The Top Ten Most-Read Essays of 2021

In 2021, democracy’s fortunes were tested, and a tumultuous world became even more turbulent. Democratic setbacks arose in places as far flung as Burma, El Salvador, Tunisia, and Sudan, and a 20-year experiment in Afghanistan collapsed in days. The world’s democracies were beset by rising polarization, and people watched in shock as an insurrection took place in the United States. In a year marked by high political drama, economic unrest, and rising assaults on democracy, we at the Journal of Democracy sought to provide insight and analysis of the forces that imperil freedom. Here are our 10 most-read essays of 2021:

Manuel Meléndez-Sánchez Nayib Bukele has developed a blend of political tactics that combines populist appeals and classic autocratic behavior with a polished social-media brand. It poses a dire threat to the country’s democratic institutions.

The best free cultural &

educational media on the web

- Online Courses

- Certificates

- Degrees & Mini-Degrees

- Audio Books

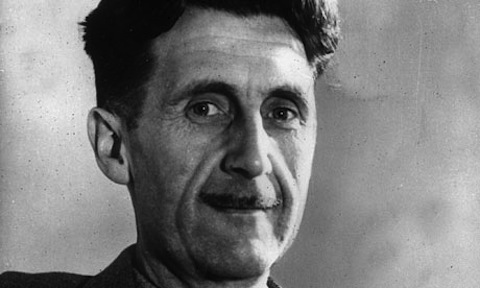

George Orwell’s Five Greatest Essays (as Selected by Pulitzer-Prize Winning Columnist Michael Hiltzik)

in English Language , Literature , Politics | November 12th, 2013 8 Comments

Every time I’ve taught George Orwell’s famous 1946 essay on misleading, smudgy writing, “ Politics and the English Language ,” to a group of undergraduates, we’ve delighted in pointing out the number of times Orwell violates his own rules—indulges some form of vague, “pretentious” diction, slips into unnecessary passive voice, etc. It’s a petty exercise, and Orwell himself provides an escape clause for his list of rules for writing clear English: “Break any of these rules sooner than say anything outright barbarous.” But it has made us all feel slightly better for having our writing crutches pushed out from under us.

Orwell’s essay, writes the L.A. Times ’ Pulitzer-Prize winning columnist Michael Hiltzik , “stands as the finest deconstruction of slovenly writing since Mark Twain’s “ Fenimore Cooper’s Literary Offenses .” Where Twain’s essay takes on a pretentious academic establishment that unthinkingly elevates bad writing, “Orwell makes the connection between degraded language and political deceit (at both ends of the political spectrum).” With this concise description, Hiltzik begins his list of Orwell’s five greatest essays, each one a bulwark against some form of empty political language, and the often brutal effects of its “pure wind.”

One specific example of the latter comes next on Hiltzak’s list (actually a series he has published over the month) in Orwell’s 1949 essay on Gandhi. The piece clearly names the abuses of the imperial British occupiers of India, even as it struggles against the canonization of Gandhi the man, concluding equivocally that “his character was extraordinarily a mixed one, but there was almost nothing in it that you can put your finger on and call bad.” Orwell is less ambivalent in Hiltzak’s third choice , the spiky 1946 defense of English comic writer P.G. Wodehouse , whose behavior after his capture during the Second World War understandably baffled and incensed the British public. The last two essays on the list, “ You and the Atomic Bomb ” from 1945 and the early “ A Hanging ,” published in 1931, round out Orwell’s pre- and post-war writing as a polemicist and clear-sighted political writer of conviction. Find all five essays free online at the links below. And find some of Orwell’s greatest works in our collection of Free eBooks .

1. “ Politics and the English Language ”

2. “ Reflections on Gandhi ”

3. “ In Defense of P.G. Wodehouse ”

4. “ You and the Atomic Bomb ”

5. “ A Hanging ”

Related Content:

George Orwell’s 1984: Free eBook, Audio Book & Study Resources

The Only Known Footage of George Orwell (Circa 1921)

George Orwell and Douglas Adams Explain How to Make a Proper Cup of Tea

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

by Josh Jones | Permalink | Comments (8) |

Related posts:

Comments (8), 8 comments so far.

You can’t go wrong with Orwell, so I feel bad about complaining. But how is “Shooting an Elephant” not on here?!?!

YES. Totally agree!

And “Down and Out in Paris and London” is one of the best comments on homelessness EVER!

Good article. In this selection of essays, he ranges from reflections on his boyhood schooling and the profession of writing to his views on the Spanish Civil War and British imperialism. The pieces collected here include the relatively unfamiliar and the more celebrated, making it an ideal compilation for both new and dedicated readers of Orwell’s work.nnhttp://essay-writing-company-reviews.essayboards.com/

Very thought provoking

i am crudbutt

i am crudbutt!

I think Orwell would have been irritated at your use of how instead of why.

Add a comment

Leave a reply.

Name (required)

Email (required)

XHTML: You can use these tags: <a href="" title=""> <abbr title=""> <acronym title=""> <b> <blockquote cite=""> <cite> <code> <del datetime=""> <em> <i> <q cite=""> <s> <strike> <strong>

Click here to cancel reply.

- 1,700 Free Online Courses

- 200 Online Certificate Programs

- 100+ Online Degree & Mini-Degree Programs

- 1,150 Free Movies

- 1,000 Free Audio Books

- 150+ Best Podcasts

- 800 Free eBooks

- 200 Free Textbooks

- 300 Free Language Lessons

- 150 Free Business Courses

- Free K-12 Education

- Get Our Daily Email

Free Courses

- Art & Art History

- Classics/Ancient World

- Computer Science

- Data Science

- Engineering

- Environment

- Political Science

- Writing & Journalism

- All 1500 Free Courses

- 1000+ MOOCs & Certificate Courses

Receive our Daily Email

Free updates, get our daily email.

Get the best cultural and educational resources on the web curated for you in a daily email. We never spam. Unsubscribe at any time.

FOLLOW ON SOCIAL MEDIA

Free Movies

- 1150 Free Movies Online

- Free Film Noir

- Silent Films

- Documentaries

- Martial Arts/Kung Fu

- Free Hitchcock Films

- Free Charlie Chaplin

- Free John Wayne Movies

- Free Tarkovsky Films

- Free Dziga Vertov

- Free Oscar Winners

- Free Language Lessons

- All Languages

Free eBooks

- 700 Free eBooks

- Free Philosophy eBooks

- The Harvard Classics

- Philip K. Dick Stories

- Neil Gaiman Stories

- David Foster Wallace Stories & Essays

- Hemingway Stories

- Great Gatsby & Other Fitzgerald Novels

- HP Lovecraft

- Edgar Allan Poe

- Free Alice Munro Stories

- Jennifer Egan Stories

- George Saunders Stories

- Hunter S. Thompson Essays

- Joan Didion Essays

- Gabriel Garcia Marquez Stories

- David Sedaris Stories

- Stephen King

- Golden Age Comics

- Free Books by UC Press

- Life Changing Books

Free Audio Books

- 700 Free Audio Books

- Free Audio Books: Fiction

- Free Audio Books: Poetry

- Free Audio Books: Non-Fiction

Free Textbooks

- Free Physics Textbooks

- Free Computer Science Textbooks

- Free Math Textbooks

K-12 Resources

- Free Video Lessons

- Web Resources by Subject

- Quality YouTube Channels

- Teacher Resources

- All Free Kids Resources

Free Art & Images

- All Art Images & Books

- The Rijksmuseum

- Smithsonian

- The Guggenheim

- The National Gallery

- The Whitney

- LA County Museum

- Stanford University

- British Library

- Google Art Project

- French Revolution

- Getty Images

- Guggenheim Art Books

- Met Art Books

- Getty Art Books

- New York Public Library Maps

- Museum of New Zealand

- Smarthistory

- Coloring Books

- All Bach Organ Works

- All of Bach

- 80,000 Classical Music Scores

- Free Classical Music

- Live Classical Music

- 9,000 Grateful Dead Concerts

- Alan Lomax Blues & Folk Archive

Writing Tips

- William Zinsser

- Kurt Vonnegut

- Toni Morrison

- Margaret Atwood

- David Ogilvy

- Billy Wilder

- All posts by date

Personal Finance

- Open Personal Finance

- Amazon Kindle

- Architecture

- Artificial Intelligence

- Beat & Tweets

- Comics/Cartoons

- Current Affairs

- English Language

- Entrepreneurship

- Food & Drink

- Graduation Speech

- How to Learn for Free

- Internet Archive

- Language Lessons

- Most Popular

- Neuroscience

- Photography

- Pretty Much Pop

- Productivity

- UC Berkeley

- Uncategorized

- Video - Arts & Culture

- Video - Politics/Society

- Video - Science

- Video Games

Great Lectures

- Michel Foucault

- Sun Ra at UC Berkeley

- Richard Feynman

- Joseph Campbell

- Jorge Luis Borges

- Leonard Bernstein

- Richard Dawkins

- Buckminster Fuller

- Walter Kaufmann on Existentialism

- Jacques Lacan

- Roland Barthes

- Nobel Lectures by Writers

- Bertrand Russell

- Oxford Philosophy Lectures

Receive our newsletter!

Open Culture scours the web for the best educational media. We find the free courses and audio books you need, the language lessons & educational videos you want, and plenty of enlightenment in between.

Great Recordings

- T.S. Eliot Reads Waste Land

- Sylvia Plath - Ariel

- Joyce Reads Ulysses

- Joyce - Finnegans Wake

- Patti Smith Reads Virginia Woolf

- Albert Einstein

- Charles Bukowski

- Bill Murray

- Fitzgerald Reads Shakespeare

- William Faulkner

- Flannery O'Connor

- Tolkien - The Hobbit

- Allen Ginsberg - Howl

- Dylan Thomas

- Anne Sexton

- John Cheever

- David Foster Wallace

Book Lists By

- Neil deGrasse Tyson

- Ernest Hemingway

- F. Scott Fitzgerald

- Allen Ginsberg

- Patti Smith

- Henry Miller

- Christopher Hitchens

- Joseph Brodsky

- Donald Barthelme

- David Bowie

- Samuel Beckett

- Art Garfunkel

- Marilyn Monroe

- Picks by Female Creatives

- Zadie Smith & Gary Shteyngart

- Lynda Barry

Favorite Movies

- Kurosawa's 100

- David Lynch

- Werner Herzog

- Woody Allen

- Wes Anderson

- Luis Buñuel

- Roger Ebert

- Susan Sontag

- Scorsese Foreign Films

- Philosophy Films

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- February 2011

- January 2011

- December 2010

- November 2010

- October 2010

- September 2010

- August 2010

- February 2010

- January 2010

- December 2009

- November 2009

- October 2009

- September 2009

- August 2009

- February 2009

- January 2009

- December 2008

- November 2008

- October 2008

- September 2008

- August 2008

- February 2008

- January 2008

- December 2007

- November 2007

- October 2007

- September 2007

- August 2007

- February 2007

- January 2007

- December 2006

- November 2006

- October 2006

- September 2006

©2006-2024 Open Culture, LLC. All rights reserved.

- Advertise with Us

- Copyright Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Use

click here to read it now

Read this week's magazine

The Top 10 Essays Since 1950

Robert Atwan, the founder of The Best American Essays series, picks the 10 best essays of the postwar period. Links to the essays are provided when available.

Fortunately, when I worked with Joyce Carol Oates on The Best American Essays of the Century (that’s the last century, by the way), we weren’t restricted to ten selections. So to make my list of the top ten essays since 1950 less impossible, I decided to exclude all the great examples of New Journalism--Tom Wolfe, Gay Talese, Michael Herr, and many others can be reserved for another list. I also decided to include only American writers, so such outstanding English-language essayists as Chris Arthur and Tim Robinson are missing, though they have appeared in The Best American Essays series. And I selected essays , not essayists . A list of the top ten essayists since 1950 would feature some different writers.

To my mind, the best essays are deeply personal (that doesn’t necessarily mean autobiographical) and deeply engaged with issues and ideas. And the best essays show that the name of the genre is also a verb, so they demonstrate a mind in process--reflecting, trying-out, essaying.

James Baldwin, "Notes of a Native Son" (originally appeared in Harper’s , 1955)

“I had never thought of myself as an essayist,” wrote James Baldwin, who was finishing his novel Giovanni’s Room while he worked on what would become one of the great American essays. Against a violent historical background, Baldwin recalls his deeply troubled relationship with his father and explores his growing awareness of himself as a black American. Some today may question the relevance of the essay in our brave new “post-racial” world, though Baldwin considered the essay still relevant in 1984 and, had he lived to see it, the election of Barak Obama may not have changed his mind. However you view the racial politics, the prose is undeniably hypnotic, beautifully modulated and yet full of urgency. Langston Hughes nailed it when he described Baldwin’s “illuminating intensity.” The essay was collected in Notes of a Native Son courageously (at the time) published by Beacon Press in 1955.

Norman Mailer, "The White Negro" (originally appeared in Dissent , 1957)

An essay that packed an enormous wallop at the time may make some of us cringe today with its hyperbolic dialectics and hyperventilated metaphysics. But Mailer’s attempt to define the “hipster”–in what reads in part like a prose version of Ginsberg’s “Howl”–is suddenly relevant again, as new essays keep appearing with a similar definitional purpose, though no one would mistake Mailer’s hipster (“a philosophical psychopath”) for the ones we now find in Mailer’s old Brooklyn neighborhoods. Odd, how terms can bounce back into life with an entirely different set of connotations. What might Mailer call the new hipsters? Squares?

Read the essay here .

Susan Sontag, "Notes on 'Camp'" (originally appeared in Partisan Review , 1964)

Like Mailer’s “White Negro,” Sontag’s groundbreaking essay was an ambitious attempt to define a modern sensibility, in this case “camp,” a word that was then almost exclusively associated with the gay world. I was familiar with it as an undergraduate, hearing it used often by a set of friends, department store window decorators in Manhattan. Before I heard Sontag—thirty-one, glamorous, dressed entirely in black-- read the essay on publication at a Partisan Review gathering, I had simply interpreted “campy” as an exaggerated style or over-the-top behavior. But after Sontag unpacked the concept, with the help of Oscar Wilde, I began to see the cultural world in a different light. “The whole point of camp,” she writes, “is to dethrone the serious.” Her essay, collected in Against Interpretation (1966), is not in itself an example of camp.

John McPhee, "The Search for Marvin Gardens" (originally appeared in The New Yorker , 1972)

“Go. I roll the dice—a six and a two. Through the air I move my token, the flatiron, to Vermont Avenue, where dog packs range.” And so we move, in this brilliantly conceived essay, from a series of Monopoly games to a decaying Atlantic City, the once renowned resort town that inspired America’s most popular board game. As the games progress and as properties are rapidly snapped up, McPhee juxtaposes the well-known sites on the board—Atlantic Avenue, Park Place—with actual visits to their crumbling locations. He goes to jail, not just in the game but in fact, portraying what life has now become in a city that in better days was a Boardwalk Empire. At essay’s end, he finds the elusive Marvin Gardens. The essay was collected in Pieces of the Frame (1975).

Read the essay here (subscription required).

Joan Didion, "The White Album" (originally appeared in New West , 1979)

Huey Newton, Eldridge Cleaver, and the Black Panthers, a recording session with Jim Morrison and the Doors, the San Francisco State riots, the Manson murders—all of these, and much more, figure prominently in Didion’s brilliant mosaic distillation (or phantasmagoric album) of California life in the late 1960s. Yet despite a cast of characters larger than most Hollywood epics, “The White Album” is a highly personal essay, right down to Didion’s report of her psychiatric tests as an outpatient in a Santa Monica hospital in the summer of 1968. “We tell ourselves stories in order to live,” the essay famously begins, and as it progresses nervously through cuts and flashes of reportage, with transcripts, interviews, and testimonies, we realize that all of our stories are questionable, “the imposition of a narrative line upon disparate images.” Portions of the essay appeared in installments in 1968-69 but it wasn’t until 1979 that Didion published the complete essay in New West magazine; it then became the lead essay of her book, The White Album (1979).

Annie Dillard, "Total Eclipse" (originally appeared in Antaeus , 1982)

In her introduction to The Best American Essays 1988 , Annie Dillard claims that “The essay can do everything a poem can do, and everything a short story can do—everything but fake it.” Her essay “Total Eclipse” easily makes her case for the imaginative power of a genre that is still undervalued as a branch of imaginative literature. “Total Eclipse” has it all—the climactic intensity of short fiction, the interwoven imagery of poetry, and the meditative dynamics of the personal essay: “This was the universe about which we have read so much and never before felt: the universe as a clockwork of loose spheres flung at stupefying, unauthorized speeds.” The essay, which first appeared in Antaeus in 1982 was collected in Teaching a Stone to Talk (1982), a slim volume that ranks among the best essay collections of the past fifty years.

Phillip Lopate, "Against Joie de Vivre" (originally appeared in Ploughshares , 1986)

This is an essay that made me glad I’d started The Best American Essays the year before. I’d been looking for essays that grew out of a vibrant Montaignean spirit—personal essays that were witty, conversational, reflective, confessional, and yet always about something worth discussing. And here was exactly what I’d been looking for. I might have found such writing several decades earlier but in the 80s it was relatively rare; Lopate had found a creative way to insert the old familiar essay into the contemporary world: “Over the years,” Lopate begins, “I have developed a distaste for the spectacle of joie de vivre , the knack of knowing how to live.” He goes on to dissect in comic yet astute detail the rituals of the modern dinner party. The essay was selected by Gay Talese for The Best American Essays 1987 and collected in Against Joie de Vivre in 1989 .

Edward Hoagland, "Heaven and Nature" (originally appeared in Harper’s, 1988)

“The best essayist of my generation,” is how John Updike described Edward Hoagland, who must be one of the most prolific essayists of our time as well. “Essays,” Hoagland wrote, “are how we speak to one another in print—caroming thoughts not merely in order to convey a certain packet of information, but with a special edge or bounce of personal character in a kind of public letter.” I could easily have selected many other Hoagland essays for this list (such as “The Courage of Turtles”), but I’m especially fond of “Heaven and Nature,” which shows Hoagland at his best, balancing the public and private, the well-crafted general observation with the clinching vivid example. The essay, selected by Geoffrey Wolff for The Best American Essays 1989 and collected in Heart’s Desire (1988), is an unforgettable meditation not so much on suicide as on how we remarkably manage to stay alive.

Jo Ann Beard, "The Fourth State of Matter" (originally appeared in The New Yorker , 1996)

A question for nonfiction writing students: When writing a true story based on actual events, how does the narrator create dramatic tension when most readers can be expected to know what happens in the end? To see how skillfully this can be done turn to Jo Ann Beard’s astonishing personal story about a graduate student’s murderous rampage on the University of Iowa campus in 1991. “Plasma is the fourth state of matter,” writes Beard, who worked in the U of I’s physics department at the time of the incident, “You’ve got your solid, your liquid, your gas, and there’s your plasma. In outer space there’s the plasmasphere and the plasmapause.” Besides plasma, in this emotion-packed essay you will find entangled in all the tension a lovable, dying collie, invasive squirrels, an estranged husband, the seriously disturbed gunman, and his victims, one of them among the author’s dearest friends. Selected by Ian Frazier for The Best American Essays 1997 , the essay was collected in Beard’s award-winning volume, The Boys of My Youth (1998).

David Foster Wallace, "Consider the Lobster" (originally appeared in Gourmet , 2004)

They may at first look like magazine articles—those factually-driven, expansive pieces on the Illinois State Fair, a luxury cruise ship, the adult video awards, or John McCain’s 2000 presidential campaign—but once you uncover the disguise and get inside them you are in the midst of essayistic genius. One of David Foster Wallace’s shortest and most essayistic is his “coverage” of the annual Maine Lobster Festival, “Consider the Lobster.” The Festival becomes much more than an occasion to observe “the World’s Largest Lobster Cooker” in action as Wallace poses an uncomfortable question to readers of the upscale food magazine: “Is it all right to boil a sentient creature alive just for our gustatory pleasure?” Don’t gloss over the footnotes. Susan Orlean selected the essay for The Best American Essays 2004 and Wallace collected it in Consider the Lobster and Other Essays (2005).

Read the essay here . (Note: the electronic version from Gourmet magazine’s archives differs from the essay that appears in The Best American Essays and in his book, Consider the Lobster. )

I wish I could include twenty more essays but these ten in themselves comprise a wonderful and wide-ranging mini-anthology, one that showcases some of the most outstanding literary voices of our time. Readers who’d like to see more of the best essays since 1950 should take a look at The Best American Essays of the Century (2000).

- You are a subscriber but you have not yet set up your account for premium online access. Contact customer service (see details below) to add your preferred email address and password to your account.

- You forgot your password and you need to retrieve it. Click here to retrieve reset your password.

- Your company has a site license, use our easy login. Enter your work email address in the Site License Portal.

Major Political Thinkers: Plato to Mill

An annotated guide to the major political thinkers from Plato to John Stuart Mill with a brief description of why their work is important and links to the recommended texts, and other readings.

The Author : Quentin Taylor is Professor of History and Political Science at Rogers State University. He has written widely on the political classics from Plato to Rawls.

A Guide to the "Major Political Thinkers: Plato to Mill", by Quentin Taylor

Introduction.

- Collections: Books on Political Theory

- Exploring Ideas: Readings on Political Thought

- Quotations about Liberty and Power

- Liberty Matters Online Forum

Political speculation in the West is as old as the Western tradition itself. Its origins may be traced as far back as Homer, but its foundations were laid by Plato and Aristotle. While many of the questions asked by political thinkers have remained the same —what is justice? — the answers have varied considerably over the last 2,400 years. The following selections represent the principal works of the major political philosophers, from the ancient Greeks and Romans to the mid-nineteenth century.

- Collections: The American Founding Fathers

The American Founders were familiar with the names of all these thinkers (except Mill) and had read many of their works, as evidenced by their own libraries and papers. For a list of the most frequently read political authors of the Founding Era, see Donald Lutz and for an essay on the “ Founding Father’s Library ,” see Forrest McDonald.

Plato (427 BC-347 BC) The Republic

As the first philosophical examination of “justice” in Western literature, the Republic occupies a seminal place in the history of political thought. Written in the form of a dialogue, Plato employs Socrates as a kind of discussion leader who seeks to discover justice in the individual by defining justice in the state. This discursive search leads Socrates-cum-Plato to reach some rather unexpected conclusions and to embrace some unconventional social practices and political arrangements, including the rule of philosophers. In addition to outlining the ideal state, Plato explores “corrupt” or “deviant” regimes (timarchy, oligarchy, democracy, and tyranny) through an analysis of their leading symptoms and psychological foundations. While often denounced as an enemy of the “open society,” Plato challenges us to reexamine prevailing orthodoxies and reconsider the higher purposes of community.

Plato, "The Republic" in The Dialogues of Plato translated into English with Analyses and Introductions by B. Jowett, M.A. in Five Volumes . 3rd edition revised and corrected (Oxford University Press, 1892). 8/14/2014. < /titles/767#lf0131-03_head_001 >. The text is in the public domain.

Plato (427-347 BC) The Statesman

In the Republic , Plato suggests that ruling is a kind of science or craft and concludes that only those trained in this craft should be permitted to govern. In the Statesman , he attempts to carefully define this “royal science” and distinguish it from other activities. In the process a new element is introduced — adherence to law — which becomes the basis for evaluating good and bad forms of regime types (e.g., monarchy vs. tyranny). Those regimes which follow the law — although inferior to the untrammeled rule of true philosophers — are far better than those that do not. With this concession to non-ideal forms of government, Plato foreshadows his abandonment of philosophic rule in the Republic in favor of the “second-best” state of the Laws .

Plato, "The Statesman" in The Dialogues of Plato translated into English with Analyses and Introductions by B. Jowett, M.A. in Five Volumes. 3rd edition revised and corrected (Oxford University Press, 1892). 8/14/2014. < /titles/768#lf0131-04_head_016 >. The text is in the public domain.

Plato (427-347) The Laws

His last and longest dialogue, the Laws is Plato’s most important contribution to legal and political science. In the form of a discussion between an Athenian, a Spartan, and a Cretan, Plato outlines the “second-best” state (the “law state”) in painstaking detail. While retaining some of the idealism of the Republic , the Laws aims at a more realizable goal, a community based on the principle of moderation. Accordingly, Plato replaces the communal living arrangements of the Republic with private property and permits citizens a voice in the management of public affairs. He also prefigures the famous “mixed” or “balanced” constitution, observing that democracy should be tempered with monarchy. His provisions for making, revising, and teaching the laws is a tacit admission that the “royal science” of philosophers must give way to known and settled rules. Similarly, Plato’s interest in existing institutions and appreciation for imperfect regimes serves as a bridge to the more empirical and realistic politics of Aristotle.

Plato, "The Laws" in The Dialogues of Plato translated into English with Analyses and Introductions by B. Jowett, M.A. in Five Volumes. 3rd edition revised and corrected (Oxford University Press, 1892). 8/14/2014. < /titles/769#lf0131-05_head_018 >. The text is in the public domain.

Aristotle (384-322 BC) The Politics

Like his teacher Plato, Aristotle was interested in the nature of the political as such and deeply normative in his approach to politics. He was, however, more empirical and scientific in his method, writing treatises instead of dialogues and often handling his materials with considerable detachment. The result in the Politics is a far-reaching and often penetrating treatment of political life, from the origins and purpose of the state to the nuances of institutional arrangements. While Aristotle’s remarks on slavery, women, and laborers are often embarrassing to modern readers, his analysis of regime types (including the causes of their preservation and destruction) remains of perennial interest. His discussion of “polity”— a fusion of oligarchy and democracy — has been of particular significance in the history of popular government. Finally, his contention that a constitution is more than a set of political institutions, but also embodies a shared way of life, has proved a fruitful insight in the hands of subsequent thinkers such as Alexis de Tocqueville .

Aristotle, The Politics of Aristotle, trans. into English with introduction, marginal analysis, essays, notes and indices by B. Jowett. Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1885. 2 vols. Vol. 1. 8/14/2014. < /titles/579#lf0033-01_head_014 >. The text is in the public domain.

Cicero (106 BC-43 BC) The Laws (51 BC)

Statesman, orator, and philosopher Marcus Tullius Cicero became the most widely read and admired Roman author following the recovery of his major works during the Renaissance. Best known for his public orations, he also penned two theoretical works on politics, the Republic and the Laws . Cast in the form of dialogues, each work addresses several leading concerns of political life, e.g., the relation between liberty and equality, the nature of political leadership, and the interplay of institutions. The Laws is particuarly noteworthy for its treatment of Natural Law, which can be traced down through the centuries to our own day. (Echoes of Cicero may be found in such luminaries as Thomas Aquinas , John Locke , and Thomas Jefferson .) Regrettably, only a portion of the dialogue survives, yet its author’s reflections on law and public morality remain fresh and relevant.

Marcus Tullius Cicero, The Political Works of Marcus Tullius Cicero: Comprising his Treatise on the Commonwealth; and his Treatise on the Laws. Translated from the original, with Dissertations and Notes in Two Volumes. By Francis Barham, Esq. (London: Edmund Spettigue, 1841-42). Vol. 2. 8/14/2014. < /titles/545#lf0044-02_head_004 >. The text is in the public domain.

Cicero (106 BC-43 BC) The Republic (54 BC)

Like Plato’s dialogue of the same name, Cicero’s Republic embodies a comprehensive and ideal vision of political life. In addition to a search for justice, the discussants explore such foundational issues as the relation between the individual and the state, the qualities of the ideal statesman, and the nature of political knowledge. Additional themes include constitutional forms and their evolution, the social harmony of classes, and the influence of education on private morals and public virtue. Like the Laws , the Republic is a fragmentary work, but one that still resonates in the modern world.

Marcus Tullius Cicero, The Political Works of Marcus Tullius Cicero: Comprising his Treatise on the Commonwealth; and his Treatise on the Laws. Translated from the original, with Dissertations and Notes in Two Volumes. By Francis Barham, Esq . (London: Edmund Spettigue, 1841-42). Vol. 1. 8/14/2014. < /titles/546 >. The text is in the public domain.

Thomas Aquinas (c.1225-1274) On Law and Justice (1274)

St. Thomas Aquinas

The Online Library of Liberty hopes to add Thomas’s writings on law and justice in the near future.

St. Thomas Aquinas, Aquinas Ethicus: or, the Moral Teaching of St. Thomas. A Translation of the Principal Portions of the Second part of the Summa Theologica, with Notes by Joseph Rickaby, S.J. (London: Burns and Oates, 1892). 8/14/2014. < /titles/1967 >. The text is in the public domain.

Niccolo Machiavelli (1469-1527) The Prince (1513)

The Prince is at once the most famous and infamous work in the canon of political thought. Instead of considering questions of justice and the ideal state, Machiavelli proposed to advise a “new” prince on how to succesfully maintain power. Given the realities of human nature and politics, it is sometimes necessary for a prince to “do evil,” including acts of violence, deceit, and cruelty, in order to survive. For Machiavelli, the capacity for such acts is not an aberration of the political art, but an essential part of a ruler’s “skill set.” Such stark realism and the hard break with the Classical-Christian tradition has led many to denounce Machiavelli as an “immoralist,” an “advisor to tyrants,” and a “teacher of evil.” Others have defended the Prince for its author’s realistic appraisal of politics, shrewd psychological insights, and tough-minded advice for a dangerous world. This “little book” (as Machiavelli called it) will undoubtedly continue to provoke highly varied responses.

Niccolo Machiavelli, "The Prince" in The Historical, Political, and Diplomatic Writings of Niccolo Machiavelli, tr. from the Italian, by Christian E. Detmold (Boston, J. R. Osgood and company, 1882). Vol. 2. 8/14/2014. < /titles/775#lf0076-02_head_002 >. The text is in the public domain.

Niccolo Machiavelli (1469-1527) The Discourses (1513)

The Discourses on Livy is often described as Machiavelli’s “book on republics,” but this is not entirely accurate. He does focus on republics, ancient and modern, but he also discusses monarchies or princedoms. On the other hand, his advice in the Prince is often relevant to leaders of republics. There is, however, a tension between the republicanism of the Discourses and the autocracy of the Prince , for the same author who champions the cause of liberty and self-government in the former gives advice on preserving one-man rule in the latter. It is, however, possible to find a common thread in Machiavelli’s mode of analysis (realist and historical) and to view the Prince as a special instance of his political science and the Discourses as the core of this science, as well as the heart of his political creed. In recent years, it is the Machiavelli of the Discourses who has gained the attention (and often admiration) of scholars for reviving the republican tradition in the modern world.

Niccolo Machiavelli, "Discourses of the First Ten Books of Titus Livius" in The Historical, Political, and Diplomatic Writings of Niccolo Machiavelli, tr. from the Italian, by Christian E. Detmold (Boston, J. R. Osgood and company, 1882). Vol. 2. 8/14/2014. < /titles/775#lf0076-02_head_031 >. The text is in the public domain.

Thomas Hobbes (1588-1679) Leviathan (1651)

Best known as the “father” of modern absolutism, Hobbes is also credited as the “father” of modern political science. In Leviathan , his principal work, the English philosopher endeavored to establish a new “science of politics” on the basis of the first principles of human nature. While his conclusion — that without an all-powerful Sovereign life would be a “war of all against all” — was largely rejected by his contemporaries, the novelty of his method and his reliance on natural law inaugurated a new era in political thinking. His use of the “social contract” as a method of explaining the origin and legitimacy of public authority would be adopted to more liberal ends by thinkers such as Locke and Rousseau . Moreover, Hobbes’s contention that men possess “natural” rights — that by nature individuals are free, equal, and autonomous — readily lent itself to theories of limited government. For this reason, Hobbes is often identified, paradoxically, as the “father” of modern liberalism. See, in particular, chapters 13-31.

Thomas Hobbes, Hobbes’s Leviathan reprinted from the edition of 1651 with an Essay by the Late W.G. Pogson Smith (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1909). 8/14/2014. < /titles/869 >. The text is in the public domain.

Benedict de Spinoza (1632-1677) Political Treatise (1677)

Spinoza’s fame as a philosopher largely rests on his Ethics , but he also made an important, if rather engimatic, contribution to political thought. While employing much of the language and framework of natural rights thinkers, Spinoza rejected natural law as a regulative principle and adopted an entirely prudential approach to questions of civic formation, obligation, legitimacy, and freedom. Often described as a Hobbesian, Spinoza differs in important respects from his English predecessor. He advanced ideas of religious toleration and freedom of expression, held that peace was more than just the absence of war, and identified positive aspects in different forms of government. That he adopted these positions on pragmatic, rather than principled, grounds and denied inherent natural rights, places Spinoza outside the mainstream of modern liberalism, but he ultimately endorsed a relatively democratic and open society.

Benedict de Spinoza, "A Political Treatise" in The Chief Works of Benedict de Spinoza, translated from the Latin, with an Introduction by R.H.M. Elwes, vol. 1 Introduction, Tractatus-Theologico-Politicus, Tractatus Politicus. Revised edition (London: George Bell and Sons, 1891). 8/14/2014. < /titles/1710#lf1321-01_head_042 >. The text is in the public domain.

John Locke (1632-1704) Second Treatise of Government (1690)

Few political thinkers have had such a profound and lasting influence as John Locke . His Second Treatise , written against the backdrop of political crisis and revolution, contains classic arguments against arbitrary and despotic government. Drawing on the tradition of natural law, Locke developed a theory of natural liberty that placed limits on civil authority. For Locke, government is founded in human need and arises from “inconveniences” in the “state of nature.” Like Hobbes , he finds the origins of political authority in the “social contract,” a voluntary agreement to enter into civil society. Unlike Hobbes, however, the sovereignty of the people is not permanently transferred to an absolute “Sovereign,” but is temporarily delegated to a government of limited power. Locke’s Second Treatise also made important contributions to the concepts of equality, rule of law, separation of powers, majoritarianism, and the right to revolution. Along with its theory of (private) property, the Second Treatise remains the seminal text of classical liberalism.

For additional reading see Eric Mack’s Introduction to the Political Thought of John Locke (in particular his Second Treatise of Government ).

John Locke, Two Treatises of Government , ed. Thomas Hollis (London: A. Millar et al., 1764). 8/14/2014. < /titles/222#lf0057_head_018 >. The text is in the public domain.

David Hume (1711-1776) Political Essays (1741, 1752)

Unlike Hobbes and Locke, Hume’s reputation as a major political thinker does not rest on a single systematic treastise, but rather on a series of topical essays. Hume also diverged from his English predecesors in his approach to politics, adopting a less abstract and more historical perspective. This led Hume to reject the idea of the social contract as an ahistorical fiction of dubious value: utility and interest are the mainsprings of government and the bases of community. In the Essays , Hume addresses many of the leading themes of political reflection, including property, obligation, liberty, and the forms of goverment. His essays on money, taxes, and commerce did much to establish modern political economy, and anticipated the doctrines of Hume’s friend, Adam Smith . His remarks on political parties and the balancing of opposed interests are believed to have significantly influenced James Madison , whose famous treatment of factions in Federalist 10 has a distinct Humean ring. See, especially, Part One, Essays 2-9, 12 and all of Part Two.

David Hume, "Foreword" in Essays Moral, Political, Literary, edited and with a Foreword, Notes, and Glossary by Eugene F. Miller, with an appendix of variant readings from the 1889 edition by T.H. Green and T.H. Grose, revised edition (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund 1987). 8/14/2014. < /titles/704#lf0059_head_001 >. The copyright to this edition, in both print and electronic forms, is held by Liberty Fund, Inc.

Montesquieu (1689-1755) The Spirit of the Laws (1748)

Like Hume, Montesquieu’s approach to political thinking was historical, and his aim was less to construct a political theory than to understand law, liberty, and government in their various relations. In the Spirit of the Laws , Montesquieu explores these relations in great detail, considering the effects of climate, commerce, religion, and the family. This attention to the influence of social factors on law and government has led modern scholars to call him the “father” of sociology. Montesqueiu also engaged in the more conventional practice of regime analysis, with particular emphasis on the conditions that support political liberty. He is best known, however, for his discussion of the English constitution, his model of a modern free government. For Montesquieu, English liberty is the product of a balanced constitution, and specifically the separation of legislative and executive power. These reflections, as well as his observations on the conditions which support republics, would exercise a powerful influence on the American Founders, who appealed to Montesquieu — “that great man” — with considerable frequency. See in particular, Books 1-5 and 11.

Charles Louis de Secondat, "The Spirit of the Laws" in Baron de Montesquieu, The Complete Works of M. de Montesquieu (London: T. Evans, 1777), 4 vols. Vol. 1.8/14/2014. < /titles/837 >. The text is in the public domain.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712-1778) The Social Contract (1762)

“Man was born free, and he is everywhere in chains.” Thus begins the Social Contract , Rousseau’s principal work of political thought. Like Hobbes and Locke , Rousseau made use of the “social contract” to explain the origins of civil society, but in his version sovereignty is neither transferred nor delegated to the government, but remains with the people collectively. In Rousseau’s ideal republic, the citizens legislate directly in accordance with the “general will,” the common good. To recognize this good, citizens must be trained in virtue and roughly similar in circumstances. Only then will they be fit for self-government; only then will they be truly free. Rousseau’s model of a small city-state was out of step with the times, but his general ideas on liberty, equality, and democracy were highly influential. His treatment of these themes, however, is not without paradox, for there is a tendency toward collectivism and orthodoxy in many of his prescriptions. This aside, the Social Contract continues to inform debates over civic virtue and popular democracy, as well as present-day efforts to reconcile liberty, equality, and order.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau, "The Social Contract" in Ideal Empires and Republics. Rousseau’s Social Contract, More’s Utopia, Bacon’s New Atlantis, Campanella’s City of the Sun, with an Introduction by Charles M. Andrews (Washington: M. Walter Dunne, 1901). 8/14/2014. < /titles/2039#lf1414_head_004 >. The text is in the public domain.

Hamilton (1757-1804), Madison (1751-1836), and Jay (1745-1829) The Federalist (1788)

Begun as a series of newspaper articles, the Federalist papers were written under the pseudonym “Publius” in defense of the proposed Constitution drafted in the summer of 1787. In the process of answering the critics, Publius provided a thorough and far-ranging account of how the envisioned federal republic would secure order, protect liberty, and produce prosperity. Central to this account was a discussion of those “auxiliary precautions” or institutional safeguards that in the absence of “better motives” would serve to “counteract ambition.” Such “inventions of prudence” were required to preserve liberty and insure the stability of popular government. While written for a specific purpose — the Constitution’s adoption — the Federalist often soars above the immediate context to touch on the perennial themes of politics, making it the one great classic of American political thought. See, in particular, No. 10 (faction and the extended republic), No. 39 (republicanism and federalism), No. 51 (separation of powers and checks and balances), and No. 78 (judicial review).

George W. Carey, The Federalist (The Gideon Edition), Edited with an Introduction, Reader’s Guide, Constitutional Cross-reference, Index, and Glossary by George W. Carey and James McClellan (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 2001). 8/14/2014. < /titles/788 >. The copyright to this edition, in both print and electronic forms, is held by Liberty Fund, Inc.

Edmund Burke (1729-1797) Reflections on the Revolution in France (1790)

Had Burke never penned the Reflections on the Revolution in France , he might be best remembered as the British politician who defended the rights and liberties of the American colonists. As it is, Burke is best known as an apostle of order, tradition, and authority; indeed, as the “father” of modern conservatism. Writing in response to the outbreak of the French Revolution, Burke predicted that the attempt to remodel French society and government on the basis of abstract notions, such as the “rights of man,” would end in disaster. His warning was not so much directed at the French as his own countrymen, some of whom were drawing inspiration from events in France to initiate reform in Britain. In the process of excoriating the leaders of the Revolution and their “preposterous way of reasoning,” Burke addressed the central questions of political speculation, arriving at general principles by way of history, human nature, and circumstances. If his conclusions appeared reactionary to many, his approach to the social order, with its emphasis on prudence, utility, and prescription, reflects a depth and subtlety that has few rivals in the history of political thought.

For additional reading see the Debate about the French Revolution .

Edmund Burke,"Reflections on the Revolution in France" in Select Works of Edmund Burke. A New Imprint of the Payne Edition. Foreword and Biographical Note by Francis Canavan (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 1999). Vol. 2. 8/14/2014. < /titles/656 >. The copyright to this edition, in both print and electronic forms, is held by Liberty Fund, Inc.

John Stuart Mill (1806-1873) On Liberty (1859)

A century-and-a-half after its appearance, On Liberty remains the classic defense of individual freedom and the open society. For Mill , human happiness — the “greatest good” — is only possible in a free society where individuals are at liberty to make decisions about their lives. These decisions, including what to think, say, read, and write, should be free from state interference and left to the discretion of individuals. Believing that discussion, debate, and diversity were essential to the progress of society, Mill called for the widest degree of latitude for individual expression and even encouraged “experiments in living.” As long as people respect the rights of others, they should be allowed to think and live as they choose. Some beliefs and ways of living might be better than others, but it was not the proper role of the state to regulate such matters. Unlike classial liberals, Mill did not base his argument for liberty on natural right, but on utility or the “greatest happiness” principle. While this led him into some curious paradoxes, his strong defense of individual liberty and self-determination place him in the vanguard of liberal thinkers.

John Stuart Mill, "On Liberty" in The Collected Works of John Stuart Mill, Volume XVIII - Essays on Politics and Society Part I, ed. John M. Robson, Introduction by Alexander Brady (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1977). 8/14/2014. < /titles/233#lf0223-18_head_051 >. The online edition of the Collected Works is published under licence from the copyright holder, The University of Toronto Press. ©2006 The University of Toronto Press. All rights reserved. No part of this material may be reproduced in any form or medium without the permission of The University of Toronto Press.

John Stuart Mill (1806-1873) Considerations of Representative Government (1861)

Considerations on Representative Government is sometimes characterized as the mold into which Mill poured the principles contained in On Liberty . With the belief that a government is never neutral in its effects, Mill proposed a number of broad reforms designed to better represent the electorate, improve the quality of representatives, and give experts a dominant role in legislating. If not exactly “illiberal,” a number of his proposals are less than democratic, even by the standards of the day. Basically, Mill envisioned an administrative state in which an elite bureaucracy would govern with the advice and consent of the legislature, whose principal function was to serve as a check on the executive. He did embrace popular government for its tendency to galvanize the energies of the people as well as encourage self-reliance and public- spiritedness. For Mill some type of high-toned republic represents the ideal. He did not, however, believe this model was suitable for less advanced peoples, whose level of development might require more autocratic methods.

John Stuart Mill, "Considerations of Representative Government" in The Collected Works of John Stuart Mill, Volume XIX - Essays on Politics and Society Part II, ed. John M. Robson, Introduction by Alexander Brady (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1977). 8/14/2014. < /titles/234#lf0223-19_head_008 >. The online edition of the Collected Works is published under licence from the copyright holder, The University of Toronto Press. ©2006 The University of Toronto Press. All rights reserved. No part of this material may be reproduced in any form or medium without the permission of The University of Toronto Press.

- Craft and Criticism

- Fiction and Poetry

- News and Culture

- Lit Hub Radio

- Reading Lists

- Literary Criticism

- Craft and Advice

- In Conversation

- On Translation

- Short Story

- From the Novel

- Bookstores and Libraries

- Film and TV

- Art and Photography

- Freeman’s

- The Virtual Book Channel

- Behind the Mic

- Beyond the Page

- The Cosmic Library

- The Critic and Her Publics

- Emergence Magazine

- Fiction/Non/Fiction

- First Draft: A Dialogue on Writing

- The History of Literature

- I’m a Writer But

- Lit Century

- Tor Presents: Voyage Into Genre

- Windham-Campbell Prizes Podcast

- Write-minded

- The Best of the Decade

- Best Reviewed Books

- BookMarks Daily Giveaway

- The Daily Thrill

- CrimeReads Daily Giveaway

The 10 Best Essay Collections of the Decade

Ever tried. ever failed. no matter..

Friends, it’s true: the end of the decade approaches. It’s been a difficult, anxiety-provoking, morally compromised decade, but at least it’s been populated by some damn fine literature. We’ll take our silver linings where we can.

So, as is our hallowed duty as a literary and culture website—though with full awareness of the potentially fruitless and endlessly contestable nature of the task—in the coming weeks, we’ll be taking a look at the best and most important (these being not always the same) books of the decade that was. We will do this, of course, by means of a variety of lists. We began with the best debut novels , the best short story collections , the best poetry collections , and the best memoirs of the decade , and we have now reached the fifth list in our series: the best essay collections published in English between 2010 and 2019.

The following books were chosen after much debate (and several rounds of voting) by the Literary Hub staff. Tears were spilled, feelings were hurt, books were re-read. And as you’ll shortly see, we had a hard time choosing just ten—so we’ve also included a list of dissenting opinions, and an even longer list of also-rans. As ever, free to add any of your own favorites that we’ve missed in the comments below.

The Top Ten

Oliver sacks, the mind’s eye (2010).

Toward the end of his life, maybe suspecting or sensing that it was coming to a close, Dr. Oliver Sacks tended to focus his efforts on sweeping intellectual projects like On the Move (a memoir), The River of Consciousness (a hybrid intellectual history), and Hallucinations (a book-length meditation on, what else, hallucinations). But in 2010, he gave us one more classic in the style that first made him famous, a form he revolutionized and brought into the contemporary literary canon: the medical case study as essay. In The Mind’s Eye , Sacks focuses on vision, expanding the notion to embrace not only how we see the world, but also how we map that world onto our brains when our eyes are closed and we’re communing with the deeper recesses of consciousness. Relaying histories of patients and public figures, as well as his own history of ocular cancer (the condition that would eventually spread and contribute to his death), Sacks uses vision as a lens through which to see all of what makes us human, what binds us together, and what keeps us painfully apart. The essays that make up this collection are quintessential Sacks: sensitive, searching, with an expertise that conveys scientific information and experimentation in terms we can not only comprehend, but which also expand how we see life carrying on around us. The case studies of “Stereo Sue,” of the concert pianist Lillian Kalir, and of Howard, the mystery novelist who can no longer read, are highlights of the collection, but each essay is a kind of gem, mined and polished by one of the great storytellers of our era. –Dwyer Murphy, CrimeReads Managing Editor

John Jeremiah Sullivan, Pulphead (2011)

The American essay was having a moment at the beginning of the decade, and Pulphead was smack in the middle. Without any hard data, I can tell you that this collection of John Jeremiah Sullivan’s magazine features—published primarily in GQ , but also in The Paris Review , and Harper’s —was the only full book of essays most of my literary friends had read since Slouching Towards Bethlehem , and probably one of the only full books of essays they had even heard of.

Well, we all picked a good one. Every essay in Pulphead is brilliant and entertaining, and illuminates some small corner of the American experience—even if it’s just one house, with Sullivan and an aging writer inside (“Mr. Lytle” is in fact a standout in a collection with no filler; fittingly, it won a National Magazine Award and a Pushcart Prize). But what are they about? Oh, Axl Rose, Christian Rock festivals, living around the filming of One Tree Hill , the Tea Party movement, Michael Jackson, Bunny Wailer, the influence of animals, and by god, the Miz (of Real World/Road Rules Challenge fame).

But as Dan Kois has pointed out , what connects these essays, apart from their general tone and excellence, is “their author’s essential curiosity about the world, his eye for the perfect detail, and his great good humor in revealing both his subjects’ and his own foibles.” They are also extremely well written, drawing much from fictional techniques and sentence craft, their literary pleasures so acute and remarkable that James Wood began his review of the collection in The New Yorker with a quiz: “Are the following sentences the beginnings of essays or of short stories?” (It was not a hard quiz, considering the context.)

It’s hard not to feel, reading this collection, like someone reached into your brain, took out the half-baked stuff you talk about with your friends, researched it, lived it, and represented it to you smarter and better and more thoroughly than you ever could. So read it in awe if you must, but read it. –Emily Temple, Senior Editor

Aleksandar Hemon, The Book of My Lives (2013)

Such is the sentence-level virtuosity of Aleksandar Hemon—the Bosnian-American writer, essayist, and critic—that throughout his career he has frequently been compared to the granddaddy of borrowed language prose stylists: Vladimir Nabokov. While it is, of course, objectively remarkable that anyone could write so beautifully in a language they learned in their twenties, what I admire most about Hemon’s work is the way in which he infuses every essay and story and novel with both a deep humanity and a controlled (but never subdued) fury. He can also be damn funny. Hemon grew up in Sarajevo and left in 1992 to study in Chicago, where he almost immediately found himself stranded, forced to watch from afar as his beloved home city was subjected to a relentless four-year bombardment, the longest siege of a capital in the history of modern warfare. This extraordinary memoir-in-essays is many things: it’s a love letter to both the family that raised him and the family he built in exile; it’s a rich, joyous, and complex portrait of a place the 90s made synonymous with war and devastation; and it’s an elegy for the wrenching loss of precious things. There’s an essay about coming of age in Sarajevo and another about why he can’t bring himself to leave Chicago. There are stories about relationships forged and maintained on the soccer pitch or over the chessboard, and stories about neighbors and mentors turned monstrous by ethnic prejudice. As a chorus they sing with insight, wry humor, and unimaginable sorrow. I am not exaggerating when I say that the collection’s devastating final piece, “The Aquarium”—which details his infant daughter’s brain tumor and the agonizing months which led up to her death—remains the most painful essay I have ever read. –Dan Sheehan, Book Marks Editor

Robin Wall Kimmerer, Braiding Sweetgrass (2013)

Of every essay in my relentlessly earmarked copy of Braiding Sweetgrass , Dr. Robin Wall Kimmerer’s gorgeously rendered argument for why and how we should keep going, there’s one that especially hits home: her account of professor-turned-forester Franz Dolp. When Dolp, several decades ago, revisited the farm that he had once shared with his ex-wife, he found a scene of destruction: The farm’s new owners had razed the land where he had tried to build a life. “I sat among the stumps and the swirling red dust and I cried,” he wrote in his journal.

So many in my generation (and younger) feel this kind of helplessness–and considerable rage–at finding ourselves newly adult in a world where those in power seem determined to abandon or destroy everything that human bodies have always needed to survive: air, water, land. Asking any single book to speak to this helplessness feels unfair, somehow; yet, Braiding Sweetgrass does, by weaving descriptions of indigenous tradition with the environmental sciences in order to show what survival has looked like over the course of many millennia. Kimmerer’s essays describe her personal experience as a Potawotami woman, plant ecologist, and teacher alongside stories of the many ways that humans have lived in relationship to other species. Whether describing Dolp’s work–he left the stumps for a life of forest restoration on the Oregon coast–or the work of others in maple sugar harvesting, creating black ash baskets, or planting a Three Sisters garden of corn, beans, and squash, she brings hope. “In ripe ears and swelling fruit, they counsel us that all gifts are multiplied in relationship,” she writes of the Three Sisters, which all sustain one another as they grow. “This is how the world keeps going.” –Corinne Segal, Senior Editor

Hilton Als, White Girls (2013)

In a world where we are so often reduced to one essential self, Hilton Als’ breathtaking book of critical essays, White Girls , which meditates on the ways he and other subjects read, project and absorb parts of white femininity, is a radically liberating book. It’s one of the only works of critical thinking that doesn’t ask the reader, its author or anyone he writes about to stoop before the doorframe of complete legibility before entering. Something he also permitted the subjects and readers of his first book, the glorious book-length essay, The Women , a series of riffs and psychological portraits of Dorothy Dean, Owen Dodson, and the author’s own mother, among others. One of the shifts of that book, uncommon at the time, was how it acknowledges the way we inhabit bodies made up of variously gendered influences. To read White Girls now is to experience the utter freedom of this gift and to marvel at Als’ tremendous versatility and intelligence.

He is easily the most diversely talented American critic alive. He can write into genres like pop music and film where being part of an audience is a fantasy happening in the dark. He’s also wired enough to know how the art world builds reputations on the nod of rich white patrons, a significant collision in a time when Jean-Michel Basquiat is America’s most expensive modern artist. Als’ swerving and always moving grip on performance means he’s especially good on describing the effect of art which is volatile and unstable and built on the mingling of made-up concepts and the hard fact of their effect on behavior, such as race. Writing on Flannery O’Connor for instance he alone puts a finger on her “uneasy and unavoidable union between black and white, the sacred and the profane, the shit and the stars.” From Eminem to Richard Pryor, André Leon Talley to Michael Jackson, Als enters the life and work of numerous artists here who turn the fascinations of race and with whiteness into fury and song and describes the complexity of their beauty like his life depended upon it. There are also brief memoirs here that will stop your heart. This is an essential work to understanding American culture. –John Freeman, Executive Editor

Eula Biss, On Immunity (2014)

We move through the world as if we can protect ourselves from its myriad dangers, exercising what little agency we have in an effort to keep at bay those fears that gather at the edges of any given life: of loss, illness, disaster, death. It is these fears—amplified by the birth of her first child—that Eula Biss confronts in her essential 2014 essay collection, On Immunity . As any great essayist does, Biss moves outward in concentric circles from her own very private view of the world to reveal wider truths, discovering as she does a culture consumed by anxiety at the pervasive toxicity of contemporary life. As Biss interrogates this culture—of privilege, of whiteness—she interrogates herself, questioning the flimsy ways in which we arm ourselves with science or superstition against the impurities of daily existence.

Five years on from its publication, it is dismaying that On Immunity feels as urgent (and necessary) a defense of basic science as ever. Vaccination, we learn, is derived from vacca —for cow—after the 17th-century discovery that a small application of cowpox was often enough to inoculate against the scourge of smallpox, an etymological digression that belies modern conspiratorial fears of Big Pharma and its vaccination agenda. But Biss never scolds or belittles the fears of others, and in her generosity and openness pulls off a neat (and important) trick: insofar as we are of the very world we fear, she seems to be suggesting, we ourselves are impure, have always been so, permeable, vulnerable, yet so much stronger than we think. –Jonny Diamond, Editor-in-Chief

Rebecca Solnit, The Mother of All Questions (2016)

When Rebecca Solnit’s essay, “Men Explain Things to Me,” was published in 2008, it quickly became a cultural phenomenon unlike almost any other in recent memory, assigning language to a behavior that almost every woman has witnessed—mansplaining—and, in the course of identifying that behavior, spurring a movement, online and offline, to share the ways in which patriarchal arrogance has intersected all our lives. (It would also come to be the titular essay in her collection published in 2014.) The Mother of All Questions follows up on that work and takes it further in order to examine the nature of self-expression—who is afforded it and denied it, what institutions have been put in place to limit it, and what happens when it is employed by women. Solnit has a singular gift for describing and decoding the misogynistic dynamics that govern the world so universally that they can seem invisible and the gendered violence that is so common as to seem unremarkable; this naming is powerful, and it opens space for sharing the stories that shape our lives.

The Mother of All Questions, comprised of essays written between 2014 and 2016, in many ways armed us with some of the tools necessary to survive the gaslighting of the Trump years, in which many of us—and especially women—have continued to hear from those in power that the things we see and hear do not exist and never existed. Solnit also acknowledges that labels like “woman,” and other gendered labels, are identities that are fluid in reality; in reviewing the book for The New Yorker , Moira Donegan suggested that, “One useful working definition of a woman might be ‘someone who experiences misogyny.'” Whichever words we use, Solnit writes in the introduction to the book that “when words break through unspeakability, what was tolerated by a society sometimes becomes intolerable.” This storytelling work has always been vital; it continues to be vital, and in this book, it is brilliantly done. –Corinne Segal, Senior Editor

Valeria Luiselli, Tell Me How It Ends (2017)

The newly minted MacArthur fellow Valeria Luiselli’s four-part (but really six-part) essay Tell Me How It Ends: An Essay in Forty Questions was inspired by her time spent volunteering at the federal immigration court in New York City, working as an interpreter for undocumented, unaccompanied migrant children who crossed the U.S.-Mexico border. Written concurrently with her novel Lost Children Archive (a fictional exploration of the same topic), Luiselli’s essay offers a fascinating conceit, the fashioning of an argument from the questions on the government intake form given to these children to process their arrivals. (Aside from the fact that this essay is a heartbreaking masterpiece, this is such a good conceit—transforming a cold, reproducible administrative document into highly personal literature.) Luiselli interweaves a grounded discussion of the questionnaire with a narrative of the road trip Luiselli takes with her husband and family, across America, while they (both Mexican citizens) wait for their own Green Card applications to be processed. It is on this trip when Luiselli reflects on the thousands of migrant children mysteriously traveling across the border by themselves. But the real point of the essay is to actually delve into the real stories of some of these children, which are agonizing, as well as to gravely, clearly expose what literally happens, procedural, when they do arrive—from forms to courts, as they’re swallowed by a bureaucratic vortex. Amid all of this, Luiselli also takes on more, exploring the larger contextual relationship between the United States of America and Mexico (as well as other countries in Central America, more broadly) as it has evolved to our current, adverse moment. Tell Me How It Ends is so small, but it is so passionate and vigorous: it desperately accomplishes in its less-than-100-pages-of-prose what centuries and miles and endless records of federal bureaucracy have never been able, and have never cared, to do: reverse the dehumanization of Latin American immigrants that occurs once they set foot in this country. –Olivia Rutigliano, CrimeReads Editorial Fellow

Zadie Smith, Feel Free (2018)

In the essay “Meet Justin Bieber!” in Feel Free , Zadie Smith writes that her interest in Justin Bieber is not an interest in the interiority of the singer himself, but in “the idea of the love object”. This essay—in which Smith imagines a meeting between Bieber and the late philosopher Martin Buber (“Bieber and Buber are alternative spellings of the same German surname,” she explains in one of many winning footnotes. “Who am I to ignore these hints from the universe?”). Smith allows that this premise is a bit premise -y: “I know, I know.” Still, the resulting essay is a very funny, very smart, and un-tricky exploration of individuality and true “meeting,” with a dash of late capitalism thrown in for good measure. The melding of high and low culture is the bread and butter of pretty much every prestige publication on the internet these days (and certainly of the Twitter feeds of all “public intellectuals”), but the essays in Smith’s collection don’t feel familiar—perhaps because hers is, as we’ve long known, an uncommon skill. Though I believe Smith could probably write compellingly about anything, she chooses her subjects wisely. She writes with as much electricity about Brexit as the aforementioned Beliebers—and each essay is utterly engrossing. “She contains multitudes, but her point is we all do,” writes Hermione Hoby in her review of the collection in The New Republic . “At the same time, we are, in our endless difference, nobody but ourselves.” –Jessie Gaynor, Social Media Editor

Tressie McMillan Cottom, Thick: And Other Essays (2019)

Tressie McMillan Cottom is an academic who has transcended the ivory tower to become the sort of public intellectual who can easily appear on radio or television talk shows to discuss race, gender, and capitalism. Her collection of essays reflects this duality, blending scholarly work with memoir to create a collection on the black female experience in postmodern America that’s “intersectional analysis with a side of pop culture.” The essays range from an analysis of sexual violence, to populist politics, to social media, but in centering her own experiences throughout, the collection becomes something unlike other pieces of criticism of contemporary culture. In explaining the title, she reflects on what an editor had said about her work: “I was too readable to be academic, too deep to be popular, too country black to be literary, and too naïve to show the rigor of my thinking in the complexity of my prose. I had wanted to create something meaningful that sounded not only like me, but like all of me. It was too thick.” One of the most powerful essays in the book is “Dying to be Competent” which begins with her unpacking the idiocy of LinkedIn (and the myth of meritocracy) and ends with a description of her miscarriage, the mishandling of black woman’s pain, and a condemnation of healthcare bureaucracy. A finalist for the 2019 National Book Award for Nonfiction, Thick confirms McMillan Cottom as one of our most fearless public intellectuals and one of the most vital. –Emily Firetog, Deputy Editor

Dissenting Opinions

The following books were just barely nudged out of the top ten, but we (or at least one of us) couldn’t let them pass without comment.

Elif Batuman, The Possessed (2010)

In The Possessed Elif Batuman indulges her love of Russian literature and the result is hilarious and remarkable. Each essay of the collection chronicles some adventure or other that she had while in graduate school for Comparative Literature and each is more unpredictable than the next. There’s the time a “well-known 20th-centuryist” gave a graduate student the finger; and the time when Batuman ended up living in Samarkand, Uzbekistan, for a summer; and the time that she convinced herself Tolstoy was murdered and spent the length of the Tolstoy Conference in Yasnaya Polyana considering clues and motives. Rich in historic detail about Russian authors and literature and thoughtfully constructed, each essay is an amalgam of critical analysis, cultural criticism, and serious contemplation of big ideas like that of identity, intellectual legacy, and authorship. With wit and a serpentine-like shape to her narratives, Batuman adopts a form reminiscent of a Socratic discourse, setting up questions at the beginning of her essays and then following digressions that more or less entreat the reader to synthesize the answer for herself. The digressions are always amusing and arguably the backbone of the collection, relaying absurd anecdotes with foreign scholars or awkward, surreal encounters with Eastern European strangers. Central also to the collection are Batuman’s intellectual asides where she entertains a theory—like the “problem of the person”: the inability to ever wholly capture one’s character—that ultimately layer the book’s themes. “You are certainly my most entertaining student,” a professor said to Batuman. But she is also curious and enthusiastic and reflective and so knowledgeable that she might even convince you (she has me!) that you too love Russian literature as much as she does. –Eleni Theodoropoulos, Editorial Fellow

Roxane Gay, Bad Feminist (2014)

Roxane Gay’s now-classic essay collection is a book that will make you laugh, think, cry, and then wonder, how can cultural criticism be this fun? My favorite essays in the book include Gay’s musings on competitive Scrabble, her stranded-in-academia dispatches, and her joyous film and television criticism, but given the breadth of topics Roxane Gay can discuss in an entertaining manner, there’s something for everyone in this one. This book is accessible because feminism itself should be accessible – Roxane Gay is as likely to draw inspiration from YA novels, or middle-brow shows about friendship, as she is to introduce concepts from the academic world, and if there’s anyone I trust to bridge the gap between high culture, low culture, and pop culture, it’s the Goddess of Twitter. I used to host a book club dedicated to radical reads, and this was one of the first picks for the club; a week after the book club met, I spied a few of the attendees meeting in the café of the bookstore, and found out that they had bonded so much over discussing Bad Feminist that they couldn’t wait for the next meeting of the book club to keep discussing politics and intersectionality, and that, in a nutshell, is the power of Roxane. –Molly Odintz, CrimeReads Associate Editor

Rivka Galchen, Little Labors (2016)

Generally, I find stories about the trials and tribulations of child-having to be of limited appeal—useful, maybe, insofar as they offer validation that other people have also endured the bizarre realities of living with a tiny human, but otherwise liable to drift into the musings of parents thrilled at the simple fact of their own fecundity, as if they were the first ones to figure the process out (or not). But Little Labors is not simply an essay collection about motherhood, perhaps because Galchen initially “didn’t want to write about” her new baby—mostly, she writes, “because I had never been interested in babies, or mothers; in fact, those subjects had seemed perfectly not interesting to me.” Like many new mothers, though, Galchen soon discovered her baby—which she refers to sometimes as “the puma”—to be a preoccupying thought, demanding to be written about. Galchen’s interest isn’t just in her own progeny, but in babies in literature (“Literature has more dogs than babies, and also more abortions”), The Pillow Book , the eleventh-century collection of musings by Sei Shōnagon, and writers who are mothers. There are sections that made me laugh out loud, like when Galchen continually finds herself in an elevator with a neighbor who never fails to remark on the puma’s size. There are also deeper, darker musings, like the realization that the baby means “that it’s not permissible to die. There are days when this does not feel good.” It is a slim collection that I happened to read at the perfect time, and it remains one of my favorites of the decade. –Emily Firetog, Deputy Editor

Charlie Fox, This Young Monster (2017)