Jump to navigation

Resources and Programs

- Teaching the Four Skills

- U.S. Culture, Music & Games

- Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs)

- Other Resources

- English Club Texts and Materials

- Teacher's Corner

- Comics for Language Learning

- Online Professional English Network (OPEN)

Table of Contents

- Part One: 15 minutes

- Approximately 1 week for students to observe and gather information outside of class

- Part Two: 45-60 minutes

- To define service learning for students.

- To gather information about issues in the local community.

- To observe community needs and brainstorm possible areas for service-learning projects.

To determine one area of focus for the service-learning project by voting.

Materials: notebooks or paper (if possible, students can designate a notebook to use throughout the service-learning project for a journal and for all of the activities), pencils, whiteboard or chalkboard with markers or chalk, timer

PART ONE - INTRODUCING THE ACTIVITY

- Write the phrase service learning on the board. Ask students if they know what service learning is or if they have ideas about what the term means. If you wish, write their ideas on the board.

- After students have shared what they know about service learning, provide them with a definition (perhaps the one from this month’s Introduction) and write it on the board.

- Allow students time to reflect on the definition and to share their thoughts about it in small groups or as a whole class.

- Explain to the class that they will be participating in a service-learning project and their next step is to gather information about the needs in the local community. You can give examples of specific issues or ask students to share ideas.

- Tell students that they can gather information by talking to friends or family members, by reading local newspapers or publications, by interviewing community leaders, by watching news reports, etc.

- Determine how much time students should spend on collecting information outside of class; one week was suggested in the preparation section. Alternatively, if students do not have access to the internet or news publications outside of class, you can choose to schedule several class periods for them to do research at school.

- Set a date for students to come to class with information about at least three issues filled in on the information-gathering table. Answer any questions students may have about the assignment.

PART TWO - BRAINSTORMING, DISCUSSING, AND VOTING

- On the day that students come to class with their completed information-gathering tables, split the class into groups of about five students. If helpful, have each group assign roles such as recorder, timekeeper, and presenter.

- Explain that each group member will share the community issues he or she recorded. The rest of the group should listen for any common themes, such as housing, hunger, literacy, etc. Provide students with 15-20 minutes for the discussion. Set a timer if desired.

- After each group member has shared his or her observations about issues in the community, the group should discuss common issues or problems. Each group should create a list of the top three issues that they identified after sharing and discussion. If there are any particularly unique or interesting community problems that someone shared, those can also be noted in addition to the top three.

- Once all the groups have had sufficient time to share and discuss ideas, each group will report their top three issues or community problems to the whole class. Depending on the size of your class, this should take 10-20 minutes. As each group names their top issues, write the issues in a list on the board. If issues are repeated, note this by making a tally mark next to the issue on the board. Any unique or interesting issues that were observed by the group can be noted on a separate list.

- Because students have been observing and collecting information about issues in their community, some common themes should naturally emerge. Ask students to look at the list on the board and determine which issues came up the most. (Do not include the separate list of the unique/interesting issues in this part.)

- Create a new list of the top three community problems that the class observed during information gathering. Write it next to the list of the unique or interesting issues, if any.

- Tell students that they will vote on the community issues on this final list to determine the focus issue of the class service-learning project. Explain that after choosing the focus issue, the class will be involved in some type of community service and classroom learning related to that issue.

- Although the class has yet to design the actual project, it may be helpful to give students some examples of what the community service component could be, such as volunteering time to tutor younger students in reading, cleaning up the environment in a part of your community, writing letters to government officials, etc. Answer any questions students may have.

- Allow students to vote for the issue(s) that interest them the most. You can ask students to vote for only one, or you can have them rank each issue from the list according to their level of interest (1 - top choice, 2 - second choice, 3 - third choice, etc.). Students can use a small piece of paper torn from their notebooks to vote.

- Collect all votes before the end of the class period. Count them to determine which issue your class has chosen to focus on for their service-learning project.

The activity presented this week allows students to observe the issues in their community and vote on one area of focus for the service-learning project. The next installment of the Teacher’s Corner will explain how to engage students in classroom learning related to the topic they have chosen. Next week’s activities will allow students to engage in meaningful use of English as they learn more about an issue facing their community.

Last week, students observed issues in the local community and brainstormed possible areas of focus for a service-learning project. Now that students have chosen the area of focus, the next step is to learn more about the chosen issue.

In the Introduction to this month’s Teacher’s Corner, we mentioned that James Minor’s definition of a true service-learning project includes both community service and formal learning. This week will present a Guided Seminar activity that will help students fulfill the “formal learning” portion of the definition. By participating in the Guided Seminar, students will learn more about the community issue they have chosen while practicing meaningful use of English.

GUIDED SEMINAR

- One class period for pre-reading and for answering key questions (This can also be assigned outside of class.)

- One class period for the seminar

- About 20 minutes of time outside of class for the post-seminar reflection

- To have students read information about the community issue in English.

- To participate in meaningful discussion about the issue with classmates in English.

- To write a reflection in English.

Materials: article(s), videos or news clips, radio clips, or social media posts about the chosen issue; key questions (see examples in Preparation Step 2); discussion stems (see examples in Procedure Step 2); service-learning project notebooks and pencils

Preparation:

- Choose one or two articles or news clips for students to read or watch before the seminar. All students will consume the same material beforehand in order to promote thoughtful discussion.

- Was any information that you found in the material surprising? What information made an impression on you as you were reading/watching?

- Have you noticed the effects of this issue in our community? Where, and what have you experienced or observed?

- How would you feel if this issue was a problem for you and your family? Or, if it has been a problem for your family, how has it affected you?

- What do you think are some possible solutions for this problem? Who should be responsible for taking action to start solving this problem?

- Give students time in class to read or watch the information, or assign the material for homework. Have students reflect and answer these questions in their service-learning notebooks after they read or watch the material you have chosen.

- Talk to students about the seminar and your expectations for the discussion. Note that during a seminar, the students really lead the discussion and the teacher acts as more of a facilitator. Students usually do not raise their hands; instead, they simply begin talking, one at a time, while others listen and respond. Depending on your students, you can practice this ahead of time if it will be helpful.

- If you are able to do so, arrange chairs or the students themselves in a large circle on the day of your seminar. Sitting in a circle will encourage discussion amongst students. If not, you can still conduct the seminar in your normal classroom setting.

- Write the discussion stems below, as well as any others you can think of, on the board. If needed, provide students with examples of how to use these.

- I agree/disagree with __________ because…

- I would like to add that…

- I want to know more about…

- This made me think of __________ because…

- I would like to ask __________ about…

- I was surprised to learn…

- I felt __________ when I read…

- I would like to ask <student’s name> what he/she thinks about…

- Before starting the discussion, review procedures and expectations for the seminar with your students. Remind them about the guidelines for taking turns, listening, and responding to classmates. Answer any questions that students may have.

- Ask students to take out the article(s) they read and the reflection questions they answered in their notebooks. Give them a few minutes to review their responses. If students watched news clips, you can replay the clips or have students chat in pairs about what they remember from the clips. While students review, you can write the reflection questions on the board.

- Tell students that they will participate in a guided discussion about the community issue they have been learning about. Explain that you will ask one of the reflection questions and anyone can start the discussion by sharing their thoughts or ideas. Tell students that they can refer to the article/news clips or their notes but should not read directly from their notebooks.

- Read the first reflection question from the board and allow students to respond. Remind students of expectations throughout the seminar if needed. Let students know that they can ask each other questions directly using each other’s names. This can be helpful for encouraging all students to participate.

- Continue until all of the key questions have been addressed. Based on the discussion and level of interest of the students, you can pose follow-up questions during the seminar to further engage students with the topic.

- To wrap up the seminar, you may choose to pose a closing question and give students time to respond with a short answer. It is helpful to share some possible answers with students before asking them to respond. Here are some examples:

- What is one word that comes to mind when you think about this community issue? (Example answers: tragic, opportunity, hope, help, etc.)

- Respond with one word that describes how this issue makes you feel. (Example answers: inspired, hopeless, worried, motivated, etc.)

- What is one word or phrase that you can use to describe what is needed to improve this issue in our community? (Example answers: caring, generosity, time, money, hope, etc.)

- Once students have had a chance to answer the final question, explain that the last step will be to reflect on the seminar in their notebooks. Because this activity is preparing learners to participate in meaningful service learning, it is suggested that you ask students to write about ways the class can engage with the community issue they have chosen to have a positive impact.

- Write the final reflection question on the board for students to copy into their notebooks. You might write and ask “What ideas do you have for activities related to this issue that our class can do to have a positive impact on the community?” or something similar.

- If helpful, give students time to share a few ideas with the whole class. Then, assign students the task of writing ideas in their notebooks (either as homework or during the next class period).

- It should be noted that this seminar can be repeated several times over the duration of the service-learning project. Students can read or watch additional materials about the community issue and answer new questions in a seminar discussion. This activity can also be used to reflect on experiences when students are engaged in the project. More information about how to do this will be shared in Week 4.

The Guided Seminar allows students to use English to learn more about the community issue they are interested in. Learners also use English to engage in thoughtful, structured conversation about the topic, to reflect on what they have learned, and to generate ideas.

The final step in this week’s activity asks students to begin thinking about how the class can engage in service related to the community issue they have selected. This will be the starting point for designing the community service component of the service-learning project. Next week the Teacher’s Corner will present several ways for students to become actively involved with the community issue they have chosen.

Thus far this month in the Teacher’s Corner, students have observed needs in their community, chosen an area of focus for a service-learning project, and participated in a seminar to learn more about their community issue. This week’s installment will present possible types of projects for the community-service portion of the service-learning project.

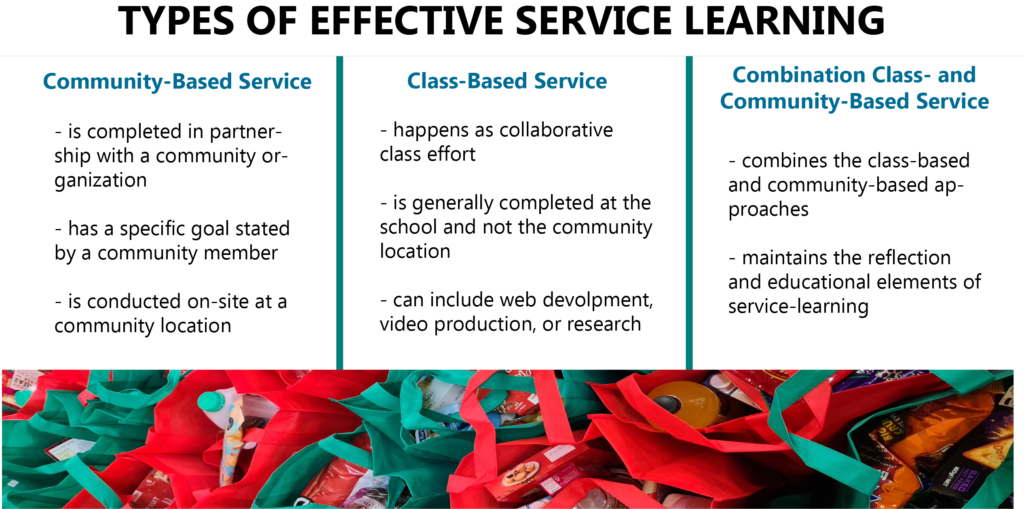

Often when one hears the term service learning, thoughts come to mind of hands-on volunteer work and helping others, usually at a location away from school. While this is a possibility for the service portion of a service-learning project, it is certainly not the only way. It is important to note that there are many opportunities to have an impact in the community without having to leave your school’s campus.

Below are several different suggestions for actions students can take as a way of serving their communities. The most appropriate model for your service will depend on what issue your class has chosen, how much time you have to offer, whether there are established agencies in your community, and what actions will have the most impact. When designing this part of the project, it is recommended that you also consider the ideas about action steps that students wrote in their reflections after last week’s Guided Seminar activity.

VOLUNTERRING TIME WITH A LOCAL AGENCY

One model for a service-learning project is to volunteer with an existing agency or non-government organization (NGO) that is working in the focus area that your class has chosen. How often your students volunteer and for how long will depend on the issue being addressed. For instance, suppose your class voted to focus on early childhood literacy, and they find a local NGO that provides educational activities or services for young children. If your students wanted to work directly with the children in the program, it would likely be more beneficial for them to volunteer twice a week for an hour or two each time, rather than to visit the agency just once for six hours. Or suppose your students chose the focus area of adequate housing, and they find a local agency that provides free home repairs or that builds affordable houses. In this case, it may be better for the class to spend a whole day or two working on a single project with that agency rather than to spread out the time over several weeks or months.

If you and your students cannot travel to the community organization to volunteer your time, there may be other ways to get involved. Many agencies can use assistance with creating brochures, flyers, or educational materials. You can contact the organization to ask about projects your students may be able to complete at your school. Additional ideas about fundraising or collecting materials to benefit a community organization are shared under Fundraising and Collecting Items below.

ADVOCATING AND RAISING AWARENESS

Sometimes students can be of service to people affected by an issue in the community by simply letting others know about the problem. Some people may not even realize that the problem exists because the issue does not directly affect them. There are different ways that students can raise awareness about the community need they have chosen.

Letter-Writing Campaigns

Students can write letters to newspapers, elected officials, or even celebrities about the issues in their community. If students choose to write letters, be sure that they include facts and information about how members of the community are being affected by the issue. Letters asking for people to take a specific action, such as voting for or against legislation or donating funds to a project, are very persuasive.

Often, people advocating for an issue or cause will create a form letter that others can easily sign and send to their government representatives. A form letter may not work for every situation, but if it is something that is appropriate for your students’ service-learning project, they might consider doing so.

Presentations or Speeches

To raise awareness about a community issue, students may want to give presentations or speeches to others about the issue. This type of presentation is effective when students share facts about the issue, discuss how it is affecting members of the community, and offer ways for the audience to take action or get involved. One way for students to gather necessary information is to interview professionals in fields related to the issue or to interview people affected by the issue. Students can share their presentations with community groups, government officials, or even other students and teachers at your school. Students can request time to visit and present at community meetings, or ask teachers for time to come to their classrooms to share information during the school day.

Infographics and Posters

If your students are creative, they can increase awareness about their community issue by making attention-grabbing visuals such as infographics and posters.

Infographics have become a very popular way to communicate facts, figures, and key information about different topics. An excellent free resource that students can use to create infographics is www.canva.com . More information about what to include in infographics and how to get started can be found in this webinar from American English. Infographics can be used in presentations and shared on social media.

Posters are another excellent way for students to share important information about their community issue with others. The information included can be similar to that of an infographic. Students can share their posters with others by using them in presentations or putting them up around your school. Another option would be to hold a poster session where students stand near their posters and share information about the community issue with others walking around the room. Students, administrators, teachers, community groups, and government officials can all be invited to attend a poster session.

FUNDRAISING OR COLLECTING ITEMS

If financial support would benefit the community issue your students have chosen, they may choose to organize one or more fundraisers. There are many ways to do this, some that require a bit of financial investment up front and some that do not. It is always important to communicate the purpose of the fundraiser to the audience, which can be done through presentations, posters, or any other ways your students come up with. Here are some ideas for simple fundraising activities:

- Food or beverage sales: Set up a table at lunch or break times at school to sell snacks, coffee, tea, juice, etc.

- Candy-grams: Your class can collect names, information, and money from students who want to send a candy-gram (a nice note and a piece of candy) to a friend at school. They then deliver the candy-grams on a certain date.

- Change drive: Share information about the issue and the need for money, and ask every class in the school to collect spare change for a certain period of time. Offer a small reward, such as an ice cream party, for the class that raises the most money.

- School dance/event: Plan a dance or other event that interests students at your school and charge admission.

Sometimes certain items are needed to help members of the community. In this situation, students can share information about their community issue and the need for these items and involve the whole school or other community members in collecting these items. Returning to the earlier example of early childhood literacy, students could organize a book drive to collect books for an organization that serves young children. Depending on the need, students can collect clothing, blankets, toiletry items, and more to benefit those affected by the issue.

There are many factors to think about when deciding what the service component of a service-learning project could be. It is important to consider the amount of time needed, students’ interests and abilities, whether your class can travel, and the area of focus. Most importantly, make sure that the activity will benefit both your class and the community. In the final installment of the Teacher’s Corner this month, we will examine ways for students to reflect on the service-learning project and share the impact with others.

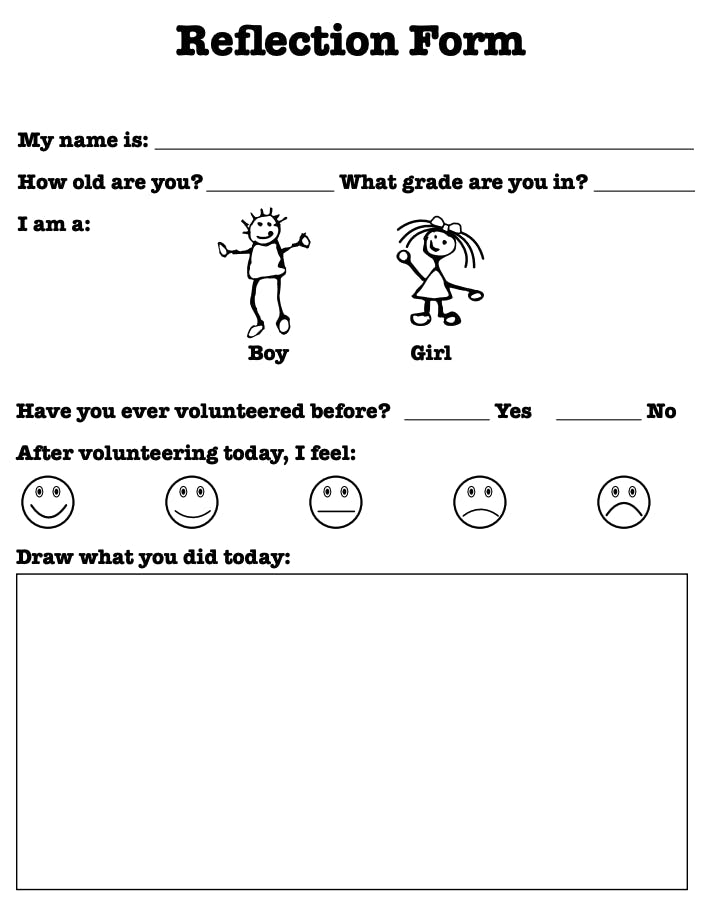

This week’s Teacher’s Corner will begin with discussing how to use a reflection journal throughout the service-learning project. Writing a reflection journal will encourage students to be more thoughtful about what they are learning and experiencing, while also providing another opportunity to practice English. Finally, this week’s installment will present strategies for students to share their experiences and reflections after the completion of the project.

- 15-30 minutes at various points over the course of the project (either in class or outside of class, or a combination of both)

- To encourage students to reflect on experiences during the service-learning project.

- To write in English about experiences, thoughts, and feelings.

Materials: notebooks or paper, pencils, whiteboard or chalkboard with markers or chalk

- At any point during the service-learning project, provide students with a journal prompt and have them reflect in their notebooks.

- Tell students that it is more important that they get their thoughts on paper and not to worry about spelling or grammar for the journal entries.

- After your students have chosen a focus area for their service learning project (after completing the vote from Week 1), ask them to write about what they know about the issue and how it affects the local community.

- Have students answer the reflection questions about the materials they read or watched to prepare for the Guided Seminar activity in Week 2.

- During the service-learning project itself, have students write reflections regularly. If your students visit an agency or interact with others, they can write a reflection after each visit or interaction. If students are planning a fundraiser, participating in a letter writing campaign, or planning presentations, ask them to write about what they are learning, struggling with, or surprised about.

- Provide students with specific questions to answer about what they are seeing and doing or about their interactions with other members of their community or school. Ask questions that prompt students to share feelings or to discuss how their ideas about the issue are evolving or changing.

- Once the service component of the service-learning project is complete, students can look back at their journal entries to see how their thinking has changed or what they have learned about the issue.

Extensions:

- In addition to using the journal to keep track of their experiences and thoughts throughout the service-learning project, students can also use it to participate in additional guided seminars. Students can read additional information about the area of focus (especially if it is one that is often in the news) and follow the same format of pre-reading, answering questions, and sharing ideas in seminars. A less formal approach can also be taken where students simply gather their thoughts in their service-learning notebooks and then use the seminar to share personal experiences and reflections.

SHARING THE SERVICE-LEARNING EXPERIENCE WITH OTHERS

Final Reflective Essay

As a final activity, students can examine all the journal entries they have written over the course of the service-learning project. The entries can be used to write a final reflective essay about the whole experience. Ask students to explain what their ideas and assumptions about the issue were before the project. Using the journal, students can choose one or two key experiences to expand upon and discuss the type of impact they had. Then, students can write about whether the project changed their thinking or reinforced things that they knew. Essays and reflections can be shared among the class or with others invited to attend a sharing session.

Poster Session

Similar to the activity presented in Week 3, asking students to create a poster about their experience and to participate in a poster session is a great way to conclude the service-learning project. If students have photos or mementos from their experience, they can include them in the poster. If you plan to do this activity only with the students who participated in the project, it is best to have students take turns standing at their posters so that they have a chance to see others’ work. The class can be split in half with one group presenting their posters for the first part of the class period and a second group presenting their posters during the second part. Or schedule several poster sessions over different class periods and divide your class so that only a portion of students present each day. School administrators, government officials, other teachers and students, and professionals who work in the area of focus for your project can be invited to attend the sessions. Attendees should walk around and have a chance to look at the posters and talk with students standing at their posters.

Additional Action

After completing a service-learning project, students often want to continue volunteering or doing work in the chosen area of focus. If some of your students are interested in doing this, you can create a final assignment that asks them to write about why they feel inspired by their experience, what they plan to do to stay involved, and how or why they believe their continued involvement in the issue will be beneficial. These reflections and action plans can be shared with their peers, school officials, or community organizations.

All students will have unique experiences and interpret the service-learning project differently. The ideas above are only a few options for final projects. Providing several choices for how students can share their experiences is encouraged. Allowing students to choose how they would like to express their thoughts and present what they have learned can be very motivating and even encourage them to take risks with English in the process.

A service-learning project should have an impact on both the community and the students who are participating. For students learning English, a service-learning project is an opportunity to use the target language to learn about the issue, take part in discussions, interact with others, and reflect upon the experience.

- Privacy Notice

- Copyright Info

- Accessibility Statement

- Get Adobe Reader

For English Language Teachers Around the World

The Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs, U.S. Department of State, manages this site. External links to other Internet sites should not be construed as an endorsement of the views or privacy policies contained therein.

- Skip to main content

- Skip to search

- Skip to footer

Center for Engaged Learning

Service-learning.

Service-learning was one of the ten experiences listed as a high-impact practice (HIP) when such practices were first identified by the Association of American Colleges and Universities (AACU) in 2007. Given the many benefits that service-learning experiences offer students (Jacoby, 2015), it is not surprising that it was one of the ten identified as a HIP in the AACU’s report, College Learning for a New Global Century. Before discussing what makes service-learning a HIP, it is important to define service-learning and describe aspects of the definition in detail.

Every course has a list of objectives that students are expected to reach, and all instructors have to consider how students will achieve those objectives. When course objectives can be reached by doing work for and with community partners, service-learning pedagogy is an option. Bringle and Hatcher (1995) define service-learning as

a credit-bearing, educational experience in which students participate in an organized service activity that meets identified community needs and reflect on the service activity in such a way as to gain further understanding of course content, a broader appreciation of the discipline, and an enhanced sense of civic responsibility. (p. 112)

Each part of this definition is significant and will be described in more depth.

Service-learning is Credit-Bearing

Service-learning is part of a course – a “credit-bearing educational experience” (Bringle & Hatch, 1995, p. 112). This distinguishes service-learning from volunteerism. While volunteers offer service in the community, the service is generally not associated with a course, nor are the volunteers asked to reflect on the service activity. Service-learning is designed as a means for students to learn the content of a course through the process of carrying out service. The service and the learning are intertwined.

An example is helpful here. Volunteers can help hand out blankets to homeless people and drive them to shelters on cold evenings. This act contributes to the public good, yet the volunteers may or may not learn much from the experience. Students in a service-learning sociology course about social issues and local problems can also hand out blankets and drive homeless individuals to shelters, but to meet the objectives of the course, they will do more. The students could help a city to determine if there are enough beds in shelters for the number of homeless individuals in the city. They could gather information on the conditions in shelters as they are handing out blankets. An assignment in the course could be to write a report that city officials use to help determine funding for homeless individuals. The students in this sociology course would have a meaningful educational experience as they provide important and needed work in the community that contributes to the public good.

Meeting an Identified Community Need

Service-learning is intended to meet “identified community needs” (Bringle & Hatcher, 1995, p. 112). Sometimes the learning that university students accomplish in the community is not associated with a service-learning course and is not necessarily focused on a need that community members have stated. For example, schools of education generally have education majors spend time learning and teaching in public elementary, middle, and high schools. These practicum and student teaching experiences are designed for education majors to meet national and state standards as they work toward obtaining teaching licenses. In this instance, the public schools in the community are partnering with the university, but not to meet an identified community need. Rather, the public schools are helping the university to meet the needs of the schools of education for educating teacher candidates. This is the distinction between service-learning and community engagement.

To qualify as an identified community need, a community member must state the particular service that is needed. Service-learning honors the wisdom of individuals who run community organizations and work daily in the community. These are the people who know what type of service is needed and how it should be carried out. Should a college professor approach a leader of a community organization by telling her the work that her students will accomplish for the organization, without understanding the particular needs of the community organization, this would not qualify as service-learning. The college instructor needs to approach the organization by asking the leader to share the particular needs for service the organization has identified. The instructor can then see if any of these needs are related to objectives in her course. When there is a close match between a service need stated by a community member and one or more course objectives, the prospects for service-learning are greatly improved.

There are basically three ways that the service component of a service-learning course can be conducted. The first is by providing community-based service, generally in partnership with a community organization. Again, a leader in the organization would stipulate the specific service need that students would help fulfill on-site in the community. The second way is with a class-based service. Working in the college classroom, students provide a product or service that the community partner has requested. Examples of class-based service include website development, video production, or research for a non-profit organization. Generally with class-based service, the community partner visits the class and explains the service or product needed. Often students are encouraged or even required to visit the community organization at least once during the semester. At the end of the semester, the leader of the community organization might visit the class to see the final product or to discuss the result of the students’ service. The final way that service can be incorporated into a course is a combination of community- and class-based service. Regardless of which of the three types are used, it is critical that the community partner identify the need to be met through service.

Service-learning can also take place in study abroad courses. Instructors make arrangements before arriving at the destination abroad to determine which identified community need the students will be addressing. Often the service-learning experiences are the most meaningful part of the study abroad course because of the interactions students will experience while conducting the service. One professor said of her service-learning course in Africa, “Without the service work, we are simply staring out the bus windows and trying to interpret from our Western lens. The sunsets are magnificent, the elephants awe-inspiring, but it is the interactions in working with the people that are transformative.”

Reflection on Service

Students in service-learning courses are asked to reflect on their service and how it integrates with course content. Frequently students write reflections on their service in the community and participate in class discussions that make connections between course readings and the service activities. Again, this is different from volunteering. Concerns can arise when service is conducted without a reflective component. Negative stereotypes may be reinforced, complex problems may be viewed in superficial ways, and analysis of underlying structural inequalities in society left unconsidered (Jones, 2002). Instructors of service-learning courses work to include thoughtful reflection in class discussions and written assignments. Depending on course content and the particular service-experience, negative stereotypes can be examined and discredited, layers of complexity related to the societal problem can be uncovered, or larger societal issues related to inequality can be studied. Reflection is a central and essential component of service-learning courses.

Understanding of Course Content

Since service-learning is arranged to simultaneously meet an identified community need and one or more course objectives, students’ service experiences will relate to the content of the course they are taking. As students read texts for the course, participate in class discussions and carry out written assignments, they can make connections with their service-learning experiences. Students will sometimes say that their service experiences “bring the course to life.” By this they mean that at least some of the concepts, theories, and principles being taught in the course are learned in a dynamic way with the service. Students are given the opportunity to apply their knowledge in service-learning courses.

Consider two options for how an instructor of a computer course might design her pedagogy. The first option is to teach the course without service-learning. Students will have required readings and written assignments and, as a culminating activity, design a website for an imaginary client. The students will likely enjoy this experience and learn from it, but it is very different in nature from the instructor’s second option for how to teach the course.

The computer course instructor who chooses to use service-learning has required readings and written assignments and also arranges a service project with the director of a local non-profit agency who is requesting a new website for the agency. The director attends a class session to describe the mission of the agency, its clients, and how the new website should function. Prior to designing the website, the students are asked to spend a few hours at the agency to learn more about it. As students work on constructing the website, they keep in contact with the agency director and people employed there to ensure that expectations for the final product are met. Students are highly motivated to create a website that meets with the agency director’s specifications, and they work diligently to produce a high quality product. They know that people who work at the non-profit agency are depending on them and that the clients need an up-to-date website with new and important functions. Focusing on every detail, the students put a significant amount of thought and energy into creating the best possible product possible.

While students in the computer course without service-learning learn how to design a website through the exercise of making one for an imaginary client, the students in the service-learning course have the experience of creating a website for an actual client. They know what it means to meet, and perhaps, even exceed the client’s expectations. They understand the significance of their work and the value of listening carefully to clients in a way that students in the course without service-learning have yet to experience. The students in the service-learning course develop a deep understanding of the course content as they carry out the service associated with the course.

A Broader Appreciation of the Discipline

While not all students in a service-learning course are going to gain a broader appreciation of the discipline, some students will take away deep learning and a greater understanding of the discipline. In a multi-institutional study conducted with 261 engineering students, a survey was used to learn how the students perceived service as a source of learning technical and professional skills relative to traditional course work. Students’ responses indicated that 45% of what they learned about technical skills and 62% of what they learned about professional skills was through service (Carberry, Lee & Swan, 2013). Clearly, these engineering students’ gain a greater understanding of their discipline through their service experiences.

In another study, with a smaller sample of 37 students across sections of a non-profit marketing course, the students compared their learning from a variety of pedagogical tools, including case studies, lectures, reading assignments, guest speakers, exams, textbooks, and service-learning experiences in local chapters of national organizations and non-profit organizations. Students responded with a 5-point Likert scale indicating the degree to which each pedagogical tool helped them to meet the specific objectives of the course. Students rated the service-learning project higher than all of the other pedagogical tools as contributing to their learning in all course objectives (Mottner, 2010). Additionally, the course instructor saw that service-learning was not only effective for supporting students’ learning of the course objectives, but also proved helpful for students in determining their future careers, gaining confidence in interacting with clients, and understanding people from another culture (p. 243).

With the opportunity to apply newly learned skills in a service-learning project, students learn more about the discipline they are studying, and depending on the service-learning setting, they may learn about the lives of people in the community who have fewer resources than they do while also learning about the underlying and systemic reasons for particular circumstances.

Enhanced Sense of Civic Responsibility

The final aspect of Bringle and Hatcher’s (1995) definition of service-learning maintains that students can gain an enhanced sense of civic responsibility by conducting and reflecting on service. Through the process of conducting meaningful service in the community, students can learn the importance of engaging in the community to make positive contributions; that is, they can learn to be civic-minded.

Cress (2013) explains that being civic-minded involves both knowing and doing. College students and graduates may know about and even analyze community problems yet feel overwhelmed and do little or nothing to remedy them. This is knowing without doing. Just as harmful, are individuals who carry out service without substantial knowledge about the issue. This is doing without knowing. Cress calls for community-based educational experiences that increase knowledge and skills to address civic issues. In other words, combining knowing and doing in such a way that civic action is carried out responsibly.

Service-learning offers the initial opportunity for college students to learn how to be civic-minded by combining knowledge gained in the university classroom with skills acquired in community settings so that responsible and respectful service is provided. “Civic-minded graduates will make important contributions to their communities through their capacity to generate citizen-driven solutions” (Moore & Mendez, 2014, p. 33).

Bringle and Hatcher’s (1995) definition of service-learning, quoted and described in detail here, illustrates the multifaceted aspects of this pedagogy. Just tacking on service to an existing course does not make it a service-learning course. The service experience and reflection upon it is integrated with the course. Successes, frustrations, and troubleshooting are discussed in the classroom. Instructors support students in making links between their service experience and the curriculum of the course. Instructors may also support students in analyzing the specific circumstances experienced in service-learning so they develop an understanding of the underlying structural inequalities in the broader society that impact those circumstances. Service-learning pedagogy, when conducted in a thorough and thoughtful manner, has the potential for deepening students’ learning and even offering the prospect of transformative learning (Felten & Clayton, 2011).

With such impressive outcomes, the Association of American Colleges and Universities (2007) rightly included service-learning on the list of high-impact practices. The next section addresses the question, “What makes service-learning a high-impact practice?”

Back to Top

What makes it a high-impact practice?

Calling for “implementation quality,” in high-impact practices, Kuh (2013, p. 7) outlined eight key elements of high-impact practices. According to Kuh, these elements can be useful in determining the quality of a practice for advancing student accomplishment. The eight key elements are listed below.

- Performance expectations set at appropriately high levels

- Significant investment of time and effort by students over an extended period of time

- Interactions with faculty and peers about substantive matters

- Experiences with diversity wherein students are exposed to and must contend with people and circumstances that differ from those with which students are familiar

- Frequent, timely, and constructive feedback

- Periodic, structured opportunities to reflect and integrate learning

- Opportunities to discover relevance of learning through real-world applications

- Public demonstration of competence (p. 10)

In this section, service-learning will be discussed as it relates to each of the key elements of high-impact practices.

High Performance Expectations

From the first day of class, it is important for instructors of service-learning courses to communicate the high expectations they have for students’ service. The quality of the service should influence grading, as this is a way to immediately communicate the centrality of service to students. The leader of the community organization where the service will be performed should be invited to speak to the class about their expectations for service. This leader can share how both high- and low-quality service impact the organization and people in the community. Generally, service does come with some challenges as Cress (2013) points out service-learning involves relationships, and these can go awry. “Personality conflicts can arise, students may lack the ability to deal with others who are different from themselves, community partners may not follow through on their commitments, and group members may not meet their responsibilities” (p. 16). Students who are working to meet high performance expectations will likely need to overcome obstacles that can interfere with performing the service at a peak level. How the students cope with and overcome obstacles is part of the learning in service-learning, and it is a significant aspect of how students demonstrate a high level of performance in the course.

Investment of Significant Time and Effort

When students carry out service, they will likely learn that careful planning, a thoughtful approach, and meaningful analysis of the circumstances takes time, energy, and effort on their part. The old adage that “You only get out of something what you put into it,” most certainly applies to service-learning. Often students arrive at college having learned to focus on academic achievement and to view community service as less important or secondary. With service-learning pedagogy, the service is woven into students’ academic achievement, and, accordingly, students need to focus a significant amount of their time and efforts on providing high quality service in order to meet expectations.

Interactions with Faculty and Peers about Substantive Matters

In order to plan and carry out meaningful service-learning, students will need to work closely with the faculty member teaching the course and their peers who are taking the course alongside them. Consider the example presented earlier of the instructor of a computer course who had the option of having students design a website for an imaginary client or an actual client of a non-profit agency. Students who are designing the website for an imaginary client, even if working in groups, will not have the same types of interactions with faculty and peers as those who are creating a website for an agency in the community. Simply put, more is at stake when designing a product for an actual client. When that client is meeting a specific need in the community, the website must communicate that clearly and allow for clients and donors to have easy access to various parts of the site. Students carrying out this type of service-learning will find that substantive interactions with faculty, peers, and the community leader become necessary in order to successfully complete the project.

Experiences with Diversity

While college campuses can offer students some experience with a range of diversity for race, ethnicity, religious affiliation, socio-economic class, sexual orientation, and age, it is likely that the differences between college students and people living in the local community are greater. Life can look quite different for people living as close as a couple of miles from a university as compared to life on campus.

Students performing service in the community or during study abroad courses can learn about individuals who are living in poverty, struggling to meet basic needs, and who often do without. Students can learn about the impact of discrimination from individuals who have experienced it first-hand. For some students, the disparity between the life experiences of people they meet during service-learning and their own life circumstances makes them realize the privilege they have lived with all of their lives.

Jacoby (2015) explains that when students conduct service without multicultural education, negative stereotypes can be reinforced and perpetuated (p. 232). Jacoby notes that by integrating multicultural education with service-learning, students are helped to “expand their emotional comfort zones in dealing with difference, gain an increasing ability to view the world from multiple perspectives, and reflect on their own social positions in relations to others” (p. 233). Often these goals are among those that faculty hope to achieve when choosing to use service-learning pedagogy.

Frequent, Timely, and Constructive Feedback

Meeting frequently with the faculty member teaching a service-learning course to receive suggestions, learn how to make progress, solve problems, and increase the quality of service will greatly benefit the students who are carrying out the service. The faculty member can provide the timely and constructive feedback that allows students to make improvements in how they conduct the service and develop a more profound understanding of the circumstances that give rise to the need for the services.

Although the leaders of community organizations hosting students for their service-learning courses are generally incredibly busy people, they may be able to arrange brief meetings with students to provide feedback on the service they are conducting. With support from both faculty and leaders in the community, students can refine their service and deepen their understanding. Students often have a greater appreciation of the complexity involved in providing service to meet an identified need as they spend more time within an organization. Frequent and timely feedback affords students the guidance needed to meet the high expectations for service-learning experiences.

Opportunities to Reflect

As noted earlier, reflection is integral to service-learning. In fact, without reflection, a service experience becomes volunteering. The instructor of a service-learning course is responsible for providing periodic, structured opportunities to reflect on the service and integrate the learning from service with course content.

Campus Compact, a source of support for universities implementing service-learning, outlines four ways to structure the reflection process (“Structuring”). The first is that reflection should connect service with other coursework. Second, faculty need to coach students on how to reflect. Third, the reflection process should offer both challenge and support to students. Fourth, the reflection should be continuous; reflection needs to happen before, during and after service-learning experiences. Faculty utilizing this framework will help students to gain insights through the reflection process.

Real-World Applications

Service-learning by definition provides opportunities for students to discover relevance of disciplinary knowledge through real-world application. Students in an educational psychology course will provide service in high-poverty schools; students in human service study course will provide service in a domestic violence shelter; students in a research course will provide service in the form of program assessment for a non-profit organization; students in a marketing course will provide service supporting women in a developing country who are starting a cooperative to sell handmade goods. The needs in most communities outweigh the resources, which makes service-learning a welcome addition in the community, while also providing the chance for university students to make connections between their studies and real-world applications.

Public Demonstration of Competence

Kuh’s (2013) final key element of HIP is for students to publicly demonstrate the competency they gained, in this case, during the service-learning course. While the work of community organizations is ongoing, students’ service is often completed as the semester ends. A culminating project that is presented to stakeholders offers students the opportunity to consider the outcomes of their learning, make connections between course content and the service they provided, and to contemplate on the larger societal issues related to inequality. The culminating project may be an oral presentation or a report given to the community partner. In some cases the culminating project is one of the main goals of the service. Students who exhibit a high level of competence with their culminating project can articulate how the service-learning experience was a HIP for them.

Service-learning is a HIP, and, as such, has the power to impact students’ lives in meaningful, perhaps even transformative ways (Felten & Clayton, 2011). Every key element of HIP, as outlined by Kuh (2013) for the Association of American Colleges and Universities, are met in service-learning. Those students who excel in service-learning have the potential to become civic-minded graduates who bring good to their communities, a goal universities surely find worthy.

Research-Informed Practices

The following best practices in service-learning are adapted from Reitenaure, Spring, Kecskes, Kerrigan, Cress, and Collier (2005) and Howard (1993), who focus on two different sides of service-learning. Reitenaure et al. (2005) focus on the community partnership side of service-learning results in a list centered on establishing strong and productive relationships among the parties involved in service-learning: students, faculty, and community members. Howard’s (1993) focus on the academic side of service-learning results in a list centered on maintaining academic rigor and making space for deep student learning through community praxis. Collectively, their work leads to the following practices for high-quality service-learning:

- Establish shared goals and values

- Focus on academic learning through service

- Provide supports for student learning and reflection

- Be prepared for uncertainty and variation in student learning outcomes

- Build mutual trust, respect, authenticity, and commitment between the student and community partner

- Identify existing strengths and areas for improvement among all partners

- Work to balance power and share resources

- Communicate openly and accessibly

- Commit to the time it will require

- Seek feedback for improvement

(adapted from Reitenaure et al., 2005, and Howard, 1993)

Overall, these recommendations focus on two broad goals of service-learning: establish a strong and reciprocal relationship, and structure and support student learning. These goals happen through frequent and open communication among all involved and facilitated space in and out of the classroom for student reflection and integration of their learning. Each of the model programs described below enact these good practices in similar ways.

Embedded and Emerging Questions for Research, Practice, and Theory

While service-learning is one of the more heavily researched high impact practices, additional areas of study remain. For example, the distinction between service-learning and community engagement warrants additional focus and research. Does this variation in framing equate to differential impacts on student learning? Service-learning also varies in length and intensity, and research is needed to parse out the differential impacts on student learning of short term versus long term service-learning experiences. Recent research has begun to examine the differential impacts on service-learning for underrepresented minority (URM) students and suggests service-learning has strong academic success impacts for URMs, but service-learning is less closely linked to retention and four-year graduation for URMs than it is for highly represented students (Song, Furco, Lopez, & Maruyama, 2017). Additional research is needed to understand why this may be the case and how service-learning experiences might be facilitated to support more equitable student impacts.

Finally, perhaps the greatest avenues for effective community partnerships in the coming years exist in community colleges and distinctive two-year institutions. Community colleges have a great opportunity to contribute to social research surrounding challenges, missions and strengths of community partnerships. Since students are usually still embedded within the surrounding community, the opportunity to develop community partnerships is promising (Brukhardt et al., 2004). Two-year institutions are also on the front-line of accepting students from diverse financial, racial, and experiential backgrounds. These expansions and alterations to the ‘typical’ college student population will continue to present themselves in the coming years. Community colleges have the opportunity to create policies and service-learning opportunities that engage and enrich the lives of diverse student populations, which places two-year institutions above other, more traditional, colleges that may be more delayed in response to such changes. As Butin (2006) describes, current service-learning and engagement is only focused towards “full-time single, non-indebted, and childless students pursuing a liberal arts degree” (p.482). As a result, colleges and universities who adapt to the future trends that break out of such barriers will be more successful with engaged learning in the years to come.

Key Scholarship

Ash, Sarah L., and Patti H. Clayton. 2004. “The Articulated Learning: An approach to Guided Reflection and Assessment.” Innovative Higher Education 29 (2): 137-154.

About this Journal Article:

Reflection is an integral aspect of service-learning, but it does not simply happen by telling students to reflect. This paper describes the risks involved in poor quality reflection and explains the results of rigorous reflection. A rigorous reflection framework is introduced that involves objectively describing an experience, analyzing the experience, and then articulating learning outcomes according to guiding questions.

Celio, Christine I., Joseph Durlak, and Allison Dymnicki. 2011. “A Meta-Analysis of the Impact of Service-Learning on Students.” Journal of Experiential Education 34 (2): 164-181.

For those seeking empirical data regarding the value of service-learning, this meta-analysis provides considerable evidence. Representing data from 11,837 students, this meta-analysis of 62 studies identified five areas of gain for students who took service-learning courses as compared to control groups who did not. The students in service-learning courses demonstrated significant gains in their self-esteem and self-efficacy, educational engagement, altruism, cultural proficiency, and academic achievement. Studies of service-learning courses that implemented best practices (e.g., supporting students in connecting curriculum with the service, incorporating the voice of students in the service-learning project, welcoming community involvement in the project, and requiring reflection) had higher effect sizes.

Cress, Christine M., Peter J. Collier, Vicki L. Reitenauer, and Associates, eds. 2013. Learning through Service: A Student Guidebook for Service-Learning and Civic Engagement across Academic Disciplines and Cultural Communities, 2nd ed. Sterling, VA: Stylus Publishing, LLC.

About this Edited Book:

Although written for students to promote an understanding of their community service through reflection and their personal development as citizens who share expertise with compassion, this text is also useful for faculty. Among the many topics addressed, it provides descriptions of service-learning and civic engagement, explains how to establish and deepen community partnerships, and challenges students to navigate difference in ways that unpack privilege and analyze power dynamics that often surface in service-learning and civic engagement. Written in an accessible style, it is good first text for learning about service-learning and civic engagement.

Delano-Oriaran, Omobolade, Marguerite W Penick-Parks, and Suzanne Fondrie, eds. 2015. The SAGE Sourcebook of Service-Learning and Civic Engagement. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.

This tome contains 58 chapters on a variety of aspects related to service-learning and civic engagement. The intended audience is faculty in higher education and faculty in P-12 schools, as well as directors of service-learning or civic engagement centers in universities or school districts. The SAGE Sourcebook of Service-Learning and Civic Engagement outlines several theoretical models on the themes of service-learning and civic engagement, provides guides that faculty can employ when developing service-learning projects, shares ideas for program development, and offers numerous resources that faculty can use. Parts I – IV of the sourcebook are directed toward general information about service-learning and civic engagement, including aspects of implementation; parts V – VIII describe programs and issues related to the use of service-learning or civic engagement within disciplines or divisions; part IX addresses international service-learning; and part X discusses sustainability.

Felten, Peter, and Patti H. Clayton. 2011. “Service-Learning.” New Directions for Teaching and Learning 128: 75-84. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1002/tl.470 .

Felten and Clayton define service-learning, describe its essential aspects, and review the empirical evidence supporting this pedagogy. Both affective and cognitive aspects of growth are examined in their review. The authors conclude that effectively designed service-learning has considerable potential to promote transformation for all involved, including those who mentor students during the service-learning experience.

Jacoby, Barbara. 2015. Service-learning essentials: Questions, answers and lessons learned. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

About this Book:

Arranged as a series of questions and answers about service-learning, this text shares research and the author’s personal wisdom gathered over decades of experience in service-learning. Faculty members who are new to service-learning will learn the basics of this pedagogy. Those with experience will discover ways to refine and improve their implementation of service-learning. All aspects of service-learning are clearly explained in this accessible text, including advise for overcoming obstacles.

Jones, Susan R. 2002. “The Underside of Service-Learning.” About Campus 7 (4): 10-15.

Although an older publication, this article is not outdated. Jones describes how some students resist examining assumptions and refuse to see how their beliefs perpetuate negative stereotypes. These students challenge both the faculty member teaching the service-learning course and classmates. Jones discusses the need for faculty to anticipate how to respond to students’ racist or homophobic comments in a way that acknowledges where the students are developmentally, while also honoring the complexity involved. Additionally, the author recommends that faculty examine their own background and level of development relative to issues of privilege and power that can arise in service-learning pedagogy.

McDonald, James, and Lynn Dominguez. 2015. “Developing University and Community Partnerships: A Critical Piece of Successful Service Learning.” Journal of College Science Teaching 44 (3): 52-56.

Developing a positive partnership with a community organization is a critical aspect service-learning. McDonald and Dominguez discuss best practice for service-learning and explain a framework for developing a successful partnership in the community. Faculty need to

- Identify the objectives of the course that will be met through service,

- Identify the community organization whose mission or self-identified need can be address with service-learning,

- Define the purpose of the project, the roles, responsibilities and benefits of individuals involved,

- Maintain regular communication with the community partner, and

- Invite the community partner to the culminating student presentation on their service-learning.

Two service-learning projects, one for an environmental course and another for an elementary methods science course, are described along with the positive outcomes for students and community partners.

Warner, Beth, and Judy Esposito. 2009. “What’s Not in the Syllabus: Faculty Transformation, Role Modeling and Role Conflict in Immersion Service-Learning Courses.” International Journal of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education 20 (3): 510-517.

This article describes immersive learning in the context of international service learning (or domestic service learning that happens away from the local community surrounding an institution) where students and faculty live and work together in a deeply immersive environment. The article is careful to articulate the difference in international or away service learning, where the immersion is constant, with localized experiences where the service learning experience is socketed into a student’s day. The article also discusses the value and need of the instructor working in close proximity to students as a facilitative guide to the learning experience.

See all Service-Learning entries

Model Programs

The following model programs are drawn from recommendations by service-learning professionals across the United States. All of these selected programs also meet the Carnegie Classification for Community Engagement. Carnegie defines community engagement as:

The partnership of college and university knowledge and resources with those of the public and private sectors to enrich scholarship, research and creative activity; enhance curriculum, teaching and learning; prepare educated, engaged citizens; strengthen democratic values and civic responsibility; address critical societal issues; and contribute to the public good. (“Defining Community Engagement,” 2018, para. 2)

This voluntary classification requires schools to collect data and provide evidence of alignment across mission and commitments; this evidence is then reviewed by a national review panel before an institution is selected for inclusion on the list. While community engagement is not always service-learning, the two are closely related and many campus centers offer more expansive definitions to include both service learning and community engagement.

Drake University’s Office of Community Engaged Learning and Service emphasizes models of service learning focused on project completion rather than hours served. They have seven models for service-learning: project or problem based, multiple course projects, placement based, community education and advocacy, action research, one-time group service project, and service internships. Descriptions of each model can be found here . All of these models must meet their four main attributes for community engaged learning. They must have 1) learning outcomes, 2) application and integration, 3) reciprocity, and 4) reflection and assessment.

Elon University’s Kernodle Center for Service Learning and Community Engagement has existed since 1995 and aims, “in partnership with local and global communities, to advance student learning, leadership, and citizenship to prepare students for lives of active community engagement within a complex and changing world.” Elon University has several interdisciplinary minors which include service learning as an explicit component of their educative goals. The University also includes service learning as a way students may fulfill one of their experiential learning requirements (ELR) through enrollment in an associated service learning course or through 15 days of service along with mentored research and reflection experiences.

James Madison University’s Center for Community Service-Learning offers a range of service options for students, but is especially intentional about facilitating course-based service-learning. They support student placement with community partners as is relevant to the course, offer one-on-one faculty consultations, and share reflection resources to support students’ integration of their service-learning with course goals and broader learning goals. JMU’s focus on reflection as a core component of service-learning is evident throughout their center, including their definition of service-learning: “[Service-learning] cultivates positive social change through mutually beneficial service partnerships, critical reflection, and the development of engaged citizens.” Their seven tenets of service-learning (humility, intentionality, equity, accountability, service, relationships, and learning) can help guide faculty development of mutually supportive goals with community partners.

Marquette University’s Service Learning Program is housed within their Center for Teaching and Learning separate from their Center for Community Service. The program is intentional about distinguishing between community service, internships, and service-learning, and focuses their work around five models of service-learning: placement model, presentation model, presentation-plus model, product model, and project model. They offer descriptions and examples of each model here . Marquette structures service-learning as a “philosophy of education.” Their program also offers numerous resources around service-learning course design.

Rollins College’s Center for Leadership and Community Service uses the language of community engagement, but is firm in the standard that for a course to be considered a community engagement course, it must meet a community-identified need. Community partners at Rollins are considered co-educators, and Rollins’ course guidelines emphasize reciprocity in the community-course partnership. The culture surrounding these ideals is so strong that “over 74% of all Rollins faculty have been involved in at least one aspect of community engagement through service-learning, community-based research, professional development, immersion, or campus/community partnership. In addition, over the last seven years every major at Rollins has offered at least one academic course with a community experience” (“ Faculty Resources “).

Related Blog Posts

Facilitating integration of and reflection on engaged and experiential learning.

Since 2019, I’ve been working with my colleague Paul Miller to create an institutional toolkit for fostering both students’ self-reflection and their mentoring conversations with peers, staff, and faculty in order to deepen students’ educational experiences. Our institution, Elon University,…

Incorporating Multiple Dimensions in the First-Year Experience

60-Second SoTL – Episode 49 This episode features on open-access article on service-learning and leadership development in first-year seminars: Krsmanovic, Masha. 2022. “Fostering Service-Learning and Leadership Development through First-Year Seminar Courses.” Journal of Service-Learning in Higher Education 15: 54–70. View a…

Integrating ePortfolios in Work-Integrated Learning Experiences

Work-Integrated Learning (WIL) refers to the integration of practical work experiences with academic learning. Experiences falling under this umbrella provide students with opportunities to apply their knowledge to professional work environments, research, and service learning. There are many benefits of…

View All Related Blog Posts

Featured Resources

Teaching service-learning online or in hybrid/flex models.

In response to shifts to online learning due to COVID-19 in spring 2020 and in anticipation of alternate models for higher education in fall 2020 and beyond, we have curated publications and online resources that can help inform programmatic and…

- Association of American Colleges and Universities (2007) College learning for a new global century , Association of American Colleges and Universities. Washington, DC. http://www.aacu.org/advocacy/leap/documents/GlobalCentury_final.pdf

- Bringle, R., & Hatcher, J. (1995). A service learning curriculum for faculty. The Michigan Journal of Community Service-Learning, 2 (1), 112-122.

- Brukardt, M. H., Holland, B., Percy, S. L., Simpher, N., on behalf of Wingspread Conference Participants. (2004). Wingspread Statement: Calling the question: Is higher education ready to commit to community engagement. Milwaukee: University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee

- Butin, D. W. (2006). The limits of service-learning in higher education. The Review of Higher Education, 29 (4), 473-498.

- Campus Compact (n.d.), Structuring the reflection process . Retrieved August 2017 from http://compact.org/disciplines/reflection/structuring/

- Carberry, A., Lee, H., & Swan, C. (2013). Student perceptions of engineering service experiences as a source of learning technical and professional skills, International Journal for Service Learning in Engineering, 8 (1), 1-17.

- Cress, C. M. (2013). What are service-learning and community engagement? In Cress, C. M., Collier, P. J., Reitenauer, V. L., and Associates, Learning through serving 2 nd ed. , pp. 9-18. Richmond, VA: Stylus Publishing LLC.

- Felten, P., & Clayton, P. H. (2011). Service-learning. Evidence-based teaching. New Directions for Teaching and Learning , 128, 75-84.

- Howard, J. (1993). Praxis I: A faculty casebook on community service learning. Ann Arbor, MI: Office of Community Service Learning Press, University of Michigan.

- Jacoby, B. (2015). Service-learning essentials: Questions, answers, and lessons learned . San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Jones, S. R. (2002). The underside of service-learning, About Campus , 7(4), 10-15.

- Kuh, G. D. (2013). Taking HIPs to the next level. In G. D. Kuh & K. O’Donnell (Eds.) pp. 1-14, Ensuring quality and taking high-impact practices to scale . Washington, DC: Association of American Colleges and Universities.

- Moore, T. L., & Mendez, J. P. (2014). Civic engagement and organizational learning strategies for student success. In P. L. Eddy (Ed.), Connecting learning across the institution (New Directions in Higher Education No. 165 , pp. 31-40). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Mottner, S. (2010). Service-learning in a nonprofit marketing course: A comparative case of pedagogical tools. Journal of Nonprofit & Public Sector Marketing, 22 (3), 231-245.

- Reitenaure, V. L., Spring, A., Kecskes, K., Kerrigan, S.A., Cress, C. M., & Collier, P. J. (2005). Chapter 2: Building and maintaining community partnerships. In Cress, C. M., Collier, P. J., Reitenaure, V. L., & Associates (Eds.) Learning through service: A student guidebook for service-learning and civic engagement across academic disciplines and cultural communities (17-31). Sterling, VA: Stylus Publishing, LLC.

- Song, W., Furco, A., Lopez, I., & Maruyama, G. (2017). Examining the relationship between service-learning participation and the educational success of underrepresented students. Michigan Journal of Community Service Learning, 24 (1) 23-37.

The Center thanks Mary Knight-McKenna for contributing the initial content for this resource. The Center’s 2018-2020 graduate apprentice, Sophia Abbot, extended the content, with additional contributions from Elon Masters of Higher Education students Caroline Dean, Jillian Epperson, Tobin Finizio, Sierra Smith, and Taylor Swan.

Service Learning

This guide provides insight into service learning including the benefits of using it in the classroom, ideas for implementation, and sample assignments.

An academic course that involves community engagement — more widely known as service learning or community-based learning — is “an approach to teaching and learning in which students use academic knowledge and skills to address genuine community needs.” This type of civic engagement aligns closely with Boston University’s core institutional values. As the BU Mission Statement emphasizes, “We remain dedicated to our founding principles: that higher education should be accessible to all and that research, scholarship, artistic creation, and professional practice should be conducted in the service of the wider community — local and international.”

Note: In its focus on addressing real-world issues, service learning is often seen as a kind of experiential learning. Consult CTL’s guide on experiential learning to learn more.

What are the benefits?