- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

Microsoft, Google, and a New Era of Antitrust

- Blair Levin

- Larry Downes

How businesses can navigate the increasing uncertainty around where and how antitrust law is enforced.

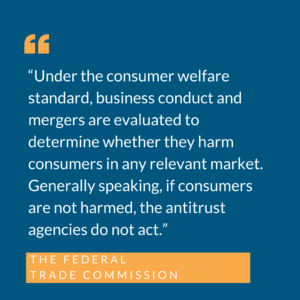

The U.S. federal government has brought major antitrust cases against Microsoft and Google. Regulators likely don’t expect to win either case outright, but the government doesn’t need to win these cases for them to have an impact. For one, an aggressive litigation strategy can provide a potent disruption to companies deemed too powerful. But these cases also send a message to European regulators, who have stepped into a leading role on antitrust. To navigate increasing uncertainty around where and how antitrust law is enforced, companies need to understand the complex politics of competing efforts to craft a new paradigm for competition law, and have plans in place for threading the needle and getting deals done.

In the last few months, the U.S. federal government has brought two major antitrust cases: one to block Microsoft’s acquisition of game developer Activision , and another against Google aimed at forcing the company to divest some of its advertising businesses. Along with the Federal Trade Commission’s failed effort to stop Meta’s acquisition of a virtual reality startup, an earlier federal case against Google regarding search, multiple ongoing state-level cases against the company, and reports the FTC will soon bring an action against Amazon, it appears that hunting season for large technology companies is in full swing.

- BL Blair Levin led the team that produced the FCC’s 2010 National Broadband Plan. He later founded Gig.U, which encouraged gigabit internet deployments in cities with major research universities. He is currently a Nonresident Senior Fellow with the Brookings Institution and Policy Advisor with New Street Research.

- Larry Downes is a co-author of Pivot to the Future: Discovering Value and Creating Growth in a Disrupted Worl d (PublicAffairs 2019). His earlier books include Big Bang Disruption , The Laws of Disruption , and Unleashing the Killer App .

Partner Center

Featured Topics

Featured series.

A series of random questions answered by Harvard experts.

Explore the Gazette

Read the latest.

More educated communities tend to be healthier. Why? Culture.

Lending a hand to a former student — Boston’s mayor

Where money isn’t cheap, misery follows

So what exactly is google accused of.

Google’s Chief Economist Hal Varian leaves after the first day of Google’s antitrust trial in Washington.

AP Photo/Nathan Howard

Christina Pazzanese

Harvard Staff Writer

Digital economy expert says much of antitrust case comes down to how much influence search giant wields on default setting on devices like phones, PCs

Federal prosecutors have accused Google of using its deep pockets and status as the dominant internet search engine to shut out rivals and stifle meaningful competition. That charge is now the focus of a trial that began Tuesday in U.S. District Court in Washington, D.C., a proceeding that could have a significant impact on the tech industry.

The Gazette spoke with economist Shane Greenstein , Martin Marshall Professor of Business Administration at Harvard Business School , about the complexities of the case. Greenstein has written about the commercial evolution of the internet and studies competition and economics in the digital economy. This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Shane Greenstein

GAZETTE: What is Google accused of doing, and why is this case getting so much attention?

GREENSTEIN: This is the most significant antitrust case brought by the DOJ since the late ’90s. Second, it’s not illegal to make money in the United States, and they’re not being sued for that reason. Sometimes you hear commentators say that, and that’s just wrong. It’s OK to be successful; it is also OK to be innovative. This is another one people sometimes say. They’re not being accused of being too innovative.

Antitrust law is principally interested in two things in this case. Has a firm achieved a certain level of success that can be characterized as a monopoly? Has the monopoly used its leading position in ways that abused the competitive process?

That’s very subtle. Let’s break it down: First, the government prosecutors must meet a legal standard for showing the firm has achieved a leading position. It has to prove by a lot that it established and maintained a monopoly. And as obvious as that might sound to some, that’s often where a lot of the legal fight is. Because if Google can define the market in such a way that they convince the judge that they’re in a very competitive setting and could lose market share at any time, a judge could say, “Well then, they don’t have a monopoly.”

If, on the other hand, the prosecution can persuade the judge that Google is in such a position so as not to be seriously worried about losing much market share to a competitor, then the monopoly can be sustained. That’s going to be the very first thing that gets litigated.

“The most recent numbers — 80 to 90 percent of just about everything in the U.S. has as its default the Google search engine.”

GAZETTE: Why has DOJ set its sights on Google rather than some other dominant tech firm?

GREENSTEIN: I absolutely understand why this case was brought. Once they achieved a leading position, did they take action that damaged the competitive process? It’s the actions they’re accused of taking. Google signs contracts for default settings with the distributors of phones and computers. It’s not everyone, but it’s the vast majority of device makers and distributors. The concern is that these contracts make it impossible for new entrants or too difficult for new entrants who might compete with Google to get their new services in front of users. That’s the accusation.

GAZETTE: Contracts that are exclusive or allegedly anti-competitive?

GREENSTEIN: Yes, anti-competitive. It concerns the details about the default. These contracts determine the defaults on systems when you buy them, like when you buy a PC or a smartphone, and what those defaults look like in the contracts. The most recent numbers — 80 to 90 percent of just about everything in the U.S. has as its default the Google search engine. In my opinion, the most problematic contracts are the ones with Apple.

GAZETTE: What are Google and DOJ likely to argue?

GREENSTEIN: Google will argue that these defaults make the user experience more seamless and less full of friction. A default has to be set. In almost all devices, search engines serve as a default for many applications. And so, if something has to be set and since they’re so popular, they’ll argue, “What’s wrong with having them as the default? People want that anyway. If they’re doing things to help users get what they want anyway, that’s not a violation of antitrust.” That’s more or less going to be their argument.

The Department of Justice is going to argue that the default contracts are too restrictive. They don’t give users options for choice. Users, when they’re making the decision for defaults, typically make them at the moment they acquire the device. And so, these contracts so discourage consideration for any other default that it makes it challenging, if not impossible, for an alternative to ever get a foothold and establish a market.

It’s a lot of contracts. There’s a contract with AT&T; there’s a contract with Verizon. There’s one with every Android user. The one with Apple is the one that has gotten the most publicity. I’ve got to agree — that’s the one that’s the most eyebrow-raising if you’re an antitrust enforcer.

The Apple iPhone in the United States — nobody is as dominant in the smartphone market. Its primary competitor is Android, which is sponsored by Alphabet, the parent company of Google. Apple has a contract with Alphabet to make its default search engine Google’s. This is the part that just worries most experts who look at this: Google pays Apple in proportion to the number of searches Google gets from those searches. The amount of money exchanging hands over time is huge.

It’s not only for smartphones; it’s also for the Apple PC. Last year, it’s something like $10 billion dollars, and most of that is for the iPhone.

GAZETTE: So, they’ve purportedly captured the smartphone market because they own Android operating system, and they’ve locked down iPhones via these contracts?

GREENSTEIN: Capture is too strong a word, to be fair. You can change the default on your smartphone. It’s not an easy thing to do. But think about it: Apple and Alphabet compete in the smartphone market and yet, here they are, exchanging money to change the design on a competitor’s product.

The most likely alternative to the Android design is Apple’s. That is very suspicious. Two competitors are exchanging and agreeing to have the same feature. That is not allowed in monopolized markets. This is the principle at stake here, and that’s why they’re being brought to court. Google’s response is that this helps users, and why shouldn’t we pay them, just like a product supplier pays a grocery store for placement of their products on shelves? And then they’ll have to show that it helps users. The DOJ is going to come back with “Had you not done this, Apple could have made their own search engine or entertained offers from others. The money changing hands is changing incentives.”

“Google will argue that these defaults make the user experience more seamless and less full of friction.”

GAZETTE: Some argue Microsoft never fully recovered its dominance or reputation after that court battle with DOJ. Could Google potentially face a similar fate?

More like this

Should we be worried about Amazon, Apple, Facebook, and Google?

Teaching algorithms about skin tones

On internet privacy, be very afraid

Riding the quantum computing ‘wave’

GREENSTEIN: That is a valid concern among several risks. A couple of things Google should worry about — one is bad publicity. Brands are extraordinarily valuable, and cases like this tend to damage brands a lot. That’s why I’m surprised Google agreed to go to court. I expected them to settle out of court because they’re putting their brand at risk. So is Apple, to some extent, and they’re not even named in the suit.

No. 2, there’s the contracts themselves, and the way business is done. It’s in a huge number of things they do, so if the court rules that Google cannot use these kinds of contracts, that’s a big change.

No. 3, damages are a risk. If the court says not only is it Google can’t use these contracts, but it prevented all this entry over the last X number of years, and that entry could have made this much difference, the court could come up with an estimate of the damages that’s enormous. The amount of money at stake is potentially mind-boggling.

GAZETTE: What kind of changes might Google users see?

GREENSTEIN: It might change the process the day you buy a smartphone; it might change the process every time you buy an Apple computer. That’s something you might see down the road. I don’t think you’re going to see anything like that in the next couple of months because this is going to take a long time.

GAZETTE: Meaning Google might no longer be the default search engine on their smartphones and laptops or that it could be pulled off entirely?

GREENSTEIN: You’d have options. That would happen all over the United States but not necessarily worldwide. This is another reason I was a little surprised Google allowed this to go to court. It’s going to make public a bunch of details and arguments that will make it easy for the European Union to potentially pass the administrative rules that accomplish similar ends. So, there are some risks here for Alphabet that are fairly substantial. And yet, they think they’ve got a good case.

GAZETTE: Does this case have potential ramifications for the technology industry as a whole?

GREENSTEIN: Yes. This issue about defaults has shown up in other cases where firms develop monopoly power. The Big Five, they all worry about the legality of their default settings. Among them, Amazon does a little bit; Facebook does a little bit. Apple certainly does. Apple has got to be watching this very closely in relation to apps. The investor community is watching to see if the leadership is distracted. That was allegedly true in the Microsoft case.

Also, these kinds of cases tend to bring to light many details about how business gets done. Some in the industry might have speculated about those details, but not had perfect information about them. So, the analyst and investor community are watching this closely just because they will learn important things. Certainly, I’m going to be reading about this every day. And, of course, investors care. Both Apple and Google are at risk here, directly and indirectly.

Share this article

You might like.

New study finds places with more college graduates tend to develop better lifestyle habits overall

Economist gathers group of Boston area academics to assess costs of creating tax incentives for developers to ease housing crunch

Student’s analysis of global attitudes called key contribution to research linking higher cost of borrowing to persistent consumer gloom

Epic science inside a cubic millimeter of brain

Researchers publish largest-ever dataset of neural connections

Good genes are nice, but joy is better

Harvard study, almost 80 years old, has proved that embracing community helps us live longer, and be happier

Finding right mix on campus speech policies

Legal, political scholars discuss balancing personal safety, constitutional rights, academic freedom amid roiling protests, cultural shifts

- Find a Lawyer

- Ask a Lawyer

- Research the Law

- Law Schools

- Laws & Regs

- Newsletters

- Justia Connect

- Pro Membership

- Basic Membership

- Justia Lawyer Directory

- Platinum Placements

- Gold Placements

- Justia Elevate

- Justia Amplify

- PPC Management

- Google Business Profile

- Social Media

- Justia Onward Blog

Antitrust Supreme Court Cases

Sometimes known as the Gilded Age, the late 19th century saw the rise of big business in the United States. “Titans of industry” accumulated vast wealth as their companies threatened to monopolize key sectors of the economy. Responding to this concern, Congress enacted the Sherman Antitrust Act in 1890. The Sherman Act sought to preserve competition in the market by forbidding monopolies and other business practices that restrain trade. Some restraints are blatantly anti-competitive, such as price fixing and market allocation. These are considered “per se” violations of the Sherman Act. Other alleged restraints are analyzed under the “rule of reason” to determine whether they unreasonably restrict trade.

In 1914, Congress passed the Federal Trade Commission Act. This created the FTC, which is the main federal agency in this area. The law also generally banned unfair methods of competition and unfair or deceptive acts or practices. Any conduct that violates the Sherman Act violates the Federal Trade Commission Act as well. Thus, while the FTC enforces only the Federal Trade Commission Act, the agency secures the protections provided by both laws.

Another notable antitrust law, also passed in 1914, is the Clayton Antitrust Act. This built on the Sherman Act by prohibiting certain practices that were not clearly covered by the earlier law. For example, Section 7 of the Clayton Act forbids mergers and acquisitions that harm competition or create a monopoly. The law also provides a private right of action based on violations of the Sherman Act or the Clayton Act. Individuals and businesses affected by a violation can sue for triple damages and seek an order against the unlawful practice.

Below is a selection of Supreme Court cases involving antitrust law, arranged from newest to oldest.

Author: Neil Gorsuch

The NCAA is not immune from the Sherman Act because its restrictions happen to fall at the intersection of higher education, sports, and money.

Author: Clarence Thomas

Evidence of a price increase on one side of a two-sided transaction platform cannot by itself demonstrate an anti-competitive exercise of market power.

Author: Anthony Kennedy

A non-sovereign actor controlled by active market participants enjoys state action antitrust immunity only if the challenged restraint is clearly articulated and affirmatively expressed as state policy, and the policy is actively supervised by the state.

Author: Stephen Breyer

Reverse payment settlement agreements in the pharmaceutical industry are not per se illegal but should be analyzed according to the rule of reason.

Author: John Paul Stevens

Each NFL team is a substantial, independently owned, and independently managed business, and the teams' objectives are not common. When the teams formed an entity to develop, license, and market their intellectual property, that entity's decisions about licensing the teams' separately owned intellectual property were concerted activity and covered by Section 1 of the Sherman Act.

Author: John Roberts

When there is no duty to deal at the wholesale level and no predatory pricing at the retail level, a firm is not required to price both of these services in a manner that preserves its rivals' profit margins.

Author: David Souter

A plaintiff must plead enough facts to state a claim to relief that is plausible on its face. More specifically, stating a claim under Section 1 of the Sherman Act requires a complaint with enough factual matter (taken as true) to suggest that an agreement was made. Asking for plausible grounds to infer an agreement calls for enough fact to raise a reasonable expectation that discovery will reveal evidence of an illegal agreement.

Vertical price restraints should be judged by the rule of reason.

A patent does not necessarily confer market power on the patentee. Therefore, in any case involving a tying arrangement, the plaintiff must prove that the defendant has market power in the tying product.

It is not per se illegal under Section 1 of the Sherman Act for a lawful, economically integrated joint venture to set the prices at which it sells its products.

Author: Antonin Scalia

There are few exceptions from the proposition that there is no duty to aid competitors.

An abbreviated or “quick look” analysis is appropriate when an observer with even a rudimentary understanding of economics could conclude that the arrangements in question have an anti-competitive effect on customers and markets.

When football team owners had bargained with the players' union over a wage issue until they reached an impasse, and the owners then agreed among themselves (but not with the union) to implement the terms of their own last best bargaining offer, federal labor laws shielded such an agreement from antitrust attack.

A claim of primary-line competitive injury under the Robinson-Patman Act has the same general character as a predatory pricing claim under Section 2 of the Sherman Act. In either case, a plaintiff must prove that the prices at issue are below an appropriate measure of its rival's costs, and the competitor had a reasonable prospect of recouping its investment in below-cost prices.

Author: Harry Blackmun

A defendant's lack of market power in the primary equipment market did not preclude, as a matter of law, the possibility of market power in derivative aftermarkets.

Author: Per Curiam

Agreements between competitors to allocate territories to minimize competition are illegal, regardless of whether the parties split a market within which they both do business or merely reserve one market for one and another for the other.

An agreement was not outside the coverage of the antitrust laws simply because its objective was the enactment of favorable legislation.

Author: Lewis Powell

To survive a motion for summary judgment, a plaintiff seeking damages for a violation of Section 1 of the Sherman Act must present evidence that tends to exclude the possibility that the alleged conspirators acted independently. Also, the absence of any plausible motive to engage in the conduct charged is highly relevant to whether a genuine issue for trial exists within the meaning of Rule 56(e) on summary judgment. Lack of motive bears on the range of permissible conclusions that might be drawn from ambiguous evidence.

Author: Byron White

Without a countervailing pro-competitive virtue, a horizontal agreement among members of a professional organization to withhold from their customers a particular service that they desire cannot be sustained under the rule of reason.

Author: William Brennan

A plaintiff seeking the application of the per se rule must present a threshold case that the challenged activity falls into a category likely to have predominantly anti-competitive effects.

Although even a firm with monopoly power has no general duty to engage in a joint marketing program with a competitor, the absence of an unqualified duty to cooperate does not mean that every time that a firm declines to participate in a particular cooperative venture, that decision may not have evidentiary significance or may not give rise to liability in certain circumstances.

A per se rule was not applied to an NCAA television plan that constituted horizontal price-fixing and output limitation, even though these restraints normally would be illegal per se, since this case involved an industry in which horizontal restraints on competition are essential if the product is to be available at all. (However, the plan still violated Section 1 of the Sherman Act under the rule of reason.)

Tying arrangements need only be condemned if they restrain competition on the merits by forcing purchases that would not otherwise be made. A lack of price or quality competition does not create this type of forcing.

Horizontal agreements to fix maximum prices are on the same legal footing as agreements to fix minimum or uniform prices. More specifically, maximum fee agreements between medical societies and member doctors are per se illegal as price-fixing agreements under Section 1 of the Sherman Act.

An agreement among competing wholesalers to refuse to sell unless the retailer makes payment in cash in advance or upon delivery is a form of price fixing and is plainly anti-competitive. Thus, it is conclusively presumed illegal without further examination under the rule of reason.

The issuance of blanket licenses by performance rights organizations does not constitute price fixing that is per se unlawful under the antitrust laws.

The rule of reason, under which the proper inquiry is whether the challenged agreement promotes or suppresses competition, does not support a defense based on the assumption that competition itself is unreasonable.

Author: Thurgood Marshall

For plaintiffs in an antitrust action to recover treble damages on account of violations of Section 7 of the Clayton Act, they must prove an injury of the type that the antitrust laws were intended to prevent and that flows from that which makes the defendants' acts unlawful. The injury must reflect the anti-competitive effect of either the violation or anti-competitive acts made possible by the violation.

When anti-competitive effects are shown to result from particular vertical restrictions, they can be adequately policed under the rule of reason. (This case concerned only non-price vertical restrictions.)

A scheme of allocating territories to minimize competition at the retail level was found to be a horizontal restraint constituting a per se violation.

The longstanding exemption of professional baseball from the antitrust laws is an established aberration in light of the Court's holding that other interstate professional sports are not similarly exempt. However, Congress has acquiesced in the exemption, and it is entitled to the benefit of stare decisis .

Author: Earl Warren

A merger must be functionally viewed in the context of its particular industry. Factors to consider include whether the consolidation will take place in an industry that is fragmented rather than concentrated, whether the industry has seen a recent trend toward domination by a few leaders or has remained consistent in its distribution of market shares, whether the industry has experienced easy access to markets by suppliers and easy access to suppliers by buyers or has witnessed foreclosure of business, and whether the industry has witnessed the ready entry of new competition or the erection of barriers to prospective entrants.

Author: Hugo Black

A group boycott is not to be tolerated merely because the victim is only one merchant, whose business is so small that their destruction makes little difference to the economy.

Author: Tom C. Clark

Championship boxing is the “cream” of the boxing business and is a sufficiently separate part of the trade or commerce to constitute the relevant market for Sherman Act purposes.

Author: Stanley Reed

The ultimate consideration in determining whether an alleged monopolist violates Section 2 of the Sherman Act is whether it controls prices and competition in the market for such part of trade or commerce as it is charged with monopolizing.

Author: Harold Hitz Burton

A single newspaper, already enjoying a substantial monopoly in its area, violates the “attempt to monopolize” clause of Section 2 of the Sherman Act when it uses its monopoly to destroy threatened competition.

Author: William O. Douglas

Vertical integration of producing, distributing, and exhibiting motion pictures is not illegal per se. Its legality depends on the purpose or intent with which it was conceived, or the power that it creates and the attendant purpose or intent.

A practice short of a complete monopoly that tends to create a monopoly and deprive the public of the advantages from free competition in interstate trade offends the policy of the Sherman Act.

Agreements to fix prices in interstate commerce are unlawful per se under the Sherman Act, and no showing of so-called competitive abuses or evils that the agreements were designed to eliminate or alleviate may be interposed as a defense.

Author: Harlan Fiske Stone

To establish an unlawful agreement to restrain commerce, the government can rely on inferences drawn from the course of conduct of the alleged conspirators.

Author: Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr.

The business of providing public baseball games for profit between clubs of professional baseball players is not within the scope of the federal antitrust laws.

Author: Louis Brandeis

The true test of legality is whether a restraint merely regulates and perhaps thereby promotes competition, or whether it may suppress or even destroy competition. To determine that question, a court must consider the facts peculiar to the business, its condition before and after the restraint was imposed, the nature of the restraint, and its effect, actual or probable. The history of the restraint, the evil believed to exist, the reason for adopting the particular remedy, and the purpose or end sought to be attained are all relevant facts.

Author: William Rufus Day

When, in this case, by concerted action, the names of wholesalers who were reported as having made sales to consumers were periodically reported to the other members of the associations, the conspiracy to accomplish that which was the natural consequence of such action could be readily inferred.

Author: Edward Douglass White

The public policy manifested by the Sherman Antitrust Act is expressed in such general language that it embraces every conceivable act that can possibly come within the spirit of its prohibitions, and that policy cannot be frustrated by resort to disguise or subterfuge.

The Sherman Antitrust Act should be construed in the light of reason. As so construed, it prohibits all contracts and combinations that amount to an unreasonable or undue restraint of trade in interstate commerce.

Author: Melville Weston Fuller

A combination may be in restraint of interstate trade and within the meaning of the Sherman Antitrust Act even when the persons exercising the restraint are not engaged in interstate trade, and some of the means employed are acts within a state and individually beyond the scope of federal authority.

Even if the separate elements of a scheme are lawful, when they are bound together by a common intent as parts of an unlawful scheme to monopolize interstate commerce, the plan may make the parts unlawful.

The monopoly and restraint denounced by the Sherman Antitrust Act are a monopoly in interstate and international trade or commerce, but not a monopoly in the manufacture of a necessity of life.

- Health Care

- Labor & Employment

- Consumer Protection

- Small Business

- Bankruptcy Lawyers

- Business Lawyers

- Criminal Lawyers

- Employment Lawyers

- Estate Planning Lawyers

- Family Lawyers

- Personal Injury Lawyers

- Estate Planning

- Personal Injury

- Business Formation

- Business Operations

- Intellectual Property

- International Trade

- Real Estate

- Financial Aid

- Course Outlines

- Law Journals

- US Constitution

- Regulations

- Supreme Court

- Circuit Courts

- District Courts

- Dockets & Filings

- State Constitutions

- State Codes

- State Case Law

- Legal Blogs

- Business Forms

- Product Recalls

- Justia Connect Membership

- Justia Premium Placements

- Justia Elevate (SEO, Websites)

- Justia Amplify (PPC, GBP)

- Testimonials

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

Understanding the state of antitrust enforcement in the United States

Ayesha Rascoe

NPR's Ayesha Rascoe talks with Rutgers University law professor Michael Carrier about the state of antitrust enforcement in the United States.

Copyright © 2023 NPR. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use and permissions pages at www.npr.org for further information.

NPR transcripts are created on a rush deadline by an NPR contractor. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of NPR’s programming is the audio record.

NCAA v. Alston

Comment on: 141 S. Ct. 2141 (2021)

- November 2021

- See full issue

In January of 2021, as the coronavirus pandemic reached its peak in the United States, Alabama Crimson Tide football coach Nick Saban won his seventh national collegiate championship. 1 For his efforts over the season, Saban was awarded a salary of $9.3 million, 2 itself a fraction of the more than $4 billion in revenue that college football generates each year. 3 Saban’s players, meanwhile, were eligible to receive the cost of attendance at the University of Alabama as compensation, which included “tuition and fees, room and board, books and other expenses related to attendance . . . .” 4 Last Term, in NCAA v. Alston , 5 the Supreme Court upheld a district court ruling that the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) rules limiting education-related compensation violated section 1 of the Sherman Act. 6 Shortly after the Court’s decision, the NCAA voted of its own accord to allow a student athlete to receive compensation in exchange for use of their name, image, and likeness (NIL). 7 Even after this series of changes, the NCAA still restricts the compensation that schools can provide directly to their athletes unrelated to education. 8 Although the student athletes did not challenge the remaining rules in the Supreme Court, the Alston decision, combined with background principles of antitrust law that the Court did not consider, lays the groundwork for a successful future challenge to the NCAA’s restrictions on compensation unrelated to education.

Although the NCAA generates roughly $1 billion in revenues each year, NCAA rules restrict student-athlete compensation. 9 Prior to Alston , the rules limited compensation to the cost of attendance, 10 meaning they served to restrict not only benefits unrelated to education, but also benefits tied to education, such as postgraduate scholarships, vocational school scholarships, expenses related to study abroad, and posteligibility internships. 11 These rules had largely escaped direct legal challenge since 1984, when the Supreme Court stated in NCAA v. Board of Regents of the University of Oklahoma 12 :

[T]he NCAA seeks to market a particular brand of football — college football. The identification of this “product” with an academic tradition differentiates college football from and makes it more popular than professional sports to which it might otherwise be comparable, such as, for example, minor league baseball. In order to preserve the character and quality of the “product,” athletes must not be paid , must be required to attend class, and the like. 13

In that case, several colleges challenged NCAA rules limiting the total number of football games that could be televised nationally, as well as the number of televised games that any single team could participate in 14 — restraints that applied to the consumer-side output market rather than the labor-side input market. The Court made the statement while explaining why these horizontal restraints on trade, which would ordinarily be held per se unlawful under the Sherman Act, are instead subject to the “rule of reason” test, in which courts conduct fact-specific analyses of the relevant market to determine whether there has been an antitrust violation. 15 In the decades after its decision, a circuit split emerged over whether the Court’s statement was binding precedent on the labor-side input market 16 or mere dicta. 17 This paved the way for Alston , which began in 2014 and 2015 when current and former Division I football and basketball players filed new challenges to the rules imposed by the NCAA and eleven of its conferences limiting the compensation that athletes may receive for their services. 18

The United States District Court for the Northern District of California held that limitations on education-related student-athlete benefits constituted unlawful restraints on trade under section 1 of the Sherman Act. 19 Because the court determined that “‘a certain degree of cooperation’ is necessary to market athletics competition,” 20 it applied the rule of reason balancing test to determine whether the rules violated the Sherman Act. 21 The rule of reason test contains three steps: first, the plaintiff must prove that the challenged restraint has a substantial anticompetitive effect; then, if the plaintiff succeeds, the burden shifts to the defendant to demonstrate the restraint results in procompetitive effects; finally, if the court finds procompetitive effects, the plaintiff must show the procompetitive benefit could be achieved through less restrictive means. 22

Although the court concluded that the rules limiting compensation do have the procompetitive effect of distinguishing collegiate athletics from professional athletics, it found that the NCAA could accomplish this effect through less restrictive means. 23 In particular, the district court concluded that education-related benefits, unlike benefits unrelated to education, are easily distinguishable from compensation paid to professional athletes. 24 Accordingly, the court left restrictions on payments unrelated to education undisturbed, while striking down limitations on education-related benefits. 25 At the same time, the decision left in place several limits on the newly permissible benefits, including that individual conferences can restrict education-related benefits even if the NCAA cannot. 26 Both parties appealed the decision. 27

The Ninth Circuit affirmed. 28 The NCAA limited its challenge to a narrow set of issues, including the district court’s application of the rule of reason’s second step. 29 The NCAA argued that the compensation restrictions were necessary to maintain the distinction between college and professional sports, thereby increasing consumer choice and enhancing competition. 30 The Ninth Circuit agreed with the district court, however, that only some of the restrictions — those on payments unrelated to education — served to enhance the distinction between college and professional athletics. 31 The NCAA also challenged the district court’s injunction as impermissibly vague, arguing that the relief would “usurp[] the association’s role as the ‘superintend[ent]’ of college sports.” 32 The Ninth Circuit again agreed with the district court, concluding that the district court “struck the right balance in crafting a remedy that both prevents anticompetitive harm to Student-Athletes while serving the procompetitive purpose of preserving the popularity of college sports.” 33 While the NCAA again appealed, the athletes did not appeal the court’s decision to leave non-education-related compensation limits intact. 34

The Supreme Court affirmed. 35 Writing for a unanimous Court, 36 Justice Gorsuch first concluded that the district court properly applied the rule of reason test rather than performing the quick review sometimes given to joint ventures. 37 Next, Justice Gorsuch agreed with the district court, and therefore the Ninth Circuit in O’Bannon v. NCAA , 38 that the Supreme Court’s opinion in Board of Regents did not create a binding precedent “reflexively” supporting the compensation rules. 39 As a final step in confirming that the rule of reason test applied, Justice Gorsuch agreed with the district court that the NCAA and its member schools are commercial enterprises subject to the Sherman Act. 40 Justice Gorsuch then reviewed the district court’s application of the rule of reason test. 41 Despite “agree[ing] with the NCAA’s premise that antitrust law does not require businesses to use anything like the least restrictive means of achieving legitimate business purposes,” 42 Justice Gorsuch ultimately viewed the district court’s analysis as in harmony with antitrust law, finding that “the district court nowhere — expressly or effectively — required the NCAA to show that its rules constituted the least restrictive means of preserving consumer demand.” 43 Justice Gorsuch also rejected the NCAA’s arguments regarding step three of the test, holding that the district court found permissible alternative rules that could deliver the same procompetitive effects without such burdensome restraints. 44 After agreeing with the district court’s application of the rule of reason test, Justice Gorsuch held that the district court’s injunction did not invite future courts to “micromanage” the NCAA, 45 but rather constituted a permissible antitrust remedy. 46

Justice Kavanaugh concurred to note that the NCAA’s remaining rules restricting non-education-related compensation, challenged in the district court but not appealed in the Supreme Court, raised serious antitrust questions as well. 47 Justice Kavanaugh emphasized three points: that the Supreme Court’s decision did not consider the legality of the non-education-related compensation rules, that the Court’s decision established that these rules would be analyzed under the rule of reason test, and that the Court’s decision raised serious questions about the legality of the remaining restraints under the rule of reason test. 48 In challenging the NCAA’s argument that maintaining compensation restrictions is necessary to distinguish college athletics from professional athletics, Justice Kavanaugh stated: “Businesses like the NCAA cannot avoid the consequences of price-fixing labor by incorporating price-fixed labor into the definition of the product.” 49 Although Justice Kavanaugh did suggest that the NCAA could protect itself from future judicial scrutiny by engaging in collective bargaining with student athletes, 50 he also flatly concluded that “[n]owhere else in America can businesses get away with agreeing not to pay their workers a fair market rate on the theory that their product is defined by not paying their workers a fair market rate. . . . The NCAA is not above the law.” 51

Although the Supreme Court did not have occasion to review the NCAA’s rules regarding compensation unrelated to education, its decision laid the groundwork for the dismantling of those rules in future proceedings. Prior to Alston , the Supreme Court had not definitively stated whether the NCAA’s compensation rules were subject to the rule of reason test under the Sherman Act; 52 now that the Court has clarified that they are, the remaining restrictions on compensation cannot pass scrutiny. Justice Kavanaugh’s concurrence already raised serious concerns about the legality of the remaining rules by arguing that the NCAA cannot justify restricting compensation “by calling it product definition.” 53 But neither Justice Kavanaugh’s concurrence nor the majority opinion analyzed a separate doctrinal hurdle for the NCAA: multimarket balancing. The NCAA’s justification for its remaining rules — that they enhance collegiate athletics by distinguishing them from professional sports — impermissibly balances harm in the labor-side market against benefits in the consumer-side market, benefits that do not accrue to the parties harmed by the challenged restraints (the student athletes). The NCAA’s sole justification for its remaining rules is therefore not a valid procompetitive justification and accordingly does not satisfy the second prong of the rule of reason test. Alston ’s subjecting the NCAA’s compensation rules to the rule of reason test, combined with the established impermissibility of multimarket balancing, therefore opens the door to further changes in the future of United States amateur athletics.

The second step of the rule of reason test requires the defendant to show that a procompetitive rationale exists that justifies the challenged restraint. 54 Only one procompetitive justification offered by the NCAA for its compensation rules survived the district court’s scrutiny 55 and was considered by the Supreme Court: that the rules preserve amateurism, which provides consumers a unique product distinct from paid professional sports. 56 The district court relied on this justification to leave in place the NCAA’s limitations on non-education-related benefits, stating that “[r]ules that prevent unlimited payments such as those observed in professional sports leagues, therefore, are procompetitive when compared to having no such restrictions.” 57 The district court erred, however, in allowing the NCAA to balance the potential procompetitive impact of the rules on the consumer-side output market against the anticompetitive restraints on trade in the labor-side market. 58

First, existing case law prohibits the district court’s decision to balance harms in the labor market against benefits in the consumer market. Although not in the Sherman Act context, the Supreme Court held while reviewing a merger in United States v. Philadelphia National Bank 59 that weighing procompetitive effects in one market with anticompetitive effects in another violates antitrust law. 60 Justice Brennan reasoned that “[i]f anticompetitive effects in one market could be justified by procompetitive consequences in another, the logical upshot would be that every firm in an industry could, without violating § 7, embark on a series of mergers that would make it in the end as large as the industry leader.” 61 Not long after, the Court confirmed in United States v. Topco Associates, Inc. 62 that this principle also applies to antitrust challenges brought under the Sherman Act. 63 In that case, Justice Marshall rejected the defendant’s attempt to justify its anticompetitive rules, stating that competition “cannot be foreclosed with respect to one sector of the economy because certain private citizens or groups believe that such foreclosure might promote greater competition in a more important sector of the economy.” 64 The Court has therefore made clear that its typical antitrust review does not allow for multimarket balancing.

Some scholars suggest, however, that the atypical nature of sports requires atypical antitrust review, and that multimarket balancing is a component of the necessary horizontal cooperation that the Supreme Court has held valid in the context of sports. 65 To be sure, in Board of Regents and other cases, the Court has stated that sports leagues have “a perfectly sensible justification for making a host of collective decisions,” including that otherwise competing teams have a collective “interest in making the entire league successful and profitable.” 66 In particular, the Court held in Brown v. Pro Football, Inc. 67 that professional leagues may exert monopsonistic buying power in the labor context. 68

Supreme Court cases analyzing the legality of professional sports league rules governing the player market have, however, held that antitrust law does not even apply. 69 In one of the first Court cases to approach this issue, Federal Baseball Club of Baltimore, Inc. v. National League of Professional Baseball Clubs , 70 the Court determined that professional baseball was exempt from antitrust scrutiny because “in order to attain for these exhibitions the great popularity that they have achieved, competitions must be arranged between clubs from different cities and States.” 71 Together, these decisions might have implied that, because horizontal restraints on trade are necessary to operate sports leagues, and because professional sports leagues may impose restraints on trade in the labor market exempt from antitrust scrutiny, the NCAA may impose horizontal restraints in the market for college-athlete labor.

The Court’s opinion in NCAA v. Alston opens the door to a different approach in the collegiate sports context. 72 First, the Court’s opinion establishes that, unlike in professional sports contexts, antitrust rules do apply to labor market rules in collegiate athletics. 73 The principal contribution of the Court’s decision was to make clear that the NCAA’s compensation rules are subject to Sherman Act scrutiny. 74 Once the Court holds that the rule of reason test applies, the burden shifts to the NCAA to offer a valid procompetitive justification for its rules. 75 As a result, the Court’s willingness to uphold horizontal restraints in professional sports contexts when it did not apply antitrust law does not require the Court to allow multimarket balancing once it has determined that antitrust law applies in the collegiate sports context.

Additionally, the compensation rules at issue in the Alston case are distinct from the horizontal cooperation upheld by the Court in other sports contexts. In Brown v. Pro Football, Inc ., professional football players challenged National Football League (NFL) rules establishing a “developmental squad” of substitute players with a fixed compensation of $1,000 per week. 76 Although the players alleged that this compensation cap violated the Sherman Act, the Supreme Court instead held that because the NFL imposed the plan after a failed effort to bargain with the players’ union, federal labor law shielded the NFL from antitrust scrutiny. 77 The NCAA, meanwhile, does not collectively bargain with its players, and therefore cannot claim that any dispute should instead be governed by labor law. 78 The lack of collective bargaining in the collegiate context is particularly important because it means that those harmed by the anticompetitive rules cannot negotiate to receive a portion of the benefit purportedly secured in the consumer market.

To be sure, if the NCAA were to engage in collective bargaining with its players, it might be able to receive more lenient treatment under antitrust law because student athletes, like professional athletes, would be able to negotiate for their fair share of the benefits coming from those labor market restraints. 79 For example, in some professional leagues, star athletes clearly earn less than their market value because the players have collectively agreed with the team owners that there should be a salary cap to ensure competitive balance. 80 But collective bargaining creates an avenue through which players can share in the benefits associated with that competitive balance, such as enhanced ticket sales and larger TV deals. If the NCAA similarly allowed student athletes to negotiate for their share of any procompetitive benefits, then the NCAA would be able to point to a procompetitive benefit in the labor market. However, absent such a change — one that might necessarily include waiving some of the compensation restrictions unrelated to education (since players would likely try to negotiate for such compensation as part of their collective bargaining) — the NCAA’s proffered procompetitive justification poses serious multimarket balancing problems.

Further supporting this objection’s seriousness, the Court did allude to multimarket balancing as a potential concern but tabled that argument only because the plaintiffs waived it. 81 Justice Gorsuch stated:

[T]he student-athletes do not question that the NCAA may permissibly seek to justify its restraints in the labor market by pointing to procompetitive effects they produce in the consumer market. Some amici argue that . . . review should instead be limited to the particular market in which antitrust plaintiffs have asserted their injury. But the parties before us do not pursue this line. 82

Elsewhere in the opinion, Justice Gorsuch commented on multimarket balancing with language suggesting that the objection is serious. Justice Gorsuch remarked that the asserted benefits of the rules “[a]dmittedly” accrue only to “consumers in the NCAA’s seller-side consumer market rather than to student-athletes whose compensation the NCAA fixes in its buyer-side labor market,” but that “the NCAA argued [that] the district court needed to assess its restraints in the labor market in light of their procompetitive benefits in the consumer market — and the district court agreed to do so.” 83 Finally, Justice Kavanaugh also alluded to the fact that the purported competitive benefits of the rules do not accrue to the student athletes, lamenting that the “enormous sums of money” that collegiate athletics generate “flow to seemingly everyone except the student athletes.” 84 The Court’s references to the fact that the NCAA’s multimarket balancing went unchallenged could suggest that it has reservations about such balancing; at the very least, the references suggest that the Court would invite a line of argument regarding the permissibility of multimarket balancing.

If student athletes do accept Justice Kavanaugh’s invitation to challenge the remaining rules, future courts need not worry that they must either allow for multimarket balancing or risk destroying college athletics. There are Sherman Act–compliant NCAA rules that distinguish collegiate athletes from their professional counterparts that do not rest on the fact that collegiate athletes are unpaid — most notably the requirement that collegiate athletes remain enrolled while they compete. 85 This rule better serves to distinguish collegiate athletes from professional athletes; while the casual observer may not be aware how much collegiate or professional athletes are compensated for their efforts on the field, college fans can, unlike professional fans, take pride in sitting next to the star player in English 101. In fact, the district court found that the NCAA did not “establish that the challenged compensation rules . . . have any direct connection to consumer demand.” 86

Justice Kavanaugh’s concurrence foreshadows that significant changes may still come to the NCAA’s compensation rules. Even the NCAA may agree; days after the Alston decision, the NCAA adopted its policy allowing student athletes to benefit from NIL opportunities, such as endorsement deals. 87 In just the first month after the policy was adopted, Coach Saban estimated that incoming star Alabama quarterback Bryce Young earned almost $1 million in endorsements. 88 Still, the NCAA seems intent on restricting non-education-related compensation, with Division II Presidents Council chair Sandra Jordan declaring: “The new policy preserves the fact college sports are not pay-for-play . . . .” 89 The Court’s decision in Alston , however, means that pay-for-play is likely on the NCAA’s one-yard line.

^ Alex Scarborough, Alabama Crimson Tide’s Nick Saban Claims Record Seventh National Championship , ESPN (Jan. 12, 2021), https://www.espn.com/college-football/story/_/id/30696121/alabama-crimson-tide-nick-saban-claims-record-seventh-national-championship [ https://perma.cc/M89F-ZX55 ].

^ Steve Berkowitz et al., NCAA Salaries , USA Today (Nov. 17, 2020), https://sports.usatoday.com/ncaa/salaries [ https://perma.cc/R39N-HN4M ].

^ See Rey Mashayekhi, The Financial Fallout of a Canceled College Football Season , Fortune (Aug. 10, 2020, 9:49 PM), https://fortune.com/2020/08/10/college-football-cancelled-2020-ncaa-financial-impact-revenue-schools-big-ten-sec-acc-big-12-pac-12 [ https://perma.cc/N82N-M68S ].

^ NCAA , Division I Manual 209 (2021), https://web3.ncaa.org/lsdbi/reports/getReport/90008 [ https://perma.cc/X3PS-K2JQ ]; see id . at 206–07.

^ 141 S. Ct. 2141 (2021).

^ See id . at 2151–52, 2166.

^ The Alston holding did not compel the NCAA’s NIL decision because the ruling left the NCAA’s rules limiting compensation unrelated to education undisturbed. See id . at 2165.

^ See O’Bannon v. NCAA, 802 F.3d 1049, 1052 (9th Cir. 2015).

^ See In re NCAA Athletic Grant-in-Aid Cap Antitrust Litig., 375 F. Supp. 3d 1058, 1071 (N.D. Cal. 2019).

^ Id . at 1088.

^ 468 U.S. 85 (1984).

^ Id . at 101–02 (emphasis added).

^ See id . at 94–96.

^ See id . at 101–03.

^ See McCormack v. NCAA, 845 F.2d 1338, 1345 (5th Cir. 1988) (holding that because the NCAA’s compensation rules did not violate antitrust laws, enforcement actions undertaken to uphold the rules were not an illegal group boycott). The Fifth Circuit relied on the Board of Regents decision to determine that the compensation rules were valid. Id . at 1344.

^ See O’Bannon v. NCAA, 802 F.3d 1049, 1075 (9th Cir. 2015) (holding that the NCAA’s rules limiting compensation below the full cost of attendance were more restrictive than necessary to serve the procompetitive goal of maintaining amateurism). The Ninth Circuit concluded that the Board of Regents discussion of amateurism was dicta. Id . at 1063.

^ See In re NCAA Athletic Grant-in-Aid Cap Antitrust Litig., 375 F. Supp. 3d 1058, 1061–62 (N.D. Cal. 2019). Cases brought by several plaintiffs were consolidated into a single case during pretrial proceedings. Id . at 1065 n.5.

^ 15 U.S.C. § 1; In re NCAA , 375 F. Supp. 3d at 1110.

^ In re NCAA , 375 F. Supp. 3d at 1066 (quoting O’Bannon , 802 F.3d. at 1069).

^ O’Bannon , 802 F.3d at 1070.

^ In re NCAA , 375 F. Supp. 3d at 1082–83.

^ Id . at 1083.

^ See id . at 1087–88.

^ Id . at 1090.

^ See In re NCAA Athletic Grant-in-Aid Cap Antitrust Litig., 958 F.3d 1239, 1243 (9th Cir. 2020).

^ Id . at 1244.

^ Id . at 1257.

^ Id . at 1263 (quoting O’Bannon v. NCAA, 802 F.3d 1049, 1074 (9th Cir. 2015)).

^ See Alston , 141 S. Ct. at 2154.

^ Id . at 2166.

^ Id . at 2147.

^ See id . at 2155. The Court assumed for the sake of its analysis that the NCAA correctly identified itself as a “joint venture.” Id . When the Court determines that the procompetitive effects flowing from restraints imposed by joint ventures are either nonexistent or necessary, or as the Court put it, “at opposite ends of the competitive spectrum,” the Court can determine the validity of the rules in the “twinkling of an eye.” Id . at 2155 (quoting NCAA v. Bd. of Regents of the Univ. of Okla., 468 U.S. 85, 109 n.39 (1984)); see id . at 2155–56.

^ 802 F.3d 1049, 1063 (9th Cir. 2015).

^ Alston , 141 S. Ct. at 2158.

^ Id . at 2158–59.

^ Id . at 2160.

^ Id . at 2161.

^ Id . at 2162; see id . at 2161–62.

^ See id . at 2164.

^ Id . at 2163 (quoting Brief for Petitioner at 50, Alston , 141 S. Ct. 2141 (No. 20-512)).

^ See id . at 2166.

^ See id . at 2166–67 (Kavanaugh, J., concurring).

^ See id . at 2166–68.

^ Id . at 2168.

^ Id . at 2169.

^ See id . at 2167.

^ See Ohio v. Am. Express Co., 138 S. Ct. 2274, 2284 (2018).

^ In re NCAA Athletic Grant-in-Aid Cap Antitrust Litig., 375 F. Supp. 3d 1058, 1062 (N.D. Cal. 2019).

^ Alston , 141 S. Ct. at 2152.

^ In re NCAA , 375 F. Supp. 3d at 1083.

^ See Alston , 141 S. Ct. at 2152.

^ 374 U.S. 321 (1963).

^ See id . at 370.

^ 405 U.S. 596 (1972).

^ See id . at 610. The defendant attempted to justify anticompetitive rules it had imposed in the buying market by pointing to its need to cooperate to compete in the consumer market. Id . at 598, 605.

^ Id . at 610.

^ See, e.g ., Gregory J. Werden, Cross-Market Balancing of Competitive Effects: What Is the Law, and What Should It Be? , 43 J. Corp. L . 119, 132 (2017).

^ Am. Needle, Inc. v. NFL, 560 U.S. 183, 202 (2010).

^ 518 U.S. 231 (1996).

^ See id . at 231.

^ See, e.g ., Fed. Baseball Club of Balt., Inc. v. Nat’l League of Pro. Baseball Clubs, 259 U.S. 200, 200 (1922) (holding that professional baseball is exempt from antitrust scrutiny).

^ 259 U.S. 200.

^ Id . at 208.

^ The Supreme Court has held that it will review different sports leagues in distinct manners. See Radovich v. NFL, 352 U.S. 445, 451 (1957) (“The Court was careful to restrict [ Toolson v. New York Yankees, Inc ., 346 U.S. 356 (1953)] to baseball . . . . ‘ Toolson is not authority for exempting other businesses merely because of the circumstance that they are also based on the performance of local exhibitions.’” (quoting United States v. Int’l Boxing Club of N.Y., Inc., 348 U.S. 236, 242 (1955))).

^ Prior to the Court’s decision, “legal analysis of the NCAA’s monopsony power remain[ed] underdeveloped due, in part, to [the] unfortunate dicta in Board of Regents .” Jeffrey L. Harrison & Casey C. Harrison, The Law and Economics of the NCAA’s Claim to Monopsony Rights , 54 Antitrust Bull . 923, 923–24 (2009).

^ See Alston , 141 S. Ct. at 2145.

^ Id . at 2160 (quoting Ohio v. Am. Express Co., 138 S. Ct. 2274, 2284 (2018)).

^ Brown v. Pro Football, Inc., 518 U.S. 231, 231 (1996).

^ See Alston , 141 S. Ct. at 2168 (Kavanaugh, J., concurring); Brown , 518 U.S. at 237.

^ Alston , 141 S. Ct. at 2168 (Kavanaugh, J., concurring).

^ See, e.g ., Brian Windhorst & Darren Rovell, How Much Would LeBron Make in an Open Market? Look to Ronaldo , ESPN (July 11, 2018), https://www.espn.com/nba/story/_/id/24062252/how-much-lebron-james-make-open-market-look-cristiano-ronaldo-nba [ https://perma.cc/YU8X-XJVE ].

^ See Alston , 141 S. Ct. at 2155.

^ Id . (citation omitted). The Court cited an amicus brief that argued courts should not engage in the policy-based exercise of “trad[ing]-off” competition in one market for competition in another. Brief for American Antitrust Institute as Amicus Curiae in Support of Respondents at 3, 11–12, Alston , 141 S. Ct. 2141 (Nos. 20-512, 20-520). This argument is made even stronger by the Court’s holding that the NCAA’s compensation rules are not exempt from antitrust scrutiny. Alston , 141 S. Ct. at 2145.

^ Id . at 2168 (Kavanaugh, J., concurring).

^ NCAA , supra note 4, at 165.

^ Michelle Brutlag Hosick, NCAA Adopts Interim Name, Image and Likeness Policy , NCAA (June 30, 2021), <a href="https://www.ncaa.org/about/resources/media-center/news/ncaa-adopts-interim-name-image-and-likeness-policy ">https://www.ncaa.org/about/resources/media-center/news/ncaa-adopts-interim-name-image-and-likeness-policy [ https://perma.cc/EMT3-3283 ].

^ Alex Scarborough, Alabama QB Bryce Young Approaching $1M in Endorsement Deals, Says Coach Nick Saban , ESPN (July 21, 2021, 11:45 AM), <a href="https://www.espn.com/college-football/story/_/id/31849917/alabama-qb-bryce-young-approaching-1m-endorsement-deals-says-head-coach-nick-saban ">https://www.espn.com/college-football/story/_/id/31849917/alabama-qb-bryce-young-approaching-1m-endorsement-deals-says-head-coach-nick-saban [ https://perma.cc/4688-R5QH ].

^ Hosick, supra note 87.

November 10, 2021

More from this Issue

Brnovich v. democratic national committee, the statistics.

- James Mulhern

Antitrust Law

The authors would like to thank Peter Carstensen, Bert Foer, Gene Kimmelman, Jack Kirkwood, Ganesh Sitaraman, Sandeep Vaheesan, Spencer Weber Waller, and participants in the April 2018 Roosevelt Institute Twenty-First Century Antitrust Conference for their helpful comments.

2 Article 87.2 What’s in Your Wallet (and What Should the Law Do About It?) Natasha Sarin Assistant Professor of Law, the University of Pennsylvania Carey Law School; Assistant Professor of Finance, the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania.

I thank participants at the Symposium and in the Work-in-Progress Workshop at the Law School for comments and the Jerome F. Kutak Faculty Fund for its generous research support

We thank William Blumenthal, C. Frederick Beckner III, and the participants in the Law Review’s May 2019 Symposium on Reassessing the Chicago School of Antitrust for their helpful comments, as well as Dylan Naegele for his able research assistance.

The author is grateful for comments from Andrew Gavil, participants at The University of Chicago Law Review’s annual symposium, and workshops at King’s College London and University College London. The author also thanks the staff of The University of Chicago Law Review for their excellent editorial guidance. The views expressed here are the author’s alone. Email: [email protected] .

The Chicago School, said to have influenced antitrust analysis inescapably, is associated today with a set of ideas and arguments about the goal of antitrust law. In particular, the Chicago School is known for asserting that economic efficiency is and should be the only purpose of antitrust law and that the neoclassical price theory model offers the best policy tool for maximizing economic efficiency in the real world; that corporate actions, including various vertical restraints, are efficient and welfare-increasing; that markets are self-correcting and monopoly is merely an occasional, unstable, and transitory outcome of the competitive process; and that governmental cures for the rare cases where markets fail to self-correct tend to be “worse than the disease.”

I am deeply grateful to Eric Posner, Sanjukta Paul, Brian Callaci, and the participants of the Reassessing the Chicago School of Antitrust Law Symposium for their helpful comments and suggestions.

For thoughtful engagement and comments, we are grateful to Scott Hemphill, William Kovacic, Fiona Scott Morton, Nancy Rose, Jonathan Sallet, Carl Shapiro, Sandeep Vaheesan, and Joshua Wright, as well as staff at the FTC and participants in the Symposium on Reassessing the Chicago School of Antitrust Law at The University of Chicago Law School. We also thank the editors of The University of Chicago Law Review for careful editing.

Open, competitive markets are a foundation of economic liberty. A lack of competition, meanwhile, can enable dominant firms to exercise their market power in harmful ways.

High tech industries are not only lucrative, but also highly innovative and dynamic. Large firms are not their sole source of innovation, however.

This Essay was prepared for the symposium organized by The University of Chicago Law Review on Reassessing the Chicago School of Antitrust Law, held on May 10–11, 2019. We thank the participants of the symposium for helpful feedback. Special thanks also to Patrick Todd for illuminating conversations. We are indebted to the over one hundred research assistants at Columbia Law School and The University of Chicago Law School that helped us gather and code the antitrust data we employ in this Essay. Our thanks also to the antitrust enforcers in the 103 agencies that generously provided information for this study. We gratefully acknowledge the funding by the National Science Foundation that supported the early data gathering effort (see NSF-Law & Social Sciences grants 1228453 & 1228483, awarded in September 2012). The coding was subsequently expanded with the generous support of the Columbia Public Policy Grant: “Does Antitrust Policy Promote Market Performance and Competitiveness?,” awarded in June 2015, and additional financial support from Columbia Law School. We also thank the Baker Scholars fund at The University of Chicago Law School for financial support. Except as otherwise noted, all data is available at the Comparative Competition Law Project website, http://comparativecompetitionlaw.org .

- Volume 91.3 May 2024

- Volume 91.2 March 2024

- Volume 91.1 January 2024

- Volume 90.8 December 2023

- Volume 90.7 November 2023

- Volume 90.6 October 2023

- Volume 90.5 September 2023

- Volume 90.4 June 2023

- Volume 90.3 May 2023

- Volume 90.2 March 2023

- Volume 90.1 January 2023

- Volume 89.8 December 2022

- Volume 89.7 November 2022

- Volume 89.6 October 2022

- Volume 89.5 September 2022

- Volume 89.4 June 2022

- Volume 89.3 May 2022

- Volume 89.2 March 2022

- Volume 89.1 January 2022

- 84 Special November 2017

- Online 83 Presidential Politics and the 113th Justice

- Online 82 Grassroots Innovation & Regulatory Adaptation

- 83.4 Fall 2016

- 83.3 Summer 2016

- 83.2 Spring 2016

- 83.1 Winter 2016

- 82.4 Fall 2015

- 82.3 Summer 2015

- 82.2 Spring 2015

- 82.1 Winter 2015

- 81.4 Fall 2014

- 81.3 Summer 2014

- 81.2 Spring 2014

- 81.1 Winter 2014

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

DealBook Newsletter

What Did Google Do?

What you need to know about the antitrust case against the tech giant.

By Andrew Ross Sorkin , Jason Karaian , Michael J. de la Merced , Lauren Hirsch and Ephrat Livni

This Nov. 17 and 18, DealBook opens its doors to our first Online Summit . Join us as we welcome the most consequential newsmakers in business, policy and culture to explore the pivotal questions of the moment — and the future. Watch from anywhere in the world, free of charge. Register now .

What you need to know about the Google case

The Department of Justice has filed its long-awaited antitrust lawsuit against Google, “the government’s most significant legal challenge to a tech company’s market power in a generation,” according to The New York Times’s David McCabe, Cecilia Kang and Dai Wakabayashi . It’s big, complicated and could take years to resolve — here’s the state of play:

The lawsuit targets the “cornerstones of Google’s empire,” its search tools. The Justice Department alleges that Google illegally protects a monopoly in search that harms competitors and consumers. Google pays companies like Apple billions of dollars to make its search engine the default option on their devices, shutting out rivals. Google then uses this grip to collect data from users that gives its search-based advertising business an unfair advantage, too.

More competition from other search engines, the Justice Department asserts, would force Google to compete on grounds that would promote better consumer protections in the digital age.

What the Justice Department said: Google “has maintained its monopoly power through exclusionary practices that are harmful to competition,” the deputy U.S. attorney general Jeffrey Rosen said at a news conference . You can read the government’s full case here .

How Google responded: “People use Google because they choose to, not because they’re forced to, or because they can’t find alternatives,” wrote Kent Walker, the company’s chief legal officer, in a lengthy blog post .

What others are thinking: “Some might try to characterize today’s filing as a partisan vendetta by the Trump administration. That is the false narrative Google wants you to hear,” said Luther Lowe , senior vice president of public policy at Yelp. “The case is clear — in fact, it could have gone further,” said Senator Elizabeth Warren . Many other business leaders, policymakers and antitrust experts have weighed in .

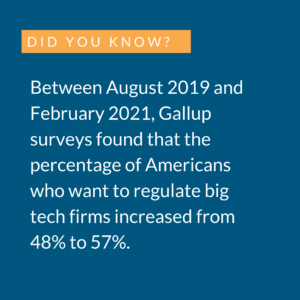

The questions that remain

A better question might be, “This again?” The F.T.C. conducted a two-year antitrust investigation into Google under President Barack Obama, which went nowhere. Bill Barr, the attorney general, pushed hard to bring this new case before the election, but even if Democrats take the White House, experts say that it is unlikely to be withdrawn — some staff attorneys at the Justice Department have taken issue with how quickly it was filed, but they still consider the evidence solid . Critics argue that antitrust regulators rely on an outdated legal framework unsuited to deal with tech giants, but as these companies’ power has grown, so too has bipartisan unease .

How long will it take?

“This legal case is going to be loud, confusing and will most likely drag on for years,” writes The Times’s Shira Ovide . And a bipartisan coalition of attorneys general from states including New York, Colorado and Iowa said yesterday that they would conclude their own probe into Google “in the coming weeks.” European antitrust regulators sued Google in 2015 based on similar facts, and settled in 2018. The U.S. Justice Department’s landmark antitrust case against Microsoft was filed in 1998 and settled in 2001.

Is this like the Microsoft case?

Yes, but not exactly. Google is charged with monopolizing search by using restrictive and exclusive deals, like Microsoft’s bundling of software programs with its operating system. Microsoft comes up a lot in the Google case, in fact: “Back then, Google claimed Microsoft’s practices were anticompetitive, and yet, now, Google deploys the same playbook to sustain its own monopolies,” the suit accuses.

Google says that other companies, including Microsoft, control prime mobile and desktop space, so it negotiates for “eye-level shelf space” to place its products like a cereal brand would with supermarkets.

Will Google get broken up?

“Nothing is off the table,” said the associate deputy attorney general Ryan Shores. A trial judge ordered a breakup in the Microsoft case, but an appeals court perceived bias in the decision and the Justice Department eventually settled the case. The E.U. has generally eschewed breakups as a remedy — it settled its antitrust case against Google for abusing its power in the mobile phone market with a fine and behavioral changes that critics say haven’t been effective . A recent House report accused Facebook, Google, Amazon and Apple of various monopoly strategies, but it didn’t call for breakups.

Whatever the outcome, investors don’t seem worried: Shares in Google’s parent, Alphabet, rose yesterday, and are also up in premarket trading today. BCA Research ran the numbers on past antitrust cases and found that companies forced to break up outperformed the market after the judgments:

Could Google just pay to make this go away?

With more than $120 billion in cash and an army of lawyers, it has the power to drag this out for a long time if it wants to. Or it could dip into the funds to settle the case with a fine and some promises to behave differently. State attorneys general fear this sort of anticlimactic ending, which is part of why they’re filing separate suits, giving them leverage to move independently if they think the Justice Department might settle too soon or too leniently.

Further reading:

The legal fight thrusts Sundar Pichai, Alphabet’s low-key C.E.O., into the line of fire

Google is up against laws that thwarted Microsoft — and others since 1890

“ It’s Google’s World. We Just Live in It .”

Today’s DealBook newsletter was written by Andrew Ross Sorkin and Lauren Hirsch in New York, Ephrat Livni in Washington, and Michael J. de la Merced and Jason Karaian in London.

HERE’S WHAT’S HAPPENING

The stimulus drama drags on. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi said she hoped to reach an agreement with the White House by the end of the week, and is expected to speak again with Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin today. But Senator Mitch McConnell, the majority leader, told colleagues he had advised the Trump administration not to strike a deal before the election. Separately: Why the Fed’s $4 trillion lifeline never materialized .

Revelations about President Trump’s business ties to China. A Trump-owned company controls a previously undisclosed Chinese bank account, according to a Times analysis of the president’s financial records. It highlights his family’s efforts to win business there, even after he took office.

British scientists plan to deliberately infect volunteers with the coronavirus. The testing strategy, known as a human challenge trial , is meant to speed up testing of vaccines. But using it in this context has spurred debate, given that Covid-19 has no cure and few widely used treatments. Also on vaccine development, here’s how the F.D.A. stood up to the White House on the approval timeline.

Leon Black asks Apollo’s board to examine his ties to Jeffrey Epstein. Mr. Black requested the review , which will be conducted by the law firm Dechert, after The Times reported on at least $50 million in payments he made to entities controlled by the financier and sex offender, who died last year. In other news, a federal judge said that the deposition transcripts of the Epstein associate Ghislaine Maxwell should be made public .

Chinese tech giants try to thwart Nvidia’s deal to buy ARM. Companies like Huawei have reportedly urged regulators in Beijing to block the $40 billion acquisition of the chip designer, Bloomberg reports . It’s the latest potential regulatory roadblock for the blockbuster transaction.

The latest on Goldman’s legal headaches

An Asian subsidiary of Goldman Sachs plans to plead guilty to settle a U.S. investigation into the company’s role in a corruption and bribery scandal involving 1MDB, a Malaysian investment fund, The Times’s Matt Goldstein reports .

It would be the first time Goldman had pleaded guilty in a federal investigation. The bank’s parent company would admit mistakes in its dealings with the fund, which has been accused of stealing money for powerful Malaysians, including a former prime minister. But it has avoided having to make a guilty plea at the parent-company level, which could have hurt its ability to work with clients like pension funds. Still, the facts of the case will challenge the firm’s contention that rogue employees participated in the 1MDB schemes without approval.

The firm will pay over $2 billion in penalties to the U.S. authorities, on top of the $2.5 billion that it agreed to settle an investigation by the Malaysian government a few months ago.

Goldman’s legal troubles aren’t over. A federal magistrate judge ruled yesterday that its former C.E.O. Lloyd Blankfein and former president Gary Cohn must testify in a gender-discrimination lawsuit filed by former employees, one of the biggest such cases in Wall Street history. Goldman’s current C.E.O., David Solomon, may also have to testify.

Netflix’s pandemic bump is over

Business is good, just not as good as investors thought. The streaming giant reported 2.2 million new memberships for the third quarter, about one million lower than expected, and said that subscriptions for the fourth quarter would be lower than analysts’ estimates, too. But thanks to its subscription surge earlier in the pandemic, Netflix expects to close the year with a record number of new members, about 34 million, giving it just over 200 million subscribers around the world.

Deal Professor: Waiting for the wave

Steven Davidoff Solomon , a.k.a. the Deal Professor, is a professor at the U.C. Berkeley School of Law and the faculty co-director at the Berkeley Center for Law, Business and the Economy.

The long-predicted tidal wave of coronavirus-driven corporate bankruptcies has yet to arrive.

To be sure, the pandemic has pushed some famous names into Chapter 11, including Chuck E. Cheese, J.C. Penney and Neiman Marcus. S&P Global Market Intelligence says that 527 companies with public debt have filed for bankruptcy so far this year, more — but not that much more — than the 477 that filed over the same period last year. It also notes that the weekly totals have been slowing recently.

What happened?

While the coronavirus recession has pushed many companies over the edge, many of these were already embattled, from oil and gas drillers like Chesapeake Energy to retailers like Neiman Marcus. And others forced into Chapter 11, including the rental-car company Hertz and the circus operator Cirque du Soleil, were struggling under big debt loads.

There are other factors:

Many parts of the U.S. remain open, keeping economic activity up.

Markets are still awash in liquidity, giving many companies access to sorely needed financing. And interest rates are so low that the risk of taking on too much debt is reduced.

The private sector has adapted remarkably well to the new normal. While many restaurants have been devastated, others are thriving on takeout. And even movie theaters, which are clearly on the brink, are at least beginning to rent out their venues for private screenings.

The pandemic will force more bankruptcy filings, particularly if a vaccine is delayed. And S&P does not track bankruptcies of smaller businesses, which have suffered more, particularly in states with tougher lockdowns.

But let’s be clear: That flood of huge bankruptcies? It’s probably never coming.

THE SPEED READ