Paragraph Writing on Covid 19

Ai generator.

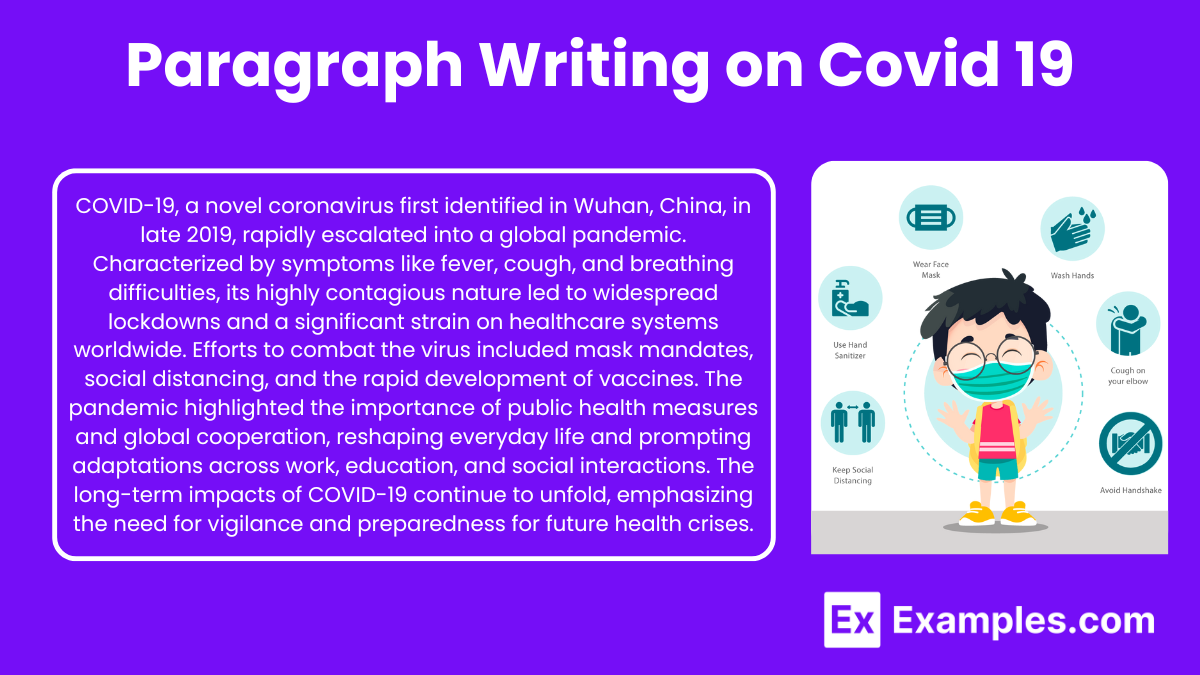

COVID-19, caused by the coronavirus, significantly impacted global health and daily life. Action plans focused on prevention, treatment, and vaccination. Some sought religious exemptions from mandates. A health thesis statement might explore the pandemic’s effects on mental health. The tone is informative and serious. This paragraph highlights the comprehensive response to COVID-19.

Checkout → Free Paragraph Writer Tool

Short Paragraph on Covid-19

Covid-19 is a global pandemic caused by the novel coronavirus. It has significantly impacted daily life, with governments worldwide implementing lockdowns, social distancing, and mask mandates to curb the virus’s spread. The pandemic has highlighted the importance of healthcare systems and the need for vaccines. It has also emphasized global cooperation and resilience in facing unprecedented challenges.

Medium Paragraph on Covid-19

Covid-19, caused by the novel coronavirus, has had a profound impact on the world since its outbreak. The pandemic led to widespread lockdowns, social distancing measures, and mandatory mask-wearing to prevent the virus’s spread. Healthcare systems were overwhelmed, emphasizing the need for robust medical infrastructure and preparedness. The development and distribution of vaccines became a global priority, showcasing the importance of scientific research and international cooperation. Economies faced significant challenges, with businesses closing and unemployment rates rising. Despite these hardships, the pandemic also brought communities together, highlighting resilience, adaptability, and the critical role of healthcare workers in combating the crisis.

Long Paragraph on Covid-19

Covid-19, caused by the novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2, emerged in late 2019 and rapidly spread across the globe, leading to an unprecedented pandemic. The virus’s high transmission rate prompted governments worldwide to implement stringent measures such as lockdowns, social distancing, and mask mandates to control its spread. These measures, while necessary, significantly disrupted daily life, impacting economies, education, and social interactions. Healthcare systems were strained, underscoring the need for better preparedness and robust medical infrastructure. The rapid development and global distribution of vaccines became a beacon of hope, demonstrating the power of scientific collaboration and innovation. The pandemic also highlighted the disparities in healthcare access and the importance of public health initiatives. Despite the immense challenges, communities showed resilience and adaptability, finding new ways to connect and support each other. The dedication of healthcare workers and the collective effort to combat the virus underscored the importance of global solidarity. Covid-19 has reshaped our world, teaching valuable lessons about preparedness, the significance of science, and the strength of human resilience in the face of adversity.

Tone-wise Paragraph Examples on Covid-19

Formal tone.

Covid-19, caused by the novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2, represents an unprecedented global health crisis. The pandemic has led to widespread implementation of public health measures such as lockdowns, social distancing, and mandatory mask usage to mitigate the virus’s transmission. Healthcare systems worldwide faced significant strain, highlighting the critical need for robust medical infrastructure and emergency preparedness. The rapid development and distribution of vaccines have been pivotal in controlling the spread of the virus, underscoring the importance of scientific research and international cooperation. The pandemic has also revealed existing disparities in healthcare access and emphasized the necessity of coordinated global public health strategies to effectively manage such crises.

Informal Tone

Covid-19 has really shaken things up since it started spreading in late 2019. Caused by a new coronavirus, it led to lockdowns, social distancing, and everyone wearing masks. Daily life changed a lot, with schools and businesses shutting down, and everyone trying to stay safe. The healthcare system was hit hard, showing us just how important it is to be prepared. Vaccines were developed super quickly, giving us hope to get back to normal. Even though it was tough, people came together, supported each other, and adapted to the new normal. Covid-19 taught us a lot about resilience and the importance of healthcare.

Persuasive Tone

Covid-19, caused by the novel coronavirus, has highlighted the urgent need for better healthcare systems and global cooperation. The pandemic led to widespread lockdowns, social distancing, and mask mandates, disrupting daily life and economies. Our healthcare systems were overwhelmed, underscoring the critical need for robust medical infrastructure. The rapid development of vaccines showcased the power of scientific research and international collaboration. Now, more than ever, it is crucial to support and strengthen our healthcare systems, invest in scientific research, and promote global cooperation to ensure we are better prepared for future health crises. Let’s learn from this pandemic and build a stronger, healthier world together.

Reflective Tone

Reflecting on the impact of Covid-19, it’s clear that the pandemic has reshaped our world in profound ways. The novel coronavirus led to unprecedented global lockdowns, social distancing, and mask mandates, dramatically altering daily life. Our healthcare systems were tested like never before, revealing both strengths and weaknesses. The rapid development and distribution of vaccines highlighted the importance of scientific innovation and international cooperation. Amid the challenges, communities showed remarkable resilience and adaptability, finding new ways to connect and support one another. Covid-19 has taught us valuable lessons about preparedness, the significance of healthcare, and the power of human resilience in the face of adversity.

Inspirational Tone

Covid-19 has been a challenging journey, but it has also shown the incredible strength and resilience of humanity. The novel coronavirus led to global lockdowns, social distancing, and mask mandates, changing our daily lives dramatically. Despite these hardships, the rapid development and distribution of vaccines brought hope and showcased the power of scientific innovation and global cooperation. Communities came together, supporting each other and adapting to new realities. Healthcare workers became heroes, showing unparalleled dedication and bravery. Covid-19 has taught us the importance of unity, resilience, and the ability to overcome even the toughest challenges. Together, we can build a brighter, healthier future.

Optimistic Tone

Covid-19, caused by the novel coronavirus, brought significant challenges, but it also highlighted the resilience and adaptability of people worldwide. The pandemic led to lockdowns, social distancing, and mask-wearing, changing our daily routines. Despite these difficulties, the rapid development of vaccines brought hope and demonstrated the power of scientific progress. Communities came together, supporting one another and finding new ways to connect. Healthcare workers showed incredible dedication, and the world witnessed the strength of human spirit. Covid-19 has been a tough journey, but it also reinforced our ability to overcome adversity and work towards a healthier, more connected future.

Urgent Tone

The Covid-19 pandemic, caused by the novel coronavirus, demands our immediate attention and action. Since its outbreak, the virus has led to widespread lockdowns, social distancing, and mandatory mask usage, significantly disrupting daily life. Healthcare systems have been overwhelmed, highlighting the urgent need for better preparedness and robust medical infrastructure. The rapid development of vaccines has been crucial, but we must continue to prioritize public health measures and global cooperation to combat this crisis. Now is the time to invest in healthcare, support scientific research, and work together to overcome this pandemic. Immediate action is essential to protect lives and prevent further devastation.

Word Count-wise Paragraph Examples on Covid-19

Covid-19, caused by the novel coronavirus, has had a profound impact on the world since its outbreak. The pandemic led to widespread lockdowns, social distancing measures, and mandatory mask-wearing to prevent the virus’s spread. Healthcare systems were overwhelmed, emphasizing the need for robust medical infrastructure and preparedness. The development and distribution of vaccines became a global priority, showcasing the importance of scientific research and international cooperation. Economies faced significant challenges, with businesses closing and unemployment rates rising. Despite these hardships, the pandemic also brought communities together, highlighting resilience, adaptability, and the critical role of healthcare workers in combating the crisis. The rapid development and distribution of vaccines became a beacon of hope, demonstrating the power of scientific collaboration and innovation.

Covid-19, caused by the novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2, emerged in late 2019 and rapidly spread across the globe, leading to an unprecedented pandemic. The virus’s high transmission rate prompted governments worldwide to implement stringent measures such as lockdowns, social distancing, and mask mandates to control its spread. These measures, while necessary, significantly disrupted daily life, impacting economies, education, and social interactions. Healthcare systems were strained, underscoring the need for better preparedness and robust medical infrastructure. The rapid development and global distribution of vaccines became a beacon of hope, demonstrating the power of scientific collaboration and innovation. The pandemic also highlighted the disparities in healthcare access and the importance of public health initiatives. Despite the immense challenges, communities showed resilience and adaptability, finding new ways to connect and support each other.

Covid-19, caused by the novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2, emerged in late 2019 and rapidly spread across the globe, leading to an unprecedented pandemic. The virus’s high transmission rate prompted governments worldwide to implement stringent measures such as lockdowns, social distancing, and mask mandates to control its spread. These measures, while necessary, significantly disrupted daily life, impacting economies, education, and social interactions. Healthcare systems were strained, underscoring the need for better preparedness and robust medical infrastructure. The rapid development and global distribution of vaccines became a beacon of hope, demonstrating the power of scientific collaboration and innovation. The pandemic also highlighted the disparities in healthcare access and the importance of public health initiatives. Despite the immense challenges, communities showed resilience and adaptability, finding new ways to connect and support each other. The dedication of healthcare workers and the collective effort to combat the virus underscored the importance of global solidarity. Covid-19 has reshaped our world, teaching valuable lessons about preparedness, the significance of science, and the strength of human resilience in the face of adversity. The pandemic emphasized the need for robust healthcare systems, scientific innovation, and global cooperation. Despite the challenges, the collective resilience and adaptability of people worldwide have shown the strength of the human spirit in overcoming adversity.

Text prompt

- Instructive

- Professional

10 Examples of Public speaking

20 Examples of Gas lighting

45,000+ students realised their study abroad dream with us. Take the first step today

Meet top uk universities from the comfort of your home, here’s your new year gift, one app for all your, study abroad needs, start your journey, track your progress, grow with the community and so much more.

Verification Code

An OTP has been sent to your registered mobile no. Please verify

Thanks for your comment !

Our team will review it before it's shown to our readers.

- School Education /

Essay On Covid-19: 100, 200 and 300 Words

- Updated on

- Apr 30, 2024

COVID-19, also known as the Coronavirus, is a global pandemic that has affected people all around the world. It first emerged in a lab in Wuhan, China, in late 2019 and quickly spread to countries around the world. This virus was reportedly caused by SARS-CoV-2. Since then, it has spread rapidly to many countries, causing widespread illness and impacting our lives in numerous ways. This blog talks about the details of this virus and also drafts an essay on COVID-19 in 100, 200 and 300 words for students and professionals.

Table of Contents

- 1 Essay On COVID-19 in English 100 Words

- 2 Essay On COVID-19 in 200 Words

- 3 Essay On COVID-19 in 300 Words

- 4 Short Essay on Covid-19

Essay On COVID-19 in English 100 Words

COVID-19, also known as the coronavirus, is a global pandemic. It started in late 2019 and has affected people all around the world. The virus spreads very quickly through someone’s sneeze and respiratory issues.

COVID-19 has had a significant impact on our lives, with lockdowns, travel restrictions, and changes in daily routines. To prevent the spread of COVID-19, we should wear masks, practice social distancing, and wash our hands frequently.

People should follow social distancing and other safety guidelines and also learn the tricks to be safe stay healthy and work the whole challenging time.

Also Read: National Safe Motherhood Day 2023

Essay On COVID-19 in 200 Words

COVID-19 also known as coronavirus, became a global health crisis in early 2020 and impacted mankind around the world. This virus is said to have originated in Wuhan, China in late 2019. It belongs to the coronavirus family and causes flu-like symptoms. It impacted the healthcare systems, economies and the daily lives of people all over the world.

The most crucial aspect of COVID-19 is its highly spreadable nature. It is a communicable disease that spreads through various means such as coughs from infected persons, sneezes and communication. Due to its easy transmission leading to its outbreaks, there were many measures taken by the government from all over the world such as Lockdowns, Social Distancing, and wearing masks.

There are many changes throughout the economic systems, and also in daily routines. Other measures such as schools opting for Online schooling, Remote work options available and restrictions on travel throughout the country and internationally. Subsequently, to cure and top its outbreak, the government started its vaccine campaigns, and other preventive measures.

In conclusion, COVID-19 tested the patience and resilience of the mankind. This pandemic has taught people the importance of patience, effort and humbleness.

Also Read : Essay on My Best Friend

Essay On COVID-19 in 300 Words

COVID-19, also known as the coronavirus, is a serious and contagious disease that has affected people worldwide. It was first discovered in late 2019 in Cina and then got spread in the whole world. It had a major impact on people’s life, their school, work and daily lives.

COVID-19 is primarily transmitted from person to person through respiratory droplets produced and through sneezes, and coughs of an infected person. It can spread to thousands of people because of its highly contagious nature. To cure the widespread of this virus, there are thousands of steps taken by the people and the government.

Wearing masks is one of the essential precautions to prevent the virus from spreading. Social distancing is another vital practice, which involves maintaining a safe distance from others to minimize close contact.

Very frequent handwashing is also very important to stop the spread of this virus. Proper hand hygiene can help remove any potential virus particles from our hands, reducing the risk of infection.

In conclusion, the Coronavirus has changed people’s perspective on living. It has also changed people’s way of interacting and how to live. To deal with this virus, it is very important to follow the important guidelines such as masks, social distancing and techniques to wash your hands. Getting vaccinated is also very important to go back to normal life and cure this virus completely.

Also Read: Essay on Abortion in English in 650 Words

Short Essay on Covid-19

Please find below a sample of a short essay on Covid-19 for school students:

Also Read: Essay on Women’s Day in 200 and 500 words

to write an essay on COVID-19, understand your word limit and make sure to cover all the stages and symptoms of this disease. You need to highlight all the challenges and impacts of COVID-19. Do not forget to conclude your essay with positive precautionary measures.

Writing an essay on COVID-19 in 200 words requires you to cover all the challenges, impacts and precautions of this disease. You don’t need to describe all of these factors in brief, but make sure to add as many options as your word limit allows.

The full form for COVID-19 is Corona Virus Disease of 2019.

Related Reads

Hence, we hope that this blog has assisted you in comprehending with an essay on COVID-19. For more information on such interesting topics, visit our essay writing page and follow Leverage Edu.

Simran Popli

An avid writer and a creative person. With an experience of 1.5 years content writing, Simran has worked with different areas. From medical to working in a marketing agency with different clients to Ed-tech company, the journey has been diverse. Creative, vivacious and patient are the words that describe her personality.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Contact no. *

Connect With Us

45,000+ students realised their study abroad dream with us. take the first step today..

Resend OTP in

Need help with?

Study abroad.

UK, Canada, US & More

IELTS, GRE, GMAT & More

Scholarship, Loans & Forex

Country Preference

New Zealand

Which English test are you planning to take?

Which academic test are you planning to take.

Not Sure yet

When are you planning to take the exam?

Already booked my exam slot

Within 2 Months

Want to learn about the test

Which Degree do you wish to pursue?

When do you want to start studying abroad.

January 2024

September 2024

What is your budget to study abroad?

How would you describe this article ?

Please rate this article

We would like to hear more.

Have something on your mind?

Make your study abroad dream a reality in January 2022 with

India's Biggest Virtual University Fair

Essex Direct Admission Day

Why attend .

Don't Miss Out

- CBSE Class 10th

- CBSE Class 12th

- UP Board 10th

- UP Board 12th

- Bihar Board 10th

- Bihar Board 12th

- Top Schools in India

- Top Schools in Delhi

- Top Schools in Mumbai

- Top Schools in Chennai

- Top Schools in Hyderabad

- Top Schools in Kolkata

- Top Schools in Pune

- Top Schools in Bangalore

Products & Resources

- JEE Main Knockout April

- Free Sample Papers

- Free Ebooks

- NCERT Notes

- NCERT Syllabus

- NCERT Books

- RD Sharma Solutions

- Navodaya Vidyalaya Admission 2024-25

- NCERT Solutions

- NCERT Solutions for Class 12

- NCERT Solutions for Class 11

- NCERT solutions for Class 10

- NCERT solutions for Class 9

- NCERT solutions for Class 8

- NCERT Solutions for Class 7

- JEE Main 2024

- MHT CET 2024

- JEE Advanced 2024

- BITSAT 2024

- View All Engineering Exams

- Colleges Accepting B.Tech Applications

- Top Engineering Colleges in India

- Engineering Colleges in India

- Engineering Colleges in Tamil Nadu

- Engineering Colleges Accepting JEE Main

- Top IITs in India

- Top NITs in India

- Top IIITs in India

- JEE Main College Predictor

- JEE Main Rank Predictor

- MHT CET College Predictor

- AP EAMCET College Predictor

- GATE College Predictor

- KCET College Predictor

- JEE Advanced College Predictor

- View All College Predictors

- JEE Advanced Cutoff

- JEE Main Cutoff

- MHT CET Result 2024

- JEE Advanced Result

- Download E-Books and Sample Papers

- Compare Colleges

- B.Tech College Applications

- AP EAMCET Result 2024

- MAH MBA CET Exam

- View All Management Exams

Colleges & Courses

- MBA College Admissions

- MBA Colleges in India

- Top IIMs Colleges in India

- Top Online MBA Colleges in India

- MBA Colleges Accepting XAT Score

- BBA Colleges in India

- XAT College Predictor 2024

- SNAP College Predictor

- NMAT College Predictor

- MAT College Predictor 2024

- CMAT College Predictor 2024

- CAT Percentile Predictor 2024

- CAT 2024 College Predictor

- Top MBA Entrance Exams 2024

- AP ICET Counselling 2024

- GD Topics for MBA

- CAT Exam Date 2024

- Download Helpful Ebooks

- List of Popular Branches

- QnA - Get answers to your doubts

- IIM Fees Structure

- AIIMS Nursing

- Top Medical Colleges in India

- Top Medical Colleges in India accepting NEET Score

- Medical Colleges accepting NEET

- List of Medical Colleges in India

- List of AIIMS Colleges In India

- Medical Colleges in Maharashtra

- Medical Colleges in India Accepting NEET PG

- NEET College Predictor

- NEET PG College Predictor

- NEET MDS College Predictor

- NEET Rank Predictor

- DNB PDCET College Predictor

- NEET Result 2024

- NEET Asnwer Key 2024

- NEET Cut off

- NEET Online Preparation

- Download Helpful E-books

- Colleges Accepting Admissions

- Top Law Colleges in India

- Law College Accepting CLAT Score

- List of Law Colleges in India

- Top Law Colleges in Delhi

- Top NLUs Colleges in India

- Top Law Colleges in Chandigarh

- Top Law Collages in Lucknow

Predictors & E-Books

- CLAT College Predictor

- MHCET Law ( 5 Year L.L.B) College Predictor

- AILET College Predictor

- Sample Papers

- Compare Law Collages

- Careers360 Youtube Channel

- CLAT Syllabus 2025

- CLAT Previous Year Question Paper

- NID DAT Exam

- Pearl Academy Exam

Predictors & Articles

- NIFT College Predictor

- UCEED College Predictor

- NID DAT College Predictor

- NID DAT Syllabus 2025

- NID DAT 2025

- Design Colleges in India

- Top NIFT Colleges in India

- Fashion Design Colleges in India

- Top Interior Design Colleges in India

- Top Graphic Designing Colleges in India

- Fashion Design Colleges in Delhi

- Fashion Design Colleges in Mumbai

- Top Interior Design Colleges in Bangalore

- NIFT Result 2024

- NIFT Fees Structure

- NIFT Syllabus 2025

- Free Design E-books

- List of Branches

- Careers360 Youtube channel

- IPU CET BJMC

- JMI Mass Communication Entrance Exam

- IIMC Entrance Exam

- Media & Journalism colleges in Delhi

- Media & Journalism colleges in Bangalore

- Media & Journalism colleges in Mumbai

- List of Media & Journalism Colleges in India

- CA Intermediate

- CA Foundation

- CS Executive

- CS Professional

- Difference between CA and CS

- Difference between CA and CMA

- CA Full form

- CMA Full form

- CS Full form

- CA Salary In India

Top Courses & Careers

- Bachelor of Commerce (B.Com)

- Master of Commerce (M.Com)

- Company Secretary

- Cost Accountant

- Charted Accountant

- Credit Manager

- Financial Advisor

- Top Commerce Colleges in India

- Top Government Commerce Colleges in India

- Top Private Commerce Colleges in India

- Top M.Com Colleges in Mumbai

- Top B.Com Colleges in India

- IT Colleges in Tamil Nadu

- IT Colleges in Uttar Pradesh

- MCA Colleges in India

- BCA Colleges in India

Quick Links

- Information Technology Courses

- Programming Courses

- Web Development Courses

- Data Analytics Courses

- Big Data Analytics Courses

- RUHS Pharmacy Admission Test

- Top Pharmacy Colleges in India

- Pharmacy Colleges in Pune

- Pharmacy Colleges in Mumbai

- Colleges Accepting GPAT Score

- Pharmacy Colleges in Lucknow

- List of Pharmacy Colleges in Nagpur

- GPAT Result

- GPAT 2024 Admit Card

- GPAT Question Papers

- NCHMCT JEE 2024

- Mah BHMCT CET

- Top Hotel Management Colleges in Delhi

- Top Hotel Management Colleges in Hyderabad

- Top Hotel Management Colleges in Mumbai

- Top Hotel Management Colleges in Tamil Nadu

- Top Hotel Management Colleges in Maharashtra

- B.Sc Hotel Management

- Hotel Management

- Diploma in Hotel Management and Catering Technology

Diploma Colleges

- Top Diploma Colleges in Maharashtra

- UPSC IAS 2024

- SSC CGL 2024

- IBPS RRB 2024

- Previous Year Sample Papers

- Free Competition E-books

- Sarkari Result

- QnA- Get your doubts answered

- UPSC Previous Year Sample Papers

- CTET Previous Year Sample Papers

- SBI Clerk Previous Year Sample Papers

- NDA Previous Year Sample Papers

Upcoming Events

- NDA Application Form 2024

- UPSC IAS Application Form 2024

- CDS Application Form 2024

- CTET Admit card 2024

- HP TET Result 2023

- SSC GD Constable Admit Card 2024

- UPTET Notification 2024

- SBI Clerk Result 2024

Other Exams

- SSC CHSL 2024

- UP PCS 2024

- UGC NET 2024

- RRB NTPC 2024

- IBPS PO 2024

- IBPS Clerk 2024

- IBPS SO 2024

- Top University in USA

- Top University in Canada

- Top University in Ireland

- Top Universities in UK

- Top Universities in Australia

- Best MBA Colleges in Abroad

- Business Management Studies Colleges

Top Countries

- Study in USA

- Study in UK

- Study in Canada

- Study in Australia

- Study in Ireland

- Study in Germany

- Study in China

- Study in Europe

Student Visas

- Student Visa Canada

- Student Visa UK

- Student Visa USA

- Student Visa Australia

- Student Visa Germany

- Student Visa New Zealand

- Student Visa Ireland

- CUET PG 2024

- IGNOU B.Ed Admission 2024

- DU Admission 2024

- UP B.Ed JEE 2024

- LPU NEST 2024

- IIT JAM 2024

- IGNOU Online Admission 2024

- Universities in India

- Top Universities in India 2024

- Top Colleges in India

- Top Universities in Uttar Pradesh 2024

- Top Universities in Bihar

- Top Universities in Madhya Pradesh 2024

- Top Universities in Tamil Nadu 2024

- Central Universities in India

- CUET DU Cut off 2024

- IGNOU Date Sheet

- CUET DU CSAS Portal 2024

- CUET Response Sheet 2024

- CUET Result 2024

- CUET Participating Universities 2024

- CUET Previous Year Question Paper

- CUET Syllabus 2024 for Science Students

- E-Books and Sample Papers

- CUET Exam Pattern 2024

- CUET Exam Date 2024

- CUET Cut Off 2024

- CUET Exam Analysis 2024

- IGNOU Exam Form 2024

- CUET PG Counselling 2024

- CUET Answer Key 2024

Engineering Preparation

- Knockout JEE Main 2024

- Test Series JEE Main 2024

- JEE Main 2024 Rank Booster

Medical Preparation

- Knockout NEET 2024

- Test Series NEET 2024

- Rank Booster NEET 2024

Online Courses

- JEE Main One Month Course

- NEET One Month Course

- IBSAT Free Mock Tests

- IIT JEE Foundation Course

- Knockout BITSAT 2024

- Career Guidance Tool

Top Streams

- IT & Software Certification Courses

- Engineering and Architecture Certification Courses

- Programming And Development Certification Courses

- Business and Management Certification Courses

- Marketing Certification Courses

- Health and Fitness Certification Courses

- Design Certification Courses

Specializations

- Digital Marketing Certification Courses

- Cyber Security Certification Courses

- Artificial Intelligence Certification Courses

- Business Analytics Certification Courses

- Data Science Certification Courses

- Cloud Computing Certification Courses

- Machine Learning Certification Courses

- View All Certification Courses

- UG Degree Courses

- PG Degree Courses

- Short Term Courses

- Free Courses

- Online Degrees and Diplomas

- Compare Courses

Top Providers

- Coursera Courses

- Udemy Courses

- Edx Courses

- Swayam Courses

- upGrad Courses

- Simplilearn Courses

- Great Learning Courses

Covid 19 Essay in English

Essay on Covid -19: In a very short amount of time, coronavirus has spread globally. It has had an enormous impact on people's lives, economy, and societies all around the world, affecting every country. Governments have had to take severe measures to try and contain the pandemic. The virus has altered our way of life in many ways, including its effects on our health and our economy. Here are a few sample essays on ‘CoronaVirus’.

100 Words Essay on Covid 19

200 words essay on covid 19, 500 words essay on covid 19.

COVID-19 or Corona Virus is a novel coronavirus that was first identified in 2019. It is similar to other coronaviruses, such as SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV, but it is more contagious and has caused more severe respiratory illness in people who have been infected. The novel coronavirus became a global pandemic in a very short period of time. It has affected lives, economies and societies across the world, leaving no country untouched. The virus has caused governments to take drastic measures to try and contain it. From health implications to economic and social ramifications, COVID-19 impacted every part of our lives. It has been more than 2 years since the pandemic hit and the world is still recovering from its effects.

Since the outbreak of COVID-19, the world has been impacted in a number of ways. For one, the global economy has taken a hit as businesses have been forced to close their doors. This has led to widespread job losses and an increase in poverty levels around the world. Additionally, countries have had to impose strict travel restrictions in an attempt to contain the virus, which has resulted in a decrease in tourism and international trade. Furthermore, the pandemic has put immense pressure on healthcare systems globally, as hospitals have been overwhelmed with patients suffering from the virus. Lastly, the outbreak has led to a general feeling of anxiety and uncertainty, as people are fearful of contracting the disease.

My Experience of COVID-19

I still remember how abruptly colleges and schools shut down in March 2020. I was a college student at that time and I was under the impression that everything would go back to normal in a few weeks. I could not have been more wrong. The situation only got worse every week and the government had to impose a lockdown. There were so many restrictions in place. For example, we had to wear face masks whenever we left the house, and we could only go out for essential errands. Restaurants and shops were only allowed to operate at take-out capacity, and many businesses were shut down.

In the current scenario, coronavirus is dominating all aspects of our lives. The coronavirus pandemic has wreaked havoc upon people’s lives, altering the way we live and work in a very short amount of time. It has revolutionised how we think about health care, education, and even social interaction. This virus has had long-term implications on our society, including its impact on mental health, economic stability, and global politics. But we as individuals can help to mitigate these effects by taking personal responsibility to protect themselves and those around them from infection.

Effects of CoronaVirus on Education

The outbreak of coronavirus has had a significant impact on education systems around the world. In China, where the virus originated, all schools and universities were closed for several weeks in an effort to contain the spread of the disease. Many other countries have followed suit, either closing schools altogether or suspending classes for a period of time.

This has resulted in a major disruption to the education of millions of students. Some have been able to continue their studies online, but many have not had access to the internet or have not been able to afford the costs associated with it. This has led to a widening of the digital divide between those who can afford to continue their education online and those who cannot.

The closure of schools has also had a negative impact on the mental health of many students. With no face-to-face contact with friends and teachers, some students have felt isolated and anxious. This has been compounded by the worry and uncertainty surrounding the virus itself.

The situation with coronavirus has improved and schools have been reopened but students are still catching up with the gap of 2 years that the pandemic created. In the meantime, governments and educational institutions are working together to find ways to support students and ensure that they are able to continue their education despite these difficult circumstances.

Effects of CoronaVirus on Economy

The outbreak of the coronavirus has had a significant impact on the global economy. The virus, which originated in China, has spread to over two hundred countries, resulting in widespread panic and a decrease in global trade. As a result of the outbreak, many businesses have been forced to close their doors, leading to a rise in unemployment. In addition, the stock market has taken a severe hit.

Effects of CoronaVirus on Health

The effects that coronavirus has on one's health are still being studied and researched as the virus continues to spread throughout the world. However, some of the potential effects on health that have been observed thus far include respiratory problems, fever, and coughing. In severe cases, pneumonia, kidney failure, and death can occur. It is important for people who think they may have been exposed to the virus to seek medical attention immediately so that they can be treated properly and avoid any serious complications. There is no specific cure or treatment for coronavirus at this time, but there are ways to help ease symptoms and prevent the virus from spreading.

Applications for Admissions are open.

Aakash iACST Scholarship Test 2024

Get up to 90% scholarship on NEET, JEE & Foundation courses

ALLEN Digital Scholarship Admission Test (ADSAT)

Register FREE for ALLEN Digital Scholarship Admission Test (ADSAT)

JEE Main Important Physics formulas

As per latest 2024 syllabus. Physics formulas, equations, & laws of class 11 & 12th chapters

PW JEE Coaching

Enrol in PW Vidyapeeth center for JEE coaching

JEE Main Important Chemistry formulas

As per latest 2024 syllabus. Chemistry formulas, equations, & laws of class 11 & 12th chapters

ALLEN JEE Exam Prep

Start your JEE preparation with ALLEN

Download Careers360 App's

Regular exam updates, QnA, Predictors, College Applications & E-books now on your Mobile

Certifications

We Appeared in

Writing about COVID-19 in a college admission essay

by: Venkates Swaminathan | Updated: September 14, 2020

Print article

For students applying to college using the CommonApp, there are several different places where students and counselors can address the pandemic’s impact. The different sections have differing goals. You must understand how to use each section for its appropriate use.

The CommonApp COVID-19 question

First, the CommonApp this year has an additional question specifically about COVID-19 :

Community disruptions such as COVID-19 and natural disasters can have deep and long-lasting impacts. If you need it, this space is yours to describe those impacts. Colleges care about the effects on your health and well-being, safety, family circumstances, future plans, and education, including access to reliable technology and quiet study spaces. Please use this space to describe how these events have impacted you.

This question seeks to understand the adversity that students may have had to face due to the pandemic, the move to online education, or the shelter-in-place rules. You don’t have to answer this question if the impact on you wasn’t particularly severe. Some examples of things students should discuss include:

- The student or a family member had COVID-19 or suffered other illnesses due to confinement during the pandemic.

- The candidate had to deal with personal or family issues, such as abusive living situations or other safety concerns

- The student suffered from a lack of internet access and other online learning challenges.

- Students who dealt with problems registering for or taking standardized tests and AP exams.

Jeff Schiffman of the Tulane University admissions office has a blog about this section. He recommends students ask themselves several questions as they go about answering this section:

- Are my experiences different from others’?

- Are there noticeable changes on my transcript?

- Am I aware of my privilege?

- Am I specific? Am I explaining rather than complaining?

- Is this information being included elsewhere on my application?

If you do answer this section, be brief and to-the-point.

Counselor recommendations and school profiles

Second, counselors will, in their counselor forms and school profiles on the CommonApp, address how the school handled the pandemic and how it might have affected students, specifically as it relates to:

- Grading scales and policies

- Graduation requirements

- Instructional methods

- Schedules and course offerings

- Testing requirements

- Your academic calendar

- Other extenuating circumstances

Students don’t have to mention these matters in their application unless something unusual happened.

Writing about COVID-19 in your main essay

Write about your experiences during the pandemic in your main college essay if your experience is personal, relevant, and the most important thing to discuss in your college admission essay. That you had to stay home and study online isn’t sufficient, as millions of other students faced the same situation. But sometimes, it can be appropriate and helpful to write about something related to the pandemic in your essay. For example:

- One student developed a website for a local comic book store. The store might not have survived without the ability for people to order comic books online. The student had a long-standing relationship with the store, and it was an institution that created a community for students who otherwise felt left out.

- One student started a YouTube channel to help other students with academic subjects he was very familiar with and began tutoring others.

- Some students used their extra time that was the result of the stay-at-home orders to take online courses pursuing topics they are genuinely interested in or developing new interests, like a foreign language or music.

Experiences like this can be good topics for the CommonApp essay as long as they reflect something genuinely important about the student. For many students whose lives have been shaped by this pandemic, it can be a critical part of their college application.

Want more? Read 6 ways to improve a college essay , What the &%$! should I write about in my college essay , and Just how important is a college admissions essay? .

Homes Nearby

Homes for rent and sale near schools

How our schools are (and aren't) addressing race

The truth about homework in America

What should I write my college essay about?

What the #%@!& should I write about in my college essay?

Yes! Sign me up for updates relevant to my child's grade.

Please enter a valid email address

Thank you for signing up!

Server Issue: Please try again later. Sorry for the inconvenience

- Today's news

- Reviews and deals

- Climate change

- 2024 election

- Fall allergies

- Health news

- Mental health

- Sexual health

- Family health

- So mini ways

- Unapologetically

- Buying guides

Entertainment

- How to Watch

- My watchlist

- Stock market

- Biden economy

- Personal finance

- Stocks: most active

- Stocks: gainers

- Stocks: losers

- Trending tickers

- World indices

- US Treasury bonds

- Top mutual funds

- Highest open interest

- Highest implied volatility

- Currency converter

- Basic materials

- Communication services

- Consumer cyclical

- Consumer defensive

- Financial services

- Industrials

- Real estate

- Mutual funds

- Credit cards

- Balance transfer cards

- Cash back cards

- Rewards cards

- Travel cards

- Online checking

- High-yield savings

- Money market

- Home equity loan

- Personal loans

- Student loans

- Options pit

- Fantasy football

- Pro Pick 'Em

- College Pick 'Em

- Fantasy baseball

- Fantasy hockey

- Fantasy basketball

- Download the app

- Daily fantasy

- Scores and schedules

- GameChannel

- World Baseball Classic

- Premier League

- CONCACAF League

- Champions League

- Motorsports

- Horse racing

- Newsletters

New on Yahoo

- Privacy Dashboard

How to Write About the Impact of the Coronavirus in a College Essay

The global impact of COVID-19, the disease caused by the novel coronavirus, means colleges and prospective students alike are in for an admissions cycle like no other. Both face unprecedented challenges and questions as they grapple with their respective futures amid the ongoing fallout of the pandemic.

Colleges must examine applicants without the aid of standardized test scores for many -- a factor that prompted many schools to go test-optional for now . Even grades, a significant component of a college application, may be hard to interpret with some high schools adopting pass-fail classes last spring due to the pandemic. Major college admissions factors are suddenly skewed.

"I can't help but think other (admissions) factors are going to matter more," says Ethan Sawyer, founder of the College Essay Guy, a website that offers free and paid essay-writing resources.

College essays and letters of recommendation , Sawyer says, are likely to carry more weight than ever in this admissions cycle. And many essays will likely focus on how the pandemic shaped students' lives throughout an often tumultuous 2020.

[ Read: How to Write a College Essay. ]

But before writing a college essay focused on the coronavirus, students should explore whether it's the best topic for them.

Writing About COVID-19 for a College Application

Much of daily life has been colored by the coronavirus. Virtual learning is the norm at many colleges and high schools, many extracurriculars have vanished and social lives have stalled for students complying with measures to stop the spread of COVID-19.

"For some young people, the pandemic took away what they envisioned as their senior year," says Robert Alexander, dean of admissions, financial aid and enrollment management at the University of Rochester in New York. "Maybe that's a spot on a varsity athletic team or the lead role in the fall play. And it's OK for them to mourn what should have been and what they feel like they lost, but more important is how are they making the most of the opportunities they do have?"

That question, Alexander says, is what colleges want answered if students choose to address COVID-19 in their college essay.

But the question of whether a student should write about the coronavirus is tricky. The answer depends largely on the student.

"In general, I don't think students should write about COVID-19 in their main personal statement for their application," Robin Miller, master college admissions counselor at IvyWise, a college counseling company, wrote in an email.

"Certainly, there may be exceptions to this based on a student's individual experience, but since the personal essay is the main place in the application where the student can really allow their voice to be heard and share insight into who they are as an individual, there are likely many other topics they can choose to write about that are more distinctive and unique than COVID-19," Miller says.

[ Read: What Colleges Look for: 6 Ways to Stand Out. ]

Opinions among admissions experts vary on whether to write about the likely popular topic of the pandemic.

"If your essay communicates something positive, unique, and compelling about you in an interesting and eloquent way, go for it," Carolyn Pippen, principal college admissions counselor at IvyWise, wrote in an email. She adds that students shouldn't be dissuaded from writing about a topic merely because it's common, noting that "topics are bound to repeat, no matter how hard we try to avoid it."

Above all, she urges honesty.

"If your experience within the context of the pandemic has been truly unique, then write about that experience, and the standing out will take care of itself," Pippen says. "If your experience has been generally the same as most other students in your context, then trying to find a unique angle can easily cross the line into exploiting a tragedy, or at least appearing as though you have."

But focusing entirely on the pandemic can limit a student to a single story and narrow who they are in an application, Sawyer says. "There are so many wonderful possibilities for what you can say about yourself outside of your experience within the pandemic."

He notes that passions, strengths, career interests and personal identity are among the multitude of essay topic options available to applicants and encourages them to probe their values to help determine the topic that matters most to them -- and write about it.

That doesn't mean the pandemic experience has to be ignored if applicants feel the need to write about it.

Writing About Coronavirus in Main and Supplemental Essays

Students can choose to write a full-length college essay on the coronavirus or summarize their experience in a shorter form.

To help students explain how the pandemic affected them, The Common App has added an optional section to address this topic. Applicants have 250 words to describe their pandemic experience and the personal and academic impact of COVID-19.

[ Read: The Common App: Everything You Need to Know. ]

"That's not a trick question, and there's no right or wrong answer," Alexander says. Colleges want to know, he adds, how students navigated the pandemic, how they prioritized their time, what responsibilities they took on and what they learned along the way.

If students can distill all of the above information into 250 words, there's likely no need to write about it in a full-length college essay, experts say. And applicants whose lives were not heavily altered by the pandemic may even choose to skip the optional COVID-19 question.

"This space is best used to discuss hardship and/or significant challenges that the student and/or the student's family experienced as a result of COVID-19 and how they have responded to those difficulties," Miller notes. Using the section to acknowledge a lack of impact, she adds, "could be perceived as trite and lacking insight, despite the good intentions of the applicant."

To guard against this lack of awareness, Sawyer encourages students to tap someone they trust to review their writing , whether it's the 250-word Common App response or the full-length essay.

Experts tend to agree that the short-form approach to this as an essay topic works better, but there are exceptions. And if a student does have a coronavirus story that he or she feels must be told, Alexander encourages the writer to be authentic in the essay.

"My advice for an essay about COVID-19 is the same as my advice about an essay for any topic -- and that is, don't write what you think we want to read or hear," Alexander says. "Write what really changed you and that story that now is yours and yours alone to tell."

Sawyer urges students to ask themselves, "What's the sentence that only I can write?" He also encourages students to remember that the pandemic is only a chapter of their lives and not the whole book.

Miller, who cautions against writing a full-length essay on the coronavirus, says that if students choose to do so they should have a conversation with their high school counselor about whether that's the right move. And if students choose to proceed with COVID-19 as a topic, she says they need to be clear, detailed and insightful about what they learned and how they adapted along the way.

"Approaching the essay in this manner will provide important balance while demonstrating personal growth and vulnerability," Miller says.

Pippen encourages students to remember that they are in an unprecedented time for college admissions.

"It is important to keep in mind with all of these (admission) factors that no colleges have ever had to consider them this way in the selection process, if at all," Pippen says. "They have had very little time to calibrate their evaluations of different application components within their offices, let alone across institutions. This means that colleges will all be handling the admissions process a little bit differently, and their approaches may even evolve over the course of the admissions cycle."

Searching for a college? Get our complete rankings of Best Colleges.

- Our Mission

11 Meaningful Writing Assignments Connected to the Pandemic

Writing gives students an outlet to express their feelings and connect with others during this unsettling time in their lives.

With students currently at home because of the pandemic, it’s helpful to provide learning opportunities that get them talking about what’s happening in the world with trusted adults and peers.

These ideas for home assignments build connection and help our young people process this difficult experience while developing their writing skills.

11 Writing Assignments for the Current Moment

1. Interview senior members of the community: With our older community members at higher risk, hearing their stories has increasing significance. Generate interview questions with your students, and conduct a sample interview as a model.

Students can interview family members, senior members of the school staff, or others through handwritten letters, phone calls, or video chats. When students write up and share their interviews with the class, they will get a broader, more nuanced view of older generations’ experiences.

2. Folding stories: In the traditional version of this activity, one person writes a sentence or two on a piece of paper and then folds the paper so that only the last word or phrase can be seen. The next person continues the story for a few sentences before again hiding all but the last word or phrase and then passing the paper on.

To do this remotely, set up a randomized list of all of your students. The first student sends you their contribution, and you send the last phrase of that to the next name on the list. Compile all the contributions in order in a Google Doc to create a single story. Once everyone has contributed, share the whole story with the class.

The format may allow students an imaginative outlet for anxious thoughts and predictions about the future, and the result is almost guaranteed to be hilarious and inspiring to both eager and reluctant writers.

3. Dialogue journals: A journal in which a teacher and student write back and forth to each other is an ongoing communication that helps teachers build relationships with each student while they model writing and observe students’ progressing skills. Start this off by writing a first short entry for each of your students in separate Google Docs, choosing topics you already know they’re interested in and offering personal details about yourself.

You can ask each student to write something once a week—and you’ll respond to each entry, so this does entail a time commitment on your part. The benefit in relationship-building, so difficult to do in distance learning, makes this worth the work.

4. Student-to-student letters: Organize pen pals or small letter-writing groups. Ask students to write back and forth to one or more peers using provided prompts and sample questions. Teach students to consider their audience and to keep a written dialogue going over several letters as they write to different peers. Encourage students to include self-created activities in their letters to peers: They might make a crossword puzzle using the class vocabulary words, create a maze, or share a recipe or a silly joke.

5. Write to an author: A professional writer may be a great correspondent for a young fan, offering insight into key aspects of a favorite book. Follow #WriteToAnAuthor on Twitter for access to mailing addresses of authors who are standing by for letters from young readers. Provide your students with prompts, templates, samples, and feedback to support them in writing thoughtful letters.

6. Adapt a text to reflect current conditions: Lately any story we read or watch can be a painful reminder of how much is changing. Characters are dancing, hugging or shaking hands, and talking to each other in public places. Some students find it comforting to be immersed in that world, but others find these moments upsetting. Assign students the task of rewriting a scene from a story, show, or movie, considering what needs to change for it to be realistic in our current situation but still retain the original essential themes and meaning.

7. Letters to the editor: What do students think about our leaders, policies, and proposed solutions to this pandemic? Guide them through the art of writing a well-crafted letter to the editor, and post submissions on your district, school, or class website, if privacy policies permit that. Give your students guidelines that specify word count, style, and topics, just as official publications do.

8. Student-created blog: Begin by sharing strong examples of student journalism as mentor texts. Invite students to brainstorm ideas for articles and columns. Some students can assume the role of section editors—News, Features, Arts—and others can write articles, take photos, and work on the design and marketing of the website, which students can build using Edublogs .

9. “Slow looking” documentation: Shari Tishman describes “slow looking” as prolonged observation that occurs through all the senses. Students can use a variety of slow looking strategies to observe their setting and sketch or write about their observations. There are seasonal changes to observe, among other things. By practicing slow looking, students may learn to see things they never noticed before. When they share their observations with the class, everyone gains a broader perspective of how the larger environment is changing.

10. Covid-19 comics: The genre of graphic medicine —which uses comics to explore the physical and emotional impacts of medical conditions—shows that comics can be a good way for students to explore troubling experiences. Share comics related to Covid-19 that engage with the wider implications of the pandemic, such as feeling increased isolation, processing conflicting news, and coping with social distancing or unemployment.

Invite students to explore their experiences through an intentional combination of words and pictures. Make it collaborative by having students write text for a peer’s drawings. Students can use Canva to make comics , or draw them on paper and then take photos to upload to the class learning management system.

11. Pandemic journals: A pandemic journal invites students to process their feelings and document their experience for future generations. To structure the assignment, provide prompts and templates. Suggest to students that they layer in artifacts such as news reports, a note received from a friend or neighbor, a copy of an online school schedule for a day, a snippet of an overheard conversation, or a sketch of a parent hunched over a laptop.

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

current events

12 Ideas for Writing Through the Pandemic With The New York Times

A dozen writing projects — including journals, poems, comics and more — for students to try at home.

By Natalie Proulx

The coronavirus has transformed life as we know it. Schools are closed, we’re confined to our homes and the future feels very uncertain. Why write at a time like this?

For one, we are living through history. Future historians may look back on the journals, essays and art that ordinary people are creating now to tell the story of life during the coronavirus.

But writing can also be deeply therapeutic. It can be a way to express our fears, hopes and joys. It can help us make sense of the world and our place in it.

Plus, even though school buildings are shuttered, that doesn’t mean learning has stopped. Writing can help us reflect on what’s happening in our lives and form new ideas.

We want to help inspire your writing about the coronavirus while you learn from home. Below, we offer 12 projects for students, all based on pieces from The New York Times, including personal narrative essays, editorials, comic strips and podcasts. Each project features a Times text and prompts to inspire your writing, as well as related resources from The Learning Network to help you develop your craft. Some also offer opportunities to get your work published in The Times, on The Learning Network or elsewhere.

We know this list isn’t nearly complete. If you have ideas for other pandemic-related writing projects, please suggest them in the comments.

We are having trouble retrieving the article content.

Please enable JavaScript in your browser settings.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access. If you are in Reader mode please exit and log into your Times account, or subscribe for all of The Times.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access.

Already a subscriber? Log in .

Want all of The Times? Subscribe .

Coronavirus and schools: Reflections on education one year into the pandemic

Subscribe to the center for universal education bulletin, daphna bassok , daphna bassok nonresident senior fellow - governance studies , brown center on education policy @daphnabassok lauren bauer , lauren bauer fellow - economic studies , associate director - the hamilton project @laurenlbauer stephanie riegg cellini , stephanie riegg cellini nonresident senior fellow - governance studies , brown center on education policy helen shwe hadani , helen shwe hadani former brookings expert @helenshadani michael hansen , michael hansen senior fellow - brown center on education policy , the herman and george r. brown chair - governance studies @drmikehansen douglas n. harris , douglas n. harris nonresident senior fellow - governance studies , brown center on education policy , professor and chair, department of economics - tulane university @douglasharris99 brad olsen , brad olsen senior fellow - global economy and development , center for universal education @bradolsen_dc richard v. reeves , richard v. reeves president - american institute for boys and men @richardvreeves jon valant , and jon valant director - brown center on education policy , senior fellow - governance studies @jonvalant kenneth k. wong kenneth k. wong nonresident senior fellow - governance studies , brown center on education policy.

March 12, 2021

- 11 min read

One year ago, the World Health Organization declared the spread of COVID-19 a worldwide pandemic. Reacting to the virus, schools at every level were sent scrambling. Institutions across the world switched to virtual learning, with teachers, students, and local leaders quickly adapting to an entirely new way of life. A year later, schools are beginning to reopen, the $1.9 trillion stimulus bill has been passed, and a sense of normalcy seems to finally be in view; in President Joe Biden’s speech last night, he spoke of “finding light in the darkness.” But it’s safe to say that COVID-19 will end up changing education forever, casting a critical light on everything from equity issues to ed tech to school financing.

Below, Brookings experts examine how the pandemic upended the education landscape in the past year, what it’s taught us about schooling, and where we go from here.

In the United States, we tend to focus on the educating roles of public schools, largely ignoring the ways in which schools provide free and essential care for children while their parents work. When COVID-19 shuttered in-person schooling, it eliminated this subsidized child care for many families. It created intense stress for working parents, especially for mothers who left the workforce at a high rate.

The pandemic also highlighted the arbitrary distinction we make between the care and education of elementary school children and children aged 0 to 5 . Despite parents having the same need for care, and children learning more in those earliest years than at any other point, public investments in early care and education are woefully insufficient. The child-care sector was hit so incredibly hard by COVID-19. The recent passage of the American Rescue Plan is a meaningful but long-overdue investment, but much more than a one-time infusion of funds is needed. Hopefully, the pandemic represents a turning point in how we invest in the care and education of young children—and, in turn, in families and society.

Congressional reauthorization of Pandemic EBT for this school year , its extension in the American Rescue Plan (including for summer months), and its place as a central plank in the Biden administration’s anti-hunger agenda is well-warranted and evidence based. But much more needs to be done to ramp up the program–even today , six months after its reauthorization, about half of states do not have a USDA-approved implementation plan.

In contrast, enrollment is up in for-profit and online colleges. The research repeatedly finds weaker student outcomes for these types of institutions relative to community colleges, and many students who enroll in them will be left with more debt than they can reasonably repay. The pandemic and recession have created significant challenges for students, affecting college choices and enrollment decisions in the near future. Ultimately, these short-term choices can have long-term consequences for lifetime earnings and debt that could impact this generation of COVID-19-era college students for years to come.

Many U.S. educationalists are drawing on the “build back better” refrain and calling for the current crisis to be leveraged as a unique opportunity for educators, parents, and policymakers to fully reimagine education systems that are designed for the 21st rather than the 20th century, as we highlight in a recent Brookings report on education reform . An overwhelming body of evidence points to play as the best way to equip children with a broad set of flexible competencies and support their socioemotional development. A recent article in The Atlantic shared parent anecdotes of children playing games like “CoronaBall” and “Social-distance” tag, proving that play permeates children’s lives—even in a pandemic.

Tests play a critical role in our school system. Policymakers and the public rely on results to measure school performance and reveal whether all students are equally served. But testing has also attracted an inordinate share of criticism, alleging that test pressures undermine teacher autonomy and stress students. Much of this criticism will wither away with different formats. The current form of standardized testing—annual, paper-based, multiple-choice tests administered over the course of a week of school—is outdated. With widespread student access to computers (now possible due to the pandemic), states can test students more frequently, but in smaller time blocks that render the experience nearly invisible. Computer adaptive testing can match paper’s reliability and provides a shorter feedback loop to boot. No better time than the present to make this overdue change.

A third push for change will come from the outside in. COVID-19 has reminded us not only of how integral schools are, but how intertwined they are with the rest of society. This means that upcoming schooling changes will also be driven by the effects of COVID-19 on the world around us. In particular, parents will be working more from home, using the same online tools that students can use to learn remotely. This doesn’t mean a mass push for homeschooling, but it probably does mean that hybrid learning is here to stay.

I am hoping we will use this forced rupture in the fabric of schooling to jettison ineffective aspects of education, more fully embrace what we know works, and be bold enough to look for new solutions to the educational problems COVID-19 has illuminated.

There is already a large gender gap in education in the U.S., including in high school graduation rates , and increasingly in college-going and college completion. While the pandemic appears to be hurting women more than men in the labor market, the opposite seems to be true in education.

Looking through a policy lens, though, I’m struck by the timing and what that timing might mean for the future of education. Before the pandemic, enthusiasm for the education reforms that had defined the last few decades—choice and accountability—had waned. It felt like a period between reform eras, with the era to come still very unclear. Then COVID-19 hit, and it coincided with a national reckoning on racial injustice and a wake-up call about the fragility of our democracy. I think it’s helped us all see how connected the work of schools is with so much else in American life.

We’re in a moment when our long-lasting challenges have been laid bare, new challenges have emerged, educators and parents are seeing and experimenting with things for the first time, and the political environment has changed (with, for example, a new administration and changing attitudes on federal spending). I still don’t know where K-12 education is headed, but there’s no doubt that a pivot is underway.

- First, state and local leaders must leverage commitment and shared goals on equitable learning opportunities to support student success for all.

- Second, align and use federal, state, and local resources to implement high-leverage strategies that have proven to accelerate learning for diverse learners and disrupt the correlation between zip code and academic outcomes.

- Third, student-centered priority will require transformative leadership to dismantle the one-size-fits-all delivery rule and institute incentive-based practices for strong performance at all levels.

- Fourth, the reconfigured system will need to activate public and parental engagement to strengthen its civic and social capacity.

- Finally, public education can no longer remain insulated from other policy sectors, especially public health, community development, and social work.

These efforts will strengthen the capacity and prepare our education system for the next crisis—whatever it may be.

Higher Education K-12 Education

Brookings Metro Economic Studies Global Economy and Development Governance Studies

Brown Center on Education Policy Center for Universal Education

Modupe (Mo) Olateju, Grace Cannon, Kelsey Rappe

June 14, 2024

Jon Valant, Nicolas Zerbino

June 13, 2024

Douglas N. Harris

June 6, 2024

- Event Submission

- Community Resources

- About the Bugle

- Business News

- School News

- CLASSIFIEDS

- Trending / Come to Bugle annual meeting

- Trending / MnDOT pauses North Gateway plan for 35W

- Trending / SAP Community Foundation names Brasel youth winner

- Trending / U’s FETCH program pairs students, trainer dogs

- Trending / Changes in commission rules ahead for real estate agents

Student essays reflect Covid-19 struggles

What’s on the minds these days from students at Como Park Senior High School?

Here are essays from juniors Jude Breen, Keira Schumacher and Logan Becker who wrote these essays in late February for English teacher Elizabeth Boyer’s CIS Writing Studio class.

What A Blessing

by Jude Breen

When I reflect on the 2020 football season, I always find myself concurring with the word gratitude.

Every day at practice, Coach Scull would have us take a minute. We would sit there in perfect silence and bask in the opportunity and blessing that we were given in being able to have a season. Not only because it was nice to be doing something normal, but also for the chance to build these lifelong friendships and memories that we all will still think back on decades down the road.

I am constantly thinking back to our game against Johnson. Como hasn’t beat Johnson in football for over 10 years and Johnson likes to let us know that. There was a lot of pressure going into the game. We knew we were a good team with many weapons, but we really had to prove ourselves in this matchup.

The game was on a Saturday morning, and it was the first real cold day we had all year. The type of cold where your toes are numb and your snot is frozen inside of your nose . . . not very pretty.

Despite the crisp wind on our faces, we were fired up.

Our Cougars scored first. I threw a corner route in the end zone to Stone who tracked the rock-hard, bruising football for a touchdown. There’s no feeling quite like your first touchdown. The defense stood strong all game and only allowed one touchdown.

We went into overtime tied 6-6. The strong bodies of our defensive lineman protected the tie, then out came our offense. We direct snapped the ball to Stone and he follows his bodyguard blockers into the end zone, reaching with every inch he has to get the ball over the goal line.

And then, pandemonium ensues. We stormed the field in a sea of black. Johnson players were on their knees questioning how in the world they let Como beat them. The adrenaline running through my body made me forget all about the blistering wind chill, as Coach Scull did his victory dance in our team circle.

Once the celebration is over, the grind started all over again in preparation for the upcoming game. The next Monday we were back on our beautiful turf, again in perfect silence, processing how grateful we are for what we have done so far and what is to come.

I will never forget this season. Hard work truly does pay off, and I have unconditional gratitude for my brothers on my team, and the role models I found in the coaching staff.

A Little Bit of Happiness

By Keira Schumacher

Quarantine has been a hard, boring, slow and tiring time for everyone. Being stuck in the same place day after day has made every moment feel the same. It’s almost been a year now since quarantine has started, so I’m sure that everyone has felt this repetition of days just like I have.

By now it’s very hard to find things that can separate the days for me to make them different or unique. I have hobbies that I can do at home. I draw and paint, play video games. But at some point you get sick of those too.

After months of everything being the same, I knew I had to do something to make my time in quarantine a little bit better. I didn’t think that doing little things, like cleaning my room, walking my dogs, or even just taking time to listen to music would make such an impact on my days.

Taking time for yourself and doing something solely for you and no one else have made my days a little better. When your days start to melt together without being able to separate them, you can get stuck in a rut without being able to get out. That’s happened to me a few times. Sometimes the rut lasts only a few days, but sometimes it can last weeks.

When I’m stuck in this place of repetition it demotivates me to do anything. It feels that anything I do doesn’t really matter because everything will be the same the next day and the day after that. It can be very hard for me to clear my head and start to actively do things rather than just floating through the days.

Some things that have helped me get through these ruts are making a good cup of coffee in the morning, or doing some laundry to be able to wear your favorite sweatshirt again.

I’ve been lucky enough to be able to go downhill skiing this winter, which is the biggest factor for helping me clear my mind and resetting. Being able to breath the cold crisp air on the hills as I’m speeding down. Being able to enjoy skiing with my friends has been one of the main reasons I’m not in a constant rut.

You have to work to find happiness and fulfillment in the little things.

Struggles with online learning

By Logan Becker

Onerous and loneliness are two words I would use to describe the past nine months each and every one of us has experienced. Our main issue, and quite frankly the most obvious one, would be the coronavirus.

It’s been exceptionally difficult on most of us, and the days feel as if they just keep getting worse and worse. Hearing about a vaccine was a lighthearted and a very hopeful sign that everything will turn out okay.

But, social distancing at this point has been nothing but repetitive. I fully understand it’s a safety precaution to keep everyone safe from this pandemic, but it still hurts to know I’m unable to see my friends daily.

I go through my day expecting the same thing consistently over and over again through this pandemic. It’s quite literally the same: Wake up, brush my teeth, take a shower, eat some breakfast, feed my dogs, check in on my little brother, take out the trash, make some lunch, do the dishes, do my laundry, spend time with family and go to sleep. It seems as if spending time at home has been more time consuming than my regular day life before the pandemic. And it’s not entirely easy using my precious free time to focus on school.

Online schooling is more distracting than one might think, surrounded by things you love to do, and having to ignore it to get the things more important done. I’ve always had a difficulty during normal school to get my homework done when I get home from school because I get distracted and it’s really my only time during the day to do what I want to do. But it seems as if that’s how my daily routine has wound up to be. It’s unfortunate to say the least, and overall has been stressful.

I’ve talked with other students about this over Google meets, and we’ve all come to the same consensus that we lack tons of motivation when doing school at home.

Additionally, I find nearly no time to step away from this and haven’t given myself much time to just relax and enjoy myself without the weight of school on my chest. . . . I’m quite fully sure there are hundreds of more students who have dealt with this monstrous difficulty, and it’s been a very strenuous position to be in.

Leave a Reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

DONATE to the BUGLE

DONATE to our 50th Anniversary

Latest Print Edition

RECEIVE our print edition by mail

FIND our print edition near

Park Bugle ARCHIVES (1974-2024)

Upcoming Events

Events search and views navigation, event views navigation, shake your sillies out playtime.

10:30 to 11:30 a.m. Fridays, March 1, 8 and 15. Story, stretching, movement and lots of fun in the library’s auditorium for children ages 2 to 5. Little ones can...

Good Hike Club (Women’s Hiking Group)

Welcome to the Good Hike Club! This is a women’s hiking group based around the Twin Cities of Minnesota. We’ll have regularly scheduled community hikes. There is no cost to...

4th in the Park

It’s almost that special time of year again, where you pull out your flag, grab your lawn chair and put on your red, white and blue…because the annual 4th in...

St. Anthony Park Community Band July 4th Concert

Free Noon concert at the Como Lakeside Pavilion featuring music of American composers

- Google Calendar

- Outlook 365

- Outlook Live

- Export .ics file

- Export Outlook .ics file

SUBMIT your event

Upcoming Bugle Deadlines

Here are our Bugle deadlines for the next three issues. As always, we appreciate when writers and readers submit their articles early.

Please note our publication dates represent when the newspapers go out for delivery. Mail distribution of the paper may take up to several business days . Meanwhile, bulk drop-offs of the paper around town are usually completed two to three days after publication.

- July (Graduation Recognition): Deadline, June 12

- August: Deadline, July 10

- September (Back to school): Deadline, Aug. 8

Get Our Newsletter

Email address:

Local Sponsors

Read these 12 moving essays about life during coronavirus