- Patient Care & Health Information

- Diseases & Conditions

- Type 2 diabetes

Type 2 diabetes is usually diagnosed using the glycated hemoglobin (A1C) test. This blood test indicates your average blood sugar level for the past two to three months. Results are interpreted as follows:

- Below 5.7% is normal.

- 5.7% to 6.4% is diagnosed as prediabetes.

- 6.5% or higher on two separate tests indicates diabetes.

If the A1C test isn't available, or if you have certain conditions that interfere with an A1C test, your health care provider may use the following tests to diagnose diabetes:

Random blood sugar test. Blood sugar values are expressed in milligrams of sugar per deciliter ( mg/dL ) or millimoles of sugar per liter ( mmol/L ) of blood. Regardless of when you last ate, a level of 200 mg/dL (11.1 mmol/L ) or higher suggests diabetes, especially if you also have symptoms of diabetes, such as frequent urination and extreme thirst.

Fasting blood sugar test. A blood sample is taken after you haven't eaten overnight. Results are interpreted as follows:

- Less than 100 mg/dL (5.6 mmol/L ) is considered healthy.

- 100 to 125 mg/dL (5.6 to 6.9 mmol/L ) is diagnosed as prediabetes.

- 126 mg/dL (7 mmol/L ) or higher on two separate tests is diagnosed as diabetes.

Oral glucose tolerance test. This test is less commonly used than the others, except during pregnancy. You'll need to not eat for a certain amount of time and then drink a sugary liquid at your health care provider's office. Blood sugar levels then are tested periodically for two hours. Results are interpreted as follows:

- Less than 140 mg/dL (7.8 mmol/L ) after two hours is considered healthy.

- 140 to 199 mg/dL (7.8 mmol/L and 11.0 mmol/L ) is diagnosed as prediabetes.

- 200 mg/dL (11.1 mmol/L ) or higher after two hours suggests diabetes.

Screening. The American Diabetes Association recommends routine screening with diagnostic tests for type 2 diabetes in all adults age 35 or older and in the following groups:

- People younger than 35 who are overweight or obese and have one or more risk factors associated with diabetes.

- Women who have had gestational diabetes.

- People who have been diagnosed with prediabetes.

- Children who are overweight or obese and who have a family history of type 2 diabetes or other risk factors.

After a diagnosis

If you're diagnosed with diabetes, your health care provider may do other tests to distinguish between type 1 and type 2 diabetes because the two conditions often require different treatments.

Your health care provider will test A1C levels at least two times a year and when there are any changes in treatment. Target A1C goals vary depending on age and other factors. For most people, the American Diabetes Association recommends an A1C level below 7%.

You also receive tests to screen for complications of diabetes and other medical conditions.

More Information

- Glucose tolerance test

Management of type 2 diabetes includes:

- Healthy eating.

- Regular exercise.

- Weight loss.

- Possibly, diabetes medication or insulin therapy.

- Blood sugar monitoring.

These steps make it more likely that blood sugar will stay in a healthy range. And they may help to delay or prevent complications.

Healthy eating

There's no specific diabetes diet. However, it's important to center your diet around:

- A regular schedule for meals and healthy snacks.

- Smaller portion sizes.

- More high-fiber foods, such as fruits, nonstarchy vegetables and whole grains.

- Fewer refined grains, starchy vegetables and sweets.

- Modest servings of low-fat dairy, low-fat meats and fish.

- Healthy cooking oils, such as olive oil or canola oil.

- Fewer calories.

Your health care provider may recommend seeing a registered dietitian, who can help you:

- Identify healthy food choices.

- Plan well-balanced, nutritional meals.

- Develop new habits and address barriers to changing habits.

- Monitor carbohydrate intake to keep your blood sugar levels more stable.

Physical activity

Exercise is important for losing weight or maintaining a healthy weight. It also helps with managing blood sugar. Talk to your health care provider before starting or changing your exercise program to ensure that activities are safe for you.

- Aerobic exercise. Choose an aerobic exercise that you enjoy, such as walking, swimming, biking or running. Adults should aim for 30 minutes or more of moderate aerobic exercise on most days of the week, or at least 150 minutes a week.

- Resistance exercise. Resistance exercise increases your strength, balance and ability to perform activities of daily living more easily. Resistance training includes weightlifting, yoga and calisthenics. Adults living with type 2 diabetes should aim for 2 to 3 sessions of resistance exercise each week.

- Limit inactivity. Breaking up long periods of inactivity, such as sitting at the computer, can help control blood sugar levels. Take a few minutes to stand, walk around or do some light activity every 30 minutes.

Weight loss

Weight loss results in better control of blood sugar levels, cholesterol, triglycerides and blood pressure. If you're overweight, you may begin to see improvements in these factors after losing as little as 5% of your body weight. However, the more weight you lose, the greater the benefit to your health. In some cases, losing up to 15% of body weight may be recommended.

Your health care provider or dietitian can help you set appropriate weight-loss goals and encourage lifestyle changes to help you achieve them.

Monitoring your blood sugar

Your health care provider will advise you on how often to check your blood sugar level to make sure you remain within your target range. You may, for example, need to check it once a day and before or after exercise. If you take insulin, you may need to check your blood sugar multiple times a day.

Monitoring is usually done with a small, at-home device called a blood glucose meter, which measures the amount of sugar in a drop of blood. Keep a record of your measurements to share with your health care team.

Continuous glucose monitoring is an electronic system that records glucose levels every few minutes from a sensor placed under the skin. Information can be transmitted to a mobile device such as a phone, and the system can send alerts when levels are too high or too low.

Diabetes medications

If you can't maintain your target blood sugar level with diet and exercise, your health care provider may prescribe diabetes medications that help lower glucose levels, or your provider may suggest insulin therapy. Medicines for type 2 diabetes include the following.

Metformin (Fortamet, Glumetza, others) is generally the first medicine prescribed for type 2 diabetes. It works mainly by lowering glucose production in the liver and improving the body's sensitivity to insulin so it uses insulin more effectively.

Some people experience B-12 deficiency and may need to take supplements. Other possible side effects, which may improve over time, include:

- Abdominal pain.

Sulfonylureas help the body secrete more insulin. Examples include glyburide (DiaBeta, Glynase), glipizide (Glucotrol XL) and glimepiride (Amaryl). Possible side effects include:

- Low blood sugar.

- Weight gain.

Glinides stimulate the pancreas to secrete more insulin. They're faster acting than sulfonylureas. But their effect in the body is shorter. Examples include repaglinide and nateglinide. Possible side effects include:

Thiazolidinediones make the body's tissues more sensitive to insulin. An example of this medicine is pioglitazone (Actos). Possible side effects include:

- Risk of congestive heart failure.

- Risk of bladder cancer (pioglitazone).

- Risk of bone fractures.

DPP-4 inhibitors help reduce blood sugar levels but tend to have a very modest effect. Examples include sitagliptin (Januvia), saxagliptin (Onglyza) and linagliptin (Tradjenta). Possible side effects include:

- Risk of pancreatitis.

- Joint pain.

GLP-1 receptor agonists are injectable medications that slow digestion and help lower blood sugar levels. Their use is often associated with weight loss, and some may reduce the risk of heart attack and stroke. Examples include exenatide (Byetta, Bydureon Bcise), liraglutide (Saxenda, Victoza) and semaglutide (Rybelsus, Ozempic, Wegovy). Possible side effects include:

SGLT2 inhibitors affect the blood-filtering functions in the kidneys by blocking the return of glucose to the bloodstream. As a result, glucose is removed in the urine. These medicines may reduce the risk of heart attack and stroke in people with a high risk of those conditions. Examples include canagliflozin (Invokana), dapagliflozin (Farxiga) and empagliflozin (Jardiance). Possible side effects include:

- Vaginal yeast infections.

- Urinary tract infections.

- Low blood pressure.

- High cholesterol.

- Risk of gangrene.

- Risk of bone fractures (canagliflozin).

- Risk of amputation (canagliflozin).

Other medicines your health care provider might prescribe in addition to diabetes medications include blood pressure and cholesterol-lowering medicines, as well as low-dose aspirin, to help prevent heart and blood vessel disease.

Insulin therapy

Some people who have type 2 diabetes need insulin therapy. In the past, insulin therapy was used as a last resort, but today it may be prescribed sooner if blood sugar targets aren't met with lifestyle changes and other medicines.

Different types of insulin vary on how quickly they begin to work and how long they have an effect. Long-acting insulin, for example, is designed to work overnight or throughout the day to keep blood sugar levels stable. Short-acting insulin generally is used at mealtime.

Your health care provider will determine what type of insulin is right for you and when you should take it. Your insulin type, dosage and schedule may change depending on how stable your blood sugar levels are. Most types of insulin are taken by injection.

Side effects of insulin include the risk of low blood sugar — a condition called hypoglycemia — diabetic ketoacidosis and high triglycerides.

Weight-loss surgery

Weight-loss surgery changes the shape and function of the digestive system. This surgery may help you lose weight and manage type 2 diabetes and other conditions related to obesity. There are several surgical procedures. All of them help people lose weight by limiting how much food they can eat. Some procedures also limit the amount of nutrients the body can absorb.

Weight-loss surgery is only one part of an overall treatment plan. Treatment also includes diet and nutritional supplement guidelines, exercise and mental health care.

Generally, weight-loss surgery may be an option for adults living with type 2 diabetes who have a body mass index (BMI) of 35 or higher. BMI is a formula that uses weight and height to estimate body fat. Depending on the severity of diabetes or the presence of other medical conditions, surgery may be an option for someone with a BMI lower than 35.

Weight-loss surgery requires a lifelong commitment to lifestyle changes. Long-term side effects may include nutritional deficiencies and osteoporosis.

People living with type 2 diabetes often need to change their treatment plan during pregnancy and follow a diet that controls carbohydrates. Many people need insulin therapy during pregnancy. They also may need to stop other treatments, such as blood pressure medicines.

There is an increased risk during pregnancy of developing a condition that affects the eyes called diabetic retinopathy. In some cases, this condition may get worse during pregnancy. If you are pregnant, visit an ophthalmologist during each trimester of your pregnancy and one year after you give birth. Or as often as your health care provider suggests.

Signs of trouble

Regularly monitoring your blood sugar levels is important to avoid severe complications. Also, be aware of symptoms that may suggest irregular blood sugar levels and the need for immediate care:

High blood sugar. This condition also is called hyperglycemia. Eating certain foods or too much food, being sick, or not taking medications at the right time can cause high blood sugar. Symptoms include:

- Frequent urination.

- Increased thirst.

- Blurred vision.

Hyperglycemic hyperosmolar nonketotic syndrome (HHNS). This life-threatening condition includes a blood sugar reading higher than 600 mg/dL (33.3 mmol/L ). HHNS may be more likely if you have an infection, are not taking medicines as prescribed, or take certain steroids or drugs that cause frequent urination. Symptoms include:

- Extreme thirst.

- Drowsiness.

- Dark urine.

Diabetic ketoacidosis. Diabetic ketoacidosis occurs when a lack of insulin results in the body breaking down fat for fuel rather than sugar. This results in a buildup of acids called ketones in the bloodstream. Triggers of diabetic ketoacidosis include certain illnesses, pregnancy, trauma and medicines — including the diabetes medicines called SGLT2 inhibitors.

The toxicity of the acids made by diabetic ketoacidosis can be life-threatening. In addition to the symptoms of hyperglycemia, such as frequent urination and increased thirst, ketoacidosis may cause:

- Shortness of breath.

- Fruity-smelling breath.

Low blood sugar. If your blood sugar level drops below your target range, it's known as low blood sugar. This condition also is called hypoglycemia. Your blood sugar level can drop for many reasons, including skipping a meal, unintentionally taking more medication than usual or being more physically active than usual. Symptoms include:

- Irritability.

- Heart palpitations.

- Slurred speech.

If you have symptoms of low blood sugar, drink or eat something that will quickly raise your blood sugar level. Examples include fruit juice, glucose tablets, hard candy or another source of sugar. Retest your blood in 15 minutes. If levels are not at your target, eat or drink another source of sugar. Eat a meal after your blood sugar level returns to normal.

If you lose consciousness, you need to be given an emergency injection of glucagon, a hormone that stimulates the release of sugar into the blood.

- Medications for type 2 diabetes

- GLP-1 agonists: Diabetes drugs and weight loss

- Bariatric surgery

- Endoscopic sleeve gastroplasty

- Gastric bypass (Roux-en-Y)

There is a problem with information submitted for this request. Review/update the information highlighted below and resubmit the form.

From Mayo Clinic to your inbox

Sign up for free and stay up to date on research advancements, health tips, current health topics, and expertise on managing health. Click here for an email preview.

Error Email field is required

Error Include a valid email address

To provide you with the most relevant and helpful information, and understand which information is beneficial, we may combine your email and website usage information with other information we have about you. If you are a Mayo Clinic patient, this could include protected health information. If we combine this information with your protected health information, we will treat all of that information as protected health information and will only use or disclose that information as set forth in our notice of privacy practices. You may opt-out of email communications at any time by clicking on the unsubscribe link in the e-mail.

Thank you for subscribing!

You'll soon start receiving the latest Mayo Clinic health information you requested in your inbox.

Sorry something went wrong with your subscription

Please, try again in a couple of minutes

Clinical trials

Explore Mayo Clinic studies testing new treatments, interventions and tests as a means to prevent, detect, treat or manage this condition.

Lifestyle and home remedies

Careful management of type 2 diabetes can reduce the risk of serious — even life-threatening — complications. Consider these tips:

- Commit to managing your diabetes. Learn all you can about type 2 diabetes. Make healthy eating and physical activity part of your daily routine.

- Work with your team. Establish a relationship with a certified diabetes education specialist, and ask your diabetes treatment team for help when you need it.

- Identify yourself. Wear a necklace or bracelet that says you are living with diabetes, especially if you take insulin or other blood sugar-lowering medicine.

- Schedule a yearly physical exam and regular eye exams. Your diabetes checkups aren't meant to replace regular physicals or routine eye exams.

- Keep your vaccinations up to date. High blood sugar can weaken your immune system. Get a flu shot every year. Your health care provider also may recommend the pneumonia vaccine. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) also recommends the hepatitis B vaccination if you haven't previously received this vaccine and you're 19 to 59 years old. Talk to your health care provider about other vaccinations you may need.

- Take care of your teeth. Diabetes may leave you prone to more-serious gum infections. Brush and floss your teeth regularly and schedule recommended dental exams. Contact your dentist right away if your gums bleed or look red or swollen.

- Pay attention to your feet. Wash your feet daily in lukewarm water, dry them gently, especially between the toes, and moisturize them with lotion. Check your feet every day for blisters, cuts, sores, redness and swelling. Contact your health care provider if you have a sore or other foot problem that isn't healing.

- Keep your blood pressure and cholesterol under control. Eating healthy foods and exercising regularly can go a long way toward controlling high blood pressure and cholesterol. Take medication as prescribed.

- If you smoke or use other types of tobacco, ask your health care provider to help you quit. Smoking increases your risk of diabetes complications. Talk to your health care provider about ways to stop using tobacco.

- Use alcohol sparingly. Depending on the type of drink, alcohol may lower or raise blood sugar levels. If you choose to drink alcohol, only do so with a meal. The recommendation is no more than one drink daily for women and no more than two drinks daily for men. Check your blood sugar frequently after drinking alcohol.

- Make healthy sleep a priority. Many people with type 2 diabetes have sleep problems. And not getting enough sleep may make it harder to keep blood sugar levels in a healthy range. If you have trouble sleeping, talk to your health care provider about treatment options.

- Caffeine: Does it affect blood sugar?

Alternative medicine

Many alternative medicine treatments claim to help people living with diabetes. According to the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health, studies haven't provided enough evidence to recommend any alternative therapies for blood sugar management. Research has shown the following results about popular supplements for type 2 diabetes:

- Chromium supplements have been shown to have few or no benefits. Large doses can result in kidney damage, muscle problems and skin reactions.

- Magnesium supplements have shown benefits for blood sugar control in some but not all studies. Side effects include diarrhea and cramping. Very large doses — more than 5,000 mg a day — can be fatal.

- Cinnamon, in some studies, has lowered fasting glucose levels but not A1C levels. Therefore, there's no evidence of overall improved glucose management.

Talk to your health care provider before starting a dietary supplement or natural remedy. Do not replace your prescribed diabetes medicines with alternative medicines.

Coping and support

Type 2 diabetes is a serious disease, and following your diabetes treatment plan takes commitment. To effectively manage diabetes, you may need a good support network.

Anxiety and depression are common in people living with diabetes. Talking to a counselor or therapist may help you cope with the lifestyle changes and stress that come with a type 2 diabetes diagnosis.

Support groups can be good sources of diabetes education, emotional support and helpful information, such as how to find local resources or where to find carbohydrate counts for a favorite restaurant. If you're interested, your health care provider may be able to recommend a group in your area.

You can visit the American Diabetes Association website to check out local activities and support groups for people living with type 2 diabetes. The American Diabetes Association also offers online information and online forums where you can chat with others who are living with diabetes. You also can call the organization at 800-DIABETES ( 800-342-2383 ).

Preparing for your appointment

At your annual wellness visit, your health care provider can screen for diabetes and monitor and treat conditions that increase your risk of diabetes, such as high blood pressure, high cholesterol or a high BMI .

If you are seeing your health care provider because of symptoms that may be related to diabetes, you can prepare for your appointment by being ready to answer the following questions:

- When did your symptoms begin?

- Does anything improve the symptoms or worsen the symptoms?

- What medicines do you take regularly, including dietary supplements and herbal remedies?

- What are your typical daily meals? Do you eat between meals or before bedtime?

- How much alcohol do you drink?

- How much daily exercise do you get?

- Is there a history of diabetes in your family?

If you are diagnosed with diabetes, your health care provider may begin a treatment plan. Or you may be referred to a doctor who specializes in hormonal disorders, called an endocrinologist. Your care team also may include the following specialists:

- Certified diabetes education specialist.

- Foot doctor, also called a podiatrist.

- Doctor who specializes in eye care, called an ophthalmologist.

Talk to your health care provider about referrals to other specialists who may be providing care.

Questions for ongoing appointments

Before any appointment with a member of your treatment team, make sure you know whether there are any restrictions, such as not eating or drinking before taking a test. Questions that you should regularly talk about with your health care provider or other members of the team include:

- How often do I need to monitor my blood sugar, and what is my target range?

- What changes in my diet would help me better manage my blood sugar?

- What is the right dosage for prescribed medications?

- When do I take the medications? Do I take them with food?

- How does management of diabetes affect treatment for other conditions? How can I better coordinate treatments or care?

- When do I need to make a follow-up appointment?

- Under what conditions should I call you or seek emergency care?

- Are there brochures or online sources you recommend?

- Are there resources available if I'm having trouble paying for diabetes supplies?

What to expect from your doctor

Your health care provider is likely to ask you questions at your appointments. Those questions may include:

- Do you understand your treatment plan and feel confident you can follow it?

- How are you coping with diabetes?

- Have you had any low blood sugar?

- Do you know what to do if your blood sugar is too low or too high?

- What's a typical day's diet like?

- Are you exercising? If so, what type of exercise? How often?

- Do you sit for long periods of time?

- What challenges are you experiencing in managing your diabetes?

- Professional Practice Committee: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes — 2020. Diabetes Care. 2020; doi:10.2337/dc20-Sppc.

- Diabetes mellitus. Merck Manual Professional Version. https://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/endocrine-and-metabolic-disorders/diabetes-mellitus-and-disorders-of-carbohydrate-metabolism/diabetes-mellitus-dm. Accessed Dec. 7, 2020.

- Melmed S, et al. Williams Textbook of Endocrinology. 14th ed. Elsevier; 2020. https://www.clinicalkey.com. Accessed Dec. 3, 2020.

- Diabetes overview. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/diabetes/overview/all-content. Accessed Dec. 4, 2020.

- AskMayoExpert. Type 2 diabetes. Mayo Clinic; 2018.

- Feldman M, et al., eds. Surgical and endoscopic treatment of obesity. In: Sleisenger and Fordtran's Gastrointestinal and Liver Disease: Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, Management. 11th ed. Elsevier; 2021. https://www.clinicalkey.com. Accessed Oct. 20, 2020.

- Hypersmolar hyperglycemic state (HHS). Merck Manual Professional Version. https://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/endocrine-and-metabolic-disorders/diabetes-mellitus-and-disorders-of-carbohydrate-metabolism/hyperosmolar-hyperglycemic-state-hhs. Accessed Dec. 11, 2020.

- Diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA). Merck Manual Professional Version. https://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/endocrine-and-metabolic-disorders/diabetes-mellitus-and-disorders-of-carbohydrate-metabolism/diabetic-ketoacidosis-dka. Accessed Dec. 11, 2020.

- Hypoglycemia. Merck Manual Professional Version. https://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/endocrine-and-metabolic-disorders/diabetes-mellitus-and-disorders-of-carbohydrate-metabolism/hypoglycemia. Accessed Dec. 11, 2020.

- 6 things to know about diabetes and dietary supplements. National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health. https://www.nccih.nih.gov/health/tips/things-to-know-about-type-diabetes-and-dietary-supplements. Accessed Dec. 11, 2020.

- Type 2 diabetes and dietary supplements: What the science says. National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health. https://www.nccih.nih.gov/health/providers/digest/type-2-diabetes-and-dietary-supplements-science. Accessed Dec. 11, 2020.

- Preventing diabetes problems. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/diabetes/overview/preventing-problems/all-content. Accessed Dec. 3, 2020.

- Schillie S, et al. Prevention of hepatitis B virus infection in the United States: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR Recommendations and Reports. 2018; doi:10.15585/mmwr.rr6701a1.

- Diabetes prevention: 5 tips for taking control

- Hyperinsulinemia: Is it diabetes?

Associated Procedures

News from mayo clinic.

- Mayo study uses electronic health record data to assess metformin failure risk, optimize care Feb. 10, 2023, 02:30 p.m. CDT

- Mayo Clinic Minute: Strategies to break the heart disease and diabetes link Nov. 28, 2022, 05:15 p.m. CDT

- Mayo Clinic Q and A: Diabetes risk in Hispanic people Oct. 20, 2022, 12:15 p.m. CDT

- The importance of diagnosing, treating diabetes in the Hispanic population in the US Sept. 28, 2022, 04:00 p.m. CDT

- Mayo Clinic Minute: Managing Type 2 diabetes Sept. 28, 2022, 02:30 p.m. CDT

Products & Services

- A Book: The Essential Diabetes Book

- A Book: The Mayo Clinic Diabetes Diet

- Assortment of Health Products from Mayo Clinic Store

- Symptoms & causes

- Diagnosis & treatment

- Doctors & departments

Mayo Clinic does not endorse companies or products. Advertising revenue supports our not-for-profit mission.

- Opportunities

Mayo Clinic Press

Check out these best-sellers and special offers on books and newsletters from Mayo Clinic Press .

- Mayo Clinic on Incontinence - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Incontinence

- The Essential Diabetes Book - Mayo Clinic Press The Essential Diabetes Book

- Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance

- FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment - Mayo Clinic Press FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment

- Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book

Your gift holds great power – donate today!

Make your tax-deductible gift and be a part of the cutting-edge research and care that's changing medicine.

Masks Strongly Recommended but Not Required in Maryland, Starting Immediately

Due to the downward trend in respiratory viruses in Maryland, masking is no longer required but remains strongly recommended in Johns Hopkins Medicine clinical locations in Maryland. Read more .

- Vaccines

- Masking Guidelines

- Visitor Guidelines

Division of General Internal Medicine

Diabetes self management patient education materials, table of contents.

Click on any of the links below to access helpful materials on managing all aspects of diabetes that can be printed and given to your patients .

Introductory Information

- Diabetes Mellitus Type 1 : Symptoms, diagnosis, prevention, and treatment (e.g., insulin)

- Diabetes Mellitus Type 2 : Symptoms, diagnosis, prevention, and treatment (e.g., medications)

- Women and Diabetes: Eating and weight, pregnancy, and heart disease

- Men and Diabetes: Sexual Issues and employment concerns

- Diabetes and Your Lifestyle : Exercise, traveling, employment, sexual issues, and special considerations for the elderly

General Self-Care (e.g., Blood Glucose, Foot Care)

Blood glucose.

- Pass This Test : Testing blood glucose levels

- Tool: Blood Sugar Monitoring Log (Oral Meds): Patient log to record levels

- Tool: Blood Sugar Monitoring Log (Insulin Meds): Patient log to monitor levels

- Tool: Foot Care Log : Patient log to record self-inspections and any problem areas

- Tool: Injection Sites : Patient log to help rotate injection sites

- Tool: Planning Your Exercise: Guide to help patients design an exercise program

- Tool: Physical Activity Log : Patient log to record physical activity

- Exercise in Disguise: Finding ways to exercise at home and outside of the gym

- Exercising Like Your Life Depends on It: Health benefits to exercising

- Hot Weather Exercise: Taking extra care when exercising in hot weather

Nutrition/Health

Diet/weight loss.

- Managing Type 2 Diabetes through Diet : Suggestions for balancing your diet

- Losing Weight When You Have Diabetes: Weight loss benefits, suggestions to start, and a brief discussion of weight loss drugs

- The Skinny on Visceral Fat : Dangers of visceral fat and exercise tips to reduce visceral fat

Meal Planning

- Tool: Shopping Guide and Nutrition Tips: Shopping list and money-saving tips

- Tool: Meal Planning Guides: Plate diagrams demonstrating appropriate portions

- Tool: Food Log : Patient log to record food and drink

- No More Carb Confusion : Understanding carbs and their effect on blood sugar

Smoking and Alcohol

- Mixing Alcohol with Diabetes: What drinking does to your body, and when it is ok

- Tool: Sick Day Guidelines: Tips, suggested foods, and patient log to record intake

- Diabetes and Stress : Immediate and long-term affects, and tips to manage stress

Medical Care Topics / Relation to Other Illnesses

- Infections and Diabetes: Explains increased chance for infections

- Make the DASH to Lower Your Blood Pressure : Nutrition tips to lower hypertension

Heart Smart

- Diabetes and Your Heart : "ABC" numbers and their link to heart disease

- Heart Smart Medications : Types of medications to prevent heart problems

- Young at Heart : Suggestions to reverse heart disease and tips for heart health

Vascular Disease

- Microvascular Disease Due to Diabetes: Discusses increased risk for eye and kidney problems

- Macrovascular Disease Due to Diabetes: Discusses increased risk for heart attack and stroke

- Preserving Kidney Function : Preserving Kidney function, especially when damage has already occurred

- Keeping Kidneys Healthy: Tips for kidney health and some "kidney-protective" meds

- Nine Ways to Avoid Diabetes Complications : Overview of tips to manage diabetes (healthy eating, activity, checking feet, etc.)

Other Topics

- Wake-up Call: Symptoms of sleep apnea, and the effects of lost sleep

Patient Education Library

Types of Physical Activity

Plan Your Plate

Best Foods For You: Making Healthy Food Choices

Your Mental Health and Diabetes

Fact Sheets

- At A Glance

- Diabetes and Prediabetes Fact Sheet

- On Your Way to Preventing Type 2 Diabetes

- Take Charge of Your Diabetes: Your Medicines

- Take Charge of Your Diabetes: Healthy Eyes

- Take Charge of Your Diabetes: Healthy Feet

- Take Charge of Your Diabetes: Healthy Teeth

- Take Charge of Your Diabetes: Healthy Ears

- Take Care of Your Kidneys and They Will Take Care of You

- How to Help a Loved One With Diabetes When You Live Far Apart

- Choosing Healthy Foods on Holidays and Special Occasions

- Tasty Recipes for People with Diabetes [PDF - 9 MB]

- Steps to Help You Stay Healthy With Diabetes

- 5 Questions to Ask Your Health Care Team

- Managing Diabetes: Medicare Coverage and Resources [PDF - 1 MB]

- Road to Health Toolkit (English) This collection of tools is tailored to African Americans and can be used to counsel and motivate those at high risk for type 2 diabetes.

- Road to Health Toolkit (Spanish)/Kit El camino hacia la buena salud This collection of tools can be used to counsel and motivate those at high risk for type 2 diabetes.

- Road to Health: Blaze Your Own Trail to Healthy Living [PDF – 6.91MB] This flipchart is culturally adapted to counsel and motivate American Indian people who are at risk for type 2 diabetes.

To receive updates about diabetes topics, enter your email address:

- Diabetes Home

- State, Local, and National Partner Diabetes Programs

- National Diabetes Prevention Program

- Native Diabetes Wellness Program

- Chronic Kidney Disease

- Vision Health Initiative

- Heart Disease and Stroke

- Overweight & Obesity

Exit Notification / Disclaimer Policy

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) cannot attest to the accuracy of a non-federal website.

- Linking to a non-federal website does not constitute an endorsement by CDC or any of its employees of the sponsors or the information and products presented on the website.

- You will be subject to the destination website's privacy policy when you follow the link.

- CDC is not responsible for Section 508 compliance (accessibility) on other federal or private website.

- GP practice services

- Health advice

- Health research

- Medical professionals

- Health topics

Advice and clinical information on a wide variety of healthcare topics.

All health topics

Latest features

Allergies, blood & immune system

Bones, joints and muscles

Brain and nerves

Chest and lungs

Children's health

Cosmetic surgery

Digestive health

Ear, nose and throat

General health & lifestyle

Heart health and blood vessels

Kidney & urinary tract

Men's health

Mental health

Oral and dental care

Senior health

Sexual health

Signs and symptoms

Skin, nail and hair health

Travel and vaccinations

Treatment and medication

Women's health

Healthy living

Expert insight and opinion on nutrition, physical and mental health.

Exercise and physical activity

Healthy eating

Healthy relationships

Managing harmful habits

Mental wellbeing

Relaxation and sleep

Managing conditions

From ACE inhibitors for high blood pressure, to steroids for eczema, find out what options are available, how they work and the possible side effects.

Featured conditions

ADHD in children

Crohn's disease

Endometriosis

Fibromyalgia

Gastroenteritis

Irritable bowel syndrome

Polycystic ovary syndrome

Scarlet fever

Tonsillitis

Vaginal thrush

Health conditions A-Z

Medicine information

Information and fact sheets for patients and professionals. Find out side effects, medicine names, dosages and uses.

All medicines A-Z

Allergy medicines

Analgesics and pain medication

Anti-inflammatory medicines

Breathing treatment and respiratory care

Cancer treatment and drugs

Contraceptive medicines

Diabetes medicines

ENT and mouth care

Eye care medicine

Gastrointestinal treatment

Genitourinary medicine

Heart disease treatment and prevention

Hormonal imbalance treatment

Hormone deficiency treatment

Immunosuppressive drugs

Infection treatment medicine

Kidney conditions treatments

Muscle, bone and joint pain treatment

Nausea medicine and vomiting treatment

Nervous system drugs

Reproductive health

Skin conditions treatments

Substance abuse treatment

Vaccines and immunisation

Vitamin and mineral supplements

Tests & investigations

Information and guidance about tests and an easy, fast and accurate symptom checker.

About tests & investigations

Symptom checker

Blood tests

BMI calculator

Pregnancy due date calculator

General signs and symptoms

Patient health questionnaire

Generalised anxiety disorder assessment

Medical professional hub

Information and tools written by clinicians for medical professionals, and training resources provided by FourteenFish.

Content for medical professionals

FourteenFish training

Professional articles

Evidence-based professional reference pages authored by our clinical team for the use of medical professionals.

View all professional articles A-Z

Actinic keratosis

Bronchiolitis

Molluscum contagiosum

Obesity in adults

Osmolality, osmolarity, and fluid homeostasis

Recurrent abdominal pain in children

Medical tools and resources

Clinical tools for medical professional use.

All medical tools and resources

Type 2 diabetes

Peer reviewed by Dr Krishna Vakharia, MRCGP Last updated by Dr Colin Tidy, MRCGP Last updated 26 Apr 2023

Meets Patient’s editorial guidelines

In this series: Type 2 diabetes treatment Type 2 diabetes diet

Type 2 diabetes can occur at any age, including during childhood, but it occurs mainly in people aged over 40. The first-line treatment is diet, weight control and physical activity.

The good news is that many people can stay well using these lifestyle measures. However if the blood sugar (glucose) level remains high then tablets to reduce the blood glucose level are usually advised. Insulin injections are needed in some cases. Other treatments include reducing blood pressure if it is high, lowering high cholesterol levels, and also other measures to reduce the risk of complications.

In this article :

What is type 2 diabetes, how common is type 2 diabetes, type 2 diabetes symptoms, type 2 diabetes diagnosis, type 2 diabetes complications, what are the aims of type 2 diabetes treatment, treatment aim 1 - keeping your blood sugar (glucose) level at normal levels, treatment aim 2 - to reduce other risk factors, treatment aim 3 - monitoring to detect and treat any complications promptly, immunisation.

Continue reading below

Playlist: What is Diabetes?

Dr. Partha Kar, FRCP

How do you explain type 2 diabetes to your child?

Type 2 diabetes and its symptoms tend to develop gradually (over weeks or months). This is because in type 2 diabetes you still make insulin (unlike in type 1 diabetes ). However, you develop type 2 diabetes because:

You do not make enough insulin for your body's needs; or

The cells in your body do not use insulin properly. This is called insulin resistance. The cells in your body become resistant to normal levels of insulin. This means that you need more insulin than you normally make to keep the blood sugar (glucose) level down; or

A combination of the above two reasons.

You can learn more about insulin and blood glucose from our separate leaflet called Diabetes (Diabetes Mellitus) .

Type 2 diabetes is much more common than type 1 diabetes.

Type 2 diabetes develops mainly in people older than the age of 40 but type 2 diabetes is now becoming far more common in children and in young people.

The number of people with type 2 diabetes is increasing in the UK, as it is more common in people who are overweight or obese. It also tends to run in families. Type 2 diabetes is around five times more common in South Asian and African-Caribbean people (often developing before the age of 40 in this group). It is estimated that by 2025 more than 5 million people in the UK will be diagnosed with diabetes.

Playlist: Risks of Diabetes

Who is most at risk from type 2 diabetes.

Is type 2 diabetes hereditary?

How can I avoid getting a hypo?

Dr. Sarah Jarvis MBE, FRCGP

What can someone with type 1 diabetes do to stop their blood glucose going too high?

Other risk factors.

Having a first-degree relative with type 2 diabetes. (A first-degree relative is a parent, brother, sister, or child.)

Being overweight or obese .

Having a waist measuring more than 31.5 inches (80 cm) if you are a woman or more than 37 inches (94 cm) if you are a man. Where in your body you store excess weight is important. Central obesity (a big tummy) probably happens because of the effect of insulin pushing excess sugar into abdominal fat cells over the years.

Having pre-diabetes (impaired glucose tolerance) . Impaired glucose tolerance means that your blood sugar (glucose) levels are higher than normal but not high enough to have diabetes. People with impaired glucose tolerance have a high risk of developing diabetes and so impaired glucose tolerance is often called pre-diabetes.

Having diabetes or pre-diabetes when you were pregnant .

How do you know if you have type 2 diabetes?

As already mentioned, type 2 diabetes symptoms often come on gradually and can be quite vague at first. Many people have type 2 diabetes for a long period of time before their diagnosis is made.

The most common type 2 diabetes symptoms are:

Being thirsty a lot of the time.

Passing large amounts of urine.

Tiredness, which may be worse after meals.

The reason why you make a lot of urine and become thirsty is that if your blood sugar (glucose) rises too high (because insulin is not doing its job) the excess sugar leaks into your urine. This pulls out extra water through the kidneys.

As the type 2 diabetes symptoms may develop gradually, you can become used to being thirsty and tired and you may not recognise for some time that you are ill. Some people also develop blurred vision and frequent infections, such as recurring thrush.

However, some people with type 2 diabetes do not have any symptoms if the glucose level is not too high. But, even if you do not have symptoms, you should still have treatment to reduce the risk of developing complications.

Patient picks for Type 2 diabetes

Video: How do you know if you have type 2 diabetes?

Type 2 diabetes diet

How do you get tested for type 2 diabetes.

A simple dipstick test may detect sugar (glucose) in a sample of urine. However, this is not enough to make a definite diagnosis of type 2 diabetes. Therefore, a blood test called HbA1c is needed to make the diagnosis. The blood test detects the level of glucose in your blood . If the glucose level is high then it will confirm that you have type 2 diabetes.

Some people have to have two samples of blood taken and may be asked to fast. (Fasting means having nothing to eat or drink, other than water, from midnight before the blood test is performed.)

It is now recommended that the blood test for HbA1c can also be used as a test to diagnose type 2 diabetes. An HbA1c value of 48 mmol/mol (6.5%) or above is recommended as the blood level for diagnosing type 2 diabetes. An HbA1c blood test gives an average of how high your blood glucose levels have been over the preceding few months.

In many cases type 2 diabetes is diagnosed during a routine medical or when tests are done for an unrelated medical condition.

Short-term complication - a very high glucose level

This is rare with type 2 diabetes. It is more common in untreated type 1 diabetes when a very high level of blood sugar (glucose) can develop quickly. However, a very high glucose level develops in some people with untreated type 2 diabetes. A very high blood level of glucose can cause lack of fluid in the body (dehydration), drowsiness and serious illness which can be life-threatening.

Long-term complications

If your blood glucose level is higher than normal over a long period of time, it can gradually damage your blood vessels. This can occur even if the glucose level is not very high above the normal level. This may lead to some of the following complications (often years after you first develop type 2 diabetes):

Furring, or 'hardening', of the arteries (atheroma) . This can cause problems such as angina , heart attacks, stroke and poor circulation.

Kidney damage which sometimes develops into chronic kidney disease .

Eye problems which can affect vision (due to damage to the small arteries of the retina at the back of the eye).

Nerve damage .

Foot problems (due to poor circulation and nerve damage).

Impotence (again due to poor circulation and nerve damage).

Other rare problems.

The type and severity of long-term complications vary from case to case. You may not develop any at all. In general, the nearer your blood glucose level is to normal, the less your risk of developing complications . Your risk of developing complications is also reduced if you deal with any other risk factors that you may have, such as high blood pressure.

It has been found that people with type 2 diabetes are more at risk of periodontitis. This is a condition that destroys the tissues supporting your teeth. Untreated, this could lead to tooth loss. It can start with gingivitis which is an inflammation of the gums. Left untreated, this leads to periodontitis and further severe gum conditions.

At your annual review, your doctor will remind you to have checks with your dentist. If you do have periodontitis, managing this illness can improve blood sugar control so it is best to keep those regular reviews with your dentist.

Complications of type 2 diabetes treatment

Medications for type 2 diabetes, like most other medications, can cause side-effects in some people. You can find out more about diabetes medications and their side-effects from our separate leaflet called Type 2 Diabetes Treatment .

However, one important side-effect which can affect people taking insulin and/or certain diabetes tablets is hypoglycaemia (often called a 'hypo'). This occurs when the level of glucose becomes too low, usually under 4 mmol/L. Not all tablet medicines used for diabetes can cause a hypo - for example, metformin does not cause this.

A hypo may occur if you have too much diabetes medication, have delayed or missed a meal or snack, or have taken part in unplanned exercise or physical activity. You can find out more about the symptoms and treatments of hypos from our separate leaflet called Hypoglycaemia (Low Blood Sugar) .

Until about 20 years ago, the medication options for treatment of type 2 diabetes were fairly limited. Insulin, along with a group of medicines called the sulfonylureas, can cause hypos (as well as weight gain). In the last 20 years, as newer medication has been developed, many people do not need to take sulfonylureas. In fact, more and more people never need to take insulin as newer agents offer more options for type 2 diabetes treatment.

Note: hypoglycaemia does not occur if you are treated with diet alone .

If you have type 2 diabetes, you may think that keeping your blood sugar (glucose) at normal levels is all that matters. In fact, while that's important, there's more to treatment than this.

Lifestyle changes are an essential part of treatment for all people with type 2 diabetes, regardless of whether or not they take medication.

Many people with type 2 diabetes can reduce their blood glucose (and HbA1c) to a target level with changes to their diet, weight and exercise levels. However, if the blood sugar (or HbA1c) level remains too high after a trial of these measures for a few months, then medication is usually advised.

Diet, weight control and physical activity

Diet. What you eat is absolutely central to your blood glucose control, as well as your general health. Please read our separate leaflet called Type 2 Diabetes Diet for more information. Your practice nurse or dietician can give you more information and support.

Lose weight if you are overweight. Getting to a perfect weight is unrealistic for many people. However, losing some weight if you are obese or overweight will help to reduce your blood glucose and blood pressure levels (and have other health benefits too). Recent evidence from Professor Taylor, Newcastle University, has shown that weight loss alone can put diabetes into drug-free remission in at least a third of patients.

Do some physical activity regularly. If you are able, a minimum of 30 minutes' brisk walking at least five times a week is advised. Anything more vigorous and more often is even better - for example, swimming, cycling, jogging, dancing. Ideally, you should do an activity that gets you at least mildly out of breath and mildly sweaty. You can spread the activity over the day - for example, two fifteen-minute spells per day of brisk walking, cycling, dancing, etc. Regular physical activity also reduces your risk of having a heart attack or stroke.

Medication is not used instead of a healthy diet, weight control and physical activity - you should still do these things as well as take medication. See our separate leaflet called Type 2 Diabetes Treatment for more details .

How is the blood glucose level monitored?

The blood test that is mainly used to keep a check on your blood glucose level is called the HbA1c test . This test is commonly done every 2-6 months by your doctor or nurse.

The HbA1c test measures a part of the red blood cells. Glucose in the blood attaches to part of the red blood cells. This part can be measured and gives a good indication of your average blood glucose level over the preceding 1-3 months.

Type 2 diabetes treatment aims to lower your HbA1c to below a target level. Ideally, it is best to maintain HbA1c to less than 48 mmol/mol (6.5%). However, this may not always be possible to achieve and your target level of HbA1c should be agreed between you and your doctor.

If your HbA1c is above your target level then you may be advised to step up treatment (for example, to increase a dose of medication) to keep your blood glucose level down.

Some people with diabetes check their actual blood glucose level regularly with a blood glucose monitor. If you are advised to do this then your doctor or nurse will give you instructions on how to do it.

Continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) has recommended that CGM should be offered to some people using insulin several times a day. They recommend that your specialist team should offer this if:

You have repeated or severe episodes of hypoglycaemia ('hypos').

You have impaired hypoglycaemia awareness, where you don't recognise the early symptoms of hypos.

You have a condition or disability for which you can't use regular finger-prick testing.

You need to measure your blood glucose at least eight times a day.

You are less likely to develop complications of type 2 diabetes if you reduce any other risk factors. These are briefly mentioned below - see the separate leaflet called Cardiovascular Disease (Atheroma) for more details . Although everyone should aim to cut out preventable risk factors, people with diabetes have even more of a reason to do so.

Keep your blood pressure down

It is very important to have your blood pressure checked regularly. The combination of high blood pressure and diabetes is a particularly high risk factor for complications. Even mildly raised blood pressure should be treated if you have type 2 diabetes. Medication, often with two or even three different medicines, may be needed to keep your blood pressure down but remember weight loss and exercise can really help with this too.

See the separate leaflet called Diabetes and High Blood Pressure for more details.

If you smoke - now is the time to stop

Smoking is a major risk factor for complications . You should consult your practice nurse or attend a smoking cessation clinic - it's much easier to quit with support. As well as expert help and advice, medication or nicotine replacement therapy (nicotine gum, etc) may help you to stop.

Other medication

You will usually be advised to take a medicine to lower your cholesterol level . This will help to lower the risk of developing some complications such as heart disease , peripheral arterial disease and stroke .

Protect your kidneys

Keeping your blood glucose well controlled can reduce your risk of kidney damage. But a group of medications first developed to treat type 2 diabetes can provide added protection against developing and worsening chronic kidney disease.

These medicines, called SGLT-2 inhibitors, are now recommended for everyone with type 2 diabetes who has chronic kidney disease with protein in the urine. This is one of the reasons getting regular kidney checks (see below) is so important.

In fact, some medicines in this class are now used to protect the kidneys in people who have chronic kidney disease but who do not have diabetes.

You can find out more about the SGLT-2 inhibitors in our leaflet on type 2 diabetes treatment .

Most GP surgeries and hospitals have special diabetes clinics. Doctors, nurses, dieticians, specialists in foot care (podiatrists - previously called chiropodists), specialists in eye health (optometrists) and other healthcare workers all play a role in giving advice and checking on progress. Regular checks may include:

Checking levels of blood sugar (glucose), HbA1c, cholesterol and blood pressure.

Ongoing advice on diet and lifestyle.

Checking for early signs of complications - for example:

Eye checks - see more detail below.

Urine tests - which include testing for protein in the urine, which may indicate early kidney problems.

Foot checks - to help prevent foot ulcers .

Other blood tests - these include checks on kidney function and other general tests.

It is important to have regular checks, as some complications, particularly if detected early, can be treated or prevented from becoming worse.

Eye screening

Regular (at least yearly) eye checks can detect problems with the retina (a possible complication of diabetes), which can often be prevented from becoming worse. Increased pressure in the eye ( glaucoma ) is more common in people with diabetes and can usually be treated.

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) has updated its recommendations on eye screening and treatment in an update of its guidance on type 2 diabetes.

Eye checks usually include taking photographs of the back of your eye (retinal photography) to see whether there are any problems. This needs to be done at a specialist eye screening clinic.

The guidance recommends that:

You should be referred to a specialist local eye screening service as soon as you are diagnosed with type 2 diabetes.

If your eyesight suddenly deteriorates significantly without any obvious explanation, you should be referred to a specialist eye doctor (an ophthalmologist). How urgently you are referred will depend on your symptoms and personal circumstances.

You should be immunised against flu (each autumn) and also against pneumococcal germs (bacteria) - a vaccination just given once. These infections can be particularly unpleasant if you have diabetes.

Further reading and references

- Management of diabetes ; Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network - SIGN (March 2010 - updated November 2017)

- Diabetes UK

- Diabetes and Bad Cholesterol Information Prescription ; Diabetes UK

- Diabetes (type 1 and type 2) in children and young people: diagnosis and management ; NICE Guidelines (Aug 2015 - updated May 2023)

- Type 2 diabetes in adults: management ; NICE Guidance (December 2015 - last updated June 2022)

- Information prescriptions - living well ; Diabetes UK

- d-Nav insulin management app for type 2 diabetes ; NICE Medtech innovation briefing, February 2022

- Diabetes - type 2 ; NICE CKS, November 2023 (UK access only)

- Type 2 diabetes in adults ; NICE Quality standard, March 2023

Article History

The information on this page is written and peer reviewed by qualified clinicians.

Next review due: 24 Mar 2028

26 apr 2023 | latest version.

Last updated by

Peer reviewed by

Feeling unwell?

Assess your symptoms online for free

You are now leaving the Lilly Medical Education website

The link you clicked on will take you to a site maintained by a third party, which is solely responsible for its content. Lilly USA, LLC does not control, influence, or endorse this site, and the opinions, claims, or comments expressed on this site should not be attributed to Lilly USA, LLC. Lilly USA, LLC is not responsible for the privacy policy of any third-party websites. We encourage you to read the privacy policy of every website you visit. Click "Continue" to proceed or "Return" to return to Lilly Medical Education.

Type 2 Diabetes Patient Case Simulation

Case Simulation 1

CLINIC- Sim : Simulating a Patient-Centered Approach to Optimize Early Glycemic and Weight Control in Type 2 Diabetes

Learn more about glycemic control and weight management in type 2 diabetes

Shared decision-making resources, watch an expert video on shared decision-making and download the conversation starter to aid in your patient interactions.

These videos were commissioned by Lilly and are intended to be used by HCPs who treat diabetes for medical, scientific and educational purposes. Video content is not approved for continuing education credit. Disclosures: Dr. Matt Capehorn

- Board member of the Association for the Study of Obesity (ASO)

- Faculty member of the Primary care Academy of Diabetes Specialists (PCADS)

- Expert Advisor to NICE

- Professional Advisor to the Obesity Empowerment Network (OEN)

- Director – RIO Weight management Limited

- Medical Director – Lighterlife (commercial VLCD company)

- Ad-hoc Medical Advisor – McDonalds UK

Advisory Boards: Lilly, Boehringer Ingelheim, Novo Nordisk; Speaker fees/travel: Lilly, Boehringer Ingelheim, Novo Nordisk; Research income (RIO): Lilly, Boehringer Ingelheim, Novo Nordisk

Patient Information

Expand accordion Patient Profile

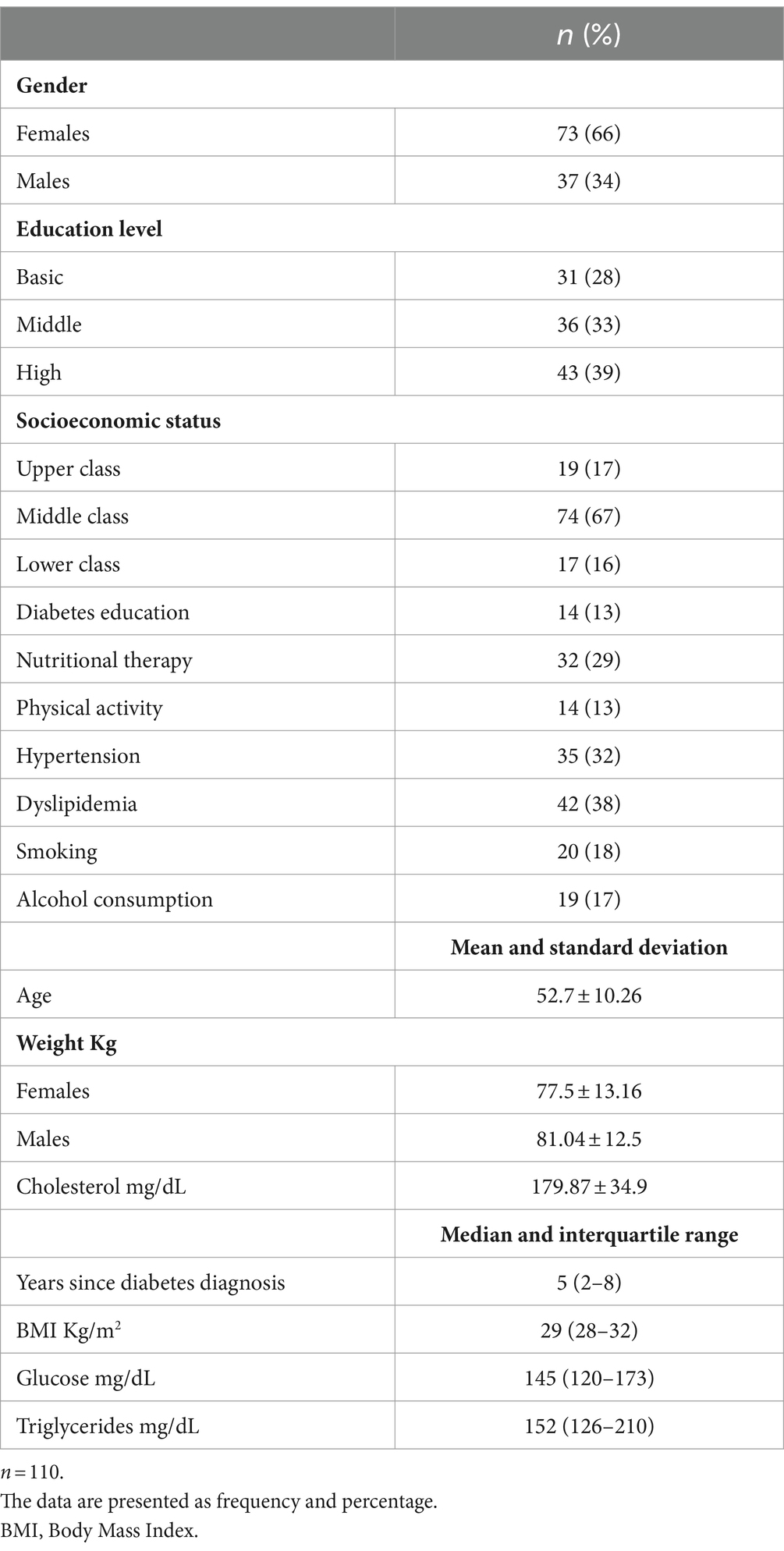

- 47-year-old African American female

- Diagnosed with T2D 9 months ago

- HbA 1c since diagnosis: 8.7%

- Current treatment: 1000 mg metformin daily at diagnosis

- Followed by registered dietitian/nurse educator

Expand accordion Medical History

- Prediabetes for 2 years preceding diagnosis, tried to manage with diet and exercise

- Gestational diabetes with her second child

- Hypertension

- Mixed dyslipidemia

Expand accordion Family History

- T2D in father, maternal aunt

- CAD in father

- Hypertension in mother and father

Expand accordion Social History

- Married, has 2 children ages 10 and 15

- Never smoked or vaped, no illicit substances, rarely drinks alcohol

- High school math teacher

Expand accordion Physical Exam and Labs

- Normal eGFR, normal urine microalbumin

- BMI: 33 kg/m 2 (195 lbs)

- Blood pressure: 145/90 mmHg

- Total cholesterol: 210 mg/dL

- LDL cholesterol: 109 mg/dL

- HDL cholesterol: 44 mg/dL

- Triglycerides: 290 mg/dL

9 months since diagnosis The patient was diagnosed with type 2 diabetes, and her HbA 1c was 8.7% at the time. She was started on 1000 mg metformin daily. During that visit, she was advised on lifestyle modifications, including dietary changes to help both her diabetes and hypertension management, as well as recommendations to incorporate exercise. She was encouraged to start a statin for dyslipidemia but was too overwhelmed by her diabetes and declined statin therapy. At visit 2, her HbA 1c decreased to 7.9%. She again declined a statin and agreed to start an ACE inhibitor. Her metformin was titrated to 1500 mg total daily dose.

13 months since diagnosis (4-month follow-up)

- She returns 4 months later.

- She is taking a dose of 1500 mg metformin daily (500 mg in the morning and 1000 mg in the evening) without missing doses. She was not able to tolerate a dose of 1000 mg twice daily. Her HbA 1c has decreased to 7.7% from 7.9%, and her body weight remained stable.

- Blood pressure: 130/85 mmHg

- Total cholesterol: 205 mg/dL

- LDL cholesterol: 110 mg/dL

- HDL cholesterol: 43 mg/dL

- Triglycerides: 260 mg/dL

- She increased her physical activity by parking farther and trying to walk more, but often struggles to find the time to get more exercise in.

- She tries to eat more balanced meals with protein, vegetables and fewer carbohydrates; she finds it difficult to make multiple meals for her family members who prefer to keep to their old dietary routine.

- She is motivated to continue working on lifestyle changes and has agreed to start a statin.

Question #1

In addition to continuing metformin 1500 mg daily, which of the following may be the next best step.

Continue lifestyle modifications – she is very motivated and prefers not to start another medication

Start a sulfonylurea and continue lifestyle modifications

Start an incretin receptor agonist and continue lifestyle modifications

Start a DPP-4 inhibitor

Related Resources

Hear from Dr. Capehorn on collaborating with patients to individualize care.

VV-MED-145674

Patient-Physician Conversation Starter (PDF)

Tips and tricks to initiate patient centric conversations.

VV-MED-145677

Shared Decision-Making (PDF)

Support early glycemic control and weight management through shared decision-making.

VV-MED-148828

VV-MED-144376

Create Free Account or

- Acute Coronary Syndromes

- Anticoagulation Management

- Arrhythmias and Clinical EP

- Cardiac Surgery

- Cardio-Oncology

- Cardiovascular Care Team

- Congenital Heart Disease and Pediatric Cardiology

- COVID-19 Hub

- Diabetes and Cardiometabolic Disease

- Dyslipidemia

- Geriatric Cardiology

- Heart Failure and Cardiomyopathies

- Invasive Cardiovascular Angiography and Intervention

- Noninvasive Imaging

- Pericardial Disease

- Pulmonary Hypertension and Venous Thromboembolism

- Sports and Exercise Cardiology

- Stable Ischemic Heart Disease

- Valvular Heart Disease

- Vascular Medicine

- Clinical Updates & Discoveries

- Advocacy & Policy

- Perspectives & Analysis

- Meeting Coverage

- ACC Member Publications

- ACC Podcasts

- View All Cardiology Updates

- Earn Credit

- View the Education Catalog

- ACC Anywhere: The Cardiology Video Library

- CardioSource Plus for Institutions and Practices

- ECG Drill and Practice

- Heart Songs

- Nuclear Cardiology

- Online Courses

- Collaborative Maintenance Pathway (CMP)

- Understanding MOC

- Image and Slide Gallery

- Annual Scientific Session and Related Events

- Chapter Meetings

- Live Meetings

- Live Meetings - International

- Webinars - Live

- Webinars - OnDemand

- Certificates and Certifications

- ACC Accreditation Services

- ACC Quality Improvement for Institutions Program

- CardioSmart

- National Cardiovascular Data Registry (NCDR)

- Advocacy at the ACC

- Cardiology as a Career Path

- Cardiology Careers

- Cardiovascular Buyers Guide

- Clinical Solutions

- Clinician Well-Being Portal

- Diversity and Inclusion

- Infographics

- Innovation Program

- Mobile and Web Apps

ACP Guideline on Pharmacologic Treatments for Diabetes: Key Points

The following are key points to remember about a clinical guideline from the American College of Physicians (ACP) on newer pharmacologic treatments in adults with type 2 diabetes:

- Type 2 diabetes is associated with higher risk for mortality and morbidity, greater health care use, and greater costs when adults with diabetes are compared with those without diabetes.

- Major treatment goals for patients with type 2 diabetes include adequate glycemic control and primary and secondary prevention of atherosclerotic cardiovascular and kidney diseases, which account for nearly one half of all deaths among adults with type 2 diabetes.

- This guideline addresses effectiveness and harms of newer pharmacologic treatments to reduce the risk for all-cause mortality, cardiovascular morbidity, and progression of chronic kidney disease (CKD) in adults with type 2 diabetes.

- Newer pharmacologic treatments include glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) agonists (dulaglutide, exenatide, liraglutide, lixisenatide, and semaglutide), a GLP-1 agonist and glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide agonist (tirzepatide), sodium–glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT-2) inhibitors (canagliflozin, dapagliflozin, empagliflozin, and ertugliflozin), dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4) inhibitors (alogliptin, linagliptin, saxagliptin, and sitagliptin), and long-acting insulins (insulin glargine and insulin degludec).

- The ACP recommends adding an SGLT-2 inhibitor or GLP-1 agonist to metformin and lifestyle modifications in adults with type 2 diabetes and inadequate glycemic control (strong recommendation; high-certainty evidence).

- Use of an SGLT-2 inhibitor is recommended to reduce the risk for all-cause mortality, major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE), progression of CKD, and hospitalization due to congestive heart failure [CHF]. Clinicians should prioritize adding SGLT-2 inhibitors in patients with type 2 diabetes and CHF or CKD.

- Use of a GLP-1 agonist is recommended to reduce the risk for all-cause mortality, MACE, and stroke. Clinicians should prioritize adding GLP-1 agonists in patients with type 2 diabetes and an increased risk for stroke or for whom total body weight loss is an important treatment goal.

- The ACP recommends against adding a dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4) inhibitor to metformin and lifestyle modifications in adults with type 2 diabetes and inadequate glycemic control to reduce morbidity and all-cause mortality (strong recommendation; high-certainty evidence).

- Metformin (unless contraindicated) and lifestyle modifications are the first steps in managing type 2 diabetes in most patients. When selecting an additional therapy, clinicians should consider the evidence of benefits, harms, patient burden, and cost of medications in addition to performing an individualized assessment of each patient’s preferences, glycemic control target, comorbid conditions, and risk for symptomatic hypoglycemia.

- Overall, clinicians should aim to achieve glycated hemoglobin (HbA 1c ) levels between 7% and 8% in most adults with type 2 diabetes and deintensify pharmacologic treatments in adults with HbA 1c levels <6.5%. An individualized glycemic goal should be based on risk for hypoglycemia, life expectancy, diabetes duration, established vascular complications, major comorbidities, patient preferences and access to resources, capacity for adequate monitoring of hypoglycemia, and other harms.

- Finally, type 2 diabetes management should be based on collaborative communication and goal setting among all team members, including clinical pharmacists, to reduce the risk for polypharmacy and associated harms.

Clinical Topics: Diabetes and Cardiometabolic Disease, Prevention

Keywords: Diabetes Mellitus, Type 2, Pharmaceutical Preparations

You must be logged in to save to your library.

Jacc journals on acc.org.

- JACC: Advances

- JACC: Basic to Translational Science

- JACC: CardioOncology

- JACC: Cardiovascular Imaging

- JACC: Cardiovascular Interventions

- JACC: Case Reports

- JACC: Clinical Electrophysiology

- JACC: Heart Failure

- Current Members

- Campaign for the Future

- Become a Member

- Renew Your Membership

- Member Benefits and Resources

- Member Sections

- ACC Member Directory

- ACC Innovation Program

- Our Strategic Direction

- Our History

- Our Bylaws and Code of Ethics

- Leadership and Governance

- Annual Report

- Industry Relations

- Support the ACC

- Jobs at the ACC

- Press Releases

- Social Media

- Book Our Conference Center

Clinical Topics

- Chronic Angina

- Congenital Heart Disease and Pediatric Cardiology

- Diabetes and Cardiometabolic Disease

- Hypertriglyceridemia

- Invasive Cardiovascular Angiography and Intervention

- Pulmonary Hypertension and Venous Thromboembolism

Latest in Cardiology

Education and meetings.

- Online Learning Catalog

- Products and Resources

- Annual Scientific Session

Tools and Practice Support

- Quality Improvement for Institutions

- Accreditation Services

- Practice Solutions

Heart House

- 2400 N St. NW

- Washington , DC 20037

- Email: [email protected]

- Phone: 1-202-375-6000

- Toll Free: 1-800-253-4636

- Fax: 1-202-375-6842

- Media Center

- ACC.org Quick Start Guide

- Advertising & Sponsorship Policy

- Clinical Content Disclaimer

- Editorial Board

- Privacy Policy

- Registered User Agreement

- Terms of Service

- Cookie Policy

© 2024 American College of Cardiology Foundation. All rights reserved.

Learn how UpToDate can help you.

Select the option that best describes you

- Medical Professional

- Resident, Fellow, or Student

- Hospital or Institution

- Group Practice

- Patient or Caregiver

- Find in topic

RELATED TOPICS

Contributor Disclosures

Please read the Disclaimer at the end of this page.

TYPE 2 DIABETES OVERVIEW

Type 2 diabetes mellitus is a disorder that is known for disrupting the way your body uses glucose (sugar); it also causes other problems with the way your body stores and processes other forms of energy, including fat.

All the cells in your body need sugar to work normally. Sugar gets into the cells with the help of a hormone called insulin. In type 2 diabetes, the body stops responding to normal or even high levels of insulin, and over time, the pancreas (an organ in the abdomen) does not make enough insulin to keep up with what the body needs. Being overweight, especially having extra fat stored in the liver and abdomen, even if weight is normal, increases the body's demand for insulin. This causes high blood sugar (glucose) levels, which can lead to problems if untreated. (See "Patient education: Type 2 diabetes: Overview (Beyond the Basics)" .)

People with type 2 diabetes require regular monitoring and ongoing treatment to maintain normal or near-normal blood sugar levels. Treatment includes lifestyle changes (including dietary changes and exercise to promote weight loss), self-care measures, and sometimes medications, which can minimize the risk of diabetes and cardiovascular (heart-related) complications.

This topic review will discuss the medical treatment of type 2 diabetes.

DIABETES CARE DURING THE COVID-19 PANDEMIC

COVID-19 stands for "coronavirus disease 2019." It is an infection caused by a virus called SARS-CoV-2. The virus first appeared in late 2019 and has since spread throughout the world.

People with certain underlying health conditions, including diabetes, are at increased risk of severe illness if they get COVID-19. COVID-19 infection can also lead to severe complications of diabetes, including diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA).

Getting vaccinated lowers the risk of severe illness; experts recommend COVID-19 vaccination for anyone with cancer or a history

TYPE 2 DIABETES TREATMENT GOALS

The main goals of treatment in type 2 diabetes are to keep your blood sugar levels within your goal range and treat other medical conditions that go along with diabetes (like high blood pressure); it is also very important to stop smoking if you smoke. These measures will reduce your risk of complications.

Blood sugar control — It is important to keep your blood sugar levels at goal levels. This can help prevent long-term complications that can result from poorly controlled blood sugar (including problems affecting the eyes, kidney, nervous system, and cardiovascular system).

Home blood sugar testing — Your doctor may instruct you to check your blood sugar yourself at home, especially if you take certain oral diabetes medicines or insulin. Home blood sugar testing is not usually necessary for people who manage their diabetes through diet only or with diabetes medications that do not cause low blood sugar.

A random blood sugar test is based on blood drawn at any time of day, regardless of when you last ate. A fasting blood sugar test is a blood test done after not eating or drinking for 8 to 12 hours (usually overnight). A normal fasting blood sugar is more than 70 mg/dL (3.9 mmol/L) but less than 100 mg/dL (5.6 mmol/L), although people with diabetes may have a different goal. Your doctor or nurse can help you set a blood sugar goal and show you exactly how to check your level. (See "Patient education: Glucose monitoring in diabetes (Beyond the Basics)" .)

A1C testing — Blood sugar control can also be estimated with a blood test called glycated hemoglobin, or "A1C." The A1C blood test measures your average blood sugar level over the past two to three months. The goal A1C for most young people with type 2 diabetes is 7 percent (53 mmol/mol) or less, which corresponds to an average blood sugar of approximately 150 mg/dL (8.3 mmol/L) ( table 1 ). Lowering your A1C level reduces your risk for kidney, eye, and nerve problems. For some people, a different A1C goal may be more appropriate. Your health care provider can help determine your A1C goal.

Reducing the risk of cardiovascular complications — The most common, serious, long-term complication of type 2 diabetes is cardiovascular disease, which can lead to problems like heart attack, stroke, and even death. On average, people with type 2 diabetes have twice the risk of cardiovascular disease as people without diabetes.

However, you can substantially lower your risk of cardiovascular disease by:

● Quitting smoking, if you smoke

● Managing high blood pressure and high cholesterol with diet, exercise, and medicines

● Taking a low-dose aspirin every day, if you have a history of heart attack or stroke or if your health care provider recommends this

Some studies have shown that lowering A1C levels with certain medications may also reduce your risk for cardiovascular disease. (See 'Type 2 diabetes medicines' below.)

A detailed discussion of ways to prevent complications is available separately. (See "Patient education: Preventing complications from diabetes (Beyond the Basics)" .)

DIET AND EXERCISE IN TYPE 2 DIABETES

Diet and exercise are the foundation of diabetes management.

Changes in diet can improve many aspects of type 2 diabetes, including helping to control your weight, blood pressure, and your body's ability to produce and respond to insulin. The single most important thing most people can do to improve diabetes management and weight is to avoid all sugary beverages, such as soft drinks or juices, or if this is not possible, to significantly limit consumption. Limiting overall food portion size is also very important. Detailed information about type 2 diabetes and diet is available separately. (See "Patient education: Type 2 diabetes and diet (Beyond the Basics)" .)

Regular exercise can also help control type 2 diabetes, even if you do not lose weight. Exercise is related to blood sugar control because it improves your body's response to insulin. (See "Patient education: Exercise and medical care for people with type 2 diabetes (Beyond the Basics)" .)

TYPE 2 DIABETES MEDICINES

A number of medications are available to treat type 2 diabetes.

Metformin — Most people who are newly diagnosed with type 2 diabetes will immediately begin a medicine called metformin (sample brand names: Glucophage, Glumetza, Riomet, Fortamet). Metformin improves how your body responds to insulin to reduce high blood sugar levels.

Metformin is a pill that is usually started with a once-daily dose with dinner (or your last meal of the day); a second daily dose (with breakfast) is added one to two weeks later. The dose may be increased every one to two weeks thereafter.

Side effects — Common side effects of metformin include nausea, diarrhea, and gas. These are usually not severe, especially if you take metformin along with food. The side effects usually improve after a few weeks.