What are Financial Statements?

- #1 Financial Statements Example – Cash Flow Statement

- #2 Financial Statements Example – Income Statement

- #3 Financial Statements Example – Balance Sheet

Additional Resources

Financial statements examples – amazon case study.

Over 1.8 million professionals use CFI to learn accounting, financial analysis, modeling and more. Start with a free account to explore 20+ always-free courses and hundreds of finance templates and cheat sheets. Start Free

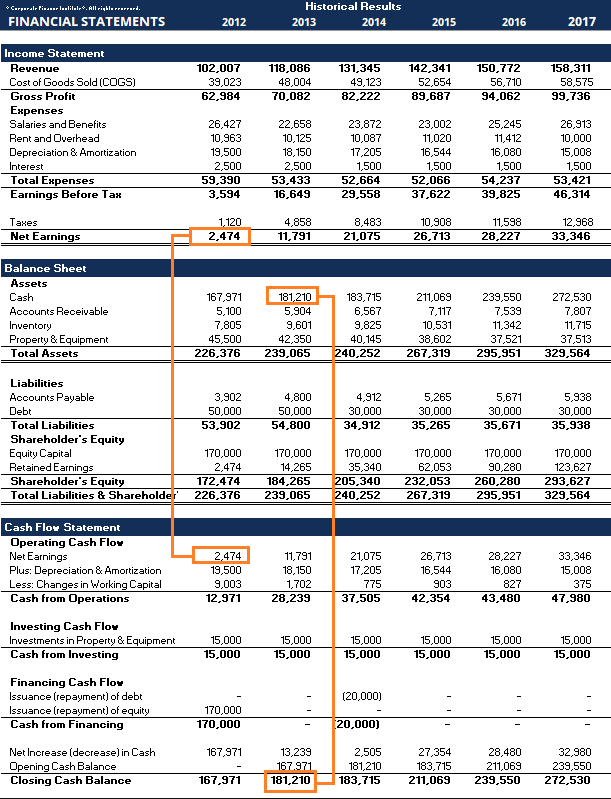

Financial statements are the records of a company’s financial condition and activities during a period of time. Financial statements show the financial performance and strength of a company . The three core financial statements are the income statement , balance sheet , and cash flow statement . These three statements are linked together to create the three statement financial model . Analyzing financial statements can help an analyst assess the profitability and liquidity of a company. Financial statements are complex. It is best to become familiar with them by looking at financial statements examples.

In this article, we will take a look at some financial statement examples from Amazon.com, Inc. for a more in-depth look at the accounts and line items presented on financial statements.

Learn to analyze financial statements with Corporate Finance Institute’s Reading Financial Statements course!

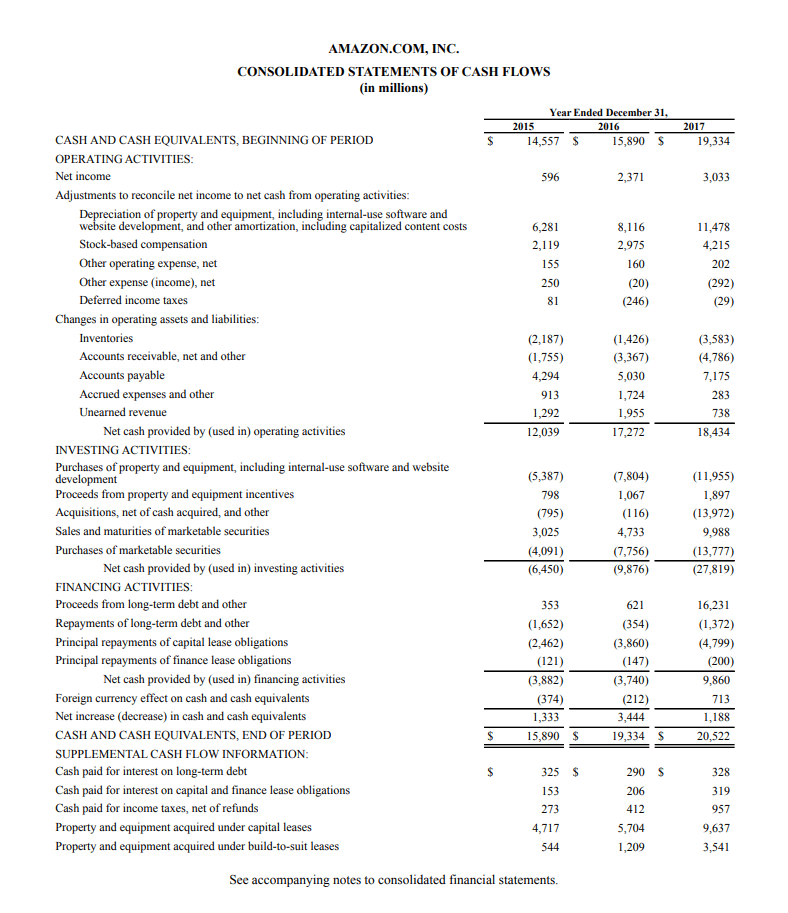

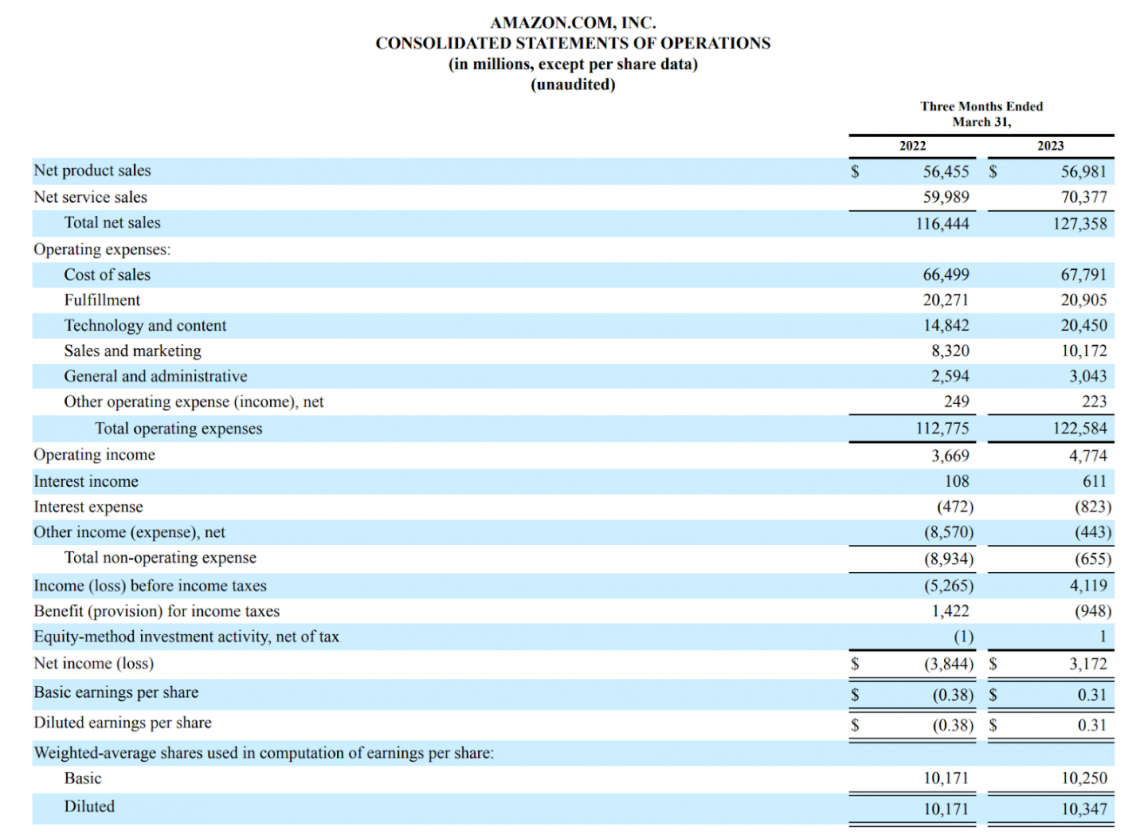

#1 Financial Statements Example – Cash Flow Statement

The first of our financial statements examples is the cash flow statement. The cash flow statement shows the changes in a company’s cash position during a fiscal period. The cash flow statement uses the net income figure from the income statement and adjusts it for non-cash expenses. This is done to find the change in cash from the beginning of the period to the end of the period.

Most companies begin their financial statements with the income statement. However, Amazon (NASDAQ: AMZN) begins its financial statements section in its annual 10-K report with its cash flow statement.

The cash flow statement begins with the net income and adjusts it for non-cash expenses, changes to balance sheet accounts, and other usages and receipts of cash. The adjustments are grouped under operating activities , investing activities , and financing activities .

The following are explanations for the line items listed in Amazon’s cash flow statement. Please note that certain items such as “Other operating expenses, net” are often defined differently by different companies:

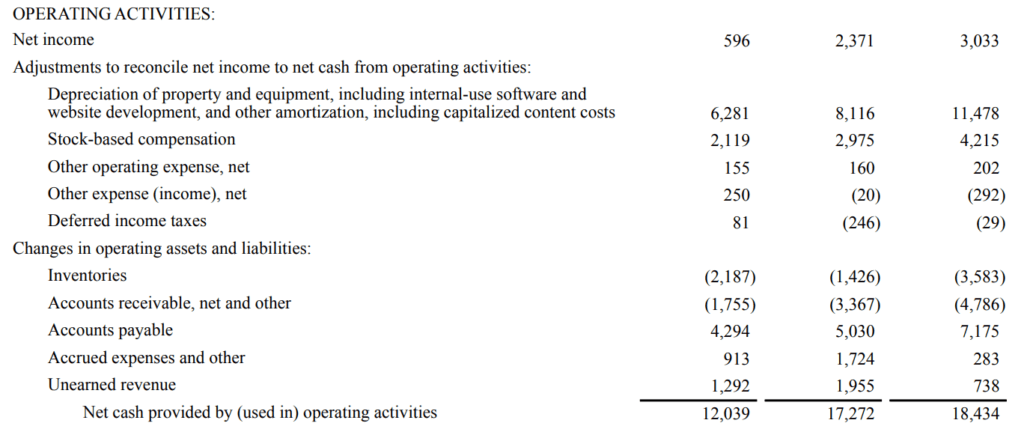

Operating Activities:

Depreciation of property and equipment (…) : a non-cash expense representing the deterioration of an asset (e.g. factory equipment).

Stock-based compensation : a non-cash expense as a company awards stock options or other stock-based forms of compensation to employees as part of their compensation and wage agreements.

Other operating expense, net: a non-cash expense primarily relating to the amortization of Amazon’s intangible assets .

Other expense (income), net: a non-cash expense relating to foreign currency and equity warrant valuations.

Deferred income taxes : temporary differences between book tax and actual income tax. The amount of tax the company pays may be different from what it shows on its financial statements.

Changes in operating assets and liabilities : non-cash changes in operating assets or liabilities. For example, an increase in accounts receivable is a sale or a source of income where no actual cash was received, thus resulting in a deduction. Conversely, an increase in accounts payable is a purchase or expense where no actual cash was used, resulting in an addition to net cash.

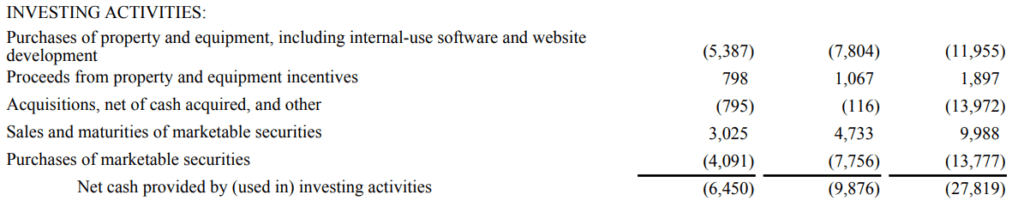

Investing Activities:

Purchases of property and equipment (…): purchases of plants, property, and equipment are usages of cash. A deduction from net cash.

Proceeds from property and equipment incentives: this line is added for additional detail on Amazon’s property and equipment purchases. Incentives received from property and equipment vendors are recorded as a reduction in Amazon’s costs and thus a reduction in cash usage.

Acquisitions , net of cash acquired, and other: cash used towards acquisitions of other companies, net of cash acquired as a result of the acquisition. A deduction from net cash.

Sales and maturities of marketable securities : the sale or proceeds obtained from holding marketable securities (short-term financial instruments that mature within a year) to maturity. An addition to net cash.

Purchases of marketable securities: the purchase of marketable securities. A deduction from net cash.

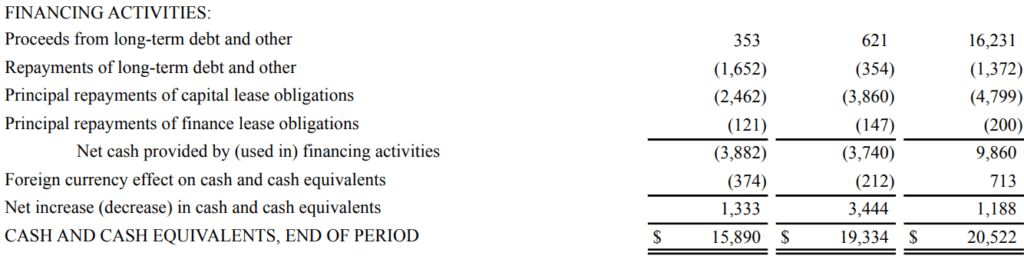

Financing Activities:

Proceeds from long-term debt and other: cash obtained from raising capital by issuing long-term debt. An addition to net cash.

Repayments of long-term debt and other: cash used to repay long-term debt obligations. A deduction from net cash.

Principal repayments of capital lease obligations: cash used to repay the principal amount of capital lease obligations. A deduction from net cash.

Principal repayments of finance lease obligations: cash used to repay the principal amount of finance lease obligations. A deduction from net cash.

Foreign currency effect on cash and cash equivalents : the effect of foreign exchange rates on cash held in foreign currencies.

Supplemental Cash Flow Information:

Cash paid for interest on long-term debt: cash usages to pay accumulated interest from long-term debt.

Cash paid for interest on capital and finance lease obligations: cash usages to pay accumulated interest from capital and finance lease obligations.

Cash paid for income taxes , net of refunds: cash usages to pay income taxes.

Property and equipment acquired under capital leases: the value of property and equipment acquired under new capital leases in the fiscal period.

Property and equipment acquired under build-to-suit leases: the value of property and equipment acquired under new build-to-suit leases in the fiscal period.

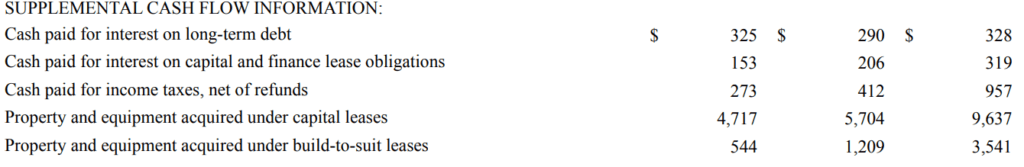

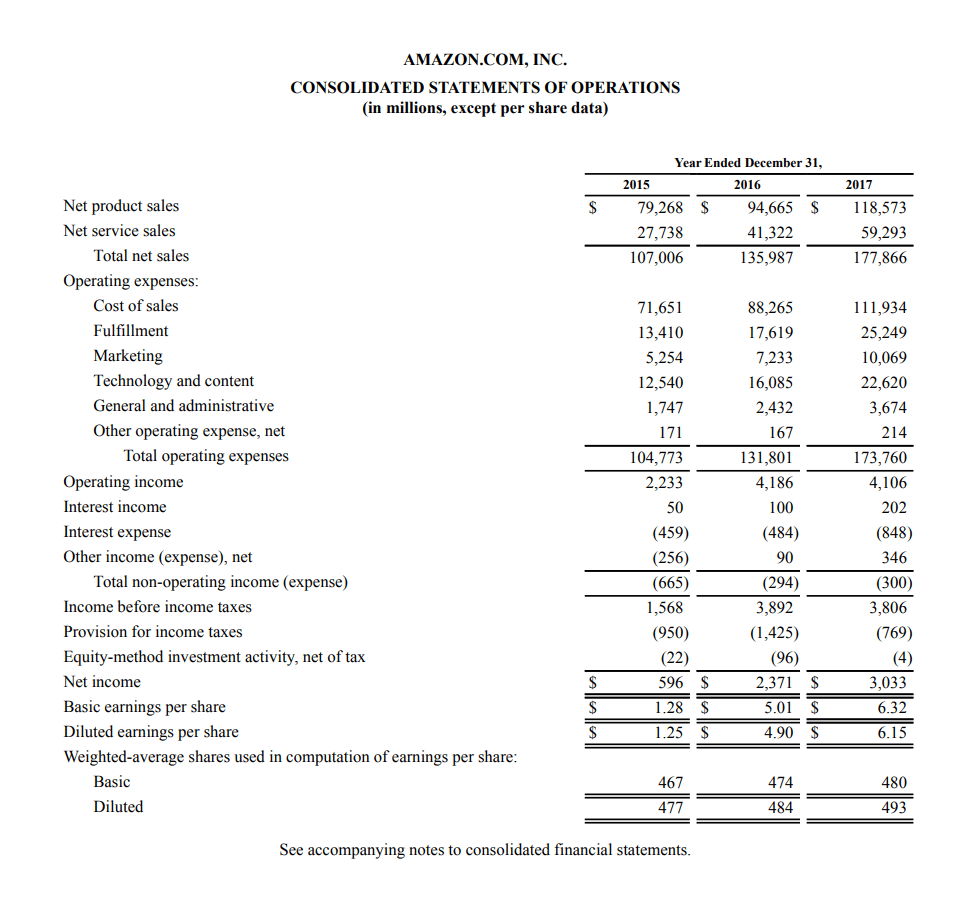

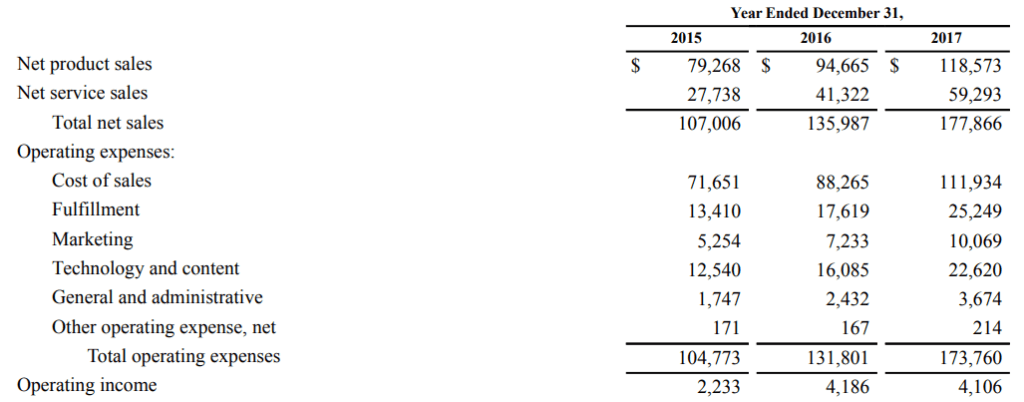

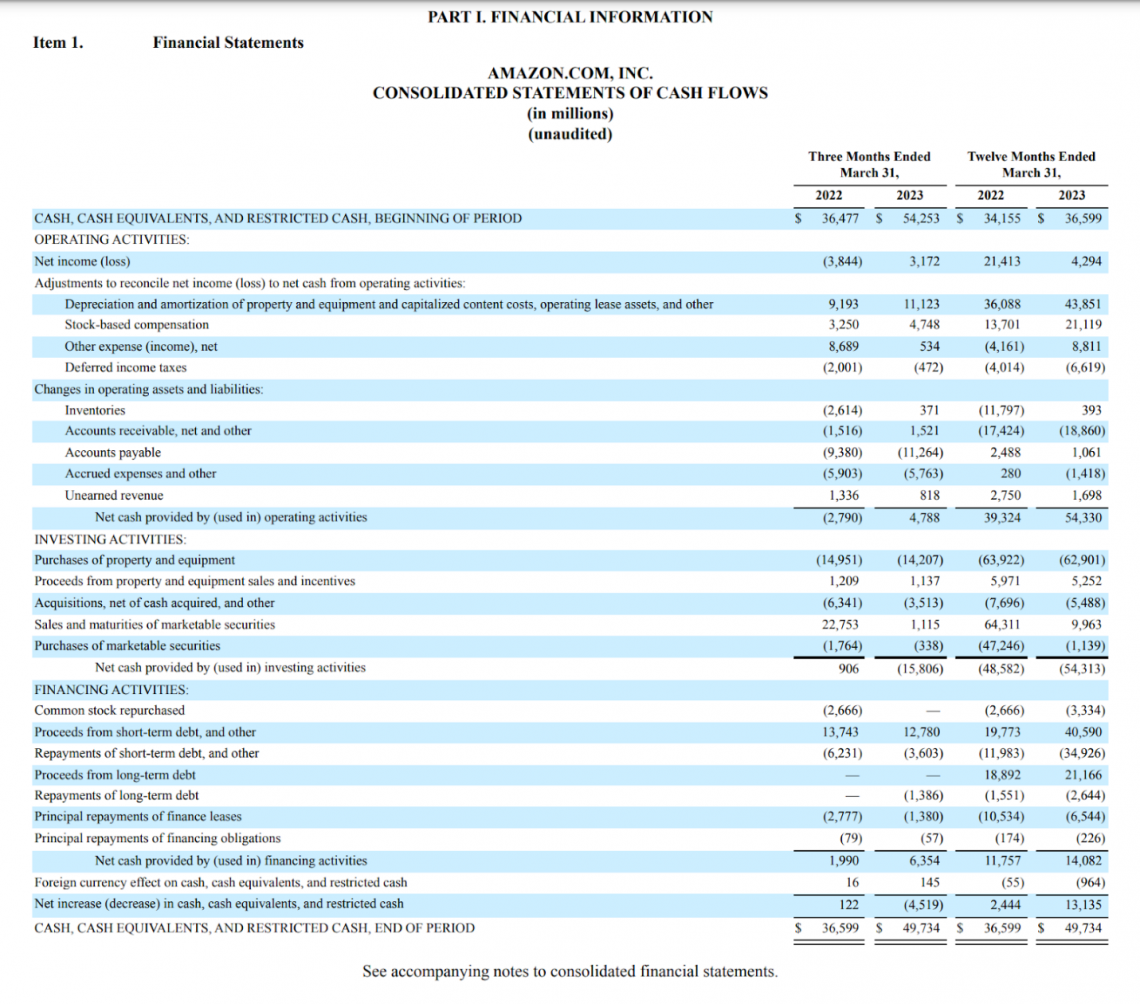

#2 Financial Statements Example – Income Statement

The next statement in our financial statements examples is the income statement. The income statement is the first place for an analyst to look at if they want to assess a company’s profitability .

Want to learn more about financial analysis and assessing a company’s profitability? Financial Modeling & Valuation Analyst (FMVA)® Certification Program will teach you everything you need to know to become a world-class financial analyst!

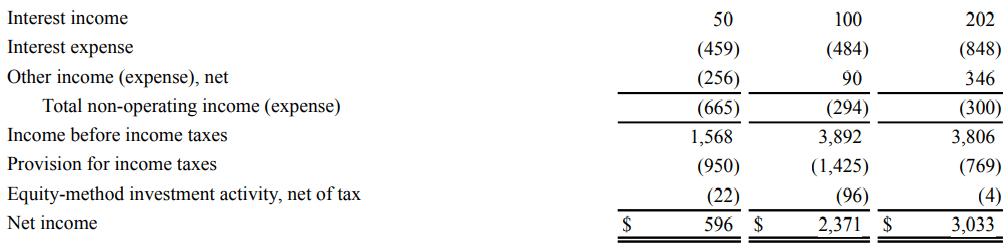

The income statement provides a look at a company’s financial performance throughout a certain period, usually a fiscal quarter or year. This period is usually denoted at the top of the statement, as can be seen above. The income statement contains information regarding sales , costs of sales , operating expenses, and other expenses.

The following are explanations for the line items listed in Amazon’s income statement:

Operating Income (EBIT):

Net product sales: revenue derived from Amazon’s product sales such as Amazon’s first-party retail sales and proprietary products (e.g., Amazon Echo)

Net services sales: revenue generated from the sale of Amazon’s services. This includes proceeds from Amazon Web Services (AWS) , subscription services, etc.

Cost of sales: costs directly associated with the sale of Amazon products and services. For example, the cost of raw materials used to manufacture Amazon products is a cost of sales.

Fulfillment: expenses relating to Amazon’s fulfillment process. Amazon’s fulfillment process includes storing, picking, packing, shipping, and handling customer service for products.

Marketing : expenses pertaining to advertising and marketing for Amazon and its products and services. Marketing expense is often grouped with selling, general, and administrative expenses (SG&A) but Amazon has chosen to break it out as its own line item.

Technology and content: costs relating to operating Amazon’s AWS segment.

General and administrative : operating expenses that are not directly related to producing Amazon’s products or services. These expenses are sometimes referred to as non-manufacturing costs or overhead costs. These include rent, insurance, managerial salaries, utilities, and other similar expenses.

Other operating expenses, net: expenses primarily relating to the amortization of Amazon’s intangible assets.

Operating income : the income left over after all operating expenses (expenses directly related to the operation of the business) are deducted. Also known as EBIT .

Net Income:

Interest income: income generated by Amazon from investing excess cash. Amazon typically invests excess cash in investment-grade , short to intermediate-term fixed income securities , and AAA-rated money market funds.

Interest expense : expenses relating to accumulated interest from capital and finance lease obligations and long-term debt.

Other income (expense), net: income or expenses relating to foreign currency and equity warrant valuations.

Income before income taxes : Amazon’s income after operating and non-operating expenses have been deducted.

Provision for income taxes: the expense relating to the amount of income tax Amazon must pay within the fiscal year .

Equity-method investment activity, net of tax: proportionate losses or earnings from companies where Amazon owns a minority stake .

Net income: the amount of income left over after Amazon has paid off all its expenses.

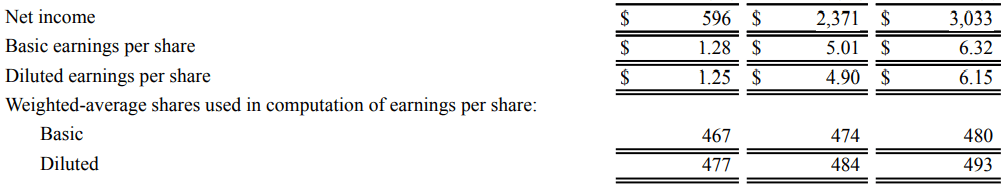

Earnings per Share (EPS):

Basic earnings per share : earnings per share calculated using the basic number of shares outstanding.

Diluted earnings per share: earnings per share calculated using the diluted number of shares outstanding.

Weighted-average shares used in the computation of earnings per share: a weighted average number of shares to account for new stock issuances throughout the year. The way the calculation works is by taking the weighted average number of shares outstanding during the fiscal period covered.

For example, a company has 100 shares outstanding at the beginning of the year. At the end of the first quarter, the company issues another 50 shares, bringing the total number of shares outstanding to 150. The calculation for the weighted average number of shares would look like below:

100*0.25 + 150*0.75 = 131.25

Basic: the number of shares outstanding in the market at the date of the financial statement.

Diluted : the number of shares outstanding if all convertible securities (e.g. convertible preferred stock, convertible bonds ) are exercised.

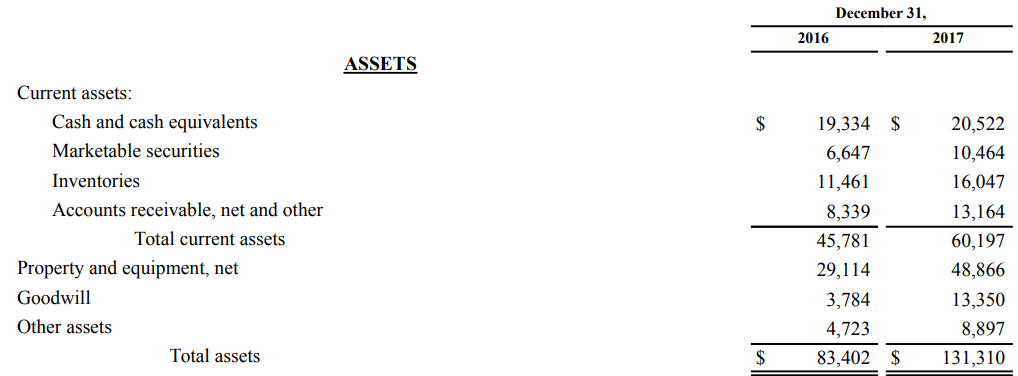

#3 Financial Statements Example – Balance Sheet

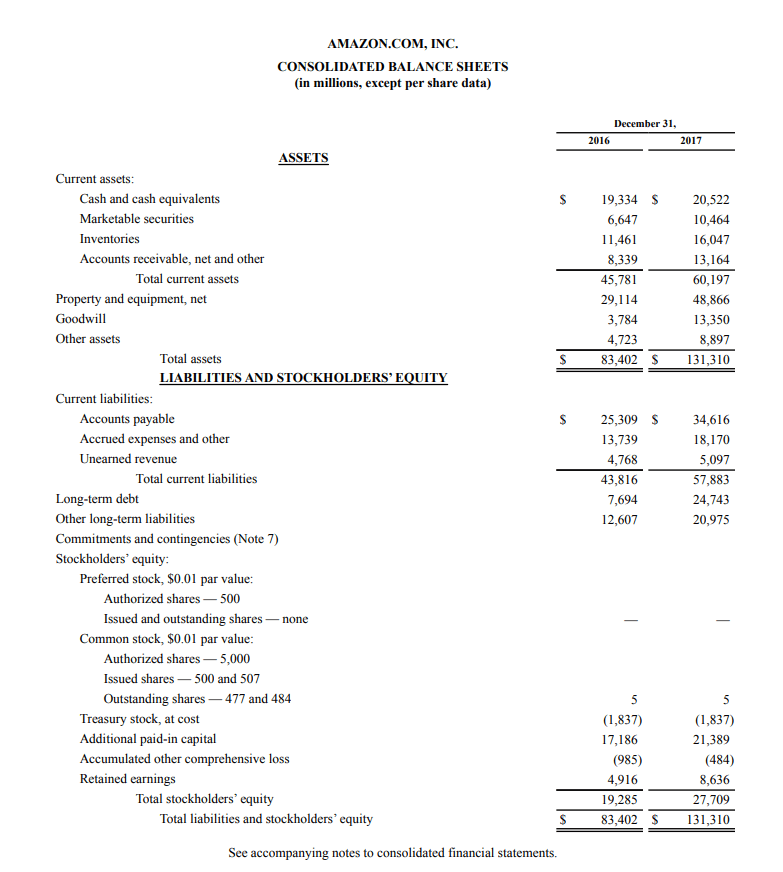

The last statement we will look at with our financial statements examples is the balance sheet. The balance sheet shows the company’s assets , liabilities , and stockholders’ equity at a specific point in time.

Learn how a world-class financial analyst uses these three financial statements with CFI’s Financial Modeling & Valuation Analyst (FMVA)® Certification Program !

Unlike the income statement and the cash flow statement, which display financial information for the company during a fiscal period, the balance sheet is a snapshot of the company’s finances at a specific point in time. It can be seen above in the line regarding the date.

Compared to the Cash Flow Statement and Statement of Income, it states ‘December 31, 2017’ as opposed to ‘Year Ended December 31, 2017’. By displaying snapshots from different periods, the balance sheet shows changes in the accounts of a company.

The following are explanations for the line items listed in Amazon’s balance sheet:

Cash and cash equivalents : cash or highly liquid assets and short-term commitments that can be quickly converted into cash.

Marketable securities: short-term financial instruments that mature within a year.

Inventories : goods currently held in stock for sale, in-process goods, and materials to be used in the production of goods or services.

Accounts receivable , net and other: credit sales of a business that have not yet been fully paid by customers.

Goodwill : the difference between the price paid in an acquisition of a company and the fair market value of the target company’s net assets.

Other assets: Amazon’s acquired intangible assets, net of amortization. This includes items such as video, music content, and long-term deferred tax assets.

Liabilities:

Accounts payable : short-term liabilities incurred when Amazon purchases goods from suppliers on credit.

Accrued expenses and other: liabilities primarily related to Amazon’s unredeemed gift cards, leases and asset retirement obligations, current debt, acquired digital media content, etc.

Unearned revenue : revenue generated when payment is received for goods or services that have not yet been delivered or fulfilled. Unearned revenue is a result of revenue recognition principles outlined by U.S. GAAP and IFRS .

Long-term debt: the amount of outstanding debt a company holds that has a maturity of 12 months or longer.

Other long-term liabilities: Amazon’s other long-term liabilities, which include long-term capital and finance lease obligations, construction liabilities, tax contingencies, long-term deferred tax liabilities, etc. (Note 6 of Amazon’s 2017 annual report).

Stockholders’ Equity:

Preferred stock : stock issued by a corporation that represents ownership in the corporation. Preferred stockholders have a priority claim on the company’s assets and earnings over common stockholders. Preferred stockholders are prioritized with regard to dividends but do not have any voting rights in the corporation.

Common stock : stock issued by a corporation that represents ownership in the corporation. Common stockholders can participate in corporate decisions through voting.

Treasury stock , at cost: also known as reacquired stock, treasury stock represents outstanding shares that have been repurchased from the stockholder by the company.

Additional paid-in capital : the value of share capital above its stated par value in the above line item for common stock ($0.01 in the case of Amazon). In Amazon’s case, the value of its issued share capital is $17,186 million more than the par value of its common stock, which is worth $5 million.

Accumulated other comprehensive loss: accounts for foreign currency translation adjustments and unrealized gains and losses on available-for-sale/marketable securities.

Retained earnings : the portion of a company’s profits that is held for reinvestment back into the business, as opposed to being distributed as dividends to stockholders.

As you can see from the above financial statements examples, financial statements are complex and closely linked. There are many accounts in financial statements that can be used to represent amounts regarding different business activities. Many of these accounts are typically labeled “other” type accounts, such as “Other operating expenses, net”. In our financial statements examples, we examined how these accounts functioned for Amazon.

Now that you have become more proficient in reading the financial statements examples, round out your skills with some of our other resources. Corporate Finance Institute has resources that will help you expand your knowledge and advance your career! Check out the links below:

- Financial Modeling & Valuation Analyst (FMVA)® Certification Program

- Financial Analysis Fundamentals

- Three Financial Statements Summary

- Free CFI Accounting eBook

- See all accounting resources

- Share this article

Create a free account to unlock this Template

Access and download collection of free Templates to help power your productivity and performance.

Already have an account? Log in

Supercharge your skills with Premium Templates

Take your learning and productivity to the next level with our Premium Templates.

Upgrading to a paid membership gives you access to our extensive collection of plug-and-play Templates designed to power your performance—as well as CFI's full course catalog and accredited Certification Programs.

Already have a Self-Study or Full-Immersion membership? Log in

Access Exclusive Templates

Gain unlimited access to more than 250 productivity Templates, CFI's full course catalog and accredited Certification Programs, hundreds of resources, expert reviews and support, the chance to work with real-world finance and research tools, and more.

Already have a Full-Immersion membership? Log in

- Recently Active

- Top Discussions

- Best Content

By Industry

- Investment Banking

- Private Equity

- Hedge Funds

- Real Estate

- Venture Capital

- Asset Management

- Equity Research

- Investing, Markets Forum

- Business School

- Fashion Advice

- Technical Skills

- Accounting Articles

Financial Statements Examples – Amazon Case Study

Financial Statements are informational records detailing a company’s business activities over a period.

Austin has been working with Ernst & Young for over four years, starting as a senior consultant before being promoted to a manager. At EY, he focuses on strategy, process and operations improvement, and business transformation consulting services focused on health provider, payer, and public health organizations. Austin specializes in the health industry but supports clients across multiple industries.

Austin has a Bachelor of Science in Engineering and a Masters of Business Administration in Strategy, Management and Organization, both from the University of Michigan.

- What Are Financial Statements?

Amazon’s Balance Sheet

Amazon’s income statement, amazon’s cash flow statement, usage of financial statements, amazon case study faqs, what are financial statements.

Investors need financial statements to gain a full understanding of how a company operates in relation to competitors. In the case of Amazon , profitability metrics used to analyze most businesses cannot be used to compare the company to businesses in the same sector.

Amazon remains low in profitability continuously to reinvest in growing operations and new business opportunities. Instead, investors can point to the metrics signified in Amazon’s cash flow statement to demonstrate growth in revenue generation over the long term.

There are three main types of financial statements, all of which provide a current or potential investor with a different viewpoint of a company’s financials. These include the following below.

Balance Sheet

The balance sheet represents a company’s total assets, liabilities, and shareholder ’s equity at a certain time.

Assets are all items owned by a company with tangible or intangible value, while liabilities are all debts a company must repay in the future.

Shareholders' equity is simply calculated by subtracting total assets from total liabilities. This represents the book value of a business.

Income Statement

The income statement represents a company’s total generated income minus expenses over a specified range of time. This can be 3 months in a quarterly report or a year in an annual report .

Revenue includes the total money a company makes over a set time.

This includes operating revenue from business activities and non-operating revenue, such as interest from a company bank account.

Expenses include the total amount of money spent by a company over time. These can be grouped into two separate categories, Primary expenses occur from generating revenue, and secondary expenses appear from debt financing and selling off held assets.

Cash Flow Statement

The cash flow statement represents a company’s total cash inflows and outflows over a specified time range, similar to the income statement. Cash in a business can come from operating, investing, or financing activities.

Operating activities are events in which the business produces or spends money to sell its products or services. This would be income from the sales of goods or services or interest payments and expenses such as wages and rent payments for company facilities.

Investing activities include selling or purchasing assets, which can include investing in business equipment or purchasing short-term securities. Financing activities include the payment of loans and the issuance of dividends or stock repurchases.

Key Takeaways

- Financial statements have information relevant for investors to understand the operations and profitability of a business over a specified time.

- Fundamental analysis typically focuses on the main three financial statements: the balance sheet, income statement, and cash flow statement.

- Although analyzing business financials can provide an unaltered outlook into the operations of a business, the numbers don’t always demonstrate the full story, and investors should always conduct thorough due diligence beyond pure statistics.

- Investors must ensure all of a company's financial statements are analyzed before forming a thesis, as inconsistencies in one sheet may be caused by an unusual one-time expense or dictated by a global measure out of the company’s control (ex., COVID-19).

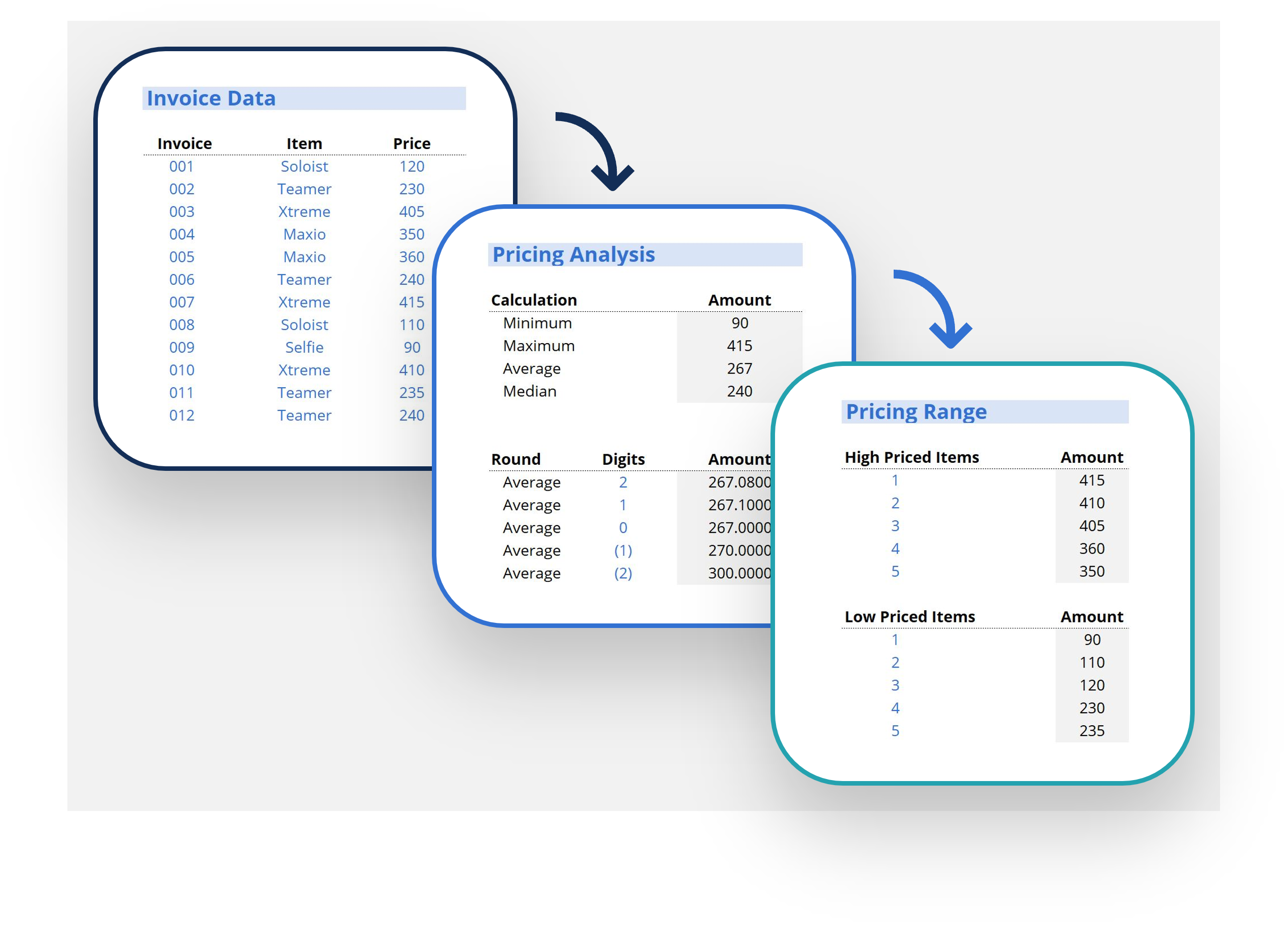

Now that we have a general understanding of the financial statements, we can begin to take a look at Amazon’s most recent quarterly filing.

Company filings can be found by using EDGAR (database of regulatory filings for investors by the SEC) or from Amazon’s investor relations website.

Before we begin analyzing this sheet, it is important to take note of the statement just below the title, indicating that the data is being displayed in millions.

This can throw off newcomers, who may be very confused upon seeing Amazon’s revenue is $53,888. Amazon’s quarterly revenue is indeed $53.8 billion as calculated in millions.

When looking at Amazon’s assets, it is important to note the difference between current and total assets. Current assets are categorized separately due to the expectation that they can be converted to cash within the fiscal year.

Current assets can be used in the current ratio to analyze Amazon’s ability to pay off its short-term obligations. The current ratio formula is:

Current Ratio = Current Assets / Current Liabilities

Amazon’s current ratio sits at 0.92, which is below the e-commerce industry average of 2.09 as of March 2023 (Source: Macrotrends ).

This could mean that Amazon is potentially overvalued compared to competitors, but this is only one metric and should ultimately be all of an investment decision, especially considering the capital-intensive nature of Amazon’s business model.

It is also important to understand all of the vocabulary used to detail items in Amazon’s balance sheet. Some of the major items’ definitions can be found below:

Assets are classified as follows.

- Cash and cash equivalents: Assets of high liquidity, such as certificates of deposit or treasury bonds.

- Marketable securities: Liquid securities can be sold in the public market, such as stock in another company or corporate bonds.

- Accounts receivable (A/R): Money owed to the company that has not been received yet, such as from items previously bought on credit.

- Inventories: Unsold finished or unfinished products from a company that has yet to be sold.

- Property and equipment (PP&E): Assets owned by a company that is used for business activities. It may include factory assets or other types of real estate.

- Operating leases: Assets rented by a business for operational purposes. Calculated as the net present value on the balance sheet.

- Goodwill: Calculates intangible assets that cannot be sold or directly measured, such as customer reputation and loyalty.

Liabilities are of the following types.

- Accounts payable (A/P): Obligations accrued through business activities that must be paid off shortly.

- Accrued expenses: Current liabilities for a business that must be paid in the next 12 months.

- Unearned revenue: This represents revenue earned by a business that has not yet received. Prevents profits from being overstated for a specific period.

- Long-term debt: Debts in which payments are required over 12 months.

- Lease liabilities: Payment obligations of a lease taken out by a company.

- Stockholders’ equity: Net worth of a business/asset value to shareholders.

- Retained earnings: Net profit remaining for a company after all liabilities are paid.

Amazon’s next statement in its quarterly filing is the income statement. The income statement is useful for comparing a company’s growth over time and matching it up against competitors in the same or different sectors.

An essential factor to note when looking at a company’s income statement is whether its revenue and net income are consistently growing year over year. Investors should also be aware of Wall Street expectations, as they can heavily influence the business’s share price.

Many important ratios are used when analyzing a company’s income statement. Some of the most notable ones include:

- EV/EBITDA = (Market Capitalization + Debt - Cash) / (Revenue - Cost of Goods Sold - Operating Expenses)

- Gross Margin = (Revenue - Cost of Goods Sold) / Revenue

- Operating Margin = Operating Income / Revenue

- Net Margin = Net Income / Revenue

- Return on Equity (ROE) = Net Income / Average Shareholder Equity (End Value + Beginning Value / 2)

- Earnings Per Share = Net Income / Shares Outstanding

Let’s use these ratios to conduct a comparables analysis between Amazon and eBay, a company at a much lower valuation relative to the e-commerce giant. Here are their ratios side-by-side, as of Amazon’s Q1 2023 and eBay’s Q1 2023 filings:

| Ratio | Amazon | eBay |

|---|---|---|

| 25.3x | 8.4x | |

| Gross Margin | 46.8% | 72.1% |

| Operating Margin | 3.75% | 29.1% |

| Net Margin | 2.49% | 22.6% |

| -1.86% | -24.6% | |

| Earnings Per Share | -$0.27 | $1.05 |

* = EV/EBITDA ratios sourced from finbox.com , March 2023 trailing twelve months (TTM)

Looking at these statistics on paper, it is clear to see that Amazon seems overvalued compared to eBay due to lower margins, negative earnings per share, and an EV/EBITDA multiple over three times as high as the business.

However, pure stats on an income statement cannot fully justify purchasing one company or another. The statement merely shows what a company is doing without a corporate spin.

One thing to note that is unique about Amazon’s business model is how the company invests huge amounts of capital into R&D and technology to expand its operations continuously.

Their numbers don’t account for the massive cash flows and growth opportunities that the business takes advantage of.

When conducting fundamental analysis, an investor must consider all aspects of a business beyond the financial statements, including comparing business models to competitors and setting benchmarks encompassing the overall sector.

Amazon’s cash flow statement is where the company begins to shine compared to its competitors in the online commerce sector. The company has consistently increased cash flow from operating activities and constantly returns value to shareholders in the form of capital appreciation.

It is notable for focusing on what the company is doing inside of its cash flow statements to get a better picture of why its income or stock price is trending a certain way.

For example, an explosive drop in net income in an otherwise stable company could be due to mismanagement or hampered growth but is most likely due to M&A activity charged in a quarter that may be skewing the numbers. The cash flow statement clears this up.

Compared to 2022, Amazon has increased its annual cash from operating activities by over 38% from the previous year based on a 12-month rolling basis.

This increase has also resulted in an 11.7% increase in investment expenditures, which should allow Amazon to continue growing faster than similar companies.

In comparison, according to eBay’s most recent 10-K filing , the company generated an 82% growth in operating cash flow (OCF), however, this stat can be very misleading due to the company’s lack of investment in processes such as R&D and SG&A.

In 2022, the company reported $92M in investing activities, representing only 26% of operating cash flows. Amazon reported over $37.6B in investing activities representing approximately 88% of its OCF.

The income statement can misrepresent how well a company is doing, as while eBay has a higher net income, Amazon strategically reinvests its cash flows into R&D and other expenses to produce more over time continuously.

What makes the cash flow statement so essential to fundamental analysis is the fact that it is tough to manipulate its numbers through financial engineering or clever accounting.

The statement purely shows precisely where all of the money a company makes is being used. Many investors use the cash flow statement to tell the true financial health of a business, as profits can often not be indicative of a growth company's value.

The stock price of a company can easily be swayed by sentiment or the market cycle , and the income statement can be skewed through large one-time transactions or large amounts of financed revenue. The amount of money in the possession of a company is very hard to adjust.

Amazon currently has much better growth prospects than eBay and thus sells at a higher premium in the open market , but you wouldn’t understand why unless you took in the full picture of the company.

Everything You Need To Master Valuation Modeling

To Help You Thrive in the Most Prestigious Jobs on Wall Street.

Financial statements are excellent tools to learn more about a business in terms of an overall market or sector of operation. Using financial statements to determine the current value of a business is essential for understanding a company’s stock price.

Along with the ratios mentioned, analysts often form their methodologies over time to focus on companies that are strong in specific financial circumstances.

Tools such as stock screeners can sort millions of companies by certain factors. For instance, some investors may seek defensive companies with consistent dividend growth over long periods, while others may seek growth companies with the most innovative new technology.

Investors should keep all of this information in mind, as well as pay attention to the reports of analysts with varied performance outlooks. It is essential to seek out the opinions of multiple sources before establishing an opinion on a business.

Looking at reports from analysts specializing in the industry can also ensure that your expectations are reasonable compared to industry experts.

If your thesis results in Amazon growing its revenues by 20% a year while analysts across the country are only expecting growth in the range of 5-7%, it could be a sign that you may have overlooked a key factor in your due diligence .

The overall goal of using financial statements is to fully understand the company you are investing in to justify a position. Although your views may slightly differ from experts, quality due diligence can result in somewhat varied outcomes based on an investor’s outlook for the future.

Using EBITDA instead of net income strips away the capital structure and taxation of a business to analyze the pure earnings potential of a business. This is more practical for investors to see the general trajectory of a company’s income over time.

For example, companies may decide on completing a merger or acquiring another company. This will require a company to report its current and acquired assets on its balance sheet .

Over time, these assets must be recorded as expenses through the use of depreciation, which is the process of deducting from gross revenue to account for the decreasing value of company plant assets.

If these assets increase in value over time, this could decrease revenues over time not due to company performance but because of increased prices for equipment outside of the company’s control.

Without looking at EBITDA, company financials may paint a completely different picture with the use of net income that may or may not be justified at all.

ROE is an important metric to distinguish how good a company is at generating profits with investor capital compared to its share price and competitors. It is yet another indicator used to analyze the trajectory of a business over time.

Using ROE can also demonstrate how much financing a company requires to generate its revenue and if investors are really getting a great return for the amount of money shareholders contribute.

A startup that has recently gone public on the stock exchange may have a very low to negative ROE compared to an established company. Still, the startup may have the margins and growth to justify its valuation .

Much like every financial ratio, ROE doesn’t demonstrate the entire story of a business, and the full picture of a business must be considered to decide on an equity investment.

To proliferate and take market share from competitors , Amazon undercuts prices on many products to decrease competition and remain the top player in the industry.

Amazon, like many other companies recently since the pandemic, has also faced significant increases in operating expenses , thus lowering operating and net margins in the short term. Once Amazon begins to slow expansion, these margins are expected to rise.

Amazon’s net income is very low for many of the same reasons. The company is profitable yet is constantly reinvesting into new businesses and products to further grow cash flows for future expenditures.

Amazon investors are not focused on income but rather on its ability to continuously grow in the long term. Growth companies like Amazon do not issue dividends because they believe that the money is better reinvested in business operations.

Everything You Need To Master Financial Statement Modeling

To Help you Thrive in the Most Prestigious Jobs on Wall Street.

Researched and Authored by Tanner Hertz | LinkedIn

Free Resources

To continue learning and advancing your career, check out these additional helpful WSO resources:

- Accounting Conservatism

- Accounting Equation

- Accounting Ratios

- Three Financial Statements in FP&A

- Working Capital Cycle

Get instant access to lessons taught by experienced private equity pros and bulge bracket investment bankers including financial statement modeling, DCF, M&A, LBO, Comps and Excel Modeling.

or Want to Sign up with your social account?

Financial Statement Analysis by Wallace Davidson III

Get full access to Financial Statement Analysis and 60K+ other titles, with a free 10-day trial of O'Reilly.

There are also live events, courses curated by job role, and more.

Chapter 6 Case Studies

Learning objective.

- Recall measures that are useful in the analysis of financial statements and data.

The following four case studies provide examples of financial information upon which liquidity, leverage, profitability, and casual calculations may be performed. The first two case studies also contain example ratio summary and analysis. Considering this information, what problem areas regarding each company’s financial health exist?

Two discussion cases are also provided, followed by questions related to the financial condition of the subject company.

Case study 1: Paper products company

| Cash | $550,000 | $450,000 | $150,000 | $ 50,000 | |

| Receivables | 800,000 | 750,000 | 750,000 | 700,000 | |

| Inventory | 900,000 | 850,000 | 850,000 | 800,000 | |

| All other | 250,000 | 250,000 | 250,000 | 250,000 | |

| Total current | 2,500,000 | 2,300,000 | 2,000,000 | 1,800,000 | |

| Fixed | 1,500,000 | 1,450,000 | 1,400,000 | 1,300,000 | |

| All other | 500,000 | 500,000 | 400,000 | 300,000 | |

| Total assets | $4,500,000 | $4,250,000 | $3,800,000 | $3,400,000 | |

| Due banks | $400,000 | $400,000 | $400,000 | $400,000 | |

| Due trade | 400,000 | 500,000 | 700,000 | 1,050,000 | |

| Taxes | 100,000 | -0- | -0- | -0- | |

| All other | -0- | -0- | -0- | -0- | |

| Total current | 900,000 | 900,000 | 1,100,000 | 1,450,000 | |

| Long-term liabilities | 600,000 | 550,000 | 500,000 | 450,000 | |

| Total liabilities | 1,500,000 | 1,450,000 | 1,600,000 | 1,900,000 | |

| Net worth | 3,000,000 | 2,800,000 | 2,200,000 | 1,500,000 | |

| Total | $4,500,000 | $4,250,000 | $3,800,000 ... | ||

Get Financial Statement Analysis now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.

Don’t leave empty-handed

Get Mark Richards’s Software Architecture Patterns ebook to better understand how to design components—and how they should interact.

It’s yours, free.

Check it out now on O’Reilly

Dive in for free with a 10-day trial of the O’Reilly learning platform—then explore all the other resources our members count on to build skills and solve problems every day.

- Search Search Please fill out this field.

- Financial Statement Analysis

- How It Works

Types of Financial Statements

Financial performance.

- Financial Statement Analysis FAQs

- Corporate Finance

- Financial statements: Balance, income, cash flow, and equity

Financial Statement Analysis: How It’s Done, by Statement Type

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/wk_headshot_aug_2018_02__william_kenton-5bfc261446e0fb005118afc9.jpg)

Katrina Ávila Munichiello is an experienced editor, writer, fact-checker, and proofreader with more than fourteen years of experience working with print and online publications.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/KatrinaAvilaMunichiellophoto-9d116d50f0874b61887d2d214d440889.jpg)

What Is Financial Statement Analysis?

Financial statement analysis is the process of analyzing a company’s financial statements for decision-making purposes. External stakeholders use it to understand the overall health of an organization and to evaluate financial performance and business value. Internal constituents use it as a monitoring tool for managing the finances.

Key Takeaways

- Financial statement analysis is used by internal and external stakeholders to evaluate business performance and value.

- Financial accounting calls for all companies to create a balance sheet, income statement, and cash flow statement, which form the basis for financial statement analysis.

- Horizontal, vertical, and ratio analysis are three techniques that analysts use when analyzing financial statements.

Jiaqi Zhou / Investopedia

How to Analyze Financial Statements

The financial statements of a company record important financial data on every aspect of a business’s activities. As such, they can be evaluated on the basis of past, current, and projected performance.

In general, financial statements are centered around generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP) in the United States. These principles require a company to create and maintain three main financial statements: the balance sheet, the income statement, and the cash flow statement. Public companies have stricter standards for financial statement reporting. Public companies must follow GAAP, which requires accrual accounting. Private companies have greater flexibility in their financial statement preparation and have the option to use either accrual or cash accounting.

Several techniques are commonly used as part of financial statement analysis. Three of the most important techniques are horizontal analysis , vertical analysis , and ratio analysis . Horizontal analysis compares data horizontally, by analyzing values of line items across two or more years. Vertical analysis looks at the vertical effects that line items have on other parts of the business and the business’s proportions. Ratio analysis uses important ratio metrics to calculate statistical relationships.

Companies use the balance sheet, income statement, and cash flow statement to manage the operations of their business and to provide transparency to their stakeholders. All three statements are interconnected and create different views of a company’s activities and performance.

Balance Sheet

The balance sheet is a report of a company’s financial worth in terms of book value. It is broken into three parts to include a company’s assets , liabilities , and shareholder equity . Short-term assets such as cash and accounts receivable can tell a lot about a company’s operational efficiency; liabilities include the company’s expense arrangements and the debt capital it is paying off; and shareholder equity includes details on equity capital investments and retained earnings from periodic net income. The balance sheet must balance assets and liabilities to equal shareholder equity. This figure is considered a company’s book value and serves as an important performance metric that increases or decreases with the financial activities of a company.

Income Statement

The income statement breaks down the revenue that a company earns against the expenses involved in its business to provide a bottom line, meaning the net profit or loss. The income statement is broken into three parts that help to analyze business efficiency at three different points. It begins with revenue and the direct costs associated with revenue to identify gross profit . It then moves to operating profit , which subtracts indirect expenses like marketing costs, general costs, and depreciation. Finally, after deducting interest and taxes, the net income is reached.

Basic analysis of the income statement usually involves the calculation of gross profit margin, operating profit margin, and net profit margin, which each divide profit by revenue. Profit margin helps to show where company costs are low or high at different points of the operations.

Cash Flow Statement

The cash flow statement provides an overview of the company’s cash flows from operating activities, investing activities, and financing activities. Net income is carried over to the cash flow statement, where it is included as the top line item for operating activities. Like its title, investing activities include cash flows involved with firm-wide investments. The financing activities section includes cash flow from both debt and equity financing. The bottom line shows how much cash a company has available.

Free Cash Flow and Other Valuation Statements

Companies and analysts also use free cash flow statements and other valuation statements to analyze the value of a company . Free cash flow statements arrive at a net present value by discounting the free cash flow that a company is estimated to generate over time. Private companies may keep a valuation statement as they progress toward potentially going public.

Financial statements are maintained by companies daily and used internally for business management. In general, both internal and external stakeholders use the same corporate finance methodologies for maintaining business activities and evaluating overall financial performance .

When doing comprehensive financial statement analysis, analysts typically use multiple years of data to facilitate horizontal analysis. Each financial statement is also analyzed with vertical analysis to understand how different categories of the statement are influencing results. Finally, ratio analysis can be used to isolate some performance metrics in each statement and bring together data points across statements collectively.

Below is a breakdown of some of the most common ratio metrics:

- Balance sheet : This includes asset turnover, quick ratio, receivables turnover, days to sales, debt to assets, and debt to equity.

- Income statement : This includes gross profit margin, operating profit margin, net profit margin, tax ratio efficiency, and interest coverage.

- Cash flow : This includes cash and earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization (EBITDA) . These metrics may be shown on a per-share basis.

- Comprehensive : This includes return on assets (ROA) and return on equity (ROE) , along with DuPont analysis .

What are the advantages of financial statement analysis?

The main point of financial statement analysis is to evaluate a company’s performance or value through a company’s balance sheet, income statement, or statement of cash flows. By using a number of techniques, such as horizontal, vertical, or ratio analysis, investors may develop a more nuanced picture of a company’s financial profile.

What are the different types of financial statement analysis?

Most often, analysts will use three main techniques for analyzing a company’s financial statements.

First, horizontal analysis involves comparing historical data. Usually, the purpose of horizontal analysis is to detect growth trends across different time periods.

Second, vertical analysis compares items on a financial statement in relation to each other. For instance, an expense item could be expressed as a percentage of company sales.

Finally, ratio analysis, a central part of fundamental equity analysis, compares line-item data. Price-to-earnings (P/E) ratios, earnings per share, or dividend yield are examples of ratio analysis.

What is an example of financial statement analysis?

An analyst may first look at a number of ratios on a company’s income statement to determine how efficiently it generates profits and shareholder value. For instance, gross profit margin will show the difference between revenues and the cost of goods sold. If the company has a higher gross profit margin than its competitors, this may indicate a positive sign for the company. At the same time, the analyst may observe that the gross profit margin has been increasing over nine fiscal periods, applying a horizontal analysis to the company’s operating trends.

Congressional Research Service. “ Cash Versus Accrual Basis of Accounting: An Introduction ,” Page 3 (Page 7 of PDF).

Internal Revenue Service. “ Publication 538 (01/2022), Accounting Periods and Methods: Methods You Can Use. ”

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Vertical_analysis_final-5a1448af9904473f97b5438ad4bd17fd.png)

- Terms of Service

- Editorial Policy

- Privacy Policy

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

Financial analysis

- Finance and investing

- Corporate finance

When Providing Wait Times, It Pays to Underpromise and Overdeliver

- October 21, 2020

Strategic Analysis for More Profitable Acquisitions

- Alfred Rappaport

- From the July 1979 Issue

Using APV: A Better Tool for Valuing Operations

- Timothy A. Luehrman

- From the May–June 1997 Issue

Pitfalls in Evaluating Risky Projects

- James E. Hodder

- Henry E. Riggs

- From the January 1985 Issue

The Other Diversity Dividend

- Paul A. Gompers

- Silpa Kovvali

- From the July–August 2018 Issue

CEOs Don’t Care Enough About Capital Allocation

- José Antonio Marco-Izquierdo

- April 16, 2015

What Your Innovation Process Should Look Like

- Pete Newell

- Steve Blank

- September 11, 2017

How to Create a Stakeholder Strategy

- Darrell Rigby

- Dunigan O'Keeffe

- From the May–June 2023 Issue

A Better Way to Assess Managerial Performance

- Mihir A. Desai

- Scott Mayfield

- From the March–April 2022 Issue

The CEO View: Defending a Good Company from Bad Investors

- David Pyott

- Sarah Cliffe

- From the May–June 2017 Issue

What Net Present Value Can't Tell You

- Maxwell Wessel

- November 20, 2014

Do You Know Your Cost of Capital?

- Michael T. Jacobs

- Anil Shivdasani

- From the July–August 2012 Issue

Today’s Options for Tomorrow’s Growth

- W. Carl Kester

- From the March 1984 Issue

What’s It Worth?: A General Manager’s Guide to Valuation

How much should a corporation earn.

- John J. Scanlon

- From the January 1967 Issue

“Showcase Projects” Can Deepen Your Relationships with Profitable Customers

- Jonathan Byrnes

- October 05, 2021

The Board View: Directors Must Balance All Interests

- Barbara H. Franklin

M&A Needn’t Be a Loser’s Game

- Larry Selden

- Geoffrey Colvin

- From the June 2003 Issue

Startups Could Fundamentally Change the Way Big Investors Operate

- Daniel Nadler

- October 24, 2016

The Best-Performing CEOs in the World

- Harvard Business Review Staff

- From the November 2016 Issue

Mercury Athletic: Valuing the Opportunity

- Joel L. Heilprin

- September 18, 2009

Roche: ESG and Access to Healthcare

- George Serafeim

- Susanna Gallani

- Benjamin Maletta

- March 08, 2023

Hyflux Ltd in Financial Distress

- Shirley Koh

- Yin Kheng Lau

- June 10, 2019

Baupost Group: Finding a Margin of Safety in London Real Estate

- Adi Sunderam

- Luis M. Viceira

- Shawn O'Brien

- Franklin Muanankese

- May 30, 2018

Note on Valuation for Venture Capital

- Tevya Rosenberg

- March 23, 2009

Valuation of AirThread Connections

- Erik Stafford

- March 01, 2011

A Primer on OKRs

- Suraj Srinivasan

- March 22, 2023

Science Technology Co.--1985

- Thomas R. Piper

- February 02, 1989

Identifying Value Creators

- Su Han Chan

- January 11, 2002

Mira's Microbrewery Inc.

- Paul M. Healy

- Marshal Herrmann

- July 15, 2020

Designing Executive Compensation at Kongsberg Automotive (A)

- Quinn Pitcher

- July 10, 2018

Ahold versus Tesco--Analyzing Performance

- Penelope Rossano

- September 18, 2012

Tata Motors: Can the Turnaround Plan Improve Performance?

- Shernaz Bodhanwala

- Ruzbeh Bodhanwala

- January 14, 2020

Health Development Corp.

- Richard S. Ruback

- May 04, 2000

Boeing 737 Manufacturing Footprint: The Wichita Decision

- Margaret Pierson

- October 05, 2011

Financial Accounting: A Self-Paced Learning Program: Advanced Section

- David F. Hawkins

- January 08, 2010

Cathay Pacific: Financial Impact and Challenges in Adopting the New Lease Accounting Standard

- Winnie S.C. Leung

- Tsun-kan Wan

- August 27, 2020

Histograms and the Normal Distribution in Microsoft Excel

- Kyle Maclean

- Lauren E. Cipriano

- Gregory S. Zaric

- July 04, 2016

Vyaderm Pharmaceuticals: The EVA Decision

- Robert Simons

- Indra A. Reinbergs

- October 04, 2000

Mahindra Finance

- V.G. Narayanan

- Tanvi Deshpande

- March 25, 2019

How Accountants Measure Opportunity

- Daniel Marburger

- Ryan Peterson

- September 01, 2013

Are You a Better Decision Maker . . . Yet?

Dhahran Roads (B), Teaching Note

- Sherwood C. Jr. Frey

- April 30, 1994

High-Ratio Stock Splits: Profit Cultural & Creative Group vs. Wolwo Bio-Pharmaceutical, Teaching Note

- Shimin Chen

- Xiayan Huang

- June 30, 2019

Popular Topics

Partner center.

GPT-4 is better than humans at financial forecasting, new study shows

- OpenAI's GPT-4 is better than humans at analyzing financial statements and making forecasts, according to a new study.

- "Even without any narrative or industry-specific information, the LLM outperforms financial analysts in its ability to predict earnings changes," the study found.

- Trading strategies based on GPT-4 also delivered more profitable results than the stock market.

OpenAI's GPT-4 proved to be a better financial analyst than humans, according to a new study.

The findings could upend the financial services industry that, like other business sectors, is racing to adopt generative AI technologies.

According to the study conducted by the Booth School of Business at the University of Chicago, the large language model did a better job of analyzing financial statements and making predictions based on those statements.

"Even without any narrative or industry-specific information, the LLM outperforms financial analysts in its ability to predict earnings changes," the study said. "The LLM exhibits a relative advantage over human analysts in situations when the analysts tend to struggle."

The study utilized "chain-of-thought" prompts that directed GPT-4 to identify trends in financial statements and calculate different financial ratios. From there, the large language model analyzed the information and predicted future earnings results.

"When we use the chain of thought prompt to emulate human reasoning, we find that GPT achieves an accuracy of 60%, which is remarkably higher than that achieved by the analysts," the study said. The human analysts were closer to the low 50% range with regard to prediction accuracy.

The large language models' ability to recognize financial patterns and business concepts with incomplete information suggests that the technology should play a key role in financial decision-making going forward, according to the study's authors.

Finally, the study found that applying GPT-4's financial acumen to trading strategies produced more profitable trading, with higher share ratios and alpha that ultimately beat the stock market.

"We find that the long-short strategy based on GPT forecasts outperforms the market and generates significant alphas and Sharpe ratios," the study said.

- Main content

The independent source for health policy research, polling, and news.

Gaps in Data About Hospital and Health System Finances Limit Transparency for Policymakers and Patients

Scott Hulver , Zachary Levinson , Jamie Godwin , Gary Claxton , and Tricia Neuman Published: Mar 22, 2024

Hospitals account for 30% of total health care spending—$1.4 trillion in 2022—with expenditures projected to rise rapidly through 2031, contributing to higher costs for families, employers, Medicare, Medicaid, and other public payers. As policymakers consider a variety of strategies to make health care more affordable, there is growing interest in understanding the factors that drive hospital and health system spending. Some policymakers at the federal and state level are pursuing strategies to reduce the burden of hospital costs, including efforts to establish site-neutral payments, limit the prices that hospitals may charge commercial insurers relative to Medicare rates, promote greater competition in hospital markets, and introduce standards for hospital debt collection practices and charity care programs.

This issue brief describes gaps in data about hospital and health system finances and business practices that limit transparency for policymakers, researchers, and consumers. Each section discusses the main sources of data that are available, reviews the strengths and weaknesses of each, and identifies gaps in these data. The following list includes examples of basic questions about hospitals that cannot be fully answered, either because the data do not exist; are not collected in a single, comprehensive source; or have important limitations:

- Which hospitals and health systems are in the greatest need of government support based on profitability, days cash on hand, payer mix, and other factors? A number of existing sources provide some level of information about these indicators, but each has its own limitations. For example, it can be difficult to accurately calculate measures of profitability from Medicare cost report data and compare them across hospitals due to missing or unstandardized details (see Table 1 for specifics). Medicare cost reports also do not include data about the health system that owns a given hospital—so may be missing information necessary to calculate days cash on hand—and they cannot be used to identify the extent to which a hospital treats commercial or uninsured patients. Finally, as a result of lags in reporting, most data may not be timely enough to address urgent policy questions, such as which hospitals need an infusion of funds following unexpected crises (e.g., following a cyberattack on billing systems or a public health crisis).

- Which hospitals and health systems engage in aggressive debt collection practices (such as suing patients), how often do they do so, and what are the characteristics of the patients who are targeted by these actions (such as their race and ethnicity and whether they reside in urban or rural areas)? Neither Medicare cost reports nor IRS Form 990s—the main public sources of data on hospital and health system finances—provide data to answer these questions, nor does any other known source.

- What are the characteristics of hospitals and health systems that deny a large share of charity care applications or take a long time to approve eligible patients for assistance? What are the characteristics of patients who received or were denied charity care? Neither Medicare cost reports nor IRS Form 990s provide data to answer these questions, nor does any other known source. Medicare cost reports now collect data about the number of patients who receive charity care but not about their characteristics, the number of application denials, the reasons for denials, or review times.

- Which hospitals and health systems charge the most or least for a defined set of services in a given region? Recent federal rules require hospitals and payers to disclose the prices negotiated with commercial plans, among other things, but researchers have documented a number of limitations to these data, making it difficult to make apples to apples comparisons across providers. Researchers also use claims data to compare provider prices, but there is no source that includes claims from all payers (such as a federal all-payer claims database).

- Which health systems have acquired the most physician practices in recent years? A number of data sources provide some level of information about ownership and consolidation, but none provide a comprehensive record of ownership and consolidation across the health system. For example, merging providers must report their plans in advance to the FTC and DOJ in certain cases where the transaction exceeds a specified value ($119.5 million in 2024), but most acquisitions of physician practices or groups fall below this threshold.

- What are the characteristics of 340B hospitals that benefit the most and least from the 340B program? We are unaware of any comprehensive, publicly-available dataset that documents how much each 340B hospital benefits from the program, such as the estimated savings relative to what the provider would have otherwise paid for 340B drugs.

Each of the sections below provides examples of options that could be considered to fill data gaps and improve transparency, such as by adding new reporting requirements to Medicare cost reports. Requiring hospitals and health systems to provide additional information would help strengthen the capacity of policymakers to target funds more efficiently and conduct oversight, but would also create new administrative burdens for providers, some of which are facing financial challenges. Whether or not to beef up data reporting related to hospital and health system finances, charity care, and other policy issues will depend on how policymakers weigh the value of greater transparency against the potential costs imposed on providers, as well as on the government and other payers, as applicable.

There is no comprehensive, accurate, and readily accessible source of information that can be used to address basic questions about the financial health or distress of hospitals and health systems

Accurate, timely, and comprehensive information about the finances of hospitals and health systems—such as whether they are profitable, the extent to which they have the capacity to cover losses with existing financial reserves in an emergency, and how burdened they are with debt—is lacking. Such information would give policymakers additional tools to modify payment policy and conduct regulatory oversight. For instance, these data could help policymakers better determine the adequacy of Medicare and Medicaid reimbursements, identify hospitals that are financially vulnerable that may require additional government support to maintain services needed in their communities, assess the extent to which nonprofit hospitals reinvest earnings into their communities, and predict how payment reforms are likely to impact hospitals’ financial standing. One recent example is that better and more current financial data could have helped policymakers target COVID-19 dollars to, say, hospitals and health systems with limited liquidity heading into the pandemic that may have been especially strained during that period.

A number of existing sources provide some level of information about the finances of hospitals and health systems across the country, including their revenues, expenses, assets, and liabilities (see Table 1 for additional details about the benefits and limitations of each dataset; the following discussion excludes state-specific datasets).

- Medicare cost reports. Hospitals participating in Medicare are required to submit an annual cost report with information about their costs and other key financial information. The Medicare cost reports include data for virtually all (98%) of community hospitals in 2022 based on KFF estimates 1 and provide useful and relatively standardized information about hospital expenses. However, other financial information is less detailed or standardized, which can make it difficult to accurately calculate key measures, like profit margins, and compare them across hospitals (see Table 1). Medicare cost reports are also not subject to the same rigorous auditing process as are audited financial statements (see below). Further, because the data are submitted by individual hospitals, they do not reflect the finances of the health systems that own them (such as their financial reserves, days cash on hand, the amount of debt held by the system, or the financial impact of owning non-hospital entities such as insurance companies and physician practices). Cost report data are generally lagged: as of early March 2024, data were available online for all or nearly all reporting entities through fiscal year 2022 but were usually not available for fiscal year 2023. This means that the most recent year of complete or nearly complete data was typically 14 to 20 months old as of early March 2024 (the range of time reflects the difference in fiscal year reporting periods).

- IRS Form 990. Tax-exempt, nonprofit hospitals and health systems are required to file a Form 990 return annually with the Internal Revenue Service (IRS), which includes financial information—such as measures relating to profitability and financial reserves—along with other information, including CEO compensation and community benefits spending. However, among other limitations, financial information from IRS Form 990s are also not subject to the same rigorous auditing process as audited financial statements and do not include government and for-profit hospitals and health systems. Nonprofit health systems do not typically break out information for individual hospitals, and they may provide information through multiple reports that would need to be combined to evaluate the overall health system. As of early March 2024, IRS Form 990 data were available online in a machine-readable form for all or nearly reporting entities for fiscal year 2021 but were unavailable for most entities for fiscal year 2022.

- Audited financial statements. Many hospitals and health systems publicly release annual audited financial statements, which is a requirement for publicly-traded, for-profit health systems and systems which issue publicly-traded debt. Audited financial statements are considered the gold standard of financial data and can be used to calculate standardized versions of several common financial measures, such as profitability, days cash on hand, and debt burden. However, these data are not easily accessible (e.g., in a machine-readable file), and they typically require laborious, specialized expertise to standardize financial information across systems. Further, audited financial statements often do not break out information about individual hospitals in the common scenario where facilities are part of a broader health system. Although hospital-level data is currently captured for almost all hospitals in the cost reports, there is no data source that contains all system-level data. Based on our experience, audited financial statements tend to be released from two to six months after the end of a given fiscal year, meaning that, as of early March 2024, data were likely available for all or nearly all entities that publish these statements through fiscal year 2022 and were available for many, but not all, through fiscal year 2023.

- Credit rating agency data. Credit rating agencies collect and standardize information from audited financial statements for hospitals and health systems that apply for a credit rating. These data might be available for purchase. However, they cover only a subset of entities and are unlikely to be representative of all hospitals and health systems. These data are available after the release of the underlying audited financial statements.

- Data from third-party financial platforms. Data entered by hospitals into financial management platforms might be purchased from firms that sell this software. These data tend to be the timeliest of all sources, e.g., with monthly data available in the following month. However, the timeliness of these data comes with a tradeoff, as monthly data incorporate estimates that are corrected over time and are therefore less accurate than annual data. Further, these data are generated from a subset of hospitals which may not be representative. These data are likely shared at an aggregated level to protect the identity of individual hospitals.

Financial data entail tradeoffs between accuracy and timeliness. For example, audited financial statements are the most accurate data but they are often lagged by several months and reflect annual data, while data from third-party financial platforms are typically quite timely and reflect monthly financial data, but may be less accurate because they rely in part on estimates and are not audited. As a result, it can be challenging to address urgent policy questions, such as which hospitals need an infusion of funds following unexpected crises (e.g., following a cyberattack on billing systems or a public health crisis) with available data, since each source has problems with either timeliness or accuracy.

Among other data gaps, we are unaware of any public data with comprehensive and consistently-defined information on payer mix—i.e., the share of business that comes from different payers, including Medicare, Medicaid, commercial insurers, the uninsured, and others—that covers all hospitals and health systems in the country. For example, while cost report data include information about Medicare and Medicaid charges, revenues (actual payments), and inpatient days and discharges, they do not identify these amounts for commercial patients and the uninsured.

Further, although more than half of eligible Medicare beneficiaries were enrolled in Medicare Advantage in 2023, cost reports do not separately identify Medicare Advantage revenues and charges, though they do so for Medicare Advantage inpatient days and discharges. Payer mix, including all major payer categories, would help to assess the financial position of a hospital or health system, given that commercial plans tend to reimburse at higher rates than Medicare and Medicaid. Payer mix data could also help to identify and target support to safety-net hospitals.

Key Questions That Cannot Be Fully Answered:

- Which hospitals and health systems are in the greatest need of government support based on profitability, days cash on hand, payer mix, and other factors?

- How profitable were hospitals in the past year and why?

- Which hospitals or health systems are well-positioned to weather unforeseeable fiscal challenges, such as a pandemic?

- How much revenue do hospitals receive from Medicare Advantage patients, and how does the share of revenue attributable to Medicare Advantage patients vary across hospitals?

Options to Fill Gaps in Data and Improve Transparency

Federal policymakers could create a national database with information from all hospitals and health systems that receive any payments from the federal government, with standardized, system-level financial data. To do so, the government could provide hospitals and health systems with financial reports to complete, with detailed templates and instructions describing how to pull information from audited financial statements and other sources. Hospitals and health systems could be required to submit these reports on a timely basis and to provide similar reports based on unaudited quarterly financial statements to provide preliminary information about recent trends. Policymakers could also decide whether to require health systems to report facility-level information for member hospitals.

Alternatively, policymakers could implement narrower changes, such as by modifying Medicare cost reports to collect additional or more precise information about common financial measures. For example:

- Total margins. Hospitals could be required to separate out changes in the value of stock portfolios and other investments (also known as “unrealized investment gains and losses”) from reported revenues, if they are not doing so already, which can have a large effect on reported profits. Hospitals could also be required to separately report nonrecurring income, such as from the sale of assets, which could provide a deeper understanding of changes in profitability.

- Operating margins. Hospitals could be required to directly report total operating revenues, which include both patient-related and other sources of revenue, such as from gift shops, parking, and cafeterias. Currently, operating margins must be approximated by subtracting out nonoperating revenues, such as investment income, from total revenues. This calculation is not straightforward because nonoperating sources of income are not fully separated from broader revenue categories.

- Payer mix. Policymakers could require hospitals to report charges, revenues, and inpatient days and discharges for each major payer—including for commercial, uninsured, and Medicare Advantage patients—to better assess the financial status of hospitals and targets policies and funds efficiently. Given that outpatient services account for a large share of hospital revenues, the charge and revenue amounts could be broken out by inpatient and outpatient services.

Other changes to Medicare cost reports could include collecting quarterly data for a set of key financial measures (such as those needed to calculate profitability and payer mix), as California does, or collecting a subset of system-level measures (such as days of cash on hand) that might alternatively be reported through the national database mentioned above.

Little is known about hospital and health system debt collection practices

About four in ten adults (41%)—and about six in ten (57%) of those with household incomes below $40,000—reported some level of health care debt in a KFF 2022 survey , and a large share of those who reported health care debt cited costs associated with hospitalizations (35%) and emergency care (50%) as sources of unpaid bills. According to KFF Health News , many hospitals engage in aggressive collection practices that can have significant financial consequences for patients, such as suing patients to garnish their wages, placing a lien on their home, reporting a patient’s debt to consumer credit bureaus, and selling their debt to a collection agency (which may in turn take aggressive steps to obtain payment). Hospitals may also encourage patients to enroll in payment plans with high interest rates and deny care to patients with unpaid bills, according to press reports.

However, very little systematic information is available to document the debt collection practices of hospitals and health systems across the country. As part of their annual IRS Form 990 returns, nonprofit hospitals and health systems are required to disclose if they ever engage in certain extraordinary debt collection practices before trying to determine whether a given patient is eligible for charity care, but they do not report whether they engage in these activities more generally or how often they do so. In April 2022, the Biden administration announced that it would gather information from more than 2,000 providers about their “medical bill collection practices, lawsuits against patients, financial assistance, financial product offerings, and 3 rd party contracting [and] debt buying practices.” However, it is not clear which providers will be included or when the findings will be published.

Consumer credit bureaus are another source of information about patient debt, but they only include medical debt that has been reported to these firms, and it may be difficult or impossible to comprehensively trace these data back to specific hospitals or health systems. Finally, some private firms offer software to help providers track billing and collections and, in the process, they may collect data from many hospitals. However, these data only include a subset of facilities, and it is also unlikely that firms would disclose information about any specific client.

Ultimately, little is known about the debt collection practices of hospitals and the medical debt carried by their patients. For example, we are unaware of any comprehensive dataset that identifies, for a given hospital, the number of bills and amount being collected, how much it collects from patients with medical debt, whether it engages in aggressive debt collection practices (such as suing patients), how often it does so, the characteristics of patients who incur medical debt or are affected by aggressive debt collection practices, which collection agency it has a relationship with, how much medical debt it sells to collection agencies, or the amount paid for this debt.

- Which hospitals and health systems engage in aggressive debt collection practices (such as suing patients), how often do they do so, and what are the characteristics of the patients who are targeted by these actions (such as their race and ethnicity and whether they reside in urban or rural areas)?

- How much medical debt have patients incurred from specific hospitals and health systems and what are the characteristics of these patients?

- How much medical debt do hospitals report to credit bureaus?

- How much do hospitals collect when using extraordinary debt collection actions, like litigation?

Policymakers could require hospitals to report and publish additional information about debt collection practices, such as the number of large, unpaid medical bills a hospital is actively trying to collect; the number and type of lawsuits brought against patients; and the number of patients referred to collection agencies (as Colorado requires). Policymakers could also require hospitals to report the characteristics of patients with debt and who are subject to aggressive collection efforts, to the extent such data are available.

It’s unclear how much help hospital charity care programs provide to patients who have difficulty affording their care

Hospital charity care programs —also known as “financial assistance programs”—provide free or discounted services to eligible patients who are unable to afford their care. These programs may be available to uninsured patients, as well as insured patients, whose plans may have large cost-sharing requirements. Hospital charity care programs vary in their eligibility criteria and application procedures. Reporting from KFF Health News indicates that some patients have fallen through the cracks, i.e., were likely eligible for assistance but did not receive it. Improved data collection would allow policymakers and regulators to monitor how charity care programs are working overall and among nonprofit hospitals and health systems, which are expected to provide benefits to the communities they serve in exchange for their tax-exempt status.

Existing data provide some information about eligibility criteria for charity care programs operated by hospitals and health systems and the amount of assistance provided. Nonprofit hospitals and health systems are required to report some eligibility criteria for charity care programs (such as income eligibility thresholds) and aggregate charity care costs as part of their annual IRS Form 990 filings. In addition, all hospitals participating in Medicare—nonprofit, for-profit, and government hospitals—must report charity care charges as part of their annual Medicare cost reports (and convert those charges to costs).