AIN'T I A WOMAN?

by Sojourner Truth

Delivered 1851 at the Women's Convention in Akron, Ohio

Well, children, where there is so much racket there must be something out of kilter. I think that 'twixt the negroes of the South and the women at the North, all talking about rights, the white men will be in a fix pretty soon. But what's all this here talking about?

That man over there says that women need to be helped into carriages, and lifted over ditches, and to have the best place everywhere. Nobody ever helps me into carriages, or over mud-puddles, or gives me any best place! And ain't I a woman? Look at me! Look at my arm! I have ploughed and planted, and gathered into barns, and no man could head me! And ain't I a woman? I could work as much and eat as much as a man - when I could get it - and bear the lash as well! And ain't I a woman? I have borne thirteen children, and seen most all sold off to slavery, and when I cried out with my mother's grief, none but Jesus heard me! And ain't I a woman? Then they talk about this thing in the head; what's this they call it? [member of audience whispers, "intellect"] That's it, honey. What's that got to do with women's rights or negroes' rights? If my cup won't hold but a pint, and yours holds a quart, wouldn't you be mean not to let me have my little half measure full? Then that little man in black there, he says women can't have as much rights as men, 'cause Christ wasn't a woman! Where did your Christ come from? Where did your Christ come from? From God and a woman! Man had nothing to do with Him. If the first woman God ever made was strong enough to turn the world upside down all alone, these women together ought to be able to turn it back , and get it right side up again! And now they is asking to do it, the men better let them. Obliged to you for hearing me, and now old Sojourner ain't got nothing more to say.

“Ain’t I a Woman?” Speech Transcript – Sojourner Truth

Full transcript of Sojourner Truth’s famous “Ain’t I a Woman” speech from May 29, 1851.

Sojourner Truth: ( 00:14 ) Well children … Well there is so much racket there must be something out of kilter. I think that betwixt the Negroes of the South and the women at the North all talking about rights these white men going to be in a fix pretty soon.

Sojourner Truth: ( 00:35 ) But what’s all this here talking about? That man over there says that women need to be helped into carriages, and lifted over ditches, and to have the best place everywhere. Nobody ever helped me into carriages, or over mud puddles, or gives me any best place. Ain’t I a woman?

Sojourner Truth: ( 00:58 ) Look at me, look at my arms, I have plowed, and planted, and gathered in the barns, and no man can head me. And ain’t I a woman? I could work as much, and eat as much as a man when I could get it, and bear the lash as well. And ain’t I a woman? I have borne 13 children and seen most all sold off to slavery. And when I cried out with my mother’s grief none but Jesus heard me. And ain’t I a woman?

Sojourner Truth: ( 01:56 ) Then they talk about this thing in the head … What’s this they call it? What’s this they call it?

Sojourner Truth: ( 02:02 ) Intellect, that’s it honey. Intellect. What’s that got to do with women’s rights and Negroes’ rights? If my cup will hold but a pint, and yours will hold a quart, wouldn’t you be mean not to let me have my little half measure fool?

Sojourner Truth: ( 02:31 ) And then that man back there in the black … That man back in the black says that women can’t have as much rights as men because Christ wasn’t a woman. Where did your Christ come from? Where did your Christ come from? From God and a woman. Man had nothing to do with him. Now if the first woman that God ever made was strong enough to turn this world upside down all alone, these women together ought to be able to turn it back and get it right side up again. And now they is asking to do it and you men better let them.

Sojourner Truth: ( 03:32 ) Obliged to you. Thank you for letting me speak to you this morning. Now old Sojourner ain’t got nothing more to say.

Transcribe Your Own Content Try Rev and save time transcribing, captioning, and subtitling.

Other Related Transcripts

Stay updated.

Get a weekly digest of the week’s most important transcripts in your inbox. It’s the news, without the news.

BlackPast is dedicated to providing a global audience with reliable and accurate information on the history of African America and of people of African ancestry around the world. We aim to promote greater understanding through this knowledge to generate constructive change in our society.

(1851) sojourner truth “ar’nt i a woman“.

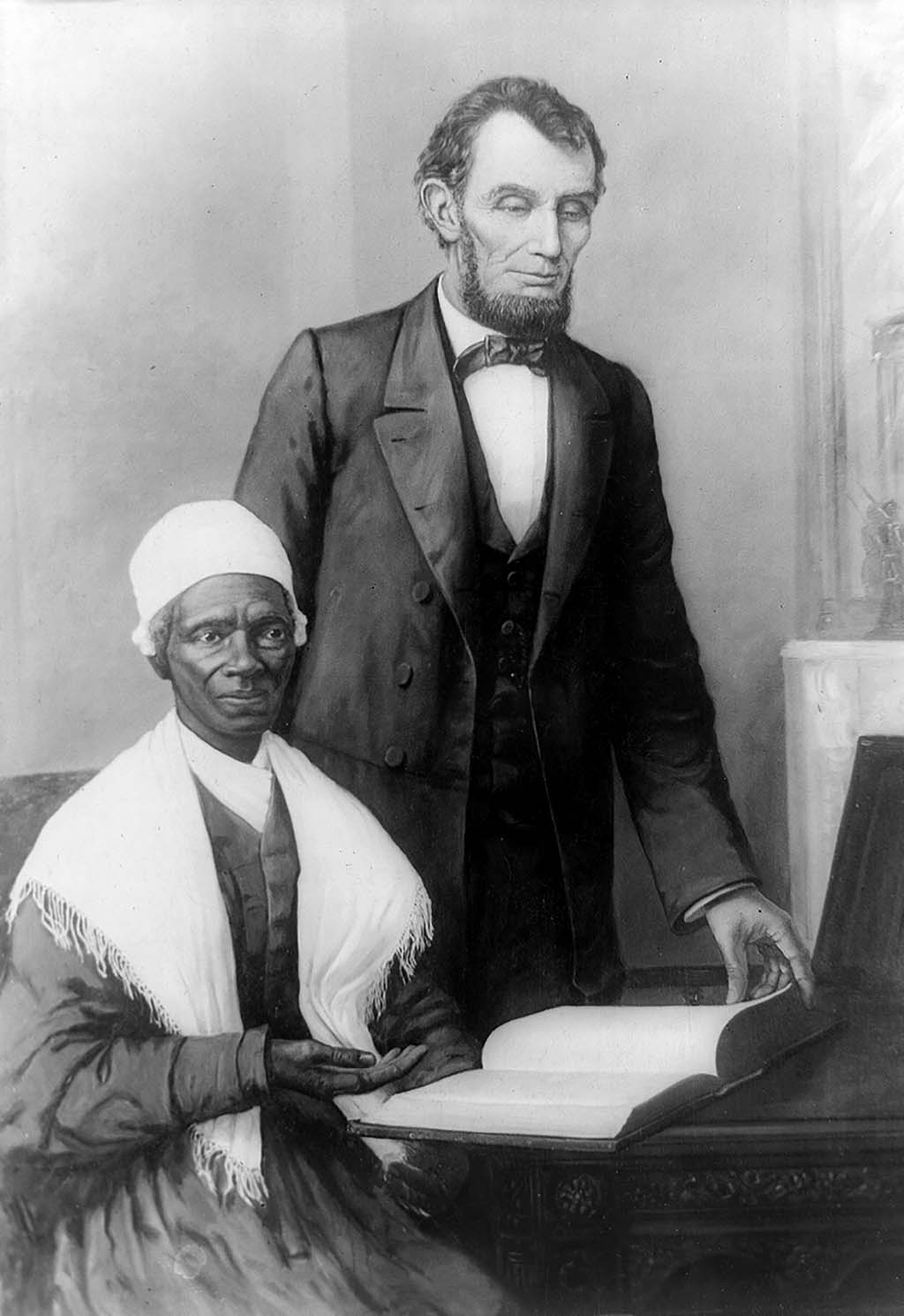

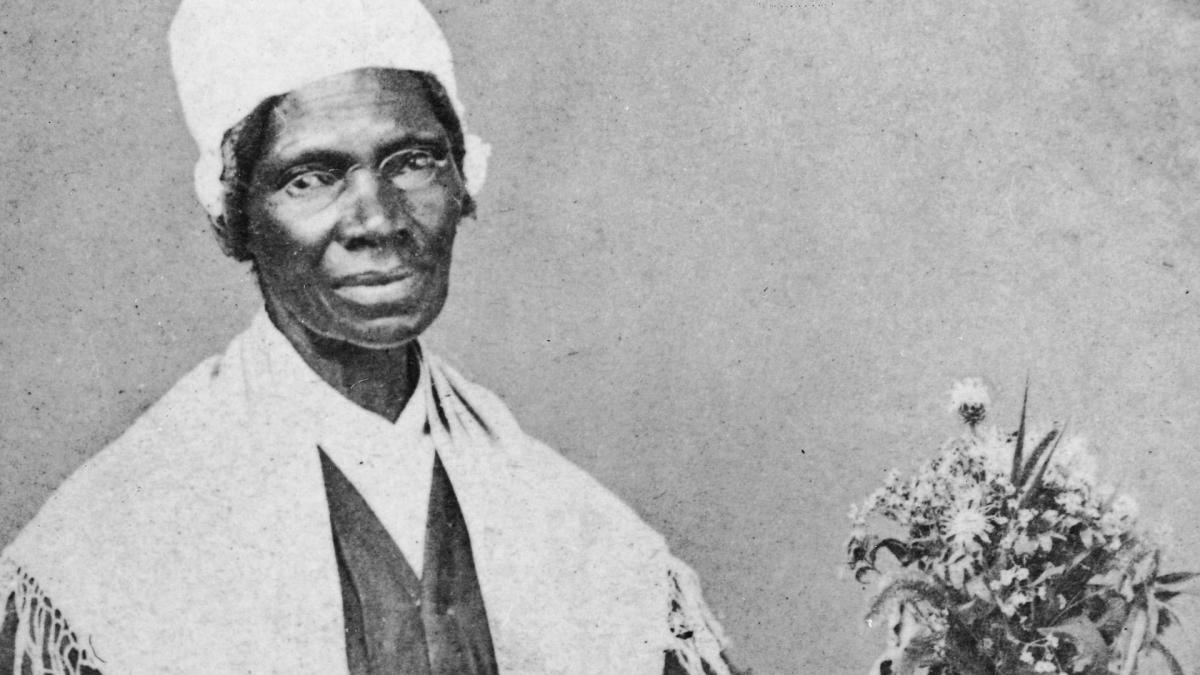

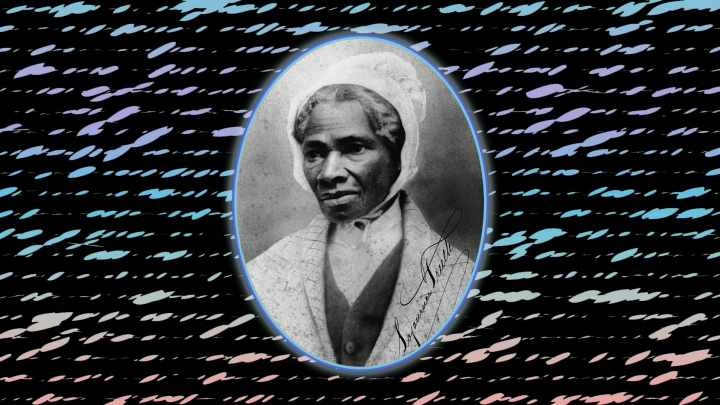

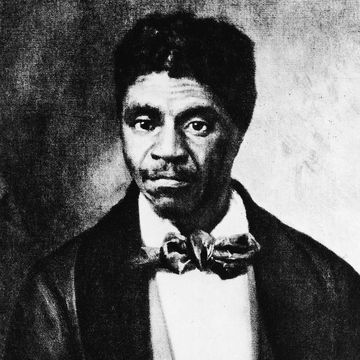

Sojourner Truth (c. 1797-1883) was arguably the most famous of the 19th Century black women orators. Born into slavery in New York and freed in 1827 under the state’s gradual emancipation law, she dedicated her life to abolition and equal rights for women and men. Two versions of her most noted speech appear below. Scholars agree that the speech was given at the Women’s Rights Convention in Akron, Ohio, on May 29, 1851. After that, there is much debate about what she said and how she said it. The version that is most quoted was published in the 1875 edition of Truth’s Narrative (which was written by others) and in Elizabeth Cady Stanton’s History of Woman Suffrage which appeared in 1881. Both versions were published 25 years after Truth spoke. However the Salem, Ohio, Anti-Slavery Bugle published its version of the speech on June 21, 1851. Since that version appeared within a month of her presentation, many historians believe it to be the more accurate rendering of the talk. However both versions rely on the interpretations of others. Since no written transcript of the speech has appeared, what Truth actually said, as historian Nell Painter has pointed out, will probably never be known.

Well, children, where there is so much racket there must be something out of kilter. I think that ‘twixt the negroes of the South and the women at the North, all talking about rights, the white men will be in a fix pretty soon. But what’s all this here talking about?

That man over there says women need to be helped into carriages, and lifted over ditches, and to have the best place everywhere. Nobody ever helps me into carriages, or over mud-puddles, or gives me any best place! And arn’t I a woman? Look at me! Look at my arm! I have ploughed, and planted , and gathered into barns, and no man could head me! And arn’t I woman? I could work as much and eat as much as a man—when I could get it—and bear the lash as well! And arn’t I a woman? I have borne thirteen children, and seen them most all sold off to slavery, and when I cried out with my mother’s grief, none but Jesus heard me! And aren’t I a woman?

Then they talk about this thing in the head; what’s this they call it? [“Intellect,” whispered someone near.] That’s it, honey. What’s that got to do with women’s rights or negro rights? If my cup won’t hold but a pint, and yours holds a quart, wouldn’t you be mean not to let me have my little half-measure full? Then that little man in black there, he says women can’t have as much rights as men, because Christ wasn’t a woman! Where did your Christ come from? From God and a woman! Man had nothing to do with Him….

If the first woman God ever made was strong enough to turn the world upside down all alone, these women together ought to be able to turn it back, and get it right side up again! And now they are asking to do it, the men better let them.

FROM THE ANTI-SLAVERY BUGLE:

One of the most unique and interesting speeches of the convention was made by Sojourner’s Truth, an emancipated slave. It is impossible to transfer it to paper, or convey any adequate idea of the effect it produced upon the audience. Those only can appreciate it who saw her powerful form, her whole-souled, earnest gesture, and listened to her strong and truthful tones. She came forward to the platform and addressing the President said with great simplicity:

May I say a few words? Receiving an affirmative answer, she proceeded; I want to say a few words about this matter. I am a woman’s rights [sic]. I have as much muscle as any man, and can do as much work as any man. I have plowed and reaped and husked and chopped and mowed, and can any man do more than that? I have heard much about the sexes being equal; I can carry as much as any man, and can eat as much too, if I can get it. I am strong as any man that is now.

As for intellect, all I can say is, if woman have a pint and man a quart—why can’t she have her little pint full? You need not be afraid to give us our rights for fear we will take too much—for we won’t take more than our pint’ll hold.

The poor men seem to be all in confusion and don’t know what to do. Why children, if you have woman’s rights give it to her and you will feel better. You will have your own rights, and they won’t be so much trouble.

I can’t read, but I can hear. I have heard the Bible and have learned that Eve caused man to sin. Well if woman upset the world, do give her a chance to set it right side up again. The lady has spoken about Jesus, how he never spurned woman from him, and she was right. When Lazarus died, Mary and Martha came to him with faith and love and besought him to raise their brother. And Jesus wept—and Lazarus came forth. And how came Jesus into the world? Through God who created him and woman who bore him. Man, where is your part?

But the women are coming up blessed be God and a few of the men are coming up with them. But man is in a tight place, the poor slave is on him, woman is coming on him, and he is surely between a hawk and a buzzard.

Do you find this information helpful? A small donation would help us keep this available to all. Forego a bottle of soda and donate its cost to us for the information you just learned, and feel good about helping to make it available to everyone.

BlackPast.org is a 501(c)(3) non-profit and our EIN is 26-1625373. Your donation is fully tax-deductible.

Cite this entry in APA format:

Source of the author's information:.

Elizabeth C. Stanton, S. B. Anthony, and Matilda J. Gage, History of Woman Suffrage , vol. 1 (Rochester, N. Y.: Charles Mann, 1887), p. 116; Anti-Slavery Bugle (Salem, OH) June 21, 1851.

Your support is crucial to our mission.

Donate today to help us advance Black history education and foster a more inclusive understanding of our shared cultural heritage.

- HISTORY & CULTURE

Sojourner Truth’s battle cry still resonates 170 years later

Her famous “Ain’t I a woman?” speech helped launch the women's suffrage movement and symbolizes America’s ongoing fight for fairness and equity.

For Barbara Allen, the ironies of traveling to Angola, Indiana, on June 6 are fairly obvious. She’ll be participating in the unveiling of a statue at the Steuben County Courthouse honoring the legendary formerly enslaved abolitionist and women’s rights activist Sojourner Truth.

The first irony is that Sojourner Truth is Barbara Allen’s sixth great-grandmother, born in 1797 in New York State and who died in Battle Creek, Michigan in 1893. The second irony is that at least once during Truth’s Indiana tour in 1861, she was arrested for speaking. It was a risk she took every time she stepped on a podium, and Allen can feel that resolve flowing through her veins.

“Just like she would holler for some rights, I’ve always had the need to speak up and speak out. And that’s where my personality comes from. When I look back on my own life, I think, ‘Oh my God, life just goes in circles, and I’m in that circle.’ “

That full-circle moment amplifies the growing stature of Truth, an iconic symbol of the interwoven threads in the fight for racial and gender justice in America. Allen has written a children’s book about her revered ancestor, “Remembering Great Grandma, Sojourner Truth,” which she self-published in January. She hopes her own public readings and speeches will help her three granddaughters connect more deeply with their iconic legacy. At a time when the country is embroiled in wrenching debates about the need to acknowledge past grievous wrongs, Sojourner Truth’s story of courage, strength and self-made mastery offers an important template for the pursuit of fairness and self-expression.

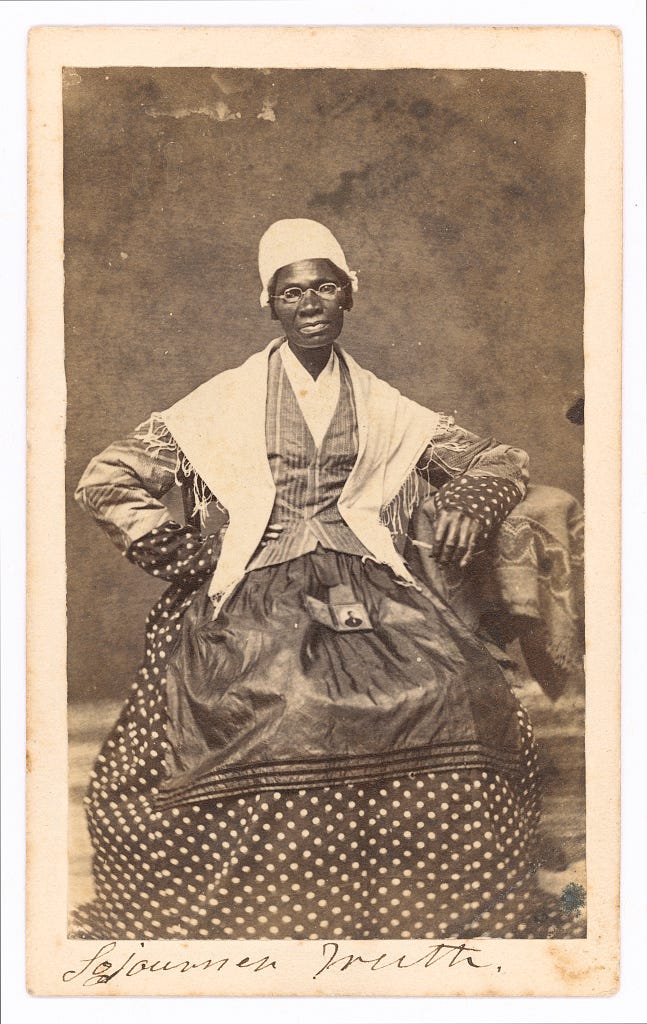

Truth was a commanding presence without uttering a word, standing at nearly 6 feet tall. Born Isabella Baumfree, the details of her life are vivid and wrenching. She was sold on multiple auction blocks, raped by at least one owner, and watched her own children sold. Truth also became one of the first Black women in American history to win a legal case against a white man for selling her son Peter.

With her powerful voice, inflected with the Dutch accent of her former enslavers, Truth instinctively used the power of her bearing and persona to captivate audiences. She wore ornate bonnets and clothing to disarm the stereotypical expectations of the people she encountered. In many ways, Truth demonstrated a keen pre-social media savvy about how to market herself in the feminist and abolitionist realms.

For Hungry Minds

Her spiritual awakening, her drive to travel throughout America condemning slavery and demanding equality for women all seemed to coalesce in her legendary remarks at the May 29, 1851 Ohio Women’s Rights Convention in Akron—the famous “Ain’t I A Woman?” speech, delivered on the spot with no preparation, as were all of her speeches. It has since been performed on countless stages, recited at festivals and delivered during school competitions as a declaration of strength, pride and overcoming obstacles.

“The respect they showed, and the way they talked about how her life inspired them, it was a little overwhelming.” Barbara Allen , Sojourner Truth's sixth great-granddaughter

Though Truth and other Black female activists chafed at the comparisons white feminists drew between their societal status and slavery, they agreed on the urgent need for fairness and equity in the quest for women’s rights. As Johns Hopkins historian Martha S. Jones notes in her 2020 book “Vanguard: How Black Women Broke Barriers, Won the Vote and Insisted on Equality for All,” Truth never wavered in her belief that she was best suited to symbolize the need for gender justice. Jones writes:

“Truth had waited her turn in Akron, following women whose remarks showcased their high levels of education, status, and experience. She could not match such credentials. Still, during her years on the lecture circuit she had learned to riff off the remarks that preceded her own, and it paid off. Truth reframed the convention, resetting its goals as defined from the perspective of a Black woman. She began, ‘I want to say a few words about this matter. I am a woman’s rights.’ There, as she was, unlettered and unrefined, Truth made the case that she was the truest embodiment of women’s rights. Slavery was no mere metaphor and the labor it demanded had made Truth the equal of any man.”

“I have as much muscle as any man and can do as much work as any man,” Truth said in Akron.

Truth continued:

“Then they talk about this thing in the head—what’s this they call it? (an audience member whispers ‘intellect’) That’s it, honey. What’s that got to do with women’s rights or negroes rights? If my cup won’t hold but a pint, and yours holds a quart, wouldn’t you be mean not to let me have my little half measure full?”

There’s yet another irony contained in the lore connected to Truth’s speech: it’s more than likely that she never actually said the words, “Ain’t I A Woman?” When an official document outlining the proceedings of the Ohio Women’s Rights Convention was published, Truth’s speech was not included.

But journalists Marius R. Robinson and Emily Robinson, who wrote for the Anti-Slavery Bugle, were in the audience and provided a transcription of her remarks for that newspaper. Twelve years after the Convention, abolitionist and women’s rights activist Frances Dana Barker Gage published her own interpretation of the speech. ( The Sojourner Truth Project has produced an online comparison of the two main written versions. )

It's easy to get tangled up in those kinds of details about an historical icon’s life. Allen offers another example: though in the speech Truth declares that she bore 13 children, historians have only been able to confirm the birth of five, the youngest of which was Allen’s fifth great grandmother, Sophia.

After years of keeping the vivid stories she’d learned during bedtime to herself, Allen says it was only when the city of Battle Creek erected a statue in her honor in 1999 that the truest depths of her link to Sojourner Truth set in.

You May Also Like

10 million enslaved Americans' names are missing from history. AI is helping identify them.

This Black artist’s vibrant quilts inspired generations of U.S. artisans

This writer just traced his enslaved ancestors all the way to Africa. Here’s how.

“It was the way people in the crowd looked at me, and there were 3,000 people in that crowd,” Allen says. “The respect they showed, and the way they talked about how her life inspired them, it was a little overwhelming.”

And when local historian Michael John Martich and his wife Dorothy introduced themselves to Allen, her fate was sealed.

“They had copies of Sophia’s death certificate and ones belonging to other relatives. My mother didn’t really have much information about Sophia, so I all I did know is that (Truth) went back for one of her children. That’s when I understood how much people loved and revered her, and I knew I had a responsibility to make sure that my life honors her.”

Truth is also part of the ongoing discussion about who America honors in public spaces. In August of 2020, as part of the commemoration of American women’s suffrage, a bronze monument depicting 19th century women’s rights activists Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony , and Sojourner Truth was unveiled in New York City’s Central Park, the first to depict real women instead of mythical females like Alice in Wonderland.

But the path to a final monument was filled with controversy. The original design only included Stanton and Anthony, and the ensuing outcry added to mounting public objections to what’s been termed as “whitewashing” of American history. So as confederate statues and ornate sculptures for other historically controversial figures are pulled down, last October, the Mellon Foundation announced a $250 million commitment to create contextualize and relocate existing monuments to better reflect America’s diversity and include the contributions of activists whose work has been ignored or sidelined.

As the 170th anniversary of Truth’s historic speech nears, Allen says her children’s book is a labor of love and necessity.

“I’m going to have to sell some shadow, this book, to support some substance,” she says, laughing while borrowing one of her great grandma’s iconic sayings to describe her own journey. After a career in finance, a stint in divinity school and raising two sons, Allen says she had an epiphany, much like the one that made Isabella Baumfree change her name.

“I woke up in the middle of the night, and I clearly heard God’s voice telling me to write a book,” Allen says. Something about Truth’s story always resonated with her.

“She always knew, even as a little girl, that she had a bigger purpose than just being a slave,” Allen says. “When her slave master promised to free her, and then broke that promise, can you imagine having the strength to walk away?”

What’s more, Allen says, after Truth had mustered the nerve to leave, she turned around and went back to the plantation to retrieve her youngest daughter, Sophia. “If she hadn’t gone back, I probably wouldn’t be here,” she says. “I owe my life to that kind of courage.”

Allen has finally embraced the opportunity to continue the message her ancestor fought to transmit, loudly and clearly.

“We can use our voices to make change,” Allen says. “That’s why I think she’s being recognized so much right now. Her life shows that you can help change history by that spoken word.”

Related Topics

- AFRICAN AMERICANS

Juneteenth is America’s second Independence Day—here’s why

These Black transgender activists are fighting to ‘simply be’

Harriet Tubman, the spy: uncovering her secret Civil War missions

Fierce and female, these 7 warriors fought their way into history

MLK and Malcolm X only met once. Here’s the story behind an iconic image.

- Paid Content

- Environment

- Photography

- Perpetual Planet

History & Culture

- History & Culture

- History Magazine

- Mind, Body, Wonder

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Your US State Privacy Rights

- Children's Online Privacy Policy

- Interest-Based Ads

- About Nielsen Measurement

- Do Not Sell or Share My Personal Information

- Nat Geo Home

- Attend a Live Event

- Book a Trip

- Inspire Your Kids

- Shop Nat Geo

- Visit the D.C. Museum

- Learn About Our Impact

- Support Our Mission

- Advertise With Us

- Customer Service

- Renew Subscription

- Manage Your Subscription

- Work at Nat Geo

- Sign Up for Our Newsletters

- Contribute to Protect the Planet

Copyright © 1996-2015 National Geographic Society Copyright © 2015-2024 National Geographic Partners, LLC. All rights reserved

[Sojourner Truth spoke in a southern dialect that might be difficult for modern readers. Here is the speech in modern English:]

Well, children, where there is so much racket there must be something out of kilter. I think that 'twixt the negroes of the South and the women at the North, all talking about rights, the white men will be in a fix pretty soon. But what's all this here talking about?

That man over there says that women need to be helped into carriages, and lifted over ditches, and to have the best place everywhere. Nobody ever helps me into carriages, or over mud-puddles, or gives me any best place! And ar'n't I a woman?

Look at me! Look at my arm! I have ploughed and planted, and gathered into barns, and no man could head me! And ar'n't I a woman?

I could work as much and eat as much as a man - when I could get it - and bear the lash as well! And ain't I a woman?

I have borne thirteen children, and seen most all sold off to slavery, and when I cried out with my mother's grief, none but Jesus heard me! And ain't I a woman?

Then they talk about this thing in the head; what's this they call it? [member of audience whispers, "intellect"] That's it, honey. What's that got to do with women's rights or negroes' rights? If my cup won't hold but a pint, and yours holds a quart, wouldn't you be mean not to let me have my little half measure full?

Then that little man in black there, he says women can't have as much rights as men, 'cause Christ wasn't a woman! Where did your Christ come from? Where did your Christ come from? From God and a woman! Man had nothing to do with Him.

If the first woman God ever made was strong enough to turn the world upside down all alone, these women together ought to be able to turn it back and get it right side up again!

And now they is asking to do it, the men better let them.

Obliged to you for hearing me, and now old Sojourner ain't got nothing more to say.

Wall, chilern, whar dar is so much racket dar must be somethin' out o' kilter. I tink dat 'twixt de niggers of de Souf and de womin at de Norf, all talkin' 'bout rights, de white men will be in a fix pretty soon. But what's all dis here talkin' 'bout? Dat man ober dar say dat womin needs to be helped into carriages, and lifted ober ditches, and to hab de best place everywhar. Nobody eber helps me into carriages, or ober mud-puddles, or gibs me any best place!"

And raising herself to her full height, and her voice to a pitch like rolling thunder, she asked:

And ain't I a woman? Look at me! Look at my arm!

And she bared her right arm to the shoulder, showing her tremendous muscular power.

I have ploughed, and planted, and gathered into barns, and no man could head me! And ain't I a woman? I could work as much and eat as much as a man, when I could get it, and bear de lash as well! And ain't I a woman? I have borne thirteen chilern, and seen 'em mos' all sold off to slavery, and when I cried out with my mother's grief, none but Jesus heard me! And ain't I a woman? Den dey talks 'bout dis ting in de head; what dis dey call it?

"Intellect," whispered some one near.

Dat's it, honey. What's dat got to do wid womin's rights or nigger's rights? If my cup won't hold but a pint, and yourn holds a quart, wouldn't ye be mean not to let me have my little half-measure full?

And she pointed her significant finger, and sent a keen glance at the minister who had made the argument. The cheering was long and loud.

Den dat little man in black dar, he say women can't have as much rights as men, 'cause Christ wan't a woman! Whar did your Christ come from?

Rolling thunder couldn't have stilled that crowd, as did those deep, wonderful tones, as she stood there with out-stretched arms and eyes of fire. Raising her voice still louder, she repeated ,

Whar did your Christ come from? From God and a woman! Man had nothin' to do wid Him.

Oh, what a rebuke that was to that little man. Turning again to another objector, she took up the defense of Mother Eve. I can not follow her through it all. It was pointed, and witty, and solemn; eliciting at almost every sentence deafening applause; and she ended by asserting:

If de fust woman God ever made was strong enough to turn de world upside down all alone, dese women togedder

and she glanced her eye over the platform

ought to be able to turn it back, and get it right side up again! And now dey is asking to do it, de men better let 'em."

Long-continued cheering greeted this.

'Bleeged to ye for hearin' on me, and now ole Sojourner han't got nothin' more to say."

[Recent scholarship has disputed whether this account, written about 30 years after the speech was given, is an accurate representation of Truth's speaking style. The dialect, in particular, may have been an addition by Gage. For more on this dispute, see Aint I A Woman Delivered by Sojourner Truth by About's Guide to African American History, Jessica McElrath.]

More History

Picture Archive A - C Picture Archive D - M Picture Archive N - Z

Attila short biography Map of Attila's empire Battle of the Catalaunian Plains Who were the Huns?

A Summary and Analysis of Sojourner Truth’s ‘Ain’t I a Woman?’

By Dr Oliver Tearle (Loughborough University)

‘Ain’t I a Woman?’ – sometimes known as ‘Ar’n’t I a Woman?’ – is the title of a speech which Sojourner Truth, a freed African slave living in the United States, delivered in 1851 at the Women’s Convention in Akron, Ohio. The actual text of the speech has been the subject of some debate and contention, since there are several versions in circulation; but perhaps the most ‘authoritative’ record of the speech is the one given in The Norton Anthology of African American Literature .

This is the version of ‘Ain’t I a Woman?’ which we reproduce below, offering a summary of Sojourner Truth’s words and an analysis of their meaning.

A brief word on the context of the speech: the women in attendance at the Women’s Convention in 1851 were being challenged to call for the right to vote. In her speech, Sojourner Truth was attempting to persuade the audience to give women the vote.

‘Ain’t I a Woman?’: summary

The text of Sojourner Truth’s speech is given below in italics, followed by our commentary.

One of the most unique and interesting speeches of the convention was made by Sojourner Truth, an emancipated slave. It is impossible to transfer it to paper, or convey any adequate idea of the effect it produced upon the audience. Those only can appreciate it who saw her powerful form, her whole-souled, earnest gesture, and listened to her strong and truthful tones. She came forward to the platform and addressing the President said with great simplicity: ‘May I say a few words?’ Receiving an affirmative answer, she proceeded:

These are the prefatory words which introduce Sojourner Truth’s own words. Truth, who was born Isabella Baumfree in around 1797, had been born into slavery in New York, but she managed to escape with her daughter in 1826. She later adopted the name Sojourner Truth and became a prominent abolitionist and activist for women’s rights. ‘Ain’t I a Woman?’ is her most famous speech.

I want to say a few words about this matter. I am a woman’s rights. I have as much muscle as any man, and can do as much work as any man. I have plowed and reaped and husked and chopped and mowed, and can any man do more than that? I have heard much about the sexes being equal. I can carry as much as any man, and can eat as much too, if I can get it. I am as strong as any man that is now.

Sojourner begins by asserting that she embodies women’s rights. She is as strong and hard-working as any man. She has toiled in the fields and performed all manner of back-breaking physical tasks to prove her worth. Using a rhetorical question to reinforce her point, she asks if any man can be found who could do more than she has done.

As for intellect, all I can say is, if a woman have a pint, and a man a quart — why can’t she have her little pint full? You need not be afraid to give us our rights for fear we will take too much, — for we can’t take more than our pint’ll hold. The poor men seems to be all in confusion, and don’t know what to do. Why children, if you have woman’s rights, give it to her and you will feel better. You will have your own rights, and they won’t be so much trouble.

On the issue of intellect, however, Sojourner awards men twice the intelligence of women (a quart is so named because it’s a ‘quarter’ of a gallon – that is, two pints). But if women have half the intellect of a man (something with which modern neuroscience would strongly disagree ), women can still use the intellect they possess to the full.

Men have little to fear from giving women their rights. Women won’t take more than is their due, for it would be useless to them. Here, we see how clever Sojourner’s downplaying of women intelligence is: it implies that, because they have modest intellect compared with men, women will be modest in their ambitions, too. They won’t get too cunning and try to take more than they deserve.

Truth argues that men seem confused over this issue. Surely it’s preferable to grant women their rights, because men’s rights remain untouched by doing so, and women, having been granted their wish, will stop causing trouble and protesting for their rights, once they have them.

I can’t read, but I can hear. I have heard the bible and have learned that Eve caused man to sin. Well, if woman upset the world, do give her a chance to set it right side up again. The Lady has spoken about Jesus, how he never spurned woman from him, and she was right. When Lazarus died, Mary and Martha came to him with faith and love and besought him to raise their brother. And Jesus wept and Lazarus came forth.

She continues:

A nd how came Jesus into the world? Through God who created him and the woman who bore him. Man, where was your part? But the women are coming up blessed be God and a few of the men are coming up with them. But man is in a tight place, the poor slave is on him, woman is coming on him, he is surely between a hawk and a buzzard.

Truth, who was inspired by Christianity to reinvent her identity as Sojourner Truth, calls upon biblical authority next. In the Book of Genesis, we are told that Eve was tempted by the serpent into committing sin and eating the forbidden fruit. Sojourner argues that, if women were responsible for introducing chaos into the world, women should be given a chance to right the world’s wrongs. Giving women their rights is actually giving them responsibility for the world, or at least a share in our responsibility towards it.

Next, Sojourner Truth refers to a New Testament story, from chapter 11 of the Gospel of John , in which Jesus raises Lazarus from the dead . When Jesus arrives at the tomb of Lazarus, he weeps (John 11:35 is the shortest verse in the Bible: just two words, ‘Jesus wept’). Sojourner’s point is that Jesus did not spurn the women who came to him for help: instead, he listened to them and he helped raise their brother from the dead.

Jesus came into the world through his mother, the Virgin Mary. Sojourner Truth is using biblical authority to add weight to her argument that women have played an important part in the world and deserve to have their rights. (She asks another rhetorical question, brazenly asking of the men listening, ‘where was your part?’ God was Jesus’ father, and Joseph, strictly speaking, was surplus to requirements, after all. The earthly role of bringing Jesus into the world was achieved entirely by woman.)

Sojourner Truth concludes her speech by pointing out that the tide is turning. Both slaves and women are rising up against their (white, male) oppressors and lawmakers, and demanding their rights and freedom. 1851, the year she gave her speech, was just one year before the publication of Uncle Tom’s Cabin , the runaway bestseller by Harriet Beecher Stowe, who was an abolitionist as well as a novelist.

Uncle Tom’s Cabin made the case for freeing African slaves and became one of the most popular novels ever published. It was even said (although the statement appears to be apocryphal ) that when Abraham Lincoln met Stowe during the American Civil War a decade later, he remarked, ‘So you’re the little woman who wrote the book that made this great war!’

As both an ex-slave and a woman, Sojourner Truth knew about the plight of both groups of people in the United States. Her speech shows her audience the times: change is coming, and it is time to give women the rights that should be theirs. Man (and she means man , specifically) is ‘between a hawk and a buzzard’, fighting a war on two fronts: he is facing opposition from the abolitionists who argue that slaves should be given their freedom and calls for them to give women their rights, too.

‘Ain’t I a Woman?’: analysis

We began this analysis by pointing out that the title of Sojourner Truth’s speech is variously given as ‘Ain’t I a Woman?’ and ‘Ar’n’t I a Woman?’ But we don’t even know if she said anything close to this, in fact.

Indeed, one reason her speech became widely known was thanks to Frances Gage, a poet and abolitionist, who passed Truth’s words (or a version of them) to the National Anti-Slavery Standard , where they were published on 2 May, 1863.

This was, of course, twelve years after the speech had actually been given, and we cannot be sure when Gage wrote down his remembered version of the speech he’d heard. Gage’s account of Sojourner Truth’s life wasn’t entirely accurate. She had five children, but he erroneously gave the number as thirteen, which is quite a margin of error.

But the version of Sojourner Truth’s speech given above, and analysed here, was written down shortly after she gave the speech in 1851. The scribe was a Marcus Robinson, who was a friend of Sojourner’s; he was present at the speech, and his version is widely regarded as the most authentic.

Discover more from Interesting Literature

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.

Type your email…

Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive.

Continue reading

- Skip to global NPS navigation

- Skip to this park navigation

- Skip to the main content

- Skip to this park information section

- Skip to the footer section

Exiting nps.gov

Alerts in effect, sojourner truth.

Last updated: September 2, 2017

Park footer

Contact info, mailing address:.

136 Fall Street Seneca Falls, NY 13148

315 568-0024

Stay Connected

Ain’t I a Woman?

The most widely quoted version of this famous speech appears first and is from The Narrative of Sojourner Truth , written by others and published in 1875. The second version is from the Salem, Ohio, Anti-Slavery Bugle , which published its version on June 21, 1851, one month after Truth’s presentation. Many scholars feel the Bugle ’s version is a more accurate portrayal of the speech since it was printed within one month of the convention. However, both versions rely upon personal accounts by others and no known transcript of the speech exists.

Narrative of Sojourner Truth version:

Well, children, where there is so much racket there must be something out of kilter. I think that ’twixt the negroes of the South and the women at the North, all talking about rights, the white men will be in a fix pretty soon. But what’s all this here talking about?

That man over there says that women need to be helped into carriages, and lifted over ditches, and to have the best place everywhere. Nobody ever helps me into carriages, or over mud-puddles, or gives me any best place! And ain’t I a woman?

Look at me! Look at my arm! I have ploughed and planted, and gathered into barns, and no man could head me! And ain’t I a woman?

I could work as much and eat as much as a man - when I could get it - and bear the lash as well! And ain’t I a woman?

I have borne thirteen children, and seen most all sold off to slavery, and when I cried out with my mother’s grief, none but Jesus heard me! And ain’t I a woman?

Then they talk about this thing in the head; what’s this they call it? (Member of audience whispers, “intellect.”) That’s it, honey. What’s that got to do with women’s rights or negroes’ rights? If my cup won’t hold but a pint, and yours holds a quart, wouldn’t you be mean not to let me have my little half measure full?

Then that little man in black there, he says women can’t have as much rights as men, ’cause Christ wasn’t a woman! Where did your Christ come from? Where did your Christ come from? From God and a woman! Man had nothing to do with Him.

If the first woman God ever made was strong enough to turn the world upside down all alone, these women together ought to be able to turn it back, and get it right side up again!

And now they is asking to do it, the men better let them.

Obliged to you for hearing me, and now old Sojourner ain’t got nothing more to say.

Anti-Slavery Bugle version:

One of the most unique and interesting speeches of the convention was made by Sojourner Truth, an emancipated slave. It is impossible to transfer it to paper, or convey any adequate idea of the effect it produced upon the audience. Those only can appreciate it who saw her powerful form, her whole-souled, earnest gesture, and listened to her strong and truthful tones. She came forward to the platform and addressing the President said with great simplicity: May I say a few words? Receiving an affirmative answer, she proceeded; I want to say a few words about this matter. I am a woman’s rights [ sic ]. I have as much muscle as any man, and can do as much work as any man. I have plowed and reaped and husked and chopped and mowed, and can any man do more than that? I have heard much about the sexes being equal; I can carry as much as any man, and can eat as much too, if I can get it. I am strong as any man that is now. As for intellect, all I can say is, if woman have a pint and man a quart—why can’t she have her little pint full? You need not be afraid to give us our rights for fear we will take too much—for we won’t take more than our pint’ll hold. The poor men seem to be all in confusion and don’t know what to do. Why children, if you have woman’s rights give it to her and you will feel better. You will have your own rights, and they won’t be so much trouble. I can’t read, but I can hear. I have heard the Bible and have learned that Eve caused man to sin. Well if woman upset the world, do give her a chance to set it right side up again. The lady has spoken about Jesus, how he never spurned woman from him, and she was right. When Lazarus died, Mary and Martha came to him with faith and love and besought him to raise their brother. And Jesus wept—and Lazarus came forth. And how came Jesus into the world? Through God who created him and woman who bore him. Man, where is your part? But the women are coming up blessed be God and a few of the men are coming up with them. But man is in a tight place, the poor slave is on him, woman is coming on him, and he is surely between a hawk and a buzzard.

- Question How has Sojourner Truth been treated in her life? How do you know? Answer She has had a difficult life and has been treated very poorly. She states that she has worked hard in the fields and no man ever helped her. She also had most of her children sold into slavery.

- Question What was the purpose of this speech? Answer Truth was trying to persuade people that women, black or white, should be treated as equal to men. They should have rights just like men.

- Question What is the tone of this speech? Answer The tone in the beginning is of despair and sadness, with examples about working in the field and having most of her children sold into slavery. Then Truth gets angry and frustrated by stating that Christ was born of a woman and “men better let them” have rights.

- Question The following line from the speech uses the figurative language of allusion: “If the first woman God ever made was strong enough to turn the world upside down all alone, these women together ought to be able to turn it back, and get it right side up again!” What is the allusion? Why did Truth make this allusion? Answer She is referring to Eve from the Bible. Eve in the Bible was blamed for bringing sin into the world. Truth mentions this because most people in that day would have recognized the allusion and it supports her point that women are strong.

- Question What two groups does Sojourner Truth list as challenging the white man for more rights? Answer Southern blacks and Northern women

- Question In the second part of her speech, Truth refutes two of the claims made in opposition to equal rights for women and Black people. What are those claims and how does she argue against them? Answer First, Truth addresses the claim that black people and women aren’t as intelligent as white men and, therefore, are not entitled to the same rights. She argues that it’s wrong, or “mean,” to deny people their dignity even if they have fewer means. Then, she addresses the claim by some Christians that Jesus was a man and, therefore, men are superior to women. She draws on her own Christian faith and understanding of the Bible to illustrate why those claims fail in her view.

- Question Reread the speech with identity in mind after studying Identity Standard 3 of the Social Justice Standards. How do Sojourner Truth’s words illustrate the meaning of Identity Standard 3? Cite a line or section of the text that you think best reflects what Truth is expressing about identity. Answer Student answers may vary but should address the concept of intersectionality, multiple identities and the relationship of Truth’s identities as both woman and black person.

- Question In the Bugle version, the author writes, “It is impossible to transfer it to paper, or convey any adequate idea of the effect it produced upon the audience.” What is impossible to transfer to paper? The speech is in fact printed in the newspaper article supplied here. Answer It is impossible to convey the effect Sojourner Truth’s speech had on the audience. Technically, the speech wasn’t written down, so that makes it difficult to transfer as well, but that fact is not supplied in the text itself.

- Question What is the meaning behind Sojourner’s claim that “if woman have a pint and man a quart—why can’t she have her little pint full”? Answer By giving a woman a pint and a man a quart, the woman is unable to take more than the pint will hold. A woman will have only as many rights as you give her. Giving her some does not mean she will take more than she has been given.

- Student sensitivity.

- The Power of Advertising and Girls' Self-Image

Print this Text

Select the Student Version to print the text and Text Dependent Questions only. Select the Teacher Version to print the text with labels, Text Dependent Questions and answers. Highlighted vocabulary will appear in both printed versions.

- Google Classroom

Sign in to save these resources.

Login or create an account to save resources to your bookmark collection.

Learning for Justice in the South

When it comes to investing in racial justice in education, we believe that the South is the best place to start. If you’re an educator, parent or caregiver, or community member living and working in Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana or Mississippi, we’ll mail you a free introductory package of our resources when you join our community and subscribe to our magazine.

Get the Learning for Justice Newsletter

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Sojourner Truth

By: History.com Editors

Updated: February 20, 2024 | Original: October 29, 2009

Sojourner Truth was an African American evangelist, abolitionist, women’s rights activist and author who was born into slavery before escaping to freedom in 1826. After gaining her freedom, Truth preached about abolitionism and equal rights for all. She became known for a speech with the famous refrain, "Ain't I a Woman? " that she was said to have delivered at a women's convention in Ohio in 1851, although accounts of that speech (and whether Truth ever used that refrain) have since been challenged by historians. Truth continued her crusade throughout her adult life, earning an audience with President Abraham Lincoln and becoming one of the world’s best-known human rights crusaders.

Who Was Sojourner Truth?

Sojourner Truth was born Isabella Baumfree in 1797 to enslaved parents James and Elizabeth Baumfree, in Ulster County, New York . Around age nine, she was sold at an auction to John Neely for $100, along with a flock of sheep.

Neely was a cruel and violent master who beat the young girl regularly. She was sold two more times by age 13 and ultimately ended up at the West Park, New York, home of John Dumont and his second wife Elizabeth.

Around age 18, Isabella fell in love with an enslaved man named Robert from a nearby farm. But the couple was not allowed to marry since they had separate owners. Instead, Isabella was forced to marry another enslaved man owned by Dumont named Thomas. She eventually bore five children: James, Diana, Peter, Elizabeth and Sophia.

Walking from Slavery to Freedom

At the turn of the 19th century, New York started legislating emancipation, but it would take over two decades for liberation to come for all enslaved people in the state.

In the meantime, Dumont promised Isabella he’d grant her freedom on July 4, 1826, “if she would do well and be faithful.” When the date arrived, however, he had a change of heart and refused to let her go.

Incensed, Isabella completed what she felt was her obligation to Dumont and then escaped his clutches, infant daughter in tow. She later said, “I did not run off, for I thought that wicked, but I walked off, believing that to be all right.”

In what must have been a gut-wrenching choice, she left her other children behind because they were still legally bound to Dumont.

Isabella made her way to New Paltz, New York, where she and her daughter were taken in as free people by Isaac and Maria Van Wagenen. When Dumont came to reclaim his “property,” the Van Wagenens offered to buy Isabella’s services from him for $20 until the New York Anti-Slavery Law emancipating all enslaved people took effect in 1827; Dumont agreed.

Sojourner Truth, First Black Woman to Sue White Man–And Win

After the New York Anti-Slavery Law was passed, Dumont illegally sold Isabella’s five-year-old son Peter. With the help of the Van Wagenens, she filed a lawsuit to get him back.

Months later, Isabella won her case and regained custody of her son. She was the first Black woman to sue a white man in a United States court and prevail.

Sojourner Truth's Spiritual Calling

The Van Wagenens had a profound impact on Isabella’s spirituality and she became a fervent Christian. In 1829, she moved to New York City with Peter to work as a housekeeper for evangelist preacher Elijah Pierson.

She left Pierson three years later to work for another preacher, Robert Matthews. When Elijah Pierson died, Isabella and Matthews were accused of poisoning him and of theft but were eventually acquitted.

Living among people of faith only emboldened Isabella’s devoutness to Christianity and her desire to preach and win converts. In 1843, with what she believed was her religious obligation to go forth and speak the truth, she changed her name to Sojourner Truth and embarked on a journey to preach the gospel and speak out against slavery and oppression.

'Ain’t I A Woman?' Speech and Controversy

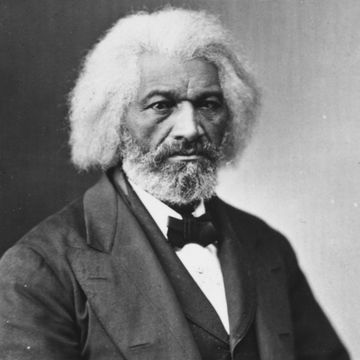

In 1844, Truth joined a Massachusetts abolitionist organization called the Northampton Association of Education and Industry, where she met leading abolitionists such as Frederick Douglass and effectively launched her career as an equal rights activist.

Among Truth's contributions to the abolitionist movement was the speech she delivered at the Ohio Women’s Rights Convention in 1851, where she spoke powerfully about equal rights for Black women. Twelve years later, Frances Gage, a white abolitionist and president of the Convention, published an account of Truth’s words in the National Anti-Slavery Standard . In her account, Gage wrote that Truth used the rhetorical question, “Ar’n’t I a Woman?” to point out the discrimination Truth experienced as a Black woman.

Various details in Gage's account, however, including that Truth said she had 13 children (she had five) and that she spoke in dialect have since cast doubt on its accuracy. Contemporaneous reports of Truth’s speech did not include this slogan and quoted Truth in standard English. In later years, this slogan was further distorted to “Ain’t I a Woman?”, reflecting the false belief that as a formerly enslaved woman, Truth would have had a Southern accent. Truth was, in fact, a proud New Yorker.

There is little doubt, nonetheless, that Truth's speech—and many others she gave throughout her adult life—moved audiences. Another account of Truth's 1851 speech, published in a newspaper about a month later, reported her saying, "I have plowed and reaped and husked and chopped and mowed, and can any man do more than that?"

Truth's powerful rhetoric won her audiences with leading women’s rights activists of her day, including Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony .

Sojourner Truth During the Civil War

Like another famous escaped enslaved woman, Harriet Tubman , Truth helped recruit Black soldiers during the Civil War . She worked in Washington, D.C. , for the National Freedman’s Relief Association and rallied people to donate food, clothes and other supplies to Black refugees.

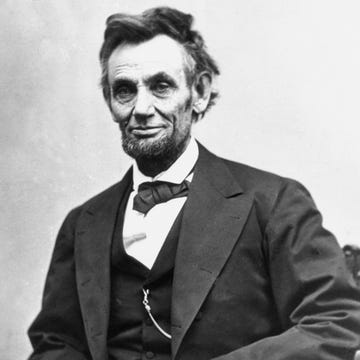

Her activism for the abolitionist movement gained the attention of President Abraham Lincoln , who invited her to the White House in October 1864 and showed her a Bible given to him by African Americans in Baltimore.

While Truth was in Washington, she put her courage and disdain for segregation on display by riding on whites-only streetcars. When the Civil War ended, she tried exhaustively to find jobs for freed Black Americans weighed down with poverty.

Later, she unsuccessfully petitioned the government to resettle formerly enslaved people on government land in the West.

Sojourner Truth Quotes

“If the first woman God ever made was strong enough to turn the world upside down all alone, these women together ought to be able to turn it back, and get it right side up again! And now they is asking to do it, the men better let them.”

“Then that little man in Black there, he says women can't have as much rights as men, 'cause Christ wasn't a woman! Where did your Christ come from? Where did Christ come from? From God and a woman! Man had nothing to do with Him.”

And what is that religion that sanctions, even by its silence, all that is embraced in the 'Peculiar Institution'? If there can be any thing more diametrically opposed to the religion of Jesus, than the working of this soul-killing system - which is as truly sanctioned by the religion of America as are her ministers and churches—we wish to be shown where it can be found.”

“Now, if you want me to get out of the world, you had better get the women votin' soon. I shan't go till I can do that.”

Sojourner Truth’s Later Years

In 1867, Truth moved to Battle Creek, Michigan , where some of her daughters lived. She continued to speak out against discrimination and in favor of woman’s suffrage . She was especially concerned that some civil rights leaders such as Frederick Douglass felt equal rights for Black men took precedence over those of Black women.

Truth died at home on November 26, 1883. Records show she was age 86, yet her memorial tombstone states she was 105. Engraved on her tombstone are the words, “Is God Dead?” a question she once asked a despondent Frederick Douglass to remind him to have faith.

Truth left behind a legacy of courage, faith and fighting for what’s right and honorable, but she also left a legacy of words and songs including her autobiography, The Narrative of Sojourner Truth , which she dictated in 1850 to Olive Gilbert since she never learned to read or write.

Perhaps Truth’s life of Christianity and fighting for equality is best summed up by her own words in 1863: “Children, who made your skin white? Was it not God? Who made mine Black? Was it not the same God? Am I to blame, therefore, because my skin is Black? …. Does not God love colored children as well as white children? And did not the same Savior die to save the one as well as the other?”

Sojourner Truth: Ain’t I A Woman? National Park Service.

Sojourner Truth: A Life of Legacy and Faith. Sojourner Truth Institute.

Sojourner Truth Meets Abraham Lincoln—On Equal Ground. Biography.

Sojourner Truth. National Park Service.

Sojourner Truth. WHMN: National Women’s History Museum.

Sojourner’s Words and Music. Sojourner Truth Memorial Committee.

Truth, Sojourner. American National Biography.

HISTORY Vault: Women's History

Stream acclaimed women's history documentaries in HISTORY Vault.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

The Real History of Sojourner Truth’s “Ain’t I a Woman” Speech

By ellen gutoskey | may 3, 2024.

Content Warning: This article includes the text of speeches that use outdated and offensive language and reflect stereotypes of Black Americans from the Civil War era.

In late May of 1851, activists assembled in a church in Akron, Ohio, for the Woman’s Rights Convention . The two-day event was a success, so crowded that standing room was hard to find. There were prayers, songs, coverage of topics like the state of women’s labor in America, and many a rousing address—among them one by Sojourner Truth that would come to be known as the “Ain’t I a Woman” speech.

The most famous account of the speech has shaped our conception of the circumstances surrounding Truth’s delivery of it and even of Truth herself. But it wasn’t printed until 1863, and earlier reporting on the convention—including another version of the speech published just weeks after the fact—tells a remarkably different story. In that version, the line “Ain’t I a woman?” doesn’t appear at all.

So which story should we trust?

The Flaws of Frances D. Gage

Frances d. gage’s original text of sojourner truth’s speech, what marius robinson got right, marius robinson’s original text of sojourner truth’s speech, the woman, the myth, the legend.

In spring 1863, The Atlantic published a feature on Sojourner Truth written by Harriet Beecher Stowe , which inspired activist Frances D. Gage to put her own memories of the abolitionist in print. Gage had been the president of the 1851 Woman’s Rights Convention in Akron, and so those memories revolved around Truth’s role in the event.

Gage’s personal essay, published in New York City’s weekly Independent and a handful of other papers that spring, alleged that women’s rights leaders circa 1851 were “staggering under the weight” of disapproval for the movement and wary of anything that could exacerbate the tension. According to Gage, many convention attendees were “almost thrown into panics” when Truth, a Black abolitionist, appeared on the first day, the implication being that linking feminist causes with abolition would spell doom for the former.

The second day was purportedly characterized by “long-winded bombast” from dissenters, “sneerers among the pews,” and an atmosphere that “betokened a storm.” As Truth rose to address the assembly, several people implored Gage to stop her, and “a hissing sound of disapprobation” echoed through the room. Truth then quelled the tension by delivering in “deep wonderful tones” a speech that elicited “roars of applause” and left “more than one of us with streaming eyes beating with gratitude.”

There is ample evidence to suggest that Gage may have exaggerated elements of this story for the sake of a compelling narrative. For one thing, none of more than two dozen contemporary accounts of the convention really corroborates it. Speaker Emma R. Coe described the event’s “spirit of harmony” with not “one discordant note,” and Cleveland’s Herald remarked on the lack of any “sly leer” or “half uttered jest” that readers might picture, especially given that men made up almost half the crowd. Even Gage contradicted herself: While speaking at a national women’s rights convention in 1853, she mentioned that “no one has had a word to say against us” at past conventions, Akron included.

It’s also worth noting that most women’s rights activists supported abolition , and the Akron convention had been publicized in abolitionist newspapers. Not to mention that Black abolitionists—including Truth and Frederick Douglass —had attended and occasionally spoken at previous women’s rights conventions. In short, it couldn’t have been much of a surprise or a scandal that Truth showed up to this one.

As for her treatment in Akron, it’s not hard to believe that white members may have afforded her, a formerly enslaved Black woman who couldn’t read or write, less warmth and enthusiasm than they did each other. Convention co-secretary Hannah Tracy later wrote that she “fear[ed] we did not feel ready to give her as royal a welcome as her merits deserved.” If Truth perceived anything from mild discomfort to outright enmity, though, she didn’t commit it to writing (that we know of). In fact, she expressed in a dictated letter to fellow abolitionist Amy Post that she “found plenty of kind friends, just like you, & they gave me so many kind invitations I hardly knew which to accept first.”

All that said, the most glaring sign that Gage embellished her account is the speech itself. She wrote it in a dialect associated with Black enslaved people in the South, and Truth had only ever lived in the North; she was born to enslaved parents in Ulster County, New York, and exclusively spoke Dutch for the first nine years of her life. If she had an accent, it was a far cry from the one Gage affected for her, and one widely circulated obituary described her diction as “grammatically correct” and her pronunciation “faultless.”

While there’s nothing incorrect about any way Black Southerners spoke English—an ever-evolving language with many dialects—Gage collapsed all Black Americans into a stereotype by giving Truth a dialect she herself didn’t use. The text is offensive to read, but it’s vital in understanding the extent of Gage’s fabrication.

“ ‘Well, chillen, whar dar’s so much racket dar must be som’ting out o’ kilter. I tink dat, ’twixt de n******s of de South and de women at de Norf, all a-talking ’bout rights, de white men will be in a fix pretty soon. But what’s all this here takling ’bout? Dat man ober dar say dat woman needs to be helped into carriages, and lifted over ditches, and to have de best places eberywhar. Nobody eber helps me into carriages, or ober mud-puddles, or gives me any best place‘; and, raising herself to her full height, and her voice to a pitch like rolling thunder, she asked, ‘And ar’n’t I a woman? Look at me. Look at my arm,’ and she bared her right arm to the shoulder, showing its tremendous muscular power. ‘I have plowed and planted and gathered into barns, and no man could head me—and ar’n’t I a woman? I could work as much and eat as much as a man (when I could get it), and bear de lash as well—and ar’n’t I a woman? I have borne thirteen chillen, and seen ’em mos’ all sold off into slavery, and when I cried out with a mother’s grief, none but Jesus heard—and ar’n’t I a woman? Den dey talks ’bout dis ting in de head. What dis dey call it?‘ ‘Intellect,’ whispered some one near. ‘Dat’s it, honey. What’s dat got to do with woman’s rights or n*****s’ rights? If my cup won’t hold but a pint and yourn holds a quart wouldn’t ye be mean not to let me have my little half-measure full?’ and she pointed her significant finger and sent a keen glance at the minister who had made the argument. The cheering was long and loud. ‘Den dat little man in black dar, he say woman can’t have as much right as man ’cause Christ wa’n’nt a woman. Whar did your Christ come from? ’

“Rolling thunder could not have stilled that crowd as did those deep, wonderful tones, as she stood there with outstretched arms and eye of fire. Raising her voice still louder, she repeated—

‘Whar did your Christ come from? From God and a woman. Man had not’ing to do with him.’ Oh! what a rebuke she gave the little man. Turning again to another objector, she took up the defence of Mother Eve. I cannot follow her through it all. It was pointed and witty and solemn, eliciting at almost every sentence deafening applause; and she ended by asserting ‘that if de fust woman God ever made was strong enough to turn de world upside down all her one lone, all dese together,’ and she glanced her eye over us, ‘ought to be able to turn it back and git it right side up again, and now dey is asking to, de men better let ’em’ (long continued cheering). ‘Bleeged to ye for hearin’ on me, and now ole Sojourner ha’n’t got nothin’ more to say.’ ”

There’s one detail in here that doesn’t match the historical record. Gage has Truth saying that she bore 13 children and saw most of them sold into slavery, but scholars generally agree that she was likely a mother of five, one of whom was sold into slavery.

If this were the only attempt at reproducing Truth’s speech, we’d have no way of knowing how much of it Truth actually uttered. Fortunately, it wasn’t.

In spring 1851, married abolitionists Marius and Emily Robinson of Salem, Ohio—a few dozen miles from Akron— welcomed Truth as a houseguest. Both Robinsons participated in the Akron convention, Emily as a speaker and Marius as the recording secretary .

Marius was an editor of the Anti-Slavery Bugle , where he published his transcription of Truth’s speech on June 21, 1851. There is some overlap between his and Gage’s versions. In both, Truth declares herself equal to any man in terms of strength, appetite, and ability to work. She asks why women would be denied their pint of intellect by men who boast a quart; and she mentions that man had no part in the creation of Jesus Christ, who came from God and a woman. Truth also proposes that if God’s first woman was responsible for upsetting the order of the world, women should get a chance to right it.

A couple brief summaries of the speech in other newspapers back up these points and also lend credence to one detail from Gage’s version that Marius didn’t jot down—that Truth elicited laughter from listeners. No report, however, contains a single reference to Gage’s “Ar’n’t I a woman?” (which is most commonly rendered today as “Ain’t I a woman?”).

It’s not completely out of the question that Marius accidentally missed a line; he did say in his report that “It is impossible to transfer [the speech] to paper, or convey any adequate idea of the effect it produced upon the audience. Those only can appreciate it who saw her powerful form, her whole-souled, earnest gesture, and listened to her strong and truthful tones.”

But it is hard to believe that he would have missed “Ar’n’t I a woman?”. Not only was it his job to take notes, but scholars even think it likely that he ran those notes by Truth herself before printing them. Moreover, Gage has Truth saying “Ar’n’t I a woman?” four times.

“Had Truth said it several times in 1851, as in Gage’s article, Marius Robinson, who was familiar with Truth’s diction, most certainly would have noted it,” Nell Irvin Painter wrote in Sojourner Truth: A Life, a Symbol . “If he had an unusually tin ear, he might have missed it once, perhaps even twice. But not four times, as in Gage’s report.”

“ ‘May I say a few words?’ Receiving an affirmative answer, she proceeded; ‘I want to say a few words about this matter. I am a woman’s rights. I have as much muscle as any man, and can do as much work as any man. I have plowed and reaped and husked and chopped and mowed, and can any man do more than that? I have heard much about the sexes being equal; I can carry as much as any man, and can eat as much too, if I can get it. I am as strong as any man that is now. As for intellect, all I can say is, if woman have a pint and man a quart—why cant she have her little pint full? You need not be afraid to give us our rights for fear we will take too much,—for we cant take more than our pint’ll hold. The poor men seem to be all in confusion, and dont know what to do. Why children, if you have woman’s rights give it to her and you will feel better. You will have your own rights, and they wont be so much trouble. I cant read, but I can hear. I have heard the bible and have learned that Eve caused man to sin. Well if woman upset the world, do give her a chance to set it right side up again. The Lady has spoken about Jesus, how he never spurned woman from him, and she was right. When Lazarus died, Mary and Martha came to him with faith and love and besought him to raise their brother. And Jesus wept—and Lazarus came forth. And how came Jesus into the world? Through God who created him and woman who bore him. Man, where is your part? But the women are coming up blessed be God and a few of the men are coming up with them. But man is in a tight place, the poor slave is on him, woman is coming on him, and he is surely between a hawk and a buzzard.‘ ’

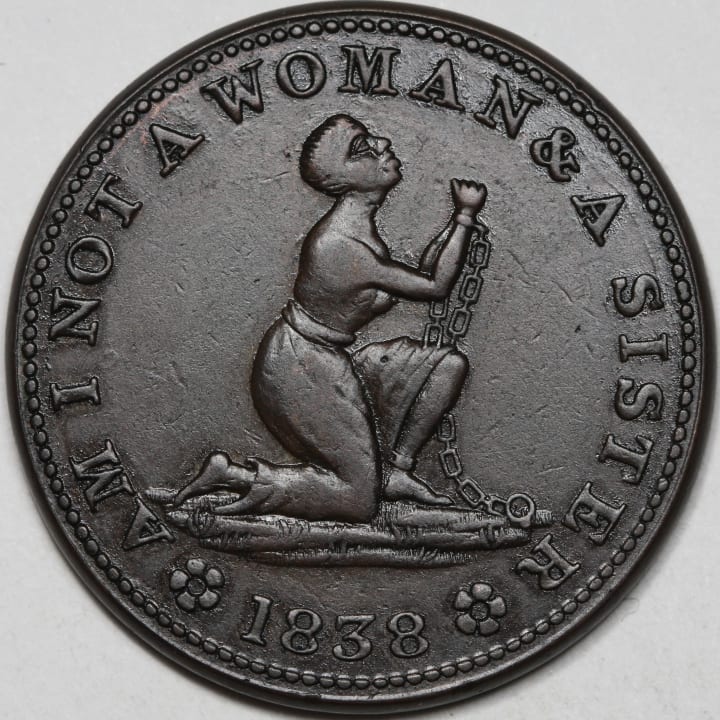

In the end, we can’t even really give Gage credit for making up a great line, misattributed though it (probably) was. As Carleton Mabee and Susan Mabee Newhouse pointed out in Sojourner Truth: Slave, Prophet, Legend , “Ar’n’t I a woman” was “undoubtedly an adaptation of the motto, ‘Am I not a Woman and a Sister?’, which had for many years been a popular antislavery motto.” That itself was a riff on “Am I not a Man and a Brother?”, a mantra of 18th-century British abolitionists.

For what it’s worth, Gage did write that her transcription was “but a faint sketch” of Truth’s oration. But that doesn’t make it clear that she filled in the blanks with her own flair—and when Gage’s version was reprinted in two seminal books, an 1875 edition of Narrative of Sojourner Truth and 1881’s History of Woman Suffrage, Volume 1 , neither even included the disclaimer.

It’s especially interesting that Gage’s version is featured in Narrative , as Truth herself dictated the original 1850 edition and remained involved in the follow-ups. But she was evidently aware that in published reports of her life, the mythos of Sojourner Truth had begun to eclipse the facts: At an 1871 lecture in Syracuse, New York, she reportedly said that her life story “had growed and growed, and now it was a great book, and there wasn’t a word of truth in it, and what there was that was true was all hind side afore.”

With that in mind, it doesn’t seem so surprising that Truth never set the record straight on the exact syntax of one speech that she had given many years ago and maybe didn’t even remember word for word. That’s not to diminish the importance of preserving her speech as accurately as we can—and plenty of modern sources have platformed Marius Robinson’s version alongside Gage’s to give readers the whole story. The fact that it’s still widely called the “Ain’t I a Woman?” speech, though, is something we might just have to live with.

Learn About Other Famous Speeches:

Sojourner Truth’s “Ain’t I a Woman” Speech May Not Have Contained That Famous Phrase

Or says a transcript of the speech that was published 12 years later.

Fellow abolitionist Frances Gage published Truth’s speech in the New York Independent in 1863, but little of it lines up with the transcript published a month after the convention by Reverend Marius Robinson in Anti-Slavery Bugle in 1851.

To this day, the accuracy of both transcripts is constantly being debated, with the two versions being pitted against each other side by side by experts, including the Sojourner Truth Project .

But one thing’s for certain: Whatever her syntax that day, the words Truth spoke were powerful and will forever be remembered as one of the greatest speeches of the women’s abolitionist movement.

Born into slavery, Truth was sold a few times as a child

Truth was born Isabella Baumfree around 1797 (records of the enslaved children’s births weren’t kept), in Swartekill, New York, to an enslaved father, James, who was captured in Ghana and a mother, Elizabeth, who was the daughter of enslaved people from Guinea.

Owned by Colonel Hardenbergh in Esopus, New York, which was under Dutch control, Truth grew up speaking Dutch. After both the colonel and his son died, Truth was sold off along with a flock of sheep for $100. Also known as Belle, the nine-year-old was eventually sold a couple more times and came to learn English under her owner John Dumont who lived in West Park, New York.

Reportedly “inspired by her conversations with God, which she held alone in the woods,” Truth escaped to freedom in 1826 with her young daughter, Sophia. While Dumont accused her of running away, she stated boldly , “I did not run away, I walked away by daylight.”

She changed her name to Sojourner Truth after a 'religious conversation'

By 1828, Truth had settled in New York City and became a preacher. She started speaking out about her experience as an enslaved person and advocating for abolitionism and feminism, while quickly gaining a reputation as a powerful speaker.

But it wasn’t until 1843 when she had a “ religious conversion ” and was “ called in spirit ” to “travel up and down the land” as a lecturer that she adopted the name Sojourner Truth. In 1844, she joined Northampton Association of Education and Industry, which also included William Lloyd Garrison and Frederick Douglass . Truth continued speaking wherever she went — and also selling her book The Narrative of Sojourner Truth — winning over audiences with her artful persuasion.

In 1850, by the time she stepped up to the podium at the first National Women’s Rights Convention in Worcester, Massachusetts she was already one of the most influential voices of the movement.

There are several accounts of what Truth said in her speech

The following year, the Women’s Rights Convention moved to Akron on May 29, 1851. “Everything seemed to go wrong with the meeting,” according to the New Republic . “A number of ministers had invaded the hall uninvited and monopolized the discussion, quoting biblical texts to the effect that women should eschew all activities except those of child-bearing, homemaking and subservience to their husbands.”

Taking place at High Street’s Old Stone Church, the gifted speaker didn’t outrightly prepare anything. But when she heard these comments, she couldn’t sit still. Truth stepped up and spoke out extemporaneously, or as the New Republic says, “Suddenly she boomed out of the hushed audience.”

And the words she said are now what’s so hotly debated by historians, even today.

The version that was printed by Robinson a month later , starts out, “May I say a few words? I want to say a few words about this matter. I am a woman’s rights.”

That final sentence is as close as it gets to the phrasing “Ain’t I a Woman,” which we know the speech as today.

In the second version — printed a dozen years later — “Ain’t I a Woman” is used four times, and even detailed by some historians as "Ar'n't I a woman?”

The newer version weaves the phrase throughout poetically, showing the hardships women face.

The iconic section reads: “That man over there says that women need to be helped into carriages, and lifted over ditches, and to have the best place everywhere. Nobody ever helps me into carriages, or over mud-puddles, or gives me any best place! And ain't I a woman? Look at me! Look at my arm! I have ploughed and planted, and gathered into barns, and no man could head me! And ain't I a woman? I could work as much and eat as much as a man — when I could get it — and bear the lash as well! And ain't I a woman? I have borne thirteen children, and seen most all sold off to slavery, and when I cried out with my mother's grief, none but Jesus heard me! And ain't I a woman?”

While there are similarities in essence, the disputed transcripts hardly line up, making the debate over accuracy still rage today.

Some researchers point to the fact that some of the statements in Gage’s version simply aren’t true. For instance, Truth only had five children — not 13 — an inaccuracy that immediately pokes holes in the later version.

That said, Gage herself was a poet and may have taken artistic license to embellish and emphasize the statements — or perhaps she simply meant them to be a fictionalized representation the plight of all women.

The dialect differences between the two versions also raise potential issues, with some saying the latter captures Truth’s Afro-Dutch dialect more accurately.

Modern interpretations favor Gage's version

Many readings of Truth’s famous speech have been recorded, including some by notable actresses like Kerry Washington and Alfre Woodward , as well The Color Purple author Alice Walker . All three readings follow the latter transcript containing the “Ain’t I a Woman” phrasing — with audiences laughing knowingly throughout the speech.

Whether or not those words were used, Truth’s sentiment was considered extreme at the time as she advocated for political equality for all women. And more than a century since her speech, Truth's words continue to resonate with generations, being taught in schools and "Ain't I a Woman" emblazoned on t-shirts, posters, pins and more.

Truth continued speaking throughout the rest of her life, advocating for women’s rights, equality and suffrage — until her death in Battle Creek, Michigan in 1883.

Watch Next .css-smpm16:after{background-color:#323232;color:#fff;margin-left:1.8rem;margin-top:1.25rem;width:1.5rem;height:0.063rem;content:'';display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;}

Abolitionists

Harriet Tubman

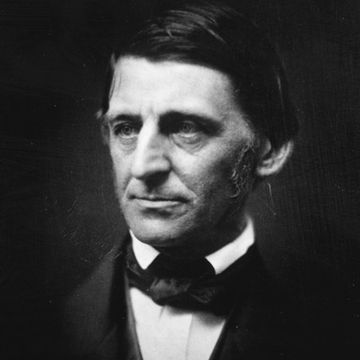

Ralph Waldo Emerson

Abraham Lincoln

Susan B. Anthony

Lucretia Mott

Harriet Beecher Stowe

Frederick Douglass

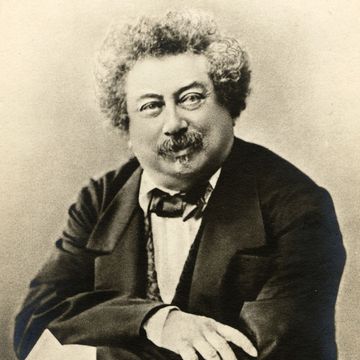

Alexandre Dumas

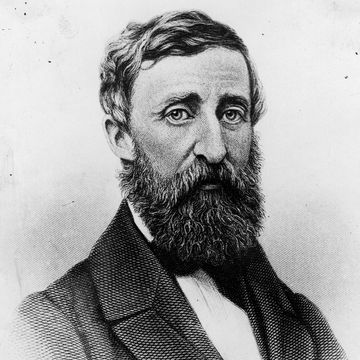

Henry David Thoreau

Mary Ann Shadd Cary

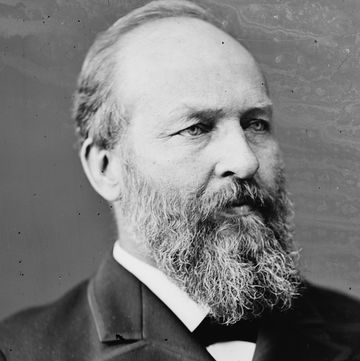

James Garfield

Ain’t I a Woman?

Sojourner truth, ask litcharts ai: the answer to your questions.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Read the full text of Sojourner Truth's 1851 speech on women's rights, delivered without preparation. Learn about her arguments, biblical references, and rhetorical questions.

Read the full text of Sojourner Truth's powerful speech delivered at the Women's Convention in Akron, Ohio in 1851. She challenged the audience with her experiences as a black woman and a mother, and demanded equal rights for women and slaves.

Sojourner Truth "Ain't I a Woman?" is a speech, generally considered to have been delivered extemporaneously, by Sojourner Truth (1797-1883), born into slavery in the state of New York.Some time after gaining her freedom in 1827, she became a well known anti-slavery speaker. Her speech was delivered at the Women's Convention in Akron, Ohio, in 1851, and did not originally have a title.

Learn about the life and legacy of Sojourner Truth, a former slave and women's rights activist who delivered a powerful speech in 1851. Read the text of her speech and compare different versions of it.

Read the full text of Sojourner Truth's powerful speech from 1851, where she challenged the audience to recognize her rights as a woman and a human being. She used humor, logic, and biblical references to argue for women's and African Americans' equality.

Learn about the famous speech that Sojourner Truth gave at the Ohio Women's Rights Convention in 1851, asserting her right to equality as a woman and a Black American. Find out the origin and controversy of the phrase "Ain't I a Woman?" and how Truth challenged racism and sexism.

Sojourner Truth (1797-1883) "Ain't I A Woman?" Delivered at the 1851 Women's Convention, Akron, Ohio Well, children, where there is so much racket there must be something out of kilter. I think that 'twixt the negroes of the South and the women at the North, all talking about rights, the white men will be in a fix pretty soon.