Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

8.3 Intercultural Communication

Learning objectives.

- Define intercultural communication.

- List and summarize the six dialectics of intercultural communication.

- Discuss how intercultural communication affects interpersonal relationships.

It is through intercultural communication that we come to create, understand, and transform culture and identity. Intercultural communication is communication between people with differing cultural identities. One reason we should study intercultural communication is to foster greater self-awareness (Martin & Nakayama, 2010). Our thought process regarding culture is often “other focused,” meaning that the culture of the other person or group is what stands out in our perception. However, the old adage “know thyself” is appropriate, as we become more aware of our own culture by better understanding other cultures and perspectives. Intercultural communication can allow us to step outside of our comfortable, usual frame of reference and see our culture through a different lens. Additionally, as we become more self-aware, we may also become more ethical communicators as we challenge our ethnocentrism , or our tendency to view our own culture as superior to other cultures.

As was noted earlier, difference matters, and studying intercultural communication can help us better negotiate our changing world. Changing economies and technologies intersect with culture in meaningful ways (Martin & Nakayama). As was noted earlier, technology has created for some a global village where vast distances are now much shorter due to new technology that make travel and communication more accessible and convenient (McLuhan, 1967). However, as the following “Getting Plugged In” box indicates, there is also a digital divide , which refers to the unequal access to technology and related skills that exists in much of the world. People in most fields will be more successful if they are prepared to work in a globalized world. Obviously, the global market sets up the need to have intercultural competence for employees who travel between locations of a multinational corporation. Perhaps less obvious may be the need for teachers to work with students who do not speak English as their first language and for police officers, lawyers, managers, and medical personnel to be able to work with people who have various cultural identities.

“Getting Plugged In”

The Digital Divide

Many people who are now college age struggle to imagine a time without cell phones and the Internet. As “digital natives” it is probably also surprising to realize the number of people who do not have access to certain technologies. The digital divide was a term that initially referred to gaps in access to computers. The term expanded to include access to the Internet since it exploded onto the technology scene and is now connected to virtually all computing (van Deursen & van Dijk, 2010). Approximately two billion people around the world now access the Internet regularly, and those who don’t face several disadvantages (Smith, 2011). Discussions of the digital divide are now turning more specifically to high-speed Internet access, and the discussion is moving beyond the physical access divide to include the skills divide, the economic opportunity divide, and the democratic divide. This divide doesn’t just exist in developing countries; it has become an increasing concern in the United States. This is relevant to cultural identities because there are already inequalities in terms of access to technology based on age, race, and class (Sylvester & McGlynn, 2010). Scholars argue that these continued gaps will only serve to exacerbate existing cultural and social inequalities. From an international perspective, the United States is falling behind other countries in terms of access to high-speed Internet. South Korea, Japan, Sweden, and Germany now all have faster average connection speeds than the United States (Smith, 2011). And Finland in 2010 became the first country in the world to declare that all its citizens have a legal right to broadband Internet access (ben-Aaron, 2010). People in rural areas in the United States are especially disconnected from broadband service, with about 11 million rural Americans unable to get the service at home. As so much of our daily lives go online, it puts those who aren’t connected at a disadvantage. From paying bills online, to interacting with government services, to applying for jobs, to taking online college classes, to researching and participating in political and social causes, the Internet connects to education, money, and politics.

- What do you think of Finland’s inclusion of broadband access as a legal right? Is this something that should be done in other countries? Why or why not?

- How does the digital divide affect the notion of the global village?

- How might limited access to technology negatively affect various nondominant groups?

Intercultural Communication: A Dialectical Approach

Intercultural communication is complicated, messy, and at times contradictory. Therefore it is not always easy to conceptualize or study. Taking a dialectical approach allows us to capture the dynamism of intercultural communication. A dialectic is a relationship between two opposing concepts that constantly push and pull one another (Martin & Nakayama, 2010). To put it another way, thinking dialectically helps us realize that our experiences often occur in between two different phenomena. This perspective is especially useful for interpersonal and intercultural communication, because when we think dialectically, we think relationally. This means we look at the relationship between aspects of intercultural communication rather than viewing them in isolation. Intercultural communication occurs as a dynamic in-betweenness that, while connected to the individuals in an encounter, goes beyond the individuals, creating something unique. Holding a dialectical perspective may be challenging for some Westerners, as it asks us to hold two contradictory ideas simultaneously, which goes against much of what we are taught in our formal education. Thinking dialectically helps us see the complexity in culture and identity because it doesn’t allow for dichotomies. Dichotomies are dualistic ways of thinking that highlight opposites, reducing the ability to see gradations that exist in between concepts. Dichotomies such as good/evil, wrong/right, objective/subjective, male/female, in-group/out-group, black/white, and so on form the basis of much of our thoughts on ethics, culture, and general philosophy, but this isn’t the only way of thinking (Marin & Nakayama, 1999). Many Eastern cultures acknowledge that the world isn’t dualistic. Rather, they accept as part of their reality that things that seem opposite are actually interdependent and complement each other. I argue that a dialectical approach is useful in studying intercultural communication because it gets us out of our comfortable and familiar ways of thinking. Since so much of understanding culture and identity is understanding ourselves, having an unfamiliar lens through which to view culture can offer us insights that our familiar lenses will not. Specifically, we can better understand intercultural communication by examining six dialectics (see Figure 8.1 “Dialectics of Intercultural Communication” ) (Martin & Nakayama, 1999).

Figure 8.1 Dialectics of Intercultural Communication

Source: Adapted from Judith N. Martin and Thomas K. Nakayama, “Thinking Dialectically about Culture and Communication,” Communication Theory 9, no. 1 (1999): 1–25.

The cultural-individual dialectic captures the interplay between patterned behaviors learned from a cultural group and individual behaviors that may be variations on or counter to those of the larger culture. This dialectic is useful because it helps us account for exceptions to cultural norms. For example, earlier we learned that the United States is said to be a low-context culture, which means that we value verbal communication as our primary, meaning-rich form of communication. Conversely, Japan is said to be a high-context culture, which means they often look for nonverbal clues like tone, silence, or what is not said for meaning. However, you can find people in the United States who intentionally put much meaning into how they say things, perhaps because they are not as comfortable speaking directly what’s on their mind. We often do this in situations where we may hurt someone’s feelings or damage a relationship. Does that mean we come from a high-context culture? Does the Japanese man who speaks more than is socially acceptable come from a low-context culture? The answer to both questions is no. Neither the behaviors of a small percentage of individuals nor occasional situational choices constitute a cultural pattern.

The personal-contextual dialectic highlights the connection between our personal patterns of and preferences for communicating and how various contexts influence the personal. In some cases, our communication patterns and preferences will stay the same across many contexts. In other cases, a context shift may lead us to alter our communication and adapt. For example, an American businesswoman may prefer to communicate with her employees in an informal and laid-back manner. When she is promoted to manage a department in her company’s office in Malaysia, she may again prefer to communicate with her new Malaysian employees the same way she did with those in the United States. In the United States, we know that there are some accepted norms that communication in work contexts is more formal than in personal contexts. However, we also know that individual managers often adapt these expectations to suit their own personal tastes. This type of managerial discretion would likely not go over as well in Malaysia where there is a greater emphasis put on power distance (Hofstede, 1991). So while the American manager may not know to adapt to the new context unless she has a high degree of intercultural communication competence, Malaysian managers would realize that this is an instance where the context likely influences communication more than personal preferences.

The differences-similarities dialectic allows us to examine how we are simultaneously similar to and different from others. As was noted earlier, it’s easy to fall into a view of intercultural communication as “other oriented” and set up dichotomies between “us” and “them.” When we overfocus on differences, we can end up polarizing groups that actually have things in common. When we overfocus on similarities, we essentialize , or reduce/overlook important variations within a group. This tendency is evident in most of the popular, and some of the academic, conversations regarding “gender differences.” The book Men Are from Mars and Women Are from Venus makes it seem like men and women aren’t even species that hail from the same planet. The media is quick to include a blurb from a research study indicating again how men and women are “wired” to communicate differently. However, the overwhelming majority of current research on gender and communication finds that while there are differences between how men and women communicate, there are far more similarities (Allen, 2011). Even the language we use to describe the genders sets up dichotomies. That’s why I suggest that my students use the term other gender instead of the commonly used opposite sex . I have a mom, a sister, and plenty of female friends, and I don’t feel like any of them are the opposite of me. Perhaps a better title for a book would be Women and Men Are Both from Earth .

The static-dynamic dialectic suggests that culture and communication change over time yet often appear to be and are experienced as stable. Although it is true that our cultural beliefs and practices are rooted in the past, we have already discussed how cultural categories that most of us assume to be stable, like race and gender, have changed dramatically in just the past fifty years. Some cultural values remain relatively consistent over time, which allows us to make some generalizations about a culture. For example, cultures have different orientations to time. The Chinese have a longer-term orientation to time than do Europeans (Lustig & Koester, 2006). This is evidenced in something that dates back as far as astrology. The Chinese zodiac is done annually (The Year of the Monkey, etc.), while European astrology was organized by month (Taurus, etc.). While this cultural orientation to time has been around for generations, as China becomes more Westernized in terms of technology, business, and commerce, it could also adopt some views on time that are more short term.

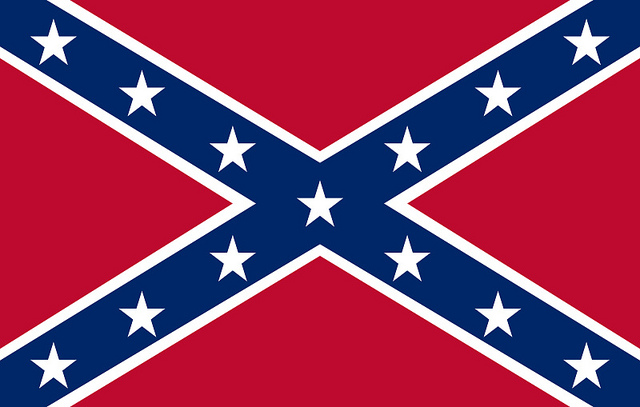

The history/past-present/future dialectic reminds us to understand that while current cultural conditions are important and that our actions now will inevitably affect our future, those conditions are not without a history. We always view history through the lens of the present. Perhaps no example is more entrenched in our past and avoided in our present as the history of slavery in the United States. Where I grew up in the Southern United States, race was something that came up frequently. The high school I attended was 30 percent minorities (mostly African American) and also had a noticeable number of white teens (mostly male) who proudly displayed Confederate flags on their clothing or vehicles.

There has been controversy over whether the Confederate flag is a symbol of hatred or a historical symbol that acknowledges the time of the Civil War.

Jim Surkamp – Confederate Rebel Flag – CC BY-NC 2.0.

I remember an instance in a history class where we were discussing slavery and the subject of repatriation, or compensation for descendants of slaves, came up. A white male student in the class proclaimed, “I’ve never owned slaves. Why should I have to care about this now?” While his statement about not owning slaves is valid, it doesn’t acknowledge that effects of slavery still linger today and that the repercussions of such a long and unjust period of our history don’t disappear over the course of a few generations.

The privileges-disadvantages dialectic captures the complex interrelation of unearned, systemic advantages and disadvantages that operate among our various identities. As was discussed earlier, our society consists of dominant and nondominant groups. Our cultures and identities have certain privileges and/or disadvantages. To understand this dialectic, we must view culture and identity through a lens of intersectionality , which asks us to acknowledge that we each have multiple cultures and identities that intersect with each other. Because our identities are complex, no one is completely privileged and no one is completely disadvantaged. For example, while we may think of a white, heterosexual male as being very privileged, he may also have a disability that leaves him without the able-bodied privilege that a Latina woman has. This is often a difficult dialectic for my students to understand, because they are quick to point out exceptions that they think challenge this notion. For example, many people like to point out Oprah Winfrey as a powerful African American woman. While she is definitely now quite privileged despite her disadvantaged identities, her trajectory isn’t the norm. When we view privilege and disadvantage at the cultural level, we cannot let individual exceptions distract from the systemic and institutionalized ways in which some people in our society are disadvantaged while others are privileged.

As these dialectics reiterate, culture and communication are complex systems that intersect with and diverge from many contexts. A better understanding of all these dialectics helps us be more critical thinkers and competent communicators in a changing world.

“Getting Critical”

Immigration, Laws, and Religion

France, like the United States, has a constitutional separation between church and state. As many countries in Europe, including France, Belgium, Germany, the Netherlands, and Sweden, have experienced influxes of immigrants, many of them Muslim, there have been growing tensions among immigration, laws, and religion. In 2011, France passed a law banning the wearing of a niqab (pronounced knee-cobb ), which is an Islamic facial covering worn by some women that only exposes the eyes. This law was aimed at “assimilating its Muslim population” of more than five million people and “defending French values and women’s rights” (De La Baume & Goodman, 2011). Women found wearing the veil can now be cited and fined $150 euros. Although the law went into effect in April of 2011, the first fines were issued in late September of 2011. Hind Ahmas, a woman who was fined, says she welcomes the punishment because she wants to challenge the law in the European Court of Human Rights. She also stated that she respects French laws but cannot abide by this one. Her choice to wear the veil has been met with more than a fine. She recounts how she has been denied access to banks and other public buildings and was verbally harassed by a woman on the street and then punched in the face by the woman’s husband. Another Muslim woman named Kenza Drider, who can be seen in Video Clip 8.2, announced that she will run for the presidency of France in order to challenge the law. The bill that contained the law was broadly supported by politicians and the public in France, and similar laws are already in place in Belgium and are being proposed in Italy, Austria, the Netherlands, and Switzerland (Fraser, 2011).

- Some people who support the law argue that part of integrating into Western society is showing your face. Do you agree or disagree? Why?

- Part of the argument for the law is to aid in the assimilation of Muslim immigrants into French society. What are some positives and negatives of this type of assimilation?

- Identify which of the previously discussed dialectics can be seen in this case. How do these dialectics capture the tensions involved?

Video Clip 8.2

Veiled Woman Eyes French Presidency

(click to see video)

Intercultural Communication and Relationships

Intercultural relationships are formed between people with different cultural identities and include friends, romantic partners, family, and coworkers. Intercultural relationships have benefits and drawbacks. Some of the benefits include increasing cultural knowledge, challenging previously held stereotypes, and learning new skills (Martin & Nakayama, 2010). For example, I learned about the Vietnamese New Year celebration Tet from a friend I made in graduate school. This same friend also taught me how to make some delicious Vietnamese foods that I continue to cook today. I likely would not have gained this cultural knowledge or skill without the benefits of my intercultural friendship. Intercultural relationships also present challenges, however.

The dialectics discussed earlier affect our intercultural relationships. The similarities-differences dialectic in particular may present challenges to relationship formation (Martin & Nakayama, 2010). While differences between people’s cultural identities may be obvious, it takes some effort to uncover commonalities that can form the basis of a relationship. Perceived differences in general also create anxiety and uncertainty that is not as present in intracultural relationships. Once some similarities are found, the tension within the dialectic begins to balance out and uncertainty and anxiety lessen. Negative stereotypes may also hinder progress toward relational development, especially if the individuals are not open to adjusting their preexisting beliefs. Intercultural relationships may also take more work to nurture and maintain. The benefit of increased cultural awareness is often achieved, because the relational partners explain their cultures to each other. This type of explaining requires time, effort, and patience and may be an extra burden that some are not willing to carry. Last, engaging in intercultural relationships can lead to questioning or even backlash from one’s own group. I experienced this type of backlash from my white classmates in middle school who teased me for hanging out with the African American kids on my bus. While these challenges range from mild inconveniences to more serious repercussions, they are important to be aware of. As noted earlier, intercultural relationships can take many forms. The focus of this section is on friendships and romantic relationships, but much of the following discussion can be extended to other relationship types.

Intercultural Friendships

Even within the United States, views of friendship vary based on cultural identities. Research on friendship has shown that Latinos/as value relational support and positive feedback, Asian Americans emphasize exchanges of ideas like offering feedback or asking for guidance, African Americans value respect and mutual acceptance, and European Americans value recognition of each other as individuals (Coller, 1996). Despite the differences in emphasis, research also shows that the overall definition of a close friend is similar across cultures. A close friend is thought of as someone who is helpful and nonjudgmental, who you enjoy spending time with but can also be independent, and who shares similar interests and personality traits (Lee, 2006).

Intercultural friendship formation may face challenges that other friendships do not. Prior intercultural experience and overcoming language barriers increase the likelihood of intercultural friendship formation (Sias et al., 2008). In some cases, previous intercultural experience, like studying abroad in college or living in a diverse place, may motivate someone to pursue intercultural friendships once they are no longer in that context. When friendships cross nationality, it may be necessary to invest more time in common understanding, due to language barriers. With sufficient motivation and language skills, communication exchanges through self-disclosure can then further relational formation. Research has shown that individuals from different countries in intercultural friendships differ in terms of the topics and depth of self-disclosure, but that as the friendship progresses, self-disclosure increases in depth and breadth (Chen & Nakazawa, 2009). Further, as people overcome initial challenges to initiating an intercultural friendship and move toward mutual self-disclosure, the relationship becomes more intimate, which helps friends work through and move beyond their cultural differences to focus on maintaining their relationship. In this sense, intercultural friendships can be just as strong and enduring as other friendships (Lee, 2006).

The potential for broadening one’s perspective and learning more about cultural identities is not always balanced, however. In some instances, members of a dominant culture may be more interested in sharing their culture with their intercultural friend than they are in learning about their friend’s culture, which illustrates how context and power influence friendships (Lee, 2006). A research study found a similar power dynamic, as European Americans in intercultural friendships stated they were open to exploring everyone’s culture but also communicated that culture wasn’t a big part of their intercultural friendships, as they just saw their friends as people. As the researcher states, “These types of responses may demonstrate that it is easiest for the group with the most socioeconomic and socio-cultural power to ignore the rules, assume they have the power as individuals to change the rules, or assume that no rules exist, since others are adapting to them rather than vice versa” (Collier, 1996). Again, intercultural friendships illustrate the complexity of culture and the importance of remaining mindful of your communication and the contexts in which it occurs.

Culture and Romantic Relationships

Romantic relationships are influenced by society and culture, and still today some people face discrimination based on who they love. Specifically, sexual orientation and race affect societal views of romantic relationships. Although the United States, as a whole, is becoming more accepting of gay and lesbian relationships, there is still a climate of prejudice and discrimination that individuals in same-gender romantic relationships must face. Despite some physical and virtual meeting places for gay and lesbian people, there are challenges for meeting and starting romantic relationships that are not experienced for most heterosexual people (Peplau & Spalding, 2000).

As we’ve already discussed, romantic relationships are likely to begin due to merely being exposed to another person at work, through a friend, and so on. But some gay and lesbian people may feel pressured into or just feel more comfortable not disclosing or displaying their sexual orientation at work or perhaps even to some family and friends, which closes off important social networks through which most romantic relationships begin. This pressure to refrain from disclosing one’s gay or lesbian sexual orientation in the workplace is not unfounded, as it is still legal in twenty-nine states (as of November 2012) to fire someone for being gay or lesbian (Human Rights Campaign, 2012). There are also some challenges faced by gay and lesbian partners regarding relationship termination. Gay and lesbian couples do not have the same legal and societal resources to manage their relationships as heterosexual couples; for example, gay and lesbian relationships are not legally recognized in most states, it is more difficult for a gay or lesbian couple to jointly own property or share custody of children than heterosexual couples, and there is little public funding for relationship counseling or couples therapy for gay and lesbian couples.

While this lack of barriers may make it easier for gay and lesbian partners to break out of an unhappy or unhealthy relationship, it could also lead couples to termination who may have been helped by the sociolegal support systems available to heterosexuals (Peplau & Spalding, 2000).

Despite these challenges, relationships between gay and lesbian people are similar in other ways to those between heterosexuals. Gay, lesbian, and heterosexual people seek similar qualities in a potential mate, and once relationships are established, all these groups experience similar degrees of relational satisfaction (Peplau & Spalding, 2000). Despite the myth that one person plays the man and one plays the woman in a relationship, gay and lesbian partners do not have set preferences in terms of gender role. In fact, research shows that while women in heterosexual relationships tend to do more of the housework, gay and lesbian couples were more likely to divide tasks so that each person has an equal share of responsibility (Peplau & Spalding, 2000). A gay or lesbian couple doesn’t necessarily constitute an intercultural relationship, but as we have already discussed, sexuality is an important part of an individual’s identity and connects to larger social and cultural systems. Keeping in mind that identity and culture are complex, we can see that gay and lesbian relationships can also be intercultural if the partners are of different racial or ethnic backgrounds.

While interracial relationships have occurred throughout history, there have been more historical taboos in the United States regarding relationships between African Americans and white people than other racial groups. Antimiscegenation laws were common in states and made it illegal for people of different racial/ethnic groups to marry. It wasn’t until 1967 that the Supreme Court ruled in the case of Loving versus Virginia , declaring these laws to be unconstitutional (Pratt, 1995). It wasn’t until 1998 and 2000, however, that South Carolina and Alabama removed such language from their state constitutions (Lovingday.org, 2011). The organization and website lovingday.org commemorates the landmark case and works to end racial prejudice through education.

Even after these changes, there were more Asian-white and Latino/a-white relationships than there were African American–white relationships (Gaines Jr. & Brennan, 2011). Having already discussed the importance of similarity in attraction to mates, it’s important to note that partners in an interracial relationship, although culturally different, tend to be similar in occupation and income. This can likely be explained by the situational influences on our relationship formation we discussed earlier—namely, that work tends to be a starting ground for many of our relationships, and we usually work with people who have similar backgrounds to us.

There has been much research on interracial couples that counters the popular notion that partners may be less satisfied in their relationships due to cultural differences. In fact, relational satisfaction isn’t significantly different for interracial partners, although the challenges they may face in finding acceptance from other people could lead to stressors that are not as strong for intracultural partners (Gaines Jr. & Brennan, 2011). Although partners in interracial relationships certainly face challenges, there are positives. For example, some mention that they’ve experienced personal growth by learning about their partner’s cultural background, which helps them gain alternative perspectives. Specifically, white people in interracial relationships have cited an awareness of and empathy for racism that still exists, which they may not have been aware of before (Gaines Jr. & Liu, 2000).

The Supreme Court ruled in the 1967 Loving v. Virginia case that states could not enforce laws banning interracial marriages.

Bahai.us – CC BY-NC 2.0.

Key Takeaways

- Studying intercultural communication, communication between people with differing cultural identities, can help us gain more self-awareness and be better able to communicate in a world with changing demographics and technologies.

- A dialectical approach to studying intercultural communication is useful because it allows us to think about culture and identity in complex ways, avoiding dichotomies and acknowledging the tensions that must be negotiated.

- Intercultural relationships face some challenges in negotiating the dialectic between similarities and differences but can also produce rewards in terms of fostering self- and other awareness.

- Why is the phrase “Know thyself” relevant to the study of intercultural communication?

- Apply at least one of the six dialectics to a recent intercultural interaction that you had. How does this dialectic help you understand or analyze the situation?

- Do some research on your state’s laws by answering the following questions: Did your state have antimiscegenation laws? If so, when were they repealed? Does your state legally recognize gay and lesbian relationships? If so, how?

Allen, B. J., Difference Matters: Communicating Social Identity , 2nd ed. (Long Grove, IL: Waveland, 2011), 55.

ben-Aaron, D., “Bringing Broadband to Finland’s Bookdocks,” Bloomberg Businessweek , July 19, 2010, 42.

Chen, Y. and Masato Nakazawa, “Influences of Culture on Self-Disclosure as Relationally Situated in Intercultural and Interracial Friendships from a Social Penetration Perspective,” Journal of Intercultural Communication Research 38, no. 2 (2009): 94. doi:10.1080/17475750903395408.

Coller, M. J., “Communication Competence Problematics in Ethnic Friendships,” Communication Monographs 63, no. 4 (1996): 324–25.

De La Baume, M. and J. David Goodman, “First Fines over Wearing Veils in France,” The New York Times ( The Lede: Blogging the News ), September 22, 2011, accessed October 10, 2011, http://thelede.blogs.nytimes.com/2011/09/22/first-fines-over -wearing-full-veils-in-france .

Fraser, C., “The Women Defying France’s Fall-Face Veil Ban,” BBC News , September 22, 2011, accessed October 10, 2011, http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-europe-15023308 .

Gaines Jr. S. O., and Kelly A. Brennan, “Establishing and Maintaining Satisfaction in Multicultural Relationships,” in Close Romantic Relationships: Maintenance and Enhancement , eds. John Harvey and Amy Wenzel (Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum, 2011), 239.

Stanley O. Gaines Jr., S. O., and James H. Liu, “Multicultural/Multiracial Relationships,” in Close Relationships: A Sourcebook , eds. Clyde Hendrick and Susan S. Hendrick (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2000), 105.

Hofstede, G., Cultures and Organizations: Softwares of the Mind (London: McGraw-Hill, 1991), 26.

Human Rights Campaign, “Pass ENDA NOW”, accessed November 5, 2012, http://www.hrc.org/campaigns/employment-non-discrimination-act .

Lee, P., “Bridging Cultures: Understanding the Construction of Relational Identity in Intercultural Friendships,” Journal of Intercultural Communication Research 35, no. 1 (2006): 11. doi:10.1080/17475740600739156.

Loving Day, “The Last Laws to Go,” Lovingday.org , accessed October 11, 2011, http://lovingday.org/last-laws-to-go .

Lustig, M. W., and Jolene Koester, Intercultural Competence: Interpersonal Communication across Cultures , 2nd ed. (Boston, MA: Pearson, 2006), 128–29.

Martin, J. N., and Thomas K. Nakayama, Intercultural Communication in Contexts , 5th ed. (Boston, MA: McGraw-Hill, 2010), 4.

Martin, J. N., and Thomas K. Nakayama, “Thinking Dialectically about Culture and Communication,” Communication Theory 9, no. 1 (1999): 14.

McLuhan, M., The Medium Is the Message (New York: Bantam Books, 1967).

Peplau, L. A. and Leah R. Spalding, “The Close Relationships of Lesbians, Gay Men, and Bisexuals,” in Close Relationships: A Sourcebook , eds. Clyde Hendrick and Susan S. Hendrick (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2000), 113.

Pratt, R. A., “Crossing the Color Line: A Historical Assessment and Personal Narrative of Loving v. Virginia ,” Howard Law Journal 41, no. 2 (1995): 229–36.

Sias, P. M., Jolanta A. Drzewiecka, Mary Meares, Rhiannon Bent, Yoko Konomi, Maria Ortega, and Colene White, “Intercultural Friendship Development,” Communication Reports 21, no. 1 (2008): 9. doi:10.1080/08934210701643750.

Smith, P., “The Digital Divide,” New York Times Upfront , May 9, 2011, 6.

Sylvester, D. E., and Adam J. McGlynn, “The Digital Divide, Political Participation, and Place,” Social Science Computer Review 28, no. 1 (2010): 64–65. doi:10.1177/0894439309335148.

van Deursen, A. and Jan van Dijk, “Internet Skills and the Digital Divide,” New Media and Society 13, no. 6 (2010): 893. doi:10.1177/1461444810386774.

Communication in the Real World Copyright © 2016 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Essay on Intercultural Communication

Students are often asked to write an essay on Intercultural Communication in their schools and colleges. And if you’re also looking for the same, we have created 100-word, 250-word, and 500-word essays on the topic.

Let’s take a look…

100 Words Essay on Intercultural Communication

What is intercultural communication.

Intercultural communication is when people from different cultures talk and share ideas. It’s like when friends from different countries chat and learn from each other. It’s important because it helps us understand people who are not like us.

Why It Matters

When we talk to someone from another place, we can sometimes get confused because we do things differently. But by talking and listening, we learn new things and make new friends. It’s good for peace and working together.

Sometimes, talking with someone from a different culture can be hard. We might not speak the same language well, or we might have different ways of showing respect. It’s like learning a new game with different rules.

Learning and Growing

When we keep trying to communicate with people who are different from us, we get better at it. We start to see the world in new ways and understand that there are many ways to live and think.

250 Words Essay on Intercultural Communication

Intercultural communication is when people from different cultures talk to each other. Each culture has its own way of seeing the world, and this can make talking to each other both interesting and sometimes hard. It’s like each culture has its own set of rules for playing a game, and when we talk to someone from a different culture, we’re trying to play the same game, but with a different set of rules.

Why It’s Important

As our world becomes more connected, we meet more people from other places. If we learn how to talk to them well, we can make new friends, do business, and learn new things. It helps us to understand people who are not like us and to live together peacefully.

Sometimes, we might not understand what someone means because their culture uses words differently. Or we might do something that is polite in our culture but rude in theirs. This can lead to misunderstandings. But if we pay attention and try to learn from each other, we can get past these problems.

The best part about talking to people from other cultures is that we can learn so much. We find out about new foods, music, and ways of thinking. It’s like adding more colors to our box of crayons. The more we learn, the better we get at communicating and the more friends we can make all over the world.

Intercultural communication is not just about talking; it’s about understanding and sharing. It makes our world a more exciting and friendly place.

500 Words Essay on Intercultural Communication

Intercultural communication is when people from different cultures talk to each other and share ideas. Imagine you have friends from countries all around the world. When you chat with them, you’re practicing intercultural communication. It’s not just about speaking different languages but also understanding each other’s traditions, behaviors, and ways of thinking.

Why is it Important?

Our world is like a big, colorful quilt with each piece representing a different culture. When these pieces fit well together, the quilt looks beautiful. That’s why learning how to talk and understand people from other cultures is very important. It helps us make friends, work better with others, and live peacefully in our shared world. With good intercultural communication, we can learn a lot from each other and solve problems together.

Understanding Cultural Differences

Different cultures have their own rules for what is polite or not. For example, in some places, making direct eye contact is a good thing, while in others, it might be seen as rude. Also, a thumbs-up can mean something is good in one country but can be an insult in another. To communicate well across cultures, we need to learn about these differences and respect them.

Language Barriers

One big challenge in intercultural communication is the language barrier. When people don’t speak the same language well, it can lead to misunderstandings. That’s why it’s helpful to learn other languages or find other ways to share our thoughts, like with pictures or hand signs. Sometimes, just trying to speak a little bit of someone else’s language can show that you respect their culture, and they might appreciate your effort.

Non-Verbal Communication

A lot of what we say doesn’t come from our mouths but from our bodies. This is called non-verbal communication, like smiling, waving, or nodding. These signs can mean different things in different cultures. For example, a nod might mean “yes” in one place but “no” in another. So, it’s important to learn about these non-verbal cues to avoid confusion.

Listening and Empathy

Good communication is not just about talking; it’s also about listening. When we listen carefully to what others say, we show that we care about their thoughts. Being empathetic means trying to understand how others feel. When we listen and try to feel what others are feeling, we can get along better with people from all over the world.

Intercultural communication is like a bridge that connects people from different cultures. It’s not always easy, but it’s very rewarding. By being curious, respectful, and patient, we can learn to communicate well with anyone, no matter where they come from. This helps us make new friends, work well with others, and live happily in our big, diverse world. So next time you meet someone from a different culture, remember these tips, and you’ll be on your way to being a great intercultural communicator!

That’s it! I hope the essay helped you.

If you’re looking for more, here are essays on other interesting topics:

- Essay on Intelligent Design Vs Evolution

- Essay on Intelligence Inheritance

- Essay on Intellectual Vitality

Apart from these, you can look at all the essays by clicking here .

Happy studying!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- +44 0330 027 0207

- +1 (818) 532-6908

- [email protected]

- e-Learning Courses Online

- You are here:

What is Intercultural Communication and Why is it Important?

Intercultural Communication is a mammoth topic.

It has so many facets, angles and sub-topics that doing it any real justice requires lengthy and considered research.

So, rather than try to give some sort of all-encompassing guide to Intercultural Communication , with all its ins and outs, we’re going to keep it simple.

We’re going to focus on 10 answers to 10 commonly asked questions about Intercultural Communication that will offer some great initial insights and answer the question posed, “ What is Intercultural Communication and why is it important?”

You’ll find plenty of links to further reading along the way if you want to take your learning to the next level.

DON’T MISS THE FREE SAMPLE OF OUR ELEARNING COURSE IN QUESTION 10!

Click Below to Skip to a Question or Scroll On

- What is the Definition of Intercultural Communication?

- What is Intercultural Communication in Simple Terms?

- What are Some Examples of Intercultural Communication?

- What is the Purpose of Intercultural Communication?

- What Makes Intercultural Communication Important?

- What are Intercultural Communication Skills?

- What is the Role of Intercultural Communication in Work Life?

- What is Intercultural Business Communication?

- What Can I Do to Improve My Intercultural Communication Skills?

- What are Some Essential Books About Intercultural Communication?

1. What is the Definition of Intercultural Communication?

“‘Intercultural Communication’ is one of those terms that everybody uses, and in many different and not necessarily compatible ways. ” (Intercultural Communication: A Critical Introduction. Ingrid Piller. 2017)

“Loosely, an umbrella term for interaction between people from different cultural or subcultural backgrounds intended to lead to shared understandings of messages.” (Oxford Reference)

“Intercultural communication is a discipline that studies communication across different cultures and social groups, or how culture affects communication.” (Wikipedia)

“Intercultural communication is the study and practice of communication across cultural contexts.” (Milton J. Bennett, Ph.D. Intercultural Development Research Institute)

There is no formal definition of ‘Intercultural Communication’.

As you can see from the quotes above, there is a fuzzy agreement as to what it does and what it looks like , but there are also differences in definitions, meanings and assumptions.

As training practitioners within the Intercultural field, we define Intercultural Communication as the study, research, awareness, training, skills, and practicalities of communicating across cultures – whether those cultures be foreign cultures, i.e. American culture vs. Indian culture , or some other sort of culture, such as organizational culture, i.e. Military Culture vs. Private Sector Culture .

Cultural differences exist between many types of cultures, including generational. We can see this expressed in lots of ways including differences in the way they dress, walk and, of course, communicate. Photo by Benjamin Ranger

2. What is Intercultural Communication in Simple Terms?

Simply put, Intercultural Communication is about understanding what happens when people communicate with one another when they come from different cultures.

It’s about an awareness of many different factors such as how messages are delivered (e.g. listening and speaking ), differences in areas such body language (e.g. eye contact , touch, gestures, etc.) and non-verbal communication (e.g. silence, proxemics, social cues, etc.).

Intercultural Communication, as well as being its own discipline, overlaps with many others including sociology, psychology, anthropology , biology, political science, economics, and public policy.

An easy way to think about Intercultural Communication is that it tries to teach us about ourselves, as individuals and as a species, by using the concept of ‘culture’ to analyze how we create meaning and express that with other cultures.

“Intercultural communication is a symbolic, interpretive, transactional, contextual process, in which people from different cultures create shared meanings.” (Lustig & Koester, Intercultural competence 2007)

At its most basic, as the above quote illustrates, Intercultural Communication is as simple as a conversation or an interaction between two or more people from different cultures.

Intercultural Communication also covers the ways in which we, as cultures, meet and greet people. Learning how other cultures do it, teaches us about our similarities and differences. Photo by Bob Brewer

3. What are Some Examples of Intercultural Communication?

Let’s look at some examples of Intercultural Communication to help consolidate our understanding of the definition and meanings associated with it.

We mentioned above the example of communication differences between national cultures . Well, let’s explore that further.

American and Indian cultures share certain cultural traits when it comes to communication. For example, they both tend to value politeness and friendliness. However, they also have differences. For example:

- Americans tend to communicate explicitly whereas Indians to be implicit.

- Americans are comfortable with dealing with conflict openly whereas in Indian culture it requires subtlety.

- In the USA, “yes” may have very limited interpretations whereas in India, “yes” can mean many things.

- Strong eye contact is a positive behavior in the USA whereas in India it can be disrespectful or aggressive.

- Personal space is expected in the USA whereas in India keeping your distance from someone could be interpreted as rude or cold.

The key learning point here is that different national cultures communicate in slightly different ways.

This is also true within countries themselves – you often find subtle regional differences within a country or culture in terms of communication styles.

For example, in the UK , the people of the North are widely recognized as being much more open and friendly than their guarded countrymen in the South and London. In the USA, you will also see differences between the East and West coasts as well as the South.

The other example we mentioned above was between Military Culture and Private Sector Culture . Again, as with national cultures, we can also see different communication styles between organizations within a country.

Military organizations are highly hierarchical, conservative and formal. This is reflected in the communication style where seniors are spoken to according to protocols, where messages are transactional and the language, tone and vocabulary are highly regimented.

This starkly contradicts the communication style of the Private sector where organizations are more egalitarian, open to change and informal. As a result, the communication style is much more informal, messages are personalized and people are allowed to express themselves.

Such differences, created by different cultures, can even be found within an organization itself. For example, salespeople generally tend to have a very different communication style to their colleagues working in accounts or at leadership levels. The reason behind the difference is cultural and also due to values .

Organizations, like countries, develop their own cultures due to many factors such as the environment, threat, philosophy, leadership and history. Culture is a complex patchwork of influences. Photo by Bao Menglong

4. What is the Purpose of Intercultural Communication?

Well, there isn’t one single purpose. Intercultural Communication is something that is researched, read about and taught for many reasons.

For starters, understanding how culture impacts communication helps us understand more about the areas of culture and communication. On top of that, it helps us understand more about ourselves as people and as a species.

On a personal level , Intercultural Communication can help us understand our own preferences, strengths and weaknesses when it comes to communicating and how these can help or hinder us when communicating across cultures.

On a wider level, Intercultural Communication can help us understand all manner of things about ourselves as human beings from how we create meaning to the mechanics of the brain (neuroscience) to the use of language(s) for social cohesion.

As practitioners of Intercultural Communication Training , ‘the purpose’ for us is to help professionals understand how culture impacts their effectiveness when working abroad or in a multicultural workplace.

For example, when we train an executive moving to the UAE , we will help them appreciate their own way of communicating, what they like and don’t like as well as possible biases they may hold. On top of this, they would also learn about the communication style in the UAE and potential areas of culture clash.

So, in this context, the purpose of Intercultural Communication is to try and prevent miscommunication and a mismatch of communication styles . Through raising awareness of this through training, it helps promote more successful communication.

Another example would be of a multicultural team we provide training for. In such a training course we would help the different team members understand the various communication styles within the team. Through creating an awareness of the difference, and the reasoning behind it, we help colleagues overcome issues and put into place different ways of doing things.

So, in this context, Intercultural Communication is about understanding how to effectively navigate various communication styles found in the various cultures you work with.

With more and more of us working remotely with people around the world, learning about Intercultural Communication has become necessary for both personal and organizational success. Photo by Katsiaryna Endruszkiewicz

5. What Makes Intercultural Communication Important?

A few reasons why Intercultural Communication is important have already been covered; namely, it helps people understand each other and avoid confusion.

Let’s give this a bit more context by looking at why Intercultural Communication is so important for many people in the workplace.

a. Intercultural Communication and Teamwork

Many of today’s companies and organizations are multicultural. Employees come from around the world. This is not only the case with global and international brands but also domestic companies and organizations (including the Third Sector) which have culturally diverse employees. Learning to communicate and work with people from different cultures is essential if these organizations want to be successful. So, in this regard, Intercultural Communication is important because it helps teamwork .

b. Intercultural Communication and the Military

Believe it or not, many militaries spend a lot of money on teaching their troops Intercultural Communication. Why? Because when they spend time in foreign countries, they must learn to adapt their communication style in order to ingratiate themselves with the locals, or at least, in order to gain intelligence . In the USA, for example, the Army , Navy and Marine Corps (plus others) all offer training in Intercultural Communication or similar. I n this context, Intercultural Communication is important as it could be the difference between life or death.

c. Intercultural Communication and Healthcare

Another field in which Intercultural Communication can mean life or death is in healthcare. Doctors, nurses and medical professionals are now given training in Cultural Competence in order to improve healthcare for all patients . An ignorance of someone’s culture and how they communicate can lead to poor care, misdiagnosis and potential damage to health. For example, if a doctor doesn’t understand that in some cultures the elderly won’t divulge intimate details in front of family members, that Doctor is not going to get the information they need when a son or daughter brings in an elderly parent. They need to understand this and ask the child to leave so a private conversation can be had. So, in this example, Intercultural Communication is important as it ensures good care.

d. Intercultural Communication and Teaching

For teaching professionals working in multicultural schools, learning about Intercultural Communication is essential as it otherwise can lead to discrimination, bias and alienation of children from different backgrounds. Some cultures teach their kids to be quiet and respect authority, others to be expressive and challenge ideas. Some cultures wait to be asked to speak, others speak when they have something to say. The point is, as a teacher if you don’t understand the different ways your students communicate , you can make some bad judgement calls. In the context of school and education, Intercultural Communication is important because it prevents bad teaching.

e. Intercultural Communication and Marketing/Advertising

A final example of the importance of Intercultural Communication is the marketing and advertising industry. A failure to understand differences in communication around the world can lead to all sorts of marketing fails and PR disasters. A lack of awareness over cultural issues can even lead to claims of cultural appropriation and similar. Today the industry is much more culture-savvy, understanding that to run a successful ad or marketing campaign, it has to be in tune with the target audience and their values. So, in this regard, Intercultural Communication is important because it helps brands reach their audiences.

So, as you can see, Intercultural Communication is important for lots of reasons; probably too many to count.

Pretty much every facet of modern-day life needs some awareness of Intercultural Communication , whether that’s for tourists travelling abroad on vacation, businesspeople negotiating a merger or a lecturer with students from around the world.

Self-reflection is critical for those who want to improve their Intercultural Communication skills. Photo by Laurenz Kleinheider

6. What are Intercultural Communication Skills?

Intercultural Communication requires multiple skills, some of which can be learned, others that all of us possess and just need working on.

Let’s examine a few of the most important Intercultural Communication Skills that focus more on personal competencies rather than communication skills such as listening, speaking, body language, etc.

a. Self-Awareness

The key to understanding how other cultures communicate is to understand how you, yourself communicate and how your culture has shaped you. Once you are more aware of your own preferences, habits and possible biases and stereotypes, then it’s much easier to understand how you may influence or impact a conversation or communication. Intercultural Communication is not only about being aware of ‘the other’ but also yourself .

Appreciating that you have been shaped by your culture and other influences, helps create understanding, compassion, mindfulness and empathy . Empathy is critical to Intercultural Communication as it helps you put yourself in someone else’s shoes and understand what they may be going through. Intercultural Communication relies on empathy as it creates a two-way street as opposed to being dominated by one or the other party.

With understanding and empathy, respect should be the natural logical progression. Respect means that you may not agree or like everything about someone else or their culture, but that you acknowledge their right to express themselves, their culture or values. Also, without showing respect it is also hard to receive it. Intercultural Communication can only ever be effective if respect is the foundation.

d. Emotional Intelligence

Working across cultures means learning to tune yourself into much of the unseen, intangible and subtle aspects of communication. It’s about using all your senses and engaging your self-awareness and empathy to understand what’s being communicated, or not. The Japanese have a great term for this, ‘Reading the air’ ( kuuki o yomu in Japanese) which brilliantly captures the mindset needed. Intercultural Communication requires intuition and the ability to move beyond words.

e. Adaptability

In some ways, the essence of Intercultural Communication is to help people adjust their communication styles to promote clarity, harmony and collaboration in exchange for confusion, weak relationships and competition. Therefore, we need to be adaptable – adaptable not only in how we talk and listen and use body language but adaptable in how we think, react and engage with people. Intercultural Communication gives us the insights and tools we need to be flexible and adapt our ways.

f. Patience

“Acquaintance without patience is like a candle with no light,” is a Persian proverb that perfectly captures why this is such an important skill when it comes to communicating across cultures . Things work slightly differently around the world; this means things might take more time than you’re used to, or less! Whichever end of the stick you’re dealing with, patience is necessary for effective Intercultural Communication as it moderates expectations and emotions.

g. Positivity

When engaging with people from different cultures, it’s always important to keep things positive. 99% of the time when miscommunication happens it’s not because anyone purposefully tried to confuse someone else. Most people are just trying to do what’s right. Sometimes, if we lack cultural awareness , we misread what’s being communicated. That’s why we need to always frame any sort of intercultural interaction positively. To be fruitful, Intercultural Communication must come with positive intentions.

There are of course many other skills that are an important part of Intercultural Communication but hopefully, this has given you some solid points to consider.

So, to quickly recap, 7 important Intercultural Communication skills are:

- Self-Awareness

- Emotional Intelligence

- Adaptability

Many workplaces today are culturally diverse, making Intercultural Communication skills essential. Photo by Arlington Research

7. What is the Role of Intercultural Communication in Work Life?

The answer to this question really depends on what ‘work’ you’re thinking about. We like to speak from experience, so let’s look at some examples of Intercultural Training we have provided for clients .

These will give you an idea of some of the common challenges professionals in various contexts have to deal with in the workplace and how learning about Intercultural Communication helps them.

a. Intercultural Communication and Meetings

We did some training for a global fashion brand and its team of international managers. Various members of the team were frustrated with the way online virtual meetings were being run. For example: “The Americans give you zero time to think and move onto the next point.” vs. “The Chinese never give their opinions which is really frustrating.”

This came down to cultural differences around expectations of meetings. The Americans wanted frank, open discussions whereas the Chinese preferred non-confrontational meetings that focused on face. Due to a lack of awareness, the team meetings were not working. By raising awareness through training, the team learned to find a balance that worked for all.

So, the role of Intercultural Communication here was to help people understand their differences and find common ground.

b. Intercultural Communication and Management

Another example that shows how communication styles differ across cultures and why it’s necessary to be adaptable, is some Intercultural Training we did for a German organization. With staff all over the globe, German managers were consistently receiving positive feedback from some countries and terrible feedback from others. In many parts of the world, they were seen as ‘distant’ and ‘impersonal’.

What the managers needed to learn to do was become a bit more relationship-focused in their communication as opposed to focusing on tasks and agendas. In some parts of the world, ‘getting down to business' is not dealt with positively and people expect a bit more ‘warmth’. The managers just needed to be shown what was happening and they learned to adapt their communication style accordingly.

So, the role of Intercultural Communication here was to help managers communicate more effectively with their staff and get more positive feedback.

c. Intercultural Communication and Working Abroad

A final example would be one of the many training courses we provide for professionals relocating to a foreign country for work. Moving to another county means learning a new culture and if you fail to appreciate cultural differences, it can result in some bad decisions. For example, one manager from Europe working in Saudi Arabia nearly got the sack for berating his staff!

Professionals who fail to invest some time and energy in understanding the new host culture can take longer to settle in, make more initial mistakes and generally don’t’ make a great first impression. The statistics show that this is also one of the key reasons why relocations fail, i.e. why people return ‘home’ quicker.

So, the role of Intercultural Communication here is to give people the tools they need to navigate a new culture and to help them settle into a country or job.

By way of summarizing, the role of Intercultural Communication in work life is in helping people understand how culture shapes the different ways we communicate, collaborate and coordinate.

We can use this understanding to help us recognize what is being communicated to us and how we communicate with others.

Doing business successfully across the globe requires the ability to communicate and convince effectively. Photo by Cytonn Photography

8. What is Intercultural Business Communication?

‘Intercultural Business Communication’ refers specifically to interpersonal and structural communication within a professional business context.

The examples above from our Intercultural Training courses were all focused on Intercultural Business Communication as opposed to communication taking place within social services, the military, diplomatic services or healthcare.

Different industries and sectors have very different needs. Yes, there may be some overlap between the needs of a surgeon, a taxi driver , a police officer and a politician, however, when it comes to the specifics, you need focus.

Therefore, Intercultural Business Communication is treated separately as the needs of people within business are specific to the way trade, commerce and enterprise are conducted around the world.

Business as a whole understands that they have their own challenges when it comes to the 'culture question' . This is being reflected in the number of University Degrees now entitled “Intercultural Business Communication” which have been developed to fill the need of global businesses looking to hire people with the skills they need.

Courses focus on key business areas to prepare learners for international careers including topics such as:

- Human Resource Management

- Developing Intercultural Competence

- Global Marketing

- Business Communication

- International Business Event Management

- Organizational Change and Management

- Understanding Language in the Global Workplace

‘Intercultural Business Communication’ covers everything from the big (such as how to launch retail products in a foreign market ) to the small (such as how to avoid using humor inappropriately ) and everything in between.

If you're looking for a good book on Intercultural Communication for your next vacation, we've got plenty to recommend! Photo by Dan Dumitriu

9. What are Some Essential Books About Intercultural Business Communication?

If you’re looking for good books on Intercultural Business Communication, you’re spoilt for choice! There are many tens of books published on the subject looking at it from lots of different angles.

If there’s something you’re specifically interested in, then we recommend you do a search to see what books come up. You can also do a search for academic publications, for example with JSTOR .

If you want a decent overview of some of the important books on Intercultural Communication, then we recommend this list by Good Reads which is very comprehensive.

If you want our opinion on some essential books about Intercultural Business Communication , then here’s our top 5 (in no particular order or rank).

- Basic Concepts of Intercultural Communication: Paradigms, Principles, & Practices . Bennett, Milton Boston, Intercultural Press 2013

- The Silent Language . Hall, Edward T. Garden City: Doubleday 1959

- Understanding Intercultural Communication . Ting-Toomey, Stella & Chung, Leeva., Oxford University Press 2011

- Intercultural Business Communication. Robert Gibson, Oxford University Press 2000

- Use Your Difference to Make a Difference: How to Connect and Communicate in a Cross-Cultural World . Tayo Rockson, Wiley 2019

Improving your Intercultural Communication skills means you need to be culturally curious. Photo by Yingchou Han

10. What Can I Do to Improve My Intercultural Communication Skills?

If you want to improve your Intercultural Communication skills, then there are several things you can do to get started.

Obviously travelling abroad , learning a language and mixing with people from different cultures are all excellent ways of improving your Intercultural Communication skills, however, these aren’t very easy for most people. Plus, it takes a lot of time.

So, we’re going to focus on giving you some more simple and tangible things you can do instead.

a. Learn about Culture

Learning about other cultures, their values and their communication preferences will offer a lot of insight into differences around the world. There are plenty of websites that offer cultural overviews which you can find online, including our award-winning culture guides . As well as learning about other cultures , it’s also a good idea to learn about some of the basics of Intercultural Communication. A good place to start is this self-study guide to intercultural communication.

b. Watch TV Shows

Most of us like to watch TV shows, so why not watch TV and learn about different cultures at the same time? Rather than listen to a poorly dubbed foreign movie in English, listen to it in its native language so you can hear how people from that country communicate. Streaming services today such as Netflix have TV series from around the world, so if you want to learn about Indian culture , Turkish culture or Chinese culture, it’s all there!

c. Ask People

If you work with people from different countries or have neighbours from abroad, you have excellent untapped resources. Speaking to people about their cultures and about any ‘culture shock’ they may have experienced living in your country, can give you all sorts of rich information and insights. As long as it’s done with respect, most people around the world love to share their opinions and thoughts.

d. Listen & Observe

When it comes to actual communication, there are all sorts of tips to help you improve your Intercultural Skills. For example, learning to ask open and closed questions where needed or avoiding humor. Here’s a list of 10 simple tips if you want to read more . Perhaps the two most important tips when it comes to communication are to listen more than you normally would and also actively observe what others are doing .

e. Take a Course

Finally, if you want to start peeling away your own cultural make-up, address your own cultural biases and preferences, plus start to learn more about Intercultural Communication, then why not take a course? There are plenty of courses available online which looks at various aspects, however, to get you started you can watch the free video from our eLearning course on Cultural Awareness. It’s a fantastic introduction to the topic of cultural differences, communicating across cultures and working with cultural diversity.

You can watch it below or if you visit the course page you can also access some free course resources and find out more about the contents .

THANKS FOR READING OUR INTRO TO INTERCULTURAL COMMUNICATION! WE HOPE YOU FOUND IT USEFUL.

IF YOU WANT TO LEARN MORE ABOUT OTHER CULTURES, THEN CLICK HERE TO CHECK OUT ALL OUR FREE RESOURCES !

By accepting you will be accessing a service provided by a third-party external to https://www.commisceo-global.com/

34 New House, 67-68 Hatton Garden, London EC1N 8JY, UK. 1950 W. Corporate Way PMB 25615, Anaheim, CA 92801, USA. +44 0330 027 0207 or +1 (818) 532-6908

34 New House, 67-68 Hatton Garden, London EC1N 8JY, UK. 1950 W. Corporate Way PMB 25615, Anaheim, CA 92801, USA. +44 0330 027 0207 +1 (818) 532-6908

Search for something

Home — Essay Samples — Sociology — Intercultural Communication — Intercultural Communication: Understanding, Challenges, and Importance

Intercultural Communication: Understanding, Challenges, and Importance

- Categories: Intercultural Communication

About this sample

Words: 2184 |

11 min read

Published: Aug 14, 2023

Words: 2184 | Pages: 5 | 11 min read

Table of contents

Introduction, the meaning of culture, communication as a part of intercultural communication, intercultural communication defined, the importance of studying intercultural communication, barriers to intercultural communication.

- Understanding your own identity.

- Enhancing personal and social interactions.Solving misunderstandings, miscommunications & mistrust.

- Enhancing and enriching the quality of civilization.

- Becoming effective citizens of our national communities

- Ethnocentrism

- Stereotyping

- Discrimination

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Dr. Heisenberg

Verified writer

- Expert in: Sociology

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

5 pages / 2486 words

2 pages / 1111 words

5 pages / 2229 words

1 pages / 581 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Intercultural Communication

In a world that constantly brings individuals from diverse backgrounds together, the complexities and implications of interacting with strangers become increasingly relevant. This essay delves into the intricate dynamics of [...]

Intercultural communication is a vital component of our increasingly interconnected world, enabling individuals to effectively navigate diverse cultural environments and interact with people from different backgrounds. In [...]

Interracial marriage, the union between individuals of different racial backgrounds, has long been a topic of societal discussion, reflection, and transformation. This essay delves into the complexities, challenges, and [...]

Dai, Y. (2015). How Does Oprah Winfrey Influence Society? . HASTAC. http://www.crf-usa.org/black-history-month/an-overview-of-the-african-american-experience

The term “Gung Ho” is an Americanized Chinese expression for “Work” and “Together”. Gung Ho is a 1986 comedy film which was directed by Ron Howard and starring Michael Keaton. The movie is a very good reflection of the real time [...]

I never moved schools, not even once. For the past 18 years, I have always lived in a densely packed town called Bandar Lampung – a city on the southern tip of Sumatra Island, Indonesia. I had always been surrounded by familiar [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

Language Learning: Why Is Intercultural Communication Important?

March 24, 2023

Thanks to fast transportation, global media, and the world wide web, we are now more connected than ever to other people worldwide.

Working with the international community for economic survival means countries and cultures can no longer operate in a vacuum. Because of this, intercultural communication is no longer a choice but a must .

In addition, misunderstandings resulting from a lack of familiarity with another culture are often embarrassing. Blunders like these can make it difficult, if not impossible, to reach an agreement with another country or close a business contract with a foreign partner. For travelers, a faux pas can also make interactions more awkward. In this article, we’ll be discussing the importance of intercultural communication.

CHECK OUR LANGUAGE PROGRAMS !

Intercultural Communication Definition

The capacity to communicate with people from diverse cultures is referred to as intercultural communication. Interacting effectively across cultural lines requires perseverance and sensitivity to one another’s differences. This encompasses language skills, customs, ways of thinking, social norms, and habits.

There are many ways in which people all around the world are similar, yet it is our differences that truly define us. To put it simply, communication is the exchange of ideas and information between individuals by any means, verbal or otherwise. Sharing knowledge with others requires familiarity with social norms, body language, and etiquette.

Having the ability to communicate effectively across cultural boundaries is critical for the success of any intercultural or multinational endeavor. Additionally, it helps improve relationships by facilitating two-way conversations, which in turn foster mutual understanding between people of diverse backgrounds.

Intercultural Communication Examples

There are several facets to intercultural communication competence, from language skills to knowledge of social practices and cultural norms. These capabilities are constantly used throughout organizations and in all forms of communication. Here are a few examples of intercultural communication in action:

It can be challenging for multinational corporations to find appropriate product names that will not offend customers in their target markets due to linguistic differences. For instance, Coca-Cola initially considered renaming its brand KeKou-KeLa for the Chinese market. However, they didn’t take into account that this cute moniker means “female horse stuffed with wax” or “bite the wax tadpole.” Unsurprisingly, a rebrand was necessary. Coke then looked up 40,000 Chinese characters to get a phonetic equivalent and came up with “ko-kou-ko-le,” which roughly translates to “happiness in the mouth.”

LEARN CHINESE !

Business Relationships

Respecting the social norms of another culture requires an understanding that practices may vary. While Americans value making small talk with potential business partners, the British may try humor, while the Germans may jump right to the point.

In contrast, people from Thailand don’t bat an eye when asked what may be seen as intrusive questions in the West, such as whether you’re married or what you do for a living. Similarly, Americans prefer first names, but in Austria, titles are used to prevent coming off as disrespectful.

Advertising