RACE Writing: A Comprehensive Guide + Examples

Welcome to the ultimate guide on mastering the RACE writing method.

Whether you’re a student aiming to ace your essays, a teacher looking to boost your students’ writing skills, or simply someone who wants to write more clearly and effectively, this guide is for you. Let’s transform your writing together,

What Is RACE Writing?

Table of Contents

RACE is an acronym that stands for Restate, Answer, Cite, and Explain .

This structured approach ensures that responses are clear, complete, and well-supported by evidence.

Here’s a quick overview of what each component entails:

- Restate : Begin by restating the question or prompt to establish the context of your response.

- Answer : Directly answer the question or address the prompt.

- Cite : Provide evidence or examples to support your answer.

- Explain : Elaborate on the evidence and its relevance to your answer.

Now, let’s dive deeper into each component of the RACE strategy and see how to apply it effectively.

Restate: Setting the Context

Restating the question or prompt is the first step in the RACE strategy. This ensures that the reader knows exactly what question you are addressing. It also helps you stay focused on the topic.

Tips for Restating

- Paraphrase the Question : Don’t just repeat the question verbatim. Rephrase it in your own words.

- Keep it Brief : Your restatement should be concise and to the point.

- Include Key Terms : Make sure to use key terms from the question to maintain clarity.

Question : How does the protagonist in “To Kill a Mockingbird” demonstrate courage? Restatement : The protagonist in “To Kill a Mockingbird” demonstrates courage through various actions and decisions.

Answer: Direct and Clear Responses

Once you’ve restated the question, the next step is to answer it directly. This is your main response to the question or prompt.

Tips for Answering

- Be Direct : Clearly state your answer without beating around the bush.

- S tay Focused: Make sure your answer directly tackles the question at hand.

- Keep it Simple : Use straightforward language to convey your point.

Answer : The protagonist, Scout Finch, demonstrates courage by standing up for what she believes is right, despite the risks involved.

Cite: Supporting with Evidence

Citing evidence is crucial for backing up your answer. This involves providing quotes, data, or examples that support your response.

Tips for Citing

- Use Reliable Sources : Ensure your evidence comes from credible and relevant sources.

- Integrate Smoothly : Blend your citations into your writing seamlessly.

- Be Specific : Provide detailed and specific evidence.

Citation : For instance, in the novel, Scout stands up to a mob intent on lynching Tom Robinson, demonstrating her bravery (Lee, 1960, p. 153).

Explain: Making the Connection

The final step is to explain how your evidence supports your answer. This is where you connect the dots and show the significance of your evidence.

Tips for Explaining

- Be Thorough : Provide a detailed explanation of how the evidence supports your answer.

- Clarify Relevance : Clearly show the link between your evidence and your response.

- Avoid Assumptions : Don’t assume the reader will understand the connection without your explanation.

Explanation : This act of defiance highlights Scout’s moral courage, as she is willing to face danger to uphold justice and protect the innocent.

Watch this playlist of videos on RACE Writing:

Using RACE Writing for Yourself

Implementing the RACE strategy in your writing can significantly enhance the quality and coherence of your work.

Here are some practical steps to integrate RACE into your writing process:

1. Understand the Prompt

Before you start writing, make sure you fully understand the question or prompt.

This will help you accurately restate it in your response.

Spend time analyzing the prompt to grasp its nuances and underlying questions. This thorough understanding allows you to pinpoint exactly what is being asked, ensuring that your response remains relevant and focused.

Misinterpreting the prompt can lead to an off-topic answer, wasting both your time and effort.

Additionally, breaking down the prompt into smaller, manageable parts can be beneficial.

Identify the key terms and phrases, and consider their implications.

By doing this, you can create a mental map of your response, making it easier to restate the prompt effectively in your own words.

This step sets a strong foundation for the rest of the RACE process.

2. Outline Your Response

Create a brief outline using the RACE components.

This will help you organize your thoughts and ensure that you address each part of the strategy.

Start with your restatement, then outline your direct answer, list the evidence you will cite, and plan your explanations.

An outline serves as a roadmap, guiding you through your writing process and helping you stay on track.

An organized outline not only saves time but also enhances the coherence of your response.

It allows you to see the overall structure and flow of your argument, making it easier to identify any gaps or weaknesses.

This proactive approach helps you craft a well-rounded and compelling response, ensuring that each RACE component is effectively addressed.

3. Draft and Revise

Write a draft of your response, focusing on incorporating each element of RACE.

Afterward, revise your work to refine your restatement, answer, citations, and explanations.

Drafting allows you to put your ideas into words without worrying too much about perfection.

It’s an opportunity to explore your thoughts and see how well they translate onto the page.

Revising, on the other hand, is where the real magic happens.

Take a critical look at your draft, checking for clarity, coherence, and consistency.

Ensure that your restatement is accurate, your answer is direct, your citations are relevant, and your explanations are thorough.

This iterative process of drafting and revising helps you produce a polished and effective piece of writing.

4. Practice Regularly

Like any skill, mastering RACE takes practice.

Regularly applying the strategy in various writing contexts will help you become more proficient.

The more you practice, the more intuitive the process will become, allowing you to apply the RACE strategy effortlessly.

Experiment with different types of writing prompts and questions.

This diversity in practice will help you adapt the RACE strategy to different contexts and topics, making you a more versatile writer.

Regular practice also builds confidence, enabling you to tackle any writing task with ease and assurance.

Teaching RACE Writing to Students

As an educator, teaching the RACE writing strategy to students can significantly improve their writing abilities.

Here are some tips for effectively teaching RACE:

1. Introduce the Strategy

Start by explaining the RACE acronym and its components.

Use examples to illustrate each part of the strategy. Providing a clear and thorough introduction helps students understand the purpose and benefits of the RACE strategy.

Use engaging examples that are relevant to their interests to capture their attention and make the concept more relatable.

In addition, consider using visual aids such as charts or diagrams to break down the RACE components.

Visual representations can make it easier for students to grasp the structure and flow of the strategy.

Reinforce your explanation with real-life examples from texts they are familiar with, demonstrating how RACE can be applied in various contexts.

2. Model the Process

Demonstrate how to apply the RACE strategy by working through an example together with your students.

Show them how to restate, answer, cite, and explain cohesively.

Modeling the process provides students with a concrete example of how to effectively use RACE in their writing.

It also allows them to see the strategy in action, making it more accessible and understandable.

During the modeling process, think aloud to explain your reasoning and decision-making.

This helps students understand the thought process behind each step of the RACE strategy.

Encourage questions and provide immediate feedback to clarify any doubts. By actively engaging students in the modeling process, you foster a deeper understanding and appreciation of the strategy.

3. Practice with Guidance

Provide students with practice prompts and guide them through the RACE process.

Offer feedback to help them improve their responses.

Guided practice allows students to apply the RACE strategy in a supportive environment, where they can receive constructive feedback and make necessary adjustments.

Start with simpler prompts and gradually increase the complexity as students become more comfortable with the strategy.

Pair students up for peer practice sessions, where they can collaborate and learn from each other.

As they practice, circulate around the classroom to provide individualized feedback and address any challenges they may face.

This hands-on approach helps reinforce the RACE strategy and builds students’ confidence in their writing abilities.

4. Encourage Peer Review

Have students review each other’s work using the RACE strategy.

This peer review process can provide valuable insights and help reinforce their understanding.

Peer review fosters a collaborative learning environment, where students can share their perspectives and learn from each other.

Provide clear guidelines and criteria for peer review to ensure that the feedback is constructive and focused.

Encourage students to use the RACE framework to evaluate their peers’ responses, highlighting strengths and suggesting areas for improvement.

This process not only helps students refine their writing but also enhances their critical thinking and analytical skills.

By engaging in peer review, students gain a deeper understanding of the RACE strategy and learn to appreciate different writing styles and approaches.

5. Assess Progress

Regularly assess students’ writing to ensure they are effectively applying the RACE strategy.

Provide constructive feedback to help them continue improving.

Regular assessments allow you to track students’ progress and pinpoint areas where they might need extra help or guidance.

Use a variety of assessment methods, such as quizzes, writing assignments, and in-class exercises, to evaluate students’ understanding and application of the RACE strategy.

Provide detailed feedback that highlights both strengths and areas for improvement.

Offer specific suggestions for how they can enhance their responses.

Celebrate their successes and acknowledge their efforts to motivate and encourage continuous improvement.

By consistently assessing progress, you can ensure that students are mastering the RACE strategy and developing strong writing skills.

Examples of RACE Writing in Action

To illustrate how the RACE strategy can be effectively applied, here are three comprehensive examples.

These examples cover different contexts, showcasing the versatility of the RACE strategy in enhancing writing clarity and coherence.

Example 1: Literature Analysis

Prompt : How does the theme of friendship manifest in “Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone”?

Restate : The theme of friendship is a central element in “Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone.”

Answer : Friendship is portrayed through the strong bond between Harry, Ron, and Hermione, which helps them overcome numerous challenges.

Cite : For instance, when Ron sacrifices himself in the life-sized chess game to allow Harry and Hermione to move forward (Rowling, 1997, p. 283).

Explain : This act of selflessness exemplifies the deep trust and loyalty among the trio, highlighting how their friendship empowers them to face dangers together. Ron’s willingness to risk his life underscores the strength of their bond, illustrating the theme of friendship as a vital force in their journey.

Example 2: Scientific Report

Prompt : Explain how photosynthesis contributes to the oxygen supply on Earth.

Restate : Photosynthesis plays a crucial role in maintaining the oxygen supply on Earth.

Answer : During photosynthesis, plants convert carbon dioxide and water into glucose and oxygen, releasing oxygen as a byproduct.

Cite : According to Smith (2020), “Plants release approximately 260 billion tons of oxygen into the atmosphere each year through the process of photosynthesis” (p. 45).

Explain : This process is fundamental to sustaining life on Earth, as it replenishes the oxygen that animals and humans breathe. Without photosynthesis, the oxygen levels in the atmosphere would diminish, leading to a decline in aerobic organisms. Therefore, photosynthesis is essential for maintaining the balance of gases in our atmosphere and supporting life.

Example 3: Historical Analysis

Prompt : Discuss the impact of the Industrial Revolution on urbanization in the 19th century.

Restate : The Industrial Revolution significantly influenced urbanization in the 19th century.

Answer : The rapid industrialization led to a massive migration of people from rural areas to cities in search of employment opportunities.

Cite : Historical records indicate that the urban population in England increased from 20% to 50% between 1800 and 1850 due to industrialization (Johnson, 2015, p. 102).

Explain : This shift transformed the social and economic fabric of society, as cities grew rapidly to accommodate the influx of workers. The development of factories and the need for labor created new urban centers, leading to improved infrastructure and changes in living conditions. However, this rapid urbanization also brought challenges, such as overcrowding and poor sanitation, highlighting the complex impact of the Industrial Revolution on society.

Final Thoughts: RACE Writing

Mastering the RACE writing strategy enhances clarity, coherence, and persuasiveness in writing.

By Restating, Answering, Citing, and Explaining, you can effectively address any prompt.

Embrace RACE to elevate your writing skills and produce compelling responses.

Related Posts

- Oreo Opinion Writing [Tips, Guide, & Examples]

- Writing Rubrics [Examples, Best Practices, & Free Templates]

- How to Write a Paragraph [Ultimate Guide + Examples]

- Narrative Writing Graphic Organizer [Guide + Free Templates]

- How to Write a Haiku [40 Tips & Examples]

- K-12 Outreach

- RACES Writing Strategy

The RACES writing strategy is an acronym that stands for the following components:

This refers to restating or rephrasing the question or prompt in your own words to ensure that you understand it correctly.

Provide a clear and concise answer to the question or prompt. This is the main part of your response and should directly address what is being asked.

Support your answer with evidence or examples. This could involve referencing specific facts, data, quotations, or other sources of information that support your response. Citing your sources helps to strengthen your argument and provide credibility to your writing.

Elaborate on your answer and provide further clarification or reasoning. Explain how your evidence or examples support your answer and demonstrate your understanding of the topic.

Summarize your response by restating your main points and bringing your writing to a conclusion. This helps to reinforce your main argument and leave a lasting impression on the reader.

Google Doc of the student graphic

The strategy provides a simple and structured framework for students to follow when responding to questions or prompts. It helps them develop their writing skills by encouraging them to restate the question, provide a clear answer, support their answer with evidence, explain their reasoning, and summarize their response.

By introducing the RACES strategy to students, teachers can help them organize their thoughts, express their ideas more effectively, and develop critical thinking skills. The strategy can be applied to various types of writing tasks, including short responses, paragraph writing, or longer compositions.

However, it's important to adapt the strategy to the age and abilities of the students. For younger elementary students, the concept of citing sources may be simplified to using examples from the text or personal experiences. Teachers can provide guidance and support as students learn to apply the different components of the RACES strategy in their writing.

Purdue University College of Science, 150 N. University St, West Lafayette, IN 47907 • Phone: (765) 494-1729, Fax: (765) 494-1736

Student Advising Office: (765) 494-1771, Fax: (765) 496-3015 • Science IT , (765) 494-4488

© 2023 Purdue University | An equal access/equal opportunity university | Copyright Complaints

Trouble with this page? Disability-related accessibility issue ? Please contact the College of Science Webmaster .

MAKE WAVES WITH THIS FREE WEEKLONG VOCABULARY UNIT!

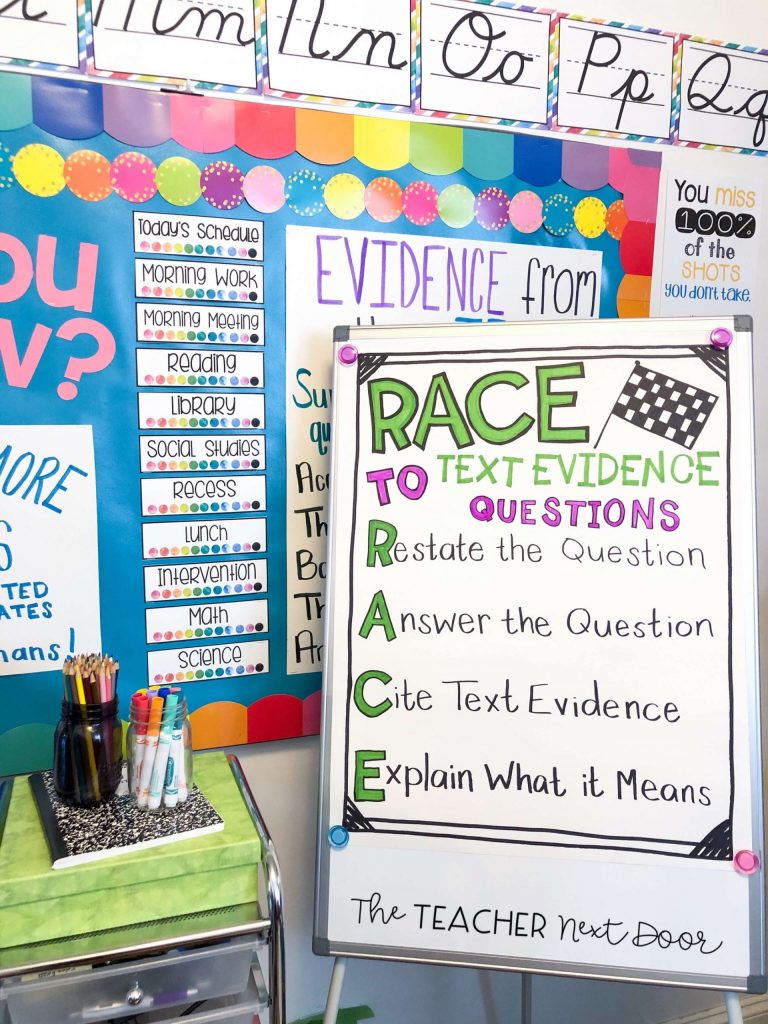

Using the RACE Strategy for Text Evidence

How to Teach Constructed Response Using the RACE Strategy

Constructed response questions can be scary at first. Scary to teach and scary to write! Using the RACE Strategy will help ensure students get this skill right, every time!

I mean, when you compare writing a constructed response to answering a multiple-choice question, well, there really is no contest.

Constructed Response makes multiple-choice questions seem so simple to complete.

Since we know that students need to be able to write constructed responses, I was so happy when I was introduced to the RACE strategy.

It took the fright out of teaching constructed responses for text evidence.

The RACE Strategy gave me a step-by-step template to teach my students precisely what to do.

Even though writing constructed responses are still challenging, when you teach your students the RACE strategy and give them lots of opportunities for practice, your students will master it!

What is the RACE Strategy? So, just what is the RACE strategy? RACE is an acronym that helps students remember which steps and in which order to write a constructed response.

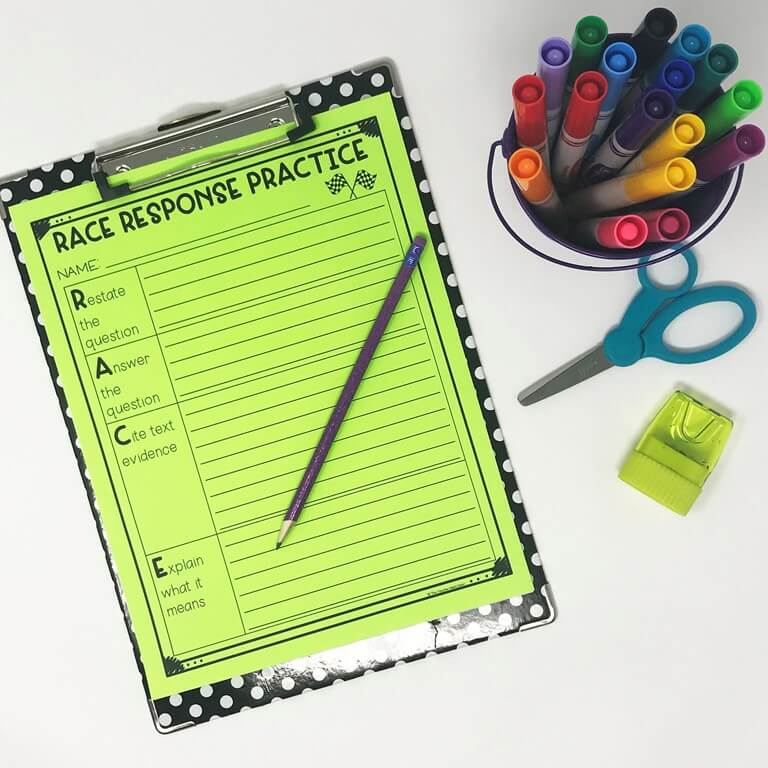

R = Restate the Question

The first step is to change the question into a statement.

This is also known as restating the question.

Students need to remove the question word like who, what, when, where, or why and then restate the keywords.

For example, if the question was, “Why did Jill decide to give her mother a jewelry box?” the answer would start this way, “Jill decided to give her mother a jewelry box because.”

A = Answer the Question After restating the question, the second step is to finish the sentence and answer the question.

Students may use their knowledge and inferences from the text to identify the answer.

Here are a few tips for this.

1) Students must answer the specific question being asked.

2) Students also need to answer every part of the question. Sometimes questions have more than one part. 3) T hey need to list the character’s name before using a pronoun like he/she/they.

C = Cite Text Evidence Citing evidence is the tricky part.

First, kids need to find relevant evidence to support their answer.

Then, they must write it correctly using a sentence stem

According to the text…

- The author stated…

- In the second paragraph…

- The author mentioned…

- On the third page…

- The text stated…

- Based on the text…

To teach this skill, I make an anchor chart with the question stems and put them up when we start to work on citing evidence.

Once kids memorize a few question stems, this part of the RACE strategy goes much more smoothly.

I make sure students know to quote the text exactly as it is written and use quotation marks correctly too.

E = Explain What it Means

The last part of the Constructed Response is where kids tell how their text evidence proves their point.

Again, some simple sentence starters help kids stay on track here.

Here are a few examples of sentence starters that help students begin to Explain:

- This proves

- This is a good example of

- This means that

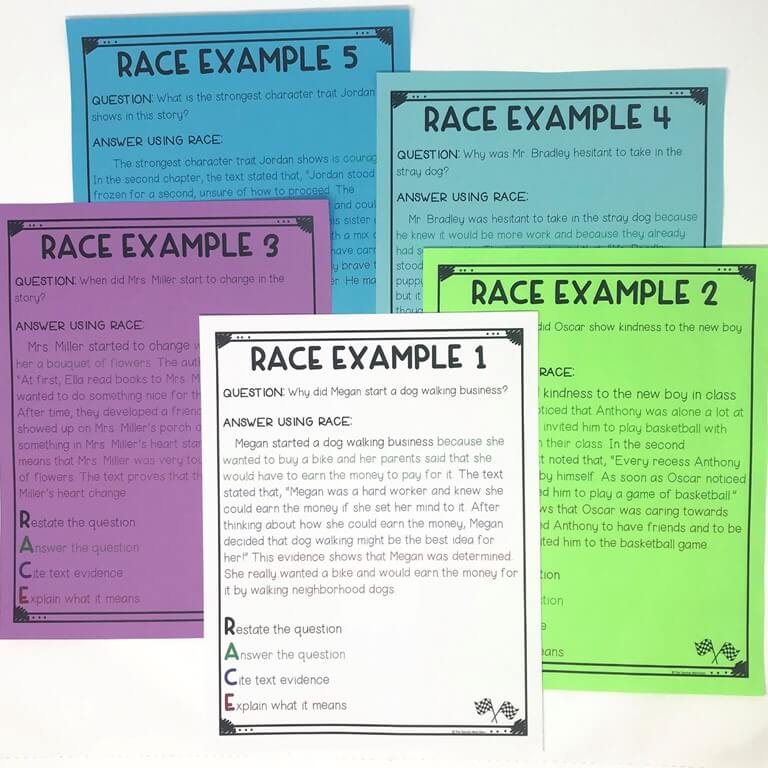

When I teach the RACE strategy, I give the kids an overview of a completed constructed response example, so they can see where we’re going.

Then, I break it down into separate parts and teach each one before putting it all together.

By the time kids reach my fourth or fifth-grade class, most students at my school have had teachers who have required them to answer a question using a restatement.

Students aren’t doing constructed responses yet, but most are fairly comfortable with restating a question.

Because of this, I might spend a few days teaching or reviewing the restating and answering part.

I teach the Restating and Answering together since they usually form one sentence.

Then, I move to Citing text evidence, which takes much longer to teach.

The Explaining part goes pretty quickly after that.

Once I’ve taught all of the components, it’s time for students to practice putting it all together.

To do this, we read a short text as a class.

It might be a Scholastic News article, a page from Chicken Soup for the Soul, or a passage I’ve created.

Finally, I model (with their input) a Constructed Response using a RACE template from The Teacher Next Door’s Text Evidence Differentiated Unit

I project it on the smartboard so everyone can see it.

The next day, we repeat this with a different passage in pairs.

When students are finished, we go over it together to compare notes when they’re finished. After that, it is time to work on it independently.

A few notes…

- Make sure to start teaching the RACE strategy early in the year, so there’s plenty of time to practice. If you teach this strategy right before standardized testing, it will not be very effective.

- Start with short passages. One page is ideal. Giving students practice with shorter texts will help them gain confidence for the longer texts in the future. Baby steps, right?

- You’ll want students to write constructed responses repeatedly, but NOT for every passage they read.

- Constructed responses are somewhat of a chore, even with an excellent strategy like RACE.

- I try not to burn kids out on any one thing so that they dread it. It would be like asking them to write a five-paragraph essay each day. No one wants to do that. So, my advice is to give them a good foundation for how to write them and then sprinkle them in now and then throughout the year. Spiral practice is key!

You can apply the RACE Strategy to any set of materials that you have on hand. However, The Teacher Next Door knows how time consuming it can be to search for standards-aligned and grade level appropriate materials.

To save you time, The Teacher Next Door has created a Text Evidence Differentiated Unit with everything you need for students to master this skill!

The Text Evidence Differentiated Unit contains:

- 10 color coding passages

- 8 practice passages

- 3 sets of text evidence games (with 32 task cards in each set)

- Posters for the entire RACE Strategy

The entire unit is differentiated for you! Each passage comes in three different levels, and the three games are differentiated too!

Click here to check this unit out!

Want to give this Text Evidence Differentiated Passage a spin for FREE?

If you’d like to read more about how to teach text evidence, we have another post you may want to read :

Citing Text Evidence in 6 Steps.

- Read more about: Reading

You might also like...

A Weekly Vocabulary Lesson Plan to BOOST Skilled Reading and Comprehension

A Weekly Vocabulary Lesson Plan to BOOST Skilled Reading and Comprehension Here’s what you can expect to learn from this article: The current state of

How to Make the Most of Reading Assessments

Does your school or district require you to do reading assessments a certain number of times per year? I’ve heard of teachers who are required

What are Strategy Groups in Reading and How Best to Use Them

In the world of teaching reading, there are certain staples that have been around forever, that teachers pretty universally agree are valuable and worthwhile. Guided

Hi, I’m Jenn, CEO and owner of The Teacher Next Door!

I know that you strive to be an effective upper elementary teacher while maintaining a healthy work-life balance.

In order to do that, you need resources that are impactful, yet simple .

The problem is that most resources and curriculums out there are far from simple. The pages upon pages of daily lesson plans are just plain overwhelming .

At TTND, we believe teachers should be living their lives outside of the classroom, and not spend hours lesson planning and searching for resources.

We understand that now, more than ever, teachers need space to be themselves which is why we create and support teachers with timesaving tips and standards-aligned resources.

Want access to TTND's Free Resource Library? Sign up for our newsletter and we'll email you the exclusive password!

Trending posts.

SEARCH BY TOPIC

- Classroom Ideas

- Holidays and Seasonal

- Mentor Texts

- Reading Block

- Uncategorized

- Writing & Grammar

POPULAR RESOURCES

Facebook Group

Teachers Pay Teachers

Free Resource Library

💌 Contact Us

Disclosures

Privacy Policy

Refund Policy

Purchase Orders

Your Downloads

Reward Points

© The Teacher Next Door, LLC. All rights reserved.

* Please note: If your school has strong email filters, you may wish to use your personal email to ensure access.

Writing About Race, Ethnicity, Socioeconomic Status, and Disability

View in pdf format.

As language evolves alongside our understanding of race, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and disability, it is important for writers to make informed choices about their language and to take responsibility for those choices. Accurate language is important in writing about people respectfully and in crafting effective arguments your audience can trust. This handout includes writing practices and language tips to help you discuss various groups of people respectfully and without perpetuating stereotypes.

Best Practices

- Use people-first language. Use terms that focus on people rather than on the method of categorization to ensure your language is not dehumanizing. For example, use “people with mental illness” rather than “the mentally ill,” “people with disabilities” rather than “disabled people,” and “enslaved peoples” rather than “slaves.”

- Don’t use adjectives as nouns. Using adjectives as nouns is not only grammatically incorrect, it is often demeaning to the people you are describing. For example, use “Black people,” not “Blacks.”

- Avoid terms that imply inferiority or superiority. Replace terms that evaluate or might imply inferiority/superiority with non-judgmental language. For example, use “low socioeconomic status” rather than “low class,” or “historically marginalized population” rather than “minority.”

- Be specific. When these descriptors are relevant, be as specific as possible to avoid inaccurate or generalized statements. For example, use “Dominicans” rather than “Hispanics,” or “people who use wheelchairs” rather than “people with disabilities.”

Writing About Race and Ethnicity

When writing about race and ethnicity, use the following tips to guide you:

- Capitalize racial/ethnic groups, such as Black, Asian, and Native American. Depending on the context, white may or may not be capitalized.

- African Americans migrated to northern cities. (noun)

- African-American literature. (adjective)

- The terms Latino/Latina/Latin are used mostly in the US to refer to US residents with ties to Latin America .

Umbrella Terms

- Avoid the term “minority” if possible. “Minority” is often used to describe groups of people who are not part of the majority. This term is being phased out because it may imply inferiority and because minorities often are not in the numerical minority. An alternative might be “historically marginalized populations.” If it is not possible to avoid using “minority,” qualify the term with the appropriate specific descriptor: “religious minority” rather than “minority.”

- Note that the terms “people of color” and “non-white” are acceptable in some fields and contexts but not in others. Check with your professor if you’re uncertain whether a term is acceptable.

Writing About Socioeconomic Status

When writing about socioeconomic status, use the following tips to guide you:

- “Avoid using terms like “high class” or “low class,” or even “upper class” or “lower class,” because they have been used historically in an evaluative way. Also avoid “low brow” and “high brow.” Instead, if you must incorporate adjectives like “high” or “low,” use the term “high” or “low socioeconomic status” to avoid judgmental language.

- The word “status” (without the qualifier of “socioeconomic”) is not interchangeable with “class” because “status” can refer to other measures such as popularity.

- When possible, use specific metrics: common ones include level of educational attainment, occupation, and income.Use specific language that describes what is important to the analysis.

- Be aware of numbers: there are no distinct indicators of “high” and “low,” but there are percentages that make it easy to determine, via income bracket for example, where on a range an individual falls.

General Guidelines

When writing about disability, use the following tips to guide you:

- uses a wheelchair rather than confined to a wheelchair

- diagnosed with bipolar disorder rather than suffers from bipolar disorder

- person with a physical disability rather than physically challenged

- Do not use victimizing language such as afflicted, restricted, stricken, suffering, and unfortunate.

- Do not call someone ‘brave’ or ‘heroic’ simply for living with a disability.

- Avoid the term “handicapped,” as some find it insensitive. Note that it is widely used as a legal term in documents, on signs, etc.

- Do not use disabilities as nouns to refer to people. For example, use “people with mental illnesses” not “the mentally ill.”

- Avoid using the language of disability as metaphor, which stigmatizes people with disabilities, such as lame (lame idea), blind (blind luck), paralyzed (paralyzed with indecision), deaf (deaf ears), crazy, insane, moron, crippling, disabling, and the like.

- Capitalize a group name when stressing the fact that they are a cultural community (e.g. Deaf culture); do not capitalize when referring only to the disability.

Referring to people without disabilities

Use “people without disabilities,” or “neurotypical individuals” for mental disabilities. The term “able-bodied” may be appropriate in some disciplines. Do not use terms like “normal” or “healthy” to describe people without disabilities.

Writing with Outdated/Problematic Sources

When analyzing or referencing a source that uses harmful language (slurs, violent rhetoric, etc.), either:

- Explain that the author or character uses harmful language without stating it verbatim. For example: “The author uses an ableist slur when discussing [context of the quote], indicating that [analysis].”

- Acknowledge its offensive nature in your analysis if you must quote the harmful language verbatim.

Do not change the quote or omit harmful language without acknowledging it. If you must use outdated and problematic sources, it is best to acknowledge any harmful language or rhetoric and discuss how it impacts the use and meaning of the text in your analysis.

Note that if you do need to use dated terminology in discussing the subjects in a historical context, continue to use contemporary language in your own discussion and analysis.

If you are still unsure of what language to use after reading this, consult your professor, classmates, writing center tutors, or current academic readings in the discipline for more guidance.

As we have noted, language is complex and constantly evolving. We will update this resource to reflect changes in language use and guidelines. We also welcome suggestions for revisions to this handout. Please contact the Writing Center with any questions or suggestions.

Thank you to the following people who contributed to earlier versions of this resource: Emma Bowman ’15, Krista Hesdorfer ’14, Jessica LeBow ’15, Rohini Tashima ’15, Sharon Williams, Amit Taneja, Phyllis Breland, and Professors Jessica Burke, Dan Chambliss, Christine Fernández, Todd Franklin, Cara Jones, Esther Kanipe, Elizabeth Lee, Celeste Day Moore, Andrea Murray, Kyoko Omori, Ann Owen, and Steven Wu.

Adapted from prior Writing Center resource “Writing about Race, Ethnicity, Social Class, and Disability.”

Tutor Appointments

Peer tutor and consultant appointments are managed through TracCloud (login required). Find resources and more information about the ALEX centers using the following links.

Office / Department Name

Nesbitt-Johnston Writing Center

Contact Name

Jennifer Ambrose

Writing Center Director

Help us provide an accessible education, offer innovative resources and programs, and foster intellectual exploration.

Site Search

WELCOME! Find what you need

Elementary Math

Elementary Ela-Reading

Teaching Tips

Career Exploration

How to teach the race writing strategy.

Teachers and students rely on the RACE or RACES writing strategies to construct high-quality answers using text evidence.

WHAT IS THE RACE – RACES WRITING RESPONSE STRATEGY?

Students and teachers rely on the RACE – RACES written response strategy for a good reason. It’s a simple method for teaching students how to answer text-based questions.

RACE – RACES helps students remember the key components of a quality response as they answer questions about a passage, story, or text.

Many students aren’t sure how to begin when faced with writing out answers about what they’ve read. This easy-to-use method gives students confidence. Moreover, it’s a concrete strategy they can use in all subject areas.

WHY SHOULD TEACHERS USE RACE/RACES?

Students struggle to write complete answers to text-based questions on tests, quizzes, assignments, and high-stakes tests. RACE/RACES is a step-by-step formula that can be used across all subject areas, leading to increased confidence.

All students benefit from explicit writing instruction. However, reluctant writers require direct instruction on what to write and how to write it. In addition, they should practice regularly to improve their skills.

The RACE/RACES strategy helps students organize their thinking and writing. Students add details, such as citing text evidence and extending their answers, as they follow the steps of the acronym. As a result, students learn essential skills as they practice writing clear and complete responses.

What do the letters in RACE – RACES mean?

First, you need to choose either RACE or RACES for your instruction. RACE/RACES are acronyms that stand for the following writing strategies:

R – Restate the question

A – Answer the question

C – Cite the text evidence

E – Explain and extend the evidence

S – Summarize your answer

*Some teachers prefer ACE or ACES. Choose the method that best suits your students and your curriculum.

The R in RACE/RACES means “Restate the question.”

Restating the question becomes the topic sentence for the student’s answer. Each letter of RACE/RACES doesn’t have to be a complete sentence on its own. The R is often combined with the A in the same sentence. Remember – writing is individualized, and there’s more than one way of doing it.

The A stands for “Answer the question.”

Students provide the answer to the question in their own words. Unfortunately, many students resist taking the time to refer back to the text. I stress to my students that they need to look back in the reading to find the answer, even if they think they already know it.

Additionally, students need to make sure they answer all parts of the question . Unfortunately, students often answer only part of the question, causing them to lose points.

The C stands for “Cite the text evidence.”

First, students must understand what “cite” means. I often link “cite” to the word “sight” and connect it to looking back at the reading and seeing the answer with their eyes. Building that connection may help some students remember the meaning, especially if “cite” is a new word for them.

I also tell my students this step is where they need to use words and ideas straight from the text. In a follow-up lesson, older students should quote the text using quotation marks, which teachers should directly teach. Younger students can tell what the text says without directly quoting the text.

All students benefit from practicing with sentence starters (also called sentence stems). Sentence starters are the beginnings of sentences that allow students to fill in the blanks with the text evidence. Students (especially struggling students) find them very helpful for this step of the writing process.

Some examples are:

“The text states ___”

“The author explains ___”

There are many good sentence starter choices for students. They should use the ones they’re most comfortable with, and that come most naturally. (If you’re looking for a set you can display in your classroom, see the section at the end for links to matching sentence starter sets!)

The E stands for “Explain and extend the evidence.”

Lots of e’s! This step directs students to expand on their answers. They should explain the answer and text evidence using their own words. They should also provide examples to clarify their explanations.

The S (if you choose to use it) stands for “Summarize your answer.”

Like a summary/closing sentence in paragraph writing, this works as a restatement of the topic sentence. It concludes the response.

How do I teach the RACE/RACES method?

As with any instruction, there are many right ways of teaching a topic. You know your students best, so you can choose and adjust your teaching to their needs. Below are some general guidelines to keep in mind.

1. Choose the right text for the RACE/RACES strategy

Of course, choosing the right text depends entirely on your students. Students can apply the RACE/RACES strategy to any text, so you have many options. But I can offer you the following tips for successful instruction.

Begin with a simple reading comprehension paragraph. It must be simple enough for students to understand yet meaty enough to contain details. We want to keep the focus on answering the question rather than understanding the text. For this purpose, I’ve found it best to begin with a basic passage on an exciting topic .

Eventually, as students practice and improve their skills, you can challenge them with more complex text.

2. Differentiate for students and their needs

Differentiating is pretty easy and straightforward when using RACE/RACES.

During the introduction phase or for struggling students and special education students, choose passages that are familiar in some way to your students. For example, you might select a previously studied topic or a text that students have already read.

3. Use different types of reading materials

We know the importance of exposing our students to a wide variety of reading materials. RACE/RACES can be used for all types of reading. So, as students become accustomed to the RACE/RACES strategy, y ou can choose any genre or style of reading material and feel confident it will work well.

You may also differentiate by choosing several passages of varying levels for different ability levels in your classroom.

When it’s time to add variety and challenge to the texts, here are some suggestions:

- Vary the text length

- Vary the genre – fiction, nonfiction, persuasion, expository, etc.

- Vary the complexity

- Vary the question types

- Use paired passages

4. Teach important words and terms

- Explain the important terms and methods as you “think aloud.”

- Use the terms frequently each day as you teach. Students learn new words and vocabulary best when they hear it often in a natural way.

5. Use color-coding to highlight

As you’re working through the steps of RACE – RACES, highlight and underline text as you color-code each step using different colors. Then, continue the modeling and think-aloud for as long as students need.

6. Offer visuals for easy reference

Hang visual references in your classroom and encourage students to refer to them. Posters make great visual representations hanging in the classroom. Anchor charts can be developed as a class or in small groups.

Students can use the RACE/RACES bookmarks as references taped to notebooks or desks. Students may benefit from receiving multiple copies of the bookmark references to be kept in notebooks at school and at home.

7. Think about pacing and reviewing

You can teach one step per day, two steps, or more. The pace depends on the age and ability level of your students.

The RACE/RACES strategy must be modeled and practiced many times. The practice should occur as a group, together at first, and then students can be gradually released to independence.

A Quick RACE – RACES Recap:

- Explain important terms and steps as you “think aloud.”

- Model the steps as the class watches.

- Begin encouraging students to contribute their own ideas. Students can read passages and develop answers to text-based questions as a large group, small group, and with partners.

- Transition students to independence after ensuring they understand what’s expected of them.

- Use important terms daily as you teach. Students will gain a deeper understanding as they hear important words used naturally and frequently.

Over time, keep students’ writing skills sharp by continuing to spiral back to practice the RACE – RACES writing technique.

The continued practice may not make students’ writing perfect, but it can help make their skills permanent and keep it fresh in their minds.

Looking for SENTENCE STARTERS?

If you need some Sentence Starters ready to be printed and hung in your classroom, check out the Sentence Starters sets at my Teachers Pay Teachers store. There are two different styles for you to look over.

These sentence starters are also known as writing stems , sentence stems , and constructed response starters .

Want to learn more about citing text evidence?

Your students can successfully cite text evidence when responding to reading comprehension questions.

Step-by-step on how to teach your students to cite text evidence in their reading.

How to Teach Compare and Contrast Essays .

Help students write high-quality responses and prepare for tests with Sentence Starters.

If you use a PLOT DIAGRAM, this article shows you How to Use the Plot Diagram for Teaching.

Hi, I’m Jules

Find it fast, browse the blog, visit my teachers pay teachers shop.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

10.2 The Meaning of Race and Ethnicity

Learning objectives.

- Critique the biological concept of race.

- Discuss why race is a social construction.

- Discuss the advantages and disadvantages of a sense of ethnic identity.

To understand this problem further, we need to take a critical look at the very meaning of race and ethnicity in today’s society. These concepts may seem easy to define initially but are much more complex than their definitions suggest.

Let’s start first with race , which refers to a category of people who share certain inherited physical characteristics, such as skin color, facial features, and stature. A key question about race is whether it is more of a biological category or a social category. Most people think of race in biological terms, and for more than 300 years, or ever since white Europeans began colonizing populations of color elsewhere in the world, race has indeed served as the “premier source of human identity” (Smedley, 1998, p. 690).

It is certainly easy to see that people in the United States and around the world differ physically in some obvious ways. The most noticeable difference is skin tone: some groups of people have very dark skin, while others have very light skin. Other differences also exist. Some people have very curly hair, while others have very straight hair. Some have thin lips, while others have thick lips. Some groups of people tend to be relatively tall, while others tend to be relatively short. Using such physical differences as their criteria, scientists at one point identified as many as nine races: African, American Indian or Native American, Asian, Australian Aborigine, European (more commonly called “white”), Indian, Melanesian, Micronesian, and Polynesian (Smedley, 1998).

Although people certainly do differ in the many physical features that led to the development of such racial categories, anthropologists, sociologists, and many biologists question the value of these categories and thus the value of the biological concept of race (Smedley, 2007). For one thing, we often see more physical differences within a race than between races. For example, some people we call “white” (or European), such as those with Scandinavian backgrounds, have very light skins, while others, such as those from some Eastern European backgrounds, have much darker skins. In fact, some “whites” have darker skin than some “blacks,” or African Americans. Some whites have very straight hair, while others have very curly hair; some have blonde hair and blue eyes, while others have dark hair and brown eyes. Because of interracial reproduction going back to the days of slavery, African Americans also differ in the darkness of their skin and in other physical characteristics. In fact it is estimated that about 80% of African Americans have some white (i.e., European) ancestry; 50% of Mexican Americans have European or Native American ancestry; and 20% of whites have African or Native American ancestry. If clear racial differences ever existed hundreds or thousands of years ago (and many scientists doubt such differences ever existed), in today’s world these differences have become increasingly blurred.

Another reason to question the biological concept of race is that an individual or a group of individuals is often assigned to a race on arbitrary or even illogical grounds. A century ago, for example, Irish, Italians, and Eastern European Jews who left their homelands for a better life in the United States were not regarded as white once they reached the United States but rather as a different, inferior (if unnamed) race (Painter, 2010). The belief in their inferiority helped justify the harsh treatment they suffered in their new country. Today, of course, we call people from all three backgrounds white or European.

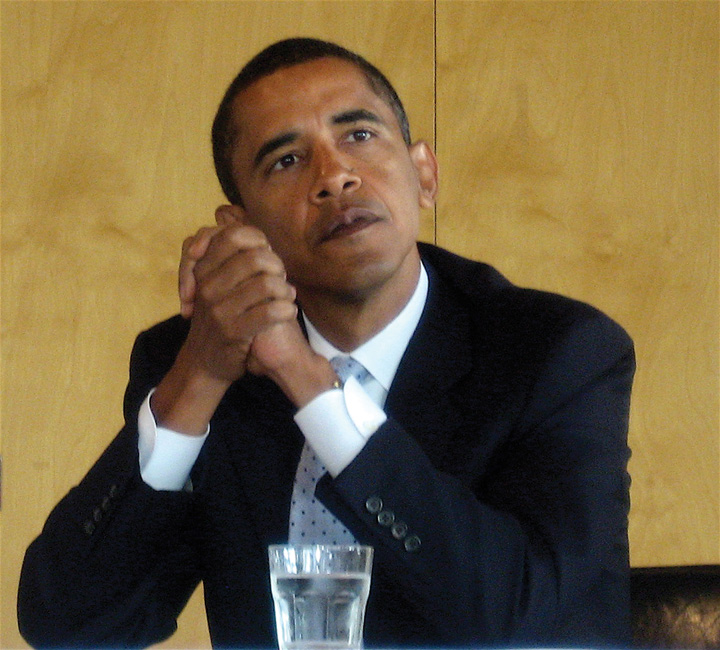

In this context, consider someone in the United States who has a white parent and a black parent. What race is this person? American society usually calls this person black or African American, and the person may adopt the same identity (as does Barack Obama, who had a white mother and African father). But where is the logic for doing so? This person, as well as President Obama, is as much white as black in terms of parental ancestry. Or consider someone with one white parent and another parent who is the child of one black parent and one white parent. This person thus has three white grandparents and one black grandparent. Even though this person’s ancestry is thus 75% white and 25% black, she or he is likely to be considered black in the United States and may well adopt this racial identity. This practice reflects the traditional “one-drop rule” in the United States that defines someone as black if she or he has at least one drop of “black blood,” and that was used in the antebellum South to keep the slave population as large as possible (Wright, 1993). Yet in many Latin American nations, this person would be considered white. In Brazil, the term black is reserved for someone with no European (white) ancestry at all. If we followed this practice in the United States, about 80% of the people we call “black” would now be called “white.” With such arbitrary designations, race is more of a social category than a biological one.

President Barack Obama had an African father and a white mother. Although his ancestry is equally black and white, Obama considers himself an African American, as do most Americans. In several Latin American nations, however, Obama would be considered white because of his white ancestry.

Steve Jurvetson – Barack Obama on the Primary – CC BY 2.0.

A third reason to question the biological concept of race comes from the field of biology itself and more specifically from the studies of genetics and human evolution. Starting with genetics, people from different races are more than 99.9% the same in their DNA (Begley, 2008). To turn that around, less than 0.1% of all the DNA in our bodies accounts for the physical differences among people that we associate with racial differences. In terms of DNA, then, people with different racial backgrounds are much, much more similar than dissimilar.

Even if we acknowledge that people differ in the physical characteristics we associate with race, modern evolutionary evidence reminds us that we are all, really, of one human race. According to evolutionary theory, the human race began thousands and thousands of years ago in sub-Saharan Africa. As people migrated around the world over the millennia, natural selection took over. It favored dark skin for people living in hot, sunny climates (i.e., near the equator), because the heavy amounts of melanin that produce dark skin protect against severe sunburn, cancer, and other problems. By the same token, natural selection favored light skin for people who migrated farther from the equator to cooler, less sunny climates, because dark skins there would have interfered with the production of vitamin D (Stone & Lurquin, 2007). Evolutionary evidence thus reinforces the common humanity of people who differ in the rather superficial ways associated with their appearances: we are one human species composed of people who happen to look different.

Race as a Social Construction

The reasons for doubting the biological basis for racial categories suggest that race is more of a social category than a biological one. Another way to say this is that race is a social construction , a concept that has no objective reality but rather is what people decide it is (Berger & Luckmann, 1963). In this view race has no real existence other than what and how people think of it.

This understanding of race is reflected in the problems, outlined earlier, in placing people with multiracial backgrounds into any one racial category. We have already mentioned the example of President Obama. As another example, the famous (and now notorious) golfer Tiger Woods was typically called an African American by the news media when he burst onto the golfing scene in the late 1990s, but in fact his ancestry is one-half Asian (divided evenly between Chinese and Thai), one-quarter white, one-eighth Native American, and only one-eighth African American (Leland & Beals, 1997).

Historical examples of attempts to place people in racial categories further underscore the social constructionism of race. In the South during the time of slavery, the skin tone of slaves lightened over the years as babies were born from the union, often in the form of rape, of slave owners and other whites with slaves. As it became difficult to tell who was “black” and who was not, many court battles over people’s racial identity occurred. People who were accused of having black ancestry would go to court to prove they were white in order to avoid enslavement or other problems (Staples, 1998). Litigation over race continued long past the days of slavery. In a relatively recent example, Susie Guillory Phipps sued the Louisiana Bureau of Vital Records in the early 1980s to change her official race to white. Phipps was descended from a slave owner and a slave and thereafter had only white ancestors. Despite this fact, she was called “black” on her birth certificate because of a state law, echoing the “one-drop rule,” that designated people as black if their ancestry was at least 1/32 black (meaning one of their great-great-great grandparents was black). Phipps had always thought of herself as white and was surprised after seeing a copy of her birth certificate to discover she was officially black because she had one black ancestor about 150 years earlier. She lost her case, and the U.S. Supreme Court later refused to review it (Omi & Winant, 1994).

Although race is a social construction, it is also true, as noted in an earlier chapter, that things perceived as real are real in their consequences. Because people do perceive race as something real, it has real consequences. Even though so little of DNA accounts for the physical differences we associate with racial differences, that low amount leads us not only to classify people into different races but to treat them differently—and, more to the point, unequally—based on their classification. Yet modern evidence shows there is little, if any, scientific basis for the racial classification that is the source of so much inequality.

Because of the problems in the meaning of race , many social scientists prefer the term ethnicity in speaking of people of color and others with distinctive cultural heritages. In this context, ethnicity refers to the shared social, cultural, and historical experiences, stemming from common national or regional backgrounds, that make subgroups of a population different from one another. Similarly, an ethnic group is a subgroup of a population with a set of shared social, cultural, and historical experiences; with relatively distinctive beliefs, values, and behaviors; and with some sense of identity of belonging to the subgroup. So conceived, the terms ethnicity and ethnic group avoid the biological connotations of the terms race and racial group and the biological differences these terms imply. At the same time, the importance we attach to ethnicity illustrates that it, too, is in many ways a social construction, and our ethnic membership thus has important consequences for how we are treated.

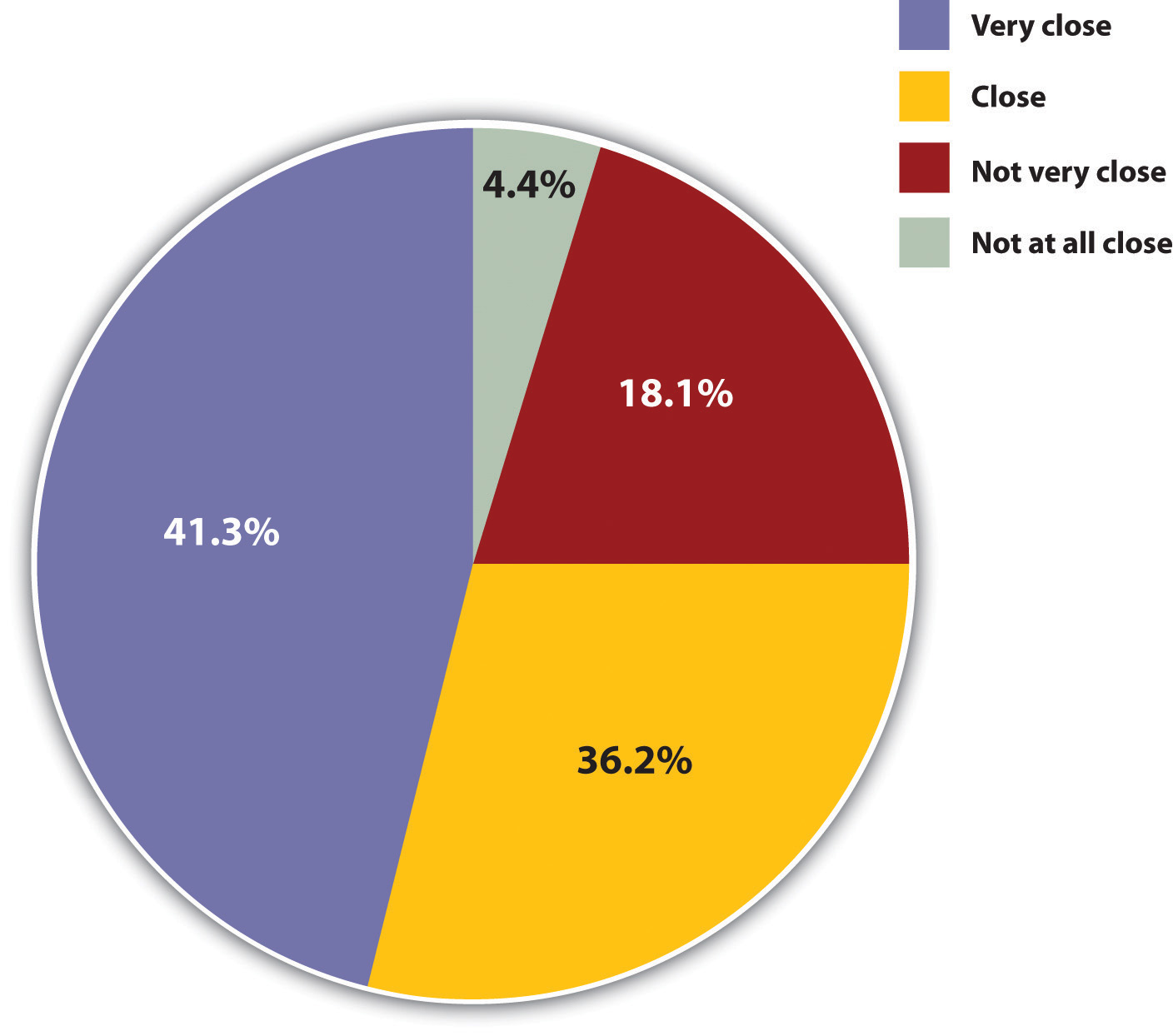

The sense of identity many people gain from belonging to an ethnic group is important for reasons both good and bad. Because, as we learned in Chapter 6 “Groups and Organizations” , one of the most important functions of groups is the identity they give us, ethnic identities can give individuals a sense of belonging and a recognition of the importance of their cultural backgrounds. This sense of belonging is illustrated in Figure 10.1 “Responses to “How Close Do You Feel to Your Ethnic or Racial Group?”” , which depicts the answers of General Social Survey respondents to the question, “How close do you feel to your ethnic or racial group?” More than three-fourths said they feel close or very close. The term ethnic pride captures the sense of self-worth that many people derive from their ethnic backgrounds. More generally, if group membership is important for many ways in which members of the group are socialized, ethnicity certainly plays an important role in the socialization of millions of people in the United States and elsewhere in the world today.

Figure 10.1 Responses to “How Close Do You Feel to Your Ethnic or Racial Group?”

Source: Data from General Social Survey, 2004.

A downside of ethnicity and ethnic group membership is the conflict they create among people of different ethnic groups. History and current practice indicate that it is easy to become prejudiced against people with different ethnicities from our own. Much of the rest of this chapter looks at the prejudice and discrimination operating today in the United States against people whose ethnicity is not white and European. Around the world today, ethnic conflict continues to rear its ugly head. The 1990s and 2000s were filled with “ethnic cleansing” and pitched battles among ethnic groups in Eastern Europe, Africa, and elsewhere. Our ethnic heritages shape us in many ways and fill many of us with pride, but they also are the source of much conflict, prejudice, and even hatred, as the hate crime story that began this chapter so sadly reminds us.

Key Takeaways

- Sociologists think race is best considered a social construction rather than a biological category.

- “Ethnicity” and “ethnic” avoid the biological connotations of “race” and “racial.”

For Your Review

- List everyone you might know whose ancestry is biracial or multiracial. What do these individuals consider themselves to be?

- List two or three examples that indicate race is a social construction rather than a biological category.

Begley, S. (2008, February 29). Race and DNA. Newsweek . Retrieved from http://www.newsweek.com/blogs/lab-notes/2008/02/29/race-and-dna.html .

Berger, P., & Luckmann, T. (1963). The social construction of reality . New York, NY: Doubleday.

Leland, J., & Beals, G. (1997, May 5). In living colors: Tiger Woods is the exception that rules. Newsweek 58–60.

Omi, M., & Winant, H. (1994). Racial formation in the United States: From the 1960s to the 1990s (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Routledge.

Painter, N. I. (2010). The history of white people . New York, NY: W. W. Norton.

Smedley, A. (1998). “Race” and the construction of human identity. American Anthropologist, 100 , 690–702.

Staples, B. (1998, November 13). The shifting meanings of “black” and “white,” The New York Times , p. WK14.

Stone, L., & Lurquin, P. F. (2007). Genes, culture, and human evolution: A synthesis . Malden, MA: Blackwell.

Wright, L. (1993, July 12). One drop of blood. The New Yorker, pp. 46–54.

Sociology Copyright © 2016 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

National Museum of African American History & Culture

- Plan Your Visit

- Group Visits

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Accessibility Options

- Sweet Home Café

- Museum Store

- Museum Maps

- Our Mobile App

- Search the Collection

- Initiatives

- Museum Centers

- Publications

- Digital Resource Guide

- The Searchable Museum

- Exhibitions

- Freedmen's Bureau Search Portal

- Early Childhood

- Being Antiracist

- Community Building

- Historical Foundations of Race

Race and Racial Identity

- Social Identities and Systems of Oppression

- Why Us? Why Now?

- Digital Learning

- Strategic Partnerships

- Ways to Give

- Internships & Fellowships

- Today at the Museum

- Upcoming Events

- Ongoing Tours & Activities

- Past Events

- Host an Event at NMAAHC

- About the Museum

- The Building

- Meet Our Curators

- Founding Donors

- Corporate Leadership Councils

- NMAAHC Annual Reports

The dictionary's definition of race

Each of the major groupings into which humankind is considered (in various theories or contexts) to be divided on the basis of physical characteristics or shared ancestry.

The notion of race is a social construct designed to divide people into groups ranked as superior and inferior. The scientific consensus is that race, in this sense, has no biological basis – we are all one race, the human race. Racial identity , however, is very real. And, in a racialized society like the United States, everyone is assigned a racial identity whether they are aware of it or not.

Race as Social Construction

The dictionary’s definition of race is incomplete and misses the complexity of impact on lived experiences. It is important to acknowledge race is a social fabrication, created to classify people on the arbitrary basis of skin color and other physical features. Although race has no genetic or scientific basis, the concept of race is important and consequential. Societies use race to establish and justify systems of power, privilege, disenfranchisement, and oppression.

American Anthropological Association states that "the 'racial' worldview was invented to assign some groups to perpetual low status, while others were permitted access to privilege, power, and wealth. The tragedy in the United States has been that the policies and practices stemming from this worldview succeeded all too well in constructing unequal populations among Europeans, Native Americans, and peoples of African descent." To understand more about race as a social construct in the United States, read the AAPA statement on race and racism .

Learn more about race as it relates to human genetics In the Teaching Tolerance report, “Race Does Not Equal DNA”

What is Racial identity?

- Racial identity is externally imposed: “ How do others perceive me? ”

- Racial identity is also internally constructed: “ How do I identify myself? ”

Understanding how our identities and experiences have been shaped by race is vital. We are all awarded certain privileges and or disadvantages because of our race whether or not we are conscious of it.

Race matters. Race matters … because of persistent racial inequality in society - inequality that cannot be ignored. Justice Sonya Sotomayor United States Supreme Court

Developmental models of racial identity

Many sociologists and psychologists have identified that there are similar patterns every individual goes through when recognizing their racial identity. While these patterns help us understand the link between race and identity, creating one’s racial identity is a fluid and nonlinear process that varies for every person and group.

Think of these categories of Racial Identity Development [PDF] as stations along a journey of the continual evolution of your racial identity. Your personal experiences, family, community, workplaces, the aging process, and political and social events – all play a role in understanding our own racial identity. During this process, people move between a desire to "fit in" to dominant norms, to a questioning of one's own identity and that of others. It includes feelings of confusion and often introspection, as well as moments of celebration of self and others. You may begin at any point on this chart and move in any direction – sometimes on the same day! Recognizing the station you are in helps you understand who you are.

What is ideology?

Ideology is a system of ideas, ideals, and manner of thinking that form the basis for decision making, often regarding economic or political theory and policy

No One is Colorblind to Race

The concept of race is intimately connected to our lives and has serious implications. It operates in real and definitive ways that confer benefits and privileges to some and withholds them from others. Ignoring race means ignoring the establishment of racial hierarchies in society and the injustices these hierarchies have created and continue to reinforce.

- READ: “ Children Are Not Colorblind: How Young Children Learn Race ,” by Erin N. Winkler, Ph.D.

Understand More About the Dangers of Ignoring Race

Read this article, “ When you say you 'don't see race,' you’re ignoring racism, not helping to solve it. ”

Reflection:

• What are some experiences or identities that are central to who you are? How do you feel when they are ignored or “not seen”?

• The author in this article points out how people often use nonvisual cues to determine race. What does this reveal to us about the validity of pretending not to see race?

Either America will destroy ignorance, or ignorance will destroy the United States W.E.B. DuBois

RACISM = Racial Prejudice (Unfounded Beliefs + Irrational Fear) + Institutional Power

Racism, like smog, swirls around us and permeates American society. It can be intentional, clear and direct or it can be expressed in more subtle ways that the perpetrator might not even be aware of.

Racism is a system of advantage based on race that involves systems and institutions, not just individual mindsets and actions. The critical variable in racism is the impact (outcomes) not the intent and operates at multiple levels including individual racism, interpersonal racism, institutional racism, and structural racism.

- Interpersonal racism occurs between individuals and includes public expressions of racism, often involving slurs, biases, hateful words or actions, or exclusion.

Source: Adapted from Terry Keleher, Applied Research Center, and Racial Equity Tools by OneTILT

Breaking the Silence Silence on issues of race hurts everyone. Reluctance to directly address the impact of race can result in a lack of connection between people, a loss of our society’s potential and progress, and an escalation of fear and violence. Silence around other issues of identity can also have the same negative impact on society. Silence on race keeps us all from understanding and learning. We can break the silence by being proactive - by learning, reflecting and having courageous conversations with ourselves and others.

VIDEO: Watch below as Franchesca Ramsey discusses racism on MTV’s Decoded (warning: adult language):

Take a moment to reflect

Let's Think

- How are you thinking about your own racialized identity after learning more about race?

- Ask a friend who has a different racial identity than yours to discuss how cultivating a positive sense of racial identity about yourself and others can interrupt racism at every level (personally, socially, and institutionally)?

For concerned citizens:

- Try this exercise to recognize the everyday opportunities you may have that can promote racial equity: Exercise on Choice Points .

- Activity: Try this group activity for talking about race effectively

For Families and Educators: Here are some ways to address race and racism in your classroom:

- Teaching young children about race: a guide for families and teachers

- Tipsfor talking to children about race

Why Us, Why Now?

Subtitle here for the credits modal.

Mulberry Street, Little Italy, New York, c 1900. Photo courtesy Library of Congress

How to see race

Race is a shapeshifting adversary: what seems self-evident takes training to see, and twists under political pressure.

by Gregory Smithsimon + BIO

We think we know what race is. When the United States Census Bureau says that the country will be majority non-white by 2044, that seems like a simple enough statement. But race has always been a weaselly thing.

Today my students, including Black and Latino students, regularly ask me why Asians (supposedly) ‘assimilate’ with whites more quickly than Blacks and Latinos. Strangely, in the 1920s, the US Supreme Court denied Asians citizenship on the basis that they could never assimilate; fast-forward to today, and Asian immigrants are held up as exemplars of assimilation. The fact that race is unyielding enough to shut out someone from the national community, yet malleable enough for my students to believe that it explains a group’s apparent assimilation, hints at what a shapeshifting adversary race is. Race is incredibly tenacious and unforgiving, a source of grave inequality and injustice. Yet over time, racial categories evolve and shift.

To really grasp race, we must accept a double paradox. The first one is a truism of antiracist educators: we can see race, but it’s not real. The second is stranger: race has real consequences, but we can’t see it with the naked eye. Race is a power relationship; racial categories are not about interesting cultural or physical differences, but about putting other people into groups in order to dominate, exploit and attack them. Fundamentally, race makes power visible by assigning it to physical bodies. The evidence of race right before our eyes is not a visual trace of a physical reality, but a by-product of social perceptions, in which we are trained to see certain features as salient or significant. Race does not exist as a matter of biological fact, but only as a consequence of a process of racialisation .

O ccasionally there are historical moments when the creation of race and its political meaning get spelled out explicitly. The US Constitution divided people into white, Black or Indian, which were meant to stand in for power categories: those eligible for citizenship, those subjected to brutal enslavement, and those targeted for genocide. In the first census, each resident counted as one person, each slave as three-fifths a person, and each Indian was not counted at all.

But racialisation is often more insidious. It means that we see things that don’t exist, and fail to recognise things that do. The most powerful racial category is often invisible: whiteness. The benefit of being in power is that whites can imagine that they are the norm and that only other people have race. An early US census instructed people to leave the race section blank if they were white, and indicate only if someone were something else (‘B’ for Black, ‘M’ for Mulatto). Whiteness was literally unmarked.

A brief aside on the politics of typography, in case you’re wondering: throughout this article I leave ‘white’ as is, but I capitalise ‘Black’, as well as ‘Indian’ and ‘Irish’. Why? Well, as the writer and activist W E B DuBois said in the early 20th century, during the decades-long campaign to capitalise ‘Negro’: ‘I believe that 8 million Americans are entitled to a capital letter.’ I could argue that I don’t capitalise white because ‘white’ rarely rises to the level of a cultural identification – but the real reason I don’t is because race is never fair, so it’s fitting for inequality be written into the words we use for races.

Putting whiteness under inspection shows how powerful race is, despite the instability of racial categories. For decades, ‘whiteness’ was an explicit standard for citizenship. (Blacks could technically be citizens, but enjoyed none of the legal benefits. Asians born outside the US were prohibited from becoming citizens until the mid-20th century.) Eligibility for citizenship – painted as whiteness – has remained a category since its inscription in the Constitution, but those eligible for membership in that group have changed. Groups such as Germans, Irish, Italians and Jews were popularly defined as non-citizens and non-white when they first arrived, and then became white. What we see as white today is not the same as it was 100 years ago.

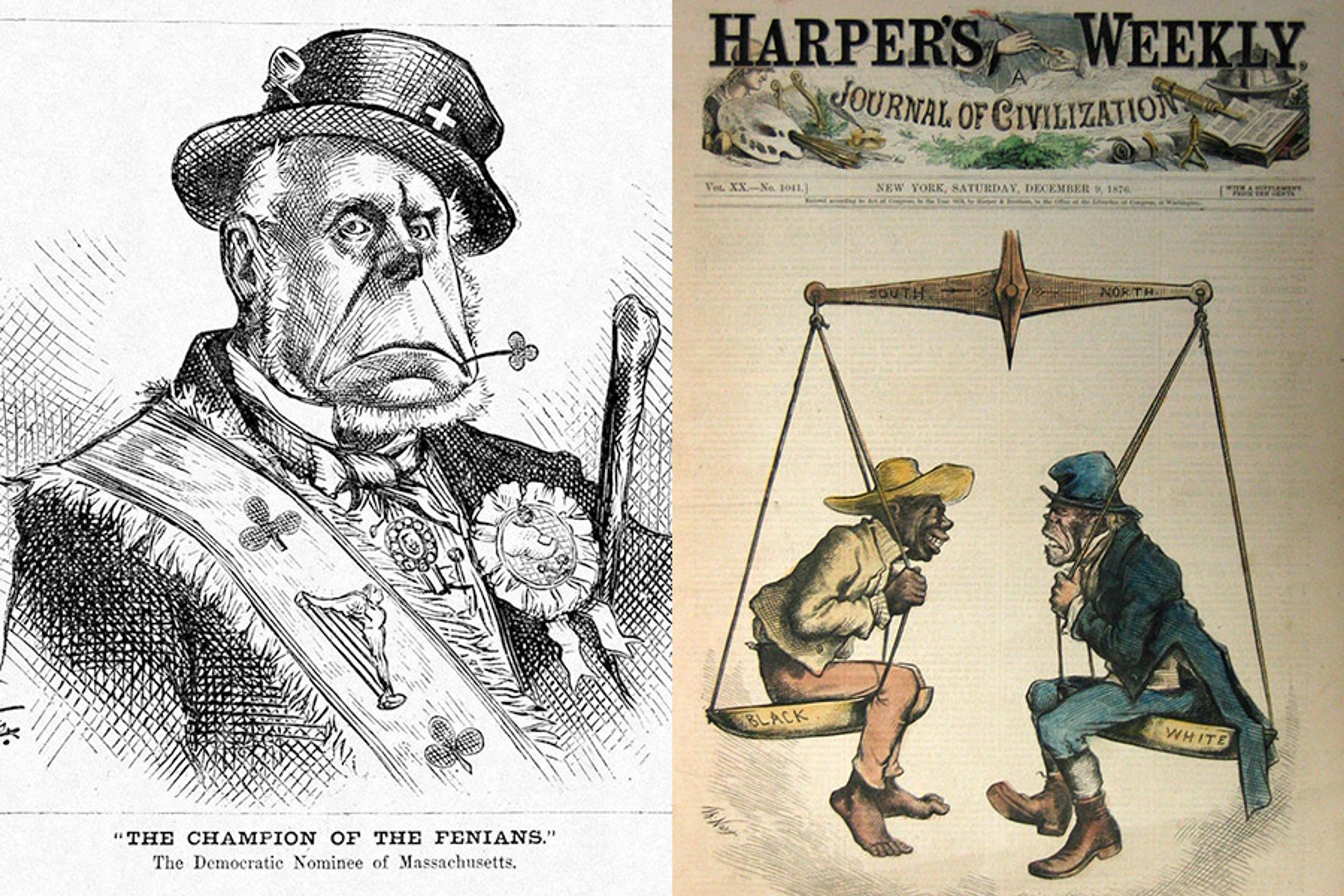

Thomas Nast’s cartoons are notorious in this regard. His caricatures of Irishmen and Blacks are particularly shocking because they are a type we no longer see today. Working-class Irishmen are represented as chimpanzees in crumpled top hats and curled-up shoes. Their faces have a large dome-shaped upper lip surrounded by bushy sideburns:

At times, Nast partnered the Irishman with an equally offensive image of a Black American, with big ‘Sambo’-style lips, perhaps a large rump and clunky bare feet. Today, few Americans have an image in their minds of what an Irish American should look like. Unless, perhaps, they meet a man named O’Connor with red hair, Americans today rarely think to themselves: ‘Of course! He looks Irish.’

Americans can’t see German, Irish or French, but they could . Not all white people look the same

But Nast was not only sketching nasty caricatures of Irishmen; he was doing so in a way that would appear believable to his audience. In a similar example of invisible ethnicity, 15 per cent of Americans in 2014 reported German heritage. This ethnic group is widespread and numerous. So let me pose a simple question: what do German Americans look like? One in seven Americans are German American; how many of the German Americans you meet have you identified that way? Even more so than later immigrant groups such as Italian, Irish or Jewish, German is invisible.

Americans can’t see German, Irish or French, but they could . It’s not the case that all white people look the same. My parents are both of predominantly Irish heritage. One summer, my family was travelling and had a layover in Ireland long enough for us to see the city of Dublin for the first time. We had not left the airport before my seven-year-old son said what I was already thinking: ‘Everybody here looks like grandma and grandpa!’ My family, according to my seven-year-old, looked like people from Ireland.

A few years later, I was to meet a French colleague at a busy Paris train station at rush hour, but neither of us knew what the other one looked like, and there were hundreds of people. I tried to guess which of the women entering, exiting, waiting, smoking, texting and milling about was the person I was to meet, but to no avail. Then I turned, and from a block away, through a crowd of hundreds, a woman waved directly at me. She had picked me out. I had been vaguely aware, before then, that no matter how familiar I got with Paris, I stood out on the subway: I might feel perfectly French riding the train, reading the advertisements in French and understanding the conductor, but when I got home and looked in the mirror, I knew my face was different from the diverse visages I saw in public.

Later I asked my colleague, and she said she knew I wasn’t French. How so? I asked. She scrutinised me. ‘ La mâchoire .’ It was your jaw, she said, with a satisfied smile. Until that day, I never knew there was such a thing as an Irish chin, but I had one. And no doubt, if Nast ever met my earliest American ancestors on the street, he’d know they looked Irish too. We don’t see Irish anymore, we don’t recognise it, we no longer caricature it. But we could.

T he racial category of Asian is just as unstable and entangled with political power as whiteness is. The US census started counting ‘Chinese’ back in 1870 (with no other category for people from the continent of Asia). Around the same time, the census started counting a similarly excluded group, American Indians, which the Constitution had designated as ripe for expropriation. Tellingly, Indian racial categories were unstable from the start: after not being counted at all, Indians were then included but tallied in the ‘white’ column – except in areas where there were large numbers of Indians, where they became their own category.

For Asians, as Paul Schor points out in his fascinating history Counting Americans (2017), the US government counted Chinese and Japanese but still left the rest of Asia blank, adding ‘Filipino, Hindu, and Korean’ in the 20th century. For something so clearly created by people, lists of racial groups are never comprehensive and typically ill-defined. Looking across the Eurasian continent, the US government today is still vague about where white ends and Asian begins. People in the US who were born east of Greece and west of Thailand are often unsure which boxes to check in the US census every 10 years. Like storm-borne waves or wind-blown sand dunes, race is a daunting obstacle that shifts and changes.

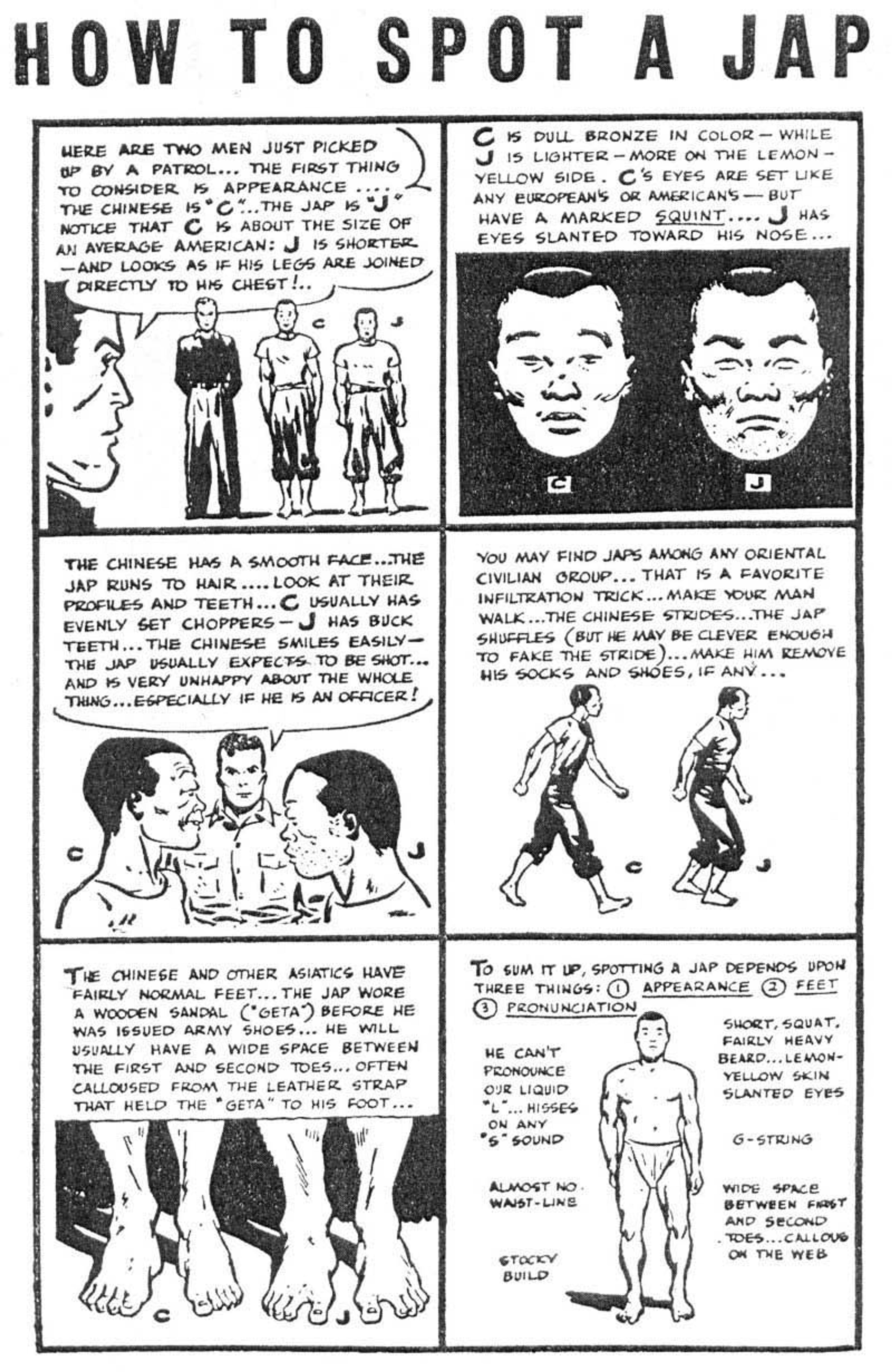

During the Second World War, China was a US ally, while Japan was an enemy. The US military decided it necessary to identify racial differences between the Chinese and the Japanese. In a series of cartoon illustrations, they tried to educate American soldiers about what to look for – what to see – in order to distinguish a Japanese solider who might be trying to blend in among a Chinese population.

Today, the ‘How to Spot a Jap’ leaflets are an offensive novelty – used either to illustrate the history of racist stereotyping or sold on postcards as ironic curiosities. But they can also be examined in another way. In The Civilizing Process (1978), the sociological theorist Norbert Elias studied books on manners from the European Renaissance to understand the process of the creation of what he called habitus . Manners that we see as utterly natural and inevitable today, like not blowing one’s nose at the table, or eating off the serving spoon, or belching or farting in public, are, in fact, socially constructed and learned behaviours.

At the historical moment at which they were introduced, books of manners were required to teach what is today utterly obvious to adults. They make for incredible reading. In his chapter ‘On Blowing One’s Nose’, for instance, Elias quotes a ‘precept for gentlemen’ that matter-of-factly explains: ‘When you blow your nose or cough, turn round so that nothing falls on the table.’ ‘Do not blow your nose with the same hand that you use to hold the meat.’ ‘It is unseemly to blow your nose into the tablecloth.’ Some of the recommendations are as poetic as they are graphic: ‘Nor is it seemly, after wiping your nose, to spread out your handkerchief and peer into it as if pearls and rubies might have fallen out of your head.’ It appears that actions that seem completely natural had to be taught explicitly.

Genetic inheritance isn’t what matters. What we literally see is shaped by politics