The global body for professional accountants

- Search jobs

- Find an accountant

- Technical activities

- Help & support

Can't find your location/region listed? Please visit our global website instead

- Middle East

- Cayman Islands

- Trinidad & Tobago

- Virgin Islands (British)

- United Kingdom

- Czech Republic

- United Arab Emirates

- Saudi Arabia

- State of Palestine

- Syrian Arab Republic

- South Africa

- Africa (other)

- Hong Kong SAR of China

- New Zealand

- Our qualifications

- Getting started

- Your career

- Apply to become an ACCA student

- Why choose to study ACCA?

- ACCA accountancy qualifications

- Getting started with ACCA

- ACCA Learning

- Register your interest in ACCA

- Learn why you should hire ACCA members

- Why train your staff with ACCA?

- Recruit finance staff

- Train and develop finance talent

- Approved Employer programme

- Employer support

- Resources to help your organisation stay one step ahead

- Support for Approved Learning Partners

- Becoming an ACCA Approved Learning Partner

- Tutor support

- Computer-Based Exam (CBE) centres

- Content providers

- Registered Learning Partner

- Exemption accreditation

- University partnerships

- Find tuition

- Virtual classroom support for learning partners

- Find CPD resources

- Your membership

- Member networks

- AB magazine

- Sectors and industries

- Regulation and standards

- Advocacy and mentoring

- Council, elections and AGM

- Tuition and study options

- Study support resources

- Practical experience

- Our ethics modules

- Student Accountant

- Regulation and standards for students

- Your 2024 subscription

- Completing your EPSM

- Completing your PER

- Apply for membership

- Skills webinars

- Finding a great supervisor

- Choosing the right objectives for you

- Regularly recording your PER

- The next phase of your journey

- Your future once qualified

- Mentoring and networks

- Advance e-magazine

- Affiliate video support

- An introduction to professional insights

- Meet the team

- Global economics

- Professional accountants - the future

- Supporting the global profession

- Download the insights app

Can't find your location listed? Please visit our global website instead

- Audit sampling

- Study resources

- Audit and Assurance (AA)

- Technical articles and topic explainers

The Audit and Assurance (AA) and Foundations in Audit (FAU) require students to gain an understanding of audit sampling. While you won’t be expected to pick a sample, you must have an understanding of how the various sampling methods work. This article will consider the various sampling methods in the context of AA and FAU.

This subject is dealt with in ISA 530, Audit Sampling . The definition of audit sampling is:

‘The application of audit procedures to less than 100% of items within a population of audit relevance such that all sampling units have a chance of selection in order to provide the auditor with a reasonable basis on which to draw conclusions about the entire population.’ (1)

In other words, the standard recognises that auditors will not ordinarily test all the information available to them because this would be impractical as well as uneconomical. Instead, the auditor will use sampling as an audit technique in order to form their conclusions. It is important at the outset to understand that some procedures that the auditor may adopt do not involve audit sampling, 100% testing of items within a population, for example. Auditors may deem 100% testing appropriate where there are a small number of high value items that make up a population, or when there is a significant risk of material misstatement and other audit procedures will not provide sufficient appropriate audit evidence. However, candidates must appreciate that 100% examination is highly unlikely in the case of tests of controls; such sampling is more common for tests of detail (ie substantive testing).

The use of sampling is widely adopted in auditing because it offers the opportunity for the auditor to obtain the minimum amount of audit evidence, which is both sufficient and appropriate, in order to form valid conclusions on the population. Audit sampling is also widely known to reduce the risk of ‘over-auditing’ in certain areas, and enables a much more efficient review of the working papers at the review stage of the audit.

In devising their samples, auditors must ensure that the sample selected is representative of the population. If the sample is not representative of the population, the auditor will be unable to form a conclusion on the entire population. For example, if the auditor tests only 20% of trade receivables for existence at the reporting date by confirming after-date cash, this is hardly representative of the population, whereas, say, 75% would be much more representative.

Sampling risk

Sampling risk is the risk that the auditor’s conclusions based on a sample may be different from the conclusion if the entire population were the subject of the same audit procedure.

ISA 530 recognises that sampling risk can lead to two types of erroneous conclusion:

- The auditor concludes that controls are operating effectively, when in fact they are not. Insofar as substantive testing is concerned (which is primarily used to test for material misstatement), the auditor may conclude that a material misstatement does not exist, when in fact it does. These erroneous conclusions will more than likely lead to an incorrect opinion being formed by the auditor.

- The auditor concludes that controls are not operating effectively, when in fact they are. In terms of substantive testing, the auditor may conclude that a material misstatement exists when, in fact, it does not. In contrast to leading to an incorrect opinion, these errors of conclusion will lead to additional work, which would otherwise be unnecessary leading to audit inefficiency.

Non-sampling risk is the risk that the auditor forms the wrong conclusion, which is unrelated to sampling risk. An example of such a situation would be where the auditor adopts inappropriate audit procedures, or does not recognise a control deviation.

Methods of sampling

ISA 530 recognises that there are many methods of selecting a sample, but it considers five principal methods of audit sampling as follows:

- random selection

- systematic selection

- monetary unit sampling

- haphazard selection, and

- block selection.

Random selection This method of sampling ensures that all items within a population stand an equal chance of selection by the use of random number tables or random number generators. The sampling units could be physical items, such as sales invoices or monetary units.

Systematic selection The method divides the number of sampling units within a population into the sample size to generate a sampling interval. The starting point for the sample can be generated randomly, but ISA 530 recognises that it is more likely to be ‘truly’ random if the use of random number generators or random number tables are used. Consider the following example:

Example 1 You are the auditor of Jones Co and are undertaking substantive testing on the sales for the year ended 31 December 2010. You have established that the ‘source’ documentation that initiates a sales transaction is the goods dispatch note and you have obtained details of the first and last goods dispatched notes raised in the year to 31 December 2010, which are numbered 10,000 to 15,000 respectively.

The random number generator has suggested a start of 42 and the sample size is 50. You will therefore start from goods dispatch note number (10,000 + 42) 10,042 and then sample every 100th goods dispatch note thereafter until your sample size reaches 50.

Monetary unit sampling The method of sampling is a value-weighted selection whereby sample size, selection and evaluation will result in a conclusion in monetary amounts. The objective of monetary unit sampling (MUS) is to determine the accuracy of financial accounts. The steps involved in monetary unit sampling are to:

- determine a sample size

- select the sample

- perform the audit procedures

- evaluate the results and arriving at a conclusion about the population.

MUS is based on attribute sampling techniques and is often used in tests of controls and appropriate when each sample can be placed into one of two classifications – ‘exception’ or ‘no exception’. It turns monetary amounts into units – for example, a receivable balance of $50 contains 50 sampling units. Monetary balances can also be subject to varying degrees of exception – for example, a payables balance of $7,000 can be understated by $7, $70, $700 or $7,000 and the auditor will clearly be interested in the larger misstatement.

Haphazard sampling When the auditor uses this method of sampling, he does so without following a structured technique. ISA 530 also recognises that this method of sampling is not appropriate when using statistical sampling (see further in the article). Care must be taken by the auditor when adopting haphazard sampling to avoid any conscious bias or predictability. The objective of audit sampling is to ensure that all items that make up a population stand an equal chance of selection. This objective cannot be achieved if the auditor deliberately avoids items that are difficult to locate or deliberately avoids certain items.

Block selection This method of sampling involves selecting a block (or blocks) of contiguous items from within a population. Block selection is rarely used in modern auditing merely because valid references cannot be made beyond the period or block examined. In situations when the auditor uses block selection as a sampling technique, many blocks should be selected to help minimise sampling risk.

An example of block selection is where the auditor may examine all the remittances from customers in the month of January. Similarly, the auditor may only examine remittance advices that are numbered 300 to 340.

Statistical versus non-statistical sampling

AA students need to be able to differentiate between ‘statistical’ and ‘non-statistical’ sampling techniques. ISA 530 provides the definition of ‘statistical’ sampling as follows:

‘An approach to sampling that has the following characteristics: i. Random selection of the sample items, and ii. The use of probability theory to evaluate sample results, including measurement of sampling risk.’ (2)

The ISA goes on to specify that a sampling approach that does not possess the characteristics in (i) and (ii) above is considered non-statistical sampling.

The above sampling methods can be summarised into statistical and non-statistical sampling as follows:

Statistical sampling allows each sampling unit to stand an equal chance of selection. The use of non-statistical sampling in audit sampling essentially removes this probability theory and is wholly dependent on the auditor’s judgment. Keeping the objective of sampling in mind, which is to provide a reasonable basis for the auditor to draw valid conclusions and ensuring that all samples are representative of their population, will avoid bias.

AA and FAU students must ensure they fully understand the various sampling methods available to auditors. In reality there are a number of ways in which sampling can be applied that ISA 530 recognises – however, the standard itself covers the principal methods.

Students must ensure they can discuss the results of audit sampling and form a conclusion as to whether additional work would need to be undertaken to reduce the risk of material misstatement.

Written by a member of the AA examining team

(1). ISA 530, paragraph 5 (a) (2). ISA 530, paragraph 5 (g)

Related Links

- Student Accountant hub page

Advertisement

- ACCA Careers

- ACCA Career Navigator

- ACCA Learning Community

Useful links

- Make a payment

- ACCA-X online courses

- ACCA Rulebook

- Work for us

Most popular

- Professional insights

- ACCA Qualification

- Member events and CPD

- Supporting Ukraine

- Past exam papers

03.05. Effective Audit Procedures – Sampling

Briefly reflect on the following before we begin:

- Why do auditors often use sampling methods to gather evidence during audits?

- What are some common risks involved in selecting samples during an audit?

- How would an IS Auditor go about selecting samples during an audit?

In this section, we will explore the diverse range of sampling techniques available to IS auditors. We will do so by differentiating between statistical and non-statistical sampling methods, highlighting their respective advantages and appropriate contexts of use. We will explore judgmental sampling, a critical method where the auditor’s professional judgment plays a pivotal role in sample selection; random sampling techniques, which are fundamental to reducing bias and ensuring representativeness in the audit findings; as well as stratified sampling , showcasing how it enhances audit efficiency by categorizing data into relevant strata. Lastly, we will review the importance of software and tools in modern IS auditing, emphasizing how technology aids auditors in executing more precise and effective sampling strategies.

Next, we will discuss the key principles that help determine sufficient sample sizes in IS audits. We will also cover the concept of confidence intervals, an essential statistical tool that helps auditors understand the range within which the true value of the population parameter lies. We will cover the interplay between sample size, risk, and materiality, and how these factors influence the auditor’s decision-making process. Lastly, we will address the challenges and implications of sampling errors in IS audits, such as selection and measurement errors. We will also discuss the strategies for mitigating sampling errors that enable IS Auditors to reduce the likelihood and effect of these errors in their audit work. In doing so, evaluating and reporting sampling errors will be emphasized, highlighting the auditor’s responsibility to communicate these aspects transparently.

Sampling Methods in IS Auditing

Audit sampling emerges as a vital tool in IS auditing, where data volumes can be massive and resources are limited. It is a systematic technique used to examine a subset of data or transactions within a population to conclude the entire dataset. It allows auditors to assess the effectiveness of controls, identify anomalies, and detect errors or irregularities without the need to examine every single transaction or piece of data. This is especially crucial when dealing with extensive datasets that would be impractical to review. By selecting a representative sample, auditors can focus on areas of higher risk or greater significance, optimizing resource allocation. This ensures auditors can conduct thorough audits while efficiently managing time and resources.

Audit sampling is closely linked to risk assessment and materiality considerations as it enables IS auditors to assess the level of risk within a dataset and determine whether errors or irregularities are material enough to impact the overall audit conclusions. High-risk areas may warrant larger sample sizes or more intensive testing, while lower-risk areas may require less extensive sampling. As we know, materiality is a measure of the significance of an error or omission and guides auditors in determining how much evidence is needed. The riskier the audit area, the more evidence we require, leading to larger sample sizes. Conversely, in areas with lower risk, smaller samples may suffice. This relationship is crucial in tailoring the audit to the specific context of the audited entity.

The first method we encounter is statistical sampling . This approach relies on probability theory, ensuring that each element in the population has a known chance of being selected. Its beauty lies in its ability to provide auditors with a quantifiable measure of sampling risk. This risk, the probability that the sample may not represent the population accurately, is a fundamental concept in auditing. The three primarily used statistical sampling approaches include:

Random sampling stands on the principle of equal chance, where every item in the population is equally likely to be selected, ensuring a bias-free approach. Tools and software are often employed to aid this process, bringing in precision and efficiency that manual methods cannot match. Random sampling’s strength lies in its simplicity and fairness, making it a widely accepted method in IS auditing.

Stratified sampling enhances audit efficiency by dividing the population into subgroups or strata. This technique is particularly effective when dealing with heterogeneous populations as it ensures that each stratum is adequately represented in the sample, providing a more accurate view of the entire population.

Systematic sampling , in which an interval (i) is first calculated (population size divided by sample size), and then an item is selected from each interval by randomly selecting one item from the first interval and selecting every ith item until one item is selected from all intervals. Efficiency is a significant advantage, especially when auditing extensive datasets, as it enables auditors to review a sample while maintaining a structured approach. Systematic sampling assumes a uniform data distribution without patterns or anomalies that could skew results and is not an ideal method to use when data exhibits systematic patterns or clustering.

Contrastingly, non-statistical sampling, often used in IS auditing, does not involve this statistical theory. Here, the auditor’s professional judgment is paramount. While this method may not provide a quantifiable measure of risk, it allows for flexibility and adaptability in diverse auditing environments. It’s particularly useful when dealing with complex information systems where specific risks are identified through auditor expertise. The three primarily used non-statistical sampling approaches include the following:

- Judgmental sampling heavily relies on the auditor’s experience and knowledge. In situations where certain aspects of the system are deemed more critical, this method allows auditors to target these areas specifically. It’s an approach where intuition, honed by years of experience, plays a key role. However, auditors must remain vigilant to avoid biases that can skew the audit results.

- Block sampling begins with IS auditors partitioning the dataset into distinct blocks or groups based on specific criteria such as transaction types, periods, or data categories. Rather than randomly selecting individual items or transactions, auditors choose entire blocks for examination. The selection is guided by auditors’ judgment, considering risk, materiality, and audit focus. It allows auditors to concentrate efforts on specific areas of interest, making it suitable for targeted reviews of critical data subsets.

- Haphazard sampling allows auditors to select items without any predetermined pattern or criteria. The selection process relies on auditors’ discretion and can involve simply picking items at random or based on convenience. This approach offers a straightforward way to gather a sample for review, especially when auditors are dealing with a limited dataset or when a formal sampling method may be unnecessary due to the nature of the audit.

It is important to remember that sampling in IS auditing provides a reliable basis for making informed decisions about the information system being audited. Hence, the choice of sampling method should align with the audit’s objectives, the nature of the population, and the specific risks involved. Moreover, as technology advances, the complexity of information systems auditing has escalated, and software tools enable auditors to handle large volumes of data efficiently and accurately. They bring sophistication to sampling methods, allowing auditors to perform more complex analyses and derive more nuanced insights.

Determining the sample size in an IS audit is a critical step that balances thoroughness with efficiency. The process begins with a clear understanding of the audit’s objectives. It’s not about choosing a large sample for comprehensiveness; it’s about choosing the right size to meet our specific IT audit objectives . Understanding confidence intervals is integral to this process. A confidence interval is a range within which we expect the true value of a population parameter to fall. It’s a concept that injects a degree of scientific rigour into our audit conclusions. The width of this interval is influenced by the sample size – larger samples generally result in narrower confidence intervals, offering greater precision. However, larger samples also mean more resources and time. Thus, the auditor must strike a balance, ensuring the sample is sufficient to provide reliable results without being unnecessarily large.

In testing controls (evaluating management’s processes), the IS Auditor applies the following guidance in determining the sample size.

In performing substantive testing (evaluating the underlying activities instead of relying on management’s processes), the IS Auditor will generally test between 1% – 5% of the population with an upper cap of 500 samples. Sampling guidance may vary based on the IS Audit functions’ risk appetite and philosophy.

Sampling Errors and Their Impact on Audit Conclusions

Sampling errors occur when the selected sample does not accurately represent the entire population. This misrepresentation can lead to incorrect conclusions about the system being audited. The primary goal of IS Auditors is to provide accurate and reliable insights into the systems we examine. Sampling errors pose a significant risk to the integrity of the IS auditing work, and it is essential to recognize these errors and understand their potential impact.

There are various types of sampling errors, each with its characteristics and implications. One common type is the selection error, which arises when the method used to select the sample introduces bias. For example, choosing a non-random sample that warrants random selection can lead to skewed results. Another type is the measurement error, which occurs when there is a flaw in how information is collected or recorded. This type of error can significantly distort audit findings. The impact of sampling errors on audit quality and reliability cannot be overstated. When these errors are present, the audit conclusions drawn may be flawed, leading to misguided decisions by stakeholders. This outcome can have far-reaching consequences, especially in high-stakes environments where accurate and dependable audit results are crucial. Therefore, it is imperative for auditors to take steps to minimize the occurrence of these errors.

Mitigating sampling errors involves several strategies. Firstly, careful planning and designing of the sampling process are crucial. This planning includes selecting the appropriate sampling method and ensuring the sample size is adequate for the audit objectives. Secondly, auditors must apply their professional judgment and expertise in executing the sampling plan. This expertise involves being vigilant for signs of potential bias or inaccuracies during the sampling process. Similarly, evaluating and reporting sampling errors is another critical aspect. As auditors, we must identify and mitigate these errors and transparently communicate them in our audit reports. This transparency ensures that stakeholders are aware of the limitations of the audit findings and can interpret the results within the correct context.

In the Spotlight

For additional context on the role and importance of audit sampling, please read the article titled “Audit Sampling” [new tab] .

Henderson, K. (2023). Audit sampling. Wall Street Oasis. https://www.wallstreetoasis.com/resources/skills/accounting/what-is-audit-sampling

Key Takeaways

Let’s recap the key concepts discussed in this section by watching this video.

Source: Mehta, A.M. (2023, December 6). AIS OER ch 03 topic 05 key takeaways [Video]. https://youtu.be/os1wvwFFtqE

Knowledge Check

Review questions.

- Explain the importance of selecting the right sampling method in IS auditing. Provide an example of a situation where you would choose a statistical sampling method over a non-statistical one, and vice versa.

- Explain the concept of sample size determination in IS auditing. How does the level of risk in an audit area influence the choice of sample size?

- What are sampling errors in IS auditing, and how can they impact audit conclusions? Provide an example of a sampling error and its potential consequences in an IS audit.

- What are the key differences between statistical and non-statistical sampling methods in IS auditing, and when would you use each?

- How does an IS auditor determine the appropriate sample size for an audit, and what role do confidence intervals play in this process?

- What is a sampling error in the context of IS auditing, and how can it affect the audit’s conclusions? Give an example.

Essay Question

Sampling methods based on auditors' judgment without the use of statistical theory.

Stratified sampling enhances audit efficiency by dividing the population into subgroups or strata. and is particularly effective when dealing with heterogeneous populations as it ensures that each stratum is adequately represented in the sample, providing a more accurate view of the entire population.

Sampling methods based on probability theory, used to provide a quantifiable measure of sampling risk.

Random sampling stands on the principle of equal chance, where every item in the population is equally likely to be selected, ensuring a bias-free approach.

Systematic sampling, in which an interval (i) is first calculated (population size divided by sample size), and then an item is selected from each interval by randomly selecting one item from the first interval and selecting every ith item until one item is selected from all intervals.

Relies on the auditor's experience and knowledge. In situations where certain aspects of the system are deemed more critical, this method allows auditors to target these areas specifically.

Block sampling begins with IS auditors partitioning the dataset into distinct blocks or groups based on specific criteria such as transaction types, periods, or data categories.

Haphazard sampling allows auditors to select items without any predetermined pattern or criteria. The selection process relies on auditors' discretion and can involve simply picking items at random or based on convenience.

The specific goals and outcomes an IT audit is designed to achieve.

Testing for the actual existence of a financial statement item to ensure its validity and correctness.

The level of risk an organization is willing to accept in pursuit of its objectives.

Auditing Information Systems Copyright © 2024 by Amit M. Mehta is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Audit Sampling: Audit Guide

Introduces statistical and nonstatistical sampling approaches, and features case studies illustrating the use of different sampling methods, including classical variables sampling and monetary unit sampling, in real-world situations.

Subscription

Lynford Graham

Availability

Product Number

An invaluable resource, now updated!

Updated as of December 1, 2019, this guide continues to be an indispensable resource packed with information on sampling requirements and methods.

This guide introduces statistical and nonstatistical sampling approaches, and features case studies illustrating the use of different sampling methods, including classical variables sampling and monetary unit sampling, in real-world situations.

- AU-C sections 200, 230, 265, 300, 315, 320, 330, 450, 505, 520, 530, 700, 720, 940

- Auditors, investigators, management oversight personnel

- This guide addresses how to use nonstatistical and statistical sampling approaches to evaluate characteristics of a balance or class of transactions and to obtain audit evidence.

- This guide was updated to reflect rapid changes in the audit environment and to provide technical professional knowledge for auditors in audit sampling practice for improved efficiency and effectiveness of actual practice

Group ordering for your team

2 to 5 registrants

Save time with our group order form. We’ll send a consolidated invoice to keep your learning expenses organized.

6+ registrants

We can help with group discounts. Email [email protected] US customers call 1-800-634-6780 (option 1 )

The Association is dedicated to removing barriers to the accountancy profession and ensuring that all accountancy professionals and other members of the public with an interest in the profession or joining the profession, including those with disabilities, have access to the profession and the Association's website, educational materials, products, and services. The Association is committed to making professional learning accessible to all. This commitment is maintained in accordance with applicable law. For additional information, please refer to the Association's Website Accessibility Policy . For accommodation requests, please contact [email protected] and indicate the product that you are interested in (title, etc.) and the requested accommodation(s): Audio/Visual/Other. A member of our team will be in contact with you promptly to make sure we meet your needs appropriately.

Ratings and reviews

Related content.

This site is brought to you by the Association of International Certified Professional Accountants, the global voice of the accounting and finance profession, founded by the American Institute of CPAs and The Chartered Institute of Management Accountants.

CA Do Not Sell or Share My Personal Information

- Open access

- Published: 27 May 2024

Patients’ satisfaction with cancer pain treatment at adult oncologic centers in Northern Ethiopia; a multi-center cross-sectional study

- Molla Amsalu 1 ,

- Henos Enyew Ashagrie 2 ,

- Amare Belete Getahun 2 &

- Yophtahe Woldegerima Berhe ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-0988-7723 2

BMC Cancer volume 24 , Article number: 647 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

Metrics details

Patient satisfaction is an important indicator of the quality of healthcare. Pain is one of the most common symptoms among cancer patients that needs optimal treatment; rather, it compromises the quality of life of patients.

To assess the levels and associated factors of satisfaction with cancer pain treatment among adult patients at cancer centers found in Northern Ethiopia in 2023.

After obtaining ethical approval, a multi-center cross-sectional study was conducted at four cancer care centers in northern Ethiopia. The data were collected using an interviewer-administered structured questionnaire that included the Lubeck Medication Satisfaction Questionnaire (LMSQ). The severity of pain was assessed by a numerical rating scale from 0 to 10 with a pain score of 0 = no pain, 1–3 = mild pain, 4–6 = moderate pain, and 7–10 = severe pain Binary logistic regression analysis was employed, and the strength of association was described in an adjusted odds ratio with a 95% confidence interval.

A total of 397 cancer patients participated in this study, with a response rate of 98.3%. We found that 70.3% of patients were satisfied with their cancer pain treatment. Being married (AOR = 5.6, CI = 2.6–12, P < 0.001) and being single (never married) (AOR = 3.5, CI = 1.3–9.7, P = 0.017) as compared to divorced, receiving adequate pain management (AOR = 2.4, CI = 1.1–5.3, P = 0.03) as compared to those who didn’t receive it, and having lower pain severity (AOR = 2.6, CI = 1.5–4.8, P < 0.001) as compared to those who had higher level of pain severity were found to be associated with satisfaction with cancer pain treatment.

The majority of cancer patients were satisfied with cancer pain treatment. Being married, being single (never married), lower pain severity, and receiving adequate pain management were found to be associated with satisfaction with cancer pain treatment. It would be better to enhance the use of multimodal analgesia in combination with strong opioids to ensure adequate pain management and lower pain severity scores.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

Pain is defined as an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with, or resembling that associated with, actual or potential tissue damage [ 1 ]. The prevalence of pain in cancer patients is 44.5-66%. with the prevalence of moderate to severe pain ranging from 30 to 38%, and it can persist in 5-10% of cancer survivors [ 2 ]. Using the World Health Organization’s (WHO) cancer pain management guidelines can effectively reduce cancer-related pain in 70-90% of patients [ 3 , 4 ]. Compared to traditional pain states, the mechanism of cancer-related pain is less understood; however, cancer-specific mechanisms, inflammatory, and neuropathic processes have been identified [ 5 ]. Uncontrolled pain can negatively affect patients’ daily lives, emotional health, social relationships, and adherence to cancer treatment [ 6 ]. Patients with moderate to severe pain have a higher fatigue score, a loss of appetite, and financial difficulties [ 7 ]. Patients fear the pain caused by cancer more than dying from the disease since pain affects their physical and mental aspects of life [ 8 ]. A meta-analysis of 30 studies stated that pain was found to be a significant prognostic factor for short-term survival in cancer patients [ 9 ]. Many cancer patients have a very poor prognosis. However, adequate pain treatment prevents suffering and improves their quality of life. Although the WHO suggested non-opioids for mild pain, weak opioids for moderate pain, and strong opioids for severe pain, pain treatment is not yet adequate in one-third of cancer patients [ 10 ].

Patient satisfaction with pain management is a valuable measure of treatment effectiveness and outcome. It could be used to evaluate the quality of care [ 11 , 12 , 13 ]. Patient satisfaction affects treatment compliance and adherence [ 12 ]. Studies have reported that 60-76% of patients were satisfied with pain treatment, and a variety of factors were found associated with levels of satisfaction [ 3 , 14 , 15 , 16 ]. Studies conducted in Ethiopia reported the prevalence of pain ranging from 59.9 to 93.4% [ 17 , 18 ]. These studies indicate that cancer pain is inadequately treated. Assessment of pain treatment satisfaction can help identify appropriate treatment modalities and further its effectiveness. We conducted this study since there was limited research-based evidence on cancer pain management in low-income countries like Ethiopia. Our research questions were: how satisfied are adult cancer patients with pain treatment, and what are the factors associated with the satisfaction of adult cancer patients with pain treatment?

Methodology

Study design, area, period, and population.

A multi-center cross-sectional study was conducted at four cancer care centers in Amhara National Regional State, Northern Ethiopia from March to May 2023. Those cancer care centers were found in the University of Gondar Comprehensive Specialized Hospital (UoGCSH), Felege-Hiwot Comprehensive Specialized Hospital (FHCSH), Tibebe-Ghion Comprehensive Specialised Hospital (TGCSH) and Dessie Comprehensive Specialized Hospital (DCSH). We selected these centers as they were the only institutions providing oncologic care in the region during the study period.

The UoGCSH had 28 beds in its adult oncology ward and serves 450 cancer patients every month. Three specialist oncologists and 12 nurses provide services in the ward. The FHCSH had 22 beds and provides services for 325 cancer patients every month. Two specialist oncologists, two oncologic nurses, and 7 comprehensive nurses provide services. The TGCSH had eight beds and serves 300 cancer patients every month. There were three specialist oncologists and four oncologic nurses at the care center. The cancer care center at DCSH had 10 beds. It serves 350 cancer patients every month. There was one specialist oncologist, three oncologic nurses, and three comprehensive nurses.

All cancer patients who attended those cancer care centers were the source population, and adult (18+) cancer patients who were prescribed pain treatment for a minimum of one month were the study population. Unconscious patients, patients with psychiatric problems, patients with advanced cancer who were unable to cooperate, and patients with oncologic emergencies were excluded from this study.

Variables and operational definitions

The outcome variable was patient satisfaction with cancer pain treatment, which was measured by the Lubeck Medication Satisfaction Questionnaire. The independent variables were sociodemographic (age, sex, marital status, monthly income, and level of education), clinical (site of tumor, stage of cancer, metastasis), cancer treatment (surgery, chemotherapy, radiotherapy), level of pain, and analgesia (type of analgesia, severity of pain, adequacy of pain treatment, adjuvant analgesic).

- Patient satisfaction

perceptions of the patients regarding the outcome of pain management and the extent to which it meets their needs and expectations. It was measured by a 4-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = agree, 4 = strongly agree) using the LMSQ which has 18 items within 6 subscales that have 3 items in each (effectivity, practicality, side-effects, daily life, healthcare providers, and overall satisfaction) [ 19 ]. Final categorization was done by dichotomizing into satisfied and dissatisfied by using the demarcation threshold formula.

\((\frac{\text{T}\text{o}\text{t}\text{a}\text{l}\,\,\text{h}\text{i}\text{g}\text{h}\text{e}\text{s}\text{t}\,\,\text{s}\text{c}\text{o}\text{r}\text{e} - \text{T}\text{o}\text{t}\text{a}\text{l}\,\, \text{l}\text{o}\text{w}\text{e}\text{s}\text{t}\,\, \text{s}\text{c}\text{o}\text{r}\text{e} }{2}\) ) + Total lowest score [ 20 ]. The highest patient satisfaction score was 70 and the lowest satisfaction score was 26. A score < 48 was classified as dissatisfied, and a score ≥ 48 was classified as satisfied.

The Numeric rating scale (NRS) is a validated pain intensity assessment tool that helps to give patients a subjective feeling of pain with a numerical value between 0 and 10, in which 0 = no pain, 1–3 = mild pain, 4–6 = moderate pain, 7–10 = severe pain [ 21 ].

The Adequacy of cancer pain treatment was measured by calculating the Pain Management Index (PMI) according to the recommendations of the WHO pain management guideline [ 22 ]. The PMI was calculated by considering the prescribed most potent analgesic agent and the worst pain reported in the last 24 h [ 23 ]. The prescribed analgesics were scored as follows: 0 = no analgesia, 1 = non-opioid analgesia, 2 = weak opioids, and 3 = strong opioids. The PMI was calculated by subtracting the reported NRS value from the type of most potent analgesics administered. The calculated values of PMI ranged from − 3 (no analgesia therapy for a patient with severe pain) to + 3 (strong opioid for a patient with no pain). Patients with a positive PMI value were considered to be receiving adequate analgesia, whereas those with a negative PMI value were considered to be receiving inadequate analgesia.

Sample size determination and sampling technique

A single population proportion formula was used to determine the sample size by considering 50% satisfaction with cancer pain treatment and a 5% margin of error at a 95% confidence interval (CI). A non-probability (consecutive) sampling technique was employed to attain a sample size within two months of data collection period. After adjusting the proportional allocation for each center and adding 5% none response, a total of 404 study participants were included in the study: 128 from the University of Gondar Comprehensive Specialized Hospital, 99 from Dessie Comprehensive Specialized Hospital, 92 from Felege Hiwot Comprehensive Specialized Hospital, and 85 from Tibebe Ghion Comprehensive Specialized Hospital.

Data collection, processing, and analysis

Ethical approval.

was obtained from the Ethical Review Committee of the School of Medicine at the University of Gondar ( Reference number: CMHS/SM/06/01/4097/2015) . Data were collected using an interviewer-administered structured questionnaire and chart review during outpatient and inpatient hospital visits by four trained data collectors (one for every center). Written informed consent was obtained from each participant after detailed explanations about the study. Informed consent with a fingerprint signature was obtained from patients who could not read or write after detailed explanations by the data collectors as approved by the Ethical Review Committee of the School of Medicine, at the University of Gondar.

Questions to assess the severity of pain and pain relief were taken from the American Pain Society patient outcome questionnaire [ 24 ]. Patients were asked to report the worst and least pain in the past 24 h and the current pain by using a numeric rating scale from 0 to 10, with a pain score of 0 = no pain, 1–3 = mild pain, 4–6 = moderate pain, 7–10 = severe pain.

The Pain Management Index (PMI) based on WHO guidelines, was used to quantify pain management by measuring the adequacy of cancer pain treatment [ 25 ]. The following scores were given (0 = no analgesia, 1 = non-opioid analgesia, 2 = weak opioid 3 = strong opioid). Pain Management Index was calculated by subtracting self-reported pain level from the type of analgesia administered and ranges from − 3 (no analgesic therapy for a patient with severe pain) to + 3 (strong opioid for a patient with no pain). The level of pain was defined as 0 with no pain, 1 for mild pain, 2 for moderate pain, and 3 for severe pain. Patients with negative PMI scores received inadequate analgesia.

The pain treatment satisfaction was measured by the Lübeck Medication Satisfaction Questionnaire (LMSQ) consisting of 18 items [ 19 ]. Lübeck Medication Satisfaction Questionnaire (LMSQ) has six subclasses each consisting of equally waited and similar context of three items. The subclass includes satisfaction with the effectiveness of pain medication, satisfaction with the practicality or form of pain medication, satisfaction with the side effect profile of pain medication, satisfaction with daily life after receiving pain treatment, satisfaction with healthcare providers, and overall satisfaction. Satisfaction was expressed by a four-point Likert scale (4 = Strongly Agree, 3 = Agree, 2 = Disagree, 1 = Strongly Disagree). The side effect subclass was phrased negatively, marked with Asterix, and reverse-scored in STATA before data analysis.

Data were collected with an interviewer-administered questionnaire. The reliability of the questionnaire was assessed by using 40 pretested participants and the reliability coefficient (Cronbach’s alpha value) of the questionnaire was 91.2%. The collected data was checked for completeness, accuracy, and clarity by the investigators. The cleaned and coded data were entered in Epi-data software version 4.6 and exported to STATA version 17. The Shapiro-Wilk test, variance inflation factor, and Hosmer-Lemeshow test were used to assess distribution, multicollinearity, and model fitness, respectively. Descriptive, Chi-square and binary logistic regression analyses were performed to investigate the associations between the independent and dependent variables. The independent variables with a p-value < 0.2 in the bivariable binary logistic regression were fitted to the final multivariable binary logistic regression analysis. Variables with p-value < 0.05 in the final analysis were considered to have a statistically significant association. The strength of associations was described in adjusted odds ratio (AOR) at a 95% confidence interval.

Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics

A total of 397 patients were involved in this study (response rate of 98.3%). Of the participants, 224 (56.4%) were female, and over half were from rural areas ( n = 210, 52.9%). The median (IQR) age was 48 (38–59) years [Table 1 ]. The most common type of cancer was gastrointestinal cancer 114 (28.7%). Most of the study participants, 213 (63.7%), were diagnosed with stage II to III cancer. The majority of the participants were taking chemotherapy alone (292 (73.6%)) [Table 2 ]. Over 90% of patients reported pain; 42.3% reported mild pain, 39.8% reported moderate pain, and 10.1% reported severe pain. Pain treatment adequacy was assessed by self-reports from study participants following pain management guidelines, and 17.1% of patients responded to having inadequate pain treatment. The majority of patients, 132 (33.3%), were prescribed combinations of non-opioid and weak opioid analgesics for cancer pain treatment. Only 34 (8.6%) cancer patients used either strong opioids alone or in combination with non-opioid analgesics.

Patients’ satisfaction with cancer pain treatment and correlation among the subscales

Most participants strongly agree (243, (61.2%)) with item LMSQ18 in the “overall satisfaction” subscale and strongly disagree (206, (51.9%)) for item LMSQ2 in the “side-effect” subscale respectively [Table 3 ]. The highest satisfaction score was observed in the side-effect subscale, with a median (IQR) of 10 (9–11) [Table 4 ].

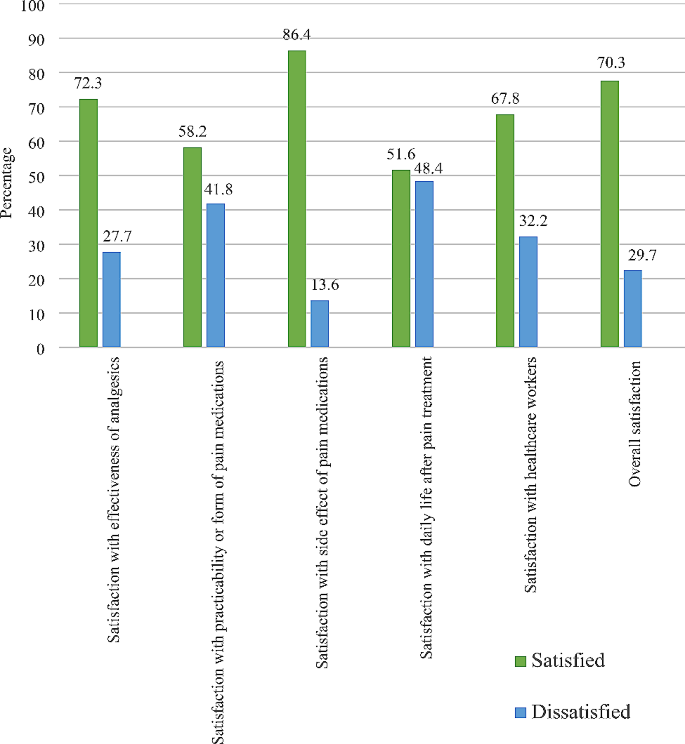

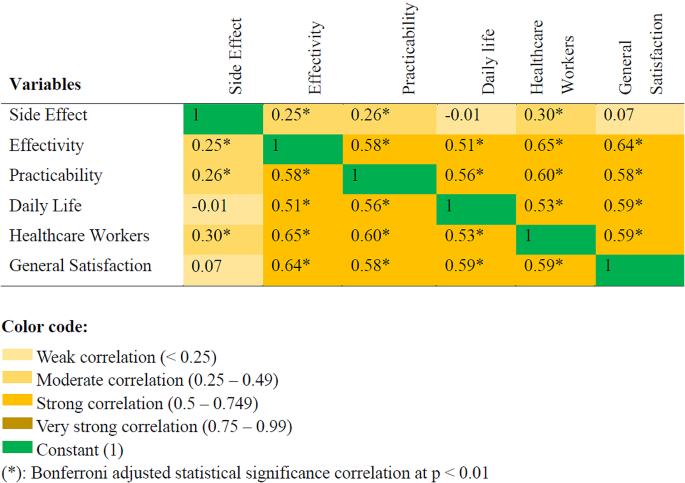

Two hundred and seventy-nine (70.3%) cancer patients were found to be satisfied with cancer pain treatment (CI = 65.6−74.6%). The highest satisfaction rate was observed in the “side-effects” subscale, to which 343 (86.4%) responded satisfied [Fig. 1 ]. A Spearman’s correlation test revealed that there were correlations among the subscales of LMSQ; and the strongest positive correlation was observed between effectivity and healthcare workers subscale (r s = 0.7, p < 0.0001). The correlation among the subscales is illustrated in a heatmap [Fig. 2 ].

Patient satisfaction with cancer pain treatment with each LMSQ subclass, n = 397

A heatmap showing the Spearman correlation of each subclass of pain treatment satisfaction, n = 397

Factors associated with patient satisfaction with cancer pain treatment

In the bivariable binary logistic regression analysis, marital status, stage of cancer, types of cancer treatment, severity of pain in the last 24 h, current pain severity, types of analgesics, and pain management index met the threshold of P-value < 0.2 to be included into the final multivariable binary logistic regression analysis. In the final analysis, marital status, current pain severity, and pain management index were significantly associated with patient satisfaction (P-value < 0.05). Married and single cancer patients had higher odds of being satisfied with cancer pain treatment compared to divorced patients (AOR = 5.6, CI, 2.6–12.0, P < 0.001), (AOR = 3.5, CI = 1.3–9.7, P = 0.017), respectively. The odds of being satisfied with cancer pain treatment among patients who received adequate pain management were more than two times greater than those who received inadequate pain management (AOR = 2.4, CI = 1.1–5.3, P = 0.03). Patients who reported a lesser severity of current pain were nearly three times more likely to be satisfied with cancer pain treatment (AOR = 2.6, CI = 1.5–4.8, P < 0.001) [Table 5 ].

The objective of the present study was to assess patients’ satisfaction with cancer pain treatment at adult oncologic centers. Our study revealed that most cancer patients (70.3%) have been satisfied with cancer pain treatment. This is consistent with studies done by Kaggwa et al. and Mazzotta et al. [ 16 , 26 ]. Whereas, it is a higher rate of satisfaction compared to other studies that reported 33.0% [ 27 ] and 47.7% [ 28 ] of satisfaction. The differences might be possibly explained by the use of different pain and satisfaction assessment tools, the greater inclusion (about 70%) of patients with advanced stages of cancer, the duration of cancer pain treatment, and the adequacy of pain management. In the current study, only 19.6% of patients have been diagnosed with stage IV cancer: patients should take treatment at least for a month, and over 80% of patients have received adequate pain management according to PMI. However, some studies have reported higher rates of satisfaction with cancer pain treatment [ 15 , 29 ]. The possible reason for the discrepancy might be the greater (over 40%) use of strong opioid analgesics in the previous studies. Strong opioids were prescribed only for 8.6% of patients in our study. Due to the complex pathophysiology, cancer pain involves multiple pain pathways. Hence, multimodal analgesia in combination with strong opioids is vital in cancer pain management [ 30 ]. Furthermore, the use of epidural analgesia could be another reason for higher rates of satisfaction [ 29 ].

Regarding satisfaction with subscales of LMSQ, about 80% of patients were satisfied with the information provided by the healthcare providers [ 27 ]. In our study; 67.8% of patients were satisfied with the education provided by healthcare providers about their disease and treatment. In contrast, a higher proportion of participants were satisfied with information provision in a study conducted by Kharel et al. [ 29 ]. Furthermore, we observed the lowest satisfaction rate in the daily life subscale. About 48% of cancer patients were not satisfied with their daily lives after receiving analgesic treatment for cancer pain.

Married and single (never married) cancer patients were found to have higher odds of being satisfied with cancer pain treatment as compared to divorced cancer patients. These findings could be explained by the presence of better social support from family or loved ones. Better social support can enhance positive coping mechanisms, increase a sense of well-being, and decrease anxiety and depression. It also improves a sense of societal vitality and results in higher patient’ satisfaction [ 31 , 32 ].

Patients who had a lower pain score were satisfied compared to those who reported a higher pain score, and this is supported by multiple previous studies [ 16 , 26 , 27 , 29 , 33 , 34 ]. This could be explained by the negative impacts of pain on physical function, sleep, mood, and wellbeing [ 35 ]. Moreover, higher pain severity scores could increase financial expenses because of unnecessary or avoidable emergency department visits; and has a consequence of dissatisfaction [ 23 ]. On the contrary, there are studies that state pain severity does not affect patients’ satisfaction [ 36 , 37 ].

Positive PMI scores were significantly associated with cancer pain treatment satisfaction. Patients who received adequate pain management were highly likely to be satisfied with cancer pain treatment. This finding is similar to that of a study done in Taiwan [ 38 ]. However, a study conducted by Kaggwa et al. has denied any association between PMI scores and cancer pain satisfaction [ 16 ].

Satisfaction with healthcare workers and effectivity of analgesics

This study showed that there was a moderately positive correlation between satisfaction with healthcare workers and satisfaction with patients’ perceived effectiveness of analgesics. This might be explained by a positive relationship between healthcare professionals and patients receiving cancer pain treatment. Healthcare providers who provide health education regarding the effectiveness of analgesics may improve patients’ adherence to the prescribed analgesic agent and improve patients’ perceived satisfaction with the effectiveness of analgesics. A systematic review showed that the hope and positivity of healthcare professionals were important for patients to cope with cancer and increase satisfaction with care [ 39 ]. Increased patient satisfaction with care provided by healthcare workers may change attitude of patients who accepted cancer pain as God’s wisdom or punishment and create a positive attitude toward the effectiveness of analgesics [ 40 ]. Another study supported this finding and stated that healthcare providers who deliver health education regarding the prevention of drug addiction, side effects of analgesics, timing, and dosage of analgesics improve patient attitude and cancer pain treatment [ 41 ].

Correlation of each subclass of cancer pain treatment satisfaction

A Spearman correlation was run to assess the correlation of each subclass of LMSQ using the total sample. There was strong positive correlation (r s = 0.5–0.64) between most of LMSQ subclass at p < 0.01.

A cross-sectional study stated that the effectiveness of analgesic, efficacy of medication and patient healthcare provider communication were associated with patient satisfaction [ 42 ]. In this study, 58.2% of patients were satisfied with the practicability of analgesic medications. Comparable to this study, a cross-sectional study stated that patients who were prescribed convenient, fast-acting medications were more satisfied [ 43 ]. Another study stated that 100% of patients who received sufficient information on analgesic treatment and 97.9% of patients who received sufficient information about the side effects of analgesic treatment were satisfied with cancer pain management [ 44 ]. Patients who were satisfied with their pain levels reported statistically lower mean pain scores (2.26 ± 1.70) compared to those not satisfied (4.68 ± 2.07) or not sure (4.21 ± 2.21) [ 27 ]. This may be explained by the impact of pain on daily activity. Patients who report a lower average pain score may have a lower impact of pain on physical activity compared to those who report a higher mean pain score. Another study also supports this evidence and states that patients who reported a severe pain score and lower quality of life had lower satisfaction with the treatment received [ 45 ].

As a secondary outcome, only 16% of patients were diagnosed to have stage I cancer. This finding could indirectly indicate that there were delays in cancer diagnosis at earlier stage. Further studies may be required to underpin this finding.

In this study, baseline pain before analgesic treatment was not assessed and documented. As a cross-sectional study, we could not draw a cause-and-effect conclusion. Since questions that were used to measure oncologic pain treatment satisfaction were self-reported, answers to each question might not be trustful. The expectation and opinion of the interviewer also might affect the result of the study. These could be potential limitations of the study.

Conclusions

Despite the fact that most cancer patients reported moderate to severe pain, there was a high rate of satisfaction with cancer pain treatment. It would be better if hospitals, healthcare professionals, and administrators took measures to enhance the use of multimodal analgesia in combination with strong opioids to ensure adequate pain management, lower pain severity scores, and better daily life. We also urge the arrangement of better social support mechanisms for cancer patients, the improvement of information provision, and the deployment of professionals who have trained in pain management discipline at cancer care centres.

Data availability

Data and materials used in this study are available and can be presented by the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

Adjusted Odds Ratio

Crude Odds Ratio

Confidence Interval

Dessie Compressive and Specialized Hospital

Felege-Hiwot Compressive and Specialized Hospital

Inter-quartile Range

Lubeck Medication Satisfaction Questionnaire

Numerical Rating Scale

Pain Management Index

Standard Deviation

Tibebe-Ghion Compressive and Specialized Hospital

University of Gondar Compressive and Specialized Hospital

World health organization

Raja SN, Carr DB, Cohen M, Finnerup NB, Flor H, Gibson S, et al. The revised International Association for the study of Pain definition of pain: concepts, challenges, and compromises. Pain. 2020;161(9):1976–82.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Brown MR, Ramirez JD, Farquhar-Smith P. Pain in cancer survivors. Br J pain. 2014;8(4):139–53.

Hochstenbach LM, Joosten EA, Tjan-Heijnen VC, Janssen DJ. Update on Prevalence of Pain in Patients With Cancer: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of pain and symptom management. 2016;51(6):1070-90.e9.

Snijders RAH, Brom L, Theunissen M, van den Beuken-van Everdingen MHJ. Update on Prevalence of Pain in patients with Cancer 2022: a systematic literature review and Meta-analysis. Cancers. 2023;15(3).

Falk S, Dickenson AH. Pain and nociception: mechanisms of cancer-induced bone pain. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(16):1647–54.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Gibson S, McConigley R. Unplanned oncology admissions within 14 days of non-surgical discharge: a retrospective study. Support Care Cancer. 2016;24:311–7.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Oliveira KG, von Zeidler SV, Podestá JRV, Sena A, Souza ED, Lenzi J, et al. Influence of pain severity on the quality of life in patients with head and neck cancer before antineoplastic therapy. BMC Cancer. 2014;14(1):39.

Smith MD, Meredith PJ, Chua SY. The experience of persistent pain and quality of life among women following treatment for breast cancer: an attachment perspective. Psycho-oncology. 2018;27(10):2442–9.

Zylla D, Steele G, Gupta P. A systematic review of the impact of pain on overall survival in patients with cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2017;25(5):1687–98.

Greco MT, Roberto A, Corli O, Deandrea S, Bandieri E, Cavuto S, et al. Quality of cancer pain management: an update of a systematic review of undertreatment of patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(36):4149–54.

Baker TA, Krok-Schoen JL, O’Connor ML, Brooks AK. The influence of pain severity and interference on satisfaction with pain management among middle-aged and older adults. Pain Research and Management. 2016;2016.

Baker TA, O’Connor ML, Roker R, Krok JL. Satisfaction with pain treatment in older cancer patients: identifying variants of discrimination, trust, communication, and self-efficacy. J Hospice Palliat Nursing: JHPN: Official J Hospice Palliat Nurses Association. 2013;15(8).

Naidu A. Factors affecting patient satisfaction and healthcare quality. Int J Health care Qual Assur. 2009.

Davies A, Zeppetella G, Andersen S, Damkier A, Vejlgaard T, Nauck F, et al. Multi-centre European study of breakthrough cancer pain: pain characteristics and patient perceptions of current and potential management strategies. Eur J Pain. 2011;15(7):756–63.

Thinh DHQ, Sriraj W, Mansor M, Tan KH, Irawan C, Kurnianda J et al. Patient and physician satisfaction with analgesic treatment: findings from the analgesic treatment for cancer pain in Southeast Asia (ACE) study. Pain Research and Management. 2018;2018.

Kaggwa AT, Kituyi PW, Muteti EN, Ayumba RB. Cancer-related Bone Pain: patients’ satisfaction with analgesic Pain Control. Annals Afr Surg. 2022;19(3):144–52.

Article Google Scholar

Adugna DG, Ayelign AA, Woldie HF, Aragie H, Tafesse E, Melese EB et al. Prevalence and associated factors of cancer pain among adult cancer patients evaluated at the Oncology unit in the University of Gondar Comprehensive Specialized Hospital, Northwest Ethiopia. Front Pain Res.3:231.

Tuem KB, Gebremeskel L, Hiluf K, Arko K, Hailu HG. Adequacy of cancer-related pain treatments and factors affecting proper management in Ayder Comprehensive Specialized Hospital, Mekelle, Ethiopia. Journal of Oncology. 2020;2020.

Matrisch L, Rau Y, Karsten H, Graßhoff H, Riemekasten G. The Lübeck medication satisfaction Questionnaire—A Novel Measurement Tool for Therapy satisfaction. J Personalized Med. 2023;13(3):505.

Bayable SD, Ahmed SA, Lema GF, Yaregal Melesse D. Assessment of Maternal Satisfaction and Associated Factors among Parturients Who Underwent Cesarean Delivery under Spinal Anesthesia at University of Gondar Comprehensive Specialized Hospital, Northwest Ethiopia, 2019. Anesthesiology research and practice. 2020;2020:8697651.

Breivik H, Borchgrevink P-C, Allen S-M, Rosseland L-A, Romundstad L, Breivik Hals E, et al. Assessment of pain. BJA: Br J Anaesth. 2008;101(1):17–24.

Tegegn HG, Gebreyohannes EA. Cancer Pain Management and Pain Interference with Daily Functioning among Cancer patients in Gondar University Hospital. Pain Res Manage. 2017;2017:5698640.

Shen W-C, Chen J-S, Shao Y-Y, Lee K-D, Chiou T-J, Sung Y-C, et al. Impact of undertreatment of cancer pain with analgesic drugs on patient outcomes: a nationwide survey of outpatient cancer patient care in Taiwan. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2017;54(1):55–65. e1.

Gordon DB, Polomano RC, Pellino TA, Turk DC, McCracken LM, Sherwood G, et al. Revised American Pain Society Patient Outcome Questionnaire (APS-POQ-R) for quality improvement of pain management in hospitalized adults: preliminary psychometric evaluation. J Pain. 2010;11(11):1172–86.

Thronæs M, Balstad TR, Brunelli C, Løhre ET, Klepstad P, Vagnildhaug OM, et al. Pain management index (PMI)—does it reflect cancer patients’ wish for focus on pain? Support Care Cancer. 2020;28:1675–84.

Mazzotta M, Filetti M, Piras M, Mercadante S, Marchetti P, Giusti R. Patients’ satisfaction with breakthrough cancer pain therapy: A secondary analysis of IOPS-MS study. Cancer Manage Res. 2022:1237–45.

Golas M, Park CG, Wilkie DJ. Patient satisfaction with Pain Level in patients with Cancer. Pain Manage Nursing: Official J Am Soc Pain Manage Nurses. 2016;17(3):218–25.

Tang ST, Tang W-R, Liu T-W, Lin C-P, Chen J-S. What really matters in pain management for terminally ill cancer patients in Taiwan. J Palliat Care. 2010;26(3):151–8.

Kharel S, Adhikari I, Shrestha K. Satisfaction on Pain Management among Cancer patient in selected Cancer Care Center Bhaktapur Nepal. Int J Med Sci Clin Res Stud. 2023;3(4):597–603.

Breivik H, Eisenberg E, O’Brien T. The individual and societal burden of chronic pain in Europe: the case for strategic prioritisation and action to improve knowledge and availability of appropriate care. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:1–14.

Gonzalez-Saenz de Tejada M, Bilbao A, Baré M, Briones E, Sarasqueta C, Quintana J, et al. Association between social support, functional status, and change in health‐related quality of life and changes in anxiety and depression in colorectal cancer patients. Psycho‐oncology. 2017;26(9):1263–9.

Yoo H, Shin DW, Jeong A, Kim SY, Yang H-k, Kim JS, et al. Perceived social support and its impact on depression and health-related quality of life: a comparison between cancer patients and general population. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2017;47(8):728–34.

Hanna MN, González-Fernández M, Barrett AD, Williams KA, Pronovost P. Does patient perception of pain control affect patient satisfaction across surgical units in a tertiary teaching hospital? Am J Med Qual. 2012;27(5):411–6.

Naveh P. Pain severity, satisfaction with pain management, and patient-related barriers to pain management in patients with cancer in Israel. Number 4/July 2011. 2011;38(4):E305–13.

Google Scholar

Black B, Herr K, Fine P, Sanders S, Tang X, Bergen-Jackson K, et al. The relationships among pain, nonpain symptoms, and quality of life measures in older adults with cancer receiving hospice care. Pain Med. 2011;12(6):880–9.

Kelly A-M. Patient satisfaction with pain management does not correlate with initial or discharge VAS pain score, verbal pain rating at discharge, or change in VAS score in the emergency department. J Emerg Med. 2000;19(2):113–6.

Lin J, Hsieh RK, Chen JS, Lee KD, Rau KM, Shao YY, et al. Satisfaction with pain management and impact of pain on quality of life in cancer patients. Asia-Pac J Clin Oncol. 2020;16(2):e91–8.

Su W-C, Chuang C-H, Chen F-M, Tsai H-L, Huang C-W, Chang T-K, et al. Effects of Good Pain Management (GPM) ward program on patterns of care and pain control in patients with cancer pain in Taiwan. Support Care Cancer. 2021;29(4):1903–11.

Prip A, Møller KA, Nielsen DL, Jarden M, Olsen M-H, Danielsen AK. The patient–healthcare professional relationship and communication in the oncology outpatient setting: a systematic review. Cancer Nurs. 2018;41(5):E11.

Orujlu S, Hassankhani H, Rahmani A, Sanaat Z, Dadashzadeh A, Allahbakhshian A. Barriers to cancer pain management from the perspective of patients: a qualitative study. Nurs open. 2022;9(1):541–9.

Uysal N. Clearing barriers in Cancer Pain Management: roles of nurses. Int J Caring Sci. 2018;11(2).

Beck SL, Towsley GL, Berry PH, Lindau K, Field RB, Jensen S. Core aspects of satisfaction with pain management: cancer patients’ perspectives. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2010;39(1):100–15.

Wada N, Handa S, Yamamoto H, Higuchi H, Okamoto K, Sasaki T, et al. Integrating Cancer patients’ satisfaction with Rescue Medication in Pain assessments. Showa Univ J Med Sci. 2020;32(3):181–91.

Antón A, Montalar J, Carulla J, Jara C, Batista N, Camps C, et al. Pain in clinical oncology: patient satisfaction with management of cancer pain. Eur J Pain. 2012;16(3):381–9.

Valero-Cantero I, Casals C, Espinar-Toledo M, Barón-López FJ, Martínez-Valero FJ, Vázquez-Sánchez MÁ. Cancer Patients’ Satisfaction with In-Home Palliative Care and Its Impact on Disease Symptoms. Healthcare. 2023;11(9):1272.

Download references

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the University of Gondar Comprehensive Specialized Hospital, Tibebe-Ghion Comprehensive Specialized Hospital, Felege-Hiwot Comprehensive Specialized Hospital, Dessie Comprehensive Specialized Hospital. We would also want to acknowledge Ludwig Matrisch from the Department of Rheumatology and Clinical Immunology, Universität zu Lübeck, 23562 Lübeck, Germany for supporting us on the utilization of the Lübeck Medication Satisfaction Questionnaire (LMSQ) [email protected],

This study was supported by University of Gondar and Debre Birhan University with no conflict of interest. The support did not include publication charges.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Anesthesia, Debre Birhan University, Debre Birhan, Ethiopia

Molla Amsalu

Department of Anaesthesia, University of Gondar, Gondar, Ethiopia

Henos Enyew Ashagrie, Amare Belete Getahun & Yophtahe Woldegerima Berhe

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

‘’M.A. has conceptualized the study and objectives; and developed the proposal. Y.W.B., H.E.A., and A.B.G. criticized the proposal. All authors had participated in the data management and statistical analyses. Y.W.B, M.A., and H.E.A. have prepared the final manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.‘’.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Yophtahe Woldegerima Berhe .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethical Review Committee of the School of Medicine, at the University of Gondar ( Reference number: CMHS/SM/06/01/4097/2015, Date: March 24, 2023 ). Permission support letters were obtained from FHCSH, TGCSH, and DCSH. Written informed consent was obtained from each participant after detailed explanations about the study. Informed consent with a fingerprint signature was obtained from patients who could not read or write after detailed explanations by the data collectors as approved by the Ethical Review Committee of the School of Medicine, at the University of Gondar.

Consent for publication

Not applicable; this article does not include any personal details of any participant.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Amsalu, M., Ashagrie, H.E., Getahun, A.B. et al. Patients’ satisfaction with cancer pain treatment at adult oncologic centers in Northern Ethiopia; a multi-center cross-sectional study. BMC Cancer 24 , 647 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-024-12359-7

Download citation

Received : 17 October 2023

Accepted : 08 May 2024

Published : 27 May 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-024-12359-7

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Cancer pain treatment

- Treatment satisfaction

- Cancer pain

ISSN: 1471-2407

- Submission enquiries: [email protected]

- General enquiries: [email protected]

- International

- Today’s Paper

- Premium Stories

- 🗳️ Elections 2024

- Express Shorts

- Maharashtra SSC Result

- Brand Solutions

Pune Porsche crash case: How DNA analysis of ‘secret’ sample helped cops nail sample swap

The investigation also unearthed financial transactions with the doctors, police said..

In yet another dramatic turn in the Porsche crash in Pune, the City Police on Monday arrested two doctors and a staffer of the state-run Sassoon General Hospital for changing the blood sample of the minor driver, which was collected close to eight hours after the accident and replacing it with another.

A DNA analysis done at a state-run forensics facility following a ‘secret’ blood sample taken because of intelligence inputs helped police unearth a criminal conspiracy involving the senior doctors and the father of the minor driver, further prompting them to probe the involvement of more people. The investigation also unearthed financial transactions with the doctors, police said.

On Monday, the police arrested two Sassoon doctors Dr Ajay Taware, Dr Shrihari Halnor and a Sassoon staffer Atul Ghatkamble on the charges of destruction of evidence by changing the sample collected from the minor. A senior officer said that the probe in this context was launched on Sunday after police received a report from the forensics facility on the DNA analysis of three samples including one taken — as police commissioner Amitesh Kumar said — “secretly”.

Explaining how the blood sample’s destruction came to light, a senior officer said, “The first blood sample of the minor was taken around 11 am at Sassoon General Hospital on May 19. Because of certain inputs about possible tampering, we pressed for another sample collection at 6 pm which was taken at District Hospital in Aundh. The next day, on May 20, the swabs from these two samples were sent to a state run forensics facility for DNA analysis. On May 21, after the father of the minor was arrested, we sent his (the father’s) sample for DNA analysis. The reports of the DNA analysis of these three samples were received on May 26. Reports suggested that the father of the minor was unrelated to the Sassoon swab. The swab from Aundh hospital matched him. This also suggests that the doctors at Sassoon Hospital changed the sample between May 19 and the time we took the swab on the 20th. During initial questioning, the doctors said they had discarded the sample in a dustbin and that it was picked up along with other biomedical waste. The chances of its recovery are not there. Ghatkamble’s primary role was the exchange of money.”

When asked why the second sample was taken and whether there was any intelligence inputs about tampering with the sample, Amitesh Kumar told the media, “After looking at the report of the physical examination around 11 am and with some intelligence reports we were receiving, we realised that we can not rule out the possibility of tampering. That is why a second sample was taken secretly to be tested at a different hospital.”

Late on Monday afternoon, Dr Taware, Dr Halnor and Ghatkamble were produced before court. In his remand application to the court, the investigation officer, Assistant Commissioner of Police Sunil Tambe told the court, “A probe has revealed that financial transactions amounted to bribes taken by the accused in the case to change the sample. For that we will be searching their homes. Police custody of the accused is required for the recovery of the money.”

“The minor’s father has been named as an accused in the charges of changing the sample. Technical evidence suggests that the father was in direct contact with Dr Taware,” Kumar told reporters earlier on Monday.

When asked whether the role of any other person other than the father or any other functionaries from Sassoon General Hospital were being investigated, Kumar said, “I want to reiterate that we are probing this case with utmost diligence. All possible angles are being investigated. We are also looking into the CCTV footage from the Sassoon Hospital. All possible angles are being probed.”

Click here to join Express Pune WhatsApp channel and get a curated list of our stories

- Pune Porsche crash

Panchayat's third season maintains its authentic and relatable tone, focusing on character development and exploring larger themes. The show avoids unnecessary theatrics and showcases the growth and aspirations of its characters in a realistic manner. With a talented cast, Panchayat continues to charm viewers with its understated yet captivating portrayal of rural life.

- AP EAMCET 2024 Result Live Updates: AP EAPCET rank card link at cets.apsche.ap.gov.in today 46 mins ago

- Delhi News Live Updates: CJI to take decision on Kejriwal's plea for 7-day extension on interim bail 47 mins ago

- Maharashtra SSC 10th Results 2024 Live Updates: Grade improvement application from May 31 onwards 54 mins ago

- Mumbai News Live Updates: Six injured after fire breaks out in Mumbai's Dharavi area 2 hours ago

Best of Express

Buzzing Now

May 28: Latest News

- 01 Pune Porsche crash case: MLA Tingre’s recommendation letter for tainted doctor resurfaces to embarrass NCP

- 02 Social Buzz: From Congress’ tutorial on how to peel oranges to BJP’s London-Italy jibe at SP-Cong alliance

- 03 Georgian parliament committee rejects presidential veto of the divisive ‘foreign agents’ legislation

- 04 RDSO likely to test rolling stock of underground Metro 3 in 1st week June

- 05 Sexual harassment case filed against SPPU student

- Elections 2024

- Political Pulse

- Entertainment

- Movie Review

- Newsletters

- Web Stories

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Methods of sampling. ISA 530 recognises that there are many methods of selecting a sample, but it considers five principal methods of audit sampling as follows: random selection. systematic selection. monetary unit sampling. haphazard selection, and. block selection. Random selection.

including specific requirements involving statistical sampling. Audit sampling can be used to collect and analyze evidence during the audit. Deciding whether to use audit sampling is a critical component to audit planning. It is considered early to ensure that sampling procedures, or a combination of procedures, will assist in efficiently achieving

Footnotes (AS 2315 - Audit Sampling): 1 There may be other reasons for an auditor to examine less than 100 percent of the items comprising an account balance or class of transactions. For example, an auditor may examine only a few transactions from an account balance or class of transactions to (a) gain an understanding of the nature of an entity's operations or (b) clarify his understanding ...

The auditors will only verify selected items, and through sampling, can infer their opinion on the entire population of items. There are two forms of sampling: 1. Statistical audit sampling. Statistical audit sampling involves a sampling approach where the auditor utilizes statistical methods such as random sampling to select items to be verified.

Appendix 1: Stratification and Value-Weighted Selection. Appendix 2: Examples of Factors Influencing Sample Size for Tests of Controls. Appendix 3: Examples of Factors Influencing Sample Size for Tests of Details. Appendix 4: Sample Selection Methods International Standard on Auditing (ISA) 530, Audit Sampling, should be read in conjunction ...

The auditor usually will have no special knowledge about other account balances and transactions that, in his judgment, will need to be tested to fulfill his audit objectives. Audit sampling is especially useful in these cases. .03There are two general approaches to audit sampling: nonstatistical and statistical.