St Andrews Research Repository

- St Andrews Research Repository

- Divinity (School of)

- Divinity Theses

- Register / Login

The New Jerusalem in the Book of Revelation : a study of Revelation 21-22 in the light of its background in Jewish tradition

Collections

Items in the St Andrews Research Repository are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved, unless otherwise indicated.

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Emotions

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Acquisition

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Religion

- Music and Culture

- Music and Media

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Oncology

- Medical Toxicology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Ethics

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Cognitive Psychology

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Strategy

- Business History

- Business Ethics

- Business and Government

- Business and Technology

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic Systems

- Economic Methodology

- Economic History

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Theory

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Politics and Law

- Public Administration

- Public Policy

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

32 Narrative Technique in the Book of Revelation

David L. Barr is Emeritus Professor of Religion and former chair of the Departments of Religion, Philosophy, and Classics at Wright State University in Dayton, Ohio. His primary research areas include Jewish and Christian apocalypticism, the book of Revelation, and stories as told in the New Testament writings. He is author of Tales of the End: A Narrative Commentary on the Book of Revelation (2012) and New Testament Story: An Introduction (2009), and editor of Reading the Book of Revelation: A Resource for Students (2003) and The Reality of Apocalypse: Rhetoric and Politics in the Book of Revelation (2006).

- Published: 07 April 2015

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

The book of Revelation is neither a guide to the end of the world nor a handbook of theology. It is a narrative in which John recounts what happened to him on Patmos, describes what he saw and heard when he ascended into the sky/heaven, and recounts the cosmic conflict between the forces of good and evil—an ultimate Holy War. It is thus a complicated narrative, recounting both John’s actions (what happened to him) and the actions he recounts in the stories he tells (what he saw and heard). He functions as both the narrator and as a character in the story. This article explores various techniques used to tell the story, including its genre, structure and plot, temporal and spatial distortions, narrative performance and characterizations, and narrative rhetoric.

Too often, the book of Revelation has been read as an allegory wherein various elements of the story are taken to refer to other, external events, especially events of the interpreter’s time. Most often these interpreters claim to be taking the story of Revelation literally, but that is clearly not the case. The story itself says nothing about the modern world, America, the second coming, or the end of the world. It is, rather, a narrative of what happened to John—what he saw and heard—a story, not a puzzle or an essay on the end times. Even scholars have tended to interpret Revelation as an allegory of ideas rather than as a narrative, and so they speak of John’s ecclesiology or his eschatology ( Wainwright 1993 , 125–158). But the book of Revelation is neither a guide to the end of the world nor a handbook of theology. It is a narrative.

In this narrative John recounts what happened to him on Patmos, describes what he saw and heard when he ascended into the sky/heaven, and recounts the cosmic conflict between the forces of good and evil—a definitive Holy War. It is thus a complicated narrative, recounting both John’s actions (what happened to him) and the actions he recounts in the stories he tells (what he saw and heard). He functions as both the narrator and as a character in the story. This chapter explores the various techniques used to tell the story, focusing on its genre, structure and plot, temporal and spatial distortions, performance, and rhetorical effect.

Narrative Genre

The book of Revelation belongs to a genre modern scholars have named apocalypses , minimally described as autobiographical narratives recounting the reception of revelations. These represent a subset of a larger category we can label vision reports . The genre includes a diverse literary corpus, exhibiting different ideologies, addressing different social situations, and employing different narrative strategies. The modern effort to define the genre began in the nineteenth century ( Lücke 1852 ), and was carried forward in significant ways by Russell (1964) , Hanson (1979) , and Hellholm (1989) . Their insights have been analyzed, refined, and advanced in the work of the Society of Biblical Literature’s Genre Project, especially as articulated in the writings of John Collins (1979) . What is now the standard definition runs as follows:

“Apocalypse” is a genre of revelatory literature with a narrative framework, in which a revelation is mediated by an otherworldly being to a human recipient, disclosing a transcendent reality which is both temporal, insofar as it envisages eschatological salvation, and spatial insofar as it involves another, supernatural world. ( Collins 1979 , 9)

In the first instance, every apocalypse is an account of an experience (real or imagined) of some prophetic figure (real or imagined). They typically begin with such statements as “after this I saw another dream and I will show it all to you” (1 Enoch 85:1); “the fourth vision which I saw, brethren, 20 days after the former vision … I was going into the country on the via Campania” ( Shepherd of Hermas 1:1); and “I saw in my sleep what I now show to you with the tongue of flesh and with my breath” (1 Enoch 14:2). John, too, begins autobiographically: he is telling what he heard and saw in the spirit when he was on the island called Patmos (Rev. 1: 9–12).

In this way, an apocalypse is a narrative re-presentation of a revelation experience so that the audience can imaginatively share that experience ( Aune 1986 ). These narratives recount the experience of the seer in another (sacred) time or another (sacred) place. While all apocalypses concern both sacred space and sacred time, an individual apocalypse will focus on one or the other. Those that focus on sacred space usually include an otherworldly journey in which the seer visits the heavens (and later, also the underworld). Those that focus on sacred time usually include the device of historical review, also called ex eventu prophecy, a symbolic portrayal of historical events up to the time of the audience ( Barr 2013 ).

Both types intend to interpret the present situation of the audience. Indeed, those who enter into these stories will find the present situation changed by the experience. Now, this is not something magical or even religious. It is what stories do.

A story on the page is like a printed circuit For our lives to flow through, A story told invokes our dim capacity To be alive in bodies not our own. ( Doctorow 2000 , 181)

In the same way, John pronounces a blessing on those who hear and retain his story (Rev. 1:3). The effectiveness of an apocalypse does not depend on whether it corresponds to history or successfully predicts the future. It depends on whether the story captures the audience. Again, this is what stories do.

“There is nothing better than imagining other worlds,” he said, “to forget the painful one we live in. At least I thought so then. I hadn’t yet realized that, imagining other worlds, you end up changing this one.” ( Eco 2002 , 99)

Stories can change the world, because one of the primary ways we understand the world is by telling stories about it. In John’s world the dominant story was that of Rome and Caesar: the Pax Romana. Caesar had slain the monster of chaos with its civil wars and economic turmoil. John retells the story from the opposite perspective: the chaos monster is the Caesar ( Wengst 1987 ; van Henten 2006 ). And this is not just some general story about a primordial time or a faraway place, for John includes himself and his audience in the story. It is the audience that must keep its hands unsullied and its forehead unmarked by the beast (Rev. 13:16–17; 20:4).

It is the experience of the story of the Apocalypse, with its reconfiguration of the world in which they lived, that allowed the audience to achieve a new understanding of life ( Schüssler Fiorenza 1998a , 181–203). The Apocalypse is both a story and a performance in which the story is orally presented to the audience. John was not so much predicting the coming of a new age as making it a reality in the lives of his audience when they experienced the story of his revelation—“happy are those who hear” (Rev. 1:3; Barr 2006 ).

In this story the hero is Jesus. In fact, the story announces itself as “the Revelation of Jesus Christ” (1:1). But we should not let our familiarity with the gospel versions of that story control our reading of John’s narrative. The story is not told in chronological order, does not follow a consistent action from beginning to end, and contains a high degree of repetition.

Narrative Order

There is no agreement on the proper outline or structure of the book of Revelation. It is often said that there are as many outlines as there are interpreters ( Smith 1994 ). There are several reasons for this diversity. While some of the material is consciously numbered into a series of seven items (churches, seals, trumpets, and bowls), it is not clear how the rest of the material relates to the numbered sequences. There are also interruptions within the numbered sequences—the series of seals is interrupted after seal six with the story of the sealing of God’s servants; the series of trumpets is interrupted after trumpet six with several small stories. The complexity of the traditions recounted is an additional factor; these traditions seem to come from basically different spheres and to be about different things. Some take this as evidence of different sources being combined together. In addition, certain elements of the narrative are repeated again and again. Finally, some of the material seems to be wildly out of place chronologically (for example, the beast is introduced in chapter 13 but has appeared already in the story in chapter 11 ).

The difficulty in finding an outline for Revelation stems in part from asking the wrong question—the question of how to divide the material. We should rather be asking how the author took such diverse material and wove it into a narrative unity ( Thompson 1989 ). If we take the implied setting seriously, that it was composed for an oral performance before an audience (1:3), our attention shifts to how this diverse material is unified ( Barr 1986 ). The author’s hand can be traced in the themes, characterizations, and story plot.

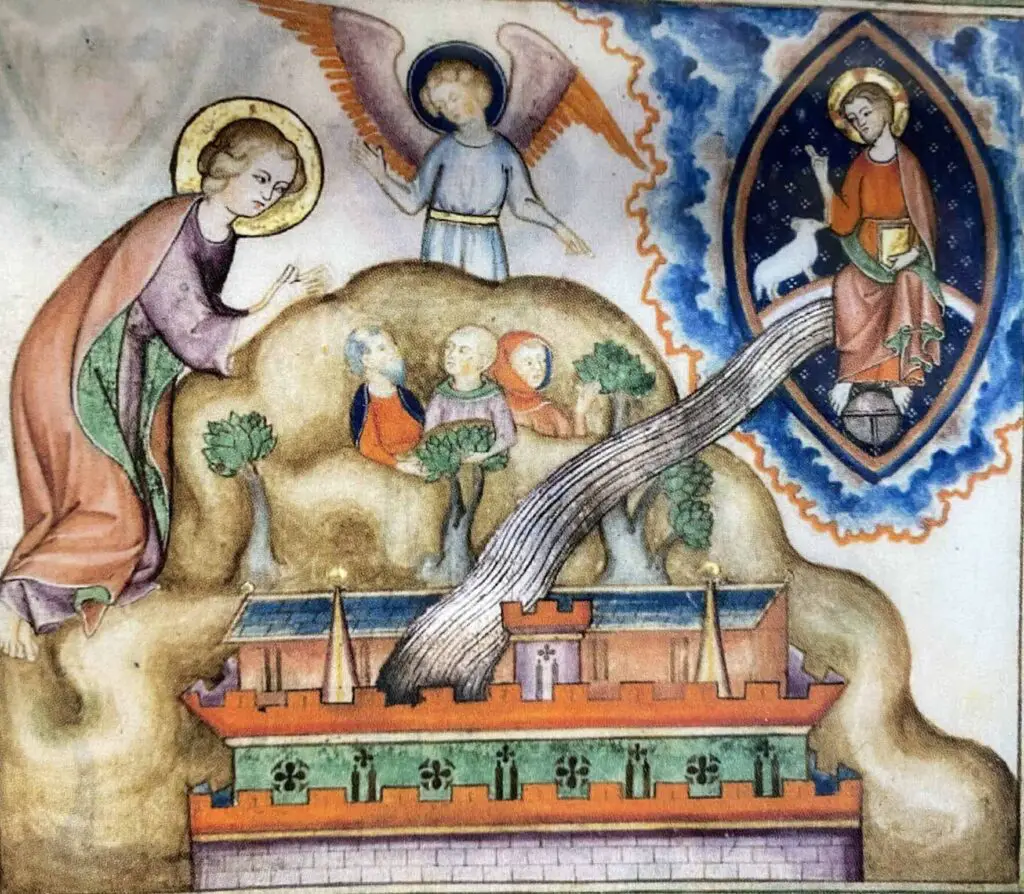

All interpreters agree that chapters 1 through 3 form a discrete unit, the theme of which is a written communication from an otherworldly being. In this unit Jesus is presented as a magnificent heavenly, humanlike figure. The only action of this unit is the instruction to John to write specific letters to the messengers of specific churches. Having completed this task, John is whisked away to heaven, where he witnesses the eternal liturgy of all creation gathered around the throne of God. In this scene Jesus is presented as the slain but living lamb who is worthy to share the throne of God. The action of this unit centers on a scroll which the Lamb opens, moving from the chaos of war, famine, and death (6:1-8) to the declaration that the kingdoms of this world have become the kingdom of God (11:15). After this, John peers into the heavenly Temple and sees astrological and mythological signs of the final battle between good and evil. In this unit Jesus is (or should be) presented as the ultimate heavenly warrior (19:11–16), but in large measure the characterization of the second unit (the slain but living lamb) persists. Still, the theme of holy war permeates all the action of the section, culminating one thousand years of peace, the creation of a new heaven and a new earth, and the manifestation of a new city of God.

We have, then, three broad thematic units having to do with letter writing (1–3), heavenly worship (4–11), and holy war (12–22). Each of these contains some dissimilar materials, and none of them makes conscious reference to the others. John forces the audience to make sense of them by placing them in a common narrative framework of his experience.

John appears in each of the thematic units just described, but with different functions. In the first unit he is a secretary for the heavenly figure; in the second unit he is a heavenly traveler; and in the third unit he is a prophetic seer.

Narrative Space

While John’s actions include the ordinary space of the audience—real places like Ephesus, Smyrna, and Pergamum—the action occurs in other places. The first action occurs on Patmos, an island off the coast of Asia Minor. It is a real and easily imagined place but as an island is not contiguous with ordinary space. It is in some ways Other. Having secured the readers’ imagination of this other place, John now sees a door in the sky and ascends though it into the throne room in heaven—a sacred space radically distinct from ordinary space—and yet, connected to the audience by the portrayal of a worship service, almost certainly analogous to theirs. As the worship service culminates John sees into the heavenly Temple and experiences a further vision. The narrative complexity here is marvelous: the audience sees John on Patmos, having a vision of himself in which he ascends into heaven, where he has a vision of himself having a further vision of the dragon’s coming attack.

Spatial location of this third section is not easy to determine. John sees a vision of omens in the sky (12:1), which would imply that he is back on earth, looking up. This would seem to be confirmed by the account of the war in heaven, at the end of which Satan is cast down to earth (12:12). And the Lamb gathers his army on Mount Zion, an earthly place projecting into the sky above (14:1). Mt. Zion is also a symbolic way of referring to Jerusalem, a place that is both historic and mythic; another battle has the armies gathering at Armageddon—an entirely mythic place not found on any map, despite the ingenuity of many interpreters. And one can hardly imagine where John is standing when he sees the creation of a new heaven and a new earth—the old having fled the scene (21:1).

Still, there is a logic and symmetry to John’s use of space. The story begins and ends with the author on stage as a character in the drama, directly addressing the audience (1:9; 22:8). The opening action occurs on an island in the midst of the sea, and the action ends in a world in which there is no more sea (21:1). And the central action pivots around the throne of God. Thus, the actions reported in these three units occur in identifiable, if ever more remote, locations: on Patmos, in the heavenly throne room, and in the space of conflict located between heaven and earth. Yet the temporal sequence of the action is anything but straightforward.

Narrative Time

The narrative strategy of the book of Revelation distorts the audience’s sense of time in several ways: telling events out of order, describing some actions in great detail while passing quickly over others, and by frequent repetitions with variations. There is little agreement on the meaning of these distortions. At a minimum, we can conclude that there is not one unfolding story in the Apocalypse. At a minimum, we must conclude that events are not told in a chronological order.

The birth of the Messiah is narrated in highly symbolic form in chapter 12 ; but he has already appeared in the story as the slaughtered, yet living, lamb whose conquest has made him worthy to open the scroll in chapter 5 . Chapter 11 culminates in the announcement that the kingdom of God has come and taken control of the kingdoms of this world; yet chapters 13 narrates the emergence of two world beasts whose rule is antithetical to that of God’s. The primeval battle between Michael and Satan, which results in Satan’s expulsion from heaven, is narrated as if it occurs after the death of Jesus (12:7–12). In addition, there are several story fragments inserted into otherwise connected narratives, breaking up the flow. For example, presentation of the seven seals is broken off after the sixth seal by the lengthy recounting of the sealing of the elect for their protection. The series of seven trumpets is broken off after trumpet six with the recounting of three short stories, unconnected to the trumpets. In both instances the story shifts abruptly back to the seventh item in the series. The order in which events are narrated in John’s story is not necessarily related to the order in which he understood them to happen in that story.

All narratives radically compress the time of the story, but within this compression we can recognize three different temporal shifts: summary (when events are narrated briefly), scenic (when events are narrated in detail), and slow motion (when the events narrated are elaborated by descriptions, explanations, or other nonnarrative material). Good examples of the latter include the elaborate description of Jesus in chapter 1 , the detailing of the heavenly throne room chapter 4 , and the descriptions of Babylon as prostitute and of the new Jerusalem as bride in chapters 17 and 21 . In each case, the progress of the narrative is brought to a virtual standstill while the audience contemplates the meaning of the setting.

At the other extreme, some material is passed over in such rapid summary as to be almost invisible. For example, battle scenes are never actually portrayed; the narrative passes directly from the announcement of battle to announcement of its completion (see 19:19–20). Instead of focusing on the battle, the narrative focuses on the one who wins the battle, with an elaborate slow-motion description (19:11–16). By manipulating the duration of his narration, John directs the audience’s attention to the aspects of the story he deems important.

Numerous elements of John story are repeated, usually with variation. It is not always clear whether he is narrating the same event in different words or different events in similar words. Some instances seem to be simple repetitions. There are two scenes of the twenty-four elders worshiping before the heavenly throne (4:10; 11:6), two portrayals of the censer full of the prayers of the faithful (5:8; 8:3), two openings of the heavenly temple (11:19; 15:5), two instances of John offering worship to the heavenly messenger (19:10; 22:8), and several joltings of the great earthquake (6:12; 8:5; 11:13; 11:19).

More important are the repetitions with variation. For example, the seven bowls of judgment echo almost exactly the seven trumpets (compare 8:7–11:15 with 16:2–17). And while it is common to speak of the final battle in the book of Revelation, there are in fact five such battles (16:14; 17:14; 19:11, 19:19; 20:8). In a similar way, the fall of Babylon—that great enemy of God—is noted six times: as burned (14:8–11), destroyed by an earthquake (16:18–21), as consumed by the kings of the earth (17:16–18), as abandoned (18:2–4), as burned (18:8–20), and as being thrown into the sea (18:21–24). It seems impossible to take these as any kind of a chronological sequence.

John’s narrative technique thus involves deliberate temporal distortions of order, duration, and frequency. It operates under different time schemes in different parts. And even the characters that persist throughout the narrative (John and Jesus) are characterized differently in different actions. Is it possible, then, to speak of the plot of John’s narrative?

Narrative Plot

Some see the work as a continuously unfolding plot (a linear sequence; Resseguie 2009 , 44–47); others see it as is lacking a plot altogether—preferring to speak of its “dramatic structure” ( Bowman 1955 ) or mythic unity ( Thompson 1969 ). Still others see it as a collection of stories within an overarching narrative structure (more circular or spiral than straight line; Barr 2003 ).

These different perspectives derive in part from different understandings of plot. Some regard plot as the arrangement of the incidents of the story so that they achieve a particular impression on the reader. Such critics usually look for broad categories of action, such as the setting, the problem, the crisis, the resolution, and the new setting (for example, Jang 2003 ). At this very broad level of generalization one can argue that chapters 1–3 provide the setting of the story, a story that begins in heavenly unity (4–5) but then descends into chaos with the emergence of the Dragon into beasts (12–13); this chaos is overcome in the war between the Lamb and the Dragon (14–19), resulting in a new state of ideal unity (20–22). This might rightly be called a comic plot and is a useful way to view the story of the Apocalypse ( Resseguie 2009 ).

Others, going back to Aristotle, define plot not as the incidents of the story but as the relationship between the incidents, the causality, the logic of the arrangement of the incidents—the probability or necessity that one thing should follow another ( Aristotle 1953 , 1450a, 51). This is what Aristotle meant when he said every story should have a beginning, middle, and end; the initial incident starts the ball rolling; middle incidents receive their impetus from the preceding incidents and pass it on to the next; the final incident brings the movement to a stop. Of course, Aristotle was talking about the relatively tightly plotted genre of Greek tragedy. Actual plots vary over a broad continuum from the very tightly plotted (such as a tragedy) to the very loosely plotted (such as an epic).

Using this definition, it is impossible to draw a straight line through the apocalypse wherein each incident is related to that which goes before and after. There are just too many incidents, too many different kinds of incidents, too many loose ends. A prime example is the opening section in which John is directed to write letters to the seven churches; the audience sees the dictation of the letters, but they are never delivered. We never get to see what Jezebel says when she reads what John says of her! In fact the letters are never referred to again. Instead, John plays on the reference to the heavenly throne in the seventh letter and then proceeds to describe a vision of the throne of God with all creation gathered round—an entirely new action.

The throne scene centers on opening another scroll, one sealed with seven seals. Its opening culminates in silence, the blowing of seven trumpets, and the announcement that God’s kingdom has come: “the kingdom of this world has become the kingdom of our Lord and of his Messiah and he shall reign forever and ever” (11:15). Heavenly worship resumes. On one level, this represents the end of the story. What could possibly happen after this?

But instead of stopping, the story continues with an essentially new cast of characters: a heavenly woman crowned with the sun and a great red dragon, who now initiates a war on God’s people. The Dragon conjures two other new characters: the primordial beasts from land and sea. Then something surprising happens. In characterizing the forces that will oppose this evil triumvirate, John reaches back to the throne scene, transforming the 144,000 marked for protection into the holy Army led, not by a new hero, but by the slaughtered-standing lamb. By (re)using these characters, John ties this new action to the previous one even though there is no logical connection to the action.

There are, then, three separate thematic and dramatic units in the narrative that John has constructed: a heavenly figure commands John to write letters to the seven churches, dictating the messages. John journeys in the spirit to the heavenly throne room, where he witnesses the heavenly liturgy. John peers into the heavenly Temple and witnesses the holy war between good and evil. Nevertheless, John has used these three stories to create a unified narrative.

The narrative strategy of the book of Revelation entails incorporating these three separate stories within a common narrative framework of John’s revelatory experience. He begins his narrative with the declaration, “I John was on the island called Patmos … and I heard … and turned to see …” (1:9–12) And after telling us his stories he reasserts, “I John am the one who heard and saw these things” (22:8). This corresponds exactly to what the opening narrator declares “the revelation of Jesus Christ, which God gave him to show his servants what must soon take place; he made it known by sending his angel to his servant John, who testified to the word of God and to the testimony of Jesus Christ, even to all that he saw” (1:1–2). And the scene of the angel presenting the revelation to John is dramatized near the midpoint of the narrative (10:1–10).

The motif that holds all this together is the need to conquer evil ( Bauckham 1988 ). In the letters, each of the seven churches is promised a reward to the one who conquers (2:7, 11, 17, 26–28; 3:5, 12, 21), and each promise is eventually fulfilled in the final scenes of the story (see the chart in Barr 2012 , 92–93). And the means of this conquest are revealed in the second story, where the only one worthy to open the divine scroll is the slaughtered Lamb “who has conquered” (5:1–10). While other early writers explained Jesus’s conquest in historical terms (the Gospels), John has chosen a thoroughly mythic form. The third scene portrays the actual conquest of the Lamb over the Dragon, using the metaphor of holy war. This war is not something that happens after the heavenly liturgy, not some future struggle; it is something that happens in the liturgy and in the prior events, showing how the Lamb conquered.

Narrative Closure

Stories should come to a satisfying conclusion, a final scene or narrator’s summary in which the conflict is resolved and there is no need for any further action—an end: closure. Sometimes this closure is complete, all the loose ends wrapped up, but most often the closure is only partial. But whether partial or complete, the ending of the story enables the audience to understand story in a new way. We now know how it comes out. Looking back, we can now see what was important and what was not. The ending offers the audience the final clue to the story’s meaning; now the audience must exercise its imagination.

The end of John’s story has been a long time coming ( Barr 2001 ). And when it does come it is not what we expect. It can be read in at least three ways, considering the story of the narrator, of the characters in the story, and of the implied audience.

From the viewpoint of the narrator, nothing has changed. Our circling plot eventually comes back to where it began, with John directly addressing the audience in his own voice, “I, John, am the one who heard and saw these things” (22:8; cf. 1:9). In this way, nothing has changed. The anticipated time is still near (22:10; cf. 1:3), and Jesus is still coming soon (22:12; cf. 1:1). The dogs are still outside (22:15).

But from the viewpoint of the characters in the story, everything has changed. The city of God has descended from heaven, bringing the tree of life to all (22:2), and “there shall be no curse anymore” (22:3). The failure of Eden has been undone by the one who conquers. The world has changed. To the degree that the audience identifies with these characters, their world, too, may be changed. For closure is not complete; there is more, more to the story, for at the very end of the story something is happening. The audience is invited to come and drink of the water of life; and Jesus promises to come to them. Some further action is contemplated. We do not know what it is, for it happens outside the story—we do not even know if those gathered to hear the story (the narratee) will come. But we do know there is more to the story. The end is not necessarily the end.

Narrative Rhetoric

Things heard, things seen, things told. The overarching story of Revelation is the narrative of how John experienced three increasingly fantastic stories, located in increasingly fantastic places. What John sees and hears in these places is meant to persuade those in his community to live appropriately in their present political and social situation. Just what that situation was is not entirely clear. What is clear is that we must not mistake the narrative setting for the actual setting. Narratives present the world as the author wishes us to see it, not simply the world as it is ( Krieger 1964 ; Petersen 1978 ).

The narrative world of the Apocalypse is a dangerous place, full of beasts and dragons. For a long time interpreters assumed that this was also true of John’s historical world, assumed that John lived in a time of Roman persecution of Christians. But careful historical research has shown that this is not likely. Late first-century Roman Asia minor was a time and place of increasing prosperity ( Thompson 1990 ).

On the other hand, for rhetoric to be effective, the audience must discern some true connection between elements of the story and their own life experience. The experience must be such that the story is seen as a “fitting response” to their world ( Schüssler Fiorenza 1986 , 1987 , 1998b ). Disentangling the narrative world, the rhetorical world, and the actual historical world is an exceedingly complicated task.

For example, in John’s narrative world there is a notorious woman prophet named Jezebel living at Thyatira (2:20), and there is a “synagogue of Satan” at Smyrna (2:9)—neither of these existed in the actual historical world. Yet there must have been some prophet whose opposition to John was well enough known that the audience could say “you know who he is talking about, don’t you?” And there must have been a synagogue of some sort whose vision of the world was so opposite of John’s that he regarded it as Satanic. The point is, John refracts the life world of the audience in such a way as to persuade his audience that they ought to live in a certain way ( Barr 2011 ).

Serious analysis of the narrative rhetoric of John’s Apocalypse has only just begun ( DeSilva 2009 ). John was determined to persuade his audience that Rome was evil, including its manifestations in culture and commerce. They would not have needed such persuasion if Rome had been actively persecuting them; it would have been obvious. The problem seems to be the opposite: Roman culture was all too attractive to John’s audience. The rhetoric of John’s narrative demonstrates the folly of such thinking.

The book of Revelation is not an allegory of supposed future events, nor is it a symbolic portrayal of theological ideas. It is, instead, an autobiographical narrative of John’s experience of a revelation while “in the Spirit” on the island Patmos. As he tells the tale, he encounters Jesus as a majestic human figure with messages to the seven assemblies of Asia Minor, then as a slaughtered, standing lamb worthy to open a sealed scroll, and, finally, as a heavenly warrior victorious over the forces of evil.

It is a tale artfully told in the genre of a vision report, distorting the audiences’ sense of time and place, engaging them in both the oral presentation of the story and in some subsequent ritual action. By sharing John’s story, the audience shares his revelation. They become those happy folk who hear and keep John’s words (1:3).

Aristotle. Poetics. 1953 . Loeb. Translated by W. H. Fyfe . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Google Scholar

Google Preview

Aune, David E. 1986 . “ The Apocalypse of John and the Problem of Genre. ” In Early Christian Apocalypticism: Genre and Social Setting , edited by Adela Yarbro Collins . Semeia 36: 65–96.

Barr, David L. 1986 . “ The Apocalypse of John as Oral Enactment. ” Interpretation 40: 243–256.

Barr, David L. 2001 . “Waiting for the End That Never Comes: The Narrative Logic of Johns Story.” In Studies in the Book of Revelation , edited by Steve Moyise , 101–112. Edinburgh: T&T Clark.

Barr, David L. 2003 . “The Story John Told: Reading Revelation for Its Plot.” In Reading the Book of Revelation: A Resource for Students , edited by David L. Barr , 11–23. Atlanta, GA: Society of Biblical Literature.

Barr, David L. 2006 . “Beyond Genre: The Expectations of Apocalypse.” In The Reality of Apocalypse: Rhetoric and Politics in the Book of Revelation , edited by David L. Barr , 71–89. Atlanta, GA: Society of Biblical Literature.

Barr, David L. 2011 . “Idol Meat and Satanic Synagogues: From Imagery to History in John’s Apocalypse.” In Imagery in the Book of Revelation , edited by Michael Labahn and Outi Lehtipu , 1–10. Leuven: Peeters.

Barr, David L. 2012 . Tales of the End: A Narrative Commentary on the Book of Revelation . 2nd ed. Salem, OR: Polebridge Press.

Barr, David L. 2013 . “ John Is Not Daniel: The Ahistorical Apocalypticism of the Apocalypse. ” Perspectives in Religious Studies 40(1): 49–63.

Bauckham, Richard J. 1988 . “ The Book of Revelation as a Christian War Scroll. ” Neotestamentica 22: 17–40.

Bowman, John Wick . 1955 . “ The Revelation to John: Its Dramatic Structure and Message. ” Interpretation: A Journal of Bible and Theology 9: 436–453.

Collins, John J. , ed. 1979 . “ Apocalypse: The Morphology of a Genre. ” Semeia: An Experimental Journal for Biblical Criticism 14: 5-8.

DeSilva, David Arthur . 2009 . Seeing Things John’s Way: The Rhetoric of the Book of Revelation . Louisville, KY: Westminster/John Knox Press.

Doctorow, E. L. 2000 . City of God: A Novel . New York: Random House.

Eco, Umberto . 2002 . Baudolino . Translated by William Weaver . New York: Harcourt.

Hanson, Paul D. 1979 . The Dawn of Apocalyptic: The Historical and Sociological Roots of Jewish Apocalyptic Eschatology . Rev. ed. Philadelphia, PA: Fortress.

Hellholm, David . 1989 . Apocalypticism in the Mediterranean World and Near East: Proceedings of the International Colloquium on Apocalypticism . Uppsala. August 12-17, 1979. 2nd ed. Tübingen: Mohr-Siebeck. Original edition, 1983.

Jang, Young . 2003 . “ Narrative Plot of the Apocalypse. ” Scriptura: International Journal of Bible, Religion, and Theology in Southern Africa 84: 381–390.

Krieger, Murray . 1964 . A Window to Criticism: Shakespeare’s Sonnets and Modern Poetics . Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Lücke, Friedrich . 1852 . Versuch Einer Vollständigen Einleitung in Die Offenbarung Des Johannes Und in Die Apokalyptische Litteratur . Bonn: E. Weber.

Petersen, Norman R. 1978 . Literary Criticism for New Testament Critics . Guides to Biblical Scholarship. Philadelphia, PA: Fortress.

Resseguie, James L. 2009 . The Revelation of John: A Narrative Commentary . Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic.

Russell, D. S. 1964 . The Method and Message of Jewish Apocalyptic: 200 B.C.–100 A.D . Old Testament Library. Philadelphia, PA: Westminster Press.

Schüssler Fiorenza, Elisabeth . 1986 . “ The Followers of the Lamb: Visionary Rhetoric and Socio-Political Situation. ” In E arly Christian Apocalypticism: Genre and Social Setting , edited by Adela Yarbro Collins . Semeia 36: 123–146.

Schüssler Fiorenza, Elisabeth . 1987 . “ Rhetorical Situation and Historical Reconstruction in I Corinthians. ” New Testament Studies 33: 386–403.

Schüssler Fiorenza, Elisabeth . 1998 a. The Book of Revelation: Justice and Judgment . 2nd ed. Minneapolis, MN: Fortress.

Schüssler Fiorenza, Elisabeth . 1998 b. “Visionary Rhetoric and Socio-Political Situation.” In The Book of Revelation: Justice and Judgment , 133–156. Minneapolis, MN: Fortress.

Smith, Christopher R. 1994 . “ The Structure of the Book of Revelation in Light of Apocalyptic Literary Conventions. ” Novum Testamentum 36: 373–393.

Thompson, Leonard L. 1969 . “ Cult and Eschatology in the Apocalypse of John. ” Journal of Religion 49: 330–350.

Thompson, Leonard L. 1989 . “ The Literary Unity of the Book of Revelation. ” Bucknell Review 33: 347–363.

Thompson, Leonard L. 1990 . The Book of Revelation: Apocalypse and Empire . Oxford: Oxford University Press.

van Henten, Jan Willem . 2006 . “Dragon Myth and Imperial Ideology in Revelation 12-13.” In The Reality of Apocalypse: Rhetoric and Politics in the Book of Revelation , edited by David L. Barr , 181–203. Atlanta, GA: Scholars Press.

Wainwright, Arthur . 1993 . Mysterious Apocalypse: Interpreting the Book of Revelation . Nashville, TN: Abingdon Press. Reprinted by Wipf and Stock , 2001.

Wengst, Klaus , ed. 1987 . Pax Romana and the Peace of Jesus Christ . Philadelphia, PA: Fortress.

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

BibleProject Guides

Book of Revelation

Key Information and Helpful Resources

In the opening paragraph, the author identifies himself as John, which could refer to the author of the Gospel and letters of John, or it could be another leader in the early Church. Whichever John it was, he makes it clear in the opening paragraph that this book is a “revelation.” The Greek word used here is apokalypsis , which refers to a type of literature found in the Hebrew Scriptures and in other popular Jewish texts. Jewish apocalypses recounted a prophet’s symbolic visions that revealed God’s heavenly perspective on history so that the present could be viewed in light of history’s final outcome. These texts use symbolic imagery and numbers not to confuse but to communicate. Almost all the imagery is drawn from the Old Testament, and John expects his readers to interpret by looking up the texts to which he alludes.

Revelation 1-11

11:49 • New Testament Overviews

Who Wrote the Book of Revelation?

Though most Christian traditions hold that Revelation (or The Revelation of Jesus to John) was written by the disciple John, his identity is not explicitly mentioned.

The events described in Revelation take place in Asia-minor to seven specific church communities. Revelation was likely composed between 94 and 96 C.E.

Literary Styles

The book of Revelation is a compilation of apocalyptic literature and prose discourse.

- The hope of Jesus’ final return

- Faithfulness to Jesus throughout one's life

- The comfort of Jesus in suffering and persecution

Revelation can be divided into seven parts. Chapters 1-3 introduces John’s vision. Chapters 4-5, 6-8a, 8b-11, 12-16, and 17-20 focus on various visions of John. And chapters 21-22 are a concluding vision of the new heavens and new Earth.

Revelation 1-3: Jesus’ Words to Seven Churches in Asia Minor

John says that this apocalypse is a prophecy. A prophecy is a word from God spoken through a prophet to comfort or challenge God’s people. This apocalyptic prophecy was sent to real people that John knew. The book opens and closes as a circular letter, which was sent to seven churches in the ancient Roman province of Asia. The fact that The Revelation is a letter means that John was specifically addressing these first century churches. While this book has a lot to say to Christians of later generations, its meaning must first be anchored in the historical context of John’s time and place.

John says he was exiled on the island of Patmos, where he saw a vision of the risen Jesus standing among seven burning lights. The image, adapted from Zechariah 4, is a symbol of seven local churches in Asia Minor. Jesus addressed the specific problems facing each church. Some were apathetic due to wealth and affluence, while others were morally compromised. But there were others who remained faithful to Jesus and were suffering harassment and persecution. Jesus warned them that a “tribulation” was upon the churches that would force them to choose between compromise or faithfulness.

By John’s day, the murder of Christians by the Roman emperor Nero had passed, and the persecution by emperor Domitian was likely underway. Jesus calls the churches to faithfulness, by which they will “conquer” and receive a reward in the final marriage of Heaven and Earth. The opening section sets up the main plot tension throughout the book. Will Jesus’ people conquer and inherit the new world that God has in store? And why is faithfulness to Jesus described as “conquering?”

Related Content

Apocalyptic Literature

The Prophets

Podcast Episode

Five Strategies for Reading Revelation

The Jewish Apocalyptic Imagination

Revelation 4-5: Vision of the Heavenly Throne Room and First Judgment

John’s next vision is of God’s heavenly throne room, described with images from many Old Testament prophetic books. Around God are creatures and elders, representing all creation and human nations, who are giving honor and allegiance to the one true God. In God’s hand is a scroll with seven wax seals, symbolizing the scrolls of the Old Testament prophets and Daniel’s visions. Their message was about how God’s Kingdom would come on Earth as in Heaven.

However, no one is qualified to open the scroll until John finally hears of the one who can. It’s “the Lion of the tribe of Judah” and the “Root of David” (Gen. 49:9; Isa. 11:1). These are classic Old Testament descriptions of the messianic King who would bring God’s Kingdom through military conquest. That’s what John hears, but what he sees is not a lion-king but a sacrificed, bloody lamb who is alive again, standing ready to open the scroll.

This symbol of Jesus as the slain lamb is crucially important for understanding the book. John is saying that the Old Testament promise of God’s future Kingdom was inaugurated through the crucified Messiah. Jesus died for his enemies as the true Passover lamb so that others could be redeemed. His death on the cross was his enthronement and his “conquering” of evil. The vision concludes with the lamb alongside the one on the throne, and together they are worshiped as the one, true Creator and redeemer. The slain lamb then begins to open the scroll, a symbol of his divine authority to guide history to its conclusion.

This brings us into the next section of the book with three cycles of sevens: seven seals, seven trumpets, and seven bowls. Each cycle depicts God’s Kingdom and justice coming on Earth as in Heaven. Some people think these three sets of seven divine judgments represent a literal, linear sequence of events that happened in the past or present, or will happen when Jesus returns. Notice, however, that John wove them together. The seven bowls come out of the seventh trumpet and the seventh seal, and the seven trumpets emerge from the seventh seal. They’re like nesting dolls, each seventh containing the next seven. And each series culminates in the final judgment, all with matching conclusions. Because of this, it’s more likely that John is using each set of seven to depict three distinct perspectives of the same period of time after Jesus’ resurrection.

Day of the Lord

Intro to Spiritual Beings

The Messiah

Sacrifice and Atonement

“Why Did Jesus Have To Die?” (A Question Worth Unpacking)

Day of the Lord Q+R

The Blood Cries Out

The Significance of Seven

Revelation 6-8a: Vision of the Lord’s Slain Servants

As the lamb opens the scroll’s first four seals, John sees four symbolic horsemen (an image from Zechariah 1) who symbolize times of war, conquest, famine, and death. The fifth seal depicts the murdered Christian martyrs before God’s heavenly throne. The cry of their innocent blood rises up before God, and they’re told to rest because, sadly, more Christians are going to die. The sixth seal is God’s ultimate response to their cry. He brings the great Day of the Lord described in Isaiah 2 and Joel 2. The people of the earth cry out, “Who is able to stand?!”

At this point, John pauses the action to answer that question. He sees an angel with a signet ring coming to place a mark of protection on God’s servants enduring all this hardship. He then hears the number of those sealed: 144,000. It’s a military census of twelve thousand from each of the twelve tribes of Israel (Numbers 1). Now, the number of this army is what John heard, just like he heard about the conquering lion of Judah. In both cases, what he turned and saw was the surprising fulfillment through Jesus, the slain lamb. John is seeing the messianic army of God’s Kingdom. It’s made up of people from all over the world, fulfilling God’s ancient promise to Abraham. This multiethnic army of the lamb can stand before God because they’ve all been redeemed by his blood. They are called forth to conquer not by killing their enemies but by suffering and bearing witness like the lamb. With this, the seventh and final seal is broken. But before the scroll is opened, the seven warning trumpets emerge, and only then does the Day of the Lord come to bring final justice once and for all.

Blessing and Curse

Martus / Witness

Revelation 8b-11: Visions of Judgment, the Temple, and Two Witnesses

When we come to the seven trumpets, John backs up and retells the story once again, this time with images from the Exodus story. The first five trumpet blasts replay the plagues sent upon Egypt, while the sixth trumpet releases the four horsemen from the first four seals. John then tells us that, despite these plagues, “the nations did not repent,” just like Pharaoh. God’s judgment alone does not bring people to humble themselves before him.

John then pauses the action again. An angel brings John the unsealed scroll that was opened by the lamb. John is now told to eat the scroll and proclaim its message to the nations. Finally, the lamb’s scroll is open, and we discover how God’s Kingdom will ultimately come.

The scroll’s content is spelled out in two symbolic visions. First, John sees God’s temple and the martyrs within it, and he is told to measure and set it apart (it’s an image of protection drawn from Zech. 2:1-5). The outer courts and city, however, are excluded and trampled by the nations. Some think that this refers literally to a destruction of Jerusalem in the past or the future. But it’s more likely that John is using the new temple as a symbol for God’s new covenant people, just like the other apostles did (1 Cor. 3:16; Heb. 3:6; 1 Pet. 2:4-5). The vision shows that while Jesus’ followers may suffer persecution, this external defeat cannot cancel their victory through the lamb.

This idea is elaborated in the scroll’s second vision. God appoints two witnesses as prophetic representatives to the nations. Some think that this refers literally to two prophets who will appear one day. However, John calls these characters “lampstands,” one of his clear symbols for the churches (Rev. 1:20). It’s likely that this vision is about the prophetic role of Jesus’ followers, who like Moses and Elijah, are to call idolatrous nations and rulers to turn to God. Then a horrible beast appears, who conquers the witnesses and kills them (remember Daniel 7). But God brings the witnesses back to life and vindicates them before their persecutors. This results in many among the nations repenting and giving honor to the creator God.

Let’s pause and think about the story so far. God’s warning judgments through the seals and the trumpets did not generate repentance among the nations. Now the lamb’s scroll reveals the strange mission of his army. God’s Kingdom is revealed when the nations see the Church imitating the sacrifice of the lamb and loving their enemies instead of killing them. It’s God’s mercy, shown through the Church, that will move the nations to repentance. After this, the last trumpet sounds, and the nations are shaken as God’s Kingdom comes on Earth as in Heaven.

The message of the scroll is finished, but who was that terrible beast who declared war against God’s people? John turns to this question in the second half of The Revelation.

The Way of the Exile

Angels and Cherubim

Heaven and Earth

Revelation 12-16: Visions of the Dragon, Beasts, 666, and More

After exploring the surprising message of the lamb’s opened scroll, John offers a series of seven visions that he calls “signs” (Rev. 12-15). That word means “symbol,” and these chapters are full of them. The purpose of these visions is to expand further on the message of the lamb’s scroll.

The first sign reveals the cosmic, spiritual battle behind the Roman empire’s persecution of Christians, the ancient conflict that started in Genesis 3:15. The serpent in the garden of Eden, the source of all spiritual evil, is depicted here as a dragon. It attacks a woman and her seed, who represent the Messiah and his people. But the Messiah defeats the dragon through his death and resurrection, casting him to Earth. There, the dragon may inspire hatred and persecution of the Messiah’s people, but God’s people will conquer him by resisting his influence, even if it kills them. John is showing the seven churches that neither Rome nor any other nation or human is the real enemy. There are dark spiritual powers at work that can be conquered only when Jesus’ followers remain faithful and love their enemies.

John’s next vision replays the same conflict, this time with the symbolism of Daniel’s animal visions (Dan. 7-12). John sees two beasts, one representing national military power that conquers through violence. The other beast symbolizes the economic propaganda machine that exalts this power as divine and demands full allegiance from all nations. This is symbolized by taking the mark of the beast and his number 666 on the forehead or hand.

The meaning of this image is found in the Old Testament. The mark is the “anti-Shema.” The Shema is an ancient Jewish prayer of allegiance to God found in Deuteronomy 6:4-8. It was to be written on the Israelites’ foreheads and hands as a symbol of devoting all your thoughts and actions to the one true God. But now the rebellious nations demand their own god-like allegiance.

The number of the beast is also a symbol. John was fluent in both Hebrew and Greek, and his readers knew that Hebrew letters also function as numbers. If you spell the Greek words “Nero Caesar” or “beast” in Hebrew, both amount to 666. John isn’t saying that Nero was the precise fulfillment of this vision; rather, he’s a recent example of the pattern explored in Daniel. Human rulers become beasts when they assign divinity to their power and economic security and demand total allegiance to it. Babylon was the beast of Daniel’s day, followed by Persia, then Greece, and now Rome in John’s day. The pattern stands for any later nation who acts the same.

Standing opposed to the dragon’s beastly nations is another king, the slain lamb and his army, who have given their lives to follow him. From the new Jerusalem, their song goes out to the nations as “the eternal Gospel” (Rev. 14:6). All people are called to repent, worship God, and come out of Babylon. Then John sees a vision of final justice, symbolized by two harvests. One is a good grain harvest where King Jesus gathers up his faithful people. The other is a harvest of wine grapes, representing humanity’s intoxication with evil, which are taken to the wine press and trampled. With these “sign” visions, John places a choice before the seven churches. Will they resist Babylon and follow the Lamb, or will they follow the beast and suffer its defeat?

John then replays a final cycle of seven divine judgments, symbolized as seven bowls. Similar to the Exodus plagues, the bowls do not bring about repentance but the opposite. The people resist and curse God just like Pharaoh. With the sixth bowl, the dragon and beasts gather the nations together to make war against God’s people in a place called Armageddon. This refers to a plain in northern Israel where many battles had been fought against invading nations (Jud. 5:19; 2 Kgs. 23:29). Some think that this image refers literally to a future battle, while others think it’s a metaphor for final judgment. Either way, John has taken these images from Ezekiel 38-39, where God battles Gog, who is of rebellious humanity. And so in the seventh bowl, evil is defeated among the nations once and for all.

Revelation 12-22

The Satan and Demons

Video Series

The Shema Series

Ancient Jewish Meditation Literature

Does God Punish Innocent People?

Revelation 17-20: The Final Battle of Armageddon

Now that John has fully unpacked the message of the lamb’s unsealed scroll, he expands upon three key themes introduced earlier: the fall of Babylon, the final battle to defeat evil, and the arrival of the new Jerusalem. Each one explores the final coming of God’s Kingdom from a different angle.

John is shown a stunning woman who is dressed like a queen but drunk with the blood of the martyrs and all innocent people. She is riding the dragon from the sign visions and is called Babylon the prostitute. All the detailed symbols of this vision were clear to John’s first readers because he was depicting the military and economic power of the Roman empire. But there’s more to it. The vision quotes language and imagery from every Old Testament passage about the downfall of Babylon, Tyre, and Edom (Isa. 13, 23, 34, 47; Jer. 50-51; Ezek. 26-27). He’s showing that Rome is simply the newest version of that old archetype of humanity in rebellion against God. Nations that exalt their own economic and military security to divine status aren’t limited to the past or the future. Babylons will come and go, leading up to the day when Jesus returns to replace them all with his Kingdom.

Up to this point in the book, the Day of the Lord has been depicted as a day of fire, earthquake, or harvest. Here at the conclusion of the book, it is described as a final battle (Rev. 19:11-21, 20:7-15) that results in the vindication of the martyrs (Rev. 20:1-6). John takes us back to the sixth bowl as the nations gather to oppose God. Jesus appears as the great hero, riding a white horse and ready to “conquer” the world’s evil. Notice, however, that he’s covered with blood before the battle even begins (Rev. 19:13). It’s his own. And his only weapon is “the sword of his mouth,” an image adapted from Isaiah 11:4 and 49:2.

John is trying to tell us that Armageddon is not a bloodbath. The same Jesus who shed his blood for his enemies comes proclaiming justice, holding accountable those who refuse to repent of the ruin they’ve caused in God’s good world. The destructive hellfire that they have caused in the world justly becomes their God-appointed destiny.