- How to Cite

- Language & Lit

- Rhyme & Rhythm

- The Rewrite

- Search Glass

How to Write a Body Paragraph for a Persuasive Essay

Persuasive essays attempt to influence readers to change their attitudes about a topic. To write an effective persuasive essay, choose a topic you feel strongly about and then use well-developed and carefully structured body paragraphs to create a powerful argument. Paragraphs for the essay should contain topic sentences, support, concluding sentences and transitions.

Create a Topic Sentence

Develop a strong topic sentence for the body paragraph that connects to one of the topics from your persuasive thesis. The topic sentence explains that the paragraph will focus on this one point to persuade your readers. For instance, a paragraph within a persuasive paper convincing readers that high school students should wear uniforms could begin, "Requiring uniforms helps reduce theft in schools." The reader understands the paragraph's focus from this topic sentence. It also connects to the thesis, emphasizing the persuasive stance about requiring uniforms. The rest of the paragraph would go on to support this point, explaining how theft is reduced when students do not have more expensive clothing and shoes that sets them up as targets.

Add Detailed Support

The information within the body paragraph must help convince your readers of your point. Examples, statistics, opinions and anecdotes from your own experience or research lend support to your persuasive paper. A paragraph in a paper persuading readers that cities should offer free Internet to residents might focus on the educational benefits. To support that point, you could add an explanation of how school test scores increased after a city offered Wi-Fi, include a quote from an expert about how access raises intellectual ability and explain your own thoughts about how more people would read Web information and therefore acquire more knowledge.

Include Enough Detail

Write at least three sentences to support the main idea. As the Purdue University Online Writing Lab indicates, paragraphs made up of just a few sentences generally lack substantive backing. Your paragraph must help persuade your reader to adopt your beliefs, so it needs to be specific and fully developed using elements like comparing and contrasting, data, anecdotes, analysis, description or cause and effect. A paragraph about the costs of free Wi-Fi for city residents could have numbers to illustrate the price of setting it up and how those costs could be made up through taxes, for example.

Write a Concluding Sentence

End your body paragraph with a concluding sentence to tie the ideas together and stress how the details you provided support your overall persuasive point. For a paper persuading readers that dogs should not be euthanized if they attack someone, a paragraph focused on the possibilities of retraining could end, "Society does not condone killing a human incapable of understanding the consequences of his actions and able to change; killing animals before attempting retraining should not be accepted, either." The sentence emphasizes the connection between the support and the persuasive argument.

Include Transitions

Add transitions throughout your paragraph to more clearly connect the ideas to each other and your overall argument. Use words and phrases like "similarly" or "consequently" to illustrate how the ideas relate, or repeat key words and phrases such as "government regulation of gambling" to remind readers of the relationships. Include pronouns like "it" to refer to the government regulation and synonyms like "laws" for coherence. Parallel structure -- using the same grammatical structure in multiple sentences -- also helps connect ideas, for example: "Government regulation will prevent abuse. Government regulation will provide jobs. Government regulation will increase state funds."

- Austin Peay State University: The Argumentative (Persuasive) Essay

- Loyola University New Orleans: Paragraphs: The Body of the Essay

- Purdue University: On Paragraphs

- Anne Arundel Community College: Formulating a Concluding Sentence for a Paragraph

Kristie Sweet has been writing professionally since 1982, most recently publishing for various websites on topics like health and wellness, and education. She holds a Master of Arts in English from the University of Northern Colorado.

How to Write and Structure a Persuasive Speech

- Homework Tips

- Learning Styles & Skills

- Study Methods

- Time Management

- Private School

- College Admissions

- College Life

- Graduate School

- Business School

- Distance Learning

- M.Ed., Education Administration, University of Georgia

- B.A., History, Armstrong State University

The purpose of a persuasive speech is to convince your audience to agree with an idea or opinion that you present. First, you'll need to choose a side on a controversial topic, then you will write a speech to explain your position, and convince the audience to agree with you.

You can produce an effective persuasive speech if you structure your argument as a solution to a problem. Your first job as a speaker is to convince your audience that a particular problem is important to them, and then you must convince them that you have the solution to make things better.

Note: You don't have to address a real problem. Any need can work as the problem. For example, you could consider the lack of a pet, the need to wash one's hands, or the need to pick a particular sport to play as the "problem."

As an example, let's imagine that you have chosen "Getting Up Early" as your persuasion topic. Your goal will be to persuade classmates to get themselves out of bed an hour earlier every morning. In this instance, the problem could be summed up as "morning chaos."

A standard speech format has an introduction with a great hook statement, three main points, and a summary. Your persuasive speech will be a tailored version of this format.

Before you write the text of your speech, you should sketch an outline that includes your hook statement and three main points.

Writing the Text

The introduction of your speech must be compelling because your audience will make up their minds within a few minutes whether or not they are interested in your topic.

Before you write the full body you should come up with a greeting. Your greeting can be as simple as "Good morning everyone. My name is Frank."

After your greeting, you will offer a hook to capture attention. A hook sentence for the "morning chaos" speech could be a question:

- How many times have you been late for school?

- Does your day begin with shouts and arguments?

- Have you ever missed the bus?

Or your hook could be a statistic or surprising statement:

- More than 50 percent of high school students skip breakfast because they just don't have time to eat.

- Tardy kids drop out of school more often than punctual kids.

Once you have the attention of your audience, follow through to define the topic/problem and introduce your solution. Here's an example of what you might have so far:

Good afternoon, class. Some of you know me, but some of you may not. My name is Frank Godfrey, and I have a question for you. Does your day begin with shouts and arguments? Do you go to school in a bad mood because you've been yelled at, or because you argued with your parent? The chaos you experience in the morning can bring you down and affect your performance at school.

Add the solution:

You can improve your mood and your school performance by adding more time to your morning schedule. You can accomplish this by setting your alarm clock to go off one hour earlier.

Your next task will be to write the body, which will contain the three main points you've come up with to argue your position. Each point will be followed by supporting evidence or anecdotes, and each body paragraph will need to end with a transition statement that leads to the next segment. Here is a sample of three main statements:

- Bad moods caused by morning chaos will affect your workday performance.

- If you skip breakfast to buy time, you're making a harmful health decision.

- (Ending on a cheerful note) You'll enjoy a boost to your self-esteem when you reduce the morning chaos.

After you write three body paragraphs with strong transition statements that make your speech flow, you are ready to work on your summary.

Your summary will re-emphasize your argument and restate your points in slightly different language. This can be a little tricky. You don't want to sound repetitive but will need to repeat what you have said. Find a way to reword the same main points.

Finally, you must make sure to write a clear final sentence or passage to keep yourself from stammering at the end or fading off in an awkward moment. A few examples of graceful exits:

- We all like to sleep. It's hard to get up some mornings, but rest assured that the reward is well worth the effort.

- If you follow these guidelines and make the effort to get up a little bit earlier every day, you'll reap rewards in your home life and on your report card.

Tips for Writing Your Speech

- Don't be confrontational in your argument. You don't need to put down the other side; just convince your audience that your position is correct by using positive assertions.

- Use simple statistics. Don't overwhelm your audience with confusing numbers.

- Don't complicate your speech by going outside the standard "three points" format. While it might seem simplistic, it is a tried and true method for presenting to an audience who is listening as opposed to reading.

- How to Write a Persuasive Essay

- 5 Tips on How to Write a Speech Essay

- Tips on How to Write an Argumentative Essay

- Writing an Opinion Essay

- How To Write an Essay

- 5 Steps to Writing a Position Paper

- How to Structure an Essay

- Ethos, Logos, Pathos for Persuasion

- What Is Expository Writing?

- Audience Analysis in Speech and Composition

- Definition and Examples of Analysis in Composition

- 100 Persuasive Speech Topics for Students

- What an Essay Is and How to Write One

- How to Write a Good Thesis Statement

- 100 Persuasive Essay Topics

- How to Write a Graduation Speech as Valedictorian

How To Write A Persuasive Speech: 7 Steps

Table of contents

- 1 Guidance on Selecting an Effective and Relevant Topic

- 2 Strategies for Connecting With Different Types of Audiences

- 3 Developing Your Thesis Statement

- 4.1 Writing the Introduction

- 4.2 Body of Your Speech

- 4.3 Concluding Effectively

- 5 Techniques for Creating a Coherent Flow of Ideas

- 6 Importance of Transitions Between Points

- 7 Importance of Tone and Style Adjustments Based on the Audience

- 8 Prepare for Rebuttals

- 9 Use Simple Statistics

- 10 Practicing Your Speech

- 11 Additional Resources to Master Your Speech

- 12 Master the Art of Persuasion With PapersOwl

Are you about to perform a persuasive speech and have no idea how to do it? No need to worry; PapersOwl is here to guide you through this journey!

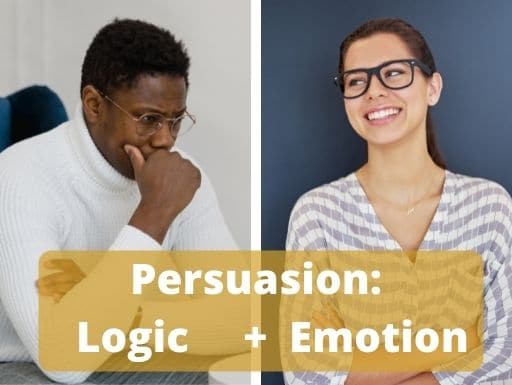

What is persuasive speaking? Persuasive speaking is a form of communication where the speaker aims to influence or convince the audience to adopt a particular viewpoint or belief or take specific actions. The goal is to sway the listeners’ opinions, attitudes, or behaviors by presenting compelling arguments and supporting evidence while appealing to their emotions.

Today, we prepared a guide to help you write a persuasive speech and succeed in your performance, which will surprise your audience. We will:

- Understand how to connect with your audience.

- Give you persuasive speech tips.

- Provide you with the best structure for a persuasive speech outline.

- Prepare yourself for rebuttals!

- Talk about the importance of flow in your speech.

- Discover additional resources for continuous improvement.

Let’s begin this journey together!

Guidance on Selecting an Effective and Relevant Topic

The most important thing in convincing speeches is the topic. Indeed, you must understand the purpose of your speech to succeed. Before preparing for your performance, you should understand what you want to discuss! To do that, you can:

- Choose a compelling speech topic relevant to your audience’s interests and concerns.

- Find common interests or problems to form a genuine relationship.

- Remember that a persuasive speech format should be adapted to your audience’s needs and ideals. Make your content relevant and appealing.

And if you are struggling on this step, PapersOwl is already here to help you! Opt to choose persuasive speech topics and find the one that feels perfect for you.

Strategies for Connecting With Different Types of Audiences

A successful persuasive speech connects you with your audience. To do that, you should really know how to connect yourself to people.

Thus, the speaker connects with and persuades the audience by using emotions such as sympathy or fear. Therefore, you can successfully connect with different types of audiences through different emotions. You can do it by showing that you have something in common with the audience. For example, demonstrate that you have a comparable history or an emotional connection. Additionally, include personal stories or even make a part of a speech about yourself to allow your audience to relate to your story.

Developing Your Thesis Statement

When you give a persuasive speech, there should be a thesis statement demonstrating that your goal is to enlighten the audience rather than convince them.

A thesis statement in persuasive speaking serves as the central argument or main point, guiding the entire presentation. A successful thesis anchors your speech and briefly expresses your position on the subject, giving a road map for both you and your audience.

For instance, in pushing for renewable energy, a thesis may be: “Transitioning to renewable sources is imperative for a sustainable future, mitigating environmental impact and fostering energy independence.” This statement summarizes the argument and foreshadows the supporting points.

Overview of speech structure (introduction, body, conclusion)

The key elements of a persuasive speech are:

- introduction (hook, thesis, preview);

- body (main points with supporting details and transitions);

- conclusion (summary, restated thesis, closing statement).

Let’s look closer at how to structure them to write a good persuasive speech.

Writing the Introduction

The introduction to persuasive speech is crucial. The very beginning of your discourse determines your whole performance, drawing in your audience and creating a foundation for trust and engagement. Remember, it’s your opportunity to make a memorable first impression, ensuring your listeners are intrigued and receptive to your message.

Start off a persuasive speech with an enticing quotation, image, video, or engaging tale; it can entice people to listen. As we mentioned before, you may connect your speech to the audience and what they are interested in. Establish credibility by showcasing your expertise or connecting with shared values. Ultimately, ensure your thesis is clear and outline which specific purpose statement is most important in your persuasive speech.

Body of Your Speech

After choosing the topic and writing an intro, it’s time to concentrate on one of the most critical parts of a persuasive speech: the body.

The main body of your speech should provide the audience with several convincing reasons to support your viewpoint. In this part of your speech, create engaging primary points by offering strong supporting evidence — use statistics, illustrations, or expert quotations to strengthen each argument. Also, don’t forget to include storytelling for an emotional connection with your audience. If you follow this combination, it will for sure make a speech persuasive!

Concluding Effectively

After succeeding in writing the main points, it is time to end a persuasive speech! Indeed, a call to action in persuasive speech is vital, so we recommend you end your performance with it. After listening to your argument and proof, you want the audience to make a move. Restate your purpose statement, summarize the topic, and reinforce your points by restating the logical evidence you’ve provided.

Techniques for Creating a Coherent Flow of Ideas

Your ideas should flow smoothly and naturally connect to strengthen the persuasive speech structure . You can do this by employing transitional words and organizing your thoughts methodically, ensuring that each point flows effortlessly into the next.

Importance of Transitions Between Points

No one can underestimate the importance of transition. They are important persuasive speech elements. Thus, each idea must flow smoothly into the following one with linking phrases so your speech has a logical flow. Effective transitions signal shifts, aiding audience comprehension and improving the overall structure of the speech.

Importance of Tone and Style Adjustments Based on the Audience

To be persuasive in a speech, don’t forget to analyze your audience in advance, if possible. Customizing your approach to specific listeners encourages their engagement. A thorough awareness of your target audience’s tastes, expectations, and cultural subtleties ensures that your message connects, making it more approachable and appealing to the people you seek to reach.

Prepare for Rebuttals

Still, be aware that there may be different people in the audience. The main point of persuasive speaking is to convince people of your ideas. Be prepared for rebuttals and that they might attack you. Extensively research opposing points of view to prove yours. You may manage any objections with elegance by being prepared and polite, reaffirming the strength of your argument.

Use Simple Statistics

We’ve already discussed that different techniques may reach different audiences. You could also incorporate simple data to lend credibility to your persuasive talk. Balance emotional appeal with plain numerical statistics to create a captivating blend that will appeal to a wide audience.

Practicing Your Speech

We all have heard Benjamin Franklin’s famous quote, “Practice makes perfect.” Even though he said it hundreds of years ago, it still works for everything, including persuasive public speaking! Consequently, you can improve your text with these pieces of advice:

- Go through and edit your persuasive speech sample.

- Practice your speech with body language and voice variation to find the perfect way to perform it.

- Reduce anxiety by practicing in front of a mirror or telling it to someone ready to provide you with valuable feedback.

- Embrace pauses for emphasis, and work on regulating your pace.

It will help you to know your content well, increase confidence, and promote a polished delivery, resulting in a dynamic and engaging speech to persuade your audience.

Additional Resources to Master Your Speech

PapersOwl wants you to ace your speech! We recommend using additional sources to help master your persuasive speech presentation!

- For inspiration, study any example of persuasive speech from a famous speaker, such as Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” or Steve Jobs’ Stanford commencement address. Analyzing these speeches can provide valuable insights into effective communication techniques.

- Explore Coursera’s course “Speaking to Persuade: Motivating Audiences With Solid Arguments and Moving Language” by the University of Washington.

- Go through different persuasive speech examples for students around the internet, for instance, “Talk Like TED” by Carmine Gallo.

Make your persuasive speech successful by continuously learning and drawing inspiration from accomplished speakers!

Master the Art of Persuasion With PapersOwl

In conclusion, speaking to persuade is an art that helps convince with words . You can craft it by following our tips: include a well-structured persuasive speech introduction, a compelling body, and memorable conclusion. To ace your speech, practice it in advance, be ready for rebuttals, and confidently state your message. The secret lies in blending both for a nuanced and compelling communication style, ensuring your message resonates with diverse audiences in various contexts.

Nevertheless, writing a persuasive speech that can hold your audience’s attention might be difficult. You do not need to step on this path alone. You may quickly construct a persuasive speech that is both successful and well-organized by working with PapersOwl.com . We’ll be there for you every step, from developing a convincing argument to confidently giving the speech. Just send us a message, “ write a speech for me ,” and enjoy the results!

Readers also enjoyed

WHY WAIT? PLACE AN ORDER RIGHT NOW!

Just fill out the form, press the button, and have no worries!

We use cookies to give you the best experience possible. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy.

If you think of your persuasive writing as going out to a restaurant, then your introduction is the menu, because it shows you what is coming to you. The conclusion is the bill, showing what you just digested, and the body is the meat and potatoes. The body is where all the points are, where all your information is, and where you make your arguments of why you want the reader to come over to your side.

Paragraphs in your body should number about four in total. Each paragraph should cover the main point you are using to back up your argument and idea. In each paragraph, you need to have three to four smaller points that defend the larger point of the paragraph. To understand how this will look, we will break it down:

- First sentence. This carries your main point of the paragraph.

- Second sentence. This contains the minor point that backs up the major point of the paragraph.

- Third sentence. This contains the second minor point that backs up the major point of the paragraph.

- Fourth sentence. This contains the third minor point of the major point of the paragraph.

- Fifth sentence. This is the sentence that is the transition to your next point in the next paragraph.

In the body, you are supporting your thesis with those paragraphs. The body is proof that you have researched all the information and you have examined the topic completely. All the facts and figures of your persuasive argument are going to be in the body. For example, if you are going to be talking about how you deserve a raise in the persuasive letter body, then you are going to need to outline the statistics of why you deserve the raise. You will mention how few sick days you have taken, the rising cost of living, and the growing revenues of the company in the body. In fact, each paragraph can be centered on the major point of one fact or figure.

First, you need to have a statement of facts, which can include summaries concerning the problem you are discussing. It is in this part of the body that you should support all the information without stating your point of view, or trying to get the reader to agree with you.

Next, remind the reader of events or emotive illustrations that show the significance of the topic you are talking about. This should be quite clear and vivid, but brief. Do not obscure any of the information in this paragraph otherwise you could hurt your case. If you are looking for a raise by sending a persuasive letter to your boss, then this is where you will evoke emotions about how you care about the company, the raises you have received in the past, and even what the boss would do if they were in your situation.

Once you have gone through the facts in the previous paragraph, you should prove your thesis with arguments. This is the longest part of your body and it is essentially the central part of your persuasive argument. Your reader will already be paying attention, due to the previous paragraph where you detailed the facts and emotions behind your thesis. Now you show them why your position concerning your point of view is the right one, and that it should be accepted by those reading your persuasive argument.

In the next paragraph, you need to prove that the opposing argument is wrong. This is one of the most difficult parts of the body, because you have to not only prove the person reading the persuasive argument is wrong, but you have to do it in a respectful way that won't offend the reader by how you word the sentences. You should take your time writing this and really look at it from the other person's point of view. When you do this right, your reader will actually agree with what you are saying before realizing that they just blew their own argument out of the water.

Your conclusion is very important to your entire persuasive argument, because a conclusion that stays in your reader's mind will help you convince them that your point of view is the right one.

Your conclusion is an integral part of your persuasive writing. By essentially tying everything up in the end, you greatly increase the effectiveness of your argument. Your conclusion needs to be memorable and thought-provoking. You want the reader to put your persuasive essay down and think about what you wrote, what you said, and begin to realize why you may be right.

Here are a few tips that can help you with your conclusion and winning argument.

Your introduction and conclusion are the bread of your persuasive sandwich. The body is the ham between the slices of bread. Like the bread, your introduction and conclusion should be similar to each other, in a way, mirror images of each other. In your conclusion, you are working to remind the reader about what you said in your thesis statement. You are not wasting your time with the conclusion; you are getting right down to work showing why you proved your thesis statement in the body. All this is done in the conclusion.

Like you did with your introduction, where you wrote several different introduction types depending on your strategy, you can do the same with your conclusion. You should write several conclusions to see which one works best with what you wrote in the introduction and body. You want to make sure your conclusion doesn't contradict anything that you said in the body.

In the conclusion, you should restate your thesis statement, reworded slightly, and then you should go over the main points in your body. The reason that you go over the main points of the body in the conclusion is because you want the reader to recall those main points of your position. When you watch commercials, they will often say the name of the product over and over. This is done because humans learn through repetition. By repeating something, it is more likely that what you said will stick in the reader's mind, and therefore, there is a greater chance they will side with your position.

Another way to conclude your persuasive letter is to write a personal comment in it, or even a call to action. The types of things you could include in this last part of your conclusion are:

- "With a raise, my productivity will go up and by extension, the productivity of my entire department."

- "Would you work harder for more money? Or harder for less money?"

- "With your signature on the forms I have provided, you will see the productivity of the department increase."

Generally, the last line of your conclusion is called the tag line and it is important that you give it special attention. Other forms of tag lines that we know of include the tag line of movies. Generally these tag lines are written in such a way as to entice you to want to see the movie. The same holds true with the conclusion. Using the tag line there are three important things that it must do in your persuasive letter:

- It must make the reader agree with you, or at least be better disposed to agreeing with you.

- It must magnify the points you made in the body.

- It puts your readers in the proper mood to agree with you.

Lastly, to make your conclusion the most effective that it can be, it should accomplish the following tasks:

- It will remind the reader about the most important parts of your conclusion.

- It will creatively restate the main idea of your essay, which is your position and what you want the reader to agree with.

- It will leave the reader more interested in the idea that you are trying to convince them to support.

- It brings up a call to action for the reader.

Your conclusion is very important, so take the time to word it the best way possible. A strong conclusion has the ability to fulfill your persuasive writing completely and make a large impact on your reader.

- Course Catalog

- Group Discounts

- Gift Certificates

- For Libraries

- CEU Verification

- Medical Terminology

- Accounting Course

- Writing Basics

- QuickBooks Training

- Proofreading Class

- Sensitivity Training

- Excel Certificate

- Teach Online

- Terms of Service

- Privacy Policy

ATLANTA, MAY 23-24 PUBLIC SPEAKING CLASS IS ALMOST FULL! RESERVE YOUR SPOT NOW

- Public Speaking Classes

- Corporate Presentation Training

- Online Public Speaking Course

- Northeast Region

- Midwest Region

- Southeast Region

- Central Region

- Western Region

- Presentation Skills

- 101 Public Speaking Tips

- Fear of Public Speaking

Persuasive Speech: How to Write an Effective Persuasive Speech

Most often, it actually causes the other person to want to play “Devil’s advocate” and argue with you. In this article, we are going to show you a simple way to win people to your way of thinking without raising resentment. If you use this technique, your audience will actually WANT to agree with you! The process starts with putting yourself in the shoes of your listener and looking at things from their point of view.

Background About How to Write a Persuasive Speech. Facts Aren’t Very Persuasive.

Most people think that a single fact is good, additional facts are better, and too many facts are just right. So, the more facts you can use to prove your point, the better chance you have of convincing the other person that you are right. The HUGE error in this logic, though, is that if you prove that you are right, you are also proving that the other person is wrong. People don’t like it when someone proves that they are wrong. So, we prove our point, the other person is likely to feel resentment. When resentment builds, it leads to anger. Once anger enters the equation, logic goes right out the window.

In addition, when people use a “fact” or “Statistic” to prove a point, the audience has a natural reaction to take a contrary side of the argument. For instance, if I started a statement with, “I can prove to you beyond a doubt that…” before I even finish the statement, there is a good chance that you are already trying to think of a single instance where the statement is NOT true. This is a natural response. As a result, the thing that we need to realize about being persuasive is that the best way to persuade another person is to make the person want to agree with us. We do this by showing the audience how they can get what they want if they do what we want.

You may also like How to Design and Deliver a Memorable Speech .

A Simple 3-Step Process to Create a Persuasive Presentation

The process below is a good way to do both.

Step One: Start Your Persuasive Speech with an Example or Story

When you write an effective persuasive speech, stories are vital. Stories and examples have a powerful way to capture an audience’s attention and set them at ease. They get the audience interested in the presentation. Stories also help your audience see the concepts you are trying to explain in a visual way and make an emotional connection. The more details that you put into your story, the more vivid the images being created in the minds of your audience members.

This concept isn’t mystical or anything. It is science. When we communicate effectively with another person, the purpose is to help the listener picture a concept in his/her mind that is similar to the concept in the speaker’s mind. The old adage is that a “picture is worth 1000 words.” Well, an example or a story is a series of moving pictures. So, a well-told story is worth thousands of words (facts).

By the way, there are a few additional benefits of telling a story. Stories help you reduce nervousness, make better eye contact, and make for a strong opening. For additional details, see Storytelling in Speeches .

I’ll give you an example.

Factual Argument: Seatbelts Save Lives

- 53% of all motor vehicle fatalities from last years were people who weren’t wearing seatbelts.

- People not wearing seatbelts are 30 times more likely to be ejected from the vehicle.

- In a single year, crash deaths and injuries cost us over $70 billion dollars.

These are actual statistics. However, when you read each bullet point, you are likely to be a little skeptical. For instance, when you see the 53% statistic, you might have had the same reaction that I did. You might be thinking something like, “Isn’t that right at half? Doesn’t that mean that the other half WERE wearing seatbelts?” When you see the “30 times more likely” statistic, you might be thinking, “That sounds a little exaggerated. What are the actual numbers?” Looking at the last statistic, we’d likely want to know exactly how the reporter came to that conclusion.

As you can see, if you are a believer that seatbelts save lives, you will likely take the numbers at face value. If you don’t like seatbelts, you will likely nitpick the finer points of each statistic. The facts will not likely persuade you.

Example Argument: Seatbelts Save Lives

When I came to, I tried to open my door. The accident sealed it shut. The windshield was gone. So I took my seatbelt off and scrambled out the hole. The driver of the truck was a bloody mess. His leg was pinned under the steering wheel.

The firefighters came a few minutes later, and it took them over 30 minutes to cut the metal from around his body to free him.

A Sheriff’s Deputy saw a cut on my face and asked if I had been in the accident. I pointed to my truck. His eyes became like saucers. “You were in that vehicle?”

I nodded. He rushed me to an ambulance. I had actually ruptured my colon, and I had to have surgery. I was down for a month or so, but I survived. In fact, I survived with very few long-term challenges from the accident.

The guy who hit me wasn’t so lucky. He wasn’t wearing a seatbelt. The initial impact of the accident was his head on the steering wheel and then the windshield. He had to have a number of facial surgeries. The only reason he remained in the truck was his pinned leg. For me, the accident was a temporary trauma. For him, it was a life-long tragedy.

The Emotional Difference is the Key

As you can see, there are major differences between the two techniques. The story gives lots of memorable details along with an emotion that captures the audience. If you read both examples, let me ask you a couple of questions. Without looking back up higher on the page, how long did it take the firefighters to cut the other driver from the car? How many CDs did I have? There is a good chance that these two pieces of data came to you really quickly. You likely remembered this data, even though, the data wasn’t exactly important to the story.

However, if I asked you how much money was lost last year as a result of traffic accidents, you might struggle to remember that statistic. The CDs and the firefighters were a part of a compelling story that made you pay attention. The money lost to accidents was just a statistic thrown at you to try to prove that a point was true.

The main benefit of using a story, though, is that when we give statistics (without a story to back them up,) the audience becomes argumentative. However, when we tell a story, the audience can’t argue with us. The audience can’t come to me after I told that story and say, “It didn’t take 30 minutes to cut the guy out of the car. He didn’t have to have a bunch of reconstructive surgeries. The Deputy didn’t say those things to you! The audience can’t argue with the details of the story, because they weren’t there.

Step 2: After the Story, Now, Give Your Advice

When most people write a persuasive presentation, they start with their opinion. Again, this makes the listener want to play Devil’s advocate. By starting with the example, we give the listener a simple way to agree with us. They can agree that the story that we told was true. So, now, finish the story with your point or your opinion. “So, in my opinion, if you wear a seatbelt, you’re more likely to avoid serious injury in a severe crash.”

By the way, this technique is not new. It has been around for thousands of years. Aesop was a Greek slave over 500 years before Christ. His stories were passed down verbally for hundreds of years before anyone ever wrote them down in a collection. Today, when you read an Aesop fable, you will get 30 seconds to two minutes of the story first. Then, at the conclusion, almost as a post-script, you will get the advice. Most often, this advice comes in the form of, “The moral of the story is…” You want to do the same in your persuasive presentations. Spend most of the time on the details of the story. Then, spend just a few seconds in the end with your morale.

Step 3: End with the Benefit to the Audience

So, the moral of the story is to wear your seatbelt. If you do that, you will avoid being cut out of your car and endless reconstructive surgeries .

Now, instead of leaving your audience wanting to argue with you, they are more likely to be thinking, “Man, I don’t want to be cut out of my car or have a bunch of facial surgeries.”

The process is very simple. However, it is also very powerful.

How to Write a Successful Persuasive Speech Using the “Breadcrumb” Approach

Once you understand the concept above, you can create very powerful persuasive speeches by linking a series of these persuasive stories together. I call this the breadcrumb strategy. Basically, you use each story as a way to move the audience closer to the ultimate conclusion that you want them to draw. Each story gains a little more agreement.

So, first, just give a simple story about an easy to agree with concept. You will gain agreement fairly easily and begin to also create an emotional appeal. Next, use an additional story to gain additional agreement. If you use this process three to five times, you are more likely to get the audience to agree with your final conclusion. If this is a formal presentation, just make your main points into the persuasive statements and use stories to reinforce the points.

Here are a few persuasive speech examples using this approach.

An Example of a Persuasive Public Speaking Using Breadcrumbs

Marijuana Legalization is Causing Huge Problems in Our Biggest Cities Homelessness is Out of Control in First States to Legalize Marijuana Last year, my family and I took a mini-vacation to Colorado Springs. I had spent a summer in Colorado when I was in college, so I wanted my family to experience the great time that I had had there as a youth. We were only there for four days, but we noticed something dramatic had happened. There were homeless people everywhere. Keep in mind, this wasn’t Denver, this was Colorado City. The picturesque landscape was clouded by ripped sleeping bags on street corners, and trash spread everywhere. We were downtown, and my wife and daughter wanted to do some shopping. My son and I found a comic book store across the street to browse in. As we came out, we almost bumped into a dirty man in torn close. He smiled at us, walked a few feet away from the door, and lit up a joint. He sat on the corner smoking it. As my son and I walked the 1/4 mile back to the store where we left my wife and daughter, we stepped over and walked around over a dozen homeless people camped out right in the middle of the town. This was not the Colorado that I remembered. From what I’ve heard, it has gotten even worse in the last year. So, if you don’t want to dramatically increase your homelessness population, don’t make marijuana legal in your state. DUI Instances and Traffic Accidents Have Increased in Marijuana States I was at the airport waiting for a flight last week, and the guy next to me offered me his newspaper. I haven’t read a newspaper in years, but he seemed so nice that I accepted. It was a copy of the USA Today, and it was open to an article about the rise in unintended consequences from legalizing marijuana. Safety officials and police in Colorado, Nevada, Washington, and Oregon, the first four state to legalize recreational marijuana, have reported a 6% increase in traffic accidents in the last few years. Although the increase (6%) doesn’t seem very dramatic, it was notable because the rate of accidents had been decreasing in each of the states for decades prior to the law change. Assuming that only one of the two parties involved in these new accidents was under the influence, that means that people who aren’t smoking marijuana are being negatively affected by the legalization. So, if you don’t want to increase your chances of being involved in a DUI incident, don’t legalize marijuana. (Notice how I just used an article as my evidence, but to make it more memorable, I told the story about how I came across the article. It is also easier to deliver this type of data because you are just relating what you remember about the data, not trying to be an expert on the data itself.) Marijuana is Still Largely Unregulated Just before my dad went into hospice care, he was in a lot of pain. He would take a prescription painkiller before bed to sleep. One night, my mom called frantically. Dad was in a catatonic state and wasn’t responsive. I rushed over. The hospital found that Dad had an unusually high amount of painkillers in his bloodstream. His regular doctor had been on vacation, and the fill-in doctor had prescribed a much higher dosage of the painkiller by accident. His original prescription was 2.5 mg, and the new prescription was 10 mg. Since dad was in a lot of pain most nights, he almost always took two tablets. He was also on dialysis, so his kidneys weren’t filtering out the excess narcotic each day. He had actually taken 20 MG (instead of 5 MG) on Friday night and another 20 mg on Saturday. Ordinarily, he would have had, at max, 15 mg of the narcotic in his system. Because of the mistake, though, he had 60 MGs. My point is that the narcotics that my dad was prescribed were highly regulated medicines under a doctor’s care, and a mistake was still made that almost killed him. With marijuana, there is really no way of knowing how much narcotic is in each dosage. So, mistakes like this are much more likely. So, in conclusion, legalizing marijuana can increase homelessness, increase the number of impaired drivers, and cause accidental overdoses.

If you use this breadcrumb approach, you are more likely to get at least some agreement. Even if the person disagrees with your conclusion, they are still likely to at least see your side. So, the person may say something like, I still disagree with you, but I totally see your point. That is still a step in the right direction.

For Real-World Practice in How to Design Persuasive Presentations Join Us for a Class

Our instructors are experts at helping presenters design persuasive speeches. We offer the Fearless Presentations ® classes in cities all over the world about every three to four months. In addition to helping you reduce nervousness, your instructor will also show you secrets to creating a great speech. For details about any of the classes, go to our Presentation Skills Class web page.

For additional details, see Persuasive Speech Outline Example .

Podcasts , presentation skills

View More Posts By Category: Free Public Speaking Tips | leadership tips | Online Courses | Past Fearless Presentations ® Classes | Podcasts | presentation skills | Uncategorized

Improve your practice.

Enhance your soft skills with a range of award-winning courses.

Persuasive Speech Outline, with Examples

March 17, 2021 - Gini Beqiri

A persuasive speech is a speech that is given with the intention of convincing the audience to believe or do something. This could be virtually anything – voting, organ donation, recycling, and so on.

A successful persuasive speech effectively convinces the audience to your point of view, providing you come across as trustworthy and knowledgeable about the topic you’re discussing.

So, how do you start convincing a group of strangers to share your opinion? And how do you connect with them enough to earn their trust?

Topics for your persuasive speech

We’ve made a list of persuasive speech topics you could use next time you’re asked to give one. The topics are thought-provoking and things which many people have an opinion on.

When using any of our persuasive speech ideas, make sure you have a solid knowledge about the topic you’re speaking about – and make sure you discuss counter arguments too.

Here are a few ideas to get you started:

- All school children should wear a uniform

- Facebook is making people more socially anxious

- It should be illegal to drive over the age of 80

- Lying isn’t always wrong

- The case for organ donation

Read our full list of 75 persuasive speech topics and ideas .

Preparation: Consider your audience

As with any speech, preparation is crucial. Before you put pen to paper, think about what you want to achieve with your speech. This will help organise your thoughts as you realistically can only cover 2-4 main points before your audience get bored .

It’s also useful to think about who your audience are at this point. If they are unlikely to know much about your topic then you’ll need to factor in context of your topic when planning the structure and length of your speech. You should also consider their:

- Cultural or religious backgrounds

- Shared concerns, attitudes and problems

- Shared interests, beliefs and hopes

- Baseline attitude – are they hostile, neutral, or open to change?

The factors above will all determine the approach you take to writing your speech. For example, if your topic is about childhood obesity, you could begin with a story about your own children or a shared concern every parent has. This would suit an audience who are more likely to be parents than young professionals who have only just left college.

Remember the 3 main approaches to persuade others

There are three main approaches used to persuade others:

The ethos approach appeals to the audience’s ethics and morals, such as what is the ‘right thing’ to do for humanity, saving the environment, etc.

Pathos persuasion is when you appeal to the audience’s emotions, such as when you tell a story that makes them the main character in a difficult situation.

The logos approach to giving a persuasive speech is when you appeal to the audience’s logic – ie. your speech is essentially more driven by facts and logic. The benefit of this technique is that your point of view becomes virtually indisputable because you make the audience feel that only your view is the logical one.

- Ethos, Pathos, Logos: 3 Pillars of Public Speaking and Persuasion

Ideas for your persuasive speech outline

1. structure of your persuasive speech.

The opening and closing of speech are the most important. Consider these carefully when thinking about your persuasive speech outline. A strong opening ensures you have the audience’s attention from the start and gives them a positive first impression of you.

You’ll want to start with a strong opening such as an attention grabbing statement, statistic of fact. These are usually dramatic or shocking, such as:

Sadly, in the next 18 minutes when I do our chat, four Americans that are alive will be dead from the food that they eat – Jamie Oliver

Another good way of starting a persuasive speech is to include your audience in the picture you’re trying to paint. By making them part of the story, you’re embedding an emotional connection between them and your speech.

You could do this in a more toned-down way by talking about something you know that your audience has in common with you. It’s also helpful at this point to include your credentials in a persuasive speech to gain your audience’s trust.

Obama would spend hours with his team working on the opening and closing statements of his speech.

2. Stating your argument

You should pick between 2 and 4 themes to discuss during your speech so that you have enough time to explain your viewpoint and convince your audience to the same way of thinking.

It’s important that each of your points transitions seamlessly into the next one so that your speech has a logical flow. Work on your connecting sentences between each of your themes so that your speech is easy to listen to.

Your argument should be backed up by objective research and not purely your subjective opinion. Use examples, analogies, and stories so that the audience can relate more easily to your topic, and therefore are more likely to be persuaded to your point of view.

3. Addressing counter-arguments

Any balanced theory or thought addresses and disputes counter-arguments made against it. By addressing these, you’ll strengthen your persuasive speech by refuting your audience’s objections and you’ll show that you are knowledgeable to other thoughts on the topic.

When describing an opposing point of view, don’t explain it in a bias way – explain it in the same way someone who holds that view would describe it. That way, you won’t irritate members of your audience who disagree with you and you’ll show that you’ve reached your point of view through reasoned judgement. Simply identify any counter-argument and pose explanations against them.

- Complete Guide to Debating

4. Closing your speech

Your closing line of your speech is your last chance to convince your audience about what you’re saying. It’s also most likely to be the sentence they remember most about your entire speech so make sure it’s a good one!

The most effective persuasive speeches end with a call to action . For example, if you’ve been speaking about organ donation, your call to action might be asking the audience to register as donors.

Practice answering AI questions on your speech and get feedback on your performance .

If audience members ask you questions, make sure you listen carefully and respectfully to the full question. Don’t interject in the middle of a question or become defensive.

You should show that you have carefully considered their viewpoint and refute it in an objective way (if you have opposing opinions). Ensure you remain patient, friendly and polite at all times.

Example 1: Persuasive speech outline

This example is from the Kentucky Community and Technical College.

Specific purpose

To persuade my audience to start walking in order to improve their health.

Central idea

Regular walking can improve both your mental and physical health.

Introduction

Let’s be honest, we lead an easy life: automatic dishwashers, riding lawnmowers, T.V. remote controls, automatic garage door openers, power screwdrivers, bread machines, electric pencil sharpeners, etc., etc. etc. We live in a time-saving, energy-saving, convenient society. It’s a wonderful life. Or is it?

Continue reading

Example 2: Persuasive speech

Tips for delivering your persuasive speech

- Practice, practice, and practice some more . Record yourself speaking and listen for any nervous habits you have such as a nervous laugh, excessive use of filler words, or speaking too quickly.

- Show confident body language . Stand with your legs hip width apart with your shoulders centrally aligned. Ground your feet to the floor and place your hands beside your body so that hand gestures come freely. Your audience won’t be convinced about your argument if you don’t sound confident in it. Find out more about confident body language here .

- Don’t memorise your speech word-for-word or read off a script. If you memorise your persuasive speech, you’ll sound less authentic and panic if you lose your place. Similarly, if you read off a script you won’t sound genuine and you won’t be able to connect with the audience by making eye contact . In turn, you’ll come across as less trustworthy and knowledgeable. You could simply remember your key points instead, or learn your opening and closing sentences.

- Remember to use facial expressions when storytelling – they make you more relatable. By sharing a personal story you’ll more likely be speaking your truth which will help you build a connection with the audience too. Facial expressions help bring your story to life and transport the audience into your situation.

- Keep your speech as concise as possible . When practicing the delivery, see if you can edit it to have the same meaning but in a more succinct way. This will keep the audience engaged.

The best persuasive speech ideas are those that spark a level of controversy. However, a public speech is not the time to express an opinion that is considered outside the norm. If in doubt, play it safe and stick to topics that divide opinions about 50-50.

Bear in mind who your audience are and plan your persuasive speech outline accordingly, with researched evidence to support your argument. It’s important to consider counter-arguments to show that you are knowledgeable about the topic as a whole and not bias towards your own line of thought.

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

Margin Size

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

4.3: Body Paragraphs

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 6613

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

In a persuasive essay the body paragraphs are where the writer has the opportunity to argue his or her viewpoint. By the conclusion paragraph, the writer should convince the reader to agree with the argument of the essay. Regardless of a strong thesis, papers with weak body paragraphs fail to explain why the argument of the essay is both true and important. Body paragraphs of a persuasive essay are weak when no quotes or facts are used to support the thesis or when those used are not adequately explained. Occasionally, body paragraphs are also weak because the quotes used detract from rather than support the essay. Thus, it is essential to use appropriate support and to adequately explain your support within your body paragraphs.

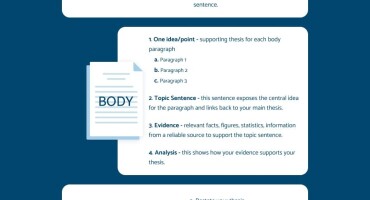

In order to create a body paragraph that is properly supported and explained, it is important to understand the components that make up a strong body paragraph. The bullet points below indicate the essential components of a well-written, well-argued body paragraph.

Body Paragraph:

- Begin with a topic sentence that reflects the argument of the thesis statement.

- Support the argument with useful and informative quotes from sources such as books, journal articles, expert opinions, etc.

- Provide 1-2 sentences explaining each quote.

- Provide 1-3 sentences that indicate the significance of each quote.

- Ensure that the information provided is relevant to the thesis statement.

- End with a transition sentence which leads into the next body paragraph.

Just as your introduction must introduce the topic of your essay, the first sentence of a body paragraph must introduce the argument for that paragraph. For instance, if you were writing a body paragraph for a paper arguing that Avatar is innovative in its use of special effects, one body paragraph may begin with a topic sentence that states, “ Avatar has produced the most life-like animated characters of any movie ever created.” Following this sentence, you would go on to indicate how the movie does this by supporting this one statement. When you place this statement as the opening of your paragraph, not only does your audience know what the paragraph is going to argue, but you can also keep track of your ideas.

Following the topic sentence, you must provide some sort of fact that supports your claim. In the example of the Avatar essay, maybe you would provide a quote from a movie critic or from a prominent special effects person. After your quote or fact, you must always explain what the quote or fact is saying, stressing what you believe is most important about your fact. It is important to remember that your audience may read a quote and decide it is arguing something entirely different than what you think it is arguing. Or, maybe some or your readers think another aspect of your quote is important. If you do not explain the quote and indicate what portion of it is relevant to your argument, then your reader may become confused or may be unconvinced of your point. Consider the possible interpretations for the statement below.

Example: While I did not like the acting in the movie, I enjoyed how life-like the special effects made the animated characters in the film. Without the special effects, the acting would have been boring and the plot would have been unoriginal.

Interestingly, this statement seems to be saying two things at once - that the movie is bad and that the movie is good. On the one hand, the person seems to say that the acting and plot of the movie were both bad. However, on the other hand, the person also says that the special effects more than make up for the bad acting and unoriginal plot. Because of this tension in the quotation, if you used this quote in your Avatar paper, you would need to explain that the special effects in the movie are so good that they make boring movie exciting.

In addition to explaining what this quote is saying, you would also need to indicate why this is important to your argument. When trying to indicate the significance of a fact, it is essential to try to answer the “so what.” Image you have just finished explaining your quote to someone, and he or she has asked you “so what?” The person does not understand why you have explained this quote, not because you have not explained the quote well but because you have not told him or her why he or she needs to know what the quote means. This, the answer to the “so what,” is the significance of your paper and is essentially your argument within the body paragraphs. However, it is important to remember that generally a body paragraph will contain more than one quotation or piece of support. Thus, you must repeat the Quotation-Explanation-Significance formula several times within your body paragraph to argue the one sub-point indicated in your topic sentence. Below is an example of a properly written body paragraph.

A Comprehensive Guide to Writing a Persuasive Speech

Hrideep barot.

- Speech Writing

The term Persuasion means the efforts to change the attitudes or opinions of others through various means.

It is present everywhere: election campaigns, salesmen trying to sell goods by giving offers, public health campaigns to quit smoking or to wear masks in the public spaces, or even at the workplace; when an employee tries to persuade others to agree to their point in a meeting.

How do they manage to convince us so subtly? You guessed it right! They engage in what is called Persuasive Speech.

Persuasive Speech is a category of speech that attempts to influence the listener’s beliefs, attitudes, thoughts, and ultimately, behavior.

They are used in all contexts and situations . It can be informal , a teenager attempting to convince his or her parents for a sleepover at a friend’s house.

It can also be formal , President or Prime Minister urging the citizens to abide by the new norms.

But not to confuse these with informative speeches! These also aim to inform the audience about a particular topic or event, but they lack any attempt at persuasion.

The most typical setting where this kind of speech is practiced is in schools and colleges.

An effective speech combines both the features of an informative and persuasive speech for a better takeaway from an audience’s point of view.

However, writing and giving a persuasive speech are different in the sense that you as a speaker have limited time to call people to action.

Also, according to the context or situation, you may not be able to meet your audience several times, unlike TV ads, which the audience sees repeatedly and hence believes the credibility of the product.

So, how to write and deliver an effective persuasive speech?

How to start a persuasive speech? What are the steps of writing a persuasive speech? What are some of the tricks and tips of persuasion?

Read along till the end to explore the different dimensions and avenues of the science of giving a persuasive speech.

THINGS TO KEEP IN MIND BEFORE WRITING A PERSUASIVE SPEECH

1. get your topic right, passion and genuine interest in your topic.

It is very important that you as a speaker are interested in the chosen topic and in the subsequent arguments you are about to put forward. If you are not interested in what you are saying, then how will the audience feel the same?

Passion towards the topic is one of the key requirements for a successful speech as your audience will see how passionate and concerned you are towards the issue and will infer you as a genuine and credible person.

The audience too will get in the mood and connect to you on an emotional level, empathizing with you; as a result of which will understand your point of view and are likely to agree to your argument.

Consider this example: your friend is overflowing with joy- is happy, smiling, and bubbling with enthusiasm.

Before even asking the reason behind being so happy, you “catch the mood”; i.e., you notice that your mood has been boosted as a result of seeing your friend happy.

Why does it happen so? The reason is that we are influenced by other people’s moods and emotions.

It also means that our mood affects people around us, which is the reason why speaking with emotions and passion is used by many successful public speakers.

Another reason is that other’s emotions give an insight into how one should feel and react. We interpret other’s reactions as a source of information about how we should feel.

So, if someone shows a lot of anxiety or excitement while speaking, we conclude that the issue is very important and we should do something about it, and end up feeling similar reactions.

Meaningful and thought-provoking

Choose a topic that is meaningful to you and your audience. It should be thought-provoking and leave the audience thinking about the points put forward in your speech.

Topics that are personally or nationally relevant and are in the talks at the moment are good subjects to start with.

If you choose a controversial topic like “should euthanasia be legalized?”, or” is our nation democratic?”, it will leave a dramatic impact on your audience.

However, be considerate in choosing a sensitive topic, since it can leave a negative impression on your listeners. But if worded in a neutral and unbiased manner, it can work wonders.

Also, refrain from choosing sensitive topics like the reality of religion, sexuality, etc.

2. Research your topic thoroughly

Research on persuasion conducted by Hovland, Janis, and Kelley states that credible communicators are more persuasive than those who are seen as lacking expertise.

Even if you are not an expert in the field of your topic, mentioning information that is backed by research or stating an expert’s opinion on the issue will make you appear as a knowledgeable and credible person.

How to go about researching? Many people think that just googling about a topic and inferring 2-3 articles will be enough. But this is not so.

For writing and giving an effective speech, thorough research is crucial for you as a speaker to be prepared and confident.

Try to find as many relevant points as possible, even if it is against your viewpoint. If you can explain why the opposite viewpoint is not correct, it will give the audience both sides to an argument and will make decision-making easier.

Also, give credit to the source of your points during your speech, by mentioning the original site, author, or expert, so the audience will know that these are reliable points and not just your opinion, and will be more ready to believe them since they come from an authority.

Other sources for obtaining data for research are libraries and bookstores, magazines, newspapers, google scholar, research journals, etc.

Analyze your audience

Know who comprises your audience so that you can alter your speech to meet their requirements.

Demographics like age group, gender ratio, the language with which they are comfortable, their knowledge about the topic, the region and community to which they belong; are all important factors to be considered before writing your speech.

Ask yourself these questions before sitting down to write:

Is the topic of argument significant to them? Why is it significant? Would it make sense to them? Is it even relevant to them?

In the end, the speech is about the audience and not you. Hence, make efforts to know your audience.

This can be done by surveying your audience way before the day of giving your speech. Short polls and registration forms are an effective way to know your audience.

They ensure confidentiality and maintain anonymity, eliminating social desirability bias on part of the audience, and will likely receive honest answers.

OUTLINE OF A PERSUASIVE SPEECH

Most speeches follow the pattern of Introduction, Body and Conclusion.

However, persuasive speeches have a slightly different pathway.

INTRODUCTION

BODY OR SUPPORTING STATEMENTS( ATLEAST 3 ARGUMENTS)

CONCLUSION OR A CALL TO ACTION

1. INTRODUCTION

Grab attention of your audience.

The first few lines spoken by a speaker are the deciding factor that can make or break a speech.

Hence, if you nail the introduction, half of the task has already been done, and you can rest assured.

No one likes to be silent unless you are an introvert. But the audience expects that the speaker will go on stage and speak. But what if the speaker just goes and remains silent?

Chances are high that the audience will be in anticipation of what you are about to speak and their sole focus will be on you.

This sets the stage.

Use quotes that are relevant and provocative to set the tone of your speech. It will determine the mood of your audience and get them ready to receive information.

An example can be “The only impossible journey is the one you never begin” and then state who gave it, in this case, Tony Robbins, an American author.

Use what-if scenarios

Another way to start your speech is by using what-if scenarios and phrases like “suppose if your home submerges in water one day due to global warming…”.

This will make them the center of attention and at the same time grabbing their attention.

Use personal anecdotes

Same works with personal experiences and stories.

Everyone loves listening to first-hand experiences or a good and interesting story. If you are not a great storyteller, visual images and videos will come to your rescue.

After you have successfully grabbed and hooked your audience, the next and last step of the introduction is introducing your thesis statement.

What is a thesis statement?

It introduces the topic to your audience and is one of the central elements of any persuasive speech.

It is usually brief, not more than 3 sentences, and gives the crux of your speech outline.

How to make a thesis statement?

Firstly, research all possible opinions and views about your topic. See which opinion you connect with, and try to summarize them.

After you do this, you will get a clear idea of what side you are on and this will become your thesis statement.

However, the thesis should answer the question “why” and “how”.

So, for instance, if you choose to speak on the topic of the necessity of higher education, your thesis statement could be something like this:

Although attending university and getting a degree is essential for overall development, not every student must be pushed to join immediately after graduating from school.

And then you can structure your speech containing the reasons why every student should not be rushed into joining a university.

3. BODY OF THE SPEECH

The body contains the actual reasons to support your thesis.

Ideally, the body should contain at least 3 reasons to support your argument.

So, for the above-mentioned thesis, you can support it with possible alternatives, which will become your supporting statements.

The option of a gap year to relax and decide future goals, gaining work experience and then joining the university for financial reasons, or even joining college after 25 or 35 years.

These become your supporting reasons and answers the question “why”.

Each reason has to be resourcefully elaborated, with explaining why you support and why the other or anti-thesis is not practical.

At this point, you have the option of targeting your audience’s ethos, pathos, or logos.

Ethos is the ethical side of the argument. It targets morals and puts forth the right thing or should be.

This technique is highly used in the advertising industry.

Ever wondered why celebrities, experts, and renowned personalities are usually cast as brand ambassadors.?

The reason: they are liked by the masses and exhibit credibility and trust.

Advertisers endorse their products via a celebrity to try to show that the product is reliable and ethical.

The same scenario is seen in persuasive speeches. If the speaker is well-informed and provides information that is backed by research, chances are high that the audience will follow it.

Pathos targets the emotional feelings of the audience.

This is usually done by narrating a tragic or horrifying anecdote and leaves the listener moved by using an emotional appeal to call people to action.

The common emotions targeted by the speaker include the feeling of joy, love, sadness, anger, pity, and loneliness.

All these emotions are best expressed in stories or personal experiences.

Stories give life to your argument, making the audience more involved in the matter and arousing sympathy and empathy.

Visuals and documentaries are other mediums through which a speaker can attract the audience’s emotions.

What was your reaction after watching an emotional documentary? Did you not want to do something about the problem right away?

Emotions have the power to move people to action.

The last technique is using logos, i.e., logic. This includes giving facts and practical aspects of why this is to be done or why such a thing is the most practical.

It is also called the “logical appeal”.

This can be done by giving inductive or deductive reasoning.

Inductive reasoning involves the speaker taking a specific example or case study and then generalizing or drawing conclusions from it.

For instance, a speaker tells a case study of a student who went into depression as the child wasn’t able to cope with back-to-back stress.

This problem will be generalized and concluded that gap year is crucial for any child to cope with and be ready for the challenges in a university.

On the other hand, deductive reasoning involves analyzing general assumptions and theories and then arriving at a logical conclusion.

So, in this case, the speaker can give statistics of the percentage of university students feeling drained due to past exams and how many felt that they needed a break.

This general data will then be personalized to conclude how there is a need for every student to have a leisure break to refresh their mind and avoid having burned out.

Using any of these 3 techniques, coupled with elaborate anecdotes and supporting evidence, at the same time encountering counterarguments will make the body of your speech more effective.

4. CONCLUSION

Make sure to spend some time thinking through your conclusion, as this is the part that your audience will remember the most and is hence, the key takeaway of your entire speech.

Keep it brief, and avoid being too repetitive.

It should provide the audience with a summary of the points put across in the body, at the same time calling people to action or suggesting a possible solution and the next step to be taken.

Remember that this is your last chance to convince, hence make sure to make it impactful.

Include one to two relevant power or motivational quotes, and end by thanking the audience for being patient and listening till the end.

Watch this clip for a better understanding.

TIPS AND TRICKS OF PERSUASION

Start strong.

A general pattern among influential speeches is this: all start with a powerful and impactful example, be it statistics about the issue, using influential and meaning statements and quotes, or asking a rhetorical question at the beginning of their speech.

Why do they do this? It demonstrates credibility and creates a good impression- increasing their chance of persuading the audience.

Hence, start in such a manner that will hook the audience to your speech and people would be curious to know what you are about to say or how will you end it.

Keep your introduction short

Keep your introduction short, and not more than 10-15% of your speech.

If your speech is 2000 words, then your introduction should be a maximum of 200-250 words.

Or if you are presenting for 10 minutes, your introduction should be a maximum of 2 minutes. This will give you time to state your main points and help you manage your time effectively.

Be clear and concise

Use the correct vocabulary to fit in, at the same time making sure to state them clearly, without beating around the bush.

This will make the message efficient and impactful.

Answer the question “why”

Answer the question “why” before giving solutions or “how”.

Tell them why is there a need to change. Then give them all sides of the point.

It is important to state what is wrong and not just what ought to be or what is right, in an unopinionated tone.

Unless and until people don’t know the other side of things, they simply will not change.

Suggest solutions

Once you have stated the problem, you imply or hint at the solution.

Never state solutions, suggest them; leaving the decision up to the audience.

You can hint at solutions: “don’t you think it is a good idea to…?” or “is it wrong to say that…?”, instead of just stating solutions.

Use power phrases

Certain power-phrases come in handy, which can make the audience take action.

Using the power phrase “because” is very impactful in winning and convincing others.

This phrase justifies the action associated with it and gives us an understanding of why is it correct.

For instance, the phrase “can you give me a bite of your food?” does not imply attitude change.

But using “may I have a bite of your food because I haven’t eaten breakfast?” is more impactful and the person will likely end up sharing food if you use this power- phrase, because it is justifying your request.

Another power-phrase is “I understand, but…”.

This involves you agreeing with the opposite side of the argument and then stating your side or your point of view.

This will encourage your audience to think from the other side of the spectrum and are likely to consider your argument put forth in the speech.

Use power words