The magic of mariachi music in school

Staffing shortages undermine transitional kindergarten rollout

Student journalists on the frontlines of protest coverage

How earning a college degree put four California men on a path from prison to new lives | Documentary

Patrick Acuña’s journey from prison to UC Irvine | Video

Family reunited after four years separated by Trump-era immigration policy

Calling the cops: Policing in California schools

Black teachers: How to recruit them and make them stay

Lessons in higher education: California and beyond

Keeping California public university options open

Superintendents: Well-paid and walking away

The debt to degree connection

May 14, 2024

Getting California kids to read: What will it take?

April 24, 2024

Is dual admission a solution to California’s broken transfer system?

How student-driven goals make learning more meaningful

Chase Nordengren

January 12, 2022.

The increase in conversations about how to serve the overall needs of students, including their social and emotional needs, is one of the silver linings of education during the pandemic.

While the energy around what’s often called “social-emotional learning” has been growing in education circles for some time, the pandemic has required us to think more deeply and more comprehensively about how the outside world can impact all students’ ability to learn.

With this added focus, however, comes a different danger: the danger of painting all students with a broad brush, assuming one single curriculum or set of supports can meet a variety of different learning needs.

Educators will need to bring a whole toolbox to bear to support students who come out of this pandemic with a variety of hardships, needs and abilities.

One tool in that toolbox is student goal setting.

In goal setting, students and teachers work together to set meaningful short-term targets for learning, monitor students’ progress toward those targets, and adjust students’ learning strategies to better meet those goals. While goals can provide many well-documented academic benefits, they can also serve a critical role in student well-being: providing the sense of meaning and belonging students need to fully engage.

Finding the energy and focus necessary to learn can be hard during any period, but it is harder now for many students who are experiencing irregular school schedules, struggling with economic problems at home or worrying about their own health or the health of their families.

Academic resilience — our ability to see ourselves as capable of learning after hardships like these — is not a fixed quality. Instead, it depends on what we’re being asked to learn and the attitudes we’re being encouraged to have about that learning. Goal setting gives teachers a framework that lets them communicate what students are focused on, how they’ll achieve that objective and why that objective should matter.

Students are most motivated by goals that are both attainable and relevant to them.

Attainability is crucial to resilience: No one should be repeatedly asked to achieve something they’re unlikely to achieve because they will get discouraged when they don’t see success. Equally important, however, is finding learning that is relevant to students’ interests: the subjects they care about, the kinds of work they like to do or the types of people they want to become. In fact, attainability and relevance go hand in hand: Students are capable of achieving more when content is tailored specifically to them .

One of the easiest ways to make goals relevant for students is to provide them ample opportunities for choice.

Too often, a student’s goals are driven exclusively by algorithms, focused just on long-term improvement on test scores for themselves or a full class.

There’s nothing wrong with these goals in and of themselves. However, to motivate students to achieve those goals, they also need short-term goals that describe the day-to-day work they’ll do to build toward academic proficiency. These choices shouldn’t just be about the group a student is in: They should be authentic opportunities to pick what they will focus on within the broader area of work being done by the whole class.

Goal setting doesn’t look the same from teacher to teacher or even student to student. There are a variety of approaches educators can take to setting goals, many of which have tremendous merit. One thing these effective strategies share in common is that they provide teachers the time to understand a student’s unique needs. Frequent interaction with students around their goals allows teachers to serve as mentors, working directly with each student on a set of goals that are attainable, related to their interests and provide meaning.

Another critical element to effective goals is building student autonomy. The most important part of students’ well-being in school is their sense of well-being as learners — whether they feel they have a role to play in a community of learning.

School has historically not been a place where students feel in control. During the pandemic, students have lost control of the rest of their lives: who they spend time with, what activities they get to engage in, where they can go and what they can do there.

Involving students in goal setting and tailoring their goals to their interests and individual needs can help students feel more connected to meaningful learning. This student-driven approach provides an opportunity to bring choices back to learning in ways that help empower students to feel they belong with each other and are capable, creative scholars.

Chase Nordengren, Ph.D. , is a senior research scientist at NWEA, a not-for-profit organization that creates assessments for school districts and author of Step Into Student Goal Setting: A Path to Growth, Motivation, and Agency .

The opinions in this commentary are those of the author. If you would like to submit a commentary, please review our guidelines and contact us .

Share Article

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. required fields are marked * *.

Click here to cancel reply.

XHTML: You can use these tags: <a href="" title=""> <abbr title=""> <acronym title=""> <b> <blockquote cite=""> <cite> <code> <del datetime=""> <em> <i> <q cite=""> <s> <strike> <strong>

Comments Policy

We welcome your comments. All comments are moderated for civility, relevance and other considerations. Click here for EdSource's Comments Policy .

EdSource Special Reports

Going police-free is tough and ongoing, Oakland schools find

Oakland Unified remains committed to the idea that disbanding its own police force can work. Staff are trained to call the cops as a last resort.

When California schools summon police

EdSource investigation describes the vast police presence in K-12 schools across California.

Call records show vast police presence in California schools

A database of nearly 46,000 police call records offers a rare view into the daily calls for police service by schools across California.

Calling the Cops Database

Explore an unprecedented trove of police call data for 852 school addresses covered by 164 local police, sheriffs and school-district police.

EdSource in your inbox!

Stay ahead of the latest developments on education in California and nationally from early childhood to college and beyond. Sign up for EdSource’s no-cost daily email.

Stay informed with our daily newsletter

You are using an outdated browser. Upgrade your browser today or install Google Chrome Frame to better experience this site.

- Professional learning

Teach. Learn. Grow.

Teach. learn. grow. the education blog.

Read the latest in student goal setting guidance

How to create opportunities for self-directed learning

How teaching multiple standards can improve learning and get you through your curriculum

Lessons from the field: 4 tips for building an instructional coaching program from Columbus City Schools

Helping students grow

Students continue to rebound from pandemic school closures. NWEA® and Learning Heroes experts talk about how best to support them here on our blog, Teach. Learn. Grow.

See the post

Put the science of reading into action

The science of reading is not a buzzword. It’s the converging evidence of what matters and what works in literacy instruction. We can help you make it part of your practice.

Get the guide

Support teachers with PL

High-quality professional learning can help teachers feel invested—and supported—in their work.

Read the article

STAY CURRENT by subscribing to our newsletter

You are now signed up to receive our newsletter containing the latest news, blogs, and resources from nwea..

- Our Mission

Guiding Students to Set Academic Goals

Encouraging students to set goals for themselves—the first phase of self-regulated learning—helps them develop a growth mindset.

“Setting goals is the first step in turning the invisible into the visible.” —Tony Robbins

Many students may not necessarily have the tools to set academic goals and lack strategies to enact change and work toward those goals. Teachers can provide structure to help students set academic goals that are realistic and appropriate as well as achievable. It is important to note that goal setting is not just an activity for the beginning of the school year, but an ongoing process.

Setting academic goals is the first phase of self-regulated learning. Irrespective of the model proposed by leading researchers such as Barry Zimmerman , self-regulated learning always begins with a goal-planning phase. Goal setting is an essential component for growth and development in our students for several reasons:

- It personalizes the learning process based on their needs.

- It creates intention and motivation that empowers students.

- It establishes accountability to shift responsibility to students.

- It provides a foundation for students to advocate for their needs.

Goal setting can be done at any age—as long as it is age appropriate. Teaching the skill of goal setting coupled with reflecting and revising goals can give students the self-regulated learning tools for a growth mindset toward academic development.

With students as young as kindergarten, more scaffolding is needed. At the beginning of each day, students can select an emoji or picture that represents some action from a predetermined list of possible options. If teaching virtually, students can do this at the beginning of the session. If teaching in person, students can perhaps tape their goal to their desk or table area or perhaps a chart displayed in the classroom. The class can spend a few moments discussing goals and what actions they can do to achieve those goals. Teachers can invite other students to make suggestions for their peers. At the end of the day, allow students to rate themselves with stars and to think about how they could do things differently for the next day.

Upper Elementary and Middle School

For students who are slightly older and able to write, an excellent way to develop the habit of creating, planning, and reflecting on goals can be done through the use of short-term daily goals using sticky notes. At the beginning of the day, students take a few minutes to imagine some task, behavior, or skill they want to focus their intentions on for that specific day. Let the students keep the notes somewhere visible, so they can refer back to the goal throughout the day. Include class conversations with either a partner, a small group, or the whole class at the beginning and end of the day. Focus on the achievement of the goal, but suggest growth mindset strategies to focus on the wins as well as necessary changes for further improvement.

Once students have more advanced writing skills, it may be useful for them to keep a chart or table of their goals in a logbook. Students record in the morning, not only the goals but an action plan, and then reflect on strategies for improvement at the end of the day. At the end of each week, allow students time to reflect on their goals for the next week with structured prompts such as the following:

- What do you think about the choices in goals for the week? (Were they realistic and appropriate? Were they the most needed for growth at this time?)

- How did you progress toward your goals? (Did you have clear, actionable steps?)

- What were some of the wins for the week?

- What are some ways you can continue to improve on your development of these goals?

While a logbook is functional, it can be a more motivating experience to allow students to engage in creativity and personalization. Allow them to have fun with the process and create a goal journey map. They identify a goal, which is the end of the map. They also identify different benchmarks or steps to complete along the path or journey toward that goal. Students then have a visual representation of the progress of their journey.

High School

For high school students, l use a reflection sheet after each unit or chapter to create a regular habit of revisiting goals. Ask students the following questions:

What were the wins for this chapter or unit? In other words, what things did you do well or what areas did you improve?

- What are some areas that you can improve upon? What are some areas that need more attention or focus? What could you do differently?

- What specific and concrete actions can you do?

- How can you advocate for yourself? In other words, how can your teacher, your peers, or others guide you toward your goal?

I always begin new units with an independent work day or two. During this time, the students are working on their reading skills, while I conference with their classmates independently.

Goal setting can help with classroom management and academic performance. It allows students to become more aware of expectations and concrete methods to achieve an outcome. It scaffolds the process, making it more manageable. With goal setting that is reflective and iterative, students establish a growth mindset as they engage in monitoring of their progress and reflecting on it as outlined by Zimmerman and Dale Schunk .

Goal-Setting Is Linked to Higher Achievement

Five research-based ways to help children and teens attain their goals..

Posted March 14, 2018 | Reviewed by Ekua Hagan

- What Is Motivation?

- Find a therapist near me

If you are an employed adult, you know that most organizations have written goals and objectives. That’s because goal-setting is a common practice in the workplace—and for good reason. Written goals provide a road map by which employees can measure their efforts and see how they contribute to the success of work teams and ultimately, to their companies.

In the same way, goal-setting helps motivate athletes, entrepreneurs, and individuals to achieve at higher levels of difficulty.

But goal-setting isn’t just for adults. In fact, being goal-oriented is a critical part of how children learn to become resourceful, which is defined as one’s ability to find and use available resources to solve problems and shape the future.

“Goal setters see future possibilities and the big picture,” says Rick McDaniel in a Huffington Post article . He discusses the important difference between being a goal setter and problem solver, the latter often getting bogged down in roadblocks. “Goal setters,” he says, “are comfortable with risk, prefer innovation , and are energized by change.”

Research has uncovered many key aspects of goal setting theory and its link to success (Kleingeld, et al, 2011). Setting goals is linked with self-confidence , motivation, and autonomy (Locke & Lathan, 2006). A 2015 study by psychologist Gail Matthews showed when people wrote down their goals, they were 33 percent more successful in achieving them than those who formulated outcomes in their heads.

Children learn to be resourceful through the practice of being goal-directed. In an article at Edutopia , teachers learn that fostering resourcefulness involves encouraging students to plan, strategize, prioritize, set goals, seek resources, and monitor their progress.

In similar ways, parents teach resourcefulness when they walk beside children through the everyday practice of being goal-directed rather than attempting to set objectives and problem-solving for kids.

The common approach that applies to both parents and educators is to involve children in their own goal-setting and decision-making . This promotes independence and collaboration with adults simultaneously.

The following strategies apply the research on goal-setting at home, in the classroom, or on the sports field.

Five Ways to Help Children Set and Achieve Goals

Children and teens become effective goal-setters when they understand and develop five action-oriented behaviors and incorporate these actions with each goal set.

- Put goals in writing. Goals that are written are concrete and motivational. Making progress toward written goals increases feelings of success and well-being. Using a goal-setting template can help children track their successes. A goal-setting smartphone app may motivate tech-savvy children even more. Some apps have gaming features that make goal-setting a fun way to achieve results and build new habits.

- Self-commit. For a goal to be motivating to a child, it must give meaning to a mental or physical action to which a child feels committed. This self-commitment becomes a key element in self-regulation , a child’s ability to monitor, control, and alter his own behaviors. This doesn’t mean that parents or teachers should not be involved in goal-setting. In fact, adults can serve as goal facilitators—helping kids see options, asking core questions, and providing supportive feedback.

- Be specific. Goals must be much more specific than raising a grade or improving performance on the soccer field. Here’s a simple formula. 1) I will [raise my grade in algebra from a C to a B]; 2) By doing what? [regular homework, and spending time with an online algebra program or game]; 3) When? How? With Whom? [increase daily algebra homework by 15 minutes to include a fun online interactive algebra practice; spend 15 fewer minutes on social media ; get support from teacher/tutor for things that are not understood]; 4) Measured by [increased time spent; improved weekly test scores].

- Stretch for difficulty. Goals should always be challenging enough to be attainable, but not so challenging that they become sources of major setbacks. When working with a child on goal-setting, listen to what they think they can achieve rather than what you want them to achieve.

- Seek feedback and support. Part of the fun and motivation of setting goals is working on them in a supportive group environment. Even though goals are often individual in nature, children should be able to recognize how their goal is tied to their family values, the aspirations of a sports team, or the aim of a specific curriculum. When they understand this connection, they feel more open to seeking feedback and receiving support from adults. When goals are achieved, it’s time to celebrate with others!

Kleingeld, A., van Mierlo, H., & Arends, L. (2011). The effect of goal setting on group performance: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 96(6), 1289-1304.

Locke, E. A., & Latham, G. P. (2006). New Directions in Goal-Setting Theory. Current Directions in Psychological Science , 15(5), 265-268.

Matthews, G. (2015). Goal Research Summary. Paper presented at the 9th Annual International Conference of the Psychology Research Unit of Athens Institute for Education and Research (ATINER), Athens, Greece.

Marilyn Price-Mitchell, Ph.D., is an Institute for Social Innovation Fellow at Fielding Graduate University and author of Tomorrow’s Change Makers.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Online Therapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Self Tests NEW

- Therapy Center

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

At any moment, someone’s aggravating behavior or our own bad luck can set us off on an emotional spiral that threatens to derail our entire day. Here’s how we can face our triggers with less reactivity so that we can get on with our lives.

- Emotional Intelligence

- Gaslighting

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

- About PDK International

- About Kappan

- Issue Archive

- Permissions

- About The Grade

- Writers Guidelines

- Upcoming Themes

- Artist Guidelines

- Subscribe to Kappan

Select Page

Goal-setting practices that support a learning culture

By Chase Nordengren | Jul 15, 2019 | Feature Article

Having students set their own goals and monitor their progress is most effective when teachers are able to create a culture, rather than following prescriptive steps.

G etting students to understand where they are in their learning is a steep challenge with potential for a huge payoff when you are seeking to build school and classroom cultures where improvement and growth flourish. So what can educators do to help students care about their learning and become more invested in their own success? In particular, how can teachers use assessments to motivate students without discouraging or stereotyping them?

Goal setting — one of many forms of student-involved data use (Jimerson & Reames , 2015) — gets students involved in reviewing their assessment results, working with their teachers to set reasonable but aspirational goals for improvement, and continuing to drive their learning with frequent reference to those goals. When implemented well, these goal-setting practices have a significant positive influence on student outcomes and school cultures ( Leithwood & Sun, 2018; Moeller, Theiler, & Wu, 2012).

Not surprisingly, students do better when they feel in control of their learning. Robert Marzano’s (2009) review of research, for example, finds goal setting can produce student learning gains of between 18 and 41 percentile points. Across a variety of grade levels, subject areas, and studies, effective goal-setting practices help students focus on specific outcomes, encourage them to seek academic challenges, and make clear the connection between immediate tasks and future accomplishments ( Stronge & Grant, 2014). Still, not just any form of goal setting will drive learning. Goal setting must tap into four elements of tasks that motivate students: providing them opportunities to build competence, giving them control or autonomy, cultivating interest, and altering their perceptions of their own abilities (Usher & Kober , 2012). Without these elements, the positive effects of goal setting are lost.

Goals can and do look very different from student to student. Any academic or behavioral outcome — from showing proficiency in multidigit multiplication, to identifying and correctly using question words, to reducing absences and tardies — can play a role in a student’s goals. However, the process by which goals are set, monitored, and reviewed is key to ensuring goal setting is successful.

The process by which goals are set, monitored, and reviewed is key in ensuring goal setting is successful.

In particular, research calls on teachers to use goal setting to cultivate a mastery orientation, where students focus on overcoming personal challenges or learning as much as possible, instead of approaches driven by hitting specific performance targets or avoiding failure (Wolters, 2004). These orientations are fungible: Even when teachers don’t directly set goals, they convey attitudes and provide directives on how goals should be set and interpreted (Marsh, Farrell, & Bertrand, 2014). And, like any element of a school culture, the attitudes teachers convey are heavily influenced by how the rest of the school system thinks about using data and the ways administrators expect teachers to interpret assessment results ( Schildkamp & Lai, 2013). Goal setting in isolation, then, is far less likely to be successful than when it is part of a culture where goal setting is common, goals are linked to learning, and students continue goal setting as they change teachers and grades.

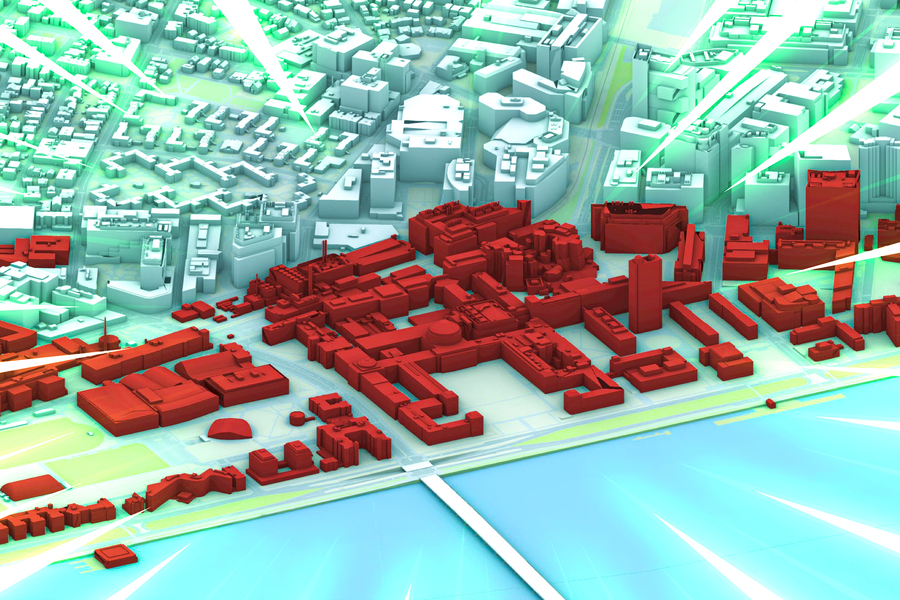

As a researcher with NWEA, I have been learning from thousands of schools and districts in the United States and around the world who are using our MAP Growth assessment to help students understand what they know and aspire to learn more. The story of one of these systems, which I call Walnut Hills in this article, illustrates how emphasizing goal setting while providing extensive teacher autonomy allows the mastery orientation to flourish and has a significant influence on school culture.

From mandate to ownership

For several years, Walnut Hills, a medium-size suburban district in the midwestern U.S., has been using NWEA’s MAP Growth assessment to measure student learning. Further, in classrooms across the district, teachers and students have implemented a research-based model of goal setting, in which they take concrete steps to discuss goals, set new ones, and define a learning path for meeting them; the district has linked this goal-setting process to its larger strategy for personalized learning. The deliberate nature of this process, combined with the apparent high level of support from the district and a set of strong cultural expectations for students, teachers, and administrators, make this an interesting case for understanding how to make goal setting part of schools’ organizational culture.

The work got off to a slow start, though. At first, the district required teachers to use the same goal-setting worksheets across grade levels, which made the process particularly difficult for younger students to understand. And while there was no problem with student buy-in to the goal-setting process, most schools reserved time for that process only in the days following major tests. Between tests, teachers rarely used formative data to help students define their goals and, perhaps most important, they rarely checked in with students about their goals.

Still, the teachers strongly embraced the program’s fundamental values: personalized learning, formative assessment, and student ownership of learning. Over time, then, they found ways to adapt the model to their needs, creating a range of more flexible, classroom-built goal-setting practices that, while they differed somewhat from teacher to teacher, retained the spirit and the research DNA that had driven adoption of the original model.

For example, once it became apparent that her kindergarten and 1st-grade students did not understand the prescribed worksheets, Leslie (all names are pseudonyms) tried creating her own worksheets. This was an improvement, but she still felt “like some of my kids were going through the motions” of goal setting without really understanding why they were doing it. So, to make the process more concrete, she decided to focus on explaining the relevance of goals in daily life, using student-friendly language and breaking the assessment data down into pieces that made sense to them. Over time, she recalled, her students gradually became more accustomed to talking about and setting their learning goals.

Similarly, Cassandra, a high school teacher, first encountered the district’s goal-setting strategy through a series of professional development workshops, and she knew right away that she would have to adapt the model. The approach was “very complicated,” she said, and it happened only alongside testing windows. So she turned to best practices from the research on adult goal setting, with an eye to how it could apply to her students. “It needs to be very simple, it needs to be targeted, it needs to be short term, and there need to be periodic check-ins,” she concluded. By applying these changes and seeking regular data points relevant to students’ lives, Cassandra created an age-appropriate goal-setting practice focused on improving student attendance, study behaviors, and credit attainment.

Like Leslie and Cassandra, other teachers in Walnut Hills now use regular student conferencing, encourage student involvement in setting goals and checkpoints, and rely on multiple forms of assessment data, including graphics and other visual representations, to keep student goals front and center in their classrooms. These teachers had seen the benefits of goal setting through the model and sought to boil it down to its essential elements. Making goal-setting conversations simple, targeted, and short term made them part of the day-to-day instructional life of teachers and students, rather than just another reform mandated by the district.

Making goal setting work

While each teacher I observed in Walnut Hills took a slightly different approach to goal setting, their shared practices paint a picture of an organic and dynamic process that maintains consistency for students from kindergarten through graduation:

Start early.

Goal setting in Walnut Hills starts as early as kindergarten. Since these students may not be ready at first to think about individual academic goals, teachers begin with classwide goals for behavior and developing skills. Then they move on to setting simple individual goals, such as learning a set of letters or spending a certain amount of time on task. Through the process of setting goals for their class and for themselves, young children learn to understand what a goal is and how it contributes to learning.

More important than the substance of goals for young students, however, is the process. “We talk about why we make a goal, what is the purpose of it, how it guides your learning, and how proud you are when you hit that goal,” says Leslie. For her, the objective of goal setting with the youngest kids is to provide a set of norms and expectations that prepare them to set specific and measurable goals in later grades. Jodi, an early grades teacher at another school, echoed this idea: “We see a lot of success by starting so young that by the older grades . . . they can start to do a lot more of that on their own.”

Do it often.

Each of the teachers I spoke with in Walnut Hills engaged their students in setting short-term goals, usually lasting no longer than four to six weeks. Short-term goals invited frequent check-ins with students, at least weekly if not daily. In turn, these check-ins allowed for frequent revision of goals based on student progress, preventing students from feeling discouraged: With several opportunities to observe progress, a goal not yet met becomes a goal that can be met in the future with additional effort.

The goal-setting process often begins with a conference in which students answer questions like those Karen used: “What is an appropriate goal?” and “Why do we think this is an appropriate goal for you?” During regular check-ins, teachers confer with students about current work, its relationship to their goals, and strategies they use to improve learning. A goal-setting conference at the end of the process facilitates reflection on learning, answering questions like these from Karen: “What do you notice about your work from the beginning till now?” and “How do you feel like you grew?”

Maximizing the frequency of goal-setting check-ins may require relaxing more complex or drawn-out procedures in favor of quick conversations focused on a handful of key questions. The Walnut Hills teachers note that whatever they’ve lost by moving away from the initial structured model toward something more heterogenous is more than made up for by the opportunity they now have to reinforce growth mindsets, practice academic conversations, and make regular individual contact with each student.

Make it visual.

Goal-setting teachers rely on a variety of visual tools and artifacts to help solidify their goal-setting culture. At a whole-class level, these may include anchor charts referencing classroom goals or graphs showing student progress toward particular learning goals or assessment targets (without showing individual student names). On an individual level, these can include data notebooks, personalized learning plans (either physical or through a digital system that can be shared with parents and other teachers), and goal-setting worksheets.

The teacher-created worksheets I observed have much in common:

- First, they focus on identifying the goal and setting a firm end date for achieving it. If students have experience with SMART (specific, measurable, attainable, relevant, and time-bound) goals, the worksheets may reference those guidelines.

- Second, worksheets ask students to describe actionable steps to get to their goal. These can include a certain amount of mathematics practice per week, a certain number of pages to read each night, or even a set of behaviors like coming to school on time. These steps enable students to truly tailor the goal to their own learning. As Carla observes, “They’ve got their picture, they take a learning style inventory, they pace their results” and use other tools to identify steps that are achievable for them.

- Finally, goal-setting artifacts ask students to describe evidence they have reached their goal. This can include reflection, essays or other work products, or feedback from teachers or peers. All teachers I spoke with emphasized that test scores provide only one piece of a broader set of evidence of learning, but they could support students motivated by seeing their progress on a scale, so long as those results were connected in concrete ways to learning objectives. In requiring evidence of learning, the objective of these educators was to provide multiple avenues through which students could demonstrate their own improvement in ways that motivated them.

Create personal relevance.

Several teachers, like Carla, noted that starting goal-setting conversations around personal goals provided an opportunity to illustrate the benefits of goal setting:

I have them think about something they’re struggling with, whether it’s getting their homework done or getting their chores done or anything. And then we start looking at, “OK, what could we do to fix that?” And so we set a goal around that and then that leads more into, “Now let’s focus on the school aspect. What are things that you’re struggling with at school?”

Many teachers referenced goals they had set in their personal lives as an opportunity to make goal setting more relevant. For Nancy, a goal-setting conversation begins with, “What do you as a person want to be? And then what’s the area, academically, you want us to help you with?”

The need for personal relevance also underlines the significance of relationship building in ensuring goal-setting success. Conferring with students, Kerry said, provides “more bang for your buck” by allowing you to both build relationships with students and learn their specific, individualized learning needs. Even when a goal-setting conversation focuses on improving a grade or reaching an arbitrary milestone, goal-setting conversations can help students recognize, as Cassandra said, “that they have some control over their grade.” However, none of the teachers I spoke with used goal success as a factor in student grades. Instead, goal setting served as a tool to more clearly illustrate the relationship between learning activities, mastery, and a final grade, encouraging student and teacher to engage in conversations around performance before report cards came due.

Center student choice.

Finally, student ownership of learning is maximized where students feel a sense of agency and choice. Goal-setting teachers serve as directors of learning: breaking larger goals down into skill areas, suggesting goals based on skills students are missing, and outlining the steps necessary to get to a particular goal, but ultimately leaving selection of the goal itself in the hands of students. Even for young students who are less capable of self-reflection, the appearance of choice is key. Leslie said, “I might give them two goals, or three. Then I kind of let them pick [even though] you’re still providing the goal for them.”

These early choices reinforce a culture of student choice that pays off as students become more self-aware, as Carla explained: “I’m kind of giving them the goal, so to speak, but eventually they’ll start setting their own . . . you actually sit down and listen to a kid who has a goal that they want to achieve and help them figure out the steps to get there, because that’s where they are stuck.” In goal-setting conversations like these, the teacher still plays an active role, ensuring goals are specific, measurable, and connected to learning. They also play an important continuous role in celebrating accomplishments to promote persistence and encourage confidence. Ultimately, however, the aim of goal setting as a schoolwide cultural practice is to provide a gradual release toward self-sufficient goal setting. Karen said, “I think the best goal-setting conferences are the ones where students are able to look at their work, look at the metric piece, and actually be able to say, ‘You know what? I’m not there yet,’ independently but [also to recognize] ‘I can be there. This is what I need to do, though.’ ”

Bringing it all together

Goal setting by and for students helps form the glue that binds assessment events together. Through goal setting, students develop the skills to reflect on their learning and turn their understanding of their current knowledge and skills into a drive to learn more. In classrooms exemplifying student ownership of learning, “Students know where they are going, where they are, and how to close the gap” (Chan et al., 2014, p. 112). The goal-setting practices I observed among teachers in Walnut Hills focus on identifying these three touch points, returning to them regularly, and empowering students to play an equal role in identifying what they will learn and the processes that will get them there.

Student-owned goal setting, undertaken through a diversity of teaching styles and approaches, is a critical strategy for any school or district looking to create a culture of lifelong learning.

Rick Stiggins (2002) refers to the best formative assessment as “assessment for learning,” a source of comfortable motivation for students to fulfill their ambitions instead of a source of anxiety and fear. In tandem with such assessment, effective goal setting engages students in understanding how learning is measured, the myriad ways it can manifest, and the direct relationship between what is learned in school and what students want for their lives. Student-owned goal setting, undertaken through a diversity of teaching styles and approaches, is a critical strategy for any school or district looking to create a culture of lifelong learning.

The most effective teachers model the behavior they expect from their students: They set goals for themselves, monitor progress against them frequently, and reflect on how their daily learning matches their goals. However, administrators must also leverage the example their teachers set to encourage broader organizational shifts that ensure students engage in continuous goal setting between grades and schools, making the practice part of the standard operating procedure of the district.

Chan, P.E., Graham-Day, K.J., Ressa, V.A., Peters, M.T., & Konrad, M. (2014). Beyond involvement: Promoting student ownership of learning in classrooms. Intervention in School and Clinic , 50 (2), 105-113.

Jimerson, J.B. & Reames, E. (2015). Student-involved data use: Establishing the evidence base. Journal of Educational Change , 16 (3), 281-304.

Leithwood, K. & Sun, J. (2018). Academic culture: A promising mediator of school leaders’ influence on student learning. Journal of Educational Administration , 56 (3).

Marsh, J.A., Farrell, C.C., & Bertrand, M. (2014). Trickle-down accountability: How middle school teachers engage students in data use. Educational Policy , 30 (2), 243-280.

Marzano, R.J. (2009). Designing and teaching learning goals and objectives: Classroom strategies that work . Denver, CO: Marzano Research Laboratory.

Moeller, A.J., Theiler, J.M., & Wu, C. (2012). Goal setting and student achievement: A longitudinal study. Modern Language Journal , 96 (2), 153-169.

Schildkamp, K. & Lai, M.K. (2013). Conclusions and a Data Use Framework. In K. Schildkamp, M.K. Lai, & L. Earl (Eds.), Data-based Decision Making in Education: Challenges and Opportunities (pp. 177-191). Netherlands: Springer.

Stiggins, R.J. (2002). Assessment crisis: The absence of assessment for learning. Phi Delta Kappan , 83 (10), 758-765.

Stronge, J.H. & Grant, L.W. (2014). Student achievement goal setting . New York: Taylor & Francis.

Usher, A. & Kober, N. (2012). Student motivation: An overlooked piece of school reform. Washington, DC: Center for Education Policy.

Wolters, C.A. (2004). Advancing achievement goal theory: Using goal structures and goal orientations to predict students’ motivation, cognition, and achievement. Journal of Educational Psychology , 96 (2), 236-250.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Chase Nordengren

Chase Nordengren is the principal research lead for effective instructional strategies at NWEA and the author of Step Into Student Goal Setting: A Path to Growth, Motivation, and Agency .

Related Posts

Helping preservice teachers separate fact from fiction

November 25, 2019

Listening to formerly homeless youth

November 23, 2020

The Affordable Care Act and school-based mental health services

December 1, 2014

Japan’s innovative approach to professional learning

November 26, 2018

Recent Posts

The Importance, Benefits, and Value of Goal Setting

We all know that setting goals is important, but we often don’t realize how important they are as we continue to move through life.

Goal setting does not have to be boring. There are many benefits and advantages to having a set of goals to work towards.

Setting goals helps trigger new behaviors, helps guides your focus and helps you sustain that momentum in life.

Goals also help align your focus and promote a sense of self-mastery. In the end, you can’t manage what you don’t measure and you can’t improve upon something that you don’t properly manage. Setting goals can help you do all of that and more.

In this article, we will review the importance and value of goal setting as well as the many benefits.

We will also look at how goal setting can lead to greater success and performance. Setting goals not only motivates us, but can also improve our mental health and our level of personal and professional success.

Before you continue, we thought you might like to download our three Goal Achievement Exercises for free . These detailed, science-based exercises will help you or your clients create actionable goals and master techniques to create lasting behavior change.

This Article Contains:

The importance and value of goal setting, why set goals in life, what are the benefits of goal setting, 5 proven ways goal setting is effective, how can goal setting improve performance, how goal setting motivates individuals, why is goal setting important for students, a look at the importance of goal setting in mental health, the importance of goal setting in business and organizations, 10 quotes on the value and importance of setting goals, a take-home message.

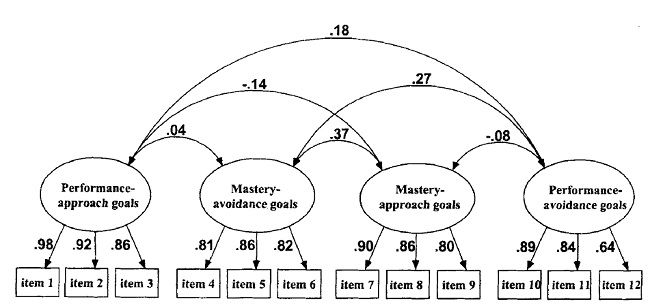

Up until 2001, goals were divided into three types or groups (Elliot & McGregor, 2001):

- Mastery goals

- Performance-approach goals

- Performance-avoidance goals

A mastery goal is a goal someone sets to accomplish or master something such as “ I will score higher in this event next time .”

A performance-approach goal is a goal where someone tries to do better than his or her peers. This type of goal could be a goal to look better by losing 5 pounds or getting a better performance review.

A performance-avoidance goal is a goal where someone tries to avoid doing worse than their peers such as a goal to avoid negative feedback.

Research done by Elliot and McGregor in 2001 changed these assumptions. Until this study was published, it was assumed that mastery goals were the best and performance-approach goals were at times good, and other times bad. Performance-avoidance goals were deemed the worst, and, in fact, bad.

The implied assumption, as a result of this, was that there were no bad mastery goals or mastery-avoidance goals.

Elliot and McGregor’s study challenged those assumptions by proving that master-avoidance goals do exist and proving that each type of goal can, in fact, be useful depending on the circumstances.

Elliot and McGregor’s research utilized a 2 x 2 achievement goal framework comprised of:

- Mastery-approach

- Mastery-avoidance

- Performance-approach

- Performance-avoidance

These variables were tested in 3 studies. In experiments one and two, explanatory factor analysis was used to break down 12 goal-setting questions into 4 factors, as seen in the diagram below.

Confirmatory factor analysis was used at a later date to show that mastery-avoidance and mastery-approach fit the data better than mastery alone.

The questions for these studies were created from a series of pilot studies and prior questionnaires. Once all of the questions were combined, a factor-analysis was utilized to confirm that each set of questions expressed different goal-setting components.

Results of these studies showed that those with a high motive to achieve were much more likely to use approach goals. Those with a high motive to avoid failure, on the other hand, were much more likely to use avoidance goals.

The third experiment examined the same four achievement goal variables and revealed that those more likely to use performance-approach goals were more likely to have higher exam scores, while those who used performance-avoidance goals were more likely to have lower exam scores.

According to the research, motivation in achievement settings is complex, and achievement goals are but one of several types of operative variables to be considered.

Achievement goal regulation, or the actual pursuit of the goal, implicates both the achievement goal itself as well as some other typically higher order factors such as motivationally relevant variables, according to the research done by Elliot and McGregor.

As we can clearly see, the research on goal setting is quite robust.

Mark Murphy the founder and CEO of LeadershipIQ.com and author of the book “ Hard Goals : The Secret to Getting from Where You Are to Where You Want to Be ,” has gone through years of research in science and how the brain works and how we are wired as a human being as it pertains to goal setting.

Murphy’s book “ Hard Goals: The Secret to Getting from Where You Are to Where You Want to Be” combines the latest research in psychology and brain science on goal-setting as well as the law of attraction to help fine-tune the process.

A HARD goal is an achieved goal, according to Murphy (2010). Murphy tells us to put our present cost into the future and our future benefit into the present.

What this really means is don’t put off until tomorrow what you could do today. We tend to value things in the present moment much more than we value things in the future.

Setting goals is a process that changes over time. The goals you set in your twenties will most likely be very different from the goals you set in your forties.

Download 3 Free Goals Exercises (PDF)

These detailed, science-based exercises will help you or your clients create actionable goals and master techniques for lasting behavior change.

Download 3 Free Goals Pack (PDF)

By filling out your name and email address below.

- Email Address *

- Your Expertise * Your expertise Therapy Coaching Education Counseling Business Healthcare Other

- Phone This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

Edward Locke and Gary Latham (1990) are leaders in goal-setting theory. According to their research, goals not only affect behavior as well as job performance, but they also help mobilize energy which leads to a higher effort overall. Higher effort leads to an increase in persistent effort.

Goals help motivate us to develop strategies that will enable us to perform at the required goal level.

Accomplishing the goal can either lead to satisfaction and further motivation or frustration and lower motivation if the goal is not accomplished.

Goal setting can be a very powerful technique, under the right conditions according to the research (Locke & Latham, 1991).

According to Lunenburg (2011), the motivational impact of goals may, in fact, be affected by moderators such as self-efficacy and ability as well.

In the 1968 article “ Toward a Theory of Task Motivation ” Locke showed us that clear goals and appropriate feedback served as a good motivator for employees (Locke, 1968).

Locke’s research also revealed that working toward a goal is a major source of motivation, which, in turn, improves performance.

Locke reviewed over a decade of research of laboratory and field studies on the effects of goal setting and performance. Locke found that over 90% of the time, goals that were specific and challenging, but not overly challenging, led to higher performance when compared to easy goals or goals that were too generic such as a goal to do your best.

Dr. Gary Latham also studied the effects of goal setting in the workplace. Latham’s results supported Locke’s findings and showed there is indeed a link that is inseparable between goal setting and workplace performance.

Locke and Latham published work together in 1990 with their work “ A Theory of Goal Setting & Task Performance ” stressing the importance of setting goals that were both specific and difficult.

Locke and Latham also stated that there are five goal-setting principles that can help improve your chances of success.

- Task Complexity

Clarity is important when it comes to goals. Setting goals that are clear and specific eliminate the confusion that occurs when a goal is set in a more generic manner.

Challenging goals stretch your mind and cause you to think bigger. This helps you accomplish more. Each success you achieve helps you build a winning mindset.

Commitment is also important. If you don’t commit to your goal with everything you have it is less likely you will achieve it.

Feedback helps you know what you are doing right and how you are doing. This allows you to adjust your expectations and your plan of action going forward.

Task Complexity is the final factor. It’s important to set goals that are aligned with the goal’s complexity.

Why the secret to success is setting the right goals – John Doerr

Goal setting and task performance were studied by Locke and Latham (1991). Goal setting theory is based upon the simplest of introspective observations, specifically, that conscious human behavior is purposeful.

This behavior is regulated by one’s goals. The directedness of those goals characterizes the actions of all living organisms including things like plants.

Goal-setting theory, according to the research, states that the simplest and most direct motivational explanation on why some people perform better than others is because they have different performance goals.

Two attributes have been studied in relation to performance:

In regard to content, the two aspects that have been focused on include specificity and difficulty. Goal content can range from vague to very specific as well as difficult or not as difficult.

Difficulty depends upon the relationship someone has to the task. The same task or goal can be easy for one person, and more challenging for the next, so it’s all relative.

On average though the higher the absolute level is of a goal, the more difficult it is to achieve. According to research, there have been more than 400 studies that have examined the relationship of goal attributes to task performance.

According to Locke and Latham (1991), it has been consistently found that performance is a linear function of a goal’s difficulty.

Given an adequate level of ability and commitment, the harder a goal, the higher the performance.

What the researchers discovered was that people normally adjust their level of effort to the difficulty of the goal. As a result, they try harder for difficult goals when compared to easier goals.

The principle of goal-directed action is not restricted to conscious action, according to the research.

Goal-directed action is defined by three attributes, according to Lock & Latham.

- Self-generation

- Value-significance

- Goal-causation

Self-generation refers to the source of energy integral to the organism. Value-significance refers to the idea that the actions not only make it possible but necessary to the organism’s survival. Goal-causation means the resulting action is caused by a goal.

While we can see that all living organisms experience some kind of goal-related action, humans are the only organisms that possess a higher form of consciousness, at least according to what we know at this point in time.

When humans take purposeful action, they set goals in order to achieve them.

Locke and Latham have also shown us that there is an important relationship between goals and performance.

Locke and Latham’s research supports the idea that the most effective performance seems to be the result of goals being both specific and challenging. When goals are used to evaluate performance and linked to feedback on results, they create a sense of commitment and acceptance.

The researchers also found that the motivational impact of goals may be affected by ability and self-efficacy, or one’s belief that they can achieve something.

It was also found that deadlines helped improve the effectiveness of a goal and a learning goal orientation leads to higher performance when compared to a performance goal orientation.

Research done by Moeller, Theiler, and Wu (2012) examined the relationship between goal setting and student achievement at the classroom level.

This research examined a 5-year quasi-experimental study, which looked at goal setting and student achievement in the high school Spanish language classroom.

A tool known as LinguaFolio was used, and introduced into 23 high schools with a total of 1,273 students.

The study portfolio focused on student goal setting , self-assessment and a collection of evidence of language achievement.

Researchers used a hierarchical linear model, and then analyzed the relationship between goal setting and student achievement. This research was done at both the individual student and teacher levels.

A correlational analysis of the goal-setting process as well as language proficiency scores revealed a statistically significant relationship between the process of setting goals and language achievement (p < .01).

The research also looked at the importance of autonomy or one’s ability to take responsibility for their learning. Autonomy is a long-term aim of education, according to the study as well as a key factor in learning a language successfully.

There has been a paradigm shift in language education from teacher to student-centered learning, which makes the idea of autonomy even more important.

Goal setting in language learning is commonly regarded as one of the strategies that encourage a student’s sense of autonomy (Moeller, Theiler & Wu, 2012)

The results of the study revealed that there was a consistent increase over time in the main goal, plan of action and reflection scores of high school Spanish learners.

This trend held true for all levels except for the progression from third to fourth year Spanish for action plan writing and goal setting. The greatest improvement in goal setting occurred between the second and third levels of Spanish.

In one study , that looked at goal setting and wellbeing, people participated in three short one-hour sessions where they set goals.

The researchers compared those who set goals to a control group, that didn’t complete the goal-setting exercise . The results showed a causal relationship between goal setting and subjective wellbeing.

Weinberger, Mateo, and Sirey (2009) also looked at perceived barriers to mental health care and goal setting amongst depressed, community-dwelling older adults.

Forty-seven participants completed the study, which examined various barriers to mental health and goal setting. These barriers include:

- Psychological barriers such as social attitudes, beliefs about depression and stigmas.

- Logistical barriers such as transportation and availability of services.

- Illness-related barriers that are either modifiable or not such as depression severity, comorbid anxiety, cognitive status, etc.

For individuals who perceive a large number of barriers to be overcome, a mental health referral can seem burdensome as opposed to helpful.

Defining a personal goal for treatment may be something that is helpful and even something that can increase the relevance of seeking help and improving access to care according to the study.

Goal setting has been shown to help improve the outcome in treatment, amongst studies done in adults with depression. (Weinberger, Mateo, & Sirey, 2009)

The process of goal setting has even become a major focus in several of the current psychotherapies used to treat depression. Some of the therapies that have used goal setting include:

- Interpersonal Psychotherapy (IPT)

- Cognitive and Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CT, CBT)

- Problem-Solving Therapy (PST)

Participants who set goals, according to the study, were more likely to accept a mental health referral. Goal setting seems to be a necessary and good first step when it comes to helping a depressed older adult take control of their wellbeing.

Most of us have been taught from a young age that setting goals can help us accomplish more and get better organized.

Goals help motivate us and help us organize our thoughts. Throughout evolutionary psychology, however, a conscious activity like goal setting has often been downplayed.

Psychoanalysis put the focus on the unconscious part of the mind, while cognitive behaviorists argue that external factors are of greater importance.

In 1968, Edward A. Locke formally developed something he called goal-setting theory, as an alternative to all of this.

Goal-setting theory helps us understand that setting goals are a conscious process and a very effective and efficient means when it comes to increasing productivity and motivation, especially in the workplace.

According to Gary P. Latham, the former President of the Canadian Psychological Association, the underlying premise of goal-setting theory is that our conscious goals affect what we achieve. Our goals are the object or the aim of our action.

This viewpoint is not aligned with the traditional cognitive behaviorism, which looks at human behavior as something that is conducted by external stimuli.

This view tells us that just like a mechanic works on a car, other people often work on our brains, without us even realizing it, and this, in turn, determines how we behave.

Goal setting theory goes beyond this assumption, telling us that our internal cognitive functions are equally important, if not more, when determining our behavior.

In order for our conscious cognition to be effective, we must direct and orient our behavior toward the world. That is the real purpose of a goal.

According to Locke and Latham, there is an important relationship between goals and performance.

Research supports the prediction that the most effective performance often results when goals are both specific and challenging in nature.

A learning goal orientation often leads to higher performance when compared to a performance goal orientation, according to the research.

Deadlines also improve the effectiveness of a goal. Goals have a pervasive influence on both employee behaviors and performance in organizations and management practice according to Locke and Latham (2002).

According to the research, nearly every modern organization has some type of psychological goal setting program in its operation.

Programs like management by objectives, (MBO), high-performance work practices (HPWP) and management information systems (MIS) all use benchmarking to stretch targets and plan strategically, all of which involve goal setting to some extent.

Fred C. Lunenburg, a professor at Sam Houston State University, summarized these points in the International Journal of Management, Business, and Administration journal article “Goal-Setting Theory of Motivation” (Lunenburg, 2011).

Specific: Specificity tells us that in order for a goal to be successful, it must also be specific. Goals such as I will do better next time are much too vague and general to motivate us.

Something more specific would be to state: I will spend at least 2 hours a day this week in order to finish the report by the deadline . This goal motivates us into action and holds us accountable.

Difficult but still attainable : Goals must, of course, be attainable, but they shouldn’t be too easy. Goals that are too simple may even cause us to give up. Goals should be challenging enough to motivate us without causing us undue stress.

Process of Acceptance : If we are continually given goals by other people, and we don’t truly accept them, we will most likely continue to fail. Accepting a goal and owning a goal is the key to success.

One way to do this on an organizational level is to bring team members together to discuss and set goals.

Feedback and evaluation : When a goal is accomplished, it makes us feel good. It gives us a sense of satisfaction. If we don’t get any feedback, this sense of pleasure will quickly go away and the accomplishment may even be meaningless.

In the workplace, continuous feedback helps give us a sense that our work and contributions matter. This goes beyond measuring a single goal.

When goals are used for performance evaluation, they are often much more effective.

Learning beyond our performance : While goals can be used as a means by which to give us feedback and evaluate our performance, the real beauty of goal setting is the fact that it helps us learn something new.

When we learn something new, we develop new skills and this helps us move up in the workplace.

Learning-oriented goals can also be very helpful when it comes to helping us discover life-meaning which can help increase productivity.

Performance-oriented goals, on the other hand, force an employee to prove what he or she can or cannot do, which is often counterproductive.

These types of goals are also less likely to produce a sense of meaning and pleasure. If we lack that sense of satisfaction, when it comes to setting and achieving a goal, we are less likely to learn and grow and explore.

Group goals : Setting group goals is also vitally important for companies. Just as individuals have goals, so too must groups and teams, and even committees. Group goals help bring people together and allow them to develop and work on the same goals.

This helps create a sense of community, as well as a deeper sense of meaning, and a greater feeling of belonging and satisfaction.

World’s Largest Positive Psychology Resource

The Positive Psychology Toolkit© is a groundbreaking practitioner resource containing over 500 science-based exercises , activities, interventions, questionnaires, and assessments created by experts using the latest positive psychology research.

Updated monthly. 100% Science-based.

“The best positive psychology resource out there!” — Emiliya Zhivotovskaya , Flourishing Center CEO

A goal properly set is halfway reached.

Everybody has their own Mount Everest they were put on this earth to climb.

You cannot change your destination overnight, but you can change your direction overnight.

It’s better to be at the bottom of the ladder you want to climb than at the top of the one you don’t.

Stephen Kellogg

If you don’t design your own life plan, chances are you’ll fall into someone else’s plan. And guess what they have planned for you? Not much.

All who have accomplished great things have had a great aim, have fixed their gaze on a goal which was high, one which sometimes seemed impossible.

Orison Swett Marden

The greater danger for most of us isn’t that our aim is too high and miss it, but that it is too low and we reach it.

Michelangelo

Give me a stock clerk with a goal and I’ll give you a man who will make history. Give me a man with no goals and I’ll give you a stock clerk.

J.C. Penney

Intention without action is an insult to those who expect the best from you.

Andy Andrews

This one step – choosing a goal and sticking to it – changes everything.

Setting goals can help us move forward in life. Goals give us a roadmap to follow. Goals are a great way to hold ourselves accountable, even if we fail. Setting goals and working to achieving them helps us define what we truly want in life.

Setting goals also helps us prioritize things. If we choose to simply wander through life, without a goal or a plan, that’s certainly our choice. However, setting goals can help us live the life we truly want to live.

Having said that, we don’t have to live every single moment of our lives planned out because we all need those days when we have nothing to accomplish.

However, those who have clearly defined goals might just enjoy their downtime even more than those who don’t set goals.

For more insightful reading, check out our selection of goal-setting books .

We hope you enjoyed reading this article. Don’t forget to download our three Goal Achievement Exercises for free .

- Elliot, A. J., & McGregor, H. A. (2001). A 2 x 2 achievement goal framework. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 80 (3), 501-519.

- Locke, E. A. (1968). Toward a theory of task motivation and incentives. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance , 3 (2), 157-189.

- Locke, E. A., & Latham, G. P. (1991). A theory of goal setting & task performance. The Academy of Management Review, 16 (2), 212-247.

- Locke, E. A., & Latham, G. P. (2002). Building a practically useful theory of goal setting and task motivation. American Psychologist, 57 (9), 705-717.

- Lunenburg, F. C. (2011). Goal-setting theory of motivation. International Journal of Management, Business, and Administration, 15 (1), 1-6.

- Moeller, A. J., Theiler, J. M., & Wu, C. (2012). Goal setting and student achievement: A longitudinal study. The Modern Language Journal, 96 (2), 153-169.

- Murphy, M. (2010). HARD goals: The secret to getting from where you are to where you want to be. New York, NY: McGraw Hill.

- Weinberger, M. I., Mateo, C., & Sirey, J. A. (2009). Perceived barriers to mental health care and goal setting among depressed, community-dwelling older adults. Patient Preference and Adherence, 3 , 145-149.

Share this article:

Article feedback

What our readers think.

Goal setting motivates by providing direction, enhancing focus, boosting self-confidence, and fostering persistence through clear, achievable targets.

I really love how the lesson teaches us how to set goals more often

Let us know your thoughts Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Related articles

Victor Vroom’s Expectancy Theory of Motivation

Motivation is vital to beginning and maintaining healthy behavior in the workplace, education, and beyond, and it drives us toward our desired outcomes (Zajda, 2023). [...]

SMART Goals, HARD Goals, PACT, or OKRs: What Works?

Goal setting is vital in business, education, and performance environments such as sports, yet it is also a key component of many coaching and counseling [...]

How to Assess and Improve Readiness for Change

Clients seeking professional help from a counselor or therapist are often aware they need to change yet may not be ready to begin their journey. [...]

Read other articles by their category

- Body & Brain (50)

- Coaching & Application (58)

- Compassion (25)

- Counseling (51)

- Emotional Intelligence (23)

- Gratitude (18)

- Grief & Bereavement (21)

- Happiness & SWB (40)

- Meaning & Values (26)

- Meditation (20)

- Mindfulness (44)

- Motivation & Goals (45)

- Optimism & Mindset (34)

- Positive CBT (30)

- Positive Communication (22)

- Positive Education (47)

- Positive Emotions (32)

- Positive Leadership (19)

- Positive Parenting (16)

- Positive Psychology (34)

- Positive Workplace (37)

- Productivity (18)

- Relationships (44)

- Resilience & Coping (39)

- Self Awareness (21)

- Self Esteem (38)

- Strengths & Virtues (32)

- Stress & Burnout Prevention (34)

- Theory & Books (46)

- Therapy Exercises (37)

- Types of Therapy (64)

- Email This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

3 Goal Achievement Exercises Pack

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Student Goal-Setting: An Evidence-Based Practice

2018, American Institutes for Research

The act of goal-setting is a desired competency area for students and is also a practice educators can use to help fuel students' learning to learn skills. This resource includes a brief summary of the research, highlights promising goal-setting practices and provides the results of a research evidence review that indicates that there is promising Tier III evidence for the practice of student goal-setting.

Related Papers

Michaela Schippers

This conceptual paper reviews the current status of goal setting in the area of technology enhanced learning and education. Besides a brief literature review, three current projects on goal setting are discussed. The paper shows that the main barriers for goal setting applications in education are not related to the technology, the available data or analytical methods, but rather the human factor. The most important bottlenecks are the lack of students goal setting skills and abilities, and the current curriculum design, which, especially in the observed higher education institutions, provides little support for goal setting interventions.

The Modern Language Journal

Aleidine Moeller , ChaoRong Wu

Journal of Education and Learning (EduLearn)

BNK10621 Lee Yi Yun

One of the prominent theory was the goal-setting theory which was widely been used in educational setting. It is an approach than can enhance the teaching and learning activities in the classroom. This is a report paper about a simple study of the implementation of the goal-setting principle in the classroom. A clinical data of the teaching and learning session was then analysed to address several issues highlighted. It is found that the goal-setting principles if understood clearly by the teachers can enhance the teaching and learning activities. Failed to see the needs of the session will revoke the students learning interest. It is suggested that goal-setting learning principles could become a powerful aid for the teachers in the classroom.

A Discourse on Educational Issues: A festschrift in honour of five professors: Prof. Okwudishu, C. O., Prof. Ikerionwu, J. C., Prof. Tahir, G. M., Prof. Okwudishu, A. U. and Prof. Okatahi, A. O.

Aminu Kazeem Ibrahim

Journal of Applied Social Psychology

Neha Singla

The Journal of Educational Research

Betty Jane Punnett

Nerelie Teese

Setting personal learning goals is an important life skill that students are encouraged to develop from the middle years of schooling onwards. However, some students experience difficulty with the processes involved in setting and achieving their goals. This professional paper looks at the role teacher librarians have in collaboratively planning, resourcing, and extending and enriching goal setting activities. Providing resources with authentic examples of goal setting by people from the wider community is one way of developing and extending the motivation and commitment students need to become successful in goal setting tasks and activities. One such resource is recommended and details of it are outlined with suggestions for extending and enriching it with a visit or virtual presentation from its author.

Educational Psychology

Susan Grantham

Loading Preview

Sorry, preview is currently unavailable. You can download the paper by clicking the button above.

RELATED PAPERS

Educational and Psychological Measurement

Martin Dowson

Caroline Wesson

International journal of educational research

Georgios Sideridis

Journal of Applied Psychology

Robert Pihl

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Goal Setting for Middle & High School Students: Why It’s Important, Tips, and Resources

As students grow, so do their responsibilities. When students transition from primary to secondary, they increasingly take charge and set the course of their learning and goal setting. This happens the most in high school, and for good reason.

Read on for why goal setting for high school students is important, tips for teaching student goal setting, and classroom resources to help you do it.

Why is Goal Setting Important for Students?

Goal setting is important because it gives students the opportunity to assert their growing independence, manage their own tasks and the emotions that accompany them, and take the wheel in driving their learning. It’s also developmentally important for students to increase their self-management and self-awareness over time, and goal setting can help build those social-emotional learning skills. This is especially important in high school as students look ahead to adulthood.

However, goal setting is not something that students inherently know how to do; it has to be taught. Without the guidance of knowledgeable, compassionate educators, students may set goals that are unattainable or too vague. This can lead to students feeling frustrated and abandoning their goals when they don’t see progress. In order for high school students to grow, their goals need to be motivating and achievable. This is a key component of goal setting that will allow your students to see its many benefits.

Benefits of Teaching Goal Setting for Students

Some of the major benefits of goal setting include:

- It engages students in the process of personalizing and differentiating their learning by giving them agency and choice.

- Students develop self-awareness about their strengths and the interconnected nature of emotions, behavior, and actions through self-reflection.

- Goal setting centered on progress over results helps students develop a growth mindset.

- Students feel in control, empowered, and motivated to learn and grow.

- Goal setting creates a self-management framework through which students can take on more responsibility.

- Accomplishing self-set goals can build up self-efficacy , and by proxy self-esteem.

- Students learn how to identify, communicate, and advocate for their learning needs.

- Goal setting now will help set students up for success later in goal-driven environments like college and work.

With these benefits in mind, it’s equally important for teachers to develop a strategy for implementing goal setting in class.

4 Ways to Teach Student Goal Setting in High School

To help get you started, here are four strategies for teaching goal setting throughout the school year, or during reset moments like back to school, New Year’s , or an extended school break . (And the resources you need to teach it!)

1. Get Students Invested: Ask students goal-setting questions to encourage introspection, critical thinking, and deeper engagement.

Not only will these questions bring students more deeply into the learning process, but they will also help students practice the foundational SEL skill of self-awareness. This skill is essential for setting attainable goals because they are subjective and personal, so strong goal-setting hinges on students’ understanding of their beliefs, values, and strengths.

Resources for Goal-Setting Questions

Identifying Your Goals by Informed Decisions

Grades: 6-12

New Years Conversation Starters & Journal Writing Prompts – Goals & Reflections by Thinking Zing Counseling

Grades: 7-12

100 Conversation Starters for Middle and High School | Goal Setting by College Counselor Studio

Grades: 9-12