- AP Calculus

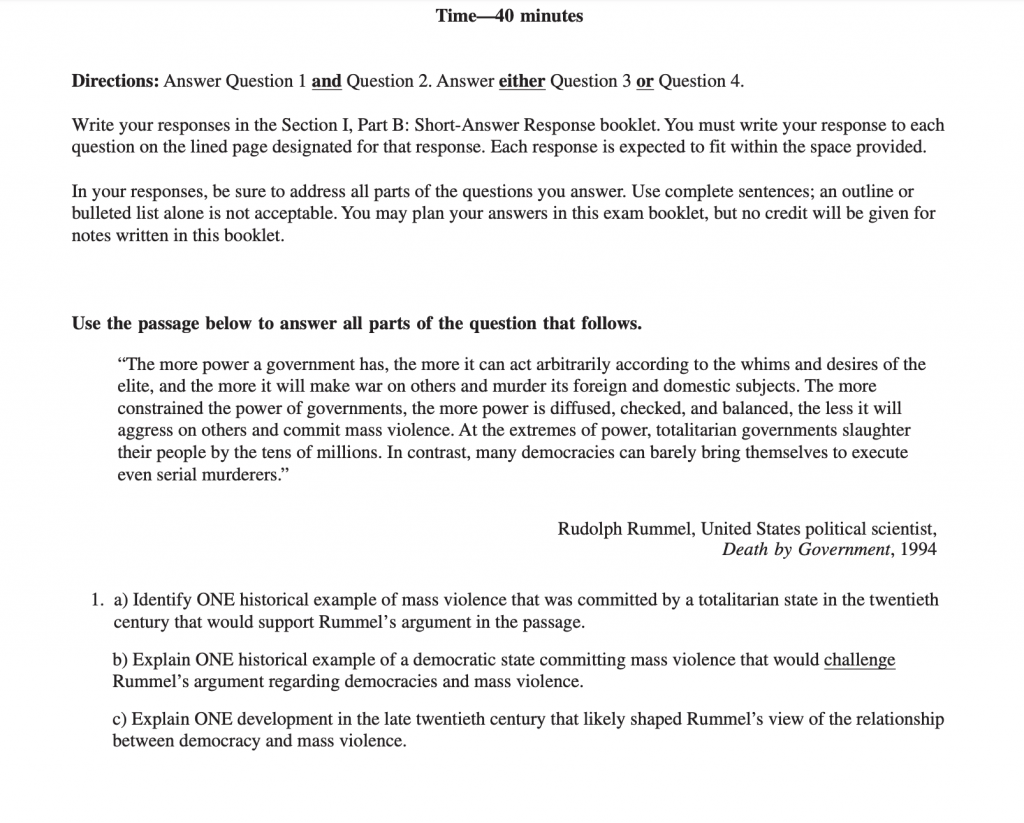

- AP Chemistry

- AP U.S. History

- AP World History

- Free AP Practice Questions

- AP Exam Prep

AP World History: Sample DBQ Thesis Statements

Using the following documents, analyze how the Ottoman government viewed ethnic and religious groups within its empire for the period 1876–1908. Identify an additional document and explain how it would help you analyze the views of the Ottoman Empire.

Crafting a Solid Thesis Statement

Kaplan Pro Tip Your thesis can be in the first or last paragraph of your essay, but it cannot be split between the two. Many times, your original thesis is too simple to gain the point. A good idea is to write a concluding paragraph that might extend your original thesis. Think of a way to restate your thesis, adding information from your analysis of the documents.

Thesis Statements that Do NOT Work

There were many ways in which the Ottoman government viewed ethnic and religious groups.

The next statement paraphrases the historical background and does not address the question. It would not receive credit for being a thesis.

The Ottoman government brought reforms in the Constitution of 1876. The empire had a number of different groups of people living in it, including Christians and Muslims who did not practice the official form of Islam. By 1908 a new government was created by the Young Turks and the sultan was soon out of his job.

This next sentence gets the question backward: you are being asked for the government’s view of religious and ethnic groups, not the groups’ view of the government. Though the point-of-view issue is very important, this statement would not receive POV credit.

People of different nationalities reacted differently to the Ottoman government depending on their religion.

The following paragraph says a great deal about history, but it does not address the substance of the question. It would not receive credit because of its irrelevancy.

Throughout history, people around the world have struggled with the issue of political power and freedom. From the harbor of Boston during the first stages of the American Revolution to the plantations of Haiti during the struggle to end slavery, people have battled for power. Even in places like China with the Boxer Rebellion, people were responding against the issue of Westernization. Imperialism made the demand for change even more important, as European powers circled the globe and stretched their influences to the far reaches of the known world. In the Ottoman Empire too, people demanded change.

Thesis Statements that DO Work

Now we turn to thesis statements that do work. These two sentences address both the religious and ethnic aspects of the question. They describe how these groups were viewed.

The Ottoman government took the same position on religious diversity as it did on ethnic diversity. Minorities were servants of the Ottoman Turks, and religious diversity was allowed as long as Islam remained supreme.

This statement answers the question in a different way but is equally successful.

Government officials in the Ottoman Empire sent out the message that all people in the empire were equal regardless of religion or ethnicity, yet the reality was that the Turks and their version of Islam were superior.

Going Beyond the Basic Requirements

- have a highly sophisticated thesis

- show deep analysis of the documents

- use documents persuasively in broad conceptual ways

- analyze point of view thoughtfully and consistently

- identify multiple additional documents with sophisticated explanations of their usefulness

- bring in relevant outside information beyond the historical background provided

Final Notes on How to Write the DBQ

- Take notes in the margins during the reading period relating to the background of the speaker and his/her possible point of view.

- Assume that each document provides only a snapshot of the topic—just one perspective.

- Look for connections between documents for grouping.

- In the documents booklet, mark off documents that you use so that you do not forget to mention them.

- As you are writing, refer to the authorship of the documents, not just the document numbers.

- Mention additional documents and the reasons why they would help further analyze the question.

- Mark off each part of the instructions for the essay as you accomplish them.

- Use visual and graphic information in documents that are not text-based.

Don’t

- Repeat information from the historical background in your essay.

- Assume that the documents are universally valid rather than presenting a single perspective.

- Spend too much time on the DBQ rather than moving on to the other essay.

- Write the first paragraph before you have a clear idea of what your thesis will be.

- Ignore part of the question.

- Structure the essay with just one paragraph.

- Underline or highlight the thesis. (This may be done as an exercise for class, but it looks juvenile on the exam.)

You might also like

Call 1-800-KAP-TEST or email [email protected]

Prep for an Exam

MCAT Test Prep

LSAT Test Prep

GRE Test Prep

GMAT Test Prep

SAT Test Prep

ACT Test Prep

DAT Test Prep

NCLEX Test Prep

USMLE Test Prep

Courses by Location

NCLEX Locations

GRE Locations

SAT Locations

LSAT Locations

MCAT Locations

GMAT Locations

Useful Links

Kaplan Test Prep Contact Us Partner Solutions Work for Kaplan Terms and Conditions Privacy Policy CA Privacy Policy Trademark Directory

AP World History: Modern

Review the free-response questions from the 2024 ap exam., exam overview.

Exam questions assess the course concepts and skills outlined in the course framework. For more information, download the AP World History: Modern Course and Exam Description (CED).

Encourage your students to visit the AP World History: Modern student page for exam information.

Rubrics Updated for 2023-24

We’ve updated the AP World History: Modern document-based question (DBQ) and long essay question (LEQ) rubrics for the 2023-24 school year.

This change only affects the DBQ and LEQ scoring, with no change to the course or the exam: the exam format, course framework, and skills assessed on the exam all remain unchanged.

The course and exam description (CED) has been updated to include:

- Revised rubrics (general scoring criteria) for the DBQ and LEQ.

- Revised scoring guidelines for the sample DBQ and LEQ within the CED.

Wed, May 15, 2024

AP World History: Modern Exam

Exam format.

The AP World History: Modern Exam has consistent question types, weighting, and scoring guidelines, so you and your students know what to expect on exam day.

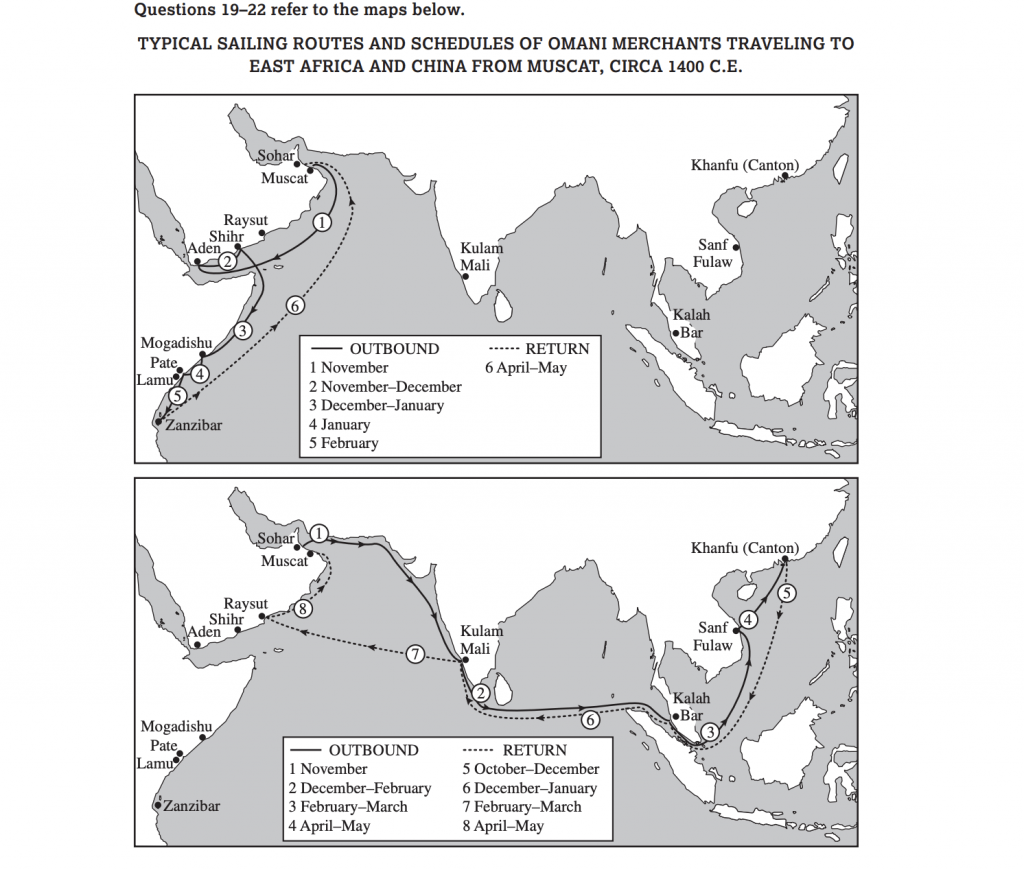

Section I, Part A: Multiple Choice

55 Questions | 55 Minutes | 40% of Exam Score

- Questions usually appear in sets of 3–4 questions.

- Students analyze historical texts, interpretations, and evidence.

- Primary and secondary sources, images, graphs, and maps are included.

Section I, Part B: Short Answer

3 Questions | 40 Minutes | 20% of Exam Score

- Students analyze historians’ interpretations, historical sources, and propositions about history.

- Questions provide opportunities for students to demonstrate what they know best.

- Some questions include texts, images, graphs, or maps.

- Question 1 is required, includes 1 secondary source, and focuses on historical developments or processes between the years 1200 and 2001.

- Question 2 is required, includes 1 primary source, and focuses on historical developments or processes between the years 1200 and 2001.

- Students choose between Question 3 (which focuses on historical developments or between the years 1200 and 1750) and Question 4 (which focuses on historical developments or processes between the years 1750 and 2001) for the last question. No sources are included for either Question 3 or Question 4.

Section II: Document-Based Question and Long Essay

2 questions | 1 Hour, 40 minutes | 40% of Exam Score

Document-Based Question (DBQ) Recommended time: 1 Hour (includes 15-minute reading period) | 25% of Exam Score

- Students are presented with 7 documents offering various perspectives on a historical development or process.

- Students assess these written, quantitative, or visual materials as historical evidence.

- Students develop an argument supported by an analysis of historical evidence.

- The document-based question focuses on topics from 1450 to 2001.

Long Essay Recommended time: 40 Minutes | 15% of Exam Score

- Students explain and analyze significant issues in world history.

- The question choices focus on the same skills and the same reasoning process (e.g., comparison, causation, or continuity and change), but students choose from 3 options, each focusing primarily on historical developments and processes in different time periods—either 1200–1750 (option 1), 1450–1900 (option 2), or 1750–2001 (option 3).

Exam Questions and Scoring Information

Ap world history: modern exam questions and scoring information.

View free-response questions and scoring information from this year's exam and past exams.

Score Reporting

Ap score reports for educators.

Access your score reports.

AP World History: Modern Exam Tips

Keep an eye on your time..

Monitor your time carefully. Make sure not to spend too much time on any one question so that you have enough time to answer all of them. If you reach the end of the test with time to spare, go back and review your essays. And don’t waste time restating the question in your answers: that won’t earn points.

Plan your answers.

Don’t start to write immediately: that can lead to a string of disconnected, poorly planned thoughts. Carefully analyze the question, thinking through what is being asked and evaluating the points of view of the sources and authors. Identify the elements that must be addressed in the response. For example, some questions may require you to consider the similarities between people or events, and then to think of the ways they are different. Others may ask you to develop an argument with examples to support it. Be sure to answer exactly what is being asked in the question prompt!

Integrate evidence.

After you have determined how to answer the question, consider what evidence you can incorporate into your response. Review the evidence you learned during the year that relates to the question and then decide how it fits into the analysis. Does it demonstrate a similarity or a difference? Does it argue for or against a generalization that is being addressed?

Decide your thesis statement.

Begin writing only after you have thought through your evidence and have determined what your thesis statement will be. Once you have done this, you will be in a position to answer the question analytically instead of in a rambling narrative.

Support your thesis statement.

Make your overarching statement or argument, then position your supporting evidence so that it is obviously directed to answering the question. State your points clearly and explicitly connect them to the larger thesis, rather than making generalizations.

Elaborate on the evidence.

Don’t just paraphrase or summarize your evidence. Clearly state your intent, then use additional information or analysis to elaborate on how these pieces of evidence are similar or different. If there is evidence that refutes a statement, explain why. Your answer should show that you understand the subtleties of the questions.

Answering free-response questions from previous AP Exams is a great way to practice: it allows you to compare your own responses with those that have already been evaluated and scored. Go to the Exam Questions and Scoring Information section of the AP World History: Modern Exam page on AP Central to review the latest released free-response questions and scoring guidelines. Older questions and scoring information are available on the Past Exam Questions page.

Pay close attention to the task verbs used in the free-response questions. Each one directs you to complete a specific type of response. Here are the task verbs you’ll see on the exam:

- Compare: Provide a description or explanation of similarities and/or differences.

- Describe: Provide the relevant characteristics of a specified topic.

- Evaluate: Judge or determine the significance or importance of information, or the quality or accuracy of a claim.

- Explain: Provide information about how or why a relationship, process, pattern, position, situation, or outcome occurs, using evidence and/or reasoning; explain “how” typically requires analyzing the relationship, process, pattern, position, situation, or outcome; whereas, explain “why” typically requires analysis of motivations or reasons for the relationship, process, pattern, position, situation, or outcome.

- Identify: Indicate or provide information about a specified topic, without elaboration or explanation.

- Support an argument: Provide specific examples and explain how they support a claim.

AP Short-Answer Response Booklets

Important reminders for completing short-answer responses.

Write each response only on the page designated for that question.

- 1 lined page is provided for each short-answer question.

- The question number is printed as a large watermark on each page, and also appears at the top and bottom of the response area.

Keep responses brief–don’t write essays.

- The booklet is designed to provide sufficient space for each response.

- Longer responses will not necessarily receive higher scores than shorter ones that accomplish all the tasks set by the question.

See a diagram that shows you where to find the question number on pages in the response booklet.

Choose Your Test

Sat / act prep online guides and tips, the best ap world history study guide: 6 key tips.

Advanced Placement (AP)

Are you taking AP World History this year? Or considering taking it at some point in high school? Then you need to read this AP World History study guide. Instead of cramming every single name, date, and place into your head, learn how to study for the AP World History exam so that you can learn the major ideas and feel ready for test day. We'll also go over some key strategies you can use to help you prepare effectively.

The AP World History test is challenging — just 13.2% of test takers got a 5 in 2021 . But if you study correctly throughout the year, you could be one of the few students who aces this test. Below are six tips to follow in order to be well prepared for the AP World History exam. Read through each one, apply them to your test prep, and you'll be well on your way to maximizing your score!

Why You Should Study for the AP World History Test

Is it really that important to study for the AP World History test? Absolutely! But why?

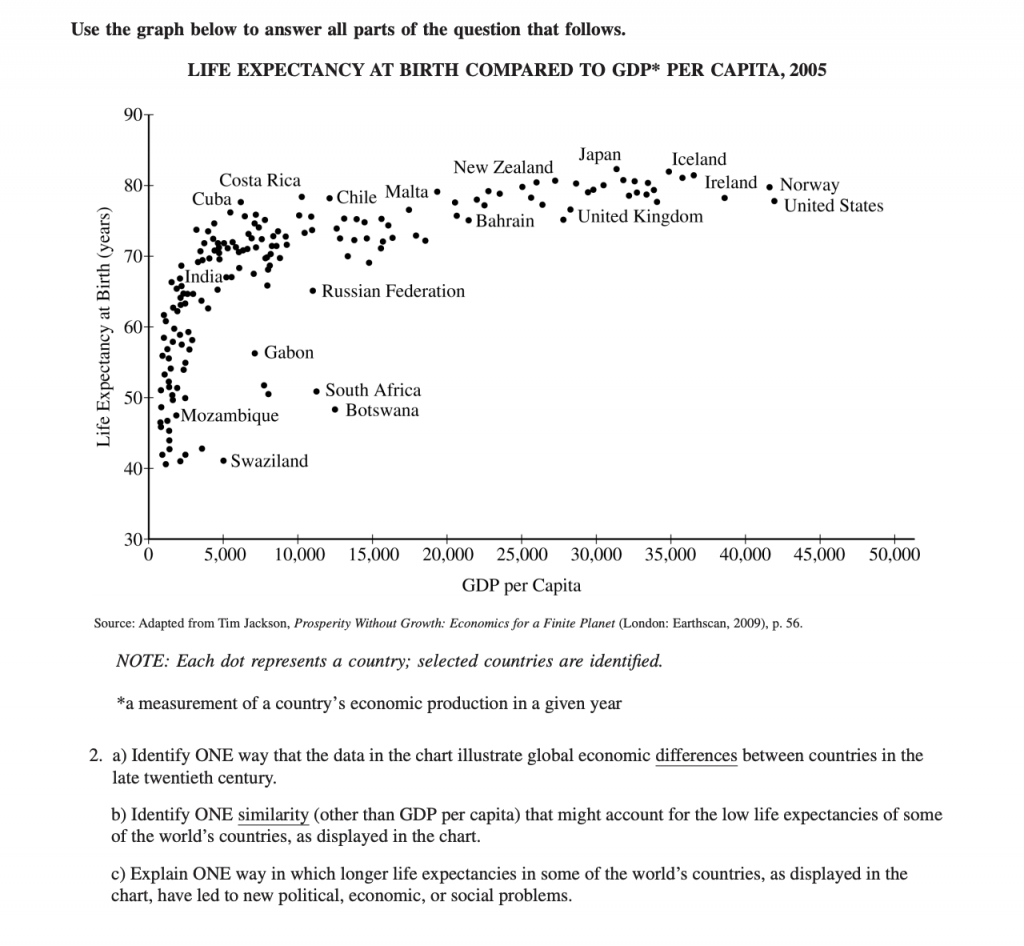

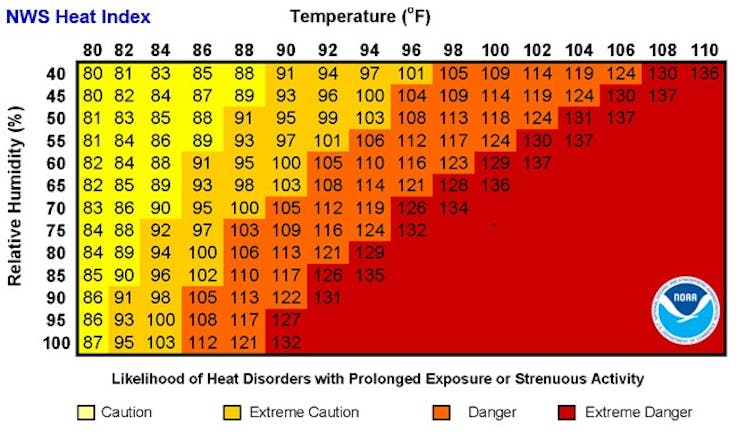

Let's start by taking a look at the kinds of scores students usually get on the exam. The following chart shows what percentage of test takers received each possible AP score (1-5) on the AP World History test in 2022:

| 5 | 13.2% |

| 4 | 21.9% |

| 3 | 27.0% |

| 2 | 23.7% |

| 1 | 14.3% |

Source: The College Board

As you can see, roughly 49% of test takers scored a 2 or 3, about 35% scored a 4 or 5, and only 14% scored a 1. Since most test takers scored a 3 or lower on this test , it's safe to say that a lot of AP World History students are not scoring as well as they could be. (That said, the test underwent some big changes beginning in the 2019-2020 school year , so we can't make too many direct comparisons between this new version of the test and the old one. We will talk more about these changes in the next section.)

While a 3 is not a bad AP score by any means, some colleges such as Western Michigan University require at least a 4 in order to get credit for some exams. If the schools you're applying to want a 4 or higher, putting in ample study time for the test is a definite must.

In addition, if you're applying to highly selective schools , a 5 on the AP World History test (or any AP test, really) could act as a tipping point in your favor during the admissions process.

Finally, getting a low score on this test—i.e., a 1 or 2—might make colleges doubt your test-taking abilities or question your potential to succeed at their school. You don't want this to happen!

What's on the AP World History Exam?

Before we give you our six expert study tips for AP World History, let's briefly go over the structure and content of the test.

The AP World History exam consists of two sections: Section 1 and Section 2 . Each section also consists of two parts: Part A and Part B . Here's what you'll encounter on each part of each World History section:

| 1A | Multiple Choice | 55 mins | 55 | 40% |

| 1B | Short Answer | 40 mins | 3 (for third, choose 1 of 2 prompts) | 20% |

| 2A | Document-Based Question (DBQ) | 60 mins (including 15-min reading period) | 1 | 25% |

| 2B | Long Essay | 40 mins | 1 (choose 1 of 3 prompts) | 15% |

And here is an overview of the types of tasks you'll be asked to perform:

- Analyze historical texts as well as historians' opinions and interpretations of history

- Assess historical documents and make an argument to support your assessment

- Write an essay concerning an issue in world history

Note that as of the 2019-2020 school year, AP World History is now much smaller in scope and is called AP World History: Modern (another course and exam called AP World History: Ancient is in the process of being made by the College Board).

These changes have been put in place mainly as a response to ongoing complaints that the original World History course was way too broad in scope, having previously covered thousands of years of human development. Hopefully, this will make the test somewhat easier!

Now that you understand exactly how the AP World History test is set up, let's take a look at our six expert study tips for it.

How to Study for AP World History: 6 Key Tips

Below are our top tips to help you get a great score on the AP World History test.

Tip 1: Don't Try to Memorize Everything

If you start your AP World History class with the expectation of memorizing the entirety of human history, think again .

Although AP World History tests a wide span of time, you aren't expected to learn every tiny detail along the way; rather, this course focuses on teaching major patterns, key cultural and political developments, and significant technological developments throughout history .

Starting in 2019-2020, the AP World History course and exam will be arranged in nine units , which cover a range of periods starting around 1200 CE and ending with the present:

| Unit 1: The Global Tapestry | 1200-1450 | 8-10% |

| Unit 2: Networks of Exchange | 8-10% | |

| Unit 3: Land-Based Empires | 1450-1750 | 12-15% |

| Unit 4: Transoceanic Interconnections | 12-15% | |

| Unit 5: Revolutions | 1750-1900 | 12-15% |

| Unit 6: Consequences of Industrialization | 12-15% | |

| Unit 7: Global Conflict | 1900-present | 8-10% |

| Unit 8: Cold War and Decolonization | 8-10% | |

| Unit 9: Globalization | 8-10% |

For each period, you should know the major world powers and forces driving politics, economic development, and social/technological change; however, you don't have to have every detail memorized in order to do well on the test . Instead, focus on understanding big patterns and developments, and be able to explain them with a few key examples.

For instance, you don't necessarily need to know that in 1492 Columbus sailed the ocean blue; you also don't need to know the details of his voyages or the particulars of his brutality . Nevertheless, you should be able to explain why the European colonization of the Americas happened , as well as the economic effects it had on Europe, Africa, and the Americas, and how colonization impacted the lives of people on these three continents.

Knowing a few concrete examples is essential to succeeding on the short-answer section. Short-answer questions 1 and 2 will present you with a secondary source and a primary source, respectively, and then ask you to provide several examples or reasons for a broader theme or historical movement that relates to the information provided.

You'll have flexibility in what specific examples you choose , just so long as they are relevant. The short-answer section is three questions long and worth 20% of your total test score. You will have 40 minutes to complete it.

Concrete examples can also bolster your essays and improve your ability to break down multiple-choice questions on the topic; however, focus first on understanding the big picture before you try to memorize the nitty-gritty.

If you're coming from AP US History, this advice might seem odd. But unlike US History, which is more fine-grained, the AP World History exam writers do not expect you to know everything, as they test a much larger topic . AP US History is essentially a test of 400 years of history in one location, so it's fair to expect students to know many proper names and dates.

But for World History, that same level of detail isn't expected; this test takes place across 800 years all around the world. Instead, you should focus on understanding the general patterns of important topics through history . This won't only save you time but will also keep you sane as your textbook hurls literally hundreds of names, places, and dates at you throughout the year.

Speaking of your textbook ...

Tip 2: Keep Up With Your Reading!

When it comes to AP World History, you can't sleep through the class all year, skim a prep book in April, and then expect to get a perfect 5 on the test. You're learning a huge chunk of human history, after all! Trying to cram for this test late in the game is both stressful and inefficient because of the sheer volume of material you have to cover.

And all that reading would hurt your eyes.

Instead, keep up with your reading and do well in your World History class to ensure you're building a strong foundation of knowledge throughout the year. This way, when spring comes, you can focus on preparing for the exam itself and the topics it's likely to test, as opposed to frantically trying to learn almost a thousand years of human history in just two months.

If your teacher isn't already requiring you to do something like this, be sure to keep notes of your readings throughout the school year. This could be in the form of outlines, summaries, or anything else that's useful to you. Taking notes will help you process the readings and remember them better. Your notes will also be an invaluable study tool in the spring.

Finally, check the website of whatever textbook your class uses. Many textbook websites have extra features, such as chapter outlines and summaries , which can be excellent study resources for you throughout the year.

Tip 3: Read a Prep Book (or Two) in the Spring

Even if you keep up with AP World History throughout the year, you're probably going to be a bit hazy on topics you learned in September when you start studying for the test in March or April. This is why we recommend getting a prep book , which will provide a much broader overview of world history, focusing especially on topics tested on the exam. (Make sure it's an updated book for the new Modern focus of the AP World History course and exam!)

If you've been learning well throughout the school year, reading a prep book will trigger your background knowledge and help you review . Think of your prep book as your second, much quicker pass through world history.

And in case you're wondering—no, the prep book alone will not fill you in on the necessary depth of knowledge for the entire test. You can't replace reading your textbook throughout the year with reading a prep book in the spring. The AP World History multiple-choice section especially can ask some pretty specific questions, and you'd definitely have blind spots if all you did is read a prep book and not an actual textbook.

Furthermore, you wouldn't be able to explain examples in your essay in as much detail if you've only read a few paragraphs about major historical events.

Tip 4: Get Ready to Move at 1 MPQ (Minute per Question)

To prepare for the AP World History exam, knowing the material is just half the battle. You also need to know how to use your time effectively , especially on the multiple-choice section.

The multiple-choice section (Section 1, Part A) asks 55 questions in 55 minutes and is worth 40% of your total score. This gives you just one minute per question , so you'll have to move fast. And to be ready for this quick pace, practice is key.

Taking the AP World History exam without practicing first would be like jumping into a NASCAR race without a driver's license.

To practice pacing yourself, it's crucial that you get a prep book containing practice tests . Even if you've read your textbook diligently, taken notes, and reviewed the material, it's really important to practice actual multiple-choice sections so you can get used to the timing of the test.

Although there are a handful of stand-alone questions, most come in sets of three to four and ask you to look at a specific source, such as a graph, image, secondary source, or map. It's a good idea to skip and return to tough questions (as long as you keep an eye on the time!).

Your teacher should be giving you multiple-choice quizzes or tests throughout the year to help you prepare for the test. If your teacher isn't doing this, it will, unfortunately, be up to you to find multiple-choice practice questions from prep books and online resources. See our complete list of AP World History practice tests here (and remember to find updated materials for the new 2020 Modern exam).

You need to create your own multiple-choice strategy as you study , such as using the process of elimination, being ready to read and analyze pictures and charts, and being constantly aware of your time. I recommend wearing a watch when you practice so you can keep an eye on how long you spend on each question. Just make sure it's not a smart watch—unfortunately, those aren’t allowed!

Finally, make sure to answer every question on the exam . There are no penalties for incorrect answers, so you might as well guess on any questions you're not sure about or have no time for.

In short, make sure you practice AP World History multiple-choice questions so that when you sit down to take the exam, you'll feel confident and ready to move fast.

Tip 5: Practice Speed-Writing for the Free-Response Section

The AP World History exam has two essay questions that together account for 40% of your AP World History score . You'll get 60 minutes for the Document-Based Question, or DBQ, including a 15-minute reading period; the DBQ is worth 25% of your final grade. After, you will get 40 minutes for the Long Essay, which is worth 15% of your score.

For each essay, you need to be able to brainstorm quickly and write an essay that answers the prompt, is well organized, and has a cogent thesis . A thesis is a one-sentence summary of your main argument. For the sake of AP essays, it's best to put your thesis at the end of the introductory paragraph so the grader can find it quickly.

When organizing your essay, have each paragraph explain one part of the argument , with a topic sentence (basically, a mini-thesis) at the beginning of each paragraph that explains exactly what you're going to say.

For the DBQ, you'll need to bring most of the provided documents into your argument in addition to your background knowledge of the period being tested. For example, in a DBQ about the effects of Spanish Influenza during World War I, you'd need to demonstrate your knowledge of WWI as well as your ability to use the documents effectively in your argument. See our complete guide to writing a DBQ here .

For the Long Essay, it's up to you to provide specific historical examples and show your broad understanding of historical trends . (Again, this is why doing your reading is so important, since you'll have to provide and explain your own historical examples!)

Throughout the year, your teacher should be having you do writing assignments, including in-class essays, to teach you how to write good essays quickly. Since you'll be writing your essays by hand for the test, you should ideally be writing your practice essays by hand as well. If you struggle with writing by hand quickly, you can build up your writing fluency (that is, your ability to quickly translate thoughts to words) by writing additional practice essays on your own .

If you need to work on writing fluency, it's best to practice with easier writing topics . First, find a journal prompt to write about ( this website has hundreds ). Next, set a timer; between 10 and 15 minutes is best. Finally, write as much (and as fast!) as you can about the prompt, without making any big mistakes in spelling or grammar.

When time's up, count how many words you wrote . If you do this a few times a week, you'll build up your writing speed, and your word counts will continue to grow. Once you've built up this skill, it will be much easier to tackle the AP World History free-response section.

You can also practice on your own using old AP World History free-response questions . However, note that the test was revised for 2019-20 (now its focus is only on 1200-present) and 2016-17, so old questions will have old content and instructions .

In fact, there actually used to be three essays on the AP World History test—in addition to the DBQ, there was a "Change Over Time" essay and a "Comparison" essay. Now, there's just one long essay. Be sure to compare older questions with the most up-to-date examples from the most current AP Course and Exam Description .

Tip 6: Take Practice Exams and Set a Target Score

In the spring, aim to take at least one full practice exam —ideally in late March or early April—once you've learned most of the World History material. By a full practice exam, we mean the entire AP World History test. Time yourself and take it in one sitting, following official time restrictions.

Why should you do this? It will give you a chance to experience what it's like to take a full AP World History exam before you sit for the real thing. This helps you build stamina and perfect your timing. All the practice in the world won't help you if you run out of steam on your last essay question and can barely think.

Also, set a target score for each section. Good news: you don't need to be aiming for 100% on Section 1 and perfect scores on every essay in Section 2 in order to secure a 5 — the highest possible score . Far from it, actually!

The truth is that a high multiple-choice score (50/55) with average short-answer and free-response scores (say, 6/9 on short answer, 5/7 on the DBQ, and 4/6 on the long essay) can net you a score of 5 . Likewise, an average multiple-choice score (35/55) with high short-answer and free-response scores (say, 8/9 on short answer, 6/7 on the DBQ, and 5/6 on the long essay) can also net you a 5 .

Set realistic score targets based on your personal strengths. For example, a really good writing student might go the average multiple choice/strong essay route, while a stronger test taker might go the other way around. You could also be somewhere in-between.

In addition, don't be intimidated if your target score is a lot higher than your current scores . The whole point of practicing is to eventually meet your target!

Once you have a target score, practice, practice, practice ! Use old exams, the practice exams in (high-quality) prep books, and the free-response questions linked above. You can even ask your teacher for old AP World History tests and essay questions. (Just be aware of the key changes to the AP World History exam in recent years so that you can tweak practice questions as needed.)

The more you practice before the test, the more likely you are to meet—or even exceed!—your AP score goal.

Bottom Line: How to Prep for the AP World History Test

Although AP World History is a challenging test, if you follow all our advice in this AP World History study guide and prepare correctly throughout the school year, you can definitely pass the exam and might even be one of the few students who gets a 5 !

Just make sure to keep up with your reading, use an updated prep book in the spring, and practice a lot for the multiple-choice and free-response sections. With clear target scores for each section and plenty of practice under your belt, you will have the strongest chance of getting a 5 on test day !

What's Next?

How many AP classes should you take in total? Find out here in our expert guide .

How hard is AP World History compared with other AP tests? We've come up with a list of the hardest and easiest AP tests , as well as the average scores for every exam .

For more tips on doing well in all your classes, from AP to IB to honors, read this expert guide to getting a perfect 4.0 , written by PrepScholar founder Allen Cheng . Even if you're not going for perfection, you'll learn all the skills you need to work hard, act smart, and get better grades.

Also studying for the SAT/ACT? In a hurry? Learn how to cram for the ACT or SAT .

Halle Edwards graduated from Stanford University with honors. In high school, she earned 99th percentile ACT scores as well as 99th percentile scores on SAT subject tests. She also took nine AP classes, earning a perfect score of 5 on seven AP tests. As a graduate of a large public high school who tackled the college admission process largely on her own, she is passionate about helping high school students from different backgrounds get the knowledge they need to be successful in the college admissions process.

Ask a Question Below

Have any questions about this article or other topics? Ask below and we'll reply!

Improve With Our Famous Guides

- For All Students

The 5 Strategies You Must Be Using to Improve 160+ SAT Points

How to Get a Perfect 1600, by a Perfect Scorer

Series: How to Get 800 on Each SAT Section:

Score 800 on SAT Math

Score 800 on SAT Reading

Score 800 on SAT Writing

Series: How to Get to 600 on Each SAT Section:

Score 600 on SAT Math

Score 600 on SAT Reading

Score 600 on SAT Writing

Free Complete Official SAT Practice Tests

What SAT Target Score Should You Be Aiming For?

15 Strategies to Improve Your SAT Essay

The 5 Strategies You Must Be Using to Improve 4+ ACT Points

How to Get a Perfect 36 ACT, by a Perfect Scorer

Series: How to Get 36 on Each ACT Section:

36 on ACT English

36 on ACT Math

36 on ACT Reading

36 on ACT Science

Series: How to Get to 24 on Each ACT Section:

24 on ACT English

24 on ACT Math

24 on ACT Reading

24 on ACT Science

What ACT target score should you be aiming for?

ACT Vocabulary You Must Know

ACT Writing: 15 Tips to Raise Your Essay Score

How to Get Into Harvard and the Ivy League

How to Get a Perfect 4.0 GPA

How to Write an Amazing College Essay

What Exactly Are Colleges Looking For?

Is the ACT easier than the SAT? A Comprehensive Guide

Should you retake your SAT or ACT?

When should you take the SAT or ACT?

Stay Informed

Get the latest articles and test prep tips!

Looking for Graduate School Test Prep?

Check out our top-rated graduate blogs here:

GRE Online Prep Blog

GMAT Online Prep Blog

TOEFL Online Prep Blog

Holly R. "I am absolutely overjoyed and cannot thank you enough for helping me!”

Get the Reddit app

Welcome to the AP World History subreddit. It is meant to be an open forum for all-things-AP-World. Teachers and students are encouraged to post links, information, and questions that may help others as the attempt to conquer the AP World History Exam.

How to write a Document-Based Question (DBQ)

Document-Based Questions (DBQ)

You have 45 minutes to read documents and a 5 minute window for you to submit your answer

What you need to do:

Step 1. Read and understand the question

Stop yourself and read it carefully

What is the historical thinking skill embedded in the question?

Is it asking you to compare two things?

Is it asking you to talk about change over time?

Write it down, highlight it, underline it

2. What kind of categories?

Ex. “Political change”

3. What is the time period given?

Make sure your essays deal with issues within that time period

Step 2. Read through the documents quickly

Try to spend at least 10 minutes (no more) reading and analyzing the document

When reading each document quickly, you need to look for:

What is the source of this document?

Who is speaking to who?

2. Summarize the main idea

Referencing to the prompt

The documents are used as evidence and supposed to help you answer the question

“If I only had this document, how would it answer the question?”

3. Group your documents into two groups

Ex. If documents are giving economic reasons and others are giving religious reasons, group them like that

Grouping your documents by category is higher level and shows that you’ve made connections between the documents

10-point skip

Thesis: 0-1 Point

Important because it organizes your argument

Rubric -- You need to write one or two sentences which are historically defensible and establishes a line of reasoning

Specific historical evidence

Thesis should be packed, should be your argument in miniature

Thesis Formula -- Although X, because A and B, therefore Y.

X: Counterargument

A and B: Specific Evidence

Y: Your argument

Ex. DBQ Prompt: “Evaluate the extent to which the Portuguese transformed maritime trade in the Indian Ocean in the sixteenth century.”

Thesis: “Although the arrival of the Portuguese was a very important change in indian ocean maritime trade in the sixteenth century (X), because the Portugese never extended their control beyond a few ports (A) and had to compete with Indian merchants and regional states such as the Ottoman Empire (B), it did not completely transform the trade (Y) .”

Contextualization: 0-1 Point

Your argument in a larger historical context

Rubric -- Explain the historical context before during or after the time period of your prompt

The most intuitive way is explaining the events that occured before the given time period

Good idea to talk about specific maritime technology during that period

Your contextualization (3-4 sentences) needs to relate to the prompt

Content -- 2-3 Vocabulary Words

Specific things that occurred during the periods

Explain the terms

Connect them to your arguments

Evidence: 0-5 Points

1 Point: Successfully describing the contents of 2 documents

2 Points: Successfully supporting your argument with 2 documents

3 Points: Supporting your argument with at least 4 documents

Recommend using all 5 documents because if you get an interpretation wrong, you could still get 3 points

2 Points: Writing about evidence related to your prompt that is not mentioned in the documents (One point each time)

Don’t quote from the documents

Difference in describing and arguing the documents

Argue with your evidence

Evidence from the documents: 3 points

Grouping documents

Topic sentences for body paragraphs

Ex. Grouping documents by “economics”

Start by writing a topic sentence for the paragraph that explained why economics was the cause of -----

In the paragraph, use documents to demonstrate why that is true

Evidence beyond the documents: 0-2 Points

Connect specific evidence to arguments

Must not be mentioned in documents

Name a piece of evidence, explain it, and connect it

Analysis and Reasoning: 0-3 Points

Sourcing documents (2 points)

To source a document means to show how that documents historical situation audience purpose or point of view is relevant

Historical Situation:

Place document in larger historical context

Audience:

To whom was this written?

What was this document intended to do?

Point of View:

Why do they say what they say, in the way that they say it?

You don’t have to do “H.A.P.P.” on all the documents

Choose one that makes the most sense out of that document

You just have to successfully source 2 documents

Try to source at least 3, in case you get one wrong

Analysis & Reasoning Complexity: 0-1 Point

Very Rare*

Is your essay nuanced? Does it analyze multiple variables? DOes it explain the complexity of the topic at hand with skill and with beauty? How to Write a DBQ - Heimler’s History

AP® World History

The ultimate list of ap® world history tips.

- The Albert Team

- Last Updated On: March 1, 2022

Acing the AP® World History exam is undeniably a difficult task. Only 8.6% of students who took the 2019 exam scored a 5, and only 18.8% of students scored a 4. The test’s difficulty ultimately lies in how it forces you to analyze the overall patterns of history in addition to the small details.

By familiarizing yourself with trends in history as opposed to just memorizing facts, you can get a 5 on the AP® World History exam. The test can be cracked by understanding how history operates, how the world changes through cause and effect. Admittedly, it can be difficult to learn how to study for the AP® World History exam.

However, we’re here to help you score a 5 and formulate the perfect AP® World History study plan. Through practice and preparation, scoring a five is possible! By taking AP® World History practice tests, creating a thorough study plan, and maintaining a daily study routine, you will be able to ace this exam.

What We Review

Overall How To Study for AP® World History: 9 Tips for 4s and 5s

1. answer all of the questions.

Make sure your thesis addresses every single part of the question being asked for the AP® World History free-response section . Many times, AP® World History prompts are multifaceted and complex, asking you to engage with multiple aspects of a certain concept or historical era. Missing a single part can cost you significantly in the grading of your essay.

2. Lean one way in your argument

While it is possible to write essays that take two sides of an argument, it is always easier to choose a side and defend it. Trying to appease both sides during a timed essay often leads to an argument that’s not nearly as strong when you take a stance.

Here is an example of a weak thesis:

The recovery of Russia and China after the Mongols had many similarities and differences .

Here is a better one:

While both Russia and China built strong centralized governments after breaking free from the Mongols, Russia imitated the culture and technology of Europe while China became isolated and built upon its own foundations.

3. Lead your reader

Help your reader understand where you are going as you answer the prompt to the essay. Provide them with a map of a few of the key areas you are going to talk about in your essay. This should be done in your opening thesis paragraph. An easy way to achieve this is by outlining what is going to be discussed in your body paragraphs during the introduction paragraph.

4. Organize your essay with 2-3-1 in mind

When outlining the respective topics you will be discussing, start from the topic you know second best, then the topic you know least, before ending with your strongest topic area. In other words, make your roadmap 2-3-1 so that you leave your reader with the feeling that you have a strong understanding of the question being asked. This will help scaffold your argument, and it will make the essay much more readable.

5. Analyze rather than merely summarize

When the AP® exam asks you to analyze, you want to think about the respective parts of what is being asked and look at the way they interact with one another. This means that when you are performing your analysis on the AP® World History test , you want to make it very clear to your reader of what you are breaking down into its component parts.

For example, what evidence do you have to support a point of view? Who are the important historical figures or institutions involved? How are these structures organized? How does this relate back to the overall change or continuity observed in the world?

6. Use SPICER to organize and chunk your history reading

SPICER is a useful acronym that can be used to chunk and break down history into six different categories:

- S – Social

- P – Political

- I – Intellectual

- C – Culture

- E – Economic

- R – Religious

These six categories encompass the major areas of history that you will see in your reading and on your exam. Write an S next to material that deals with social issues, an E near economic, so on and so forth. This will break up your reading into more digestible chunks.

7. Familiarize yourself with the time limits

Part of the reason why we suggest practicing essays early on is so that you get so good at writing them that you understand exactly how much time you have left when you begin writing your second to the last paragraph. You’ll be so accustomed to writing under timed circumstances that you will have no worries in terms of finishing on time.

The multiple-choice section is 55 questions and 55 minutes long, so you have one minute per question. The short answer section is 3 questions and 40 minutes long; the document-based question is 1 question and timed at 1 hour. The long essay is 1 question and timed at 40 minutes.

8. Learn the rubric

If you have never looked at an AP® World History grading rubric before you enter the test, you are going in blind. You must know the rubric like the back of your hand so that you can ensure you tackle all the points the grader is looking for. Here are the 2019 Scoring Guidelines .

While all the rubrics for the DBSs vary a bit, they mostly follow a 0-3 scale where each number represents a certain task you must fulfill within your response. The DBQ section is graded on a four-scale basis:

- A) Thesis/Claim

- B) Contextualization

- C) Evidence

- D) Analysis and Reasoning

The thesis component evaluates the strength of your thesis statement, while the contextualization section evaluates your ability to describe a broader historical context relevant to the prompt. The evidence part of the rubric evaluates your analysis and use of the texts, and the analysis and reasoning section evaluates your argument overall.

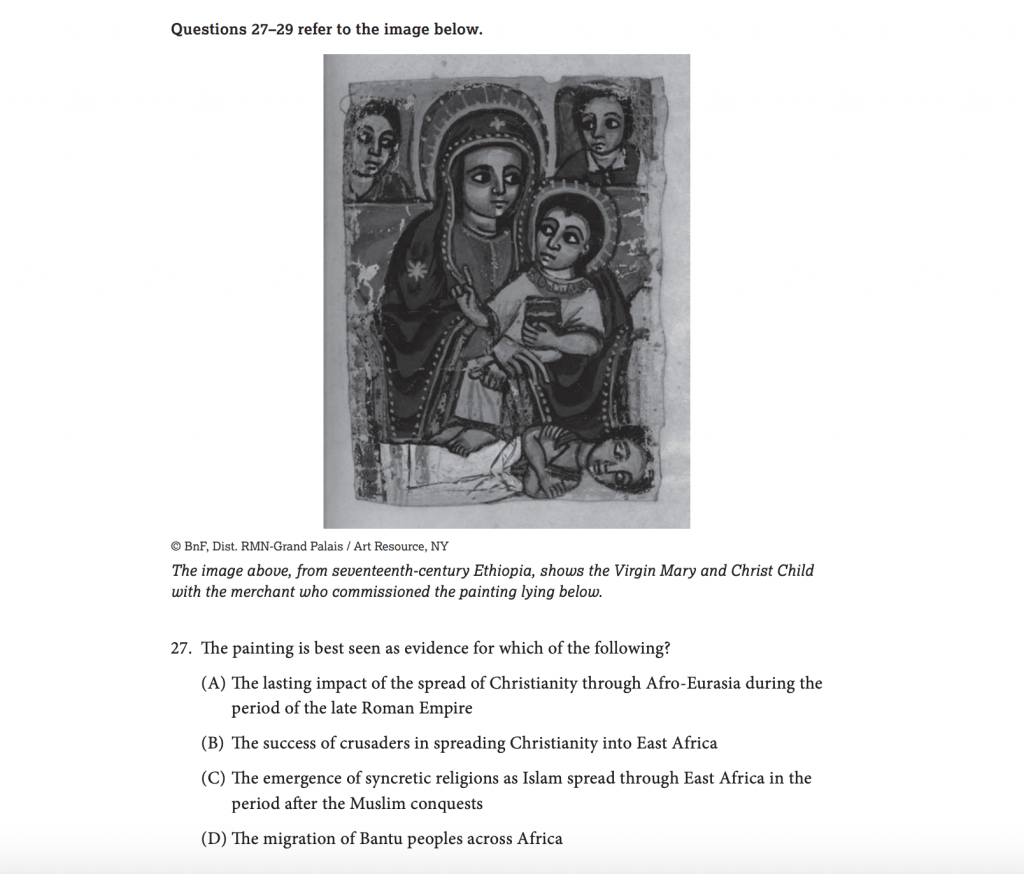

9. Familiarize yourself with analyses of art

This one is optional, but a great way to really get used to analyzing art is to visit an art museum and to listen to the way that art is described. Oftentimes the test will make you either interpret the artist’s intent and perspective or force you to expound on history through interpretation of the painting.

Here’s an example.

Notice how the painting is being used to assess an entire historical era. The painting is being used here as much more than a painting.

Return to the Table of Contents

AP® World History Multiple Choice Review: 11 Tips

1. identify key patterns of history.

You know that saying, history repeats itself? There’s a reason why people say that, and that is because there are fundamental patterns in history that can be understood and identified. This is especially true with AP® World History .

Think about patterns like cause and effect, action and reaction, dissemination and reception, oppressor vs. oppressed, etc. History can be best comprehended when you recognize patterns.

2. Use common sense

The beauty of AP® World History is when you understand the core concept being tested and the patterns in history; you can deduce the answer to the question. Identify what exactly is being asked and then go through the process of elimination to figure out the correct answer.

Now, this does not mean you do not study at all. This means, rather than study 500 random facts about world history, really hone in on understanding the way history interacts with different parts of the world.

Think about how minorities have changed over the course of history, their roles in society, etc. You want to look at things at the big picture so that you can have a strong grasp of each time period tested.

3. Familiarize yourself with AP® World History multiple-choice questions

If AP® World History is the first AP® test you’ve ever taken, or even if it isn’t, you need to get used to the way the College Board introduces and asks you questions. Find a review source to practice AP® World History questions.

Albert has hundreds of AP® World History practice questions and detailed explanations to work through. These questions are designed to encompass tons of years of World History, so you must become acquainted with how that history is presented to you.

4. Make a note of pain points

As you practice, you’ll quickly realize what you know really well, and what you know not so well. Figure out what you do not know so well and re-read that chapter of your textbook. Keep a chart or log of what you do not do quite so well, so when it comes time to review, you can quickly discern which area you need to study. Then, create flashcards of the key concepts of that chapter along with key events from that time period.

5. Supplement practice with video lectures

A fast way to learn is to do practice problems, identify where you are struggling, learn that concept more intently, and then practice again. Crash Course has created an incredibly insightful series of World History videos you can watch on YouTube here . And Useful Charts offers tons of great timeline-oriented videos on plenty of subjects including world history.

Afterward, go back and practice again. Practice makes perfect, especially when it comes to AP® World History. And a lot of these videos are actually pretty interesting.

6. Strikeout wrong answer choices

The second you can eliminate an answer choice, strike out the letter of that answer choice and circle the word or phrase behind why that answer choice is incorrect. This way, when you review your answers at the very end, you can quickly check through all of your answers.

One of the hardest things is managing time when you’re doing your second run-through to check your answers—this method alleviates that problem by reducing the amount of time it takes for you to remember why you thought a certain answer choice was wrong.

7. Answer every question

If you’re crunched on time and still have several AP® World History multiple-choice questions to answer, the best thing to do is to make sure that you answer each and every one of them. There is no guessing penalty for doing so, so take full advantage of this!

8. Skip questions holding you up and return to them later

If you find yourself spending more than a minute or so on a question, don’t let yourself get stuck. Instead, circle the number of the question, skip it, and return to it later if you have time. Since this is a timed component of the exam (55 minutes), the pacing is essential to scoring high. If you find yourself getting stuck, don’t fixate. Circle then move on and return.

9. Don’t be afraid to make educated guesses

This one dovetails nicely with the preceding tip. If you find yourself totally at a loss choosing an answer on the AP® World History multiple-choice section, make an educated guess. You are not penalized for answers you miss; your scores are counted by how many you get right. So it’s in your benefit to answer every question and leave none blank. So, when confronted with impossibly difficult questions, try and narrow the choices down a bit and then just make an educated guess.

10. Keep your eyes peeled for corresponding questions that provide answers

Sometimes, in multiple-choice exams, questions can actually sort of answer each other. For example, say question 12 depicts a painting of the 1789 Storming of the Bastille, and question 30 asks you to describe the mood of the late-eighteenth century France, you can use question 12 to help you answer question 30. Since many of the events in AP® World History correspond, you will likely see instances of this. Use it to your advantage.

11. Form a study group

Developing a strong memory of historical dates, events, figures, and all the stuff essential to AP® World History is crucial to acing the multiple-choice component of the exam. One way to build your memory is to form a study group with your classmates and meet weekly or bi-weekly. Before you meet, plan out which parts of world history you want to cover, and stick to it. Choose your group wisely because sometimes, study groups can quickly turn into hang-out sessions.

AP® World History FRQ: 17 Tips

1. Group the documents by intent

One skill tested on the AP® exam is your ability to relate documents to one another–this is called grouping. The idea of grouping is to essentially create a nice mixture of supporting materials to bolster a thesis that addresses the DBQ question being asked. In order to group effectively, create at least three different groupings with two subgroups each.

When you group, group to respond to the prompt. Do not group just to bundle certain documents together. The best analogy would be you have a few different colored buckets, and you want to put a label over each bucket. Then you have a variety of different colored balls in which each color represents a document, and you want to put these balls into buckets. You can have documents that fall into more than one group, but the big picture tip to remember is to group in response to the prompt.

This is an absolute must. 33% of your DBQ grade comes from assessing your ability to group.

2. Assess POV with SOAPSTONE

SOAPSTONE helps you answer the question of why the person in the document made the piece of information at that time. Remember that SOAPSTONE is an acronym:

- S – Speaker

- O – Occasion

- A – Audience

- P – Purpose

- Tone – Tone

It answers the question of the motive behind the document and can help you engage with the documents more effectively.

3. S represents Speaker or Source

You want to begin by asking yourself who is the source of the document. Think about the background of this source. Where do they come from? What do they do? Are they male or female? What are their respective views on religion or philosophy? How old are they? Are they wealthy? Poor? Etc. Understanding the source of the text will help unlock its nature, and it will allow you to approach the reading with a specific angle in mind.

4. O stands for occasion

You want to ask yourself when the document was said, where was it said, and why it may have been created. You can also think of O as representative of origin. Analyzing the occasion or origin of a historical text will provide you with much-needed context, which is essential to decoding history. When you confront a text, immediately ask yourself what the occasion of the text is.

5. A represents audience

Think about who this person wanted to share this document with. What medium was the document originally delivered in? Is it delivered through an official document, or is it an artistic piece like a painting? The intention behind a piece is crucial to understanding its meaning. If you can figure out who the text was intended for, then you can begin to unpack what it is all about. The audience is crucial.

6. P stands for the purpose

After you’ve asked who the audience of the text is, begin asking, “why?” Think, “why did this person create this document?” or “why did they say this or that?” What is the main motive behind the document? Obviously, unpacking the purpose of a text is essential to understanding it as a whole, and, again, it serves as an essential step in the process of breaking down the text.

7. S is for the subject of the document.

Next is the subject. Every text addresses a broader or larger subject either implicitly or directly, and understanding this will help chunk your reading and make your writing more sophisticated. For instance, the Silk Road is a trading route, sure, but it is also more broadly about the rise of globalism and international relationships. WWI is, of course, a catastrophic war, but it’s also about the rise of technology, international discord, humanitarianism, and even masculinity. When you read a historical text, think, “what is this really about?”

8. TONE poses the question of what the tone of the document is.

This relates closely to the speaker. The tone is a general character or attitude of a place, piece of writing, or a situation. Writers create tone through a variety of ways but pay special attention to strong vocabulary words, key phrases, literary or rhetorical devices, mood words, and more elements of writing that generate the tone. Highlight or underline them. Think about how the creator of the document says certain things. Think about the connotations of certain words.

9. Explicitly state your analysis of POV

Your reader is not psychic. He or she cannot simply read your mind and understand exactly why you are rewriting a quotation by a person from a document. Be sure to explicitly state something along the lines of, “In document X, author states, “[quotation]”; the author may use this [x] tone because he wants to signify [y].” Another example would be, “The speaker’s belief that [speaker’s opinion] is made clear from his usage of particularly negative words such as [xyz].”

10. Be conscious of how you use data from charts and tables

Sometimes you’ll come across charts of statistics. If you do, ask yourself questions like where the data is coming from, how the data was collected, who released the data, etc. You essentially want to take a similar approach to SOAPSTONE with charts and tables. Data should be analyzed rather than merely summarized.

Notice how the prompt asks you to either “identify” or “explain.” If you choose to answer one of the questions with “identify,” you must go much further than simply identifying. You must move into the realm of “explain” and “analyze.”

11. Assess maps with a strategy in mind

When you come across maps, look at the corners and center of the map. Think about why the map may be oriented in a certain way. Think about if the title of the map or the legend reveals anything about the culture the map originates from. Think about how the map was created–where did the information for the map come from. Think about who the map was intended for.

12. Assess cultural pieces with SOAPSTONE in mind

If you come across more artistic documents such as literature, songs, editorials, or advertisements, you want to really think about the motive of why the piece of art or creative writing was made and who the document was intended for. What does that specific piece tell you about the time in which it was created?

13. Be careful using blanket statements

Just because a certain point of view is expressed in a document does not mean that POV applies to everyone from that historical area. One common problem students make is expressing one sentiment for a large group of people, events, or historical eras. Be aware that history can rarely be reduced to X = Y. A grey area persists. One easy way to avoid this pitfall is to be as specific as possible. Take a look at these examples from the 2019 exam:

Blanket statement: “During 1450 to 1750 the creation of the Mongol Empire changed the role of nomads in cultural exchange. Before the Mongols, nomads acted as traders who spread trade and culture along routes, but this changed during the Mongol Empire, nomads became the protectors who patrolled the trade routes to keep them safe.”

Notice how the writer paints nomadic tribes with too wide of a wide brush and does not discuss their trade with enough specificity.

Now here’s a more specific example:

“One development that changed the role that Central Asian Nomads played in cross-regional exchanges from the period 1450– 1750 C.E., as described in the passage, was the development of maritime technology because new modes of transportation across the ocean using boats and knowledge of monsoon winds allowed countries to trade and exchange ideas and goods across regions with less overland use, which diminished the importance of central Asian nomads in exchanging goods and ideas and cultures overland. An example of this includes European maritime empires such as Britain and Portugal, who navigated to Asia on sea in order to trade at trading posts. This sufficiently decreased central Asian nomads’ need to exchange goods along the Silk Road from Europe to Asia.”

Source: Chief Reader Report

Notice how specific the writer is when discussing the nomads’ trading.

14. Understand that bias will always exist

Even if you’re given data in the form of a table, there is bias in the data. Do not fall into the trap of thinking just because there are numbers it means the numbers are foolproof. Bias can and should be withdrawn from any and all sources.

Here’s an example of a bias historical statement: The Russian Revolution was initiated by an angry lower-class looking for revenge against a greedy ruling class.

While this may be somewhat true, notice how the words “angry” and “greedy” indicate particular moods toward these subjects from the author.

Instead, the statement should be written as “The Russian Revolution was initiated by Russia’s lower class against the ruling monarchy.

15. Be creative with introducing bias

Many students understand that they need to show their understanding that documents can be biased, but they go about it the wrong way. Rather than outright stating, “The document is biased because [x],” try, “In document A, the author is clearly influenced by [y] as he states, “[quotation].” See the difference? It’s subtle but makes a clear difference in how you demonstrate your understanding of bias.

16. Don’t forget to B.S. in your DBQ

No, no. It’s not what you’re thinking. By B.S., we mean to be specific. When you are discussing a certain revolutionary leader, an economic policy, a governmental act, or some other different aspect of AP® World History, be sure to specifically name your topics. Do not just generalize, but B.S.!

Here’s an example of a general statement: “ While both sides fought the Civil War over the issue of slavery, the North fought for moral reasons while the South fought to preserve its own institutions.”

And here’s one that’s more specific: “While both Northerners and Southerners believed they fought against tyranny and oppression, Northerners focused on the oppression of slaves while Southerners defended their own right to self-government.”

17. Leave yourself out of it

Do not refer to yourself when writing your DBQ essays! “I” has no place in these AP® essays. Academic essays need to remain professional and focused, and the introduction of “I” detracts from that tone. And the reader already knows that your essay is written from your perspective, so an “I” is just redundant.

Tips Submitted by AP® World History Teachers

Overall ap® world history tips, 1. use high polymer erasers.

When answering the multiple-choice scantron portion of the AP® World History test, use a high polymer eraser. It is the only eraser that will fully erase on a scantron. Amazon carries plenty for cheap. Thanks for the tip from Ms. J. at Boulder High School.

2. Stay ahead of your reading and when in doubt, read again

You are responsible for a huge amount of information when it comes to tackling AP® World History, so make sure you are responsible for some of it. Create a daily reading habit where you spend at least an hour per day digesting your AP® World History material. There is simply too much for you to try and cram. And you can’t leave all the work up to your instructor. It’s a team effort. Thanks for the tip from Mr. E at Tri-Central High.

3. Integrate video learning

A great way to really solidify your understanding of a concept is to watch supplementary videos on the topic. Crash Course offers a lot of great video content on World History, and Heimler’s History does as well. Then, after watching a video, read the topic again to truly master it. Thanks for the tip from Mr. D at Royal High School.

4. Practice with transparencies or a whiteboard

Use transparencies or a whiteboard to create overlay maps for each of the six periods of AP® World History at the start of each period so that you can see a visual of the regions of the world being focused on. History is perfect for big whiteboards because they allow you to draw out large maps, event chains, and more. Thanks for the tip from Ms. W at Riverbend High.

AP® World History Multiple-Choice Tips

1. read every word.

Oftentimes in AP® World History , many questions can be answered without specific historical knowledge. Many questions require critical thinking and attention to detail; the difference between a correct answer and an incorrect answer lies in just one or two words in the question or the answer. Be aware of answer choices like “none of the above” or “all of the above,” as either none or all of the questions must be correct or incorrect. Keep that totality in mind. Thanks for the tip from Mr. R. at Mandarin High.

2. Look at every answer option

Don’t go for the first “correct” answer; find the most “bulletproof” answer. The one you’d best be able to defend in a debate. Think of the “bulletproof” answer as an answer which can be tested and tested and tested but still holds up. Run this through your head while choosing an answer, and constantly reevaluate.

3. Annotate the text

Textbook reading is essential for success in AP® World History, but learn to annotate smarter, not harder. Be efficient in your reading and note-taking. Read, reduce, and reflect. To read – use sticky notes. Using post-its is a lifesaver – use different color stickies for different tasks (pink – summary, blue – questions, green – reflection, etc.) Reduce – go back and look at your sticky notes and see what you can reduce – decide what is truly essential material to know or question. Then reflect – why are the remaining sticky notes important? How will they help you not just understand the content, but also understand contextualization or causality or change over time? What does this information show you? Thanks for the tip from Ms. J at Legacy High.

AP® World History FRQ Tips

1. master writing a good thesis.

In order to write a good thesis, you want to make sure it properly addresses the whole question or prompt, effectively takes a position on the main topic, includes relevant historical context, and organize key standpoints. Heimler’s History has a good how-to guide on AP® World History thesis statements that’s certainly worth checking out. Thanks for the tip from Mr. G at Loganville High.

2. Tackle DBQs with SAD and BAD

With the DBQ, think about the S ummary, A uthor, and D ate & Context. Also, consider the B ias and A dditional D ocuments to verify the bias. Thanks for the tip from Mr. G at WHS.

Go through this prompt from the 2019 exam and notice how SAD and BAD work well. It is about totalitarian governments by Rudolph Rummel, a US political scientist, from 1994. Does it present any bias? Additional documents? SAD and BAD can.

3. Create a refined thesis in your conclusion

Do not simply blow off your conclusion paragraph. Think of the conclusion as the decorative bow that nicely holds the box together. By the time you finish your essay, you have a much more clear idea of how to answer the question. Take a minute and revisit the prompt and try to provide a much more explicit and comprehensive thesis than the one you provided in the beginning as your conclusion. This thesis statement is much more likely to give you the point for the thesis than the rushed thesis in the beginning. Thanks for the tip from Mr. R at Mission Hills High.

4. Relate back to the themes

Understanding 10,000 years of world history is hard. Knowing all the facts is darn near impossible. If you can use your facts/material and explain it within the context of one of the APWH themes, it makes it easier to process, understand, and apply. The themes are your friends. Thanks for the tip from Ms. J at Legacy High.

5. Look for the missing voice in DBQs

First, look for the missing voice. Who haven’t you heard from in the DBQ? Who’s voice would really help you answer the question more completely? Next, if there isn’t really a missing voice, what evidence do you have access to, that you would like to clarify? For example, if you have a document that says excessive taxation led to the fall of the Roman Empire, what other pieces of information would you like to have access to that would help you prove or disprove this statement? Maybe a chart that shows tax amounts from prior to the 3rd Century Crisis to the mid of the 3rd-century crisis? Thanks for the tip from Ms. J at Legacy High.

Wrapping Things Up: The Ultimate List of AP® World History Tips

Doing well in AP® World History comes down to recognizing patterns and trends in history, and familiarizing yourself with the nature of the test. Students often think the key to AP® history tests is memorizing every single fact of history, and the truth is you may be able to do that and get a 5, but the smart way of doing well on the test comes from understanding the reason why we study history in the first place.

By learning the underlying patterns that are tested on the exam, for example, how opinions towards women may have influenced the social or political landscape of the world during a certain time period, you can create more compelling theses and demonstrate to AP® readers a clear understanding of the bigger picture.

The bottom line is this: in order to ace this exam, you have to prepare. We offer tons of AP® World History practice questions , practice exams , AP® World History DBQs , and more. We recommend that you take a look at our extensive catalog, and develop a daily study routine. With this proper preparation, you will ace the exam!

Interested in a school license?

12 thoughts on “the ultimate list of ap® world history tips”.

When writing the DBQ, do not waste time quoting the documents; paraphrase and show the grader you understand what it’s saying.

Excellent tip, Rebecca!

Good tips for AP® World History.

Glad you enjoyed!

Thanks to AP® World History Teachers for these great tips.. keep it up.

Yes, they’re great!

An additional tip is to bring your own watch to the exam so that you can easily keep track of time.

Thanks for the addition!

My teacher submitted the first tip from teachers on high polymer erasers, and she is right. I only ever use these eraser for erasing anything in school and they work much better and last much longer than the stubby pink things on the end of pencils that people like to call “erasers.”

Thanks for sharing!

An extra tip is to convey your own particular watch to the exam so you can without much of a stretch monitor time.

Comments are closed.

Popular Posts

AP® Score Calculators

Simulate how different MCQ and FRQ scores translate into AP® scores

AP® Review Guides

The ultimate review guides for AP® subjects to help you plan and structure your prep.

Core Subject Review Guides

Review the most important topics in Physics and Algebra 1 .

SAT® Score Calculator

See how scores on each section impacts your overall SAT® score

ACT® Score Calculator

See how scores on each section impacts your overall ACT® score

Grammar Review Hub

Comprehensive review of grammar skills

AP® Posters

Download updated posters summarizing the main topics and structure for each AP® exam.

Find what you need to study

AP World Long Essay Question (LEQ) Overview

15 min read • may 10, 2022

Zaina Siddiqi

Exam simulation mode

Prep for the AP exam with questions that mimic the test!

Overview of the Long Essay Question (LEQ)

Section II of the AP Exam includes three Long Essay Question (LEQ) prompts. You will choose to write about just one of these.

The formatting of prompts varies somewhat between the AP Histories, though the rubric does not. In AP World History, the prompt includes a sentence that orients the writer to the time, place, and theme of the prompt topic, while prompts in AP US History and AP European History typically do not. However, the rubrics and scoring guidelines are the same for all Histories.

Your answer should include the following:

A valid thesis

A discussion of relevant historical context

Use of evidence supports your thesis

Use of a reasoning skill to organize and structure the argument

Complex understanding of the topic of the prompt

We will break down each of these aspects in the next section. For now, the gist is that you need to write an essay that answers the prompt, using evidence. You will need to structure and develop your essay using one of the course reasoning skills.

Many of the skills you need to write a successful LEQ essay are the same skills you will use on the DBQ. In fact, some of the rubric points are identical, so you can use a lot of the same strategies on both writing tasks!

You will have three choices of prompts for your LEQ. All three prompts will focus on the same reasoning skills, but the time periods will differ in each prompt. Prompt topics may span across time periods specified in the course outline, and the time period breakdowns for each prompt are as follows:

AP World History: Modern | AP US History | AP European History |

1200-1750 | 1491-1800 | 1450-1700 |

1450-1900 | 1800-1898 | 1648-1914 |

1750-2001 | 1890-2001 | 1815-2001 |

Writing time on the AP Exam includes both the Document Based Question (DBQ) and the (LEQ), but it is suggested that you spend 40 minutes completing the LEQ. You will need to plan and write your essay in that time.

A good breakdown would be 5 min. (planning) + 35 min. (writing) = 40 min.

The LEQ is scored on a rubric out of six points, and is weighted at 15% of your overall exam score. We’ll break down the rubric next.

How to Rock the LEQ: The Rubric

The LEQ is scored on a six point rubric, and each point can be earned independently. That means you can miss a point on something and still earn other points with the great parts of your essay.

Note: all of the examples in this section will be for this prompt from AP World History: Modern. You could use similar language, structure, or skills to write samples for prompts in AP US History or AP European History.

Let’s break down each rubric component...

What is it?

The thesis is a brief statement that introduces your argument or claim, and can be supported with evidence and analysis. This is where you answer the prompt.

Where do I write it?

This is the only element in the essay that has a required location. The thesis needs to be in your introduction or conclusion of your essay. It can be more than one sentence, but all of the sentences that make up your thesis must be consecutive in order to count.

How do I know if mine is good?

The most important part of your thesis is the claim , which is your answer to the prompt. The description the College-Board gives is that it should be “historically defensible,” which really means that your evidence must be plausible. On the LEQ, your thesis needs to be related topic of the prompt.

Your thesis should also establish your line of reasoning. Translation: address why or how something happened - think of this as the “because” to the implied “how/why” of the prompt. This sets up the framework for the body of your essay, since you can use the reasoning from your thesis to structure your body paragraph topics later.

The claim and reasoning are the required elements of the thesis. And if that’s all you can do, you’re in good shape to earn the point.

Going above-and-beyond to create a more complex thesis can help you in the long run, so it’s worth your time to try. One way to build in complexity to your thesis is to think about a counter-claim or alternate viewpoint that is relevant to your response. If you are using one of the course reasoning process to structure your essay (and you should!) think about using that framework for your thesis too.

In a causation essay, a complex argument addresses causes and effects.

In a comparison essay, a complex argument addresses similarities and differences.

In a continuity and change over time essay, a complex argument addresses change and continuity .

This counter-claim or alternate viewpoint can look like an “although” or “however” phrase in your thesis.

Powers in both land-based and maritime empires had to adapt their rule to accommodate diverse populations. However, in this era land-based empires were more focused on direct political control, while the maritime empires were more based on trade and economic development.

This thesis works because it clearly addresses the prompt (comparing land and maritime empires). It starts by addressing a similarity, and then specifies a clear difference with a line of reasoning to clarify the actions of the land vs. maritime empires.

Contextualization

Contextualization is a brief statement that lays out the broader historical background relevant to the prompt.