Blog about Writing Case Study and Coursework

dudestudy.com

How to Write an Introduction for a Case Study Report

If you’re looking for examples of how to write an introduction for a case-study report, you’ve come to the right place. Here you’ll find a sample, guidelines for writing a case-study introduction, and tips on how to make it clear. In five minutes or less, recruiters will read your case study and decide whether you’re a good fit for the job.

Example of a case study introduction

An example of a case study introduction should be written to provide a roadmap for the reader. It should briefly summarize the topic, identify the problem, and discuss its significance. It should include previous case studies and summarize the literature review. In addition, it should include the purpose of the study, and the issues that it addresses. Using this example as a guideline, writers can make their case study introductions. Here are some tips:

The first paragraph of the introduction should summarize the entire article, and should include the following sections: the case presentation, the examinations performed, and the working diagnosis, the management of the case, and the outcome. The final section, the discussion, should summarize the previous subsections, explain any apparent inconsistencies, and describe the lessons learned. The body of the paper should also summarize the introduction and include any notes for the instructor.

The last section of a case study introduction should summarize the findings and limitations of the study, as well as suggestions for further research. The conclusion section should restate the thesis and main findings of the case study. The conclusion should summarize previous case studies, summarize the findings, and highlight the possibilities for future study. It is important to note that not all educational institutions require the case study analysis format, so it is important to check ahead of time.

The introductory paragraph should outline the overall strategy for the study. It should also describe the short-term and long-term goals of the case study. Using this method will ensure clarity and reduce misunderstandings. However, it is important to consider the end goal. After all, the objective is to communicate the benefits of the product. And, the solution should be measurable. This can be done by highlighting the benefits and minimizing the negatives.

Structure of a case study introduction

The structure of a case study introduction is different from the general introduction of a research paper. The main purpose of the introduction is to set the stage for the rest of the case study. The problem statement must be short and precise to convey the main point of the study. Then, the introduction should summarize the literature review and present the previous case studies that have dealt with the topic. The introduction should end with a thesis statement.

The thesis statement should contain facts and evidence related to the topic. Include the method used, the findings, and discussion. The solution section should describe specific strategies for solving the problem. It should conclude with a call to action for the reader. When using quotations, be sure to cite them properly. The thesis statement must include the problem statement, the methods used, and the expected outcome of the study. The conclusion section should state the case study’s importance.

In the discussion section, state the limitations of the study and explain why they are not significant. In addition, mention any questions unanswered and issues that the study was unable to address. For more information, check out the APA, Harvard, Chicago, and MLA citation styles. Once you know how to structure a case study introduction, you’ll be ready to write it! And remember, there’s always a right and wrong way to write a case study introduction.

During the writing process, you’ll need to make notes on the problems and issues of the case. Write down any ideas and directions that come to mind. Avoid writing neatly. It may impede your creative process, so write down a rough draft first, and then draw it up for your educational instructor. The introduction is an overview of the case study. Include the thesis statement. If you’re writing a case study for an assignment, you’ll also need to provide an overview of the assignment.

Guidelines for writing a case study introduction

A case study is not a formal scientific research report, but it is written for a lay audience. It should be readable and follow the general narrative that was determined in the first step. The introduction should provide background information about the case and its main topic. It should be short, but should introduce the topic and explain its context in just one or two paragraphs. An ideal case study introduction is between three and five sentences.

The case study must be well-designed and logical. It cannot contain opinions or assumptions. The research question must be a logical conclusion based on the findings. This can be done through a spreadsheet program or by consulting a linguistics expert. Once you have identified the major issues, you need to revise the paper. Once you have revised it twice, it should be well-written, concise, and logical.

The conclusion should state the findings, explain their significance, and summarize the main points. The conclusion should move from the detailed to the general level of consideration. The conclusion should also briefly state the limitations of the case study and point out the need for further research in order to fully address the problem. This should be done in a manner that will keep the reader interested in reading the paper. It should be clear about what the case study found and what it means for the research community.

The case study begins with a cover page and an executive summary, depending on your professor’s instructions. It’s important to remember that this is not a mandatory element of the case study. Instead, the executive summary should be brief and include the key points of the study’s analysis. It should be written as if an executive would read it on the run. Ultimately, the executive summary should include all the key points of the case study.

Clarity in a case study introduction

Clarity in a case study introduction should be at the heart of the paper. This section should explain why the case was chosen and how you decided to use it. The case study introduction varies according to the type of subject you are studying and the goals of the study. Here are some examples of clear and effective case study introductions. Read on to find out how to write a successful one. Clarity in a case study introduction begins with a strong thesis statement and ends with a compelling conclusion.

The conclusion of the case study should restate the research question and emphasize its importance. Identify and restate the key findings and describe how they address the research question. If the case study has limitations, discuss the potential for further research. In addition, document the limitations of the case study. Include any limitations of the case study in the conclusion. This will allow readers to make informed decisions about whether or not the findings are relevant to their own practices.

A case study introduction should include a brief discussion of the topic and selected case. It should explain how the study fits into current knowledge. A reader may question the validity of the analysis if it fails to consider all possible outcomes. For example, a case study on railroad crossings may fail to document the obvious outcome of improving the signage at these intersections. Another example would be a study that failed to document the impact of warning signs and speed limits on railroad crossings.

As a conclusion, the case study should also contain a discussion of how the research was conducted. While it may be a case study, the results are not necessarily applicable to other situations. In addition to describing how a solution has solved the problem, a case study should also discuss the causes of the problem. A case study should be based on real data and information. If the case study is not valid, it will not be a good fit for the audience.

Sample of a case study introduction

A good case study introduction serves as a map for the reader to follow. It should identify the research problem and discuss its significance. It should be based on extensive research and should incorporate relevant issues and facts. For example, it may include a short but precise problem statement. The next section of the introduction should include a description of the solution. The final part of the introduction should conclude with the recommended action. Once the reader has a sense of the direction the study will take, they will feel confident in pursuing the study further.

In the case of social sciences, case studies cannot be purely empirical. The results of a case study can be compared with those of other studies, so that the case study’s findings can be assessed against previous research. A case study’s results can help support general conclusions and build theories, while their practical value lies in generating hypotheses. Despite their utility, case studies often contain a bias toward verification and tend to confirm the researcher’s preconceived notions.

In the case of case studies, the conclusions section should state the significance of the findings, stating how the findings of the study differ from other previous studies. Likewise, the conclusion section should summarize the key findings, and make the reader understand how they address the research problem. In the case of a case study, it is crucial to document any limitations that have been identified. After all, a case study is not complete without further research.

After the introduction, the main body of the paper is the case presentation. It should provide information about the case, such as the history, examination results, working diagnosis, management, and outcome. It should conclude with a discussion, explaining the correlations, apparent inconsistencies, and lessons learned. Finally, the conclusion should state whether the case study presented the results in the desired way. The findings should not be overgeneralized, and the conclusions must be derived from this information.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

How to write a case study — examples, templates, and tools

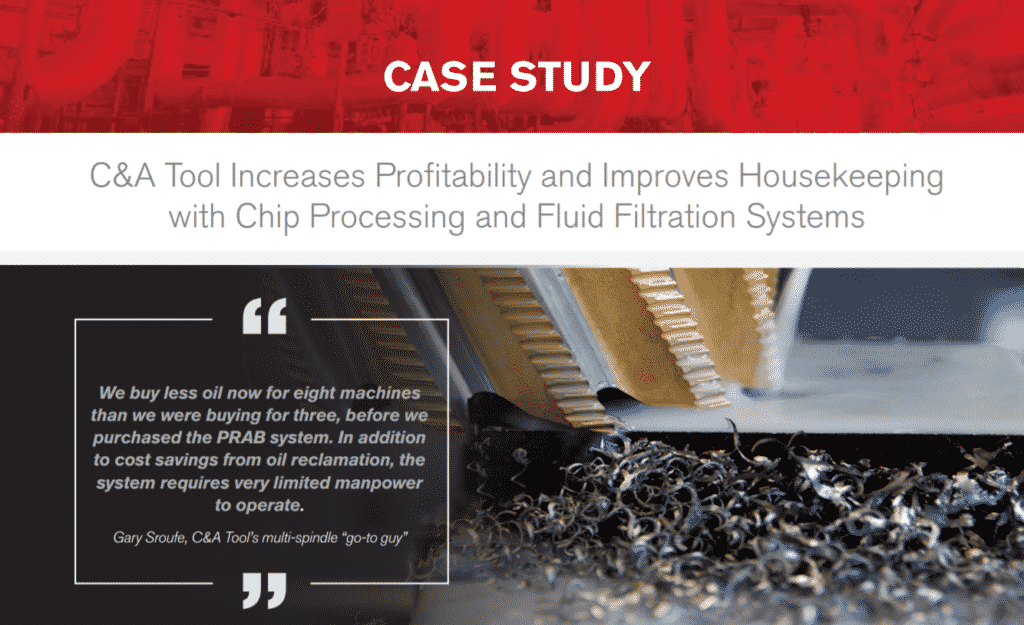

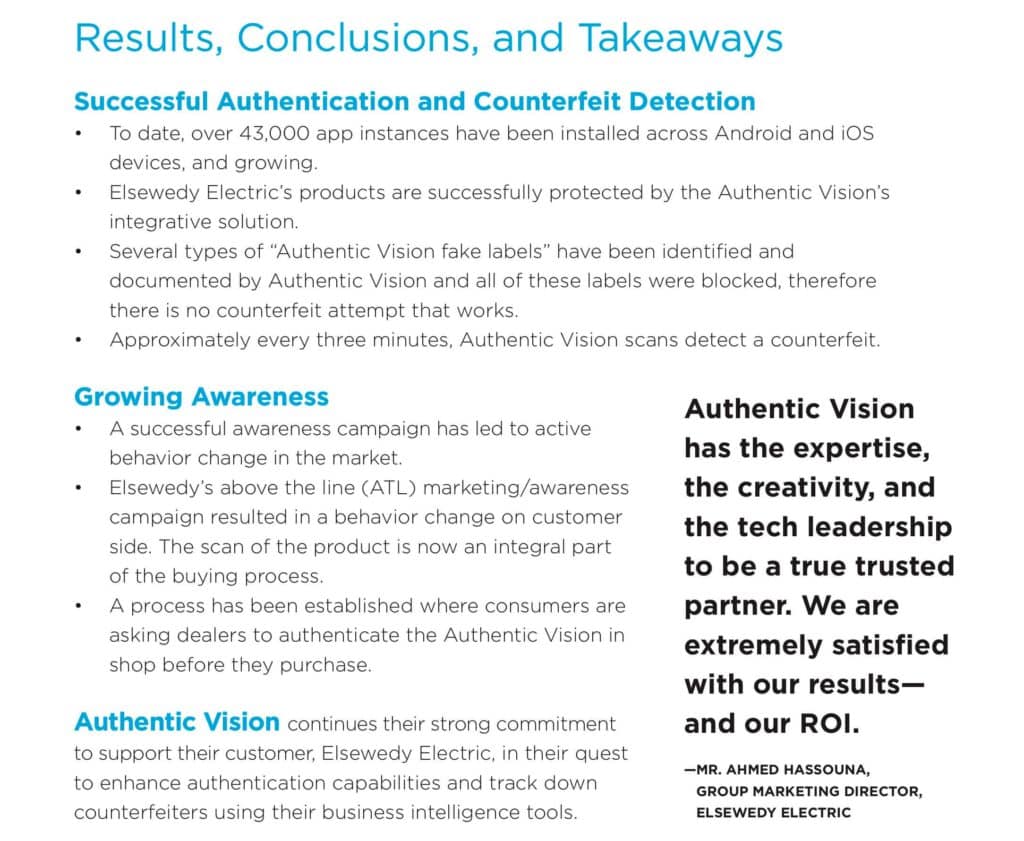

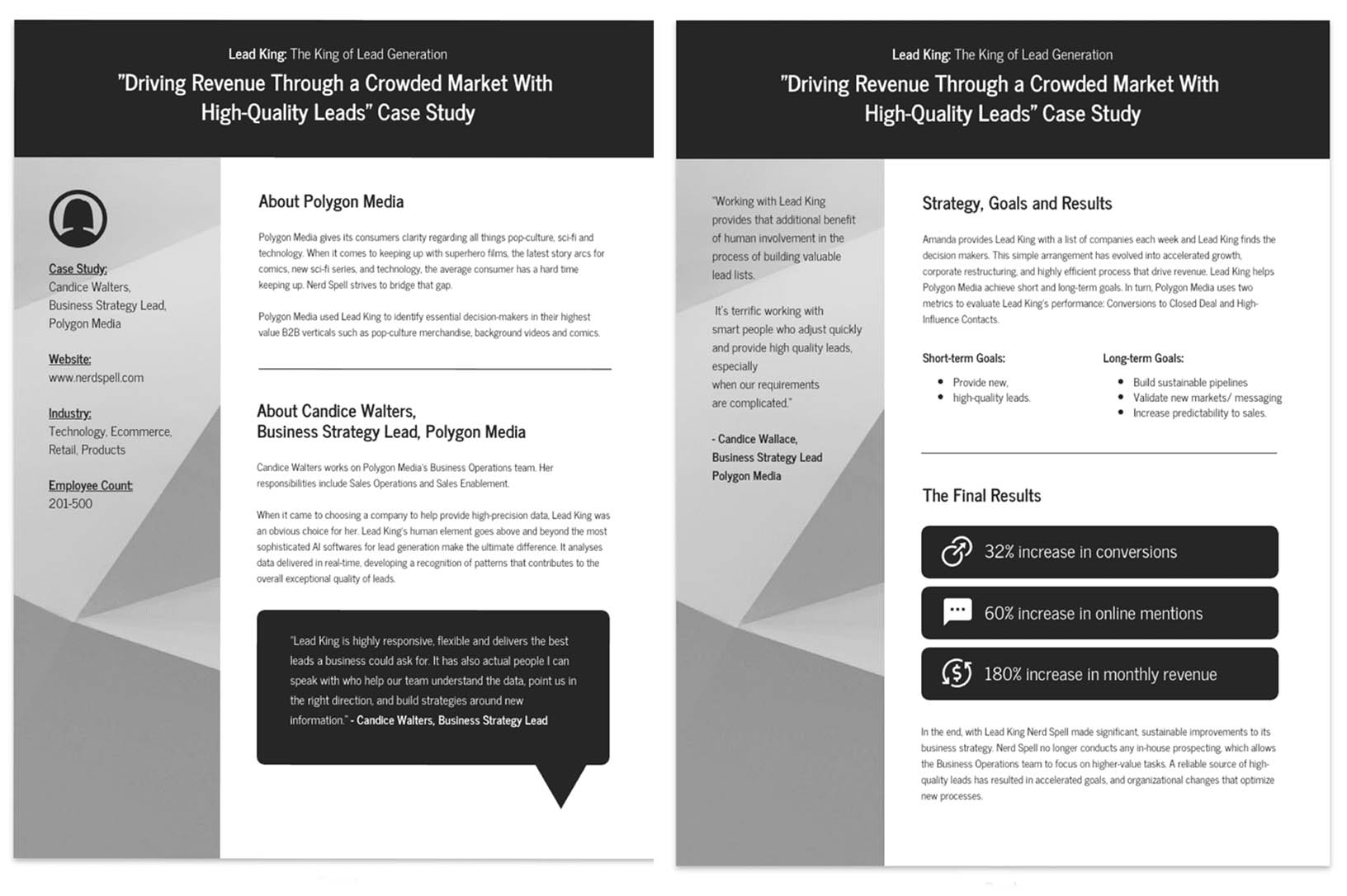

It’s a marketer’s job to communicate the effectiveness of a product or service to potential and current customers to convince them to buy and keep business moving. One of the best methods for doing this is to share success stories that are relatable to prospects and customers based on their pain points, experiences, and overall needs.

That’s where case studies come in. Case studies are an essential part of a content marketing plan. These in-depth stories of customer experiences are some of the most effective at demonstrating the value of a product or service. Yet many marketers don’t use them, whether because of their regimented formats or the process of customer involvement and approval.

A case study is a powerful tool for showcasing your hard work and the success your customer achieved. But writing a great case study can be difficult if you’ve never done it before or if it’s been a while. This guide will show you how to write an effective case study and provide real-world examples and templates that will keep readers engaged and support your business.

In this article, you’ll learn:

What is a case study?

How to write a case study, case study templates, case study examples, case study tools.

A case study is the detailed story of a customer’s experience with a product or service that demonstrates their success and often includes measurable outcomes. Case studies are used in a range of fields and for various reasons, from business to academic research. They’re especially impactful in marketing as brands work to convince and convert consumers with relatable, real-world stories of actual customer experiences.

The best case studies tell the story of a customer’s success, including the steps they took, the results they achieved, and the support they received from a brand along the way. To write a great case study, you need to:

- Celebrate the customer and make them — not a product or service — the star of the story.

- Craft the story with specific audiences or target segments in mind so that the story of one customer will be viewed as relatable and actionable for another customer.

- Write copy that is easy to read and engaging so that readers will gain the insights and messages intended.

- Follow a standardized format that includes all of the essentials a potential customer would find interesting and useful.

- Support all of the claims for success made in the story with data in the forms of hard numbers and customer statements.

Case studies are a type of review but more in depth, aiming to show — rather than just tell — the positive experiences that customers have with a brand. Notably, 89% of consumers read reviews before deciding to buy, and 79% view case study content as part of their purchasing process. When it comes to B2B sales, 52% of buyers rank case studies as an important part of their evaluation process.

Telling a brand story through the experience of a tried-and-true customer matters. The story is relatable to potential new customers as they imagine themselves in the shoes of the company or individual featured in the case study. Showcasing previous customers can help new ones see themselves engaging with your brand in the ways that are most meaningful to them.

Besides sharing the perspective of another customer, case studies stand out from other content marketing forms because they are based on evidence. Whether pulling from client testimonials or data-driven results, case studies tend to have more impact on new business because the story contains information that is both objective (data) and subjective (customer experience) — and the brand doesn’t sound too self-promotional.

Case studies are unique in that there’s a fairly standardized format for telling a customer’s story. But that doesn’t mean there isn’t room for creativity. It’s all about making sure that teams are clear on the goals for the case study — along with strategies for supporting content and channels — and understanding how the story fits within the framework of the company’s overall marketing goals.

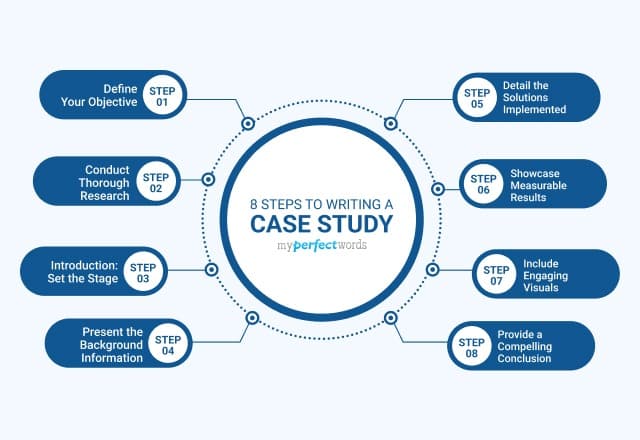

Here are the basic steps to writing a good case study.

1. Identify your goal

Start by defining exactly who your case study will be designed to help. Case studies are about specific instances where a company works with a customer to achieve a goal. Identify which customers are likely to have these goals, as well as other needs the story should cover to appeal to them.

The answer is often found in one of the buyer personas that have been constructed as part of your larger marketing strategy. This can include anything from new leads generated by the marketing team to long-term customers that are being pressed for cross-sell opportunities. In all of these cases, demonstrating value through a relatable customer success story can be part of the solution to conversion.

2. Choose your client or subject

Who you highlight matters. Case studies tie brands together that might otherwise not cross paths. A writer will want to ensure that the highlighted customer aligns with their own company’s brand identity and offerings. Look for a customer with positive name recognition who has had great success with a product or service and is willing to be an advocate.

The client should also match up with the identified target audience. Whichever company or individual is selected should be a reflection of other potential customers who can see themselves in similar circumstances, having the same problems and possible solutions.

Some of the most compelling case studies feature customers who:

- Switch from one product or service to another while naming competitors that missed the mark.

- Experience measurable results that are relatable to others in a specific industry.

- Represent well-known brands and recognizable names that are likely to compel action.

- Advocate for a product or service as a champion and are well-versed in its advantages.

Whoever or whatever customer is selected, marketers must ensure they have the permission of the company involved before getting started. Some brands have strict review and approval procedures for any official marketing or promotional materials that include their name. Acquiring those approvals in advance will prevent any miscommunication or wasted effort if there is an issue with their legal or compliance teams.

3. Conduct research and compile data

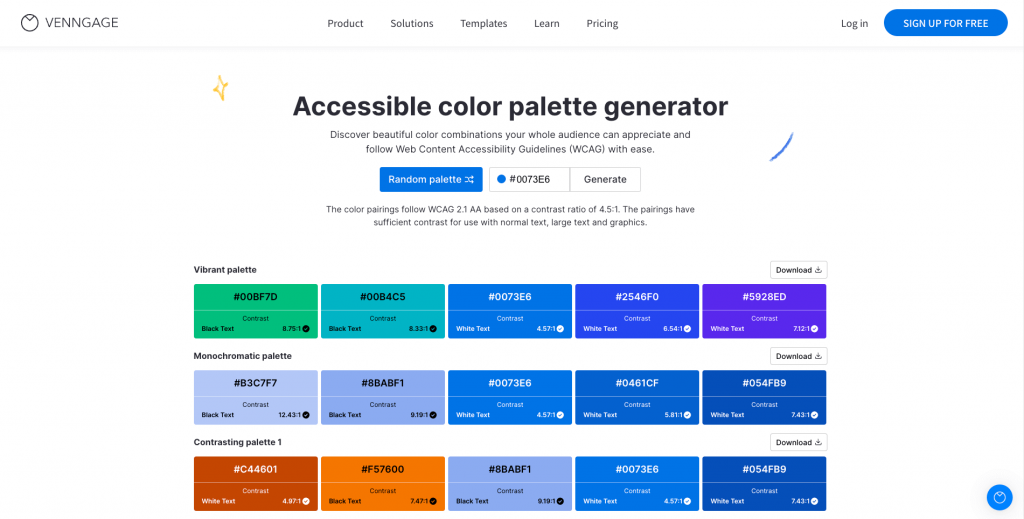

Substantiating the claims made in a case study — either by the marketing team or customers themselves — adds validity to the story. To do this, include data and feedback from the client that defines what success looks like. This can be anything from demonstrating return on investment (ROI) to a specific metric the customer was striving to improve. Case studies should prove how an outcome was achieved and show tangible results that indicate to the customer that your solution is the right one.

This step could also include customer interviews. Make sure that the people being interviewed are key stakeholders in the purchase decision or deployment and use of the product or service that is being highlighted. Content writers should work off a set list of questions prepared in advance. It can be helpful to share these with the interviewees beforehand so they have time to consider and craft their responses. One of the best interview tactics to keep in mind is to ask questions where yes and no are not natural answers. This way, your subject will provide more open-ended responses that produce more meaningful content.

4. Choose the right format

There are a number of different ways to format a case study. Depending on what you hope to achieve, one style will be better than another. However, there are some common elements to include, such as:

- An engaging headline

- A subject and customer introduction

- The unique challenge or challenges the customer faced

- The solution the customer used to solve the problem

- The results achieved

- Data and statistics to back up claims of success

- A strong call to action (CTA) to engage with the vendor

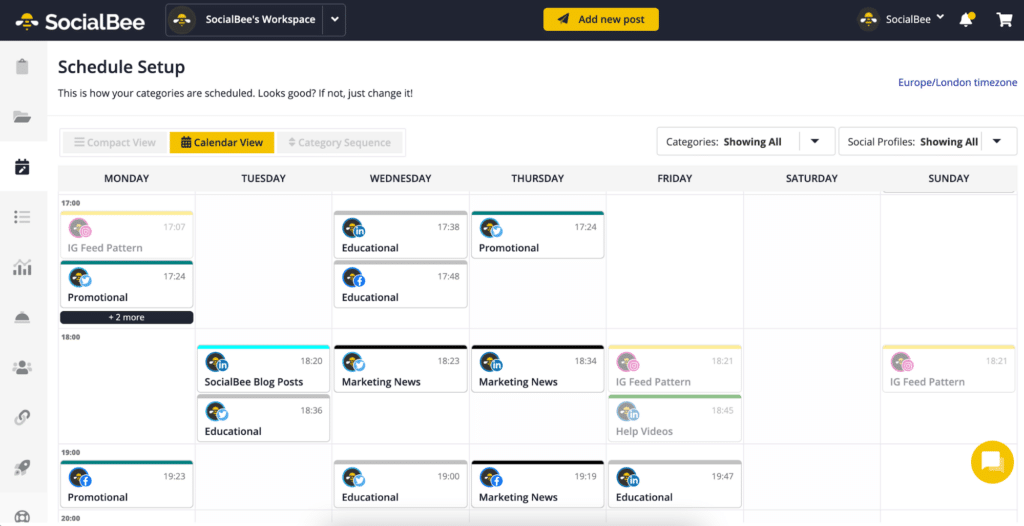

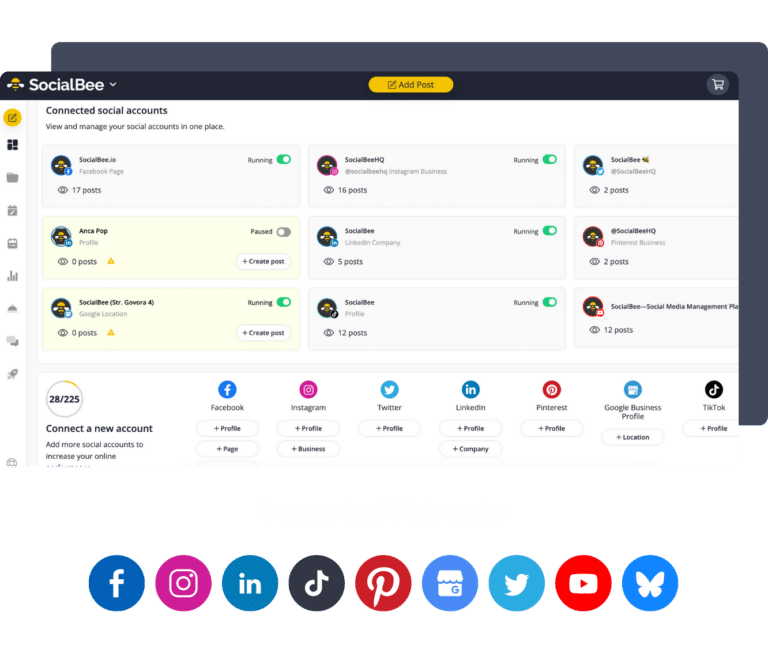

It’s also important to note that while case studies are traditionally written as stories, they don’t have to be in a written format. Some companies choose to get more creative with their case studies and produce multimedia content, depending on their audience and objectives. Case study formats can include traditional print stories, interactive web or social content, data-heavy infographics, professionally shot videos, podcasts, and more.

5. Write your case study

We’ll go into more detail later about how exactly to write a case study, including templates and examples. Generally speaking, though, there are a few things to keep in mind when writing your case study.

- Be clear and concise. Readers want to get to the point of the story quickly and easily, and they’ll be looking to see themselves reflected in the story right from the start.

- Provide a big picture. Always make sure to explain who the client is, their goals, and how they achieved success in a short introduction to engage the reader.

- Construct a clear narrative. Stick to the story from the perspective of the customer and what they needed to solve instead of just listing product features or benefits.

- Leverage graphics. Incorporating infographics, charts, and sidebars can be a more engaging and eye-catching way to share key statistics and data in readable ways.

- Offer the right amount of detail. Most case studies are one or two pages with clear sections that a reader can skim to find the information most important to them.

- Include data to support claims. Show real results — both facts and figures and customer quotes — to demonstrate credibility and prove the solution works.

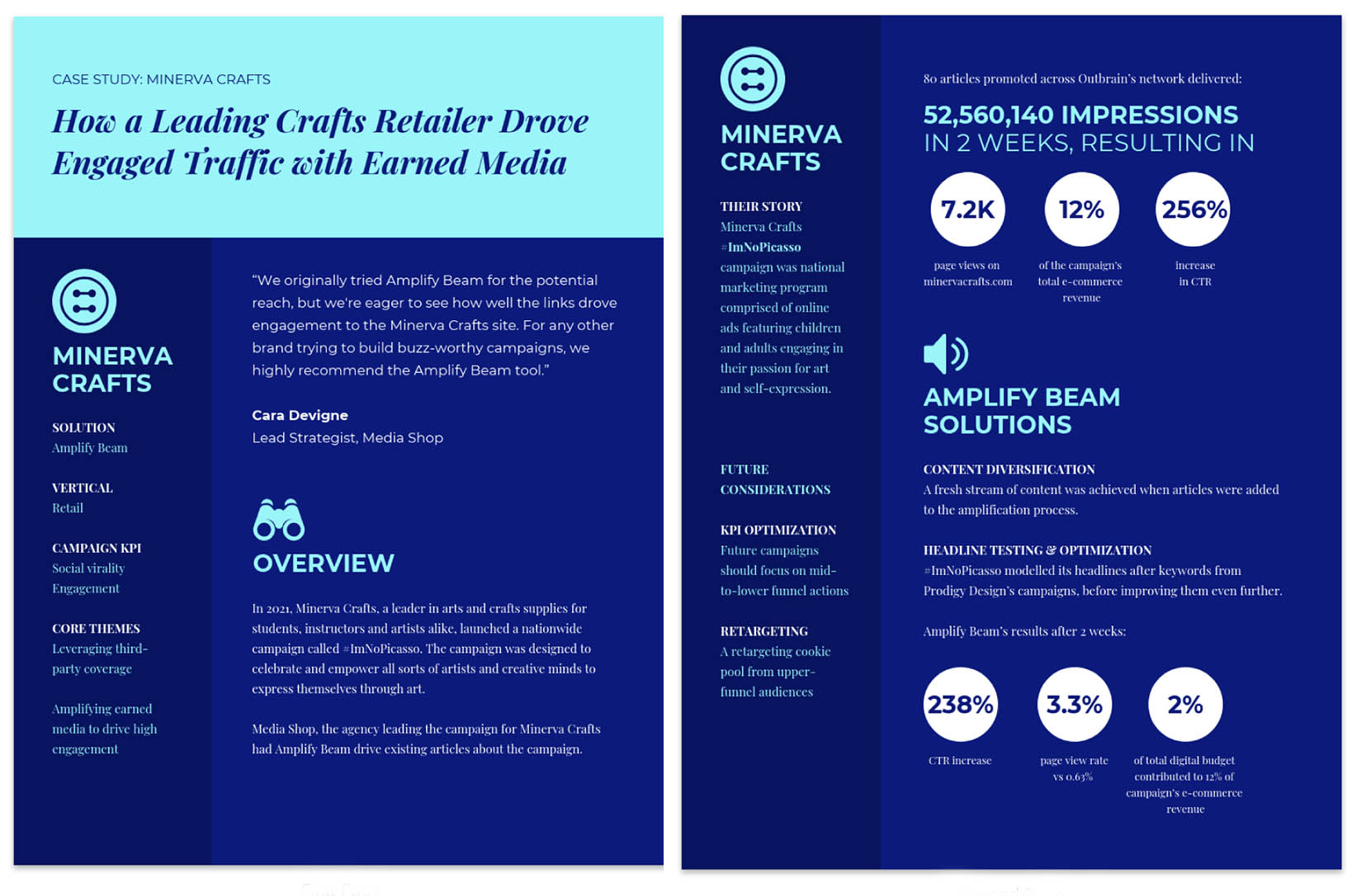

6. Promote your story

Marketers have a number of options for distribution of a freshly minted case study. Many brands choose to publish case studies on their website and post them on social media. This can help support SEO and organic content strategies while also boosting company credibility and trust as visitors see that other businesses have used the product or service.

Marketers are always looking for quality content they can use for lead generation. Consider offering a case study as gated content behind a form on a landing page or as an offer in an email message. One great way to do this is to summarize the content and tease the full story available for download after the user takes an action.

Sales teams can also leverage case studies, so be sure they are aware that the assets exist once they’re published. Especially when it comes to larger B2B sales, companies often ask for examples of similar customer challenges that have been solved.

Now that you’ve learned a bit about case studies and what they should include, you may be wondering how to start creating great customer story content. Here are a couple of templates you can use to structure your case study.

Template 1 — Challenge-solution-result format

- Start with an engaging title. This should be fewer than 70 characters long for SEO best practices. One of the best ways to approach the title is to include the customer’s name and a hint at the challenge they overcame in the end.

- Create an introduction. Lead with an explanation as to who the customer is, the need they had, and the opportunity they found with a specific product or solution. Writers can also suggest the success the customer experienced with the solution they chose.

- Present the challenge. This should be several paragraphs long and explain the problem the customer faced and the issues they were trying to solve. Details should tie into the company’s products and services naturally. This section needs to be the most relatable to the reader so they can picture themselves in a similar situation.

- Share the solution. Explain which product or service offered was the ideal fit for the customer and why. Feel free to delve into their experience setting up, purchasing, and onboarding the solution.

- Explain the results. Demonstrate the impact of the solution they chose by backing up their positive experience with data. Fill in with customer quotes and tangible, measurable results that show the effect of their choice.

- Ask for action. Include a CTA at the end of the case study that invites readers to reach out for more information, try a demo, or learn more — to nurture them further in the marketing pipeline. What you ask of the reader should tie directly into the goals that were established for the case study in the first place.

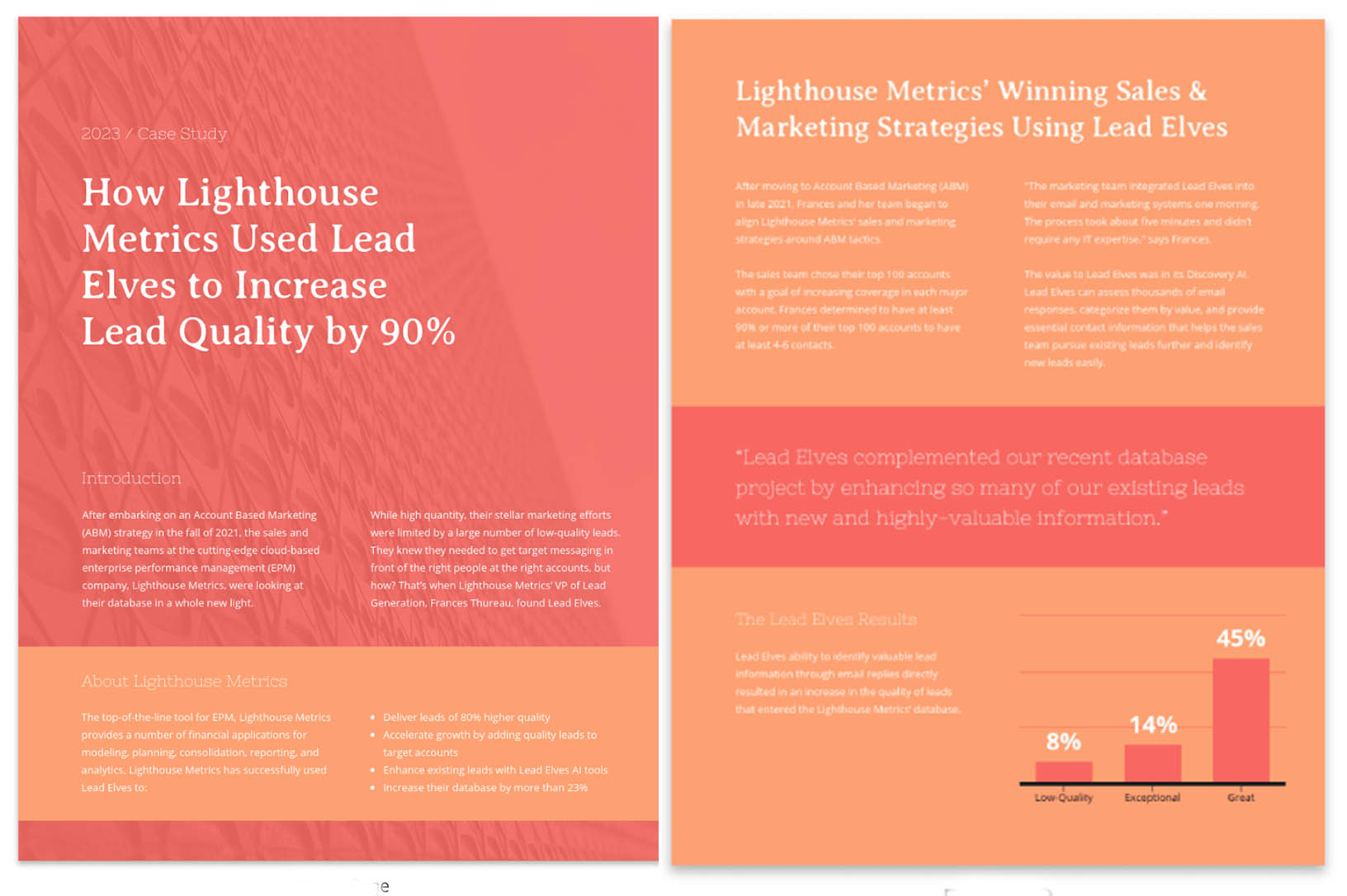

Template 2 — Data-driven format

- Start with an engaging title. Be sure to include a statistic or data point in the first 70 characters. Again, it’s best to include the customer’s name as part of the title.

- Create an overview. Share the customer’s background and a short version of the challenge they faced. Present the reason a particular product or service was chosen, and feel free to include quotes from the customer about their selection process.

- Present data point 1. Isolate the first metric that the customer used to define success and explain how the product or solution helped to achieve this goal. Provide data points and quotes to substantiate the claim that success was achieved.

- Present data point 2. Isolate the second metric that the customer used to define success and explain what the product or solution did to achieve this goal. Provide data points and quotes to substantiate the claim that success was achieved.

- Present data point 3. Isolate the final metric that the customer used to define success and explain what the product or solution did to achieve this goal. Provide data points and quotes to substantiate the claim that success was achieved.

- Summarize the results. Reiterate the fact that the customer was able to achieve success thanks to a specific product or service. Include quotes and statements that reflect customer satisfaction and suggest they plan to continue using the solution.

- Ask for action. Include a CTA at the end of the case study that asks readers to reach out for more information, try a demo, or learn more — to further nurture them in the marketing pipeline. Again, remember that this is where marketers can look to convert their content into action with the customer.

While templates are helpful, seeing a case study in action can also be a great way to learn. Here are some examples of how Adobe customers have experienced success.

Juniper Networks

One example is the Adobe and Juniper Networks case study , which puts the reader in the customer’s shoes. The beginning of the story quickly orients the reader so that they know exactly who the article is about and what they were trying to achieve. Solutions are outlined in a way that shows Adobe Experience Manager is the best choice and a natural fit for the customer. Along the way, quotes from the client are incorporated to help add validity to the statements. The results in the case study are conveyed with clear evidence of scale and volume using tangible data.

The story of Lenovo’s journey with Adobe is one that spans years of planning, implementation, and rollout. The Lenovo case study does a great job of consolidating all of this into a relatable journey that other enterprise organizations can see themselves taking, despite the project size. This case study also features descriptive headers and compelling visual elements that engage the reader and strengthen the content.

Tata Consulting

When it comes to using data to show customer results, this case study does an excellent job of conveying details and numbers in an easy-to-digest manner. Bullet points at the start break up the content while also helping the reader understand exactly what the case study will be about. Tata Consulting used Adobe to deliver elevated, engaging content experiences for a large telecommunications client of its own — an objective that’s relatable for a lot of companies.

Case studies are a vital tool for any marketing team as they enable you to demonstrate the value of your company’s products and services to others. They help marketers do their job and add credibility to a brand trying to promote its solutions by using the experiences and stories of real customers.

When you’re ready to get started with a case study:

- Think about a few goals you’d like to accomplish with your content.

- Make a list of successful clients that would be strong candidates for a case study.

- Reach out to the client to get their approval and conduct an interview.

- Gather the data to present an engaging and effective customer story.

Adobe can help

There are several Adobe products that can help you craft compelling case studies. Adobe Experience Platform helps you collect data and deliver great customer experiences across every channel. Once you’ve created your case studies, Experience Platform will help you deliver the right information to the right customer at the right time for maximum impact.

To learn more, watch the Adobe Experience Platform story .

Keep in mind that the best case studies are backed by data. That’s where Adobe Real-Time Customer Data Platform and Adobe Analytics come into play. With Real-Time CDP, you can gather the data you need to build a great case study and target specific customers to deliver the content to the right audience at the perfect moment.

Watch the Real-Time CDP overview video to learn more.

Finally, Adobe Analytics turns real-time data into real-time insights. It helps your business collect and synthesize data from multiple platforms to make more informed decisions and create the best case study possible.

Request a demo to learn more about Adobe Analytics.

https://business.adobe.com/blog/perspectives/b2b-ecommerce-10-case-studies-inspire-you

https://business.adobe.com/blog/basics/business-case

https://business.adobe.com/blog/basics/what-is-real-time-analytics

All You Wanted to Know About How to Write a Case Study

What do you study in your college? If you are a psychology, sociology, or anthropology student, we bet you might be familiar with what a case study is. This research method is used to study a certain person, group, or situation. In this guide from our dissertation writing service , you will learn how to write a case study professionally, from researching to citing sources properly. Also, we will explore different types of case studies and show you examples — so that you won’t have any other questions left.

What Is a Case Study?

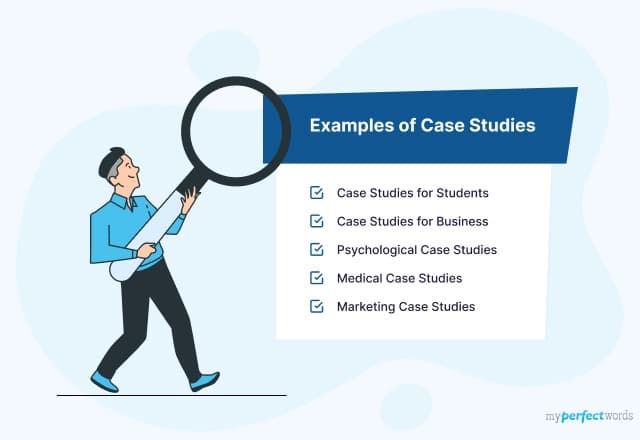

A case study is a subcategory of research design which investigates problems and offers solutions. Case studies can range from academic research studies to corporate promotional tools trying to sell an idea—their scope is quite vast.

What Is the Difference Between a Research Paper and a Case Study?

While research papers turn the reader’s attention to a certain problem, case studies go even further. Case study guidelines require students to pay attention to details, examining issues closely and in-depth using different research methods. For example, case studies may be used to examine court cases if you study Law, or a patient's health history if you study Medicine. Case studies are also used in Marketing, which are thorough, empirically supported analysis of a good or service's performance. Well-designed case studies can be valuable for prospective customers as they can identify and solve the potential customers pain point.

Case studies involve a lot of storytelling – they usually examine particular cases for a person or a group of people. This method of research is very helpful, as it is very practical and can give a lot of hands-on information. Most commonly, the length of the case study is about 500-900 words, which is much less than the length of an average research paper.

The structure of a case study is very similar to storytelling. It has a protagonist or main character, which in your case is actually a problem you are trying to solve. You can use the system of 3 Acts to make it a compelling story. It should have an introduction, rising action, a climax where transformation occurs, falling action, and a solution.

Here is a rough formula for you to use in your case study:

Problem (Act I): > Solution (Act II) > Result (Act III) > Conclusion.

Types of Case Studies

The purpose of a case study is to provide detailed reports on an event, an institution, a place, future customers, or pretty much anything. There are a few common types of case study, but the type depends on the topic. The following are the most common domains where case studies are needed:

- Historical case studies are great to learn from. Historical events have a multitude of source info offering different perspectives. There are always modern parallels where these perspectives can be applied, compared, and thoroughly analyzed.

- Problem-oriented case studies are usually used for solving problems. These are often assigned as theoretical situations where you need to immerse yourself in the situation to examine it. Imagine you’re working for a startup and you’ve just noticed a significant flaw in your product’s design. Before taking it to the senior manager, you want to do a comprehensive study on the issue and provide solutions. On a greater scale, problem-oriented case studies are a vital part of relevant socio-economic discussions.

- Cumulative case studies collect information and offer comparisons. In business, case studies are often used to tell people about the value of a product.

- Critical case studies explore the causes and effects of a certain case.

- Illustrative case studies describe certain events, investigating outcomes and lessons learned.

Need a compelling case study? EssayPro has got you covered. Our experts are ready to provide you with detailed, insightful case studies that capture the essence of real-world scenarios. Elevate your academic work with our professional assistance.

Case Study Format

The case study format is typically made up of eight parts:

- Executive Summary. Explain what you will examine in the case study. Write an overview of the field you’re researching. Make a thesis statement and sum up the results of your observation in a maximum of 2 sentences.

- Background. Provide background information and the most relevant facts. Isolate the issues.

- Case Evaluation. Isolate the sections of the study you want to focus on. In it, explain why something is working or is not working.

- Proposed Solutions. Offer realistic ways to solve what isn’t working or how to improve its current condition. Explain why these solutions work by offering testable evidence.

- Conclusion. Summarize the main points from the case evaluations and proposed solutions. 6. Recommendations. Talk about the strategy that you should choose. Explain why this choice is the most appropriate.

- Implementation. Explain how to put the specific strategies into action.

- References. Provide all the citations.

How to Write a Case Study

Let's discover how to write a case study.

Setting Up the Research

When writing a case study, remember that research should always come first. Reading many different sources and analyzing other points of view will help you come up with more creative solutions. You can also conduct an actual interview to thoroughly investigate the customer story that you'll need for your case study. Including all of the necessary research, writing a case study may take some time. The research process involves doing the following:

- Define your objective. Explain the reason why you’re presenting your subject. Figure out where you will feature your case study; whether it is written, on video, shown as an infographic, streamed as a podcast, etc.

- Determine who will be the right candidate for your case study. Get permission, quotes, and other features that will make your case study effective. Get in touch with your candidate to see if they approve of being part of your work. Study that candidate’s situation and note down what caused it.

- Identify which various consequences could result from the situation. Follow these guidelines on how to start a case study: surf the net to find some general information you might find useful.

- Make a list of credible sources and examine them. Seek out important facts and highlight problems. Always write down your ideas and make sure to brainstorm.

- Focus on several key issues – why they exist, and how they impact your research subject. Think of several unique solutions. Draw from class discussions, readings, and personal experience. When writing a case study, focus on the best solution and explore it in depth. After having all your research in place, writing a case study will be easy. You may first want to check the rubric and criteria of your assignment for the correct case study structure.

Read Also: ' WHAT IS A CREDIBLE SOURCES ?'

Although your instructor might be looking at slightly different criteria, every case study rubric essentially has the same standards. Your professor will want you to exhibit 8 different outcomes:

- Correctly identify the concepts, theories, and practices in the discipline.

- Identify the relevant theories and principles associated with the particular study.

- Evaluate legal and ethical principles and apply them to your decision-making.

- Recognize the global importance and contribution of your case.

- Construct a coherent summary and explanation of the study.

- Demonstrate analytical and critical-thinking skills.

- Explain the interrelationships between the environment and nature.

- Integrate theory and practice of the discipline within the analysis.

Need Case Study DONE FAST?

Pick a topic, tell us your requirements and get your paper on time.

Case Study Outline

Let's look at the structure of an outline based on the issue of the alcoholic addiction of 30 people.

Introduction

- Statement of the issue: Alcoholism is a disease rather than a weakness of character.

- Presentation of the problem: Alcoholism is affecting more than 14 million people in the USA, which makes it the third most common mental illness there.

- Explanation of the terms: In the past, alcoholism was commonly referred to as alcohol dependence or alcohol addiction. Alcoholism is now the more severe stage of this addiction in the disorder spectrum.

- Hypotheses: Drinking in excess can lead to the use of other drugs.

- Importance of your story: How the information you present can help people with their addictions.

- Background of the story: Include an explanation of why you chose this topic.

- Presentation of analysis and data: Describe the criteria for choosing 30 candidates, the structure of the interview, and the outcomes.

- Strong argument 1: ex. X% of candidates dealing with anxiety and depression...

- Strong argument 2: ex. X amount of people started drinking by their mid-teens.

- Strong argument 3: ex. X% of respondents’ parents had issues with alcohol.

- Concluding statement: I have researched if alcoholism is a disease and found out that…

- Recommendations: Ways and actions for preventing alcohol use.

Writing a Case Study Draft

After you’ve done your case study research and written the outline, it’s time to focus on the draft. In a draft, you have to develop and write your case study by using: the data which you collected throughout the research, interviews, and the analysis processes that were undertaken. Follow these rules for the draft:

- Your draft should contain at least 4 sections: an introduction; a body where you should include background information, an explanation of why you decided to do this case study, and a presentation of your main findings; a conclusion where you present data; and references.

- In the introduction, you should set the pace very clearly. You can even raise a question or quote someone you interviewed in the research phase. It must provide adequate background information on the topic. The background may include analyses of previous studies on your topic. Include the aim of your case here as well. Think of it as a thesis statement. The aim must describe the purpose of your work—presenting the issues that you want to tackle. Include background information, such as photos or videos you used when doing the research.

- Describe your unique research process, whether it was through interviews, observations, academic journals, etc. The next point includes providing the results of your research. Tell the audience what you found out. Why is this important, and what could be learned from it? Discuss the real implications of the problem and its significance in the world.

- Include quotes and data (such as findings, percentages, and awards). This will add a personal touch and better credibility to the case you present. Explain what results you find during your interviews in regards to the problem and how it developed. Also, write about solutions which have already been proposed by other people who have already written about this case.

- At the end of your case study, you should offer possible solutions, but don’t worry about solving them yourself.

Use Data to Illustrate Key Points in Your Case Study

Even though your case study is a story, it should be based on evidence. Use as much data as possible to illustrate your point. Without the right data, your case study may appear weak and the readers may not be able to relate to your issue as much as they should. Let's see the examples from essay writing service :

With data: Alcoholism is affecting more than 14 million people in the USA, which makes it the third most common mental illness there. Without data: A lot of people suffer from alcoholism in the United States.

Try to include as many credible sources as possible. You may have terms or sources that could be hard for other cultures to understand. If this is the case, you should include them in the appendix or Notes for the Instructor or Professor.

Finalizing the Draft: Checklist

After you finish drafting your case study, polish it up by answering these ‘ask yourself’ questions and think about how to end your case study:

- Check that you follow the correct case study format, also in regards to text formatting.

- Check that your work is consistent with its referencing and citation style.

- Micro-editing — check for grammar and spelling issues.

- Macro-editing — does ‘the big picture’ come across to the reader? Is there enough raw data, such as real-life examples or personal experiences? Have you made your data collection process completely transparent? Does your analysis provide a clear conclusion, allowing for further research and practice?

Problems to avoid:

- Overgeneralization – Do not go into further research that deviates from the main problem.

- Failure to Document Limitations – Just as you have to clearly state the limitations of a general research study, you must describe the specific limitations inherent in the subject of analysis.

- Failure to Extrapolate All Possible Implications – Just as you don't want to over-generalize from your case study findings, you also have to be thorough in the consideration of all possible outcomes or recommendations derived from your findings.

How to Create a Title Page and Cite a Case Study

Let's see how to create an awesome title page.

Your title page depends on the prescribed citation format. The title page should include:

- A title that attracts some attention and describes your study

- The title should have the words “case study” in it

- The title should range between 5-9 words in length

- Your name and contact information

- Your finished paper should be only 500 to 1,500 words in length.With this type of assignment, write effectively and avoid fluff

Here is a template for the APA and MLA format title page:

There are some cases when you need to cite someone else's study in your own one – therefore, you need to master how to cite a case study. A case study is like a research paper when it comes to citations. You can cite it like you cite a book, depending on what style you need.

Citation Example in MLA Hill, Linda, Tarun Khanna, and Emily A. Stecker. HCL Technologies. Boston: Harvard Business Publishing, 2008. Print.

Citation Example in APA Hill, L., Khanna, T., & Stecker, E. A. (2008). HCL Technologies. Boston: Harvard Business Publishing.

Citation Example in Chicago Hill, Linda, Tarun Khanna, and Emily A. Stecker. HCL Technologies.

Case Study Examples

To give you an idea of a professional case study example, we gathered and linked some below.

Eastman Kodak Case Study

Case Study Example: Audi Trains Mexican Autoworkers in Germany

To conclude, a case study is one of the best methods of getting an overview of what happened to a person, a group, or a situation in practice. It allows you to have an in-depth glance at the real-life problems that businesses, healthcare industry, criminal justice, etc. may face. This insight helps us look at such situations in a different light. This is because we see scenarios that we otherwise would not, without necessarily being there. If you need custom essays , try our research paper writing services .

Get Help Form Qualified Writers

Crafting a case study is not easy. You might want to write one of high quality, but you don’t have the time or expertise. If you’re having trouble with your case study, help with essay request - we'll help. EssayPro writers have read and written countless case studies and are experts in endless disciplines. Request essay writing, editing, or proofreading assistance from our custom case study writing service , and all of your worries will be gone.

Don't Know Where to Start?

Crafting a case study is not easy. You might want to write one of high quality, but you don’t have the time or expertise. Request ' write my case study ' assistance from our service.

What Is A Case Study?

How to cite a case study in apa, how to write a case study, related articles.

.webp)

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Assignments

- Annotated Bibliography

- Analyzing a Scholarly Journal Article

- Group Presentations

- Dealing with Nervousness

- Using Visual Aids

- Grading Someone Else's Paper

- Types of Structured Group Activities

- Group Project Survival Skills

- Leading a Class Discussion

- Multiple Book Review Essay

- Reviewing Collected Works

- Writing a Case Analysis Paper

- Writing a Case Study

- About Informed Consent

- Writing Field Notes

- Writing a Policy Memo

- Writing a Reflective Paper

- Writing a Research Proposal

- Generative AI and Writing

- Acknowledgments

A case study research paper examines a person, place, event, condition, phenomenon, or other type of subject of analysis in order to extrapolate key themes and results that help predict future trends, illuminate previously hidden issues that can be applied to practice, and/or provide a means for understanding an important research problem with greater clarity. A case study research paper usually examines a single subject of analysis, but case study papers can also be designed as a comparative investigation that shows relationships between two or more subjects. The methods used to study a case can rest within a quantitative, qualitative, or mixed-method investigative paradigm.

Case Studies. Writing@CSU. Colorado State University; Mills, Albert J. , Gabrielle Durepos, and Eiden Wiebe, editors. Encyclopedia of Case Study Research . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, 2010 ; “What is a Case Study?” In Swanborn, Peter G. Case Study Research: What, Why and How? London: SAGE, 2010.

How to Approach Writing a Case Study Research Paper

General information about how to choose a topic to investigate can be found under the " Choosing a Research Problem " tab in the Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper writing guide. Review this page because it may help you identify a subject of analysis that can be investigated using a case study design.

However, identifying a case to investigate involves more than choosing the research problem . A case study encompasses a problem contextualized around the application of in-depth analysis, interpretation, and discussion, often resulting in specific recommendations for action or for improving existing conditions. As Seawright and Gerring note, practical considerations such as time and access to information can influence case selection, but these issues should not be the sole factors used in describing the methodological justification for identifying a particular case to study. Given this, selecting a case includes considering the following:

- The case represents an unusual or atypical example of a research problem that requires more in-depth analysis? Cases often represent a topic that rests on the fringes of prior investigations because the case may provide new ways of understanding the research problem. For example, if the research problem is to identify strategies to improve policies that support girl's access to secondary education in predominantly Muslim nations, you could consider using Azerbaijan as a case study rather than selecting a more obvious nation in the Middle East. Doing so may reveal important new insights into recommending how governments in other predominantly Muslim nations can formulate policies that support improved access to education for girls.

- The case provides important insight or illuminate a previously hidden problem? In-depth analysis of a case can be based on the hypothesis that the case study will reveal trends or issues that have not been exposed in prior research or will reveal new and important implications for practice. For example, anecdotal evidence may suggest drug use among homeless veterans is related to their patterns of travel throughout the day. Assuming prior studies have not looked at individual travel choices as a way to study access to illicit drug use, a case study that observes a homeless veteran could reveal how issues of personal mobility choices facilitate regular access to illicit drugs. Note that it is important to conduct a thorough literature review to ensure that your assumption about the need to reveal new insights or previously hidden problems is valid and evidence-based.

- The case challenges and offers a counter-point to prevailing assumptions? Over time, research on any given topic can fall into a trap of developing assumptions based on outdated studies that are still applied to new or changing conditions or the idea that something should simply be accepted as "common sense," even though the issue has not been thoroughly tested in current practice. A case study analysis may offer an opportunity to gather evidence that challenges prevailing assumptions about a research problem and provide a new set of recommendations applied to practice that have not been tested previously. For example, perhaps there has been a long practice among scholars to apply a particular theory in explaining the relationship between two subjects of analysis. Your case could challenge this assumption by applying an innovative theoretical framework [perhaps borrowed from another discipline] to explore whether this approach offers new ways of understanding the research problem. Taking a contrarian stance is one of the most important ways that new knowledge and understanding develops from existing literature.

- The case provides an opportunity to pursue action leading to the resolution of a problem? Another way to think about choosing a case to study is to consider how the results from investigating a particular case may result in findings that reveal ways in which to resolve an existing or emerging problem. For example, studying the case of an unforeseen incident, such as a fatal accident at a railroad crossing, can reveal hidden issues that could be applied to preventative measures that contribute to reducing the chance of accidents in the future. In this example, a case study investigating the accident could lead to a better understanding of where to strategically locate additional signals at other railroad crossings so as to better warn drivers of an approaching train, particularly when visibility is hindered by heavy rain, fog, or at night.

- The case offers a new direction in future research? A case study can be used as a tool for an exploratory investigation that highlights the need for further research about the problem. A case can be used when there are few studies that help predict an outcome or that establish a clear understanding about how best to proceed in addressing a problem. For example, after conducting a thorough literature review [very important!], you discover that little research exists showing the ways in which women contribute to promoting water conservation in rural communities of east central Africa. A case study of how women contribute to saving water in a rural village of Uganda can lay the foundation for understanding the need for more thorough research that documents how women in their roles as cooks and family caregivers think about water as a valuable resource within their community. This example of a case study could also point to the need for scholars to build new theoretical frameworks around the topic [e.g., applying feminist theories of work and family to the issue of water conservation].

Eisenhardt, Kathleen M. “Building Theories from Case Study Research.” Academy of Management Review 14 (October 1989): 532-550; Emmel, Nick. Sampling and Choosing Cases in Qualitative Research: A Realist Approach . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, 2013; Gerring, John. “What Is a Case Study and What Is It Good for?” American Political Science Review 98 (May 2004): 341-354; Mills, Albert J. , Gabrielle Durepos, and Eiden Wiebe, editors. Encyclopedia of Case Study Research . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, 2010; Seawright, Jason and John Gerring. "Case Selection Techniques in Case Study Research." Political Research Quarterly 61 (June 2008): 294-308.

Structure and Writing Style

The purpose of a paper in the social sciences designed around a case study is to thoroughly investigate a subject of analysis in order to reveal a new understanding about the research problem and, in so doing, contributing new knowledge to what is already known from previous studies. In applied social sciences disciplines [e.g., education, social work, public administration, etc.], case studies may also be used to reveal best practices, highlight key programs, or investigate interesting aspects of professional work.

In general, the structure of a case study research paper is not all that different from a standard college-level research paper. However, there are subtle differences you should be aware of. Here are the key elements to organizing and writing a case study research paper.

I. Introduction

As with any research paper, your introduction should serve as a roadmap for your readers to ascertain the scope and purpose of your study . The introduction to a case study research paper, however, should not only describe the research problem and its significance, but you should also succinctly describe why the case is being used and how it relates to addressing the problem. The two elements should be linked. With this in mind, a good introduction answers these four questions:

- What is being studied? Describe the research problem and describe the subject of analysis [the case] you have chosen to address the problem. Explain how they are linked and what elements of the case will help to expand knowledge and understanding about the problem.

- Why is this topic important to investigate? Describe the significance of the research problem and state why a case study design and the subject of analysis that the paper is designed around is appropriate in addressing the problem.

- What did we know about this topic before I did this study? Provide background that helps lead the reader into the more in-depth literature review to follow. If applicable, summarize prior case study research applied to the research problem and why it fails to adequately address the problem. Describe why your case will be useful. If no prior case studies have been used to address the research problem, explain why you have selected this subject of analysis.

- How will this study advance new knowledge or new ways of understanding? Explain why your case study will be suitable in helping to expand knowledge and understanding about the research problem.

Each of these questions should be addressed in no more than a few paragraphs. Exceptions to this can be when you are addressing a complex research problem or subject of analysis that requires more in-depth background information.

II. Literature Review

The literature review for a case study research paper is generally structured the same as it is for any college-level research paper. The difference, however, is that the literature review is focused on providing background information and enabling historical interpretation of the subject of analysis in relation to the research problem the case is intended to address . This includes synthesizing studies that help to:

- Place relevant works in the context of their contribution to understanding the case study being investigated . This would involve summarizing studies that have used a similar subject of analysis to investigate the research problem. If there is literature using the same or a very similar case to study, you need to explain why duplicating past research is important [e.g., conditions have changed; prior studies were conducted long ago, etc.].

- Describe the relationship each work has to the others under consideration that informs the reader why this case is applicable . Your literature review should include a description of any works that support using the case to investigate the research problem and the underlying research questions.

- Identify new ways to interpret prior research using the case study . If applicable, review any research that has examined the research problem using a different research design. Explain how your use of a case study design may reveal new knowledge or a new perspective or that can redirect research in an important new direction.

- Resolve conflicts amongst seemingly contradictory previous studies . This refers to synthesizing any literature that points to unresolved issues of concern about the research problem and describing how the subject of analysis that forms the case study can help resolve these existing contradictions.

- Point the way in fulfilling a need for additional research . Your review should examine any literature that lays a foundation for understanding why your case study design and the subject of analysis around which you have designed your study may reveal a new way of approaching the research problem or offer a perspective that points to the need for additional research.

- Expose any gaps that exist in the literature that the case study could help to fill . Summarize any literature that not only shows how your subject of analysis contributes to understanding the research problem, but how your case contributes to a new way of understanding the problem that prior research has failed to do.

- Locate your own research within the context of existing literature [very important!] . Collectively, your literature review should always place your case study within the larger domain of prior research about the problem. The overarching purpose of reviewing pertinent literature in a case study paper is to demonstrate that you have thoroughly identified and synthesized prior studies in relation to explaining the relevance of the case in addressing the research problem.

III. Method

In this section, you explain why you selected a particular case [i.e., subject of analysis] and the strategy you used to identify and ultimately decide that your case was appropriate in addressing the research problem. The way you describe the methods used varies depending on the type of subject of analysis that constitutes your case study.

If your subject of analysis is an incident or event . In the social and behavioral sciences, the event or incident that represents the case to be studied is usually bounded by time and place, with a clear beginning and end and with an identifiable location or position relative to its surroundings. The subject of analysis can be a rare or critical event or it can focus on a typical or regular event. The purpose of studying a rare event is to illuminate new ways of thinking about the broader research problem or to test a hypothesis. Critical incident case studies must describe the method by which you identified the event and explain the process by which you determined the validity of this case to inform broader perspectives about the research problem or to reveal new findings. However, the event does not have to be a rare or uniquely significant to support new thinking about the research problem or to challenge an existing hypothesis. For example, Walo, Bull, and Breen conducted a case study to identify and evaluate the direct and indirect economic benefits and costs of a local sports event in the City of Lismore, New South Wales, Australia. The purpose of their study was to provide new insights from measuring the impact of a typical local sports event that prior studies could not measure well because they focused on large "mega-events." Whether the event is rare or not, the methods section should include an explanation of the following characteristics of the event: a) when did it take place; b) what were the underlying circumstances leading to the event; and, c) what were the consequences of the event in relation to the research problem.

If your subject of analysis is a person. Explain why you selected this particular individual to be studied and describe what experiences they have had that provide an opportunity to advance new understandings about the research problem. Mention any background about this person which might help the reader understand the significance of their experiences that make them worthy of study. This includes describing the relationships this person has had with other people, institutions, and/or events that support using them as the subject for a case study research paper. It is particularly important to differentiate the person as the subject of analysis from others and to succinctly explain how the person relates to examining the research problem [e.g., why is one politician in a particular local election used to show an increase in voter turnout from any other candidate running in the election]. Note that these issues apply to a specific group of people used as a case study unit of analysis [e.g., a classroom of students].

If your subject of analysis is a place. In general, a case study that investigates a place suggests a subject of analysis that is unique or special in some way and that this uniqueness can be used to build new understanding or knowledge about the research problem. A case study of a place must not only describe its various attributes relevant to the research problem [e.g., physical, social, historical, cultural, economic, political], but you must state the method by which you determined that this place will illuminate new understandings about the research problem. It is also important to articulate why a particular place as the case for study is being used if similar places also exist [i.e., if you are studying patterns of homeless encampments of veterans in open spaces, explain why you are studying Echo Park in Los Angeles rather than Griffith Park?]. If applicable, describe what type of human activity involving this place makes it a good choice to study [e.g., prior research suggests Echo Park has more homeless veterans].

If your subject of analysis is a phenomenon. A phenomenon refers to a fact, occurrence, or circumstance that can be studied or observed but with the cause or explanation to be in question. In this sense, a phenomenon that forms your subject of analysis can encompass anything that can be observed or presumed to exist but is not fully understood. In the social and behavioral sciences, the case usually focuses on human interaction within a complex physical, social, economic, cultural, or political system. For example, the phenomenon could be the observation that many vehicles used by ISIS fighters are small trucks with English language advertisements on them. The research problem could be that ISIS fighters are difficult to combat because they are highly mobile. The research questions could be how and by what means are these vehicles used by ISIS being supplied to the militants and how might supply lines to these vehicles be cut off? How might knowing the suppliers of these trucks reveal larger networks of collaborators and financial support? A case study of a phenomenon most often encompasses an in-depth analysis of a cause and effect that is grounded in an interactive relationship between people and their environment in some way.

NOTE: The choice of the case or set of cases to study cannot appear random. Evidence that supports the method by which you identified and chose your subject of analysis should clearly support investigation of the research problem and linked to key findings from your literature review. Be sure to cite any studies that helped you determine that the case you chose was appropriate for examining the problem.

IV. Discussion

The main elements of your discussion section are generally the same as any research paper, but centered around interpreting and drawing conclusions about the key findings from your analysis of the case study. Note that a general social sciences research paper may contain a separate section to report findings. However, in a paper designed around a case study, it is common to combine a description of the results with the discussion about their implications. The objectives of your discussion section should include the following:

Reiterate the Research Problem/State the Major Findings Briefly reiterate the research problem you are investigating and explain why the subject of analysis around which you designed the case study were used. You should then describe the findings revealed from your study of the case using direct, declarative, and succinct proclamation of the study results. Highlight any findings that were unexpected or especially profound.

Explain the Meaning of the Findings and Why They are Important Systematically explain the meaning of your case study findings and why you believe they are important. Begin this part of the section by repeating what you consider to be your most important or surprising finding first, then systematically review each finding. Be sure to thoroughly extrapolate what your analysis of the case can tell the reader about situations or conditions beyond the actual case that was studied while, at the same time, being careful not to misconstrue or conflate a finding that undermines the external validity of your conclusions.

Relate the Findings to Similar Studies No study in the social sciences is so novel or possesses such a restricted focus that it has absolutely no relation to previously published research. The discussion section should relate your case study results to those found in other studies, particularly if questions raised from prior studies served as the motivation for choosing your subject of analysis. This is important because comparing and contrasting the findings of other studies helps support the overall importance of your results and it highlights how and in what ways your case study design and the subject of analysis differs from prior research about the topic.

Consider Alternative Explanations of the Findings Remember that the purpose of social science research is to discover and not to prove. When writing the discussion section, you should carefully consider all possible explanations revealed by the case study results, rather than just those that fit your hypothesis or prior assumptions and biases. Be alert to what the in-depth analysis of the case may reveal about the research problem, including offering a contrarian perspective to what scholars have stated in prior research if that is how the findings can be interpreted from your case.

Acknowledge the Study's Limitations You can state the study's limitations in the conclusion section of your paper but describing the limitations of your subject of analysis in the discussion section provides an opportunity to identify the limitations and explain why they are not significant. This part of the discussion section should also note any unanswered questions or issues your case study could not address. More detailed information about how to document any limitations to your research can be found here .

Suggest Areas for Further Research Although your case study may offer important insights about the research problem, there are likely additional questions related to the problem that remain unanswered or findings that unexpectedly revealed themselves as a result of your in-depth analysis of the case. Be sure that the recommendations for further research are linked to the research problem and that you explain why your recommendations are valid in other contexts and based on the original assumptions of your study.

V. Conclusion

As with any research paper, you should summarize your conclusion in clear, simple language; emphasize how the findings from your case study differs from or supports prior research and why. Do not simply reiterate the discussion section. Provide a synthesis of key findings presented in the paper to show how these converge to address the research problem. If you haven't already done so in the discussion section, be sure to document the limitations of your case study and any need for further research.

The function of your paper's conclusion is to: 1) reiterate the main argument supported by the findings from your case study; 2) state clearly the context, background, and necessity of pursuing the research problem using a case study design in relation to an issue, controversy, or a gap found from reviewing the literature; and, 3) provide a place to persuasively and succinctly restate the significance of your research problem, given that the reader has now been presented with in-depth information about the topic.

Consider the following points to help ensure your conclusion is appropriate:

- If the argument or purpose of your paper is complex, you may need to summarize these points for your reader.

- If prior to your conclusion, you have not yet explained the significance of your findings or if you are proceeding inductively, use the conclusion of your paper to describe your main points and explain their significance.

- Move from a detailed to a general level of consideration of the case study's findings that returns the topic to the context provided by the introduction or within a new context that emerges from your case study findings.

Note that, depending on the discipline you are writing in or the preferences of your professor, the concluding paragraph may contain your final reflections on the evidence presented as it applies to practice or on the essay's central research problem. However, the nature of being introspective about the subject of analysis you have investigated will depend on whether you are explicitly asked to express your observations in this way.

Problems to Avoid

Overgeneralization One of the goals of a case study is to lay a foundation for understanding broader trends and issues applied to similar circumstances. However, be careful when drawing conclusions from your case study. They must be evidence-based and grounded in the results of the study; otherwise, it is merely speculation. Looking at a prior example, it would be incorrect to state that a factor in improving girls access to education in Azerbaijan and the policy implications this may have for improving access in other Muslim nations is due to girls access to social media if there is no documentary evidence from your case study to indicate this. There may be anecdotal evidence that retention rates were better for girls who were engaged with social media, but this observation would only point to the need for further research and would not be a definitive finding if this was not a part of your original research agenda.

Failure to Document Limitations No case is going to reveal all that needs to be understood about a research problem. Therefore, just as you have to clearly state the limitations of a general research study , you must describe the specific limitations inherent in the subject of analysis. For example, the case of studying how women conceptualize the need for water conservation in a village in Uganda could have limited application in other cultural contexts or in areas where fresh water from rivers or lakes is plentiful and, therefore, conservation is understood more in terms of managing access rather than preserving access to a scarce resource.

Failure to Extrapolate All Possible Implications Just as you don't want to over-generalize from your case study findings, you also have to be thorough in the consideration of all possible outcomes or recommendations derived from your findings. If you do not, your reader may question the validity of your analysis, particularly if you failed to document an obvious outcome from your case study research. For example, in the case of studying the accident at the railroad crossing to evaluate where and what types of warning signals should be located, you failed to take into consideration speed limit signage as well as warning signals. When designing your case study, be sure you have thoroughly addressed all aspects of the problem and do not leave gaps in your analysis that leave the reader questioning the results.

Case Studies. Writing@CSU. Colorado State University; Gerring, John. Case Study Research: Principles and Practices . New York: Cambridge University Press, 2007; Merriam, Sharan B. Qualitative Research and Case Study Applications in Education . Rev. ed. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 1998; Miller, Lisa L. “The Use of Case Studies in Law and Social Science Research.” Annual Review of Law and Social Science 14 (2018): TBD; Mills, Albert J., Gabrielle Durepos, and Eiden Wiebe, editors. Encyclopedia of Case Study Research . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, 2010; Putney, LeAnn Grogan. "Case Study." In Encyclopedia of Research Design , Neil J. Salkind, editor. (Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, 2010), pp. 116-120; Simons, Helen. Case Study Research in Practice . London: SAGE Publications, 2009; Kratochwill, Thomas R. and Joel R. Levin, editors. Single-Case Research Design and Analysis: New Development for Psychology and Education . Hilldsale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1992; Swanborn, Peter G. Case Study Research: What, Why and How? London : SAGE, 2010; Yin, Robert K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods . 6th edition. Los Angeles, CA, SAGE Publications, 2014; Walo, Maree, Adrian Bull, and Helen Breen. “Achieving Economic Benefits at Local Events: A Case Study of a Local Sports Event.” Festival Management and Event Tourism 4 (1996): 95-106.

Writing Tip

At Least Five Misconceptions about Case Study Research

Social science case studies are often perceived as limited in their ability to create new knowledge because they are not randomly selected and findings cannot be generalized to larger populations. Flyvbjerg examines five misunderstandings about case study research and systematically "corrects" each one. To quote, these are:

Misunderstanding 1 : General, theoretical [context-independent] knowledge is more valuable than concrete, practical [context-dependent] knowledge. Misunderstanding 2 : One cannot generalize on the basis of an individual case; therefore, the case study cannot contribute to scientific development. Misunderstanding 3 : The case study is most useful for generating hypotheses; that is, in the first stage of a total research process, whereas other methods are more suitable for hypotheses testing and theory building. Misunderstanding 4 : The case study contains a bias toward verification, that is, a tendency to confirm the researcher’s preconceived notions. Misunderstanding 5 : It is often difficult to summarize and develop general propositions and theories on the basis of specific case studies [p. 221].

While writing your paper, think introspectively about how you addressed these misconceptions because to do so can help you strengthen the validity and reliability of your research by clarifying issues of case selection, the testing and challenging of existing assumptions, the interpretation of key findings, and the summation of case outcomes. Think of a case study research paper as a complete, in-depth narrative about the specific properties and key characteristics of your subject of analysis applied to the research problem.

Flyvbjerg, Bent. “Five Misunderstandings About Case-Study Research.” Qualitative Inquiry 12 (April 2006): 219-245.

- << Previous: Writing a Case Analysis Paper

- Next: Writing a Field Report >>

- Last Updated: May 7, 2024 9:45 AM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide/assignments

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

What Is a Case Study?

Weighing the pros and cons of this method of research

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Cara Lustik is a fact-checker and copywriter.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Cara-Lustik-1000-77abe13cf6c14a34a58c2a0ffb7297da.jpg)

Verywell / Colleen Tighe

- Pros and Cons

What Types of Case Studies Are Out There?

Where do you find data for a case study, how do i write a psychology case study.

A case study is an in-depth study of one person, group, or event. In a case study, nearly every aspect of the subject's life and history is analyzed to seek patterns and causes of behavior. Case studies can be used in many different fields, including psychology, medicine, education, anthropology, political science, and social work.

The point of a case study is to learn as much as possible about an individual or group so that the information can be generalized to many others. Unfortunately, case studies tend to be highly subjective, and it is sometimes difficult to generalize results to a larger population.

While case studies focus on a single individual or group, they follow a format similar to other types of psychology writing. If you are writing a case study, we got you—here are some rules of APA format to reference.

At a Glance