14 Crafting a Thesis Statement

Learning Objectives

- Craft a thesis statement that is clear, concise, and declarative.

- Narrow your topic based on your thesis statement and consider the ways that your main points will support the thesis.

Crafting a Thesis Statement

A thesis statement is a short, declarative sentence that states the purpose, intent, or main idea of a speech. A strong, clear thesis statement is very valuable within an introduction because it lays out the basic goal of the entire speech. We strongly believe that it is worthwhile to invest some time in framing and writing a good thesis statement. You may even want to write your thesis statement before you even begin conducting research for your speech. While you may end up rewriting your thesis statement later, having a clear idea of your purpose, intent, or main idea before you start searching for research will help you focus on the most appropriate material. To help us understand thesis statements, we will first explore their basic functions and then discuss how to write a thesis statement.

Basic Functions of a Thesis Statement

A thesis statement helps your audience by letting them know, clearly and concisely, what you are going to talk about. A strong thesis statement will allow your reader to understand the central message of your speech. You will want to be as specific as possible. A thesis statement for informative speaking should be a declarative statement that is clear and concise; it will tell the audience what to expect in your speech. For persuasive speaking, a thesis statement should have a narrow focus and should be arguable, there must be an argument to explore within the speech. The exploration piece will come with research, but we will discuss that in the main points. For now, you will need to consider your specific purpose and how this relates directly to what you want to tell this audience. Remember, no matter if your general purpose is to inform or persuade, your thesis will be a declarative statement that reflects your purpose.

How to Write a Thesis Statement

Now that we’ve looked at why a thesis statement is crucial in a speech, let’s switch gears and talk about how we go about writing a solid thesis statement. A thesis statement is related to the general and specific purposes of a speech.

Once you have chosen your topic and determined your purpose, you will need to make sure your topic is narrow. One of the hardest parts of writing a thesis statement is narrowing a speech from a broad topic to one that can be easily covered during a five- to seven-minute speech. While five to seven minutes may sound like a long time for new public speakers, the time flies by very quickly when you are speaking. You can easily run out of time if your topic is too broad. To ascertain if your topic is narrow enough for a specific time frame, ask yourself three questions.

Is your speech topic a broad overgeneralization of a topic?

Overgeneralization occurs when we classify everyone in a specific group as having a specific characteristic. For example, a speaker’s thesis statement that “all members of the National Council of La Raza are militant” is an overgeneralization of all members of the organization. Furthermore, a speaker would have to correctly demonstrate that all members of the organization are militant for the thesis statement to be proven, which is a very difficult task since the National Council of La Raza consists of millions of Hispanic Americans. A more appropriate thesis related to this topic could be, “Since the creation of the National Council of La Raza [NCLR] in 1968, the NCLR has become increasingly militant in addressing the causes of Hispanics in the United States.”

Is your speech’s topic one clear topic or multiple topics?

A strong thesis statement consists of only a single topic. The following is an example of a thesis statement that contains too many topics: “Medical marijuana, prostitution, and Women’s Equal Rights Amendment should all be legalized in the United States.” Not only are all three fairly broad, but you also have three completely unrelated topics thrown into a single thesis statement. Instead of a thesis statement that has multiple topics, limit yourself to only one topic. Here’s an example of a thesis statement examining only one topic: Ratifying the Women’s Equal Rights Amendment as equal citizens under the United States law would protect women by requiring state and federal law to engage in equitable freedoms among the sexes.

Does the topic have direction?

If your basic topic is too broad, you will never have a solid thesis statement or a coherent speech. For example, if you start off with the topic “Barack Obama is a role model for everyone,” what do you mean by this statement? Do you think President Obama is a role model because of his dedication to civic service? Do you think he’s a role model because he’s a good basketball player? Do you think he’s a good role model because he’s an excellent public speaker? When your topic is too broad, almost anything can become part of the topic. This ultimately leads to a lack of direction and coherence within the speech itself. To make a cleaner topic, a speaker needs to narrow her or his topic to one specific area. For example, you may want to examine why President Obama is a good public speaker.

Put Your Topic into a Declarative Sentence

You wrote your general and specific purpose. Use this information to guide your thesis statement. If you wrote a clear purpose, it will be easy to turn this into a declarative statement.

General purpose: To inform

Specific purpose: To inform my audience about the lyricism of former President Barack Obama’s presentation skills.

Your thesis statement needs to be a declarative statement. This means it needs to actually state something. If a speaker says, “I am going to talk to you about the effects of social media,” this tells you nothing about the speech content. Are the effects positive? Are they negative? Are they both? We don’t know. This sentence is an announcement, not a thesis statement. A declarative statement clearly states the message of your speech.

For example, you could turn the topic of President Obama’s public speaking skills into the following sentence: “Because of his unique sense of lyricism and his well-developed presentational skills, President Barack Obama is a modern symbol of the power of public speaking.” Or you could state, “Socal media has both positive and negative effects on users.”

Adding your Argument, Viewpoint, or Opinion

If your topic is informative, your job is to make sure that the thesis statement is nonargumentative and focuses on facts. For example, in the preceding thesis statement, we have a couple of opinion-oriented terms that should be avoided for informative speeches: “unique sense,” “well-developed,” and “power.” All three of these terms are laced with an individual’s opinion, which is fine for a persuasive speech but not for an informative speech. For informative speeches, the goal of a thesis statement is to explain what the speech will be informing the audience about, not attempting to add the speaker’s opinion about the speech’s topic. For an informative speech, you could rewrite the thesis statement to read, “Barack Obama’s use of lyricism in his speech, ‘A World That Stands as One,’ delivered July 2008 in Berlin demonstrates exceptional use of rhetorical strategies.

On the other hand, if your topic is persuasive, you want to make sure that your argument, viewpoint, or opinion is clearly indicated within the thesis statement. If you are going to argue that Barack Obama is a great speaker, then you should set up this argument within your thesis statement.

For example, you could turn the topic of President Obama’s public speaking skills into the following sentence: “Because of his unique sense of lyricism and his well-developed presentational skills, President Barack Obama is a modern symbol of the power of public speaking.” Once you have a clear topic sentence, you can start tweaking the thesis statement to help set up the purpose of your speech.

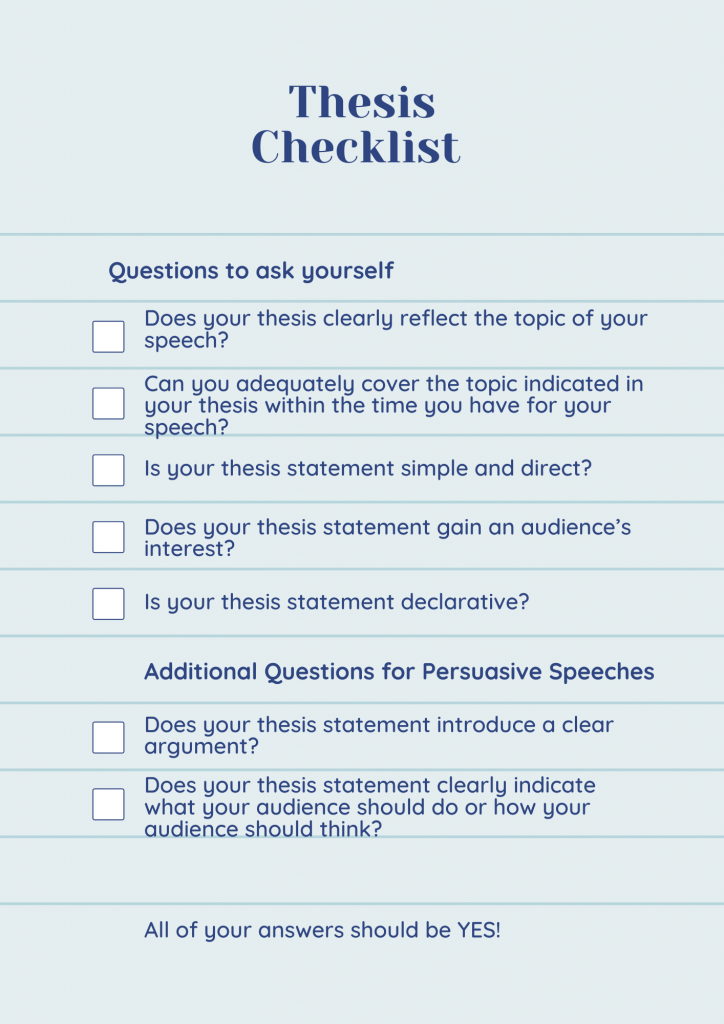

Thesis Checklist

Once you have written a first draft of your thesis statement, you’re probably going to end up revising your thesis statement a number of times prior to delivering your actual speech. A thesis statement is something that is constantly tweaked until the speech is given. As your speech develops, often your thesis will need to be rewritten to whatever direction the speech itself has taken. We often start with a speech going in one direction, and find out through our research that we should have gone in a different direction. When you think you finally have a thesis statement that is good to go for your speech, take a second and make sure it adheres to the criteria shown below.

Preview of Speech

The preview, as stated in the introduction portion of our readings, reminds us that we will need to let the audience know what the main points in our speech will be. You will want to follow the thesis with the preview of your speech. Your preview will allow the audience to follow your main points in a sequential manner. Spoiler alert: The preview when stated out loud will remind you of main point 1, main point 2, and main point 3 (etc. if you have more or less main points). It is a built in memory card!

For Future Reference | How to organize this in an outline |

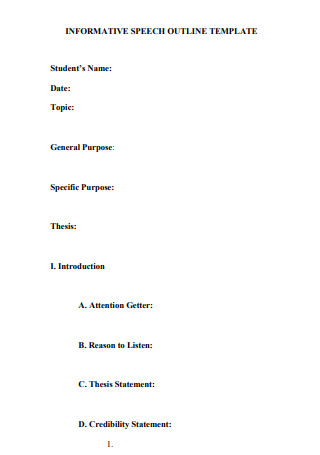

Introduction

Attention Getter: Background information: Credibility: Thesis: Preview:

Key Takeaways

Introductions are foundational to an effective public speech.

- A thesis statement is instrumental to a speech that is well-developed and supported.

- Be sure that you are spending enough time brainstorming strong attention getters and considering your audience’s goal(s) for the introduction.

- A strong thesis will allow you to follow a roadmap throughout the rest of your speech: it is worth spending the extra time to ensure you have a strong thesis statement.

Stand up, Speak out by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Public Speaking Copyright © by Dr. Layne Goodman; Amber Green, M.A.; and Various is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Thesis Statements

What this handout is about.

This handout describes what a thesis statement is, how thesis statements work in your writing, and how you can craft or refine one for your draft.

Introduction

Writing in college often takes the form of persuasion—convincing others that you have an interesting, logical point of view on the subject you are studying. Persuasion is a skill you practice regularly in your daily life. You persuade your roommate to clean up, your parents to let you borrow the car, your friend to vote for your favorite candidate or policy. In college, course assignments often ask you to make a persuasive case in writing. You are asked to convince your reader of your point of view. This form of persuasion, often called academic argument, follows a predictable pattern in writing. After a brief introduction of your topic, you state your point of view on the topic directly and often in one sentence. This sentence is the thesis statement, and it serves as a summary of the argument you’ll make in the rest of your paper.

What is a thesis statement?

A thesis statement:

- tells the reader how you will interpret the significance of the subject matter under discussion.

- is a road map for the paper; in other words, it tells the reader what to expect from the rest of the paper.

- directly answers the question asked of you. A thesis is an interpretation of a question or subject, not the subject itself. The subject, or topic, of an essay might be World War II or Moby Dick; a thesis must then offer a way to understand the war or the novel.

- makes a claim that others might dispute.

- is usually a single sentence near the beginning of your paper (most often, at the end of the first paragraph) that presents your argument to the reader. The rest of the paper, the body of the essay, gathers and organizes evidence that will persuade the reader of the logic of your interpretation.

If your assignment asks you to take a position or develop a claim about a subject, you may need to convey that position or claim in a thesis statement near the beginning of your draft. The assignment may not explicitly state that you need a thesis statement because your instructor may assume you will include one. When in doubt, ask your instructor if the assignment requires a thesis statement. When an assignment asks you to analyze, to interpret, to compare and contrast, to demonstrate cause and effect, or to take a stand on an issue, it is likely that you are being asked to develop a thesis and to support it persuasively. (Check out our handout on understanding assignments for more information.)

How do I create a thesis?

A thesis is the result of a lengthy thinking process. Formulating a thesis is not the first thing you do after reading an essay assignment. Before you develop an argument on any topic, you have to collect and organize evidence, look for possible relationships between known facts (such as surprising contrasts or similarities), and think about the significance of these relationships. Once you do this thinking, you will probably have a “working thesis” that presents a basic or main idea and an argument that you think you can support with evidence. Both the argument and your thesis are likely to need adjustment along the way.

Writers use all kinds of techniques to stimulate their thinking and to help them clarify relationships or comprehend the broader significance of a topic and arrive at a thesis statement. For more ideas on how to get started, see our handout on brainstorming .

How do I know if my thesis is strong?

If there’s time, run it by your instructor or make an appointment at the Writing Center to get some feedback. Even if you do not have time to get advice elsewhere, you can do some thesis evaluation of your own. When reviewing your first draft and its working thesis, ask yourself the following :

- Do I answer the question? Re-reading the question prompt after constructing a working thesis can help you fix an argument that misses the focus of the question. If the prompt isn’t phrased as a question, try to rephrase it. For example, “Discuss the effect of X on Y” can be rephrased as “What is the effect of X on Y?”

- Have I taken a position that others might challenge or oppose? If your thesis simply states facts that no one would, or even could, disagree with, it’s possible that you are simply providing a summary, rather than making an argument.

- Is my thesis statement specific enough? Thesis statements that are too vague often do not have a strong argument. If your thesis contains words like “good” or “successful,” see if you could be more specific: why is something “good”; what specifically makes something “successful”?

- Does my thesis pass the “So what?” test? If a reader’s first response is likely to be “So what?” then you need to clarify, to forge a relationship, or to connect to a larger issue.

- Does my essay support my thesis specifically and without wandering? If your thesis and the body of your essay do not seem to go together, one of them has to change. It’s okay to change your working thesis to reflect things you have figured out in the course of writing your paper. Remember, always reassess and revise your writing as necessary.

- Does my thesis pass the “how and why?” test? If a reader’s first response is “how?” or “why?” your thesis may be too open-ended and lack guidance for the reader. See what you can add to give the reader a better take on your position right from the beginning.

Suppose you are taking a course on contemporary communication, and the instructor hands out the following essay assignment: “Discuss the impact of social media on public awareness.” Looking back at your notes, you might start with this working thesis:

Social media impacts public awareness in both positive and negative ways.

You can use the questions above to help you revise this general statement into a stronger thesis.

- Do I answer the question? You can analyze this if you rephrase “discuss the impact” as “what is the impact?” This way, you can see that you’ve answered the question only very generally with the vague “positive and negative ways.”

- Have I taken a position that others might challenge or oppose? Not likely. Only people who maintain that social media has a solely positive or solely negative impact could disagree.

- Is my thesis statement specific enough? No. What are the positive effects? What are the negative effects?

- Does my thesis pass the “how and why?” test? No. Why are they positive? How are they positive? What are their causes? Why are they negative? How are they negative? What are their causes?

- Does my thesis pass the “So what?” test? No. Why should anyone care about the positive and/or negative impact of social media?

After thinking about your answers to these questions, you decide to focus on the one impact you feel strongly about and have strong evidence for:

Because not every voice on social media is reliable, people have become much more critical consumers of information, and thus, more informed voters.

This version is a much stronger thesis! It answers the question, takes a specific position that others can challenge, and it gives a sense of why it matters.

Let’s try another. Suppose your literature professor hands out the following assignment in a class on the American novel: Write an analysis of some aspect of Mark Twain’s novel Huckleberry Finn. “This will be easy,” you think. “I loved Huckleberry Finn!” You grab a pad of paper and write:

Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn is a great American novel.

You begin to analyze your thesis:

- Do I answer the question? No. The prompt asks you to analyze some aspect of the novel. Your working thesis is a statement of general appreciation for the entire novel.

Think about aspects of the novel that are important to its structure or meaning—for example, the role of storytelling, the contrasting scenes between the shore and the river, or the relationships between adults and children. Now you write:

In Huckleberry Finn, Mark Twain develops a contrast between life on the river and life on the shore.

- Do I answer the question? Yes!

- Have I taken a position that others might challenge or oppose? Not really. This contrast is well-known and accepted.

- Is my thesis statement specific enough? It’s getting there–you have highlighted an important aspect of the novel for investigation. However, it’s still not clear what your analysis will reveal.

- Does my thesis pass the “how and why?” test? Not yet. Compare scenes from the book and see what you discover. Free write, make lists, jot down Huck’s actions and reactions and anything else that seems interesting.

- Does my thesis pass the “So what?” test? What’s the point of this contrast? What does it signify?”

After examining the evidence and considering your own insights, you write:

Through its contrasting river and shore scenes, Twain’s Huckleberry Finn suggests that to find the true expression of American democratic ideals, one must leave “civilized” society and go back to nature.

This final thesis statement presents an interpretation of a literary work based on an analysis of its content. Of course, for the essay itself to be successful, you must now present evidence from the novel that will convince the reader of your interpretation.

Works consulted

We consulted these works while writing this handout. This is not a comprehensive list of resources on the handout’s topic, and we encourage you to do your own research to find additional publications. Please do not use this list as a model for the format of your own reference list, as it may not match the citation style you are using. For guidance on formatting citations, please see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial . We revise these tips periodically and welcome feedback.

Anson, Chris M., and Robert A. Schwegler. 2010. The Longman Handbook for Writers and Readers , 6th ed. New York: Longman.

Lunsford, Andrea A. 2015. The St. Martin’s Handbook , 8th ed. Boston: Bedford/St Martin’s.

Ramage, John D., John C. Bean, and June Johnson. 2018. The Allyn & Bacon Guide to Writing , 8th ed. New York: Pearson.

Ruszkiewicz, John J., Christy Friend, Daniel Seward, and Maxine Hairston. 2010. The Scott, Foresman Handbook for Writers , 9th ed. Boston: Pearson Education.

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

10.9: Informative Speech Examples

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 147587

- Lisa Coleman, Thomas King, & William Turner

- Southwest Tennessee Community College

“Getting Plugged In”

TED Talks as a Model of Effective Informative Speaking Over the past few years, I have heard more and more public speaking teachers mention their use of TED speeches in their classes. What started in 1984 as a conference to gather people involved in Technology, Entertainment, and Design has now turned into a worldwide phenomenon that is known for its excellent speeches and presentations, many of which are informative in nature. [1] The motto of TED is “Ideas worth spreading,” which is in keeping with the role that we should occupy as informative speakers. We should choose topics that are worth speaking about and then work to present them in such a way that audience members leave with “take-away” information that is informative and useful. TED fits in with the purpose of the “Getting Plugged In” feature in this book because it has been technology-focused from the start. For example, Andrew Blum’s speech focuses on the infrastructure of the Internet, and Pranav Mistry’s speech focuses on a new technology he developed that allows for more interaction between the physical world and the world of data. Even speakers who don’t focus on technology still skillfully use technology in their presentations, as is the case with David Gallo’s speech about exotic underwater life. Here are links to all these speeches:

- Andrew Blum’s speech: What Is the Internet, Really?

- Pranav Mistry’s speech: The Thrilling Potential of Sixth Sense Technology.

- David Gallo’s speech: Underwater Astonishments.

- What can you learn from the TED model and/or TED speakers that will help you be a better informative speaker?

- In what innovative and/or informative ways do the speakers reference or incorporate technology in their speeches?

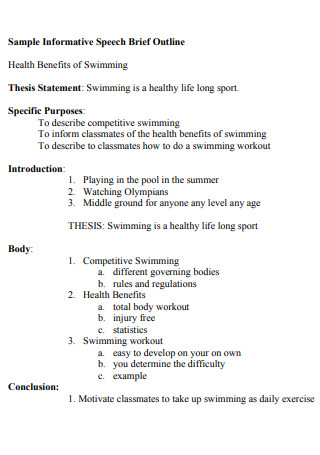

Example Outlines

Sample speech 1.

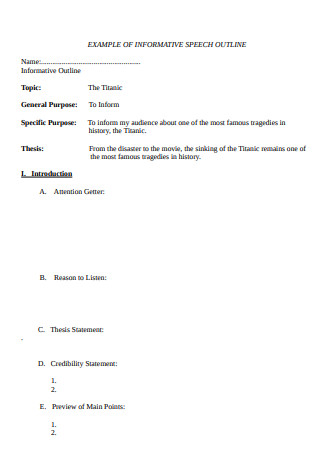

Title: Going Green in the World of Education

General Purpose : To inform

Specific Purpose : To inform my audience about ways in which schools are going green.

Thesis Statement : The green movement has transformed school buildings, how teachers teach, and the environment in which students learn.

Introduction

Attention Getter: Did you know that attending or working at a green school can lead students and teachers to have fewer health problems? Did you know that allowing more daylight into school buildings increases academic performance and can lessen attention and concentration challenges? Well, the research I will cite in my speech supports both of these claims, and these are just two of the many reasons why more schools, both grade schools, and colleges, are going green.

Introduction of Topic: Today, I’m going to inform you about the green movement that is affecting many schools.

Credibility and Relevance: Because of my own desire to go into the field of education, I decided to research how schools are going green in the United States. But it’s not just current and/or future teachers that will be affected by this trend. As students at Eastern Illinois University, you are already asked to make “greener” choices. Whether it’s the little signs in the dorm rooms that ask you to turn off your lights when you leave the room, the reusable water bottles that were given out on move-in day, or even our new Renewable Energy Center, the list goes on and on. Additionally, younger people in our lives, whether they be future children or younger siblings, or relatives, will likely be affected by this continuing trend.

Thesis/Preview: In order to better understand what makes a “green school,” we need to learn about how K–12 schools are going green, how college campuses are going green, and how these changes affect students and teachers.

Transition: I’ll begin with how K–12 schools are going green.

I. According to the “About Us” section on their official website, the US Green Building Council was established in 1993 with the mission to promote sustainability in the building and construction industry, and it is this organization that is responsible for the Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design, or LEED, which is a well-respected green building certification system.

A. While homes, neighborhoods, and businesses can also pursue LEED certification, I’ll focus today on K–12 schools and college campuses.

1. It’s important to note that principles of “going green” can be applied to the planning of a building from its first inception or be retroactively applied to existing buildings.

a. A 2011 article by Ash in Education Week notes that the pathway to creating a greener school is flexible based on the community and its needs.

i. In order to garner support for green initiatives, the article recommends that local leaders like superintendents, mayors, and college administrators become involved in the green movement. ii. Once local leaders are involved, the community, students, parents, faculty, and staff can be involved by serving on a task force, hosting a summit or conference, and implementing lessons about sustainability into everyday conversations and school curriculum.

b. The US Green Building Council’s website also includes a tool kit with a lot of information about how to “green” existing schools.

2. Much of the efforts to green schools have focused on K–12 schools and districts, but what makes a school green?

a. According to the US Green Building Council’s Center for Green Schools, green school buildings conserve energy and natural resources.

i. For example, Fossil Ridge High School in Fort Collins, Colorado, was built in 2006 and received LEED certification because it has automatic light sensors to conserve electricity and uses wind energy to offset nonrenewable energy use.

ii. To conserve water, the school uses a pond for irrigation, has artificial turf on athletic fields, and installed low-flow toilets and faucets.

iii. According to the 2006 report by certified energy manager Gregory Kats titled “Greening America’s Schools,” a LEED-certified school uses 30–50 percent less energy, 30 percent less water, and reduces carbon dioxide emissions by 40 percent compared to a conventional school.

b. The Center for Green Schools also presents case studies that show how green school buildings also create healthier learning environments.

i. Many new building materials, carpeting, and furniture contain chemicals that are released into the air, which reduces indoor air quality.

ii. So green schools purposefully purchase materials that are low in these chemicals.

iii. Natural light and fresh air have also been shown to promote a healthier learning environment, so green buildings allow more daylight in and include functioning windows.

Transition: As you can see, K–12 schools are becoming greener; college campuses are also starting to go green.

II. Examples from the University of Denver and Eastern Illinois University show some of the potentials for greener campuses around the country.

A. The University of Denver is home to the nation’s first “green” law school.

1. According to the Sturm College of Law’s website, the building was designed to use 40 percent less energy than a conventional building through the use of movement-sensor lighting; high-performance insulation in the walls, floors, and roof; and infrared sensors on water faucets and toilets.

2. Electric car recharging stations were also included in the parking garage, and the building has extra bike racks and even showers that students and faculty can use to freshen up if they bike or walk to school or work.

B. Eastern Illinois University has also made strides toward a more green campus.

1. Some of the dining halls on campus have gone “trayless,” which according to a 2009 article by Calder in the journal Independent School has the potential to dramatically reduce the amount of water and chemical use, since there are no longer trays to wash, and also helps reduce food waste since people take less food without a tray.

2. The biggest change on campus has been the opening of the Renewable Energy Center in 2011, which according to EIU’s website is one of the largest biomass renewable energy projects in the country.

a. The Renewable Energy Center uses slow-burn technology to use wood chips that are a byproduct of the lumber industry that would normally be discarded.

b. This helps reduce our dependency on our old coal-fired power plant, which reduces greenhouse gas emissions.

c. The project was the first known power plant to be registered with the US Green Building Council and is on track to receive LEED certification.

Transition: All these efforts to go green in K–12 schools and on college campuses will obviously affect students and teachers at the schools.

III. The green movement affects students and teachers in a variety of ways.

A. Research shows that going green positively affects a student’s health.

1. Many schools are literally going green by including more green spaces such as recreation areas, gardens, and greenhouses, which according to a 2010 article in the Journal of Environmental Education by University of Colorado professor Susan Strife has been shown to benefit a child’s cognitive skills, especially in the areas of increased concentration and attention capacity.

2. Additionally, the report I cited earlier, “Greening America’s Schools,” states that the improved air quality in green schools can lead to a 38 percent reduction in asthma incidents and that students in “green schools” had 51 percent less chance of catching a cold or the flu compared to children in conventional schools.

B. Standard steps taken to green schools can also help students academically.

1. The report “Greening America’s Schools” notes that a recent synthesis of fifty-three studies found that more daylight in the school building leads to higher academic achievement.

2. The report also provides data that show how a healthier environment in green schools leads to better attendance and that in Washington, DC, and Chicago, schools improved their performance on standardized tests by 3–4 percent.

C. Going green can influence teachers’ lesson plans as well their job satisfaction and physical health.

1. There are several options for teachers who want to “green” their curriculum.

a. According to the article in Education Week that I cited earlier, the Sustainability Education Clearinghouse is a free online tool that provides K–12 educators with the ability to share sustainability-oriented lesson ideas.

b. The Center for Green Schools also provides resources for all levels of teachers, from kindergarten to college, that can be used in the classroom.

2. The report “Greening America’s Schools” claims that the overall improved working environment that a green school provides leads to higher teacher retention and less teacher turnover.

3. Just as students see health benefits from green schools, so do teachers, as the same report shows that teachers in these schools get sick less, resulting in a decrease of sick days by 7 percent.

Transition to conclusion and summary of importance: In summary, the going-green era has impacted every aspect of education in our school systems.

Review of main points: From K–12 schools to college campuses like ours, to the students and teachers in the schools, the green movement is changing the way we think about education and our environment.

Closing statement: As Glenn Cook, the editor in chief of the American School Board Journal , states on the Center for Green Schools’s website, “The green schools movement is the biggest thing to happen to education since the introduction of technology to the classroom.”

Works Cited

Ash, K. (2011). “Green schools” benefit budgets and students, report says. Education Week , 30 (32), 10.

Calder, W. (2009). Go green, save green. Independent School , 68 (4), 90–93.

The Center for Green Schools. (n.d.). K–12: How. Retrieved from http://www.centerforgreenschools.org/main-nav/k-12/buildings.aspx

Eastern Illinois University. (n.d.). Renewable Energy Center. Retrieved from www.eiu.edu/sustainability/eiu_renewable.php

Kats, G. (2006). Greening America’s schools: Costs and benefits. A Capital E Report. Retrieved from http://www.usgbc.org/ShowFile.aspx?DocumentID=2908

Strife, S. (2010). Reflecting on environmental education: Where is our place in the green movement? Journal of Environmental Education , 41 (3), 179–191. doi:10.1080/00958960903295233

Sturm College of Law. (n.d.). About DU law: Building green. Retrieved from www.law.du.edu/index.php/about/building-green

USGBC. (n.d.). About us. US Green Building Council . Retrieved from https://new.usgbc.org/about

Sample Speech 2

Informative Speech on Lord Byron

I. Attention Grabber : Imagine an eleven-year-old boy who has been beaten and sexually abused repeatedly by the very person who is supposed to take care of him.

II. Reveal Topic : This is one of the many hurdles that George Gordon, better known as Lord Byron, overcame during his childhood. Lord Byron was also a talented poet with the ability to transform his life into the words of his poetry. Byron became a serious poet by the age of fifteen and he was first published in 1807 at the age of nineteen. Lord Byron was a staunch believer in freedom and equality, so he gave most of his fortune, and in the end, his very life, supporting the Greek war for independence.

III. Credibility : I learned all about Lord Byron when I took Humanities 1201 last semester.

IV. Thesis/Preview: Today, I will discuss his childhood, poetry, and legacy.

I. Lord Byron was born on January 22, 1788, to Captain John Byron and Catherine Gordon Byron.

A. According to Paul Trueblood, the author of Lord Byron, Lord Byron’s father only married Catherine for her dowry, which he quickly went through, leaving his wife and child nearly penniless.

B. By the age of two, Lord Byron and his mother had moved to Aberdeen in Scotland and shortly thereafter, his father died in France at the age of thirty-six.

C. Lord Byron was born with a clubbed right foot, which is a deformity that caused his foot to turn sideways instead of remaining straight, and his mother had no money to seek treatment for this painful and embarrassing condition.

1. He would become very upset and fight anyone who even spoke of his lameness.

2. Despite his handicap, Lord Byron was very active and liked competing with the other boys.

D. At the age of ten, his grand-uncle died leaving him the title as the sixth Baron Byron of Rochdale.

1. With this title, he also inherited Newstead Abbey, a dilapidated estate that was in great need of repair.

2. Because the Abbey was in Nottinghamshire England, he and his mother moved there and stayed at the abbey until it was rented out to pay for the necessary repairs.

3. During this time, May Gray, Byron’s nurse had already begun physically and sexually abusing him.

4. A year passed before he finally told his guardian, John Hanson, about May’s abuse; she was fired immediately.

5. Unfortunately the damage had already been done.

6. In the book Lord Byron, it is stated that years later he wrote “My passions were developed very early- so early, that few would believe me if I were to state the period, and the facts which accompanied it.”

E. Although Lord Byron had many obstacles to overcome during his childhood, he became a world-renowned poet by the age of 24.

II. Lord Byron experienced the same emotions we all do, but he was able to express those emotions in the form of his poetry and share them with the world.

A. According to Horace Gregory, The author of Poems of George Gordon, Lord Byron, the years from 1816 through 1824 is when Lord Byron was most known throughout Europe.

B. But according to Paul Trueblood, Childe Harold was published in 1812 and became one of the best-selling works of literature in the 19th century.

1. Childe Harold was written while Lord Byron was traveling through Europe after graduating from Trinity College.

2. Many authors such as Trueblood, and Garrett, the author of George Gordon, Lord Byron, express their opinion that Childe Harold is an autobiography about Byron and his travels.

C. Lord Byron often wrote about the ones he loved the most, such as the poem “She Walks in Beauty” written about his cousin Anne Wilmont, and “Stanzas for Music” written for his half-sister, Augusta Leigh.

D. He was also an avid reader of the Old Testament and would write poetry about stories from the Bible that he loved.

1. One such story was about the last king of Babylon.

2. This poem was called the “Vision of Belshazzar,” and is very much like the bible version in the book of Daniel.

E. Although Lord Byron is mostly known for his talents as a poet, he was also an advocate for the Greek war for independence.

III. Lord Byron, after his self-imposed exile from England, took the side of the Greeks in their war for freedom from Turkish rule.

A. Byron arrived in Greece in 1823 during a civil war.

1. The Greeks were too busy fighting amongst themselves to come together to form a formidable army against the Turks.

2. According to Martin Garrett, Lord Byron donated money to refit the Greeks' fleet of ships but did not immediately get involved in the situation.

3. He had doubts as to if or when the Greeks would ever come together and agree long enough to make any kind of a difference in their war effort.

4. Eventually the Greeks united and began their campaign for the Greek War of Independence.

5. He began pouring more and more of his fortune into the Greek army and finally accepted a position to oversee a small group of men sailing to Missolonghi.

B. Lord Byron set sail for Missolonghi in Western Greece in 1824.

1. He took a commanding position over a small number of the Greek army despite his lack of military training.

2. He had also made plans to attack a Turkish-held fortress but became very ill before the plans were ever carried through.

C. Lord Byron died on April 19, 1824, at the age of 36 due to the inexperienced doctors who continued to bleed him while he suffered from a severe fever.

1. After Lord Byron’s death, the Greek War of Independence, due to his support, received more foreign aid which led to their eventual victory in 1832.

2. Lord Byron is hailed as a national hero by the Greek nation.

3. Many tributes such as statues and road names have been devoted to Lord Byron since the time of his death.

I. Transition into conclusion/Review of main points: In conclusion, Lord Byron overcame great physical hardships to become a world-renowned poet, and is seen as a hero to the Greek nation, and is mourned by them still today. I have chosen not to focus on Lord Byron’s more liberal way of life, but rather to focus on his accomplishments in life. He was a man who owed no loyalty to Greece, yet gave his life to support their cause.

II. Closing statement: Most of the world will remember Lord Byron primarily through his written attributes, but Greece will always remember him as the “Trumpet Voice of Liberty.”

Fleming, N., “The VARK Helpsheets,” accessed March 6, 2012, http://www.vark-learn.com/english/page.asp?p=helpsheets .

Janusik, L., “Listening Facts,” accessed March 6, 2012, d1025403.site.myhosting.com/f.org/Facts.htm.

Olbricht, T. H., Informative Speaking (Glenview, IL: Scott, Foresman, 1968), 1–12.

Oxford English Dictionary Online, accessed March 6, 2012, http://www.oed.com .

The Past in Pictures, “Teaching Using Movies: Anachronisms!” accessed March 6, 2012, www.thepastinthepictures.wild.ctoryunit!.htm.

Scholasticus K, “Anachronism Examples in Literature,” February 2, 2012, accessed March 6, 2012, www.buzzle.com/articles/anachronism-examples-in-literature.html.

Society for Technical Communication, “Defining Technical Communication,” accessed March 6, 2012, http://www.stc.org/about-stc/the-profession-all-about-technical-communication/defining-tc .

Verderber, R., Essentials of Informative Speaking: Theory and Contexts (Belmont, CA: Wadsworth, 1991), 3.

Vuong, A., “Wanna Read That QR Code? Get the Smartphone App,” The Denver Post , April 18, 2011, accessed March 6, 2012, http://www.denverpost.com/business/ci_17868932 .

- “About TED,” accessed October 23, 2012, http://www.ted.com/pages/about . ↵

- Speech Crafting →

Public Speaking: Developing a Thesis Statement In a Speech

Understanding the purpose of a thesis statement in a speech

Diving headfirst into the world of public speaking, it’s essential to grasp the role of a thesis statement in your speech. Think of it as encapsulating the soul of your speech within one or two sentences.

It’s the declarative sentence that broadcasts your intent and main idea to captivate audiences from start to finish. More than just a preview, an effective thesis statement acts as a roadmap guiding listeners through your thought process.

Giving them that quick glimpse into what they can anticipate helps keep their attention locked in.

As you craft this central hub of information, understand that its purpose is not limited to informing alone—it could be meant also to persuade or entertain based on what you aim for with your general purpose statement.

This clear focus is pivotal—it shapes each aspect of your talk, easing understanding for the audience while setting basic goals for yourself throughout the speech-making journey. So whether you are rallying rapturous applause or instigating intellectual insight, remember—your thesis statement holds power like none other! Its clarity and strength can transition between being valuable sidekicks in introductions towards becoming triumphant heroes by concluding lines.

Identifying the main idea to develop a thesis statement

In crafting a compelling speech, identifying the main idea to develop a thesis statement acts as your compass. This process is a crucial step in speech preparation that steers you towards specific purpose.

Think of your central idea as the seed from which all other elements in your speech will grow.

To pinpoint it, start by brainstorming broad topics that interest or inspire you. From this list, choose one concept that stands out and begin to narrow it down into more specific points. It’s these refined ideas that form the heart of your thesis statement — essentially acting as signposts leading the audience through your narrative journey.

Crafting an effective thesis statement requires clarity and precision. This means keeping it concise without sacrificing substance—a tricky balancing act even for public speaking veterans! The payoff though? A well-developed thesis statement provides structure to amplifying your central idea and guiding listeners smoothly from point A to B.

It’s worth noting here: just like every speaker has their own unique style, there are multiple ways of structuring a thesis statement too. But no matter how you shape yours, ensuring it resonates with both your overarching message and audience tastes will help cement its effectiveness within your broader presentation context.

Analyzing the audience to tailor the thesis statement

Audience analysis is a crucial first step for every public speaker. This process involves adapting the message to meet the audience’s needs, a thoughtful approach that considers cultural diversity and ensures clear communication.

Adapting your speech to resonate with your target audience’s interests, level of understanding, attitudes and beliefs can significantly affect its impact.

Crafting an appealing thesis statement hinges on this initial stage of audience analysis. As you analyze your crowd, focus on shaping a specific purpose statement that reflects their preferences yet stays true to the objective of your speech—capturing your main idea in one or two impactful sentences.

This balancing act demands strategy; however, it isn’t impossible. Taking into account varying aspects such as culture and perceptions can help you tailor a well-received thesis statement. A strong handle on these elements allows you to select language and tones best suited for them while also reflecting the subject at hand.

Ultimately, putting yourself in their shoes helps increase message clarity which crucially leads to acceptance of both you as the speaker and your key points – all embodied within the concise presentation of your tailor-made thesis statement.

Brainstorming techniques to generate thesis statement ideas

Leveraging brainstorming techniques to generate robust thesis statement ideas is a power move in public speaking. This process taps into the GAP model, focusing on your speech’s Goals, Audience, and Parameters for seamless target alignment.

Dive into fertile fields of thought and let your creativity flow unhindered like expert David Zarefsky proposes.

Start by zeroing in on potential speech topics then nurture them with details till they blossom into fully-fledged arguments. It’s akin to turning stones into gems for the eye of your specific purpose statement.

Don’t shy away from pushing the envelope – sometimes out-of-the-box suggestions give birth to riveting speeches! Broaden your options if parameters are flexible but remember focus is key when aiming at narrow targets.

The beauty lies not just within topic generation but also formulation of captivating informative or persuasive speech thesis statements; both fruits harvested from a successful brainstorming session.

So flex those idea muscles, encourage intellectual growth and watch as vibrant themes spring forth; you’re one step closer to commanding attention!

Remember: Your thesis statement is the heartbeat of your speech – make it strong using brainstorming techniques and fuel its pulse with evidence-backed substance throughout your presentation.

Narrowing down the thesis statement to a specific topic

Crafting a compelling thesis statement for your speech requires narrowing down a broad topic to a specific focus that can be effectively covered within the given time frame. This step is crucial as it helps you maintain clarity and coherence throughout your presentation.

Start by brainstorming various ideas related to your speech topic and then analyze them critically to identify the most relevant and interesting points to discuss. Consider the specific purpose of your speech and ask yourself what key message you want to convey to your audience.

By narrowing down your thesis statement, you can ensure that you address the most important aspects of your chosen topic, while keeping it manageable and engaging for both you as the speaker and your audience.

Choosing the appropriate language and tone for the thesis statement

Crafting the appropriate language and tone for your thesis statement is a crucial step in developing a compelling speech. Your choice of language and tone can greatly impact how your audience perceives your message and whether they are engaged or not.

When choosing the language for your thesis statement, it’s important to consider the level of formality required for your speech. Are you speaking in a professional setting or a casual gathering? Adjusting your language accordingly will help you connect with your audience on their level and make them feel comfortable.

Additionally, selecting the right tone is essential to convey the purpose of your speech effectively. Are you aiming to inform, persuade, or entertain? Each objective requires a different tone: informative speeches may call for an objective and neutral tone, persuasive speeches might benefit from more assertive language, while entertaining speeches can be lighthearted and humorous.

Remember that clarity is key when crafting your thesis statement’s language. Using concise and straightforward wording will ensure that your main idea is easily understood by everyone in the audience.

By taking these factors into account – considering formality, adapting to objectives, maintaining clarity – you can create a compelling thesis statement that grabs attention from the start and sets the stage for an impactful speech.

Incorporating evidence to support the thesis statement

Incorporating evidence to support the thesis statement is a critical aspect of delivering an effective speech. As public speakers, we understand the importance of backing up our claims with relevant and credible information.

When it comes to incorporating evidence, it’s essential to select facts, examples, and opinions that directly support your thesis statement.

To ensure your evidence is relevant and reliable, consider conducting thorough research on the topic at hand. Look for trustworthy sources such as academic journals, respected publications, or experts in the field.

By choosing solid evidence that aligns with your message, you can enhance your credibility as a speaker.

When presenting your evidence in the speech itself, be sure to keep it concise and clear. Avoid overwhelming your audience with excessive details or data. Instead, focus on selecting key points that strengthen your argument while keeping their attention engaged.

Remember that different types of evidence can be utilized depending on the nature of your speech. You may include statistical data for a persuasive presentation or personal anecdotes for an informative talk.

The choice should reflect what will resonate best with your audience and effectively support your thesis statement.

By incorporating strong evidence into our speeches, we not only bolster our arguments but also build trust with our listeners who recognize us as reliable sources of information. So remember to choose wisely when including supporting material – credibility always matters when making an impact through public speaking.

Avoiding common mistakes when developing a thesis statement

Crafting an effective thesis statement is vital for public speakers to deliver a compelling and focused speech. To avoid common mistakes when developing a thesis statement , it is essential to be aware of some pitfalls that can hinder the impact of your message.

One mistake to steer clear of is having an incomplete thesis statement. Ensure that your thesis statement includes all the necessary information without leaving any key elements out. Additionally, avoid wording your thesis statement as a question as this can dilute its potency.

Another mistake to watch out for is making statements of fact without providing evidence or support. While it may seem easy to write about factual information, it’s important to remember that statements need to be proven and backed up with credible sources or examples.

To create a more persuasive argument, avoid using phrases like “I believe” or “I feel.” Instead, take a strong stance in your thesis statement that encourages support from the audience. This will enhance your credibility and make your message more impactful.

By avoiding these common mistakes when crafting your thesis statement, you can develop a clear, engaging, and purposeful one that captivates your audience’s attention and guides the direction of your speech effectively.

Key words: Avoiding common mistakes when developing a thesis statement – Crafting a thesis statement – Effective thesis statements – Public speaking skills – Errors in the thesis statement – Enhancing credibility

Revising the thesis statement to enhance clarity and coherence

Revising the thesis statement is a crucial step in developing a clear and coherent speech. The thesis statement serves as the main idea or argument that guides your entire speech, so it’s important to make sure it effectively communicates your message to the audience.

To enhance clarity and coherence in your thesis statement, start by refining and strengthening it through revision . Take into account any feedback you may have received from others or any new information you’ve gathered since initially developing the statement.

Consider if there are any additional points or evidence that could further support your main idea.

As you revise, focus on clarifying the language and tone of your thesis statement. Choose words that resonate with your audience and clearly convey your point of view. Avoid using technical jargon or overly complicated language that might confuse or alienate listeners.

Another important aspect of revising is ensuring that your thesis statement remains focused on a specific topic. Narrow down broad ideas into more manageable topics that can be explored thoroughly within the scope of your speech.

Lastly, consider incorporating evidence to support your thesis statement. This could include statistics, examples, expert opinions, or personal anecdotes – whatever helps strengthen and validate your main argument.

By carefully revising your thesis statement for clarity and coherence, you’ll ensure that it effectively conveys your message while capturing the attention and understanding of your audience at large.

Testing the thesis statement to ensure it meets the speech’s objectives.

Testing the thesis statement is a crucial step to ensure that it effectively meets the objectives of your speech. By testing the thesis statement , you can assess its clarity, relevance, and impact on your audience.

One way to test your thesis statement is to consider its purpose and intent. Does it clearly communicate what you want to achieve with your speech? Is it concise and specific enough to guide your content?.

Another important aspect of testing the thesis statement is analyzing whether it aligns with the needs and interests of your audience. Consider their background knowledge, values, and expectations.

Will they find the topic engaging? Does the thesis statement address their concerns or provide valuable insights?.

In addition to considering purpose and audience fit, incorporating supporting evidence into your speech is vital for testing the effectiveness of your thesis statement. Ensure that there is relevant material available that supports your claim.

To further enhance clarity and coherence in a tested thesis statement, revise it if necessary based on feedback from others or through self-reflection. This will help refine both language choices and overall effectiveness.

By thoroughly testing your thesis statement throughout these steps, you can confidently develop a clear message for an impactful speech that resonates with your audience’s needs while meeting all stated objectives.

1. What is a thesis statement in public speaking?

A thesis statement in public speaking is a concise and clear sentence that summarizes the main point or argument of a speech. It serves as a roadmap for the audience, guiding them through the speech and helping them understand its purpose.

2. How do I develop an effective thesis statement for a speech?

To develop an effective thesis statement for a speech, start by identifying your topic and determining what specific message you want to convey to your audience. Then, clearly state this message in one or two sentences that capture the main idea of your speech.

3. Why is it important to have a strong thesis statement in public speaking?

Having a strong thesis statement in public speaking helps you stay focused on your main argument throughout the speech and ensures that your audience understands what you are trying to communicate. It also helps establish credibility and authority as you present well-supported points related to your thesis.

4. Can my thesis statement change during my speech preparation?

Yes, it is possible for your thesis statement to evolve or change during the preparation process as you gather more information or refine your ideas. However, it’s important to ensure that any changes align with the overall purpose of your speech and still effectively guide the content and structure of your presentation.

Speechwriting

8 Purpose and Thesis

Speechwriting Essentials

In this chapter . . .

As discussed in the chapter on Speaking Occasion , speechwriting begins with careful analysis of the speech occasion and its given circumstances, leading to the choice of an appropriate topic. As with essay writing, the early work of speechwriting follows familiar steps: brainstorming, research, pre-writing, thesis, and so on.

This chapter focuses on techniques that are unique to speechwriting. As a spoken form, speeches must be clear about the purpose and main idea or “takeaway.” Planned redundancy means that you will be repeating these elements several times over during the speech.

Furthermore, finding purpose and thesis are essential whether you’re preparing an outline for extemporaneous delivery or a completely written manuscript for presentation. When you know your topic, your general and specific purpose, and your thesis or central idea, you have all the elements you need to write a speech that is focused, clear, and audience friendly.

Recognizing the General Purpose

Speeches have traditionally been grouped into one of three categories according to their primary purpose: 1) to inform, 2) to persuade, or 3) to inspire, honor, or entertain. These broad goals are commonly known as the general purpose of a speech . Earlier, you learned about the actor’s tool of intention or objectives. The general purpose is like a super-objective; it defines the broadest goal of a speech. These three purposes are not necessarily exclusive to the others. A speech designed to be persuasive can also be informative and entertaining. However, a speech should have one primary goal. That is its general purpose.

Why is it helpful to talk about speeches in such broad terms? Being perfectly clear about what you want your speech to do or make happen for your audience will keep you focused. You can make a clearer distinction between whether you want your audience to leave your speech knowing more (to inform), or ready to take action (to persuade), or feeling something (to inspire)

It’s okay to use synonyms for these broad categories. Here are some of them:

- To inform could be to explain, to demonstrate, to describe, to teach.

- To persuade could be to convince, to argue, to motivate, to prove.

- To inspire might be to honor, or entertain, to celebrate, to mourn.

In summary, the first question you must ask yourself when starting to prepare a speech is, “Is the primary purpose of my speech to inform, to persuade, or to inspire?”

Articulating Specific Purpose

A specific purpose statement builds upon your general purpose and makes it specific (as the name suggests). For example, if you have been invited to give a speech about how to do something, your general purpose is “to inform.” Choosing a topic appropriate to that general purpose, you decide to speak about how to protect a personal from cyberattacks. Now you are on your way to identifying a specific purpose.

A good specific purpose statement has three elements: goal, target audience, and content.

If you think about the above as a kind of recipe, then the first two “ingredients” — your goal and your audience — should be simple. Words describing the target audience should be as specific as possible. Instead of “my peers,” you could say, for example, “students in their senior year at my university.”

The third ingredient in this recipe is content, or what we call the topic of your speech. This is where things get a bit difficult. You want your content to be specific and something that you can express succinctly in a sentence. Here are some common problems that speakers make in defining the content, and the fix:

Now you know the “recipe” for a specific purpose statement. It’s made up of T o, plus an active W ord, a specific A udience, and clearly stated C ontent. Remember this formula: T + W + A + C.

A: for a group of new students

C: the term “plagiarism”

Here are some further examples a good specific purpose statement:

- To explain to a group of first-year students how to join a school organization.

- To persuade the members of the Greek society to take a spring break trip in Daytona Beach.

- To motivate my classmates in English 101 to participate in a study abroad program.

- To convince first-year students that they need at least seven hours of sleep per night to do well in their studies.

- To inspire my Church community about the accomplishments of our pastor.

The General and Specific Purpose Statements are writing tools in the sense that they help you, as a speechwriter, clarify your ideas.

Creating a Thesis Statement

Once you are clear about your general purpose and specific purpose, you can turn your attention to crafting a thesis statement. A thesis is the central idea in an essay or a speech. In speechwriting, the thesis or central idea explains the message of the content. It’s the speech’s “takeaway.” A good thesis statement will also reveal and clarify the ideas or assertions you’ll be addressing in your speech (your main points). Consider this example:

General Purpose: To persuade. Specific Purpose: To motivate my classmates in English 101 to participate in a study abroad program. Thesis: A semester-long study abroad experience produces lifelong benefits by teaching you about another culture, developing your language skills, and enhancing your future career prospects.

The difference between a specific purpose statement and a thesis statement is clear in this example. The thesis provides the takeaway (the lifelong benefits of study abroad). It also points to the assertions that will be addressed in the speech. Like the specific purpose statement, the thesis statement is a writing tool. You’ll incorporate it into your speech, usually as part of the introduction and conclusion.

All good expository, rhetorical, and even narrative writing contains a thesis. Many students and even experienced writers struggle with formulating a thesis. We struggle when we attempt to “come up with something” before doing the necessary research and reflection. A thesis only becomes clear through the thinking and writing process. As you develop your speech content, keep asking yourself: What is important here? If the audience can remember only one thing about this topic, what do I want them to remember?

Example #2: General Purpose: To inform Specific Purpose: To demonstrate to my audience the correct method for cleaning a computer keyboard. Central Idea: Your computer keyboard needs regular cleaning to function well, and you can achieve that in four easy steps.

Example # 3 General Purpose: To Inform Specific Purpose: To describe how makeup is done for the TV show The Walking Dead . Central Idea: The wildly popular zombie show The Walking Dead achieves incredibly scary and believable makeup effects, and in the next few minutes I will tell you who does it, what they use, and how they do it.

Notice in the examples above that neither the specific purpose nor the central idea ever exceeds one sentence. If your central idea consists of more than one sentence, then you are probably including too much information.

Problems to Avoid

The first problem many students have in writing their specific purpose statement has already been mentioned: specific purpose statements sometimes try to cover far too much and are too broad. For example:

“To explain to my classmates the history of ballet.”

Aside from the fact that this subject may be difficult for everyone in your audience to relate to, it’s enough for a three-hour lecture, maybe even a whole course. You’ll probably find that your first attempt at a specific purpose statement will need refining. These examples are much more specific and much more manageable given the limited amount of time you’ll have.

- To explain to my classmates how ballet came to be performed and studied in the U.S.

- To explain to my classmates the difference between Russian and French ballet.

- To explain to my classmates how ballet originated as an art form in the Renaissance.

- To explain to my classmates the origin of the ballet dancers’ clothing.

The second problem happens when the “communication verb” in the specific purpose does not match the content; for example, persuasive content is paired with “to inform” or “to explain.” Can you find the errors in the following purpose statements?

- To inform my audience why capital punishment is unconstitutional. (This is persuasive. It can’t be informative since it’s taking a side)

- To persuade my audience about the three types of individual retirement accounts. (Even though the purpose statement says “persuade,” it isn’t persuading the audience of anything. It is informative.)

- To inform my classmates that Universal Studios is a better theme park than Six Flags over Georgia. (This is clearly an opinion; hence it is a persuasive speech and not merely informative)

The third problem exists when the content part of the specific purpose statement has two parts. One specific purpose is enough. These examples cover two different topics.

- To explain to my audience how to swing a golf club and choose the best golf shoes.

- To persuade my classmates to be involved in the Special Olympics and vote to fund better classes for the intellectually disabled.

To fix this problem of combined or hybrid purposes, you’ll need to select one of the topics in these examples and speak on that one alone.

The fourth problem with both specific purpose and central idea statements is related to formatting. There are some general guidelines that need to be followed in terms of how you write out these elements of your speech:

- Don’t write either statement as a question.

- Always use complete sentences for central idea statements and infinitive phrases (beginning with “to”) for the specific purpose statement.

- Use concrete language (“I admire Beyoncé for being a talented performer and businesswoman”) and avoid subjective or slang terms (“My speech is about why I think Beyoncé is the bomb”) or jargon and acronyms (“PLA is better than CBE for adult learners.”)

There are also problems to avoid in writing the central idea statement. As mentioned above, remember that:

- The specific purpose and central idea statements are not the same thing, although they are related.

- The central idea statement should be clear and not complicated or wordy; it should “stand out” to the audience. As you practice delivery, you should emphasize it with your voice.

- The central idea statement should not be the first thing you say but should follow the steps of a good introduction as outlined in the next chapters.

You should be aware that all aspects of your speech are constantly going to change as you move toward the moment of giving your speech. The exact wording of your central idea may change, and you can experiment with different versions for effectiveness. However, your specific purpose statement should not change unless there is a good reason to do so. There are many aspects to consider in the seemingly simple task of writing a specific purpose statement and its companion, the central idea statement. Writing good ones at the beginning will save you some trouble later in the speech preparation process.

Public Speaking as Performance Copyright © 2023 by Mechele Leon is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Informative Speeches — Types, Topics, and Examples

What is an informative speech?

An informative speech uses descriptions, demonstrations, and strong detail to explain a person, place, or subject. An informative speech makes a complex topic easier to understand and focuses on delivering information, rather than providing a persuasive argument.

Types of informative speeches

The most common types of informative speeches are definition, explanation, description, and demonstration.

A definition speech explains a concept, theory, or philosophy about which the audience knows little. The purpose of the speech is to inform the audience so they understand the main aspects of the subject matter.

An explanatory speech presents information on the state of a given topic. The purpose is to provide a specific viewpoint on the chosen subject. Speakers typically incorporate a visual of data and/or statistics.

The speaker of a descriptive speech provides audiences with a detailed and vivid description of an activity, person, place, or object using elaborate imagery to make the subject matter memorable.

A demonstrative speech explains how to perform a particular task or carry out a process. These speeches often demonstrate the following:

How to do something

How to make something

How to fix something

How something works

How to write an informative speech

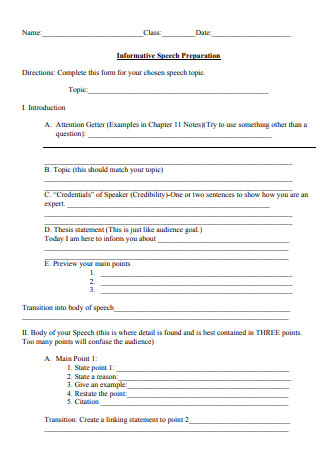

Regardless of the type, every informative speech should include an introduction, a hook, background information, a thesis, the main points, and a conclusion.

Introduction

An attention grabber or hook draws in the audience and sets the tone for the speech. The technique the speaker uses should reflect the subject matter in some way (i.e., if the topic is serious in nature, do not open with a joke). Therefore, when choosing an attention grabber, consider the following:

What’s the topic of the speech?

What’s the occasion?

Who’s the audience?

What’s the purpose of the speech?

Common Attention Grabbers (Hooks)

Ask a question that allows the audience to respond in a non-verbal way (e.g., a poll question where they can simply raise their hands) or ask a rhetorical question that makes the audience think of the topic in a certain way yet requires no response.

Incorporate a well-known quote that introduces the topic. Using the words of a celebrated individual gives credibility and authority to the information in the speech.

Offer a startling statement or information about the topic, which is typically done using data or statistics. The statement should surprise the audience in some way.

Provide a brief anecdote that relates to the topic in some way.

Present a “what if” scenario that connects to the subject matter of the speech.

Identify the importance of the speech’s topic.

Starting a speech with a humorous statement often makes the audience more comfortable with the speaker.

Include any background information pertinent to the topic that the audience needs to know to understand the speech in its entirety.

The thesis statement shares the central purpose of the speech.

Demonstrate

Preview the main ideas that will help accomplish the central purpose. Typically, informational speeches will have an average of three main ideas.

Body paragraphs

Apply the following to each main idea (body) :

Identify the main idea ( NOTE: The main points of a demonstration speech would be the individual steps.)

Provide evidence to support the main idea

Explain how the evidence supports the main idea/central purpose

Transition to the next main idea

Review or restate the thesis and the main points presented throughout the speech.

Much like the attention grabber, the closing statement should interest the audience. Some of the more common techniques include a challenge, a rhetorical question, or restating relevant information:

Provide the audience with a challenge or call to action to apply the presented information to real life.

Detail the benefit of the information.

Close with an anecdote or brief story that illustrates the main points.

Leave the audience with a rhetorical question to ponder after the speech has concluded.

Detail the relevance of the presented information.

Before speech writing, brainstorm a list of informative speech topic ideas. The right topic depends on the type of speech, but good topics can range from video games to disabilities and electric cars to healthcare and mental health.

Informative speech topics

Some common informative essay topics for each type of informational speech include the following:

Informative speech examples

The following list identifies famous informational speeches:

“Duties of American Citizenship” by Theodore Roosevelt

“Duty, Honor, Country” by General Douglas MacArthur

“Strength and Dignity” by Theodore Roosevelt

Explanation

“Give Me Liberty or Give Me Death” by Patrick Henry

“The Decision to Go to the Moon” by John F. Kennedy

“We Shall Fight on the Beaches” by Winston Churchill

Description

“I Have a Dream” by Martin Luther King, Jr.

“Pearl Harbor Address” by Franklin Delano Roosevelt

“Luckiest Man” by Lou Gehrig

Demonstration

The Way to Cook with Julia Child

This Old House with Bob Vila

Bill Nye the Science Guy with Bill Nye

My Speech Class

Public Speaking Tips & Speech Topics

Informative Speech Outline – Template & Examples

Jim Peterson has over 20 years experience on speech writing. He wrote over 300 free speech topic ideas and how-to guides for any kind of public speaking and speech writing assignments at My Speech Class.

Informative speeches are used in our day-to-day lives without even noticing it, we use these speeches whenever we inform someone about a topic they didn’t have much knowledge on, whenever we give someone instructions on how to do something that they haven’t done before, whenever we tell someone about another person. Informative speaking is fairly new to the world of public speaking. Ancient philosophers like Aristotle, Cicero and, Quintilian envisioned public speaking as rhetoric, which is inherently persuasive.

In this article:

What is an Informative Speech?

Here are some ways to prepare for your speech, 1. develop support for your thesis, 2. write your introduction and conclusion, 3. deliver the speech, example of an informative speech outline.

An informative speech is designed to inform the audience about a certain topic of discussion and to provide more information. It is usually used to educate an audience on a particular topic of interest. The main goal of an informative speech is to provide enlightenment concerning a topic the audience knows nothing about. The main types of informative speeches are descriptive, explanatory, demonstrative, and definition speeches. The topics that are covered in an informative speech should help the audience understand the subject of interest better and help them remember what they learned later. The goal of an informative speech isn’t to persuade or sway the audience to the speaker’s point of view but instead to educate. The details need to be laid out to the audience so that they can make an educated decision or learn more about the subject that they are interested in.

It is important for the speaker to think about how they will present the information to the audience.

Informative Speech Preparation

When you are preparing your informative speech, your preparation is the key to a successful speech. Being able to carry your information across to the audience without any misunderstanding or misinterpretation is very important.

1. Choose Your Topic

Pick a topic where you will explain something, help people understand a certain subject, demonstrate how to use something.

2. Make a Thesis Statement

Think about what point you are trying to get across, What is the topic that you want to educate your audience on? “I will explain…” “I will demonstrate how to…” “I will present these findings…”

Can We Write Your Speech?

Get your audience blown away with help from a professional speechwriter. Free proofreading and copy-editing included.

3. Create Points That Support Your Thesis

Take a moment to think about what would support your thesis and take a moment to write the points down on a sheet of paper. Then, take a moment to elaborate on those points and support them.

Typical Organization for an Informative Speech:

How to Speech: 4 Key steps to doing what you are talking about.

Example: Step One: Clean the chicken of any unwanted feathers and giblets. Step Two: Spice the chicken and add stuffings. Step Three: Set oven to 425 degrees Fahrenheit. Step Four: Place chicken in the oven and cook for an hour.

History/ What Happened Speech: Points listing from the beginning to the latest events that you want to discuss in your speech.

Example: First, Harry met Sally. Second, Harry took Sally out to the roadhouse. Third, Harry and Sally started their courtship. Fourth, Harry and Sally moved in together and adopted a dog named Paco.