- Utility Menu

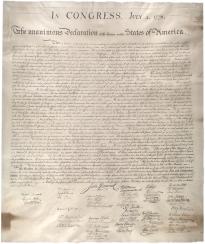

Text of the Declaration of Independence

Note: The source for this transcription is the first printing of the Declaration of Independence, the broadside produced by John Dunlap on the night of July 4, 1776. Nearly every printed or manuscript edition of the Declaration of Independence has slight differences in punctuation, capitalization, and even wording. To find out more about the diverse textual tradition of the Declaration, check out our Which Version is This, and Why Does it Matter? resource.

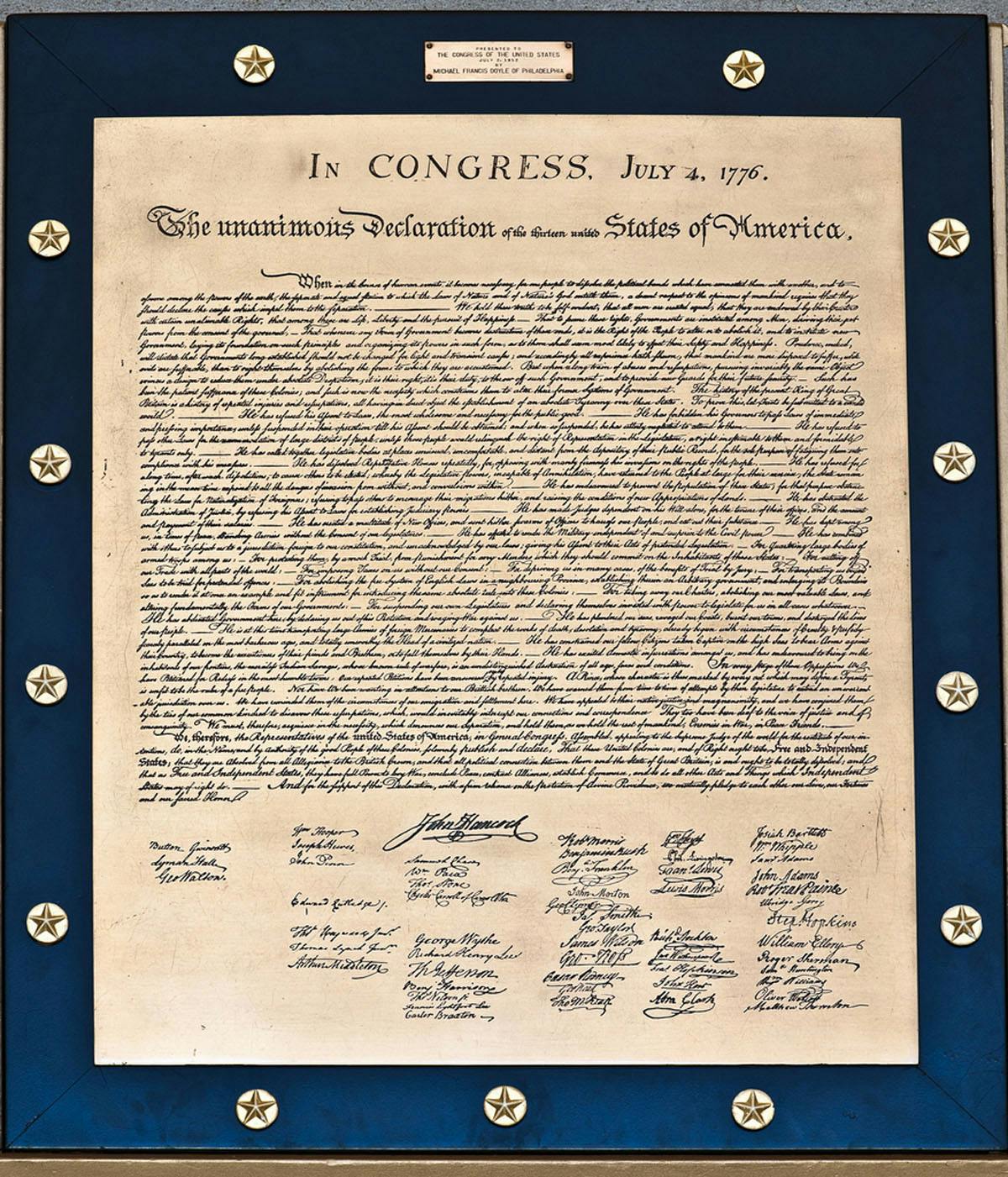

WHEN in the Course of human Events, it becomes necessary for one People to dissolve the Political Bands which have connected them with another, and to assume among the Powers of the Earth, the separate and equal Station to which the Laws of Nature and of Nature’s God entitle them, a decent Respect to the Opinions of Mankind requires that they should declare the causes which impel them to the Separation. We hold these Truths to be self-evident, that all Men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness—-That to secure these Rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just Powers from the Consent of the Governed, that whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these Ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government, laying its Foundation on such Principles, and organizing its Powers in such Form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their Safety and Happiness. Prudence, indeed, will dictate that Governments long established should not be changed for light and transient Causes; and accordingly all Experience hath shewn, that Mankind are more disposed to suffer, while Evils are sufferable, than to right themselves by abolishing the Forms to which they are accustomed. But when a long Train of Abuses and Usurpations, pursuing invariably the same Object, evinces a Design to reduce them under absolute Despotism, it is their Right, it is their Duty, to throw off such Government, and to provide new Guards for their future Security. Such has been the patient Sufferance of these Colonies; and such is now the Necessity which constrains them to alter their former Systems of Government. The History of the present King of Great-Britain is a History of repeated Injuries and Usurpations, all having in direct Object the Establishment of an absolute Tyranny over these States. To prove this, let Facts be submitted to a candid World. He has refused his Assent to Laws, the most wholesome and necessary for the public Good. He has forbidden his Governors to pass Laws of immediate and pressing Importance, unless suspended in their Operation till his Assent should be obtained; and when so suspended, he has utterly neglected to attend to them. He has refused to pass other Laws for the Accommodation of large Districts of People, unless those People would relinquish the Right of Representation in the Legislature, a Right inestimable to them, and formidable to Tyrants only. He has called together Legislative Bodies at Places unusual, uncomfortable, and distant from the Depository of their public Records, for the sole Purpose of fatiguing them into Compliance with his Measures. He has dissolved Representative Houses repeatedly, for opposing with manly Firmness his Invasions on the Rights of the People. He has refused for a long Time, after such Dissolutions, to cause others to be elected; whereby the Legislative Powers, incapable of Annihilation, have returned to the People at large for their exercise; the State remaining in the mean time exposed to all the Dangers of Invasion from without, and Convulsions within. He has endeavoured to prevent the Population of these States; for that Purpose obstructing the Laws for Naturalization of Foreigners; refusing to pass others to encourage their Migrations hither, and raising the Conditions of new Appropriations of Lands. He has obstructed the Administration of Justice, by refusing his Assent to Laws for establishing Judiciary Powers. He has made Judges dependent on his Will alone, for the Tenure of their Offices, and the Amount and Payment of their Salaries. He has erected a Multitude of new Offices, and sent hither Swarms of Officers to harrass our People, and eat out their Substance. He has kept among us, in Times of Peace, Standing Armies, without the consent of our Legislatures. He has affected to render the Military independent of and superior to the Civil Power. He has combined with others to subject us to a Jurisdiction foreign to our Constitution, and unacknowledged by our Laws; giving his Assent to their Acts of pretended Legislation: For quartering large Bodies of Armed Troops among us: For protecting them, by a mock Trial, from Punishment for any Murders which they should commit on the Inhabitants of these States: For cutting off our Trade with all Parts of the World: For imposing Taxes on us without our Consent: For depriving us, in many Cases, of the Benefits of Trial by Jury: For transporting us beyond Seas to be tried for pretended Offences: For abolishing the free System of English Laws in a neighbouring Province, establishing therein an arbitrary Government, and enlarging its Boundaries, so as to render it at once an Example and fit Instrument for introducing the same absolute Rule into these Colonies: For taking away our Charters, abolishing our most valuable Laws, and altering fundamentally the Forms of our Governments: For suspending our own Legislatures, and declaring themselves invested with Power to legislate for us in all Cases whatsoever. He has abdicated Government here, by declaring us out of his Protection and waging War against us. He has plundered our Seas, ravaged our Coasts, burnt our Towns, and destroyed the Lives of our People. He is, at this Time, transporting large Armies of foreign Mercenaries to compleat the Works of Death, Desolation, and Tyranny, already begun with circumstances of Cruelty and Perfidy, scarcely paralleled in the most barbarous Ages, and totally unworthy the Head of a civilized Nation. He has constrained our fellow Citizens taken Captive on the high Seas to bear Arms against their Country, to become the Executioners of their Friends and Brethren, or to fall themselves by their Hands. He has excited domestic Insurrections amongst us, and has endeavoured to bring on the Inhabitants of our Frontiers, the merciless Indian Savages, whose known Rule of Warfare, is an undistinguished Destruction, of all Ages, Sexes and Conditions. In every stage of these Oppressions we have Petitioned for Redress in the most humble Terms: Our repeated Petitions have been answered only by repeated Injury. A Prince, whose Character is thus marked by every act which may define a Tyrant, is unfit to be the Ruler of a free People. Nor have we been wanting in Attentions to our British Brethren. We have warned them from Time to Time of Attempts by their Legislature to extend an unwarrantable Jurisdiction over us. We have reminded them of the Circumstances of our Emigration and Settlement here. We have appealed to their native Justice and Magnanimity, and we have conjured them by the Ties of our common Kindred to disavow these Usurpations, which, would inevitably interrupt our Connections and Correspondence. They too have been deaf to the Voice of Justice and of Consanguinity. We must, therefore, acquiesce in the Necessity, which denounces our Separation, and hold them, as we hold the rest of Mankind, Enemies in War, in Peace, Friends. We, therefore, the Representatives of the UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, in General Congress, Assembled, appealing to the Supreme Judge of the World for the Rectitude of our Intentions, do, in the Name, and by Authority of the good People of these Colonies, solemnly Publish and Declare, That these United Colonies are, and of Right ought to be, Free and Independent States; that they are absolved from all Allegiance to the British Crown, and that all political Connection between them and the State of Great-Britain, is and ought to be totally dissolved; and that as Free and Independent States, they have full Power to levy War, conclude Peace, contract Alliances, establish Commerce, and to do all other Acts and Things which Independent States may of right do. And for the support of this Declaration, with a firm Reliance on the Protection of divine Providence, we mutually pledge to each other our Lives, our Fortunes, and our sacred Honor.

Signed by Order and in Behalf of the Congress, JOHN HANCOCK, President.

Attest. CHARLES THOMSON, Secretary.

United States Declaration of Independence Definition Essay

Declaration of Independence is a document that is most treasured in United State since it announced independence to American colonies which were at war with Great Britain. It was drafted by Thomas Jefferson back in July 1776 and contained formal explanation of the reason why the Congress had declared independence from Great Britain.

Therefore, the document marked the independence of the thirteen colonies of America, a condition which had caused revolutionary war. America celebrates its day of independence on 4 th July, the day when the congress approved the Declaration for Independence (Becker, 2008). With that background in mind, this essay shall give an analysis of the key issues closely linked to the United States Declaration of Independence.

As highlighted in the introductory part, there was the revolutionary war in the thirteen American colonies before the declaration for independence that had been going on for about a year. Immediately after the end of the Seven Years War, the relationship between American colonies and their mother country started to deteriorate. In addition, some acts which were established in order to increase tax revenue from the colonies ended up creating a tax dispute between the colonies and the Government (Fradin, 2006).

The main reason why the Declaration for Independence was written was to declare the convictions of Americans especially towards their rights. The main aim was to declare the necessity for independence especially to the colonist as well as to state their view and position on the purpose of the government. In addition, apart from making their grievances known to King George III, they also wanted to influence other foreigners like the France to support them in their struggle towards independence.

Most authors and historians believe that the main influence of Jefferson was the English Declaration of Rights that marked the end King James II Reign. As much as the influence of John Locke who was a political theorist from England is questioned, it is clear that he influenced the American Revolution a great deal. Although most historians criticize the Jefferson’s influence by some authors like Charles Hutcheson, it is clear that the philosophical content of the Declaration emanates from other philosophical writings.

The self evident truths in the Declaration for Independence is that all men are created equal and do also have some rights which ought not to be with held at all costs. In addition, the document also illustrated that government is formed for the sole purpose of protecting those rights as it is formed by the people who it governs. Finally, if the government losses the consent, it then qualifies to be either replaced or abolished. Such truths are not only mandatory but they do not require any further emphasis.

Therefore, being self evident means that each truth speaks on its own behalf and should not be denied at whichever circumstances (Zuckert, 1987). The main reason why they were named as self evident was to influence the colonists to see the reality in the whole issue. Jefferson based his argument from on the theory of natural rights as illustrated by John Locke who argued that people have got rights which are not influenced by laws in the society (Tuckness, 2010).

One of the truths in the Declaration for Independence is the inalienable rights which are either individual or collective. Such rights are inclusive of right to liberty, life and pursuit of happiness. Unalienable rights means rights which cannot be denied since they are given by God. In addition, such rights cannot even be sold or lost at whichever circumstance. Apart from individual rights, there are also collective rights like the right of people to chose the right government and also to abolish it incase it fails achieve its main goal.

The inalienable goals are based on the law of nature as well as on the nature’s God as illustrated in the John Locke’s philosophy. It is upon the government to recognize that individuals are entitled to unalienable rights which are bestowed by God. Although the rights are not established by the civil government, it has a great role to ensure that people are able to express such laws in the constitution (Morgan, 2010).

Explaining the purpose of the government was the major intent of the Declaration for Independent. The document explains explicitly that the main purpose is not only to secure but also to protect the rights of the people from individual and life events that threaten them. However, it is important to note that the government gets its power from the people it rules or governs.

The purpose of the government of protecting the God given rights of the people impacts the decision making process in several ways. To begin with, the government has to consider the views of the people before making major decisions failure to which it may be considered unworthy and be replaced. Therefore, the decision making process becomes quite complex as several positions must be taken in to consideration.

The declaration identifies clearly the conditions under which the government can be abolished or replaced. For example, studies of Revolutionary War and Beyond, states that “any form of government becomes destructive of these ends; it is the right of the people, to alter or abolish it and institute a new government” (par. 62010). Therefore, document illustrated that the colonists were justified to reject or abolish the British rule.

The declaration was very significant especially due to the fact that it illustrated explicitly the conditions which were present in America by the time it was being made. For example, one of the key grievances of the thirteen colonies was concerning the issue of slave trade. The issue of abolishing slavery was put in the first draft of the declaration for independent although it was scrapped off later since the southern states were against the abolishment of slave trade.

Another issue which was illustrated in the declaration was the fact that the king denied the colonists the power to elect their representatives in the legislatures. While the colonists believed that they had the right to choose the government to govern them, in the British government, it was the duty of the King to do so.

Attaining land and migrating to America was the right of colonists to liberty and since the King had made it extremely difficult for the colonists to do so; the Declaration was very significant in addressing such grievances. There are many more problems that were present that were addressed by the Declaration as it was its purpose to do so.

Becker, C. L. (2008). The Declaration of Independence: A Study in the History of Political Ideas. Illinois: BiblioBazaar, LLC .

Fradin, D. B. (2006). The Declaration of Independence. New York : Marshall Cavendish.

Morgan, K. L. (2010). The Declaration of Independence, Equality and Unalienable Rights . Web.

Revolutionary War and Beyond. (2010). The Purpose of the Declaration of Independence . Web.

Tuckness, A. (2010). Locke’s Political Philosophy . Web.

Zuckert, M. P. (1987). Self-Evident Truth and the Declaration of Independence. The Review of Politics , 49 (3), 319-339.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2019, July 16). United States Declaration of Independence. https://ivypanda.com/essays/declaration-of-independence/

"United States Declaration of Independence." IvyPanda , 16 July 2019, ivypanda.com/essays/declaration-of-independence/.

IvyPanda . (2019) 'United States Declaration of Independence'. 16 July.

IvyPanda . 2019. "United States Declaration of Independence." July 16, 2019. https://ivypanda.com/essays/declaration-of-independence/.

1. IvyPanda . "United States Declaration of Independence." July 16, 2019. https://ivypanda.com/essays/declaration-of-independence/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "United States Declaration of Independence." July 16, 2019. https://ivypanda.com/essays/declaration-of-independence/.

- Why Was the Declaration of Independence Written?

- Jefferson and Writing the Declaration of Independence

- Declaration of Independence - Constitution

- Thomas Jefferson on Slavery and Declaration of Independence

- Declaration of Independence: Thomas Paine, Common Sense and Thomas Jefferson

- Major Grievances of American People Expressed in Major Documents of the Nation

- Thomas Jefferson: The Author of America

- Fundamental Right to Live: Abolish the Death Penalty

- The Declaration of Independence: The Three Copies and Drafts, and Their Relation to Thomas Paine’s “Common Sense”

- Thomas Jefferson’s Personal Life

- The Concept of Reconstruction

- U.S. Civil Rights Protests of the Middle 20th Century

- Battle of Blair Mountain

- History and Heritage in Determining Present and Future

- Jamestown Rediscovery Artifacts: What Archeology Can Tell Us

The Declaration of Independence

21 pages • 42 minutes read

A modern alternative to SparkNotes and CliffsNotes, SuperSummary offers high-quality Study Guides with detailed chapter summaries and analysis of major themes, characters, and more.

Essay Analysis

Key Figures

Symbols & Motifs

Literary Devices

Important Quotes

Essay Topics

Discussion Questions

In what ways is the Declaration of Independence a timeless document, and in what ways is it a product of a specific time and place? Is it primarily a historical document, or is it relevant to the modern era?

How does the Declaration of Independence define a tyrant? And how convincing is the argument the signers make that George III was a tyrant?

The Declaration of Independence does not establish any laws for the United States. But how do its ideas influence the Constitution or other documents that do establish laws?

Don't Miss Out!

Access Study Guide Now

Related Titles

By Thomas Jefferson

Notes on the State of Virginia

Thomas Jefferson

Featured Collections

American Revolution

View Collection

Books on Justice & Injustice

Books on U.S. History

Nation & Nationalism

Politics & Government

Required Reading Lists

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Why Was the Declaration of Independence Written?

By: Sarah Pruitt

Updated: June 22, 2023 | Original: June 29, 2018

When the first skirmishes of the Revolutionary War broke out in Massachusetts in April 1775, few people in the American colonies wanted to separate from Great Britain entirely. But as the war continued, and Britain called out massive armed forces to enforce its will, more and more colonists came to accept that asserting independence was the only way forward.

And the Declaration of Independence would play a critical role in unifying the colonies from the bloody struggle they now faced.

The Road to Revolution Was Paved with Taxes

Over the decade following the passage of the Stamp Act in 1765, a series of unpopular British laws met with stiff opposition in the colonies, fueling a bitter struggle over whether Parliament had the right to tax the colonists without the consent of the representative colonial governments. This struggle erupted into violence in 1770 when British troops killed five colonists in the Boston Massacre .

Three years later, outrage over the Tea Act of 1773 prompted colonists to board an East India Company ship in Boston Harbor and dump its cargo into the sea in the now-infamous Boston Tea Party .

In response, Britain cracked down further with the Coercive Acts, going so far as to revoke the colonial charter of Massachusetts and close the port of Boston. Resistance to the Intolerable Acts, as they became known, led to the formation of the First Continental Congress in Philadelphia in 1774, which denounced “taxation without representation” - but stopped short of demanding independence from Britain.

Would Colonists Reconcile or Separate?

Then the first shots rang out between colonial and British forces at Lexington and Concord, and the Battle of Bunker Hill cost hundreds of American lives, along with 1,000 killed on the British side.

Some 20,000 troops under General George Washington faced off against a British garrison in the Boston Siege, which ended when the British evacuated in March 1776. Washington then moved his Continental Army to New York, where he assumed (correctly) that a major British invasion would soon take place.

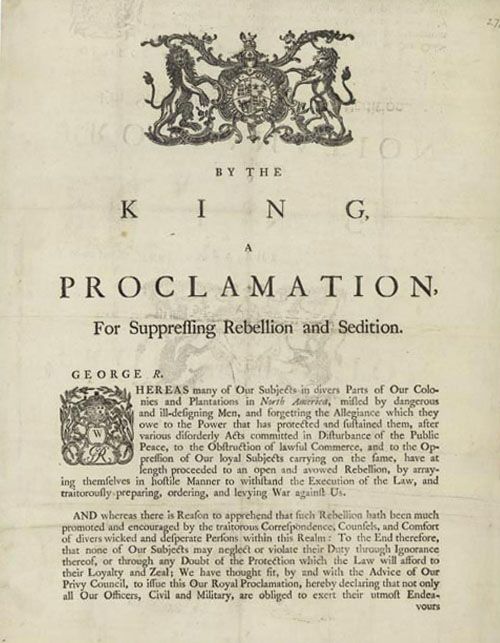

Meanwhile, many in the Continental Congress still clung to the assumption that reconciliation with Britain was the ultimate goal. This would soon change, thanks in part to the actions of King George III , who in October 1775 denounced the colonies in front of Parliament and began building up his army and navy to crush their rebellion.

In order to have any hope of defeating Britain, the colonists would need support from foreign powers (especially France), which Congress knew they could only get by declaring themselves a separate nation.

Thomas Paine Disavowed the Monarchy

In his bestselling pamphlet, “Common Sense,” a recent English immigrant named Thomas Paine also helped push the colonists along on their path toward independence.

“His argument was that we had to break from Britain because the system of the British constitution was hopelessly flawed,” the late Pauline Maier , professor of history at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), said in a 2013 lecture on “The Making of the Declaration of Independence.”

“[Britain] had hereditary rule, it had kings—you could never have freedom so long as you had hereditary rule.”

After Virginia delegate Richard Henry Lee introduced a motion to declare independence on June 7, 1776, Congress formed a committee to draft a statement justifying the break with Great Britain.

Who Wrote the Declaration of Independence?

The initial draft of the Declaration of Independence was written by Thomas Jefferson and was presented to the entire Congress on June 28 for debate and revision.

In addition to Jefferson’s eloquent preamble, the document included a long list of grievances against King George III, who was accused of committing many “injuries and usurpations” in his quest to establish “an absolute tyranny over these States.”

The Declaration of Independence United the Colonists

After two days of editing and debate, the Congress adopted the Declaration of Independence on July 4, 1776, even as a large British fleet and more than 34,000 troops prepared to invade New York. By the time it was formally signed on August 2, printed copies of the document were spreading around the country, being reprinted in newspapers and publicly read aloud.

While the road to independence had been long and twisted, the effect of its declaration made an impact right away.

“It changed the whole character of the war,” Maier said. “These were people who for a year had been making war against a king with whom they were trying to effect a reconciliation, to whom they were publicly professing loyalty. Now heart and hand, as one person said, could move together. They had a cause to fight for.”

HISTORY Vault: The American Revolution

Stream American Revolution documentaries and your favorite HISTORY series, commercial-free.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

MA in American History : Apply now and enroll in graduate courses with top historians this summer!

- AP US History Study Guide

- History U: Courses for High School Students

- History School: Summer Enrichment

- Lesson Plans

- Classroom Resources

- Spotlights on Primary Sources

- Professional Development (Academic Year)

- Professional Development (Summer)

- Book Breaks

- Inside the Vault

- Self-Paced Courses

- Browse All Resources

- Search by Issue

- Search by Essay

- Become a Member (Free)

- Monthly Offer (Free for Members)

- Program Information

- Scholarships and Financial Aid

- Applying and Enrolling

- Eligibility (In-Person)

- EduHam Online

- Hamilton Cast Read Alongs

- Official Website

- Press Coverage

- Veterans Legacy Program

- The Declaration at 250

- Black Lives in the Founding Era

- Celebrating American Historical Holidays

- Browse All Programs

- Donate Items to the Collection

- Search Our Catalog

- Research Guides

- Rights and Reproductions

- See Our Documents on Display

- Bring an Exhibition to Your Organization

- Interactive Exhibitions Online

- About the Transcription Program

- Civil War Letters

- Founding Era Newspapers

- College Fellowships in American History

- Scholarly Fellowship Program

- Richard Gilder History Prize

- David McCullough Essay Prize

- Affiliate School Scholarships

- Nominate a Teacher

- Eligibility

- State Winners

- National Winners

- Gilder Lehrman Lincoln Prize

- Gilder Lehrman Military History Prize

- George Washington Prize

- Frederick Douglass Book Prize

- Our Mission and History

- Annual Report

- Contact Information

- Student Advisory Council

- Teacher Advisory Council

- Board of Trustees

- Remembering Richard Gilder

- President's Council

- Scholarly Advisory Board

- Internships

- Our Partners

- Press Releases

History Resources

The Declaration of Independence

By tim bailey, view the declaration in the gilder lehrman collection by clicking here and here . for additional primary resources click here and here ., unit objective.

This unit is part of Gilder Lehrman’s series of Common Core State Standards–based teaching resources. These units were written to enable students to understand, summarize, and analyze original texts of historical significance. Students will demonstrate this knowledge by writing summaries of selections from the original document and, by the end of the unit, articulating their understanding of the complete document by answering questions in an argumentative writing style to fulfill the Common Core State Standards. Through this step-by-step process, students will acquire the skills to analyze any primary or secondary source material.

While the unit is intended to flow over a five-day period, it is possible to present and complete the material within a shorter time frame. For example, the first two days can be used to ensure an understanding of the process with all of the activity completed in class. The teacher can then assign lessons three and four as homework. The argumentative essay is then written in class on day three.

Students will be asked to "read like a detective" and gain a clear understanding of the Declaration of Independence. Through reading and analyzing the original text, the students will know what is explicitly stated, draw logical inferences, and demonstrate these skills by writing a succinct summary and then restating that summary in the student’s own words. In the first lesson this will be facilitated by the teacher and done as a whole-class lesson.

Introduction

Tell the students that they will be learning what Thomas Jefferson wrote in 1776 that served to announce the creation of a new nation by reading and understanding Jefferson’s own words. Resist the temptation to put the Declaration into too much context. Remember, we are trying to let the students discover what Jefferson and the Continental Congress had to say and then develop ideas based solely on the original text.

- The Declaration of Independence, abridged (PDF)

- Teacher Resource: Complete text of the Declaration of Independence (PDF). This transcript of the Declaration of Independence is from the National Archives online resource The Charters of Freedom .

- Summary Organizer #1 (PDF)

- All students are given an abridged copy of the Declaration of Independence and are asked to read it silently to themselves.

- The teacher then "share reads" the text with the students. This is done by having the students follow along silently while the teacher begins reading aloud. The teacher models prosody, inflection, and punctuation. The teacher then asks the class to join in with the reading after a few sentences while the teacher continues to read along with the students, still serving as the model for the class. This technique will support struggling readers as well as English Language Learners (ELL).

- The teacher explains that the students will be analyzing the first part of the text today and that they will be learning how to do in-depth analysis for themselves. All students are given a copy of Summary Organizer #1. This contains the first selection from the Declaration of Independence.

- The teacher puts a copy of Summary Organizer #1 on display in a format large enough for all of the class to see (an overhead projector, Elmo projector, or similar device). Explain that today the whole class will be going through this process together.

- Explain that the objective is to select "Key Words" from the first section and then use those words to create a summary sentence that demonstrates an understanding of what Jefferson was saying in the first paragraph.

- Guidelines for selecting the Key Words: Key Words are very important contributors to understanding the text. Without them the selection would not make sense. These words are usually nouns or verbs. Don’t pick "connector" words (are, is, the, and, so, etc.). The number of Key Words depends on the length of the original selection. This selection is 181 words so we can pick ten Key Words. The other Key Words rule is that we cannot pick words if we don’t know what they mean.

- Students will now select ten words from the text that they believe are Key Words and write them in the box to the right of the text on their organizers.

- The teacher surveys the class to find out what the most popular choices were. The teacher can either tally this or just survey by a show of hands. Using this vote and some discussion the class should, with guidance from the teacher, decide on ten Key Words. For example, let’s say that the class decides on the following words: necessary, dissolve, political bonds (yes, technically these are two words, but you can allow such things if it makes sense to do so; just don’t let whole phrases get by), declare, separation, self-evident, created equal, liberty, abolish, and government. Now, no matter which words the students had previously selected, have them write the words agreed upon by the class or chosen by you into the Key Words box in their organizers.

- The teacher now explains that, using these Key Words, the class will write a sentence that restates or summarizes what was stated in the Declaration. This should be a whole-class discussion-and-negotiation process. For example, "It is necessary for us to dissolve our political bonds and declare a separation; it is self-evident that we are created equal and should have liberty, so we need to abolish our current government." You might find that the class decides they don’t need the some of the words to make it even more streamlined. This is part of the negotiation process. The final negotiated sentence is copied into the organizer in the third section under the original text and Key Words sections.

- The teacher explains that students will now be putting their summary sentence into their own words, not having to use Jefferson’s words. Again, this is a class discussion-and-negotiation process. For example, "We need to get rid of our old government so we can be free."

- Wrap up: Discuss vocabulary that the students found confusing or difficult. If you choose, you could have students use the back of their organizers to make a note of these words and their meanings.

Students will be asked to "read like a detective" and gain a clear understanding of what Thomas Jefferson was writing about in the Declaration of Independence. Through reading and analyzing the original text, the students will know what is explicitly stated, draw logical inferences, and demonstrate these skills by writing a succinct summary and then restating that summary in the student’s own words. In the second lesson the students will work with partners and in small groups.

Tell the students that they will be further exploring the meaning of the Declaration of Independence by reading and understanding Jefferson’s text and then being able to tell, in their own words, what he said. Today they will be working with partners and in small groups.

- Summary Organizer #2 (PDF)

- All students are given the abridged copy of the Declaration of Independence and are asked to read it silently to themselves.

- The students and teacher discuss what they did yesterday and what they decided was the meaning of the first selection.

- The teacher then "share reads" the second selection with the students. This is done by having the students follow along silently while the teacher begins reading aloud. The teacher models prosody, inflection, and punctuation. The teacher then asks the class to join in with the reading after a couple of sentences while the teacher continues to read along with the students, still serving as the model for the class. This technique will support struggling readers as well as English Language Learners (ELL).

- The teacher explains that the class will be analyzing the second selection from the Declaration of Independence today. All students are given a copy of Summary Organizer #2. This contains the second selection from the Declaration.

- The teacher puts a copy of Summary Organizer #2 on display in a format large enough for all of the class to see (an overhead projector, Elmo projector, or similar device). Explain that today they will be going through the same process as yesterday but with partners and in small groups.

- Explain that the objective is still to select "Key Words" from the second selection and then use those words to create a summary sentence that demonstrates an understanding of what Jefferson was saying in that selection.

- Guidelines for selecting the Key Words: The guidelines for selecting Key Words are the same as they were yesterday. However, because this paragraph is shorter than the last one at 148 words, they can pick only seven or eight Key Words.

- Pair the students up and have them negotiate which Key Words to select. After they have decided on their words both students will write them in the Key Words box of their organizers.

- The teacher now puts two pairs together. These two pairs go through the same negotiation-and-discussion process to come up with their Key Words. Be strategic in how you make your groups to ensure the most participation by all group members.

- The teacher now explains that by using these Key Words the group will build a sentence that restates or summarizes what Thomas Jefferson was saying. This is done by the group negotiating with its members on how best to build that sentence. Try to make sure that everyone is contributing to the process. It is very easy for one student to take control of the entire process and for the other students to let them do so. All of the students should write their negotiated sentence into their organizers.

- The teacher asks for the groups to share out the summary sentences they have created. This should start a teacher-led discussion that points out the qualities of the various attempts. How successful were the groups at understanding the Declaration and were they careful to only use Jefferson’s Key Words in doing so?

- The teacher explains that the group will now be putting their summary sentence into their own words, not having to use Jefferson’s words. Again, this is a group discussion-and-negotiation process. After they have decided on a sentence it should be written into their organizers. Again, the teacher should have the groups share out and discuss the clarity and quality of the groups’ attempts.

Students will be asked to "read like a detective" and gain a clear understanding of the meaning of the Declaration of Indpendence. Through reading and analyzing the original text, the students will know what is explicitly stated, draw logical inferences, and demonstrate these skills by writing a succinct summary and then restating that summary in the student’s own words. In this lesson the students will be working individually.

Tell the students that they will be further exploring what Thomas Jefferson was saying in the third selection from the Declaration of Independence by reading and understanding Jefferson’s words and then being able to tell, in their own words, what he said. Today they will be working by themselves on their summaries.

- Summary Organizer #3 (PDF)

- The students and teacher discuss what they did yesterday and what they decided was the meaning of the first two selections.

- The teacher then "share reads" the third selection with the students. This is done by having the students follow along silently while the teacher begins reading aloud. The teacher models prosody, inflection, and punctuation. The teacher then asks the class to join in with the reading after a couple of sentences while the teacher continues to read along with the students, still serving as the model for the class. This technique will support struggling readers as well as English Language Learners (ELL).

- The teacher explains that the class will be analyzing the third selection from the Declaration of Independence today. All students are given a copy of Summary Organizer #3. This contains the third selection from the Declaration.

- The teacher puts a copy of Summary Organizer #3 on display in a format large enough for all of the class to see (an overhead projector, Elmo projector, or similar device). Explain that today they will be going through the same process as yesterday, but they will be working by themselves.

- Explain that the objective is still to select "Key Words" from the third paragraph and then use those words to create a summary sentence that demonstrates an understanding of what Jefferson was saying in that selection.

- Guidelines for selecting the Key Words: The guidelines for selecting Key Words are the same as they were yesterday. However, because this paragraph is longer (208 words) they can pick ten Key Words.

- Have the students decide which Key Words to select. After they have chosen their words they will write them in the Key Words box of their organizers.

- The teacher explains that, using these Key Words, each student will build a sentence that restates or summarizes what Jefferson was saying. They should write their summary sentences into their organizers.

- The teacher explains that they will be putting their summary sentence into their own words, not having to use Jefferson’s words. This should be added to their organizers.

- The teacher asks for students to share out the summary sentences they have created. This should start a teacher-led discussion that points out the qualities of the various attempts. How successful were the students at understanding what Jefferson was writing about?

Tell the students that they will be further exploring what Thomas Jefferson was saying in the fourth selection from the Declaration of Independence by reading and understanding Jefferson’s words and then being able to tell, in their own words, what he said. Today they will be working by themselves on their summaries.

- Summary Organizer #4 (PDF)

- The students and teacher discuss what they did yesterday and what they decided was the meaning of the first three selections.

- The teacher then "share reads" the fourth selection with the students. This is done by having the students follow along silently while the teacher begins reading aloud. The teacher models prosody, inflection, and punctuation. The teacher then asks the class to join in with the reading after a couple of sentences while the teacher continues to read along with the students, still serving as the model for the class. This technique will support struggling readers as well as English Language Learners (ELL).

- The teacher explains that the class will be analyzing the fourth selection from the Declaration of Independence today. All students are given a copy of Summary Organizer #4. This contains the fourth selection from the Declaration.

- The teacher puts a copy of Summary Organizer #4 on display in a format large enough for all of the class to see (an overhead projector, Elmo projector, or similar device). Explain that today they will be going through the same process as yesterday, but they will be working by themselves.

- Explain that the objective is still to select "Key Words" from the fourth paragraph and then use those words to create a summary sentence that demonstrates an understanding of what Jefferson was saying in that selection.

- Guidelines for selecting the Key Words: The guidelines for selecting Key Words are the same as they were yesterday. Because this paragraph is the longest (more than 219 words) it will be challenging for them to select only ten Key Words. However, the purpose of this exercise is for the students to get at the most important content of the selection.

- The teacher explains that now they will be putting their summary sentence into their own words, not having to use Jefferson’s words. This should be added to their organizers.

This lesson has two objectives. First, the students will synthesize the work of the last four days and demonstrate that they understand what Jefferson was saying in the Declaration of Independence. Second, the teacher will ask questions of the students that require them to make inferences from the text and also require them to support their conclusions in a short essay with explicit information from the text.

Tell the students that they will be reviewing what Thomas Jefferson was saying in the Declaration of Independence. Second, you will be asking them to write a short argumentative essay about the Declaration; explain that their conclusions must be backed up by evidence taken directly from the text.

- All students are given the abridged copy of the Declaration of Independence and then are asked to read it silently to themselves.

- The teacher asks the students for their best personal summary of selection one. This is done as a negotiation or discussion. The teacher may write this short sentence on the overhead or similar device. The same procedure is used for selections two, three, and four. When they are finished the class should have a summary, either written or oral, of the Declaration in only a few sentences. This should give the students a way to state what the general purpose or purposes of the document were.

- The teacher can have the students write a short essay now addressing one of the following prompts or do a short lesson on constructing an argumentative essay. If the latter is the case, save the essay writing until the next class period or assign it for homework. Remind the students that any arguments they make must be backed up with words taken directly from the Declaration of Independence. The first prompt is designed to be the easiest.

- What are the key arguments that Thomas Jefferson makes for the colonies’ separation from Great Britain?

- Can the Declaration of Independence be considered a declaration of war? Using evidence from the text argue whether this is or is not true.

- Thomas Jefferson defines what the role of government should and should not be. How does he make these arguments?

Stay up to date, and subscribe to our quarterly newsletter.

Learn how the Institute impacts history education through our work guiding teachers, energizing students, and supporting research.

America's Founding Documents

The Declaration of Independence: How Did it Happen?

The revolution begins.

In the early 1770s, more and more colonists became convinced that Parliament intended to take away their freedom. In fact, the Americans saw a pattern of increasing oppression and corruption happening all around the world. Parliament was determined to bring its unruly American subjects to heel. Britain began to prepare for war in early 1775. The first fighting broke out in April in Massachusetts. In August, the King declared the colonists “in a state of open and avowed rebellion.” For the first time, many colonists began to seriously consider cutting ties with Britain. The publication of Thomas Paine’s stirring pamphlet Common Sense in early 1776 lit a fire under this previously unthinkable idea. The movement for independence was now in full swing.

A Proclamation by the King for Supressing Rebellion and Sedition, August 23, 1775

National Archives, Records of the Continental and Confederation Congresses and the Constitutional Convention.

The official portrait of King George III by Johann Zofanny, 1771

Courtesy of the Royal Collection Trust

Choosing Independence

The colonists elected delegates to attend a Continental Congress that eventually became the governing body of the union during the Revolution. Its second meeting convened in Philadelphia in 1775. The delegates to Congress adopted strict rules of secrecy to protect the cause of American liberty and their own lives. In less than a year, most of the delegates abandoned hope of reconciliation with Britain. On June 7, 1776, Richard Henry Lee introduced a resolution “that these united colonies are and of right ought to be free and independent states.” They appointed a Committee of Five to write an announcement explaining the reasons for independence. Thomas Jefferson, who chaired the committee and had established himself as a bold and talented political writer, wrote the first draft.

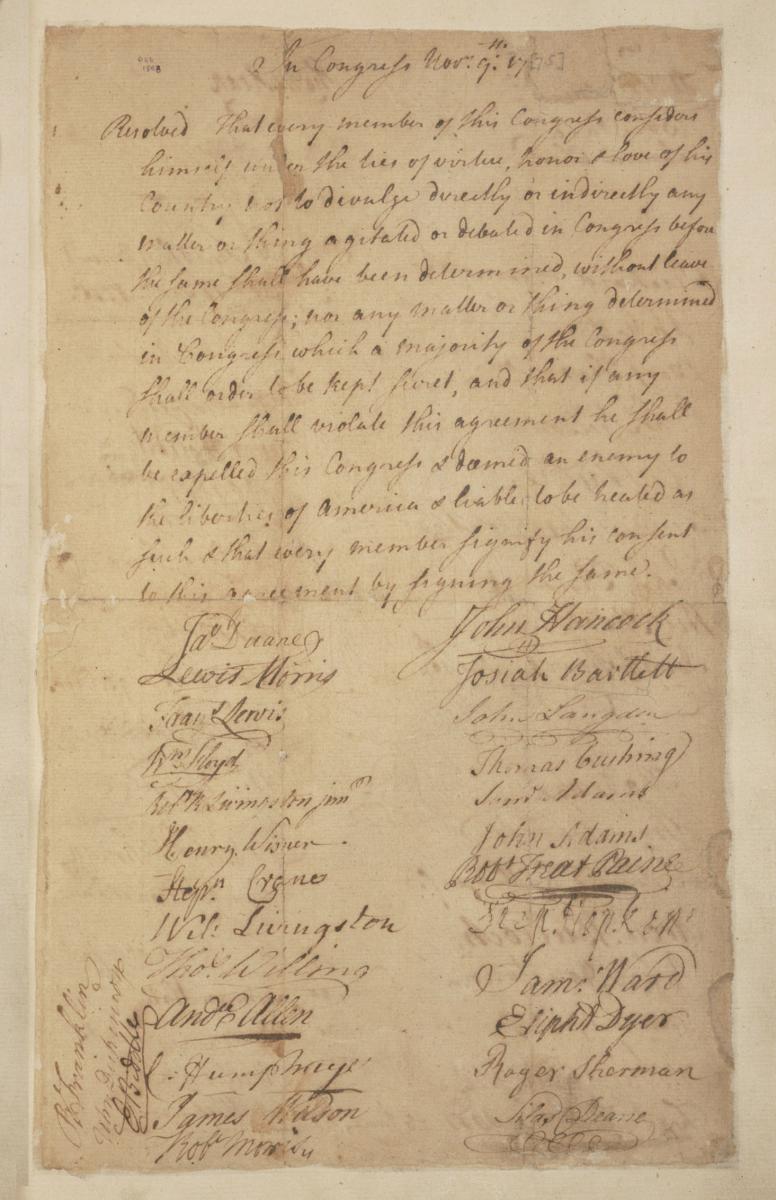

The Agreement of Secrecy

November 9, 1775

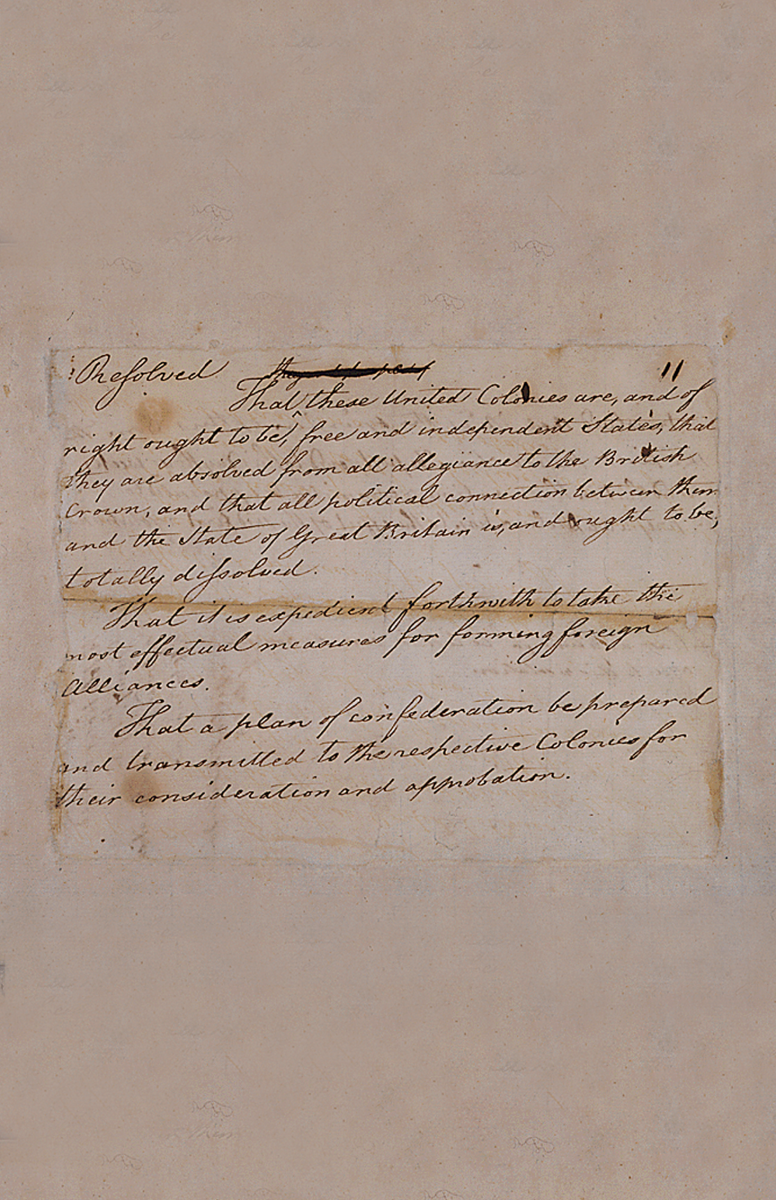

The Lee Resolution

June 2, 1776

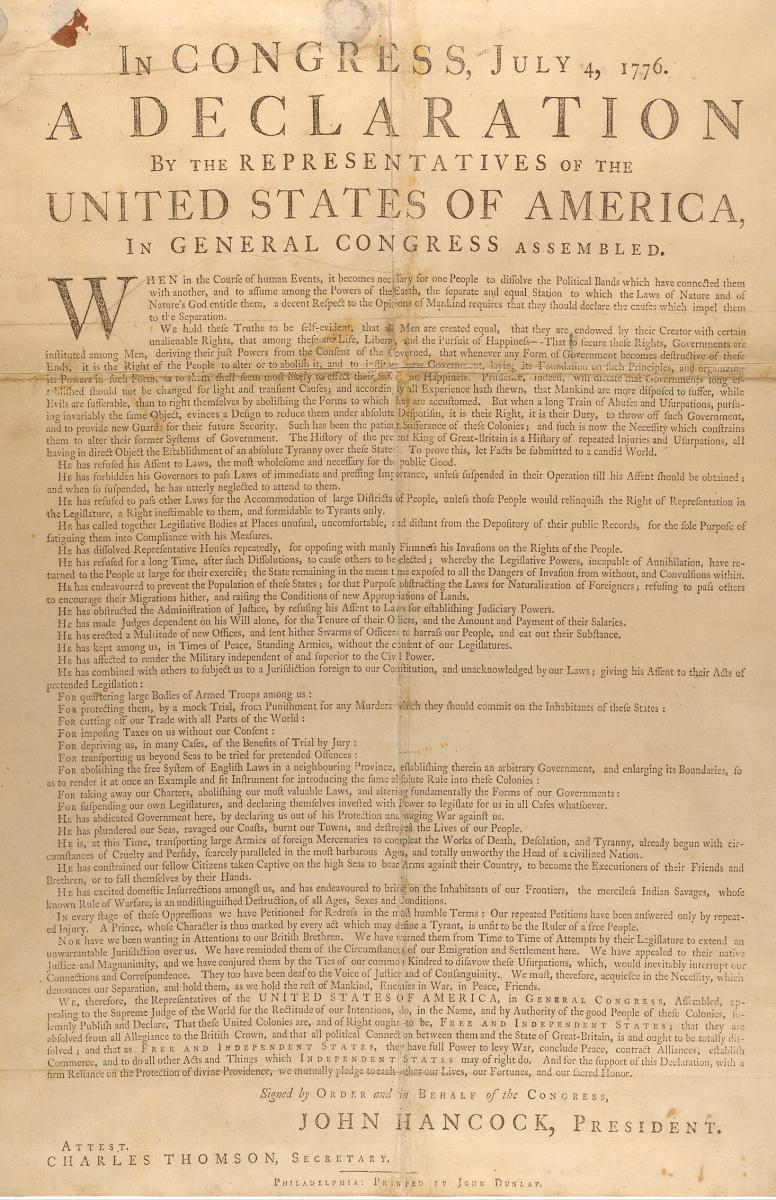

The Dunlap Broadside, July 4, 1776

National Archives, Records of the Continental and Confederation Congresses and the Constitutional Convention

Writing the Declaration

On June 11, 1776, Jefferson holed up in his Philadelphia boarding house and began to write. He borrowed freely from existing documents like the Virginia Declaration of Rights and incorporated accepted ideals of the Enlightenment. Jefferson later explained that “he was not striving for originality of principal or sentiment.” Instead, he hoped his words served as an “expression of the American mind.” Less than three weeks after he’d begun, he presented his draft to Congress. He was not pleased when Congress “mangled” his composition by cutting and changing much of his carefully chosen wording. He was especially sorry they removed the part blaming King George III for the slave trade, although he knew the time wasn’t right to deal with the issue.

Declaring Independence

On July 2, 1776, Congress voted to declare independence. Two days later, it ratified the text of the Declaration. John Dunlap, official printer to Congress, worked through the night to set the Declaration in type and print approximately 200 copies. These copies, known as the Dunlap Broadsides, were sent to various committees, assemblies, and commanders of the Continental troops. The Dunlap Broadsides weren’t signed, but John Hancock’s name appears in large type at the bottom. One copy crossed the Atlantic, reaching King George III months later. The official British response scolded the “misguided Americans” and “their extravagant and inadmissable Claim of Independency”.

What Does it Say? How Was it Made?

Background Essay: Applying the Ideals of the Declaration of Independence

Guiding Questions: Why have Americans consistently appealed to the Declaration of Independence throughout U.S. history? How have the ideals in the Declaration of Independence affected the struggle for equality throughout U.S. history?

- I can explain how the ideals of the Declaration of Independence have inspired individuals and groups to make the United States a more equal and just society.

Essential Vocabulary

In an 1857 speech criticizing the Supreme Court decision in Dred Scott v. Sanford (1857), Abraham Lincoln commented that the principle of equality in the Declaration of Independence was “meant to set up a standard maxim [fundamental principle] for a free society.” Indeed, throughout American history, many Americans appealed to the ideals of the Declaration of Independence to make liberty and equality a reality for all.

A constitutional democracy requires vigorous deliberation and debate by citizens and their representatives. Therefore, it should not be surprising that the meanings and implications of the Declaration of Independence and its principles have been debated and contested throughout history. This civil and political dialogue helps Americans understand the principles and ideas upon which their country was founded and the means of working to achieve them.

Applying the Declaration of Independence from the Founding through the Civil War

Individuals appealed [pointed to as evidence] to the principles of the Declaration of Independence soon after it was signed. In the 1770s and 1780s, enslaved people in New England appealed to the natural rights principles of the Declaration and state constitutions as they petitioned legislatures and courts for freedom and the abolition of slavery. A group of enslaved people in New Hampshire stated, “That the God of Nature, gave them, Life, and Freedom, upon the Terms of the most perfect Equality with other men; That Freedom is an inherent [of a permanent quality] Right of the human Species, not to be surrendered, but by Consent.” While some of these petitions were unsuccessful, others led to freedom for the petitioner.

The women and men who assembled at the 1848 Seneca Falls Convention , the first women’s rights conference held in the United States, adopted the Declaration of Sentiments and Resolutions , a list of injustices committed against women. The document was modeled after the Declaration of Independence, but the language was changed to read, “We hold these truths to be self-evident : [clear without having to be stated] that all men and women are created equal.” It then listed several grievances regarding the inequalities that women faced. The document served as a guiding star in the long struggle for women’s suffrage.

The Declaration of Independence was one of the centerpieces of the national debate over slavery. Abolitionists such as Frederick Douglass, William Lloyd Garrison, and Abby Kelley all invoked the Declaration of Independence in denouncing slavery. On the other hand, Senators Stephen Douglas and John Calhoun, Justice Roger Taney, and Confederate Vice President Alexander Stephens all denied that the Declaration of Independence was meant to apply to Black people.

Abraham Lincoln was president during the crisis of the Civil War, which was brought about by this national debate over slavery. He consistently held that the Declaration of Independence had universal natural rights principles that were “applicable to all men and all time.” In his Gettysburg Address, Lincoln stated that the nation was “conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.”

The Declaration at Home and Abroad: The Twentieth Century and Beyond

The case of Plessy v. Ferguson (1896) revealed a split over the meaning of the equality principle even in the Supreme Court. The majority in the 7–1 decision thought that distinctions and inequalities based upon race did not violate the Fourteenth Amendment and did not imply inferiority, and therefore, segregation was constitutional. Dissenting Justice John Marshall Harlan argued for equality when he famously wrote, “In the eye of the law, there is in this country no superior, dominant, ruling class of citizens. There is no caste here. Our constitution is colorblind.”

The expansion of American world power in the wake of the Spanish-American War of 1898 triggered another debate inspired by the Declaration of Independence. The war brought the United States into more involvement in world affairs. Echoing earlier debates over Manifest Destiny during nineteenth-century westward expansion, supporters of American global expansion argued that the country would bring the ideals of liberty and self-government to those people who had not previously enjoyed them. On the other hand, anti-imperialists countered that creating an American empire violated the Declaration of Independence by taking away the liberty of self-determination , or freedom of government without foreign interference, and consent from Filipinos and Cubans.

Politicians of differing perspectives viewed the Declaration in opposing ways during the early twentieth century. Progressives [a political and social reform group that began in the late 19th century] such as Presidents Theodore Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson argued that the principles of the Declaration of Independence were important for an earlier period in American history, to gain independence from Great Britain and to set up the new nation. They argued that the modern United States faced new challenges introduced by an industrial economy and needed a new set of ideas that required a more active government and more powerful national executive. They were less concerned with preserving an ideal of liberty and equality and more concerned with regulating society and the economy for the public interest. Wilson in particular rejected the views of the Founding, criticizing both the Declaration and the Constitution as irrelevant for facing the problems of his time.

President Calvin Coolidge disagreed and adopted a conservative position when he argued that the ideals of the Declaration of Independence should be preserved and respected. On the 150th anniversary of the Declaration, Coolidge stated that the principles formed the American belief system and were still the basis of American republican institutions. They were still applicable regardless of how much society had changed.

During World War II, Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan threatened the free nations of the world with aggressive expansion and domination. The United States and the coalition of Allied powers fought for several years to reverse their conquests. President Franklin Roosevelt and other free-world leaders proclaimed the principles of liberty and self-government from the Declaration of Independence in documents such as the Atlantic Charter , the Four Freedoms speech, and the United Nations Charter.

After World War II, American social movements for justice and equality called upon the Declaration of Independence and its principles. For example, in his “I Have a Dream” speech, Martin Luther King, Jr., referred to the Declaration as the “sacred heritage” of the nation but said that it had not lived up to its ideals for Black Americans. King demanded that the United States live up to its “sacred obligation” of liberty and equality for all.

The natural rights republican ideals of the Declaration of Independence influenced the creation of American constitutional government founded upon liberty and equality. They also shaped the expectation that a free people would live in a just society. Indeed, the Declaration states that to secure natural rights is the fundamental duty of government. Achieving those ideals has always been part of a robust and dynamic debate among the sovereign people and their representatives.

Inspired by the ideals of the Declaration of Independence, many social movements, politicians, and individuals helped make the United States a more equal and just society. The Emancipation Proclamation ; the Thirteenth , Fourteenth , and Fifteenth Amendments ; the Nineteenth Amendment ; the 1964 Civil Rights Act ; and the 1965 Voting Rights Act were only some of the achievements in the name of equality and justice. As James Madison wrote in Federalist 51 , “Justice is the end of government. It is the end of civil society. It ever has been and ever will be pursued until it be obtained.”

Related Content

Graphic Organizer: The Declaration of Independence and Equality in U.S. History

Documents: The Declaration of Independence and Equality in U.S. History

The Guiding Star of Equality: The Declaration of Independence and Equality in U.S. History Answer Key

Search form

- Find Stories

- For Journalists

When Thomas Jefferson penned ‘all men are created equal,’ he did not mean individual equality, says Stanford scholar

When the Continental Congress adopted the Declaration of Independence on July 4, 1776, it was a call for the right to statehood rather than individual liberties, says Stanford historian Jack Rakove. Only after the American Revolution did people interpret it as a promise for individual equality.

In the decades following the Declaration of Independence, Americans began reading the affirmation that “all men are created equal” in different ways than the framers intended, says Stanford historian Jack Rakove .

With each generation, the words expressed in the Declaration of Independence have expanded beyond what the founding fathers originally intended when they adopted the historic document on July 4, 1776, says Stanford historian Jack Rakove. (Image credit: Getty Images)

On July 4, 1776, when the Continental Congress adopted the historic text drafted by Thomas Jefferson, they did not intend it to mean individual equality. Rather, what they declared was that American colonists, as a people , had the same rights to self-government as other nations. Because they possessed this fundamental right, Rakove said, they could establish new governments within each of the states and collectively assume their “separate and equal station” with other nations. It was only in the decades after the American Revolutionary War that the phrase acquired its compelling reputation as a statement of individual equality.

Here, Rakove reflects on this history and how now, in a time of heightened scrutiny of the country’s founders and the legacy of slavery and racial injustices they perpetuated, Americans can better understand the limitations and failings of their past governments.

Rakove is the William Robertson Coe Professor of History and American Studies and professor of political science, emeritus, in the School of Humanities and Sciences. His book, Original Meanings: Politics and Ideas in the Making of the Constitution (1996), won the Pulitzer Prize in History. His new book, Beyond Belief, Beyond Conscience: The Radical Significance of the Free Exercise of Religion will be published next month.

With the U.S. confronting its history of systemic racism, are there any problems that Americans are reckoning with today that can be traced back to the Declaration of Independence and the U.S. Constitution?

I view the Declaration as a point of departure and a promise, and the Constitution as a set of commitments that had lasting consequences – some troubling, others transformative. The Declaration, in its remarkable concision, gives us self-evident truths that form the premises of the right to revolution and the capacity to create new governments resting on popular consent. The original Constitution, by contrast, involved a set of political commitments that recognized the legal status of slavery within the states and made the federal government partially responsible for upholding “the peculiar institution.” As my late colleague Don Fehrenbacher argued, the Constitution was deeply implicated in establishing “a slaveholders’ republic” that protected slavery in complex ways down to 1861.

But the Reconstruction amendments of 1865-1870 marked a second constitutional founding that rested on other premises. Together they made a broader definition of equality part of the constitutional order, and they gave the national government an effective basis for challenging racial inequalities within the states. It sadly took far too long for the Second Reconstruction of the 1960s to implement that commitment, but when it did, it was a fulfillment of the original vision of the 1860s.

As people critically examine the country’s founding history, what might they be surprised to learn from your research that can inform their understanding of American history today?

Two things. First, the toughest question we face in thinking about the nation’s founding pivots on whether the slaveholding South should have been part of it or not. If you think it should have been, it is difficult to imagine how the framers of the Constitution could have attained that end without making some set of “compromises” accepting the legal existence of slavery. When we discuss the Constitutional Convention, we often praise the compromise giving each state an equal vote in the Senate and condemn the Three Fifths Clause allowing the southern states to count their slaves for purposes of political representation. But where the quarrel between large and small states had nothing to do with the lasting interests of citizens – you never vote on the basis of the size of the state in which you live – slavery was a real and persisting interest that one had to accommodate for the Union to survive.

Second, the greatest tragedy of American constitutional history was not the failure of the framers to eliminate slavery in 1787. That option was simply not available to them. The real tragedy was the failure of Reconstruction and the ensuing emergence of Jim Crow segregation in the late 19th century that took many decades to overturn. That was the great constitutional opportunity that Americans failed to grasp, perhaps because four years of Civil War and a decade of the military occupation of the South simply exhausted Northern public opinion. Even now, if you look at issues of voter suppression, we are still wrestling with its consequences.

You argue that in the decades after the Declaration of Independence, Americans began understanding the Declaration of Independence’s affirmation that “all men are created equal” in a different way than the framers intended. How did the founding fathers view equality? And how did these diverging interpretations emerge?

When Jefferson wrote “all men are created equal” in the preamble to the Declaration, he was not talking about individual equality. What he really meant was that the American colonists, as a people , had the same rights of self-government as other peoples, and hence could declare independence, create new governments and assume their “separate and equal station” among other nations. But after the Revolution succeeded, Americans began reading that famous phrase another way. It now became a statement of individual equality that everyone and every member of a deprived group could claim for himself or herself. With each passing generation, our notion of who that statement covers has expanded. It is that promise of equality that has always defined our constitutional creed.

Thomas Jefferson drafted a passage in the Declaration, later struck out by Congress, that blamed the British monarchy for imposing slavery on unwilling American colonists, describing it as “the cruel war against human nature.” Why was this passage removed?

At different moments, the Virginia colonists had tried to limit the extent of the slave trade, but the British crown had blocked those efforts. But Virginians also knew that their slave system was reproducing itself naturally. They could eliminate the slave trade without eliminating slavery. That was not true in the West Indies or Brazil.

The deeper reason for the deletion of this passage was that the members of the Continental Congress were morally embarrassed about the colonies’ willing involvement in the system of chattel slavery. To make any claim of this nature would open them to charges of rank hypocrisy that were best left unstated.

If the founding fathers, including Thomas Jefferson, thought slavery was morally corrupt, how did they reconcile owning slaves themselves, and how was it still built into American law?

Two arguments offer the bare beginnings of an answer to this complicated question. The first is that the desire to exploit labor was a central feature of most colonizing societies in the Americas, especially those that relied on the exportation of valuable commodities like sugar, tobacco, rice and (much later) cotton. Cheap labor in large quantities was the critical factor that made these commodities profitable, and planters did not care who provided it – the indigenous population, white indentured servants and eventually African slaves – so long as they were there to be exploited.

To say that this system of exploitation was morally corrupt requires one to identify when moral arguments against slavery began to appear. One also has to recognize that there were two sources of moral opposition to slavery, and they only emerged after 1750. One came from radical Protestant sects like the Quakers and Baptists, who came to perceive that the exploitation of slaves was inherently sinful. The other came from the revolutionaries who recognized, as Jefferson argued in his Notes on the State of Virginia , that the very act of owning slaves would implant an “unremitting despotism” that would destroy the capacity of slaveowners to act as republican citizens. The moral corruption that Jefferson worried about, in other words, was what would happen to slaveowners who would become victims of their own “boisterous passions.”

But the great problem that Jefferson faced – and which many of his modern critics ignore – is that he could not imagine how black and white peoples could ever coexist as free citizens in one republic. There was, he argued in Query XIV of his Notes , already too much foul history dividing these peoples. And worse still, Jefferson hypothesized, in proto-racist terms, that the differences between the peoples would also doom this relationship. He thought that African Americans should be freed – but colonized elsewhere. This is the aspect of Jefferson’s thinking that we find so distressing and depressing, for obvious reasons. Yet we also have to recognize that he was trying to grapple, I think sincerely, with a real problem.

No historical account of the origins of American slavery would ever satisfy our moral conscience today, but as I have repeatedly tried to explain to my Stanford students, the task of thinking historically is not about making moral judgments about people in the past. That’s not hard work if you want to do it, but your condemnation, however justified, will never explain why people in the past acted as they did. That’s our real challenge as historians.

Week 13: The Declaration of Independence

Jeremy Bentham, A Short Review of the Declaration

A short review of the declaration, jeremy bentham.

IN examining this singular Declaration, I have hitherto confined myself to what are given as facts , and alleged against his Majesty and his Parliament, in support of the charge of tyranny and usurpation. Of the preamble I have taken little or no notice. The truth is, little or none does it deserve. The opinions of the modern Americans on Government, like those of their good ancestors on witchcraft, would be too ridiculous to deserve any notice, if like them too, contemptible and extravagant as they be, they had not led to the most serious evils.

In this preamble however it is, that they attempt to establish a theory of Government ; a theory, as absurd and visionary, as the system of conduct in defence of which it is established is nefarious. Here it is, that maxims are advanced in justification of their enterprises against the British Government. To these maxims, adduced for this purpose , it would be sufficient to say, that they are repugnant to the British Constitution . But beyond this they are subversive of every actual or imaginable kind of Government.

They are about “to assume ,” as they tell us, “ among the powers of the earth, that equal and separate ( 120 ) station to which ” — they have lately discovered — “the laws of Nature, and of Nature’s God entitle them .” What difference these acute legislators suppose between the laws of Nature and of Nature’s God , is more than I can take upon me to determine, or even to guess. If to what they now demand they were entitled by any law of God, they had only to produce that law, and all controversy was at an end. Instead of this, what do they produce? What they call sell-evident truths. “ All men ,” they tell us, “are created equal.” This rarity is a new discovery; now, for the first time, we learn, that a child, at the moment of his birth, has the same quantity of natural power as the parent, the same quantity of political power as the magistrate.

The rights of “ life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness ” — by which, if they mean any thing, they must mean the right to enjoy life, to enjoy liberty, and to pursue happiness — they ” hold to be unalienable .” This they “hold to be among truths self-evident .” At the same time, to secure these rights, they are content that Governments should be instituted. They perceive not, or will not seem to perceive, that nothing which can be called Government ever was, or ever could be, in any instance, exercised, but at the expence of one or other of those rights. — That, consequently, in as many instances as Government is ever exercised, some one or other of these rights, pretended to be unalienable, is actually alienated.

That men who are engaged in the design of subverting a lawful Government, should endeavour by a cloud of words, to throw a veil over their design; that they should endeavour to beat down the criteria between tyranny and lawful government, is not at all (121) surprising. But rather surprising it must certainly appear, that they should advance maxims so incompatible with their own present conduct. If the right of enjoying life be unalienable, whence came their invasion of his Majesty’s province of Canada? Whence the unprovoked destruction of so many lives of the inhabitants of that province? If the right of enjoying liberty be unalienable, whence came so many of his Majesty’s peaceable subjects among them, without any offence, without so much as a pretended offence, merely for being suspected not to wish well to their enormities, to be held by them in durance? If the right of pursuing happiness be unalienable, how is it that so many others of their fellow-citizens are by the same injustice and violence made miserable, their fortunes ruined, their persons banished and driven from their friends and families? Or would they have it believed, that there is in their selves some superior sanctity, some peculiar privilege, by which those things are lawful to them, which are unlawful to all the world besides? Or is it, that among acts of coercion, acts by which life or liberty are taken away, and the pursuit of happiness restrained, those only are unlawful, which their delinquency has brought upon them, and which are exercised by regular, long established, accustomed governments?

In these tenets they have outdone the utmost extravagance of all former fanatics. The German Anabaptists indeed went so far as to speak of the right of enjoying life as a right unalienable. To take away life, even in the Magistrate, they held to be unlawful. But they went no farther, it was reserved for an American Congress, to add to the number of unalienable rights, that of enjoying liberty, and pursuing happiness; (122) — that is,— if they mean any thing, —pursuing it wherever a man thinks he can see it, and by whatever means he thinks he can attain it: — That is, that all penal laws — those made by their selves among others—which affect life or liberty, are contrary to the law of God, and the unalienable rights of mankind: — That is, that thieves are not to be restrained from theft, murderers from murder, rebels from rebellion.

Here then they have put the axe to the root of all Government; and yet, in the same breath, they talk of “Governments,” of Governments “long established.” To these last, they attribute same kind of respect; they vouchsafe even to go so far as to admit, that “Governments, long established, should not be “changed for light or transient reasons.”

Yet they are about to change a Government, a Government whose establishment is coeval with their own existence as a Community. What causes do they assign? Circumstances which have always subsisted, which must continue to subsist, wherever Government has subsisted, or can subsist.

For what, according to their own shewing, what was their original their only original grievance ? That they were actually taxed more than they could bear? No; but that they were liable to be so taxed. What is the amount of all the subsequent grievances they alledge? That they were actually oppressed by Government? That Government has actually misused its power? No; but that it was possible that they might be oppressed; possible that Government might misuse its powers. Is there any where, can there be imagined any where, that Government, where subjects are not liable to taxed more than they can bear? (123) where it is not possible that subjects may be oppressed, not possible that Government may misuse its powers?

This I say, is the amount, the whole sum and substance of all their grievances. For in taking a general review of the charges brought against his Majesty, and his Parliament, we may observe that there is a studied confusion in the arrangement of them. It may therefore be worth while to reduce them to the several distinct heads, under which I should have classed them at the first, had not the order of the Answer been necessarily prescribed by the order — or rather the disorder, of the Declaration.

The first head consists of Acts of Government, charged as so many acts of incroachment , so many usurpations upon the present King and his Parliaments exclusively, which had been constantly exercised by his Predecessors and their Parliaments. 1

In all the articles comprised in this head, is there a single power alleged to have been exercised during the present reign, which had not been constantly exercised by preceding Kings, and preceding Parliaments? Read only the commission and instruction for the Council of Trade, drawn up in the 9th of King William III addressed to Mr. Locke, and others. 2 See there what (124) powers were exercised by the King and Parliament over the Colonies. Certainly the Commissioners were directed to inquire into, and make their reports concerning those matters only, in which the King and Parliament had a power of controlling the Colonies. Now the Commissioners are instructed to inquire — into the condition of the Plantations, “as well with regard to the administration of Government and Justice , as in relation to the commerce thereof;”–into the means of making “them most beneficial and useful to England ; — “ into the staples and manufactures, which may be encouraged there ;” — “ into the trades that are taken up and exercised there, which may prove prejudicial to England; ” — “into the means of diverting them from such trades .” Farther, they are instructed “ to examine into, and weigh the Acts of the Assemblies of the Plantations;” — “ to set down the usefulness or mischief to the Crown, to the Kingdom, or to the Plantations their selves .” — And farther still, they are instructed “to require an account of all the monies given for public uses by the assemblies of the Plantations, and how the same are, or have been expended, or laid out.” Is there now a single Act of the present reign which does not fall under one or other of these instructions?

The powers then, of which the several articles now before us complain, are supported by usage; were conceived to be so supported then , just after the Revolution, at the time these instructions were given; and were they to be supported only upon this foot of usage, still that usage being coeval with the Colonies, their tacit consent and approbation, through all the successive periods in which that usage has prevailed, would be implied; — even then the legality of those powers would stand upon the same foot as most of the prerogatives (125) of the Crown, most of the rights of the people, — even then the exercise of those powers could in no wise be deemed usurpations or encroachments.

But the truth is, to the exercise of these powers, on many occasions the Colonies have not tacitly, but expressly , consented; as expressly as any subject of Great Britain ever consented to Acts of the British Parliament. Consult the Journals of either House of Parliament; consult the proceedings of their own Assemblies; and innumerable will be the occasions, on which the legality of these powers will be found to be expressly recognised by Acts of the Colonial Assemblies. For in preceding reigns, the petitions from these Assemblies were couched in a language, very different from that which they have assumed under the present reign. In praying for the non-exercise of these powers, in particular instances, they acknowledged their legality; the right in general was recognised; the exercise of it, in particular instances, was prayed to be suspended on the sole ground of inexpedience .