An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Springer Nature - PMC COVID-19 Collection

American Dreaming: Really Reading The Great Gatsby

William e. cain.

Department of English, Wellesley College, Wellesley, MA 02481 USA

F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby (1925) is one of the best known and most widely read and taught novels in American literature. It is so familiar that even those who have not read it believe that they have and take for granted that they know about its main character and theme of the American Dream. We need to approach The Great Gatsby as if it were new and really read it, paying close attention to Fitzgerald’s literary language. His novel gives us a vivid depiction of and insight into income inequality as it existed in the 1920s and, by extension, as it exists today, when the American Dream is even more limited to the fortunate few, not within reach of the many. When we really read The Great Gatsby , we perceive and understand the American dimension of the novel and appreciate, too, the global range and relevance that in it Fitzgerald has achieved. It is a great American book and a great book of world literature.

It is odd that we connect F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby to the American Dream, for this dream is one of equal opportunity, and the celebration of material well-being and personal success, of contentment and happiness, whereas the novel concludes with the demise of its deluded protagonist, shot dead in a swimming pool by a deranged husband who believes that Gatsby killed his wife by smashing into her in his fancy car.

We honor and profess to believe in the American Dream, a dream that we say the nation’s history has shown to be a reality for many millions. Those born at the bottom, but who possess spirit, pluck, and determination, can rise to prosperity and personal fulfillment; immigrants, unable to speak English, can learn the language and acquire education, find employment, marry, buy a home, have children, lead decent lives in safe neighborhoods, vote in democratic elections, and enjoy a comfortable retirement. But the prime place accorded to The Great Gatsby in the literary canon suggests that Americans have known all along that the American Dream is largely myth, ideology, propaganda.

Reading The Great Gatsby is intended, it appears, as an indoctrination in reverse: we require young people to study Fitzgerald’s novel in high school and college courses so they realize, before embarking on their careers, that the American Dream they have heard about and will hear about, is beyond their reach. Even if they fulfill their dreams and gain their desires in material terms, they will not be happy.

When we think in this disenchanted way about The Great Gatsby , published in 1925, we might keep in mind that one of the most influential works of cultural history in this period was Oswald Spengler’s The Decline of the West , two volumes, 1918–1922. In a letter, June 6, 1940, Fitzgerald told Maxwell Perkins, his editor at Scribner’s, that he had read Spengler “the same summer I was writing The Great Gatsby and I don’t think I ever quite recovered from him.”

This could not literally have been the case: Fitzgerald was unable to read German and an English translation only became available in 1926, the year after The Great Gatsby ’s publication. But in the early to mid-1920s, there were articles and essays in English about Spengler that Fitzgerald could have read, and soon thereafter he may have turned to the book itself.

Later in the decade, Time magazine declared: “When the first volume of The Decline of the West appeared in Germany a few years ago, thousands of copies were sold. Cultivated European discourse quickly became Spengler-saturated. Spenglerism spurted from the pens of countless disciples. It was imperative to read Spengler, to sympathize or revolt. It still remains so” (December 10, 1928). Retrospectively, Fitzgerald could have felt that he must have been reading Spengler in 1924–1925 because this German author’s theory of historical degeneration matched the mood that pervades The Great Gatsby .

The Decline of the West is a perplexing, lurid text, imposing in manner, epic in scale, intermittently provocative, tedious as a whole. It is impossible to know which of its many sections seized Fitzgerald, but the pages on “money” are a potent corollary to his inquiry into American wealth: we can imagine Fitzgerald being engaged by them.

Spengler comments on the growth and expansion of the town, the city, and the accumulation and centrality of money there:

As soon as the market has become the town, it is no longer a question of mere centers for streams of goods traversing a purely peasant landscape, but of a second world within the walls, for which the merely producing life “out there” is nothing but object and means, and out of which another stream begins to circle. The decisive point is this—the true urban man is not a producer in the prime terrene sense. He has not the inward linkage with soil or with the goods that pass through his hands. He does not live with these, but looks at them from outside and appraises them in relation to his own life-upkeep…. In place of thinking in goods, we have thinking in money . (Vol. 2, ch. 13; Spengler’s italics)

About the enthralling Daisy Buchanan, Gatsby says, “Her voice is full of money,” to which the narrator Nick Carraway responds, “That was it. I’d never understood before. It was full of money—that was the inexhaustible charm that rose and fell in it, the jingle of it, the cymbals’ song of it” (120; New York: Scribner trade paperback, 2004).

It is not charm alone that money supplies. It also engenders callous indifference; after Gatsby’s death, Nick says about Tom Buchanan and Daisy: “They were careless people, Tom and Daisy—they smashed up things and creatures and then retreated back into their money or their vast carelessness, or whatever it was that kept them together, and let other people clean up the mess they had made” (179).

Wealth has hardened Tom and Daisy. They are careless, heedless, at a secure and indifferent distance from trouble, never facing the necessity to pay attention or minister to others. It is not that they are thoughtless but, rather, that they “think in money.”

About money, Spengler continues:

As the seat of this thinking, the city becomes the money-market, the center of values, and a stream of money-values begins to infuse, intellectualize, and command the stream of goods…. Only by attuning ourselves exactly to the spirit and economic outlook of the true townsman can we realize what they mean. He works not for needs, but for sales, for money. The business view gradually infuses itself into every kind of activity. At the beginning a man was wealthy because he was powerful—now he is powerful because he has money. (Vol. 2, ch. 14)

Tom does and does not fit Spengler’s discourse, for, though wealthy, he has inherited his money: he has no vocation or career and has not made anything. Tom and Daisy are profligate and irresponsible, leading lives that consist, in Nick’s phrase, of being “rich together” (6).

Tom is a formidable physical specimen, as Fitzgerald’s first description of him, through Nick, attests:

He was a sturdy, straw haired man of thirty with a rather hard mouth and a supercilious manner. Two shining, arrogant eyes had established dominance over his face and gave him the appearance of always leaning aggressively forward. Not even the effeminate swank of his riding clothes could hide the enormous power of that body—he seemed to fill those glistening boots until he strained the top lacing and you could see a great pack of muscle shifting when his shoulder moved under his thin coat. It was a body capable of enormous leverage—a cruel body. (7)

Tom inhabits a domineering body; his money is embedded in a proto-fascist mass of muscle. He vents a thuggish cruelty, as when he lashes out at his mistress Myrtle Wilson: “Making a short deft movement, Tom Buchanan broke her nose with his open hand” (37).

Fitzgerald was not a philosopher or cultural historian intent on composing encyclopedic arguments. Wittgenstein, Heidegger, Joseph Campbell, Northrop Frye, Whittaker Chambers, Henry Kissinger: these are among the figures, very different from Fitzgerald, whom Spengler influenced. But it is noteworthy that Fitzgerald sent his letter to Perkins, invoking Spengler, in June 1940. His career was faltering, and his effort to thrive as a Hollywood screenwriter was failing. The nation remained afflicted by the Great Depression’s tough times (unemployment was 15%), and the world was at war, with Hitler on the march across western Europe.

The Dunkirk evacuation was the first week of June. On June 10, the day of Fitzgerald’s letter to Perkins, Mussolini took Italy into the war as an ally of Germany. On this same day, the headline of the New York Times was: “Nazi Tanks Now Within 35 Miles of Paris.” The German army entered Paris on June 14, and France surrendered on June 22.

The literary critic Maureen Corrigan has stated: “ The Great Gatsby is the greatest … Our Greatest American Novel” ( So We Read On: How The Great Gatsby Came To Be and Why It Endures , 2014). Like others, she relates it to the American Dream, to American ideas and categories. Yet so reflexive has this line of response become that it tends to operate at a remove from Fitzgerald’s line-by-line writing. If we aim to understand the rich American resonance of The Great Gatsby , its Spengler-like dimension, and, ultimately, its universal range of reference, its impact on readers all across the globe, we must really read it.

That we should really read The Great Gatsby : this sounds obvious. But do we do it? The Great Gatsby is a book that we assume we already are familiar with, that (so we dimly recall) was assigned to us long ago in high school, that we tell ourselves we must have read. It is akin to Moby-Dick , Uncle Tom’s Cabin , Adventures of Huckleberry Finn , Catch-22, and other books that we know, or know about, even if we are not intimate with them or in fact have not actually read them. What we need to do, is to pause, take a breath, and approach Fitzgerald’s novel as if it were new to us.

For instance, on the first night that Nick attends one of Gatsby’s parties, he and his companion Jordan Baker intersect with “two girls in twin yellow dresses” who had met Jordan a month ago:

“You’ve dyed your hair since then,” remarked Jordan, and I started but the girls had moved casually on and her remark was addressed to the premature moon, produced like the supper, no doubt, out of a caterer’s basket. With Jordan’s slender golden arm resting in mine we descended the steps and sauntered about the garden. A tray of cocktails floated at us through the twilight and we sat down at a table with the two girls in yellow and three men, each one introduced to us as Mr. Mumble. (43)

This passage has the playful exuberance that we associate with Dickens, but it is more concise, subtle, and fleeting in its surreal, fantastical quality. We are invited to imagine the moon emerging like a felicitous treat from one of the caterer’s baskets, and we watch the tray dawdle in the air as if on its own. This is Fitzgerald’s evocation of the magic, unreality, and impossibility of Gatsby’s project to reconnect with Daisy. He gives us a controlled rhythm of sentences that amusingly climaxes with the three-man Mr. Mumble.

After a date with Jordan, Nick returns to his modest house: “When I came home to West Egg that night I was afraid for a moment that my house was on fire. Two o’clock and the whole corner of the peninsula was blazing with light which fell unreal on the shrubbery and made thin elongating glints upon the roadside wires. Turning a corner I saw that it was Gatsby’s house, lit from tower to cellar” (81). Fitzgerald is presenting an ostentatious effect—a house seemingly on fire, the peninsula blazing, and another house lit up from top to bottom. Yet the word “unreal” exposes the illusory nature of the scene. It is amazing and not real, majestic and unnerving testimony to Gatsby’s imagination, to his yearning to journey backward in time so that he can rewrite the narrative of his and Daisy’s lives. Such a keen image: the light sparking “glints,” quick flashes, on the wires.

The next day is the date for the afternoon tea that Nick has arranged for Gatsby’s meeting with Daisy. As always, in Fitzgerald’s description and dialogue there are bewitching phrases and images: “The rain cooled about half-past three to a damp mist, through which occasional thin drops swam like dew” (84). Then, Daisy arrives:

“Is this absolutely where you live, my dearest one?” The exhilarating ripple of her voice was a wild tonic in the rain. I had to follow the sound of it for a moment, up and down, with my ear alone before any words came through. A damp streak of hair lay like a dash of blue paint across her cheek and her hand was wet with glistening drops as I took it to help her from the car. “Are you in love with me,” she said low in my ear. “Or why did I have to come alone?” (85)

Fitzgerald catches the coy theatricality in Daisy’s sense of herself. She knows how flirtatious she is, and she performs her attractiveness for Nick’s enjoyment. It is pleasing to him to observe the performance even as he is aware that Daisy knows (and knows that he knows) that he is not in love with her. At the same time, Daisy’s quickness at producing this impression intimates her fragility, vulnerability, aloneness. Who is Daisy when she is not on stage? Who is she really?

Gatsby, Nick, and Daisy enter and wander through Gatsby’s opulent mansion: “If it wasn’t for the mist we could see your home across the bay,” said Gatsby. “You always have a green light that burns all night at the end of your dock” (92). Green is the color of life, renewal, nature, and energy; it is associated with growth, harmony, freshness, safety, fertility, and the environment. But green is also associated with money, finance, banking, ambition, greed, jealousy, and Wall Street. This duality makes green the appropriate color for the light that Gatsby has gazed at: it has become a symbol for him, at a distance yet clandestinely close, his secret. The mist implies more than Gatsby realizes. Now at last, he is with Daisy. But how clearly is he seeing her?

“Your home”: Gatsby does not register the implications of his words. Tom is a brute, but he is Daisy’s husband, and they have a child. Their luxurious, wasteful lifestyle, and Tom’s addiction to adultery: the cozy connotations of “home” do not flow from this family. But it is a family and they do have a home. This is the structure and history that Gatsby thinks he can blot out.

Fitzgerald’s next lines convey the depletion in Gatsby even as, at this moment, he has Daisy nearby and is making contact with her body:

Daisy put her arm through his abruptly but he seemed absorbed in what he had just said. Possibly it had occurred to him that the colossal significance of that light had now vanished forever. Compared to the great distance that had separated him from Daisy it had seemed very near to her, almost touching her. It had seemed as close as a star to the moon. Now it was again a green light on a dock. His count of enchanted objects had diminished by one. (92-93)

Is Gatsby feeling the self-questioning emotions that Nick attributes to him? “Possibly it had occurred to him”: this brooding reflection on Nick’s part may disclose more about him than it does about Gatsby. Fitzgerald is communicating to us Gatsby’s glamor and Nick’s ambivalent interpretation of it, his projection from himself into the American dreamer whom he scrutinizes with fascination and disapproval.

Then, as the chapter draws to a close, the peculiar Mr. Ewing Klipspringer plays the piano:

In the morning In the evening, Ain’t we got fun— Outside the wind was loud and there was a faint flow of thunder along the Sound. All the lights were going on in West Egg now; the electric trains, men-carrying, were plunging home through the rain from New York. It was the hour of a profound human change, and excitement was generating on the air. One thing’s sure and nothing’s surer The rich get richer and the poor get—children . In the meantime, In between time— (95)

The tune accents the contrast between rich and poor, and combines the intonation of a loud wind and a counter-intuitive, faintly sounding thunder. Fitzgerald gives us once again the imagery of light and electricity, and we hear in Nick’s voice that he is being mesmerized by a romantic, wistful imagination of his own.

Nick then turns to Gatsby, who has on this fateful day reunited with Daisy at last:

As I went over to say goodbye I saw that the expression of bewilderment had come back into Gatsby’s face, as though a faint doubt had occurred to him as to the quality of his present happiness. Almost five years! There must have been moments even that afternoon when Daisy tumbled short of his dreams—not through her own fault but because of the colossal vitality of his illusion. It had gone beyond her, beyond everything. He had thrown himself into it with a creative passion, adding to it all the time, decking it out with every bright feather that drifted his way. No amount of fire or freshness can challenge what a man will store up in his ghostly heart. (95-96)

This sounds dead-on about Gatsby, including his magnitude as a dreamer—the word “colossal” appears a second time. Yet we should ask how much Nick’s response is the result of his own desires, hopes, and doubts. He is a reader as much as we are, a reader of Gatsby who is struggling to understand this fabulously rich man who is captivating and mysterious, at once intriguing and absurd.

Nick reports Gatsby’s thoughts and feelings. Is this perception or, again, is it projection? He sees bewilderment in the face and infers (“as though”) that it signifies Gatsby’s uncertainty. The exclamation “almost five years” tells us what Gatsby and Nick, both of them, are likely to be marveling at. “There must have been,” Nick surmises: this is his interpretation of, his insistence on, the meaning for Gatsby of the reunion with Daisy. Nick says that Gatsby’s dream about her and about himself and her as one, his “illusion,” was so immense that, surely, she must have fallen short of embodying it. “Tumbled” means to fall suddenly and helplessly; a sudden downfall, overthrow, or defeat. This is the verb that Fitzgerald ties to Daisy here, while he connects Gatsby to “thrown himself,” which implies someone who is passionate and, also, out of control, desperate.

“Every bright feather that drifted”—as if Gatsby were so transfixed that he creatively works with the merest wisps that flutter by. “No amount of fire or freshness…”: Fitzgerald could have done without this sentence. It could feel tacked on, a sudden shift from the focus on Gatsby himself. But Fitzgerald deploys the sentence to point to Nick as an interpreter who is stating the lesson that Gatsby’s dream illuminates for Nick himself: “As I watched him he adjusted himself a little, visibly. His hand took hold of hers and as she said something low in his ear he turned toward her with a rush of emotion. I think that voice held him most with its fluctuating, feverish warmth because it couldn’t be over-dreamed—that voice was a deathless song” (96).

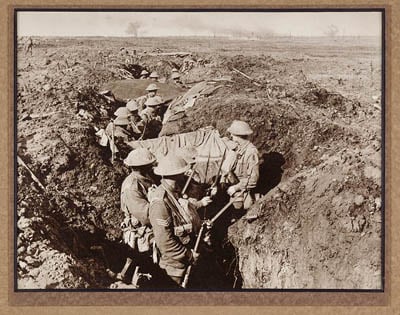

Fitzgerald was an avid reader of poetry, especially Keats and Shelley and others of the Romantic and Victorian periods. Here, he may be alluding to the phrase “deathless song” as Rudyard Kipling uses it in “The Last of the Light Brigade” (1891), which is itself a response to and revision of Tennyson’s “The Charge of the Light Brigade” (1854). Kipling’s poem describes the fate of the neglected survivors: “Though they were dying of famine, they lived in deathless song.” Gatsby served in combat in World War I, carnage and death enveloping him, entranced by the dream of re-crossing the Atlantic to recover Daisy. Nick tells us what he sees as he looks at Gatsby and Daisy, but he cannot hear her words. Fitzgerald could have written, “The voice…,” but instead he writes, “I think that…,” again dramatizing the impact of this moment on Nick, the observer.

Fitzgerald brings the chapter to a close:

They had forgotten me, but Daisy glanced up and held out her hand; Gatsby didn’t know me now at all. I looked once more at them and they looked back at me, remotely, possessed by intense life. Then I went out of the room and down the marble steps into the rain, leaving them there together. (96)

Gatsby and Daisy are reunited; Nick is forgotten, isolated from them, the detail of the falling rain calling attention to his sense of forlorn separateness from them. “Intense life” is a compact expressive term for his perception of this couple’s exhilarating intimacy. It voices the feeling of being alive at the highest degree that dreamers long for, the dream for them becoming incredibly true. This intense life is not in Nick himself. It is in his realization of a vital presence, overwhelming (“a rush of emotion”), miraculous, perhaps too great to be sustained for long, in Gatsby and Daisy. He is on the outside.

When we read The Great Gatsby , we tend to highlight Gatsby and his pursuit of Daisy, and the conflict that arises between him and Tom Buchanan—two wealthy men, each determined to defeat his rival and claim exclusive ownership of the beautiful woman. But Fitzgerald chose a first-person narrator, and, in certain respects, Nick is the most interesting of the novel’s characters.

The action of the story that Nick is telling took place in June–August 1922, and it is now two years later. Much time has passed, and he is back home in the Midwest. We might consider how much we could recall of a stretch of incidents and persons, spanning three months, that occurred two years earlier. How trustworthy would our memory be? Would we be creating—not so much remembering as inventing—as we reached backward in time to recollect our own and others’ words and actions and relationships?

When we really read The Great Gatsby , we should devote attention to Nick, to his dreams (or their absence), and to his social and economic position. Nick, we learn, is a Yale graduate and a veteran of the war. At the outset, his tone is sometimes self-indulgently clever and sarcastic, irritating, even as all the while he—that is, the astute artist Fitzgerald—is revealing his own entitled background and fine fortune.

Nick is not from a very wealthy family, but he is not from a poor one, either:

My family have been prominent, well-to-do people in this middle-western city for three generations. The Carraways are something of a clan and we have a tradition that we’re descended from the Dukes of Buccleuch, but the actual founder of my line was my grandfather’s brother who came here in fifty-one, sent a substitute to the Civil War and started the wholesale hardware business that my father carries on today. (3)

Nick says that the family tradition is that they descend from a line of Scottish peers, a detail that he mentions with irony but that, at the same time, he did not need to mention at all. He has pride in his origins, his status and distinction, which he downplays and is wry about, but which matters to him.

The Carraways were immigrants, generations ago; they are not newly arrived on East coast shores. This is more than a family; in an American context, with its more compressed time-frame, it is a clan, a line. The founder of this family-line must have achieved a measure of success, his American Dream, because when the Civil War threatened him, he had the money to buy an exemption from service in the Union army. He paid a substitute to risk mutilation or death in his place.

After the war, Nick was restless and, unlike the pioneers who journeyed westward, he moved in the opposite direction:

I decided to go east and learn the bond business. Everybody I knew was in the bond business so I supposed it could support one more single man. All my aunts and uncles talked it over as if they were choosing a prep-school for me and finally said, ‘Why ye—es’ with very grave, hesitant faces. Father agreed to finance me for a year and after various delays I came east, permanently, I thought, in the spring of twenty-two. (3)

Nick is somewhat cavalier about turning to the bond business. He is not single-minded or ambitious, not motivated by a burning dream of his own. The fact that everybody he knew was in the bond business tells us about the types of people he and his supportive family are familiar with. Nick then headed East, with a propitious advantage not available to others: his father agreed to finance him for a year.

Periodically, Nick refers to the work he does, the people with whom he interacts, and his attitude toward them:

I knew the other clerks and young bond-salesmen by their first names and lunched with them in dark crowded restaurants on little pig sausages and mashed potatoes and coffee. I even had a short affair with a girl who lived in Jersey City and worked in the accounting department, but her brother began throwing mean looks in my direction so when she went on her vacation in July I let it blow quietly away. (56)

We hear Nick’s distaste as he reports that he consorted with clerks. He had a sexual affair; we do not know anything about it or even the girl’s name—she is only a “girl,” not a woman. Her brother suspected that Nick would take sexual advantage of his sister and then would dispense with her. Nick’s blithe tone of voice implies that indeed he would do something like this. To him, this young woman was merely a fling.

Nick adds that he “took dinner usually at the Yale Club,” an experience he says he did not enjoy. But, nonetheless, he is a member of this club. Further on, Nick says that Jay Gatsby, then James Gatz, had begun his studies at “the small Lutheran college of St. Olaf in southern Minnesota,” but had left it after just two weeks (99). It is not only the very wealthy Tom Buchanan who benefits from privilege, but so does the Ivy League graduate and Yale Club member Nick.

Later, Nick says: “The next April [1920] Daisy had her little girl and they went to France for a year. I saw them one spring in Cannes and later in Deauville and then they came back to Chicago to settle down” (77). Nick has the means to travel abroad and sojourn in resort towns on the French Riviera and in Normandy. He is among the fortunate few.

Nick’s family, then, is prominent and well-to-do. Tom’s family is hugely rich; Daisy’s family has social standing and money. As for Gatsby, born in North Dakota: “His parents were shiftless and unsuccessful farm people—his imagination had never really accepted them as his parents at all” (98). Perhaps this is the trait in Gatsby that for Fitzgerald defines him as an American Dreamer—imagination. It is imagination and tenacity, even ruthlessness, the willingness not only to move beyond one’s origins but also to deny them. The greatest American dreamers say Yes, but their power comes first from saying No.

This is the insight that Fitzgerald, writing during and about the 1920s, establishes and explores. The American Dreamer, as exemplified in the charismatic, crazy Gatsby, strives for success, for self-realization, rushing forward. But this Dream is propelled by the dreamer’s disavowal of his or her past, the refusal to be that person: I cannot accept these parents, this upbringing. Who I am, is intolerable to me, and I will not endure my existence in this paltry life: I will become someone else.

When Fitzgerald in the 1920s was describing Gatsby’s dream, what were the conditions of American life that he witnessed? What was happening all around him?

In the aftermath of the war, the U.S. economy in 1920–1921 had tumbled into a depression, especially in agriculture; the price of wheat plummeted by 50%, and cotton by 75%. The unemployment rate hit 11.7% in 1921. But, in a spectacular turnaround, it dropped to 6.7% by the following year and was down to 2.4% by 1923.

During the 1920s, the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) increased by 40%; annual per capita income did also, rising by 30%. As the scholar Robert A. Divine has noted: “the American people by the 1920s enjoyed the highest standard of living of any nation on earth.” Propelled by commerce, industry, banking, and the stock market, the economy boomed from 1922 t0 1927 at a growth rate of 7% per year. The U.S. accounted for nearly 50% of the world’s industrial output.

Many Americans at last had discretionary income, and, from shrewd marketers, they were receiving nonstop guidance about how to spend it. The historians George B. Tindall & David E. Shi explain: “More people than ever before had the money and leisure to taste of the affluent society, and a growing advertising industry fueled its appetites. By the mid-1920s, advertising had become both a major enterprise with a volume of $3.5 billion [$51 billion today] and a major institution of social control.”

During the spending sprees of the 1920s, Americans could purchase cameras, wrist-watches, washing machines, and much else. From 1922 to 1929, the number of telephones doubled—the word “telephone” occurs nineteen times in The Great Gatsby ; the number of radios increased from 60,000 to 10 million. By 1925, "50 million people a week went to the movies--the equivalent of half the nation's population" (Steven Mintz and Randy Roberts, Hollywood's America , 4th ed., 2010).

Nick and Tom attended Yale. Gatsby spent some weeks at Oxford. Daisy, meanwhile: we hear nothing about her education (which may have been entirely at home, with tutors). She has no interests other than travel and conspicuous consumption and display. The action of the novel takes place in 1922; the 19th amendment, giving women the right to vote, was ratified in August 1920. There is no indication that this means anything to Daisy.

During the 1920s,women began to benefit from greater freedom. Divorce, for example, became easier. In 1880, 1 in every 21 marriages ended in divorce; in 1924, it was 1 in 7. As the historian Irwin Unger has noted, in 1913 a typical woman’s outfit consumed 19.5 yards of cloth; in 1925, it required only seven yards. The ever-increasing popularity of movies and magazines also led to more attention to the right and best types of female behavior and appearance. As another historian, Jane Bailey, has said:

By 1920, hemlines were raised to below the knee; long curls gave way to short “bobbed” haircuts. Pleasure-seeking “flappers” (an English term once applied to prostitutes) drank, danced, and smoked their way through life. The heightened emphasis on female sexuality was not entirely emancipatory, however. As movies and magazines became more popular, standardized ideals of physical attractiveness took root. Sales of cosmetics increased from $17 million in 1914 to $141 million in 1925, as the goal of achieving perpetual youthfulness underwrote a cult of beauty and consumption. Flappers’ rejection of curves led to women binding their breasts and dieting to look boyish. The bathroom scale first appeared on the scene in the 1920s, and cigarette ads targeted women with such slogans as “Reach for a Lucky instead of a sweet.”

Daisy is slender, and she smokes. She also drinks alcohol, though, it seems, not to excess. This is in contrast to Jordan Baker’s account of Daisy’s drunken state on the evening before her marriage to Tom. Too late, Gatsby notified her that he was returning to the United States; by then committed to Tom, she became “drunk as a monkey” (76).

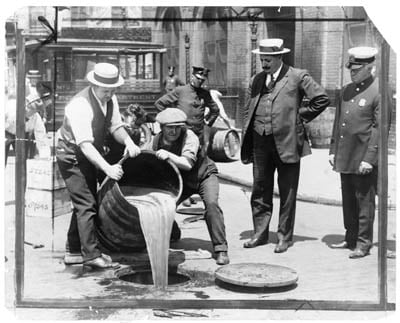

This, in the story, was in June 1919. Prohibition went into effect in 1920: it was illegal to manufacture, transport, or sell alcoholic beverages, and the consumption of alcohol, overall, declined. But drinking was common, and fashionable, for the middle and upper classes; at the expensive Plaza Hotel, Tom takes out a bottle of whiskey, and Daisy offers to make him a mint julep (129). Robert A. Divine points out that “bootleggers annually took in nearly $2 billion [$29.4 billion today], about two percent of the gross national product.” Gatsby is a bootlegger, a criminal: that is how he has amassed his fortune, supplemented by shady financial dealings with the gambler and gangster Meyer Wolfsheim.

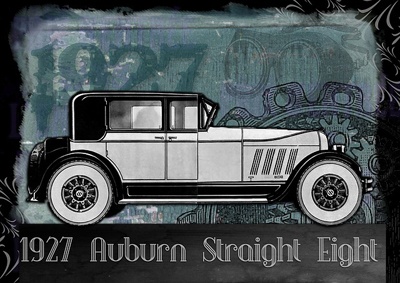

The 1920s also marked the boom of the automobile-industry. Henry Ford had said: “I am going to democratize the automobile. When I’m through everybody will be able to afford one, and just about everyone will have one.” When Ford’s Model T was introduced in the early 1900s, its cost was $1000; in 1927, the cost of the Model A, which replaced the Model T, was $300. By 1929, there were 25 million registered passenger vehicles.

Automobiles abound in Fitzgerald’s book, and Gatsby’s car is the aristocrat among them, a radiant vehicle known to all:

I’d seen it. Everybody had seen it. It was a rich cream color, bright with nickel, swollen here and there in its monstrous length with triumphant hatboxes and supper-boxes and tool boxes, and terraced with a labyrinth of windshields that mirrored a dozen suns. Sitting down behind many layers of glass in a sort of green leather conservatory we started to town. (64)

Tom and Daisy have showy cars—and a chauffeur drives her to the tea at Nick’s where she meets Gatsby (85). Meanwhile, the ineffectual gas-station man George Wilson dreams that Tom will bestow on him a car that the wealthy Buchanans intend to get rid of; he appeals to Tom, reminds him, and in response Tom barks at him in annoyance.

A monument to 1920s’ opulence and excess, there is, furthermore, Gatsby’s prodigious house, to the right of Nick’s place: “The one on my right was a colossal affair by any standard—it was a factual imitation of some Hôtel de Ville in Normandy, with a tower on one side, spanking new under a thin beard of raw ivy, and a marble swimming pool and more than forty acres of lawn and garden” (5). Nick also visits the Buchanan residence:

Their house was even more elaborate than I expected, a cheerful red and white Georgian Colonial mansion overlooking the bay. The lawn started at the beach and ran toward the front door for a quarter of a mile, jumping over sun-dials and brick walks and burning gardens—finally when it reached the house drifting up the side in bright vines as though from the momentum of its run. The front was broken by a line of French windows, glowing now with reflected gold, and wide open to the warm windy afternoon, and Tom Buchanan in riding clothes was standing with his legs apart on the front porch. (6)

Fitzgerald foregrounds Tom’s truculent, conquest-seeking sexuality. Later, we learn that he and Daisy left Chicago for this massive mansion in the East because of one of his sexual escapades (131).

The lifestyles of the rich and famous are maintained by innumerable workers—drivers, cooks, waiters, gardeners, servants. Fitzgerald makes this crucial point often, as here, about Gatsby’s elaborate parties: “Every Friday five crates of oranges and lemons arrived from a fruiterer in New York—every Monday these same oranges and lemons left his back door in a pyramid of pulp- less halves. There was a machine in the kitchen which could extract the juice of two hundred oranges in half an hour, if a little button was pressed two hundred times by a butler’s thumb” (39–40). The butler, dehumanized, depersonalized, has been reduced to a thumb. Gatsby does not give him a thought. This mansion-owner with the Midas touch pays no more heed to his staff’s mind-numbing routines than do the Buchanans.

Fitzgerald perceived that the 1920s economy was making American a new gilded age. At the beginning of the decade, President Warren G. Harding’s principal cabinet member was Secretary of the Treasury Andrew W. Mellon, who cut personal income taxes to a maximum rate of 20%, lowered the estate tax, and repealed the gift tax. He also implemented steep tariffs and slashed federal spending. Loyalists of big business were appointed to regulatory boards and agencies. Corporate profits and stock dividends soared, rising far more rapidly than did the wages of workers.

Speaking in 1928 during his presidential campaign, Herbert Hoover declared: “We in America today are nearer to the financial triumph over poverty than ever before in the history of our land. The poor man is vanishing from us. Under the Republican system, our industrial output has increased as never before, and our wages have grown steadily in buying power.”

Poor people were vanishing because no one was bothering to look for them. Workers were losing power, and labor unions—a force during the era of Eugene V. Debs and the Socialists and International Workers of the World—suffered a falling off in their ranks. The historians Tindall and Shi point out: “Prosperity, propaganda, welfare capitalism [i.e., bonuses, pensions, health and recreational activities in the workplace], and active hostility, combined to cause union membership to drop from about 5 million in 1920 to 3.5 million in 1929.”

Farmers had to deal with unstable prices, deep debts, foreclosures, and bankruptcies. Farm exports fell as agriculture in Europe was restored after the war; farm income in 1919 was 22 billion; in 1929, 13 billion.

What about African Americans? Nick refers to them several times, e.g., “As we crossed Blackwell’s Island a limousine passed us, driven by a white chauffeur, in which sat three modish negroes, two bucks and a girl. I laughed aloud as the yolks of their eyeballs rolled toward us in haughty rivalry” (69). In 1920s New York City, few African Americans were being escorted in limousines with white men as their drivers. Most were sharecroppers in the South, under the sway of white landowners. Falling prices for crops hurt them badly, and for many the 1920s were harsh and unforgiving.

Hundreds of thousands of sharecroppers and other workers lost their jobs during this decade. Many African-Americans in the South migrated northward to New York, Chicago, Detroit, and other cities. They found employment but of an uneven and inadequate kind. Much of the work they did was in the lowest-paying jobs; and they lived in segregated areas, in inferior-quality housing.

As for other groups:

A 1928 report on the condition of Native Americans found that half owned less than $500 and that 71 percent lived on less than $200 a year. Mexican Americans, too, had failed to share in the prosperity. During the 1920s, each year 25,000 Mexicans migrated to the United States. Most lived in conditions of extreme poverty. In Los Angeles the infant mortality rate was five times higher than the rate for Anglos, and most homes lacked toilets. A survey found that a substantial number of Mexican Americans had virtually no meat or fresh vegetables in their diet; 40 percent said that they could not afford to give their children milk. ( Digital American History, University of Houston)

By 1929, the top 1% of the population owned 19% of all personal wealth. The top 5 % owned 34%. Only the top 10 percent owned stocks. This was a decade of extreme income inequality, as Fitzgerald confirms. There are the old money Buchanans, the new money Gatsby, the bond-businessman Nick who is subsidized by his father; and then, on the other hand, there is the floundering, beaten-down George Wilson, and, among many others alongside or lower down from him, the “Finn” who works in Nick’s house as a maid—he never refers to her by name.

In 1929, economists concluded that a family of four needed $2000 per year [$29,000 today] for its basic necessities. Even during this prosperous period, approximately 50% of American families did not reach this level of income. “The top 0.1 percent of American families in 1929 had an aggregate income equal to that of the bottom 42 percent” (Robert S. McElvaine, The Great Depression , 1984).

Also in 1929, the stock market crashed, from 452 in September to 52 in July 1932. Banks failed; farmers lost their lands; factories and mines came to a stop. Investments and savings were wiped out. Farm income fell by 50%. Foreign trade fell by 66%. By 1932, personal income had declined by more than 50 %. Unemployment was 25%. In the automobile industry, production by 1932 fell to 25% of the 1929 total; the number of automobile workers fell to 40% of the 1929 total. By 1931–1932, the average family income had collapsed to $1350 per year. There was no safety net.

For much of the nation, financial prosperity and security were not achievable in the 1920s, and by the 1930s, except for the very fortunate, it had disappeared. So much for the American Dream.

But we should inquire into this American Dream even more, this term to which The Great Gatsby is always linked. For it was in circulation not only during the 1920s, but earlier as well. I have not been able to locate any book that has “American Dream” in its title in the date range 1800 to 1930. From 2000 to the present, by contrast, there are more than one hundred. Still, the phrase does appear in various texts in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, and the implication is that people know what it means.

A notable example is in an editorial in the Montgomery Advertiser , February 1, 1916, urging the nation to be militantly ready and prepared for war: “If the American idea, the American hope, the American Dream, and the structures which Americans have erected, are not worth fighting for to maintain and protect, they were not worth fighting for to establish.”

Zelda Sayre was born in Montgomery, Alabama, in 1900; her father, Anthony Dickinson Sayre (1858–1931), a lawyer, jurist, and Democratic legislator, was appointed in 1909 to the State Supreme Court. I am sure that he read the Montgomery Advertiser ; possibly he perused this editorial on a day when his daughter was at the breakfast table or in the living room with him.

F. Scott Fitzgerald, commissioned as a second lieutenant, met Zelda in Montgomery in July 1918; this is altered slightly, but not significantly, in the novel—Gatsby meets Daisy in August 1917, in Louisville, Kentucky. Fitzgerald hence could feel the fervor of Gatsby’s dream because he had felt it strongly in himself. He craved success as a writer because through it he believed he could win Zelda. His first novel, This Side of Paradise , was published on March 26, 1920; one week later, he and Zelda were married. Age twenty-four, Fitzgerald had obtained the object that had enchanted him.

By the early 1950s, literary critics and scholars were regularly invoking “the American Dream” in relation to The Great Gatsby , as did, for instance, Marius Bewley: “Critics of Scott Fitzgerald tend to agree that The Great Gatsby is somehow a commentary on that elusive phrase, the American Dream. The assumption seems to be that Fitzgerald approved.” To the contrary, says Bewley: “ The Great Gatsby offers some of the severest and closest criticism of the American dream that our literature affords…. The theme of Gatsby is the withering of the American dream” (“Scott Fitzgerald’s Criticism of America,” Sewanee Review , Spring 1954).

The American Dream as aspiration and illusion had gained currency in the aftermath of World War II and from the surge in the economy that boosted consumption in the 1950s. The economy grew during this decade by 37%, and the median American family experienced an increase in purchasing power of 30%. Unemployment was low, inflation was low.

The critic Sarah Churchwell says: “It is not a coincidence that The Great Gatsby began to be widely hailed as a masterpiece in America during the 1950s, as the American dream took hold once more, and the nation was once again absorbed in chasing the green light of economic and material success” ( Careless People: Murder, Mayhem, and the Invention of The Great Gatsby , 2013). Yet Bewley refers to “withering,” implying that the Dream, as portrayed by Fitzgerald, had in some earlier era flowered and flourished but had now shriveled and wizened.

When was this era? The American Dream was not widespread in the 1920s, and it became even more restricted during the Great Depression decade. If there is a single main source for the term, it is James Truslow Adams’s The Epic of America , published in 1931, six years after The Great Gatsby, and two years into the Great Depression, the high times for the fortunate in the 1920s shattered.

Adams (1878–1949), born in Brooklyn, was an excellent student in high school and college, but he faltered in his graduate studies in philosophy and history and found little satisfaction in publishing and finance. While living in New York with his father and sister, Adams began to devote his time and energy to the writing of history, based in primary sources, rendered in an appealing, accessible style. Adams’s three-volume survey of the settlement of New England and its history to 1850 was a major success, and for this project and other books in the 1920s he was widely praised.

Adams based The Epic of America on his conviction that self-improvement and self-formation were the motive forces in American history. Adams maintains that there has always been:

… the American dream , that dream of a land in which life should be better and richer and fuller for every man, with opportunity for each according to his ability or achievement. It is a difficult dream for the European upper-classes to interpret adequately, and too many of us ourselves have grown weary and mistrustful of it. (Adams’s italics)

He continues: “It is not a dream of motor cars and high wages merely, but a dream of a social order in which each man and each woman shall be able to attain to the fullest stature of which they are innately capable, and be recognized by others for what they are, regardless of the fortuitous circumstances of birth or position.”

Adams states that the American Dream is more than money and materialism:

No, the American dream that has lured tens of millions of all nations to our shores in the past century has not been a dream of merely material plenty, though that has doubtless counted heavily. It has been much more than that. It has been a dream of being able to grow to fullest development as man and woman, unhampered by the barriers which had slowly been erected in older civilizations, unrepressed by social orders which had developed for the benefit of classes rather than for the simple human being of any and every class. And that dream has been realized more fully in actual life here than anywhere else, though very imperfectly even among ourselves.

It has been a magnificent epic and dream, Adams affirms. But he then asks, what about the American Dream at present and in the future?

If the American dream is to come true and to abide with us, it will, at bottom, depend on the people themselves. If we are to achieve a richer and fuller life for all, they have got to know what such an achievement implies. In a modern industrial State, an economic base is essential for all. We point with pride to our “national income,” but the nation is only an aggregate of individual men and women, and when we turn from the single figure of total income to the incomes of individuals, we find a very marked injustice in its distribution.

The concern that Adams expresses is about income inequality—he saw it in the 1920s, and again in the Great Depression decade. In this same year, 1931, looking backward, Fitzgerald wrote in an essay, “Echoes of the Jazz Age”:

It ended two years ago, because the utter confidence which was its essential prop received an enormous jolt, and it didn’t take long for the flimsy structure to settle earthward. And after two years the Jazz Age seems as far away as the days before the War. It was borrowed time anyhow—the whole upper tenth of a nation living with the insouciance of grand dukes and the casualness of chorus girls. But the moralizing is easy now and it was pleasant to be in one’s twenties in such a certain and unworried time.

The upper tenth troubles Adams too, as he declares in a verdict that applies to the 1920s, the 1950s—and to where we are in the twenty-first century:

There is no reason why wealth, which is a social product, should not be more equitably controlled and distributed in the interests of society. A system that steadily increases the gulf between the ordinary man and the super-rich, that permits the resources of society to be gathered into personal fortunes that afford their owners millions of income a year, with only the chance that here and there a few may be moved to confer some of their surplus upon the public in ways chosen wholly by themselves, is assuredly a wasteful and unjust system. It is, perhaps, as inimical as anything could be to the American dream.

Nick says about the very rich American Dreamer Gatsby: “He wanted nothing less of Daisy than that she should go to Tom and say: ‘I never loved you’. After she had obliterated four years with that sentence they could decide upon the more practical measures to be taken” (109). Gatsby wanted money, an immense amount of it, which he procures by lawless means, so that he can capture Daisy, who represents for him privilege and status. “Obliterate”: to remove utterly from recognition or memory; to remove from existence; to destroy utterly all trace, indication, or significance. It never occurs to Gatsby to consider whether Daisy, herself, wants to participate in his dream. He assumes that she does—and that she will immediately erase the fact that she has been and is married to Tom and is the mother of a child.

Gatsby is blinded by his dream, and by money and the potency he believes that it gives him. At one point, in front of Nick and Jordan Baker, Daisy “got up and went over to Gatsby and pulled his face down, kissing him on the mouth.” She murmurs: “You know I love you” (116). But for Gatsby this will not suffice. He will not allow Daisy to say that she once loved Tom but now loves him. He commands her to negate the person she was, a person with a past and a memory of it. The money that Gatsby has, and the magnitude of his hyperbolic purchases, should prove to her, so Gatsby presumes, that he loves her and that she should join him in the story-line of their lives than he has constructed.

Gatsby does feel apprehension when Daisy seems not to be falling into exact conformity with his image of her, to which Nick replies:

“I wouldn’t ask too much of her,” I ventured. “You can’t repeat the past.” “Can’t repeat the past?” he cried incredulously. “Why of course you can!” He looked around him wildly, as if the past were lurking here in the shadow of his house, just out of reach of his hand. “I’m going to fix everything just the way it was before,” he said, nodding determinedly. “She’ll see.” (110)

Nick warns Gatsby about the impossibility of this ultimatum, this imposition on Daisy. But Nick does not formulate his point in quite the correct terms—and Gatsby does not discern the misleading nature of both Nick’s words and his own incredulous reply. Gatsby does not want to “repeat” the past. His intention is not that at all. It is through money and rhetoric to obliterate the past, to write a new history on a blank page, as though the one there before had never existed. Why not? If you have the money, you can do anything.

Fixing everything the way it was before: this links Gatsby to Meyer Wolfsheim, who “fixed the World Series” in 1919 (73). It is criminal to recreate another person in the coercive manner that Gatsby is committed to. Fitzgerald intends for us to recognize that for Gatsby “the way it was before” is not his dream. His dream is to make it the way it was not: he hates his past, and his money is his guarantee that he can dispense with the person he was and invite—that is, order—Daisy to do the same.

Nick breaks from this dialogue to reflect on Gatsby’s obsession: “He talked a lot about the past and I gathered that he wanted to recover something, some idea of himself perhaps, that had gone into loving Daisy. His life had been confused and disordered since then, but if he could once return to a certain starting place and go over it all slowly, he could find out what that thing was...” (110; Fitzgerald’s ellipsis). Nick’s story is entwined with Gatsby’s. Often it is difficult to know when Nick is giving us an accurate impression of Gatsby and when he is speculating about him.

Nick next proceeds to stage and paint the scene of Gatsby’s remembered vision of his momentous time with Daisy:

…One autumn night, five years before, they had been walking down the street when the leaves were falling, and they came to a place where there were no trees and the sidewalk was white with moonlight. They stopped here and turned toward each other. Now it was a cool night with that mysterious excitement in it which comes at the two changes of the year. The quiet lights in the houses were humming out into the darkness and there was a stir and bustle among the stars. Out of the corner of his eye Gatsby saw that the blocks of the sidewalk really formed a ladder and mounted to a secret place above the trees—he could climb to it, if he climbed alone, and once there he could suck on the pap of life, gulp down the incomparable milk of wonder. (110; Fitzgerald’s ellipsis)

Fitzgerald heightens Nick’s language, imbuing it with romance, melodrama, and phantasmagoric sublimity. This is far beyond anything that Gatsby could articulate. It is sumptuous and strained, lavish and ridiculous: Nick is appalled and seduced by the wealth-laden Gatsby’s effort to incarnate his Daisy-inspired imagination.

Fitzgerald returns to this scene when Nick once more tells the reader about Gatsby’s first experiences of Daisy. He says that Gatsby said: “She was the first ‘nice’ girl he had ever known. In various unrevealed capacities he had come in contact with such people but always with indiscernible barbed wire between. He found her excitingly desirable” (148). An acute phrase: the “barbed wire” visible yet indiscernible, not to be seen. It is oracular for Gatsby, who would take part in the Argonne offensive in France (66), one of the deadliest battles in U.S. military history, where there were labyrinthine networks of barbed wire in the killing zones.

To pre-war Gatsby, Daisy is not only desirable but excitingly so: she arouses, stirs, stimulates him. She amplifies desire: “He went to her house, at first with other officers from Camp Taylor, then alone. It amazed him—he had never been in such a beautiful house before. But what gave it an air of breathless intensity was that Daisy lived there—it was as casual a thing to her as his tent out at camp was to him” (148). There is more here about the house than about Daisy; it is not her, but the house to which Gatsby (according to Nick) attached the word “beautiful.”

This is where Daisy lives, but the antecedent for “it” is “house”—that is, while Daisy is special, it is the house itself that has “breathless intensity”: “There was a ripe mystery about it, a hint of bedrooms upstairs more beautiful and cool than other bedrooms, of gay and radiant activities taking place through its corridors and of romances that were not musty and laid away already in lavender but fresh and breathing and redolent of this year’s shining motor cars and of dances whose flowers were scarcely withered” (148). Nothing about Daisy’s appearance, not anything directly about her at all. The word “beautiful” reappears, but again not in reference to her but to the house.

Nick then returns to Daisy: “It excited him too that many men had already loved Daisy—it increased her value in his eyes. He felt their presence all about the house, pervading the air with the shades and echoes of still vibrant emotions’ (148). Later, Gatsby will insist that Daisy obliterate, wipe out (109, 132), her relationship with Tom. But at this initial stage, her value to Gatsby is increased because other young men have loved her. They confirm the rightness of Gatsby’s desire for her, intensifying it.

The next passage takes us to the climax of Gatsby’s pursuit:

But he knew that he was in Daisy’s house by a colossal accident. However glorious might be his future as Jay Gatsby, he was at present a penniless young man without a past, and at any moment the invisible cloak of his uniform might slip from his shoulders. So he made the most of his time. He took what he could get, ravenously and unscrupulously—eventually he took Daisy one still October night, took her because he had no real right to touch her hand. (149)

Gatsby is pretending to Daisy to be someone he is not. In army uniform—another marvel, the cloak that is invisible—all of the officers are the same. Gatsby can represent himself to Daisy as better in status than he really is. Deceiving her, he is playing a role; he knows (she does not know) who he is—the offspring of shiftless, unsuccessful parents whom he has repudiated.

What makes the passage shocking is that, having deceived Daisy, Gatsby “takes” her sexually. He takes her, he took her; two lines later Fitzgerald repeats, “he had certainly taken her.” Nick’s account makes this sexual consummation not a loving one but an assault, a molestation, or worse. “Ravenously” implies extreme hunger, being famished, voracious like a beast, intensely eager for gratification or satisfaction. “Unscrupulously”: without scruples, without conscience, unprincipled. Is this love? If it is, it is expressed as if it were theft, a trespass, an act of resentment, of hate and self-hatred. Fitzgerald could have written the passage differently, or not included it at all. This is what he wanted.

When Gatsby, his “taking” done, separates from Daisy, “She vanished into her rich house, into her rich, full life leaving Gatsby—nothing. He felt married to her, that was all” (149). He feels married to her: it is hard to know what this means. For the main impression is one of coercion and grievance, of sexual violation. Gatsby desires Daisy. Or, should we say that he despises her?—despises the socially privileged and wealthy? Gatsby knows that Daisy does not know who he is and would rebuff him if she did. His interaction with her has left him feeling cancelled out, null and void.

“When they met again,” says Nick:

two days later it was Gatsby who was breathless, who was somehow betrayed. Her porch was bright with the bought luxury of star-shine; the wicker of the settee squeaked fashionably as she turned toward him and he kissed her curious and lovely mouth. She had caught a cold and it made her voice huskier and more charming than ever and Gatsby was overwhelmingly aware of the youth and mystery that wealth imprisons and preserves, of the freshness of many clothes and of Daisy, gleaming like silver, safe and proud above the hot struggles of the poor. (149-150)

Gatsby, objectifying Daisy, values her silvery presence for its distance from futile poverty where dreams never come true. She is preserved in her wealth; she is imprisoned too, but the implication is that Gatsby, by uniting himself to her, will liberate her along with himself. This is an impossible dream, as somewhere in his mind Gatsby is aware. Daisy is captivating but sullied in his eyes: he has tainted her by taking her.

In a startling juxtaposition, Fitzgerald passes from Nick’s description to Gatsby’s own colloquial speech:

“I can’t describe to you how surprised I was to find out I loved her, old sport. I even hoped for a while that she’d throw me over, but she didn’t, because she was in love with me too. She thought I knew a lot because I knew different things from her.... Well, there I was, way off my ambitions, getting deeper in love every minute, and all of a sudden I didn’t care. What was the use of doing great things if I could have a better time telling her what I was going to do?” (150)

Gatsby is acknowledging that, for him, the American Dream is better talked about than experienced: he could have done great things but what is even better is the prospect of telling Daisy that he will do them in the future. It might be better for Gatsby never to do them, because if they were done, it would no longer be possible to talk about them, anticipate them, look forward to them. Gatsby may realize that if he did great things, these would not make him happy. Not doing them means not being disappointed.

In the screenplay for his film adaptation of The Great Gatsby , 2013, Baz Luhrmann revises the dialogue of this scene. Gatsby says: “I knew it was a great mistake for a man like me to fall in love. A great mistake. I’m only 32…. I might still be a great man if I could only forget that I once lost Daisy. But my life, old sport, my life has got to be like this… He draws a slanting line from the lawn to the stars. ” Luhrmann is bringing out, putting into words, an insight into Gatsby that Fitzgerald glances at. Gatsby reveals that he knows the mistake he made; in two senses, it is a “great” mistake. There is time for him to choose a different direction. Money is not everything and neither is Daisy, But Gatsby cannot make this choice: he cannot forget that he lost Daisy. Does he want to possess her because he desires her, or does he desire her because he lost her?

Fitzgerald’s exposition of, and inquiry into, the American Dream, undertaken in 1925, is psychologically complex, written in a suspenseful first-person form full of twists and turns, flash-forwards and flash-backs. Fitzgerald criticizes delusion and illusion, yet from first to final page, his craftsmanship, his adroit literary language, is subtle and sensitive. He pays tribute to the American Dream that he discredits, and we remain wedded to it.

On the campaign train in Iowa, 2007, Barack Obama celebrated the American Dream:

As I’ve traveled around Iowa and the rest of the country these last nine months, I haven’t been struck by our differences—I’ve been impressed by the values and hopes that we share. In big cities and small towns; among men and women; young and old; black, white, and brown—Americans share a faith in simple dreams. A job with wages that can support a family. Health care that we can count on and afford. A retirement that is dignified and secure. Education and opportunity for our kids. Common hopes. American dreams.

Obama said that he, his grandparents, and other family members had achieved this dream, but that many Americans were now finding their hopes for it to be unfulfilled: “While some have prospered beyond imagination in this global economy, middle-class Americans—as well as those working hard to become middle class—are seeing the American dream slip further and further away.”

“You know it from your own lives,” Obama continued: Americans are working harder for less and paying more for health care and college. For most folks, one income isn’t enough to raise a family and send your kids to college. Sometimes, two incomes aren’t enough. It’s harder to save. It’s harder to retire. You’re doing your part, you’re meeting your responsibilities, but it always seems like you’re treading water or falling behind. And as I see this every day on the campaign trail, I’m reminded of how unlikely it is that the dreams of my family could be realized today.

Obama told his audience—this was the basis for his campaign: “I don’t accept this future. We need to reclaim the American dream.” During his two terms, 2008–2016, how well did President Obama perform in his effort to restore and reanimate the American Dream?

In a study published in late 2014, Emmanuel Saez and Gabriel Zucman concluded: “The share of wealth held by the top 0.1 percent of families is now almost as high as in the late 1920s, when The Great Gatsby defined an era that rested on the inherited fortunes of the robber barons of the Gilded Age.” They noted:

The flip side of these trends at the top of the wealth ladder is the erosion of wealth among the middle class and the poor…. The growing indebtedness of most Americans is the main reason behind the erosion of the wealth share of the bottom 90 percent of families. Many middle class families own homes and have pensions, but too many of these families also have much higher mortgages to repay and much higher consumer credit and student loans to service than before. (“Exploding Wealth Inequality in the United States,” Washington Center for Equitable Growth , October 20, 2014)

Preparing in 2014 for her presidential campaign, Hillary Clinton said: “We have to do a better job of getting our economy growing again and producing results and renewing the American Dream so Americans feel they have a stake in the future and that the economy and political system is not stacked against them.” She had served as Obama’s secretary of state from 2009 to 2013; her promise to renew the American Dream thus amounted to a critique of the administration that she had been part of.

From 2000-01 to 2014–15, Hillary and Bill Clinton made more than $150 million in lecture fees; in total, during these fifteen years after he left the White House, they made $240 million. They led (and continue to lead) luxurious lives; they have a charitable foundation worth many millions; and their net worth (estimates vary) is somewhere in the $120 million range.

Money “has always been passed down in families”—as Fitzgerald shows through Tom Buchanan—“but today, across America, parents who can are helping their grown children in unprecedented ways” (Jen Doll, Harper’s Bazaar , February 12, 2019). Since 2001, the Clintons’ daughter Chelsea has served as a member of the corporate board of IAC/InteractiveCorp, a media and investment company: she has received $9 million in compensation. She has one qualification for this position: her parents. Her wedding in 2010 cost $2 million; for their New York City condo, she and her husband paid $10.5 million; they have a net worth in excess of $30 million.

Hillary Clinton lost the election in 2016 to Donald Trump, net worth, $3.7 billion, who had launched his campaign in June 2015 with a speech that concluded:

Trump : Sadly, the American dream is dead. Audience member : Bring it back. Trump : But if I get elected president I will bring it back bigger and better and stronger than ever before, and we will make America great again.

During President Trump’s term, from 2016 forward, the numbers for growth, employment, and the stock market have been positive. Vice President Mike Pence said, April 10, 2019, that the American dream was “dying until President Donald Trump was inaugurated” in 2017. Trump’s policies are generating jobs “at the fastest pace of all,” Pence emphasized, and this “gives evidence of the fact that the American dream is coming back.” “Was the American dream in trouble? You bet,” Pence said in an interview: “I really do believe that’s why the American people chose a president whose family lived the American dream and was willing to go in and fight to make the American dream available for every American” ( CNBC , April 11, 2019).

Donald Trump Jr. has said: “For the last 50 years our biggest net export has been the American Dream, but because of Donald Trump we’ve brought that American Dream home, where it belongs” (June 25, 2019). Eric Trump, the second of the President’s sons, echoes this claim: “We have achieved something that was incredible and something that is so much bigger than what we are and it shows that the American dream is alive and under him I think the American dream is going to be stronger than it was ever before” ( FOX Business , September 30, 2019).

On the other hand: In late 2019, the Census Bureau reported: “The gap between the richest and the poorest U.S. households is now the largest it has been in the past 50 years.” “The most troubling thing about the new report,” states the economist William M. Rodgers III, is that it “clearly illustrates the inability of the current economic expansion, the longest on record, to lessen inequality” (Bill Chappell, “U.S. Income Inequality Worsens, Widening To A New Gap,” NPR , September 26, 2019).

As for the record-setting stock market: in 2008, 62% of Americans owned stock; in 2020, 55% do. This means that nearly half of the nation owns no stock—no mutual funds, no retirement funds. The top 10% of families with the highest income own, on average, $969,000 in stocks. Among low-income workers, 92% of them do not have a retirement account or cannot afford to contribute to one. (Allison Schrager, Quartz , September 5, 2019; Gallup News , September 13, 2019.)

The authors of a report published in 2019 conclude:

We live in an age of astonishing inequality. Income and wealth disparities in the United States have risen to heights not seen since the Gilded Age and are among the highest in the developed world. Median wages for U.S. workers have stagnated for nearly fifty years. Fewer and fewer younger Americans can expect to do better than their parents. Racial disparities in wealth and well-being remain stubbornly persistent. In 2017, life expectancy in the United States declined for the third year in a row, and the allocation of healthcare looks both inefficient and unfair. Advances in automation and digitization threaten even greater labor market disruptions in the years ahead. (“Forum on Economics After Neoliberalism,” Boston Review , February 15, 2019)

Nevertheless, we dream on. In Orlando, Florida, June 18, 2019, President Trump announced his bid for reelection:

Our country is now thriving, prospering and booming. And frankly, it’s soaring to incredible new heights. Our economy is the envy of the world, perhaps the greatest economy we’ve had in the history of our country. And as long as you keep this team in place, we have a tremendous way to go. Our future has never ever looked brighter or sharper. The fact is, the American Dream is back, it’s bigger and better, and stronger than ever, before.

In 2019, 25% of American workers made less than $10 per hour. This places their income for the year below the federal poverty level. Overall, “the number of people earning less than $30,000 accounts for 46.5 percent of the population.” During the next five years, the job most in-demand, which will rise 47%, is home health-aide. Its median salary is $23,210.

The reporter/journalist Jeanna Smialek observes that “unequal access to opportunities is now a global story. Barriers vary by country, but children are generally more likely to earn incomes similar to their parents’ in nations with higher income inequality.” She comments further: “the graph of this relationship is often called a Great Gatsby Curve , named after F. Scott Fitzgerald’s novel about social mobility and its costs.” The United States is “further toward the high-inequality, high-immobility end of the scale than other advanced economies.”

In the United States, says Smialek, “higher income-inequality goes hand in hand with lower upward-mobility,” and she cites research by the economists Raj Chetty, Nathaniel Hendren, and others. Hendren observes: “It just speaks to this kind of question: To what extent are we a country where kids have a notion of the American dream?” ( Bloomberg Business Week , March 20, 2019; see also John Jerrim and Lindsey Macmillan, “Income Inequality, Intergenerational Mobility, and the Great Gatsby Curve: Is Education the Key?,” Social Forces , December 2015).

Senator Bernie Sanders has spoken about the American Dream. In 2014, on the Senate floor, he asked, “What happened to the American Dream?”, and he replied, “we are now the most unequal society” among all of the industrial nations. In his campaign for the 2016 nomination, Sanders emphasized the crisis of income inequality, and he is emphasizing it even more. The son of Jewish immigrants, a member of a family that struggled to pay the bills, Sanders through hard work and education made it all the way to the U.S. Senate; he now is “attempting to identify his own personal story with the American Dream”, a dream that, he contends, fewer and fewer Americans can hope to achieve (Walter G. Moss, LA Progressive, March 30, 2019).

On his campaign www-site, Joe Biden also presents himself as an embodiment of and proponent for the American Dream:

During my adolescent and college years, men and women were changing the country—Martin Luther King, Jr., John F. Kennedy, Robert Kennedy—and I was swept up in their eloquence, their conviction, the sheer size of their improbable dreams…. America is an idea that goes back to our founding principle that all men are created equal. It’s an idea that’s stronger than any army, bigger than any ocean, more powerful than any dictator. It gives hope to the most desperate people on Earth. It instills in every single person in this country the belief that no matter where they start in life, there’s nothing they can’t achieve if they work at it.

So too does Senator Elizabeth Warren, and she has a proposal for reducing the inequality gap:

I’ve got plans to put the American Dream within reach for America’s families—and a plan to pay for it with a two-cent wealth tax. A two-cent tax on fortunes of more than $50 million – the wealthiest 0.1% -- can bring in the revenue we need to invest in universal child-care, public education, universal tuition-free public college and student debt cancellation for 95% of people who have it…. Education was my ticket to live my dreams, and it’s time we make that opportunity available to every family who wants it. ( Concord Monitor , November 13, 2019)

Those at the top, the wealthiest Americans: they are the most alarmed critics of the Sanders and Warren positions and proposals. Hedge-fund manager Leon Cooperman, for instance, wailed about Warren’s intention to set new rules for Wall Street: “This is the fucking American Dream she is shitting on” ( Politico , October 23, 2019). More temperately, he said: “Let’s elevate the dialogue and find ways to keep this a land of opportunity where hard work, talent, and luck are rewarded and everyone gets a fair shot at realizing the American Dream.” Cooperman’s net worth is $3.2 billion.

Critics of a tax increase on the very rich and of regulation that might lessen income inequality: these worried voices include Michael Bloomberg (net worth, $56.4 billion) and Jeff Bezos (net worth in 2010, $12.3 billion; in 2019, net worth, $116 billion—the remainder after his wife received $36 billion in their divorce settlement). The sports merchandise executive Michael Rubin (net worth, $2.9 billion) contends that boosting taxes on the super-rich “would have the exact opposite effect of what you want to happen…. What makes America great is that this is a true land for the entrepreneur…. What would happen is that people won’t start businesses here anymore” ( Yahoo Finance , January 9, 2020).

Mark Cuban (net worth, $4.1 billion) weighs in: “I love entrepreneurship because that’s what makes this country grow. And if I can help companies grow, I’m setting the foundation for future generations. It sends the message that the American dream is alive and well” ( CNBC , March 24, 2018). Cuban endorsed Hillary Clinton in 2016 as the best advocate of (his phrase) “the American Dream.” She says that she is in favor of an estate tax, but as for a tax increase aimed at the very wealthy (like herself), she asserts that this would be “incredibly disruptive” ( Daily Beast , July 31, 2016; Business Insider , November 7, 2019).

In 2019, the world’s 500 wealthiest people added $1.2 trillion to their fortunes, increasing their collective net worth 25%, to at least $5.9 trillion. The twenty-six people at the top possess greater wealth than the 3.8 billion people in the bottom half of the world’s population. In the United States, there are 600+ billionaires.

In a report, January 2020, Oxfam focused on this vast disparity and concluded: “Extreme wealth is a sign of a failing system. Governments must take steps to radically reduce the gap between the rich and the rest of society and prioritize the well-being of all citizens over unsustainable growth and profit.”

In the same month, many of the attendees at the World Economic Forum, “the most concentrated gathering of wealth and power on the planet,” at their meeting in Davos, Switzerland, expressed a similar concern. Kristalina Georgieva, Managing Director of the International Monetary Fund, said: “The beginning of this decade has been eerily reminiscent of the 1920s.” In a report that was prepared for this meeting, the United States is at #27 in the world’s social mobility index, behind, e.g., Germany, France, Canada, Japan, and the United Kingdom. One observer remarked: “Canadians have a better shot at the American Dream than Americans do.” (Chloe Taylor, CNBC , January 19, 2020; Heather Long, Washington Post , January 20, 2020; Hanna Ziady, CNN Business , January 20, 2020.)

Among Americans, 61% say that there “is too much economic inequality.” For young people, ages 18 to 29, the figure rises to more than 70%. If there is a surprise in the polling, it is that only 40+ percent say that reversing income inequality should be a “top priority.” But the priorities they do emphasize, such as “creating affordable health care, fighting drug addiction, making college more affordable, fixing the federal budget deficit, and solving climate change”—all of these are connected to economic policy. People recognize this—which is why nearly 60% believe that the very wealthy should pay more in taxes ( CNBC , January 9, 2020; NPR , January 9, 2020).

Economists have demonstrated that inequality is higher today than it has been since the 1920s, the decade of The Great Gatsby. In Forbes magazine, for example, Jesse Colombo writes: “It’s not fashionable to wear flapper dresses and do the Charleston, but 1920s-style wealth inequality is definitely back in style. America’s ultra-rich haven’t held as much of the country’s wealth since the Jazz Age” (February 28, 2019). Here are the conclusions presented in recent studies of the American Dream: