Hobbes vs. Locke Essay

In studying the influence of the social contract theory on the American nation historians and philosophers always mention the names of two philosophers, John Locke and Thomas Hobbes. The two philosophers had divergent viewpoints about people, freedom and politics.

Whereas John Locke held the view that all individuals were born free with the capacity to make independent decisions either as individuals or collectively as a group in pursuit of liberty and preservation of life in peaceful coexistence with each other, Thomas Hobbes held the views that human beings were selfish, in constant war with each other and incapable of surviving without the input of a strong and absolute ruler who would protect there collective right to life (Hume 452-73).

The founding fathers of the American nation decision to reject the social contract theory as advocated by Hobbes was valid then as it is today, an examination of nations that have adopted Hobbes theory such as North Korea and Burma reveals that absolute leadership can have negative consequences on peoples civil liberties and rights.

The idea that an absolute leader will always make the best decisions for the good of the nation is not always right. The founding fathers faith in Locke’s values on the social contract is evident in the American government success in promoting peaceful co-existence of different cultures and people (Gaus 84-119).

The main concern of Locke when he advocated his social contract theory was the protection of civil liberties which were always going to be under threat if Hobbes theory was to be adopted by any republic. Locke viewed the “sovereignty” or monarch as a threat to civil societies and consequently could not be trusted with the task of protecting the interests of its citizens.

The governance system that was adopted by the framers of the American constitution that gave each arm of the government sufficient authority and powers to function as well as strong checks and balances between them was a sign of support of Locke’s ideas on politics, freedom and people, and would surely get widespread support today as it did in the 18 th century.

I hold the opinion that the first statement holds some truth in it even though Locke’s ideals seemed to have been accepted during the formation of the American state, in today’s world the government is increasingly taking control of our daily lives from smoking in public places, to increased government involvement in our diet, health, trade, leisure among others it seems the Orwellian world is fast becoming a reality with increased government surveillance in whatever we do, in private or public.

Hobbes acknowledged certain essential attributes of the ‘sovereign’, in any social contract; one of which entailed people having no right to criticize the government for any decisions they make for the ‘good of the nation’, censorship and political correctness is now generally accepted as part of modern day reality (Mack 45-73). In ending, Hobbes held he view that the sovereign was steadfast and could be trusted to use his vast powers for the good of society.

Individual rights were subordinate or subservient to state power and could be removed at any time by the state for the overall good. It seems man is ready to endure appalling laws such as the Patriot Act or oppressive rule purely for the sake of avoiding living in a state of war.

John Locke’s social contract theory influence on America is unquestionable and the second statement clearly demonstrates that reality; the countries constitution and criminal justice system borrows heavily from Locke’s social contract theory.

Locke held the view that in the ‘state of nature’ man had the capacity to own land and property and therefore the government could not grant that right to man this meant that property rights existed before the formation of the ‘sovereignty’, Locke postulated that in the natural state man had the inalienable right to life and resources and man could translate shared resources into private property (Gaus 84-119).

These rights are independent of government and are not dependant on the existence of the same; Locke’s idea was that the government’s role on the issue of property rights both physical and abstract was that of a facilitator and not a competitor. It is thus encouraging to note that our founding fathers choose Locke’s ideas over Hobbes.

The Fifth Amendment is an embodiment of Lockean ideals which protect individual property rights, and the right for fair compensation should the state requires private property for public use. This right has also been protected by the federal courts which have recognized the importance of due process and property rights as enshrined in the American constitution.

Works Cited

Gaus, Gerald F. “On Justifying the Liberties of the Moderns.” Social Philosophy & Policy 25.1 (2007): 84-119.

Hume, David. “Of the Original Contract.” Essays Moral, Political, and Literary. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1963. 452-473.

Mack, Eric. “Scanlon as a Natural Rights Theorist.” Politics, Philosophy & Economics 6. February (2007): 45-73.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2018, June 29). Hobbes vs. Locke. https://ivypanda.com/essays/hobbes-vs-locke/

"Hobbes vs. Locke." IvyPanda , 29 June 2018, ivypanda.com/essays/hobbes-vs-locke/.

IvyPanda . (2018) 'Hobbes vs. Locke'. 29 June.

IvyPanda . 2018. "Hobbes vs. Locke." June 29, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/hobbes-vs-locke/.

1. IvyPanda . "Hobbes vs. Locke." June 29, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/hobbes-vs-locke/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Hobbes vs. Locke." June 29, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/hobbes-vs-locke/.

- State of Nature: Thomas Hobbes and John Locke

- "Leviathan" by Thomas Hobbes

- Thomas Hobbes' and Classical Realism Relationship

- Resume of Max Weber’s Politics as a Vacation

- Terror and Terrorism

- Policy Brief: Why Marijuana Use Should Be Legalized in the Us

- John Lennon’s Imagine and Marxism

- Modernization and Democracy

Thomas Hobbes and John Locke

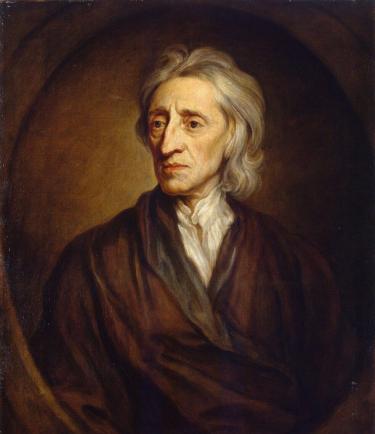

Thomas Hobbes and John Locke were two of the most important political philosophers of the modern era. While their theories were different in many respects, they jointly laid the ground for modern liberalism, modern political philosophy, and modern political economy. Hobbes’s greatest contribution was his innovative framework and concepts such as the state of nature, indivisible sovereign rights vested in civil authority, and the idea that an all-powerful political authority could be created by men rather than by God. Hobbes argued that the natural state of men was a state of all against all, as everyone would have the right to use all and any means for self-preservation, where everyone would have the right to everything. From this, he argued that it was natural for men to desire peace and that any form of government capable of preserving peace was better than civil war. He called for the creation of the Leviathan, an omnipotent, sovereign, civil, political power that was the only form of government capable of preventing civil war. Citizens in Hobbes’s commonwealth were subjects who voluntarily gave up almost all of their power and rights (aside from the right to self-preservation) to create the Leviathan because any form of peace was preferable to the war of all against all. In short, Hobbes argued that, without an omnipotent sovereign, political power, society could not exist.

Locke completely rejected Hobbes’s depiction of the state of nature. For him, the state of nature was a benign, perfect political society without any drawbacks. It’s a society where every offense was punished according to the natural law, which meant that there was a common law and all punishments were impartial and fair. Every law, because all laws in the state of nature were natural laws, was intuitive and intelligible to all members of society. In the state of nature, no one was subject to the arbitrary and unjust will of other humans, because everyone was subject to the natural law and natural law only. Locke’s state of nature was an inversion of Hobbes’s state of nature. Rather than a murderous free for all, it was a society of free and voluntary associations, which, in Hobbes’s framework, was anti-political.

In Locke’s conception, political society emerged because men are not perfectly rational creatures. According to Locke, the natural condition, while rational and intelligible, was also full of dangers to men. Men, because of the anxiety inspired by continuous dangers, were not able to interpret natural laws rationally and were impelled to form civil societies that could better alleviate their anxieties and fears. In contrast with Hobbes, Locke’s political society was built upon the common anxiety inspired by the state of nature and, implicitly, nature itself, while Hobbes’s Leviathan was inspired by the common fear of civil war, which was man-made. As a solution, Locke’s political society aims to imitate the state of nature, which was rejected by men because of their weakness and anxiety rather than the defects of the state of nature. Hence, its priority for Locke was to recreate an impartial society by creating a set of common laws, an impartial judiciary, and an executive system. Conquering nature was never part of political liberalism, probably because it was pessimistic in intellectual temperament.

In a way, Locke flipped the script of Hobbes on its head (and probably the script of most political philosophers before the modern era). While Hobbes theorized that society could not exist without a sovereign, civil power keeping internal and external peace, Locke argued that an ideal state of society that’s also the ideal political society existed before any man-made government. The ideal society was only corrupted because men were not perfectly rational and prone to anxieties caused by dangers posed by the state of nature. This anxiety corrupted men and impelled them to form political societies that could alleviate their anxiety and fear of nature and the dangers nature posed. However, because men moved away from the state of nature out of their weakness and did not reject the voluntary ideal, all political societies were fundamentally imitations of the state of nature. Legitimacy, then, lay with the society, which created political society to rediscover its ideal state in the state of nature. In Hobbes’s Leviathan, men move from the state of nature, which was a state of perpetual war, toward a state of peace, by forming a social contract with each other to give almost all their rights and power to a sovereign power to guarantee peace among them. They moved from a very undesirable state of nature, which was full of war, to a much more desirable, peaceful political society, and they gave up their power directly to the Leviathan, a political institution.

In Locke’s political society, men formed a social contract and gave up their rights and power to the society, and the society put the power in the hands of the institution and people it judged appropriate. However, when a government no longer performed or came into conflict with society, power naturally reverted to society. Locke’s men, in contrast to Hobbes’s men, moved from the ideal state (state of nature) to a corrupted state (state of nature where men felt anxiety due to the danger posed by nature), to an imitation of the ideal state, which was the political society. Moreover, they never gave up their rights and powers to a political institution, but to society itself. Hence, for Locke, legitimacy resided in society rather than political institutions. Aside from the debate on whether any of this was historically accurate (they are not), Locke took the legitimacy out of political institutions and political philosophy and put it into society and social science, or provided the justification for it in the long run. Locke also, arguably, cemented the anti-political nature of liberalism and pushed it into the synthesis with economics, particularly with his study of private property.

John Locke’s biggest contribution to the study of political economy was his innovative notion of private property, which was composed of three elements. One, Locke argued that physical labor transformed unproductive land into the private property of the laborer, paving the way for the labor theory of value and the argument that individuals own the fruit of their labor, the former eventually leading to Marxist economic theory, while the latter to Marx’s revolutionary theory. Two, Locke argued that private property was not a political institution, as postulated by Hobbes, but a social institution dependent on social recognition. Three, Locke argued that private property was the foundation of the political order and the instrument for eliciting the tacit consent of the people for the social contract. When people exercised property rights, Locke argued, people also gave implicit and tacit consent to the existing political system, which guaranteed the exercise of property rights they utilized. This also was a bulwark against radicalism. A popular argument of the time was that, because different generations faced different difficulties, had different desires, and different circumstances, they should be allowed to form different institutions and deal with the situation in their way. However, by inheriting the private property of the previous generation, the subsequent generation gave implicit consent to the existing political order. Changes were still possible. It just had to come through the existing system, rather than revolution.

POLSC101: Introduction to Political Science

Thomas hobbes and john locke.

This article presents a philosophical perspective on the existence of governments within the international system. Compare the views of Locke and Hobbes. Think back to the theories of international relations you read previously. Do you see any connections between Locke's views, Hobbes' views, and the perspectives of realism and liberalism?

Why do we need government? In search of the answer to this question, two English philosophers, both writing in the later half of the 17th Century, asked another question: What would the world be like if there were no government?

In Leviathan (1651), Thomas Hobbes (1588-1679), conjured up a time and place before governments existed. Humankind before the invention of government, Hobbes believed, was in a "state of nature" in which the life-sustaining needs and passions of individuals dictated their interactions with each other. With no governmental authority to settle disputes between individuals, each person acted as a sovereign – an authority that answers to no one but itself. Because every individual in the state of nature was autonomous and because food and other items people wanted were scarce, life in the state of nature would be characterized by an incessant war of "every man against every man". It was an existence that Hobbes characterized as "solitary, poor, nasty, brutish and short".

Hobbes argued that it was the violence and uncertainty of life in the state of nature that motivated people to form governments. Because life was so bad in the state of nature, Hobbes argued that the desire for peace and stability would become so profound that the people would seek out a "sovereign" or ruler to whom they could transfer or give their own sovereignty. In return, the sovereign would provide the peace and stability the people wanted. So long as they abided by the laws the sovereign established, the people would then be free to pursue happiness without constantly fearing for their lives and property.

At the time when government was formed, Hobbes maintained that the people gave up their sovereignty absolutely and permanently. The sovereign, however, did not participate directly in the agreement made by the people to transfer their sovereignty because that might limit the sovereign's efforts to ensure peace and stability. For example, Hobbes argued that a ruthless sovereign might actually promote order because the people would be motivated by fear to obey the laws of the sovereign. Hobbes further argued that because the transfer of sovereignty was permanent, the right to revolt against the sovereign was nonexistent. In fact, any attempt to reform a government through disobedience (revolution) would be an injustice3 that would produce more harm than good. Better to suffer the excesses of an unjust king than to overthrow him and be left with anarchy.

The arguments Hobbes presented in Leviathan were radically original perspectives on the nature of man and the origins of government. Being in the employ of the monarchy, at least one motive behind Hobbes' writings was a desire to create a plausible defense of the monarchy. In defending the monarchy, however, Hobbes ultimately defended the absolute authority of the sovereign, monarch or not. It was an argument neither the people nor the king was comfortable with.

In his defense, Hobbes was fighting against insurmountable forces that would continue to weaken the monarchy until it was finally reduced to the figurehead role it occupies today. Even as he was writing Leviathan , the rising merchant class was growing ever wearier of the monarchy's abuses of power. Indeed, it was precisely because the monarchy was already losing its credibility that Hobbes was commissioned to write Leviathan .

By defending the monarchy in the manner he did, Hobbes unwittingly laid the groundwork for just the kind of popular revolts he decried in Leviathan . By claiming that individuals in the state of nature were the original source of sovereignty, and not God or kings, Hobbes created a doctrine on which others base compelling arguments for natural rights, popular government and revolution. One such man was John Locke.

John Locke (1632-1704), in his Second Treatise of Civil Government , declared that Hobbes' description of life before government was only half right. While the state of nature might be a state of war, Locke argued that it could just as easily be characterized by "peace, goodwill, mutual assistance, and preservation. While agreeing with Hobbes' that individuals in the state of nature would naturally and rationally come together to form a government, Locke argued that the contract people entered into with each other and the leaders of their new government was not permanent because the people did not unconditionally surrender their sovereignty to their leaders. Rather, Locke argued, individuals would grant authority to a government so long as it provided for the common good – protection from the dangers of the state of nature. Because life in the state of nature is fraught with peril, Locke wrote, man was:

. . . willing to quit a condition, which, however free, is full of fears and continual dangers: and it is not without reason, that he seeks out, and is willing to join in society with others, who are already united, or have a mind to unite, for the mutual preservation of their lives, liberties and estates, which I call by the general name, property.

In other words, Locke agreed with Hobbes that government was necessary to rescue humankind from the state of nature, but not because the state of nature was a horribly dangerous place to be escaped at all costs. In Locke's view, when the people agreed to become subject to governmental authority, not only did they expect their government to provide stability and order, but they also expected it to protect their rights and liberties. The purpose of government, then, was to provide enough protection of life, liberty, and property that individuals could enjoy them.

There are two significant implications of Locke's "essay concerning the true original extent and end of civil government" that are worth noting. First, by turning Hobbes' argument on its head, Locke argued that because the people were the source of government's power in the first instance, the people remained the source of governmental power even after it was established. The notion of popular sovereignty, that power was vested in the people, was lent greater intellectual credibility.

Second, if the people were the source of the government's authority, it followed that the government was accountable to the people. Consequently, political leaders were just as obligated to obey the laws of society as the people were. More importantly, Locke argued that the government could only legitimately exercise its authority so long as it protected the inalienable individual rights of the people. If government ever acted "contrary to their trust", the people were justified in taking action against it.

Today, Locke's writings are recognized as a source of some of the most important contributions to political philosophy. His emphasis on popular sovereignty and individual rights was groundbreaking. His influence on the Framers of the American Constitution was at least of equal significance. In his writings, Locke spoke of "life, liberty and property", a phrase which was modified only slightly by Thomas Jefferson when he wrote in the Declaration of Independence that: "We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness" (emphasis added). So profound is Locke's influence on American political thought that one author has called Locke the "massive national cliché" in America.

Locke's influence on the Founders is discussed at greater length in "The Constitutional Convention".

Hobbes, Locke, and the Social Contract

The 17th century was among the most chaotic and destructive the continent of Europe had ever witnessed in the modern era. From 1618-1648, much of Central Europe was caught in the throes of the Thirty Years War, the violent breakup of the Holy Roman Empire. The conflict marked by religious violence between Catholics and Protestants, shameless dynastic maneuvering, famine, disease, and other unimaginable atrocities, still ranks among one of the largest disasters to affect Europe to this day. England and Scotland also became engulfed in a civil conflict in this period between royalist supporters of the Stuart Dynasty and supporters of Parliamentary rights that had religious dimensions as well. Though the war only lasted approximately ten years, the instability it caused in the form of continuing guerilla warfare, famine, revolution, and intermittent rebellion lasted for the next few decades. These decades of suffering and instability produced by these wars raised many questions about human nature, civil society, and most importantly, how to structure government to effectively prevent further breakdowns in public order. This had the side effect of producing two of the brightest political minds in the English philosophical tradition: Thomas Hobbes (1588-1679) and John Locke (1632-1704). Hobbes and Locke each stood on fundamentally opposing corners in their debate on what made the most effective form of government for society. Hobbes was a proponent of Absolutism, a system which placed control of the state in the hands of a single individual, a monarch free from all forms of limitations or accountability. Locke, on the other hand, favored a more open approach to state-building. Locke believed that a government’s legitimacy came from the consent of the people they governed. Though their conclusions on what made an effective government wildly differed, their arguments had an enormous impact on the later philosophers of the Enlightenment era, including the Founding Fathers of the American Revolution.

Though Hobbes and Locke lived in roughly the same period and witnessed much of the same events, their careers took them on drastically different paths that had a drastic impact on their respective philosophies. Both men grew up in relatively undistinguished families that were still wealthy enough to give them extensive educations, but Hobbes’ father was an Anglican vicar while Locke grew up in a Puritan family. After receiving his doctorate, Hobbes became heavily associated with William Cavendish, who became King Charles I’s financier during the Civil War, and briefly became the future Charles II’s tutor in mathematics. This placed Hobbes firmly on the royalist side during the Civil War, and forced him to spend much of his career in exile after Charles I’s execution. Locke, on the other hand, was the son of a cavalry officer in fellow Puritan Oliver Cromwell’s New Model Army, placing him firmly on the Parliamentary side in the war. As an adult, Locke worked in medicine as well as parliamentary politics under the patronage of Anthony Ashley Cooper, known as Lord Ashley and one of the founders of the English Whig movement, which sought to continue the struggle against Absolute Monarchism after the 1660 Restoration of the Stuart Dynasty. Like Hobbes, Locke also briefly faced exile when he was suspected of insurrection in the years leading up to the Glorious Revolution, and so fled to the Netherlands. Clearly, both of these men were greatly influenced by the politics surrounding them, and it is easy to see their debate as a microcosm for a much greater political struggle. Examining the actual nuances of their reasoning, however, reveals a good deal of similarities between the two men.

Hobbes and Locke lay out their arguments with very similar structures, beginning with an exploration into the “State of Nature,” essentially the human condition before the development of civilization, to answer why people develop societies in the first place. For Hobbes, the State of Nature was a state of war, essentially a purely anarchic dog-eat-dog world where people constantly struggle over limited power and resources, a life which Hobbes described as “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short.” The act of forming a state, in Hobbes’ view, was therefore and effort to stem this cycle of violence, in which the population collectively put their faith in a stronger power than their own. There were two key influences on Hobbes in forming this view. The first was his own personal experiences during the English Civil War. In Hobbes’ view, the destruction and mayhem wrought by the Civil War outweighed any form of tyranny the Stuarts could bring to bear. The second was the Ancient Greek Historian Thucydides, whose work on the Peloponnesian War, a decades-long conflict between the city-states of Athens, Sparta, and their respective allies, Hobbes wrote the first English translation. Thucydides believed that states and individuals are ultimately rational actors that will act primarily on behalf of their own self-interest, no matter what higher ideals they claim to aspire to. For him, this meant that stronger actors naturally dominate weaker ones, summed up in one dialogue as, “the strong do what they can, and the weak suffer what they must.” Might makes right, in other words. This is the basis for what we now call Political Realism, and Hobbes viewed domestic politics through a very similar lens as Thucydides did on the international level, with some important differences though. Thucydides presented his Realist principles as a justification for Athenian Imperialism, but Hobbes takes a different approach. For Hobbes, people do not submit to a higher authority because it is naturally stronger than they are. Hobbes’ State of Nature is so chaotic precisely because people are essentially equal and will perform the same actions in their self-interest. Instead of a top-down subjugation, Hobbes saw the formation of a state as a collective approach in which people willingly and rationally gave up some of their freedoms in exchange for protection from the kind of anarchy he so dreaded. All of civilization, arts, engineering, letters, etc., was built on this fundamental premise. Therefore a proper government should be as adept at preventing social discord as possible, which meant not dividing the powers of the state divided among different branches, but united under the auspices of one person, the monarch. Hobbes’ philosophy is actually best summed up on the cover of his most famous treatise, The Leviathan , which shows a massive monarchical figure made up of the teeming subjects that have willingly submitted to his rule to keep the peace.

John Locke, naturally, took a very different stance. For Locke, the State of Nature was not of a state of war, but a state of freedom. In fact, it was a state of purest freedom, where people could act however they wished without restriction, but this created a paradox, as a world of absolute freedom created an environment in which the freedom of one individual could violate the natural rights of another. Locke believed that all people possess three fundamental rights: life, liberty, and property. He argued that these rights are both natural, meaning that originate in nature itself, as well as inalienable, meaning that they cannot be taken away, only violated. Locke also argued that individuals have a moral duty and rational interest to preserve their rights. Another problem Locke attributed to the State of Nature was a lack of impartial justice. When conflict arises between two parties regarding violations of their rights, Locke argued that neither one had the means to decisively resolve the situation peacefully, as both regarded their own position as the true and correct one and were too biased and personally invested to offer an objective viewpoint. Like Hobbes, Locke believed that people were ultimately rational actors who sought to avoid violent conflict wherever possible, and so in such a situation, opposing sides consented to allow a third party to mediate the case, let them deliver a verdict of their own, and agree to hold by that verdict. That, to Locke, is where the origins of government lie, not in the population agreeing to submit to a higher authority, but the population itself agreeing to a mediator that could guarantee the preservation of their natural rights and balance liberty and justice. This is why having the consent of the governed is of such great value for Locke because the government cannot fulfill its basic function if the population cannot agree to its formation in the first place.

In spite of their many differences, both Hobbes and Locke were both instrumental to the development of what we now call the Social Contract, the fundamental agreement underlying all of civil society. It is fair to say that today we live in Locke’s world rather than Hobbes, with a prevalent emphasis on the importance of human rights and representative government, but that is not to say that Hobbes has nothing of value to add either. After all, the people behind the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution showed a clear preference to Locke’s principles, but that could not stop a Civil War of their own down the line.

Further Reading

Leviathan By: Thomas Hobbes

Two Treatises of Government and A Letter Concerning Toleration By: John Locke

On the Social Contract By: Jean-Jacques Rousseau

Federalists, War Hawks & The War of 1812

Embargos: Economic Warfare on the Eve of the War of 1812

Fighting for Our Battlefields, and Our Planet

You may also like.

Thomas Hobbes Vs John Locke: The Battle of Political Philosophies

- Philosopher

Thomas Hobbes and John Locke had differing views on the nature of government and the rights of individuals. Hobbes believed in a strong, centralized government to maintain order and prevent chaos, while Locke argued for limited government and the protection of natural rights.

Credit: www.mackinac.org

Introduction To Thomas Hobbes And John Locke

Thomas Hobbes and John Locke were two prominent philosophers who had contrasting views on government and human nature. Hobbes believed in a strong central authority to prevent chaos, while Locke advocated for limited government and the protection of individual rights.

Their ideas continue to shape political theory and debate today.

Background Of Thomas Hobbes

Background of john locke.

Credit: study.com

Comparison Of Political Philosophies

When it comes to political philosophies, Thomas Hobbes and John Locke hold contrasting views that have significantly shaped Western political thought. Let’s delve into their philosophies and explore the differences between the two influential thinkers.

Concept Of State Of Nature

Hobbes and Locke both contemplated the hypothetical concept of the state of nature to understand the origins and nature of political societies.

Thomas Hobbes, in his seminal work “Leviathan,” defines the state of nature as a condition of perpetual and unending conflict. According to Hobbes, in the absence of government or authority, individuals live in a state of war where life is solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short. In this state, everyone has unlimited freedom, but this freedom inevitably leads to chaos and insecurity.

John Locke, on the other hand, offers a more optimistic perspective. In his “Two Treatises of Government,” Locke argues that the state of nature is characterized by reason and equality rather than constant conflict. He believes that people are generally peaceful and cooperative but acknowledges the need for governments to preserve natural rights and resolve disputes.

Role Of Government

Hobbes and Locke have differing opinions when it comes to the role and function of government in society.

According to Hobbes, the primary purpose of the government is to establish order and prevent the chaos of the state of nature. He argues that a strong and centralized authority, preferably an absolute monarchy, is necessary to maintain peace and security. Hobbes sees the power of the government as absolute and believes that individuals should surrender their rights to the sovereign in exchange for protection.

Contrary to Hobbes, Locke advocates for a limited government with clearly defined boundaries. He argues that the role of the government is to protect the natural rights of individuals, which include life, liberty, and property. Locke emphasizes the consent of the governed and the importance of a social contract between the government and the people. He believes that if the government fails to fulfill its obligations, the people have the right to rebel and establish a new government.

Views On Individual Rights

Both Hobbes and Locke have divergent viewpoints regarding individual rights and the extent of government interference.

Hobbes considers individual rights as subordinate to the authority of the government. He believes that individuals should surrender their rights in order to preserve peace and secure their own survival. In the absence of government, Hobbes argues, there is no protection of rights and life becomes precarious.

Locke, however, holds a different perspective. He asserts that individuals possess natural rights that are inherent and cannot be taken away by any external authority. These natural rights, including life, liberty, and property, are fundamental and should be protected by the government. Locke believes that any government that violates these rights lacks legitimacy and should be overthrown.

In conclusion, Thomas Hobbes and John Locke offer contrasting political philosophies, particularly in their views on the state of nature, role of government, and individual rights. While Hobbes emphasizes the need for an absolute authority to maintain order and secure survival, Locke advocates for limited government that safeguards individual rights. Understanding their divergent perspectives is crucial to comprehend the foundations of modern political thought.

Impact And Legacy

The impact and legacy of Thomas Hobbes and John Locke, two philosophers compared, have shaped the political theories of limited government and social contract. Hobbes emphasizes the need for a strong central authority, while Locke advocates for individual rights and the consent of the governed.

Their contrasting ideas continue to influence political discourse and shape our understanding of governance.

Influence On Enlightenment Thinkers

Relevance in contemporary politics.

Frequently Asked Questions For Thomas Hobbes Vs John Locke

What was john locke’s main philosophy.

John Locke’s main philosophy is the concept of limited government and natural rights. He argued that governments have responsibilities to citizens, limited powers, and can be overthrown by citizens in certain circumstances.

What Did Thomas Hobbes And John Locke Based Their Ideas About Government On During The Enlightenment?

Thomas Hobbes and John Locke based their ideas about government on observations of human nature and the natural state of humans. They developed the social contract theory, which argues that governments have obligations to their citizens and can be overthrown under certain circumstances.

What Is The Difference Between Locke And Rousseau?

Locke and Rousseau differ in their views on government. Locke believes in limited government, with obligations to citizens and limited powers, while Rousseau refuses to let individual freedom be taken away unless done by the majority of the people.

How Does Hobbes Define The State Of Nature?

Hobbes defines the state of nature as a chaotic existence where everyone is self-interested and there is no cooperation. In this state, competition is extreme and there is no concern for others. Unlimited freedom leads to chaos and conflict.

Thomas Hobbes and John Locke were two influential philosophers with contrasting views on government and human nature. Hobbes believed in a strong, authoritarian government to maintain order and prevent chaos. On the other hand, Locke argued for a limited government that respected individual rights and freedoms.

While their ideas differed, both philosophers contributed to the development of political philosophy and the concept of the social contract. Understanding their contrasting perspectives allows us to appreciate the complexities of governance and the diverse interpretations of human nature.

Related Post

Thomas hobbes on social contract: unlocking the power of collective agreement, thomas hobbes leviathan pdf: unlocking the power of political philosophy, what is virtue according to aristotle: unlocking the wisdom, where did john calvin live tracing his footsteps, leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Recent Post

Should felons be allowed to vote debunking the myths, who got voted off of dancing with the stars tonight: shocking elimination revealed, what is a roll call vote unlocking the significance and impact, qué enfermedad es cuando votas sangre por la boca: descúbrelo aquí, who got voted off of dwts tonight: shocking elimination unveiled, can felons vote in texas discover the power of restored voting rights.

Our passion lies in making the complex and fascinating world of political science accessible to learners of all levels, fostering a deep understanding of political dynamics, governance, and global affairs.

© 2023 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED BY - PoliticalScienceGuru

By joining our mailing list, you’re not just subscribing to a newsletter; you’re becoming part of the PoliticalScienceGuru.com family.

- Table of Contents

- Random Entry

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Advanced Tools

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Entry Contents

Bibliography

Academic tools.

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

Hobbes’s Moral and Political Philosophy

The 17 th Century English philosopher Thomas Hobbes is now widely regarded as one of a handful of truly great political philosophers, whose masterwork Leviathan rivals in significance the political writings of Plato, Aristotle, Locke, Rousseau, Kant, and Rawls. Hobbes is famous for his early and elaborate development of what has come to be known as “social contract theory”, the method of justifying political principles or arrangements by appeal to the agreement that would be made among suitably situated rational, free, and equal persons. He is infamous for having used the social contract method to arrive at the astonishing conclusion that we ought to submit to the authority of an absolute—undivided and unlimited—sovereign power. While his methodological innovation had a profound constructive impact on subsequent work in political philosophy, his substantive conclusions have served mostly as a foil for the development of more palatable philosophical positions. Hobbes’s moral philosophy has been less influential than his political philosophy, in part because that theory is too ambiguous to have garnered any general consensus as to its content. Most scholars have taken Hobbes to have affirmed some sort of personal relativism or subjectivism; but views that Hobbes espoused divine command theory, virtue ethics, rule egoism, or a form of projectivism also find support in Hobbes’s texts and among scholars. Because Hobbes held that “the true doctrine of the Lawes of Nature is the true Morall philosophie”, differences in interpretation of Hobbes’s moral philosophy can be traced to differing understandings of the status and operation of Hobbes’s “laws of nature”, which laws will be discussed below. The formerly dominant view that Hobbes espoused psychological egoism as the foundation of his moral theory is currently widely rejected, and there has been to date no fully systematic study of Hobbes’s moral psychology.

1. Major Political Writings

2. the philosophical project, 3. the state of nature, 4. the state of nature is a state of war, 5. further questions about the state of nature, 6. the laws of nature, 7. establishing sovereign authority, 8. absolutism, 9. responsibility and the limits of political obligation, 10. religion and social instability, 11. hobbes on gender and race, collections, books and articles, other internet resources, related entries.

Hobbes wrote several versions of his political philosophy, including The Elements of Law, Natural and Politic (also under the titles Human Nature and De Corpore Politico) published in 1650, De Cive (1642) published in English as Philosophical Rudiments Concerning Government and Society in 1651, the English Leviathan published in 1651, and its Latin revision in 1668. Others of his works are also important in understanding his political philosophy, especially his history of the English Civil War, Behemoth (published 1679), De Corpore (1655), De Homine (1658), Dialogue Between a Philosopher and a Student of the Common Laws of England (1681), and The Questions Concerning Liberty, Necessity, and Chance (1656). All of Hobbes’s major writings are collected in The English Works of Thomas Hobbes , edited by Sir William Molesworth (11 volumes, London 1839–45), and Thomae Hobbes Opera Philosophica Quae Latina Scripsit Omnia , also edited by Molesworth (5 volumes; London, 1839–45). Oxford University Press has undertaken a projected 26 volume collection of the Clarendon Edition of the Works of Thomas Hobbes . So far 3 volumes are available: De Cive (edited by Howard Warrender), The Correspondence of Thomas Hobbes (edited by Noel Malcolm), and Writings on Common Law and Hereditary Right (edited by Alan Cromartie and Quentin Skinner). Recently Noel Malcolm has published a three volume edition of Leviathan , which places the English text side by side with Hobbes’s later Latin version of it. Readers new to Hobbes should begin with Leviathan , being sure to read Parts Three and Four, as well as the more familiar and often excerpted Parts One and Two. There are many fine overviews of Hobbes’s normative philosophy, some of which are listed in the following selected bibliography of secondary works.

Hobbes sought to discover rational principles for the construction of a civil polity that would not be subject to destruction from within. Having lived through the period of political disintegration culminating in the English Civil War, he came to the view that the burdens of even the most oppressive government are “scarce sensible, in respect of the miseries, and horrible calamities, that accompany a Civill Warre”. Because virtually any government would be better than a civil war, and, according to Hobbes’s analysis, all but absolute governments are systematically prone to dissolution into civil war, people ought to submit themselves to an absolute political authority. Continued stability will require that they also refrain from the sorts of actions that might undermine such a regime. For example, subjects should not dispute the sovereign power and under no circumstances should they rebel. In general, Hobbes aimed to demonstrate the reciprocal relationship between political obedience and peace.

To establish these conclusions, Hobbes invites us to consider what life would be like in a state of nature, that is, a condition without government. Perhaps we would imagine that people might fare best in such a state, where each decides for herself how to act, and is judge, jury and executioner in her own case whenever disputes arise—and that at any rate, this state is the appropriate baseline against which to judge the justifiability of political arrangements. Hobbes terms this situation “the condition of mere nature”, a state of perfectly private judgment, in which there is no agency with recognized authority to arbitrate disputes and effective power to enforce its decisions.

Hobbes’s near descendant, John Locke, insisted in his Second Treatise of Government that the state of nature was indeed to be preferred to subjection to the arbitrary power of an absolute sovereign. But Hobbes famously argued that such a “dissolute condition of masterlesse men, without subjection to Lawes, and a coercive Power to tye their hands from rapine, and revenge” would make impossible all of the basic security upon which comfortable, sociable, civilized life depends. There would be “no place for industry, because the fruit thereof is uncertain; and consequently no culture of the earth; no navigation, nor use of the commodities that may be imported by Sea; no commodious Building; no Instruments of moving and removing such things as require much force; no Knowledge of the face of the Earth; no account of Time; no Arts; no Letters; and which is worst of all, continuall feare, and danger of violent death; And the life of man, solitary, poore, nasty, brutish, and short.” If this is the state of nature, people have strong reasons to avoid it, which can be done only by submitting to some mutually recognized public authority, for “so long a man is in the condition of mere nature, (which is a condition of war,) as private appetite is the measure of good and evill.”

Although many readers have criticized Hobbes’s state of nature as unduly pessimistic, he constructs it from a number of individually plausible empirical and normative assumptions. He assumes that people are sufficiently similar in their mental and physical attributes that no one is invulnerable nor can expect to be able to dominate the others. Hobbes assumes that people generally “shun death”, and that the desire to preserve their own lives is very strong in most people. While people have local affections, their benevolence is limited, and they have a tendency to partiality. Concerned that others should agree with their own high opinions of themselves, people are sensitive to slights. They make evaluative judgments, but often use seemingly impersonal terms like ‘good’ and ‘bad’ to stand for their own personal preferences. They are curious about the causes of events, and anxious about their futures; according to Hobbes, these characteristics incline people to adopt religious beliefs, although the content of those beliefs will differ depending upon the sort of religious education one has happened to receive.

With respect to normative assumptions, Hobbes ascribes to each person in the state of nature a liberty right to preserve herself, which he terms “the right of nature”. This is the right to do whatever one sincerely judges needful for one’s preservation; yet because it is at least possible that virtually anything might be judged necessary for one’s preservation, this theoretically limited right of nature becomes in practice an unlimited right to potentially anything, or, as Hobbes puts it, a right “to all things”. Hobbes further assumes as a principle of practical rationality, that people should adopt what they see to be the necessary means to their most important ends.

Taken together, these plausible descriptive and normative assumptions yield a state of nature potentially fraught with divisive struggle. The right of each to all things invites serious conflict, especially if there is competition for resources, as there will surely be over at least scarce goods such as the most desirable lands, spouses, etc. People will quite naturally fear that others may (citing the right of nature) invade them, and may rationally plan to strike first as an anticipatory defense. Moreover, that minority of prideful or “vain-glorious” persons who take pleasure in exercising power over others will naturally elicit preemptive defensive responses from others. Conflict will be further fueled by disagreement in religious views, in moral judgments, and over matters as mundane as what goods one actually needs, and what respect one properly merits. Hobbes imagines a state of nature in which each person is free to decide for herself what she needs, what she’s owed, what’s respectful, right, pious, prudent, and also free to decide all of these questions for the behavior of everyone else as well, and to act on her judgments as she thinks best, enforcing her views where she can. In this situation where there is no common authority to resolve these many and serious disputes, we can easily imagine with Hobbes that the state of nature would become a “state of war”, even worse, a war of “all against all”.

In response to the natural question whether humanity ever was generally in any such state of nature, Hobbes gives three examples of putative states of nature. First, he notes that all sovereigns are in this state with respect to one another. This claim has made Hobbes the representative example of a “realist” in international relations. Second, he opined that many now civilized peoples were formerly in that state, and some few peoples—“the savage people in many places of America” ( Leviathan , XIII), for instance—were still to his day in the state of nature. Third and most significantly, Hobbes asserts that the state of nature will be easily recognized by those whose formerly peaceful states have collapsed into civil war. While the state of nature’s condition of perfectly private judgment is an abstraction, something resembling it too closely for comfort remains a perpetually present possibility, to be feared, and avoided.

Do the other assumptions of Hobbes’s philosophy license the existence of this imagined state of isolated individuals pursuing their private judgments? Probably not, since, as feminist critics among others have noted, children are by Hobbes’s theory assumed to have undertaken an obligation of obedience to their parents in exchange for nurturing, and so the primitive units in the state of nature will include families ordered by internal obligations, as well as individuals. The bonds of affection, sexual affinity, and friendship—as well as of clan membership and shared religious belief—may further decrease the accuracy of any purely individualistic model of the state of nature. This concession need not impugn Hobbes’s analysis of conflict in the state of nature, since it may turn out that competition, diffidence and glory-seeking are disastrous sources of conflicts among small groups just as much as they are among individuals. Still, commentators seeking to answer the question how precisely we should understand Hobbes’s state of nature are investigating the degree to which Hobbes imagines that to be a condition of interaction among isolated individuals.

Another important open question is that of what, exactly, it is about human beings that makes it the case (supposing Hobbes is right) that our communal life is prone to disaster when we are left to interact according only to our own individual judgments. Perhaps, while people do wish to act for their own best long-term interest, they are shortsighted, and so indulge their current interests without properly considering the effects of their current behavior on their long-term interest. This would be a type of failure of rationality. Alternatively, it may be that people in the state of nature are fully rational, but are trapped in a situation that makes it individually rational for each to act in a way that is sub-optimal for all, perhaps finding themselves in the familiar ‘prisoner’s dilemma’ of game theory. Or again, it may be that Hobbes’s state of nature would be peaceful but for the presence of persons (just a few, or perhaps all, to some degree) whose passions overrule their calmer judgments; who are prideful, spiteful, partial, envious, jealous, and in other ways prone to behave in ways that lead to war. Such an account would understand irrational human passions to be the source of conflict. Which, if any, of these accounts adequately answers to Hobbes’s text is a matter of continuing debate among Hobbes scholars. Game theorists have been particularly active in these debates, experimenting with different models for the state of nature and the conflict it engenders.

Hobbes argues that the state of nature is a miserable state of war in which none of our important human ends are reliably realizable. Happily, human nature also provides resources to escape this miserable condition. Hobbes argues that each of us, as a rational being, can see that a war of all against all is inimical to the satisfaction of her interests, and so can agree that “peace is good, and therefore also the way or means of peace are good”. Humans will recognize as imperatives the injunction to seek peace, and to do those things necessary to secure it, when they can do so safely. Hobbes calls these practical imperatives “Lawes of Nature”, the sum of which is not to treat others in ways we would not have them treat us. These “precepts”, “conclusions” or “theorems” of reason are “eternal and immutable”, always commanding our assent even when they may not safely be acted upon. They forbid many familiar vices such as iniquity, cruelty, and ingratitude. Although commentators do not agree on whether these laws should be regarded as mere precepts of prudence, or rather as divine commands, or moral imperatives of some other sort, all agree that Hobbes understands them to direct people to submit to political authority. They tell us to seek peace with willing others by laying down part of our “right to all things”, by mutually covenanting to submit to the authority of a sovereign, and further direct us to keep that covenant establishing sovereignty.

When people mutually covenant each to the others to obey a common authority, they have established what Hobbes calls “sovereignty by institution”. When, threatened by a conqueror, they covenant for protection by promising obedience, they have established “sovereignty by acquisition”. These are equally legitimate ways of establishing sovereignty, according to Hobbes, and their underlying motivation is the same—namely fear—whether of one’s fellows or of a conqueror. The social covenant involves both the renunciation or transfer of right and the authorization of the sovereign power. Political legitimacy depends not on how a government came to power, but only on whether it can effectively protect those who have consented to obey it; political obligation ends when protection ceases.

Although Hobbes offered some mild pragmatic grounds for preferring monarchy to other forms of government, his main concern was to argue that effective government—whatever its form—must have absolute authority. Its powers must be neither divided nor limited. The powers of legislation, adjudication, enforcement, taxation, war-making (and the less familiar right of control of normative doctrine) are connected in such a way that a loss of one may thwart effective exercise of the rest; for example, legislation without interpretation and enforcement will not serve to regulate conduct. Only a government that possesses all of what Hobbes terms the “essential rights of sovereignty” can be reliably effective, since where partial sets of these rights are held by different bodies that disagree in their judgments as to what is to be done, paralysis of effective government, or degeneration into a civil war to settle their dispute, may occur.

Similarly, to impose limitation on the authority of the government is to invite irresoluble disputes over whether it has overstepped those limits. If each person is to decide for herself whether the government should be obeyed, factional disagreement—and war to settle the issue, or at least paralysis of effective government—are quite possible. To refer resolution of the question to some further authority, itself also limited and so open to challenge for overstepping its bounds, would be to initiate an infinite regress of non-authoritative ‘authorities’ (where the buck never stops). To refer it to a further authority itself unlimited, would be just to relocate the seat of absolute sovereignty, a position entirely consistent with Hobbes’s insistence on absolutism. To avoid the horrible prospect of governmental collapse and return to the state of nature, people should treat their sovereign as having absolute authority.

When subjects institute a sovereign by authorizing it, they agree, in conformity with the principle “no wrong is done to a consenting party”, not to hold it liable for any errors in judgment it may make and not to treat any harms it does to them as actionable injustices. Although many interpreters have assumed that by authorizing a sovereign, subjects become morally responsible for the actions it commands, Hobbes instead insists that “the external actions done in obedience to [laws], without the inward approbation, are the actions of the sovereign, and not of the subject, which is in that case but as an instrument, without any motion of his own at all” (Leviathan xlii, 106). It may be important to Hobbes’s project of persuading his Christian readers to obey their sovereign that he can reassure them that God will not hold them responsible for wrongful actions done at the sovereign’s command, because they cannot reasonably be expected to obey if doing so would jeopardize their eternal prospects. Hence Hobbes explains that “whatsoever a subject...is compelled to do in obedience to his sovereign, and doth it not in order to his own mind, but in order to the laws of his country, that action is not his, but his sovereign’s.” (Leviathan xlii. 11) This position reinforces absolutism by permitting Hobbes to maintain that subjects can obey even commands to perform actions they believe to be sinful without fear of divine punishment.

Hobbes’s description of the way in which persons should be understood to become subjects to a sovereign authority changes from his Elements and De Cive accounts to his Leviathan account. In the former, each person lays down their rights (of self-government and to pursue all things they judge useful or necessary for their survival and commodious living) in favor of one and the same sovereign person (whether a natural person, as a monarch, or an artificial person, as a rule-governed assembly). In these earlier accounts, sovereigns alone retain their right of nature to act on their own private judgment in all matters, and also exercise the transferred rights of subjects. Whether exercising its own retained right of nature or the subjects’ transferred rights, the sovereign’s action is attributable to the sovereign itself, and it bears moral responsibility for it. In contrast, Hobbes’s Leviathan account has each individual covenanting to “own and authorize” all of the sovereign’s actions—whatever the sovereign does as a public figure or commands that subjects do. This change creates an apparent inconsistency in Hobbes’s theory of responsibility for actions done at the sovereign’s command; if in “owning and authorizing” all their sovereign’s actions, subjects become morally responsible for all that it does and all they do in obedience to its commands, Hobbes cannot consistently maintain his position that merely obedient actions in response to sovereign commands are the moral responsibility of the sovereign alone. One resolution of this apparent inconsistency denies that Hobbes’s idea of authorization carries along responsibility for the act authorized, as our contemporary idea of authorization generally does.

While Hobbes insists that we should regard our governments as having absolute authority, he reserves to subjects the liberty of disobeying some of their government’s commands. He argues that subjects retain a right of self-defense against the sovereign power, giving them the right to disobey or resist when their lives are in danger. He also gives them seemingly broad resistance rights in cases in which their families or even their honor are at stake. These exceptions have understandably intrigued those who study Hobbes. His ascription of apparently inalienable rights—what he calls the “true liberties of subjects”—seems incompatible with his defense of absolute sovereignty. Moreover, if the sovereign’s failure to provide adequate protection to subjects extinguishes their obligation to obey, and if it is left to each subject to judge for herself the adequacy of that protection, it seems that people have never really exited the fearsome state of nature. This aspect of Hobbes’s political philosophy has been hotly debated ever since Hobbes’s time. Bishop Bramhall, one of Hobbes’s contemporaries, famously accused Leviathan of being a “Rebell’s Catechism.” More recently, some commentators have argued that Hobbes’s discussion of the limits of political obligation is the Achilles’ heel of his theory. It is not clear whether or not this charge can stand up to scrutiny, but it will surely be the subject of much continued discussion.

The last crucial aspect of Hobbes’s political philosophy is his treatment of religion. Hobbes progressively expands his discussion of Christian religion in each revision of his political philosophy, until it comes in Leviathan to comprise roughly half the book. There is no settled consensus on how Hobbes understands the significance of religion within his political theory. Some commentators have argued that Hobbes is trying to demonstrate to his readers the compatibility of his political theory with core Christian commitments, since it may seem that Christians’ religious duties forbid their affording the sort of absolute obedience to their governors which Hobbes’s theory requires of them. Others have doubted the sincerity of his professed Christianity, arguing that by the use of irony or other subtle rhetorical devices, Hobbes sought to undermine his readers’ religious beliefs. Howsoever his intentions are properly understood, Hobbes’s obvious concern with the power of religious belief is a fact that interpreters of his political philosophy must seek to explain.

Scholars are increasingly interested in how Hobbes thought of the status of women, and of the family. Hobbes was one of the earliest western philosophers to count women as persons when devising a social contract among persons. He insists on the equality of all people, very explicitly including women. People are equal because they are all subject to domination, and all potentially capable of dominating others. No person is so strong as to be invulnerable to attack while sleeping by the concerted efforts of others, nor is any so strong as to be assured of dominating all others.

In this relevant sense, women are naturally equal to men. They are equally naturally free, meaning that their consent is required before they will be under the authority of anyone else. In this, Hobbes’s claims stand in stark contrast to many prevailing views of the time, according to which women were born inferior to and subordinate to men. Sir Robert Filmer, who later served as the target of John Locke’s First Treatise of Government , is a well-known proponent of this view, which he calls patriarchalism. Explicitly rejecting the patriarchalist view as well as Salic law, Hobbes maintains that women can be sovereigns; authority for him is “neither male nor female”. He also argues for natural maternal right: in the state of nature, dominion over children naturally belongs to the mother. He adduced the example of the Amazon warrior women as evidence.

In seeming contrast to this egalitarian foundation, Hobbes spoke of the commonwealth in patriarchal language. In the move from the state of nature to civil society, families are described as “fathers”, “servants”, and “children”, seemingly obliterating mothers from the picture entirely. Hobbes justifies this way of talking by saying that it is fathers not mothers who have founded societies. As true as that is, it is easy to see how there is a lively debate between those who emphasize the potentially feminist or egalitarian aspects of Hobbes’s thought and those who emphasize his ultimate exclusion of women. Such debates raise the question: To what extent are the patriarchal claims Hobbes makes integral to his overall theory, if indeed they are integral at all?

We find similar ambiguities and tensions in what Hobbes says about race (or what we would now call race). On the one hand, he invokes the “savages” of the Americas to illustrate the “brutish” conditions of life in the state of nature. On the other hand, when he simply denies that there are innate or immutable differences between Native Americans and Europeans. Societies which have enjoyed scientific advancement have done so, according to Hobbes, because of the existence of “leisure time,” and if that is “supposed away,” he asks rhetorically, “what do we differ from the wildest of the Indians?”

The secondary literature on Hobbes’s moral and political philosophy (not to speak of his entire body of work) is vast, appearing across many disciplines and in many languages. The following is a narrow selection of fairly recent works by philosophers, political theorists, and intellectual historians, available in English, on main areas of inquiry in Hobbes’s moral and political thought. Very helpful for further reference is the critical bibliography of Hobbes scholarship to 1990 contained in Zagorin, P., 1990, “Hobbes on Our Mind”, Journal of the History of Ideas , 51(2).

- Hobbes Studies is an annually published journal devoted to scholarly research on all aspects of Hobbes’s work.

- Brown, K.C. (ed.), 1965, Hobbes Studies , Cambridge: Harvard University Press, contains important papers by A.E. Taylor, J.W. N. Watkins, Howard Warrender, and John Plamenatz, among others.

- Caws, P. (ed.), 1989, The Causes of Quarrell: Essays on Peace, War, and Thomas Hobbes , Boston: Beacon Press.

- Courtland, S. (ed.), 2017, Hobbesian Applied Ethics and Public Policy , New York: Routledge.

- Dietz, M. (ed.), 1990, Thomas Hobbes and Political Theory , Lawrence: University of Kansas Press.

- Dyzenhaus, D. and T. Poole (eds.), 2013, Hobbes and the Law , Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Douglass, R. and J. Olsthoorn (eds.), 2019, Hobbes's On the Citizen: A Critical Guide , Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Finkelstein, C. (ed.), 2005, Hobbes on Law , Aldershot: Ashgate.

- Hirschmann, N. and J. Wright (eds.), 2012, Feminist Interpretations of Thomas Hobbes , University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press.

- Lloyd, S.A. (ed.), 2012, Hobbes Today: Insights for the 21st Century , Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- –––, 2013, The Bloomsbury Companion to Hobbes , London: Bloomsbury.

- –––, 2019, Interpretations of Hobbes’ Political Theory , Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Lloyd, S.A. (ed.), 2001, “Special Issue on Recent Work on the Moral and Political Philosophy of Thomas Hobbes”, Pacific Philosophical Quarterly , 82 (3&4).

- Martinich, A.P. and Kinch Hoekstra (eds.), 2016, The Oxford Handbook of Hobbes , Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Odzuck, E. and A. Chadwick (eds.), 2020, Feminist Perspectives on Hobbes , special issue of Hobbes Studies .

- Rogers, G.A.J. and A. Ryan (eds.), 1988, Perspectives on Thomas Hobbes , Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Rogers, G.A.J. (ed.), 1995, Leviathan: Contemporary Responses to the Political Theory of Thomas Hobbes , Bristol: Thoemmes Press.

- Rogers, G.A.J. and T. Sorell (eds.), 2000, Hobbes and History . London: Routledge.

- Shaver, R. (ed.), 1999, Hobbes , Hanover: Dartmouth Press.

- Sorell, T. (ed.), 1996, The Cambridge Companion to Hobbes Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Sorell, T., and L. Foisneau (eds.), 2004, Leviathan after 350 years , Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Sorell, T. and G.A.J. Rogers (eds.), 2000, Hobbes and History , London: Routledge.

- Springborg, P. (ed.), 2007, The Cambridge Companion to Hobbes’s Leviathan , Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Abizadeh, A., 2011, “Hobbes on the Causes of War: A Disagreement Theory”, American Political Science Review , 105 (2): 298–315.

- –––, 2018, Hobbes and the Two Faces of Ethics , Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Armitage, D., 2007, “Hobbes and the foundations of modern international thought”, in Rethinking the Foundations of Modern Political Thought , Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Ashcraft, R., 1971, “Hobbes’s Natural Man: A Study in Ideology Formation”, Journal of Politics , 33: 1076–1117.

- –––, 2010, “Slavery Discourse before the Restoration: The Barbary Coast, Justinian’s Digest, and Hobbes’s Political Theory”, History of European Ideas , 36 (2): 412–418.

- Baumgold, D., 1988, Hobbes’s Political Thought , Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Bejan, T.M., 2010, “Teaching the Leviathan: Thomas Hobbes on Education”, Oxford Review of Education , 36(5): 607–626.

- –––, 2016, “Difference without Disagreement: Rethinking Hobbes on ‘Independency’ and Toleration”, The Review of Politics , 78(1): 1–25.

- –––, forthcoming, “Hobbes Against Hate Speech”, British Journal for the History of Philosophy , first online: 03 Feb 2022. doi:10.1080/09608788.2022.2027340.

- Baumgold, D., 2013, “Trust in Hobbes’s Political Thought”, Political Theory , 41(6): 835–55.

- Benhabib, S., 2022, “Thomas Hobbes on My Mind: Leviathan, Thomas Hobbes”, Social Research: An International Quarterly , 89(2): 233–247.

- Bobier, C., 2020, “Rethinking Thomas Hobbes on the Passions”, Pacific Philosophical Quarterly , 101(4): 582–602.

- Bobbio, N., 1993, Thomas Hobbes and the Natural Law Tradition , Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Boonin-Vail, D., 1994, Thomas Hobbes and the Science of Moral Virtue , Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Boucher, D., 2018, Appropriating Hobbes: Legacies in Political, Legal, and International Thought , Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Byron, M., 2015, Submission and Subjection in Leviathan: Good Subjects in the Hobbbesian Commonwealth , Basingstoke, New York: Palgrave MacMillan.

- Collins, J., 2005, The Allegiance of Thomas Hobbes , Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Curley, E., 1988, “I durst not write so boldly: or how to read Hobbes’ theological-political treatise”, E. Giancotti (ed.), Proceedings of the Conference on Hobbes and Spinoza , Urbino.

- –––, 1994, “Introduction to Hobbes’s Leviathan ”, Leviathan with selected variants from the Latin edition of 1668, E. Curley (ed.), Indianapolis: Indiana University Press.

- Curran, E., 2006, “Can Rights Curb the Hobbesian Sovereign? The Full Right to Self-preservation, Duties of Sovereignty and the Limitations of Hohfeld”, Law and Philosophy , 25: 243–265.

- –––, 2007, Reclaiming the Rights of Hobbesian Subjects , Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan.

- –––, 2013, “An Immodest Proposal: Hobbes Rather than Locke Provides a Forerunner for Modern Rights Theory”, Law and Philosophy , 32 (4): 515–538.

- Darwall, S., 1995. The British Moralists and the Internal ‘Ought’, 1640–1740 , Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

- ––– 2000, “Normativity and Projection in Hobbes’s Leviathan ”, The Philosophical Review , 109 (3): 313–347.

- Ewin, R.E., 1991, Virtues and Rights: The Moral Philosophy of Thomas Hobbes , Boulder: Westview Press.

- Finn, S., 2006, Thomas Hobbes and the Politics of Natural Philosophy , London: Continuum Press.

- Field, S.L., 2020, Potentia: Hobbes and Spinoza on Power and Popular Politics , Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Flathman, R., 1993, Thomas Hobbes: Skepticism, Individuality, and Chastened Politics , Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

- Garofalo, P., 2021, “Psychology and Obligation in Hobbes: The Case of Ought Implies Can”, Hobbes Studies , 34(1): 146–171.

- Gauthier, D., 1969, The Logic of ‘Leviathan’: The Moral and political Theory of Thomas Hobbes , Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Gert, B., 1967, “Hobbes and Psychological Egoism”, Journal of the History of Ideas , 28: 503–520.

- ––– 1978, “Introduction to Man and Citizen”, Man and Citizen , B. Gert, (ed.), New York: Humanities Press.

- ––– 1988, “The Law of Nature and the Moral Law”, Hobbes Studies , 1: 26–44.

- Goldsmith, M. M., 1966, Hobbes’s Science of Politics , New York: Columbia University Press.

- Gray, M., 2010, “Feminist Interpretations of Thomas Hobbes: A Response to Carole Pateman and Susan Okin”, CEU Political Science Journal , 1(1): 1–29.

- Green, M., 2015, “Authorization and Political Authority in Hobbes”, Journal of the History of Philosophy , 62(3): 25–47.

- Hall, B., 2005, “Hobbes on Race” in Race and Racism in Modern Philosophy , Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Hampton, J., 1986, Hobbes and the Social Contract Tradition , Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Herbert, G., 1989, Thomas Hobbes: The Unity of Scientific and Moral Wisdom , Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press.

- Hoekstra, K., 1999, “Nothing to Declare: Hobbes and the Advocate of Injustice”, Political Theory , 27 (2): 230–235.

- –––, 2003, “Hobbes on Law, Nature and Reason”, Journal of the History of Philosophy , 41 (1): 111–120.

- –––, 2006, “The End of Philosophy”, Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society , 106: 25–62.

- –––, 2007, “A Lion in the House: Hobbes and Democracy” in Rethinking the Foundations of Modern Political Thought , Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- –––, 2013, “Early Modern Absolutism and Constitutionalism”, Cardozo Law Review , 34 (3): 1079–1098.

- Holden, T., 2018, “Hobbes on the Authority of Scripture”, Oxford Studies in Early Modern Philosophy , 8: 68–95.

- Hood, E.C., 1964. The Divine Politics of Thomas Hobbes , Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Johnston, D., 1986, The Rhetoric of ‘Leviathan’: Thomas Hobbes and the Politics of Cultural Transformation , Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Kapust, Daniel J. and Brandon P. Turner, 2013, “Democratical Gentlemen and the Lust for Mastery: Status, Ambition, and the Language of Liberty in Hobbes’s Political Thought”, Political Theory , 41 (4): 648–675.

- Kavka, G., 1986, Hobbesian Moral and Political Theory , Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Koganzon, R., 2015, “The Hostile Family and the Purpose of the ‘Natural Kingdom’ in Hobbes's Political Thought”, The Review of Politics , 77(3): 377–398.

- Kramer, M., 1997, Hobbes and the Paradox of Political Origins , New York: St. Martin’s Press.

- Krom, M., 2011, The Limits of Reason in Hobbes’s Commonwealth , New York: Continuum Press.

- LeBuffe, M., 2003, “Hobbes on the Origin of Obligation”, British Journal for the History of Philosophy , 11 (1): 15–39.

- Lloyd, S.A., 1992, Ideals as Interests in Hobbes’s ‘Leviathan’: the Power of Mind over Matter , Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- –––, 1998, “Contemporary Uses of Hobbes’s political philosophy”, in Rational Commitment and Social Justice: Essays for Gregory Kavka , J. Coleman and C. Morris (eds.), Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- –––, 2009, Morality in the Philosophy of Thomas Hobbes: Cases in the Law of Nature , Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- –––, 2016, “Authorization and Moral Responsibility in the Philosophy of Hobbes”, Hobbes Studies , 29: 169–88.

- –––, 2017, “Duty Without Obligation”, Hobbes Studies , 30: 202–221.

- –––, 2022, “Hobbes’s Theory of Responsibility as Support for Sommerville’s Argument Against Hobbes’s Approval of Independency”, Hobbes Studies , 35(1): 51–66.

- Lott, T., 2002, “Patriarchy and Slavery in Hobbes’s Political Philosophy” in Philosophers on Race: Critical Essays , pp. 63–80.

- Luban, D., 2018, “Hobbesian Slavery”, Political Theory , 46(5): 726–748.

- Macpherson, C.B., 1962, The Political Theory of Possessive Individualism: Hobbes to Locke , Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- –––, 1968, “Introduction”, Leviathan , C.B. Macpherson (ed.), London: Penguin.

- Malcolm, N., 2002, Aspects of Hobbes , Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Martel, J., 2007, Subverting the Leviathan: Reading Thomas Hobbes as a Radical Democrat , New York: Columbia University Press.

- Martinich, A.P., 1992, The Two Gods of Leviathan: Thomas Hobbes on Religion and Politics , Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- –––, 1995, A Hobbes Dictionary , Oxford: Blackwell.

- –––, 1999, Hobbes: A Biography , Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- –––, 2005, Hobbes , New York: Routledge.

- –––, 2011, “The Sovereign in the Political Thought of Hanfeizi and Thomas Hobbes”, Journal of Chinese Philosophy , 38 (1): 64–72.

- –––, 2021, Hobbes’s Political Philosophy: Interpretation and Interpretations , Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- May, L., 2013, Limiting Leviathan: Hobbes on Law and International Affairs , Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- McClure, C.S., 2013, “War, Madness, and Death: The Paradox of Honor in Hobbes’s Leviathan”, The Journal of Politics , 76 (1): 114–125.

- Moehler, M., 2009, “Why Hobbes’ State of Nature is Best Modeled by an Assurance Game”, Utilitas , 21 (3): 297–326.

- Moloney, P., 2011, “Hobbes, Savagery, and International Anarchy”, American Political Science Review , 105 (1): 189–204.