Global Education

By: Hannah Ritchie , Veronika Samborska , Natasha Ahuja , Esteban Ortiz-Ospina and Max Roser

A good education offers individuals the opportunity to lead richer, more interesting lives. At a societal level, it creates opportunities for humanity to solve its pressing problems.

The world has gone through a dramatic transition over the last few centuries, from one where very few had any basic education to one where most people do. This is not only reflected in the inputs to education – enrollment and attendance – but also in outcomes, where literacy rates have greatly improved.

Getting children into school is also not enough. What they learn matters. There are large differences in educational outcomes : in low-income countries, most children cannot read by the end of primary school. These inequalities in education exacerbate poverty and existing inequalities in global incomes .

On this page, you can find all of our writing and data on global education.

Key insights on Global Education

The world has made substantial progress in increasing basic levels of education.

Access to education is now seen as a fundamental right – in many cases, it’s the government’s duty to provide it.

But formal education is a very recent phenomenon. In the chart, we see the share of the adult population – those older than 15 – that has received some basic education and those who haven’t.

In the early 1800s, fewer than 1 in 5 adults had some basic education. Education was a luxury; in all places, it was only available to a small elite.

But you can see that this share has grown dramatically, such that this ratio is now reversed. Less than 1 in 5 adults has not received any formal education.

This is reflected in literacy data , too: 200 years ago, very few could read and write. Now most adults have basic literacy skills.

What you should know about this data

- Basic education is defined as receiving some kind of formal primary, secondary, or tertiary (post-secondary) education.

- This indicator does not tell us how long a person received formal education. They could have received a full program of schooling, or may only have been in attendance for a short period. To account for such differences, researchers measure the mean years of schooling or the expected years of schooling .

Despite being in school, many children learn very little

International statistics often focus on attendance as the marker of educational progress.

However, being in school does not guarantee that a child receives high-quality education. In fact, in many countries, the data shows that children learn very little.

Just half – 48% – of the world’s children can read with comprehension by the end of primary school. It’s based on data collected over a 9-year period, with 2016 as the average year of collection.

This is shown in the chart, where we plot averages across countries with different income levels. 1

The situation in low-income countries is incredibly worrying, with 90% of children unable to read by that age.

This can be improved – even among high-income countries. The best-performing countries have rates as low as 2%. That’s more than four times lower than the average across high-income countries.

Making sure that every child gets to go to school is essential. But the world also needs to focus on what children learn once they’re in the classroom.

Millions of children learn only very little. How can the world provide a better education to the next generation?

Research suggests that many children – especially in the world’s poorest countries – learn only very little in school. What can we do to improve this?

- This data does not capture total literacy over someone’s lifetime. Many children will learn to read eventually, even if they cannot read by the end of primary school. However, this means they are in a constant state of “catching up” and will leave formal education far behind where they could be.

Children across the world receive very different amounts of quality learning

There are still significant inequalities in the amount of education children get across the world.

This can be measured as the total number of years that children spend in school. However, researchers can also adjust for the quality of education to estimate how many years of quality learning they receive. This is done using an indicator called “learning-adjusted years of schooling”.

On the map, you see vast differences across the world.

In many of the world’s poorest countries, children receive less than three years of learning-adjusted schooling. In most rich countries, this is more than 10 years.

Across most countries in South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa – where the largest share of children live – the average years of quality schooling are less than 7.

- Learning-adjusted years of schooling merge the quantity and quality of education into one metric, accounting for the fact that similar durations of schooling can yield different learning outcomes.

- Learning-adjusted years is computed by adjusting the expected years of school based on the quality of learning, as measured by the harmonized test scores from various international student achievement testing programs. The adjustment involves multiplying the expected years of school by the ratio of the most recent harmonized test score to 625. Here, 625 signifies advanced attainment on the TIMSS (Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study) test, with 300 representing minimal attainment. These scores are measured in TIMSS-equivalent units.

Hundreds of millions of children worldwide do not go to school

While most children worldwide get the opportunity to go to school, hundreds of millions still don’t.

In the chart, we see the number of children who aren’t in school across primary and secondary education.

This number was around 260 million in 2019.

Many children who attend primary school drop out and do not attend secondary school. That means many more children or adolescents are missing from secondary school than primary education.

Access to basic education: almost 60 million children of primary school age are not in school

The world has made a lot of progress in recent generations, but millions of children are still not in school.

The gender gap in school attendance has closed across most of the world

Globally, until recently, boys were more likely to attend school than girls. The world has focused on closing this gap to ensure every child gets the opportunity to go to school.

Today, these gender gaps have largely disappeared. In the chart, we see the difference in the global enrollment rates for primary, secondary, and tertiary (post-secondary) education. The share of children who complete primary school is also shown.

We see these lines converging over time, and recently they met: rates between boys and girls are the same.

For tertiary education, young women are now more likely than young men to be enrolled.

While the differences are small globally, there are some countries where the differences are still large: girls in Afghanistan, for example, are much less likely to go to school than boys.

Research & Writing

Talent is everywhere, opportunity is not. We are all losing out because of this.

Access to basic education: almost 60 million children of primary school age are not in school, interactive charts on global education.

This data comes from a paper by João Pedro Azevedo et al.

João Pedro Azevedo, Diana Goldemberg, Silvia Montoya, Reema Nayar, Halsey Rogers, Jaime Saavedra, Brian William Stacy (2021) – “ Will Every Child Be Able to Read by 2030? Why Eliminating Learning Poverty Will Be Harder Than You Think, and What to Do About It .” World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 9588, March 2021.

Cite this work

Our articles and data visualizations rely on work from many different people and organizations. When citing this topic page, please also cite the underlying data sources. This topic page can be cited as:

BibTeX citation

Reuse this work freely

All visualizations, data, and code produced by Our World in Data are completely open access under the Creative Commons BY license . You have the permission to use, distribute, and reproduce these in any medium, provided the source and authors are credited.

The data produced by third parties and made available by Our World in Data is subject to the license terms from the original third-party authors. We will always indicate the original source of the data in our documentation, so you should always check the license of any such third-party data before use and redistribution.

All of our charts can be embedded in any site.

Our World in Data is free and accessible for everyone.

Help us do this work by making a donation.

The World Bank Group is the largest financier of education in the developing world, working in 94 countries and committed to helping them reach SDG4: access to inclusive and equitable quality education and lifelong learning opportunities for all by 2030.

Education is a human right, a powerful driver of development, and one of the strongest instruments for reducing poverty and improving health, gender equality, peace, and stability. It delivers large, consistent returns in terms of income, and is the most important factor to ensure equity and inclusion.

For individuals, education promotes employment, earnings, health, and poverty reduction. Globally, there is a 9% increase in hourly earnings for every extra year of schooling . For societies, it drives long-term economic growth, spurs innovation, strengthens institutions, and fosters social cohesion. Education is further a powerful catalyst to climate action through widespread behavior change and skilling for green transitions.

Developing countries have made tremendous progress in getting children into the classroom and more children worldwide are now in school. But learning is not guaranteed, as the 2018 World Development Report (WDR) stressed.

Making smart and effective investments in people’s education is critical for developing the human capital that will end extreme poverty. At the core of this strategy is the need to tackle the learning crisis, put an end to Learning Poverty , and help youth acquire the advanced cognitive, socioemotional, technical and digital skills they need to succeed in today’s world.

In low- and middle-income countries, the share of children living in Learning Poverty (that is, the proportion of 10-year-old children that are unable to read and understand a short age-appropriate text) increased from 57% before the pandemic to an estimated 70% in 2022.

However, learning is in crisis. More than 70 million more people were pushed into poverty during the COVID pandemic, a billion children lost a year of school , and three years later the learning losses suffered have not been recouped . If a child cannot read with comprehension by age 10, they are unlikely to become fluent readers. They will fail to thrive later in school and will be unable to power their careers and economies once they leave school.

The effects of the pandemic are expected to be long-lasting. Analysis has already revealed deep losses, with international reading scores declining from 2016 to 2021 by more than a year of schooling. These losses may translate to a 0.68 percentage point in global GDP growth. The staggering effects of school closures reach beyond learning. This generation of children could lose a combined total of US$21 trillion in lifetime earnings in present value or the equivalent of 17% of today’s global GDP – a sharp rise from the 2021 estimate of a US$17 trillion loss.

Action is urgently needed now – business as usual will not suffice to heal the scars of the pandemic and will not accelerate progress enough to meet the ambitions of SDG 4. We are urging governments to implement ambitious and aggressive Learning Acceleration Programs to get children back to school, recover lost learning, and advance progress by building better, more equitable and resilient education systems.

Last Updated: Mar 25, 2024

The World Bank’s global education strategy is centered on ensuring learning happens – for everyone, everywhere. Our vision is to ensure that everyone can achieve her or his full potential with access to a quality education and lifelong learning. To reach this, we are helping countries build foundational skills like literacy, numeracy, and socioemotional skills – the building blocks for all other learning. From early childhood to tertiary education and beyond – we help children and youth acquire the skills they need to thrive in school, the labor market and throughout their lives.

Investing in the world’s most precious resource – people – is paramount to ending poverty on a livable planet. Our experience across more than 100 countries bears out this robust connection between human capital, quality of life, and economic growth: when countries strategically invest in people and the systems designed to protect and build human capital at scale, they unlock the wealth of nations and the potential of everyone.

Building on this, the World Bank supports resilient, equitable, and inclusive education systems that ensure learning happens for everyone. We do this by generating and disseminating evidence, ensuring alignment with policymaking processes, and bridging the gap between research and practice.

The World Bank is the largest source of external financing for education in developing countries, with a portfolio of about $26 billion in 94 countries including IBRD, IDA and Recipient-Executed Trust Funds. IDA operations comprise 62% of the education portfolio.

The investment in FCV settings has increased dramatically and now accounts for 26% of our portfolio.

World Bank projects reach at least 425 million students -one-third of students in low- and middle-income countries.

The World Bank’s Approach to Education

Five interrelated pillars of a well-functioning education system underpin the World Bank’s education policy approach:

- Learners are prepared and motivated to learn;

- Teachers are prepared, skilled, and motivated to facilitate learning and skills acquisition;

- Learning resources (including education technology) are available, relevant, and used to improve teaching and learning;

- Schools are safe and inclusive; and

- Education Systems are well-managed, with good implementation capacity and adequate financing.

The Bank is already helping governments design and implement cost-effective programs and tools to build these pillars.

Our Principles:

- We pursue systemic reform supported by political commitment to learning for all children.

- We focus on equity and inclusion through a progressive path toward achieving universal access to quality education, including children and young adults in fragile or conflict affected areas , those in marginalized and rural communities, girls and women , displaced populations, students with disabilities , and other vulnerable groups.

- We focus on results and use evidence to keep improving policy by using metrics to guide improvements.

- We want to ensure financial commitment commensurate with what is needed to provide basic services to all.

- We invest wisely in technology so that education systems embrace and learn to harness technology to support their learning objectives.

Laying the groundwork for the future

Country challenges vary, but there is a menu of options to build forward better, more resilient, and equitable education systems.

Countries are facing an education crisis that requires a two-pronged approach: first, supporting actions to recover lost time through remedial and accelerated learning; and, second, building on these investments for a more equitable, resilient, and effective system.

Recovering from the learning crisis must be a political priority, backed with adequate financing and the resolve to implement needed reforms. Domestic financing for education over the last two years has not kept pace with the need to recover and accelerate learning. Across low- and lower-middle-income countries, the average share of education in government budgets fell during the pandemic , and in 2022 it remained below 2019 levels.

The best chance for a better future is to invest in education and make sure each dollar is put toward improving learning. In a time of fiscal pressure, protecting spending that yields long-run gains – like spending on education – will maximize impact. We still need more and better funding for education. Closing the learning gap will require increasing the level, efficiency, and equity of education spending—spending smarter is an imperative.

- Education technology can be a powerful tool to implement these actions by supporting teachers, children, principals, and parents; expanding accessible digital learning platforms, including radio/ TV / Online learning resources; and using data to identify and help at-risk children, personalize learning, and improve service delivery.

Looking ahead

We must seize this opportunity to reimagine education in bold ways. Together, we can build forward better more equitable, effective, and resilient education systems for the world’s children and youth.

Accelerating Improvements

Supporting countries in establishing time-bound learning targets and a focused education investment plan, outlining actions and investments geared to achieve these goals.

Launched in 2020, the Accelerator Program works with a set of countries to channel investments in education and to learn from each other. The program coordinates efforts across partners to ensure that the countries in the program show improvements in foundational skills at scale over the next three to five years. These investment plans build on the collective work of multiple partners, and leverage the latest evidence on what works, and how best to plan for implementation. Countries such as Brazil (the state of Ceará) and Kenya have achieved dramatic reductions in learning poverty over the past decade at scale, providing useful lessons, even as they seek to build on their successes and address remaining and new challenges.

Universalizing Foundational Literacy

Readying children for the future by supporting acquisition of foundational skills – which are the gateway to other skills and subjects.

The Literacy Policy Package (LPP) consists of interventions focused specifically on promoting acquisition of reading proficiency in primary school. These include assuring political and technical commitment to making all children literate; ensuring effective literacy instruction by supporting teachers; providing quality, age-appropriate books; teaching children first in the language they speak and understand best; and fostering children’s oral language abilities and love of books and reading.

Advancing skills through TVET and Tertiary

Ensuring that individuals have access to quality education and training opportunities and supporting links to employment.

Tertiary education and skills systems are a driver of major development agendas, including human capital, climate change, youth and women’s empowerment, and jobs and economic transformation. A comprehensive skill set to succeed in the 21st century labor market consists of foundational and higher order skills, socio-emotional skills, specialized skills, and digital skills. Yet most countries continue to struggle in delivering on the promise of skills development.

The World Bank is supporting countries through efforts that address key challenges including improving access and completion, adaptability, quality, relevance, and efficiency of skills development programs. Our approach is via multiple channels including projects, global goods, as well as the Tertiary Education and Skills Program . Our recent reports including Building Better Formal TVET Systems and STEERing Tertiary Education provide a way forward for how to improve these critical systems.

Addressing Climate Change

Mainstreaming climate education and investing in green skills, research and innovation, and green infrastructure to spur climate action and foster better preparedness and resilience to climate shocks.

Our approach recognizes that education is critical for achieving effective, sustained climate action. At the same time, climate change is adversely impacting education outcomes. Investments in education can play a huge role in building climate resilience and advancing climate mitigation and adaptation. Climate change education gives young people greater awareness of climate risks and more access to tools and solutions for addressing these risks and managing related shocks. Technical and vocational education and training can also accelerate a green economic transformation by fostering green skills and innovation. Greening education infrastructure can help mitigate the impact of heat, pollution, and extreme weather on learning, while helping address climate change.

Examples of this work are projects in Nigeria (life skills training for adolescent girls), Vietnam (fostering relevant scientific research) , and Bangladesh (constructing and retrofitting schools to serve as cyclone shelters).

Strengthening Measurement Systems

Enabling countries to gather and evaluate information on learning and its drivers more efficiently and effectively.

The World Bank supports initiatives to help countries effectively build and strengthen their measurement systems to facilitate evidence-based decision-making. Examples of this work include:

(1) The Global Education Policy Dashboard (GEPD) : This tool offers a strong basis for identifying priorities for investment and policy reforms that are suited to each country context by focusing on the three dimensions of practices, policies, and politics.

- Highlights gaps between what the evidence suggests is effective in promoting learning and what is happening in practice in each system; and

- Allows governments to track progress as they act to close the gaps.

The GEPD has been implemented in 13 education systems already – Peru, Rwanda, Jordan, Ethiopia, Madagascar, Mozambique, Islamabad, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Sierra Leone, Niger, Gabon, Jordan and Chad – with more expected by the end of 2024.

(2) Learning Assessment Platform (LeAP) : LeAP is a one-stop shop for knowledge, capacity-building tools, support for policy dialogue, and technical staff expertise to support student achievement measurement and national assessments for better learning.

Supporting Successful Teachers

Helping systems develop the right selection, incentives, and support to the professional development of teachers.

Currently, the World Bank Education Global Practice has over 160 active projects supporting over 18 million teachers worldwide, about a third of the teacher population in low- and middle-income countries. In 12 countries alone, these projects cover 16 million teachers, including all primary school teachers in Ethiopia and Turkey, and over 80% in Bangladesh, Pakistan, and Vietnam.

A World Bank-developed classroom observation tool, Teach, was designed to capture the quality of teaching in low- and middle-income countries. It is now 3.6 million students.

While Teach helps identify patterns in teacher performance, Coach leverages these insights to support teachers to improve their teaching practice through hands-on in-service teacher professional development (TPD).

Our recent report on Making Teacher Policy Work proposes a practical framework to uncover the black box of effective teacher policy and discusses the factors that enable their scalability and sustainability.

Supporting Education Finance Systems

Strengthening country financing systems to mobilize resources for education and make better use of their investments in education.

Our approach is to bring together multi-sectoral expertise to engage with ministries of education and finance and other stakeholders to develop and implement effective and efficient public financial management systems; build capacity to monitor and evaluate education spending, identify financing bottlenecks, and develop interventions to strengthen financing systems; build the evidence base on global spending patterns and the magnitude and causes of spending inefficiencies; and develop diagnostic tools as public goods to support country efforts.

Working in Fragile, Conflict, and Violent (FCV) Contexts

The massive and growing global challenge of having so many children living in conflict and violent situations requires a response at the same scale and scope. Our education engagement in the Fragility, Conflict and Violence (FCV) context, which stands at US$5.35 billion, has grown rapidly in recent years, reflecting the ever-increasing importance of the FCV agenda in education. Indeed, these projects now account for more than 25% of the World Bank education portfolio.

Education is crucial to minimizing the effects of fragility and displacement on the welfare of youth and children in the short-term and preventing the emergence of violent conflict in the long-term.

Support to Countries Throughout the Education Cycle

Our support to countries covers the entire learning cycle, to help shape resilient, equitable, and inclusive education systems that ensure learning happens for everyone.

The ongoing Supporting Egypt Education Reform project , 2018-2025, supports transformational reforms of the Egyptian education system, by improving teaching and learning conditions in public schools. The World Bank has invested $500 million in the project focused on increasing access to quality kindergarten, enhancing the capacity of teachers and education leaders, developing a reliable student assessment system, and introducing the use of modern technology for teaching and learning. Specifically, the share of Egyptian 10-year-old students, who could read and comprehend at the global minimum proficiency level, increased to 45 percent in 2021.

In Nigeria , the $75 million Edo Basic Education Sector and Skills Transformation (EdoBESST) project, running from 2020-2024, is focused on improving teaching and learning in basic education. Under the project, which covers 97 percent of schools in the state, there is a strong focus on incorporating digital technologies for teachers. They were equipped with handheld tablets with structured lesson plans for their classes. Their coaches use classroom observation tools to provide individualized feedback. Teacher absence has reduced drastically because of the initiative. Over 16,000 teachers were trained through the project, and the introduction of technology has also benefited students.

Through the $235 million School Sector Development Program in Nepal (2017-2022), the number of children staying in school until Grade 12 nearly tripled, and the number of out-of-school children fell by almost seven percent. During the pandemic, innovative approaches were needed to continue education. Mobile phone penetration is high in the country. More than four in five households in Nepal have mobile phones. The project supported an educational service that made it possible for children with phones to connect to local radio that broadcast learning programs.

From 2017-2023, the $50 million Strengthening of State Universities in Chile project has made strides to improve quality and equity at state universities. The project helped reduce dropout: the third-year dropout rate fell by almost 10 percent from 2018-2022, keeping more students in school.

The World Bank’s first Program-for-Results financing in education was through a $202 million project in Tanzania , that ran from 2013-2021. The project linked funding to results and aimed to improve education quality. It helped build capacity, and enhanced effectiveness and efficiency in the education sector. Through the project, learning outcomes significantly improved alongside an unprecedented expansion of access to education for children in Tanzania. From 2013-2019, an additional 1.8 million students enrolled in primary schools. In 2019, the average reading speed for Grade 2 students rose to 22.3 words per minute, up from 17.3 in 2017. The project laid the foundation for the ongoing $500 million BOOST project , which supports over 12 million children to enroll early, develop strong foundational skills, and complete a quality education.

The $40 million Cambodia Secondary Education Improvement project , which ran from 2017-2022, focused on strengthening school-based management, upgrading teacher qualifications, and building classrooms in Cambodia, to improve learning outcomes, and reduce student dropout at the secondary school level. The project has directly benefited almost 70,000 students in 100 target schools, and approximately 2,000 teachers and 600 school administrators received training.

The World Bank is co-financing the $152.80 million Yemen Restoring Education and Learning Emergency project , running from 2020-2024, which is implemented through UNICEF, WFP, and Save the Children. It is helping to maintain access to basic education for many students, improve learning conditions in schools, and is working to strengthen overall education sector capacity. In the time of crisis, the project is supporting teacher payments and teacher training, school meals, school infrastructure development, and the distribution of learning materials and school supplies. To date, almost 600,000 students have benefited from these interventions.

The $87 million Providing an Education of Quality in Haiti project supported approximately 380 schools in the Southern region of Haiti from 2016-2023. Despite a highly challenging context of political instability and recurrent natural disasters, the project successfully supported access to education for students. The project provided textbooks, fresh meals, and teacher training support to 70,000 students, 3,000 teachers, and 300 school directors. It gave tuition waivers to 35,000 students in 118 non-public schools. The project also repaired 19 national schools damaged by the 2021 earthquake, which gave 5,500 students safe access to their schools again.

In 2013, just 5% of the poorest households in Uzbekistan had children enrolled in preschools. Thanks to the Improving Pre-Primary and General Secondary Education Project , by July 2019, around 100,000 children will have benefitted from the half-day program in 2,420 rural kindergartens, comprising around 49% of all preschool educational institutions, or over 90% of rural kindergartens in the country.

In addition to working closely with governments in our client countries, the World Bank also works at the global, regional, and local levels with a range of technical partners, including foundations, non-profit organizations, bilaterals, and other multilateral organizations. Some examples of our most recent global partnerships include:

UNICEF, UNESCO, FCDO, USAID, Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation: Coalition for Foundational Learning

The World Bank is working closely with UNICEF, UNESCO, FCDO, USAID, and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation as the Coalition for Foundational Learning to advocate and provide technical support to ensure foundational learning. The World Bank works with these partners to promote and endorse the Commitment to Action on Foundational Learning , a global network of countries committed to halving the global share of children unable to read and understand a simple text by age 10 by 2030.

Australian Aid, Bernard van Leer Foundation, Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, Canada, Echida Giving, FCDO, German Cooperation, William & Flora Hewlett Foundation, Conrad Hilton Foundation, LEGO Foundation, Porticus, USAID: Early Learning Partnership

The Early Learning Partnership (ELP) is a multi-donor trust fund, housed at the World Bank. ELP leverages World Bank strengths—a global presence, access to policymakers and strong technical analysis—to improve early learning opportunities and outcomes for young children around the world.

We help World Bank teams and countries get the information they need to make the case to invest in Early Childhood Development (ECD), design effective policies and deliver impactful programs. At the country level, ELP grants provide teams with resources for early seed investments that can generate large financial commitments through World Bank finance and government resources. At the global level, ELP research and special initiatives work to fill knowledge gaps, build capacity and generate public goods.

UNESCO, UNICEF: Learning Data Compact

UNESCO, UNICEF, and the World Bank have joined forces to close the learning data gaps that still exist and that preclude many countries from monitoring the quality of their education systems and assessing if their students are learning. The three organizations have agreed to a Learning Data Compact , a commitment to ensure that all countries, especially low-income countries, have at least one quality measure of learning by 2025, supporting coordinated efforts to strengthen national assessment systems.

UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS): Learning Poverty Indicator

Aimed at measuring and urging attention to foundational literacy as a prerequisite to achieve SDG4, this partnership was launched in 2019 to help countries strengthen their learning assessment systems, better monitor what students are learning in internationally comparable ways and improve the breadth and quality of global data on education.

FCDO, Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation: EdTech Hub

Supported by the UK government’s Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office (FCDO), in partnership with the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the EdTech Hub is aimed at improving the quality of ed-tech investments. The Hub launched a rapid response Helpdesk service to provide just-in-time advisory support to 70 low- and middle-income countries planning education technology and remote learning initiatives.

MasterCard Foundation

Our Tertiary Education and Skills global program, launched with support from the Mastercard Foundation, aims to prepare youth and adults for the future of work and society by improving access to relevant, quality, equitable reskilling and post-secondary education opportunities. It is designed to reframe, reform, and rebuild tertiary education and skills systems for the digital and green transformation.

Bridging the AI divide: Breaking down barriers to ensure women’s leadership and participation in the Fifth Industrial Revolution

Common challenges and tailored solutions: How policymakers are strengthening early learning systems across the world

Compulsory education boosts learning outcomes and climate action

Areas of focus.

Data & Measurement

Early Childhood Development

Financing Education

Foundational Learning

Fragile, Conflict & Violent Contexts

Girls’ Education

Inclusive Education

Skills Development

Technology (EdTech)

Tertiary Education

Initiatives

- Show More +

- Tertiary Education and Skills Program

- Service Delivery Indicators

- Evoke: Transforming education to empower youth

- Global Education Policy Dashboard

- Global Education Evidence Advisory Panel

- Show Less -

Collapse and Recovery: How the COVID-19 Pandemic Eroded Human Capital and What to Do About It

BROCHURES & FACT SHEETS

Flyer: Education Factsheet - May 2024

Publication: Realizing Education's Promise: A World Bank Retrospective – August 2023

Flyer: Education and Climate Change - November 2022

Brochure: Learning Losses - October 2022

STAY CONNECTED

Human Development Topics

Around the bank group.

Find out what the Bank Group's branches are doing in education

Global Education Newsletter - April 2024

What's happening in the World Bank Education Global Practice? Read to learn more.

Human Capital Project

The Human Capital Project is a global effort to accelerate more and better investments in people for greater equity and economic growth.

Impact Evaluations

Research that measures the impact of education policies to improve education in low and middle income countries.

Education Videos

Watch our latest videos featuring our projects across the world

Additional Resources

Education Finance

Higher Education

Digital Technologies

Education Data & Measurement

Education in Fragile, Conflict & Violence Contexts

This site uses cookies to optimize functionality and give you the best possible experience. If you continue to navigate this website beyond this page, cookies will be placed on your browser. To learn more about cookies, click here .

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Published: 13 April 2020

The effect of education on determinants of climate change risks

- Brian C. O’Neill ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7505-8897 1 ,

- Leiwen Jiang ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2073-6440 2 , 3 ,

- Samir KC 2 , 4 ,

- Regina Fuchs 5 ,

- Shonali Pachauri ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8138-3178 4 ,

- Emily K. Laidlaw 4 ,

- Tiantian Zhang 6 ,

- Wei Zhou 6 &

- Xiaolin Ren 7

Nature Sustainability volume 3 , pages 520–528 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

3251 Accesses

41 Citations

94 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Socioeconomic scenarios

- Sustainability

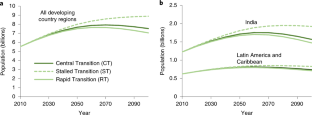

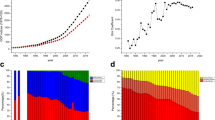

Increased educational attainment is a sustainable development priority and has been posited to have benefits for other social and environmental issues, including climate change. However, links between education and climate change risks can involve both synergies and trade-offs, and the balance of these effects remains ambiguous. Increases in educational attainment could lead to faster economic growth and therefore higher emissions, more climate change and higher risks. At the same time, improved attainment would be associated with faster fertility decline in many countries, slower population growth and therefore lower emissions, and would also be likely to reduce vulnerability to climate impacts. We employ a multiregion, multisector model of the world economy, driven with country-specific projections of future population by level of education, to test the net effect of education on emissions and on the Human Development Index (HDI), an indicator that correlates with adaptive capacity to climate impacts. We find that improved educational attainment is associated with a modest net increase in emissions but substantial improvement in the HDI values in developing country regions. Avoiding stalled progress in educational attainment and achieving gains at least consistent with historical trends is especially important in reducing future vulnerability.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

24,99 € / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

111,21 € per year

only 9,27 € per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Effectiveness of carbon dioxide emission target is linked to country ambition and education level

Education outcomes in the era of global climate change

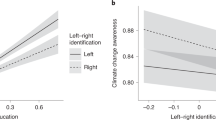

Right-wing ideology reduces the effects of education on climate change beliefs in more developed countries

Data availability.

The samples of census datasets analysed during the current study are publicly available from IPUMS International at https://international.ipums.org/international/ . The national sample household survey data analysed for this study are publicly available for Brazil ( https://www.ibge.gov.br/estatisticas/sociais/habitacao/9050-pesquisa-de-orcamentos-familiares.html?=&t=downloads ), China ( https://opendata.pku.edu.cn/dataverse/CFPS?language=en ), India (Human Development Survey, https://www.icpsr.umich.edu/icpsrweb/DSDR/studies/36151 ), Mexico ( http://en.www.inegi.org.mx/programas/enigh/tradicional/2005/ ), South Africa ( https://www.datafirst.uct.ac.za/dataportal/index.php/catalog/316 ) and Uganda ( http://microdata.worldbank.org/index.php/catalog/2059 ), after registering and submitting requests. The national survey data for some countries are available but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under licence for the current study and so are not publicly available. These include India (National Sample Survey 2004–2005 and 2011–2012, http://www.icssrdataservice.in/datarepository/index.php/ ) and Indonesia ( https://microdata.bps.go.id/mikrodata/index.php/catalog/SUSENAS ). While these original full datasets have restrictions on availability, tables of derived results from the original datasets can be provided upon request.

Code availability

The code for the version of the iPETS model used to produce economic and emissions projections for this analysis is available upon request. It will eventually be publicly available at ipetsmodel.com.

Smith, W. C., Anderson, E., Salinas, D., Horvatek, R. & Baker, D. P. A meta-analysis of education effects on chronic disease: the causal dynamics of the population education transition curve. Soc. Sci. Med. 127 , 29–40 (2015).

Article Google Scholar

Coady, D. & Dizioli, A. Income inequality and education revisited: persistence, endogeneity and heterogeneity. Appl. Econ. 50 , 2747–2761 (2018).

Hanmer, L. & Klugman, J. Exploring women’s agency and empowerment in developing countries: where do we stand? Fem. Econ. 22 , 237–263 (2016).

Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (United Nations, 2015).

A Guide to SDG Interactions: From Science to Implementation (International Council for Science, 2017).

McCollum, D. L. et al. Connecting the sustainable development goals by their energy inter-linkages. Environ. Res. Lett. 13 , 033006 (2018).

Pradhan, P., Costa, L., Rybski, D., Lucht, W. & Kropp, J. P. A systematic study of sustainable development goal (SDG) interactions. Earth’s Future 5 , 1169–1179 (2017).

Moyer, J. D. & Bohl, D. K. Alternative pathways to human development: assessing trade-offs and synergies in achieving the Sustainable Development Goals. Futures 105 , 199–210 (2019).

Gomez-Echeverri, L. Climate and development: enhancing impact through stronger linkages in the implementation of the Paris Agreement and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Phil. Trans. R. Soc. A 376 , 20160444 (2018).

Oppenheimer, M. et al. in IPCC Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability (eds Field, C. B. et al.) 1039–1100 (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2014) .

O’Neill, B. C. et al. Global demographic trends and future carbon emissions. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 107 , 17521–17526 (2010).

Crespo Cuaresma, J., Lutz, W. & Sanderson, W. Is the demographic dividend an education dividend? Demography 51 , 299–315 (2014).

Lutz, W., Muttarak, R. & Striessnig, E. Universal education is key to enhanced climate adaptation. Science 346 , 1061–1062 (2014).

Article CAS Google Scholar

Gall, M. Indices of Social Vulnerability to Natural Hazards: A Comparative Evaluation (Univ. South Carolina, 2007).

Füssel, H.-M. Review and Quantitative Analysis of Indices of Climate Change Exposure, Adaptive Capacity, Sensitivity, and Impacts (World Bank, 2010); https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/9193

KC, S. & Lutz, W. The human core of the shared socioeconomic pathways: population scenarios by age, sex and level of education for all countries to 2100. Glob. Environ. Change 42 , 181–192 (2017).

O’Neill, B. C. et al. The roads ahead: narratives for shared socioeconomic pathways describing world futures in the 21st century. Glob. Environ. Change 42 , 169–180 (2017).

Riahi, K. et al. The shared socioeconomic pathways and their energy, land use, and greenhouse gas emissions implications: an overview. Glob. Environ. Change 42 , 153–168 (2017).

Ren, X. et al. Avoided economic impacts of climate change on agriculture: integrating a land surface model (CLM) with a global economic model (iPETS). Clim. Change 146 , 517–531 (2018).

Ren, X., Lu, Y., O'Neill, B. C. & Weitzel, M. Economic and biophysical impacts on agriculture under 1.5 °C and 2 °C warming. Environ. Res. Lett. 13 , 115006 (2018).

Böhringer, C. & Löschel, A. Computable general equilibrium models for sustainability impact assessment: status quo and prospects. Ecol. Econ. 60 , 49–64 (2006).

Scrieciu, S. S. The inherent dangers of using computable general equilibrium models as a single integrated modelling framework for sustainability impact assessment. A critical note on Böhringer and Löschel (2006). Ecol. Econ. 60 , 678–684 (2007).

Lutz, W. & Skirbekk, V. in World Population & Human Capital in the Twenty-First Century: An Overview (eds Lutz, W. et al.) 14–38 (Oxford Univ. Press, 2014).

IPCC: Summary for Policymakers. In Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis (eds Stocker, T. F. et al.) (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2013).

Fuso Nerini, F. et al. Mapping synergies and trade-offs between energy and the sustainable development goals. Nat. Energy 3 , 10–15 (2018).

Wiedenhofer, D., Smetschka, B., Akenji, L., Jalas, M. & Haberl, H. Household time use, carbon footprints, and urban form: a review of the potential contributions of everyday living to the 1.5 °C climate target. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 30 , 7–17 (2018).

Duarte, R. et al. Modeling the carbon consequences of pro-environmental consumer behavior. Appl. Energy 184 , 1207–1216 (2016).

Dickson, J. R., Hughes, B. B. & Irfan, M. T. Advancing Global Education (Routledge, 2010).

Burke, M., Davis, W. M. & Diffenbaugh, N. S. Large potential reduction in economic damages under UN mitigation targets. Nature 557 , 549–553 (2018).

IPCC Climate Change 2014: Synthesis Report (eds Core Writing Team, Pachauri, R. K. & Meyer, L. A.) (IPCC, 2014).

Casey, G. & Galor, O. Is faster economic growth compatible with reductions in carbon emissions? The role of diminished population growth. Environ. Res. Lett. 12 , 014003 (2017).

Bongaarts, J. & O’Neill, B. C. Global warming policy: is population left out in the cold? Science 361 , 650–652 (2018).

Jiang, L. & O’Neill, B. C. Global urbanization projections for the shared socioeconomic pathways. Glob. Environ. Change 42 , 193–199 (2017).

Dellink, R., Chateau, J., Lanzi, E. & Magné, B. Long-term economic growth projections in the shared socioeconomic pathways. Glob. Environ. Change 42 , 200–214 (2017).

Lutz, W. & Kc, S. Global human capital: integrating education and population. Science 333 , 587–592 (2011).

KC, S. et al. Projection of populations by level of educational attainment, age, and sex for 120 countries for 2005–2050. Demogr. Res. 22 , 383–472 (2010).

KC, S., Potancokova, M., Bauer, R., Goujon, A. & Striessnig, E. in World Population and Human Capital in the Twenty-First Century (eds Lutz, W. et al.) 434–518 (Oxford Univ. Press, 2014).

Cutler, D. & Lleras-Muney, A. in Encyclopedia of Health Economics (ed. Culyer, A. J.) 232–245 (Elsevier, 2014).

Baker, D. P., Leon, J., Smith Greenaway, E. G., Collins, J. & Movit, M. The education effect on population health: a reassessment. Popul. Dev. Rev. 37 , 307–332 (2011).

KC, S. & Lentzner, H. The effect of education on adult mortality and disability: a global perspective. Vienna Yearb. Popul. Res. 8 , 201–235 (2010).

Rindfuss, R. R., St. John, C. & Bumpass, L. L. Education and the timing of motherhood: disentangling causation. J. Marriage Fam. 46 , 981–984 (1984).

Gerster, M., Ejrnæs, M. & Keiding, N. The causal effect of educational attainment on completed fertility for a cohort of Danish women—does feedback play a role? Stat. Biosci. 6 , 204–222 (2014).

Kravdal, Ø. Effects of current education on second- and third-birth rates among Norwegian women and men born in 1964: substantive interpretations and methodological issues. Demogr. Res. 17 , 211–246 (2007).

Forced Out: Mandatory Pregnancy Testing and the Expulsion of Pregnant Students in Tanzanian Schools (CRR, 2013); https://go.nature.com/2WJOg9J

Bongaarts, J. The causes of educational differences in fertility in Sub-Saharan Africa. Vienna Yearb. Popul. Res. 8 , 31–50 (2010).

Clarke, D. Children and their parents: a review of fertility and causality. J. Econ. Surv. 32 , 518–540 (2018).

Hoem, J. M. & Kreyenfeld, M. Anticipatory analysis and its alternatives in life-course research. Part 1: the role of education in the study of first childbearing. Demogr. Res. 15 , 461–484 (2006).

Calvin, K. et al. The SSP4: a world of deepening inequality. Glob. Environ. Change 42 , 284–296 (2017).

Rogelj, J. et al. Scenarios towards limiting global mean temperature increase below 1.5 °C. Nat. Clim. Change 8 , 325–332 (2018).

Download references

Acknowledgements

We thank the Asian Demographic Research Institute at Shanghai University for hosting research stays for B.C.O. during which parts of this work were carried out. A substantial amount of the work for this study was completed while B.C.O., L.J., E.K.L. and X.R. were at the National Center for Atmospheric Research, Boulder, CO.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Josef Korbel School of International Studies and Pardee Center for International Futures, University of Denver, Denver, CO, USA

Brian C. O’Neill

Asian Demographic Research Institute, Shanghai University, Shanghai, China

Leiwen Jiang & Samir KC

Population Council, New York, NY, USA

- Leiwen Jiang

International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis, Laxenburg, Austria

Samir KC, Shonali Pachauri & Emily K. Laidlaw

Statistics Austria, Vienna, Austria

Regina Fuchs

Institute of Population and Development Studies, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, China

Tiantian Zhang & Wei Zhou

National Center for Atmospheric Research, Boulder, CO, USA

Xiaolin Ren

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

B.C.O. led, and L.J., S.KC and S.P. contributed to, the design of the study. B.C.O. coordinated the paper and led the writing, with contributions from L.J., S.KC, S.P. and E.K.L. L.J., R.F., S.P. and E.K.L. led the analysis of household survey data, with contributions from T.Z. and W.Z. S.KC carried out the population–education projections. L.J. carried out the household projections. X.R. carried out the iPETS model projections, with contributions from B.C.O. B.C.O., L.J., S.KC, S.P., E.K.L. and X.R. interpreted results.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Brian C. O’Neill .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information.

Supplementary Methods 1–3, Tables 1–4, Figs. 1–4 and references.

Reporting Summary

Rights and permissions.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

O’Neill, B.C., Jiang, L., KC, S. et al. The effect of education on determinants of climate change risks. Nat Sustain 3 , 520–528 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-020-0512-y

Download citation

Received : 03 August 2018

Accepted : 11 March 2020

Published : 13 April 2020

Issue Date : July 2020

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-020-0512-y

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

Spatial and temporal changes in social vulnerability to natural hazards: a case study for china counties.

Natural Hazards (2024)

Achieving carbon neutrality in Africa is possible: the impact of education, employment, and renewable energy consumption on carbon emissions

- Chinyere Ori Elom

- Robert Ugochukwu Onyeneke

- Chidebe Chijioke Uwaleke

Carbon Research (2024)

Climate change unequally affects nitrogen use and losses in global croplands

- Chenchen Ren

- Xiuming Zhang

Nature Food (2023)

Assessing populations exposed to climate change: a focus on Africa in a global context

- Daniela Ghio

- Anne Goujon

- Thomas Petroliagkis

Population and Environment (2023)

Digitalization and its impact on labour market and education. Selected aspects

- Piotr Hetmańczyk

Education and Information Technologies (2023)

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

< Back to my filtered results

Population education in non-formal education and development programmes: a manual for field-workers

This manual provides practical examples of strategies, approaches and materials designed to integrate population education into various development programmes. It is a useful reference for field workers who are involved in planning, implementing and evaluating out-of-school population education programmes.

- History & Overview

- Meet Our Team

- Program FAQs

- Social Studies

- Language Arts

- Distance Learning

- Population Pyramids

- World Population “dot” Video

- Student Video Contest

- Lower Elementary (K-2)

- Upper Elementary (3-5)

- Middle School (6-8)

- High School (9-12)

- Browse all Resources

- Content Focus by Grade

- Standards Matches by State

- Infographics

- Articles, Factsheets & Book Lists

- Population Background Info

- Upcoming Online Workshops

- On-Demand Webinar Library

- Online Graduate Course

- Request an Online or In-person Workshop

- About Teachers Workshops

- About Online Teacher Workshops

- Pre-Service Workshops for University Classes

- In-Service Workshops for Teachers

- Workshops for Nonformal Educators

- Where We’ve Worked

- About the Network

- Trainer Spotlight

- Trainers Network FAQ

- Becoming a Trainer

- Annual Leadership Institutes

- Application

Filter Resources

By grade level, by resource type.

- Lesson Plan ?

- Lesson Packet ?

- Curriculum ?

Classroom Resources

Lesson plan:.

Students articulate their thoughts about the ethical issues related to population reaching seven billion and...

Through an article, video, simulation game, and small group research, students explore factors that influence...

Students test different pH solutions on radish seeds to determine the optimal level for seed...

Students discuss the concept of biotic potential and use equations to determine how a family...

Students use beans to model population growth in several mystery countries while varying four key...

Students participate in a game that mimics the relationship between population growth and aquifer depletion....

Students examine their own perceptions of gender roles through two short mental exercises, then research...

Students determine a list of criteria to use when deciding the fate of endangered species,...

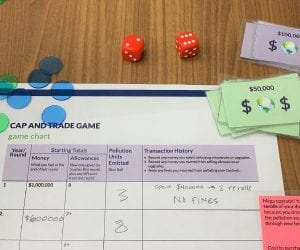

Students play a game that simulates a cap and trade system, and analyze its successes...

Health case study reading: Discover Rwanda's success in improving child and maternal mortality over the...

Secondary-level reading surveys past and present food and diet trends in the United States –...

Secondary- level reading provides a journey through the history of schooling (K-12 and higher education)...

Secondary-level reading traces the history of transportation in the United States from horse-drawn carriages to...

Secondary-level reading provides an overview of the history of love and marriage in the U.S.,...

Secondary-level reading looks at the history of work in the United States for different segments...

Secondary-level reading explores the relationship between U.S. people and the natural environment from early settlements...

Personal consumption background reading: What is an ecological footprint and what are the impacts of...

Rich and poor case study reading: There are already great inventions for reducing global poverty....

Lesson Packet:

U.S. population takes center stage in this downloadable packet of classroom lessons, 330 Million in...

Thematic unit for the middle school classroom covers issues related to garbage and solid waste...

Thematic unit for the high school classroom on outdoor and indoor air pollution. Includes teaching...

Thematic unit for the high school classroom on biodiversity issues, endangered animals, and extinction rates....

Thematic unit for the high school classroom covers a wide range topics related to climate...

Packet of 2024 Earth Day lesson plans for K - 5th grades is free to...

Packet of 2024 Earth Day lesson plans for 9th - 12th grades. Free to download!...

Packet of 2024 Earth Day lesson plans for 6th, 7th and 8th grades is free...

Thematic unit for the high school classroom on energy issues in more developed and less...

Curriculum:

Fully online, elementary curriculum connects students to the world around them while building their math,...

A must for high school students to explore some of the most pressing environmental, social...

Fully online, interdisciplinary curriculum helps middle school students understand the connections between human population growth,...

You've found the ultimate multi-disciplinary tool to introduce students of all ages to population studies...

Students work in small groups to determine the main environmental concerns during given periods of...

Acting as countries in a simulation game, students discuss how resources are inequitably distributed throughout...

A simulation and gardening lab that gives students hands-on experience with the effects of increasing...

In small groups, students explore changes in regional fertility rates and life expectancy trends over...

A visual demonstration of the limited farmland available on Earth (instructor cuts an apple to...

Acting as store owners, students conduct a mini-census to identify their potential market and then...

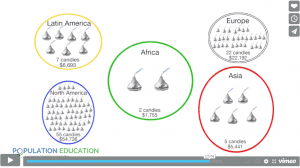

Acting as the residents of five major regions of the world, students compare various statistics...

In two simulation games, students determine individual short-term consumption strategies that will maximize resources for...

Join Population Education on Twitter! We love connecting with teachers and educators in the twitterverse....

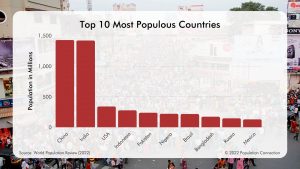

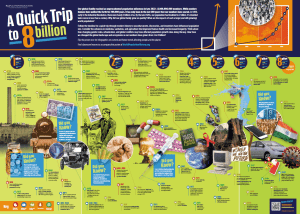

Bar graph shows the populations of the 10 most populous countries. The top 10 most...

Colorful, informative poster makes the perfect classroom wall decoration - it inspires conversations and questions....

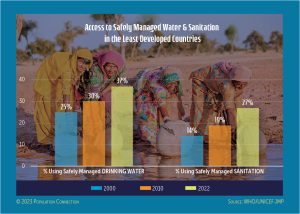

Bar charts shows the percentage of people using safely managed drinking water and safely managed...

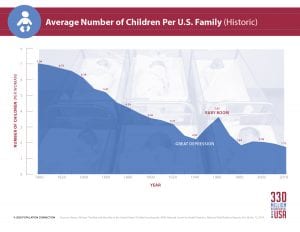

Line graph shows the average number of children per woman in the United States over...

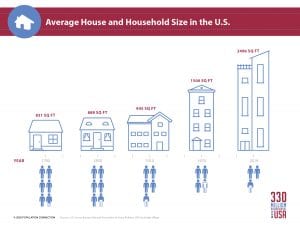

Infographic shows that the average size of houses in the United States has increased from...

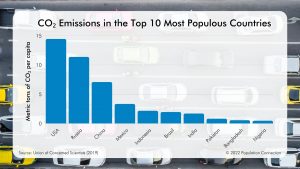

Bar graph shows the amount of carbon dioxide per capita, in metric tons, is emitted...

Six cards that compare resource use in the United States and worldwide.

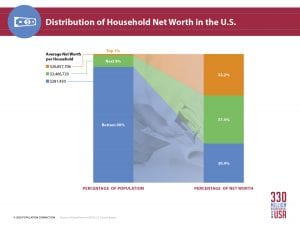

Infographic shows the how household net worth in the U.S. is distributed among the population....

Privacy Overview

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Population Education: A General Introduction

2021, IJSES

Population education is basically the education that deals about population and its different aspects like fertility, mortality, migration, infiltration, emigration etc. that means we can say that population education is a branch of education that entails the individual to gain some knowledge about population and its impact on our society as well as the whole world. It is a new area of study.

Related Papers

Journal of Educational and Social Research

MUHAMMAD YOUSAF

muhammad yousaf

This research aimed to evaluate the implementation of Population Education in senior high school in terms of (1) learning process, (2) learning materials, (3) evaluation process, (4) course outcome, (5) teachers' role, (6) perception of Population Education, and (7) factors supporting and inhabitting Population Education. The research subjects were one teachers' supervisor, three teachers, and 65 students. The data were collected through questionnaires, interviews, and documentation and analyzed quantitatively using descriptive statistics. The qualitative data collected through interviews were used for deeper explanation. The research findings were: (1) the teaching process was not quite appropriate, (2) materials for Population Education were available and efficient , (3) the evaluation process was not appropriate, (4) the students were satisfied with the teachers' role, (5) the students' perception of Population Education was very positive, and (6) the constraints in Population Education included (a) limitation in time, (b) too many extracurricular activities, (c) rapid change of data, and (d) the validity of materials.

Steve Viederman

Dimitar Simeonov

The role of education and its relation to well-being is a topic of growing public interest. The level of development of the population education is of the utmost importance for the economic and social perspective of each country. This report aims to place education as a key element of human well-being, using a geographical approach.

Abstract: This working paper is an overview of the status of population education in early 1972. It is defined as a program which provides for a study of the population situation of the family, community, nation and world, with the purpose of developing in the students ...

RELATED PAPERS

Osservatorio Indipendente Concorsi Universitari (OICU)

Virtual Archaeology Review

Jaime Molina

Journal of Solution Chemistry

Bart Spiegeleer

European eating disorders review : the journal of the Eating Disorders Association

Maria La Via

Proceedings of the London Mathematical Society

jean-michel Vallin

Ciudad Y Territorio Estudios Territoriales Issn 1133 4762 2014 Vol Xlvi N 181

Agustín Ajá

Recasting Culture and Space in …

Shawn Parkhurst

Materials Today: Proceedings

Mauro Zarrelli

学校原版英国伦敦艺术大学毕业证 ual文凭证书设计录取通知书原版一模一样

Futuros que están siendo https://futuros-que-estan-siendo-548080.webflow.io/

Gaya Makaran

Journal of Social Issues

Craig Haney

Reproduction

jkjhygffg bhhnhfgf

Sophia Kompotiati

The European Journal of Social and Behavioural Sciences

Pärje Ülavere

International Journal of Psychophysiology

Ray Edward Johnson

Mario Boaratti

George Nolas

American Journal of Medical Genetics Part C: Seminars in Medical Genetics

Inge De Wandele

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- HHS Author Manuscripts

The relationship between education and health: reducing disparities through a contextual approach

Anna zajacova.

Western University

Elizabeth M. Lawrence

University of North Carolina

Adults with higher educational attainment live healthier and longer lives compared to their less educated peers. The disparities are large and widening. We posit that understanding the educational and macro-level contexts in which this association occurs is key to reducing health disparities and improving population health. In this paper, we briefly review and critically assess the current state of research on the relationship between education and health in the United States. We then outline three directions for further research: We extend the conceptualization of education beyond attainment and demonstrate the centrality of the schooling process to health; We highlight the dual role of education a driver of opportunity but also a reproducer of inequality; We explain the central role of specific historical socio-political contexts in which the education-health association is embedded. This research agenda can inform policies and effective interventions to reduce health disparities and improve health of all Americans.

URGENT NEED FOR NEW DIRECTIONS IN EDUCATION-HEALTH RESEARCH

Americans have worse health than people in other high-income countries, and have been falling further behind in recent decades ( 137 ). This is partially due to the large health inequalities and poor health of adults with low education ( 84 ). Understanding the health benefits of education is thus integral to reducing health disparities and improving the well-being of 21 st century populations. Despite tremendous prior research, critical questions about the education-health relationship remain unanswered, in part because education and health are intertwined over the lifespans within and across generations and are inextricably embedded in the broader social context.

We posit that to effectively inform future educational and heath policy, we need to capture education ‘in action’ as it generates and constrains opportunity during the early lifespans of today’s cohorts. First, we need to expand our operationalization of education beyond attainment to consider the long-term educational process that precedes the attainment and its effect on health. Second, we need to re-conceptualize education as not only a vehicle for social success, valuable resources, and good health, but also as an institution that reproduces inequality across generations. And third, we argue that investigators need to bring historical, social and policy contexts into the heart of analyses: how does the education-health association vary across place and time, and how do political forces influence that variation?

During the past several generations, education has become the principal pathway to financial security, stable employment, and social success ( 8 ). At the same time, American youth have experienced increasingly unequal educational opportunities that depend on the schools they attend, the neighborhoods they live in, the color of their skin, and the financial resources of their family. The decline in manufacturing and rise of globalization have eroded the middle class, while the increasing returns to higher education magnified the economic gaps among working adults and families ( 107 ). In addition to these dramatic structural changes, policies that protected the welfare of vulnerable groups have been gradually eroded or dismantled ( 129 ). Together, these changes triggered a precipitous growth of economic and social inequalities in the American society ( 17 ; 106 ).

Unsurprisingly, health disparities grew hand in hand with the socio-economic inequalities. Although the average health of the US population improved over the past decades ( 67 ; 85 ), the gains largely went to the most educated groups. Inequalities in health ( 53 ; 77 ; 99 ) and mortality ( 86 ; 115 ) increased steadily, to a point where we now see an unprecedented pattern: health and longevity are deteriorating among those with less education ( 92 ; 99 ; 121 ; 143 ). With the current focus of the media, policymakers, and the public on the worrisome health patterns among less-educated Americans ( 28 ; 29 ), as well as the growing recognition of the importance of education for health ( 84 ), research on the health returns to education is at a critical juncture. A comprehensive research program is needed to understand how education and health are related, in order to identify effective points of intervention to improve population health and reduce disparities.

The article is organized in two parts. First, we review the current state of research on the relationship between education and health. In broad strokes, we summarize the theoretical and empirical foundations of the education-health relationship and critically assess the literature on the mechanisms and causal influence of education on health. In the second part, we highlight gaps in extant research and propose new directions for innovative research that will fill these gaps. The enormous breadth of the literature on education and health necessarily limits the scope of the review in terms of place and time; we focus on the United States and on findings generated during the rapid expansion of the education-health research in the past 10–15 years. The terms “education” and “schooling” are used interchangeably. Unless we state otherwise, both refer to attained education, whether measured in completed years or credentials. For references, we include prior review articles where available, seminal papers, and recent studies as the best starting points for further reading.

THE ASSOCIATION BETWEEN EDUCATION AND HEALTH

Conceptual toolbox for examining the association.

Researchers have generally drawn from three broad theoretical perspectives to hypothesize the relationship between education and health. Much of the education-health research over the past two decades has been grounded in the Fundamental Cause Theory ( 75 ). The FCT posits that social factors such as education are ‘fundamental’ causes of health and disease because they determine access to a multitude of material and non-material resources such as income, safe neighborhoods, or healthier lifestyles, all of which protect or enhance health. The multiplicity of pathways means that even as some mechanisms change or become less important, other mechanisms will continue to channel the fundamental dis/advantages into differential health ( 48 ). The Human Capital Theory (HCT), borrowed from econometrics, conceptualizes education as an investment that yields returns via increased productivity ( 12 ). Education improves individuals’ knowledge, skills, reasoning, effectiveness, and a broad range of other abilities, which can be utilized to produce health ( 93 ). The third approach, the Signaling or Credentialing perspective ( 34 ; 125 ) has been used to explain the observed large discontinuities in health at 12 or 16 years of schooling, typically associated with the receipt of a high school and college degrees, respectively. This perspective views earned credentials as a potent signal about one’s skills and abilities, and emphasizes the economic and social returns to such signals. Thus all three perspectives postulate a causal relationship between education and health and identify numerous mechanisms through which education influences health. The HCT specifies the mechanisms as embodied skills and abilities, FCT emphasizes the dynamism and flexibility of mechanisms, and credentialism identifies social responses to educational attainment. All three theoretical approaches, however, operationalize the complex process of schooling solely in terms of attainment and thus do not focus on differences in educational quality, type, or other institutional factors that might independently influence health. They also focus on individual-level factors: individual attainment, attainment effects, and mechanisms, and leave out the social context in which the education and health processes are embedded.

Observed associations between education and health

Empirically, hundreds of studies have documented “the gradient” whereby more schooling is linked with better health and longer life. A seminal 1973 book by Kitagawa and Hauser powerfully described large differences in mortality by education in the United States ( 71 ), a finding that has since been corroborated in numerous studies ( 31 ; 42 ; 46 ; 109 ; 124 ). In the following decades, nearly all health outcomes were also found strongly patterned by education. Less educated adults report worse general health ( 94 ; 141 ), more chronic conditions ( 68 ; 108 ), and more functional limitations and disability ( 118 ; 119 ; 130 ; 143 ). Objective measures of health, such as biological risk levels, are similarly correlated with educational attainment ( 35 ; 90 ; 140 ), showing that the gradient is not a function of differential reporting or knowledge.

The gradient is evident in men and women ( 139 ) and among all race/ethnic groups ( 36 ). However, meaningful group differences exist ( 60 ; 62 ; 91 ). In particular, education appears to have stronger health effects for women than men ( 111 ) and stronger effects for non-Hispanic whites than minority adults ( 134 ; 135 ) even if the differences are modest for some health outcomes ( 36 ). The observed variations may reflect systematic social differences in the educational process such as quality of schooling, content, or institutional type, as well as different returns to educational attainment in the labor market across population groups ( 26 ). At the same time, the groups share a common macro-level social context, which may underlie the gradient observed for all.

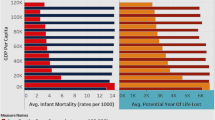

To illustrate the gradient, we analyzed 2002–2016 waves of the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) data from adults aged 25–64. Figure 1 shows the levels of three health outcomes across educational attainment levels in six major demographic groups predicted at age 45. Three observations are noteworthy. First, the gradient is evident for all outcomes and in all race/ethnic/gender groups. Self-rated health exemplifies the staggering magnitude of the inequalities: White men and women without a high school diploma have about 57% chance of reporting fair or poor health, compared to just 9% for college graduates. Second, there are major group differences as well, both in the predicted levels of health problems, as well as in the education effects. The latter are not necessarily visible in the figures but the education effects are stronger for women and weaker for non-white adults as prior studies showed (table with regression model results underlying the prior statement is available from the authors). Third, an intriguing exception pertains to adults with “some college,” whose health is similar to high school graduates’ in health outcomes other than general health, despite their investment in and exposure to postsecondary education. We discuss this anomaly below.

Predicted Probability of Health Problems

Source: 2002–2016 NHIS Survey, Adults Age 25–64

Pathways through which education impacts health

What explains the improved health and longevity of more educated adults? The most prominent mediating mechanisms can be grouped into four categories: economic, health-behavioral, social-psychological, and access to health care. Education leads to better, more stable jobs that pay higher income and allow families to accumulate wealth that can be used to improve health ( 93 ). The economic factors are an important link between schooling and health, estimated to account for about 30% of the correlation ( 36 ). Health behaviors are undoubtedly an important proximal determinant of health but they only explain a part of the effect of schooling on health: adults with less education are more likely to smoke, have an unhealthy diet, and lack exercise ( 37 ; 73 ; 105 ; 117 ). Social-psychological pathways include successful long-term marriages and other sources of social support to help cope with stressors and daily hassles ( 128 ; 131 ). Interestingly, access to health care, while important to individual and population health overall, has a modest role in explaining health inequalities by education ( 61 ; 112 ; 133 ), highlighting the need to look upstream beyond the health care system toward social factors that underlie social disparities in health. Beyond these four groups of mechanisms that have received the most attention by investigators, many others have been examined, such as stress, cognitive and noncognitive skills, or environmental exposures ( 11 ; 43 ). Several excellent reviews further discuss mechanisms ( 2 ; 36 ; 66 ; 70 ; 93 ).

Causal interpretation of the education-health association

A burgeoning number of studies used innovative approaches such as natural experiments and twin design to test whether and how education causally affects health. These analyses are essential because recommendations for educational policies, programs, and interventions seeking to improve population health hinge on the causal impact of schooling on health outcomes. Overall, this literature shows that attainment, measured mostly in completed years of schooling, has a causal impact on health across numerous (though not all) contexts and outcomes.