Experimental Research Design — 6 mistakes you should never make!

Since school days’ students perform scientific experiments that provide results that define and prove the laws and theorems in science. These experiments are laid on a strong foundation of experimental research designs.

An experimental research design helps researchers execute their research objectives with more clarity and transparency.

In this article, we will not only discuss the key aspects of experimental research designs but also the issues to avoid and problems to resolve while designing your research study.

Table of Contents

What Is Experimental Research Design?

Experimental research design is a framework of protocols and procedures created to conduct experimental research with a scientific approach using two sets of variables. Herein, the first set of variables acts as a constant, used to measure the differences of the second set. The best example of experimental research methods is quantitative research .

Experimental research helps a researcher gather the necessary data for making better research decisions and determining the facts of a research study.

When Can a Researcher Conduct Experimental Research?

A researcher can conduct experimental research in the following situations —

- When time is an important factor in establishing a relationship between the cause and effect.

- When there is an invariable or never-changing behavior between the cause and effect.

- Finally, when the researcher wishes to understand the importance of the cause and effect.

Importance of Experimental Research Design

To publish significant results, choosing a quality research design forms the foundation to build the research study. Moreover, effective research design helps establish quality decision-making procedures, structures the research to lead to easier data analysis, and addresses the main research question. Therefore, it is essential to cater undivided attention and time to create an experimental research design before beginning the practical experiment.

By creating a research design, a researcher is also giving oneself time to organize the research, set up relevant boundaries for the study, and increase the reliability of the results. Through all these efforts, one could also avoid inconclusive results. If any part of the research design is flawed, it will reflect on the quality of the results derived.

Types of Experimental Research Designs

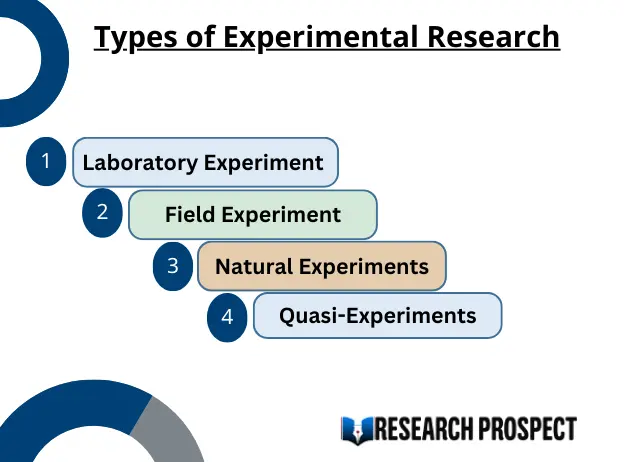

Based on the methods used to collect data in experimental studies, the experimental research designs are of three primary types:

1. Pre-experimental Research Design

A research study could conduct pre-experimental research design when a group or many groups are under observation after implementing factors of cause and effect of the research. The pre-experimental design will help researchers understand whether further investigation is necessary for the groups under observation.

Pre-experimental research is of three types —

- One-shot Case Study Research Design

- One-group Pretest-posttest Research Design

- Static-group Comparison

2. True Experimental Research Design

A true experimental research design relies on statistical analysis to prove or disprove a researcher’s hypothesis. It is one of the most accurate forms of research because it provides specific scientific evidence. Furthermore, out of all the types of experimental designs, only a true experimental design can establish a cause-effect relationship within a group. However, in a true experiment, a researcher must satisfy these three factors —

- There is a control group that is not subjected to changes and an experimental group that will experience the changed variables

- A variable that can be manipulated by the researcher

- Random distribution of the variables

This type of experimental research is commonly observed in the physical sciences.

3. Quasi-experimental Research Design

The word “Quasi” means similarity. A quasi-experimental design is similar to a true experimental design. However, the difference between the two is the assignment of the control group. In this research design, an independent variable is manipulated, but the participants of a group are not randomly assigned. This type of research design is used in field settings where random assignment is either irrelevant or not required.

The classification of the research subjects, conditions, or groups determines the type of research design to be used.

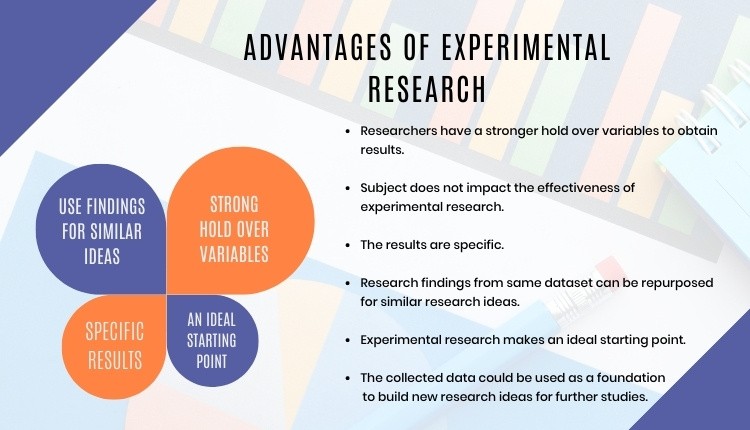

Advantages of Experimental Research

Experimental research allows you to test your idea in a controlled environment before taking the research to clinical trials. Moreover, it provides the best method to test your theory because of the following advantages:

- Researchers have firm control over variables to obtain results.

- The subject does not impact the effectiveness of experimental research. Anyone can implement it for research purposes.

- The results are specific.

- Post results analysis, research findings from the same dataset can be repurposed for similar research ideas.

- Researchers can identify the cause and effect of the hypothesis and further analyze this relationship to determine in-depth ideas.

- Experimental research makes an ideal starting point. The collected data could be used as a foundation to build new research ideas for further studies.

6 Mistakes to Avoid While Designing Your Research

There is no order to this list, and any one of these issues can seriously compromise the quality of your research. You could refer to the list as a checklist of what to avoid while designing your research.

1. Invalid Theoretical Framework

Usually, researchers miss out on checking if their hypothesis is logical to be tested. If your research design does not have basic assumptions or postulates, then it is fundamentally flawed and you need to rework on your research framework.

2. Inadequate Literature Study

Without a comprehensive research literature review , it is difficult to identify and fill the knowledge and information gaps. Furthermore, you need to clearly state how your research will contribute to the research field, either by adding value to the pertinent literature or challenging previous findings and assumptions.

3. Insufficient or Incorrect Statistical Analysis

Statistical results are one of the most trusted scientific evidence. The ultimate goal of a research experiment is to gain valid and sustainable evidence. Therefore, incorrect statistical analysis could affect the quality of any quantitative research.

4. Undefined Research Problem

This is one of the most basic aspects of research design. The research problem statement must be clear and to do that, you must set the framework for the development of research questions that address the core problems.

5. Research Limitations

Every study has some type of limitations . You should anticipate and incorporate those limitations into your conclusion, as well as the basic research design. Include a statement in your manuscript about any perceived limitations, and how you considered them while designing your experiment and drawing the conclusion.

6. Ethical Implications

The most important yet less talked about topic is the ethical issue. Your research design must include ways to minimize any risk for your participants and also address the research problem or question at hand. If you cannot manage the ethical norms along with your research study, your research objectives and validity could be questioned.

Experimental Research Design Example

In an experimental design, a researcher gathers plant samples and then randomly assigns half the samples to photosynthesize in sunlight and the other half to be kept in a dark box without sunlight, while controlling all the other variables (nutrients, water, soil, etc.)

By comparing their outcomes in biochemical tests, the researcher can confirm that the changes in the plants were due to the sunlight and not the other variables.

Experimental research is often the final form of a study conducted in the research process which is considered to provide conclusive and specific results. But it is not meant for every research. It involves a lot of resources, time, and money and is not easy to conduct, unless a foundation of research is built. Yet it is widely used in research institutes and commercial industries, for its most conclusive results in the scientific approach.

Have you worked on research designs? How was your experience creating an experimental design? What difficulties did you face? Do write to us or comment below and share your insights on experimental research designs!

Frequently Asked Questions

Randomization is important in an experimental research because it ensures unbiased results of the experiment. It also measures the cause-effect relationship on a particular group of interest.

Experimental research design lay the foundation of a research and structures the research to establish quality decision making process.

There are 3 types of experimental research designs. These are pre-experimental research design, true experimental research design, and quasi experimental research design.

The difference between an experimental and a quasi-experimental design are: 1. The assignment of the control group in quasi experimental research is non-random, unlike true experimental design, which is randomly assigned. 2. Experimental research group always has a control group; on the other hand, it may not be always present in quasi experimental research.

Experimental research establishes a cause-effect relationship by testing a theory or hypothesis using experimental groups or control variables. In contrast, descriptive research describes a study or a topic by defining the variables under it and answering the questions related to the same.

good and valuable

Very very good

Good presentation.

Rate this article Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published.

Enago Academy's Most Popular Articles

![how to create an experimental research design What is Academic Integrity and How to Uphold it [FREE CHECKLIST]](https://www.enago.com/academy/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/FeatureImages-59-210x136.png)

Ensuring Academic Integrity and Transparency in Academic Research: A comprehensive checklist for researchers

Academic integrity is the foundation upon which the credibility and value of scientific findings are…

- Publishing Research

- Reporting Research

How to Optimize Your Research Process: A step-by-step guide

For researchers across disciplines, the path to uncovering novel findings and insights is often filled…

- Industry News

- Trending Now

Breaking Barriers: Sony and Nature unveil “Women in Technology Award”

Sony Group Corporation and the prestigious scientific journal Nature have collaborated to launch the inaugural…

Achieving Research Excellence: Checklist for good research practices

Academia is built on the foundation of trustworthy and high-quality research, supported by the pillars…

- Promoting Research

Plain Language Summary — Communicating your research to bridge the academic-lay gap

Science can be complex, but does that mean it should not be accessible to the…

Choosing the Right Analytical Approach: Thematic analysis vs. content analysis for…

Comparing Cross Sectional and Longitudinal Studies: 5 steps for choosing the right…

Research Recommendations – Guiding policy-makers for evidence-based decision making

Sign-up to read more

Subscribe for free to get unrestricted access to all our resources on research writing and academic publishing including:

- 2000+ blog articles

- 50+ Webinars

- 10+ Expert podcasts

- 50+ Infographics

- 10+ Checklists

- Research Guides

We hate spam too. We promise to protect your privacy and never spam you.

I am looking for Editing/ Proofreading services for my manuscript Tentative date of next journal submission:

As a researcher, what do you consider most when choosing an image manipulation detector?

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Methodology

Research Design | Step-by-Step Guide with Examples

Published on 5 May 2022 by Shona McCombes . Revised on 20 March 2023.

A research design is a strategy for answering your research question using empirical data. Creating a research design means making decisions about:

- Your overall aims and approach

- The type of research design you’ll use

- Your sampling methods or criteria for selecting subjects

- Your data collection methods

- The procedures you’ll follow to collect data

- Your data analysis methods

A well-planned research design helps ensure that your methods match your research aims and that you use the right kind of analysis for your data.

Table of contents

Step 1: consider your aims and approach, step 2: choose a type of research design, step 3: identify your population and sampling method, step 4: choose your data collection methods, step 5: plan your data collection procedures, step 6: decide on your data analysis strategies, frequently asked questions.

- Introduction

Before you can start designing your research, you should already have a clear idea of the research question you want to investigate.

There are many different ways you could go about answering this question. Your research design choices should be driven by your aims and priorities – start by thinking carefully about what you want to achieve.

The first choice you need to make is whether you’ll take a qualitative or quantitative approach.

Qualitative research designs tend to be more flexible and inductive , allowing you to adjust your approach based on what you find throughout the research process.

Quantitative research designs tend to be more fixed and deductive , with variables and hypotheses clearly defined in advance of data collection.

It’s also possible to use a mixed methods design that integrates aspects of both approaches. By combining qualitative and quantitative insights, you can gain a more complete picture of the problem you’re studying and strengthen the credibility of your conclusions.

Practical and ethical considerations when designing research

As well as scientific considerations, you need to think practically when designing your research. If your research involves people or animals, you also need to consider research ethics .

- How much time do you have to collect data and write up the research?

- Will you be able to gain access to the data you need (e.g., by travelling to a specific location or contacting specific people)?

- Do you have the necessary research skills (e.g., statistical analysis or interview techniques)?

- Will you need ethical approval ?

At each stage of the research design process, make sure that your choices are practically feasible.

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

Within both qualitative and quantitative approaches, there are several types of research design to choose from. Each type provides a framework for the overall shape of your research.

Types of quantitative research designs

Quantitative designs can be split into four main types. Experimental and quasi-experimental designs allow you to test cause-and-effect relationships, while descriptive and correlational designs allow you to measure variables and describe relationships between them.

With descriptive and correlational designs, you can get a clear picture of characteristics, trends, and relationships as they exist in the real world. However, you can’t draw conclusions about cause and effect (because correlation doesn’t imply causation ).

Experiments are the strongest way to test cause-and-effect relationships without the risk of other variables influencing the results. However, their controlled conditions may not always reflect how things work in the real world. They’re often also more difficult and expensive to implement.

Types of qualitative research designs

Qualitative designs are less strictly defined. This approach is about gaining a rich, detailed understanding of a specific context or phenomenon, and you can often be more creative and flexible in designing your research.

The table below shows some common types of qualitative design. They often have similar approaches in terms of data collection, but focus on different aspects when analysing the data.

Your research design should clearly define who or what your research will focus on, and how you’ll go about choosing your participants or subjects.

In research, a population is the entire group that you want to draw conclusions about, while a sample is the smaller group of individuals you’ll actually collect data from.

Defining the population

A population can be made up of anything you want to study – plants, animals, organisations, texts, countries, etc. In the social sciences, it most often refers to a group of people.

For example, will you focus on people from a specific demographic, region, or background? Are you interested in people with a certain job or medical condition, or users of a particular product?

The more precisely you define your population, the easier it will be to gather a representative sample.

Sampling methods

Even with a narrowly defined population, it’s rarely possible to collect data from every individual. Instead, you’ll collect data from a sample.

To select a sample, there are two main approaches: probability sampling and non-probability sampling . The sampling method you use affects how confidently you can generalise your results to the population as a whole.

Probability sampling is the most statistically valid option, but it’s often difficult to achieve unless you’re dealing with a very small and accessible population.

For practical reasons, many studies use non-probability sampling, but it’s important to be aware of the limitations and carefully consider potential biases. You should always make an effort to gather a sample that’s as representative as possible of the population.

Case selection in qualitative research

In some types of qualitative designs, sampling may not be relevant.

For example, in an ethnography or a case study, your aim is to deeply understand a specific context, not to generalise to a population. Instead of sampling, you may simply aim to collect as much data as possible about the context you are studying.

In these types of design, you still have to carefully consider your choice of case or community. You should have a clear rationale for why this particular case is suitable for answering your research question.

For example, you might choose a case study that reveals an unusual or neglected aspect of your research problem, or you might choose several very similar or very different cases in order to compare them.

Data collection methods are ways of directly measuring variables and gathering information. They allow you to gain first-hand knowledge and original insights into your research problem.

You can choose just one data collection method, or use several methods in the same study.

Survey methods

Surveys allow you to collect data about opinions, behaviours, experiences, and characteristics by asking people directly. There are two main survey methods to choose from: questionnaires and interviews.

Observation methods

Observations allow you to collect data unobtrusively, observing characteristics, behaviours, or social interactions without relying on self-reporting.

Observations may be conducted in real time, taking notes as you observe, or you might make audiovisual recordings for later analysis. They can be qualitative or quantitative.

Other methods of data collection

There are many other ways you might collect data depending on your field and topic.

If you’re not sure which methods will work best for your research design, try reading some papers in your field to see what data collection methods they used.

Secondary data

If you don’t have the time or resources to collect data from the population you’re interested in, you can also choose to use secondary data that other researchers already collected – for example, datasets from government surveys or previous studies on your topic.

With this raw data, you can do your own analysis to answer new research questions that weren’t addressed by the original study.

Using secondary data can expand the scope of your research, as you may be able to access much larger and more varied samples than you could collect yourself.

However, it also means you don’t have any control over which variables to measure or how to measure them, so the conclusions you can draw may be limited.

As well as deciding on your methods, you need to plan exactly how you’ll use these methods to collect data that’s consistent, accurate, and unbiased.

Planning systematic procedures is especially important in quantitative research, where you need to precisely define your variables and ensure your measurements are reliable and valid.

Operationalisation

Some variables, like height or age, are easily measured. But often you’ll be dealing with more abstract concepts, like satisfaction, anxiety, or competence. Operationalisation means turning these fuzzy ideas into measurable indicators.

If you’re using observations , which events or actions will you count?

If you’re using surveys , which questions will you ask and what range of responses will be offered?

You may also choose to use or adapt existing materials designed to measure the concept you’re interested in – for example, questionnaires or inventories whose reliability and validity has already been established.

Reliability and validity

Reliability means your results can be consistently reproduced , while validity means that you’re actually measuring the concept you’re interested in.

For valid and reliable results, your measurement materials should be thoroughly researched and carefully designed. Plan your procedures to make sure you carry out the same steps in the same way for each participant.

If you’re developing a new questionnaire or other instrument to measure a specific concept, running a pilot study allows you to check its validity and reliability in advance.

Sampling procedures

As well as choosing an appropriate sampling method, you need a concrete plan for how you’ll actually contact and recruit your selected sample.

That means making decisions about things like:

- How many participants do you need for an adequate sample size?

- What inclusion and exclusion criteria will you use to identify eligible participants?

- How will you contact your sample – by mail, online, by phone, or in person?

If you’re using a probability sampling method, it’s important that everyone who is randomly selected actually participates in the study. How will you ensure a high response rate?

If you’re using a non-probability method, how will you avoid bias and ensure a representative sample?

Data management

It’s also important to create a data management plan for organising and storing your data.

Will you need to transcribe interviews or perform data entry for observations? You should anonymise and safeguard any sensitive data, and make sure it’s backed up regularly.

Keeping your data well organised will save time when it comes to analysing them. It can also help other researchers validate and add to your findings.

On their own, raw data can’t answer your research question. The last step of designing your research is planning how you’ll analyse the data.

Quantitative data analysis

In quantitative research, you’ll most likely use some form of statistical analysis . With statistics, you can summarise your sample data, make estimates, and test hypotheses.

Using descriptive statistics , you can summarise your sample data in terms of:

- The distribution of the data (e.g., the frequency of each score on a test)

- The central tendency of the data (e.g., the mean to describe the average score)

- The variability of the data (e.g., the standard deviation to describe how spread out the scores are)

The specific calculations you can do depend on the level of measurement of your variables.

Using inferential statistics , you can:

- Make estimates about the population based on your sample data.

- Test hypotheses about a relationship between variables.

Regression and correlation tests look for associations between two or more variables, while comparison tests (such as t tests and ANOVAs ) look for differences in the outcomes of different groups.

Your choice of statistical test depends on various aspects of your research design, including the types of variables you’re dealing with and the distribution of your data.

Qualitative data analysis

In qualitative research, your data will usually be very dense with information and ideas. Instead of summing it up in numbers, you’ll need to comb through the data in detail, interpret its meanings, identify patterns, and extract the parts that are most relevant to your research question.

Two of the most common approaches to doing this are thematic analysis and discourse analysis .

There are many other ways of analysing qualitative data depending on the aims of your research. To get a sense of potential approaches, try reading some qualitative research papers in your field.

A sample is a subset of individuals from a larger population. Sampling means selecting the group that you will actually collect data from in your research.

For example, if you are researching the opinions of students in your university, you could survey a sample of 100 students.

Statistical sampling allows you to test a hypothesis about the characteristics of a population. There are various sampling methods you can use to ensure that your sample is representative of the population as a whole.

Operationalisation means turning abstract conceptual ideas into measurable observations.

For example, the concept of social anxiety isn’t directly observable, but it can be operationally defined in terms of self-rating scores, behavioural avoidance of crowded places, or physical anxiety symptoms in social situations.

Before collecting data , it’s important to consider how you will operationalise the variables that you want to measure.

The research methods you use depend on the type of data you need to answer your research question .

- If you want to measure something or test a hypothesis , use quantitative methods . If you want to explore ideas, thoughts, and meanings, use qualitative methods .

- If you want to analyse a large amount of readily available data, use secondary data. If you want data specific to your purposes with control over how they are generated, collect primary data.

- If you want to establish cause-and-effect relationships between variables , use experimental methods. If you want to understand the characteristics of a research subject, use descriptive methods.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, March 20). Research Design | Step-by-Step Guide with Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved 27 May 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/research-methods/research-design/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Experimental Design: Types, Examples & Methods

Saul Mcleod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul Mcleod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

On This Page:

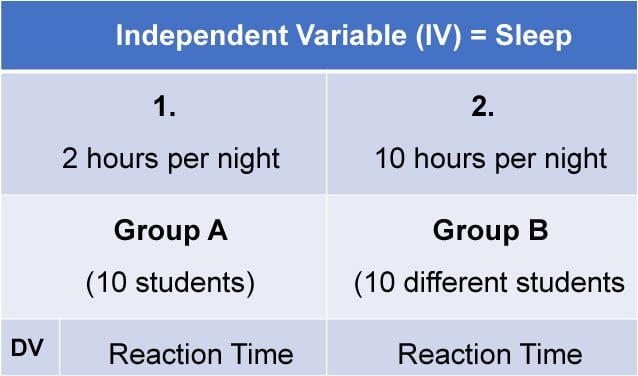

Experimental design refers to how participants are allocated to different groups in an experiment. Types of design include repeated measures, independent groups, and matched pairs designs.

Probably the most common way to design an experiment in psychology is to divide the participants into two groups, the experimental group and the control group, and then introduce a change to the experimental group, not the control group.

The researcher must decide how he/she will allocate their sample to the different experimental groups. For example, if there are 10 participants, will all 10 participants participate in both groups (e.g., repeated measures), or will the participants be split in half and take part in only one group each?

Three types of experimental designs are commonly used:

1. Independent Measures

Independent measures design, also known as between-groups , is an experimental design where different participants are used in each condition of the independent variable. This means that each condition of the experiment includes a different group of participants.

This should be done by random allocation, ensuring that each participant has an equal chance of being assigned to one group.

Independent measures involve using two separate groups of participants, one in each condition. For example:

- Con : More people are needed than with the repeated measures design (i.e., more time-consuming).

- Pro : Avoids order effects (such as practice or fatigue) as people participate in one condition only. If a person is involved in several conditions, they may become bored, tired, and fed up by the time they come to the second condition or become wise to the requirements of the experiment!

- Con : Differences between participants in the groups may affect results, for example, variations in age, gender, or social background. These differences are known as participant variables (i.e., a type of extraneous variable ).

- Control : After the participants have been recruited, they should be randomly assigned to their groups. This should ensure the groups are similar, on average (reducing participant variables).

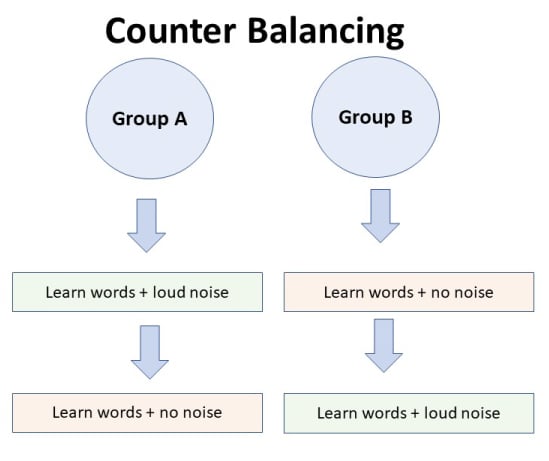

2. Repeated Measures Design

Repeated Measures design is an experimental design where the same participants participate in each independent variable condition. This means that each experiment condition includes the same group of participants.

Repeated Measures design is also known as within-groups or within-subjects design .

- Pro : As the same participants are used in each condition, participant variables (i.e., individual differences) are reduced.

- Con : There may be order effects. Order effects refer to the order of the conditions affecting the participants’ behavior. Performance in the second condition may be better because the participants know what to do (i.e., practice effect). Or their performance might be worse in the second condition because they are tired (i.e., fatigue effect). This limitation can be controlled using counterbalancing.

- Pro : Fewer people are needed as they participate in all conditions (i.e., saves time).

- Control : To combat order effects, the researcher counter-balances the order of the conditions for the participants. Alternating the order in which participants perform in different conditions of an experiment.

Counterbalancing

Suppose we used a repeated measures design in which all of the participants first learned words in “loud noise” and then learned them in “no noise.”

We expect the participants to learn better in “no noise” because of order effects, such as practice. However, a researcher can control for order effects using counterbalancing.

The sample would be split into two groups: experimental (A) and control (B). For example, group 1 does ‘A’ then ‘B,’ and group 2 does ‘B’ then ‘A.’ This is to eliminate order effects.

Although order effects occur for each participant, they balance each other out in the results because they occur equally in both groups.

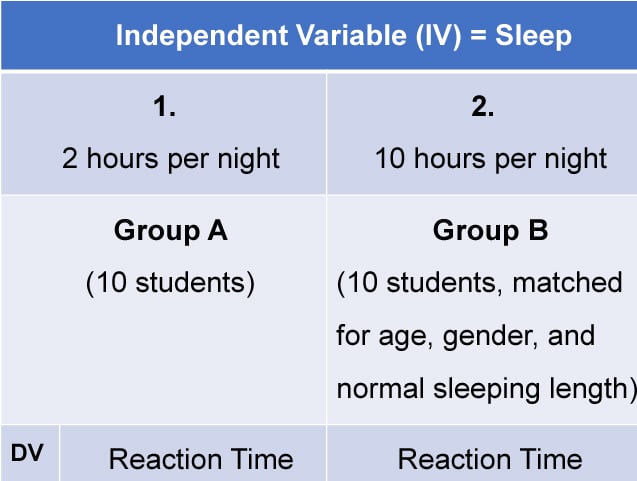

3. Matched Pairs Design

A matched pairs design is an experimental design where pairs of participants are matched in terms of key variables, such as age or socioeconomic status. One member of each pair is then placed into the experimental group and the other member into the control group .

One member of each matched pair must be randomly assigned to the experimental group and the other to the control group.

- Con : If one participant drops out, you lose 2 PPs’ data.

- Pro : Reduces participant variables because the researcher has tried to pair up the participants so that each condition has people with similar abilities and characteristics.

- Con : Very time-consuming trying to find closely matched pairs.

- Pro : It avoids order effects, so counterbalancing is not necessary.

- Con : Impossible to match people exactly unless they are identical twins!

- Control : Members of each pair should be randomly assigned to conditions. However, this does not solve all these problems.

Experimental design refers to how participants are allocated to an experiment’s different conditions (or IV levels). There are three types:

1. Independent measures / between-groups : Different participants are used in each condition of the independent variable.

2. Repeated measures /within groups : The same participants take part in each condition of the independent variable.

3. Matched pairs : Each condition uses different participants, but they are matched in terms of important characteristics, e.g., gender, age, intelligence, etc.

Learning Check

Read about each of the experiments below. For each experiment, identify (1) which experimental design was used; and (2) why the researcher might have used that design.

1 . To compare the effectiveness of two different types of therapy for depression, depressed patients were assigned to receive either cognitive therapy or behavior therapy for a 12-week period.

The researchers attempted to ensure that the patients in the two groups had similar severity of depressed symptoms by administering a standardized test of depression to each participant, then pairing them according to the severity of their symptoms.

2 . To assess the difference in reading comprehension between 7 and 9-year-olds, a researcher recruited each group from a local primary school. They were given the same passage of text to read and then asked a series of questions to assess their understanding.

3 . To assess the effectiveness of two different ways of teaching reading, a group of 5-year-olds was recruited from a primary school. Their level of reading ability was assessed, and then they were taught using scheme one for 20 weeks.

At the end of this period, their reading was reassessed, and a reading improvement score was calculated. They were then taught using scheme two for a further 20 weeks, and another reading improvement score for this period was calculated. The reading improvement scores for each child were then compared.

4 . To assess the effect of the organization on recall, a researcher randomly assigned student volunteers to two conditions.

Condition one attempted to recall a list of words that were organized into meaningful categories; condition two attempted to recall the same words, randomly grouped on the page.

Experiment Terminology

Ecological validity.

The degree to which an investigation represents real-life experiences.

Experimenter effects

These are the ways that the experimenter can accidentally influence the participant through their appearance or behavior.

Demand characteristics

The clues in an experiment lead the participants to think they know what the researcher is looking for (e.g., the experimenter’s body language).

Independent variable (IV)

The variable the experimenter manipulates (i.e., changes) is assumed to have a direct effect on the dependent variable.

Dependent variable (DV)

Variable the experimenter measures. This is the outcome (i.e., the result) of a study.

Extraneous variables (EV)

All variables which are not independent variables but could affect the results (DV) of the experiment. Extraneous variables should be controlled where possible.

Confounding variables

Variable(s) that have affected the results (DV), apart from the IV. A confounding variable could be an extraneous variable that has not been controlled.

Random Allocation

Randomly allocating participants to independent variable conditions means that all participants should have an equal chance of taking part in each condition.

The principle of random allocation is to avoid bias in how the experiment is carried out and limit the effects of participant variables.

Order effects

Changes in participants’ performance due to their repeating the same or similar test more than once. Examples of order effects include:

(i) practice effect: an improvement in performance on a task due to repetition, for example, because of familiarity with the task;

(ii) fatigue effect: a decrease in performance of a task due to repetition, for example, because of boredom or tiredness.

Related Articles

Research Methodology

Qualitative Data Coding

What Is a Focus Group?

Cross-Cultural Research Methodology In Psychology

What Is Internal Validity In Research?

Research Methodology , Statistics

What Is Face Validity In Research? Importance & How To Measure

Criterion Validity: Definition & Examples

- Experimental Research Designs: Types, Examples & Methods

Experimental research is the most familiar type of research design for individuals in the physical sciences and a host of other fields. This is mainly because experimental research is a classical scientific experiment, similar to those performed in high school science classes.

Imagine taking 2 samples of the same plant and exposing one of them to sunlight, while the other is kept away from sunlight. Let the plant exposed to sunlight be called sample A, while the latter is called sample B.

If after the duration of the research, we find out that sample A grows and sample B dies, even though they are both regularly wetted and given the same treatment. Therefore, we can conclude that sunlight will aid growth in all similar plants.

What is Experimental Research?

Experimental research is a scientific approach to research, where one or more independent variables are manipulated and applied to one or more dependent variables to measure their effect on the latter. The effect of the independent variables on the dependent variables is usually observed and recorded over some time, to aid researchers in drawing a reasonable conclusion regarding the relationship between these 2 variable types.

The experimental research method is widely used in physical and social sciences, psychology, and education. It is based on the comparison between two or more groups with a straightforward logic, which may, however, be difficult to execute.

Mostly related to a laboratory test procedure, experimental research designs involve collecting quantitative data and performing statistical analysis on them during research. Therefore, making it an example of quantitative research method .

What are The Types of Experimental Research Design?

The types of experimental research design are determined by the way the researcher assigns subjects to different conditions and groups. They are of 3 types, namely; pre-experimental, quasi-experimental, and true experimental research.

Pre-experimental Research Design

In pre-experimental research design, either a group or various dependent groups are observed for the effect of the application of an independent variable which is presumed to cause change. It is the simplest form of experimental research design and is treated with no control group.

Although very practical, experimental research is lacking in several areas of the true-experimental criteria. The pre-experimental research design is further divided into three types

- One-shot Case Study Research Design

In this type of experimental study, only one dependent group or variable is considered. The study is carried out after some treatment which was presumed to cause change, making it a posttest study.

- One-group Pretest-posttest Research Design:

This research design combines both posttest and pretest study by carrying out a test on a single group before the treatment is administered and after the treatment is administered. With the former being administered at the beginning of treatment and later at the end.

- Static-group Comparison:

In a static-group comparison study, 2 or more groups are placed under observation, where only one of the groups is subjected to some treatment while the other groups are held static. All the groups are post-tested, and the observed differences between the groups are assumed to be a result of the treatment.

Quasi-experimental Research Design

The word “quasi” means partial, half, or pseudo. Therefore, the quasi-experimental research bearing a resemblance to the true experimental research, but not the same. In quasi-experiments, the participants are not randomly assigned, and as such, they are used in settings where randomization is difficult or impossible.

This is very common in educational research, where administrators are unwilling to allow the random selection of students for experimental samples.

Some examples of quasi-experimental research design include; the time series, no equivalent control group design, and the counterbalanced design.

True Experimental Research Design

The true experimental research design relies on statistical analysis to approve or disprove a hypothesis. It is the most accurate type of experimental design and may be carried out with or without a pretest on at least 2 randomly assigned dependent subjects.

The true experimental research design must contain a control group, a variable that can be manipulated by the researcher, and the distribution must be random. The classification of true experimental design include:

- The posttest-only Control Group Design: In this design, subjects are randomly selected and assigned to the 2 groups (control and experimental), and only the experimental group is treated. After close observation, both groups are post-tested, and a conclusion is drawn from the difference between these groups.

- The pretest-posttest Control Group Design: For this control group design, subjects are randomly assigned to the 2 groups, both are presented, but only the experimental group is treated. After close observation, both groups are post-tested to measure the degree of change in each group.

- Solomon four-group Design: This is the combination of the pretest-only and the pretest-posttest control groups. In this case, the randomly selected subjects are placed into 4 groups.

The first two of these groups are tested using the posttest-only method, while the other two are tested using the pretest-posttest method.

Examples of Experimental Research

Experimental research examples are different, depending on the type of experimental research design that is being considered. The most basic example of experimental research is laboratory experiments, which may differ in nature depending on the subject of research.

Administering Exams After The End of Semester

During the semester, students in a class are lectured on particular courses and an exam is administered at the end of the semester. In this case, the students are the subjects or dependent variables while the lectures are the independent variables treated on the subjects.

Only one group of carefully selected subjects are considered in this research, making it a pre-experimental research design example. We will also notice that tests are only carried out at the end of the semester, and not at the beginning.

Further making it easy for us to conclude that it is a one-shot case study research.

Employee Skill Evaluation

Before employing a job seeker, organizations conduct tests that are used to screen out less qualified candidates from the pool of qualified applicants. This way, organizations can determine an employee’s skill set at the point of employment.

In the course of employment, organizations also carry out employee training to improve employee productivity and generally grow the organization. Further evaluation is carried out at the end of each training to test the impact of the training on employee skills, and test for improvement.

Here, the subject is the employee, while the treatment is the training conducted. This is a pretest-posttest control group experimental research example.

Evaluation of Teaching Method

Let us consider an academic institution that wants to evaluate the teaching method of 2 teachers to determine which is best. Imagine a case whereby the students assigned to each teacher is carefully selected probably due to personal request by parents or due to stubbornness and smartness.

This is a no equivalent group design example because the samples are not equal. By evaluating the effectiveness of each teacher’s teaching method this way, we may conclude after a post-test has been carried out.

However, this may be influenced by factors like the natural sweetness of a student. For example, a very smart student will grab more easily than his or her peers irrespective of the method of teaching.

What are the Characteristics of Experimental Research?

Experimental research contains dependent, independent and extraneous variables. The dependent variables are the variables being treated or manipulated and are sometimes called the subject of the research.

The independent variables are the experimental treatment being exerted on the dependent variables. Extraneous variables, on the other hand, are other factors affecting the experiment that may also contribute to the change.

The setting is where the experiment is carried out. Many experiments are carried out in the laboratory, where control can be exerted on the extraneous variables, thereby eliminating them.

Other experiments are carried out in a less controllable setting. The choice of setting used in research depends on the nature of the experiment being carried out.

- Multivariable

Experimental research may include multiple independent variables, e.g. time, skills, test scores, etc.

Why Use Experimental Research Design?

Experimental research design can be majorly used in physical sciences, social sciences, education, and psychology. It is used to make predictions and draw conclusions on a subject matter.

Some uses of experimental research design are highlighted below.

- Medicine: Experimental research is used to provide the proper treatment for diseases. In most cases, rather than directly using patients as the research subject, researchers take a sample of the bacteria from the patient’s body and are treated with the developed antibacterial

The changes observed during this period are recorded and evaluated to determine its effectiveness. This process can be carried out using different experimental research methods.

- Education: Asides from science subjects like Chemistry and Physics which involves teaching students how to perform experimental research, it can also be used in improving the standard of an academic institution. This includes testing students’ knowledge on different topics, coming up with better teaching methods, and the implementation of other programs that will aid student learning.

- Human Behavior: Social scientists are the ones who mostly use experimental research to test human behaviour. For example, consider 2 people randomly chosen to be the subject of the social interaction research where one person is placed in a room without human interaction for 1 year.

The other person is placed in a room with a few other people, enjoying human interaction. There will be a difference in their behaviour at the end of the experiment.

- UI/UX: During the product development phase, one of the major aims of the product team is to create a great user experience with the product. Therefore, before launching the final product design, potential are brought in to interact with the product.

For example, when finding it difficult to choose how to position a button or feature on the app interface, a random sample of product testers are allowed to test the 2 samples and how the button positioning influences the user interaction is recorded.

What are the Disadvantages of Experimental Research?

- It is highly prone to human error due to its dependency on variable control which may not be properly implemented. These errors could eliminate the validity of the experiment and the research being conducted.

- Exerting control of extraneous variables may create unrealistic situations. Eliminating real-life variables will result in inaccurate conclusions. This may also result in researchers controlling the variables to suit his or her personal preferences.

- It is a time-consuming process. So much time is spent on testing dependent variables and waiting for the effect of the manipulation of dependent variables to manifest.

- It is expensive.

- It is very risky and may have ethical complications that cannot be ignored. This is common in medical research, where failed trials may lead to a patient’s death or a deteriorating health condition.

- Experimental research results are not descriptive.

- Response bias can also be supplied by the subject of the conversation.

- Human responses in experimental research can be difficult to measure.

What are the Data Collection Methods in Experimental Research?

Data collection methods in experimental research are the different ways in which data can be collected for experimental research. They are used in different cases, depending on the type of research being carried out.

1. Observational Study

This type of study is carried out over a long period. It measures and observes the variables of interest without changing existing conditions.

When researching the effect of social interaction on human behavior, the subjects who are placed in 2 different environments are observed throughout the research. No matter the kind of absurd behavior that is exhibited by the subject during this period, its condition will not be changed.

This may be a very risky thing to do in medical cases because it may lead to death or worse medical conditions.

2. Simulations

This procedure uses mathematical, physical, or computer models to replicate a real-life process or situation. It is frequently used when the actual situation is too expensive, dangerous, or impractical to replicate in real life.

This method is commonly used in engineering and operational research for learning purposes and sometimes as a tool to estimate possible outcomes of real research. Some common situation software are Simulink, MATLAB, and Simul8.

Not all kinds of experimental research can be carried out using simulation as a data collection tool . It is very impractical for a lot of laboratory-based research that involves chemical processes.

A survey is a tool used to gather relevant data about the characteristics of a population and is one of the most common data collection tools. A survey consists of a group of questions prepared by the researcher, to be answered by the research subject.

Surveys can be shared with the respondents both physically and electronically. When collecting data through surveys, the kind of data collected depends on the respondent, and researchers have limited control over it.

Formplus is the best tool for collecting experimental data using survey s. It has relevant features that will aid the data collection process and can also be used in other aspects of experimental research.

Differences between Experimental and Non-Experimental Research

1. In experimental research, the researcher can control and manipulate the environment of the research, including the predictor variable which can be changed. On the other hand, non-experimental research cannot be controlled or manipulated by the researcher at will.

This is because it takes place in a real-life setting, where extraneous variables cannot be eliminated. Therefore, it is more difficult to conclude non-experimental studies, even though they are much more flexible and allow for a greater range of study fields.

2. The relationship between cause and effect cannot be established in non-experimental research, while it can be established in experimental research. This may be because many extraneous variables also influence the changes in the research subject, making it difficult to point at a particular variable as the cause of a particular change

3. Independent variables are not introduced, withdrawn, or manipulated in non-experimental designs, but the same may not be said about experimental research.

Conclusion

Experimental research designs are often considered to be the standard in research designs. This is partly due to the common misconception that research is equivalent to scientific experiments—a component of experimental research design.

In this research design, one or more subjects or dependent variables are randomly assigned to different treatments (i.e. independent variables manipulated by the researcher) and the results are observed to conclude. One of the uniqueness of experimental research is in its ability to control the effect of extraneous variables.

Experimental research is suitable for research whose goal is to examine cause-effect relationships, e.g. explanatory research. It can be conducted in the laboratory or field settings, depending on the aim of the research that is being carried out.

Connect to Formplus, Get Started Now - It's Free!

- examples of experimental research

- experimental research methods

- types of experimental research

- busayo.longe

You may also like:

Response vs Explanatory Variables: Definition & Examples

In this article, we’ll be comparing the two types of variables, what they both mean and see some of their real-life applications in research

What is Experimenter Bias? Definition, Types & Mitigation

In this article, we will look into the concept of experimental bias and how it can be identified in your research

Simpson’s Paradox & How to Avoid it in Experimental Research

In this article, we are going to look at Simpson’s Paradox from its historical point and later, we’ll consider its effect in...

Experimental Vs Non-Experimental Research: 15 Key Differences

Differences between experimental and non experimental research on definitions, types, examples, data collection tools, uses, advantages etc.

Formplus - For Seamless Data Collection

Collect data the right way with a versatile data collection tool. try formplus and transform your work productivity today..

Experimental Research Design

- First Online: 10 November 2021

Cite this chapter

- Stefan Hunziker 3 &

- Michael Blankenagel 3

1 Citations

This chapter addresses the peculiarities, characteristics, and major fallacies of experimental research designs. Experiments have a long and important history in the social, natural, and medicinal sciences. Unfortunately, in business and management this looks differently. This is astounding, as experiments are suitable for analyzing cause-and-effect relationships. A true experiment is a brilliant method for finding out if one element really causes other elements. Also, researchers find relevant information on how to write an experimental research design paper and learn about typical methodologies used for this research design. The chapter closes with referring to overlapping and adjacent research designs.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Aronson, E., Ellsworth, P., Carlsmith, J., & Gonzales, M. (1990). Methods of research in social psychology (2nd ed.). McGraw-Hill.

Google Scholar

Bargh, J., Chen, M., & Burrows, L. (1996). Automaticity of social behavior: Direct effects of trait construct and stereotype activation on action. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology., 71 (2), 230–244.

Article Google Scholar

Biais, B., & Weber, M. (2009). Hindsight bias, risk perception, and investment performance. Management Science, 55 (6), 1018–1029.

Bortz, J. & Döring, N. (2006). Forschungsmethoden und evaluation . Springer.

Bowlin, K. O., Hales, J., & Kachelmeier, S. J. (2009). Experimental evidence of how prior experience as an auditor influences managers’ strategic reporting decisions. Rev Account Stud, 14 (1), 63–87.

Burmeister, K., & Schade, C. (2007). Are entrepreneurs’ decisions more biased? An experimental investigation of the susceptibility to status quo bias. Journal of Business Venturing, 22 (3), 340–362.

Christensen, L. B. (2007). Experimental methodology . Pearson/Allyn and Bacon.

de Vaus, D. A. (2001). Research design in social research . Reprinted. Los Angeles: SAGE Publications, Inc.

Doyle, A. C. (1890). The sign of the four. Lippincott’s Monthly Magazine . Ward, Lock & Co.

Franke, N., Schreier, M., & Kaiser, U. (2010). The “I designed it myself” effect in mass customization. Management Science, 56 (1), 125–140.

Friese, M., Wilhelm, H., & Michaela, W. (2009). The impulsive consumer: Predicting consumer behavior with implicit reaction time measurements. Social Psychology of Consumer Behavior (pp. 335–364). Psychology Press.

Fromkin, H. L., & Streufert, S. (1976). Laboratory experimentation. In M. D. Dunnette (Ed.), Handbook of industrial and organizational psychology (pp. 415–465). Rand McNally College.

Harbring, C., & Irlenbusch, B. (2011). Sabotage in tournaments: evidence from a laboratory experiment. Management Science, 57 (4), 611–627.

Hennig-Thurau, T., Groth, M., Paul, M., & Gremler, D. D. (2006). Are all smiles created equal? How emotional contagion and emotional labor affect service relationships. Journal of Marketing, 70 (3), 58–73.

Homburg, C., Koschate, N., & Hoyer, W. D. (2005). Do Satisfied customers really pay more? A study of the relationship between customer satisfaction and willingness to pay. Journal of Marketing, 69 (2), 84–96.

Johnson, B. (2001). Toward a new classification of nonexperimental quantitative research. Educational Researcher, 30 (2), 3–13.

Koschate-Fischer, N., & Schandelmeier, S. (2014). A Guideline for Designing Experimental Studies in Marketing research and a Critical Discussion of Selected Problem Areas. Journal of Business Economics, 84 (6), 793–826.

Krishnaswamy K. N., Sivakumar A. I. & Mathirajan M. (2009). Management research methodology: Integration of principles, methods and techniques . Dorling Kindersley.

Lödding, H., & Lohmann, S. (2012). INCAP – applying short-term flexibility to control inventories. International Journal of Production Research, 50 (3), 909–919.

Mohnen, A., Pokorny, K., & Sliwka, D. (2008). Transparency, inequity aversion, and the dynamics of peer pressure in teams: Theory and evidence. Journal of Labor Economics, 26 (4), 693–720.

Perdue, B. C., & Summers, J. O. (1986). Checking the success of manipulations in marketing experiments. Journal of Marketing Research, 23 (4), 317–326.

Robson, C. (2011). Real world research: A resource for users of social research methods in applied settings (3rd ed.). Wiley.

Rogers, W. S. (2003). Social psychology: Experimental and critical approaches . Open University Press.

Sandri, S., Schade, C., Mußhoff, O., & Odening, M. (2010). Holding on for too long? An experimental study on inertia in entrepreneurs’ and non-entrepreneurs’ disinvestment choices. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 76 (1), 30–44.

Schoen, K., & Crilly, N. (2012). Implicit methods for testing product preference: Exploratory studies with the affective simon task. In J. Brasset, J. McDonnell, & M. Malpass (Eds.), Proceedings of 8th international design and emotion conference, ed. London: Central Saint Martins College of Art and Design.

Stier, W. (1999). Empirische Forschungsmethoden . Springer.

Trochim, W. (2005). Research methods: The concise knowledge base. Atomic Dog Pub.

Weber, M., & Zuchel, H. (2005). How do prior outcomes affect risk attitude? Comparing escalation of commitment and the house-money effect. Decision Analysis, 2 (1), 30–43.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Wirtschaft/IFZ – Campus Zug-Rotkreuz, Hochschule Luzern, Zug-Rotkreuz, Zug , Switzerland

Stefan Hunziker & Michael Blankenagel

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Stefan Hunziker .

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2021 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden GmbH, part of Springer Nature

About this chapter

Hunziker, S., Blankenagel, M. (2021). Experimental Research Design. In: Research Design in Business and Management. Springer Gabler, Wiesbaden. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-34357-6_12

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-34357-6_12

Published : 10 November 2021

Publisher Name : Springer Gabler, Wiesbaden

Print ISBN : 978-3-658-34356-9

Online ISBN : 978-3-658-34357-6

eBook Packages : Business and Economics (German Language)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

- QuestionPro

- Solutions Industries Gaming Automotive Sports and events Education Government Travel & Hospitality Financial Services Healthcare Cannabis Technology Use Case NPS+ Communities Audience Contactless surveys Mobile LivePolls Member Experience GDPR Positive People Science 360 Feedback Surveys

- Resources Blog eBooks Survey Templates Case Studies Training Help center

Home Market Research

Experimental Research: What it is + Types of designs

Any research conducted under scientifically acceptable conditions uses experimental methods. The success of experimental studies hinges on researchers confirming the change of a variable is based solely on the manipulation of the constant variable. The research should establish a notable cause and effect.

What is Experimental Research?

Experimental research is a study conducted with a scientific approach using two sets of variables. The first set acts as a constant, which you use to measure the differences of the second set. Quantitative research methods , for example, are experimental.

If you don’t have enough data to support your decisions, you must first determine the facts. This research gathers the data necessary to help you make better decisions.

You can conduct experimental research in the following situations:

- Time is a vital factor in establishing a relationship between cause and effect.

- Invariable behavior between cause and effect.

- You wish to understand the importance of cause and effect.

Experimental Research Design Types

The classic experimental design definition is: “The methods used to collect data in experimental studies.”

There are three primary types of experimental design:

- Pre-experimental research design

- True experimental research design

- Quasi-experimental research design

The way you classify research subjects based on conditions or groups determines the type of research design you should use.

0 1. Pre-Experimental Design

A group, or various groups, are kept under observation after implementing cause and effect factors. You’ll conduct this research to understand whether further investigation is necessary for these particular groups.

You can break down pre-experimental research further into three types:

- One-shot Case Study Research Design

- One-group Pretest-posttest Research Design

- Static-group Comparison

0 2. True Experimental Design

It relies on statistical analysis to prove or disprove a hypothesis, making it the most accurate form of research. Of the types of experimental design, only true design can establish a cause-effect relationship within a group. In a true experiment, three factors need to be satisfied:

- There is a Control Group, which won’t be subject to changes, and an Experimental Group, which will experience the changed variables.

- A variable that can be manipulated by the researcher

- Random distribution

This experimental research method commonly occurs in the physical sciences.

0 3. Quasi-Experimental Design

The word “Quasi” indicates similarity. A quasi-experimental design is similar to an experimental one, but it is not the same. The difference between the two is the assignment of a control group. In this research, an independent variable is manipulated, but the participants of a group are not randomly assigned. Quasi-research is used in field settings where random assignment is either irrelevant or not required.

Importance of Experimental Design

Experimental research is a powerful tool for understanding cause-and-effect relationships. It allows us to manipulate variables and observe the effects, which is crucial for understanding how different factors influence the outcome of a study.

But the importance of experimental research goes beyond that. It’s a critical method for many scientific and academic studies. It allows us to test theories, develop new products, and make groundbreaking discoveries.

For example, this research is essential for developing new drugs and medical treatments. Researchers can understand how a new drug works by manipulating dosage and administration variables and identifying potential side effects.

Similarly, experimental research is used in the field of psychology to test theories and understand human behavior. By manipulating variables such as stimuli, researchers can gain insights into how the brain works and identify new treatment options for mental health disorders.

It is also widely used in the field of education. It allows educators to test new teaching methods and identify what works best. By manipulating variables such as class size, teaching style, and curriculum, researchers can understand how students learn and identify new ways to improve educational outcomes.

In addition, experimental research is a powerful tool for businesses and organizations. By manipulating variables such as marketing strategies, product design, and customer service, companies can understand what works best and identify new opportunities for growth.

Advantages of Experimental Research

When talking about this research, we can think of human life. Babies do their own rudimentary experiments (such as putting objects in their mouths) to learn about the world around them, while older children and teens do experiments at school to learn more about science.

Ancient scientists used this research to prove that their hypotheses were correct. For example, Galileo Galilei and Antoine Lavoisier conducted various experiments to discover key concepts in physics and chemistry. The same is true of modern experts, who use this scientific method to see if new drugs are effective, discover treatments for diseases, and create new electronic devices (among others).

It’s vital to test new ideas or theories. Why put time, effort, and funding into something that may not work?

This research allows you to test your idea in a controlled environment before marketing. It also provides the best method to test your theory thanks to the following advantages:

- Researchers have a stronger hold over variables to obtain desired results.

- The subject or industry does not impact the effectiveness of experimental research. Any industry can implement it for research purposes.

- The results are specific.

- After analyzing the results, you can apply your findings to similar ideas or situations.

- You can identify the cause and effect of a hypothesis. Researchers can further analyze this relationship to determine more in-depth ideas.

- Experimental research makes an ideal starting point. The data you collect is a foundation for building more ideas and conducting more action research .

Whether you want to know how the public will react to a new product or if a certain food increases the chance of disease, experimental research is the best place to start. Begin your research by finding subjects using QuestionPro Audience and other tools today.

LEARN MORE FREE TRIAL

MORE LIKE THIS

Top 10 Dynata Alternatives & Competitors

May 27, 2024

What Are My Employees Really Thinking? The Power of Open-ended Survey Analysis

May 24, 2024

I Am Disconnected – Tuesday CX Thoughts

May 21, 2024

20 Best Customer Success Tools of 2024

May 20, 2024

Other categories

- Academic Research

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assessments

- Brand Awareness

- Case Studies

- Communities

- Consumer Insights

- Customer effort score

- Customer Engagement

- Customer Experience

- Customer Loyalty

- Customer Research

- Customer Satisfaction

- Employee Benefits

- Employee Engagement

- Employee Retention

- Friday Five

- General Data Protection Regulation

- Insights Hub

- Life@QuestionPro

- Market Research

- Mobile diaries

- Mobile Surveys

- New Features

- Online Communities

- Question Types

- Questionnaire

- QuestionPro Products

- Release Notes

- Research Tools and Apps

- Revenue at Risk

- Survey Templates

- Training Tips

- Uncategorized

- Video Learning Series

- What’s Coming Up

- Workforce Intelligence

19+ Experimental Design Examples (Methods + Types)

Ever wondered how scientists discover new medicines, psychologists learn about behavior, or even how marketers figure out what kind of ads you like? Well, they all have something in common: they use a special plan or recipe called an "experimental design."

Imagine you're baking cookies. You can't just throw random amounts of flour, sugar, and chocolate chips into a bowl and hope for the best. You follow a recipe, right? Scientists and researchers do something similar. They follow a "recipe" called an experimental design to make sure their experiments are set up in a way that the answers they find are meaningful and reliable.

Experimental design is the roadmap researchers use to answer questions. It's a set of rules and steps that researchers follow to collect information, or "data," in a way that is fair, accurate, and makes sense.

Long ago, people didn't have detailed game plans for experiments. They often just tried things out and saw what happened. But over time, people got smarter about this. They started creating structured plans—what we now call experimental designs—to get clearer, more trustworthy answers to their questions.

In this article, we'll take you on a journey through the world of experimental designs. We'll talk about the different types, or "flavors," of experimental designs, where they're used, and even give you a peek into how they came to be.

What Is Experimental Design?

Alright, before we dive into the different types of experimental designs, let's get crystal clear on what experimental design actually is.

Imagine you're a detective trying to solve a mystery. You need clues, right? Well, in the world of research, experimental design is like the roadmap that helps you find those clues. It's like the game plan in sports or the blueprint when you're building a house. Just like you wouldn't start building without a good blueprint, researchers won't start their studies without a strong experimental design.

So, why do we need experimental design? Think about baking a cake. If you toss ingredients into a bowl without measuring, you'll end up with a mess instead of a tasty dessert.

Similarly, in research, if you don't have a solid plan, you might get confusing or incorrect results. A good experimental design helps you ask the right questions ( think critically ), decide what to measure ( come up with an idea ), and figure out how to measure it (test it). It also helps you consider things that might mess up your results, like outside influences you hadn't thought of.

For example, let's say you want to find out if listening to music helps people focus better. Your experimental design would help you decide things like: Who are you going to test? What kind of music will you use? How will you measure focus? And, importantly, how will you make sure that it's really the music affecting focus and not something else, like the time of day or whether someone had a good breakfast?

In short, experimental design is the master plan that guides researchers through the process of collecting data, so they can answer questions in the most reliable way possible. It's like the GPS for the journey of discovery!

History of Experimental Design

Around 350 BCE, people like Aristotle were trying to figure out how the world works, but they mostly just thought really hard about things. They didn't test their ideas much. So while they were super smart, their methods weren't always the best for finding out the truth.

Fast forward to the Renaissance (14th to 17th centuries), a time of big changes and lots of curiosity. People like Galileo started to experiment by actually doing tests, like rolling balls down inclined planes to study motion. Galileo's work was cool because he combined thinking with doing. He'd have an idea, test it, look at the results, and then think some more. This approach was a lot more reliable than just sitting around and thinking.

Now, let's zoom ahead to the 18th and 19th centuries. This is when people like Francis Galton, an English polymath, started to get really systematic about experimentation. Galton was obsessed with measuring things. Seriously, he even tried to measure how good-looking people were ! His work helped create the foundations for a more organized approach to experiments.

Next stop: the early 20th century. Enter Ronald A. Fisher , a brilliant British statistician. Fisher was a game-changer. He came up with ideas that are like the bread and butter of modern experimental design.

Fisher invented the concept of the " control group "—that's a group of people or things that don't get the treatment you're testing, so you can compare them to those who do. He also stressed the importance of " randomization ," which means assigning people or things to different groups by chance, like drawing names out of a hat. This makes sure the experiment is fair and the results are trustworthy.

Around the same time, American psychologists like John B. Watson and B.F. Skinner were developing " behaviorism ." They focused on studying things that they could directly observe and measure, like actions and reactions.

Skinner even built boxes—called Skinner Boxes —to test how animals like pigeons and rats learn. Their work helped shape how psychologists design experiments today. Watson performed a very controversial experiment called The Little Albert experiment that helped describe behaviour through conditioning—in other words, how people learn to behave the way they do.

In the later part of the 20th century and into our time, computers have totally shaken things up. Researchers now use super powerful software to help design their experiments and crunch the numbers.

With computers, they can simulate complex experiments before they even start, which helps them predict what might happen. This is especially helpful in fields like medicine, where getting things right can be a matter of life and death.

Also, did you know that experimental designs aren't just for scientists in labs? They're used by people in all sorts of jobs, like marketing, education, and even video game design! Yes, someone probably ran an experiment to figure out what makes a game super fun to play.

So there you have it—a quick tour through the history of experimental design, from Aristotle's deep thoughts to Fisher's groundbreaking ideas, and all the way to today's computer-powered research. These designs are the recipes that help people from all walks of life find answers to their big questions.

Key Terms in Experimental Design

Before we dig into the different types of experimental designs, let's get comfy with some key terms. Understanding these terms will make it easier for us to explore the various types of experimental designs that researchers use to answer their big questions.

Independent Variable : This is what you change or control in your experiment to see what effect it has. Think of it as the "cause" in a cause-and-effect relationship. For example, if you're studying whether different types of music help people focus, the kind of music is the independent variable.