Best 151+ Phenomenological Research Topics For Students

Phenomenological research, centered on understanding the essence of human experiences, has garnered increasing attention in academic circles. Its popularity in education stems from its unique ability to offer students a deeper understanding of the intricacies of human existence.

In the realm of education, phenomenological research holds significant importance. It empowers students to connect theory with practice, fostering a deeper appreciation for the human dimensions of learning and development.

Through phenomenological investigations, students gain valuable insights into diverse perspectives, enhancing their empathy and understanding.

Research topics in phenomenology are crucial for students as they provide avenues for exploration and growth. These topics allow students to investigate various aspects of human experience, from the mundane to the extraordinary, unveiling layers of meaning and significance.

In this blog, we will explore a wide range of phenomenological research topics tailored specifically for students. From unraveling the essence of consciousness to exploring the lived experiences of individuals in different contexts.

Our aim is to inspire and guide students in their research endeavors, empowering them to uncover the richness of human existence through the lens of phenomenology.

Phenomenological research: What Exactly Is It?

Table of Contents

Phenomenological research delves into the essence of human experiences, aiming to understand the subjective aspects of reality.

It explores how individuals interpret and make sense of the world around them, focusing on their lived experiences rather than objective observations. This approach emphasizes the importance of understanding the unique perspectives and perceptions of individuals, recognizing that reality is shaped by personal experiences.

Phenomenological research involves rigorous reflection, analysis, and interpretation, with the goal of uncovering the underlying meanings and structures inherent in human consciousness.

It offers a valuable framework for exploring the intricacies of human existence and has applications across various disciplines, including psychology, sociology, and education.

Criteria for Selecting Phenomenological Research Topics

Selecting phenomenological research topics involves careful consideration of various factors to ensure the relevance, significance, and feasibility of the study. Here are some criteria to consider when choosing phenomenological research topics:

- Personal Interest: Choose a topic that genuinely interests you, as enthusiasm will fuel your research efforts.

- Relevance: Ensure the topic aligns with your academic or professional goals and contributes to existing knowledge in your field.

- Feasibility: Consider the resources, time, and access needed to conduct research on the chosen topic.

- Clarity: Select a topic with clear boundaries and research questions, facilitating focused investigation.

- Significance: Opt for topics that address meaningful questions or issues, offering potential insights or solutions.

- Accessibility: Ensure the availability of relevant literature, data, and resources to support your research.

- Ethical Considerations: Reflect on the ethical implications of your research topic and ensure compliance with ethical guidelines and standards.

List of Phenomenological Research Topics & Ideas In Education

Phenomenological research in education focuses on exploring lived experiences, perceptions, and meanings related to various aspects of teaching, learning, and educational contexts. Here is a list of potential phenomenological research topics and ideas in education:

Student Experience

- The Lived Experience of First-Generation College Students

- Understanding Student Motivation in Online Learning Environments

- Perceptions of Academic Stress Among High School Students

- Exploring Student-Teacher Relationships in Early Childhood Education

- The Lived Experience of Bullying Among Middle School Students

- Student Perspectives on the Transition to Remote Learning During COVID-19

- The Meaning of Success for College Students

- Navigating Cultural Identity in Higher Education

- Exploring the Impact of Extracurricular Activities on Student Well-being

- Student Perspectives on Inclusive Education Practices

- The Lived Experience of Homeschooling

- Student Perceptions of STEM Education

- Understanding Student Engagement in Project-Based Learning

- The Meaning of Achievement for High-Achieving Students

- Exploring Student Resilience in the Face of Academic Challenges

- The Lived Experience of Special Education Students

Teacher Experience

- The Lived Experience of New Teachers in Urban Schools

- Teacher Perspectives on the Integration of Technology in the Classroom

- Exploring Teacher Burnout and Stress in Secondary Education

- The Meaning of Teaching Excellence

- Teacher Experiences with Classroom Management Strategies

- The Lived Experience of Teaching Students with Disabilities

- Teacher Perceptions of Professional Development Programs

- Understanding Teacher Identity and Role Perception

- Exploring Teacher Collaboration in Professional Learning Communities

- Teacher Perspectives on Inclusive Classroom Practices

- The Lived Experience of Teaching in Multicultural Classrooms

- Teacher Attitudes Towards Standardized Testing

- Exploring Teacher Well-being and Self-care Practices

- The Meaning of Teacher Leadership

- Teacher Perspectives on Parental Involvement in Education

- The Lived Experience of Teaching in Rural Schools

Parental Involvement

- Parent Perspectives on Early Childhood Education Programs

- The Lived Experience of Parenting a Child with Special Needs

- Understanding Parental Involvement in Homework Practices

- Exploring Parent-Teacher Communication in Elementary Schools

- Parent Perspectives on School Choice and Education Policy

- The Meaning of Parental Engagement in Education

- Parent Experiences with Homeschooling

- Understanding Parental Expectations and Aspirations for Their Children

- Exploring Parental Involvement in Extracurricular Activities

- Parent Perspectives on Inclusive Education for Children with Disabilities

- The Lived Experience of Being a Single Parent in Education

- Parental Perceptions of Social and Emotional Learning Programs

- Exploring Parental Involvement in Early Literacy Development

- The Meaning of Parent-Teacher Partnerships

- Parent Experiences with Remote Learning During the Pandemic

- Understanding Parental Involvement in College Preparation

School Climate and Culture

- Student Perspectives on School Safety Measures

- The Lived Experience of School Bullying Prevention Programs

- Teacher Perceptions of School Leadership and Administration

- Exploring School Climate and Its Impact on Student Well-being

- Parent Perspectives on School Culture and Diversity

- The Meaning of Equity and Inclusion in School Environments

- Student Experiences with Restorative Justice Practices in Schools

- Understanding the Role of School Climate in Academic Achievement

- Exploring Cultural Competency in School Settings

- Teacher Perspectives on Building Positive Classroom Culture

- The Lived Experience of Student Discipline Policies

- Parental Involvement in School Decision-Making Processes

- Exploring Teacher-Student Relationships and Trust in Schools

- The Meaning of Respect and Belonging in School Communities

- Student Perspectives on Peer Relationships and Social Dynamics

- Teacher Experiences with Classroom Diversity and Inclusion Initiatives

Curriculum and Instruction

- Student Perspectives on Project-Based Learning Experiences

- The Lived Experience of STEM Education Programs

- Teacher Perspectives on Culturally Responsive Teaching Practices

- Exploring Student Engagement in Differentiated Instruction

- Parent Perspectives on Homeschool Curriculum Choices

- The Meaning of Authentic Assessment in Education

- Student Experiences with Inquiry-Based Learning Approaches

- Understanding Teacher Decision-Making in Curriculum Design

- Exploring Student Voice and Choice in Learning

- Teacher Experiences with Integrating Social and Emotional Learning

- The Lived Experience of Outdoor and Experiential Education

- Parent Perspectives on Early Literacy Curriculum

- Exploring the Role of Arts Education in Student Development

- The Meaning of Global Citizenship Education

- Student Perspectives on Online Learning Platforms

- Teacher Experiences with Flipped Classroom Models

Educational Policy and Reform

- Student Perspectives on Standardized Testing Practices

- The Lived Experience of Education Policy Implementation

- Teacher Perceptions of Educational Equity Initiatives

- Exploring the Impact of School Funding Policies on Student Achievement

- Parent Perspectives on School Choice Options and Charter Schools

- The Meaning of Educational Justice in Policy Discourse

- Student Experiences with No Child Left Behind and Every Student Succeeds Acts

- Understanding Teacher Resistance to Education Reform Efforts

- Exploring the Role of Advocacy Groups in Shaping Education Policy

- Teacher Perspectives on Teacher Evaluation Systems

- The Lived Experience of High-Stakes Testing Pressure

- Parental Involvement in Education Policy Advocacy

- Exploring the Impact of Immigration Policies on Education Access

- The Meaning of Educational Accountability in Policy Implementation

- Student Perspectives on School Discipline Policies and Zero Tolerance

- Teacher Experiences with Education Policy Changes During the Pandemic

Technology in Education

- Student Perspectives on Digital Learning Platforms

- The Lived Experience of Online Education Programs

- Teacher Perceptions of Educational Technology Integration

- Exploring Student Engagement in Virtual Classroom Environments

- Parent Perspectives on Screen Time and Technology Use in Education

- The Meaning of Digital Literacy in the 21st Century Classroom

- Student Experiences with Blended Learning Models

- Understanding Teacher Professional Development in Educational Technology

- Exploring the Role of Artificial Intelligence in Personalized Learning

- Teacher Experiences with Overcoming Technological Barriers in Education

- The Lived Experience of Cyberbullying and Online Safety Measures

- Parent Perspectives on Distance Learning During the Pandemic

- Exploring Student Creativity and Innovation in Technology-Enhanced Learning

- The Meaning of Educational Access and Equity in Digital Spaces

- Student Perspectives on Social Media Use and Its Impact on Education

- Teacher Experiences with Virtual Reality and Augmented Reality Applications in Education

Special Education and Inclusive Practices

- Student Perspectives on Inclusive Education Programs

- The Lived Experience of Students with Learning Disabilities in Mainstream Classrooms

- Teacher Perceptions of Individualized Education Plans (IEPs)

- Exploring Parental Involvement in Special Education Decision-Making

- The Meaning of Inclusion and Belonging for Students with Disabilities

- Student Experiences with Assistive Technology in Education

- Understanding Teacher Attitudes Towards Inclusive Classroom Practices

- Exploring the Role of Paraprofessionals in Supporting Students with Special Needs

- Teacher Experiences with Differentiated Instruction for Diverse Learners

- The Lived Experience of Transition Planning for Students with Disabilities

- Parent Perspectives on Advocating for Special Education Services

- Exploring Student Self-Advocacy Skills in Special Education Settings

- The Meaning of Success and Achievement for Students with Disabilities

- Student Perspectives on Peer Relationships in Inclusive Classrooms

- Teacher Experiences with Universal Design for Learning (UDL)

- Understanding the Impact of Stigma and Stereotypes on Students with Disabilities

Higher Education and Career Development

- Student Perspectives on College Readiness and Preparation

- Teacher Perceptions of College and Career Readiness Programs

- Exploring Parental Expectations for Higher Education

- The Meaning of Success in Higher Education

- Student Experiences with Internship and Work-Study Programs

- Understanding Teacher-Student Relationships in College Settings

- Exploring the Role of Mentoring in College and Career Success

- Teacher Experiences with Advising and Counseling College-Bound Students

- The Lived Experience of Non-Traditional Students in Higher Education

- Parent Perspectives on College Affordability and Financial Aid

- Exploring Student Decision-Making in Choosing a College Major

- The Meaning of Employability and Career Preparedness

- Student Perspectives on Work-Life Balance During College

- Teacher Experiences with Supporting Students’ Transition to the Workforce

- Understanding the Impact of College Experiences on Long-Term Career Trajectories

Global Perspectives in Education

- Student Perspectives on International Education Programs and Exchanges

- The Lived Experience of Cultural Adjustment for International Students

- Teacher Perceptions of Global Citizenship Education

- Exploring Parental Attitudes Towards Global Learning Initiatives

- The Meaning of Diversity and Inclusion in Global Education

- Student Experiences with Service-Learning and Volunteer Abroad Programs

- Understanding Teacher-Student Cross-Cultural Communication Challenges

- Exploring the Role of Technology in Connecting Global Classrooms

- Teacher Experiences with Incorporating Global Issues into Curriculum

- The Lived Experience of Language Learning and Multilingualism

- Parent Perspectives on the Value of Global Education for Their Children

- Exploring Student Perspectives on Cultural Identity and Belonging

- The Meaning of Intercultural Competence in Education

- Student Perspectives on Global Environmental Education and Sustainability

- Teacher Experiences with Leading Global Education Initiatives

- Understanding the Impact of Globalization on Education Systems and Practices

These topics offer avenues for exploring the subjective experiences, perceptions, and meanings embedded within educational contexts, shedding light on diverse aspects of teaching, learning, and the educational experience.

Importance of Phenomenological Research Topics

Phenomenological research topics hold significant importance for several reasons:

Deep Understanding

Phenomenological research topics allow researchers to delve into the depth of human experiences, providing insights into the subjective aspects of reality.

Personal Connection

These topics resonate with individuals personally, fostering empathy and understanding of diverse perspectives.

Practical Application

Findings from phenomenological research can inform educational practices, policy-making, and interventions aimed at improving student outcomes and enhancing the educational experience.

Meaningful Exploration

Phenomenological research topics offer opportunities for meaningful exploration of complex phenomena, contributing to advancing knowledge in education and related fields.

Tips for Conducting Phenomenological Research Topics

Conducting phenomenological research requires careful attention to methodological principles and approaches that facilitate the exploration of lived experiences and subjective meanings. Here are some tips for conducting phenomenological research:

- Immersion: Immerse yourself fully in the phenomenon under study, experiencing it firsthand to gain deeper insight.

- Bracketing: Set aside preconceived notions and biases to approach the research with an open mind.

- Reflexivity: Reflect on your own experiences and how they may influence your interpretation of the data.

- Participant Selection: Choose participants who have experienced the phenomenon in question and can provide rich, detailed accounts.

- Data Collection: Utilize methods such as interviews, observations, and journaling to gather in-depth data.

- Thematic Analysis: Identify common themes and patterns in the data to uncover the essence of the phenomenon.

- Member Checking: Validate findings with participants to ensure accuracy and authenticity.

- Ethical Considerations: Respect participants’ privacy, autonomy, and confidentiality throughout the research process.

Final Thoughts

The selection of appropriate phenomenological research topics is crucial for delving into the richness of human experience and uncovering subjective meanings.

It empowers students to explore the complexities of lived experiences, fostering empathy, understanding, and meaningful insights.

By embracing phenomenology, researchers can advance knowledge and understanding across diverse fields, shedding light on the intricacies of the human condition.

As students embark on their research endeavors, may they be inspired to engage deeply with the phenomenological approach, recognizing its profound potential to contribute to scholarship, practice, and the pursuit of truth.

1. What are some common challenges in conducting phenomenological research?

Challenges may include ensuring participant confidentiality and privacy, managing researcher bias, and interpreting subjective experiences. Additionally, researchers may encounter difficulties in selecting appropriate data collection methods and analyzing rich qualitative data.

2. Can phenomenological research be applied across different disciplines?

Yes, phenomenological research can be applied in various fields, including psychology, sociology, education, healthcare, and more. The subjective nature of phenomenological inquiry allows researchers to explore diverse phenomena and perspectives, making it adaptable to different disciplines.

3. What are some examples of phenomenological research topics in education?

Examples include exploring student experiences in online learning environments, understanding teacher perspectives on inclusive education practices, and investigating parental involvement in early childhood education programs.

Related Posts

Science Fair Project Ideas For 6th Graders

When it comes to Science Fair Project Ideas For 6th Graders, the possibilities are endless! These projects not only help students develop essential skills, such…

Java Project Ideas for Beginners

Java is one of the most popular programming languages. It is used for many applications, from laptops to data centers, gaming consoles, scientific supercomputers, and…

171 Best Phenomenological Research Topics For Students

Welcome to our exploration of Phenomenological Research Topics, where we examine how people experience life. Phenomenology, a philosophy turned research method, tries to understand how we experience the world around us.

By studying people’s experiences, this blog will uncover the depths of emotions, perceptions, social interactions, memories, and identity. We want to illuminate the complex woven cloth of human existence and our realities by examining these topics.

Whether you’re a student, researcher, or just curious about how complicated human experiences are, join us as we explore the rich research landscape of people’s experiences. Let’s start this journey together to understand better what it means to be human.

What Is Phenomenological Research?

Table of Contents

Phenomenological research is a type of study that tries to understand people’s personal experiences and how they make sense of the world. Researchers ask participants questions about their lives, feelings, perceptions, and understandings.

The goal is to uncover the deep meaning behind everyday experiences we may take for granted. Phenomenological studies value the subjective perspectives of individuals and aim to see the world through their eyes. These studies often rely on in-depth interviews, observations, art, diaries, and other personal sources of information.

The focus is on describing the essence of an experience rather than explaining or analyzing it. The aim is to gain insight into the diversity and complexity of human experience in a way that is accessible and relatable. Phenomenological research provides an enriching window into what it means to be human.

171 Phenomenological Research Topics

Here is the list of phenomenological research topics:

- The experience of being a first-generation college student.

- The lived experiences of pupils with disabilities in higher education.

- Teachers’ experiences of burnout in urban schools.

- Parental involvement in early childhood education: A phenomenological study.

- The lived experiences of immigrant students in the classroom.

- Homeschooling: A phenomenological exploration of parental motivations.

- Student perceptions of online education during the COVID-19 pandemic.

- The experiences of teachers implementing project-based learning in STEM education.

- Peer tutoring: A phenomenological investigation into its effectiveness.

- Educational leadership: A phenomenological study of principals’ experiences.

Psychology and Mental Health

- The lived experiences of individuals with anxiety disorders.

- Perceptions of body image among adolescents: A phenomenological inquiry.

- Faring mechanisms of parents of children with autism spectrum disorder.

- Experiences of postpartum depression among new mothers.

- The phenomenology of addiction recovery.

- The lived adventures of survivors of domestic violence.

- Self-care practices among mental health professionals.

- The meaning of resilience: A phenomenological exploration.

- Experiences of grief and loss: A phenomenological study.

- Psychological well-being in the LGBTQ+ community: A phenomenological approach.

Health and Medicine

- The lived experiences of cancer survivors.

- The patient experiences chronic pain management.

- Understanding the meaning of disability: A phenomenological study.

- Nurses’ experiences of compassion fatigue.

- The lived experiences of people living with HIV/AIDS.

- Family caregivers’ experiences of caring for elderly relatives.

- Medical professionals’ experiences of ethical dilemmas in healthcare.

- The phenomenology of end-of-life care.

- Experiences of stigma among some people with mental illness.

- The lived experiences of organ transplant recipients.

Sociology and Anthropology

- The experience of homelessness: A phenomenological exploration.

- Perceptions of social justice among marginalized communities.

- Cultural identity among immigrant populations: A phenomenological study.

- Experiences of discrimination based on race/ethnicity.

- The meaning of community in rural areas: A phenomenological inquiry.

- The lived experiences of refugees resettling in a new country.

- Social media use and its impact on interpersonal relationships.

- Experiences of aging: A phenomenological perspective.

- Work-life balance: A phenomenological study of dual-career couples.

- The phenomenology of poverty in urban settings.

Business and Management

- Entrepreneurial experiences of women in male-dominated industries.

- Leadership styles in multinational corporations: A phenomenological approach.

- Work-life integration among Millennials in the workforce.

- Employee experiences of workplace diversity and inclusion initiatives.

- Small business owners’ experiences of navigating economic challenges.

- The lived experiences of remote workers.

- Burnout among healthcare professionals: A phenomenological study.

- The meaning of success in the business world: A phenomenological inquiry.

- Experiences of workplace harassment and discrimination.

- The effect of organizational culture on worker satisfaction: A phenomenological exploration.

Technology and Society

- The lived experiences of individuals with technology addiction.

- Online gaming communities: A phenomenological investigation.

- Experiences of cyberbullying among adolescents.

- Social media and self-esteem: A phenomenological perspective.

- The impact of (AI) artificial intelligence on everyday life: A phenomenological study.

- Digital nomadism: A phenomenological exploration of remote work lifestyles.

- Virtual reality experiences: A phenomenological inquiry.

- Ethical considerations in the use of big data: A phenomenological study.

- The lived experiences of individuals disconnecting from technology.

- The phenomenology of online activism and social movements.

Arts and Humanities

- The lived experiences of professional artists.

- Experiences of creativity and inspiration among writers.

- Art therapy: A phenomenological exploration of its effects.

- The meaning of beauty: A phenomenological inquiry.

- Experiences of cultural heritage preservation.

- Music therapy: A phenomenological study of its impact on mental health.

- The lived experiences of actors in the theater industry.

- The role of storytelling in shaping identity: A phenomenological perspective.

- Experiences of cultural assimilation through literature.

- The phenomenology of dance as a form of expression.

Environmental Studies

- The lived experiences of individuals affected by climate change.

- Sustainable living practices: A phenomenological exploration.

- Environmental activism: A phenomenological study of motivations.

- Experiences of reconnecting with nature in urban environments.

- The meaning of environmental stewardship: A phenomenological inquiry.

- Perceptions of ecological justice in marginalized communities.

- The lived experiences of indigenous people’s relationship with the land.

- Ecopsychology: A phenomenological perspective.

- Experiences of volunteering for environmental conservation efforts.

- The phenomenology of outdoor recreational activities.

Philosophy and Ethics

- The meaning of happiness: A phenomenological exploration.

- Experiences of moral dilemmas in everyday life.

- Personal identity: A phenomenological study of self-perception.

- The phenomenology of forgiveness and reconciliation.

- The lived experiences of individuals practicing mindfulness.

- Ethical decision-making in professional contexts: A phenomenological inquiry.

- Experiences of existential anxiety and meaninglessness.

- The phenomenology of altruism and empathy.

- Spirituality and well-being: A phenomenological perspective.

- The meaning of life: A phenomenological inquiry into existential questions.

Politics and Governance

- Political engagement among young adults: A phenomenological study.

- Experiences of activism and social change.

- The lived experiences of refugees navigating asylum processes.

- Experiences of political polarization in society.

- Grassroots movements: A phenomenological exploration.

- The meaning of democracy: A phenomenological perspective.

- Experiences of political participation among marginalized groups.

- The role of identity in political discourse: A phenomenological inquiry.

- Experiences of civic engagement in local communities.

- The phenomenology of political leadership.

Family and Relationships

- The lived experiences of blended families.

- Experiences of parenthood: A phenomenological exploration.

- Sibling relationships: A phenomenological study.

- The meaning of love in romantic relationships: A phenomenological inquiry.

- Experiences of caregiving for elderly family members.

- Intergenerational relationships: A phenomenological perspective.

- The lived experiences of individuals in long-distance relationships.

- Experiences of infertility and assisted reproductive technologies.

- Divorce and its impact on family dynamics: A phenomenological study.

- The phenomenology of friendship and social support.

Religion and Spirituality

- Religious conversion experiences: A phenomenological exploration.

- The lived experiences of individuals in religious communities.

- Experiences of spiritual awakening and transformation.

- Religious rituals and their significance: A phenomenological study.

- The meaning of faith: A phenomenological inquiry.

- Religious identity and its role in personal development.

- Experiences of religious discrimination and persecution.

- The phenomenology of religious pilgrimage.

- Spirituality and coping with illness: A phenomenological perspective.

- Mystical experiences: A phenomenological exploration.

Miscellaneous

- Experiences of travel and cultural immersion.

- The meaning of home: A phenomenological study.

- Experiences of coming out: A phenomenological exploration.

- The lived experiences of people in recovery from substance abuse.

- Volunteerism and its impact on personal development: A phenomenological perspective.

- The meaning of leisure: A phenomenological inquiry.

- Experiences of intercultural communication and adaptation.

- The phenomenology of dreams and their interpretation.

- Experiences of living with chronic illness.

- The meaning of success: A phenomenological exploration of personal goals.

Sports and Recreation

- The lived experiences of professional athletes.

- Experiences of team dynamics in sports.

- The meaning of competition: A phenomenological inquiry.

- Experiences of injury and rehabilitation in sports.

- Sports fandom: A phenomenological exploration.

- The lived experiences of coaches in youth sports.

- Experiences of gender identity in sports.

- The phenomenology of extreme sports.

- Sportsmanship and ethics: A phenomenological study.

- The meaning of achievement in sports: A phenomenological perspective.

Technology and Innovation

- Experiences of early adopters of new technologies.

- The lived experiences of individuals with wearable technology.

- Technological disruptions in the workplace: A phenomenological exploration.

- Experiences of artificial intelligence and automation in daily life.

- Virtual reality gaming: A phenomenological study of immersion.

- The impact of social media influencers: A phenomenological perspective.

- Experiences of privacy and surveillance in the digital age.

- The meaning of digital literacy: A phenomenological inquiry.

- Experiences of technology-mediated communication.

- The phenomenology of online shopping experiences.

Media and Communication

- The lived experiences of journalists covering conflict zones.

- Experiences of social media activism and advocacy.

- Media representation and identity: A phenomenological exploration.

- Experiences of misinformation and fake news consumption.

- The meaning of celebrity culture: A phenomenological study.

- Experiences of binge-watching television series.

- The phenomenology of advertising and consumer behavior.

- Experiences of online dating and virtual relationships.

- The lived experiences of content creators on digital platforms.

- Experiences of censorship and freedom of speech in media.

Law and Justice

- Experiences of wrongful conviction: A phenomenological inquiry.

- The lived experiences of people involved in restorative justice processes.

- Experiences of bias in the criminal justice system.

- The meaning of justice: A phenomenological exploration.

- Experiences of being a juror in a criminal trial.

- Police-community relations: A phenomenological study.

- The lived experiences of victims of crime.

- Experiences of incarceration and reintegration into society.

- Legal professionals’ experiences of ethical dilemmas.

- The meaning of punishment: A phenomenological inquiry into justice systems.

- Experiences of seeking legal recourse: A phenomenological exploration.

These phenomenological research topics cover various disciplines and provide ample opportunities for phenomenological research. Researchers can explore lived experiences, perceptions, and meanings associated with various phenomena within each field.

Applications of Phenomenological Research

Here are some ways phenomenological research can be helpful for students:

- Understanding learning experiences – Students can be interviewed about their subjective experiences in the classroom, with homework, studying for exams, etc. This provides insight into how to improve education.

- Exploring social experiences – Students’ experiences making friends, joining groups, dealing with peer pressure, and more can be examined. This sheds light on social development.

- Investigating identity formation – The essence of forming one’s identity and sense of self during college can be uncovered through phenomenological methods.

- Discovering motivations – Students’ motivations for pursuing higher education, choosing a major, and setting career goals can be explored in-depth.

- Gaining perspectives on diversity – Students from diverse backgrounds can share their experiences on campus related to culture, race, gender, sexuality, disability, etc.

- Understanding extracurriculars – The meaning students ascribe to activities like sports, clubs, volunteer work, and internships and how these shape their collegiate journey.

- Transition challenges – Phenomenological studies can provide insight into the lived experiences of crucial transitions like moving away from home, transferring schools, graduating, etc.

- Wellness/health – Students’ experiences with stress, anxiety, depression, sleep issues, burnout, and other health concerns can be examined to promote well-being.

The takeaway is that phenomenological research can give rich insights into the student’s perspective and subjective realities. This is invaluable for improving educational experiences.

Challenges and Criticisms in Phenomenological Research

Here are some common challenges and criticisms associated with phenomenological research:

- Subjectivity – Critics argue phenomenology is too subjective and lacks scientific rigor. The subjective nature makes it challenging to generalize findings.

- Researcher bias – The researcher’s personal views and expectations may bias the collection and interpretation of data. Bracketing to set aside presuppositions is difficult.

- Retrospective bias – Participants may not accurately recall past experiences, distorting the lived essence under examination.

- Ambiguous approach – There is no single phenomenological method, which makes the overall approach vague. Steps in data analysis can be unclear.

- Abstract concepts – Descriptions of essences, meanings, and perceptions can be abstract. Communicating findings is challenging.

- Data collection limits – Depth interviews or observations may not capture the lived experience. Relying only on language is restricting.

- Generalizability – Small sample sizes in phenomenology make extending findings to larger populations difficult.

- Lack of causality – Phenomenology aims for descriptive insight rather than explanatory models or causal relationships.

- Time-consuming – Conducting in-depth interviews and analyzing large amounts of qualitative data is very time-intensive.

While valuable, phenomenology has limitations. Researchers should acknowledge subjectivities, triangulate data carefully, and communicate detailed descriptions of the phenomenon under study.

Future Directions in Phenomenological Research

Here are some potential future directions for phenomenological research:

- Increased diversity – Studies that aim to understand a broader range of cultural, social, and individual experiences. Giving voice to marginalized groups.

- New contexts – Applying phenomenological methods to emerging topics like technology, social media, climate change , pandemics, etc.

- Multimodal data – Incorporating data beyond interviews, like art, videography, observation, and participant diaries.

- Longitudinal insights – Following individuals’ lived experiences over extended periods as phenomena evolve.

- Collaborative approaches – Having participants be actively involved as co-researchers in designing studies and analyzing/communicating shared experiences.

- Innovative analysis – Leveraging advancements in qualitative data analysis software to uncover subtleties and connections in phenomenological data.

- Integration – Combining phenomenological findings with methods like grounded theory, ethnography, and experimental research for richer insights.

- Enhanced rigor – Improving methodological rigor while retaining open phenomenological inquiry using techniques like member checking.

- Applied research – Partnering with communities, organizations, and policymakers to ensure phenomenological insights translate to impact in real-world contexts.

- Cross-disciplinary – Scholars from diverse fields like health, psychology, and business collaborating on phenomenological projects using mixed expertise.

- New publishing models – Opting for open-access and multimedia publication to enhance dissemination and accessibility of phenomenological research.

The future looks bright for phenomenology’s continued elucidation of human experience!

Final Remarks

In conclusion, our journey through Phenomenological Research Topics has given us valuable insights into the complexities of human life. From exploring emotions and perceptions to understanding social interactions, memories, and identity, we have uncovered the rich woven cloth of personal realities that shape our lives.

Studying people’s experiences offers a unique lens through which we can delve into the essence of being human, acknowledging the importance of individual perspectives and real-life experiences. As we conclude our exploration, it’s clear that research about people’s experiences holds huge potential for further inquiry and understanding in various fields.

By embracing the nuanced nature of human existence, we can continue to heighten our knowledge of ourselves and the world around us. Let’s keep exploring and appreciating the depth of human experience by studying people’s experiences. I hope you liked this post about Phenomenological Research Topics.

Similar Articles

Top 100 Research Topics In Commerce Field

The world of commerce is rapidly evolving. With new technologies, globalization, and changing consumer behaviors, many exciting research topics exist…

Top 30+ Mini Project Ideas For Computer Engineering Students

Mini projects are really important for computer engineering students. They help students learn by doing practical stuff alongside their regular…

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

In order to continue enjoying our site, we ask that you confirm your identity as a human. Thank you very much for your cooperation.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Int J Environ Res Public Health

A Phenomenological Study of Nurses’ Experience in Caring for COVID-19 Patients

Hye-young jang.

1 School of Nursing, Research Institute of Nursing Science, Hanyang University, Seoul 04763, Korea; rk.ca.gnaynah@8010etihw

Jeong-Eun Yang

2 Department of Nursing, Jesus University, Jeonju-si 54989, Korea; rk.ca.susej@gnayfle

Yong-Soon Shin

Associated data.

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

This study aimed to understand and describe the experiences of nurses who cared for patients with COVID-19. A descriptive phenomenological approach was used to collect data from individual in-depth interviews with 14 nurses, from 20 October 2020 to 15 January 2021. Data were analyzed using the phenomenological method of Colaizzi. Five theme clusters emerged from the analysis: (1) nurses struggling under the weight of dealing with infectious disease, (2) challenges added to difficult caring, (3) double suffering from patient care, (4) support for caring, and (5) expectations for post-COVID-19 life. The findings of this study are useful primary data for developing appropriate measures for health professionals’ wellbeing during outbreaks of infectious diseases. Specifically, as nurses in this study struggled with mental as well as physical difficulties, it is suggested that future studies develop and apply mental health recovery programs for them. To be prepared for future infectious diseases and contribute to patient care, policymakers should improve the work environment, through various means, such as nurses’ practice environment management and incentives.

1. Introduction

As the novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) spreads worldwide and becomes more serious, the World Health Organization (WHO) has declared it a global epidemic. In Korea, the first case of COVID-19 was confirmed on 20 January 2020; as of 29 June 2021, the total number of patients was 156,167, of which 6882 were quarantined and treated, with a fatality rate of 1.29% [ 1 ].

COVID-19 is caused by a novel coronavirus—severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2)—and manifests in clinical symptoms, such as cough (74.9%), fever (68.0%) and dyspnea (60.9%) among hospitalized patients [ 2 ]. In the case of SARS-CoV-2, it has been reported that if patients are isolated within 5 days of the onset of clinical symptoms, secondary infections occur less frequently; transmission can be effectively blocked by isolating immediately after the onset of symptoms [ 3 ]. However, hospitalizations in negative pressure isolation rooms, to block airborne infections, create a more isolated environment than the general intensive care unit environment; mandate medical personnel to wear unfamiliar and uncomfortable protective equipment; prohibit family visits and outside contact. Isolation affects patients as well, as it has been reported that many patients were insufficiently informed about the isolation environment and period, and this uncertainty caused them to experience depression [ 4 ]. These circumstances increase the importance of caring for patients in isolation.

Caring is an important concept within the field of nursing, as it affects the health of the patient as a whole [ 5 ]. In particular, in the early stages of outbreaks of new infectious diseases, all aspects, such as the pathology, transmission route, and effective treatment of the disease are uncertain [ 6 ]. Even the effectiveness of protective equipment is uncertain. It has been found that healthcare providers’ anxiety and fear in such conditions affects their ability to care for patients [ 7 , 8 ]. In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, many scholars predict that the time before and after the pandemic will be very different and are asking if we are ready for post- or the ‘with COVID-19 era’ [ 9 , 10 , 11 ]. Even in nursing, this change is difficult to ignore, and nursing professionals and researchers should answer whether we are preparing the ‘with COVID-19 era’. In order to identify the reality of nursing in the ‘with COVID-19 era’, it is necessary to understand what nursing and caring experiences were like for nurses who have been care professionals during the unprecedented COVID-19 pandemic. During the pandemic, nurses played a positive role in the rapid reorganization of the nursing system, improvement of team communication, coordination materials for emergency and continuous care, improvement of efficiency of nursing performance as a front-line caregiver, and caring for other nurses [ 12 ]. However, nurses are starting to experience burnout, having been unaware that the pandemic would soon change health professions universally [ 13 ]. For this, it is necessary to examine the experiences of nurses who have been, and are, caring for quarantined patients.

Studies on the nursing experience of patients with COVID-19 are underway in countries in various trajectories of the COVID-19 pandemic, such as Spain [ 14 ], Italy [ 15 ], Canada [ 16 ], the United States [ 17 ], and China [ 18 ], and these previous studies are focused on the lived nursing experience itself or the ethical aspect. Experiences of nursing care reported so far are summarized as providing nursing care [ 14 , 15 , 16 ], psychosocial and emotional aspects [ 14 , 15 , 18 , 19 ], resource management [ 14 , 16 ], struggling on the frontline [ 19 , 20 ], personal growth [ 18 , 19 ] and adapting to changes [ 18 , 20 ].

In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Korean government responded using the K-Quarantine, also known as 3T–Test (diagnosis/confirmation), Trace (epidemiological survey/trace) and Treat (isolation/treatment) [ 21 ]. In particular, since February 2020, COVID-19 hospitals have been designated and operated for safe isolation beds for hospitalization of COVID-19 patients [ 22 ]. As patients diagnosed with COVID-19 are transferred to a designated hospital, operating a medical system that receives intensive treatment and care, the nurses at the hospitals are facing a high level of depression, anxiety, and stress [ 23 , 24 ].

However, the nursing experience of Korean nurses is only a small part of the research done in the early stage of the pandemic, and that knowledge is not enough to understand the essence of nursing in the special nursing environment of COVID-19. Therefore, this study was conducted to understand the lived nursing experience of the nurses at COVID-19-designated hospitals during the third wave [ 25 ] of the COVID-19 pandemic in Korea. The nursing experience of Korean COVID-19-dedicated hospital nurses could provide a unique opportunity to develop long-term sustainable response strategies under a long-lasting pandemic.

Phenomenological research focuses on vivid experiences, perceived or interpreted by participants, and aims to view and describe the world of their consciousness as a real world. In addition, exploring the experiences of others can discover insights that were previously unavailable, so it is considered a useful method for the purpose of this study. Particularly, Colaizzi’s [ 26 ] method focuses on deriving a collection of common attributes and themes from multiple responses, rather than individual attributes. This method will facilitate an in-depth understanding of how nurses experienced caregiving for patients with COVID-19, and further contribute to the literature, regarding high-quality nursing care for quarantined patients. Therefore, the purpose of this study is to investigate the meaning and essence of nurses’ experiences of caring for COVID-19 patients, using a phenomenological research method.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. study design.

The philosophical framework and study design of this study were guided by phenomenology. The philosophical aim of phenomenology is to provide an understanding of the participant’s lived experiences [ 27 ]. In order to reveal the true essence of the ‘living experience’, it is first necessary to minimize the preconceived ideas that researchers may have about the research phenomenon (bracketing). Through such a phenomenological attitude, the participant’s experience can be explored as it is [ 28 ]. From a phenomenological point of view, objectivity is obtained by being faithful to the phenomenon, and it can be secured by paying attention to the phenomenon itself rather than explaining what it is. As such, phenomenology seeks to reveal meaning and essences in the participant’s experiences of the participant to facilitate understanding [ 28 ].

This study is an inductive study, applying the phenomenological research method of Colaizzi [ 26 ], in order to gain an in-depth understanding of the essence of nurses’ experience in caring for COVID-19 patients, and it followed the guideline for qualitative research, established by the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research [ 29 ]. The question of this study is, “What is the meaning and essence of the care experience of nurses who directly cared for COVID-19 patients?”

2.2. Participants and Settings

Participants were nurses working at a COVID-19 Infectious Disease Hospital in Seoul and Gyeonggi Province. The COVID-19 Infectious Disease Hospital was established and is operated by the Ministry of Health and Welfare, one of the central government ministries of South Korea, to respond to infectious diseases during the COVID-19 pandemic. It is dedicated to managing infected patients.

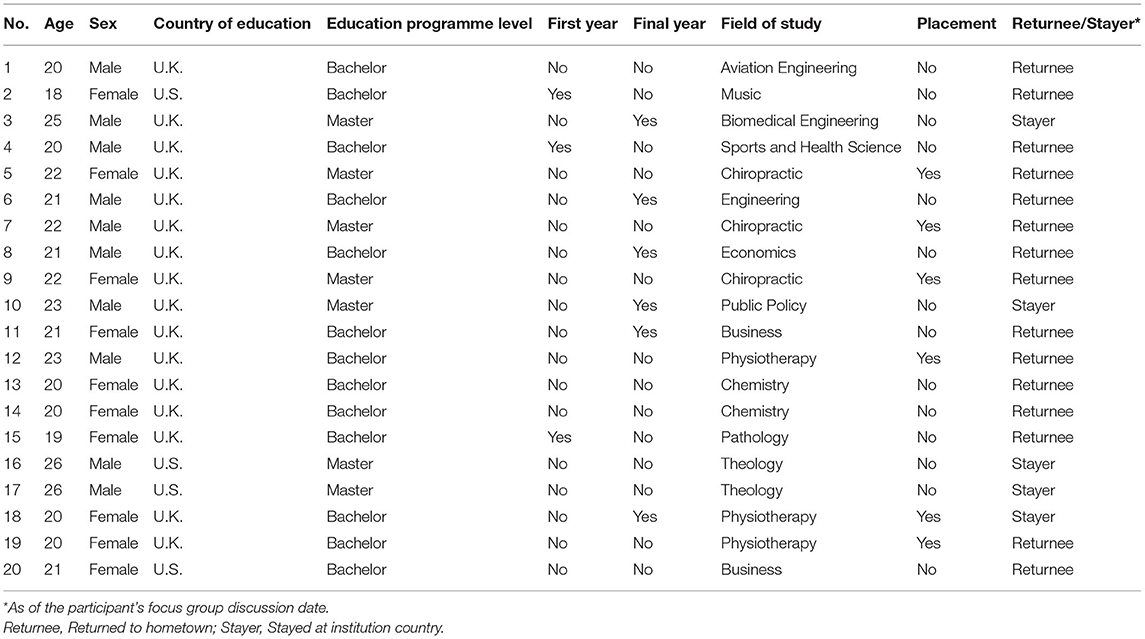

The inclusion criteria were as follows: nurses who had directly cared for confirmed or suspected COVID-19 patients in an isolation ward for at least 1 month; could communicate well and comprehend the purpose of this study; had voluntarily consented to participate. Nurses who had cared for COVID-19 patients for less than 1 month, had not participated in direct care, or had not been released from isolation, were excluded. Fourteen nurses participated in in-depth interviews individually ( Table 1 ).

General Characteristics of Participants ( N = 14).

| Variables | N | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | Male | 2 |

| Female | 12 | |

| Age (years) | <30 | 5 |

| 30–39 | 3 | |

| 40–49 | 6 | |

| Education | College | 11 |

| Graduate School | 3 | |

| Number of patients per nurse | 3 | 1 |

| 4 | 6 | |

| 5 | 4 | |

| 6 | 2 | |

| 7 | - | |

| 8 | - | |

| 9 | 1 | |

| Period of working in isolation ward, (months) | <3 | 1 |

| 3–<6 | 4 | |

| 6–<9 | 5 | |

| 9–<12 | 3 | |

| 12≤ | 1 | |

| Change of place of residence during working in the isolation ward, yes | 4 | |

| Infection control education on COVID-19, yes | 12 | |

Note. COVID-19 = coronavirus disease-2019.

2.3. Data Collection

Data were collected through in-depth interviews from 20 October 2020 to 15 January 2021 using purposive sampling (n = 12) and snowball sampling (n = 2). The sample size was determined by data saturation [ 30 ]. Data saturation was considered achieved when no new themes were revealed in the interviews of participants. Data saturation was determined by two researchers after the fourteenth case interview. Interviews were conducted either online or face-to-face by one well-trained researcher, depending on participants’ convenience. During face-to-face interviews, we created a comfortable atmosphere by beginning with everyday conversations. Interviews began with an open-ended question: “Tell me about your experience of caring for patients with COVID-19”, so that participants could elaborately and spontaneously describe their experiences. The interviews lasted about 60–120 min, and data collection and analysis were conducted simultaneously.

2.4. Data Analysis

The interview content was transcribed verbatim within 24 h of each interview by the researcher. Transcripts of each participant’s interview and the memos were used to analyze data. Two researchers with doctoral degrees independently analyzed and discussed findings.

Data analysis was guided by Colaizzi’s seven-step descriptive phenomenological method [ 26 ]: (1) researchers read all accounts multiple times to understand the overall flow of participants’ experiences in caring for COVID-19 patients; (2) we extracted significant statements from each description, focusing on meaningful statements related to participants’ caring experiences; (3) we formulated meanings from those significant statements, trying to discover the latent meaning in the context; (4) we organized those formulated meanings into themes and theme clusters; (5) the phenomenon under study was exhaustively described by integrating all the research results; (6) we identified the fundamental structure of the phenomenon; (7) finally, we validated this study by receiving feedback from two participants.

In the entire process of data analysis, we tried to keep a distance from the researcher’s thoughts and feelings, and point of view about the phenomenon, as well as the content of the data, while being conscious of Husserl’s ‘bracketing’ [ 28 ]. In this way, we tried to avoid data distortion, reduction, and exaggeration by the researcher, and we tried to confirm and understand the perspective, attitude, and feeling of the participant as much as possible in the participant’s statement.

To ensure trustworthiness of this study, the four criteria established by Lincoln and Guba [ 31 ] were used. For enhancing truth-value, we tried to obtain a rich set of data by selecting participants who would like to express the research phenomenon well and making it as comfortable as possible for the participants to state their experiences. We showed the study results to two participants to verify whether the derived results reflected the participants’ experiences.

To ensure applicability, we provided the general characteristics of participants and tried to provide a thick description of the research phenomenon.

To establish consistency, Colaizzi’s analysis method was adhered to, and the detailed research process and original data for each theme were presented to enhance the reader’s understanding of the research results. The researcher conducted the research while taking a neutral attitude throughout the research process, excluding bias, prejudices, assumptions (bracketing), so that the participant’s experience distortion by the researcher was minimized. In other words, in order to establish neutrality, which means freedom from prejudice about research results, at the beginning of the study, the researcher explicated any assumptions that could influence data collection and analysis [ 32 ] (ex. participants will mostly have negative emotions while caring for patients without any preparation. Participants will be withdrawn from the social perspective because they are taking care of infected patients.) The other researcher reviewed data analysis to ensure that the researcher’s assumptions did not influence data interpretation.

2.6. Ethical Considerations

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the researcher’s affiliated institution (HYUIRB-202009-009). Participants were informed about the purpose of the study, reporting of study results, and interview recordings. We obtained written informed consents from all participants before data collection. In addition, it was explained that even after consenting, participants could withdraw from the study at any time without any harm if they wished. All participants were provided with a small reward as appreciation for their participation in the study.

The essential structure of the phenomenon was identified as ‘Going beyond the double suffering tunnel of taking charge of infected patients into the future’. The essence of the phenomenon is presented as five theme clusters, and twelve themes emerged from analyzing nurses’ experiences with caring for COVID-19 patients: (1) nurses struggling under the weight of dealing with infectious disease, (2) challenges added to difficult caring, (3) double suffering from patient care, (4) support for caring, and (5) expectations for post-COVID-19 life ( Table 2 ).

Theme Clusters and Themes.

| Theme Clusters | Themes |

|---|---|

| 1. Nurses struggling under the weight of dealing with infectious disease | Anxiety and fear accompanying patient care Dignity ignored due to the fear of infectious diseases |

| 2. Challenges added to difficult caring | The burden of triple distress for everyone’s safety; Wearing PPE Work loaded solely on nurses Confusing and uncertain working conditions |

| 3. Double suffering from patient care | Self-isolation: anxiety becomes a reality A contrasting perception of nurses: heroes of society versus subjects of avoidance |

| 4. Support for caring | Companionship and sharing difficulties Support and appreciation from patients and people A sense of satisfaction and self-esteem |

| 5. Expectations for post-COVID-19 life | Restoring everyday life Preparing for the future |

3.1. Nurses Struggling under the Weight of Dealing with Infectious Disease

Participants felt fear and anxiety while caring for COVID-19 patients, as they have remained unaware of any definitive treatments. Consumed by thoughts of contracting the disease, they reported feeling unable to remain calm and dutifully serve their patients. In particular, it was shocking, as well as saddening, for them to be unable to provide respectful end of life care toward patients who could not recover.

3.1.1. Anxiety and Fear Accompanying Patient Care

The anxiety and fear at the heart of the thought that they could also be infected became an invisible chain, binding the participants. According to them, nursing without being guaranteed safety was challenging. When facing the reality of nursing while fearing patients’ diseases, it felt unfamiliar for participants to worry about their own and their patients’ safety simultaneously, rather than completely immersing themselves in patients’ recovery. They were uncertain of whether their feelings were normal; although they tried their best to provide quality care, they found it challenging to do so while dealing with their persistent anxiety.

To be honest, that was the hardest for me. Since we were constantly exposed to the risk of infection, it was hard to care for patients due to anxiety rather than due to physical challenges while caring for the patient. (Participant J)

3.1.2. Dignity Ignored Due to the Fear of Infectious Diseases

Having to watch patients struggling alone and in isolation, without the support and comfort of their family members during their final moments, made participants feel extremely sorry and heartbroken. The most distressing aspect of caring for patients on their deathbed was that patients and nurses were faced with the reality that patients’ families would not be allowed to be with them during their moment of dying; the fact that they would pass away without receiving appropriate treatment was secondary. “Patients who died during the COVID-19 period were the most pitiful” does not just indicate the limitations of medical treatment. It highlights dignity, which is be protected even in the worst circumstances, but was disregarded due to the fear of contracting infectious diseases. Participants experienced unimaginable shock and ethical anguish as they witnessed patients being taken to crematoriums without being seen by their family members, with their bodies in bags without having their clothing changed. As these uncontrollable experiences kept repeating, participants made a paradoxical resolve to prevent patients from dying.

Patients who die while I work in the ward usually have their families come to see them and hold their hands. However, for those who die of COVID-19, families come and check their patients on the monitor. I think that’s the most heartbreaking and sad thing. (Participant L)

The post-death process was really shocking. I feel like it didn’t treat people like human beings. Thus, that hurt me the most. I think that’s hard while working in the ward. When patients die, I know how they will be treated. I am so sorry, and my heart hurts. That’s why I really want to discharge them. Seriously, I think I’m getting desperate for this kind of feeling. (Participant B)

3.2. Challenges Added to Difficult Caring

Participants struggled every day, and factors that made their lives more challenging are as follows: the personal protective equipment (PPE) that had to be worn for patient care, working in chaotic conditions without clear instructions, and being overburdened with tasks.

3.2.1. The Burden of Triple Distress for Everyone’s Safety; Wearing PPE

Participants had to endure a significant amount of pain and discomfort for safety purposes, especially while nursing patients in PPE. Less than 10 min after wearing them, the inside of the protective clothing would become warm and fill with sweat, and the eye goggles would become foggy. In these situations, participants experienced difficulties in certain activities, such as communicating with patients, securing intravenous (IV) lines, or drawing blood. Occasionally, they had to wear gloves that did not fit well due to a lack of proper supplies, making their practice more difficult.

I think the hardest thing was to wear Level D and go inside. At first, I did the intubation wearing protective clothing. At that time, my body became sluggish, and my vision became narrower because I was wearing goggles. So, even if I moved a little, it got too hot and I would sweat too much, and it was really hard to deal with something in there. Because it was too hot. (Participant D)

3.2.2. Work Loaded Solely on Nurses

To prevent the spread of COVID-19, hospitals implemented policies to minimize the number of family members and caregivers in contact with patients, which increased the burden of caregiving on participants. Blood collections and portable X-ray imaging that radiological technologists performed also became nurses’ duties. In addition, nurses had to prepare documents for the hospital transfers of patients, and were also responsible for checking, storing, and delivering parcels to patients. Nurses were gradually exhausted as most duties, especially those outside their purview, were delegated to them.

To be honest, there are not just nurses in the hospital. However, it’s a situation where we have to take on everything that other employees have done. I feel like they’re giving all their work to the nurses. We have to prepare everything that the radiology department had to do on their own before. For the meal distribution for COVID-19 patients, nurses have to do everything that the nutrition team previously did. For blood collection, we have to do all the things that the laboratory medicine department used to do. It’s overwhelming that nurses have to do most of the work. (Participant F)

3.2.3. Confusing and Uncertain Working Conditions

Participants’ routine caring for COVID-19 patients has been as uncertain as COVID-19 patients’ conditions. Due to the number of confirmed cases increasing daily and sudden confirmations of the infection in colleagues, situations such as the operation of additional negative pressure wards or temporary closures of wards occurred unexpectedly. Consequently, participants were frequently relocated, and their work schedules and wards were changed, creating confusion. In particular, unclear guidelines and insufficient training made their jobs more difficult.

It’s tough to get the work schedule on a weekly basis. Actually, I don’t know my work schedule for Tuesday even on Monday, so I don’t know which shift I will work on the next day. Hence, it’s really very stressful. (Participant E)

3.3. Double Suffering from Patient Care

Participants experienced not only physical difficulties but also mental and social challenges while caring for COVID-19 patients. They endured self-isolation along with their families, and were uncomfortable with causing their family members to experience isolation. In addition, unlike the usual positive public perception of nurses, participants felt a social disconnection from the negativity and stigma surrounding them, which was also hurtful and uncomfortable.

3.3.1. Self-Isolation: Anxiety Becomes a Reality

Participants contracted the virus while caring for patients or had to enter complete self-isolation due to coming in contact with infected colleagues. They endured the anxiety and fear of being infected and suddenly became subjects of self-isolation, leading to concerns about having their personal information exposed, and the social stigma of being confirmed COVID-19 patients. Those who tested negative felt “uncomfortable relief”, even as their colleagues were testing positive during self-isolation.

When being in self-isolation, as you know, I must contact my child’s school. I had to contact a homeroom teacher of my child. Actually I didn’t really do anything wrong, but I really, really felt bad. Wouldn’t the image appear strange to my child? Because of that thought, every time I thought about that, I thought if I should resign. (Participant N)

3.3.2. A Contrasting Perception of Nurses: Heroes of Society versus Subjects of Avoidance

Even with the “Thank you Challenge” campaign spreading among the public, to express gratitude and respect towards health care professionals who responded to COVID-19, nurses did not feel particularly gratified. In a pandemic, the true heroes fighting COVID-19 could only work efficiently in isolation from other people. Close neighbors viewed participants as dangerous sources of pollution or pathogens that threatened their safety. Unlike the warm gaze of the public to see the nurses, participants felt judged by those around them, which made their jobs more uncomfortable.

Above all, the most challenging thing is the social perspective of “these people are working in an isolation hospital now”. People close to me have this kind of perspective… When one of the nurses is reported on the news or the media as a confirmed patient, we also feel like cringing. Such social perspectives were very hard for us because we’ve become people that the public wants to avoid rather them feeling appreciation for us and thinking of us like we are working hard and trying our best. (Participant M)

3.4. Support for Caring

Sympathetic colleagues, and supportive and appreciative patients, encouraged participants to care for patients despite their difficulties. In addition, participants felt rewarded and proud of their care when they witnessed patients recovering, which further drove them to fulfill their duties.

3.4.1. Companionship and Sharing Difficulties

Participants endured difficult working routines with the support of colleagues, who best understood their struggles. In experiencing and sharing the same difficulties, participants found comfort with their colleagues. As nurses cannot quit, as that would mean additional pressures for their colleagues, they rely on each other for support.

To be honest, I think I’m being able to endure hard times thanks to my companionship. It’s hard for us all. And fortunately, all colleagues are friendly, and many colleagues are so considerate of each other. We’re not pushing each other to go in, but we are voluntarily working. Even though COVID-19 is hard for me, this companionship has helped me learn and endure with them until now. (Participant I)

3.4.2. Support and Appreciation from Patients and People

While struggling, words of support and appreciation from patients, family, and friends helped participants withstand their difficult situations.

A patient wrote a very long letter. “Thank you. Thank you so much for taking care of me, and I was moved by the hard work you did. And even in the heat, you never got annoyed”. Well, because the patient wrote a lot of appreciative words like this, I was really grateful. Somehow, apart from the money, I thought it was terrific to work. (Participant A)

3.4.3. A Sense of Satisfaction and Self-Esteem

The sense of satisfaction and self-esteem felt while caring for COVID-19 patients became an essential incentive for participants to remain in nursing. When patients hospitalized in severe conditions were able to recover, participants felt rewarded by their occupation, and their self-esteem was increased.

At first, the patient‘s condition was so bad. So, we thought the patient would actually die, but it turned out that the patient improved so much and was discharged later. We felt like we were being compensated for the hard work. I had pride that we did an excellent job in nursing. (Participant D)

3.5. Expectations for Post-COVID-19 Life

As COVID-19 keeps persisting in everyday life, expectations for life after COVID-19 are gradually blurring. Participants are unsure if there will ever be a time when they can care for their patients without protective clothing. Much of what participants wanted to accomplish after COVID-19 has been delayed for at least a year, but they have some expectations and are preparing for another future.

3.5.1. Restoring Everyday Life

Even in the current uncertain situation, participants have sincerely performed their nursing duties, while dreaming of restoring daily life. They recognized the importance of everyday social activities, such as eating together, watching movies, capturing bright smiles on camera, and realized that these activities were all they wished to do. Conversely, along with these wishes, there are also concerns about being able to return to the past sense of normalcy.

Returning to normality is what I want the most, and I think the next step is to think about it together with the management team and the government. I believe our request should be reviewed to combat physical exhaustion, and psychotherapists need to be involved and actively work on recovering. It’s not just that we get rest. Professional intervention is necessary. (Participant M)

3.5.2. Preparing for the Future

Participants encountered COVID-19, which occurred several years after the Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) epidemic, as another infectious disease that was able to threaten society at any time. In addition, chaotic situations in the hospital were not promptly managed, as the effects of the virus were so severe and fast that the experience of nursing MERS patients became insignificant. The MERS experience was inadequate in training healthcare providers to respond to similar future emergencies. Accordingly, efforts have been made to incorporate the vivid nursing experiences of COVID-19 into protocols against bracing for other diseases in the future.

That’s why even though I don’t know when the COVID-19 pandemic will end, once it’s over, I think the protocol needs to be more complete. Furthermore, I think we should regularly stockpile a certain amount of items for the future. And, we need to plan a little more neatly how to manage nursing staff systematically. (Participant K)

Since we don’t know when another infectious disease will afflict us, we have to prepare a lot for response training to infectious diseases, facilities and personnel of institutions, and locations for care facilities. To reduce certain mistakes, I think we should prepare well now. (Participant M)

4. Discussion

This study was conducted to understand the meanings and essence of the experiences of nurses who cared for COVID-19 patients, using a descriptive phenomenological method. As a result of this study, 5 theme clusters and 12 themes were extracted.

The first theme cluster indicated that the nurses struggled under the weight of dealing with infectious diseases. Participants expressed anxiety and fear in the absence of a definitive treatment for COVID-19. This is similar to the results of previous studies that reported that the lack of information and knowledge about unfamiliar diseases leads to ambiguity in nursing services, resulting in nurses feeling fearful and anxious [ 33 ]. The anxiety and fear accompanying patient care may be the result of rushing to the battlefield without any preparation [ 19 ]. In addition, participants appeared to have persistent fears of unintentional exposure and of transmitting the virus to co-workers [ 34 ]. Nurses who performed shift work during COVID-19 had a significantly increased association between COVID-19-related work stressors and anxiety disorder [ 24 ]. These physiological and psychological conditions are reported to create high stress and further lead to post-traumatic stress [ 35 ]. Hence, nurses caring for COVID-19 patients require continuous evaluation and management to sustain their mental wellbeing.

In the COVID-19 pandemic, nurses are experiencing ethical anguish in the face of unique situations that they have never experienced before. In particular, watching patients pass away alone, in isolation, without the support and comfort of family members, causes unimaginable shock and anguish. Moral distress between patient dignity and infection control is a similar experience to nurses in other countries, reported in previous studies. Nurses are known to experience contradictory feelings [ 18 ] as they experience the pressure of having to coordinate their responsibilities for the prevention of COVID-19 infection, along with other moral responsibilities [ 16 ].

Therefore, we need to create an ethically supportive environment [ 36 ], not just alleviate the ethical distress experienced by nurses [ 37 ]. In addition, it is necessary to find ways to guarantee both infection control and dignified death; for instance, family members can wear protective clothing and safely participate in their relatives’ end-of-life processes. Other measures to ensure a dignified death include minimal post-mortem medical interference, and respect for and adherence to cultural customs [ 38 ].

The second theme cluster was participants’ aggravated caring difficulties. Participants in this study were uncomfortable with the heat and sweat caused by wearing sealed PPE. This seems to be a slightly different experience than the Italian nurses who raised some concerns about the lack of PPE, the inadequacy of PPE, and the lack of guidelines for proper use [ 15 ]. In Korea, where resources, such as PPE, were relatively abundant since the COVID-19 pandemic declaration, wearing PPE acted as a triple pain burden on the safety of all people rather than the problem of lack of equipment.

It is similar to a previous study, demonstrating that these devices make it difficult to communicate with patients and perform basic tasks [ 34 ]. The appropriate wearing of PPE has been reported to protect medical staff from burnout [ 39 ]. However, continuous wearing of PPE can cause tissue damage or skin reactions, and prolonged wearing of goggles has been found to increase discomfort and fatigue due to abrasive straps and visual distortion [ 38 ]. Therefore, compliance with the PPE-wearing guidelines should be monitored and shift work should be assigned, taking into account the maximum period during which nurses are allowed to wear protective equipment.

It has also been found that medical workload has been excessively delegated to nurses taking care of COVID-19 patients. Policies to minimize social contact with patients have burdened nurses with extra tasks, causing exhaustion [ 40 ]. The excessive increase in work burden is in line with the results of qualitative research on the experience of nurses in other countries. A study by Liu et al. [ 34 ], in the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, reported that nurses had done a lot of work. Recent studies also reported that COVID-19 caused a lot of work for nurses [ 20 ], and the treatment characterized by many isolated patients increased the work of nurses exponentially [ 14 ]. Nurses are constantly aware of new knowledge and skills associated with evolving pandemics and viruses, and receive new training, in preparation for adapting to the situation and providing care for suspected or identified patients [ 20 ]. In addition, frequent changes of working locations and wards, changes in work schedules, and confusion over working guidelines, have made nurses’ lives uncertain.

The final theme of the challenge with difficult care was the confusing and uncertain working conditions, partly related to nursing staffing [ 14 ]. However, it was more difficult for the participants in this study to be able to predict their work schedule, rather than the shortage of nursing personnel. This may be due to the difficulty in predicting the hospitalization rates of infected patients and the problems caused by frequent and rapid relocation of nurses, depending on the number of hospitalized patients. In this study, the uncertainty in working conditions is consistent with the report by Liang et al. [ 20 ], that there was uncertainty among nurses about being transferred to the areas where the epidemic was most serious. Moreover, the ambiguity surrounding COVID-19 and whether patients have contracted it have been shown to increase nurses’ stress [ 33 ]. Even in such situations, thoroughly preparing for and predicting potential emergency situations, based on comprehensive data analysis, knowledge accumulation, and education, can reduce the uncertainty and anxiety surrounding infectious diseases.