Narrative Medicine: Every Patient Has a Story

Learning to empathize

Rita Charon, MD, PhD, executive director of Columbia’s Program in Narrative Medicine, is widely recognized as the originator of the field. “The effective practice of medicine requires narrative competence, that is, the ability to acknowledge, absorb, interpret, and act on the stories and plights of others,” Charon wrote in a 2001 article in JAMA .

“It’s not a stretch to say we need help to look at our own processes or to see and appreciate what patients are telling us. For me, it became a way for patients to feel heard and noticed,” Charon said of her early experiences integrating narrative skills into her clinical practice. “It’s a commitment to understanding patients’ lives, caring for the caregivers, and giving voice to the suffering.”

A core component of narrative medicine education is “close reading,” or learning how to thoughtfully and critically analyze a text. This approach helps students develop empathetic listening skills to better understand and connect with patients. Today, all Columbia medical students are exposed to narrative medicine in their first years, when they’re required to take one of 14 seminars on topics ranging from memoir writing to visual arts to medical journalism. The medical school also offers a fourth-year elective for medical students, as well as a scholarly track in Narrative and Social Medicine that Charon also directs.

While Columbia University is the only school with a graduate degree in narrative medicine, many medical schools have followed its lead, offering a variety of courses and seminars.

At the University of Nevada, Reno (UNR) School of Medicine, medical students can take narrative medicine as a scholarly concentration or as a fourth-year elective. Assignments include 10,000 words of reflective writing on clinical encounters that students must submit to a medical humanities publication. Susan Palwick, PhD, who teaches narrative medicine at UNR, said most students are drawn to write personal essays, though many try their hand at fiction and poetry as well.

“It’s easy for patients to get reduced to a specific illness. Narrative medicine is a way of integrating everything back together; it’s a way of staying curious about people.” Susan Palwick, PhD University of Nevada, Reno School of Medicine

“It’s easy for patients to get reduced to a specific illness,” said Palwick, an associate professor of English and adjunct professor in UNR’s Office of Medical Education. “Narrative medicine is a way of integrating everything back together; it’s a way of staying curious about people. Ultimately, it’s a form of love.”

She said the experience can help students unpack their biases, too. For instance, Palwick said a student who was feeling particularly judgmental of patients undergoing bariatric surgery decided to write a series of vignettes imagining why such patients struggle with their weight and why they can’t lose it without the help of surgery. The process, Palwick discovered, “helps you stay empathetic and sympathetic."

Reflective writing also provides a “safe space” for students to discuss the stresses of medical school and their professional fears, she added.

Jake Measom, a fourth-year medical student at UNR, said that participating in the narrative medicine scholarly concentration has pushed him to be more creative in his approach to patient care. He also sees narrative medicine as a “remedy to burnout,” noting that while the practice of medicine can sometimes feel monotonous, narrative medicine reminds him that “there’s a story to be had everywhere.”

“It not only makes me a better physician in the sense of being able to listen better and be more compassionate,” he said, “it also helps you gain a better understanding of who you are as a person.”

Storytelling as a means of coping

“ First you get your coat. I don’t care if you don’t remember where you left it, you find it. If there was a lot of blood, you ask someone to go quickly to the basement to get you a new set of scrubs. You put on your coat and you go into the bathroom. You look in the mirror and you say it. You use the mother’s name and you use her child’s name. You may not adjust this part in any way.”

That’s an excerpt from “How to Tell a Mother Her Child Is Dead,” which was published last September in the New York Times in the Sunday Review Opinion section. Authored by Naomi Rosenberg, MD, a physician at Temple University Hospital, the piece is a heart-wrenching example of how narrative medicine can serve as an outlet for coping with the harrowing experiences that providers regularly encounter.

Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Michael Vitez encouraged Rosenberg to submit the piece in his new role as director of narrative medicine at Temple University Lewis Katz School of Medicine. After retiring from a 30-year career as a reporter at the Philadelphia Inquirer , Vitez approached the school’s dean about using his skills to help students, faculty, and patients translate their experiences into words. The idea morphed into Temple’s new Narrative Medicine Program, which launched in 2016.

Currently, the Temple program is fairly unstructured, with students and faculty working one-on-one with Vitez on their narrative pieces. For example, Vitez said a third-year medical student recently sent him a poem she wrote after an especially difficult day in her psychiatric rotation: “It helped her process her emotions and turn a really bad day into something really valuable,” he noted. Eventually, Temple hopes to offer a certificate and master’s degree in narrative medicine.

“I believe that stories have an incredible power,” said Vitez. “Understanding what a good story is and learning how to interview and ask questions will help you connect with your patients, understand them, and build relationships with them.”

Jay Baruch, MD, associate professor of emergency medicine at Brown’s Warren Alpert Medical School and faculty advisor to the narrative medicine course there, likewise maintains that the type of creative thinking often associated with the arts and humanities—and that narrative medicine often promotes—deserves a more central role in medical education.

“[Students and physicians] need to know the anatomy of a patient’s story just as much as the anatomy of the human body,” he said.

- Health Care

- Medical Schools

Home — Essay Samples — Nursing & Health — Childhood Obesity — Importance Of Good Health

Importance of Good Health

- Categories: Childhood Obesity

About this sample

Words: 649 |

Published: Mar 14, 2024

Words: 649 | Page: 1 | 4 min read

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Verified writer

- Expert in: Nursing & Health

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

3 pages / 1163 words

5 pages / 2053 words

5 pages / 2799 words

13 pages / 5869 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Childhood Obesity

Buzzell, L. (2019, August 13). Benefits of a Healthy Lifestyle. Johns Hopkins Medicine. https://www.healthline.com/health/healthy-eating-on-a-budget#1.-Plan-meals-and-shop-for-groceries-in-advance

Obesity in children in the US and Canada is on the rise, and never ending because new parents or parents with experience, either way tend to ignore what is happening with their child. A study at UCSF tells us that “A child with [...]

In today's modern society, the issue of childhood obesity has become an alarming concern. As the rates continue to rise at an unprecedented pace, it is imperative that we address this issue with urgency and determination. One [...]

With obesity rates on the rise, and student MVPA time at an all time low, it is important, now more than ever, to provide students with tools and creative opportunities for a healthy and active lifestyle. A school following a [...]

Throughout recent years obesity has been a very important topic in our society. It has continued to rise at high rates especially among children. This causes us to ask what are the causes of childhood obesity? There are many [...]

It is well known today that the obesity epidemic is claiming more and more victims each day. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention writes “that nearly 1 in 5 school age children and young people (6 to 19 years) in the [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

- Recommended

Medical journals that accept stories and essays from physicians

Health and health care are hot topics lately, and not just for journalists and bloggers debating Obamacare. Suddenly – or so it seems; in fact the trend has been building for years – people from all walks of life want to read about medicine.

Within medicine, a majority of journals now have essay, viewpoint, or perspectives sections. Not only are such sections frequently the most widely read portions of the journal (i.e. JAMA’s A Piece of My Mind ), but for some, including the New England Journal of Medicine , if you have the table of contents delivered to your inbox as I do, all you see are the essays; if you want the science, you need to scroll down. And that’s just the traditional medical press. Increasing numbers of health professionals write for and read blogs to learn about, reflect upon, and engage with others about issues in medicine from the results of a new study to coping with burnout and inspiring tales from the front lines of research and practice.

But the trend isn’t just among health professionals. The blogosphere is replete with sites focus on wellness, illness, aging, and the patient experience. Many of the writers for these sites are themselves patients or caregivers, but others write about these topics because they matter not just today with the ACA debates, but always, since birth, death, disease, and caring are the touchstones of most lives. This reality was recognized in the 2012 edition of Best American Essays in which eight, or fully one third, of the essays were about medicine. The topics ranged from menopause as a vehicle to the true self and how an aging doctor wants to die to a writing class for children at a cancer hospital and the benefits of gaining weight to treat depression. Only two were written by physicians. All combined great writing and storytelling with novel insights and important information or thoughts about life, illness, caregiving, and death. And, no, the editor of the 2012 edition was not a doctor.

So whether you’re a health profession who writes or wants to write or a writer working on a piece that deals in some way with medicine, health, or illness, there is clearly interest in this sort of work, and possibly even growing interest. Professional society annual meetings now feature workshops on narrative, advocacy writing, and social media, and many universities and medical schools now have courses in this sort of Public Medical Communication (PMC) writing, sponsor PMC-related annual conferences, and publish journals of essays, short stories, poetry, and art. Annual conferences around the nation invite anyone, professional or not, to come write about health and illness.

So what do all these essays and stories and blogs have in common? Each uses literary and journalistic techniques to explore topics related to health and health care in ways that are compelling, entertaining, and accessible to all. Mostly, it’s about communicating clearly, often using a story and characters to illustrate a point, and always about striving to understand and represent real lived experience.

Below is a partial list, in alphabetical order, of medical journals that publish this sort of work.

Academic Medicine

Medicine and the Arts (MATA): Two facing pages: left-hand page features an excerpt from literature, a poem, a photograph, etc. of no more than 700 words; right-hand page is a commentary of about 900 words that explores the relevance of the artwork to the teaching and/or practice of medicine.

Teaching and Learning Moments (TLM): Pieces vary in style and subject, but most are first-person, informal narratives from 250-600 words written from the perspective of instructor, student, or patient.

American Journal of Kidney Disease

In a Few Words: A nonfiction narrative essay up to 1,600 words which gives voice to the personal experiences and stories that define kidney disease. Submissions from physicians, allied health professionals, patients, or family members are welcome.

Annals of Internal Medicine

Perspective : Unstructured essays up to 1500 words representing opinions, presenting hypotheses, or considering controversial issues.

On Being a Doctor: Short essays or fiction up to 1500 words on illuminating experiences in practice.

On Being a Patient : Short essays up to 1500 words by physicians on their own experiences of illness and accounts written by patients or their families.

Personal Views: Highly readable, opinion based essays of about 850 words that make a single strong, novel, and well-argued point and are also often topical, significant, insightful, and attention grabbing.

Fillers : A articles of up to 600 words on topics such as: A patient who changed my practice; A memorable patient; A paper that changed my practice; The person who has most influenced me; My most informative mistake; Any other story conveying instruction, pathos, or humor.

Humanities: Unsolicited poetry, fiction and creative nonfiction limited to 1000 words or 75 lines (poems) that convey personal and professional experiences with a sense of immediacy and realism.

Salon: 700 word op-ed style articles of novel, lively, thoughtful and sometimes quirky ideas designed to ignite sparks of insight and stimulate thought and online discussion using our e-letters function.

Family Medicine

Narrative Essays : Stories from clinical practice or from the educational setting limited to 1000 words by teachers, learners, patients, or professionals practicing in the primary care disciplines that present a creative perspective both in their content and in their story-telling style. Narrative essays should illuminate the unique complexity and genuine personal dimensions of patient care and education in family medicine, primary care, or community medicine.

Health Affairs

Narrative Matters: Narrative essays of 2,500 words based on firsthand encounters with the health care system that explore the personal, ethical, and moral issues of delivering or receiving health care today.

A Piece of My Mind: Personal vignettes of up to 1800 words (eg, exploring the dynamics of the patient-physician relationship) taken from wide-ranging experiences in medicine; occasional views and opinions.

Poetry and Medicine: Poems no longer than 50 lines related to the medical experience, whether from the point of view of a health care worker or patient, or simply an observer.

Journal of the American Geriatrics Society

Old Lives Tales: Stories, experiences, or incidences of which have instructed, saddened or gladdened us and, above all, taught us something about the care of the older adult. 750 words.

Journal of General Internal Medicine

Materia Medica: Well-crafted, highly readable and engaging personal narratives, essays or short stories of up to 1500 words and poetry of up to 100 lines.

Text and Context: Excerpts from literature (novels, short stories, poetry, plays or creative non-fiction) of 200-800 words followed by an accompanying essay of up to 1000 words discussing the significance of the work for clinical practice or medical education.

Perspective: Articles limited to 1000 to 1200 words cover a wide variety of topics of current interest in health care, medicine, and the intersection between medicine and society.

Reflections: Poetry or prose, fiction or non-fiction, up to 2000 words that illustrate facets of the profession of neurology, particularly if written from a new perspective, are preferred. The quality of the writing style will be as important as the content.

Louise Aronson is a geriatrician and the author of A History of the Present Illness . She blogs at her self-titled site, Louse Aronson , and can be found on Twitter @LouiseAronson .

Image credit: Shutterstock.com

When doctors dissociate themselves from the stories of their patients

Medicare patients should care about the way we pay providers

More by Louise Aronson, MD

The problems with patient feedback forms and how to fix them

10 potential benefits of robot caregivers

Why physicians need to write

More in physician.

Burned out doctors, compromised care: a doctor’s story

Examining the coverage of DOs in the mainstream media

The unseen work of women surgeons.

Reviving humanity in medicine: Why doctors must embrace the human art of healing

Second opinions are no laughing matter.

Doctors or criminals? How misleading narratives hurt innocent lives

Most popular.

Why preventive care is the cure for our failing health care system

Pain management for Black patients and painful realities

Left in the dark: the censorship of health literature in prisons

The DEA’s latest targets: doctors treating addiction instead of pain

![Health care costs: Looking in the mirror for solutions [PODCAST] health narrative essay](https://www.kevinmd.com/wp-content/uploads/Health-care-costs-Looking-in-the-mirror-for-solutions-190x100.jpg)

Health care costs: Looking in the mirror for solutions [PODCAST]

Eye dryness, insomnia, and more: hidden signs you’re in perimenopause

Past 6 months.

We are all concierge doctors now

Health care in turmoil: costs, shortages, and pandemic strains

Gender bias is pervasive within state medical board official documents and websites

Supporting migrant adolescents

Once a pillar, now in ruins: the state of primary care

911 call turned deadly: It’s time we invest in our community

Recent posts.

Modernize medical education or face failure

Broken but beautiful: Healing ourselves and the world [PODCAST]

Subscribe to kevinmd and never miss a story.

Get free updates delivered free to your inbox.

Find jobs at Careers by KevinMD.com

Search thousands of physician, PA, NP, and CRNA jobs now.

CME Spotlights

Medical journals that accept stories and essays from physicians 6 comments

Comments are moderated before they are published. Please read the comment policy .

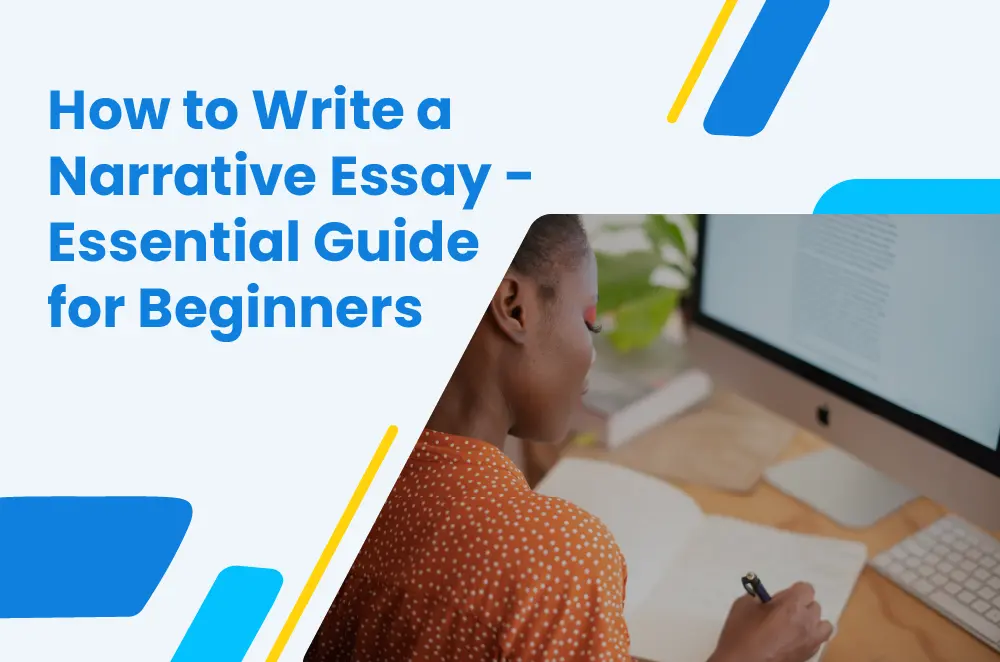

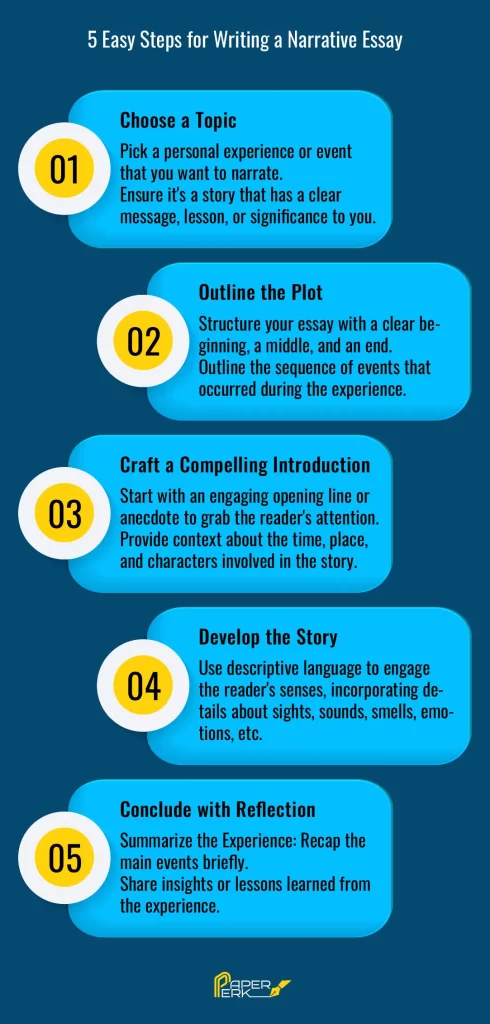

The Ultimate Narrative Essay Guide for Beginners

A narrative essay tells a story in chronological order, with an introduction that introduces the characters and sets the scene. Then a series of events leads to a climax or turning point, and finally a resolution or reflection on the experience.

Speaking of which, are you in sixes and sevens about narrative essays? Don’t worry this ultimate expert guide will wipe out all your doubts. So let’s get started.

Table of Contents

Everything You Need to Know About Narrative Essay

What is a narrative essay.

When you go through a narrative essay definition, you would know that a narrative essay purpose is to tell a story. It’s all about sharing an experience or event and is different from other types of essays because it’s more focused on how the event made you feel or what you learned from it, rather than just presenting facts or an argument. Let’s explore more details on this interesting write-up and get to know how to write a narrative essay.

Elements of a Narrative Essay

Here’s a breakdown of the key elements of a narrative essay:

A narrative essay has a beginning, middle, and end. It builds up tension and excitement and then wraps things up in a neat package.

Real people, including the writer, often feature in personal narratives. Details of the characters and their thoughts, feelings, and actions can help readers to relate to the tale.

It’s really important to know when and where something happened so we can get a good idea of the context. Going into detail about what it looks like helps the reader to really feel like they’re part of the story.

Conflict or Challenge

A story in a narrative essay usually involves some kind of conflict or challenge that moves the plot along. It could be something inside the character, like a personal battle, or something from outside, like an issue they have to face in the world.

Theme or Message

A narrative essay isn’t just about recounting an event – it’s about showing the impact it had on you and what you took away from it. It’s an opportunity to share your thoughts and feelings about the experience, and how it changed your outlook.

Emotional Impact

The author is trying to make the story they’re telling relatable, engaging, and memorable by using language and storytelling to evoke feelings in whoever’s reading it.

Narrative essays let writers have a blast telling stories about their own lives. It’s an opportunity to share insights and impart wisdom, or just have some fun with the reader. Descriptive language, sensory details, dialogue, and a great narrative voice are all essentials for making the story come alive.

The Purpose of a Narrative Essay

A narrative essay is more than just a story – it’s a way to share a meaningful, engaging, and relatable experience with the reader. Includes:

Sharing Personal Experience

Narrative essays are a great way for writers to share their personal experiences, feelings, thoughts, and reflections. It’s an opportunity to connect with readers and make them feel something.

Entertainment and Engagement

The essay attempts to keep the reader interested by using descriptive language, storytelling elements, and a powerful voice. It attempts to pull them in and make them feel involved by creating suspense, mystery, or an emotional connection.

Conveying a Message or Insight

Narrative essays are more than just a story – they aim to teach you something. They usually have a moral lesson, a new understanding, or a realization about life that the author gained from the experience.

Building Empathy and Understanding

By telling their stories, people can give others insight into different perspectives, feelings, and situations. Sharing these tales can create compassion in the reader and help broaden their knowledge of different life experiences.

Inspiration and Motivation

Stories about personal struggles, successes, and transformations can be really encouraging to people who are going through similar situations. It can provide them with hope and guidance, and let them know that they’re not alone.

Reflecting on Life’s Significance

These essays usually make you think about the importance of certain moments in life or the impact of certain experiences. They make you look deep within yourself and ponder on the things you learned or how you changed because of those events.

Demonstrating Writing Skills

Coming up with a gripping narrative essay takes serious writing chops, like vivid descriptions, powerful language, timing, and organization. It’s an opportunity for writers to show off their story-telling abilities.

Preserving Personal History

Sometimes narrative essays are used to record experiences and special moments that have an emotional resonance. They can be used to preserve individual memories or for future generations to look back on.

Cultural and Societal Exploration

Personal stories can look at cultural or social aspects, giving us an insight into customs, opinions, or social interactions seen through someone’s own experience.

Format of a Narrative Essay

Narrative essays are quite flexible in terms of format, which allows the writer to tell a story in a creative and compelling way. Here’s a quick breakdown of the narrative essay format, along with some examples:

Introduction

Set the scene and introduce the story.

Engage the reader and establish the tone of the narrative.

Hook: Start with a captivating opening line to grab the reader’s attention. For instance:

Example: “The scorching sun beat down on us as we trekked through the desert, our water supply dwindling.”

Background Information: Provide necessary context or background without giving away the entire story.

Example: “It was the summer of 2015 when I embarked on a life-changing journey to…”

Thesis Statement or Narrative Purpose

Present the main idea or the central message of the essay.

Offer a glimpse of what the reader can expect from the narrative.

Thesis Statement: This isn’t as rigid as in other essays but can be a sentence summarizing the essence of the story.

Example: “Little did I know, that seemingly ordinary hike would teach me invaluable lessons about resilience and friendship.”

Body Paragraphs

Present the sequence of events in chronological order.

Develop characters, setting, conflict, and resolution.

Story Progression : Describe events in the order they occurred, focusing on details that evoke emotions and create vivid imagery.

Example : Detail the trek through the desert, the challenges faced, interactions with fellow hikers, and the pivotal moments.

Character Development : Introduce characters and their roles in the story. Show their emotions, thoughts, and actions.

Example : Describe how each character reacted to the dwindling water supply and supported each other through adversity.

Dialogue and Interactions : Use dialogue to bring the story to life and reveal character personalities.

Example : “Sarah handed me her last bottle of water, saying, ‘We’re in this together.'”

Reach the peak of the story, the moment of highest tension or significance.

Turning Point: Highlight the most crucial moment or realization in the narrative.

Example: “As the sun dipped below the horizon and hope seemed lost, a distant sound caught our attention—the rescue team’s helicopters.”

Provide closure to the story.

Reflect on the significance of the experience and its impact.

Reflection : Summarize the key lessons learned or insights gained from the experience.

Example : “That hike taught me the true meaning of resilience and the invaluable support of friendship in challenging times.”

Closing Thought : End with a memorable line that reinforces the narrative’s message or leaves a lasting impression.

Example : “As we boarded the helicopters, I knew this adventure would forever be etched in my heart.”

Example Summary:

Imagine a narrative about surviving a challenging hike through the desert, emphasizing the bonds formed and lessons learned. The narrative essay structure might look like starting with an engaging scene, narrating the hardships faced, showcasing the characters’ resilience, and culminating in a powerful realization about friendship and endurance.

Different Types of Narrative Essays

There are a bunch of different types of narrative essays – each one focuses on different elements of storytelling and has its own purpose. Here’s a breakdown of the narrative essay types and what they mean.

Personal Narrative

Description : Tells a personal story or experience from the writer’s life.

Purpose: Reflects on personal growth, lessons learned, or significant moments.

Example of Narrative Essay Types:

Topic : “The Day I Conquered My Fear of Public Speaking”

Focus: Details the experience, emotions, and eventual triumph over a fear of public speaking during a pivotal event.

Descriptive Narrative

Description : Emphasizes vivid details and sensory imagery.

Purpose : Creates a sensory experience, painting a vivid picture for the reader.

Topic : “A Walk Through the Enchanted Forest”

Focus : Paints a detailed picture of the sights, sounds, smells, and feelings experienced during a walk through a mystical forest.

Autobiographical Narrative

Description: Chronicles significant events or moments from the writer’s life.

Purpose: Provides insights into the writer’s life, experiences, and growth.

Topic: “Lessons from My Childhood: How My Grandmother Shaped Who I Am”

Focus: Explores pivotal moments and lessons learned from interactions with a significant family member.

Experiential Narrative

Description: Relays experiences beyond the writer’s personal life.

Purpose: Shares experiences, travels, or events from a broader perspective.

Topic: “Volunteering in a Remote Village: A Journey of Empathy”

Focus: Chronicles the writer’s volunteering experience, highlighting interactions with a community and personal growth.

Literary Narrative

Description: Incorporates literary elements like symbolism, allegory, or thematic explorations.

Purpose: Uses storytelling for deeper explorations of themes or concepts.

Topic: “The Symbolism of the Red Door: A Journey Through Change”

Focus: Uses a red door as a symbol, exploring its significance in the narrator’s life and the theme of transition.

Historical Narrative

Description: Recounts historical events or periods through a personal lens.

Purpose: Presents history through personal experiences or perspectives.

Topic: “A Grandfather’s Tales: Living Through the Great Depression”

Focus: Shares personal stories from a family member who lived through a historical era, offering insights into that period.

Digital or Multimedia Narrative

Description: Incorporates multimedia elements like images, videos, or audio to tell a story.

Purpose: Explores storytelling through various digital platforms or formats.

Topic: “A Travel Diary: Exploring Europe Through Vlogs”

Focus: Combines video clips, photos, and personal narration to document a travel experience.

How to Choose a Topic for Your Narrative Essay?

Selecting a compelling topic for your narrative essay is crucial as it sets the stage for your storytelling. Choosing a boring topic is one of the narrative essay mistakes to avoid . Here’s a detailed guide on how to choose the right topic:

Reflect on Personal Experiences

- Significant Moments:

Moments that had a profound impact on your life or shaped your perspective.

Example: A moment of triumph, overcoming a fear, a life-changing decision, or an unforgettable experience.

- Emotional Resonance:

Events that evoke strong emotions or feelings.

Example: Joy, fear, sadness, excitement, or moments of realization.

- Lessons Learned:

Experiences that taught you valuable lessons or brought about personal growth.

Example: Challenges that led to personal development, shifts in mindset, or newfound insights.

Explore Unique Perspectives

- Uncommon Experiences:

Unique or unconventional experiences that might captivate the reader’s interest.

Example: Unusual travels, interactions with different cultures, or uncommon hobbies.

- Different Points of View:

Stories from others’ perspectives that impacted you deeply.

Example: A family member’s story, a friend’s experience, or a historical event from a personal lens.

Focus on Specific Themes or Concepts

- Themes or Concepts of Interest:

Themes or ideas you want to explore through storytelling.

Example: Friendship, resilience, identity, cultural diversity, or personal transformation.

- Symbolism or Metaphor:

Using symbols or metaphors as the core of your narrative.

Example: Exploring the symbolism of an object or a place in relation to a broader theme.

Consider Your Audience and Purpose

- Relevance to Your Audience:

Topics that resonate with your audience’s interests or experiences.

Example: Choose a relatable theme or experience that your readers might connect with emotionally.

- Impact or Message:

What message or insight do you want to convey through your story?

Example: Choose a topic that aligns with the message or lesson you aim to impart to your readers.

Brainstorm and Evaluate Ideas

- Free Writing or Mind Mapping:

Process: Write down all potential ideas without filtering. Mind maps or free-writing exercises can help generate diverse ideas.

- Evaluate Feasibility:

The depth of the story, the availability of vivid details, and your personal connection to the topic.

Imagine you’re considering topics for a narrative essay. You reflect on your experiences and decide to explore the topic of “Overcoming Stage Fright: How a School Play Changed My Perspective.” This topic resonates because it involves a significant challenge you faced and the personal growth it brought about.

Narrative Essay Topics

50 easy narrative essay topics.

- Learning to Ride a Bike

- My First Day of School

- A Surprise Birthday Party

- The Day I Got Lost

- Visiting a Haunted House

- An Encounter with a Wild Animal

- My Favorite Childhood Toy

- The Best Vacation I Ever Had

- An Unforgettable Family Gathering

- Conquering a Fear of Heights

- A Special Gift I Received

- Moving to a New City

- The Most Memorable Meal

- Getting Caught in a Rainstorm

- An Act of Kindness I Witnessed

- The First Time I Cooked a Meal

- My Experience with a New Hobby

- The Day I Met My Best Friend

- A Hike in the Mountains

- Learning a New Language

- An Embarrassing Moment

- Dealing with a Bully

- My First Job Interview

- A Sporting Event I Attended

- The Scariest Dream I Had

- Helping a Stranger

- The Joy of Achieving a Goal

- A Road Trip Adventure

- Overcoming a Personal Challenge

- The Significance of a Family Tradition

- An Unusual Pet I Owned

- A Misunderstanding with a Friend

- Exploring an Abandoned Building

- My Favorite Book and Why

- The Impact of a Role Model

- A Cultural Celebration I Participated In

- A Valuable Lesson from a Teacher

- A Trip to the Zoo

- An Unplanned Adventure

- Volunteering Experience

- A Moment of Forgiveness

- A Decision I Regretted

- A Special Talent I Have

- The Importance of Family Traditions

- The Thrill of Performing on Stage

- A Moment of Sudden Inspiration

- The Meaning of Home

- Learning to Play a Musical Instrument

- A Childhood Memory at the Park

- Witnessing a Beautiful Sunset

Narrative Essay Topics for College Students

- Discovering a New Passion

- Overcoming Academic Challenges

- Navigating Cultural Differences

- Embracing Independence: Moving Away from Home

- Exploring Career Aspirations

- Coping with Stress in College

- The Impact of a Mentor in My Life

- Balancing Work and Studies

- Facing a Fear of Public Speaking

- Exploring a Semester Abroad

- The Evolution of My Study Habits

- Volunteering Experience That Changed My Perspective

- The Role of Technology in Education

- Finding Balance: Social Life vs. Academics

- Learning a New Skill Outside the Classroom

- Reflecting on Freshman Year Challenges

- The Joys and Struggles of Group Projects

- My Experience with Internship or Work Placement

- Challenges of Time Management in College

- Redefining Success Beyond Grades

- The Influence of Literature on My Thinking

- The Impact of Social Media on College Life

- Overcoming Procrastination

- Lessons from a Leadership Role

- Exploring Diversity on Campus

- Exploring Passion for Environmental Conservation

- An Eye-Opening Course That Changed My Perspective

- Living with Roommates: Challenges and Lessons

- The Significance of Extracurricular Activities

- The Influence of a Professor on My Academic Journey

- Discussing Mental Health in College

- The Evolution of My Career Goals

- Confronting Personal Biases Through Education

- The Experience of Attending a Conference or Symposium

- Challenges Faced by Non-Native English Speakers in College

- The Impact of Traveling During Breaks

- Exploring Identity: Cultural or Personal

- The Impact of Music or Art on My Life

- Addressing Diversity in the Classroom

- Exploring Entrepreneurial Ambitions

- My Experience with Research Projects

- Overcoming Impostor Syndrome in College

- The Importance of Networking in College

- Finding Resilience During Tough Times

- The Impact of Global Issues on Local Perspectives

- The Influence of Family Expectations on Education

- Lessons from a Part-Time Job

- Exploring the College Sports Culture

- The Role of Technology in Modern Education

- The Journey of Self-Discovery Through Education

Narrative Essay Comparison

Narrative essay vs. descriptive essay.

Here’s our first narrative essay comparison! While both narrative and descriptive essays focus on vividly portraying a subject or an event, they differ in their primary objectives and approaches. Now, let’s delve into the nuances of comparison on narrative essays.

Narrative Essay:

Storytelling: Focuses on narrating a personal experience or event.

Chronological Order: Follows a structured timeline of events to tell a story.

Message or Lesson: Often includes a central message, moral, or lesson learned from the experience.

Engagement: Aims to captivate the reader through a compelling storyline and character development.

First-Person Perspective: Typically narrated from the writer’s point of view, using “I” and expressing personal emotions and thoughts.

Plot Development: Emphasizes a plot with a beginning, middle, climax, and resolution.

Character Development: Focuses on describing characters, their interactions, emotions, and growth.

Conflict or Challenge: Usually involves a central conflict or challenge that drives the narrative forward.

Dialogue: Incorporates conversations to bring characters and their interactions to life.

Reflection: Concludes with reflection or insight gained from the experience.

Descriptive Essay:

Vivid Description: Aims to vividly depict a person, place, object, or event.

Imagery and Details: Focuses on sensory details to create a vivid image in the reader’s mind.

Emotion through Description: Uses descriptive language to evoke emotions and engage the reader’s senses.

Painting a Picture: Creates a sensory-rich description allowing the reader to visualize the subject.

Imagery and Sensory Details: Focuses on providing rich sensory descriptions, using vivid language and adjectives.

Point of Focus: Concentrates on describing a specific subject or scene in detail.

Spatial Organization: Often employs spatial organization to describe from one area or aspect to another.

Objective Observations: Typically avoids the use of personal opinions or emotions; instead, the focus remains on providing a detailed and objective description.

Comparison:

Focus: Narrative essays emphasize storytelling, while descriptive essays focus on vividly describing a subject or scene.

Perspective: Narrative essays are often written from a first-person perspective, while descriptive essays may use a more objective viewpoint.

Purpose: Narrative essays aim to convey a message or lesson through a story, while descriptive essays aim to paint a detailed picture for the reader without necessarily conveying a specific message.

Narrative Essay vs. Argumentative Essay

The narrative essay and the argumentative essay serve distinct purposes and employ different approaches:

Engagement and Emotion: Aims to captivate the reader through a compelling story.

Reflective: Often includes reflection on the significance of the experience or lessons learned.

First-Person Perspective: Typically narrated from the writer’s point of view, sharing personal emotions and thoughts.

Plot Development: Emphasizes a storyline with a beginning, middle, climax, and resolution.

Message or Lesson: Conveys a central message, moral, or insight derived from the experience.

Argumentative Essay:

Persuasion and Argumentation: Aims to persuade the reader to adopt the writer’s viewpoint on a specific topic.

Logical Reasoning: Presents evidence, facts, and reasoning to support a particular argument or stance.

Debate and Counterarguments: Acknowledge opposing views and counter them with evidence and reasoning.

Thesis Statement: Includes a clear thesis statement that outlines the writer’s position on the topic.

Thesis and Evidence: Starts with a strong thesis statement and supports it with factual evidence, statistics, expert opinions, or logical reasoning.

Counterarguments: Addresses opposing viewpoints and provides rebuttals with evidence.

Logical Structure: Follows a logical structure with an introduction, body paragraphs presenting arguments and evidence, and a conclusion reaffirming the thesis.

Formal Language: Uses formal language and avoids personal anecdotes or emotional appeals.

Objective: Argumentative essays focus on presenting a logical argument supported by evidence, while narrative essays prioritize storytelling and personal reflection.

Purpose: Argumentative essays aim to persuade and convince the reader of a particular viewpoint, while narrative essays aim to engage, entertain, and share personal experiences.

Structure: Narrative essays follow a storytelling structure with character development and plot, while argumentative essays follow a more formal, structured approach with logical arguments and evidence.

In essence, while both essays involve writing and presenting information, the narrative essay focuses on sharing a personal experience, whereas the argumentative essay aims to persuade the audience by presenting a well-supported argument.

Narrative Essay vs. Personal Essay

While there can be an overlap between narrative and personal essays, they have distinctive characteristics:

Storytelling: Emphasizes recounting a specific experience or event in a structured narrative form.

Engagement through Story: Aims to engage the reader through a compelling story with characters, plot, and a central theme or message.

Reflective: Often includes reflection on the significance of the experience and the lessons learned.

First-Person Perspective: Typically narrated from the writer’s viewpoint, expressing personal emotions and thoughts.

Plot Development: Focuses on developing a storyline with a clear beginning, middle, climax, and resolution.

Character Development: Includes descriptions of characters, their interactions, emotions, and growth.

Central Message: Conveys a central message, moral, or insight derived from the experience.

Personal Essay:

Exploration of Ideas or Themes: Explores personal ideas, opinions, or reflections on a particular topic or subject.

Expression of Thoughts and Opinions: Expresses the writer’s thoughts, feelings, and perspectives on a specific subject matter.

Reflection and Introspection: Often involves self-reflection and introspection on personal experiences, beliefs, or values.

Varied Structure and Content: Can encompass various forms, including memoirs, personal anecdotes, or reflections on life experiences.

Flexibility in Structure: Allows for diverse structures and forms based on the writer’s intent, which could be narrative-like or more reflective.

Theme-Centric Writing: Focuses on exploring a central theme or idea, with personal anecdotes or experiences supporting and illustrating the theme.

Expressive Language: Utilizes descriptive and expressive language to convey personal perspectives, emotions, and opinions.

Focus: Narrative essays primarily focus on storytelling through a structured narrative, while personal essays encompass a broader range of personal expression, which can include storytelling but isn’t limited to it.

Structure: Narrative essays have a more structured plot development with characters and a clear sequence of events, while personal essays might adopt various structures, focusing more on personal reflection, ideas, or themes.

Intent: While both involve personal experiences, narrative essays emphasize telling a story with a message or lesson learned, while personal essays aim to explore personal thoughts, feelings, or opinions on a broader range of topics or themes.

A narrative essay is more than just telling a story. It’s also meant to engage the reader, get them thinking, and leave a lasting impact. Whether it’s to amuse, motivate, teach, or reflect, these essays are a great way to communicate with your audience. This interesting narrative essay guide was all about letting you understand the narrative essay, its importance, and how can you write one.

Order Original Papers & Essays

Your First Custom Paper Sample is on Us!

Timely Deliveries

No Plagiarism & AI

100% Refund

Try Our Free Paper Writing Service

Related blogs.

Connections with Writers and support

Privacy and Confidentiality Guarantee

Average Quality Score

Narrative Essay Overview

Narration is a rhetorical style that basically just tells a story. Being able to convey events in a clear, descriptive, chronological order is important in many fields. Many times, in college, your professors will ask you to write paragraphs or entire essays using a narrative style.

A narration (or narrative) essay is structured around the goal of recounting a story. Most of the time, in introductory writing classes, students write narration essays that discuss personal stories; however, in different disciplines, you may be asked to tell a story about another person’s experience or an event.

NOTE: Remember, if you’re writing a narrative essay, even though you’re telling a story, you’ll often be required to include a strong introduction, thesis statement, and conclusion.

LICENSES AND ATTRIBUTIONS

Excelsior Online Writing Lab (OWL). Located at: https://owl.excelsior.edu/ . This site is licensed under a https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

ENG102 Contextualized for Health Sciences - OpenSkill Fellowship Copyright © 2022 by Compiled by Lori Walk. All Rights Reserved.

Share This Book

16 Personal Essays About Mental Health Worth Reading

Here are some of the most moving and illuminating essays published on BuzzFeed about mental illness, wellness, and the way our minds work.

BuzzFeed Staff

1. My Best Friend Saved Me When I Attempted Suicide, But I Didn’t Save Her — Drusilla Moorhouse

"I was serious about killing myself. My best friend wasn’t — but she’s the one who’s dead."

2. Life Is What Happens While You’re Googling Symptoms Of Cancer — Ramona Emerson

"After a lifetime of hypochondria, I was finally diagnosed with my very own medical condition. And maybe, in a weird way, it’s made me less afraid to die."

3. How I Learned To Be OK With Feeling Sad — Mac McClelland

"It wasn’t easy, or cheap."

4. Who Gets To Be The “Good Schizophrenic”? — Esmé Weijun Wang

"When you’re labeled as crazy, the “right” kind of diagnosis could mean the difference between a productive life and a life sentence."

5. Why Do I Miss Being Bipolar? — Sasha Chapin

"The medication I take to treat my bipolar disorder works perfectly. Sometimes I wish it didn’t."

6. What My Best Friend And I Didn’t Learn About Loss — Zan Romanoff

"When my closest friend’s first baby was stillborn, we navigated through depression and grief together."

7. I Can’t Live Without Fear, But I Can Learn To Be OK With It — Arianna Rebolini

"I’ve become obsessively afraid that the people I love will die. Now I have to teach myself how to be OK with that."

8. What It’s Like Having PPD As A Black Woman — Tyrese Coleman

"It took me two years to even acknowledge I’d been depressed after the birth of my twin sons. I wonder how much it had to do with the way I had been taught to be strong."

9. Notes On An Eating Disorder — Larissa Pham

"I still tell my friends I am in recovery so they will hold me accountable."

10. What Comedy Taught Me About My Mental Illness — Kate Lindstedt

"I didn’t expect it, but stand-up comedy has given me the freedom to talk about depression and anxiety on my own terms."

11. The Night I Spoke Up About My #BlackSuicide — Terrell J. Starr

"My entire life was shaped by violence, so I wanted to end it violently. But I didn’t — thanks to overcoming the stigma surrounding African-Americans and depression, and to building a community on Twitter."

12. Knitting Myself Back Together — Alanna Okun

"The best way I’ve found to fight my anxiety is with a pair of knitting needles."

13. I Started Therapy So I Could Take Better Care Of Myself — Matt Ortile

"I’d known for a while that I needed to see a therapist. It wasn’t until I felt like I could do without help that I finally sought it."

14. I’m Mending My Broken Relationship With Food — Anita Badejo

"After a lifetime struggling with disordered eating, I’m still figuring out how to have a healthy relationship with my body and what I feed it."

15. I Found Love In A Hopeless Mess — Kate Conger

"Dehoarding my partner’s childhood home gave me a way to understand his mother, but I’m still not sure how to live with the habit he’s inherited."

16. When Taking Anxiety Medication Is A Revolutionary Act — Tracy Clayton

"I had to learn how to love myself enough to take care of myself. It wasn’t easy."

Topics in this article

- Mental Health

- TEFL Internship

- TEFL Masters

- Find a TEFL Course

- Special Offers

- Course Providers

- Teach English Abroad

- Find a TEFL Job

- About DoTEFL

- Our Mission

- How DoTEFL Works

Forgotten Password

- How To Write a Narrative Essay: Guide With Examples

- Learn English

- James Prior

- No Comments

- Updated December 12, 2023

Welcome to the creative world of narrative essays where you get to become the storyteller and craft your own narrative. In this article, we’ll break down how to write a narrative essay, covering the essential elements and techniques that you need to know.

Table of Contents

What is a Narrative Essay?

A narrative essay is a form of writing where the author recounts a personal experience or story. Unlike other types of essays, a narrative essay allows you to share a real-life event or sequence of events, often drawing from personal insights and emotions.

In a narrative essay, you take on the role of a storyteller, employing vivid details and descriptive language to transport the reader into the world of your story. The narrative often unfolds in chronological order, guiding the audience through a journey of experiences, reflections, and sometimes, a lesson learned.

The success of a narrative essay lies in your ability to create a compelling narrative arc. This means establishing a clear beginning, middle, and end. This structure helps build suspense, maintain the reader’s interest, and deliver a cohesive and impactful story. Ultimately, a well-crafted narrative essay not only narrates an event but also communicates the deeper meaning or significance behind the experience, making it a powerful and memorable piece of writing and leaving a lasting impression on the reader.

Types of Narrative Essays

Narrative essays come in various forms, each with unique characteristics. The most common type of narrative essay are personal narrative essays where you write about a personal experience. This can cover a whole range of topics as these examples of personal narrative essays illustrate. As a student in school or college, you’ll often be asked to write these types of essays. You may also need to write them later in life when applying for jobs and describing your past experiences.

However, this isn’t the only type of narrative essay. There are also fictional narrative essays that you can write using your imagination, and various subject specific narrative essays that you might have come across without even realizing it.

So, it’s worth knowing about the different types of narrative essays and what they each focus on before we move on to how to write them.

Here are some common types of narrative essays:

- Focus on a personal experience or event from the author’s life.

- Use the first-person perspective to convey the writer’s emotions and reflections.

- Can take many forms, from science fiction and fantasy to adventure and romance.

- Spark the imagination to create captivating stories.

- Provide a detailed account of the author’s life, often covering a significant timespan.

- Explore key life events, achievements, challenges, and personal growth.

- Reflect on the writer’s experiences with language, reading, or writing.

- Explore how these experiences have shaped the writer’s identity and skills

- Document the author’s experiences and insights gained from a journey or travel.

- Describe places visited, people encountered, and the lessons learned during the trip.

- Explore historical events or periods through a personal lens.

- Combine factual information with the writer’s perspective and experiences.

The narrative essay type you’ll work with often depends on the purpose, audience, and nature of the story being told. So, how should you write narrative essays?

How To Write Narrative Essays

From selecting the right topic to building a captivating storyline, we explore the basics to guide you in creating engaging narratives. So, grab your pen, and let’s delve into the fundamentals of writing a standout narrative essay.

Before we start, it’s worth pointing out that most narrative essays are written in the first-person. Through the use of first-person perspective, you get to connect with the reader, offering a glimpse into your thoughts, reactions, and the significance of the story being shared.

Let’s get into how to create these stories:

Write your plot

If you want to tell a compelling story you need a good plot. Your plot will give your story a structure. Every good story includes some kind of conflict. You should start with setting the scene for readers. After this, you introduce a challenge or obstacle. Readers will keep reading until the end to find out how you managed to overcome it.

Your story should reach a climax where tension is highest. This will be the turning point that leads to a resolution. For example, moving outside of your comfort zone was difficult and scary. It wasn’t easy at first but eventually, you grew braver and more confident. Readers should discover more about who you are as a person through what they read.

A seasoned writer knows how to craft a story that connects with an audience and creates an impact.

Hook readers with your introduction

In your introduction, you will introduce the main idea of your essay and set the context. Ways to make it more engaging are to:

- Use sensory images to describe the setting in which your story takes place.

- Use a quote that illustrates your main idea.

- Pose an intriguing question.

- Introduce an unexpected fact or a statement that grabs attention.

Develop your characters

You need to make readers feel they know any characters you introduce in your narrative essay. You can do this by revealing their personalities and quirks through the actions they take. It is always better to show the actions of characters rather than giving facts about them. Describing a character’s body language and features can also reveal a great deal about the person. You can check out these adjectives to describe a person to get some inspiration.

Use dialogue

Dialogue can bring your narrative essay to life. Most fiction books use dialogue extensively . It helps to move the story along in a subtle way. When you allow characters to talk, what they have to say seems more realistic. You can use similes , metaphors, and other parts of speech to make your story more compelling. Just make sure the dialogue is written clearly with the right punctuation so readers understand exactly who is talking.

Work on the pace of the story

Your story must flow along at a steady pace. If there’s too much action, readers may get confused. If you use descriptive writing, try not to overdo it. The clear, concise language throughout will appeal to readers more than lengthy descriptions.

Build up towards a climax

This is the point at which the tension in your story is the highest. A compelling climax takes readers by surprise. They may not have seen it coming. This doesn’t mean your climax should come out of left field. You need to carefully lead up to it step by step and guide readers along. When you reveal it they should be able to look back and realize it’s logical.

Cut out what you don’t need

Your story will suffer if you include too much detail that doesn’t move your story along. It may flow better once you cut out some unnecessary details. Most narrative essays are about five paragraphs but this will depend on the topic and requirements.

In a narrative essay, you share your experiences and insights. The journey you take your readers on should leave them feeling moved or inspired. It takes practice to learn how to write in a way that causes this reaction. With a good plot as your guide, it’s easier to write a compelling story that flows toward a satisfying resolution.

- Recent Posts

- 113+ American Slang Words & Phrases With Examples - May 29, 2024

- 11 Best Business English Courses Online - May 29, 2024

- How to Teach Business English - May 27, 2024

More from DoTEFL

11 Best Language Exchange Apps & Websites (2024)

- Updated January 18, 2024

7 Reasons Why You Should Study for Your TEFL Certificate Online

- Updated November 8, 2023

11 Effective Ways to Learn Vocabulary Fast

- Updated January 28, 2024

How to Write a Conclusion That Leaves a Lasting Impression

- Updated July 24, 2023

How to Teach Business English

- Updated May 29, 2024

Is Teaching English Abroad Worth It? A Teacher’s Perspective

- Updated May 1, 2024

- The global TEFL course directory.

The Benefits and Challenges of Socialized Medicine

This essay about socialized medicine examines its role in providing universal healthcare access, transcending wealth and privilege to ensure equitable health services for all. It highlights the benefits of health equity and cost control while addressing challenges such as funding, political opposition, and bureaucratic inefficiencies. The narrative explores both the promise and obstacles of socialized medicine, emphasizing its potential to transform the healthcare landscape despite the hurdles it faces.

How it works

In the complex framework of healthcare systems, socialized medicine stands out as a bold initiative, infusing the narrative of access with vibrant inclusivity while navigating the stormy seas of controversy. This intricate narrative intertwines numerous benefits and challenges, crafting a story of healthcare evolution marked by both admiration and apprehension.

At its essence, socialized medicine epitomizes the noble aspiration of universal healthcare, transcending the confines of wealth and privilege. By eliminating financial barriers, it heralds an era where medical facilities open their doors to all, embracing every individual with healthcare services.

In this egalitarian vision, the threat of financial catastrophe fades, replaced by the comforting assurance that one’s socioeconomic status will not determine the quality of care they receive.

In the grand orchestration of health equity, socialized medicine serves as a steadfast conductor, harmonizing a melody of accessibility for all. Marginalized communities are no longer relegated to the fringes of healthcare access, as the beacon of universal coverage shines brightly, guiding the way toward a more just and equitable healthcare landscape. In this radiant vision, the vast gap between privilege and poverty narrows, fostering a society where the right to health is upheld as an unalienable birthright.

Yet, amidst the chorus of praise, discordant notes of dissent resonate through the discourse. The call for fiscal responsibility echoes, its tone tinged with concern over the immense challenge of funding such a monumental endeavor. The shadow of taxation looms large, casting doubt on the feasibility of sustaining this lofty vision without straining the state’s finances.

Furthermore, the political arena becomes a battleground, where entrenched interests vie for dominance. Private insurers, pharmaceutical giants, and vested stakeholders act as defenders of the status quo, wary of the transformative potential that socialized medicine represents. Armed with the tools of lobbying and misinformation, they wage an unrelenting campaign to erode public support and maintain the existing order.

Yet, perhaps the most formidable challenge lies within the labyrinthine corridors of bureaucracy. Here, the machinery of governance grinds slowly, entangled in a web of red tape and administrative obstacles. Long wait times and bureaucratic inefficiencies threaten to undermine the very foundation of socialized medicine, casting doubt on its capacity to provide timely and effective care.

In the arena of innovation, socialized medicine faces another test. The swift advance of technological progress heralds a new era of healthcare delivery, where precision medicine and digital therapeutics promise to revolutionize patient care. Yet, amidst the excitement of progress, the risk of stagnation looms, threatening to stifle innovation and consign patients to outdated treatments and practices.

In conclusion, the narrative of socialized medicine is one of victory and challenge, a story of hope and difficulty woven into the fabric of healthcare discourse. Its benefits are numerous, offering the promise of universal access, health equity, and cost control. Yet, its journey is fraught with obstacles, from the bureaucratic maze to political opposition and the imperative of fiscal responsibility. Ultimately, the future of socialized medicine hangs in the balance, uncertain yet filled with the potential to transform the healthcare landscape for generations to come.

Cite this page

The Benefits and Challenges of Socialized Medicine. (2024, May 28). Retrieved from https://papersowl.com/examples/the-benefits-and-challenges-of-socialized-medicine/

"The Benefits and Challenges of Socialized Medicine." PapersOwl.com , 28 May 2024, https://papersowl.com/examples/the-benefits-and-challenges-of-socialized-medicine/

PapersOwl.com. (2024). The Benefits and Challenges of Socialized Medicine . [Online]. Available at: https://papersowl.com/examples/the-benefits-and-challenges-of-socialized-medicine/ [Accessed: 30 May. 2024]

"The Benefits and Challenges of Socialized Medicine." PapersOwl.com, May 28, 2024. Accessed May 30, 2024. https://papersowl.com/examples/the-benefits-and-challenges-of-socialized-medicine/

"The Benefits and Challenges of Socialized Medicine," PapersOwl.com , 28-May-2024. [Online]. Available: https://papersowl.com/examples/the-benefits-and-challenges-of-socialized-medicine/. [Accessed: 30-May-2024]

PapersOwl.com. (2024). The Benefits and Challenges of Socialized Medicine . [Online]. Available at: https://papersowl.com/examples/the-benefits-and-challenges-of-socialized-medicine/ [Accessed: 30-May-2024]

Don't let plagiarism ruin your grade

Hire a writer to get a unique paper crafted to your needs.

Our writers will help you fix any mistakes and get an A+!

Please check your inbox.

You can order an original essay written according to your instructions.

Trusted by over 1 million students worldwide

1. Tell Us Your Requirements

2. Pick your perfect writer

3. Get Your Paper and Pay

Hi! I'm Amy, your personal assistant!

Don't know where to start? Give me your paper requirements and I connect you to an academic expert.

short deadlines

100% Plagiarism-Free

Certified writers

- Download PDF

- Share X Facebook Email LinkedIn

- Permissions

Narrative Matters: The Power of the Personal Essay in Health Policy

Book and Media Reviews Section Editor: John L. Zeller, MD, PhD, Fishbein Fellow.

Narrative Matters is a compilation of accounts depicting health and disease and their context in the 21st century. It includes tales written by clinicians, policy makers, parents, children, and patients. Although stories about the human struggle with illness have been written since the dawn of humanity, this compilation is unique not only because of its strong relevance to today's health policy but also because it was first published in Health Affairs , a formal health policy journal. Thus, the reader is surrounded by a comfortable realization that these narratives indeed matter.

Sacajiu GM. Narrative Matters: The Power of the Personal Essay in Health Policy. JAMA. 2007;297(22):2529–2533. doi:10.1001/jama.297.22.2531

Manage citations:

© 2024

Artificial Intelligence Resource Center

Cardiology in JAMA : Read the Latest

Browse and subscribe to JAMA Network podcasts!

Others Also Liked

Select your interests.

Customize your JAMA Network experience by selecting one or more topics from the list below.

- Academic Medicine

- Acid Base, Electrolytes, Fluids

- Allergy and Clinical Immunology

- American Indian or Alaska Natives

- Anesthesiology

- Anticoagulation

- Art and Images in Psychiatry

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assisted Reproduction

- Bleeding and Transfusion

- Caring for the Critically Ill Patient

- Challenges in Clinical Electrocardiography

- Climate and Health

- Climate Change

- Clinical Challenge

- Clinical Decision Support

- Clinical Implications of Basic Neuroscience

- Clinical Pharmacy and Pharmacology

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Consensus Statements

- Coronavirus (COVID-19)

- Critical Care Medicine

- Cultural Competency

- Dental Medicine

- Dermatology

- Diabetes and Endocrinology

- Diagnostic Test Interpretation

- Drug Development

- Electronic Health Records

- Emergency Medicine

- End of Life, Hospice, Palliative Care

- Environmental Health

- Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion

- Facial Plastic Surgery

- Gastroenterology and Hepatology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Genomics and Precision Health

- Global Health

- Guide to Statistics and Methods

- Hair Disorders

- Health Care Delivery Models

- Health Care Economics, Insurance, Payment

- Health Care Quality

- Health Care Reform

- Health Care Safety

- Health Care Workforce

- Health Disparities

- Health Inequities

- Health Policy

- Health Systems Science

- History of Medicine

- Hypertension

- Images in Neurology

- Implementation Science

- Infectious Diseases

- Innovations in Health Care Delivery

- JAMA Infographic

- Law and Medicine

- Leading Change

- Less is More

- LGBTQIA Medicine

- Lifestyle Behaviors

- Medical Coding

- Medical Devices and Equipment

- Medical Education

- Medical Education and Training

- Medical Journals and Publishing

- Mobile Health and Telemedicine

- Narrative Medicine

- Neuroscience and Psychiatry

- Notable Notes

- Nutrition, Obesity, Exercise

- Obstetrics and Gynecology

- Occupational Health

- Ophthalmology

- Orthopedics

- Otolaryngology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Care

- Pathology and Laboratory Medicine

- Patient Care

- Patient Information

- Performance Improvement

- Performance Measures

- Perioperative Care and Consultation

- Pharmacoeconomics

- Pharmacoepidemiology

- Pharmacogenetics

- Pharmacy and Clinical Pharmacology

- Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation

- Physical Therapy

- Physician Leadership

- Population Health

- Primary Care

- Professional Well-being

- Professionalism

- Psychiatry and Behavioral Health

- Public Health

- Pulmonary Medicine

- Regulatory Agencies

- Reproductive Health

- Research, Methods, Statistics

- Resuscitation

- Rheumatology

- Risk Management

- Scientific Discovery and the Future of Medicine

- Shared Decision Making and Communication

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports Medicine

- Stem Cell Transplantation

- Substance Use and Addiction Medicine

- Surgical Innovation

- Surgical Pearls

- Teachable Moment

- Technology and Finance

- The Art of JAMA

- The Arts and Medicine

- The Rational Clinical Examination

- Tobacco and e-Cigarettes

- Translational Medicine

- Trauma and Injury

- Treatment Adherence

- Ultrasonography

- Users' Guide to the Medical Literature

- Vaccination

- Venous Thromboembolism

- Veterans Health

- Women's Health

- Workflow and Process

- Wound Care, Infection, Healing

- Register for email alerts with links to free full-text articles

- Access PDFs of free articles

- Manage your interests

- Save searches and receive search alerts

Writing Can Change Health Care

For more than 20 years, the “ Narrative Matters ” section of the health policy journal Health Affairs has showcased some of the most compelling personal stories in health care. I have edited the section since the fall of 2012, following in the footsteps of Ellen Ficklen, Kyna Rubin, and the section’s founding editor, the late Fitzhugh Mullan. When Mullan launched the section in 1999 with the encouragement of John Iglehart, the founding editor of Health Affairs , he and the rest of the Health Affairs team envisioned it as an opportunity to leverage the power of storytelling – with all its depth, drama, and emotion – to bring a human, and humane, perspective to research data and to policy debates. As a happy by-product, we’ve also nurtured this form of writing (what we call the “policy narrative,” but also the genre of medical and health narratives more broadly) by creating a regular space for it, and providing peer review and editorial guidance to authors. In 2006, Mullan, Ficklen, and Rubin gathered some of the most popular Narrative Matters essays in a collection called Narrative Matters: The Power of the Personal Essay in Health Policy (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2006). In the time since that edition was published, the genre of medical and health narratives, often called “narrative medicine” a la Rita Charon’s groundbreaking program at Columbia University, has exploded. To date, Health Affairs has published more than 250 essays in the Narrative Matters section – along with some poetry. Time flies, and it has now been nearly a decade-and-a-half since that first edition came out. We felt it was time for an updated collection featuring some of our favorite recent essays.

The subtitle of the new edition of Narrative Matters might sound ambitious – “writing to change the health care system” – but we do believe writing is that powerful. These essays will stay with you, long after you’ve put the book down and gone about your day. We know anecdotally that they’ve been used in health advocacy and decision-making. And we know that they enrich, rather than replace, important health care research findings, while also giving voice to subtle issues within health care that research can’t tackle. Sharing intimate details of sometimes-painful health care experiences takes extreme courage, and we’re grateful to our authors for going on this journey with us. Mullan himself chronicled his deeply personal experiences as a physician and cancer survivor in his writing, including in his books Vital Signs: A Young Doctor’s Struggle With Cancer (Dell Publishing Company, 1984) and White Coat, Clenched Fist: The Political Education of an American Physician (Macmillan, 1976). Mullan, who was very supportive of and excited about this new edition, died from complications of cancer on November 29, 2019. This book is dedicated to him.

The topics covered in this new volume touch on familiar health care challenges such as appropriate end-of-life care, as well as new issues of the day, including opioid use disorders, transgender health care, and the impact of national immigration policies on the practice of medicine. Contributors include Pulitzer Prize–winner Siddhartha Mukherjee, MacArthur fellow Diane Meier, former Planned Parenthood president Leana S. Wen, former secretary of health and human services Louis W. Sullivan, and National Humanities Medal recipient Abraham Verghese, who also authored a new foreword for this edition.

Importantly, the growing field of medical and health narratives is not just about documenting complaints with the health care system and highlighting its failures. To be sure, that’s an important function of the genre, and many of the essays in this volume do shed light on systemic problems in health care, and offer potential solutions. For instance, in “‘Go Back To California: When Providers Fail Transgender Patients,” transgender doctor Laura Arrowsmith writes that doctors in training learn about obscure medical diseases that they may never encounter in medical practice, yet are not taught how to care for transgender patients – a population they will almost certainly encounter in practice. Still, health care offers lessons beyond the “horror stories,” and there’s a place in the genre to document where health care gets it right, too. I’m glad we were able to highlight that in several essays in the volume, such as in Maureen Mavrinac’s “Rethinking the Traditional Doctor’s Visit,” which shows how shared medical appointments can create new paths to healing in health care, and in “‘I Don’t Want Jenny to Think I’m Abandoning Her’: Views on Overtreatment” by Diane Meier, in which the author, a palliative care physician, teaches an oncologist that sometimes the most compassionate way to care for a patient is to know when to give up treatment.

This new edition of Narrative Matters would make an excellent teaching tool in a variety of courses. Beyond that, it’s just good reading, for anyone who has or will encounter the US health system as a patient (and, of course, that’s everyone). Chances are you’ll shed a few tears as you make your way through the powerful pieces in this book, and you’ll learn something along the way.

Order Narrative Matters: Writing to Change the Health Care System – published on March 3, 2020 – at the following link: https://jhupbooks.press.jhu.edu/title/narrative-matters

Jessica Bylander is a senior editor at Health Affairs and the editor of Narrative Matters: Writing to Change the Health Care System .

Witches, devils, ghouls...and books! This Halloween, explore hauntingly good books from Hopkins Press, including The Secret History of the Jersey Devil and Dead Women Talking and uncover the mysteries and legends of the spookiest time of the year.

- Table of Contents

Volume 11 — June 05, 2014

Article Tools

- PDF - 381 KB

- Download citation

- Send feedback to PCD

- Display this article on your Web site

TOOLS AND TECHNIQUES

Using written narratives in public health practice: a creative writing perspective, navigate this article, using stories, acknowledgments, author information, tess thompson, mph, mphil; matthew w. kreuter, phd.

Suggested citation for this article: Thompson T, Kreuter MW. Using Written Narratives in Public Health Practice: A Creative Writing Perspective. Prev Chronic Dis 2014;11:130402. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5888/pcd11.130402 .

PEER REVIEWED