Transatlantic Slave Trade Essay

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

The infamous Transatlantic Slave Trade “took place from the 15 th to the 19 th century” (Bush 19). This trade resulted in massive human migration. Many Africans came to America during the period. According to historians, many Europeans wanted to support their colonies in order to achieve their goals. During the period, many “colonies were producing various cash crops such as cotton, sugar, and tobacco” (Bush 27).

Most of the paid laborers were becoming extremely expensive. The indigenous populations were also dying due to poverty, conflicts, and diseases. The colonialists wanted to get new sources of cheap labor. The best solution to this problem was to acquire different slaves from Africa. Some African societies collaborated with different Europeans in order support this illegal trade. Some merchants also wanted to benefit from the Slave Trade. This fact explains why different African leaders and merchants supported the trade.

The Slave Trade also affected many societies across the world. For example, the trade supported the economic needs of different colonies. The practice also supported the economic positions of different countries. A large number of individuals lost their original lands. According to many scholars, the trade introduced new diseases and socio-cultural practices in these colonies. The trade also resulted in environmental destruction.

The Slave Trade “left many societies underdeveloped and disorganized” (Bush 62). This development also weakened several communities in Africa and Asia. The Slave Trade affected the economic stability of every targeted society. This situation made such societies more vulnerable to colonialism. This slave trade produced different racial groups in many countries across the globe. The trade also produced long-term effects such as poverty, inequality, and discrimination. Many descendants of these slaves are currently facing most of these challenges. The Slave Trade presented numerous lessons to different societies. Many societies enacted new laws in order to safeguard the rights of every minority group.

Imperialism

The word imperialism “refers to a policy aimed at expanding a nation’s influence and capability through military force, colonization, or assimilation” (Thomas 38). Many countries such as the United States “pursued aggressive policies in an attempt to extend their economic and political influences across the word” (Thomas 47). Some historians have presented numerous arguments regarding the major causes of imperialism.

For example, many nations wanted to acquire new territories in order to emerge powerful. This expectation encouraged some countries such as Britain, France, and Italy to colonize different societies. The second factor that contributed to imperialism was “the desire to govern and develop different societies” (Thomas 49). Some countries also used the policy to acquire different uninhabited lands. This argument explains why different countries wanted to support their economies.

Imperialism transformed the economic strengths of different countries. Colonialism was one of the strategies aimed at promoting this policy. The approach resulted in new ideas such as globalization. The development supported the economic positions of different nations. This situation also made it easier for many nations to achieve the best goals. A “multi-polar world also developed because of imperialism” (Thomas 84). This development also produced different empires. The evolution of these empires reshaped the economic policies and political systems of many countries. Many governments and societies have borrowed their leadership ideas from the wave of imperialism. Historians and scholars have gained numerous political and economic ideas from the wave of imperialism.

Works Cited

Bush, Barbara. Imperialism and Post-colonialism History: Concepts, Theories and Practice . New York, Longmans, 2006. Print.

Thomas, Hugh. The Slave Trade: The History of the Atlantic Slave Trade, 1440-1870. New York: Oxford University Press, 2006. Print.

- The Middle Passage, a Part of the Transatlantic Voyage

- Colonialism and the End of Internal Slavery

- Silver Jet and Transatlantic Airline Market

- African American History After Reconstruction

- The African Burial Ground in the New York Area

- Slavery and the Southern Society's Development

- Pre-Civil War Antislavery Movement and Debates

- Tribal Water Rights and Influence on the State Future

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2021, March 3). Transatlantic Slave Trade. https://ivypanda.com/essays/transatlantic-slave-trade/

"Transatlantic Slave Trade." IvyPanda , 3 Mar. 2021, ivypanda.com/essays/transatlantic-slave-trade/.

IvyPanda . (2021) 'Transatlantic Slave Trade'. 3 March.

IvyPanda . 2021. "Transatlantic Slave Trade." March 3, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/transatlantic-slave-trade/.

1. IvyPanda . "Transatlantic Slave Trade." March 3, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/transatlantic-slave-trade/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Transatlantic Slave Trade." March 3, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/transatlantic-slave-trade/.

Visiting Sleeping Beauties: Reawakening Fashion?

You must join the virtual exhibition queue when you arrive. If capacity has been reached for the day, the queue will close early.

Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History Essays

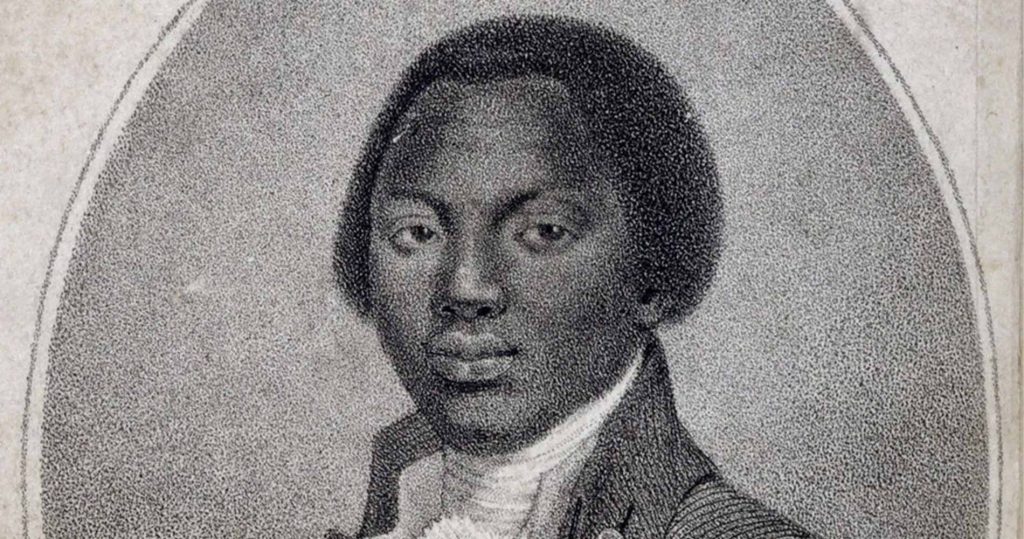

The transatlantic slave trade.

Necklace: Pendant

Figure: Seated Portuguese Male

Pipe: Rifle

Alexander Ives Bortolot Department of Art History and Archaeology, Columbia University

October 2003

From the seventeenth century on, slaves became the focus of trade between Europe and Africa. Europe’s conquest and colonization of North and South America and the Caribbean islands from the fifteenth century onward created an insatiable demand for African laborers, who were deemed more fit to work in the tropical conditions of the New World. The numbers of slaves imported across the Atlantic Ocean steadily increased, from approximately 5,000 slaves a year in the sixteenth century to over 100,000 slaves a year by the end of the eighteenth century.

Evolving political circumstances and trade alliances in Africa led to shifts in the geographic origins of slaves throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Slaves were generally the unfortunate victims of territorial expansion by imperialist African states or of raids led by predatory local strongmen, and various populations found themselves captured and sold as different regional powers came to prominence. Firearms, which were often exchanged for slaves, generally increased the level of fighting by lending military strength to previously marginal polities. A nineteenth-century tobacco pipe ( 1977.462.1 ) from the Democratic Republic of the Congo or Angola demonstrates the degree to which warfare, the slave trade, and elite arts were intertwined at this time. The pipe itself was the prerogative of wealthy and powerful individuals who could afford expensive imported tobacco, generally by trading slaves, while the rifle form makes clear how such slaves were acquired in the first place. Because of its deadly power, the rifle was added to the repertory of motifs drawn upon in many regional depictions of rulers and culture heroes as emblematic of power along with the leopard, elephant, and python.

The institution of slavery existed in Africa long before the arrival of Europeans and was widespread at the period of economic contact . Private land ownership was largely absent from precolonial African societies, and slaves were one of the few forms of wealth-producing property an individual could possess. Additionally, rulers often maintained corps of loyal, foreign-born slaves to guarantee their political security, and would encourage political centralization by appointing slaves from the imperial hinterlands to positions within the royal capital. Slaves were also exported across the desert to North Africa and to western Asia, Arabia, and India.

It would be impossible to argue, however, that transatlantic trade did not have a major effect upon the development and scale of slavery in Africa. As the demand for slaves increased with European colonial expansion in the New World, rising prices made the slave trade increasingly lucrative. African states eager to augment their treasuries in some instances even preyed upon their own peoples by manipulating their judicial systems, condemning individuals and their families to slavery in order to reap the rewards of their sale to European traders. Slave exports were responsible for the emergence of a number of large and powerful kingdoms that relied on a militaristic culture of constant warfare to generate the great numbers of human captives required for trade with the Europeans. The Yoruba kingdom of Oyo on the Guinea coast, founded sometime before 1500, expanded rapidly in the eighteenth century as a result of this commerce. Its formidable army, aided by advanced iron technology , captured immense numbers of slaves that were profitably sold to traders. In the nineteenth century, the aggressive pursuit of slaves through warfare and raiding led to the ascent of the kingdom of Dahomey, in what is now the Republic of Benin, and prompted the emergence of the Chokwe chiefdoms from under the shadow of their Lunda overlords in present-day Angola and Democratic Republic of the Congo. The Asante kingdom on the Gold Coast of West Africa also became a major slave exporter in the eighteenth century.

Ultimately, the international slave trade had lasting effects upon the African cultural landscape. Areas that were hit hardest by endemic warfare and slave raids suffered from general population decline, and it is believed that the shortage of men in particular may have changed the structure of many societies by thrusting women into roles previously occupied by their husbands and brothers. Additionally, some scholars have argued that images stemming from this era of constant violence and banditry have survived to the present day in the form of metaphysical fears and beliefs concerning witchcraft. In many cultures of West and Central Africa, witches are thought to kidnap solitary individuals to enslave or consume them. Finally, the increased exchange with Europeans and the fabulous wealth it brought enabled many states to cultivate sophisticated artistic traditions employing expensive and luxurious materials. From the fine silver- and goldwork of Dahomey and the Asante court to the virtuoso wood carving of the Chokwe chiefdoms, these treasures are a vivid testimony of this turbulent period in African history.

Bortolot, Alexander Ives. “The Transatlantic Slave Trade.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History . New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/slav/hd_slav.htm (October 2003)

Further Reading

Hogendorn, Jan, and Marion Johnson. The Shell Money of the Slave Trade . Cambridge : Cambridge University Press, 1986.

Klein, Herbert S. The Atlantic Slave Trade . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999.

Additional Essays by Alexander Ives Bortolot

- Bortolot, Alexander Ives. “ Portraits of African Leadership: Living Rulers .” (October 2003)

- Bortolot, Alexander Ives. “ Portraits of African Leadership: Memorials .” (October 2003)

- Bortolot, Alexander Ives. “ Portraits of African Leadership: Royal Ancestors .” (October 2003)

- Bortolot, Alexander Ives. “ Trade Relations among European and African Nations .” (October 2003)

- Bortolot, Alexander Ives. “ Ways of Recording African History .” (October 2003)

- Bortolot, Alexander Ives. “ Art of the Asante Kingdom .” (October 2003)

- Bortolot, Alexander Ives. “ Asante Royal Funerary Arts .” (October 2003)

- Bortolot, Alexander Ives. “ Asante Textile Arts .” (October 2003)

- Bortolot, Alexander Ives. “ Gold in Asante Courtly Arts .” (October 2003)

- Bortolot, Alexander Ives. “ The Bamana Ségou State .” (October 2003)

- Bortolot, Alexander Ives. “ Women Leaders in African History: Ana Nzinga, Queen of Ndongo .” (October 2003)

- Bortolot, Alexander Ives. “ Women Leaders in African History: Dona Beatriz, Kongo Prophet .” (October 2003)

- Bortolot, Alexander Ives. “ Exchange of Art and Ideas: The Benin, Owo, and Ijebu Kingdoms .” (October 2003)

- Bortolot, Alexander Ives. “ Women Leaders in African History: Idia, First Queen Mother of Benin .” (October 2003)

- Bortolot, Alexander Ives. “ Kingdoms of Madagascar: Malagasy Funerary Arts .” (October 2003)

- Bortolot, Alexander Ives. “ Kingdoms of Madagascar: Malagasy Textile Arts .” (October 2003)

- Bortolot, Alexander Ives. “ Kingdoms of Madagascar: Maroserana and Merina .” (October 2003)

- Bortolot, Alexander Ives. “ Kingdoms of the Savanna: The Kuba Kingdom .” (October 2003)

- Bortolot, Alexander Ives. “ Kingdoms of the Savanna: The Luba and Lunda Empires .” (October 2003)

- Bortolot, Alexander Ives. “ Women Leaders in African History, 17th–19th Century .” (October 2003)

- Bortolot, Alexander Ives. “ Portraits of African Leadership .” (October 2003)

Related Essays

- The Manila Galleon Trade (1565–1815)

- Portraits of African Leadership

- Religion and Culture in North America, 1600–1700

- Trade Relations among European and African Nations

- Visual Culture of the Atlantic World

- Women Leaders in African History, 17th–19th Century

- African Christianity in Kongo

- The Age of Iron in West Africa

- American Federal-Era Period Rooms

- Art of the Asante Kingdom

- George Washington: Man, Myth, Monument

- Gold in Asante Courtly Arts

- Kingdoms of the Savanna: The Luba and Lunda Empires

- Kongo Ivories

- The New York Dutch Room

- The Portuguese in Africa, 1415–1600

- Ways of Recording African History

- Women Leaders in African History: Ana Nzinga, Queen of Ndongo

List of Rulers

- Presidents of the United States of America

- Arabian Peninsula, 1600–1800 A.D.

- Central Africa, 1600–1800 A.D.

- Central America and the Caribbean, 1400–1600 A.D.

- Eastern and Southern Africa, 1400–1600 A.D.

- Guinea Coast, 1600–1800 A.D.

- Guinea Coast, 1800–1900 A.D.

- Maya Area, 1400–1600 A.D.

- Mexico and Central America, 1600–1800 A.D.

- Mexico, 1400–1600 A.D.

- South Asia, 1600–1800 A.D.

- The United States, 1600–1800 A.D.

- Western and Central Sudan, 1600–1800 A.D.

- Western and Central Sudan, 1800–1900 A.D.

- Western North Africa (The Maghrib), 1600–1800 A.D.

- Arabian Peninsula

- The Caribbean

- Central Africa

- Central America

- Guinea Coast

- North Africa

- North America

- South America

The Transatlantic Slave Trade

16th Century–1867

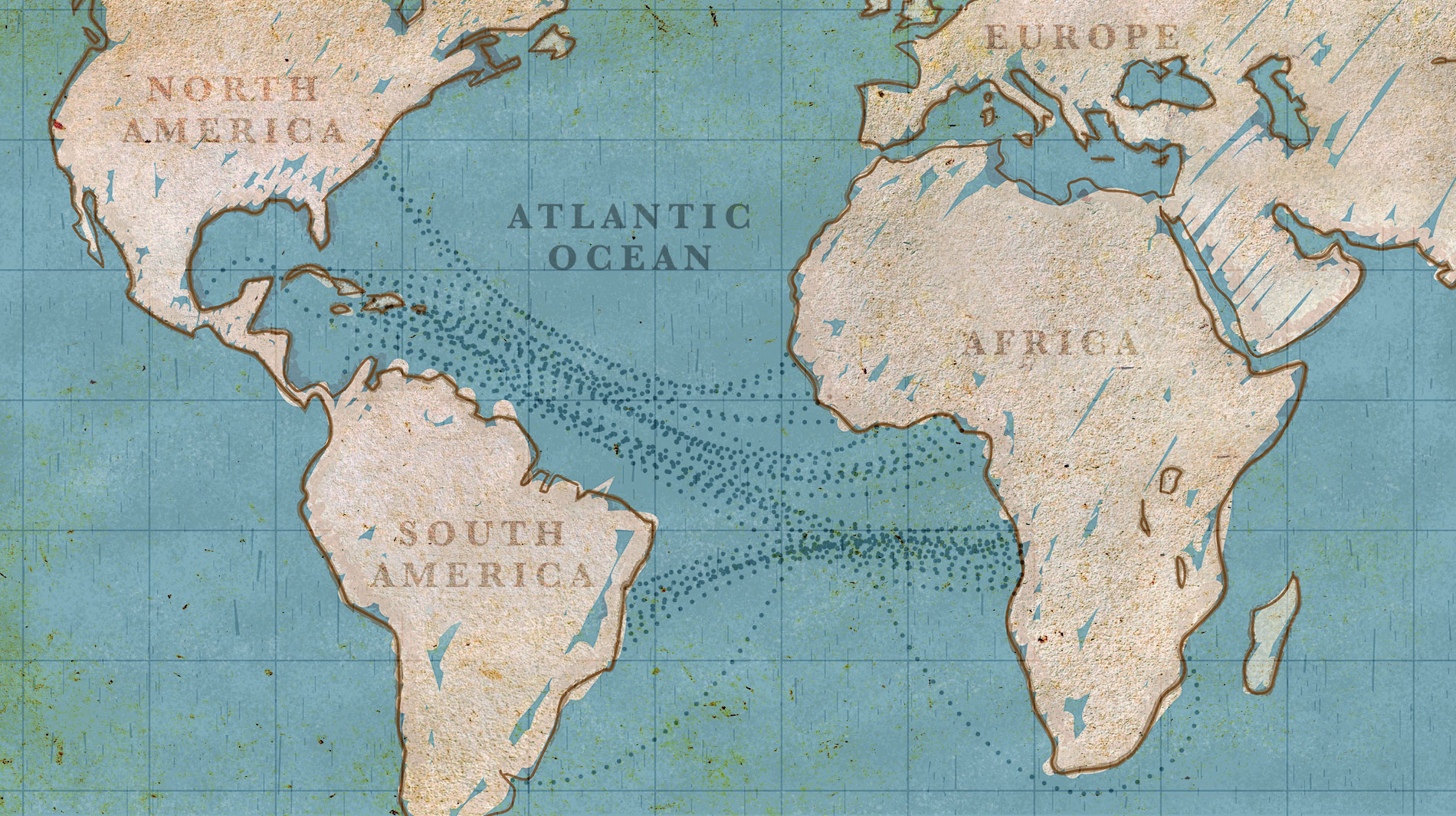

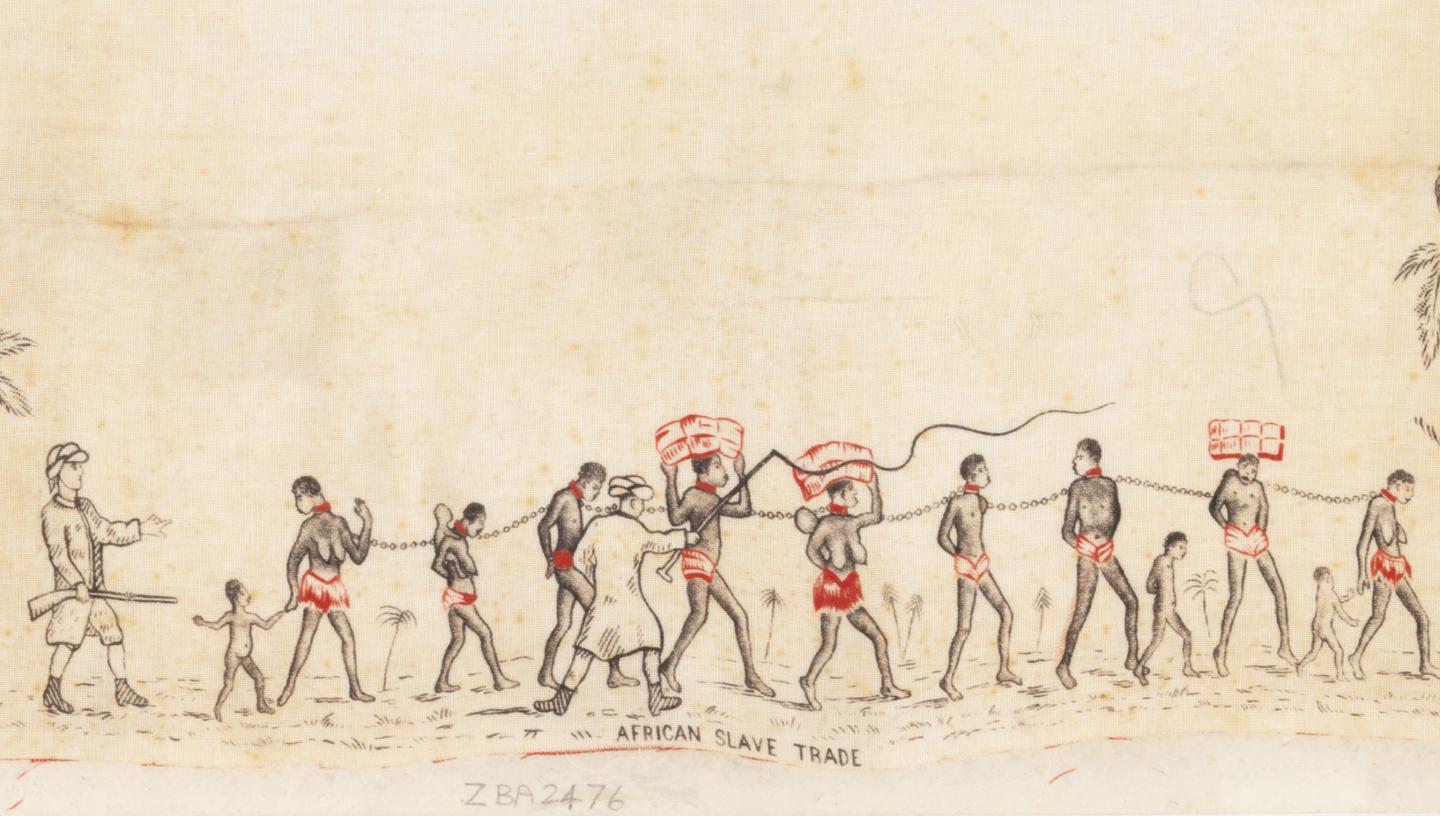

The Transatlantic Slave Trade was a business in which the commodity was African men, women, and children. They were captured in Africa, transported across the Atlantic Ocean over the “Middle Passage,” and forced to work in the Americas. It was also part of the Triangular Trade System and the Mercantile System.

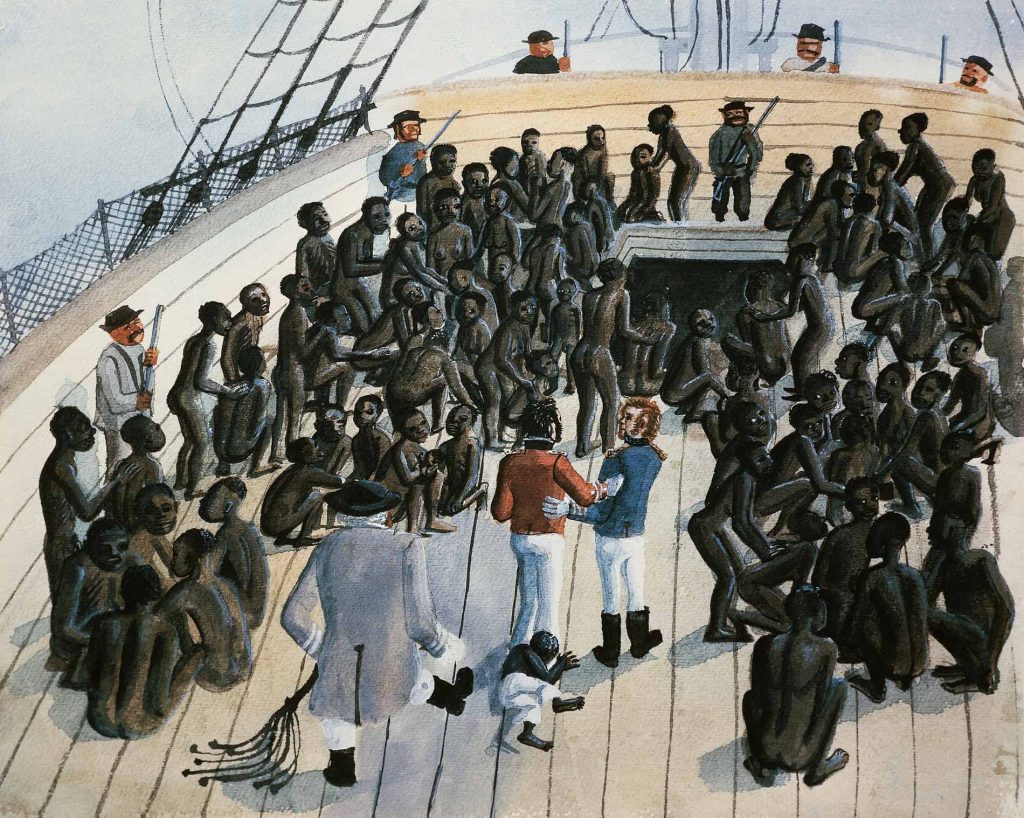

Detail from The Slave Trade by Auguste François Biard, 1840. Image Source: Wikipedia.

What was the Transatlantic Slave Trade?

The Transatlantic Slave Trade was a business network built to profit from the acquisition, transfer, and distribution of African men, women, and children who were forcibly removed from their homes.

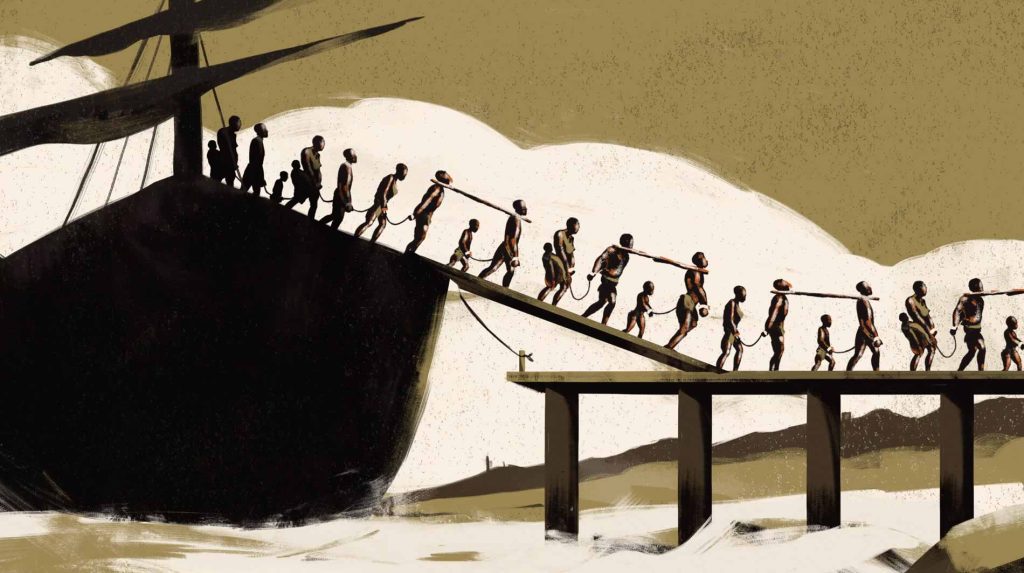

There were two major points of exchange in the network The first was in Africa; the second in the Americas. Bridging the gap between the two points of exchange was the Middle Passage — the horrific overseas route captive Africans were forced to travel as cargo, below deck in the dark holds of slave ships.

Those who survived the Middle Passage were forced to work in the Americas, primarily on plantations, growing and harvesting things like sugar, rice, and cotton. However, many were also put to work in mines and others worked as servants in homes.

The system was lucrative for just about everyone involved in it, especially those directly involved with the exchange of Africans. However, many others benefitted from the products that were produced from slave labor and the wealth it created.

Important Dates in the Transatlantic Slave Trade

16th Century — The Transatlantic Slave Trade begins.

1526 — The first voyage carrying enslaved people from Africa to the Americas is believed to have sailed.

1867 — The business was outlawed, however, the slave trade continued to operate outside of the law.

1700–1850 — More than eight out of ten Africans forced into the system crossed the Atlantic Ocean over the Middle Passage.

1720–1780 — The majority of Africans carried to British North America arrived.

1821–1830 — It is believed more than 80,000 people a year left Africa in slave ships.

By 1825 — Roughly 25% of the population of the Western Hemisphere was made up of Africans who had been enslaved and their ancestors, many of whom were born into slavery.

Transatlantic Slave Trade Statistics

The Transatlantic Slave Trade lasted for approximately 366 years.

It is estimated that 12.5 million African men, women, and children were taken as captives in Africa, sold to merchants, and shipped across the Middle Passage. Roughly 11 million arrived in the Americas. The rest died in some way.

90% of the enslaved Africans were delivered to South America and the Caribbean.

6% of the enslaved Africans were delivered to the American Colonies. The largest number of them entered through Sullivan’s Island, just outside of Charleston, South Carolina.

Roughly 70% of the Africans were forced to work on plantations that produced molasses, sugar, and rum.

Brief History of the Transatlantic Slave Trade

The Transatlantic Slave Trade was started by the Portuguese and Spanish. They were followed by other European nations, including the Netherlands, England, and France.

The business increased with the establishment and expansion of plantations in South America and the Caribbean. This also led other nations and colonies to participate in the business, including the American Colonies.

Slave labor was eventually expanded to plantations that produced valuable goods, including tobacco, cotton, and rice.

The Transatlantic Slave Trade was a key component of Mercantilism, the economic theory that drove European nations to establish colonies in the New World . Cheap labor became a cornerstone of the system and carried over into the Colonial Era in America, particularly in the Southern Colonies where tobacco, rice, indigo, and cotton were vital to the economy.

Transatlantic Slave Trade Facts

The Transatlantic Slave Trade was a lucrative business and benefitted slavers, traders, merchants, plantation owners, and anyone else who was involved.

There were risks involved that could easily reduce profitability — rough weather on the seas, inexperienced crews, outbreaks of disease, uprisings organized by the Africans, and attacks by privateers and pirates.

Over time, the system was modified and streamlined.

Spain essentially outsourced its slave acquisition operation by creating agreements with other nations — Asiento — to supply its colonies with Africans.

Eventually, two significant companies controlled the Transatlantic Slave Trade — the Royal African Company (Britain) and the Dutch West India Company (Netherlands).

The ports where slave traders and merchants operated prospered, due to the influx of wealth. The first ports to prosper were in Europe — Liverpool, Liston, Nantes — and spread to South America — Rio de Janeiro — and North America — Boston, Newport, and Charleston.

The routes traveled by slave ships also allowed the transfer of goods and products from one region to another. This led to the development of the Triangular Trade System which was part of the English Mercantile System that the American Colonies were part of.

After American merchants became involved in the Transatlantic Slave Trade, the routes their ships sailed allowed them to trade with ports in places like the French West Indies. This violated Britain’s maritime laws, the Navigation Acts . Although Americans considered it good business, Britain considered it smuggling. However, during the time of Salutary Neglect , when Britain failed to strictly enforce the Navigation Acts, American merchants prospered.

The Role of Captains, Crews, and Ships of the Transatlantic Slave Trade

Merchants and investors hired ships to transport cargo from one location to another. The cargo could include Africans, along with raw materials, goods, and finished products that could be traded in various ports.

The goods and products that were traded were often seasonal in nature. A number of things affected the business, including growing seasons, the spread of disease, and the weather on the high seas.

Despite the dangers of the voyages, it was in the best interest of the ship’s crew to ensure the safety of the Africans on board. However, Africans were often subjected to violence and brutal conditions that led to many of them dying on the journey across the Atlantic Ocean. Some estimates say as many as 20% of Africans died.

When ships arrived at their port of destination, the captain and crew were responsible for preparing the Africans to be delivered to their owners or to be sold at auctions.

John Hawkins and the English Slave Trade

John Hawkins (c. 1532–1595) was one of the most prolific sailors and commanders of his time. He is most well-known for his role as a “Sea Dog” and for involving England in the Transatlantic Slave Trade. Born in Plymouth, England, Hawkins followed in the footsteps of his father, who was a prominent merchant.

During his early years as a merchant, Hawkins traveled to the Canary Islands, where he saw the use of enslaved Africans. Believing he could profit from the slave trade, he formed a business partnership that was responsible for funding three major slave trading expeditions.

In 1562, he captured and traded for captive Africans along the coast of Africa, and sailed to the Caribbean, where he traded them for pearls, animal hides, and sugar. The expedition was so lucrative that a coat of arms was designed for him, which included a crude drawing of an enslaved African. The first trip is considered by some to be the first implement and profit from the Triangular Trade Route.

Hawkins carried out two more slave expeditions and helped fund another. He was one of the Sea Dogs, a group of privateers who were hired by Queen Elizabeth I to attack Spanish ships.

The others were Sir Francis Drake, Sir Martin Frobisher, and Sir Walter Raleigh, all of whom had connections to the establishment of English colonies in North America. Hawkins and the others were so successful that King Philip II sent the Spanish Armada to invade England, however, most of the fleet was destroyed at the Battle of Gravelines (August 8, 1588). Hawkins served as Vice Admiral of the English Navy during the conflict.

Although Hawkins is praised for his role as a naval commander, he is also identified as the founder of Triangular Trade, which was largely based on the Transatlantic Slave Trade.

Trade Routes in the Transatlantic Slave Trade

The Transatlantic Slave Trade Trade consisted of three main routes along which Africans were acquired, transported, and distributed.

First Route — Acquisition in Africa

Historians indicate that slavery was practiced in Africa in various forms long before the continent was exposed to Europeans. However, the practice was not unique to Africa and was found in every inhabited continent at some time.

When Europeans started trading for captive Africans, it transformed the system of slavery and gave rise to the Transatlantic Slave Trade.

There were three distinct groups involved in the acquisition of Africans for the Transatlantic Slave Trade:

1. Local Slavers — Local slave traders were responsible for kidnapping people and subjugating tribes living in the African interior and then transferring them to the West Coast of Africa. The work of local slavers made large numbers of captives available to the kingdoms on the coast.

2. African Coast Slave Traders — Local slavers delivered their captives to the African kingdoms on the coast, who held them and then traded them to Europeans. The desire for the coastal kingdoms to acquire European goods and products incentivized them to provide more captives for trade.

3. European Slave Traders — Europeans formed business alliances with the kingdoms on the coast and then traded goods and products for the captive Africans. Europeans built forts and factories — trading posts — on the African coast, which were used to acquire and then hold people before they were loaded onto ships.

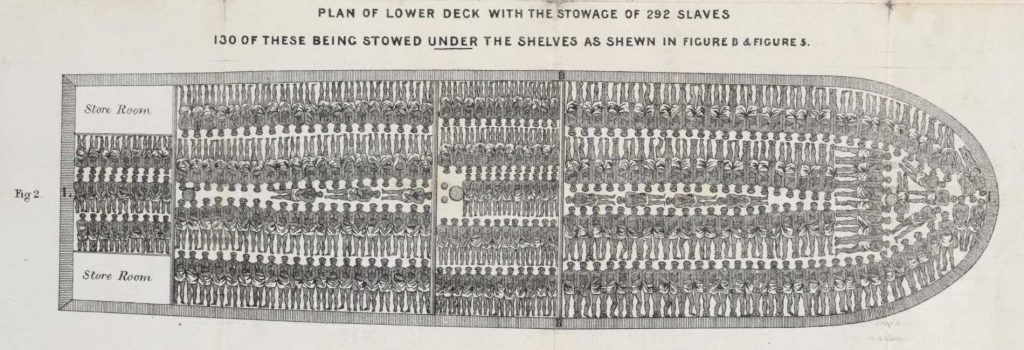

Second Route — Transportation Across the Middle Passage

The Middle Passage was the route that transported captive Africans across the Atlantic Ocean to the Americas and the West Indies, where they were sold into slavery, often to work on large tobacco and sugar plantations.

The conditions on the ships were horrible, as Africans were usually confined below deck in cramped quarters. Many were marked with brands and men were chained together. Many Africans died during the journey and many more suffered from illness or harsh treatment from the crewmembers.

From 1619 to 1860, it is believed roughly 475,000 Africans were abducted and sent to North America, where they landed in a port and were auctioned off as slaves. It is believed that 18-20 percent of the slaves that crossed the Middle Passage died during the journey.

Third Route — Distribution in the Americas

After arriving in the Americas, Africans were forced to travel to their destination, which could be to a plantation deep in the South American forests, the Carolina Backcountry, or slave auctions in large cities like New York, Charleston, and Savannah.

Enslaved Africans in the Americas

The majority of captive Africans were enslaved in the Caribbean and South America. However, enslaved Africans in the American Colonies and the practice of chattel slavery became a key point of disagreement in the United States, eventually leading to the Civil War.

The Age of Exploration led to significant growth in European exploration, as nations and merchants looked for new trade routes and sources of gold and other precious metals.

Christopher Columbus first arrived in the Caribbean in 1492, leading to a massive cultural exchange that was felt worldwide. Initially, the Spanish enslaved the indigenous populations, but eventually moved away from that, replacing them with Africans.

In the Caribbean, Africans were forced to work in mines and on plantations in various locations, including Barbados, Saint-Domingue — present-day Haiti — and Jamaica.

South America

Portuguese explorers followed in the footsteps of Columbus and other Spanish expeditions in exploring the New World and establishing colonies.

The Portuguese arrived in present-day Brazil in the early 1500s and, like the Spanish, enslaved the indigenous population and then transitioned to an African workforce.

By the middle part of the 16th Century, the Portuguese were establishing Sugar Plantations in Brazil and imported Africans to work on them.

Brazil was one area that continued to participate in the Transatlantic Slave Trade into the latter half of the 19th Century.

North America and the American Colonies

In North America, there was a mix of French, Spanish, and English colonies. In the interior of North America, the colonies were largely divided by major geographical landmarks, including the Mississippi River, the Appalachian Mountains, and the Great Lakes.

French colonies formed along the north of the Atlantic Coast, although French territory stretched south to Louisiana, along the Mississippi River. The entire region was known as New France.

New Spain, the Spanish colonies, were located in the Caribbean, South America, and stretched north into the present-day American Southwest, up the coast into the upper regions of present-day California.

The English Colonies developed south and east of New France, along the Atlantic Coast. They went as far south as present-day Georgia. Originally called “Virginia,” the region was eventually divided into 13 Colonies. Colonies in the Chesapeake Bay and further south enjoyed a long growing season due to the climate, which allowed certain crops, including tobacco, rice, indigo, and cotton, to flourish.

Over time, England transformed into Great Britain and a Domestic Slave Trade emerged in the British Colonies, encouraging the exchange of enslaved Africans between colonies and geographical regions. By the middle of the 18th century, the colonies experienced the First Great Awakening, and the seeds of abolition were planted in the minds of many Americans.

Following the American Revolution and the American Revolutionary War, the institution of slavery still drove the economy in many states. By then, production was so high — and dependent on cheap labor — that it was difficult for many merchants and plantation owners to conceive of any other way to continue their operations.

Although the Transatlantic Slave Trade was abolished in the United States in 1808, the Domestic Slave Trade continued to thrive.

In the wake of the Second Great Awakening , the Abolition movement grew, led by former slaves like Harriet Tubman , Sojourner Truth , and Federick Douglass , journalists like William Lloyd Garrison , politicians like Abraham Lincoln , and religious leaders like Henry Ward Beecher .

Impact of the Headright System on the Transatlantic Slave Trade

Several colonies, including Virginia, needed to increase their population and workforce.

The Headright System was developed to encourage settlement . In that system, wealthy landowners paid for settlers to move to America.

In return, the settler agreed to work for the landowner as an Indentured Servant. The company that ran the colony also gave the landowner more land.

However, when servants finished their contracts, they were freed, leaving the landowner with no way to replace the worker.

Eventually, landowners realized that they could use the Headright System to a greater advantage. If they paid to have captive Africans imported into their colony, they received land — and they also created a more permanent, reliable workforce for their plantations.

Transatlantic Slave Trade Significance

The Transatlantic Slave Trade is important to United States history for the role it played in transporting captive and enslaved Africans to the American Colonies. Over time, American merchants, especially in the South, replaced indentured servants with slaves, boosting profits and ensuring a sustainable workforce. However, the institution of slavery was divisive, contributing to decades of disagreement between the North and South, eventually leading to the Civil War.

Transatlantic Slave Trade APUSH Notes and Study Guide

Use the following links and videos to study the Colonial Era, the New England Colonies, the Middle Colonies, and the Southern Colonies for the AP US History Exam. Also, be sure to look at our Guide to the AP US History Exam .

Transatlantic Slave Trade APUSH Definition and Simple Explanation

The Transatlantic Slave Trade was a system of commerce that operated for more than 350 years. It involved the forced movement of millions of Africans across the Atlantic Ocean to the Americas, where they were exploited as forced laborers in various industries, particularly the agrarian economies of the Southern Colonies.

Transatlantic Slave Trade Video for APUSH Notes

This video from Heimler’s History discusses the history of slavery in the British Colonies, including the impact of the Transatlantic Slave Trade.

- Written by Randal Rust

A deep dive into the transatlantic slave trade

Madick Gueye Doctor of underwater archaeology, coordinator of the Slave Wrecks Project, Cultural Engineering and Anthropology Research Unit (URICA) at IFAN, Cheikh Anta Diop University, Dakar (Senegal).

Today known as a place of memory dedicated to the slave trade, the island of Gorée was the largest slave-trading centre on the African coast from the 15 th to the 19 th century. Thousands of human beings passed through this small island some five kilometres from Dakar, Senegal, before being used as forced labour in American plantations. It is estimated that nearly a thousand slave ships wrecked between Africa and the Americas. Only a tiny fraction of these wrecks are known and documented today. Consequently, a huge amount of mapping work needs to be undertaken. Tracking down these archeological remains and exploring the underwater sites would help obtain invaluable scientific data and shed light on the tragic history of the triangular trade.

The waters surrounding the island of Gorée, inscribed on the World Heritage list in 1978, are an important part of this history. This is why, in 2016 and 2017, a team of research divers from the Institut fondamental d'Afrique noire (IFAN) at Cheikh Anta Diop University in Dakar, undertook two underwater archaeological research missions off the coast of the island. Using a magnetometer to detect the presence of metals, combined with a navigation system and a depth sounder, we were able to cover the entire coastline of the island within a radius of 500 metres, recording the data generated with the aid of software. The subsequent work of cataloguing enabled us to identify 24 archaeological sites, confirming the richness of Senegal's underwater cultural heritage.

The Middle Passage

The team then carried out dives in some of the sites. We had a clear mission – to assess the potential of the sites, measure their extent, map the apparent structures and study their environment. This was a decisive factor in the conservation of the remains. So far, IFAN has identified two major sites: HMS Sénégal, which was shipwrecked in 1780, and a second site dating from the early 19 th century that requires more in-depth archaeological assessment before it can be fully identified.

In Senegal the research focuses on the Middle Passage, the transatlantic stage of the triangular trade linking Europe, Africa and the Americas, a field that still remains largely undocumented. Given its strategic position and major role in transatlantic trade relations, Senegambia – historically a geographical area corresponding to the Senegal and Gambia river basins – appears to be a privileged area to be explored.

The Senegalese waters are home to many slave shipwreck sites

For over four centuries, thousands of European slave ships sailed along the coast of West Africa, with the main trading points centred on the coastal regions of Saint-Louis, Gorée, Rufisque, Portudal, Joal, Albreda and Rivières du Sud.

Obstacles to navigation, such as poor visibility and sandbanks, as well as rivalry between European powers, caused many of these vessels to run aground. Reconstructing what life was like on board and the hardship endured by these men and women is one of the aims of our research.

Training at sea and in the classroom

These initial explorations were carried out as part of the Slave Wrecks Project , initiated by the Smithsonian Institution's National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, DC (United States). The aim of the international network of researchers set up by the project is not only to document the history of the transatlantic slave trade, but also to approach it in a new way by placing people at the heart of the story.

Training is an essential dimension of this initiative bringing together Africans and African-American descendants to study underwater archaeology, both at sea and in classrooms. Since 2014, the Slade Wrecks Project has been able to train a network of researchers at IFAN's Archaeology Laboratory in diving and marine archaeology techniques and technology. It has thus been instrumental in setting up the first African-led marine archaeology team in West Africa.

The Cheikh Anta Diop University has established the first African-led marine archaeology team in West Africa

Underwater archaeological sites enable us to re-examine the stories and legacies of the slave trade. By promoting knowledge, the underwater archaeology of the slave trade fosters reconciliation and promotes social justice.

The desire to document slave trade history by studying underwater remains is not something new. Since the late 1980s, researchers such as Max Guérout, a French underwater archaeologist, have been working on the subject. He led two diving missions to the Gorée area in 1988, as part of UNESCO's programme to safeguard the island. The work of Professor Ibrahima Thiaw, a Senegalese archaeologist and specialist in the living conditions of the slaves on Gorée, has also been instrumental in the development of this discipline in Senegal.

A very present past

The transatlantic slave trade is not only a thing of the past – Senegalese social landscapes are still strongly marked by the stigma of slavery. Racial stereotypes arising from the slave trade have had a profound impact on intercultural and interracial relations.

The question of the role played by the African continent in the export of black slaves continues to be debated. This topic, sometimes reduced to simplistic statements, has been the source of misunderstandings and even tensions with Afro-descendant Americans. Africans were undeniably implicated, but the moral and political economy of the slave trade is highly complex and cannot be reduced to clichés or hasty interpretations.

In this context, a better understanding of the past and of the complexity of the transatlantic slave trade is essential to foster dialogue and heal the wounds of the past, wounds which are sometimes still open. Moreover, by involving the local population in the research we will help them take ownership of the black slave trade history.

Provided, however, that the ruins and remains can continue to reveal their secrets to future generations. In fact, underwater archaeological sites face a number of threats. Several dozen metres below the surface, micro-organisms, marine fauna and the mechanical effects of the sea, currents and even fishing gear can destroy wrecks.

Buried in the sediment, sheltered from light and in an oxygen-poor environment, organic matter is well preserved. But once brought to the surface, the objects are fragile and need to be preserved with appropriate conservation treatment. This is particularly true of iron objects and wood. Indeed, the archaeological objects excavated by Max Guérout in the late 1980s are already deteriorating.

Senegal does not yet have a conservation laboratory, which is essential for continuing underwater archaeological excavations

Senegal does not yet have a conservation laboratory, an essential element for continuing underwater archaeological excavations. The creation of such an establishment is therefore imperative for the future of our research and, more broadly, for the documentation of the history of the transatlantic slave trade.

More articles in Ideas

Related items

- Priority Africa

Other recent idea

- Games & Quizzes

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

Transatlantic Slave Trade Causes and Effects

- Tools and Resources

- Customer Services

- African Diaspora

- Afrocentrism

- Archaeology

- Central Africa

- Colonial Conquest and Rule

- Cultural History

- Early States and State Formation in Africa

- East Africa and Indian Ocean

- Economic History

- Historical Linguistics

- Historical Preservation and Cultural Heritage

- Historiography and Methods

- Image of Africa

- Intellectual History

- Invention of Tradition

- Language and History

- Legal History

- Medical History

- Military History

- North Africa and the Gulf

- Northeastern Africa

- Oral Traditions

- Political History

- Religious History

- Slavery and Slave Trade

- Social History

- Southern Africa

- West Africa

- Women’s History

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Article contents

Atlantic slavery and the slave trade: history and historiography.

- Daniel B. Domingues da Silva Daniel B. Domingues da Silva History Department, Rice University

- and Philip Misevich Philip Misevich Department of History, St. John’s University

- https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190277734.013.371

- Published online: 20 November 2018

Over the past six decades, the historiography of Atlantic slavery and the slave trade has shown remarkable growth and sophistication. Historians have marshalled a vast array of sources and offered rich and compelling explanations for these two great tragedies in human history. The survey of this vibrant scholarly tradition throws light on major theoretical and interpretive shifts over time and indicates potential new pathways for future research. While early scholarly efforts have assessed plantation slavery in particular on the antebellum United States South, new voices—those of Western women inspired by the feminist movement and non-Western men and women who began entering academia in larger numbers over the second half of the 20th century—revolutionized views of slavery across time and space. The introduction of new methodological approaches to the field, particularly through dialogue between scholars who engage in quantitative analysis and those who privilege social history sources that are more revealing of lived experiences, has conditioned the types of questions and arguments about slavery and the slave trade that the field has generated. Finally, digital approaches had a significant impact on the field, opening new possibilities to assess and share data from around the world and helping foster an increasingly global conversation about the causes, consequences, and integration of slave systems. No synthesis will ever cover all the details of these thriving subjects of study and, judging from the passionate debates that continue to unfold, interest in the history of slavery and the slave trade is unlikely to fade.

- slave trade

- historiography

From the 16th to the mid- 19th century , approximately 12.5 million enslaved Africans were forcibly embarked on slave ships, of whom only 10.7 million survived the notorious Middle Passage. 1 Captives were transported in vessels that flew the colors of several nations, mainly Portugal, Britain, France, Spain, and the Netherlands. Ships departed from ports located in these countries or their overseas possessions, loaded slaves at one or more points along the coast of Africa, and then transported them to one or more ports in the Americas. They sailed along established trade routes shaped by political forces, commercial partnerships, and environmental factors, such as the winds and sea currents. The triangular system is no doubt the most famous route but in fact nearly half of all slaves were embarked on vessels that traveled directly between the Americas and Africa. 2 Africans forced beneath the decks of slave vessels were captured in the continent’s interior through several means. Warfare was, perhaps, the commonest, yielding large numbers of captives for sale at a time. Other methods of enslavement included judicial proceedings, pawning, and kidnappings. 3 Depending on the routes captives traveled and the ways they were captured, Africans could sometimes find themselves in the holds of ships with people who belonged to their same cultures, were from their same villages, or were even close relatives. 4 None of this, however, attenuated the sufferings and appalling conditions under which they sailed. Slaves at sea were subjected to constant confinement, brutal violence, malnutrition, diseases, sexual violence, and many other abuses. 5

Upon arrival in the Americas, Africans often found themselves in equally hostile environments. Slavery in the mining industry and on cash crop plantations, especially those that produced sugar and rice, significantly reduced Africans’ life expectancies and required owners to replenish their labor force through the slave trade. 6 By contrast, slave systems centered on less intensive crops and the services industry, particularly in cities, ports, and towns, often offered enslaved Africans better chances of survival and even the possibility of achieving freedom through manumission by purchase, gift, or inheritance. 7 These apparent advantages did not necessarily mean that life was any less harsh. Neither did the prospect of freedom significantly change slaves’ material lives. Few individuals managed to obtain manumission and those who did encountered many other barriers that prevented them from fully enjoying their lives as free citizens. 8 In spite of those barriers, slaves challenged their status and conditions in many ways, ranging from “quiet” forms of resistance—slowdowns, breaking tools, and feigning illness at work—to bolder initiatives such as running away, plotting conspiracies, and launching rebellions. 9 Although slavery provided little room for autonomy, Africans strove to maintain or replicate aspects of their cultures in the Americas. Whenever possible, they married people with their same backgrounds, named their children in their own languages, cooked foods using techniques, styles, and ingredients similar to those found in their motherlands, composed songs in the beats of their homelands, and worshipped ancestral spirits, deities, and gods in the same fashion as their forbears. 10 At the same time, slave culture was subject to constant change, a process that over the long run enabled enslaved people to better navigate the dangerous world that slavery created. 11

This overview may seem rather free of controversy, but it is in fact the result of years of debates, some still raging, and research conducted by generations of historians of slavery and the slave trade. Perhaps no other historical fields have been so productive and transformative over such a short period of time. Since the 1950s, scholars have developed and refined new methods, created new theoretical models, brought previously untapped sources to light, and posed new questions that shine bright new light on the experiences of enslaved people and their owners as well as the social, political, economic, and cultural worlds that they created in the diaspora. Although debates about Atlantic slavery and the slave trade go back to the era of abolition, historians began grappling in earnest with these issues in the aftermath of World War II. Early scholarship focused on the United States and tended to articulate views of slavery that reflected elite sources and perspectives. 12 Inspired by the US civil rights movement, second-wave feminism, and wider global decolonization campaigns, the 1960s and 1970s witnessed the rise of approaches to the study of slavery rooted in new social history, which aimed to understand slaves as central historical actors rather than mere victims of exploitation. 13 Around the same time, a group of scholars trained in statistical analysis sparked passionate debates about the extent to which quantitative assessments of slavery and slave trading effectively represented slaves’ lived experiences. 14 To more vividly capture those experiences, some historians turned to new or underutilized tools, particularly biographies, family histories, and microhistories, which provided windows into local historical dynamics. 15 The significance of the penetrating questions that these fruitful debates raised has been amplified in recent decades in response to the growing influence of transnational and Atlantic approaches to slavery. Atlantic frameworks have required the gathering and analysis of new data on slavery and the slave trade around the world, encouraging scholars from previously underrepresented regions to challenge Anglo-American dominance in the field. Finally, the digital turn in the 21st century has provided new models for developing historical projects on slavery and the slave trade and helped democratize access to once inaccessible sources. 16 This article draws on this rich history of scholarship on slavery and the slave trade to illustrate major theoretical and interpretive shifts over time and raise questions about the future prospects for this dynamic field of study.

Models of Slavery and Resistance

While each country in the Americas has its own national historiography on slavery, from a 21st-century perspective, it is hard to overestimate the role that US-based scholars played in shaping the agenda of slavery studies. Analyses of American plantation records began around the turn of the 20th century . Early debates emerged in particular over the conditions of slavery in the American South and views of the relationship between slaves and owners. Setting the foundation for these debates in the early- 20th century , Ulrich Bonnell Phillips offered an extraordinarily romanticized vision of life on the plantation. 17 Steeped in open racism, his work compared slave plantations to benevolent schools that over time “civilized” enslaved peoples. Conditioned by the kinds of revisionist interpretations of Southern slavery that emerged in the era following Reconstruction, Phillips saw American slavery as a benign institution that persisted despite its economic inefficiency. His work trivialized the violence inherent in slave systems, a view some Americans were eager to accept and, given his standing among subsequent generations of slavery scholars, one that prevailed in the profession for half of a century.

Early challenges to this view had little immediate impact within academic circles. That primarily black intellectuals, working in or speaking to white-dominated academies, offered many of the most sophisticated objections helps explain the persistence of Phillips’ influence. In the face of looming institutional racism, several scholars offered bold and fresh interpretations that uprooted basic ideas about the slave system. Over his illustrious career, W. E. B. Du Bois highlighted the powerful structural impediments that restricted black lives and brought attention to the dynamic ways that African Americans confronted systematic exploitation. Eric Williams, a noted Trinidadian historian, took aim at the history of abolition, arguing that self-interest—rather than humanitarian concerns—led to the abolition of slavery throughout the British Empire. Melville Herskovitz, a prominent white American anthropologist, turned his attention to the connections between African and African American culture. 18 Though many of these works were marginalized at the time they were produced, this scholarship is rightfully credited with, among other things, shining light on the relationship between African and African American history. Turning their attention to Africa, scholars discovered a variety of cultural practices that, they argued, shaped the black experience under slavery and in its aftermath. Even those scholars who challenged or rejected this Africa-centered approach pushed enslaved people to the center of their analyses, representing a radical departure from previous studies. 19

Similarly, works focused on the history of slavery and the slave trade in other regions of the Americas, especially those colonized by France, Spain, and Portugal, were often overlooked. The economies of many of these regions had historically depended on slave labor. The size of the captive populations of some of them rivaled that of the United States. Moreover, they had been involved in the slave trade for much longer and far more extensively than any other region of what became the United States. Researchers in Brazil, Cuba, and other countries often noticed these points. 20 Some of them, like the Brazilian sociologist Gilberto Freyre, received training in the United States and produced significant research. However, because they published mainly in Portuguese and Spanish, and translations were hard to come by, their work had little initial impact on Anglo-American scholarship. The few scholars who did realize the importance of this work used it to draw comparisons between the Anglophone and non-Anglophone worlds of slavery, highlighting differences in their patterns of colonization and emphasizing the distinctive roles that Catholicism and colonial legal regimes played in shaping slave systems across parts of the Americas. A greater incidence of miscegenation and slaves’ relative accessibility to freedom through manumission led some scholars to argue that slavery in the non-Anglophone New World was milder than in antebellum America or the British colonies. 21

In the United States, the dominant narratives of American slavery continued to emphasize the absolute authority of slave owners. Even critics of Phillips, who emerged in larger numbers in the 1950s and vigorously challenged his conclusions, thought little of slaves’ abilities to effect meaningful change on plantations. Yet they did offer new interpretations of American slavery, as the metaphors scholars used in this decade to characterize the system attest. Far from Phillips’ training school, Kenneth Stampp argued that plantation slavery more appropriately resembled a prison in which enslaved people became completely dependent on their owners. 22 Going even further, Stanley M. Elkins compared American slavery to a concentration camp. 23 The experience of slavery was so traumatic that it stripped enslaved people of their identities and rendered them almost completely helpless. American slavery, in Elkins’ view, turned African Americans into infantilized “Sambos” whose minds and wills came to mirror those of their owners. While such studies drew much needed attention to the violence of plantation slavery, they all but closed the door on questions about slave agency and cultural production. Emphasizing slave autonomy ran the risk of minimizing the brutality of slave owners, and for those scholars trying to overturn Phillips’s vision of American slavery, that brutality was what defined the plantation enterprise.

It took the revolutionary spirit of the 1960s to move slavery studies in a significantly new direction. Driven by their hard-fought battles for political rights at home, African Americans and others whom the civil rights movement inspired added critical new voices and perspectives that required a rethinking of the American past. Scholars who emerged during this period largely rejected the overwhelming authority of the planter class and instead turned their attention to the activities of enslaved people. Slaves, they found, created spaces for themselves and exercised their autonomy on plantations in myriad ways. While they recognized the violence of the slave system, historians of this generation were more interested in assessing the development of black society and identifying resistance to plantation slavery. Far from the brainwashed prisoners of their owners, enslaved people were recast as producers of dynamic and enduring cultures. One key to this transformation was a more careful analysis of what occurred within slave quarters, where new research uncovered the existence of relatively stable—at least under the circumstances—family life. Another emphasized religion as a tool that slaves used to improve their conditions and forge new identities in the diaspora. The immediate post-civil rights period also saw scholars renew their interest in Africa, breathing new life into older debates about the origins and survival of cultural practices in the Americas. 24

What much of the scholarship in this period shared was the idea that no matter how vicious the system, planter power was always incomplete. Recognizing that reality, slaves and their owners established a set of ground rules that granted slaves a degree of autonomy in an attempt to minimize resistance. Beyond mere brutality, slavery thus rested on unwritten but widely understood slave “rights”—Sundays off from plantation labor, the cultivation of private garden plots, participation in an independent slave economy—that both sides negotiated and frequently challenged. This view was central to Eugene Genovese’s magisterial book, Roll Jordan, Roll: The World the Slaves Made , which employed the concept of paternalism to help make sense of 19th-century Southern slavery. 25 Paternalist ideology provided owners with a theoretical justification for slavery’s continuation in the face of widespread criticism from Northern abolitionists. Unlike in the urban North, Southerners claimed, where free African Americans faced deplorable conditions and had little social support, slave owners claimed to take better care of their “black and white” families. Slaves also embraced paternalism, though toward a different end: doing so enabled them to use the idea of the “benevolent planter” to their own advantage and make claims for incremental improvements in slaves’ lives. Slavery, Genovese argued, was thus based on the mutual interdependence of owners and slaves.

The degree of intimacy between slaves and owners that paternalism implied spoke to another question that occupied scholars writing in the 1960s and 1970s: given the violence of the slave system, why had so few large-scale slave rebellions occurred? For Phillips and those whom he influenced, the benevolent nature of Southern slavery provided a sufficient explanation. But undeniable evidence of the violence of slavery required making sense of patterns—or the seeming lack—of slave resistance. Unlike on some Caribbean islands, where slaves far outnumbered free people and environmental and geographic factors tended to concentrate the location of plantations, conditions in the United States were less conducive to widespread rebellion. Yet slaves never passively accepted their captivity. The literature on resistance during this period deemphasized violent forms of rebellion, which occurred infrequently, and reoriented scholarship toward the variety of ways that enslaved people challenged the domination of slave owners over them. Having adjusted their lenses, historians found evidence of slave resistance seemingly everywhere. Enslaved people slowed the paces at which they worked, feigned illnesses, broke tools, and injured or let escape animals on plantations. Such “day-to-day” resistance did little to overturn slavery but it gave some control to captives over their work regimes. In some cases, slaves acted even more boldly, committing arson or poisoning those men and women responsible for upholding the system of bondage. Resistance also took the form of running away, a strategy that long preceded the famous Underground Railroad in North America and posed unique problems in territories with unsettled frontiers, unfriendly environmental terrain, and diverse indigenous populations into which fleeing captives could integrate. 26

This shift in scholarship toward slave agency and resistance was anchored in the creative use of sources that had previously been unknown or underappreciated. Although they had long recognized the shortcomings of Phillips’s reliance on records from a limited number of large plantations, historians struggled to find better options, particularly those that shed light on the experiences and perspectives of enslaved people. Slave biographies provided one alternative. In the 1970s, John Blassingame gathered an exhaustive collection of runaway slave accounts to examine the life experiences of American slaves. 27 Whether such biographies spoke to the majority of slaves or represented a few exceptional black men became the subject of considerable disagreement. Scholars who were less trusting of biographies turned to the large collection of interviews that the Federal Writers’ Project of the Works Progress Administration conducted with former slaves. 28 Though far more numerous and representative of “typical” slave experiences, the WPA interviews had their own problems. Would former slaves have been comfortable speaking freely to primarily white interviewers about their lives in bondage? The question remains open. Equally pressing was the concern over the amount of time that had passed between the end of slavery and the period when the interviews were conducted. Indeed, some two-thirds of interviewees were octogenarians when federal employees recorded their stories. Despite such shortcomings, these sources and the new interpretations of slavery that they supported pushed scholarship in exciting new directions. Slaves could no longer be dismissed as passive victims of the plantation system. The new sources and approaches humanized them and reoriented scholarship toward the communities that slaves made.

Across the Atlantic, scholars of Africa began to grapple in earnest with questions about slavery, too. Early contributions to debates over the role of the institution in Africa and its impact on African societies came from historians and anthropologists. One strand of disagreement emerged over whether slavery existed there at all prior to the arrival of Europeans. This raised more fundamental questions about how to define slavery. The influential introduction to Suzanne Miers and Igor Kopytoff’s edited volume, Slavery in Africa: Historical and Anthropological Perspectives , took pains to distinguish African slavery from its American counterparts. It rooted slavery not in racial difference or the growth of plantation agriculture but rather in the context of Africa’s kin-based social organization. According to the coauthors, the institution’s primary function in Africa was to incorporate outsiders into new societies. 29 So distinctive was this form of captivity that Miers and Kopytoff famously deployed scare quotes each time they used the word “slavery” in order to underscore its uniqueness.

Given their emphasis on incorporation, the process by which enslaved people over time became accepted insiders in the societies into which they were forcibly introduced, and their limited treatment of the economically productive roles that slaves played, Miers and Kopytoff came in for swift criticism on several fronts. Neo-Marxists were particularly dissatisfied. Claude Meillassoux, the prominent French scholar, responded with an alternative vision of slavery in Africa that highlighted the violence that was at the core of enslavement. 30 That violence made slavery the very antithesis of kinship, which to many scholars invalidated Miers and Kopytoff’s interpretation. Meillassoux and others also pointed to the dynamic economic roles that slaves played in Africa. 31 Studies in various local settings—in the Sokoto Caliphate, the Western Sudan, and elsewhere—made clear that slavery was a central part of how African societies organized productive labor. 32 This reality led some scholars to articulate distinct slave, or African, modes of production that, they argued, better illuminated the role of slavery in the continent. 33

In addition to these deep theoretical differences, one factor that contributed to the debates was the lack of historical sources that spoke to the changing nature of slavery in Africa. Documentary evidence describing slave societies is heavily concentrated in the 19th century , the period when Europe’s presence in Africa became more widespread and when colonialism and abolitionism colored Western views of Africans and their social institutions. To overcome source limitations, academics cast their nets widely, drawing on methodological innovations from anthropology and comparative linguistics, among other disciplines. 34 Participant observation, through which Africanists immersed themselves in the communities they studied in order to understand local languages and cultures, proved particularly valuable. 35 Yet the enthusiasm for this approach, which for many offered a more authentic path to access African cultures and voices, led some scholars to ignore or paper over its limitations. 36 To what extent, for example, did oral sources or observations of social structures in the 20th century reveal historical realities from previous eras? Other historians projected back in time insights from the more numerous written sources from the 19th century , using them to consider slavery in earlier periods. 37 Those who uncritically accepted evidence from such sources—whether non-written or written—came away with a timeless view of the African past, including as it related to slavery. 38 It would take another decade, during which the field witnessed revolutionary changes to the collection and analysis of data, until scholars began to widely accept the fact that, as in the Americas, slavery differed across time and space.

The Cliometric Debates

Around the same time that some scholars in the Americas were pushing enslaved people to the center of slavery narratives, a separate group of academics trained in economics began steering the focus of studies of slavery and the slave trade in a different direction. While research on planter power and slave resistance allowed historians to infer broad patterns of transformation from a limited collection of local records, this new group of scholars turned this approach upside down. They proposed to assess the underlying forces that shaped slavery and the slave trade to better contextualize the individual experiences of enslaved people. This big-picture approach was rooted in the quantification of large amounts of data available in archival sources spread across multiple locations and led ultimately to the development of “cliometrics,” a radically new methodology in the field. Two works were particularly important to the establishment of this approach: Philip Curtin’s The Atlantic Slave Trade: A Census and Robert Fogel and Stanley Engerman’s Time on the Cross: The Economics of American Negro Slavery . 39

Philip Curtin’s “census” provided the first quantitative assessment of the size, evolution, and distribution of the transatlantic slave trade between the 15th and 19th centuries . Previous estimates of the magnitude of the transatlantic trade claimed that it involved somewhere between fifteen and twenty million enslaved Africans—or in some cases many times that amount. 40 However, upon careful examination, Curtin found that such estimates were “nothing but a vast inertia, as historians have copied over and over again the flimsy results of unsubstantial guesswork.” 41 He thus set out to provide a new figure based on a close reading of secondary works that themselves had been based on extensive archival research. To assist in this endeavor, Curtin enlisted a technology that had only recently become available to researchers: the mainframe computer. He collected data on the number of slaves that ships of every nation involved in the traffic had embarked and disembarked, recorded these data on punch cards, and used the computer to organize the information into time series that allowed him to make projections for the periods and branches of the traffic for which data were scarce or altogether unavailable. Curtin’s findings posed profound challenges to the most basic assumptions about the transatlantic traffic. They revealed that the number of Africans forcibly transported to the Americas was substantially lower than what historians had previously assumed. Curtin also demonstrated that while the British were the most active slave traders during the second half of the 18th century , when the trade had reached its height, the Portuguese (and, after independence, Brazilians as well) carried far more enslaved people during the entire period of the transatlantic trade. 42 Furthermore, while the United States boasted the largest slave population by the mid- 19th century , it was a comparatively minor destination for vessels engaged in the trade: the region received less than 5 percent of all captive Africans transported across the Atlantic. 43

Curtin’s assessment of the slave trade inspired researchers to flock to local archives and compile new statistical data on the number and carrying capacity of slaving vessels departing or entering particular ports or regions around the Atlantic basin. Building on Curtin’s solid foundation, these scholars produced dozens of studies on the volume of various branches of the transatlantic trade. Virtually every port that dispatched slaving vessels to Africa or at which enslaved Africans were disembarked in the Americas received scholarly attention. What emerged from this work was an increasingly clear picture of the volume and structure of the Atlantic slave trade at local, regional, and national levels, though the South Atlantic slave trade remained comparatively understudied. 44 Historians of Africa also joined in these discussions, providing tentative assessments of slave exports from regions along the coast of West and West Central Africa. 45 The deepening pool of data that such research generated enabled scholars to use quantitative methods to consider other aspects of the transatlantic trade. How did mortality rates differ on slave vessels from one national carrier to another? 46 Which ports dispatched larger or smaller vessels and what implications did vessel size have for participation in the slave trade? 47 Which types of European commodities were most highly sought after in exchange for African captives? 48 As these questions imply, scholars had for the first time approached the slave trade as its own distinctive topic for research, which had revolutionary consequences for the future of the field.

Time on the Cross had an effect on slavery scholarship that was similar to—indeed, perhaps even greater than—that of Curtin’s, especially among scholars focused on the antebellum US South. Inspired by studies that challenged the view of plantation slavery as unprofitable, Fogel and Engerman, with the help of a team of researchers, set out to quantify nearly every aspect of that institution in the US South, from slaves’ average daily food consumption to the amount of cotton produced in the US South during the antebellum era. 49 Consistent with the cliometricians’ approach, Fogel and Engerman listed ten findings that “contradicted many of the most important propositions in the traditional portrayal of the slave system.” 50 Their most important—and controversial—conclusions were that slavery was a rational system of labor exploitation maintained by planters to maximize their own economic interests; that it was growing on the eve of the Civil War; and that owners were optimistic rather than pessimistic about the future of the slave system during the decade that preceded the war. 51 Further, the authors noted that slave labor was productive. “On average,” the cliometricians argued, a slave was “harder-working and more efficient than his white counterpart.” 52

While cliometrics made important contributions to the study of slavery and the slave trade, the quantitative approach came in for swift and passionate criticism. Curtin’s significantly lower estimates for the number of enslaved Africans shipped across the Atlantic were met with skepticism; some respondents even charged that his figures trivialized the horrors of the trade. 53 Although praised for its revolutionary interpretation, which earned Fogel the Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences in 1993 , Fogel and Engerman’s study of the economics of American slavery was almost immediately cast aside as deeply flawed and unworthy of serious scholarly attention. Critics pointed not only to carelessness in the authors’ data collection techniques but also to their mathematical errors, abusive assumptions, and insufficient contextualization of data. 54 Fogel and Engerman, for example, characterized lynching as a “disciplinary tool.” After counting the number of whippings slaves received at one plantation, they concluded that masters there rarely used the punishment. They failed to note, however, the powerful effect that such abuse had on slaves and free people who merely watched or heard the horrible spectacle. 55 More generally, and apart from these specific problems, critics offered a theoretical objection to the quantitative approach, which, they argued, conceived of history as an objective science, with strong persuasive appeal, but which silenced the voices of the individuals victimized by the history of slavery and the slave trade.

Nevertheless, the methodology found followers among historians studying the history of slavery in other parts of the Atlantic. B. W. Higman’s massive two-volume work, Slave Populations of the British Caribbean, 1807–1834 , remains an unparalleled quantitative analysis of slave communities on the islands under British control. 56 Robert Louis Stein’s The French Sugar Business in the Eighteenth Century also makes substantial use of cliometrics and remains a valuable reference for students of slavery in Martinique and Saint Domingue (present-day Haiti). 57 But outside of the United States, nowhere was cliometrics more popular than Brazil, where scholars of slavery, including Pedro Carvalho de Mello, Herbert Klein, Francisco Vidal Luna, Robert Slenes, and others, applied it to examine many of the same issues that their North American counterparts did: rates of profitability, demographic growth, and economic expansion of slave systems. 58 Africanists also found value in the methodology and employed it as their sources allowed. Patrick Manning, for instance, used demographic modeling to examine the impact of the slave trade on African societies. 59 Philip Curtin compiled quantitative archival sources to analyze the evolution of the economy of Senegambia in the era of the slave trade. 60 Jan Hogendorn and Marion Johnson traced the circulation of cowries, the shell money of the slave trade, noting that “of all the goods from overseas exchanged for slaves, the shell money touched individuals most widely and often in their day-to-day activities.” 61

In many ways, the gap between quantitative and social and cultural approaches to slavery and the slave trade that opened in the 1970s has continued to divide the field. Concerned that cliometrics sucked the dynamism out of interpretations of the slave community and reduced captives to figures on a spreadsheet, some scholars responded by deploying a variety of new tools to reclaim the humanity and individuality of enslaved actors. Microhistory, an approach that early modern Europeanists developed to recover peasant and other everyday people’s stories, offered one such opportunity. 62 Biography provided another. By reducing its scale of observation and focusing on individuals, families, households, or other small-scale units of analysis, such research underscored the messiness of lived experiences and the creative and often unexpected ways that slaves fashioned worlds for themselves. 63 But such approaches raised a separate set of questions: do biographical accounts reveal typical experiences? In an era when few slaves were literate and even fewer committed their stories to paper, any captives whose accounts survived—in full or in fragments, published or unpublished—were by definition exceptional. Moreover, given the clear overarching framework that decades of quantitative work on the slave trade had developed, one would be hard-pressed to ignore completely the cliometric turn. As two quantitatively minded scholars noted, “it is difficult to assess the significance or representativity of personal narratives or collective biographies, however detailed, without an understanding of the overall movements of slaves of which these individuals’ lives were a part.” 64 While an emphasis on what might be described as the quantitative “big picture” is not by nature antagonistic toward social and cultural historians’ concerns with enslaved people’s lived experiences, the two approaches offer different visions of slavery’s past and often feel as if they sit on opposite ends of the analytical spectrum.

Women, Gender, and Slavery

In the roughly two and a half decades that followed the major interpretive shifts that Kenneth Stampp and Stanley Elkins introduced into scholarship on slavery, the field remained an almost exclusively male one. With rare exceptions, men continued to dominate the profession during this period; their work rarely probed with any degree of sophistication the experiences of women in plantation societies. While second-wave feminism inspired women to enter graduate programs in history in larger numbers beginning in the 1960s, it took time for published work on women’s history, at least as it related to slavery, to appear in earnest. Revealingly, it was not until 1985 that the Library of Congress created a unique catalog heading for “women slaves.” Yet in the three decades since then, women’s (and later gendered) histories of slavery have been published at an ever-increasing pace. Scholars in the 21st century would struggle to take seriously books written about slavery that fail to show an appreciation for the distinctive experiences of men and women in captivity or more generally across plantation societies.