The Straits Times

- International

- Print Edition

- news with benefits

- SPH Rewards

- STClassifieds

- Berita Harian

- Hardwarezone

- Shin Min Daily News

- Tamil Murasu

- The Business Times

- The New Paper

- Lianhe Zaobao

- Advertise with us

Full speech: Five core principles of Singapore's foreign policy

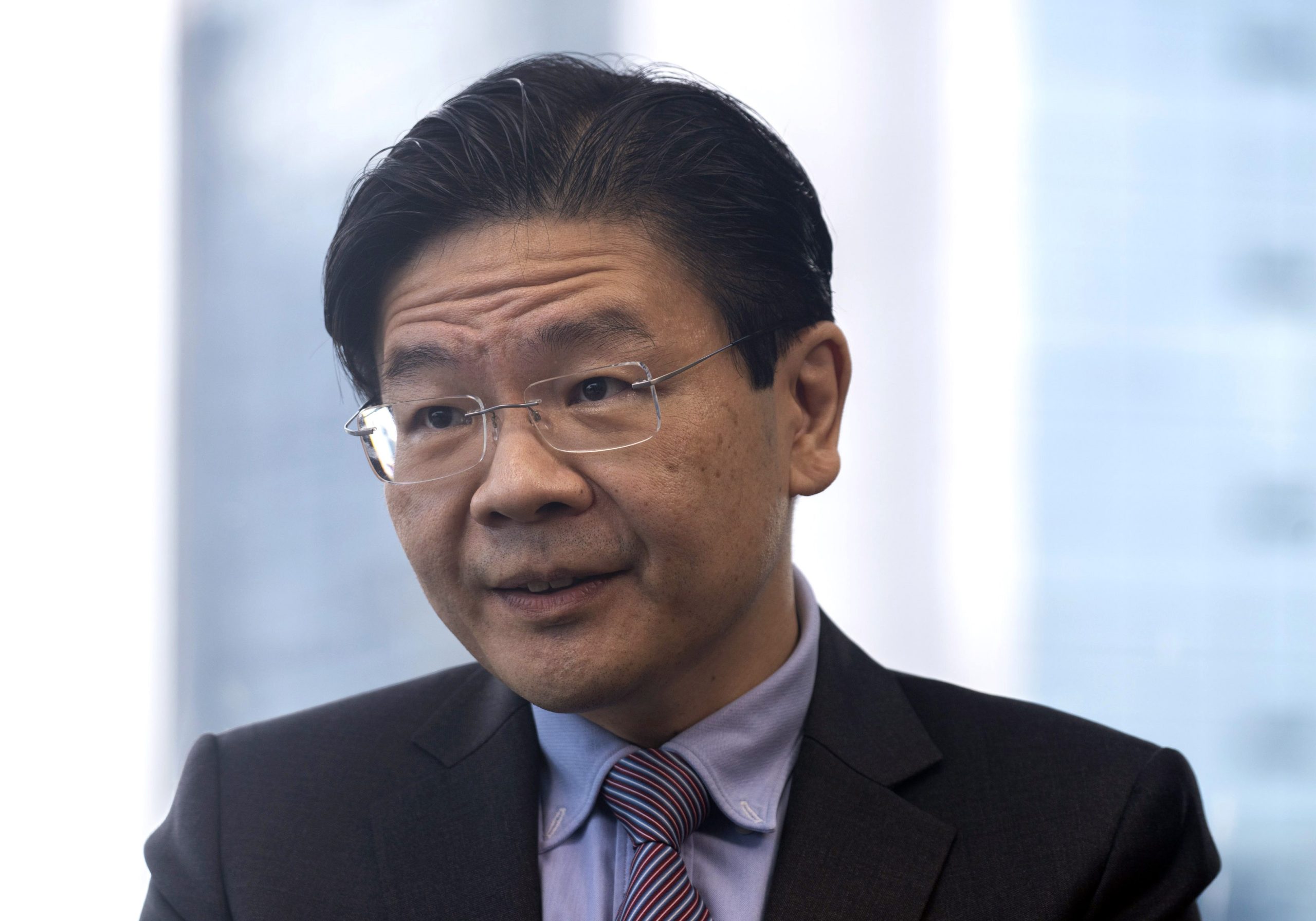

Minister for Foreign Affairs Vivian Balakrishnan on Monday (July 17) spoke to 200 civil servants about the core principles of Singapore's foreign policy, in light of a recent debate on the matter concerning Singapore's status as a small state and its posture given changing geopolitics. This is the full text of his remarks.

Let me start by saying it is not by coincidence that today we are at peace, we are at peace with all our neighbours, and we have good relations with all the major powers of the world. We owe a debt of gratitude to all our leaders and diplomats, both present and the past, for this happy state of affairs.

But more recently there has been lively debate on Singapore's foreign policy, and I think this debate is especially on the part by retired officials, academics and commentators. But there is one key difference for all the people in the room here tonight. The key difference is that we are serving members of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA), and we in this room have line responsibility for the actual conduct of foreign policy on a daily basis. What this means is that the deliberations today are not a theoretical debate, and this not an academic word spinning exercise on a lecture circuit.

Some questions that have been raised include the following: First, has Singapore overreached? Have we forgotten our permanent status as a small state in the large dangerous world and tough region? Next question, should Singapore adjust our foreign policy posture given the evolving geopolitical situation, or even because of leadership changes in Singapore? And the third question has been, has our insistence on a consistent and principled approach actually limited our flexibility, our ability to adapt to new circumstances?

These are valid questions but I believe we need to go back to first principles. The ultimate objectives for our foreign policy are first, protect our independence and sovereignty, and second, to expand opportunities for our citizens to overcome our geographic limits. These are our ultimate objectives. It's easy to state them, difficult to achieve. The existential challenge is how do we achieve these ultimate objectives, given our circumstances that we will always be a tiny city state in South East Asia and with a multi-racial population.

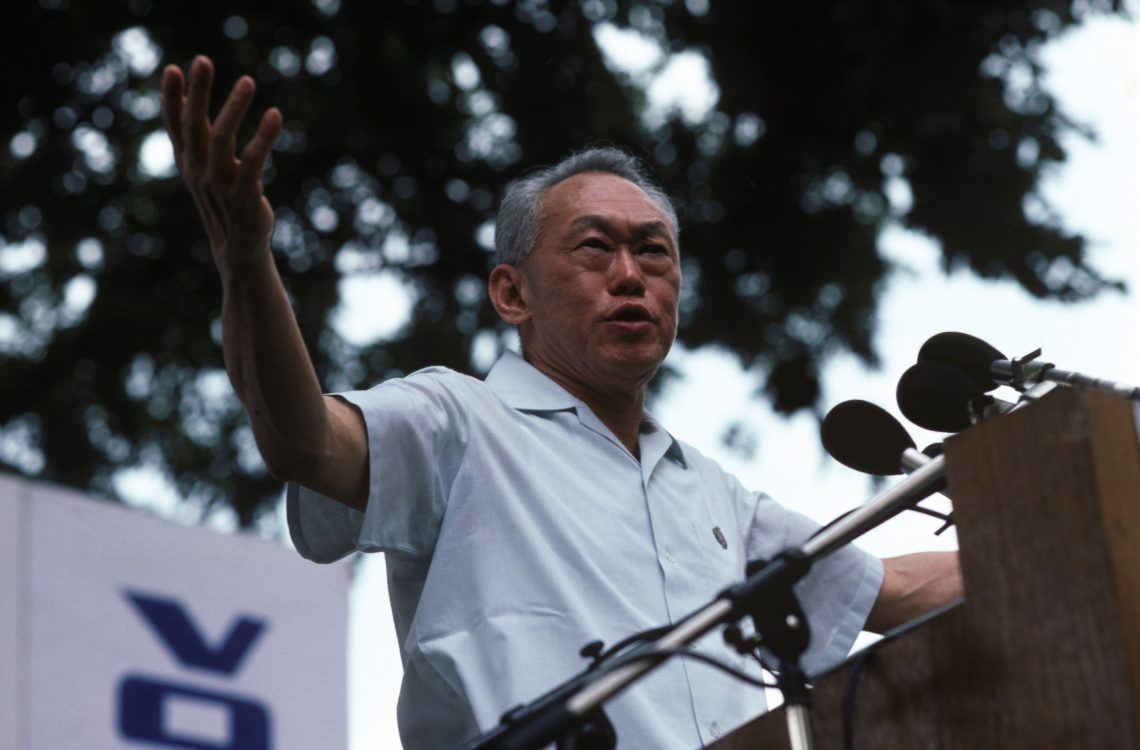

We must not harbour any illusions about our place in the world. History is replete with examples of failed small states. Our founding Prime Minister Mr Lee Kuan Yew always reminded us repeatedly that we have to take the world as it is, and not as we wish it to be. But that does not mean that Mr Lee advocated a 'do nothing, say nothing' posture, or that Singapore should simply surrender to our fates. As Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong has recently reminded us, on issues where our national interests are at stake, we must be prepared to 'stand up and be counted'.

Some people have suggested that Singapore lay low and "suffer what we must" as a small state. On the contrary, it is precisely because we are a small state that we have to stand up and be counted when we need to do so. There is no contradiction

between a realistic appreciation of realpolitik and doing whatever it takes to protect our sovereignty, maintain and expand our relevance, and to create political and economic space for ourselves. The founding fathers of our foreign policy - Mr Lee Kuan Yew, Mr S Rajaratnam, and Dr Goh Keng Swee, and their team - understood this acutely and they formulated a few core foreign policy principles. These principles have served us well since independence but are still worth reviewing again.

CORE PRINCIPLES

What are these principles? First, Singapore needs to be a successful and vibrant economy. We need to have stable politics and we need a united society. If you think about it, if we were not successful, if we were not united and if we were not stable, we would be completely irrelevant. All of us in this room have witnessed how delegations of less successful small states are ignored at international meetings. And I am always mindful that foreigners do not speak to us because of the eloquence of our presentations or because we have the highest EQ in the room. We only merit attention because everyone knows that we come from Singapore and Singapore has made a success of itself despite our size, and that we are represented by smart, honest, serious and constructive diplomats.

Second principle- we must not become a vassal state. What this means is that we cannot be bought nor can we be bullied. And it means we must be prepared to defend our territory, our assets and our way of life. This is why we just celebrated 50 years of National Service, and we maintain at great effort a Singapore Armed Forces (SAF) that everybody takes seriously. This does not just depend on the military technology that the SAF possesses, but on the courage and resolve of our soldiers, particularly NS men, to defend what we have and to fight for what we hold dear.

Third, we aim to be a friend to all, but an enemy of none. This is especially so for our immediate neighbourhood where peace and stability in Southeast Asia are absolutely essential. Consequently, Singapore was a founding member of ASEAN and we remain a strong advocate of ASEAN unity and centrality. With the superpowers and other regional powers, our aim is to expand our relationships, both politically and economically, so that we will be relevant to them and they will find our success in their own interest. This delicate balancing act is easier in good and peaceful times, but obviously more difficult when superpowers and regional powers contend with one another. Nevertheless, our basic reflex must be and should be to aim for balance and to promote an inclusive architecture. And we must avoid taking sides, siding with one side against another. While we spare no effort to develop a wide network of relations, these relations must be based on mutual respect for each other's sovereignty and the equality of nation states, regardless of size. Diplomacy is not just about having "friendly" relations at all costs. It is about promoting friendly relations as a way to protect and advance our own important interests. We don't compromise our national interests in order to have good relations. The order matters. So when others make unreasonable demands that hurt or compromise our national interests, we need to state our position and stand our ground in a firm and principled manner.

Fourth, we must promote a global world order governed by the rule of law and international norms. In a system where "might is right" or the laws of the jungle prevail, small states like us have very little chance of survival. Instead, a more promising system for small states, and frankly even a better system overall for the comity of nations, is one that upholds the rights and sovereignty of all states and the rule of law. Bigger powers will still have more influence and say, but bigger powers do not get a free pass to do as they please. In exchange, they benefit from an orderly global environment, and do not have to resort to force or arms in order to get their way.

This is why Singapore has always participated actively at the United Nations, and in the formulation of international regimes and norms. We were a key player in the negotiations for the Law of the Sea Treaty (UNCLOS) in 1982. Professor Tommy Koh still remains with us. And I'm sure that is one of your proudest achievements of your diplomatic career. We play an outsized role at the WTO, and in negotiating a web of free trade agreements at a bilateral and multilateral level. As a country where trade is 3.5 times our GDP, we must stand up for the multilateral, global trading system. And as a port at the narrow straits that ultimately connect the Pacific Ocean to the Indian Ocean, freedom of navigation according to UNCLOS is absolutely critical to us.

More recently, we participated actively in the negotiations for the Global Agreement on Climate Change. I spent five years, several of them as a Ministerial facilitator, for what ultimately resulted in the Paris Agreement. And we did so because we are especially susceptible to climate change as a low-lying island city state. So Singapore must support a rules-based global community, promote the rule of international law and the peaceful resolution of disputes. These are fundamental priorities. They reflect our vital interests, and they affect our position in the world. We must stand up on these issues, and speak with conviction, so that people know our position. And we must actively counter the tactics of other powers who may try to influence our domestic constituencies in order to make our foreign policy better suit their interests.

Ultimately, we must be clear-minded about Singapore's long-term interests, and have the gumption to make our foreign policy decisions accordingly. During the Peloponnesian War, the Athenians were warned of the consequences they would suffer were they to give in to initial Spartan demands. Greek statesman Pericles told his fellow Athenians that if they were frightened into obedience by the initial demands of the Spartans in order to avoid war, then they would instantly have to meet a greater demand. Actually, contained in the Spartans' demand was actually a test of the Athenians' resolve. And if they give in once, they would have to give in again, and ultimately they would be enslaved. On the other hand, a firm refusal would make the Spartans clearly understand that they must treat the Athenians more as equals.

Now I know we live in a very different era and different geopolitical situation, but this lesson, this warning against appeasement remains instructive for Singapore. Whether we are dealing with a key security and economic partner or a large neighbour, Singapore has always stood firm when it comes to our own vital national interests, particularly where it impacts on sovereignty, security and the rule of law.

When the US teenager Michael Fay was sentenced to caning for vandalism, back in 1994, we upheld our court's decision, even under great pressure from the US. In 1968, to take an example further back in our history, we proceeded to hang two Indonesian marines for the bombing of MacDonald House during Konfrontasi. I want all of you to bear in mind the political and strategic circumstances in 1968. We had just been kicked out of Malaysia. The British had just announced their intention to withdraw their forces from Singapore. We were still fighting a communist insurgency. Can you imagine the guts it took for the leaders in 1968, facing such circumstances, to stand up and do the right thing?

These episodes, painful though they may be, established clear red-lines and boundaries. The message was clear: Singapore may be small, but upholding our laws and safeguarding our independence, our citizens' safety and security was of overriding importance. So we cannot afford to ever be intimidated into acquiescence. And the fact that we have consistently demonstrated this in action, put our relationships with neighbours near and far, other states big and large, on a more solid and actually stable footing.

And this is why we speak up whenever basic principles are challenged. When Russian troops took control of Crimea, Singapore strongly objected to the invasion. We expressed our view that the sovereignty and territorial integrity of the Ukraine, and international law, had to be respected.

Which brings me to my fifth principle - that we must be a credible and consistent partner. Our views are taken seriously because countries know that we always take a long term constructive view of the issues. The bigger countries engage Singapore because we do not just tell them what they want to hear. In fact, they try harder to make Singapore take their side precisely because they know that our words mean something. We are honest brokers. We deal fairly and openly with all parties. And there is a sense of strategic predictability, which has enabled Singapore to build up trust and goodwill with our partners over the decades.

And because we are credible, Singapore has been able to play a constructive role in international affairs, at ASEAN and at the UN. We have helped to create platforms for countries with similar interests. For example, in 1992, Singapore helped establish the Forum of Small States. As a group, we've been able to foster common positions and to have a bigger voice at the United Nations. And today, the Forum of Small States has grown to 107 countries, more than half the membership of the UN.

We play a constructive role in the Alliance of Small Island States (AOSIS). We also launched the Global Governance Group (3G), to ensure that the voices of small states are heard, and to serve as a bridge between the G20 and the larger UN membership. Our credibility has won us a seat at the table, even when our relevance is not immediately obvious. We are not the the 20th largest economy in the world, but yet we've just come back from the G20, where we got invited.

You want to take another example even further afield? When we first expressed interest in the Arctic Council, there were many who wondered what role a small equatorial country would play on Arctic matters. But rising sea levels and possibility of new shipping routes impact or potentially impact our position as a transhipment hub, and so it is useful for us to be on the Arctic Council. We have gained observer status in the Arctic Council since May 2013. And we participate actively and contribute our expertise on maritime affairs. And if anyone wants deeper insights into this, speak to MOS Sam Tan who has represented us resolutely and repeatedly on the Arctic Council.

LOOKING BEYOND

Now let's look beyond these five principles. Let me make a few observations. Small states are inconsequential unless we are able to offer a value proposition and make ourselves relevant. Singapore's economic success, our political stability and our social harmony and unity has attracted attention from others to do business with us, and to examine our developmental model. And this is why our diplomats, both those of you in this room as well as the other half of our family overseas, work so hard all over the world to find common ground and to make common cause with other states. And we search for win-win outcomes based on the principles of interdependence. For example, we have participated in major cooperation projects in Suzhou, Tianjin and Chongqing in China, Amaravati in India, Iskandar Malaysia in Johor, the Kendal Industrial Park in Semarang, Indonesia, and the multiple Vietnam-Singapore Industrial Parks. When we embarked on these projects, we contribute novel ideas and we implement our plans on a whole of government basis. And what this means is not just MFA, but our colleagues in all the other Ministries who also contribute whole heartedly into these projects.

Singapore's position today is far more secure than it was at our birth in 1965. But the challenges of small states will be perennial. They cannot be ignored, or wished away. A strong and credible SAF is an important deterrence and foreign policy begins at home. Our diplomacy is only credible, if we are able to maintain a domestic consensus on Singapore's core interests and our foreign policy priorities. And if our politics does not become fractious, or our society divided. We have safeguarded our international position by building a successful economy and a cohesive society; making clear that we always act in Singapore's interests, and not at the behest or the bidding of other states. We have been expanding our relationships with as many countries as possible, on the basis of mutual respect for all states regardless of size and on a win-win interdependence. Upholding international law has been a matter of fundamental principle for us; and being a credible and consistent partner with a long term view has given us a role to play and relevance on the international stage.

Colleagues, geopolitics will become more uncertain and unpredictable. But we need to ensure that our foreign policy positions reflect the changing strategic realities whilst we maintain our freedom, our right to be an independent nation, with our own foreign policy. We must anticipate frictions and difficulties from time to time. But our task is to maintain this whilst keeping in mind the broader relationships. Our approach as a state with independent foreign policy cannot be like that of a private company. Our state interests go far beyond the short term losses or gains of a private company. So, we have to stay nimble, be alert to dangers but seize opportunities.

But we need to also remember that some aspects remain consistent. We need to advance and protect our own interests. We must be prepared to make difficult decisions, weather the storms, if they come. We must be prepared to speak up, and if necessary, disagree with others, without being gratuitously disagreeable. We may always be a small state, but all the more reason we need the courage of our convictions and the resolution to secure the long term interests of all our citizens.

Join ST's WhatsApp Channel and get the latest news and must-reads.

- Singapore foreign policy

- Vivian Balakrishnan

Read 3 articles and stand to win rewards

Spin the wheel now

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Singapore's foreign policy: beyond realism

Related Papers

Business Horizons

Janamitra Devan

ICAS Publication Series

IIAS Leiden

This important overview explores the connections between Singapore's past with historical developments worldwide until present day. The contributors analyse Singapore as a city-state seeking to provide an interdisciplinary perspective to the study of the global dimensions contributing to Singapore's growth. The book's global perspective demonstrates that many of the discussions of Singapore as a city-state have relevance and implications beyond Singapore to include Southeast Asia and the world. This vital volume should not be missed by economists, as well as those interested in imperial history, business history and networks.

Journal of Contemporary Asia

Michael Barr

Abstract For decades Singapore’s ruling elite has sought to legitimate its rule by claiming to be a talented and competent elite that has made Singapore an exception among its neighbours – an exemplar of success and progress in a sea of mediocrity. In this article it is contended that this basis of legitimation has been irreversibly damaged. In essence, it is suggested that the governing People’s Action Party has lost control of the national narrative, and its achievements are increasingly regarded as being “ordinary” by the electorate. The mystique of exceptionalism, which was the basis on which the government was widely presumed to be above the need for close scrutiny and accountability, has collapsed. This collapse has substantially levelled the political playing field, at least in terms of expectations and assumptions. The government can and probably will continue to win elections and rule through its control of the instruments of institutional power, but the genie of scepticism and accountability has been released from its bottle, and it is hard to see how it can be put back in. This fundamentally changes the condition of Singapore politics: the narrative of exceptionalism is dead and the Singapore elite finds itself struggling to cope in a new and critical political environment.

David Phoon

Vulnerability is a naturally imposed and predictable condition that constrains policy decisions , hence lacking agency vis-à-vis other states. In Singapore's historical discourse, they are structural factors of limited material capabilities due to its geographical size that limits agency against larger powers, and presence of revisionist irredentist states that limits its agency compared to a state with peaceful neighbors. Older discourse stressed Singapore's 'smallness', neighboring of larger Muslim-majority states of 'others' with historical animosity, while newer discourse stresses the dangerous reliance on external economy, based on 'smallness', and newer 'others' such as terrorism and regional powers. I argue that 'smallness' defined by material deficiency, used to justify realist strategies, holds increasing discrepancies in describing outcomes and behavior formation in foreign policy. Both 'smallness' and the process of 'othering' are normative rather than static, creating a disjuncture between rhetoric and policy. Not only is the vulnerability discourse epistemically questionable, the functional value of perpetuating the vulnerability discourse has diminished to the extent that it detracts from the objectives of foreign policy in the future, as evident in Singapore’s maritime policies.

Alex Ferentzy

Ming Hwa Ting

Divya Radhakrishnan

This dissertation investigates the role of certain factors in key decisions made for Singapore’s survival and development in the period following the Second World War. The relationship between these factors and their respective decisions is examined, and a model of cause-and-effect is proposed to provide analysis to substantiate the arguments made. The dissertation follows Singapore’s separations from the three ‘empires’ of Japan, Britain, and Malaysia. The main themes of each ‘empire’ are examined: first, after the Japanese Occupation, the importance of providing social welfare and the background that made it necessary is discussed; secondly, the role of the communist threat on the decision for a Singapore-Malaya merger is examined; and finally, following Singapore’s separation from Malaysia, the decision to implement National Service is analysed, both as an essential defence policy and as a means to build a common national identity. It is argued that, counter to most previous research which has suggested that Singapore’s success can be attributed to, almost exclusively, successful economic policies, the relationship between Singapore’s varying social and political environments since the end of the Second World War and the resulting decisions made, did indeed have a significant impact on Singapore’s overall development and success. The aim is to answer the question of why the particular decisions that were made was imperative for Singapore’s survival and success, at each distinct period, through an analysis of the factors that made them necessary. Rather than the three periods themselves being the focus, this dissertation is written in the perspective of their influence on the decisions and ultimately the outcomes after the periods occurred. The very path that Singapore took to gain independence significantly contributed to not only its extraordinary developmental success, but also to the very survival of the little red dot.

Zachary S. Ritter

Journal of Southeast Asian Studies

Kumar Ramakrishna

RELATED PAPERS

ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering

inayat khan

International Journal of Social Science and Interdisciplinary Research

TRIPTIMOY MONDAL

IFAC Proceedings Volumes

Umaru Garba Wali

Kaums Journal

Fatemeh Esna-ashari

Leandro Tumino

Epidemiology and Infection

mustapha jouili

E-Jurnal Matematika

bagus pramartha

International Journal for Numerical Methods in Fluids

Luciana Pires

Intensive Care Medicine Experimental

Anne-claire Lukaszewicz

Acta Scientiarum. Agronomy

Pedro Junior

Geological Magazine

Kunio Kaiho

SENSITIf : Seminar Nasional Sistem Informasi dan Teknologi Informasi

Afnan Rosyidi

Journal of Molecular Endocrinology

Rana Alhamdan

Majalah Ilmiah Tabuah: Ta`limat, Budaya, Agama dan Humaniora

inggria kharisma

Journal of Engineering Materials and Technology-transactions of The Asme

Michael Groeber

Shilpi Shilpi

İstanbul Kuzey Klinikleri

Kamil Ozdil

Adeel Ahmed

jason roy75

Benjamin Carter

Civil and environmental research

Yihenew G.Selassie

Artificial Intelligence in Cyber security and Network security

Mack Praise

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Why Singapore works: five secrets of Singapore’s success

Public Administration and Policy: An Asia-Pacific Journal

ISSN : 2517-679X

Article publication date: 13 July 2018

Issue publication date: 5 September 2018

The purpose of this paper is to explain why Singapore is a success story today despite the fact that its prospects for survival were dim when it became independent in August 1965.

Design/methodology/approach

This paper describes the changes in Singapore’s policy context from 1959 to 2016, analyses the five factors responsible for its success and concludes with advice for policy makers interested in implementing Singapore-style reforms to solve similar problems in their countries.

Singapore’s success can be attributed to these five factors: the pragmatic leadership of the late Lee Kuan Yew and his successors; an effective public bureaucracy; effective control of corruption; reliance on the “best and brightest” citizens through investment in education and competitive compensation; and learning from other countries.

Originality/value

This paper will be useful to those scholars and policy makers interested in learning from Singapore’s success in solving its problems.

- Policy diffusion

- Lee Kuan Yew

- Pragmatic leadership

- Effective public bureaucracy

- Competitive compensation

Quah, J.S.T. (2018), "Why Singapore works: five secrets of Singapore’s success", Public Administration and Policy: An Asia-Pacific Journal , Vol. 21 No. 1, pp. 5-21. https://doi.org/10.1108/PAP-06-2018-002

Emerald Publishing Limited

Copyright © 2018, Jon S.T. Quah

Published in Public Administration and Policy . Published by Emerald Publishing Limited. This article is published under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) licence. Anyone may reproduce, distribute, translate and create derivative works of this article (for both commercial and non-commercial purposes), subject to full attribution to the original publication and authors. The full terms of this licence may be seen at http://creativecommons.org/licences/by/4.0/legalcode

Explaining Singapore’s success

Singapore is the smallest of […] Asia’s four “Little Dragons” […] but in many ways it is the most successful. Singapore is Asia’s dream country. […] Singapore’s success says a great deal about how a country with virtually no natural resources can create economic advantages with influence far beyond its region. […] But it certainly is an example of an extraordinarily successful small country in a big world ( Naisbitt, 1994 , pp. 252, 254).

We had been asked to leave Malaysia and go our own way with no signposts to our next destination. We faced tremendous odds with an improbable chance of survival. […] On that 9th day of August 1965, I started out with great trepidation on a journey along an unmarked road to an unknown destination (pp. 19, 25).

Fortunately for Singaporeans, Lee’s fears were unfounded as Singapore has not only survived but has been transformed from a Third World country to a First World country during the past 53 years. The tremendous changes in Singapore’s policy context from 1959 to 2016 are shown in Table I . First, Singapore’s land area has increased by 137.7 km 2 from 581.5 km 2 in 1959 to 719.2 km 2 in 2016 as a result of land reclamation efforts. Second, as a consequence of its liberal immigration policy, Singapore’s population has increased by 3.6 times from 1.58 to 5.61m during the same period. Third, the most phenomenal manifestation of Singapore’s transformation from a poor Third World country to an affluent First World nation during 1960–2016 is that its GDP per capita has increased by 56 times from S$1,310 to S$73,167. Fourth, Singapore’s official foreign reserves have grown by 310 times from S$1,151m in 1963 to S$356,253.9m in 2016.

The lives of Singaporeans have also improved as reflected in the drastic decline in the unemployment rate from 14 per cent to 2.1 per cent during 1959–2016. Furthermore, the proportion of the population living in public housing has also increased from 9 per cent in 1960 to 82 per cent in 2016. Government expenditure on education has also risen by 200 times from S$63.39m in 1959 to S$12,660m in 2016. The heavy investment by the People’s Action Party (PAP) government on education during the past 57 years has reaped dividends as reflected in Singapore’s top ranking among 76 countries on the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development’s study on the provision of comprehensive education ( Teng, 2015 , p. A1). Finally, as a result of the effectiveness of the Corrupt Practices Investigation Bureau (CPIB) in enforcing the Prevention of Corruption Act (POCA) impartially, corruption has been minimised in Singapore, which is the least corrupt Asian country according to Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) in 2016 and 2017.

The following five sections in this paper will be devoted to analysing the secrets of Singapore’s success, beginning with the important legacy of Lee Kuan Yew’s pragmatic leadership. The concluding section advises policy makers in other countries on the relevance and applicability of Singapore’s secrets of success to the solution of their problems.

Pragmatic leadership: Lee Kuan Yew’s legacy

During the recent Non-Aligned Meeting in Jakarta, the Nepalese Prime Minister asked me for the secret of Singapore’s success. I smiled and replied, “Lee Kuan Yew.” I went on to explain that I meant it as a short form to encapsulate the principles, values and determination with which he governed and built Singapore ( Goh, 1992 , p. 15).

In the same speech, Goh (1992 , p. 15) concluded that meritocracy was the key to Singapore’s success because the “practice of meritocracy in the civil service, in politics, in business and in schools” enabled Singaporeans “to achieve excellence and to compete against others”.

My experience of developments in Asia has led me to conclude that we need good men to have good government. However good the system of government, bad leaders will bring harm to their people. […] The single decisive factor that made for Singapore’s development was the ability of its ministers and the high quality of the civil servants who supported them.

Indeed, leaders matter because of their role in “stretching” the constraints of “geography and natural resources, institutional legacies and international location” ( Samuels, 2003 , pp. 1-2). Applying Richard Samuels’ concept of political leadership, Lee and his colleagues have succeeded in stretching those constraints facing them and transformed Singapore to First World status by 2000, 41 years after assuming office in June 1959.

In addition to his belief in the importance of having good leaders, Lee was also a pragmatic leader. In November 1993, Lee advised visiting African leaders to adopt a pragmatic approach in formulating economic policy rather than a dogmatic stance. Instead of following the then-politically correct approach of being anti-American and anti-multinational corporations (MNCs) in the 1960s and 1970s, Lee and Singapore went against the grain and “assiduously courted MNCs” because “they had the technology, know-how, techniques, expertise and the markets” and “it was a fast way of learning on the job working for them and with them”. This strategy of relying on the MNCs paid off as “they have been a powerful factor in Singapore’s growth”. Lee (1994 , p. 13) concluded that Singapore succeeded because it “rejected conventional wisdom when it did not accord with rational analysis and its own experience”.

Number one is: get rid of the Communists; how you get rid of them does not interest me as an economist, but get them out of the government, get them out of the unions, get them off the streets. How you do it, is your job. Number two is: let [the statue of Stamford] Raffles [who founded Singapore] stand where he stands today; say publicly that you accept the heavy ties with the West because you will very much need them in your economic programme (quoted in Drysdale, 1984 , p. 252).

As a rational and pragmatic leader, Lee took Winsemius’ advice seriously, neutralised the communist threat and attracted many MNCs from the USA, Europe and Japan to Singapore. After Winsemius’ death in December 1996, Lee acknowledged Singapore’s debt as he had learnt from Winsemius a great deal about the operations of European and American companies and how he and his colleagues could attract them to invest in Singapore ( Lee, 1996 , p. 32). Singapore succeeded in developing its economy because Lee implemented the sound economic policies recommended by Winsemius.

I do not work on a theory. Instead I ask: what will make this work? If, after a series of such solutions, I find that a certain approach worked, then I try to find out what was the principle behind the solution. […] What is my guiding principle? Presented with the difficulty or major problem or an assessment of conflicting facts, I review what alternatives I have if my proposed solution doesn’t work. I choose a solution which offers a higher probability of success, but if it fails, I have some other way. Never a dead end (quoted in Plate, 2010 , pp. 46-47).

In short, Singapore has adopted a pragmatic approach to policy formulation which entails “a willingness to introduce new policies or modify existing ones as circumstances dictate, regardless of ideological principle” ( Jones, 2016 , p. 316).

A good piano playing good music: an effective public bureaucracy

Sir Kenneth Stowe, a former Permanent Secretary of the UK’s Department of Health and Social Security (1981–1987), has described “the efficient and well-tuned public service” as a “good piano” which should not “play bad music” by not “serving ends which are wrong by ministerial design or incompetence” ( Stowe, 1996 , pp. 89-90). The second secret of Singapore’s success is that it has an effective public bureaucracy that plays good music, to use Stowe’s analogy. The public bureaucracy in Singapore consists of 16 ministries and 64 statutory boards ( Republic of Singapore, 2018 ) and has grown from 127,279 to 144,980 employees during 2010–2016, as shown in Table II .

The World Bank defines “government effectiveness” as “the quality of public service provision, the quality of the bureaucracy, the competence of civil servants, the independence of the civil service from political pressures, and the credibility of the government’s commitment to policies” ( Kaufmann et al. , 2004 , p. 3). Table III shows that Singapore has performed well consistently on the World Bank’s governance indicator of government effectiveness as its score ranges from 1.85 in 2002 to 2.43 in 2008. It has attained 100 percentile ranking for these ten years: 1996, 1998, 2000, 2007, 2008, 2009, 2010, 2014, 2015 and 2016.

Thus, it is not surprising that Singapore is ranked first for government effectiveness in 2016 as shown in Table IV . A comparative analysis of the role of the public bureaucracy in policy implementation in five ASEAN countries has confirmed that Singapore is the most effective because of its favourable policy context and its effective public bureaucracy. The emphasis on meritocracy and training in Singapore’s public bureaucracy has resulted in a high level of competence of the personnel in implementing policies ( Jones, 2016 , p. 319). Conversely, Indonesia is the least effective because of its unfavourable policy context and its ineffective public bureaucracy. Malaysia, Vietnam and the Philippines occupy intermediate positions between Singapore and Indonesia and are ranked second, third and fourth, respectively, depending on the nature of their policy contexts and the levels of effectiveness of their public bureaucracies ( Quah, 2016a , p. 72).

Sustaining clean government: keeping corruption at bay

Stay clean: dismiss the venal ( Lee, 1979 , p. 38).

Corruption was a serious problem in Singapore during the British colonial period because of the government’s lack of political will and the ineffective Anti-Corruption Branch (ACB), which had only 17 personnel to deal with both corruption and non-corruption-related functions and was handicapped in tackling police corruption because it was located within the Criminal Investigation Department of the Singapore Police Force (SPF) ( Quah, 2007 , pp. 14-15). The problem of corruption deteriorated during the Japanese Occupation (February 1942 to August 1945) as civil servants could not survive on their low wages because of the high inflation rate and the scarcity of food and other commodities forced many people to trade in the black market. The Japanese Occupation’s worst legacy was “the corruption of public and private integrity: flourishing gambling dens and brothels, both legalised by the Japanese, the resurgence of opium smoking, universal profiteering and bribery” ( Turnbull, 1977 , p. 225).

We were sickened by the greed, corruption and decadence of many Asian leaders. […] We had a deep sense of mission to establish a clean and effective government. When we took the oath of office […] in June 1959, we all wore white shirts and white slacks to symbolise purity and honesty in our personal behaviour and our public life. […] We made sure from the day we took office in June 1959 that every dollar in revenue would be properly accounted for and would reach the beneficiaries at the grass roots as one dollar, without being siphoned off along the way. So from the very beginning we gave special attention to the areas where discretionary powers had been exploited for personal gain and sharpened the instruments that could prevent, detect or deter such practices ( Lee, 2000 , pp. 182-184).

As corruption was endemic in Singapore when the PAP leaders assumed office, they learned from the mistakes made by the British colonial government in curbing corruption and showed their political will by enacting the POCA on 17 June 1960 to replace the ineffective Prevention of Corruption Ordinance (POCO) and to strengthen the CPIB by providing it with more legal powers, personnel and funding. The British colonial government’s most serious error was to make the ACB, which was part of the SPF, responsible for corruption control with the enactment of the POCO in December 1937 even though the 1879 and 1886 Commissions of Inquiry had confirmed the prevalence of police corruption in Singapore ( Quah, 2007 , pp. 9, 14, 16). The British authorities failed to observe the “golden rule” that “the police cannot and should not be responsible for investigating their deviance and crimes” ( Punch, 2009 , p. 245).

The folly of making the ACB responsible for curbing corruption was only realised by the British colonial government in October 1951 when three police detectives and some senior police officers were implicated in the Opium Hijacking scandal involving the robbery of 1,800 pounds of opium worth S$400,000 (US$133,333) ( Tan, 1999 , p. 59). It corrected the first mistake by replacing the ACB with the CPIB in September 1952 as a Type A anti-corruption agency (ACA) dedicated to combating corruption. However, it made a second mistake by not providing the CPIB with adequate legal powers, budget and personnel to perform its functions effectively. The POCO did not provide CPIB officers with adequate enforcement powers and the CPIB was ineffective because its reliance on 13 seconded personnel from the SPF hindered the investigation of police officers accused of corruption offences ( Quah, 2017 , p. 266).

Unlike the British colonial government’s weak political will in combating corruption, the PAP leaders realised from the outset the critical importance of political will by enhancing the CPIB’s legal powers and providing it with the required personnel and budget to perform its functions effectively. The substantial growth in the CPIB’s budget and personnel from 2010 to 2015 is shown in Table V and reflected in the increase of its per capita expenditure from US$2.88 in 2010 to US$4.55 in 2015. The CPIB’s staff-population ratio has also improved from 1:56,408 to 1:26,109 during the same period.

Apart from its adequate legal powers, budget and personnel, the CPIB is an effective Type A ACA for four reasons. First, even though the CPIB comes under the jurisdiction of the Prime Minister’s Office, it has operational autonomy because the prime minister and other political leaders do not interfere in its daily operations and its director reports to the secretary of the cabinet. Furthermore, the CPIB’s director can obtain the elected president’s consent to investigate allegations of corruption against ministers, members of parliament and senior civil servants if the prime minister withholds his consent ( Quah, 2007 , pp. 40-41).

Second, the CPIB adopts a “total approach to enforcement” and deals with both major and minor cases of public and private sector corruption, regardless of the amount, rank or status of the persons under investigation. The same processes and procedures apply to everyone being investigated, including ministers and chief executive officers of major companies. Both bribe-givers and bribe-takers are equally culpable according to the POCA ( Soh, 2008 , pp. 1-2).

Third, the CPIB’s effectiveness is also the result of its efforts to enhance the capabilities of its officers by sending them for training programmes on management and professional topics in Singapore and other countries. In July 2004, the CPIB created a Computer Forensics Unit to improve the investigative and evidence-gathering skills of its officers by providing them with the knowledge of forensic accounting to enable them to trace ill-gotten assets and retrieve incriminating evidence from seized computers and mobile telephones. The CPIB has also conducted joint operations with the Commercial Affairs Department and the Immigration and Checkpoints Authority to develop networks and partnerships with other public agencies in Singapore ( Soh, 2008 , pp. 3-4).

Finally, the most important reason for the CPIB’s success is its impartial enforcement of the POCA as anyone found guilty of a corruption offence is punished regardless of his or her position, status or political affiliation. The CPIB has investigated five PAP leaders and eight senior civil servants in Singapore without fear or favour from 1966 to 2014. In November 1986, the Minister for National Development, Teh Cheang Wan, was accused of accepting S$1m in bribes from two property developers. He was investigated and interrogated by CPIB officers but he committed suicide one month later before he could be charged in court. In July 2013, Edwin Yeo, the CPIB’s Assistant Director, was charged with misappropriating US$1.41m from 2008 to 2012. He was found guilty of criminal breach of trust and forgery and sentenced to ten years imprisonment on 20 February 2014 ( Quah, 2015a , pp. 77, 80-81).

The CPIB’s effectiveness is confirmed by its 100 per cent conviction rate and the CPIB Public Perceptions Survey’s finding that 89 per cent of the 1,011 respondents had rated Singapore positively on its anti-corruption efforts in 2016 ( CPIB, 2017 , pp. 7, 9). Its effectiveness is also reflected in Singapore’s sixth ranking among 180 countries with a score of 84 on the CPI in 2017 ( Transparency International, 2018 ) and its consistently good performance on the other five indicators of the perceived extent of corruption in Table VI . The sixth indicator, “Public Trust in Politicians”, is included as an indirect indicator because “corruption influences the level of trust” and citizens living in those countries where corruption is widespread would have low trust in their politicians ( Rose-Ackerman and Palifka, 2016 , p. 259).

Nurturing the “best and brightest”: education and competitive compensation

If we underpay men of quality as ministers, we cannot expect them to stay long in office earning a fraction of what they could outside. […] Underpaid ministers and public officials have ruined many governments in Asia ( Lee, 2000 , p. 193).

Education is the key to the long-term future of the population in Singapore which has no natural resources. Former Prime Minister Goh Chok Tong observed in March 1997 that Singapore was “blessed” by its lack of natural resources because it was forced to develop its only resource: its people ( Chua, 1997 , p. 1). In other words, Singapore has compensated for its absence of natural resources by investing heavily in education to enhance the skills of its population and to attract the “best and brightest” Singaporeans to join and remain in the public bureaucracy and government by its policies of meritocracy and paying these citizens competitive salaries.

The PAP government views education as “a national investment” and has increased government expenditure on education by about 200 times from S$63.39m in 1959 to S$12,660m in 2016. Consequently, the enrolment in all educational institutions in Singapore has grown from 352,952 students in 1960 to 651,655 students in 2016, and the literacy rate has also improved from 72.2 per cent in 1970 to 97.0 per cent in 2016 ( Department of Statistics, 1983 , pp. 231, 248, 249; 2017 , pp. 281, 296, 299). Singapore’s intensive investment in education and training during the past 57 years has certainly enhanced the quality of its population as reflected in the excellent performance of its students in many international assessments.

In 1997, the Third International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS), which compared the scores of 13-year-olds in mathematics and science tests in 41 countries, ranked Singapore first in both subjects with scores of 643 and 607, respectively, which were significantly higher than the international average score of 500 ( Economist, 1997 , p. 21). In 2015, Singapore students not only retained their top position in both subjects in the TIMSS assessment but also topped the Program for International Student Assessment of 65 countries in mathematics, reading and science literacy skills, and, as mentioned earlier, the OECD’s global school rankings in 76 countries ( Goodwin et al. , 2017 , pp. 1-2).

Singapore was a poor country when the PAP government assumed office in June 1959 and inherited a huge budget deficit because the previous Labour Front government had spent S$200m. Accordingly, it removed the cost of living allowance for 6,000 middle and senior civil servants and saved S$10m. In 1968, the Harvey Report on public sector salaries recommended salary increases for senior civil servants in the Superscale Grades C to G. The government did not accept this recommendation because it could not afford a major salary revision and the private sector was not viewed as a serious competitor for talented personnel ( Quah, 2015b , p. 383).

However, the improvement in Singapore’s economy in the 1970s resulted in higher private sector salaries, which led to an exodus of talented senior civil servants to more lucrative jobs in the private sector. In February 1972, the National Wages Council was established to advise the government on wage polices and, one month later, it recommended that all public sector employees be paid a 13th-month non-pensionable allowance comparable to the bonus in the private sector. The salaries of senior civil servants were increased substantially in 1973 and 1979 to reduce the gap with the private sector. A 1981 survey of 30,197 graduates in Singapore conducted by the Internal Revenue Department found that graduates in the private sector jobs earned, on the average, 42 per cent more than their counterparts working in the public sector. Consequently, it was not surprising that eight superscale and 67 timescale administrative officers had resigned from the civil service for better-paid private sector jobs. The government responded by revising the salaries of senior civil servants in 1982, 1988, 1989 and 1994 to reduce the gap with private sector salaries and to minimise their outflow to the private sector ( Quah, 2010 , pp. 104-110).

On 17 March 1989, Lee Hsien Loong, the Minister for Trade and Industry, recommended a hefty salary increase for senior civil servants because the low salaries and slow promotion in the Administrative Service had contributed to its low recruitment and high resignation rates. He stressed that as the government’s fundamental philosophy was to “pay civil servants market rates for their abilities and responsibilities”, it “will offer whatever salaries are necessary to attract and retain the talent that it needs”. He concluded his speech in Parliament by reiterating that “paying civil servants adequate salaries is absolutely essential to maintain the quality of public administration” in Singapore ( Quah, 2010 , pp. 107-108).

To justify the government’s practice of matching public sector salaries with private sector salaries, a White Paper on “ Competitive Salaries for Competent and Honest Government ” was presented to Parliament on 21 October 1994 to justify the pegging of the salaries of ministers and senior civil servants to the average salaries of the top four earners in the six private sector professions of accounting, banking, engineering, law, local manufacturing companies and MNCs. The adoption of the long-term formula suggested in the White Paper removed the need to justify the salaries of ministers and senior civil servants “from scratch with each salary revision”, and also ensured the building of “an efficient public service and a competent and honest political leadership, which have been vital for Singapore’s prosperity and success” ( Republic of Singapore, 1994 , pp. 7-12, 18).

In December 2007, the Public Service Division (PSD) announced that the salaries of ministers and senior civil servants would be increased from 4 to 21 per cent from January 2008. On 24 November 2008, the PSD indicated that their salaries would be decreased by 19 per cent in 2009 because of the economic recession. Consequently, the president’s annual salary was reduced from S$3.87m to S$3.14m and the prime minister’s annual salary was also reduced from S$3.76m to S$3.04m from 2008 to 2009 ( Quah, 2010 , p. 116). However, the economy recovered in 2010 and the salaries of ministers and senior civil servants were revised upwards. Even though the PAP won 81 of the 87 parliamentary seats in the May 2011 general election, the percentage of votes captured declined to 60.1 from 66.6 per cent in the May 2006 general election.

As the high salaries of political appointments were a controversial issue during the campaign for the 7 May 2011 general election, Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong appointed on 21 May a committee to “review the basis and level of salaries for the President, Prime Minister, political appointment holders and MPs [Members of Parliament] to ensure that the salary framework will remain relevant for the future”. The Committee submitted its report to Prime Minister Lee on 30 December 2011 and the government accepted all its recommendations and implemented the revised salaries from 21 May 2011 ( Republic of Singapore, 2012 , pp. i-ii). Table VII shows the substantial reduction in the annual salaries of key political appointments from 2010 to 2011, ranging from S$1,627,000 for the president to S$103,700 for the minister of state.

In December 2017, an independent committee formed by the PAP government a few months earlier to review ministerial salaries recommended wage increases for key political appointments as their salaries had not risen since 2011 to keep pace with salary increases in Singapore’s private sector. For example, as the annual salary of an entry-level minister (MR4) is benchmarked to 60 per cent of the median income of the top 1,000 earners in Singapore, the committee recommended increasing his annual salary from S$1.1m to S$1.2m. During the debate on the 2018 budget for ministries on 1 March 2018, Deputy Prime Minister Teo Chee Hean did not accept the committee’s recommendations and explained that the government would not be increasing ministerial salaries because the committee had confirmed that the current salary structure was still relevant and sound ( Seow, 2018 , p. A4). As the salaries of Singapore’s ministers and senior civil servants are already the highest in the world, any further salary increase would be unpopular among Singaporeans and politically costly for the PAP government.

Edgar Schein (1996 , pp. 221-222) attributed Singapore’s success to its incorruptible and competent civil service as “having the best and brightest” citizens in government is probably one of Singapore’s major strengths in that they are potentially the most able to invent what the country needs to survive and grow”. Indeed, the PAP government’s policy of paying competitive salaries to attract the “best and brightest” Singaporeans to join the public bureaucracy has been successful as reflected in Singapore’s consistently high scores and percentile rankings on the World Bank’s governance indicator on government effectiveness as shown in Table III .

Learning from other countries: the importance of policy diffusion

The object of looking abroad is not to copy but to learn under what circumstances and to what extent programmes effective elsewhere may also work here. Moreover, the failures of other governments offer lessons about what not to do at far less political cost than making the same mistakes yourself ( Rose, 2005 , p. 1).

An important strength of the PAP government is its willingness to learn from the experiences of other countries by not repeating the mistakes they have made in solving their problems. Thus, instead of “reinventing the wheel”, which is unnecessary and expensive, the PAP leaders and senior civil servants would consider what has been done in other countries and the private sector to identify suitable solutions for resolving policy problems in Singapore. The policy solutions selected would usually be adapted and modified to suit Singapore’s context. For example, the government examined the Japanese and French civil services and the Shell Company’s system of performance appraisal as part of its efforts to improve personnel management in Singapore’s public bureaucracy ( Quah, 2010 , pp. 79-81). Lee Kuan Yew revealed in his memoirs that he had consulted corporate leaders of MNCs on how they recruited and promoted senior personnel and adopted the Shell Company’s performance appraisal system for Singapore’s public bureaucracy in 1983 “after trying out the [Shell] system and finding it practical and reliable” ( Lee, 2000 , pp. 740-741).

The reliance on “policy diffusion” or the “emulation and borrowing of policy ideas and solutions from other nations” ( Leichter, 1979 , p. 42) is an important strategy adopted by the PAP government to deal with problems. The three steps in the process of “pragmatic acculturation” are: problem identification and sending a team of experts and officials on a fact-finding tour of relevant technical centres and organisations in other countries to learn how the same problems are solved; invitation of internationally renowned experts to Singapore to give their professional opinions; and formulation of the policy plan from the ideas selected from what has been learned about the problem and tailored to the specific needs of Singapore. If the ideas and procedures used elsewhere are unsuitable for Singapore’s needs, they are not adopted ( Quah, 1995 , p. 55). Singapore’s Changi Airport, which is recognised as one of the best airports in the world today, provides a good illustration of pragmatic acculturation as a team of officials was sent initially to several countries to examine the best and worst airports with the aim of building an airport which would be better than Netherlands’ Schiphol Airport (considered the best airport then) and avoiding the problems faced by New York’s Kennedy Airport or Heathrow Airport in Britain.

During the early years after independence, Singapore looked towards such small nations as Israel and Switzerland as role models for inspiration to formulate relevant public policies for defence and other areas. Later, other countries like West Germany (for technical education), the Netherlands (Changi Airport was modelled after Schiphol Airport) and Japan (for quality control circles and crime prevention) were added to the list. The important lesson in these learning experiences is the adoption by Singapore of ideas which have worked elsewhere (with suitable modification to consider Singapore’s context if necessary) as well as the rejection of unsuccessful schemes in other countries.

But nothing is for free in this world and the end result of indiscriminate welfare state policies is bankruptcy. […] In several West European countries, unemployment benefits have been so generous that some workers are better off unemployed! The money to pay for welfare state expenditure must come either from taxes or from the printing press. Increasing taxes, which mainly affects the rich, reduces the amount of money available for investment, thereby slowing down economic growth. Printing paper money to avoid unpleasant tax increases merely results in more inflation ( Goh, 1977 , p. 166).

Considering the limitations of the welfare state in Western Europe and the USA, the PAP government views social welfare as a consumption good and is concerned that “government provision of social welfare” would result in “an unhealthy dependence on the state and sap individual initiative and enterprise, thereby also undermining growth”. China, Jamaica and Sri Lanka have abandoned their welfare policies as “guaranteed social welfare” is expensive and inappropriate for developing countries. Consequently, the PAP government’s policy is “to reduce welfare to the minimum” and restrict it to “only those who are handicapped or old” ( Lim, 1989 , pp. 172, 187).

In short, policy diffusion remains an asset for Singapore so long as there is intelligent sifting of relevant policy ideas and solutions tested elsewhere by the policy makers without blind acceptance and wholesale transplantation of foreign innovations without modification to suit the local context.

Applicability of Singapore’s experience for other countries

[…] while it is difficult if not impossible to transfer public administration Singapore-style in toto to other Asian countries, it is nevertheless possible for these countries to emulate and adapt some features of public administration Singapore-style to suit their own needs, provided that their political leaders, civil servants, and population are prepared to make the necessary changes ( Quah, 2010 , p. 255).

Having identified and analysed the five secrets of Singapore’s success, the question that remains is whether policy makers in other countries could learn from Singapore’s experience to solve similar problems in their countries. After his first visit to Singapore on 12-14 November 1978, Deng Xiaoping “found orderly Singapore an appealing model for reform” and sent many Chinese officials to Singapore to “learn about city planning, public management, and controlling corruption” ( Vogel, 2011 , p. 291). Consequently, 400 delegations of mayors, governors and party secretaries from China visited Singapore on study missions following Deng’s visit ( Asiaweek, 1994 , p. 24).

Policy makers in other countries who are interested in applying Singapore’s secrets of success to solve their problems must consider three important aspects. First, they must recognise the significant contextual differences between Singapore, which is an affluent, politically stable city-state with a small land area and population, and their countries, which have lower GDP per capita and larger territories and populations. The relevance of Singapore’s approach would depend on the extent to which the policy contexts in other countries approximate Singapore’s policy context. Indeed, the contextual differences would make it difficult for larger countries like China and India with huge populations to adopt in toto Singapore-style solutions to their problems.

Yes—but there are over one hundred metropolitan areas in China that have a population of Singapore’s size or greater. The Singapore model may work if you can devote all your resources to it—but I don’t know if even the Chinese with all their resources, all their cleverness, and all their determination can do it a hundred times (quoted in Burstein and de Keijzer, 1998 , p. 171).

During his second visit to Singapore in 1980, Deng himself acknowledged the burden of China’s huge population and vast territory when he lamented that: “If I had only Shanghai, I too might be able to change Shanghai as quickly [as Singapore]. But I have the whole of China!” (quoted in Lee, 2000 , pp. 667-668).

The successful policy of country A [Singapore] cannot simply be replanted in the soil of struggling target country B [China]. Instead careful attention must be directed to the wider policy contexts involved as well as to the feasibility of policy transfer. […] Policies, like garden plants, cannot simply be plucked from one environment to be replanted in another. There are questions of soil type, rainfall, and sunlight just as there are questions of government capacity, efficiency and integrity.

The second consideration for those policy makers interested in applying Singapore’s secrets of success to solving their domestic problems is whether they have the political will to allocate the necessary resources and mobilise the required support from various stakeholders to implement Singapore-style policies effectively in their countries. Apart from their contextual differences with Singapore, other countries might lack these prerequisites for the PAP government’s effectiveness in policy implementation, namely, political stability; a strong parliamentary majority; economic affluence; a low level of corruption; rule of law; and an effective public bureaucracy.

For example, it would be too expensive economically and politically for many countries to pay competitive public sector salaries to attract the “best and brightest” citizens to join the public bureaucracy and government and to motivate and retain them. In his 2000 National Day Rally speech, Prime Minister Goh Chok Tong emphasised the need to ensure good government in Singapore by “recruiting good people for government and paying them properly”. However, Goh (2000) admitted that many western leaders informed him privately that while they “envied our system of Ministers’ pay”, they added that “if they tried to implement it in their own countries, they would be booted out” (p. 44).

China is ranked 77th among 180 countries with a score of 41 on the CPI in 2017 ( Transparency International, 2018 , p. 2). This means that corruption remains a serious problem in China in spite of President Xi Jinping’s five-year-old campaign to curb corruption among the “tigers” and “flies”, which is ineffective because of its failure to address the causes of corruption, the selective enforcement of the anti-corruption laws by the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection (CCDI), and the reliance of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) leaders on corruption as a weapon against their political opponents ( Quah, 2015c , pp. 84-87).

In August 2014, Wang Qishan, Secretary of the CCDI, observed that: “China should learn from the Hong Kong or Singapore model for tackling corruption as both have independent anti-corruption bodies, unlike China which relies on the party investigating itself” ( Wang, 2014 ). As China is a communist state with political power monopolised by the CCP, it is unrealistic to expect the CCP to introduce the necessary reforms to enhance the effectiveness of its anti-corruption strategy by establishing a single independent ACA like the CPIB and provide it with the required personnel and budget to enforce the anti-corruption laws impartially against corrupt offenders, regardless of their status, position or political affiliation and to avoid using corruption as a weapon against political foes ( Quah, 2016b , p. 208).

Learning from Singapore’s experience, China will only succeed in minimising corruption if the CCP leaders are willing to introduce checks on their power and if they introduce reforms to address the causes of corruption. However, barring unforeseen circumstances, it is highly unlikely that President Xi Jinping and his colleagues would be willing to pay the exorbitant price required for curbing corruption in China because the implementation of the necessary anti-corruption reforms could lead to the CCP’s demise ( Quah, 2016b , p. 209). In short, do policy makers elsewhere have the political will to pay the high political and economic costs of implementing Singapore-style policy reforms in their countries?

There was never a Singapore miracle. It was simply hard-headed policy. […] Because governments which dare to face a situation, analyse it and take measures without compromise are rather scarce in this world. […] If it happened in other countries, it might be a miracle. But what happened in Singapore was not a miracle. It was policy (quoted in Mukherjee, 2015 , pp. 33, 47).

As mentioned above, Singapore policy makers have not hesitated to learn from other countries’ experiences to formulate relevant policies with appropriate modifications for the local context. However, when Singapore faces problems which other countries cannot solve, the PAP leaders initiate innovative solutions to solve these problems. As the British colonial government failed to solve the serious housing shortage and widespread corruption, the PAP government initiated innovative solutions to tackle these two problems after assuming office in June 1959 ( Quah, 2011 , p. 122). In February 1960, the Housing and Development Board (HDB) was established as a statutory board to solve the housing shortage by providing low-cost public housing for Singaporeans. In June 1960, the POCA was enacted to strengthen the CPIB’s effectiveness in combating corruption.

The HDB’s effective public housing programme has resulted in the building of 1,129,236 flats from its inception in February 1960 to December 2016 and increasing the proportion of the population living in public housing in Singapore from 9 to 82 per cent during this period ( Department of Statistics, 2017 , pp. 134, 144). As discussed in the fourth section above, the CPIB’s effectiveness in minimising corruption is reflected in Table VI , which depicts Singapore’s good performance on six corruption indicators in 2017. Thus, housing and corruption are no longer serious problems in Singapore today because of the effective and innovative strategies adopted by the HDB and CPIB, respectively, to solve these problems.

In the final analysis, bearing in mind the contextual differences and the preconditions for Singapore’s success, policy makers in other countries must have the political will and be prepared to pay the high political and economic price for implementing Singapore-style reforms with appropriate modifications to solve their problems.

Changes in Singapore’s policy context, 1959–2016

Notes: The average exchange rates were: US$1=S$1.3635 in 2010 and US$1=S$1.2579 in 2011 ( Department of Statistics, 2017 , p. 217)

Source: Republic of Singapore (2012 , pp. 32-37)

Asiaweek ( 1994 ), “ Selling success: Singapore has found its most attractive export yet—itself ”, 13 July , pp. 24 - 27 .

Burstein , D. and de Keijzer , A. ( 1998 ), Big Dragon, The Future of China: What it Means for Business, the Economy, and the Global Order , Simon & Schuster , New York, NY .

Chan , C.B. ( 2002 ), Heart Work , Economic Development Board and EDB Society , Singapore .

Chua , M.H. ( 1997 ), “ No resources, so Singapore tapped its people ”, Straits Times, 7 March, p. 1 .

CPIB ( 2017 ), Annual Report 2016 , Corrupt Practices Investigation Bureau , Singapore , pp. 1 - 17 .

Department of Statistics ( 1983 ), Economic and Social Statistics Singapore 1960–1982 , Singapore National Printers , Singapore .

Department of Statistics ( 2017 ), Yearbook of Statistics Singapore, 2017 , Ministry of Trade and Industry , Singapore .

Department of Statistics ( 2018 ), “ Singapore’s Per Capita GNI and Per Capita GDP at Current Market Prices, 1960–2016 ”, Department of Statistics , Singapore , available at: www.tablebuilder.singstat.gov.sg/publicfacing/dataTable.action (accessed 26 January 2018 ).

Drysdale , J. ( 1984 ), Singapore: Struggle for Success , Times Books International , Singapore .

( The ) Economist ( 1997 ), “ World education league: who’s top? ”, 29 March, pp. 21-22, 25 .

Goh , C.T. ( 1992 ), “ My urgent mission ”, Petir , Nos 11-12/92 , pp. 10 - 19 .

Goh , C.T. ( 2000 ), National Day Rally Speech on 20 August 2000 , Ministry of Information and the Arts , Singapore .

Goh , K.S. ( 1977 ), The Practice of Economic Growth , Federal Publications , Singapore .

Goodwin , A.L. , Low , E.-L. and Darling-Hammond , L. ( 2017 ), Empowered Educators in Singapore: How High-Performing Systems Shape Teaching Quality , Jossey-Bass , San Francisco, CA .

Han , F.K. , Fernandez , W. and Tan , S. ( 1998 ), Lee Kuan Yew: The Man and His Ideas , Times Edition , Singapore .

Jones , D.S. ( 2016 ), “ Governance and meritocracy: a study of policy implementation in Singapore ”, in Quah , J.S.T. (Ed.), The Role of the Public Bureaucracy in Policy Implementation in Five ASEAN Countries , Chapter 5 , Cambridge University Press , Cambridge , pp. 297 - 369 .

Kaufmann , D. , Kraay , A. and Mastruzzi , M. ( 2004 ), Governance Matters III: Governance Indicators for 1996–2002 , revised version , World Bank , Washington, DC .

Lee , K.Y. ( 1979 ), “ What of the past is relevant to the future? ”, People’s Action Party 1954–1979: Petir 25th Anniversary Issue , PAP Central Executive Committee , Singapore , pp. 30 - 43 .

Lee , K.Y. ( 1994 ), “ Can Singapore’s experience be relevant to Africa? ”, Can Singapore’s Experience be Relevant to Africa? , Singapore International Foundation , Singapore , pp. 1 - 15 .

Lee , K.Y. ( 1996 ), “ Singapore is indebted to Winsemius: SM ”, Straits Times , 10 December, p. 32 .

Lee , K.Y. ( 2000 ), From Third World to First, The Singapore Story: 1965–2000 , Times Media , Singapore .

Leichter , H.M. ( 1979 ), A Comparative Approach to Policy Analysis: Health Care in Four Nations , Cambridge University Press , Cambridge .

Lim , L.Y.C. ( 1989 ), “ Social welfare ”, in Sandhu , K.S. and Wheatley , P. (Eds), Management of Success: The Moulding of Modern Singapore , Chapter 8 , Institute of Southeast Asian Studies , Singapore , pp. 171 - 197 .

Mukherjee , J. ( 2015 ), UNDP and the Making of Singapore’s Public Service: Lessons from Albert Winsemius , UNDP Global Centre for Public Service Excellence , Singapore .

Naisbitt , J. ( 1994 ), Global Paradox: The Bigger the World Economy, The More Powerful Its Smallest Players , William Morrow , New York, NY .

Pease , R.M. ( 1996 ), Policy Learning: The Case of Singapore Policy Models for Reform in Urban China , MSocSc thesis, Department of Political Science, National University of Singapore, Singapore .

Plate , T. ( 2010 ), Conversations with Lee Kuan Yew, Citizen Singapore: How to Build a Nation , Marshall Cavendish , Singapore .

Punch , M. ( 2009 ), Police Corruption: Deviance, Accountability and Reform in Policing , Routledge , London .

Quah , J.S.T. ( 1982 ), “ Bureaucratic corruption in the ASEAN countries: a comparative analysis of their anti-corruption strategies ”, Journal of Southeast Asian Studies , Vol. 13 No. 1 , pp. 153 - 177 .

Quah , J.S.T. ( 1998 ), “ Singapore’s model of development: is it transferable? ”, in Rowen , H.S. (Ed.), Behind East Asian Growth: The Political and Social Foundations of Prosperity , Routledge , London , Chapter 5 , pp. 105 - 125 .

Quah , J.S.T. ( 2007 ), Combating Corruption Singapore-Style: Lessons for other Asian Countries , School of Law, University of Maryland , Baltimore, MD .

Quah , J.S.T. ( 2010 ), Public Administration Singapore-Style , Emerald Group Publishing , Bingley .

Quah , J.S.T. ( 2011 ), “ Innovation in public governance in Singapore: solving the housing shortage and curbing corruption ”, in Anttiroiko , A.-V. , Bailey , S.J. and Valkama , P. (Eds), Innovative Trends in Public Governance in Asia , IOS Press , Amsterdam , pp. 121 - 136 .

Quah , J.S.T. ( 2015a ), “ Singapore’s Corrupt Practices Investigation Bureau: four suggestions for enhancing its effectiveness ”, Asian Education and Development Studies , Vol. 4 No. 1 , pp. 76 - 100 .

Quah , J.S.T. ( 2015b ), “ Lee Kuan Yew’s enduring legacy of good governance in Singapore, 1959–2015 ”, Asian Education and Development Studies , Vol. 4 No. 4 , pp. 374 - 393 .

Quah , J.S.T. ( 2015c ), Hunting the Corrupt ‘Tigers’ and ‘Flies’ in China: An Evaluation of Xi Jinping’s Anti-Corruption Campaign (November 2012 to March 2015) , Carey School of Law, University of Maryland , Baltimore, MD .

Quah , J.S.T. ( 2016a ), “ The role of the public bureaucracy in policy implementation in five ASEAN countries: a comparative overview ”, in Quah , J.S.T. (Ed.), The Role of the Public Bureaucracy in Policy Implementation in Five ASEAN Countries , Chapter 1 , Cambridge University Press , Cambridge , pp. 1 - 97 .

Quah , J.S.T. ( 2016b ), “ Singapore’s success in combating corruption: four lessons for China ”, American Journal of Chinese Studies , Vol. 23 No. 2 , pp. 187 - 209 .

Quah , J.S.T. ( 2017 ), “ Singapore’s success in combating corruption: lessons for policy makers ”, Asian Education and Development Studies , Vol. 6 No. 3 , pp. 263 - 274 .

Quah , S.R. ( 1995 ), “ Confucianism, pragmatic acculturation, social discipline, and productivity: notes from Singapore ”, APO Productivity Journal , pp. 42 - 64 .

Republic of Singapore ( 1994 ), Competitive Salaries for Competent and Honest Government: Benchmarks for Ministers and Senior Public Officers, Command 13 of 1994 , white paper presented to the Parliament of Singapore, Prime Minister’s Office, Singapore, 21 October .

Republic of Singapore ( 2010/2017 ), Singapore Budget 2010–2017: Annex to the Expenditure Estimates , Budget Division, Ministry of Finance , Singapore .

Republic of Singapore ( 2012 ), White Paper: Salaries for a Capable and Committed Government , Command 1 of 2012, Prime Minister’s Office, Singapore, 10 January .

Republic of Singapore ( 2018 ), Singapore Government Directory , available at: www.gov.sg/sgdi/ministries/ and www.gov.sg/sgdi/statutory-boards (accessed 24 January 2018 ).

Rose , R. ( 2005 ), Learning from Comparative Public Policy: A Practical Guide , Routledge , London .

Rose-Ackerman , S. and Palifka , B.J. ( 2016 ), Corruption and Government: Causes, Consequences, and Reform , 2nd ed. , Cambridge University Press , New York, NY .

Samuels , R.J. ( 2003 ), Machiavelli’s Children: Leaders and Their Legacies in Italy and Japan , Cornell University Press , Ithaca, NY .

Schein , E.H. ( 1996 ), Strategic Pragmatism: The Culture of Singapore’s Economic Development Board , MIT Press , Cambridge, MA .

Schwab , K. (Ed) ( 2017 ), The Global Competitiveness Report 2017–2018 , World Economic Forum , Geneva .

Seow , B.Y. ( 2018 ), “ Govt keeps ministerial salaries unchanged ”, Straits Times, 2 March, p. A4 .

Soh , K.H. ( 2008 ), “ Corruption enforcement ”, paper presented at the Second Seminar of the International Association of Anti-Corruption Associations, Chongqing, 17-18 May .

Stowe , K. ( 1996 ), “ Good piano won’t play bad music ”, in Barberis , P. (Ed.), The Whitehall Reader: The UK’s Administrative Machine in Action , Chapter 3.6 , Open University Press , Buckingham , pp. 86 - 91 .

Tan , A.L. ( 1999 ), “ The experience of Singapore in combating corruption ”, in Stapenhurst , R. and Kpundeh , S.J. (Eds), Curbing Corruption: Toward a Model for Building National Integrity , World Bank , Washington, DC , pp. 59 - 66 .

Teng , A. ( 2015 ), “ Singapore tops world’s most comprehensive education rankings ”, Straits Times , 14 May, p. A1 .

Transparency International ( 2017 ), Corruption Perceptions Index 2016 , Transparency International , Berlin , available at: www.transparency.org/news/feature/corruption_perceptions_index_2016 (accessed 25 January 2017 ).

Transparency International ( 2018 ), Corruption Perceptions Index 2017 , Transparency International , Berlin .

Turnbull , C.M. ( 1977 ), A History of Singapore 1819–1975 , Oxford University Press , Kuala Lumpur .

Vogel , E.F. ( 2011 ), Deng Xiaoping and the Transformation of China , Harvard University Press , Cambridge, MA .

Wang , Q. ( 2014 ), “ Anti-corruption chief says China should learn from Hong Kong, Singapore ”, Ejinsight , 27 August .

World Bank ( 2017 ), Worldwide Governance Indicators 2016 , World Bank , Washington, DC , available at: http://info.worldbank.org/governance/wgi/#reports (accessed 8 October 2017 ).

Corresponding author

About the author.

Jon S.T. Quah is a retired Professor of Political Science at the National University of Singapore and anti-corruption consultant based in Singapore. He has published widely on corruption and governance in Asian countries. His latest books include: Combating Asian Corruption: Enhancing the Effectiveness of Anti-Corruption Agencies (2017); The Role of the Public Bureaucracy in Policy Implementation in Five ASEAN Countries (2016); Hunting the Corrupt “Tigers” and “Flies” in China: An Evaluation of Xi Jinping’s Anti-Corruption Campaign (November 2012 to March 2015) (2015); Different Paths to Curbing Corruption: Lessons from Denmark, Finland, Hong Kong, New Zealand and Singapore (2013); and Curbing Corruption in Asian Countries: An Impossible Dream? (2011, 2013).

Related articles

We’re listening — tell us what you think, something didn’t work….

Report bugs here

All feedback is valuable