7.3 Problem-Solving

Learning objectives.

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Describe problem solving strategies

- Define algorithm and heuristic

- Explain some common roadblocks to effective problem solving

People face problems every day—usually, multiple problems throughout the day. Sometimes these problems are straightforward: To double a recipe for pizza dough, for example, all that is required is that each ingredient in the recipe be doubled. Sometimes, however, the problems we encounter are more complex. For example, say you have a work deadline, and you must mail a printed copy of a report to your supervisor by the end of the business day. The report is time-sensitive and must be sent overnight. You finished the report last night, but your printer will not work today. What should you do? First, you need to identify the problem and then apply a strategy for solving the problem.

The study of human and animal problem solving processes has provided much insight toward the understanding of our conscious experience and led to advancements in computer science and artificial intelligence. Essentially much of cognitive science today represents studies of how we consciously and unconsciously make decisions and solve problems. For instance, when encountered with a large amount of information, how do we go about making decisions about the most efficient way of sorting and analyzing all the information in order to find what you are looking for as in visual search paradigms in cognitive psychology. Or in a situation where a piece of machinery is not working properly, how do we go about organizing how to address the issue and understand what the cause of the problem might be. How do we sort the procedures that will be needed and focus attention on what is important in order to solve problems efficiently. Within this section we will discuss some of these issues and examine processes related to human, animal and computer problem solving.

PROBLEM-SOLVING STRATEGIES

When people are presented with a problem—whether it is a complex mathematical problem or a broken printer, how do you solve it? Before finding a solution to the problem, the problem must first be clearly identified. After that, one of many problem solving strategies can be applied, hopefully resulting in a solution.

Problems themselves can be classified into two different categories known as ill-defined and well-defined problems (Schacter, 2009). Ill-defined problems represent issues that do not have clear goals, solution paths, or expected solutions whereas well-defined problems have specific goals, clearly defined solutions, and clear expected solutions. Problem solving often incorporates pragmatics (logical reasoning) and semantics (interpretation of meanings behind the problem), and also in many cases require abstract thinking and creativity in order to find novel solutions. Within psychology, problem solving refers to a motivational drive for reading a definite “goal” from a present situation or condition that is either not moving toward that goal, is distant from it, or requires more complex logical analysis for finding a missing description of conditions or steps toward that goal. Processes relating to problem solving include problem finding also known as problem analysis, problem shaping where the organization of the problem occurs, generating alternative strategies, implementation of attempted solutions, and verification of the selected solution. Various methods of studying problem solving exist within the field of psychology including introspection, behavior analysis and behaviorism, simulation, computer modeling, and experimentation.

A problem-solving strategy is a plan of action used to find a solution. Different strategies have different action plans associated with them (table below). For example, a well-known strategy is trial and error. The old adage, “If at first you don’t succeed, try, try again” describes trial and error. In terms of your broken printer, you could try checking the ink levels, and if that doesn’t work, you could check to make sure the paper tray isn’t jammed. Or maybe the printer isn’t actually connected to your laptop. When using trial and error, you would continue to try different solutions until you solved your problem. Although trial and error is not typically one of the most time-efficient strategies, it is a commonly used one.

Another type of strategy is an algorithm. An algorithm is a problem-solving formula that provides you with step-by-step instructions used to achieve a desired outcome (Kahneman, 2011). You can think of an algorithm as a recipe with highly detailed instructions that produce the same result every time they are performed. Algorithms are used frequently in our everyday lives, especially in computer science. When you run a search on the Internet, search engines like Google use algorithms to decide which entries will appear first in your list of results. Facebook also uses algorithms to decide which posts to display on your newsfeed. Can you identify other situations in which algorithms are used?

A heuristic is another type of problem solving strategy. While an algorithm must be followed exactly to produce a correct result, a heuristic is a general problem-solving framework (Tversky & Kahneman, 1974). You can think of these as mental shortcuts that are used to solve problems. A “rule of thumb” is an example of a heuristic. Such a rule saves the person time and energy when making a decision, but despite its time-saving characteristics, it is not always the best method for making a rational decision. Different types of heuristics are used in different types of situations, but the impulse to use a heuristic occurs when one of five conditions is met (Pratkanis, 1989):

- When one is faced with too much information

- When the time to make a decision is limited

- When the decision to be made is unimportant

- When there is access to very little information to use in making the decision

- When an appropriate heuristic happens to come to mind in the same moment

Working backwards is a useful heuristic in which you begin solving the problem by focusing on the end result. Consider this example: You live in Washington, D.C. and have been invited to a wedding at 4 PM on Saturday in Philadelphia. Knowing that Interstate 95 tends to back up any day of the week, you need to plan your route and time your departure accordingly. If you want to be at the wedding service by 3:30 PM, and it takes 2.5 hours to get to Philadelphia without traffic, what time should you leave your house? You use the working backwards heuristic to plan the events of your day on a regular basis, probably without even thinking about it.

Another useful heuristic is the practice of accomplishing a large goal or task by breaking it into a series of smaller steps. Students often use this common method to complete a large research project or long essay for school. For example, students typically brainstorm, develop a thesis or main topic, research the chosen topic, organize their information into an outline, write a rough draft, revise and edit the rough draft, develop a final draft, organize the references list, and proofread their work before turning in the project. The large task becomes less overwhelming when it is broken down into a series of small steps.

Further problem solving strategies have been identified (listed below) that incorporate flexible and creative thinking in order to reach solutions efficiently.

Additional Problem Solving Strategies :

- Abstraction – refers to solving the problem within a model of the situation before applying it to reality.

- Analogy – is using a solution that solves a similar problem.

- Brainstorming – refers to collecting an analyzing a large amount of solutions, especially within a group of people, to combine the solutions and developing them until an optimal solution is reached.

- Divide and conquer – breaking down large complex problems into smaller more manageable problems.

- Hypothesis testing – method used in experimentation where an assumption about what would happen in response to manipulating an independent variable is made, and analysis of the affects of the manipulation are made and compared to the original hypothesis.

- Lateral thinking – approaching problems indirectly and creatively by viewing the problem in a new and unusual light.

- Means-ends analysis – choosing and analyzing an action at a series of smaller steps to move closer to the goal.

- Method of focal objects – putting seemingly non-matching characteristics of different procedures together to make something new that will get you closer to the goal.

- Morphological analysis – analyzing the outputs of and interactions of many pieces that together make up a whole system.

- Proof – trying to prove that a problem cannot be solved. Where the proof fails becomes the starting point or solving the problem.

- Reduction – adapting the problem to be as similar problems where a solution exists.

- Research – using existing knowledge or solutions to similar problems to solve the problem.

- Root cause analysis – trying to identify the cause of the problem.

The strategies listed above outline a short summary of methods we use in working toward solutions and also demonstrate how the mind works when being faced with barriers preventing goals to be reached.

One example of means-end analysis can be found by using the Tower of Hanoi paradigm . This paradigm can be modeled as a word problems as demonstrated by the Missionary-Cannibal Problem :

Missionary-Cannibal Problem

Three missionaries and three cannibals are on one side of a river and need to cross to the other side. The only means of crossing is a boat, and the boat can only hold two people at a time. Your goal is to devise a set of moves that will transport all six of the people across the river, being in mind the following constraint: The number of cannibals can never exceed the number of missionaries in any location. Remember that someone will have to also row that boat back across each time.

Hint : At one point in your solution, you will have to send more people back to the original side than you just sent to the destination.

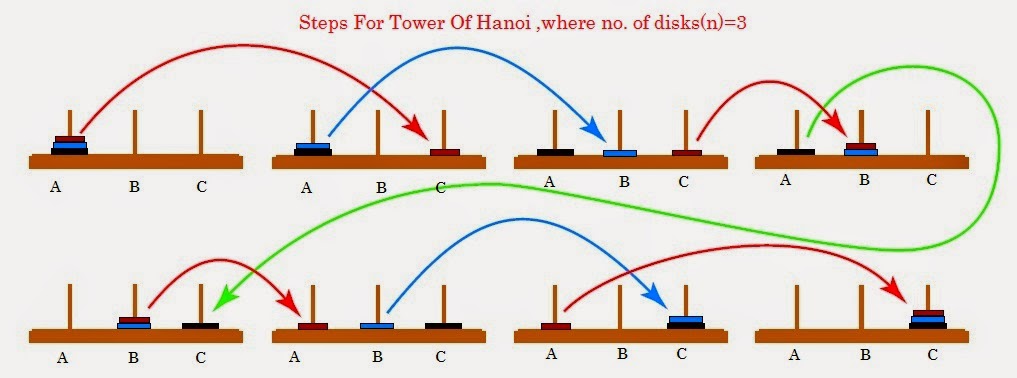

The actual Tower of Hanoi problem consists of three rods sitting vertically on a base with a number of disks of different sizes that can slide onto any rod. The puzzle starts with the disks in a neat stack in ascending order of size on one rod, the smallest at the top making a conical shape. The objective of the puzzle is to move the entire stack to another rod obeying the following rules:

- 1. Only one disk can be moved at a time.

- 2. Each move consists of taking the upper disk from one of the stacks and placing it on top of another stack or on an empty rod.

- 3. No disc may be placed on top of a smaller disk.

Figure 7.02. Steps for solving the Tower of Hanoi in the minimum number of moves when there are 3 disks.

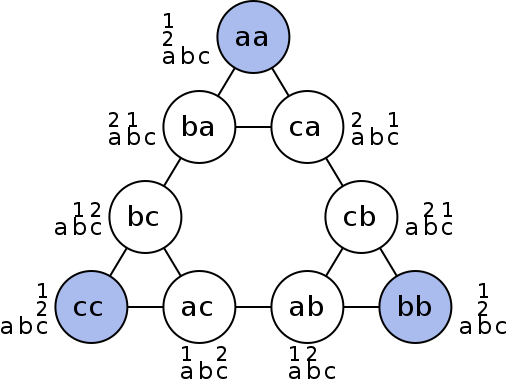

Figure 7.03. Graphical representation of nodes (circles) and moves (lines) of Tower of Hanoi.

The Tower of Hanoi is a frequently used psychological technique to study problem solving and procedure analysis. A variation of the Tower of Hanoi known as the Tower of London has been developed which has been an important tool in the neuropsychological diagnosis of executive function disorders and their treatment.

GESTALT PSYCHOLOGY AND PROBLEM SOLVING

As you may recall from the sensation and perception chapter, Gestalt psychology describes whole patterns, forms and configurations of perception and cognition such as closure, good continuation, and figure-ground. In addition to patterns of perception, Wolfgang Kohler, a German Gestalt psychologist traveled to the Spanish island of Tenerife in order to study animals behavior and problem solving in the anthropoid ape.

As an interesting side note to Kohler’s studies of chimp problem solving, Dr. Ronald Ley, professor of psychology at State University of New York provides evidence in his book A Whisper of Espionage (1990) suggesting that while collecting data for what would later be his book The Mentality of Apes (1925) on Tenerife in the Canary Islands between 1914 and 1920, Kohler was additionally an active spy for the German government alerting Germany to ships that were sailing around the Canary Islands. Ley suggests his investigations in England, Germany and elsewhere in Europe confirm that Kohler had served in the German military by building, maintaining and operating a concealed radio that contributed to Germany’s war effort acting as a strategic outpost in the Canary Islands that could monitor naval military activity approaching the north African coast.

While trapped on the island over the course of World War 1, Kohler applied Gestalt principles to animal perception in order to understand how they solve problems. He recognized that the apes on the islands also perceive relations between stimuli and the environment in Gestalt patterns and understand these patterns as wholes as opposed to pieces that make up a whole. Kohler based his theories of animal intelligence on the ability to understand relations between stimuli, and spent much of his time while trapped on the island investigation what he described as insight , the sudden perception of useful or proper relations. In order to study insight in animals, Kohler would present problems to chimpanzee’s by hanging some banana’s or some kind of food so it was suspended higher than the apes could reach. Within the room, Kohler would arrange a variety of boxes, sticks or other tools the chimpanzees could use by combining in patterns or organizing in a way that would allow them to obtain the food (Kohler & Winter, 1925).

While viewing the chimpanzee’s, Kohler noticed one chimp that was more efficient at solving problems than some of the others. The chimp, named Sultan, was able to use long poles to reach through bars and organize objects in specific patterns to obtain food or other desirables that were originally out of reach. In order to study insight within these chimps, Kohler would remove objects from the room to systematically make the food more difficult to obtain. As the story goes, after removing many of the objects Sultan was used to using to obtain the food, he sat down ad sulked for a while, and then suddenly got up going over to two poles lying on the ground. Without hesitation Sultan put one pole inside the end of the other creating a longer pole that he could use to obtain the food demonstrating an ideal example of what Kohler described as insight. In another situation, Sultan discovered how to stand on a box to reach a banana that was suspended from the rafters illustrating Sultan’s perception of relations and the importance of insight in problem solving.

Grande (another chimp in the group studied by Kohler) builds a three-box structure to reach the bananas, while Sultan watches from the ground. Insight , sometimes referred to as an “Ah-ha” experience, was the term Kohler used for the sudden perception of useful relations among objects during problem solving (Kohler, 1927; Radvansky & Ashcraft, 2013).

Solving puzzles.

Problem-solving abilities can improve with practice. Many people challenge themselves every day with puzzles and other mental exercises to sharpen their problem-solving skills. Sudoku puzzles appear daily in most newspapers. Typically, a sudoku puzzle is a 9×9 grid. The simple sudoku below (see figure) is a 4×4 grid. To solve the puzzle, fill in the empty boxes with a single digit: 1, 2, 3, or 4. Here are the rules: The numbers must total 10 in each bolded box, each row, and each column; however, each digit can only appear once in a bolded box, row, and column. Time yourself as you solve this puzzle and compare your time with a classmate.

How long did it take you to solve this sudoku puzzle? (You can see the answer at the end of this section.)

Here is another popular type of puzzle (figure below) that challenges your spatial reasoning skills. Connect all nine dots with four connecting straight lines without lifting your pencil from the paper:

Did you figure it out? (The answer is at the end of this section.) Once you understand how to crack this puzzle, you won’t forget.

Take a look at the “Puzzling Scales” logic puzzle below (figure below). Sam Loyd, a well-known puzzle master, created and refined countless puzzles throughout his lifetime (Cyclopedia of Puzzles, n.d.).

What steps did you take to solve this puzzle? You can read the solution at the end of this section.

Pitfalls to problem solving.

Not all problems are successfully solved, however. What challenges stop us from successfully solving a problem? Albert Einstein once said, “Insanity is doing the same thing over and over again and expecting a different result.” Imagine a person in a room that has four doorways. One doorway that has always been open in the past is now locked. The person, accustomed to exiting the room by that particular doorway, keeps trying to get out through the same doorway even though the other three doorways are open. The person is stuck—but she just needs to go to another doorway, instead of trying to get out through the locked doorway. A mental set is where you persist in approaching a problem in a way that has worked in the past but is clearly not working now.

Functional fixedness is a type of mental set where you cannot perceive an object being used for something other than what it was designed for. During the Apollo 13 mission to the moon, NASA engineers at Mission Control had to overcome functional fixedness to save the lives of the astronauts aboard the spacecraft. An explosion in a module of the spacecraft damaged multiple systems. The astronauts were in danger of being poisoned by rising levels of carbon dioxide because of problems with the carbon dioxide filters. The engineers found a way for the astronauts to use spare plastic bags, tape, and air hoses to create a makeshift air filter, which saved the lives of the astronauts.

Researchers have investigated whether functional fixedness is affected by culture. In one experiment, individuals from the Shuar group in Ecuador were asked to use an object for a purpose other than that for which the object was originally intended. For example, the participants were told a story about a bear and a rabbit that were separated by a river and asked to select among various objects, including a spoon, a cup, erasers, and so on, to help the animals. The spoon was the only object long enough to span the imaginary river, but if the spoon was presented in a way that reflected its normal usage, it took participants longer to choose the spoon to solve the problem. (German & Barrett, 2005). The researchers wanted to know if exposure to highly specialized tools, as occurs with individuals in industrialized nations, affects their ability to transcend functional fixedness. It was determined that functional fixedness is experienced in both industrialized and nonindustrialized cultures (German & Barrett, 2005).

In order to make good decisions, we use our knowledge and our reasoning. Often, this knowledge and reasoning is sound and solid. Sometimes, however, we are swayed by biases or by others manipulating a situation. For example, let’s say you and three friends wanted to rent a house and had a combined target budget of $1,600. The realtor shows you only very run-down houses for $1,600 and then shows you a very nice house for $2,000. Might you ask each person to pay more in rent to get the $2,000 home? Why would the realtor show you the run-down houses and the nice house? The realtor may be challenging your anchoring bias. An anchoring bias occurs when you focus on one piece of information when making a decision or solving a problem. In this case, you’re so focused on the amount of money you are willing to spend that you may not recognize what kinds of houses are available at that price point.

The confirmation bias is the tendency to focus on information that confirms your existing beliefs. For example, if you think that your professor is not very nice, you notice all of the instances of rude behavior exhibited by the professor while ignoring the countless pleasant interactions he is involved in on a daily basis. Hindsight bias leads you to believe that the event you just experienced was predictable, even though it really wasn’t. In other words, you knew all along that things would turn out the way they did. Representative bias describes a faulty way of thinking, in which you unintentionally stereotype someone or something; for example, you may assume that your professors spend their free time reading books and engaging in intellectual conversation, because the idea of them spending their time playing volleyball or visiting an amusement park does not fit in with your stereotypes of professors.

Finally, the availability heuristic is a heuristic in which you make a decision based on an example, information, or recent experience that is that readily available to you, even though it may not be the best example to inform your decision . Biases tend to “preserve that which is already established—to maintain our preexisting knowledge, beliefs, attitudes, and hypotheses” (Aronson, 1995; Kahneman, 2011). These biases are summarized in the table below.

Were you able to determine how many marbles are needed to balance the scales in the figure below? You need nine. Were you able to solve the problems in the figures above? Here are the answers.

Many different strategies exist for solving problems. Typical strategies include trial and error, applying algorithms, and using heuristics. To solve a large, complicated problem, it often helps to break the problem into smaller steps that can be accomplished individually, leading to an overall solution. Roadblocks to problem solving include a mental set, functional fixedness, and various biases that can cloud decision making skills.

References:

Openstax Psychology text by Kathryn Dumper, William Jenkins, Arlene Lacombe, Marilyn Lovett and Marion Perlmutter licensed under CC BY v4.0. https://openstax.org/details/books/psychology

Review Questions:

1. A specific formula for solving a problem is called ________.

a. an algorithm

b. a heuristic

c. a mental set

d. trial and error

2. Solving the Tower of Hanoi problem tends to utilize a ________ strategy of problem solving.

a. divide and conquer

b. means-end analysis

d. experiment

3. A mental shortcut in the form of a general problem-solving framework is called ________.

4. Which type of bias involves becoming fixated on a single trait of a problem?

a. anchoring bias

b. confirmation bias

c. representative bias

d. availability bias

5. Which type of bias involves relying on a false stereotype to make a decision?

6. Wolfgang Kohler analyzed behavior of chimpanzees by applying Gestalt principles to describe ________.

a. social adjustment

b. student load payment options

c. emotional learning

d. insight learning

7. ________ is a type of mental set where you cannot perceive an object being used for something other than what it was designed for.

a. functional fixedness

c. working memory

Critical Thinking Questions:

1. What is functional fixedness and how can overcoming it help you solve problems?

2. How does an algorithm save you time and energy when solving a problem?

Personal Application Question:

1. Which type of bias do you recognize in your own decision making processes? How has this bias affected how you’ve made decisions in the past and how can you use your awareness of it to improve your decisions making skills in the future?

anchoring bias

availability heuristic

confirmation bias

functional fixedness

hindsight bias

problem-solving strategy

representative bias

trial and error

working backwards

Answers to Exercises

algorithm: problem-solving strategy characterized by a specific set of instructions

anchoring bias: faulty heuristic in which you fixate on a single aspect of a problem to find a solution

availability heuristic: faulty heuristic in which you make a decision based on information readily available to you

confirmation bias: faulty heuristic in which you focus on information that confirms your beliefs

functional fixedness: inability to see an object as useful for any other use other than the one for which it was intended

heuristic: mental shortcut that saves time when solving a problem

hindsight bias: belief that the event just experienced was predictable, even though it really wasn’t

mental set: continually using an old solution to a problem without results

problem-solving strategy: method for solving problems

representative bias: faulty heuristic in which you stereotype someone or something without a valid basis for your judgment

trial and error: problem-solving strategy in which multiple solutions are attempted until the correct one is found

working backwards: heuristic in which you begin to solve a problem by focusing on the end result

Share This Book

- Increase Font Size

- Search Menu

- The Journals of Gerontology, Series B (1995-present)

- Journal of Gerontology (1946-1994)

- Advance Articles

- Editor's Choice

- Virtual Collection

- Supplements

- Special Issues

- Calls for Papers

- Author Guidelines

- Psychological Sciences Submission Site

- Social Sciences Submission Site

- Why Submit to the GSA Portfolio?

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Advertising

- Reprints and ePrints

- Sponsored Supplements

- Journals Career Network

- About The Journals of Gerontology, Series B

- About The Gerontological Society of America

- Editorial Board - Psychological Sciences

- Editorial Board - Social Sciences

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- GSA Journals

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

D iscussion.

- < Previous

Age Differences in Everyday Problem-Solving Effectiveness: Older Adults Select More Effective Strategies for Interpersonal Problems

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Fredda Blanchard-Fields, Andrew Mienaltowski, Renee Baldi Seay, Age Differences in Everyday Problem-Solving Effectiveness: Older Adults Select More Effective Strategies for Interpersonal Problems, The Journals of Gerontology: Series B , Volume 62, Issue 1, January 2007, Pages P61–P64, https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/62.1.P61

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Using the Everyday Problem Solving Inventory of Cornelius and Caspi, we examined differences in problem-solving strategy endorsement and effectiveness in two domains of everyday functioning (instrumental or interpersonal, and a mixture of the two domains) and for four strategies (avoidance–denial, passive dependence, planful problem solving, and cognitive analysis). Consistent with past research, our research showed that older adults were more problem focused than young adults in their approach to solving instrumental problems, whereas older adults selected more avoidant–denial strategies than young adults when solving interpersonal problems. Overall, older adults were also more effective than young adults when solving everyday problems, in particular for interpersonal problems.

DESPITE cognitive declines associated with advancing age ( Zacks, Hasher, & Li 2000 ), older adults function independently. Furthermore, evidence is equivocal as to the impact that cognitive decline has on older adults' abilities to navigate complicated social situations (see, e.g., Cornelius & Caspi, 1987 ; Marsiske & Willis, 1995 ). Some research suggests that older adults are more effective than young adults when solving everyday problems (Cornelius & Caspi; Blanchard-Fields, Chen, & Norris, 1997 ; Blanchard-Fields, Jahnke, & Camp, 1995 ; Blanchard-Fields, Stein, & Watson, 2004 ). Our goal in the current study was to examine age differences in (a) the strategies selected to solve everyday problems from different problem domains and (b) how effective these strategy choices are relative to ideal everyday problem solutions.

Blanchard-Fields and colleagues (1995 , 1997 , 2004 ) demonstrated that older adults are equally likely, if not more likely, than young adults to choose proactive strategies to directly confront instrumental problems. However, when they are facing interpersonal problems, older adults are more likely than young adults to choose passive emotion regulation strategies. Differential strategy preferences may reflect a maturing of the strategy repertoire of older adults. As people age, experience may hone strategy preferences on the basis of successes and failures, making it easier for older adults to invest energy into strategies that have been effectively used when dealing with problems in the past.

The important issue is what constitutes effective strategy use. Past research defines it as one's sensitivity to the context that is underlying problems when one is selecting strategies ( Blanchard-Fields et al., 1995 ), the number of strategies and one's satisfaction with problem solution ( Thornton & Dumke, 2005 ), or the evaluation of strategy choices on an everyday problem-solving inventory against a panel of external judges ( Cornelius & Caspi, 1987 ). In the current study we examined the latter approach to problem-solving effectiveness from the level of domain-specific strategy use in order to simultaneously investigate age differences in effective problem solving and age differences in strategy selection (i.e., differential strategy preference related to context). We sought to replicate past research examining interpersonal and instrumental problem-solving contexts, while also determining whether age differences in strategy preferences actually lead to more effective problem solving in the two domains. Because domain effects are sensitive to the amount of overlap that is allowed between problem definitions when problems are classified (e.g., Artistico, Cervone, & Pezzuti, 2003 ), we expanded the typical instrumental–interpersonal dichotomy by adding a mixed-problem domain to describe problems that are not unambiguously instrumental or interpersonal.

We expected older adults to show a greater preference than young adults for emotion-focused strategies when they were solving interpersonal problems. For instrumental problems, we expected older adults to prefer more problem-focused strategies than did young adults. We also expected older adults to have higher effectiveness scores than young adults ( Cornelius & Caspi, 1987 ). Finally, we expected older adults to be more effective than young adults in their application of emotion-focused strategies.

Participants

We recruited young adults ( n = 53, with 36 women and 17 men; age = 18–27 years, M = 20.6, SD = 1.6) and older adults ( n = 53, with 33 men and 20 women; age = 60–80 years, M = 68.9, SD = 4.9) from a southeastern metropolitan area. Participants were primarily Caucasian (∼77%) and reported similar levels of education (i.e., some college). On average, both groups indicated good health [young adults, M = 3.49, SE = 0.08; older adults, M = 3.15, SE = 0.09; t (1, 102) = 2.89, p <.01].

Everyday problem-solving task

We selected 24 of 48 hypothetical problems from the Everyday Problem Solving Inventory (EPSI; Cornelius & Caspi, 1987 ). We randomly selected 4 problems from each of the six original problem domains (i.e., home management, information use, consumer issues, conflicts with friends, work-related issues, and family conflicts). We presented participants with a single manifestation of each strategy type tailored to each problem (without strategy labels) and asked them to indicate how likely they were to use each of four strategies to solve each problem: avoidance–denial, passive dependence, planful problem solving, and cognitive analysis (see Table 1 for strategy definitions).

Dependent variables

Strategy endorsement ratings indicated participants' preferred methods for solving hypothetical everyday problems. Higher scores represented greater endorsement of a particular strategy. We calculated effectiveness scores for each domain and strategy by correlating participant strategy endorsement ratings with those of a panel of external judges ( Cornelius & Caspi, 1987 ). 1 Correlations (range: r = −1.0 to r = 1.0) represented the degree of similarity between a participant's responses and the ideal solutions nominated by judges. Large positive correlations indicated effective problem solving.

Classification of problem type

For each problem indicate whether it is an (A) instrumental problem, or (B) interpersonal problem. Instrumental problems involve competence concerns and stem from complications that arise when one is trying to accomplish, achieve, or get better at something. Instrumental problems are situations in which one is having difficulty achieving something that is personally relevant. Interpersonal problems involve social/interpersonal concerns and stem from complications that arise when one is trying to reach an outcome that involves other people. Interpersonal problems are situations in which one is dealing with a social conflict or obstacle in a relationship. Please provide only one classification per problem.

We conducted 2 (age: young, old) × 3 (domain: instrumental, mixed, interpersonal) × 4 (strategy: avoidance–denial, passive dependence, planful problem solving, cognitive analysis) mixed-model analyses of variance on the strategy endorsement and effectiveness scores. Age was the between-subjects factor. We followed each analysis of variance by contrasts to examine age differences for each strategy by domain.

Strategy endorsement ratings

For each domain (interpersonal, instrumental, or mixed), we calculated average endorsement ratings for each strategy type (e.g., avoidance–denial). Analyses indicated that main effects of domain, F (2, 312) = 34.57 (η p 2 =.25, p <.001), and strategy, F (2, 312) = 265.54 (η p 2 =.72, p <.001), were qualified by Strategy × Age, F (3, 312) = 5.46 (η p 2 =.05, p =.001), Domain × Strategy, F (6, 624) = 46.59 (η p 2 =.31, p <.001), and Domain × Strategy × Age, F (6, 624) = 5.30 (η p 2 =.05, p <.001), interactions. The patterns of age differences in strategy endorsement varied by domain (see Table 2 for mean strategy endorsement ratings). For instrumental problems, young adults preferred avoidance–denial more than old adults did, t (104) = 2.26 ( p <.05), whereas old adults preferred passive dependence, t (104) = 2.28 ( p <.05), planful problem solving, t (104) = 3.74 ( p <.001), and cognitive analysis, t (104) = 3.30 ( p <.01), more than young adults did. For mixed problems, young adults preferred avoidance–denial, t (104) = 4.36 ( p <.001), and passive dependence, t (104) = 3.87 ( p <.001), more than old adults did. The opposite pattern held for interpersonal problems. Old adults preferred avoidance–denial, t (104) = 2.15 ( p <.05), and cognitive analysis, t (104) = 2.39 ( p <.05), more than young adults did. Old adults also marginally preferred passive dependence more than young did, t (104) = 1.42 ( p =.08, one-tail).

Effectiveness scores

For each domain and each strategy, we calculated an overall effectiveness score across problems by correlating each participant's strategy endorsement ratings with the effectiveness ratings of the judges (e.g., avoidance–denial strategies for each interpersonal problem and judges' average rating for avoidance–denial for the same problems). Analyses indicated main effects of age, F (1, 92) = 7.15 (η p 2 =.07, p <.01), and domain, F (2, 184) = 18.66 (η p 2 =.17, p <.001). Older adults ( M = 0.46, SE = 0.02) were more effective than young adults ( M = 0.39, SE = 0.02) in their overall choice of strategies ( Cornelius & Caspi, 1987 ). These main effects were qualified by Domain × Age, F (2, 184) = 3.04 (η p 2 =.03, p =.05), and Domain × Strategy, F (6, 552) = 44.19 (η p 2 =.32, p <.001), interactions (see Table 2 for mean strategy effectiveness scores). Although both age groups were more effective at solving instrumental problems (young adults, M = 0.40, SE = 0.02; old adults, M = 0.48, SE = 0.02) and mixed problems (young adults, M = 0.50, SE = 0.03; old adults, M = 0.50, SE = 0.03) than interpersonal problems, young adults were especially less effective than old adults at solving interpersonal problems (young adults, M = 0.27, SE = 0.03; old adults, M = 0.41, SE = 0.03).

Although the Domain × Strategy × Age interaction failed to reach significance, F (6, 552) = 1.67 (η p 2 =.02, p =.13), we conducted planned contrasts to investigate age differences in problem-solving effectiveness for each strategy by domain. For interpersonal problems, old adults were more consistent than young adults in endorsing avoidance–denial, t (103) = 1.90 ( p <.05, one-tail), passive dependence, t (104) = 1.30 (only marginal at p =.10, one-tail), planful problem solving, t (105) = 1.65 ( p <.05), and cognitive analysis, t (96) = 1.72 ( p <.05), at levels that were deemed to be effective by the judges. For instrumental problems, old adults were more consistent than young adults in endorsing avoidance–denial, t (104) = 4.21 ( p <.001), at the level deemed to be effective by the judges. No age differences emerged for mixed problems. 2

Consistent with past research, in our research the older adults preferred more passive emotion-focused strategies (e.g., avoidance or passive dependence) than the young adults did when facing interpersonal problems, and they preferred more proactive strategies such as planful problem solving (in combination with emotion regulation strategies) for instrumental problems ( Blanchard-Fields et al., 1995 , 1997 ; Watson & Blanchard-Fields, 1998 ). In contrast, young adults used similar amounts of planful problem solving, irrespective of the type of problem. It is interesting to note that young adults preferred (a) more passive emotion-focused strategies in mixed problems and (b) more avoidance emotion-focused strategies in instrumental problems than older adults. Perhaps young adults are motivated to behave more passively when managing personally relevant achievement-oriented problems, especially those involving potentially awkward social interactions. This deserves further research.

Second, we moved beyond previous indices of effectiveness by basing problem-solving efficacy on the degree of similarity in strategy endorsement between participants and a panel of judges to control for individual differences in strategy accessibility. Older adults were more effective at solving problems than young adults were (which is similar to the findings of Cornelius & Caspi, 1987 ). More importantly, we found that older adults' greater effectiveness was driven by strategy selection within interpersonal problems. Extending past research, we assessed effectiveness at the level of the problem domain and at the level of specific strategies. Thus, it is not simply that older people use more or less of a strategy in various domains; they use these strategies appropriately (as determined by panel effectiveness scores) to match the context of the problem. This adaptivity may be crucial to interpersonal problems. Although proactive strategies are typically key to resolving causes of problems (e.g., Thornton & Dumke, 2005 ), older adults' use of passive (emotion regulation) strategies may buffer them from intense emotional reactions in order to maintain tolerable levels of arousal given increased vulnerability and reduced energy reserves (Consedine, Magai, & Bonanno, 2003).

One limitation of the EPSI is that effective solutions tend to be biased toward instrumental strategies. Nevertheless, we still find older adults to be more effective in their application of emotion-focused strategies in the interpersonal domain. Future research must include a greater balance in situations in which both problem-focused and emotion-focused strategies are judged effective. Another limitation is that the EPSI problem contexts are sparse. Thus, problem appraisal could possibly play a role in producing age differences in strategy preference. Past research demonstrates age differences in problem definitions ( Berg et al., 1998 ) and goals evoked when approaching problems ( Strough, Berg, & Sansone, 1996 ). A third limitation of the current study is that we did not control for age relevance of each problem. Future research should address how age relevance influences problem-solving effectiveness, especially as it pertains to emotion regulation in interpersonal problems and to whether age differences in effectiveness are maintained for the oldest-old individuals.

Given recent interest in the role of emotion in older adulthood, these findings are significant because they provide further evidence for the capacity of older adults to draw on accumulated experience in socioemotional realms to solve problems successfully. Older adults' strategy use suggests that they are capable of complex and flexible problem solving. Furthermore, whereas advancing age is associated with cognitive decline, such declines do not readily translate into impaired everyday problem-solving effectiveness. Instead, both types of developmental trajectories exist in tandem and may even complement one another.

Cornelius and Caspi (1987) recruited 23 judges to determine which of four strategies could be used to effectively solve a series of everyday problems. Of these 23 judges, 18 were “laypersons without formal training in psychology” and 5 were “graduate students majoring in developmental psychology” (p. 146). Overall, the panel consisted of young adults ( n = 9, ages 24–40, M = 28.4), middle-aged adults ( n = 8, ages 44–54, M = 50.3), and older adults ( n = 6, ages 62–72, M = 67.3). Ten members of the panel were men and 13 were women. Given that the panel (a) consisted of such small samples from each of the three age groups, (b) was probably sampled from a single geographic region, and (c) was sampled about 20 years ago, it is possible that the effective solutions endorsed by this particular panel are not entirely representative of those effective solutions that might be offered by individuals sampled today and who are living in different regions of the country. Future research should examine the metric properties of the EPSI to see if the effective solutions reported by the earlier panel (Cornelius & Caspi) are consistent with those endorsed by a more current sample of everyday problem solvers.

If we examine the effectiveness scores by using the six original EPSI domains, the results replicate those of Cornelius and Caspi (1987) . Older adults were more effective than younger adults in the consumer (young adults, M = 0.20, SE = 0.04; old adults, M = 0.36, SE = 0.04), t (104) = 2.80 ( p <.01), home (young adults, M = 0.37, SE = 0.04; old adults, M = 0.45, SE = 0.03), t (104) = 1.75 ( p <.05, one-tail), information (young adults, M = 0.61, SE = 0.03; old adults, M = 0.66, SE = 0.03), t (104) = 1.32 ( p <.10, one-tail), and work (young adults, M = 0.53, SE = 0.04; old adults, M = 0.61, SE = 0.03), t (104) = 1.69 ( p <.05, one-tail), domains.

Decision Editor: Thomas M. Hess, PhD

Problem Solving Strategies Included in the Everyday Problem Solving Inventory.

Mean Strategy Endorsement and Problem-Solving Effectiveness Ratings by Age and Domain.

Notes : Strategy endorsement ratings ranged from 1 (definitely would not do) to 5 (definitely would do). Problem-solving effectiveness scores ranged from r = −1.0 to r = 1.0. Parenthetical material represents the extreme ends of the strategy endorsement ratings. ADE = Avoidance–denial, PD = passive dependence, PPS = planful problem solving, and CA = cognitive analysis.

EPSI Problems Used in the Current Study.

This research was supported by the National Institute on Aging under Research Grant AG-11715, awarded to Fredda Blanchard-Fields.

Artistico, D., Cervone, D., Pezzuti, L. ( 2003 ). Perceived self-efficacy and everyday problem-solving among young and older adults. Psychology and Aging , 18 , 68 -79.

Berg, C. A., Strough, J., Calderone, K. S., Sansone, C., Weir, C. ( 1998 ). The role of problem definitions in understanding age and context effects on strategies for solving everyday problems. Psychology and Aging , 13 , 29 -44.

Blanchard-Fields, F., Chen, Y., Norris, L. ( 1997 ). Everyday problem solving across the adult life span: Influence of domain specificity and cognitive appraisal. Psychology and Aging , 12 , 684 -693.

Blanchard-Fields, F., Jahnke, H., Camp, C. ( 1995 ). Age differences in problem-solving style: The role of emotional salience. Psychology and Aging , 10 , 173 -180.

Blanchard-Fields, F., Stein, R., Watson, T. L. ( 2004 ). Age differences in emotion-regulation strategies in handling everyday problems. Journals of Gerontology: Psychological and Social Sciences , 59B , P261 -P269.

Consedine, N., Magai, C., Bonanno, G. ( 2002 ). Moderators of the emotion inhibition-health relationship: A review and research agenda. Review of General Psychology , 6 , 204 -228.

Cornelius, S. W., Caspi, A. ( 1987 ). Everyday problem solving in adulthood and old age. Psychology and Aging , 2 , 144 -153.

Marsiske, M., Willis, S. L. ( 1995 ). Dimensionality of everyday problem solving in older adults. Psychology and Aging , 10 , 269 -283.

Strough, J., Berg, C. A., Sansone, C. ( 1996 ). Goals for solving everyday problems across the life span: Age and gender differences in the salience of interpersonal concerns. Developmental Psychology , 32 , 1106 -1115.

Thornton, W. J. L., Dumke, H. A. ( 2005 ). Age differences in everyday problem-solving and decision-making effectiveness: A meta-analytic review. Psychology and Aging , 20 , 85 -99.

Watson, T. L., Blanchard-Fields, F. ( 1998 ). Thinking with your head and your heart: Age differences in everyday problem-solving strategy preferences. Aging, Neuropsychology, and Cognition , 5 , 225 -240.

Zacks, R. T., Hasher, L., Li, K. Z. H. ( 2000 ). Human memory. In T. A. Salthouse & F. I. M. Craik (Eds.), Handbook of aging and cognition (2nd ed., pp. 293–357). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Email alerts

Citing articles via, looking for your next opportunity.

- Recommend to Your Librarian

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1758-5368

- Copyright © 2024 The Gerontological Society of America

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

Insight Learning Theory: Definition, Stages, and Examples

Categories Learning

Insight learning theory is all about those “lightbulb moments” we experience when we suddenly understand something. Instead of slowly figuring things out through trial and error, insight theory says we can suddenly see the solution to a problem in our minds.

This theory is super important because it helps us understand how our brains work when we learn and solve problems. It can help teachers find better ways to teach and improve our problem-solving skills and creativity. It’s not just useful in school—insight theory also greatly impacts science, technology, and business.

Table of Contents

What Is Insight Learning?

Insight learning is like having a lightbulb moment in your brain. It’s when you suddenly understand something without needing to go through a step-by-step process. Instead of slowly figuring things out by trial and error, insight learning happens in a flash. One moment, you’re stuck, and the next, you have the solution.

This type of learning is all about those “aha” experiences that feel like magic. The key principles of insight learning involve recognizing patterns, making connections, and restructuring our thoughts. It’s as if our brains suddenly rearrange the pieces of a puzzle, revealing the big picture. So, next time you have a brilliant idea pop into your head out of nowhere, you might just be experiencing insight learning in action!

Three Components of Insight Learning Theory

Insight learning, a concept rooted in psychology, comprises three distinct properties that characterize its unique nature:

1. Sudden Realization

Unlike gradual problem-solving methods, insight learning involves sudden and profound understanding. Individuals may be stuck on a problem for a while, but then, seemingly out of nowhere, the solution becomes clear. This sudden “aha” moment marks the culmination of mental processes that have been working behind the scenes to reorganize information and generate a new perspective .

2. Restructuring of Problem-Solving Strategies

Insight learning often involves a restructuring of mental representations or problem-solving strategies . Instead of simply trying different approaches until stumbling upon the correct one, individuals experience a shift in how they perceive and approach the problem. This restructuring allows for a more efficient and direct path to the solution once insight occurs.

3. Aha Moments

A hallmark of insight learning is the experience of “aha” moments. These moments are characterized by a sudden sense of clarity and understanding, often accompanied by a feeling of satisfaction or excitement. It’s as if a mental lightbulb turns on, illuminating the solution to a previously perplexing problem.

These moments of insight can be deeply rewarding and serve as powerful motivators for further learning and problem-solving endeavors.

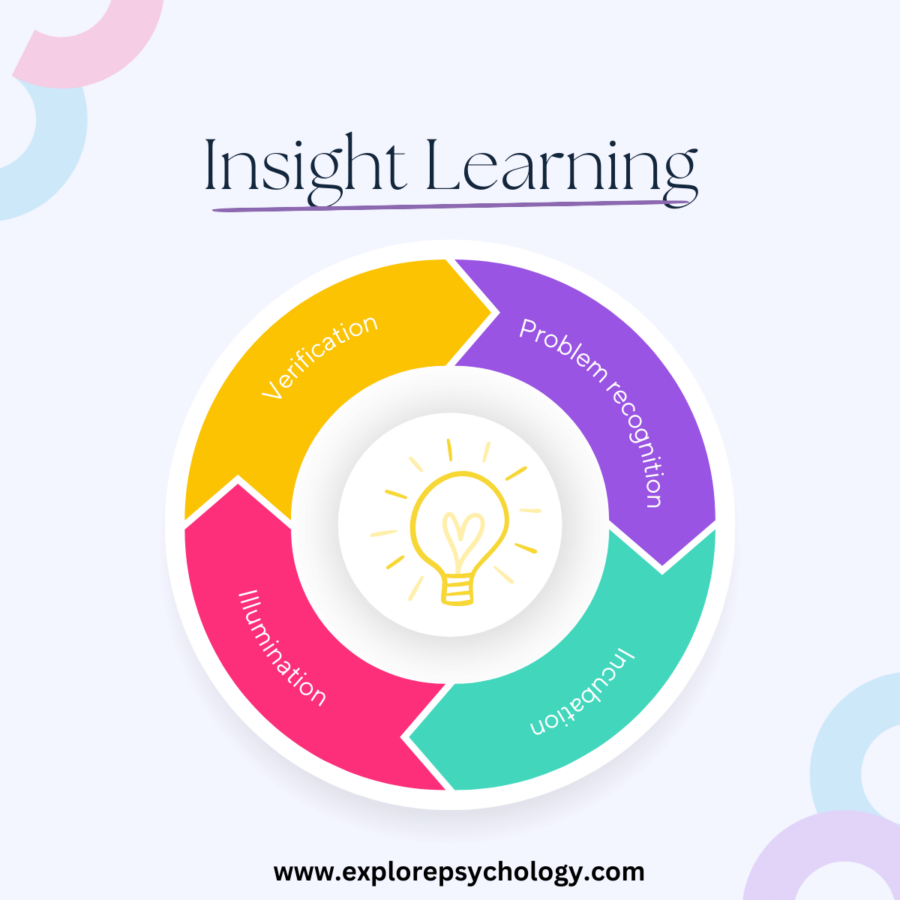

Four Stages of Insight Learning Theory

Insight learning unfolds in a series of distinct stages, each contributing to the journey from problem recognition to the sudden realization of a solution. These stages are as follows:

1. Problem Recognition

The first stage of insight learning involves recognizing and defining the problem at hand. This may entail identifying obstacles, discrepancies, or gaps in understanding that need to be addressed. Problem recognition sets the stage for the subsequent stages of insight learning by framing the problem and guiding the individual’s cognitive processes toward finding a solution.

2. Incubation

After recognizing the problem, individuals often enter a period of incubation where the mind continues to work on the problem unconsciously. During this stage, the brain engages in background processing, making connections, and reorganizing information without the individual’s conscious awareness.

While it may seem like a period of inactivity on the surface, incubation is a crucial phase where ideas gestate, and creative solutions take shape beneath the surface of conscious thought.

3. Illumination

The illumination stage marks the sudden emergence of insight or understanding. It is characterized by a moment of clarity and realization, where the solution to the problem becomes apparent in a flash of insight.

This “aha” moment often feels spontaneous and surprising, as if the solution has been waiting just below the surface of conscious awareness to be revealed. Illumination is the culmination of the cognitive processes initiated during problem recognition and incubation, resulting in a breakthrough in understanding.

4. Verification

Following the illumination stage, individuals verify the validity and feasibility of their insights by testing the proposed solution. This may involve applying the solution in practice, checking it against existing knowledge or expertise, or seeking feedback from others.

Verification serves to confirm the efficacy of the newfound understanding and ensure its practical applicability in solving the problem at hand. It also provides an opportunity to refine and iterate on the solution based on real-world feedback and experience.

Famous Examples of Insight Learning

Examples of insight learning can be observed in various contexts, ranging from everyday problem-solving to scientific discoveries and creative breakthroughs. Some well-known examples of how insight learning theory works include the following:

Archimedes’ Principle

According to legend, the ancient Greek mathematician Archimedes experienced a moment of insight while taking a bath. He noticed that the water level rose as he immersed his body, leading him to realize that the volume of water displaced was equal to the volume of the submerged object. This insight led to the formulation of Archimedes’ principle, a fundamental concept in fluid mechanics.

Köhler’s Chimpanzee Experiments

In Wolfgang Köhler’s experiments with chimpanzees on Tenerife in the 1920s, the primates demonstrated insight learning in solving novel problems. One famous example involved a chimpanzee named Sultan, who used sticks to reach bananas placed outside his cage. After unsuccessful attempts at using a single stick, Sultan suddenly combined two sticks to create a longer tool, demonstrating insight into the problem and the ability to use tools creatively.

Eureka Moments in Science

Many scientific discoveries are the result of insight learning. For instance, the famed naturalist Charles Darwin had many eureka moments where he gained sudden insights that led to the formation of his influential theories.

Everyday Examples of Insight Learning Theory

You can probably think of some good examples of the role that insight learning theory plays in your everyday life. A few common real-life examples include:

- Finding a lost item : You might spend a lot of time searching for a lost item, like your keys or phone, but suddenly remember exactly where you left them when you’re doing something completely unrelated. This sudden recollection is an example of insight learning.

- Untangling knots : When trying to untangle a particularly tricky knot, you might struggle with it for a while without making progress. Then, suddenly, you realize a new approach or see a pattern that helps you quickly unravel the knot.

- Cooking improvisation : If you’re cooking and run out of a particular ingredient, you might suddenly come up with a creative substitution or alteration to the recipe that works surprisingly well. This moment of improvisation demonstrates insight learning in action.

- Solving riddles or brain teasers : You might initially be stumped when trying to solve a riddle or a brain teaser. However, after some time pondering the problem, you suddenly grasp the solution in a moment of insight.

- Learning a new skill : Learning to ride a bike or play a musical instrument often involves moments of insight. You might struggle with a certain technique or concept but then suddenly “get it” and experience a significant improvement in your performance.

- Navigating a maze : While navigating through a maze, you might encounter dead ends and wrong turns. However, after some exploration, you suddenly realize the correct path to take and reach the exit efficiently.

- Remembering information : When studying for a test, you might find yourself unable to recall a particular piece of information. Then, when you least expect it, the answer suddenly comes to you in a moment of insight.

These everyday examples illustrate how insight learning is a common and natural part of problem-solving and learning in our daily lives.

Exploring the Uses of Insight Learning

Insight learning isn’t an interesting explanation for how we suddenly come up with a solution to a problem—it also has many practical applications. Here are just a few ways that people can use insight learning in real life:

Problem-Solving

Insight learning helps us solve all sorts of problems, from finding lost items to untangling knots. When we’re stuck, our brains might suddenly come up with a genius idea or a new approach that saves the day. It’s like having a mental superhero swoop in to rescue us when we least expect it!

Ever had a brilliant idea pop into your head out of nowhere? That’s insight learning at work! Whether you’re writing a story, composing music, or designing something new, insight can spark creativity and help you come up with fresh, innovative ideas.

Learning New Skills

Learning isn’t always about memorizing facts or following step-by-step instructions. Sometimes, it’s about having those “aha” moments that make everything click into place. Insight learning can help us grasp tricky concepts, master difficult skills, and become better learners overall.

Insight learning isn’t just for individuals—it’s also crucial for innovation and progress in society. Scientists, inventors, and entrepreneurs rely on insight to make groundbreaking discoveries and develop new technologies that improve our lives. Who knows? The next big invention could start with someone having a brilliant idea in the shower!

Overcoming Challenges

Life is full of challenges, but insight learning can help us tackle them with confidence. Whether it’s navigating a maze, solving a puzzle, or facing a tough decision, insight can provide the clarity and creativity we need to overcome obstacles and achieve our goals.

The next time you’re feeling stuck or uninspired, remember: the solution might be just one “aha” moment away!

Alternatives to Insight Learning Theory

While insight learning theory emphasizes sudden understanding and restructuring of problem-solving strategies, several alternative theories offer different perspectives on how learning and problem-solving occur. Here are some of the key alternative theories:

Behaviorism

Behaviorism is a theory that focuses on observable, overt behaviors and the external factors that influence them. According to behaviorists like B.F. Skinner, learning is a result of conditioning, where behaviors are reinforced or punished based on their consequences.

In contrast to insight learning theory, behaviorism suggests that learning occurs gradually through repeated associations between stimuli and responses rather than sudden insights or realizations.

Cognitive Learning Theory

Cognitive learning theory, influenced by psychologists such as Jean Piaget and Lev Vygotsky , emphasizes the role of mental processes in learning. This theory suggests that individuals actively construct knowledge and understanding through processes like perception, memory, and problem-solving.

Cognitive learning theory acknowledges the importance of insight and problem-solving strategies but places greater emphasis on cognitive structures and processes underlying learning.

Gestalt Psychology

Gestalt psychology, which influenced insight learning theory, proposes that learning and problem-solving involve the organization of perceptions into meaningful wholes or “gestalts.”

Gestalt psychologists like Max Wertheimer emphasized the role of insight and restructuring in problem-solving, but their theories also consider other factors, such as perceptual organization, pattern recognition, and the influence of context.

Information Processing Theory

Information processing theory views the mind as a computer-like system that processes information through various stages, including input, processing, storage, and output. This theory emphasizes the role of attention, memory, and problem-solving strategies in learning and problem-solving.

While insight learning theory focuses on sudden insights and restructuring, information processing theory considers how individuals encode, manipulate, and retrieve information to solve problems.

Kizilirmak, J. M., Fischer, L., Krause, J., Soch, J., Richter, A., & Schott, B. H. (2021). Learning by insight-like sudden comprehension as a potential strategy to improve memory encoding in older adults . Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience , 13 , 661346. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnagi.2021.661346

Lind, J., Enquist, M. (2012). Insight learning and shaping . In: Seel, N.M. (eds) Encyclopedia of the Sciences of Learning . Springer, Boston, MA. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-1428-6_851

Osuna-Mascaró, A. J., & Auersperg, A. M. I. (2021). Current understanding of the “insight” phenomenon across disciplines . Frontiers in Psychology , 12, 791398. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.791398

Salmon-Mordekovich, N., & Leikin, M. (2023). Insight problem solving is not that special, but business is not quite ‘as usual’: typical versus exceptional problem-solving strategies . Psychological Research , 87 (6), 1995–2009. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00426-022-01786-5

10 Best Problem-Solving Therapy Worksheets & Activities

Cognitive science tells us that we regularly face not only well-defined problems but, importantly, many that are ill defined (Eysenck & Keane, 2015).

Sometimes, we find ourselves unable to overcome our daily problems or the inevitable (though hopefully infrequent) life traumas we face.

Problem-Solving Therapy aims to reduce the incidence and impact of mental health disorders and improve wellbeing by helping clients face life’s difficulties (Dobson, 2011).

This article introduces Problem-Solving Therapy and offers techniques, activities, and worksheets that mental health professionals can use with clients.

Before you continue, we thought you might like to download our three Positive Psychology Exercises for free . These science-based exercises explore fundamental aspects of positive psychology, including strengths, values, and self-compassion, and will give you the tools to enhance the wellbeing of your clients, students, or employees.

This Article Contains:

What is problem-solving therapy, 14 steps for problem-solving therapy, 3 best interventions and techniques, 7 activities and worksheets for your session, fascinating books on the topic, resources from positivepsychology.com, a take-home message.

Problem-Solving Therapy assumes that mental disorders arise in response to ineffective or maladaptive coping. By adopting a more realistic and optimistic view of coping, individuals can understand the role of emotions and develop actions to reduce distress and maintain mental wellbeing (Nezu & Nezu, 2009).

“Problem-solving therapy (PST) is a psychosocial intervention, generally considered to be under a cognitive-behavioral umbrella” (Nezu, Nezu, & D’Zurilla, 2013, p. ix). It aims to encourage the client to cope better with day-to-day problems and traumatic events and reduce their impact on mental and physical wellbeing.

Clinical research, counseling, and health psychology have shown PST to be highly effective in clients of all ages, ranging from children to the elderly, across multiple clinical settings, including schizophrenia, stress, and anxiety disorders (Dobson, 2011).

Can it help with depression?

PST appears particularly helpful in treating clients with depression. A recent analysis of 30 studies found that PST was an effective treatment with a similar degree of success as other successful therapies targeting depression (Cuijpers, Wit, Kleiboer, Karyotaki, & Ebert, 2020).

Other studies confirm the value of PST and its effectiveness at treating depression in multiple age groups and its capacity to combine with other therapies, including drug treatments (Dobson, 2011).

The major concepts

Effective coping varies depending on the situation, and treatment typically focuses on improving the environment and reducing emotional distress (Dobson, 2011).

PST is based on two overlapping models:

Social problem-solving model

This model focuses on solving the problem “as it occurs in the natural social environment,” combined with a general coping strategy and a method of self-control (Dobson, 2011, p. 198).

The model includes three central concepts:

- Social problem-solving

- The problem

- The solution

The model is a “self-directed cognitive-behavioral process by which an individual, couple, or group attempts to identify or discover effective solutions for specific problems encountered in everyday living” (Dobson, 2011, p. 199).

Relational problem-solving model

The theory of PST is underpinned by a relational problem-solving model, whereby stress is viewed in terms of the relationships between three factors:

- Stressful life events

- Emotional distress and wellbeing

- Problem-solving coping

Therefore, when a significant adverse life event occurs, it may require “sweeping readjustments in a person’s life” (Dobson, 2011, p. 202).

- Enhance positive problem orientation

- Decrease negative orientation

- Foster ability to apply rational problem-solving skills

- Reduce the tendency to avoid problem-solving

- Minimize the tendency to be careless and impulsive

D’Zurilla’s and Nezu’s model includes (modified from Dobson, 2011):

- Initial structuring Establish a positive therapeutic relationship that encourages optimism and explains the PST approach.

- Assessment Formally and informally assess areas of stress in the client’s life and their problem-solving strengths and weaknesses.

- Obstacles to effective problem-solving Explore typically human challenges to problem-solving, such as multitasking and the negative impact of stress. Introduce tools that can help, such as making lists, visualization, and breaking complex problems down.

- Problem orientation – fostering self-efficacy Introduce the importance of a positive problem orientation, adopting tools, such as visualization, to promote self-efficacy.

- Problem orientation – recognizing problems Help clients recognize issues as they occur and use problem checklists to ‘normalize’ the experience.

- Problem orientation – seeing problems as challenges Encourage clients to break free of harmful and restricted ways of thinking while learning how to argue from another point of view.

- Problem orientation – use and control emotions Help clients understand the role of emotions in problem-solving, including using feelings to inform the process and managing disruptive emotions (such as cognitive reframing and relaxation exercises).

- Problem orientation – stop and think Teach clients how to reduce impulsive and avoidance tendencies (visualizing a stop sign or traffic light).

- Problem definition and formulation Encourage an understanding of the nature of problems and set realistic goals and objectives.

- Generation of alternatives Work with clients to help them recognize the wide range of potential solutions to each problem (for example, brainstorming).

- Decision-making Encourage better decision-making through an improved understanding of the consequences of decisions and the value and likelihood of different outcomes.

- Solution implementation and verification Foster the client’s ability to carry out a solution plan, monitor its outcome, evaluate its effectiveness, and use self-reinforcement to increase the chance of success.

- Guided practice Encourage the application of problem-solving skills across multiple domains and future stressful problems.

- Rapid problem-solving Teach clients how to apply problem-solving questions and guidelines quickly in any given situation.

Success in PST depends on the effectiveness of its implementation; using the right approach is crucial (Dobson, 2011).

Problem-solving therapy – Baycrest

The following interventions and techniques are helpful when implementing more effective problem-solving approaches in client’s lives.

First, it is essential to consider if PST is the best approach for the client, based on the problems they present.

Is PPT appropriate?

It is vital to consider whether PST is appropriate for the client’s situation. Therapists new to the approach may require additional guidance (Nezu et al., 2013).

Therapists should consider the following questions before beginning PST with a client (modified from Nezu et al., 2013):

- Has PST proven effective in the past for the problem? For example, research has shown success with depression, generalized anxiety, back pain, Alzheimer’s disease, cancer, and supporting caregivers (Nezu et al., 2013).

- Is PST acceptable to the client?

- Is the individual experiencing a significant mental or physical health problem?

All affirmative answers suggest that PST would be a helpful technique to apply in this instance.

Five problem-solving steps

The following five steps are valuable when working with clients to help them cope with and manage their environment (modified from Dobson, 2011).

Ask the client to consider the following points (forming the acronym ADAPT) when confronted by a problem:

- Attitude Aim to adopt a positive, optimistic attitude to the problem and problem-solving process.

- Define Obtain all required facts and details of potential obstacles to define the problem.

- Alternatives Identify various alternative solutions and actions to overcome the obstacle and achieve the problem-solving goal.

- Predict Predict each alternative’s positive and negative outcomes and choose the one most likely to achieve the goal and maximize the benefits.

- Try out Once selected, try out the solution and monitor its effectiveness while engaging in self-reinforcement.

If the client is not satisfied with their solution, they can return to step ‘A’ and find a more appropriate solution.

Download 3 Free Positive Psychology Exercises (PDF)

Enhance wellbeing with these free, science-based exercises that draw on the latest insights from positive psychology.

Download 3 Free Positive Psychology Tools Pack (PDF)

By filling out your name and email address below.

Positive self-statements

When dealing with clients facing negative self-beliefs, it can be helpful for them to use positive self-statements.

Use the following (or add new) self-statements to replace harmful, negative thinking (modified from Dobson, 2011):

- I can solve this problem; I’ve tackled similar ones before.

- I can cope with this.

- I just need to take a breath and relax.

- Once I start, it will be easier.

- It’s okay to look out for myself.

- I can get help if needed.

- Other people feel the same way I do.

- I’ll take one piece of the problem at a time.

- I can keep my fears in check.

- I don’t need to please everyone.

5 Worksheets and workbooks

Problem-solving self-monitoring form.

Answering the questions in the Problem-Solving Self-Monitoring Form provides the therapist with necessary information regarding the client’s overall and specific problem-solving approaches and reactions (Dobson, 2011).

Ask the client to complete the following:

- Describe the problem you are facing.

- What is your goal?

- What have you tried so far to solve the problem?

- What was the outcome?

Reactions to Stress

It can be helpful for the client to recognize their own experiences of stress. Do they react angrily, withdraw, or give up (Dobson, 2011)?

The Reactions to Stress worksheet can be given to the client as homework to capture stressful events and their reactions. By recording how they felt, behaved, and thought, they can recognize repeating patterns.

What Are Your Unique Triggers?

Helping clients capture triggers for their stressful reactions can encourage emotional regulation.

When clients can identify triggers that may lead to a negative response, they can stop the experience or slow down their emotional reaction (Dobson, 2011).

The What Are Your Unique Triggers ? worksheet helps the client identify their triggers (e.g., conflict, relationships, physical environment, etc.).

Problem-Solving worksheet

Imagining an existing or potential problem and working through how to resolve it can be a powerful exercise for the client.

Use the Problem-Solving worksheet to state a problem and goal and consider the obstacles in the way. Then explore options for achieving the goal, along with their pros and cons, to assess the best action plan.

Getting the Facts

Clients can become better equipped to tackle problems and choose the right course of action by recognizing facts versus assumptions and gathering all the necessary information (Dobson, 2011).

Use the Getting the Facts worksheet to answer the following questions clearly and unambiguously:

- Who is involved?

- What did or did not happen, and how did it bother you?

- Where did it happen?

- When did it happen?

- Why did it happen?

- How did you respond?

2 Helpful Group Activities

While therapists can use the worksheets above in group situations, the following two interventions work particularly well with more than one person.

Generating Alternative Solutions and Better Decision-Making

A group setting can provide an ideal opportunity to share a problem and identify potential solutions arising from multiple perspectives.

Use the Generating Alternative Solutions and Better Decision-Making worksheet and ask the client to explain the situation or problem to the group and the obstacles in the way.

Once the approaches are captured and reviewed, the individual can share their decision-making process with the group if they want further feedback.

Visualization

Visualization can be performed with individuals or in a group setting to help clients solve problems in multiple ways, including (Dobson, 2011):

- Clarifying the problem by looking at it from multiple perspectives

- Rehearsing a solution in the mind to improve and get more practice

- Visualizing a ‘safe place’ for relaxation, slowing down, and stress management

Guided imagery is particularly valuable for encouraging the group to take a ‘mental vacation’ and let go of stress.

Ask the group to begin with slow, deep breathing that fills the entire diaphragm. Then ask them to visualize a favorite scene (real or imagined) that makes them feel relaxed, perhaps beside a gently flowing river, a summer meadow, or at the beach.

The more the senses are engaged, the more real the experience. Ask the group to think about what they can hear, see, touch, smell, and even taste.

Encourage them to experience the situation as fully as possible, immersing themselves and enjoying their place of safety.

Such feelings of relaxation may be able to help clients fall asleep, relieve stress, and become more ready to solve problems.

We have included three of our favorite books on the subject of Problem-Solving Therapy below.

1. Problem-Solving Therapy: A Treatment Manual – Arthur Nezu, Christine Maguth Nezu, and Thomas D’Zurilla

This is an incredibly valuable book for anyone wishing to understand the principles and practice behind PST.

Written by the co-developers of PST, the manual provides powerful toolkits to overcome cognitive overload, emotional dysregulation, and the barriers to practical problem-solving.

Find the book on Amazon .

2. Emotion-Centered Problem-Solving Therapy: Treatment Guidelines – Arthur Nezu and Christine Maguth Nezu

Another, more recent, book from the creators of PST, this text includes important advances in neuroscience underpinning the role of emotion in behavioral treatment.

Along with clinical examples, the book also includes crucial toolkits that form part of a stepped model for the application of PST.

3. Handbook of Cognitive-Behavioral Therapies – Keith Dobson and David Dozois

This is the fourth edition of a hugely popular guide to Cognitive-Behavioral Therapies and includes a valuable and insightful section on Problem-Solving Therapy.

This is an important book for students and more experienced therapists wishing to form a high-level and in-depth understanding of the tools and techniques available to Cognitive-Behavioral Therapists.

For even more tools to help strengthen your clients’ problem-solving skills, check out the following free worksheets from our blog.

- Case Formulation Worksheet This worksheet presents a four-step framework to help therapists and their clients come to a shared understanding of the client’s presenting problem.

- Understanding Your Default Problem-Solving Approach This worksheet poses a series of questions helping clients reflect on their typical cognitive, emotional, and behavioral responses to problems.

- Social Problem Solving: Step by Step This worksheet presents a streamlined template to help clients define a problem, generate possible courses of action, and evaluate the effectiveness of an implemented solution.

If you’re looking for more science-based ways to help others enhance their wellbeing, check out this signature collection of 17 validated positive psychology tools for practitioners. Use them to help others flourish and thrive.

17 Top-Rated Positive Psychology Exercises for Practitioners

Expand your arsenal and impact with these 17 Positive Psychology Exercises [PDF] , scientifically designed to promote human flourishing, meaning, and wellbeing.

Created by Experts. 100% Science-based.

While we are born problem-solvers, facing an incredibly diverse set of challenges daily, we sometimes need support.

Problem-Solving Therapy aims to reduce stress and associated mental health disorders and improve wellbeing by improving our ability to cope. PST is valuable in diverse clinical settings, ranging from depression to schizophrenia, with research suggesting it as a highly effective treatment for teaching coping strategies and reducing emotional distress.