Gender-Based Violence (Violence Against Women and Girls)

Photo: Simone D. McCourtie / World Bank

Gender-based violence (GBV) or violence against women and girls (VAWG), is a global pandemic that affects 1 in 3 women in their lifetime.

The numbers are staggering:

- 35% of women worldwide have experienced either physical and/or sexual intimate partner violence or non-partner sexual violence.

- Globally, 7% of women have been sexually assaulted by someone other than a partner.

- Globally, as many as 38% of murders of women are committed by an intimate partner.

- 200 million women have experienced female genital mutilation/cutting.

This issue is not only devastating for survivors of violence and their families, but also entails significant social and economic costs. In some countries, violence against women is estimated to cost countries up to 3.7% of their GDP – more than double what most governments spend on education.

Failure to address this issue also entails a significant cost for the future. Numerous studies have shown that children growing up with violence are more likely to become survivors themselves or perpetrators of violence in the future.

One characteristic of gender-based violence is that it knows no social or economic boundaries and affects women and girls of all socio-economic backgrounds: this issue needs to be addressed in both developing and developed countries.

Decreasing violence against women and girls requires a community-based, multi-pronged approach, and sustained engagement with multiple stakeholders. The most effective initiatives address underlying risk factors for violence, including social norms regarding gender roles and the acceptability of violence.

The World Bank is committed to addressing gender-based violence through investment, research and learning, and collaboration with stakeholders around the world.

Since 2003, the World Bank has engaged with countries and partners to support projects and knowledge products aimed at preventing and addressing GBV. The Bank supports over $300 million in development projects aimed at addressing GBV in World Bank Group (WBG)-financed operations, both through standalone projects and through the integration of GBV components in sector-specific projects in areas such as transport, education, social protection, and forced displacement. Recognizing the significance of the challenge, addressing GBV in operations has been highlighted as a World Bank priority, with key commitments articulated under both IDA 17 and 18, as well as within the World Bank Group Gender Strategy .

The World Bank conducts analytical work —including rigorous impact evaluation—with partners on gender-based violence to generate lessons on effective prevention and response interventions at the community and national levels.

The World Bank regularly convenes a wide range of development stakeholders to share knowledge and build evidence on what works to address violence against women and girls.

Over the last few years, the World Bank has ramped up its efforts to address more effectively GBV risks in its operations , including learning from other institutions.

Addressing GBV is a significant, long-term development challenge. Recognizing the scale of the challenge, the World Bank’s operational and analytical work has expanded substantially in recent years. The Bank’s engagement is building on global partnerships, learning, and best practices to test and advance effective approaches both to prevent GBV—including interventions to address the social norms and behaviors that underpin violence—and to scale up and improve response when violence occurs.

World Bank-supported initiatives are important steps on a rapidly evolving journey to bring successful interventions to scale, build government and local capacity, and to contribute to the knowledge base of what works and what doesn’t through continuous monitoring and evaluation.

Addressing the complex development challenge of gender-based violence requires significant learning and knowledge sharing through partnerships and long-term programs. The World Bank is committed to working with countries and partners to prevent and address GBV in its projects.

Knowledge sharing and learning

Violence against Women and Girls: Lessons from South Asia is the first report of its kind to gather all available data and information on GBV in the region. In partnership with research institutions and other development organizations, the World Bank has also compiled a comprehensive review of the global evidence for effective interventions to prevent or reduce violence against women and girls. These lessons are now informing our work in several sectors, and are captured in sector-specific resources in the VAWG Resource Guide: www.vawgresourceguide.org .

The World Bank’s Global Platform on Addressing GBV in Fragile and Conflict-Affected Settings facilitated South-South knowledge sharing through workshops and yearly learning tours, building evidence on what works to prevent GBV, and providing quality services to women, men, and child survivors. The Platform included a $13 million cross-regional and cross-practice initiative, establishing pilot projects in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Nepal, Papua New Guinea, and Georgia, focused on GBV prevention and mitigation, as well as knowledge and learning activities.

The World Bank regularly convenes a wide range of development stakeholders to address violence against women and girls. For example, former WBG President Jim Yong Kim committed to an annual Development Marketplace competition, together with the Sexual Violence Research Initiative (SVRI) , to encourage researchers from around the world to build the evidence base of what works to prevent GBV. In April 2019, the World Bank awarded $1.1 million to 11 research teams from nine countries as a result of the fourth annual competition.

Addressing GBV in World Bank Group-financed operations

The World Bank supports both standalone GBV operations, as well as the integration of GBV interventions into development projects across key sectors.

Standalone GBV operations include:

- In August 2018, the World Bank committed $100 million to help prevent GBV in the DRC . The Gender-Based Violence Prevention and Response Project will reach 795,000 direct beneficiaries over the course of four years. The project will provide help to survivors of GBV, and aim to shift social norms by promoting gender equality and behavioral change through strong partnerships with civil society organizations.

- In the Great Lakes Emergency Sexual and Gender Based Violence & Women's Health Project , the World Bank approved $107 million in financial grants to Burundi, the DRC, and Rwanda to provide integrated health and counseling services, legal aid, and economic opportunities to survivors of – or those affected by – sexual and gender-based violence. In DRC alone, 40,000 people, including 29,000 women, have received these services and support.

- The World Bank is also piloting innovative uses of social media to change behaviors . For example, in the South Asia region, the pilot program WEvolve used social media to empower young women and men to challenge and break through prevailing norms that underpin gender violence.

Learning from the Uganda Transport Sector Development Project and following the Global GBV Task Force’s recommendations , the World Bank has developed and launched a rigorous approach to addressing GBV risks in infrastructure operations:

- Guided by the GBV Good Practice Note launched in October 2018, the Bank is applying new standards in GBV risk identification, mitigation and response to all new operations in sustainable development and infrastructure sectors.

- These standards are also being integrated into active operations; GBV risk management approaches are being applied to a selection of operations identified high risk in fiscal year (FY) 2019.

- In the East Asia and Pacific region , GBV prevention and response interventions – including a code of conduct on sexual exploitation and abuse – are embedded within the Vanuatu Aviation Investment Project .

- The Liberia Southeastern Corridor Road Asset Management Project , where sexual exploitation and abuse (SEA) awareness will be raised, among other strategies, as part of a pilot project to employ women in the use of heavy machinery.

- The Bolivia Santa Cruz Road Corridor Project uses a three-pronged approach to address potential GBV, including a Code of Conduct for their workers; a Grievance Redress Mechanism (GRM) that includes a specific mandate to address any kinds gender-based violence; and concrete measures to empower women and to bolster their economic resilience by helping them learn new skills, improve the production and commercialization of traditional arts and crafts, and access more investment opportunities.

- The Mozambique Integrated Feeder Road Development Project identified SEA as a substantial risk during project preparation and takes a preemptive approach: a Code of Conduct; support to – and guidance for – the survivors in case any instances of SEA were to occur within the context of the project – establishing a “survivor-centered approach” that creates multiple entry points for anyone experiencing SEA to seek the help they need; and these measures are taken in close coordination with local community organizations, and an international NGO Jhpiego, which has extensive experience working in Mozambique.

Strengthening institutional efforts to address GBV

In October 2016, the World Bank launched the Global Gender-Based Violence Task Force to strengthen the institution’s efforts to prevent and respond to risks of GBV, and particularly sexual exploitation and abuse (SEA) that may arise in World Bank-supported projects. It builds on existing work by the World Bank and other actors to tackle violence against women and girls through strengthened approaches to identifying and assessing key risks, and developing key mitigations measures to prevent and respond to sexual exploitation and abuse and other forms of GBV.

In line with its commitments under IDA 18 , the World Bank developed an Action Plan for Implementation of the Task Force’s recommendations , consolidating key actions across institutional priorities linked to enhancing social risk management, strengthening operational systems to enhance accountability, and building staff and client capacity to address risks of GBV through training and guidance materials.

As part of implementation of the GBV Task Force recommendations, the World Bank has developed a GBV risk assessment tool and rigorous methodology to assess contextual and project-related risks. The tool is used by any project containing civil works.

The World Bank has developed a Good Practice Note (GPN) with recommendations to assist staff in identifying risks of GBV, particularly sexual exploitation and abuse and sexual harassment that can emerge in investment projects with major civil works contracts. Building on World Bank experience and good international industry practices, the note also advises staff on how to best manage such risks. A similar toolkit and resource note for Borrowers is under development, and the Bank is in the process of adapting the GPN for key sectors in human development.

The GPN provides good practice for staff on addressing GBV risks and impacts in the context of the Environmental and Social Framework (ESF) launched on October 1, 2018, including the following ESF standards, as well as the safeguards policies that pre-date the ESF:

- ESS 1: Assessment and Management of Environmental and Social Risks and Impacts;

- ESS 2: Labor and Working Conditions;

- ESS 4: Community Health and Safety; and

- ESS 10: Stakeholder Engagement and Information Disclosure.

In addition to the Good Practice Note and GBV Risk Assessment Screening Tool, which enable improved GBV risk identification and management, the Bank has made important changes in its operational processes, including the integration of SEA/GBV provisions into its safeguard and procurement requirements as part of evolving Environmental, Social, Health and Safety (ESHS) standards, elaboration of GBV reporting and response measures in the Environmental and Social Incident Reporting Tool, and development of guidance on addressing GBV cases in our grievance redress mechanisms.

In line with recommendations by the Task Force to disseminate lessons learned from past projects, and to sensitize staff on the importance of addressing risks of GBV and SEA, the World Bank has developed of trainings for Bank staff to raise awareness of GBV risks and to familiarize staff with new GBV measures and requirements. These trainings are further complemented by ongoing learning events and intensive sessions of GBV risk management.

Last Updated: Sep 25, 2019

- FEATURE STORY To End Poverty You Have to Eliminate Violence Against Women and Girls

- TOOLKIT Violence Against Women and Girls (VAWG) Resource Guide

DRC, Nepal, Papua New Guinea, and Rwanda Join Forces to Fight Sexual and Gender-...

More than one in three women worldwide have experienced sexual and gender-based violence during their lifetime. In contexts of fragility and conflict, sexual violence is often exacerbated.

Supporting Women Survivors of Violence in Africa's Great Lakes Region

The Great Lakes Emergency SGBV and Women’s Health Project is the first World Bank project in Africa with a major focus on offering integrated services to survivors of sexual and gender-based violence.

To End Poverty, Eliminate Gender-Based Violence

Intimate partner violence and non-partner sexual violence are economic consequences that contribute to ongoing poverty. Ede Ijjasz-Vasquez, Senior Director at the World Bank, explains the role that social norms play in ...

This site uses cookies to optimize functionality and give you the best possible experience. If you continue to navigate this website beyond this page, cookies will be placed on your browser. To learn more about cookies, click here .

- Open access

- Published: 08 March 2019

Social norms and beliefs about gender based violence scale: a measure for use with gender based violence prevention programs in low-resource and humanitarian settings

- Nancy Perrin 1 ,

- Mendy Marsh 2 ,

- Amber Clough 1 ,

- Amelie Desgroppes 3 ,

- Clement Yope Phanuel 4 ,

- Ali Abdi 3 ,

- Francesco Kaburu 3 ,

- Silje Heitmann 5 ,

- Masumi Yamashina 6 ,

- Brendan Ross 7 ,

- Sophie Read-Hamilton 8 ,

- Rachael Turner 1 ,

- Lori Heise 1 , 9 &

- Nancy Glass 1

Conflict and Health volume 13 , Article number: 6 ( 2019 ) Cite this article

168k Accesses

63 Citations

43 Altmetric

Metrics details

Gender-based violence (GBV) primary prevention programs seek to facilitate change by addressing the underlying causes and drivers of violence against women and girls at a population level. Social norms are contextually and socially derived collective expectations of appropriate behaviors. Harmful social norms that sustain GBV include women’s sexual purity, protecting family honor over women’s safety, and men’s authority to discipline women and children. To evaluate the impact of GBV prevention programs, our team sought to develop a brief, valid, and reliable measure to examine change over time in harmful social norms and personal beliefs that maintain and tolerate sexual violence and other forms of GBV against women and girls in low resource and complex humanitarian settings.

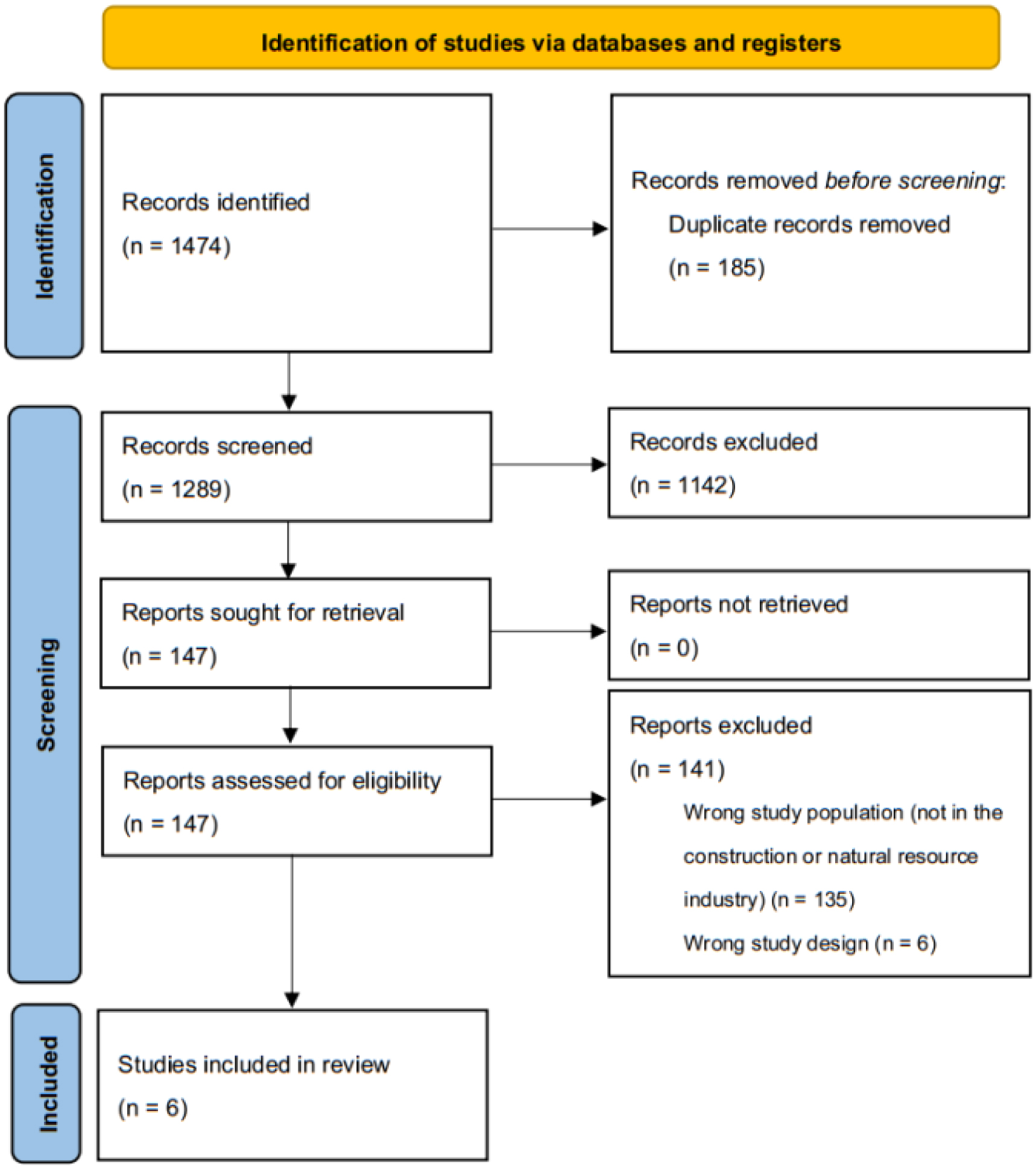

The development and testing of the scale was conducted in two phases: 1) formative phase of qualitative inquiry to identify social norms and personal beliefs that sustain and justify GBV perpetration against women and girls; and 2) testing phase using quantitative methods to conduct a psychometric evaluation of the new scale in targeted areas of Somalia and South Sudan.

The Social Norms and Beliefs about GBV Scale was administered to 602 randomly selected men ( N = 301) and women (N = 301) community members age 15 years and older across Mogadishu, Somalia and Yei and Warrup, South Sudan. The psychometric properties of the 30-item scale are strong. Each of the three subscales, “Response to Sexual Violence,” “Protecting Family Honor,” and “Husband’s Right to Use Violence” within the two domains, personal beliefs and injunctive social norms, illustrate good factor structure, acceptable internal consistency, reliability, and are supported by the significance of the hypothesized group differences.

Conclusions

We encourage and recommend that researchers and practitioners apply the Social Norms and Beliefs about GBV Scale in different humanitarian and global LMIC settings and collect parallel data on a range of GBV outcomes. This will allow us to further validate the scale by triangulating its findings with GBV experiences and perpetration and assess its generalizability across diverse settings.

Introduction

Gender-based violence (GBV) remains one of the most prevalent and persistent issues facing women and girls globally [ 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 ]. Conflict and other humanitarian emergencies place women and girls at increased risk of many forms of GBV [ 5 , 6 , 7 ]. The Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC) 2015 Guidelines for Integrating GBV Interventions in Humanitarian Action defines GBV as any harmful act that is perpetrated against a person’s will and that is based on socially ascribed (i.e., gender) differences between females and males. It includes acts that inflict physical, sexual or mental harm or suffering, threats of such acts, coercion, and other deprivations of liberty. These harmful acts can occur in public and in private [ 8 ]. There continues to be limited global information on the burden of GBV in humanitarian emergencies. One systematic review found that approximately one in five refugees or displaced women in complex humanitarian settings experienced sexual violence, though this is likely an underestimation of the true prevalence given the many barriers to survivors’ disclosure of GBV [ 9 ]. A recent population-based survey on GBV across the three regions of Somalia examined typology and scope of GBV victimization with 2376 women (15 years and older). The study found that among women, 35.6% (95% CI 33.4 to 37.9) reported lifetime experiences of physical or sexual intimate partner violence (IPV) and 16.5% (95% CI 15.1 to 18.1) reported lifetime experience of physical or sexual non-partner violence (NPV) since the age of 15 years. Women at greatest risk of GBV (IPV and NPV) included membership in a minority clan, displacement from home because of conflict or natural disaster, husband/partner use of khat (e.g., leaves chewed or drunk as a stimulant), exposure to parental violence and violence during childhood. Women survivors of GBV consistently report negative impacts on physical, mental and reproductive health. Often negative health and social consequences are never addressed because women do not disclose GBV to providers or access health care or other services (e.g., protection, legal, traditional authorities) because of social norms that blame the woman for the assault (e.g., she was out alone after dark, she was not modestly dressed, she is working outside the home), norms that prioritize protecting family honor over safety of the survivor, and institutional acceptance of GBV as a normal and expected part of displacement and conflict [ 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 ].

GBV primary prevention in humanitarian settings

GBV primary prevention programs seek to facilitate change by addressing the underlying causes and drivers of GBV at a population level. Such programs have traditionally included initiatives to economically empower girls and women, enhanced legal protections for GBV, enshrining women’s rights and gender equality within national legislation and policy, and other measures to promote gender equality. Increasingly, programs are also targeting transformation of social norms that justify and sustain acceptance of GBV. Social norms are contextually and socially derived collective expectations of appropriate behaviors [ 14 ]. Families and communities have shared beliefs and unspoken rules that both proscribe and prescribe behaviors that implicitly convey that GBV against women is acceptable, even normal [ 15 , 16 ]. This includes social norms pertaining to sexual purity, family honor, and men’s authority over women and children in the family. Community leaders, institutions, and service providers, such as health care, education and law enforcement, can reinforce harmful social norms by, for example, blaming women and girls for the sexual assault they experience, or by justifying a husband’s use of physical violence as a means to discipline his wife. Both behaviors are viewed as essential to protect the family’s reputation in the larger community [ 16 ].

Diverse academic disciplines have developed different theories to explain the complexity of social norms and their influence on behavior. We use social norms theory as elaborated in social psychology [ 17 ]. This theory conceptualizes social norms as beliefs of two types: 1) an individual’s beliefs about what others typically do in a given situation (i.e., descriptive norm); and 2) their beliefs about what others expect them to do in a given situation (i.e., injunctive norm) [ 18 , 19 , 20 ]. For this study, we focus on developing a measure of injunctive norms—defined in this case as beliefs about what influential others (e.g., parents, siblings, peers, religious leaders, teachers) expect individuals to do in the case of GBV.

Even with the multiple challenges of humanitarian settings (e.g., separation of families, insecurity and limited resources), there is an opportunity to develop, implement, and evaluate innovations in GBV programming. In such settings, displacement and conflict have created situations where social rules about who can do what necessarily bend to accommodate new realities [ 16 ]. Women, for example, may be forced to assume new roles in the family and community, such as having decision-making power and control over household financial resources and assets and working outside the home to help support the family. These changing roles then lead to shifts in behavior and potentially power relations in the family and community that challenge traditional norms around male authority and women’s relegation to the domestic sphere. These circumstances can provide an opportunity to initiate GBV primary prevention efforts, such as those that engage community leaders and members in critical reflection on norms that legitimate gender inequality and what actions can be taken by the individual, family, and community to change norms that cause harm [ 15 , 16 ]. Acknowledging the potential of the humanitarian setting as an opportunity for primary prevention programming and recognizing the need to strengthen GBV response systems, the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) built on their work to end female genital mutilation using social norms theory [ 19 ] to develop the Communities Care Program: Transforming Lives and Preventing Violence Program (Communities Care) [ 21 ]. The goal of Communities Care is to create safer communities for women and girls by challenging social norms that sustain GBV and catalyzing new norms that uphold women and girls’ equality, safety, and dignity [ 15 , 21 ]. The description of the Communities Care program is published elsewhere [ 15 , 16 , 21 ].

However, a significant limitation for evaluating the effectiveness of GBV prevention programs such as Communities Care is the lack of validated instruments to measure change in norms supporting GBV. Therefore, our goal was to create a brief, valid, and reliable measure to examine change over time in harmful social norms and personal beliefs that maintain and tolerate sexual violence and other forms of GBV in low resource and complex humanitarian settings.

While validated instruments exist to measure attitudes towards gender roles and some types of GBV [ 22 , 23 ], social norms are different from individual attitudes. For nearly two decades, the Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS), which are nationally representative surveys conducted in low and middle-income countries (LMIC), have provided information on attitudes about the acceptability of IPV or wife beating. Respondents are asked whether a man is justified in beating his wife in five different situations: a wife goes out without her husband’s permission; she neglects to keep the children well fed; she argues with her husband in public; she refuses to have sexual intercourse with her husband; and she does not prepare her husband’s meal on time. Response options for these questions are as follows: “agree,” “disagree,” “refuse to answer,” and “don’t know.” These questions are designed specifically to elicit personal beliefs (attitudes) about IPV; they have generally functioned well in that they capture various levels of endorsement of IPV both within and among settings, and respondents routinely vary their answers based on the transgression mentioned.

Investigators, however, have raised questions about whether the DHS questions reflect respondents’ own personal beliefs on the acceptability of beating or women’s perception of the social norm operative in their setting. Cognitive interviews with women in Bangladesh, for example, suggested that women’s interpretation of the attitude questions switched between personal and normative beliefs, although it is difficult to know whether this happens routinely in other settings, or whether it was a function of the especially low literacy and female mobility of rural Bangladesh [ 24 , 25 ].

Scientists have also warned that changing key features of a scenario (e.g., setting, perpetrator, infraction committed, perceived intentionality) can influence measured attitudes and perceived norms on the acceptability of GBV. For example, in Uganda, researchers randomly assigned participants to answer attitude and norm questions on wife beating using three separate wordings [ 26 ]. The attitude questions compared the traditional wording of the DHS (whether a man is justified in beating his wife for 5 different infractions) to more contextualized scenarios that depicted the wife’s transgression as either willful or beyond her control. To elicit norms related to wife beating, participants were asked about the extent to which they thought other people in their village (reference group) would think the behavior described was justified. Response options for the five questions followed a four-point Likert-type scale: “all or almost all, for example, at least 90% of people in your village,” “more than half but fewer than 90% of people in your village,” “fewer than half but more than 10% of people in your village,” and “very few or none, for example, less than 10% of people in your village.”

The findings demonstrated that when measuring both attitudes and social norms, adding contextual details about the intentionality of a wife’s transgression changed participants’ perception of the acceptability of IPV. In the vignettes, wives who intentionally violated norms about acceptable wifely behavior had a “large” effect [ 27 ] on increasing the number of items for which wife beating was viewed as acceptable. In contrast, the vignette that depicted the wife as unintentionally violating norms of behavior had a “small” effect in decreasing the number of items where IPV was considered acceptable. The study authors interpreted this difference as measurement error, arguing that question wordings without context may mis-represent attitudes and norms on violence. While context does matter, the specific details added in this study were likely critical to its findings. Qualitative studies have repeatedly shown that wife beating in LMIC is understood as “discipline” and its acceptability varies depending on the nature of the transgression (whether it is perceived as for “just cause”), who is doing the “correction,” and whether the beating stays within acceptable bounds of severity [ 24 , 25 , 28 , 29 , 30 ].

In this paper, we describe the formative research and psychometric testing of the Social Norms and Beliefs about Gender Based Violence (GBV) Scale . The Scale is designed to measure change over time in harmful social norms and personal beliefs associated with violence against women and girls among men and women community members in low resource and complex humanitarian settings. The development and validation of the scale was essential for use in measuring change in harmful social norms and beliefs among community members in districts and regions implementing the Communities Care program in two countries with ongoing humanitarian crises, Somalia and South Sudan. The development and testing of the scale was conducted in two phases: 1) formative phase of qualitative inquiry to identify social norms and personal beliefs that sustain and justify GBV perpetration against women and girls across the lifespan in low-resource and humanitarian contexts; and 2) testing phase using quantitative methods to conduct a psychometric evaluation of the new scale in targeted areas of Somalia and South Sudan.

Study settings

The formative and testing phases of the psychometric evaluation was conducted in two countries, Somalia and South Sudan. In Southern Central Somalia, we worked in four districts (Bondhere, Karaan, Wadajir, Yaqshid ) in Mogadishu and in South Sudan, we worked in two regions (Yei and Warrap). Somalia has experienced more than two decades of conflict as well as ongoing emergencies including drought, famine, and a large number of internally displaced people (IDPs). Yei is located in southwestern South Sudan and was the re-entry point for South Sudanese who fled to the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) and Uganda during the Second Sudanese Civil War. Since many people stayed in Yei upon returning, there is conflict between those native to Yei and IDPs from other regions of South Sudan. Warrap is in the northern region of South Sudan and is a gateway between South Sudan and Sudan. Militia activity, cattle-raiding, and conflict over oil, along with the influx of people returning to South Sudan, has caused significant challenges for access to and use of limited resources. The districts and regions in each country were selected based on multiple factors. We focused efforts on districts and regions where GBV reporting systems existed and could be accessed to generate data on case reports and referrals. When engaging GBV survivors and other community members in research on sensitive issues it is essential to have partnerships with diverse service sectors (e.g., health, protection, legal, advocacy) for participants that disclose GBV and request referrals. The evaluation also required safe access to the sites and security while doing the study for both participants and local researchers, therefore this required establishing relationships and obtaining permission from national, regional, and district governmental authorities and ministries as well as traditional leaders in the communities.

Phase 1: Formative phase methods

For the formative phase, we worked with local partners to identify male and female key stakeholders (e.g., religious leaders, youth and women’s group leaders, advocates for GBV survivors, health providers, child protection staff, police officers, traditional leaders, elders, and teachers) to advance our understanding of and identify harmful and protective social norms associated with GBV within and across settings. The focus group guide was developed and translated to the local language in partnership with team members in each setting. Johns Hopkins provided in-depth training to local staff on facilitating focus groups, data collection, human subjects’ protections, working with distressed participants, and providing referrals to services as appropriate. The focus group guide focused on identification of social norms that protect women and girls from sexual violence and other forms of GBV, norms that are harmful (e.g., hide, sustain, or encourage), norms about disclosing and reporting sexual violence and other forms of GBV to authorities, and who are the people in the family or larger community that are influential in maintaining and changing social norms. For example, the team used scenarios created from aggregating GBV experiences in each setting to explore social norms about the situations and the survivor-perpetrator relationship. We varied the perpetrator and circumstances in each scenario from the perpetrator being a family member, a known person to the family but not part of the family, and an unknown person. For each scenario, focus group participants were asked about their beliefs and norms about how the family and community would respond to victims of the sexual assault or other forms of GBV, if the assault would be reported to authorities, and reasons for reporting or not reporting the assault.

Qualitative analysis

A qualitative descriptive approach was used to identify themes related to harmful and protective social norms within and across settings. The transcripts were read by three research team members to identify thematic codes. Themes with sub-themes were identified and defined by exemplars or quotes from the transcripts. The three researchers independently assigned codes and discrepancies in coding were discussed in weekly meetings. The codes and corresponding quotes were used to write items for the scale representing each of the identified themes. The themes, sub-themes, and items were then shared with the in-country teams in a joint Somalia/South Sudan meeting. The relevance of the themes and their interpretation for each context was discussed leading to a refinement of the items. Meeting participants from each country rated the importance of each item and offered suggestions on wording of the items to ensure they were capturing the relevant aspects of the different contexts and cultures.

Results of phase 1: Formative phase

A total of 42 focus groups (22 in Somalia and 20 in South Sudan) with a total of 215 participants (111 in Somalia and 104 in South Sudan) were conducted. The composition of the focus groups varied by stakeholders (e.g., religious leaders, service providers, teachers, police, youth, elders), age (under 30, 31–45, and 46+), marital status, and sex. Themes identified for social norms that are protective against GBV included parents teaching/guiding children, marriage, and respect for female members of the family. Themes identified as harmful social norms included men’s responsibility/right to correct female behavior and the social expectation that a woman will obey her husband and fulfill her gender prescribed duties to his satisfaction, protecting the family’s dignity by not reporting violence/assault to avoid stigma associated with being a victim, husband’s right to force his wife to have sex, lack of status for women, and forced marriage. Mothers, fathers, parents, community and religious leaders, and male relatives were seen as people that influenced behavior and protected women and girls from GBV. Men and women’s behavior also emerged as subthemes associated with harmful social norms, such as indecent dressing, being out in public alone, and drug/alcohol use. Stigma associated with being a GBV victim, blaming women and girls for the violence/assault, and the importance of family honor and respect were identified as norms that prevent victims and families from reporting sexual violence and other forms of GBV to authorities. Items for the new scale were written for each of the themes and sub-themes relevant to harmful social norms and after elimination of redundant items, 30 items remained and were presented to the in-country teams. After discussion about the focus group themes and the items with the in-country teams, a total of 18 items remained. The team then collaborated to develop introductory statements and response scales for each of two domains of the scale, personal beliefs and injunctive social norms. The final scale to be tested in the evaluation phase had two sets of the 18 items, one for each domain.

Methods for phase 2: Psychometric testing

At each of the three sites in the two countries detailed above, trained local research assistants (RAs) recruited and consented 200 community members (15 years and older) to complete the Social Norms and Beliefs about Gender Based Violence Scale. The sampling frame was stratified by age group (15–18, 19–24, 25–45, 46+ years) and sex with a target of 25 people per age group/sex combination. As suggested by the in-country teams, male RAs recruited and interviewed male community members and female RAs recruited and interviewed female community members. Each RA recruited participants across age groups. The RA started from a central point determined by the research coordinator each morning. The RA would contact every 3rd house/dwelling counting on both sides of the street/pathway. If nobody was home, the person was not willing to participate, or the person did not match the sampling target for sex/age, the RA went to the next house/dwelling. Once a RA identified and consented an eligible participant in the household and completed the scale, the RA started the process to identify the next eligible participant by going to the next 3rd house/dwelling on the street/pathway. Only one eligible household member completed the scale.

Field procedures

RAs received detailed training on protocols for maintaining participant confidentiality and safety as well as protocols designed to ensure safety and security for the team members. In the field, when a RA identified an adult at a house/dwelling, he/she introduced the study. If that person met the eligibility criteria and agreed to participate, the RA worked with the participant to find a private and comfortable place to provide informed consent and administer the scale. If that person did not meet eligibility, he/she was asked if there was someone living in the household that did meet the eligibility. The RA provided each potential participant with informed consent information using the script provided on the study tablet and approved by the in-country team and the Johns Hopkins Medical Institution Institutional Review Board (IRB). If the eligible participant provided verbal consent the RA continued and administered the scale with brief demographic questions, including marital status, employment, and children in the household. The responses were entered by the RA directly on the tablet. Once finished, the RA thanked the participant for their time and answered any questions prior to moving on.

The 18 items generated from the formative phase were asked in two sets to capture the two domains, personal beliefs and injunctive norms. The injunctive social norms items started with “How many of the people whose opinion matters most to you….” with the response scale of: 1 – None of them, 2 – A few of them, 3 – About half of them, 4 – Most of them, and 5 – All of them. The personal beliefs items started with “We would like to know if you think any of the following statements are wrong and should be changed in your community. We also would like to understand how ready or willing you are to take action by speaking out on the issues you think are wrong” and used the response scale: 1 – Agree with this statement, 2 – I am not sure if I agree or disagree with this statement, 3 – I disagree with the statement but am not ready to tell others, and 4 – I disagree with the statement and I am telling others that this is wrong. The scale was translated into Somali and the translation was reviewed by the Somalia team and revised before it was programmed into the study tablet. In South Sudan, the scale was administered in the Kakwa language in Yei and Dinka language in Warrap. As these are not commonly written languages in South Sudan, the team preferred using the English version of the scale programmed on the tablet and translated into the local language at time of administration. The South Sudan team training included discussions and decisions on correct translation of items in the two languages and then the team practiced administering with volunteers not participating in the study to ensure consistency in real-time translation across RAs and sites.

Psychometric analyses

For each of the two domains of the scale, we examined construct validity with factor analysis using the common factor model with oblique rotation. Factor loadings of .40 or above were considered as loading on a given factor [ 31 ]. Items that did not load on any factor were considered for revision or elimination from the scale. Reliability was estimated with Cronbach’s alpha for each factor subscale. Known groups validity was examined by testing two a priori hypotheses: H 1 : The sites (Somalia, Yei, South Sudan, and Warrup, South Sudan) differ on social norms and personal beliefs due to differences in the extent of GBV programming within the districts of Mogadishu and regions of South Sudan; and H 2 : Men and women participants will differ on social norms and personal beliefs related to GBV. The first hypothesis was tested with analysis of variance and the second with t-tests.

Results of psychometric testing

The team administered the Social Norms and Beliefs about GBV Scale to 602 community members across Mogadishu, Somalia and Yei and Warrup, South Sudan. The sampling frame was successfully implemented by the research team with 50.0% of participants across the settings being female and 50.0% male with an equal distribution across age groups except in Yei, South Sudan. The team in Yei reported having difficulty finding community members in the region over 60 years of age. The lack of older community members could be related to deaths in the Second Civil War from 1983 to 2005. Over half (58.6%) of the participants were married and had children in the home (67.4%). One third (34%) reported working outside the home, 10.1% were looking for work, 21.4% were students, 29.4% were housewives, and 4.7% were too old to work. Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of the participants by country and site.

Factor analysis

The factor analysis for the items in the injunctive norms domain of the scale was based on responses from participants that completed all items ( N = 587, 97.5%). There were 3 of the 18 items on the injunctive social norms scales that did not load on any factor and were thus removed from the scale. The first item “expect daughters to be married before 15 years of age” likely did not correlate with the other items on the scale because early marriage is seen as a different concept than sexual violence. The second item “think that if an unmarried woman/girl is raped by a man, she should marry him rather than not being married at all” captures two different concepts—marrying the man who raped her and that being better than not being married at all. This complexity likely made the question difficult to answer. The third item “expect a woman not to report her husband for forcing her to have sexual intercourse” did not reflect a consistent social norm. Discussions with the in-country teams revealed that there was considerable debate on this item even among people who agreed on other items. Based on the eigenvalues (first 5 eigenvalues were 4.27, 1.82, 1.23, 0.94, 0.81), the remaining 15 items formed three factors (Table 2 presents the factor loadings for each item on each of the three factors) with each item loading above 0.40 on only one factor. The following titles were given to represent the three factors, later describes as subscales: “Response to Sexual Violence” has 5 items, “Protecting Family Honor” has 6 items, and “Husband’s Right to Use Violence” has 4 items. The “Response to Sexual Violence” and “Husbands’ Right to Use Violence” subscales had the highest inter-factor correlation (0.46) followed by “Response to Sexual Violence” and “Protecting Family Honor” (0.34), then “Protecting Family Honor” and “Husbands’ Right to Use Violence” (0.30). Importantly, these 3 factors were consistent with and reflected the themes identified from the qualitative analyses of the focus groups in Phase 1. A very similar factor structure was found for the personal beliefs domain ( N = 588, 97.7%). Eigenvalues (first 5 eigenvalues were 4.46, 1.76, 1.46, 0.90, 0.88) suggested 3 factors as illustrated in Table 3 . All items loaded at 0.45 or greater on only one of the three factors. One item, “a woman/girl would be stigmatized if she were to report rape” loaded on the “Response to Sexual Violence” in the personal beliefs domain whereas the corresponding item, “women/girls fear stigma if they were to report sexual violence”, loaded on the “Protecting Family Honor” subscale for the social norms domain. The inter-factor correlations on the personal beliefs domain were also very similar to the injunctive social norms domain scale: “Response to Sexual Violence” and “Husbands’ Right to Use Violence” had the highest correlation (0.43) followed by “Response to Sexual Violence” and “Protecting Family Honor” (0.32), then “Protecting Family Honor” and “Husbands’ Right to Use Violence” (0.26).

Reliability

Cronbach alpha reliabilities, a measure of internal consistency of the scale, were in an acceptable range for all factors/subscales within each domain. Cronbach alphas ranged from 0.69 to 0.75 for the injunctive norms domain and 0.71 to 0.77 for the personal beliefs domain (the last row of Tables 2 and 3 present the Cronbach alphas for each scale).

Descriptive statistics

Scores for each of the factors (subscales) were computed by taking the average of the items within the subscales. The injunctive social norms domain subscales scores range from 1 to 5 with higher scores reflecting more negative responses to sexual violence and GBV, stronger support for social norms that prioritize protecting family honor by not reporting sexual violence or other forms of GBV, and stronger support for norms endorsing a husband’s right to use violence. Personal beliefs subscales can range from 1 to 4 with higher scores reflecting a more positive response to survivors of sexual violence, that protecting family honor and not reporting sexual violence is wrong, and that a husband should not have the right to use violence against his wife. The means, standard deviations, minimum, and maximum observed score for each of the subscales in each domain are presented in Table 4 . In general, the mean for the injunctive social norms subscales reflect participants’ views that “few to about half” of the people who are important/influential to them endorse harmful social norms about GBV with “Protecting Family Honor” being the strongest norm (means range from 2.00 to 2.77). The mean for the personal beliefs subscales reflects that participant beliefs range between “not being sure if they disagree” with the norms to “disagreeing but not being ready to speak out against them.” Specifically, participants’ beliefs ranged between not being sure if they disagree to disagreeing but not ready to speak out against protecting family honor (mean = 2.61) and husband’s right to use violence (mean = 2.90). Participants indicated that they were between disagreeing but not being ready to tell others to telling others that negative responses to sexual violence survivors are wrong (mean = 3.29). Cross domain correlations were − .318 (p < .001) for “Response to Sexual Violence”, −.512 (p < .001) for “Protecting Family Honor”, and − .427 (p < .001) for “Husband’s Right to Use Violence.”

Known groups validity

Analysis of variance with Bonferroni post-hoc tests revealed that the three sites differed significantly on all subscales for the injunctive social norms domain (i.e., “Response to Sexual Violence,” p < .001; “Protecting Family Honor,” p = .039; “Husband’s Right to Use Violence,” p < .001). Women and men participants in Yei, South Sudan, where there are few GBV programs and services, reported social norms that are significantly more accepting of sexual violence and other forms of GBV than Warrap, South Sudan and Mogadishu, Somalia. In terms of personal beliefs, women and men in Yei were also significantly less likely to speak out against harmful responses to sexual violence and other GBV (p < .001). In Mogadishu, Somalia, men and women were significantly less likely to speak out against “Protecting Family Honor” (p < .001) and “Husband’s Right to Use Violence” (p < .001) than the sites in South Sudan. Table 5 summarizes the t-test results examining differences in the subscales for both domains between men and women. Women participants had significantly higher scores on all of the subscales for the injunctive social norms, indicating women were more likely to endorse harmful norms related to “Response to Sexual Violence”, “Protecting Family Honor”, and “Husband’s Right to Use Violence” than men. Men and women did not differ on personal beliefs about “Response to Sexual Violence”, however, men reported that they are more ready to speak out against harmful social norms of “Protecting Family Honor” and “Husband’s Right to Use Violence” than women.

The psychometric properties of the Social Norms and Beliefs about GBV Scale (final scale is presented in Additional file 1 ) are strong. Each of the three subscales, “Response to Sexual Violence,” “Protecting Family Honor,” and “Husband’s Right to Use Violence” within the two domains of the scale illustrate good factor structure, acceptable internal consistency, reliability, and are supported by the significance of the hypothesized group differences. These three factors represent social norms that are known from previous research to maintain the high rates of GBV in many global settings [ 28 ]. The “Response to Sexual Violence” subscale captures the individual, family, and community response of blaming the victim for GBV. Most often a woman or girl is blamed for the sexual assault or other form of GBV and the family and larger community can respond with rejection and judgement of her behavior, which can result in the family not supporting or abandoning the victim. It reflects the acceptance of sexual violence and other forms of GBV as expected or even normal and that women and girls need to limit their movement and actions to prevent men from assaulting them, as men are not able to control their behavior if they are “tempted” by women. High scores on the injunctive norms domain of this subscale represent that the respondents believe that their influential others expect people to endorse victim blaming responses to sexual violence and other forms of GBV. The “Protecting Family Honor” subscale identifies the stigma associated with being a member of a family/clan where a women/girl experiences GBV and the importance placed on addressing the violence within the family/clan rather than reporting it to authorities. The priority is to protect the family and victim’s reputations rather than the safety and well-being of the woman or girl. High scores on the injunctive domain of this subscale represent that the respondent believes their influential other expects people to prioritize protecting family honor over safety and well-being of victims. The “Husband’s Right to Use Violence” subscale reflects social norms that support a husband’s use of violence to discipline his wife and to have sex with her even when she does not want to. It also reflects a norm that associates a man’s use of violence against his wife with illustrating his love for her. High scores on the injunctive norms domain for this subscale indicates that the respondents believe their influential others expect people to endorse a husband’s right to use violence against his wife. High scores on the personal beliefs domains for each of the subscales reflect a greater willingness to speak out against social norms that endorse GBV.

Validity of the injunctive norms subscales was supported by significant relationships with other variables (i.e., site and sex) as hypothesized during the development of the scale. The three sites were significantly different on the injunctive norms domain of the scale. Although all three sites experienced a high degree of conflict, the amount of humanitarian services to support GBV survivors and programming to raise awareness and change harmful social norms towards GBV varied. Mogadishu districts participating in the study had relatively active programming, with Warrap and Yei reporting few international and local NGOs with capacity to provide diverse GBV services and programs. Yei, South Sudan was found to have significantly stronger norms that endorse negative “Response to Sexual Violence” and other forms of GBV than other sites. The beliefs of participants from Yei also indicated less support for changing harmful social norms about GBV than other sites in the study. Participants in the four districts of Mogadishu scored the lowest on the personal beliefs subscales of “Husband’s Right to Use Violence” and “Protecting Family Honor.” This finding indicates that participants were less willing to speak out against social norms that support husbands’ rights to use violence against their wives or norms that support not reporting sexual violence to protect family honor than the South Sudan sites. Important to interpreting the findings are the differences in context, culture, and religion across the sites which inform social norms and personal beliefs.

Generalizability is one of the indicators of trustworthiness of the Social Norms and Beliefs about GBV scale – the ability to interpret and apply the scale in a broader context to make it relevant and meaningful to GBV prevention programs being implemented and evaluated in diverse low-resource and humanitarian settings. Importantly, the 36-item two domain scaled applied with community members by local teams in diverse districts and regions within Somalia and South Sudan resulted in a valid and reliable 30-item scale to measure personal beliefs and injunctive social norms. The psychometric phase included randomly selected women and men across multiple age groups (15 years and older), living in both urban and rural communities, and included community members living in settlements and camps for displaced persons. Thus, the scale has the potential to be used in not only humanitarian settings, but also GBV prevention programs in other low-resource and fragile settings.

Although this psychometric evaluation has several strengths, including a mixed methods design to develop the scale and a large sample size to test the scale across diverse sites, it has limitations. The study does not include a separate validation sample to conduct a confirmatory factor analysis. Further, we did not test the relationship between the Social Norms and Beliefs about GBV Scale and community members’ reports on experience, perpetration, or witnessing of GBV in the participating communities. The research team decided in collaboration with local partners not to ask participants in the evaluation phase about personal experiences with GBV for either the scale development or testing. The local colleagues felt community members would be more comfortable and likely to participate in the scale development and testing if they were not asked about their own experiences and thus also increasing generalizability.

The study presents a mixed methods approach to developing a brief scale with strong psychometric properties to measure change in harmful social norms associated with GBV. The Social Norms and Beliefs About GBV Scale is a 30-item scale with three subscales, “Response to Sexual Violence,” “Protecting Family Honor,” and “Husband’s Right to Use Violence” in each of the two domains, personal beliefs and injunctive social norms. The scale to our knowledge is one of the first to demonstrate good factor structure, acceptable internal consistency, and reliability, and be supported by the significance of the hypothesized group differences by setting and sex. We encourage and recommend that researchers apply the Social Norms and Beliefs about GBV Scale in different humanitarian and global LMIC settings and collect parallel data on a range of GBV outcomes. This will allow us to further validate the scale by triangulating its findings with GBV experiences and perpetration and assess its generalizability across diverse settings.

Abbreviations

Demographic and Health Surveys

Democratic Republic of Congo

- Gender-based violence

Inter-Agency Standing Committee

Internally displaced persons

Intimate partner violence

Institutional Review Board

Low and middle-income countries

Non-partner violence

Research assistant

United Nations Children’s Fund

Decker MR, Latimore AD, Yasutake S, Haviland M, Ahmed S, Blum RW, et al. Gender-based violence against adolescent and young adult women in low- and middle-income countries. J Adolesc Health. 2015;56(2):188–96.

Article Google Scholar

Devries KM, Mak JY, Garcia-Moreno C, Petzold M, Child JC, Falder G, et al. Global health. The global prevalence of intimate partner violence against women. Science. 2013;340(6140):1527–8.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Watts C, Zimmerman C. Violence against women: global scope and magnitude. Lancet. 2002;359(9313):1232–7.

Garcia-Moreno C, Jansen HA, Ellsberg M, Heise L, Watts CH, WHOM-cSoWs H, et al. Prevalence of intimate partner violence: findings from the WHO multi-country study on women's health and domestic violence. Lancet. 2006;368(9543):1260–9.

Vu A, Adam A, Wirtz A, Pham K, Rubenstein L, Glass N, et al. The prevalence of sexual violence among female refugees in complex humanitarian emergencies: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Curr. 2014;6.

Wirtz AL, Pham K, Glass N, Loochkartt S, Kidane T, Cuspoca D, et al. Gender-based violence in conflict and displacement: qualitative findings from displaced women in Colombia. Confl Health. 2014;8:10.

Sloand E, Killion C, Gary FA, Dennis B, Glass N, Hassan M, et al. Barriers and facilitators to engaging communities in gender-based violence prevention following a natural disaster. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2015;26(4):1377–90.

IASC. Guidelines for Integrating Gender-based Violence Interventions in Humanitarian Action. Reducing risk. In: Promoting resilience and aiding recovery Geneva: inter-agency standing committee; 2015.

Google Scholar

Vu A, Adam A, Wirtz AL, Pham K, Rubenstein LS, Glass N, et al. The prevalence of sexual violence among female refugees in complex humanitarian emergencies: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLOS Currents: Disasters. 2014.

McCleary-Sills J, Namy S, Nyoni J, Rweyemamu D, Salvatory A, Steven E. Stigma, shame and women's limited agency in help-seeking for intimate partner violence. Glob Public Health. 2016;11(1–2):224–35.

Stark L, Warner A, Lehmann H, Boothby N, Ager A. Measuring the incidence and reporting of violence against women and girls in Liberia using the 'neighborhood method. Confl Health. 2013;7(1):20.

Wirtz AL, Glass N, Pham K, Aberra A, Rubenstein LS, Singh S, et al. Development of a screening tool to identify female survivors of gender-based violence in a humanitarian setting: qualitative evidence from research among refugees in Ethiopia. Confl Health. 2013;7(1):13.

Wirtz AL, Glass N, Pham K, Perrin N, Rubenstein LS, Singh S, et al. Comprehensive development and testing of the ASIST-GBV, a screening tool for responding to gender-based violence among women in humanitarian settings. Confl Health. 2016;10:7.

Heise L. What Works to Prevent Partner Violence? An Evidence Overview: Working Paper. London: STRIVE Research Consortium,London School of Hygiene and Tropical. Medicine. 2011.

Read-Hamilton S, Marsh M. The communities care programme: changing social norms to end violence against women and girls in conflict-affected communities. Gend Dev. 2016;24(2):261–76.

Glass N, Perrin N, Clough A, Desgroppes A, Kaburu FN, Melton J, et al. Evaluating the communities care program: best practice for rigorous research to evaluate gender based violence prevention and response programs in humanitarian settings. Confl Health. 2018;12:5.

Berkowitz AD. An Overview of the Social Norms Approach. Changing the Culture of College Drinking: A Socially Situated Health Communication Campaign: Hampton Press; 2005. p. 303.

Bicchieri C. The grammar of society : the nature and dynamics of social norms. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2006.

Mackie G, Moneti F, Shakya H, Denny E. What are social norms? How are they measured? New York: UNICEF/UCSD Center on Global Justice; 2015 July 27.

Alexander-Scott M. Emily bell,, Holden J. DFID Guidence note: shifting social norms to tackle violence against women and girls. London: DFID Violence Against Women Helpdesk; 2016.

UNICEF. Communities care: transforming lives and preventing violence toolkit. New York: UNICEF; 2014.

Barker G, Nascimento M, Segundo M, Pulerwitz J. How do we know if men have changed? Promoting and measuring attitude change with young men: lessons from program H in Latin America. In: Ruxton S, editor. Gender equality and men: learning from practice. Oxfam, UK: Oxford; 2004. p. 147–61.

Chapter Google Scholar

Leon F, Foreit J. Developing women’s empowerment scales and predicting contraceptive use: A study of 12 countries’ demographic and health surveys (DHS) data. Draft manuscript ed2009.

Schuler SR, Islam F. Women's acceptance of intimate partner violence within marriage in rural Bangladesh. Stud Fam Plan. 2008;39(1):49–58.

Schuler SR, Lenzi R, Yount KM. Justification of intimate partner violence in rural Bangladesh: what survey questions fail to capture. Stud Fam Plan. 2011;42(1):21–8.

Tsai AC, Kakuhikire B, Perkins JM, Vorechovska D, McDonough AQ, Ogburn EL, et al. Measuring personal beliefs and perceived norms about intimate partner violence: population-based survey experiment in rural Uganda. PLoS Med. 2017;14(5).

Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd ed. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1988.

World Health Organization. Changing cultural and social norms that support violence. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2009.

Adjei SB. “Correcting an erring wife is Normal”: moral discourses of spousal violence in Ghana. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2015;33(12):1871–92.

Tchokossa AM, Golfa T, Salau OR, Ogunfowokan AA. Perceptions and experiences of intimate partner violence among women in Ile-Ife Osun state Nigeria. Int J Caring Sci. 2018:267–78.

Costello AB, Osborne J. Best practices in exploratory factor analysis: four recommendations for getting the Most from your analysis. Pract Assess Res Eval. 2005;10(7):1–9.

Download references

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge our committed and talented implementing partners in South Sudan, two national NGOs, Voice for Change in Central Equatoria State and The Organization for Children Harmony in Warrup State. In Somalia, the Italian NGO, Comitato Internazionale per LoSviluppo dei Popoli (CISP) Mogadishu and other regions of the country.

United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) provided the funding for the Communities Care program.

Availability of data and materials

The Communities Care program toolkit is available through United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). Requests for research data and materials can be obtained by contacting UNICEF.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Johns Hopkins School of Nursing, 525 North Wolfe Street, Baltimore, MD, 21205, USA

Nancy Perrin, Amber Clough, Rachael Turner, Lori Heise & Nancy Glass

UNICEF, New York, NY, USA

Mendy Marsh

Comitato Internazionale per lo Sviluppo dei Popoli (CISP) Somalia, Nairobi, Kenya

Amelie Desgroppes, Ali Abdi & Francesco Kaburu

Voice For Change, Yei, South Sudan

Clement Yope Phanuel

Norwegian Church Aid, Oslo, Norway

Silje Heitmann

UNICEF, Geneva, Switzerland

Masumi Yamashina

UNICEF Somalia, Mogadishu, Somalia

Brendan Ross

Consultant, Gender based violence in Emergencies, Sydney, Australia

Sophie Read-Hamilton

Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, USA

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

NP, NG, MM, AC, SRH, SH, FK, AD, MY designed the study. MM, SRH, NP, RT, LH, NG and AC identified the theoretical framework for the formative and psychometric phases of the study. NG, NP, and LH conducted the psychometric analysis. MY, CYP, AA, AC, NP and NG implemented and interpretation the study findings in South Sudan and SH, BR, AD, AA, FK, AC, NG and NP implemented and interpretation of the study findings in Somalia. NP, NG, RT, AC and LH finalized the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Nancy Glass .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

The appropriate federal and state government ministry in each of Somalia and South Sudan and the Johns Hopkins Medical Institution Institutional Review Board (IRB) approved the study protocol and oral consent. The government ministry provided a letter of approval to Johns Hopkins and the local implementing partners to use as they reached out to authorities and key stakeholders to implement the research in each participating community.

Consent for publication

The authors of the manuscript provide consent for the publication.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional file

Additional file 1:.

Social Norms and Beliefs about Gender Based Violence Scale. (DOCX 17 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Perrin, N., Marsh, M., Clough, A. et al. Social norms and beliefs about gender based violence scale: a measure for use with gender based violence prevention programs in low-resource and humanitarian settings. Confl Health 13 , 6 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13031-019-0189-x

Download citation

Received : 07 September 2018

Accepted : 20 February 2019

Published : 08 March 2019

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s13031-019-0189-x

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Global health

- Humanitarian

- Social norms

Conflict and Health

ISSN: 1752-1505

- Submission enquiries: [email protected]

Home — Essay Samples — Social Issues — Gender Discrimination — Combating Gender-Based Violence

Combating Gender-based Violence

- Categories: Gender Discrimination

About this sample

Words: 563 |

Published: Jan 29, 2024

Words: 563 | Page: 1 | 3 min read

Table of contents

Definition and types of gender-based violence, causes of gender-based violence, effects of gender-based violence, existing strategies and interventions to address gender-based violence, challenges in addressing gender-based violence, recommendations and conclusion.

- World Health Organization. (2021). Violence against women. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/violence-against-women

- European Parliament. (2012). Istanbul Convention on preventing and combating violence against women and domestic violence. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2014/536291/EPRS_BRI(2014)536291_EN.pdf

- UN Women. (2020). Men and boys are called to action to end gender-based violence. https://www.unwomen.org/en/news/stories/2020/11/feature-men-and-boys-are-called-to-action-to-end-gender-based-violence

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Verified writer

- Expert in: Social Issues

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

2 pages / 911 words

3 pages / 1462 words

6 pages / 2671 words

2 pages / 1131 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Gender Discrimination

Nathaniel Hawthorne's The Scarlet Letter is a renowned novel that explores the complex themes of sin, guilt, and redemption in Puritan society. One striking character in the narrative is Pearl, the illegitimate daughter of [...]

Women are the warriors, the soldiers, the fighter. Be it the Battlefield, Be it a Home, Be it the armed forces, or Be it anything. In human history, even from before the 9th century, women are serving in fighting roles on the [...]

Across cultures, women have faced discrimination by their own society due to the customs and values set in place over thousands of years by men. The gender construct is socially accepted behaviors and roles within cultures that [...]

In her thought-provoking book "Pink Think," Lynn Peril provides an insightful analysis of how gender stereotypes have been perpetuated and reinforced through the commercial and cultural messages of the postwar American era. [...]

Women have faced various forms of institutionalized discrimination throughout history and across different cultures. This undeniable truth has been the driving force behind the feminist movement, which has had both positive and [...]

What a piece of work is woman!In form, in moving, how express and admirable!In action how like an angel.In apprehension how like a God!And at the same time it is also said.Frailty — thy name is [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

Gender-Based Violence

- Reference work entry

- Cite this reference work entry

- Anthony Collins 2

931 Accesses

1 Citations

1 Altmetric

Introduction

Gender-based violence (GBV) refers to violence directed towards an individual or group on the basis of their gender. Gender-based violence was traditionally conceptualized as violence by men against women but is now increasingly taken to include a wider range of hostilities based on sexual identity and sexual orientation, including certain forms of violence against men who do not embody the dominant forms of masculinity.

While most earlier sources take gender-based violence as synonymous with violence against women (United Nations General Assembly, 1993 ), O’Toole and Schiffman ( 1997 ) offer a broad definition to include “any interpersonal, organisational or politically orientated violation perpetrated against people due to their gender identity, sexual orientation, or location in the hierarchy of male-dominated social systems such as family, military, organisations, or the labour force” (p. xii). This definition is useful in that it potentially includes not only...

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Institutional subscriptions

Brown, L. (1992). Personality and psychopathology: Feminist reappraisals . New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Google Scholar

Brownmiller, S. (1975). Against our will: Men, women and rape . New York, NY: Simon and Schuster.

Burgess, A. W., & Holmstrom, L. L. (1974). Rape trauma syndrome. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 131 (9), 981–986.

PubMed Google Scholar

Collins, A., Loots, L., Mistrey, D., & Meyiwa, T. (2009). Nobody’s business: Proposals for reducing gender-based violence at a south african university. Agenda, 80 , 33–41.

Ellsberg, M., & Heise, L. L. (2005). Researching violence against women: A practical guide for researchers and activists . Washington, DC: World Health Organization, PATH.

Garcia-Moreno, C., & Heise, L. (2002). Violence by intimate partners. In E. G. Krug, L. L. Dahlberg, J. A. Mercy, A. B. Zwi, & R. Lozano (Eds.), World report on violence and health . Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

Herman, J. (1997). Trauma and recovery: From domestic abuse to political terror . London, England: Pandora.

Jewkes, R., Levin, J., Penn-Kekana, L., Ratsaka, M., & Schrieber., M. (1991). ‘He must give me money, he mustn’t beat me’: Violence against women in three South African provinces . Pretoria, South Africa: CERSA Women’s Health, Medical Research Council.

Jewkes, R., & Wood, K. (1997). Violence, rape and sexual coercion: Everyday love in a South African township. Gender and Development, 5 (2), 41–46.

Koss, M. P., & Cleveland, H. H. (1997). Stepping on toes: Social roots of date rape lead to intractability and politicization. In M. D. Schwartz (Ed.), Researching sexual violence against women: Methodological and personal perspectives (pp. 4–22). London, England: Sage.

Martin, S. L., & Curtis, S. (2004). Gender-based violence and HIV/AIDS: Recognizing the links and acting on evidence. The Lancet, 363 , 9419. Health Module.

O’Toole, L. L., & Schiffman, J. R. (1997). Gender violence: Interdisciplinary perspectives . New York: New York University Press.

Russell, D. E. H. (1984). Sexual exploitation: Rape, child sexual abuse, and workplace harassment . Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

United Nations General Assembly. (1993, December 20). Declaration on the elimination of violence against women. In General resolution A/RES/48/104 85th plenary meeting .

Vetten, L. (1997). The rape surveillance project. Agenda, 36 , 45–49.

Vetten, L. (2000). Gender, race and power dynamics in the face of social change: Deconstructing violence against women in South Africa. In J. Y. Park, J. Fedler, & Z. Dangor (Eds.), Reclaiming women’s spaces: New perspectives on violence against women and sheltering in South Africa (pp. 47–80). Johannesburg, South Africa: Nisaa Institute for Women’s Development.

Vogelman, L. (1990). The sexual face of violence: Rapists on rape . Johannesburg, South Africa: Ravan Press.

Walker, L. E. (1979). The battered woman . New York, NY: Harper and Row.

Wood, K., & Jewkes, R. (1997). Violence, rape and sexual coercion: Everyday love in a South African township. Gender and Development, 5 (2), 41–46.

Online Resources

fap.sagepub.com/

www.agenda.org.za/

www.apa.org/about/division/div35.aspx

www.apa.org/about/division/activities/abuse.aspx

www.genderlinks.org.za/page/gender-justice-mapping-violence-prevention-models

www.unfpa.org/gender/violence.htm ; www.who.int/topics/gender_based_violence/en/

www.who.int/topics/gender/violence/gbv/en/index1.html

www.un.org/womenwatch/directory/gender_training_90.htm

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Journalism and Media Studies, Rhodes University, Grahamstown, South Africa

Anthony Collins

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Anthony Collins .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Department of Psychology, York University, Toronto, ON, Canada

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2014 Springer Science+Business Media New York

About this entry

Cite this entry.

Collins, A. (2014). Gender-Based Violence. In: Teo, T. (eds) Encyclopedia of Critical Psychology. Springer, New York, NY. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-5583-7_121

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-5583-7_121

Publisher Name : Springer, New York, NY

Print ISBN : 978-1-4614-5582-0

Online ISBN : 978-1-4614-5583-7

eBook Packages : Springer Reference Behavioral Sciences

Share this entry

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Causes and Effects of Gender-Based Violence

Related Papers

Annals of the New York Academy of …

Angela Pirlott