Capital structure of SMEs: a systematic literature review and bibliometric analysis

Satish Kumar , R. Sureka , Sisira R. N. Colombage

Nov 13, 2019

Influential Citations

Quality indicators

Management Review Quarterly

Key takeaway

Capital structure of smes is influenced by market conditions, financial decisions, and credit rationing, with theory testing being a major focus..

Capital structure is the outcome of market conditions, financial decisions taken by the firm, and credit rationing of fund providers. Research on the capital structure of small and medium enterprises (SMEs) has gained momentum in recent years. The present study aims to identify key contributors, key areas, current dynamics, and suggests future research directions in the field of the capital structure of SMEs. This paper adopts a systematic literature review methodology along with bibliometric, network, and content analysis on a sample of 262 studies taken from the Web of Science database to examine the research activities that have taken place on this topic. Most influential papers are identified based on citations and PageRank, along with the most influential authors. The co-citation network is developed to see the intellectual structure of this research area. Applying bibliometric tools, four research clusters have been identified and content analysis performed on the papers identified in the clusters. It is found that the major research focus in this area is around theory testing—mainly, pecking order theory, trade-off theory, and agency theory. Determinants of capital structure, trade credit, corporate governance, and bankruptcy are also the prominent research topics in this field. Also, this study has identified the research gaps and has proposed five actionable research directions for the future.

Capital structure of SMEs: a systematic literature review and bibliometric analysis

- Scinapse’s Top 10 Citation Journals & Affiliations graph reveals the quality and authenticity of citations received by a paper.

- Discover whether citations have been inflated due to self-citations, or if citations include institutional bias.

Browse Econ Literature

- Working papers

- Software components

- Book chapters

- JEL classification

More features

- Subscribe to new research

RePEc Biblio

Author registration.

- Economics Virtual Seminar Calendar NEW!

Capital structure of SMEs: a systematic literature review and bibliometric analysis

- Author & abstract

- 80 References

- 36 Citations

- Most related

- Related works & more

Corrections

(Malaviya National Institute of Technology)

(Federation University Australia)

- Satish Kumar

Suggested Citation

Download full text from publisher, references listed on ideas.

Follow serials, authors, keywords & more

Public profiles for Economics researchers

Various research rankings in Economics

RePEc Genealogy

Who was a student of whom, using RePEc

Curated articles & papers on economics topics

Upload your paper to be listed on RePEc and IDEAS

New papers by email

Subscribe to new additions to RePEc

EconAcademics

Blog aggregator for economics research

Cases of plagiarism in Economics

About RePEc

Initiative for open bibliographies in Economics

News about RePEc

Questions about IDEAS and RePEc

RePEc volunteers

Participating archives

Publishers indexing in RePEc

Privacy statement

Found an error or omission?

Opportunities to help RePEc

Get papers listed

Have your research listed on RePEc

Open a RePEc archive

Have your institution's/publisher's output listed on RePEc

Get RePEc data

Use data assembled by RePEc

Capital structure determinants of small and medium-sized enterprises: evidence from Central and Eastern Europe

Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development

ISSN : 1462-6004

Article publication date: 16 February 2021

Issue publication date: 17 March 2021

The main aim of the paper is to examine the small and medium-sized enterprises’ (SMEs) capital structure determinants in Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) (Poland, Czechia, Slovakia, Hungary, Bulgaria and Romania).

Design/methodology/approach

The authors used panel models to analyze financial data of 15,253 companies operating in the years 2014–2017.

The authors confirmed the dominant role of firm-specific factors. Industry and country variables explain only 4% of debt variability of the surveyed companies. The direction of influence of the diagnosed firm-specific factors is consistent with the pecking order theory. About one-fourth of SMEs in CEE hold a stock of debt capacity. It negatively affects the share of debt in the capital. The authors did not confirm the influence of the systematic industry business risk.

Research limitations/implications

The limitations of the study are (1) the inclusion of only six CEE countries in the sample; (2) the exclusion of microenterprises from the sample; (3) the capital structure relationships are observed following the applications of static panel; (4) the endogeneity issue has not been addressed in the model.

Practical implications

This study shows that business-friendly institutional environment is an important factor influencing the indebtedness of companies. It increases the leverage and, consequently, the return on equity, especially in CEE countries.

Originality/value

SME analyses in CEE countries are not as frequent as for other regions. Despite the classical determinants of the SMEs' capital structure, the authors have included debt capacity and systematic industry business risk in this study.

- Capital structure determinants

- Capital structure theories

- Small and medium-sized enterprises

- Central and Eastern Europe

Czerwonka, L. and Jaworski, J. (2021), "Capital structure determinants of small and medium-sized enterprises: evidence from Central and Eastern Europe", Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development , Vol. 28 No. 2, pp. 277-297. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSBED-09-2020-0326

Emerald Publishing Limited

Copyright © 2021, Leszek Czerwonka and Jacek Jaworski

Published by Emerald Publishing Limited. This article is published under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) licence. Anyone may reproduce, distribute, translate and create derivative works of this article (for both commercial and non-commercial purposes), subject to full attribution to the original publication and authors. The full terms of this licence may be seen at http://creativecommons.org/licences/by/4.0/legalcode .

1. Introduction

The most numerous as well as the most significant group of economic entities in the European Union (EU) is the small and medium-sized enterprise (SME) sector. In 2015, it comprised 99.8% of all 23.5 m businesses in the EU. It generated 55.8% of turnover and employed 66.3% of workers in the business sector ( Eurostat, 2015 ). While highlighting the role of this sector in the European economy, one cannot ignore the main barrier to its development, namely the difficulty of accessing sources of finance ( Beck and Demirguc-Kunt, 2006 ; European Commission, 2007 ; Beck et al. , 2008 ; Palacín-Sánchez et al. , 2013 ; European Central Bank, 2014 ; Kumar and Rao, 2015 ; Baños-Caballero et al. , 2016 ; Kersten et al. , 2017 ). That is why the research on the SMEs' capital structure is particularly important.

Research on the capital structure of enterprises has been going on for over half of a century. It also concerns SMEs. For this sector, the following two main capital structure theories are prevalent in the literature ( Martinez et al. , 2019 ): (1) the trade-off theory ( Baxter, 1967 ; Kraus and Litzenberger, 1973 ; Scott, 1976 ; Kim, 1978 ) and (2) the pecking order theory ( Myers, 1984 ; Myers and Majluf, 1984 ). There are many empirical studies showing that companies' decisions are influenced by a number of factors. These factors can be classified into three basic groups ( Hall et al. , 2004 ; Psillaki and Dasaklakis, 2009 ; Jõeveer, 2013 ; Moritz et al. , 2016 ; Kenourgios et al. , 2019 ): firm, industry and country-specific factors.

The structure of SME capital in the “old” EU countries is often examined ( Hall et al. , 2000 ; Sánchez-Vidal and Martín-Ugedo, 2005 ; López-Gracia and Sogorb-Mira, 2008 ; Aybar-Arias et al. , 2012 ; Baños-Caballero et al. , 2012 ; Jõeveer, 2013 ; Palacín-Sánchez et al. , 2013 ; Ughetto et al. , 2017 ). However, in the EU, a group of countries with a short market economy tradition (Central and Eastern Europe – CEE) adopted to the EU after 2004 can be distinguished. Although the SME sector plays a similar role within them, the conditions for its management differ significantly from the mature economies of Western Europe. Research on the SMEs' capital structure in CEE markets does not have a long tradition and is not as developed as in Western Europe ( Mateev et al. , 2013 ; Harc, 2015 ; Belas et al. , 2018 ; Kenourgios et al. , 2019 ). This assumption is supported by literature review conducted by Martinez et al. (2019) . Searching for an answer to the question which theory of SME capital structure is reflected in empirical research, the authors made a systematic review based on 3,549 studies distributed in the years 1959–2017. One research gap found concerned the lack of studies related to emerging economies. The other literature review conducted by Kumar et al. (2020) including 262 articles published in the years 2012–2017 proved that one of the most prevalent topic in the literature concerns determinants of SME capital structure. At the same time, the authors indicated that it would be worth extending this research to other determinants, not covered by studies carried out so far.

The main aim of the paper is to examine the SMEs' capital structure determinants in CEE countries. In addition to the frequently investigated determinants, our study also included additional factors: debt capacity and systematic industry business risk. The study covered six countries: Poland, Czechia, Slovakia, Hungary, Bulgaria and Romania.

The results of our study complement and strengthen some of the findings to date. We confirmed SMEs' debt being mainly determined by firm-specific factors. However, the impact of factors at the industry and country level is more than twice as weak in CEE as in more developed economies. We demonstrate that all classical firm-specific factors significantly affect the capital structure of SMEs. The direction of this impact is consistent with the pecking order theory. As in other economies, the indebtedness of companies in CEE depends significantly on the financial risk of a given industry. We show that the degree of friendliness of the legal and institutional business environment and access to credit in the private sector are institutional country-specific factors that significantly increase corporate indebtedness. Among the macroeconomic country-specific factors, the country's economic growth dynamics have a positive impact on debt, while the rising cost of debt has a negative impact.

Our research also brings new elements to the existing knowledge. We showed that more than one-fourth of SMEs in CEE maintained a stock of debt capacity throughout the entire research period. Membership of this group of companies was negatively correlated with the share of debt in capital. This behavior of SMEs is consistent with the pecking order theory. The study also shows that SMEs' indebtedness in CEE does not depend on systematic industry business risk. This result contradicted the previous findings regarding the sector of large companies.

The paper is structured as follows: the first part presents theories and determinants of enterprises' capital structure. It also outlines the current state of theoretical and empirical research related to firms' financing behavior in SME sector. On this basis, the research hypotheses have been developed and the studied variables have been specified. In the second part of the paper, methods applied in empirical study and collected research material are described. The results of the research and their embedding in the existing achievements are presented in the third part of the paper. The final section includes discussion on the results and conclusions of the research.

2. Theoretical and empirical background

There is a well-established opinion in the literature that SMEs have difficult access to external capital. This view is confirmed by numerous studies ( Beck and Demirguc-Kunt, 2006 ; Beck et al. , 2008 ; Palacín-Sánchez et al. , 2013 ; Kumar and Rao, 2015 ; Baños-Caballero et al. , 2016 ; Kersten et al. , 2017 ) as well as the opinion of entrepreneurs themselves ( European Commission, 2007 ; European Central Bank, 2014 ). The most common reasons for this are the following ( Brav, 2009 ): (1) high credit risk for financing projects with a small size and short lifespan, (2) lack of reliable financial information based on regular financial reports, (3) lack of sufficient credit collateral and (4) high business risk for SMEs. However, at the same time, the prior studies showed significantly higher growth rates of small companies compared to large companies ( Evans, 1987 ). This, in turn, determines a noticeably greater dynamics of capital demand and a wider use of self-financing ( Watson and Wilson, 2002 ; Brighi and Torluccio, 2010 ). Mac an Bhaird and Lucey (2010) also noted that the faster the SME sector developed, the more willing it was to use venture capital funds or business angels, i.e. various external forms of increasing equity. These observations form a premise for the diagnosis of specific conditions of the SMEs’ capital structure.

The beginning of research on the capital structure is the work of Modigliani and Miller (1958) . They demonstrated that in a perfect capital market, the cost of capital, and thus the market value of a company, is independent of the capital structure. This original theory was modified by introducing the adjustments resulting from market imperfections into the model. Criticism of these models led to several further concepts. As Martinez et al. (2019) and Kumar et al. (2020) showed, two of them are relevant for SME sector.

The trade-off theory is the first concept prevalent in the literature related to SMEs. According to its static version, when shaping their capital structure, companies compare the costs of financial distress and bankruptcy with the expected tax benefits associated with debt financing. Debt creates tax shields and acts as a discipline for managers by creating incentives to increase its share in capital. However, debt is also associated with the costs of servicing it, leading to financial difficulties and bankruptcy, which in turn create incentives to reduce the debt. This means that there is an optimal capital structure when these benefits and costs are equal ( Baxter, 1967 ; Kraus and Litzenberger, 1973 ; Scott, 1976 ; Kim, 1978 ). The dynamic version of trade-off theory is also well documented in the literature. It foresees that companies, either by getting indebted or repaying debts at a certain pace, adjust their capital structure to an optimum. This level of debt is associated with the determined minimum of adjustment costs function by a change in cost of financial distress, on the one hand, and by benefits from tax shield on the other hand ( Huang and Ritter, 2005 ; Leary and Roberts, 2005 ; Kayhan and Titman, 2007 ; Lemmon et al. , 2008 ).

The pecking order theory is the second concept referred to the literature. On basis of the theoretical arguments of an adverse selection, Myers (1984) and Myers and Majluf (1984) formulated the theory that the increase in the company's financing needs is met according to a certain hierarchy. As the first source, companies use the capital generated (retained earnings), then issue debt until the debt capacity is exhausted, then issue hybrid instruments and finally raise external equity. The model does not predict a target or optimal capital structure. Structure is a function of aggregated policies related to profitability creation, dividend payments and investment opportunities ( Klein et al. , 2002 ; Bharath et al. , 2009 ).

Prior research provides evidence that companies' financial decisions are determined by a number of economic and institutional factors, which can be divided into three groups ( Michaelas et al. , 1999 ; Hall et al. , 2000 , 2004 ; Psillaki and Dasaklakis, 2009 ; Frydenberg, 2011 ; Jõeveer, 2013 ; Kenourgios et al. , 2019 ): (1) firm-specific factors, (2) industry-specific factors and (3) determinants on country level (institutional and macroeconomic features of national economies). Michaelas et al. (1999) and Hall et al. (2000) conducted research on the same panel of 3,500 SMEs from the UK operating between 1988 and 1995. The study showed that the impact of firm-specific factors on debt varied from one industry to another. In another study, which concerned 4,000 SMEs from eight Western European countries (Belgium, Germany, Spain, Ireland, Italy, The Netherlands and the UK), Hall et al. (2004) showed that the direction and strength of the impact of the firm-specific factors also varied from country to country. Similarly, Psillaki and Dasaklakis (2009) examined 3,630 SMEs from economies of Greece, France, Italy and Portugal operating between 1997 and 2002. However, they came to slightly different conclusions than their predecessors. The study did not deny the existence of industrial and country-specific factors, but the strength of their impact in comparison with the firm-specific factors was assessed by Psillaki and Dasaklakis (2009) as low. The study of Kenourgios et al. (2019) included financial data of 1,120 listed SMEs from EU countries and the period 2005–2015. Authors find that the effect of firm-specific capital structure determinants does not differ significantly across size and country groups. At the country level, taxation is the most significant for all subgroups studied (core, periphery and new member of EU).

Jõeveer’s study (2013) is an extensive cross-sectional study of the capital structure of SMEs, which covers all levels of capital structure determinants affecting 481,627 SMEs from eight European countries (Germany, France, Italy, the United Kingdom, Belgium, Finland, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland) in the years 1995–2002. The author found that the smaller the companies, the greater the impact of country-specific factors on their structure which explained about 10% of the debt variability of the studied companies. At the same time, the study showed that the larger the company, the more important the industry-specific factors became.

Firm-specific factors play a dominant role in explaining the debt variability of SMEs, followed by factors at the country level, and the industry determinants exert the least influence.

Firm-specific factors are justified by the above described capital structure theories. A broad analysis of these theories was carried out, among others, by Harris and Raviv (1991) , Rajan and Zingales (1995) , Frank and Goyal (2009) . It allowed them to identify the most important factors and to determine the direction of their impact depending on the theoretical justification (see Table 9 ).

In the research of Michaelas et al. (1999) , Hall et al. (2000 , 2004) , growth, tangibility, size, age and profitability turned out to be significant firm-specific factors. The faster the company's growth, the greater the short-term debt. The other factors had the opposite effect on short-term debt. For long-term debt, a positive correlation was observed for tangibility and age. Profitability, growth and size did not exert a significant impact. In turn, Psillaki and Dasaklakis (2009) confirmed the strong positive impact of company size on total debt and negative on profitability. Similar relationships were established by Jõeveer (2013) . Moreover, the author identified a negative relationship between tangibility and debt. Kenourgios et al. (2019) detected positive impact of size and tangibility on the indebtedness of the listed SMEs. Opposite direction was found for profitability.

In addition to cross-sectional research, there are also a great number of empirical evidences focused on firm-specific factors accumulated in single economies. Table 1 lists some of them.

Tangibility, size, growth, profitability, liquidity and non-debt tax shields exert a significant impact on SMEs' capital structure.

Directions of the impact of firm-specific factors on SMEs' capital structure are consistent with the pecking order theory.

SMEs with a debt share in the capital structure below the threshold maintain a stock of debt capacity and do not increase their debt.

Research on industry-specific capital structure determinants in the SME sector most often focuses on showing differences in the impact of industry-specific factors. The identification of these factors was done, among others, by Mac an Bhaird and Lucey (2010) and Degryse et al. (2012) . Examining 299 Irish SMEs, Mac an Bhaird and Lucey (2010) noted significant differences in the indebtedness of different industries. These differences depended primarily on the amount of fixed assets in the industry. The higher the level, the less the problem of information asymmetry and the better the collateralization of the debt, and thus, the companies in the industry could become more indebted. In turn, on the basis of data from the Dutch SMEs operating between 2002 and 2005, Degryse et al. (2012) showed that the observed differences in the indebtedness of industries also depended on the level of agency costs related to the nature of their business and competition in the industry.

The industry debt median was used as a variable to explain volatility of SMEs' debt in the study of Jõeveer (2013) . The author assumed, as Frank and Goyal (2009) , that this debt is related to the general situation of the industry. Companies in a given industry aim at a similar financial structure. This is the result of a clash of capital needs determined by the technologies used, the structure of assets, the type of business, etc. and the confidence of creditors, which, in turn, affects debt capacity. Therefore, the industry's median debt is a measure of financial risk. Jõeveer (2013) demonstrated that belonging to an industry with a higher median debt also resulted in a higher share of debt in the capital structure of a single SME.

The share of debt in SMEs' capital structure is positively correlated with the median of the industry's indebtedness and negatively with the systematic business risk of this industry.

Factors shaping the capital structure of SMEs also occur at the country level. The literature divides them into two groups: macroeconomic and institutional factors ( Hernández-Cánovas and Koëter-Kant, 2011 ; Jõeveer, 2013 ; Mac An Bhaird and Lucey, 2014 ; Chipeta and Deressa, 2016 ; Moritz et al. , 2016 ; Kenourgios et al. , 2019 ). The study of Hernández-Cánovas and Koëter-Kant (2011) covered 3,366 SMEs from 19 Western Europe countries for 2002. It showed that the share of debt in the financing of these companies depended mainly on the level of property rights protection. Interestingly, the smaller the company, the stronger the impact. Similar dependence was shown by Mac An Bhaird and Lucey (2014) based on the data of over 90,000 companies from 13 Western European countries operating in the period 2002–2008. The authors found that companies' indebtedness also depended on the quality of the financial system in a given country and cultural environment. With reference to a study of 12,726 SMEs from 28 European countries, Moritz et al. (2016) showed that the indebtedness of businesses depended on the number and structure of operational programs financed by EU funds supporting the SME sector financially and organizationally. An extensive list of country-specific capital structure determinants was also applied by Jõeveer (2013) . The creditor and shareholders protection rights and corruption perception index proved to be important institutional factors (the better the protection and the lower the level of corruption, the higher the debt). Among the macroeconomic factors, gross domestic product (GDP) growth and savings were the main contributors to the increase in debt, while debt declined with a rise in market capitalization and inflation. Almost identical results were obtained by Chipeta and Deressa (2016) by analyzing 412 companies from 13 African countries operating in the years 2003–2008. The recent study conducted by Kenourgios et al. (2019) provides evidence that taxation is the most significant macroeconomic factor shaping the capital structure of listed SMEs in EU countries.

The analysis of the aforementioned studies shows that despite the significant impact of macroeconomic factors, institutional factors are more important for SMEs. Formal (law, procedures, public services for business) and physical (courts, offices, support and advisory institutions) institutions create business environment that, if properly developed, can encourage or deter SMEs from taking additional risks in the form of debt issuance. In turn, a properly developed financial system (banks, capital markets, instruments offered, etc.) provides easier access to capital. It is worth noting that these factors also play an important role at the regional level ( Palacín-Sánchez et al. , 2013 ; Palacín-Sánchez and di Pietro, 2016 ; la Rocca et al. , 2010 ).

The indebtedness of SMEs in CEE depends on main macroeconomic features and the quality of the legal and financial environment of the sector.

It is worth noting that in the case of CEE economies, the achievements of empirical research on the capital structure of SMEs are much more modest than those in Western Europe. This applies to studies of individual economies (see: Table 1 ) as well as cross-sectional studies. The latter include the research of Mateev et al. (2013) and Rahman et al. (2017) . The first study covered the financial data of 3,257 SMEs for the period 2001–2005. The authors did not specify countries but only stated that companies were operating in CEE. Using dynamic panel models, it was confirmed that companies' indebtedness increases with their size as well as with the financial surplus generated. The rate of growth of operating profits had a negative impact on debt. A small and undefined impact of industry factors was also found. Among country-specific factors, the relationship between tax rate and foreign direct investments was examined. For both factors, a positive relationship was found.

Rahman et al. (2017) examined 793 SMEs from Czechia, Slovakia and Hungary operating in 2012–2014. For the typical internal factors, debt dependency was found only on the size of the company (the bigger the company, the higher the debt). This dependence was most evident in the Czech economy. Industry factors were not studied. A weak positive dependence was also found for interest rates (country-specific factor). This dependence was also especially applicable to Czechia.

The identification of the determinants of the listed SME's capital structure for the economies of new EU members (Bulgaria, Croatia, Czech Republic, Slovenia, Slovakia, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Poland and Romania) is also included in the study ( Kenourgios et al. , 2019 ). Based on a panel of 3,267 observations in the period 2005–2015, the author showed that tangibility, sales (size) and business risk positively influenced the debt of enterprises. Only increasing profitability contributed to the reduction in debt. Among the country-specific factors, as for other economies, in new members of EU, SMEs' debt was positively affected by taxation.

3. Data and research sample

The source of research material was the EMIS database on corporate finance [1] . The time range of the study was 2014–2017. It was limited by the data provided. Financial data for SMEs from Bulgaria, Czechia, Hungary, Poland, Romania and Slovakia were taken from EMIS database. The selection of countries was dictated by the following criteria: (1) the date of accession to the EU, (2) the level of economic development, (3) the quantity and quality of data in the EMIS database and above all, (4) the common region: CEE. Such selection of the research sample was of interest for the authors of the study due to their country of origin and at the same time gave the opportunity to compare the results obtained with other countries of the region, which as a whole constitutes an important part of the EU.

The research sample was based on the SME definition established by the European Commission ( European Commission, 2003 ). The sample did not cover microenterprises due to the lack of reliable financial data for most of them. Therefore, the sample included companies that met the following conditions: (1) assets between 2 and 43 m euro, (2) revenues between 2 and 50 m euro and (3) employment between ten and 249 employees. A total of three conditions were taken into account at the same time in the study due to the difficulties in identifying companies that met only two of these conditions.

The breakdown of the companies in the sample was based on the industry classification of the EMIS database (14 industries). Due to the specificity of the industries, agricultural and financial companies were excluded from the sample. Due to the existence of observations which might have been errors in the database, some values of the variables were limited to ranges 0–1 (e.g. share of debt in all sources of financing, share of fixed assets in total assets) and/or to positive values (e.g. equity). The sample was also restricted to avoid the impact of outliers by 1% of the observations from the bottom and top of the distribution.

The study was based on variables, the definitions of which are presented in Table 2 . They are most frequently chosen by other authors, whose research was included in the literature review. We used total debt ratio (DR) to measure the company's capital structure (dependent variable). Variables characterizing classic firm-specific factors are as follows: TANG, SIZE, GROW, PROF, LIQ and NDTS.

At the company level, we included an additional debt capacity (DC) variable with two values: 1 and 0. Companies maintaining stock of DC for the whole research period (three years) were marked 1. The rest were marked 0. As Lev (1969) , Kale and Noe (1992) and Ghosh and Cai (1999) , we assumed that the threshold for DC was the median of the indebtedness of companies in a given country and industry. The negative difference between a company's current debt and the median of the industry's debt in the preceding year meant that the company held a DC stock.

The median debt of companies in a given industry is a variable characterizing financial risk in that industry. As a systematic business risk, following Kale et al. (1991) , Doff (2008) and Baum et al. (2017) , we assumed a weighted average of the coefficient of variation of operating flows of companies in a given industry. The weighting was the share of assets of a given company in the total assets of a given industry.

We used the ease of business score index as a variable characterizing the procedures and legal environment of SMEs in a given country. Access to credit was described by the private sector debt ratio. Annual GDP growth was used as a macroeconomic country-specific factor appropriate to the economic growth rate and inflation was used as a reference for the cost of credit in a given country. Country-level data were taken from the World Bank and International Monetary Fund databases.

Table 3 provides descriptive statistics on the dependent variable and the firm-specific factors used in the study.

For the sampled companies, the arithmetic mean and median values are similar for the following variables: DR, share of fixed assets in total assets (TANG) and company size (SIZE). For the NDTS variable, the difference is greater. For GROW, PROF and LIQ, the difference between the median and the arithmetic mean exceeds 35%. For these three variables, significant variability is also noticeable because the standard deviation is equal to or greater than the arithmetic mean. Therefore, the median should rather be used to analyze the average values in this sample. For minimum and maximum values, it can be seen that the SIZE, GROW and PROF variables have negative minimum values. For the SIZE variable, this means that some enterprises have assets of less than 1 m euro. For the GROW variable, this means that some enterprises have lower sales revenue in subsequent years than before. For the PROF variable, a negative minimum value means that the profitability of some enterprises is negative in some years.

Tables 4 and 5 describe the distribution of industry- and country-specific factors, respectively.

The average indebtedness of companies is around 0.5. The least average indebted industry is pharma and healthcare, for which the mean of debt is 0.455. The highest average indebtedness is in the food and beverage industry with 0.612. In turn, the systematic business risk (IND_Beta) is clearly different from the rest in consumer electronics. It is 1.013, while for all other industries it does not exceed 0.7, and for pharma and healthcare it is only 0.304. The percentage of companies that hold DC varies from 26% (real estate and construction) to 32% (food and beverage) depending on the industry.

In Table 5 , it can be seen that the country with the highest average corporate indebtedness is Slovakia (0.588), while the country with the lowest average is Czechia (0.469). This is a little bit surprising because these countries were one country relatively recently (less than 30 years ago). This disparity does not exist for the percentage of companies holding DC. It is similar for both countries and is below 20%, while in three out of the six countries analyzed, this ratio exceeds 30%. Table 6 also contains descriptive statistics by all countries for indicators such as EASE_BUS, PRIV_DEBT, GDP_GROW, INFLAT, whose values are similar. The exception is PRIV_DEBT in Bulgaria, which is almost twice as big as in the other countries. This may mean that Bulgaria benefits from the greatest private sector access to credit.

Pearson's linear correlation coefficients have been calculated for each of the pairs of variables to exclude any multicollinearity between the variables ( Table 6 ). Most coefficients between the explanatory variables do not show strong correlation. NDTS and TANG variables have the highest values of correlation with other variables. However, values of variance inflation factors (VIFs) below 10 mean that multicollinearity is acceptable.

According to the contents of H1 , the first stage of the study was to check whether the capital structure of companies in particular countries depends on factors related to the industry and country. For this purpose, a two-factor analysis of variance (ANOVA) was applied. This method enables to identify the existence of differences between averages in several populations. In our study, we checked whether the average DR values describing the capital structure of the examined companies differed significantly in the samples of companies from different industries and countries ( Lynch, 2013 ).

regression model (ordinary least squares [OLS] method):

(2)model with fixed effects:

(3)model with random effects:

The OLS is used for homogeneous samples. The Breusch–Pagan test was used in finding individual effects. In order to identify fixed or random characteristics of effects, the Hausman test is applied ( Greene, 2012 ). The estimation of model parameters was used for the verification of H2 and H3 .

The last stage of the study was to diagnose the significance of the influence of other assumed factors on the capital structure of the examined companies ( H4 to H6 ). For this purpose, previously used panel models were supplemented with corresponding variables: (1) characteristics of enterprises in terms of stored DC, (2) industry-specific factors and (3) institutional and macroeconomic country-specific factors. For the extended models, the Breusch–Pagan test was used to check if it was possible to use the OLS model or if there were individual effects. The extended models contain a DC dummy variable. Therefore, if the existence of individual effects is identified, the model with random effects should be used ( Gujarati and Porter, 2009 ).

Since we detected heteroscedasticity and autocorrelation in all our models, which could lead to incorrect estimation of variance and distortion of the significance of specific variables, we applied heteroscedasticity- and autocorrelation-consistent (HAC) standard errors ( Gujarati and Porter, 2009 ).

4. Research outcomes

4.1 anova analysis: impact of industry and country on smes' indebtedness.

In order to determine whether the country and industry differentiated the capital structure of the analyzed companies, a two-factor ANOVA was conducted. The results are presented in Table 7 .

The results show that although the country explains only 2.21% of the total variability and the industry only 1.14%, both analyzed factors statistically significantly influence the changes in corporate debt.

4.2 Panel model analysis: identification of significance and directions of relationships between firm-specific factors and SMEs' capital structure

Table 8 contains the results of estimating the parameters of models containing classical firm-specific factors for individual countries and the whole research sample. The table also includes the results of tests determining the significance of the whole model and indicating the choice of model version.

For the estimation of model parameters for all countries, a model with fixed effects was applied, which was driven by the Breusch–Pagan ( p < 0.0001) and Hausman ( p < 0.0001) test values. For easier analysis of the results, all statistically significant relationships (positive or negative) were moved to Table 9 .

In all analyzed economies, the increase in the share of fixed assets in total assets, as well as the growing profitability, liquidity and non-debt tax shield (except for Slovakia), caused a decrease in SMEs' debt. The opposite direction of dependence was diagnosed for the growth rate of enterprises and company size. Among all 36 relationships studied, only 1 relationship did not show statistical significance, while the remaining 35 relationships are fully consistent with the pecking order theory indications. Full compliance was also obtained for the whole sample, without specifying countries.

4.3 Extended panel model analysis: diagnosis of relationships between industry- and country-specific factors and SMEs' capital structure

Table 10 contains estimates of parameters of models extended by additional variables. Model (8) includes DC in addition to classical firm-specific factors. This variable is also present in the other models (9) to (11). All of them showed its statistically significant negative impact on SMEs’ debt.

Subsequent model (9) was extended with industry-specific factors. They are also present in models (10) and (11). IND_DR is statistically significant variable and positively influencing debt. The significance of the influence of IND_Beta was not confirmed by any model.

In model (10), country-specific factors were taken into account. This model shows statistically significant and positive relationships between DR and EASE_BUS and PRIV_DEBT. The macroeconomic country-specific factors were also found to be statistically significant. The higher the GDP growth in a country, the greater the indebtedness of SMEs. In the case of inflation, the relationship is the opposite.

The number of explanatory variables in model (11) has been reduced by the variable IND_Beta, whose significance was not confirmed by any model. In almost all models, there are the same directions of relationship between DR and firm-specific factors. This signifies the positive results of robustness check of these relationships. The exception is the NDTS variable. Models (9) and (10) do not demonstrate a significance of the impact of the NDTS variable on SMEs' debt. In comparison to models (1) to (7), it can be related to the application of the random effects model. This difference is not detected by models (8) and (11), where the statistically insignificant variable IND_BUS was not included.

5. Conclusions

The study shows that the capital structure of SMEs from CEE is shaped primarily by firm-specific factors. The industry-specific factors area explains about 1.2% of the variability of corporate debt, while the country-specific factors area explains about 2.3% of that variability. This is confirmed by Jõeveer (2013) , the much wider impact of SME's country-specific factors on capital structure than industry variables (support for H1 ). However, the combined impact of factors from both areas is less than half as in the case of more developed economies. This observation is consistent with previous studies ( Mateev et al. , 2013 ). However, the causes and nature of these differences require further in-depth research.

We also corroborated H2 by demonstrating a statistically significant dependence of the CEE SMEs' debt on all established firm-specific factors. We therefore obtained confirmation of earlier findings that the smaller the company, the greater the number of diagnosed firm-specific determinants of capital structure ( Sogorb-Mira, 2005 ).

We identified statistically significant negative impact on SMEs' debt of the following variables: tangibility, profitability and liquidity. The positive relation was diagnosed for size and growth. The significance and direction of influence of the firm-specific factors on SMEs' capital structure in CEE are consistent with the pecking order theory. It supports H3 . We also obtained strong support for H4 : SMEs indebted below the DC maintain its stock and do not increase their debt. It is also consistent with the pecking order theory.

The study showed that SMEs' indebtedness is determined by one of the assumed industry-specific factors. Therefore, our study only partially supports H5 . The share of debt in capital structure depends on the financial risk of the industry. Similar to Frank and Goyal (2009) ; Jõeveer (2013 ), we found that if the industry was perceived by creditors as more safe (higher average industry debt), the companies belonging to the industry were more likely to use debt. We did not obtain the same confirmation for systematic industry business risk. This is contrary to the findings made for large companies by Kale et al. (1991) ; Schwert and Strebulaev (2014) ; Palazzo (2019 ). It may be a specific feature of the SME sector, but this thesis requires a broader and more detailed study.

The results of the CEE SMEs' country-specific factors study do not contradict the previously obtained results ( Mateev et al. , 2013 ; Rahman et al. , 2017 ) and support H6 . The institutional country-specific factors analysis provides results similar to those in Jõeveer (2013) . It has been shown that the more business-friendly the legal and institutional environment, the more CEE SMEs are willing to go into debt. We have also shown that with the growing availability of credit in the private sector, corporate debt also increases. The study on macroeconomic country-specific factors also included variables applied by Jõeveer (2013) . The results obtained are also similar. This means that, as in the case of mature economies, CEE SME's debt is positively affected by GDP growth, while the impact of the cost of debt (inflation rate) is negative.

The above results, with institutional variables added, are linked to some practical implications. Our study shows that a business-friendly legal and institutional environment is a very important factor influencing the indebtedness of companies and thus increasing leverage and, consequently, the return on equity. The transition to a market economy in CEE countries took place only 30 years ago. Still, a significant part of society, including businessmen, remembers the obstacles that the state caused to economic activity.

The limitations of the study are (1) the inclusion of only six CEE countries in the sample and (2) the exclusion of microenterprises from the sample, i.e. those enterprises that employ fewer than ten people and whose value and revenue does not exceed 2 m euro. However, it should be noted that the largest economies and the most important countries of the region, which are also members of the EU, are included in the study. Microenterprises' data were excluded mainly due to the low reliability of their financial data. (3) The capital structure relationships are observed following the applications of the static panel and (4) the endogeneity issue is not addressed in the model. However, it should be noted that the problem of endogeneity occurs mainly in the case of simultaneous equation models, measurement errors and omitted variables. In the case of our study, we rely on the single-equation model, and it is not a transformed version of the more complicated model. We also made efforts to remove unreliable data, and estimations of many models with different number of variables did not change the conclusions. Therefore, we believe that this problem did not significantly affect our results.

Empirical studies on SME's capital structure

Note(s): * dependence is significant at the level of 0.1; ** dependence is significant at the level of 0.05; *** dependence is significant at the level of 0.01 (standard errors in parentheses)

Source(s): own elaboration

EMIS (formerly known ISI Emerging Markets Group) was established in 1994. It is a consulting company focused on emerging markets. EMIS operates in and reports on countries where high reward goes hand-in-hand with high risk. It brings information, research and analytical data, peer comparisons and more for over 147 emerging markets ( https://www.emis.com ).

Aybar-Arias , C. , Casino-Martínez , A. and López-Gracia , J. ( 2012 ), “ On the adjustment speed of SMEs to their optimal capital structure ”, Small Business Economics , Vol. 39 No. 4 , pp. 977 - 996 .

Baños-Caballero , S. , García-Teruel , P.J. and Martínez-Solano , P. ( 2012 ), “ How does working capital management affect the profitability of Spanish SMEs? ”, Small Business Economics , Vol. 39 No. 2 , pp. 517 - 529 .

Baños-Caballero , S. , García-Teruel , P.J. and Martínez-Solano , P. ( 2016 ), “ Financing of working capital requirement, financial flexibility and SME performance ”, Journal of Business Economics and Management , Vol. 17 No. 6 , pp. 1189 - 1203 .

Baum , C.F. , Caglayan , M. and Rashid , A. ( 2017 ), “ Capital structure adjustments: do macroeconomic and business risks matter? ”, Empirical Economics , Vol. 53 No. 4 , pp. 1463 - 1502 .

Baxter , N.D. ( 1967 ), “ Leverage, risk of ruin and the cost of capital ”, The Journal of Finance , Vol. 22 No. 3 , pp. 395 - 404 .

Beck , T. and Demirguc-Kunt , A. ( 2006 ), “ Small and medium-size enterprises: access to finance as a growth constraint ”, Journal of Banking and Finance , Vol. 25 No. 6 , pp. 932 - 952 .

Beck , T. , Demirgüç-Kunt , A. and Maksimovic , V. ( 2008 ), “ Financing patterns around the world: are small firms different? ”, Journal of Financial Economics , Vol. 89 No. 3 , pp. 467 - 487 .

Belas , J. , Gavurova , B. and Toth , P. ( 2018 ), “ Impact of selected characteristics of smes on the capital structure ”, Journal of Business Economics and Management , Vol. 19 No. 4 , pp. 592 - 608 .

Bharath , S.T. , Pasquariello , P. and Wu , G. ( 2009 ), “ Does asymmetric information drive capital structure decisions ”, Review of Financial Studies , Vol. 22 No. 8 , pp. 3211 - 3243 .

Brav , O. ( 2009 ), “ Access to capital, capital structure, and the funding of the firm ”, Journal of Finance , Vol. 64 , pp. 263 - 308 .

Brighi , P. and Torluccio , G. ( 2010 ), “ Evidence on funding decisions by Italian SMEs: a self-selection model? ”, SSRN Electronic Journal , June , pp. 1 - 19 .

Cassar , G. and Holmes , S. ( 2003 ), “ Capital structure and financing of SMEs: Australian evidence ”, Accounting and Finance , Vol. 43 No. 2 , pp. 123 - 147 .

Chipeta , C. and Deressa , C. ( 2016 ), “ Firm and country specific determinants of capital structure in Sub Saharan Africa ”, International Journal of Emerging Markets , Vol. 11 No. 4 , pp. 649 - 673 .

Chirinko , R.S. and Singha , A.R. ( 2000 ), “ Testing static tradeoff against pecking order models of capital structure: a critical comment ”, Journal of Financial Economics , Vol. 58 No. 3 , pp. 417 - 425 .

Degryse , H. , de Goeij , P. and Kappert , P. ( 2012 ), “ The impact of firm and industry characteristics on small firms' capital structure ”, Small Business Economics , Vol. 38 , pp. 431 - 747 .

Doff , R. ( 2008 ), “ Defining and measuring business risk in an economic-capital framework ”, The Journal of Risk Finance , Vol. 9 No. 4 , pp. 317 - 333 .

European Central Bank . ( 2014 ), “ Survey on the access to finance of small and medium-sized enterprises in the Euro area October 2013 to March 2014 April 2014 ”, No. April , available at: https://www.ecb.europa.eu/stats/accesstofinancesofenterprises/pdf/accesstofinancesmallmediumsizedenterprises201311en.pdf?f5ab9fefb7ee0bd0455541a97d80cbfa .

European Commission ( 2003 ), “ Recommendation 2003/361/ EC ”, Official Journal of the European Union , Vol. L124 , p. 30 , European Commision .

European Commission ( 2007 ), “ Observatory of European SMEs: analytical report ”, available at: https://ec.europa.eu/commfrontoffice/publicopinion/flash/fl196_en.pdf .

Eurostat . ( 2015 ), “ Database – Eurostat ”, available at: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/data/database ( accessed 14 September 2019 ).

Evans , D.S. ( 1987 ), “ Tests of alternative theories of firm growth ”, Journal of Political Economy , Vol. 95 , pp. 657 - 674 .

Forte , D. , Barros , L.A. and Nakamura , W.T. ( 2013 ), “ Determinants of the capital structure of small and medium sized Brazilian enterprises ”, Brazilian Administration Review , Vol. 10 No. 3 , pp. 347 - 369 .

Frank , M.Z. and Goyal , V.K. ( 2009 ), “ Capital structure decisions: which factors are reliably important? ”, Financial Management , Vol. 38 Nos 1–37 , doi: 10.1111/j.1755-053X.2009.01026.x .

Frydenberg , S. ( 2011 ), “ Capital structure theories and empirical tests: an overview ”, in Baker , K.H. and Martin , G.S. (Eds), Capital Structure and Corporate Financing Decisions: Theory, Evidence, and Practice , John Wiley & Sons , pp. 127 - 149 .

Ghosh , A. and Cai , F. ( 1999 ), “ Capital structure: new evidence of optimality and pecking order theory ”, American Business Review , Vol. 17 No. 1 , pp. 32 - 38 .

Greene , W.H. ( 2012 ), Econometric Analysis , Pearson , London .

Gujarati , D.N. and Porter , D.C. ( 2009 ), Basic Econometrics , 5th ed. , McGraw-Hill/Irwin , New York , Basic Econometrics .

Hall , G. , Hutchinson , P. and Michaelas , N. ( 2000 ), “ Industry effects on the determinants of unquoted SMEs' capital structure ”, International Journal of the Economics of Business , Vol. 7 No. 3 , pp. 297 - 312 .

Hall , G. , Hutchinson , P. and Michaelas , N. ( 2004 ), “ Determinants of the capital structures of European SMEs ”, Journal of Business Finance and Accounting , Vol. 31 Nos 5–6 , pp. 711 - 728 .

Harc , M. ( 2015 ), “ The relationship between tangible assets and capital structure of small and medium-sized companies in Croatia ”, Ekonomski Vjesnik , Vol. 28 No. 1 , pp. 213 - 224 .

Harris , M. and Raviv , A. ( 1991 ), “ The theory of capital structure ”, The Journal of Finance , Vol. XLVI No. 1 , pp. 297 - 355 .

Hernández-Cánovas , G. and Koëter-Kant , J. ( 2011 ), “ SME financing in Europe: cross-country determinants of bank loan maturity ”, International Small Business Journal , Vol. 29 No. 5 , pp. 489 - 507 .

Huang , R. and Ritter , J. ( 2005 ), “ Testing the market timing theory of capital structure ”, Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis , Vol. 1 , pp. 221 - 246 .

Jõeveer , K. ( 2013 ), “ What do we know about the capital structure of small firms? ”, Small Business Economics , Vol. 41 No. 2 , pp. 479 - 501 .

Kale , J.R. and Noe , T.H. ( 1992 ), “ Taxes, financial distress, and corporate capital structure ”, Quarterly Review of Economics and Finance , Vol. 32 No. 1 , pp. 71 - 83 .

Kale , J.R. , Noe , T.H. and Ramirez , G.G. ( 1991 ), “ The effect of business risk on corporate capital structure: theory and evidence ”, The Journal of Finance , Vol. 46 No. 5 , pp. 1693 - 1715 .

Kayhan , A. and Titman , S. ( 2007 ), “ Firms' histories and their capital structures ”, Journal of Financial Economics , Elsevier B.V. , Vol. 83 No. 1 , pp. 1 - 32 .

Kenourgios , D. , Savvakis , G.A. and Papageorgiou , T. ( 2019 ), “ The capital structure dynamics of European listed SMEs ”, Journal of Small Business and Entrepreneurship , Vol. 32 , pp. 567 - 584 .

Kersten , R. , Harms , J. , Liket , K. and Maas , K. ( 2017 ), “ Small firms, large impact? A systematic review of the SME finance literature ”, World Development , Vol. 97 , pp. 330 - 348 .

Kim , E.H. ( 1978 ), “ A mean-variance theory of optimal capital structure and corporate debt capacity ”, The Journal of Finance , Vol. 33 No. 1 , pp. 45 - 63 .

Klein , L.S. , O'Brien , T.J. and Peters , S.R. ( 2002 ), “ Debt vs equity and asymmetric information: a review ”, Financial Review , Vol. 37 No. 3 , pp. 317 - 349 .

Kraus , A. and Litzenberger , R.H. ( 1973 ), “ A state-preference model of optimal financial leverage ”, The Journal of Finance , Vol. 28 No. 4 , pp. 911 - 922 .

Kumar , S. and Rao , P. ( 2015 ), “ A conceptual framework for identifying financing preferences of SMEs ”, Small Enterprise Research , Taylor & Francis , Vol. 22 No. 1 , pp. 99 - 112 .

Kumar , S. , Sureka , R. and Colombage , S. ( 2020 ), “ Capital structure of SMEs: a systematic literature review and bibliometric analysis ”, Management Review Quarterly , Vol. 70 , pp. 535 - 565 , doi: 10.1007/s11301-019-00175-4 .

la Rocca , M. , la Rocca , T. and Cariola , A. ( 2010 ), “ The influence of local institutional differences on the capital structure of SMEs: evidence from Italy ”, International Small Business Journal , Vol. 28 No. 3 , pp. 234 - 257 .

Leary , M.T. and Roberts , M.R. ( 2005 ), “ Do firms rebalance their capital structures? ”, Journal of Finance , Vol. LX No. 6 , pp. 2575 - 2618 .

Lemmon , M.L. and Zender , J.F. ( 2010 ), “ Debt capacity and tests of capital structure theories ”, Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis , Vol. 45 No. 5 , pp. 1161 - 1187 .

Lemmon , M.L. , Roberts , M.R. and Zender , J.F. ( 2008 ), “ Back to the beginning: persistence and the cross-section of corporate capital structure ”, Journal of Finance , Vol. 63 No. 4 , pp. 1575 - 1608 .

Lev , B. ( 1969 ), “ Industry averages as targets for financial ratios ”, Journal of Accounting Research , Vol. 7 No. 2 , pp. 290 - 299 .

López-Gracia , J. and Sogorb-Mira , F. ( 2008 ), “ Testing trade-off and pecking order theories financing SMEs ”, Small Business Economics , Vol. 31 No. 2 , pp. 117 - 136 .

Lynch , S.M. ( 2013 ), “Comparing Means across Multiple Groups: Analysis of Variance (ANOVA)”, Using Statistics in Social Research: A Concise Approach , Springer , New York .

Mac an Bhaird , C. and Lucey , B. ( 2010 ), “ Determinants of capital structure in Irish SMEs ”, Small Business Economics , Vol. 35 No. 3 , pp. 357 - 375 .

Mac An Bhaird , C. and Lucey , B. ( 2014 ), “ Culture's influences: an investigation of inter-country differences in capital structure ”, Borsa Istanbul Review , Elsevier , Vol. 14 No. 1 , pp. 1 - 9 .

Martinez , L.B. , Scherger , V. and Guercio , M.B. ( 2019 ), “ SMEs capital structure: trade-off or pecking order theory: a systematic review ”, Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development , Vol. 26 No. 1 , pp. 105 - 132 .

Mateev , M. , Poutziouris , P. and Ivanov , K. ( 2013 ), “ On the determinants of SME capital structure in central and eastern Europe: a dynamic panel analysis ”, Research in International Business and Finance , Vol. 27 No. 1 , pp. 28 - 51 .

Matias , F. and Serrasqueiro , Z. ( 2017 ), “ Are there reliable determinant factors of capital structure decisions? Empirical study of SMEs in different regions of Portugal ”, Research in International Business and Finance , Vol. 40 , pp. 19 - 33 .

Michaelas , N. , Chittenden , F. and Poutziouris , P. ( 1999 ), “ Financial policy and capital structure choice in UK SMEs: empirical evidence from company panel data ”, Small Business Economics , Vol. 12 No. 2 , pp. 113 - 130 .

Modigliani , F. and Miller , M.H. ( 1958 ), “ The cost of capital, corporation finance and theory of investment ”, The American Economic Review , Vol. 48 No. 3 , pp. 261 - 297 .

Moritz , A. , Block , J.H. and Heinz , A. ( 2016 ), “ Financing patterns of European SMEs – an empirical taxonomy ”, Venture Capital , Routledge , Vol. 18 No. 2 , pp. 115 - 148 .

Myers , S.C. ( 1984 ), “ The capital structure puzzle ”, The Journal of Finance , Vol. 39 No. 3 , pp. 574 - 592 .

Myers , S.C. and Majluf , N.S. ( 1984 ), “ Corporate financing and investment decisions when firms have information that investors do not have ”, Journal of Financial Economics , Vol. 13 No. 2 , pp. 187 - 221 .

Nguyen , T.D.K. and Ramachandran , N. ( 2006 ), “ Capital structure in small and medium- sized enterprises: the case of Vietnam ”, Asean Economic Bulletin , Vol. 23 No. 2 , pp. 192 - 211 .

Palacín-Sánchez , M.J. and di Pietro , F. ( 2016 ), “ The role of the regional financial sector in the capital structure of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) ”, Regional Studies , Vol. 50 No. 7 , pp. 1232 - 1247 .

Palacín-Sánchez , M.J. , Ramírez-Herrera , L.M. and di Pietro , F. ( 2013 ), “ Capital structure of SMEs in Spanish regions ”, Small Business Economics , Vol. 41 No. 2 , pp. 503 - 519 .

Palazzo , B. ( 2019 ), “ Cash flows risk, capital structure, and corporate bond yields ”, Annals of Finance , Vol. 15 No. 3 , pp. 401 - 420 .

Prędkiewicz , K. and Prędkiewicz , P. ( 2015 ), “ Chosen determinants of capital structure in small and medium-sized enterprises ”, Zeszyty Naukowe Uniwersytetu Szczecińskiego , Vol. 855 , pp. 331 - 340 .

Psillaki , M. and Dasaklakis , N. ( 2009 ), “ Are the determinants of capital structure country or firm specific? ”, Small Business Economics , Vol. 33 , pp. 319 - 333 .

Rahman , A. , Rahman , M.T. and Belas , J. ( 2017 ), “ Determinants of SME finance: evidence from three central European countries ”, Review of Economic Perspectives , Vol. 17 No. 3 , pp. 263 - 285 .

Rajan , R.G. and Zingales , L. ( 1995 ), “ What do we know about capital structure? Some evidence from international data ”, The Journal of Finance , Vol. 50 No. 5 , pp. 1421 - 1460 .

Sánchez-Vidal , J. and Martín-Ugedo , J.F. ( 2005 ), “ Financing preferences of Spanish firms: evidence on the pecking order theory ”, Review of Quantitative Finance and Accounting , Vol. 25 No. 4 , pp. 341 - 355 .

Schwert , M. and Strebulaev , I.A. ( 2014 ), Capital Structure And Systematic Risk , Rock Center for Corporate Goveernance, Working Papers Series, No. 178 , pp. 1 - 33 .

Scott , J.H. ( 1976 ), “ A theory of optimal capital structure ”, The Bell Journal of Economics , Vol. 7 No. 1 , pp. 33 - 54 .

Shyam-Sunder , L. and C Myers , S. ( 1999 ), “ Testing static tradeoff against pecking order models of capital structure ”, Journal of Financial Economics , Vol. 51 No. 2 , pp. 219 - 244 .

Sogorb-Mira , F. ( 2005 ), “ How SME uniqueness affects capital structure: evidence from a 1994-1998 Spanish data panel ”, Small Business Economics , Vol. 25 , pp. 447 - 457 .

Ughetto , E. , Scellato , G. and Cowling , M. ( 2017 ), “ Cost of capital and public loan guarantees to small firms ”, Small Business Economics , Vol. 49 No. 2 , pp. 319 - 337 .

Vanacker , T. and Manigart , S. ( 2010 ), “ Incremental financing decisions in high growth companies: pecking order and capacity considerations ”, Small Business Economics , Vol. 35 No. 1 , pp. 53 - 69 .

Watson , R. and Wilson , N. ( 2002 ), “ Small and medium size enterprise financing: a note on some of the empirical implications of a pecking order ”, Journal of Business Finance and Accounting , Vol. 29 No. 3 , pp. 557 - 578 .

Corresponding author

Related articles, we’re listening — tell us what you think, something didn’t work….

Report bugs here

All feedback is valuable

Please share your general feedback

Join us on our journey

Platform update page.

Visit emeraldpublishing.com/platformupdate to discover the latest news and updates

Questions & More Information

Answers to the most commonly asked questions here

A Systematic Review of Literature and Comprehensive Bibliometric Analysis of Capital Structure Issue

- Dominika GAJDOSIKOVA University of Zilina https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7705-3264

- Katarina VALASKOVA University of Zilina https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4223-7519

Adu-Ameyaw, E., Danso, A., Acheampong, S., & Akwei, C. (2021). Executive bonus compensation and financial leverage: do growth and executive ownership matter? International Journal of Accounting & Information Management, 29(3), 392-409. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJAIM-09-2020-0141

Ahmad, S., Sohail, M., Waris, A., Elginaid, A., & Mohammed, I. (2018). SCImago, eigenfactor score, and H5 index journal rank indicator: a study of journals in the area of construction and building technologies. DESIDOC Journal of Library & Information Technology, 38(4), 278-285. https://doi.org/10.14429/djlit.38.4.11503

Ashraf, D., Rizwan, M. S., & Azmat, S. (2021). Not one but three decisions in sukuk issuance: understanding the role of ownership and governance. Pacific-Basin Finance Journal, 69, 101423. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pacfin.2020.101423

Belas, J., Gavurova, B., & Toth, P. (2018). Impact of selected characteristics of SMES on the capital structure. Journal of Business Economics and Management, 19(4), 592-608. https://doi.org/10.3846/jbem.2018.6583

Bigio, S., & d'Avernas, A. (2021). Financial risk capacity. American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics, 13(4), 142-181. https://doi.org/10.1257/mac.20160286

Czerwonka, L., & Jaworski, J. (2021). Capital structure determinants of small and medium-sized enterprises: evidence from Central and Eastern Europe. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 28(2), 277-297. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSBED-09-2020-0326

de Oliveira, M. E. A., Alves, F. I. A. B., & Souza, J. L. (2019). The female participation in the academic production on capital structure in Brazilian journals. HOLOS, 35(4), 1-24. https://doi.org/10.15628/holos.2019.8255

Diantimala, Y., Syahnur, S., Mulyany, R., & Faisal, F. (2021). Firm size sensitivity on the correlation between financing choice and firm value. Cogent Business & Management, 8(1), 1926404. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2021.1926404

Dimitrova, M., Treapat, L. M., & Tulaykova, I. (2021). Value at risk as a tool for economic-managerial decision-making in the process of trading in the financial market. Ekonomicko-manazerske spektrum, 15(2), 13-26. https://doi.org/10.26552/ems.2021.2.13-26

Duong, K. T., Banti, C., & Instefjord, N. (2021). Managerial conservatism and corporate policies. Journal of Corporate Finance, 68, 101973. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2021.101973

Durana, P., Michalkova, L., Privara, A., Marousek, J., & Tumpach, M. (2021). Does the life cycle affect earnings management and bankruptcy? Oeconomia Copernicana, 12(2), 425-461. https://doi.org/10.24136/oc.2021.015

Dvoulety, O., & Blazkova, I. (2021). Exploring firm-level and sectoral variation in total factor productivity (TFP). International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 27(6), 1526-1547. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEBR-11-2020-0744

Ellili, N. O. D. (2020). Environmental, social, and governance disclosure, ownership structure and cost of capital: evidence from the UAE. Sustainability, 12(18), 7706. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12187706

Garfield, E. (2006). Citation indexes for science. A new dimension in documentation through association of ideas. International journal of epidemiology, 35(5), 1123-1127. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyl189

Gashi Ahmeti, H. & Feta, B. (2021). Determinants of financing obstacles of SMEs in Western Balkans. Management Dynamics in the Knowledge Economy, 9(3), 331-344. https://doi.org/10.2478/mdke-2021-0022

Goksu, I. (2021). Bibliometric mapping of mobile learning. Telematics and Informatics, 56, 101491. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2020.101491

Goldbach, S., Moen, J., Schindler, D., Schjelderup, G., & Wamser, G. (2021). The tax-efficient use of debt in multinational corporations. Journal of Corporate Finance, 71, 102119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2021.102119

Gregory, R. P. (2022). Social capital and capital structure. Journal of Sustainable Finance & Investment, 12(2), 655-668. https://doi.org/10.1080/20430795.2020.1796418

Gregova, E., Smrcka, L., Michalkova, L., & Svabova, L. (2021). Impact of tax benefits and earnings management of capital structures across V4 countries. Acta Polytechnica Hungarica, 18(3), 221-244.

Gurusamy, P. (2021). Corporate ownership structure and its effect on capital structure: evidence from BSE listed manufacturing companies in India. IIM Kozhikode Society & Management Review. https://doi.org/10.1177/2277975220968305

Hanlon, M., & Heitzman, S. (2010). A review of tax research. Journal of accounting and Economics, 50(2-3), 127-178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacceco.2010.09.002

Haron, R., Nomran, N. M., Othman, A. H. A., Husin, M. M., & Sharofiddin, A. (2021). The influence of firm, industry and concentrated ownership on dynamic capital structure decision in emerging market. Journal of Asia Business Studies, 15(5), 689-709. https://doi.org/10.1108/JABS-04-2019-0109

Hlawiczka, R., Blazek, R., Santoro, G., & Zanellato, G. (2021). Comparison of the terms creative accounting, earnings management and fraudulent accounting through bibliographic analysis. Ekonomicko-manazerske spektrum, 15(2), 27-37. https://doi.org/10.26552/ems.2021.2.27-37

Jaworski, J., & Czerwonka, L. (2021). Determinants of enterprises’ capital structure in energy industry: evidence from European Union. Energies, 14(7), 1871. https://doi.org/10.3390/en14071871

Jimenez-Caballero, J. L., & Polo Molina, S. (2017). A bibliometric analysis of the presence of finances in high-impact tourism journals. Current Issues in Tourism, 20(3), 225-232. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2016.1164674

Karas, M., & Reznakova, M. (2021). The role of financial constraint factors in predicting SME default. Equilibrium. Quarterly Journal of Economics and Economic Policy, 16(4), 859-883. https://doi.org/10.24136/eq.2021.032

Khoa, B. T., & Thai, D. T. (2021). Capital structure and trade-off theory: evidence from Vietnam. The Journal of Asian Finance, Economics, and Business, 8(1), 45-52. https://doi.org/10.13106/jafeb.2021.vol8.no1.045

Kristofik, P., & Slampiakova, L. (2021). Differences in capital structure of publicly traded companies in Europe and USA. Politicka ekonomie, 69(3), 322-339. https://doi.org/10.18267/j.polek.1320

Kruk, S. (2021). Impact of capital structure on corporate value - review of literature. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 14(4), 155. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm14040155

Kucera, J., Vochozka, M., & Rowland, Z. (2021). The ideal debt ratio of an agricultural enterprise. Sustainability, 13(9), 4613. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13094613

Kumar, S., & Sureka R., & Colombage, S. (2020). Capital structure of SMEs: a systematic literature review and bibliometric analysis. Management Review Quarterly, 70(4), 535-565. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11301-019-00175-4

Malmendier, U., Tate, G., & Yan, J. (2011). Overconfidence and early‐life experiences: the effect of managerial traits on corporate financial policies. The Journal of Finance, 66(5), 1687-1733. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6261.2011.01685.x

Maniu, I., Costea, R., Maniu, G., & Neamtu, B. M. (2021). Inflammatory biomarkers in febrile seizure: a comprehensive bibliometric, review and visualization analysis. Brain Sciences, 11(8), 1077. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci11081077

Merigo, J. M., Pedrycz, W., Weber, R., & de la Sotta, C. (2018). Fifty years of information sciences: a bibliometric overview. Information Sciences, 432, 245-268. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ins.2017.11.054

Michalkova, L., Stehel, V., Nica, E., & Durana, P. (2021). Corporate management: capital structure and tax shields. Marketing and Management of Innovations, 3, 276-295. https://doi.org/10.21272/mmi.2021.3-23

Motylska-Kuzma, A. (2017). The financial decisions of family businesses. Journal of family business management, 7(3), 351-373. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFBM-07-2017-0019

Mouandat, S. R. (2022). Is foreign debt management in Gabon efficient? Management Dynamics in the Knowledge Economy, 10(1), 82-94. https://doi.org/10.2478/mdke-2022-0006

Mujkic, E. The influence of the financial structure of capital on the estimated value of the company. Casopis Za Ekonomiju I Trzisne Komunikacije, 11(1), 240-253. https://doi.org/10.7251/EMC2101240M

Nylund, P. A., Arimany-Serrat, N., Ferras-Hernandez, X., Viardot, E., Boateng, H., & Brem, A. (2019). Internal and external financing of innovation: sectoral differences in a longitudinal study of European firms. European Journal of Innovation Management, 23(2), 200-213. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJIM-09-2018-0207

Padilla-Ospina, A. M., Medina-Vasquez, J. E., & Rivera-Godoy, J. A. (2018). Financing innovation: a bibliometric analysis of the field. Journal of Business & Finance Librarianship, 23(1), 63-102. https://doi.org/10.1080/08963568.2018. 1448678

Panda, A. K., Nanda, S., Hegde, A. A., & Yadav, A. K. K. (2021). Receptivity of capital structure with financial flexibility: a study on manufacturing firms. International Journal of Finance & Economics. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijfe.2521

Parmar, B. L., Freeman, R. E., Harrison, J. S., Wicks, A. C., Purnell, L., & De Colle, S. (2010). Stakeholder theory: the state of the art. Academy of Management Annals, 4(1), 403-445. https://doi.org/10.1080/19416520.2010.495581

Prokop, V., Striteska, M. K., & Stejskal, J. (2021). Fostering Czech firms? innovation performance through efficient cooperation. Oeconomia Copernicana, 12(3), 671-700. https://doi.org/10.24136/oc.2021.022

Ruckova, P., & Skulanova, N. (2021). The determination of financial structure in agriculture, forestry and fishing industry in selected countries of Central and Eastern Europe. E&M Ekonomie a Management, 24(3), 58-78. https://doi.org/10.15240/tul/001/2021-03-004

Singh, V. K., Singh, P., Karmakar, M., Leta, J., & Mayr, P. (2021). The journal coverage of Web of Science, Scopus and Dimensions: a comparative analysis. Scientometrics, 126(6), 5113-5142. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-021-03948-5

Sivak, R., & Mikocziova, J. (2002). A contribution to an optimal capital structure theory of an enterprise. Politicka Ekonomie, 50(1), 93-109.

Spitsin, V., Vukovic, D., Anokhin, S., & Spitsina, L. (2020). Company performance and optimal capital structure: evidence of transition economy (Russia). Journal of Economic Studies, 48(2), 313-332. https://doi.org/10.1108/JES-09-2019-0444

Stefko, R., Vasanicova, P., Jencova, S., & Pachura, A. (2021). Management and economic sustainability of the Slovak industrial companies with medium energy intensity. Energies, 14(2), 267. https://doi.org/10.3390/en14020267

Tasaryova, K., & Paksiova, R. (2021). The impact of equity information as an important factor in assessing business performance. Information, 12(2), 85. https://doi.org/10.3390/info12020085

Tousek, Z., Hinke, J., Malinska, B., & Prokop, M. (2021). The performance determinants of trading companies: a stakeholder perspective. Journal of Competitiveness, 13(2), 152-170. https://doi.org/10.7441/joc.2021.02.09

Tripathy, N., Wu, D., & Zheng, Y. (2021). Dividends and financial health: evidence from US bank holding companies. Journal of Corporate Finance, 66, 101808. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2020.101808

Valaskova, K., Kliestik, T., & Gajdosikova, D. (2021). Distinctive determinants of financial indebtedness: evidence from Slovak and Czech enterprises. Equilibrium. Quarterly Journal of Economics and Economic Policy, 16(3), 639-659. https://doi.org/10.24136/eq.2021.023

Vo, M. T. (2021). Capital structure and cost of capital when prices affect real investments. Journal of Economics and Business, 113, 105944. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeconbus.2020.105944

Wang, C., Brabenec, T., Gao, P., & Tang, Z. (2021). The business strategy, competitive advantage and financial strategy: a perspective from corporate maturity mismatched investment. Journal of Competitiveness, 13(1), 164-181. https://doi.org/10.7441/joc.2021.01.10

Yagi, K., & Takashima, R. (2012). The impact of convertible debt financing on investment timing. Economic Modelling, 29(6), 2407-2416. https://doi.org/10.1016/ j.econmod.2012.06.032

Yang, J. A., Chou, S. R., Cheng, H. C., & Lee, C. H. (2010). The effects of capital structure on firm performance in the Taiwan 50 and Taiwan Mid-Cap 100. Journal of Statistics and Management Systems, 13(5), 1069-1078. https://doi.org/10.1080/ 09720510.2010.10701521

Zhu, D., Qiu, Z., & Wang, J. (2021). Factors affecting the capital structure of listed Chinese media companies. International Journal of Finance & Economics, 1-10. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijfe.2580

How to Cite

- Endnote/Zotero/Mendeley (RIS)

Copyright (c) 2022 Dominika GAJDOSIKOVA, Katarina VALASKOVA

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License .

Under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs license, the users are free to share (copy, distribute and transmit the contribution) with the condition to attribute the contribution in the manner specified by the author or licensor. They may not alter, transform, or build upon this work.

Information

- For Readers

- For Authors

- For Librarians

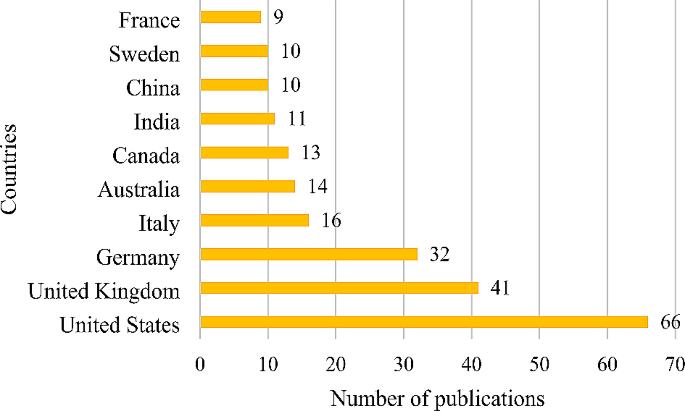

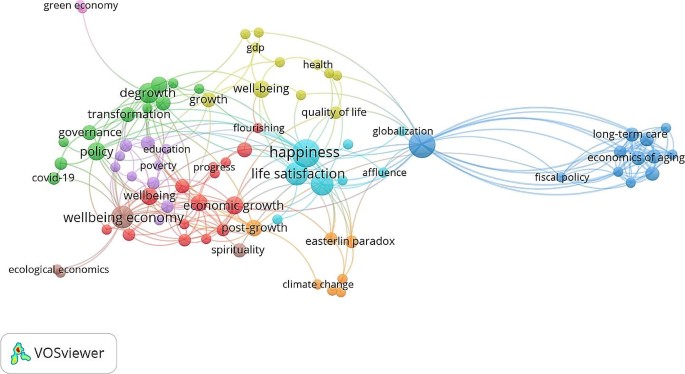

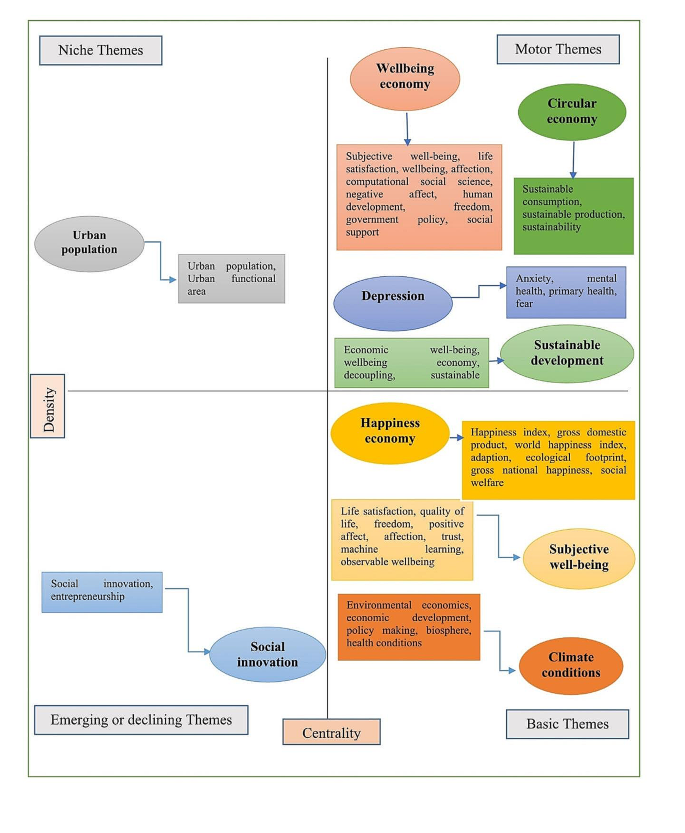

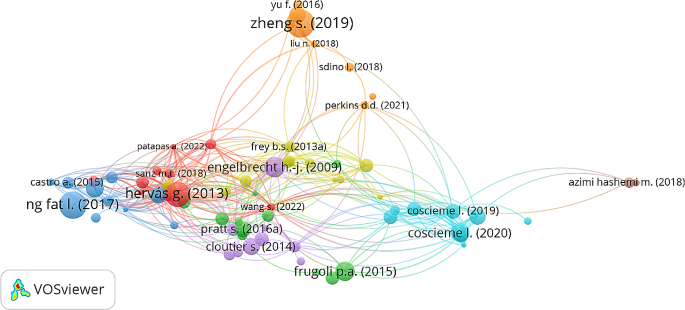

From economic wealth to well-being: exploring the importance of happiness economy for sustainable development through systematic literature review

- Open access

- Published: 23 May 2024

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Shruti Agrawal ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-1620-9429 1 , 5 ,

- Nidhi Sharma 1 , 5 ,

- Karambir Singh Dhayal ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-0000-4330 2 &

- Luca Esposito ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5983-6898 3 , 4

596 Accesses

Explore all metrics

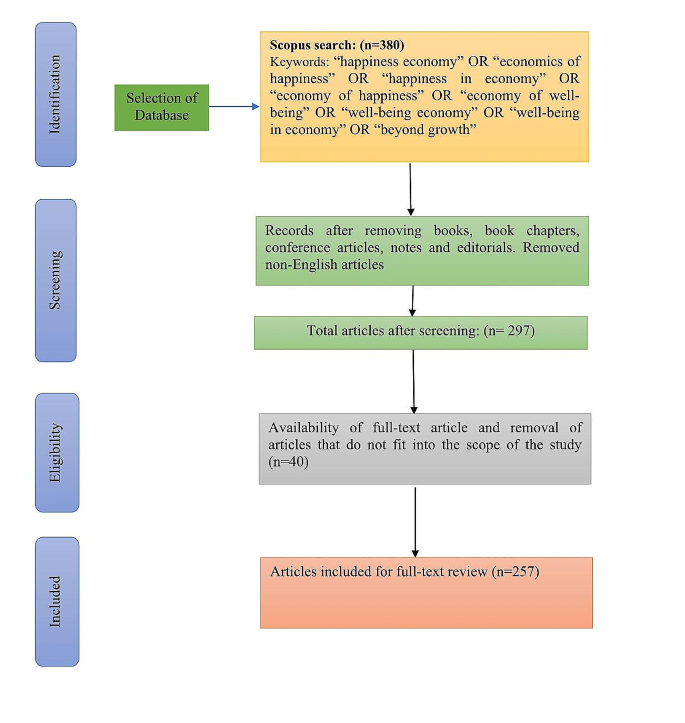

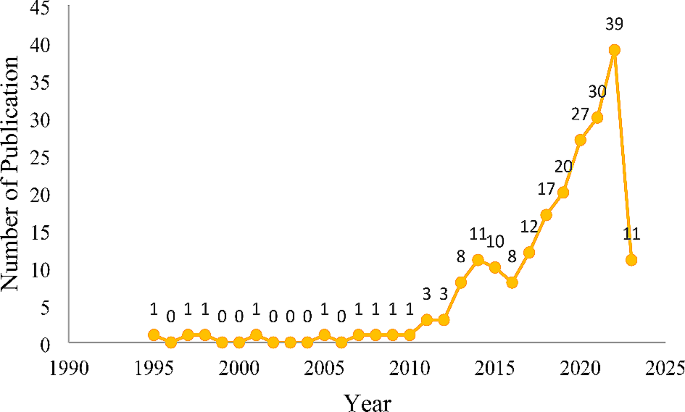

The pursuit of happiness has been an essential goal of individuals and countries throughout history. In the past few years, researchers and academicians have developed a huge interest in the notion of a ‘happiness economy’ that aims to prioritize subjective well-being and life satisfaction over traditional economic indicators such as Gross Domestic Product (GDP). Over the past few years, many countries have adopted a happiness and well-being-oriented framework to re-design the welfare policies and assess environmental, social, economic, and sustainable progress. Such a policy framework focuses on human and planetary well-being instead of material growth and income. The present study offers a comprehensive summary of the existing studies on the subject, exploring how a happiness economy framework can help achieve sustainable development. For this purpose, a systematic literature review (SLR) summarised 257 research publications from 1995 to 2023. The review yielded five major thematic clusters, namely- (i) Going beyond GDP: Transition towards happiness economy, (ii) Rethinking growth for sustainability and ecological regeneration, (iii) Beyond money and happiness policy, (iv) Health, human capital and wellbeing and (v) Policy push for happiness economy. Furthermore, the study proposes future research directions to help researchers and policymakers build a happiness economy framework.

Similar content being viewed by others

Beyond GDP: A Movement Toward Happiness Economy to Achieve Sustainability

National progress, sustainability and higher goals: the case of Bhutan’s Gross National Happiness

Economic Performance, Happiness, and Sustainable Development in OECD Countries

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Happiness is considered the ultimate goal of human beings (Ikeda, 2010 ; Lama, 2012 ). All economic, social, environmental and political human activities are aligned towards achieving this goal. This fundamental pursuit of human life introduces a new scope of research, namely the ‘happiness economy’ (Agrawal and Sharma 2023 ). The happiness economy is an emerging economic domain wherein many countries are working to envision and implement a happiness-oriented framework by expanding how they measure economic success, which includes wellbeing and sustainability (Cook and Davíðsdóttir 2021 ; Forgeard et al., 2011 ). The investigation of happiness, life-satisfaction and subjective well-being has witnessed increasing research interest across the disciplines- from psychology, philosophy, psychiatry, and cognitive neuroscience to sociology, economics and management (Diener 1984 ; Hallberg and Kullenberg, 2019 ).

In the post-Covid era, the world seeks an enormous transformation shift in the public system (Costanza 2020 ). However, public authorities need more time to realize such needs. To experience the ‘policy transformation’ within the coming few years, we require a paradigm shift that helps warm peoples’ hearts and minds. The new economic paradigm can penetrate the policy processes in advanced economies and every part of the world affected by the epidemic with the support of intellectuals, researchers, entrepreneurs and professionals.