregation laws, known as Jim Crow laws, which mandated separate public facilities for white and black citizens.

Public transportation was no exception, with buses segregated by race and black passengers often subjected to humiliating treatment.

On December 1, 1955, Rosa Parks , a seamstress and a member of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), refused to give up her seat to a white passenger on a Montgomery bus, as was required by law.

Her arrest for this act of civil disobedience sparked outrage within the African American community.

In response, black leaders in Montgomery, including a young pastor named Martin Luther King Jr. , organized a meeting at the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church to discuss a course of action.

They formed the Montgomery Improvement Association (MIA) to oversee the boycott and chose King as its president, recognizing his leadership potential and oratorical skills.

How did the Montgomery Bus Boycott work?

The Montgomery Bus Boycott officially began on December 5, 1955, the day of Rosa Parks' trial.

In preparation, flyers were distributed and announcements were made in black churches throughout the city, calling for African Americans to avoid using the buses on that day.

The response was overwhelming, with an estimated 90% of Montgomery's black residents participating in the boycott on the first day.

The boycotters' demands were simple: courteous treatment by bus drivers, first-come-first-served seating with blacks filling seats from the back and whites from the front, and the employment of black bus drivers on predominantly black routes.

The success of the initial boycott led to a meeting at the Holt Street Baptist Church, where more than 5,000 black residents gathered to discuss the possibility of extending the protest.

With Martin Luther King Jr. emerging as a leading voice, the community decided to continue the boycott until their demands for fair treatment on the buses were met.

The boycott, initially planned to last for just one day, stretched on for 381 days, severely impacting the city's transit system and drawing international attention.

How did the authorities respond?

The city's response was initially dismissive, and the boycotters' resolve was met with resistance from white officials and citizens.

The city government and the bus company refused to negotiate, and legal and economic pressure was applied to try to break the boycott.

Despite these challenges, the black community's commitment to the boycott remained strong.

They organized carpool systems, and many walked long distances to work, school, and church.

The city's legal system targeted the boycott with injunctions and lawsuits, aiming to cripple the movement by arresting its leaders, including Martin Luther King Jr., on charges related to the boycott.

Economic pressure was also applied, as many black workers, who were participating in the boycott, faced threats of job loss or actual termination.

King's eloquence and conviction were evident in his speeches and sermons, which he used to articulate the goals of the boycott and to call for unity and perseverance.

His home and the churches where he spoke became targets for segregationist violence, with his house being bombed in January 1956.

Why did the boycott end?

The successful conclusion of the boycott, with the Supreme Court ruling in Browder v. Gayle that segregation on public buses was unconstitutional, was a testament to the effectiveness of coordinated, nonviolent protest.

This Supreme Court ruling not only desegregated buses in Montgomery but also set a legal precedent that would be used to challenge other forms of segregation.

The boycott also propelled Martin Luther King Jr. into the national spotlight, establishing him as a prominent leader of the Civil Rights Movement.

The Montgomery Bus Boycott had a profound impact on the Civil Rights Movement, setting a precedent for nonviolent protest and serving as a catalyst for future civil rights actions.

The successful boycott demonstrated the power of collective action and the effectiveness of nonviolent resistance, inspiring similar protests and boycotts across the South.

It also brought national and international attention to the struggle for civil rights in the United States, highlighting the injustices of segregation and racial discrimination.

The Montgomery Bus Boycott is often seen as the beginning of a new phase in the Civil Rights Movement, one that focused on direct action and mass mobilization.

It laid the groundwork for future campaigns, such as the sit-ins , Freedom Rides , and the March on Washington, which further advanced the cause of civil rights and social justice in America.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources.

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2024.

Contact via email

- Agriculture

- Arts & Literature

- Business & Industry

- Geography & Environment

- Government & Politics

- Science & Technology

- Sports & Recreation

- Organizations

- Collections

- Quick Facts

Montgomery Bus Boycott

In March 1955, Claudette Colvin , a 15-year-old high school junior, refused to give up her bus seat to a white person. She was arrested for violating the segregated seating ordinances and mistreated by police. This angered the black community and sparked a brief, informal boycott of buses by many black residents. In August, Montgomery's black community was shaken by the brutal lynching of 14-year-old Chicago native Emmett Till in Mississippi. Two months later, 18-year-old Mary Louise Smith, a house maid, was arrested for refusing to give up her seat. African Americans in Montgomery felt beleaguered.

Although Parks did not plan her calm, determined protest, she recalled that she had a life history of rebelling against racial mistreatment. She believed that she had been "pushed as far as [she] could stand to be pushed." Parks was arrested and then bailed out that night by friend E. D. Nixon , a Pullman car porter who had headed the local and Alabama state branches of the NAACP, and by two white friends, attorney Clifford Durr and his activist wife, Virginia Durr . The Durrs and Nixon persuaded Parks to allow her arrest to be used as a test case for the constitutionality of bus segregation.

At the outset white officials and opinion leaders believed that the bus boycott would collapse quickly and that blacks were not capable of a long-term protest campaign. The white community solidified in opposition, spurred by growth of the local White Citizens' Council , but a few brave white citizens, such as Virginia and Clifford Durr and city librarian Juliette Hampton Morgan , supported the civil rights effort.

In June 1956, halfway through the boycott, the federal court in Montgomery ruled in Browder v. Gayle that Alabama's bus segregation laws, both city and state, violated the Fourteenth Amendment and were thus unconstitutional. The U.S. Supreme Court upheld that decision in November, and MIA members voted to end the boycott. At the same moment, the city's belated injunction shut down the carpool system by making it illegal, but those who had driven joined those who had been walking all along. After the city government lost its final appeal in the Supreme Court, black citizens desegregated Montgomery's buses on December 21, 1956. White extremists fired on buses and bombed churches, but the year-long bus protest ended in victory over the city's Jim Crow laws.

Additional Resources

Boycott. DVD, directed by Clark Johnson. Los Angeles: Home Box Office, Inc., 2001.

Burns, Stewart, ed. Daybreak of Freedom: The Montgomery Bus Boycott . Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1997.

Eyes on the Prize: Awakenings (1954-1956). DVD, directed by Henry Hampton. Boston: Blackside, 1987.

Gray, Fred D. Bus Ride to Justice . Montgomery: Black Belt Press, 1994.

King, Martin Luther, Jr. Stride Toward Freedom . New York: Harper, 1958.

Robinson, Jo Ann Gibson. The Montgomery Bus Boycott and the Women Who Started It . Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1987.

Thornton, J. Mills III. Dividing Lines . Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2002.

External Links

- Civil Rights Digital Library

- Troy University Rosa Parks Museum

- Justice Without Violence – Alabama Public Television

Stewart Burns Williams College

Last Updated

- Share on Facebook

- Send via Email

Related Articles

Greenbackism in Alabama

The Greenback movement, also referred to as Greenbackism, was a short-lived coalition of farmers and laborers that arose in the mid-1870s to protest a variety of federal monetary policies. The movement made allies with organized labor and died out in the early 1880s but managed to influence the Populist movement…

Jay Carrington Scott

Jay Carrington Scott (1953-2009) was a notable saxophone player who learned his trade in the music clubs of Dothan, Houston County, and the Wiregrass region. He later traveled the country, playing often in Las Vegas, and recorded with many notable groups and artists of the late 1970s and early 1980s.…

Alabama Public Television

Established in 1953, Alabama Public Television (APT) was the first educational television network in the United States and has served Alabama for more than five decades. Headquartered in Birmingham, the organization pioneered the use of microwave towers to transmit its signals and was the first television station in the state…

Alabama Nature Center

The Alabama Nature Center (ANC) is an outdoor environmental education facility located in Millbrook, in southwestern Elmore County. Administered by the Alabama Wildlife Federation (AWF), it offers educational programs and activities to students, educators, church and civic groups, and the general public. ANC is located on the 350-acre former estate…

Share this Article

A blog of the U.S. National Archives

Pieces of History

The Montgomery Bus Boycott

In commemoration of the anniversary of the Montgomery Bus Boycott, today’s post comes from Sarah Basilion, an intern in the National Archives History Office.

Sixty years ago, Rosa Parks, a 42-year-old black woman, refused to give up her seat to a white passenger on a Montgomery, Alabama, public bus.

On December 1, 1955, Parks, a seamstress and secretary for the Montgomery chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), was taking the bus home after a long day of work.

The white section of the bus had filled, so the driver asked Parks to give up her seat in the designated black section of the bus to accommodate a white passenger.

She refused to move.

When it became apparent after several minutes of argument that Parks would not relent, the bus driver called the police. Parks was arrested for being in violation of Chapter 6, Section 11, of the Montgomery City Code, which upheld a policy of racial segregation on public buses.

Parks was not the first person to engage in this act of civil disobedience.

Earlier that year, 15-year-old Claudette Colvin refused to give up her seat on a Montgomery bus. She was arrested, but local civil rights leaders were concerned that she was too young and poor to be a sympathetic plaintiff to challenge segregation.

Parks—a middle-class, well-respected civil rights activist—was the ideal candidate.

Just a few days after Parks’s arrest, activists announced plans for the Montgomery Bus Boycott.

The boycott, which officially began December 5, 1955, did not support just Parks but countless other African Americans who had been arrested for the same reason.

E. D. Nixon, president of the local NAACP chapter, called for all African-American citizens to boycott the public bus system to protest the segregation policy. Nixon and his supporters vowed to abstain from riding Montgomery public buses until the policy was abolished.

Instead of buses, African Americans took taxis driven by black drivers who had lowered their fares in support of the boycott, walked, cycled, drove private cars, and even rode mules or drove in horse-drawn carriages to get around. African-American citizens made up a full three-quarters of regular bus riders, causing the boycott to have a strong economic impact on the public transportation system and on the city of Montgomery as a whole.

The boycott was proving to be a successful means of protest.

The city of Montgomery tried multiple tactics to subvert the efforts of boycotters. They instituted regulations for cab fares that prevented black cab drivers from offering lower fares to support boycotters. The city also pressured car insurance companies to revoke or refuse insurance to black car owners so they could not use their private vehicles for transportation in lieu of taking the bus.

Montgomery’s efforts were futile as the local black community, with the support of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., churches—and citizens around the nation—were determined to continue with the boycott until their demand for racially integrated buses was met.

The boycott lasted from December 1, 1955, when Rosa Parks was arrested, to December 20, 1956, when Browder v. Gayle , a Federal ruling declaring racially segregated seating on buses to be unconstitutional, took effect.

Although it took more than a year, Rosa Parks’s refusal to give up her seat on a public bus sparked incredible change that would forever impact civil rights in the United States.

Parks continued to raise awareness for the black struggle in America and the Civil Rights movement for the rest of her life. For her efforts she was awarded both the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the highest honor given by the executive branch, and the Congressional Gold Medal, the highest honor given by the legislative branch.

To learn more about the life of Rosa Parks, read Michael Hussey’s 2013 Pieces of History post Honoring the “Mother of the Civil Rights Movement. ”

And plan your visit to the National Archives to view similar documents in our “ Records of Rights ” exhibit or explore documents in our online catalog .

Copies of documents relating to Parks’s arrest submitted as evidence in the Browder v. Gayle case are held in the National Archives at Atlanta in Morrow, Georgia.

Share this:

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Rosa Parks, Martin Luther King Jr., and the Montgomery Bus Boycott

Written by: Stewart Burns, Union Institute & University

By the end of this section, you will:.

- Explain how and why various groups responded to calls for the expansion of civil rights from 1960 to 1980

Suggested Sequencing

Use this narrative with the Jackie Robinson Narrative, The Little Rock Nine Narrative, The Murder of Emmett Till Narrative, and the Rosa Parks’s Account of the Montgomery Bus Boycott (Radio Interview), April 1956 Primary Source to discuss the rise of the African American civil rights movement pre-1960.

Rosa Parks launched the Montgomery bus boycott when she refused to give up her bus seat to a white man. The boycott proved to be one of the pivotal moments of the emerging civil rights movement. For 13 months, starting in December 1955, the black citizens of Montgomery protested nonviolently with the goal of desegregating the city’s public buses. By November 1956, the Supreme Court had banned the segregated transportation legalized in 1896 by the Plessy v. Ferguson ruling. Montgomery’s boycott was not entirely spontaneous, and Rosa Parks and other activists had prepared to challenge segregation long in advance.

On December 1, 1955, a tired Rosa L. Parks left the department store where she worked as a tailor’s assistant and boarded a crowded city bus for the ride home. She sat down between the “whites only” section in the front and the “colored” section in the back. Black riders were to sit in this middle area only if the back was filled. When a white man boarded, the bus driver ordered four African American passengers to stand so the white passenger could sit. The other riders reluctantly got up, but Parks refused. She knew she was not violating the segregation law, because there were no vacant seats. The police nevertheless arrived and took her to jail.

Parks had not planned her protest, but she was a civil rights activist well trained in civil disobedience so she remained calm and resolute. Other African American women had challenged the community’s segregation statutes in the past several months, but her cup of forbearance had run over. “I had almost a life history of being rebellious against being mistreated because of my color,” Parks recalled. On this occasion more than others “I felt that I was not being treated right and that I had a right to retain the seat that I had taken.” She was fighting for her natural and constitutional rights when she protested against the treatment that stripped away her dignity. “When I had been pushed as far as I could stand to be pushed. I had decided that I would have to know once and for all what rights I had as a human being and a citizen.” She was attempting to “bring about freedom from this kind of thing.”

Perhaps the incident was not as spontaneous as it appeared, however. Parks was an active participant in the civil rights movement for several years and had served as secretary of both the Montgomery and Alabama state NAACP. She founded the youth council of the local NAACP and trained the young people in civil rights activism. She had even discussed challenging the segregated bus system with the youth council before 15-year-old Claudette Colvin was arrested for refusing to give up her seat the previous March. Ill treatment on segregated city buses had festered into the most acute problem in the black community in Montgomery. Segregated buses were part of a system that inflicted Jim Crow segregation upon African Americans.

In 1949, a group of professional black women and men had formed the Women’s Political Council (WPC) of Montgomery. They were dedicated to organizing African Americans to demand equality and civil rights by seeking to change Jim Crow segregation in public transportation. In May 1954, WPC president Jo Ann Robinson informed the mayor that African Americans in the city were considering launching a boycott.

The WPC converted abuse on buses into a glaring public issue, and the group collaborated with the NAACP and other civil rights organizations to challenge segregation there. Parks was bailed out of jail by local NAACP leader, E. D. Nixon, who was accompanied by two liberal whites, attorney Clifford Durr and his wife Virginia Foster Durr, leader of the anti-segregation Southern Conference Educational Fund (SCEF). Virginia Durr had become close friends with Parks. In fact, she helped fund Parks’s attendance at a workshop for two weeks on desegregating schools only a few months before.

The Durrs and Nixon had worked with Parks to plot a strategy for challenging the constitutionality of segregation on Montgomery buses. After Parks’s arrest, Robinson agreed with them and thought the time was ripe for the planned boycott. She worked with two of her students, staying up all night mimeographing flyers announcing a one-day bus boycott for Monday, December 5.

Because of ministers’ leadership in the vibrant African American churches in the city, Nixon called on the ministers to win their support for the boycott. Reverend Martin Luther King Jr., a young and relatively unknown minister of the middle-class Dexter Avenue Baptist Church, was unsure about the timing but offered assistance. Baptist minister Ralph Abernathy eagerly supported the boycott.

On December 5, African Americans boycotted the buses. They walked to work, carpooled, and took taxis as a measure of solidarity. Parks was convicted of violating the segregation law and charged a $14 fine. Because of the success of the boycott, black leaders formed the Montgomery Improvement Association (MIA) to continue the protest and surprisingly elected Reverend King president.

Rosa Parks, with Martin Luther King Jr. in the background, is pictured here soon after the Montgomery Bus Boycott.

After earning his PhD at Boston University’s School of Theology, King had returned to the Deep South with his new bride, Coretta Scott, a college-educated, rural Alabama native. On the night of December 5, 1955, the 26-year-old pastor presided over the first MIA mass meeting, in a supercharged atmosphere of black spirituality. Participants felt the Holy Spirit was alive that night with a palpable power that transfixed. When King rose to speak, unscripted words burst out of him, a Lincoln-like synthesis of the rational and emotional, the secular and sacred. The congregants must protest, he said, because both their divinity and their democracy required it. They would be honored by future generations for their moral courage.

The participants wanted to continue the protest until their demands for fairer treatment were met as well as establishment of a first-come, first-served seating system that kept reserved sections. White leaders predicted that the boycott would soon come to an end because blacks would lose enthusiasm and accept the status quo. When blacks persisted, some of the whites in the community formed the White Citizens’ Council, an opposition movement committed to preserving white supremacy.

The bus boycott continued and was supported by almost all of Montgomery’s 42,000 black residents. The women of the MIA created a complex carpool system that got black citizens to work and school. By late December, city commissioners were concerned about the effects of the boycott on business and initiated talks to try to resolve the dispute. The bus company (which now supported integrated seating) feared it might go bankrupt and urged compromise. However, the commissioners refused to grant any concessions and the negotiations broke down over the next few weeks. The commissioners adopted a “get tough” policy when it became clear that the boycott would continue. Police harassed carpool drivers. They arrested and jailed King on a petty speeding charge when he was helping out one day. Angry whites tried to terrorize him and bombed his house with his wife and infant daughter inside, but no one was injured. Drawing from the Sermon on the Mount, the pastor persuaded an angry crowd to put their guns away and go home, preventing a bloody riot. Nixon’s home and Abernathy’s church were also bombed.

On January 30, MIA leaders challenged the constitutionality of bus segregation because the city refused their moderate demands. Civil rights attorney Fred Gray knew that a state case would be unproductive and filed a federal lawsuit. Meanwhile, city leaders went on the offensive and indicted nearly 100 boycott leaders, including King, on conspiracy charges. King’s trial and conviction in March 1956 elicited negative national publicity for the city on television and in newspapers. Sympathetic observers sent funds to Montgomery to support the movement.

In June 1956, the Montgomery federal court ruled in Browder v. Gayle that Alabama’s bus segregation laws violated the Fourteenth Amendment’s guarantee of equality and were unconstitutional. The Supreme Court upheld the decision in November. In the wake of the court victories, MIA members voted to end the boycott. Black citizens triumphantly rode desegregated Montgomery’s buses on December 21, 1956.

A diagram of the Montgomery bus where Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat was used in court to ultimately strike down segregation on the city’s buses.

The Montgomery bus boycott made King a national civil rights leader and charismatic symbol of black equality. Other black ministers and activists like Abernathy, Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth, Bayard Rustin, and Ella Baker also became prominent figures in the civil rights movement. The ministers formed the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) to protest white supremacy and work for voting rights throughout the South, testifying to the importance of black churches and ministers as a vital element of the civil rights movement.

The Montgomery bus boycott paved the way for the civil rights movement to demand freedom and equality for African Americans and transformed American politics, culture, and society by helping create the strategies, support networks, leadership, vision, and spiritual direction of the movement. It demonstrated that ordinary African American citizens could band together at the local level to demand and win in their struggle for equal rights and dignity. The Montgomery experience laid the foundations for the next decade of a nonviolent direct-action movement for equal civil rights for African Americans.

Review Questions

1. All of the following are true of Rosa Parks except

- she served as secretary of the Montgomery NAACP

- she trained young people in civil rights activism

- she unintentionally challenged the bus segregation laws of Montgomery

- she was well-trained in civil disobedience

2. The initial demand of those who boycotted the Montgomery Bus System was for the city to

- hire more black bus drivers in Montgomery

- arrest abusive bus drivers

- remove the city commissioners

- modify Jim Crow laws in public transportation

3. The Montgomery Improvement Association was formed in 1955 primarily to

- bring a quick end to the bus boycott

- maintain segregationist policies on public buses

- provide carpool assistance to the boycotters

- organize the bus protest

4. As a result of the successful Montgomery Bus Boycott, Martin Luther King Jr. was

- elected mayor of Montgomery

- targeted as a terrorist and held in jail for the duration of the boycott

- recognized as a new national voice for African American civil rights

- made head pastor of his church

5. The Federal court case Browder v. Gayle established that

- the principles in Brown v. Board of Education were also relevant in the Montgomery Bus Boycott

- the Montgomery bus segregation laws were a violation of the constitutional guarantee of equality

- the principles of Plessy v. Ferguson were similar to those in the Montgomery bus company

- the conviction of Martin Luther King Jr. was unconstitutional

6. All the following resulted from the Montgomery bus boycott except

- the formation of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC)

- the emergence of Martin Luther King Jr. as a national leader

- the immediate end of Jim Crow laws in Alabama

- negative national publicity for the city of Montgomery

Free Response Questions

- Explain how the Montgomery Bus Boycott affected the civil rights movement.

- Describe how the Montgomery Bus Boycott propelled Martin Luther King Jr. to national notice.

AP Practice Questions

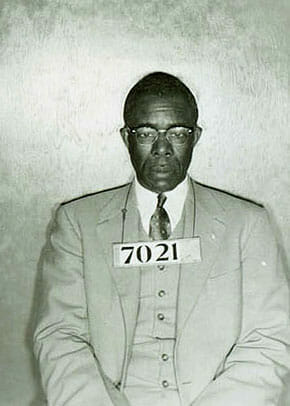

Rosa Parks being fingerprinted by Deputy Sheriff D. H. Lackey after her arrest in December 1955.

1. Which of the following had the most immediate impact on events in the photograph?

- The integration of the U.S. military

- The Supreme Court decision in Plessy v. Ferguson

- The Supreme Court decision in Brown v. Board of Education

- The integration of Little Rock (AR) Central High School

2. The actions leading to the provided photograph were similar to those associated with

- the labor movement in the 1920s

- the women’s suffrage movement in the early twentieth century

- the work of abolitionists in the 1850s

- the rise of the Ku Klux Klan in the 1920s

3. The situation depicted in the provided photograph contributed most directly to the

- economic development of the South

- growth of the suburbs

- growth of the civil right movement

- evolution of the anti-war movement

Primary Sources

Burns, Steward, ed. Daybreak of Freedom: The Montgomery Bus Boycott. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1997.

Garrow, David J, ed. Montgomery Bus Boycott and the Women Who Started It: The Memoir of Jo Ann Gibson Robinson . Nashville, TN: University of Tennessee Press, 1987.

Greenlee, Marcia M. “Interview with Rosa McCauley Parks.” August 22-23, 1978, Detroit. Cambridge, MA: Black Women Oral History Project, Harvard University. https://iiif.lib.harvard.edu/manifests/view/drs:45175350$14i

Suggested Resources

Branch, Taylor. Parting the Waters: America in the King Years 1954-63 . New York: Simon and Schuster, 1988.

Brinkley, Douglas. Rosa Parks . New York: Penguin, 2000.

Rosa Parks Museum, Montgomery, AL. www.troy.edu/rosaparks

Williams, Juan. Eyes on the Prize: America’s Civil Rights Years, 1954-1965 . New York: Penguin, 2013.

Related Content

Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness

In our resource history is presented through a series of narratives, primary sources, and point-counterpoint debates that invites students to participate in the ongoing conversation about the American experiment.

- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- About OAH Magazine of History

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Figures and tables.

- < Previous

To Walk in Dignity: The Montgomery Bus Boycott

Clayborne Carson is the director of the Martin Luther King, Jr. Papers Project and Professor of History at Stanford University. He has co-edited five volumes of a projected fourteen volume edition of The Papers of Martin Luther King, Jr. His most recent publication is African American Lives: The Struggle for Freedom (2005), a textbook co-authored by Emma J. Lapsansky-Werner and Gary B. Nash .

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Clayborne Carson, To Walk in Dignity: The Montgomery Bus Boycott, OAH Magazine of History , Volume 19, Issue 1, January 2005, Pages 13–15, https://doi.org/10.1093/maghis/19.1.13

- Permissions Icon Permissions

“…when the history books are written in the future, somebody will have to say, ‘There lived a race of people, a black people … who had the moral courage to stand up for their rights. And thereby they injected a new meaning into the veins of history and of civilization.‘” —Martin Luther King, Jr., December 5, 1955 ( 1 )

K ing's sense of the historical importance of the Montgomery bus boycott was remarkable, given that it had just begun the morning of his speech. Although boycott leaders were not sure at first that they should seek desegregation on the city's buses rather than simply better treatment, King correctly understood that the Montgomery protest concerned more far-reaching goals and ideals. “We are determined here in Montgomery to work and fight until justice runs down like water, and righteousness like a mighty stream,” he announced at the first mass meeting of the Montgomery Improvement Association (MIA) held on Monday, December 5, 1955, four days after Rosa Parks was arrested for refusing to give up her bus seat to a white man ( 2 ).

Because he was selected to head the MIA, King became the best known of the boycott's participants and his Stride Toward Freedom: The Montgomery Story (1958) has remained the most widely read narrative of the protest. Yet, a King-centered perspective of the Montgomery movement is misleading in ways that also distort understanding of the subsequent decade of southern African American struggles. As we approach the boycott's fiftieth anniversary, it is vital that we see what happened in Montgomery as a social justice struggle that was sustained by many grassroots leaders apart from King. Although King played a crucial role in transforming a local boycott into a social justice movement of international significance, he was himself transformed by a movement he did not initiate. Like other sustained mass movements, the Montgomery bus boycott should be understood as the outgrowth of a long history of activism by people from different educational backgrounds and economic classes. Unlike King, who had arrived in Montgomery little more than a year before Parks's arrest, nearly all the other key participants in the boycott were longtime residents. They were self-reliant NAACP stalwarts who acted on their own before King could lead.

The insights of contemporary social history and women's history have already revised popular perceptions of Rosa Parks, who is now more often seen as a veteran civil rights activist rather than a middle-aged seamstress with tired feet. Even before becoming secretary of Montgomery's NAACP branch during the 1940s, Parks'scommitment had been deepened by her husband Raymond's involvement during the 1930s in the campaign to free the “Scottsboro Boys”—nine black teenagers who faced the death penalty on trumped-up rape charges. A decade before she refused to obey the white bus driver's order to give up her seat, Parks had clashed with the same driver when she was required to re-enter through a rear door after paying at the front. During the summer of 1955, she attended the Highlander Folk School, a gathering place for organizers that was labeled a “Communist training school” by Tennessee officials. It was Parks who encouraged King to participate in the local branch of the NAACP soon after the young minister began preaching at Dexter Avenue Baptist Church.

After Parks was jailed on December 1, she got word to the person she thought was best prepared to help her: fifty-six year old E.D. Nixon, a veteran civil rights leader whose contributions to the rapid mobilization of Montgomery's black community can hardly be overstated. Nixon was not only an experienced NAACP leader but also a veteran official of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, the nation's largest predominantly-black union. Despite his limited formal education, Nixon was a dedicated civil rights proponent who became one of the MIA's links to northern supporters such as the Brotherhood's head, A. Philip Randolph. For most of the decade following World War II, Nixon worked closely with Parks—her secretarial skills complementing Nixon's forceful leadership. Faced with the task of getting Parks out of jail, Nixon realized that black attorney Fred Gray, who had assisted in previous civil rights cases, was temporarily out of town. Therefore, he called Clifford Durr, a white former New Dealer who had resigned from the Federal Communications Commissions during the late 1940s due to his opposition to cold war loyalty oaths. Durr's wife, Virginia, occasionally hired Parks to tailor clothes for the Durrs's daughter and had made arrangements for Parks's Highlander stay.

After Nixon accompanied the Durrs to Montgomery's jail and offered his home as bond to secure Parks's release, he began calling other black residents to discuss the possibility of launching a boycott to change bus seating policies. This idea did not spring spontaneously from Nixon's mind; instead, it had already been considered as a response to earlier incidents in which black bus riders were mistreated. On March 2, 1955, Claudette Colvin, a fifteen year old high school student, had been arrested for allegedly violating Montgomery's bus segregation ordinance. Nixon discussed launching a boycott with other leaders, including Gray and Jo Ann Robinson, the Alabama State College English professor who served as head of Montgomery's Women's Political Council (WPC). Although these leaders ultimately decided against trying to mobilize black residents on behalf of Colvin—in part because she became pregnant—awareness of Colvin's arrest and that of another teenaged resister, Mary Louis Smith, later in the year contributed to a sense of readiness for action among NAACP members. A brief 1953 bus boycott in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, also served as a stimulus for Montgomery residents considering how to respond to the indignities associated with segregation in public facilities.

Thus, a number of local residents were ready to move into action when Nixon telephoned them to urge that something should be done to protest Parks's arrest. Robinson was perhaps the most enthusiastic in supporting the boycott idea. Just after the Supreme Court's Brown v. Board of Education decision of May 1954, she had written a letter to city officials on behalf of the WPC warning of a bus boycott if bus segregation policies were not changed. During the evening after learning of Parks's arrest, Robinson spent most of the night at her Alabama State office working with two of her students to print thousands of leaflets, which her WPC colleagues helped to distribute, calling upon black residents to stay off buses on December 5.

Although planning for the boycott was already well underway by the time Nixon called King, the veteran activist the young minister at Dexter Church might make a special contribution. Though he was still only twenty-six years old and had become Dexter's pastor just a year earlier, King had already gained a reputation as a speaker and civil rights advocate. Upon accepting the call from Dexter, King had established a Social and Political Action Committee to keep the congregation politically informed and involved. Among those who volunteered for the committee were Robinson, WPC founder Mary Fair Burks, and Rufus Lewis, the former Alabama State football coach and funeral home owner who formed the Citizens Club in the late 1940s to encourage black voter registration and voting.

King's predecessor at Dexter, the outspoken and combative Vernon Johns, had warned King about the complacency of some Dexter members when the two met early in 1954 at the home of Ralph Abernathy, another young Baptist minister in Montgomery. Although King would soon form a more positive opinion of the Dexter congregation, he took to heart Johns's credo: “Any individual who submitted willingly to injustice did not really deserve more justice.” With encouragement from Abernathy, who became a lifelong friend, King soon established ties with NAACP activists in the region. In June 1955 he had accepted an invitation to address a mass meeting held by the Montgomery branch, and Parks herself was taking notes when he announced, “Jim Crow is on his deathbed but the battle is not won.” Parks and Nixon were encouraged when King argued against the “peril of complacency.” Parks soon afterwards conveyed an invitation to King to join the branch's executive committee ( 3 ).

By the fall of 1955 King had already received entreaties to consider running for branch president; thus, it was hardly surprising that some residents later were eager to involve him in the fledgling boycott. But King was initially hesitant. His first child had been born just weeks before Parks's arrest, and he and Coretta Scott King believed he needed to give more time to church work given that his doctoral dissertation had only recently been completed. King had gained widespread respect, however, due to his forceful civil rights advocacy. Nixon recognized that his own frequent travels as a train porter made him a poor candidate to direct a boycott, and he saw King as an articulate spokesman capable of standing up to white segregationists. “I always knowed that one day this fight would reach a point where better educated and better talkin' folks would have to take over if we is to succeed,” Nixon later told a friend. “That's how come I got my eyes set on this young Reverend Martin Luther King.”

When black leaders met on the afternoon of December 5 to form the Montgomery Improvement Association (MIA), the boycott effort had already succeeded in convincing almost all black riders to stay off the buses. Since King was a recent arrival in Montgomery, his emergence as a boycott leader required the intervention and support of others, including the person who nominated him—Rufus Lewis, a member of Dexter's Social and Political Committee. Lewis would later play an important role in organizing the car pool system that sustained the boycott.

That King did not initiate the boycott does not diminish his role in sustaining it through inspirational leadership that linked its goals with larger moral and democratic principles. With only twenty minutes to prepare his first major speech at the first MIA mass meeting, twenty-six year old King expressed these principles with remarkable eloquence: “If we are wrong, the Supreme Court of this nation is wrong. If we are wrong, the Constitution of the United States is wrong. If we are wrong, God Almighty is wrong. If we are wrong, Jesus of Nazareth was merely a Utopian dreamer that never came down to earth” ( 4 ).

But King's leadership involved more than inspiring oratory. His awareness of his own limitations and doubts provides a context for appreciating his courage and resilience. After repeated threats against his life and his family, King had a severe crisis of confidence late on the evening of January 27, 1956. He was able to continue only after a profound religious experience—“I experienced the presence of the Divine as I had never experienced Him before” ( 5 ).

A few days later, King admitted to a friend that he was “so busy that I hardly have time to breathe” but he also advised other boycott leaders that “if we went tonight and asked the people to get back on the bus, we would be ostracized. They wouldn't get back [on the buses].” He added that “my intimidations are a small price to pay if victory can be won” ( 6 ). During this period, however, King and other boycott participants remained united in maintaining that no individual was responsible for the protest. “The leaders could do nothing by themselves,” one woman commented. “They are only the voice of thousands of colored workers.” King himself remarked at an MIA rally, “I want you to know that if M. L. King had never been born this movement would have taken place” ( 7 ).

Even as King became an advocate of Gandhian principles of nonviolence, he realized that he was only one of many leaders of the Montgomery movement. In February 1956 Alabama officials indicted King and eighty-eight other MIA activists for violating a state law barring conspiracies to interfere with lawful businesses. King's trial took place the following month, and, before the other “conspirators” faced trial, his conviction was quickly appealed.

The ultimate success of the boycott resulted not only from the perseverance of MIA members but also from the determination of the lawyers who challenged segregated bus seating in the courts. Clifford Durr worked closely with black attorney Fred Gray to provide legal defense for Parks and later advised NAACP attorneys involved in the Browder v. Gayle (1956) case that struck down the legal basis for segregation on Montgomery's buses, achieving the boycott's objective. Claudette Colvin, the teenager whose initial act of defiance had spurred the boycott movement, was one of the plaintiffs in that suit. When King received word in November 1956 that the Supreme Court had ruled against bus segregation, the MIA was facing a court injunction that threatened to halt the MIA's car pools. “The darkest hour of our struggle had become the hour of victory,” King remembered ( 8 ).

As was the case on the first night of the boycott, King was best able to assess the boycott's historical significance as it came to an end. “Little did we know that we were starting a movement that would rise to international proportions,” he said as the MIA hosted a gathering of southern activists in December 1957. The Montgomery movement, King proclaimed, “would ring in the ears of people of every nation … would stagger and astound the imagination of the oppressor, while leaving a glittering star of hope etched in the midnight skies of the oppressed” ( 9 ).

Martin Luther King, Jr., “MIA Mass Meeting at Holt Street Baptist Church,” in Clayborne Carson et al., eds., The Papers of Martin Luther King, Jr., Volume III, Birth of a New Age, December 1966–December 1956 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997), 74.

Parks's minutes are quoted in Introduction, Carson, et al., eds., The Papers of Martin Luther King, Jr., Volume II: Rediscovering Precious Values, July 1951–November 1955 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1994), 36; Parks to King, August 26, 1955, in Papers II , 572.

Clayborne Carson and Kris Shepard, eds., A Call to Conscience: The Landmark Speeches of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. (New York: Warner Books, 2001), 18.

Clayborne Carson, ed., The Autobiography of Martin Luther King, Jr. (New York: Warner Books, 1998), 78.

King to H. Edward Whitaker, J anuary 30, 1956, and Notes on MIA Executive Board Meeting, by Donald T. Eerron, January 30, 1956, in Carson et al., eds., Papers III , 113, 110.

Notes on MIA Mass Meeting at Eirst Baptist Church, by Willie Mae Lee, January 30, 1956, in Carson et al., eds., Papers III , 114.

Carson, ed., Autobiography of Martin Luther King, Jr. , 94.

Martin Luther King, Jr., “Some Things We Must Do,” address delivered at Holt Street Baptist Church, December 5, 1957, in Clayborne Carson, et al., eds., The Papers of Martin Luther King, Jr., Volume IV: Symbol of the Movement, January 1957–December 1958 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000), 329.

Martin Luther King, Jr., and Coretta Scott King are in good spirits as they leave the court house in Montgomery, Alabama, on March 26, 1956, despite King's having been found guilty of conspiracy during the bus boycott. King appealed the verdict. (Image donated by Corbis-Bettman)

Following the successful boycott in Montgomery, Alabama, in 1955–1956, Martin Luther King, Jr., (left) sits next to Reverend Glenn Smiley of Texas on a Montgomery bus, symbolizing the victory. (Image donated by Corbis-Bettman.)

Email alerts

Citing articles via, affiliations.

- Online ISSN 1938-2340

- Print ISSN 0882-228X

- Copyright © 2024 Organization of American Historians

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

Home — Essay Samples — Social Issues — Montgomery Bus Boycott — How the Montgomery Bus Boycott Impacted the Civil Rights of the African-american

How The Montgomery Bus Boycott Impacted The Civil Rights of The African-american

- Categories: Montgomery Bus Boycott

About this sample

Words: 1464 |

Published: Jan 4, 2019

Words: 1464 | Pages: 3 | 8 min read

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Verified writer

- Expert in: Social Issues

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

4 pages / 1646 words

3 pages / 1521 words

3 pages / 1577 words

1 pages / 427 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Boycotting is to refuse to buy a product or participate in a pastime as a manner of expressing robust disapproval. For example, inn 1791, pamphlets were printed in support for the participation for boycotting sugar produced by [...]

A U.S. Supreme Court case in 1896, Plessy v. Ferguson is considered a landmark decision that upheld the legitimacy of racial segregation laws in public facilities in the U.S. emphasizing support on a legal constitutional [...]

The Arap Uprising/Spring refers to a series of popular uprisings in countries Arab occurred from 2010 to the present. Rated speed by the international press, the chain of conflicts began with the Tunisian revolution, in December [...]

Rosa Parks: My Story is an autobiography written by Rosa Parks herself alongside Jim Haskins, an African American author. It was dedicated to her mother, Leona McCauley, and her husband, Raymond A. Parks. Rosa Parks is mostly [...]