Chapter 18. Data Analysis and Coding

Introduction.

Piled before you lie hundreds of pages of fieldnotes you have taken, observations you’ve made while volunteering at city hall. You also have transcripts of interviews you have conducted with the mayor and city council members. What do you do with all this data? How can you use it to answer your original research question (e.g., “How do political polarization and party membership affect local politics?”)? Before you can make sense of your data, you will have to organize and simplify it in a way that allows you to access it more deeply and thoroughly. We call this process coding . [1] Coding is the iterative process of assigning meaning to the data you have collected in order to both simplify and identify patterns. This chapter introduces you to the process of qualitative data analysis and the basic concept of coding, while the following chapter (chapter 19) will take you further into the various kinds of codes and how to use them effectively.

To those who have not yet conducted a qualitative study, the sheer amount of collected data will be a surprise. Qualitative data can be absolutely overwhelming—it may mean hundreds if not thousands of pages of interview transcripts, or fieldnotes, or retrieved documents. How do you make sense of it? Students often want very clear guidelines here, and although I try to accommodate them as much as possible, in the end, analyzing qualitative data is a bit more of an art than a science: “The process of bringing order, structure, and interpretation to a mass of collected data is messy, ambiguous, time-consuming, creative, and fascinating. It does not proceed in a linear fashion: it is not neat. At times, the researcher may feel like an eccentric and tormented artist; not to worry, this is normal” ( Marshall and Rossman 2016:214 ).

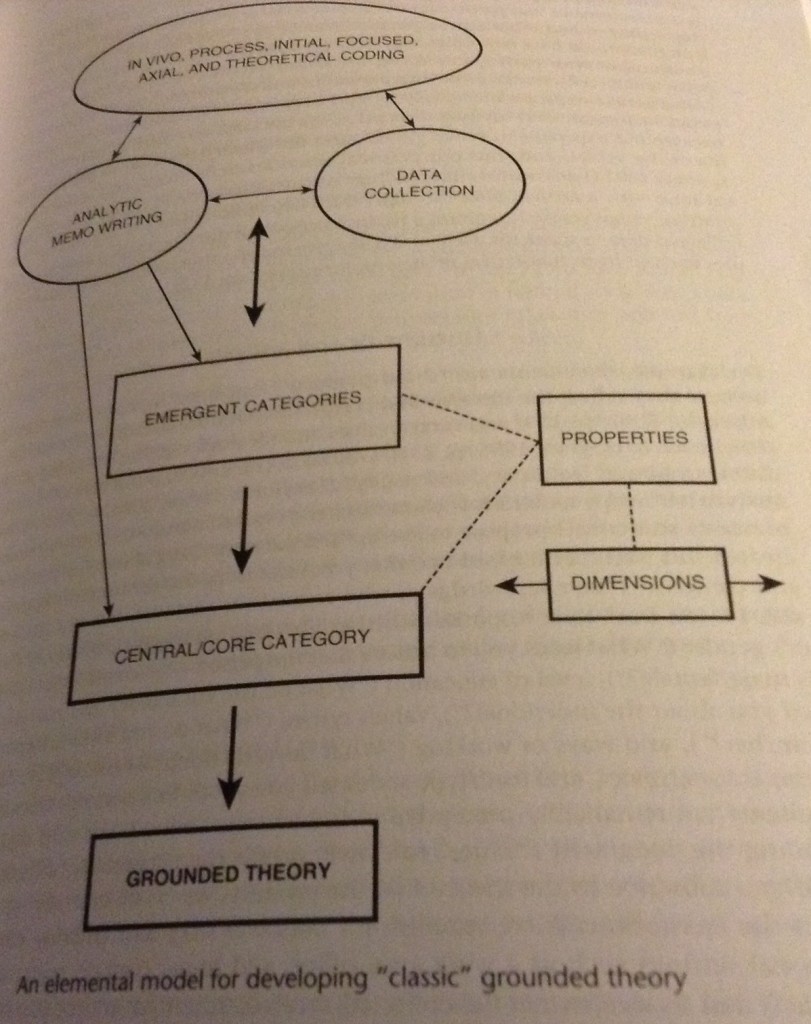

To complicate matters further, each approach (e.g., Grounded Theory, deep ethnography, phenomenology) has its own language and bag of tricks (techniques) when it comes to analysis. Grounded Theory, for example, uses in vivo coding to generate new theoretical insights that emerge from a rigorous but open approach to data analysis. Ethnographers, in contrast, are more focused on creating a rich description of the practices, behaviors, and beliefs that operate in a particular field. They are less interested in generating theory and more interested in getting the picture right, valuing verisimilitude in the presentation. And then there are some researchers who seek to account for the qualitative data using almost quantitative methods of analysis, perhaps counting and comparing the uses of certain narrative frames in media accounts of a phenomenon. Qualitative content analysis (QCA) often includes elements of counting (see chapter 17). For these researchers, having very clear hypotheses and clearly defined “variables” before beginning analysis is standard practice, whereas the same would be expressly forbidden by those researchers, like grounded theorists, taking a more emergent approach.

All that said, there are some helpful techniques to get you started, and these will be presented in this and the following chapter. As you become more of an expert yourself, you may want to read more deeply about the tradition that speaks to your research. But know that there are many excellent qualitative researchers that use what works for any given study, who take what they can from each tradition. Most of us find this permissible (but watch out for the methodological purists that exist among us).

Qualitative Data Analysis as a Long Process!

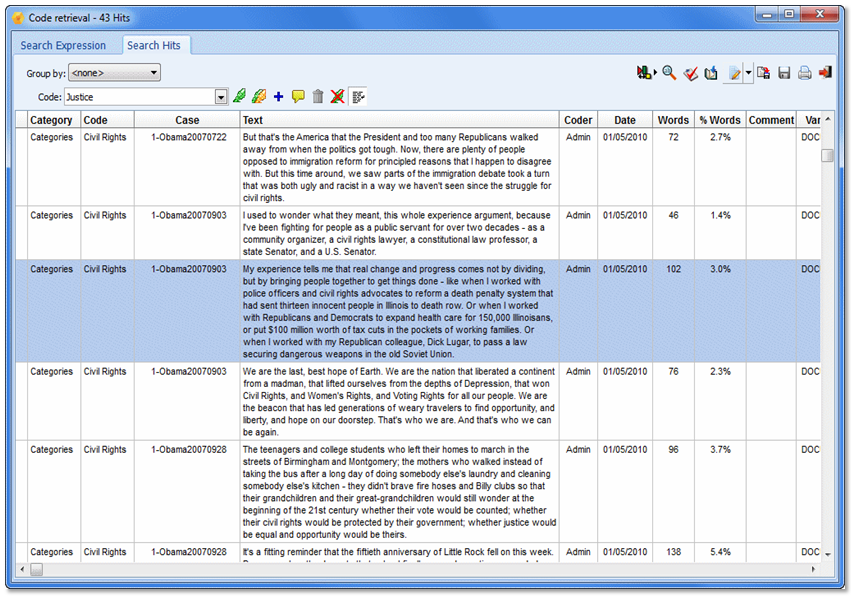

Although most of this and the following chapter will focus on coding, it is important to understand that coding is just one (very important) aspect of the long data-analysis process. We can consider seven phases of data analysis, each of which is important for moving your voluminous data into “findings” that can be reported to others. The first phase involves data organization. This might mean creating a special password-protected Dropbox folder for storing your digital files. It might mean acquiring computer-assisted qualitative data-analysis software ( CAQDAS ) and uploading all transcripts, fieldnotes, and digital files to its storage repository for eventual coding and analysis. Finding a helpful way to store your material can take a lot of time, and you need to be smart about this from the very beginning. Losing data because of poor filing systems or mislabeling is something you want to avoid. You will also want to ensure that you have procedures in place to protect the confidentiality of your interviewees and informants. Filing signed consent forms (with names) separately from transcripts and linking them through an ID number or other code that only you have access to (and store safely) are important.

Once you have all of your material safely and conveniently stored, you will need to immerse yourself in the data. The second phase consists of reading and rereading or viewing and reviewing all of your data. As you do this, you can begin to identify themes or patterns in the data, perhaps writing short memos to yourself about what you are seeing. You are not committing to anything in this third phase but rather keeping your eyes and mind open to what you see. In an actual study, you may very well still be “in the field” or collecting interviews as you do this, and what you see might push you toward either concluding your data collection or expanding so that you can follow a particular group or factor that is emerging as important. For example, you may have interviewed twelve international college students about how they are adjusting to life in the US but realized as you read your transcripts that important gender differences may exist and you have only interviewed two women (and ten men). So you go back out and make sure you have enough female respondents to check your impression that gender matters here. The seven phases do not proceed entirely linearly! It is best to think of them as recursive; conceptually, there is a path to follow, but it meanders and flows.

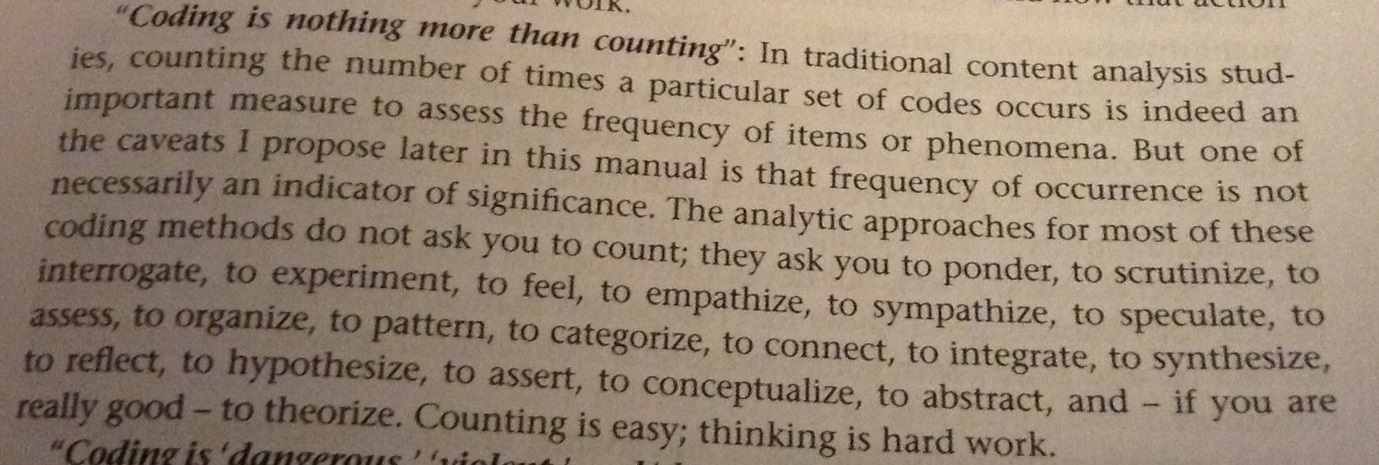

Coding is the activity of the fourth phase . The second part of this chapter and all of chapter 19 will focus on coding in greater detail. For now, know that coding is the primary tool for analyzing qualitative data and that its purpose is to both simplify and highlight the important elements buried in mounds of data. Coding is a rigorous and systematic process of identifying meaning, patterns, and relationships. It is a more formal extension of what you, as a conscious human being, are trained to do every day when confronting new material and experiences. The “trick” or skill is to learn how to take what you do naturally and semiconsciously in your mind and put it down on paper so it can be documented and verified and tested and refined.

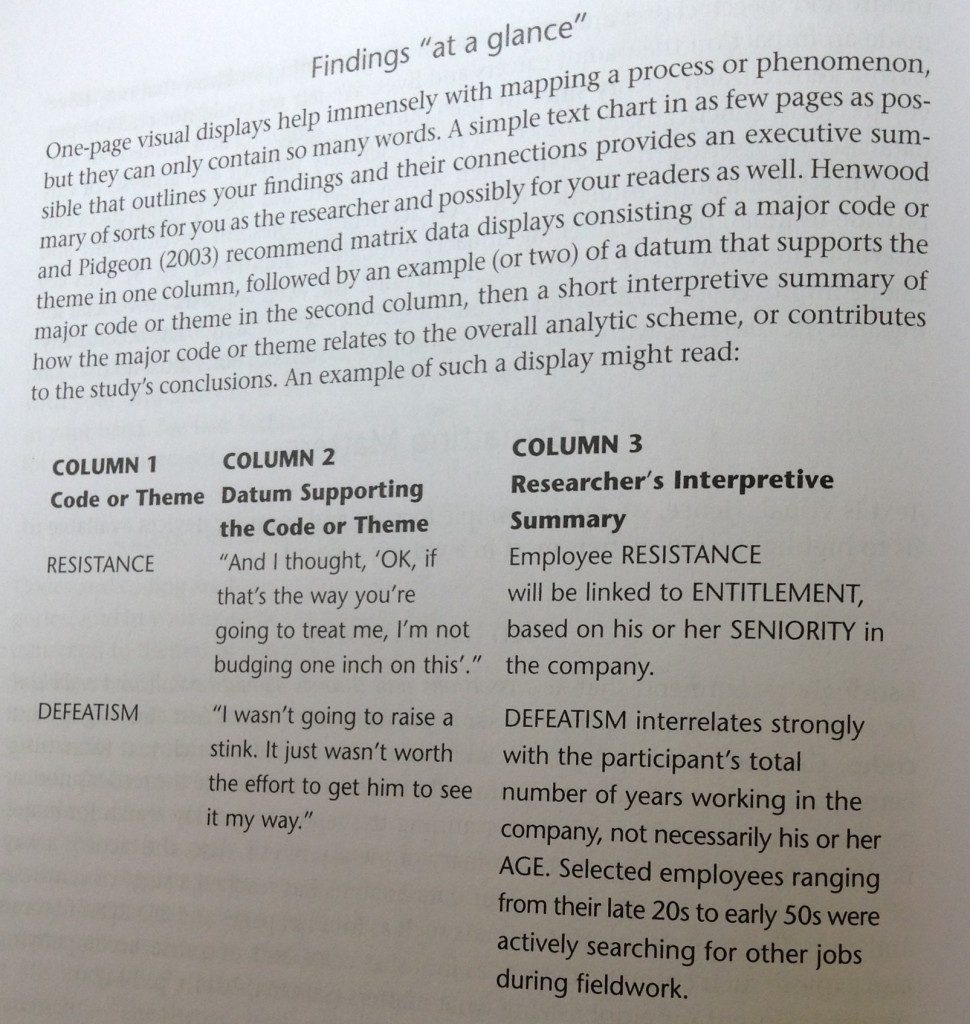

At the conclusion of the coding phase, your material will be searchable, intelligible, and ready for deeper analysis. You can begin to offer interpretations based on all the work you have done so far. This fifth phase might require you to write analytic memos, beginning with short (perhaps a paragraph or two) interpretations of various aspects of the data. You might then attempt stitching together both reflective and analytical memos into longer (up to five pages) general interpretations or theories about the relationships, activities, patterns you have noted as salient.

As you do this, you may be rereading the data, or parts of the data, and reviewing your codes. It’s possible you get to this phase and decide you need to go back to the beginning. Maybe your entire research question or focus has shifted based on what you are now thinking is important. Again, the process is recursive , not linear. The sixth phase requires you to check the interpretations you have generated. Are you really seeing this relationship, or are you ignoring something important you forgot to code? As we don’t have statistical tests to check the validity of our findings as quantitative researchers do, we need to incorporate self-checks on our interpretations. Ask yourself what evidence would exist to counter your interpretation and then actively look for that evidence. Later on, if someone asks you how you know you are correct in believing your interpretation, you will be able to explain what you did to verify this. Guard yourself against accusations of “ cherry-picking ,” selecting only the data that supports your preexisting notion or expectation about what you will find. [2]

The seventh and final phase involves writing up the results of the study. Qualitative results can be written in a variety of ways for various audiences (see chapter 20). Due to the particularities of qualitative research, findings do not exist independently of their being written down. This is different for quantitative research or experimental research, where completed analyses can somewhat speak for themselves. A box of collected qualitative data remains a box of collected qualitative data without its written interpretation. Qualitative research is often evaluated on the strength of its presentation. Some traditions of qualitative inquiry, such as deep ethnography, depend on written thick descriptions, without which the research is wholly incomplete, even nonexistent. All of that practice journaling and writing memos (reflective and analytical) help develop writing skills integral to the presentation of the findings.

Remember that these are seven conceptual phases that operate in roughly this order but with a lot of meandering and recursivity throughout the process. This is very different from quantitative data analysis, which is conducted fairly linearly and processually (first you state a falsifiable research question with hypotheses, then you collect your data or acquire your data set, then you analyze the data, etc.). Things are a bit messier when conducting qualitative research. Embrace the chaos and confusion, and sort your way through the maze. Budget a lot of time for this process. Your research question might change in the middle of data collection. Don’t worry about that. The key to being nimble and flexible in qualitative research is to start thinking and continue thinking about your data, even as it is being collected. All seven phases can be started before all the data has been gathered. Data collection does not always precede data analysis. In some ways, “qualitative data collection is qualitative data analysis.… By integrating data collection and data analysis, instead of breaking them up into two distinct steps, we both enrich our insights and stave off anxiety. We all know the anxiety that builds when we put something off—the longer we put it off, the more anxious we get. If we treat data collection as this mass of work we must do before we can get started on the even bigger mass of work that is analysis, we set ourselves up for massive anxiety” ( Rubin 2021:182–183 ; emphasis added).

The Coding Stage

A code is “a word or short phrase that symbolically assigns a summative, salient, essence-capturing, and/or evocative attribute for a portion of language-based or visual data” ( Saldaña 2014:5 ). Codes can be applied to particular sections of or entire transcripts, documents, or even videos. For example, one might code a video taken of a preschooler trying to solve a puzzle as “puzzle,” or one could take the transcript of that video and highlight particular sections or portions as “arranging puzzle pieces” (a descriptive code) or “frustration” (a summative emotion-based code). If the preschooler happily shouts out, “I see it!” you can denote the code “I see it!” (this is an example of an in vivo, participant-created code). As one can see from even this short example, there are many different kinds of codes and many different strategies and techniques for coding, more of which will be discussed in detail in chapter 19. The point to remember is that coding is a rigorous systematic process—to some extent, you are always coding whenever you look at a person or try to make sense of a situation or event, but you rarely do this consciously. Coding is the process of naming what you are seeing and how you are simplifying the data so that you can make sense of it in a way that is consistent with your study and in a way that others can understand and follow and replicate. Another way of saying this is that a code is “a researcher-generated interpretation that symbolizes or translates data” ( Vogt et al. 2014:13 ).

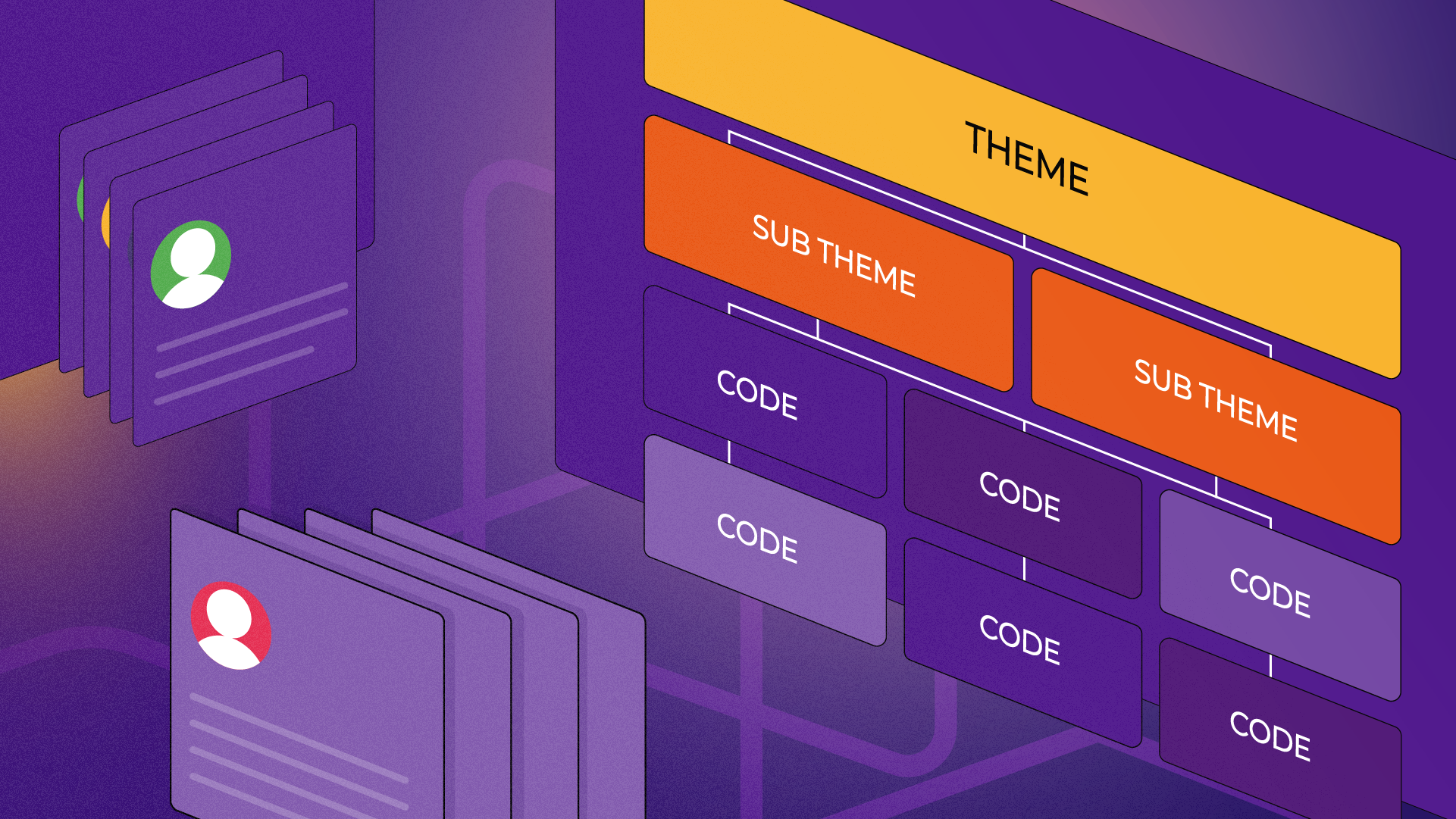

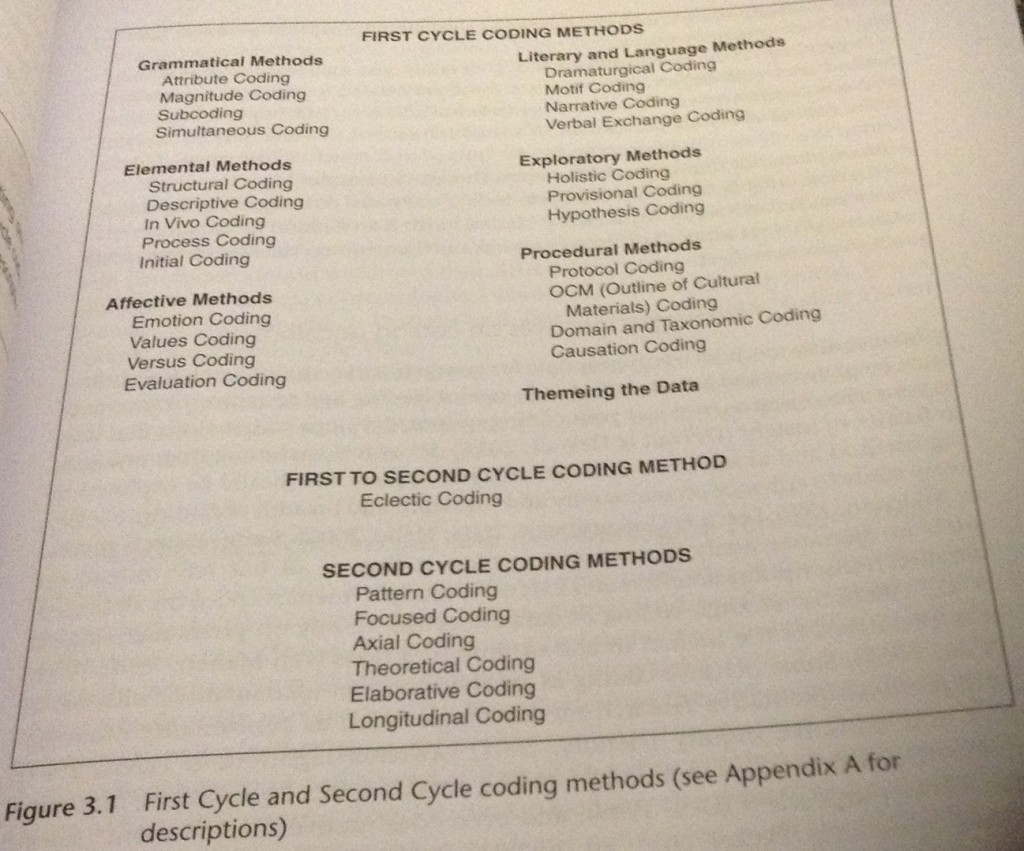

As with qualitative data analysis generally, coding is often done recursively, meaning that you do not merely take one pass through the data to create your codes. Saldaña ( 2014 ) differentiates first-cycle coding from second-cycle coding. The goal of first-cycle coding is to “tag” or identify what emerges as important codes. Note that I said emerges—you don’t always know from the beginning what will be an important aspect of the study or not, so the coding process is really the place for you to begin making the kinds of notes necessary for future analyses. In second-cycle coding, you will want to be much more focused—no longer gathering wholly new codes but synthesizing what you have into metacodes.

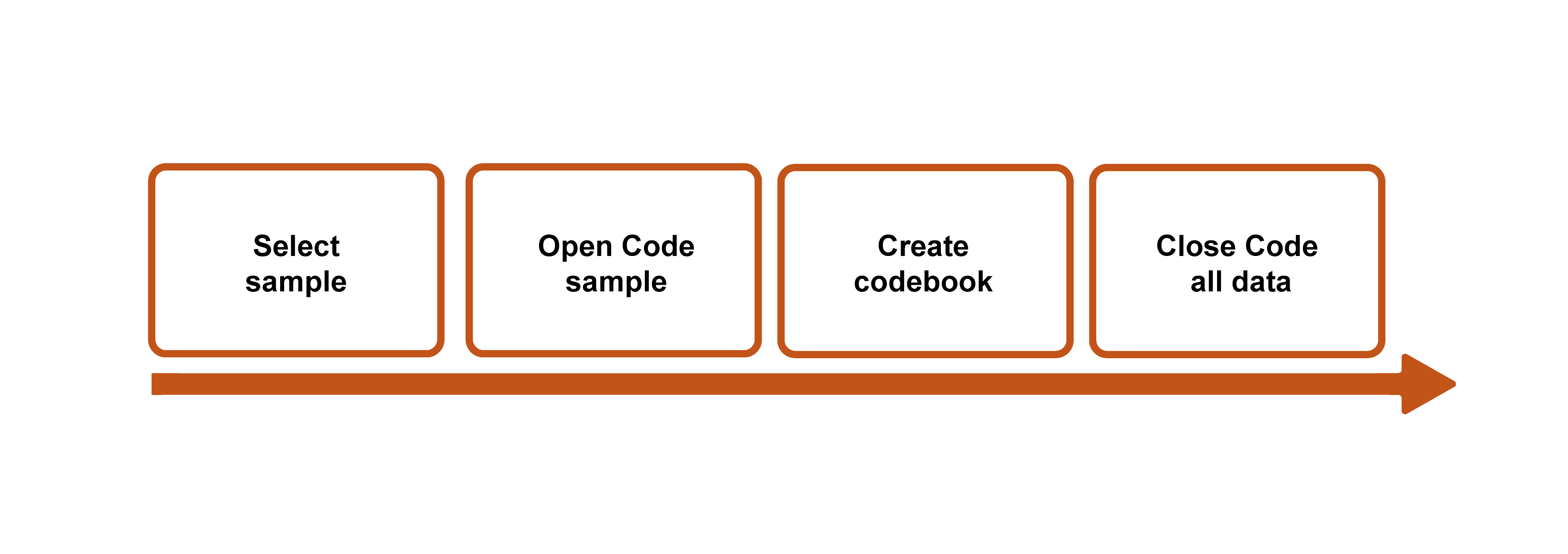

You might also conceive of the coding process in four parts (figure 18.1). First, identify a representative or diverse sample set of interview transcripts (or fieldnotes or other documents). This is the group you are going to use to get a sense of what might be emerging. In my own study of career obstacles to success among first-generation and working-class persons in sociology, I might select one interview from each career stage: a graduate student, a junior faculty member, a senior faculty member.

Second, code everything (“ open coding ”). See what emerges, and don’t limit yourself in any way. You will end up with a ton of codes, many more than you will end up with, but this is an excellent way to not foreclose an interesting finding too early in the analysis. Note the importance of starting with a sample of your collected data, because otherwise, open coding all your data is, frankly, impossible and counterproductive. You will just get stuck in the weeds.

Third, pare down your coding list. Where you may have begun with fifty (or more!) codes, you probably want no more than twenty remaining. Go back through the weeds and pull out everything that does not have the potential to bloom into a nicely shaped garden. Note that you should do this before tackling all of your data . Sometimes, however, you might need to rethink the sample you chose. Let’s say that the graduate student interview brought up some interesting gender issues that were pertinent to female-identifying sociologists, but both the junior and the senior faculty members identified as male. In that case, I might read through and open code at least one other interview transcript, perhaps a female-identifying senior faculty member, before paring down my list of codes.

This is also the time to create a codebook if you are using one, a master guide to the codes you are using, including examples (see Sample Codebooks 1 and 2 ). A codebook is simply a document that lists and describes the codes you are using. It is easy to forget what you meant the first time you penciled a coded notation next to a passage, so the codebook allows you to be clear and consistent with the use of your codes. There is not one correct way to create a codebook, but generally speaking, the codebook should include (1) the code (either name or identification number or both), (2) a description of what the code signifies and when and where it should be applied, and (3) an example of the code to help clarify (2). Listing all the codes down somewhere also allows you to organize and reorganize them, which can be part of the analytical process. It is possible that your twenty remaining codes can be neatly organized into five to seven master “themes.” Codebooks can and should develop as you recursively read through and code your collected material. [3]

Fourth, using the pared-down list of codes (or codebook), read through and code all the data. I know many qualitative researchers who work without a codebook, but it is still a good practice, especially for beginners. At the very least, read through your list of codes before you begin this “ closed coding ” step so that you can minimize the chance of missing a passage or section that needs to be coded. The final step is…to do it all again. Or, at least, do closed coding (step four) again. All of this takes a great deal of time, and you should plan accordingly.

Researcher Note

People often say that qualitative research takes a lot of time. Some say this because qualitative researchers often collect their own data. This part can be time consuming, but to me, it’s the analytical process that takes the most time. I usually read every transcript twice before starting to code, then it usually takes me six rounds of coding until I’m satisfied I’ve thoroughly coded everything. Even after the coding, it usually takes me a year to figure out how to put the analysis together into a coherent argument and to figure out what language to use. Just deciding what name to use for a particular group or idea can take months. Understanding this going in can be helpful so that you know to be patient with yourself.

—Jessi Streib, author of The Power of the Past and Privilege Lost

Note that there is no magic in any of this, nor is there any single “right” way to code or any “correct” codes. What you see in the data will be prompted by your position as a researcher and your scholarly interests. Where the above codes on a preschooler solving a puzzle emerged from my own interest in puzzle solving, another researcher might focus on something wholly different. A scholar of linguistics, for example, may focus instead on the verbalizations made by the child during the discovery process, perhaps even noting particular vocalizations (incidence of grrrs and gritting of the teeth, for example). Your recording of the codes you used is the important part, as it allows other researchers to assess the reliability and validity of your analyses based on those codes. Chapter 19 will provide more details about the kinds of codes you might develop.

Saldaña ( 2014 ) lists seven “necessary personal attributes” for successful coding. To paraphrase, they are the following:

- Having (or practicing) good organizational skills

- Perseverance

- The ability and willingness to deal with ambiguity

- Flexibility

- Creativity, broadly understood, which includes “the ability to think visually, to think symbolically, to think in metaphors, and to think of as many ways as possible to approach a problem” (20)

- Commitment to being rigorously ethical

- Having an extensive vocabulary [4]

Writing Analytic Memos during/after Coding

Coding the data you have collected is only one aspect of analyzing it. Too many beginners have coded their data and then wondered what to do next. Coding is meant to help organize your data so that you can see it more clearly, but it is not itself an analysis. Thinking about the data, reviewing the coded data, and bringing in the previous literature (here is where you use your literature review and theory) to help make sense of what you have collected are all important aspects of data analysis. Analytic memos are notes you write to yourself about the data. They can be short (a single page or even a paragraph) or long (several pages). These memos can themselves be the subject of subsequent analytic memoing as part of the recursive process that is qualitative data analysis.

Short analytic memos are written about impressions you have about the data, what is emerging, and what might be of interest later on. You can write a short memo about a particular code, for example, and why this code seems important and where it might connect to previous literature. For example, I might write a paragraph about a “cultural capital” code that I use whenever a working-class sociologist says anything about “not fitting in” with their peers (e.g., not having the right accent or hairstyle or private school background). I could then write a little bit about Bourdieu, who originated the notion of cultural capital, and try to make some connections between his definition and how I am applying it here. I can also use the memo to raise questions or doubts I have about what I am seeing (e.g., Maybe the type of school belongs somewhere else? Is this really the right code?). Later on, I can incorporate some of this writing into the theory section of my final paper or article. Here are some types of things that might form the basis of a short memo: something you want to remember, something you noticed that was new or different, a reaction you had, a suspicion or hunch that you are developing, a pattern you are noticing, any inferences you are starting to draw. Rubin ( 2021 ) advises, “Always include some quotation or excerpt from your dataset…that set you off on this idea. It’s happened to me so many times—I’ll have a really strong reaction to a piece of data, write down some insight without the original quotation or context, and then [later] have no idea what I was talking about and have no way of recreating my insight because I can’t remember what piece of data made me think this way” ( 203 ).

All CAQDAS programs include spaces for writing, generating, and storing memos. You can link a memo to a particular transcript, for example. But you can just as easily keep a notebook at hand in which you write notes to yourself, if you prefer the more tactile approach. Drawing pictures that illustrate themes and patterns you are beginning to see also works. The point is to write early and write often, as these memos are the building blocks of your eventual final product (chapter 20).

In the next chapter (chapter 19), we will go a little deeper into codes and how to use them to identify patterns and themes in your data. This chapter has given you an idea of the process of data analysis, but there is much yet to learn about the elements of that process!

Qualitative Data-Analysis Samples

The following three passages are examples of how qualitative researchers describe their data-analysis practices. The first, by Harvey, is a useful example of how data analysis can shift the original research questions. The second example, by Thai, shows multiple stages of coding and how these stages build upward to conceptual themes and theorization. The third example, by Lamont, shows a masterful use of a variety of techniques to generate theory.

Example 1: “Look Someone in the Eye” by Peter Francis Harvey ( 2022 )

I entered the field intending to study gender socialization. However, through the iterative process of writing fieldnotes, rereading them, conducting further research, and writing extensive analytic memos, my focus shifted. Abductive analysis encourages the search for unexpected findings in light of existing literature. In my early data collection, fieldnotes, and memoing, classed comportment was unmistakably prominent in both schools. I was surprised by how pervasive this bodily socialization proved to be and further surprised by the discrepancies between the two schools.…I returned to the literature to compare my empirical findings.…To further clarify patterns within my data and to aid the search for disconfirming evidence, I constructed data matrices (Miles, Huberman, and Saldaña 2013). While rereading my fieldnotes, I used ATLAS.ti to code and recode key sections (Miles et al. 2013), punctuating this process with additional analytic memos. ( 2022:1420 )

Example 2:” Policing and Symbolic Control” by Mai Thai ( 2022 )

Conventional to qualitative research, my analyses iterated between theory development and testing. Analytical memos were written throughout the data collection, and my analyses using MAXQDA software helped me develop, confirm, and challenge specific themes.…My early coding scheme which included descriptive codes (e.g., uniform inspection, college trips) and verbatim codes of the common terms used by field site participants (e.g., “never quit,” “ghetto”) led me to conceptualize valorization. Later analyses developed into thematic codes (e.g., good citizens, criminality) and process codes (e.g., valorization, criminalization), which helped refine my arguments. ( 2022:1191–1192 )

Example 3: The Dignity of Working Men by Michèle Lamont ( 2000 )

To analyze the interviews, I summarized them in a 13-page document including socio-demographic information as well as information on the boundary work of the interviewees. To facilitate comparisons, I noted some of the respondents’ answers on grids and summarized these on matrix displays using techniques suggested by Miles and Huberman for standardizing and processing qualitative data. Interviews were also analyzed one by one, with a focus on the criteria that each respondent mobilized for the evaluation of status. Moreover, I located each interviewee on several five-point scales pertaining to the most significant dimensions they used to evaluate status. I also compared individual interviewees with respondents who were similar to and different from them, both within and across samples. Finally, I classified all the transcripts thematically to perform a systematic analysis of all the important themes that appear in the interviews, approaching the latter as data against which theoretical questions can be explored. ( 2000:256–257 )

Sample Codebook 1

This is an abridged version of the codebook used to analyze qualitative responses to a question about how class affects careers in sociology. Note the use of numbers to organize the flow, supplemented by highlighting techniques (e.g., bolding) and subcoding numbers.

01. CAPS: Any reference to “capitals” in the response, even if the specific words are not used

01.1: cultural capital 01.2: social capital 01.3: economic capital

(can be mixed: “0.12”= both cultural and asocial capital; “0.23”= both social and economic)

01. CAPS: a reference to “capitals” in which the specific words are used [ bold : thus, 01.23 means that both social capital and economic capital were mentioned specifically

02. DEBT: discussion of debt

02.1: mentions personal issues around debt 02.2: discusses debt but in the abstract only (e.g., “people with debt have to worry”)

03. FirstP: how the response is positioned

03.1: neutral or abstract response 03.2: discusses self (“I”) 03.3: discusses others (“they”)

Sample Coded Passage:

| “I was really hurt when I didn’t get that scholarship. It was going to cost me thousands of dollars to stay in the program, and I was going to have to borrow all of it. My faculty advisor wasn’t helpful at all. They told | 03.2 |

| me not to worry about it, because it wasn’t really that much money! I almost fell over when they said that! Like, do they not understand what it’s like to be poor? I just felt so isolated then. I was on my own. | 02.1. 01.3 |

| I couldn’t talk to anyone about it, because no one else seemed to worry about it. Talk about economic capital!” |

* Question: What other codes jump out to you here? Shouldn’t there be a code for feelings of loneliness or alienation? What about an emotions code ?

Sample Codebook 2

| CODE | DEFINITION | WHEN TO APPLY | IN VIVO EXAMPLE |

|---|---|---|---|

| ALIENATION | Feeling out of place in academia | Any time uses the word alienation or impostor syndrome or feeling out of place | “I was so lonely in graduate school. It was an alienating experience.” |

| CULTURAL CAPITAL | Knowledge or other cultural resources that affect success in academia | When “cultural capital” is used but also when knowledge or lack of knowledge about cultural things are discussed | “We went to a fancy restaurant after my job interview and I was paralyzed with fear because I did not know which fork I was supposed to be using. Yikes!” |

| SOCIAL CAPITAL | Social networks that advance success in academia | When “social capital” is used but also when social networks are discussed or knowing the right people | “I didn’t know who to turn to. It seemed like everyone else had parents who could help them and I didn’t know anyone else who had ever even gone to college!” |

This is an example that uses "word" categories only, with descriptions and examples for each code

Further Readings

Elliott, Victoria. 2018. “Thinking about the Coding Process in Qualitative Analysis.” Qualitative Report 23(11):2850–2861. Address common questions those new to coding ask, including the use of “counting” and how to shore up reliability.

Friese, Susanne. 2019. Qualitative Data Analysis with ATLAS.ti. 3rd ed. A good guide to ATLAS.ti, arguably the most used CAQDAS program. Organized around a series of “skills training” to get you up to speed.

Jackson, Kristi, and Pat Bazeley. 2019. Qualitative Data Analysis with NVIVO . 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE. If you want to use the CAQDAS program NVivo, this is a good affordable guide to doing so. Includes copious examples, figures, and graphic displays.

LeCompte, Margaret D. 2000. “Analyzing Qualitative Data.” Theory into Practice 39(3):146–154. A very practical and readable guide to the entire coding process, with particular applicability to educational program evaluation/policy analysis.

Miles, Matthew B., and A. Michael Huberman. 1994. Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook . 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE. A classic reference on coding. May now be superseded by Miles, Huberman, and Saldaña (2019).

Miles, Matthew B., A. Michael Huberman, and Johnny Saldaña. 2019. Qualitative Data Analysis: A Methods Sourcebook . 4th ed. Thousand Oaks, CA; SAGE. A practical methods sourcebook for all qualitative researchers at all levels using visual displays and examples. Highly recommended.

Saldaña, Johnny. 2014. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers . 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE. The most complete and comprehensive compendium of coding techniques out there. Essential reference.

Silver, Christina. 2014. Using Software in Qualitative Research: A Step-by-Step Guide. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA; SAGE. If you are unsure which CAQDAS program you are interested in using or want to compare the features and usages of each, this guidebook is quite helpful.

Vogt, W. Paul, Elaine R. Vogt, Diane C. Gardner, and Lynne M. Haeffele2014. Selecting the Right Analyses for Your Data: Quantitative, Qualitative, and Mixed Methods . New York: The Guilford Press. User-friendly reference guide to all forms of analysis; may be particularly helpful for those engaged in mixed-methods research.

- When you have collected content (historical, media, archival) that interests you because of its communicative aspect, content analysis (chapter 17) is appropriate. Whereas content analysis is both a research method and a tool of analysis, coding is a tool of analysis that can be used for all kinds of data to address any number of questions. Content analysis itself includes coding. ↵

- Scientific research, whether quantitative or qualitative, demands we keep an open mind as we conduct our research, that we are “neutral” regarding what is actually there to find. Students who are trained in non-research-based disciplines such as the arts or philosophy or who are (admirably) focused on pursuing social justice can too easily fall into the trap of thinking their job is to “demonstrate” something through the data. That is not the job of a researcher. The job of a researcher is to present (and interpret) findings—things “out there” (even if inside other people’s hearts and minds). One helpful suggestion: when formulating your research question, if you already know the answer (or think you do), scrap that research. Ask a question to which you do not yet know the answer. ↵

- Codebooks are particularly useful for collaborative research so that codes are applied and interpreted similarly. If you are working with a team of researchers, you will want to take extra care that your codebooks remain in synch and that any refinements or developments are shared with fellow coders. You will also want to conduct an “intercoder reliability” check, testing whether the codes you have developed are clearly identifiable so that multiple coders are using them similarly. Messy, unclear codes that can be interpreted differently by different coders will make it much more difficult to identify patterns across the data. ↵

- Note that this is important for creating/denoting new codes. The vocabulary does not need to be in English or any particular language. You can use whatever words or phrases capture what it is you are seeing in the data. ↵

A first-cycle coding process in which gerunds are used to identify conceptual actions, often for the purpose of tracing change and development over time. Widely used in the Grounded Theory approach.

A first-cycle coding process in which terms or phrases used by the participants become the code applied to a particular passage. It is also known as “verbatim coding,” “indigenous coding,” “natural coding,” “emic coding,” and “inductive coding,” depending on the tradition of inquiry of the researcher. It is common in Grounded Theory approaches and has even given its name to one of the primary CAQDAS programs (“NVivo”).

Computer-assisted qualitative data-analysis software. These are software packages that can serve as a repository for qualitative data and that enable coding, memoing, and other tools of data analysis. See chapter 17 for particular recommendations.

The purposeful selection of some data to prove a preexisting expectation or desired point of the researcher where other data exists that would contradict the interpretation offered. Note that it is not cherry picking to select a quote that typifies the main finding of a study, although it would be cherry picking to select a quote that is atypical of a body of interviews and then present it as if it is typical.

A preliminary stage of coding in which the researcher notes particular aspects of interest in the data set and begins creating codes. Later stages of coding refine these preliminary codes. Note: in Grounded Theory , open coding has a more specific meaning and is often called initial coding : data are broken down into substantive codes in a line-by-line manner, and incidents are compared with one another for similarities and differences until the core category is found. See also closed coding .

A set of codes, definitions, and examples used as a guide to help analyze interview data. Codebooks are particularly helpful and necessary when research analysis is shared among members of a research team, as codebooks allow for standardization of shared meanings and code attributions.

The final stages of coding after the refinement of codes has created a complete list or codebook in which all the data is coded using this refined list or codebook. Compare to open coding .

A first-cycle coding process in which emotions and emotionally salient passages are tagged.

Introduction to Qualitative Research Methods Copyright © 2023 by Allison Hurst is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

University Library, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

Qualitative Data Analysis: Coding

- Atlas.ti web

- R for text analysis

- Microsoft Excel & spreadsheets

- Other options

- Planning Qual Data Analysis

- Free Tools for QDA

- QDA with NVivo

- QDA with Atlas.ti

- QDA with MAXQDA

- PKM for QDA

- QDA with Quirkos

- Working Collaboratively

- Qualitative Methods Texts

- Transcription

- Data organization

- Example Publications

- Find Methods Examples

Coding Qualitative Data

Planning your coding strategy.

Coding is a qualitative data analysis strategy in which some aspect of the data is assigned a descriptive label that allows the researcher to identify related content across the data. How you decide to code - or whether to code- your data should be driven by your methodology. But there are rarely step-by-step descriptions, and you'll have to make many decisions about how to code for your own project.

Some questions to consider as you decide how to code your data:

What will you code?

What aspects of your data will you code? If you are not coding all of your available data, how will you decide which elements need to be coded? If you have recordings interviews or focus groups, or other types of multimedia data, will you create transcripts to analyze and code? Or will you code the media itself (see Farley, Duppong & Aitken, 2020 on direct coding of audio recordings rather than transcripts).

Where will your codes come from?

Depending on your methodology, your coding scheme may come from previous research and be applied to your data (deductive). Or you my try to develop codes entirely from the data, ignoring as much as possible, previous knowledge of the topic under study, to develop a scheme grounded in your data (inductive). In practice, however, many practices will fall between these two approaches.

How will you apply your codes to your data?

You may decide to use software to code your qualitative data, to re-purpose other software tools (e.g. Word or spreadsheet software) or work primarily with physical versions of your data. Qualitative software is not strictly necessary, though it does offer some advantages, like:

- Codes can be easily re-labeled, merged, or split. You can also choose to apply multiple coding schemes to the same data, which means you can explore multiple ways of understanding the same data. Your analysis, then, is not limited by how often you are able to work with physical data, such as paper transcripts.

- Most software programs for QDA include the ability to export and import coding schemes. This means you can create a re-use a coding scheme from a previous study, or that was developed in outside of the software, without having to manually create each code.

- Some software for QDA includes the ability to directly code image, video, and audio files. This may mean saving time over creating transcripts. Or, your coding may be enhanced by access to the richness of mediated content, compared to transcripts.

- Using QDA software may also allow you the ability to use auto-coding functions. You may be able to automatically code all of the statements by speaker in a focus group transcript, for example, or identify and code all of the paragraphs that include a specific phrase.

What will be coded?

Will you deploy a line-by-line coding approach, with smaller codes eventually condensed into larger categories or concepts? Or will you start with codes applied to larger segments of the text, perhaps later reviewing the examples to explore and re-code for differences between the segments?

How will you explain the coding process?

- Regardless of how you approach coding, the process should be clearly communicated when you report your research, though this is not always the case (Deterding & Waters, 2021).

- Carefully consider the use of phrases like "themes emerged." This phrasing implies that the themes lay passively in the data, waiting for the researcher to pluck them out. This description leaves little room for describing how the researcher "saw" the themes and decided which were relevant to the study. Ryan and Bernard (2003) offer a terrific guide to ways that you might identify themes in the data, using both your own observations as well as manipulations of the data.

How will you report the results of your coding process?

How you report your coding process should align with the methodology you've chosen. Your methodology may call for careful and consistent application of a coding scheme, with reports of inter-rater reliability and counts of how often a code appears within the data. Or you may use the codes to help develop a rich description of an experience, without needing to indicate precisely how often the code was applied.

How will you code collaboratively?

If you are working with another researcher or a team, your coding process requires careful planning and implementation. You will likely need to have regular conversations about your process, particularly if your goal is to develop and consistently apply a coding scheme across your data.

Coding Features in QDA Software Programs

- Atlas.ti (Mac)

- Atlas.ti (Windows)

- NVivo (Windows)

- NVivo (Mac)

- Coding data See how to create and manage codes and apply codes to segments of the data (known as quotations in Atlas.ti).

- Search and Code Using the search and code feature lets you locate and automatically code data through text search, regular expressions, Named Entity Recognition, and Sentiment Analysis.

- Focus Group Coding Properly prepared focus group documents can be automatically coded by speaker.

- Inter-Coder Agreement Coded text, audio, and video documents can be tested for inter-coder agreement. ICA is not available for images or PDF documents.

- Quotation Reader Once you've coded data, you can view just the data that has been assigned that code.

- Find Redundant Codings (Mac) This tool identifies "overlapping or embedded" quotations that have the same code, that are the result of manual coding or errors when merging project files.

- Coding Data in Atlas.ti (Windows) Demonstrates how to create new codes, manage codes and applying codes to segments of the data (known as quotations in Atlas.ti)

- Search and Code in Atlas.ti (Windows) You can use a text search, regular expressions, Named Entity Recognition, and Sentiment Analysis to identify and automatically code data in Atlas.ti.

- Focus Group Coding in Atlas.ti (Windows) Properly prepared focus group transcripts can be automatically coded by speaker.

- Inter-coder Agreement in Atlas.ti (Windows) Coded text, audio, and video documents can be tested for inter-coder agreement. ICA is not available for images or PDF documents.

- Quotation Reader in Atlas.ti (Windows) Once you've coded data, you can view and export the quotations that have been assigned that code.

- Find Redundant Codings in Atlas.ti (Windows) This tool identifies "overlapping or embedded" quotations that have the same code, that are the result of manual coding or errors when merging project files.

- Coding in NVivo (Windows) This page includes an overview of the coding features in NVivo.

- Automatic Coding in Documents in NVivo (Windows) You can use paragraph formatting styles or speaker names to automatically format documents.

- Coding Comparison Query in NVivo (Windows) You can use the coding comparison feature to compare how different users have coded data in NVivo.

- Review the References in a Node in NVivo (Windows) References are the term that NVivo uses for coded segments of the data. This shows you how to view references related to a code (or any node)

- Text Search Queries in NVivo (Windows) Text queries let you search for specific text in your data. The results of your query can be saved as a node (a form of auto coding).

- Coding Query in NVivo (Windows) Use a coding query to display references from your data for a single code or multiples of codes.

- Code Files and Manage Codes in NVivo (Mac) This page offers an overview of coding features in NVivo. Note that NVivo uses the concept of a node to refer to any structure around which you organize your data. Codes are a type of node, but you may see these terms used interchangeably.

- Automatic Coding in Datasets in NVivo (Mac) A dataset in NVivo is data that is in rows and columns, as in a spreadsheet. If a column is set to be codable, you can also automatically code the data. This approach could be used for coding open-ended survey data.

- Text Search Query in NVivo (Mac) Use the text search query to identify relevant text in your data and automatically code references by saving as a node.

- Review the References in a Node in NVivo (Mac) NVivo uses the term references to refer to data that has been assigned to a code or any node. You can use the reference view to see the data linked to a specific node or combination of nodes.

- Coding Comparison Query in NVivo (Mac) Use the coding comparison query to calculate a measure of inter-rater reliability when you've worked with multiple coders.

The MAXQDA interface is the same across Mac and Windows devices.

- The "Code System" in MAXQDA This section of the manual shows how to create and manage codes in MAXQDA's code system.

- How to Code with MAXQDA

- Display Coded Segments in the Document Browser Once you've coded a document within MAXQDA, you can choose which of those codings will appear on the document, as well as choose whether or not the text is highlighted in the color linked to the code.

- Creative Coding in MAXQDA Use the creative coding feature to explore the relationships between codes in your system. If you develop a new structure to you codes that you like, you can apply the changes to your overall code scheme.

- Text Search in MAXQDA Use a Text Search to identify data that matches your search terms and automatically code the results. You can choose whether to code only the matching results, the sentence the results are in, or the paragraph the results appear in.

- Segment Retrieval in MAXQDA Data that has been coded is considered a segment. Segment retrieval is how you display the segments that match a code or combination of codes. You can use the activation feature to show only the segments from a document group, or that match a document variable.

- Intercorder Agreement in MAXQDA MAXQDA includes the ability to compare coding between two coders on a single project.

- Create Tags in Taguette Taguette uses the term tag to refer to codes. You can create single tags as well as a tag hierarchy using punctuation marks.

- Highlighting in Taguette Select text with a document (a highlight) and apply tags to code data in Taguette.

Useful Resources on Coding

Deterding, N. M., & Waters, M. C. (2021). Flexible coding of in-depth interviews: A twenty-first-century approach. Sociological Methods & Research , 50 (2), 708–739. https://doi.org/10.1177/0049124118799377

Farley, J., Duppong Hurley, K., & Aitken, A. A. (2020). Monitoring implementation in program evaluation with direct audio coding. Evaluation and Program Planning , 83 , 101854. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2020.101854

Ryan, G. W., & Bernard, H. R. (2003). Techniques to identify themes. Field Methods , 15 (1), 85–109. https://doi.org/10.1177/1525822X02239569.

- << Previous: Data organization

- Next: Citations >>

- Last Updated: Jun 6, 2024 9:59 AM

- URL: https://guides.library.illinois.edu/qualitative

A guide to coding qualitative research data

Last updated

12 February 2023

Reviewed by

Short on time? Get an AI generated summary of this article instead

Each time you ask open-ended and free-text questions, you'll end up with numerous free-text responses. When your qualitative data piles up, how do you sift through it to determine what customers value? And how do you turn all the gathered texts into quantifiable and actionable information related to your user's expectations and needs?

Qualitative data can offer significant insights into respondents’ attitudes and behavior. But to distill large volumes of text / conversational data into clear and insightful results can be daunting. One way to resolve this is through qualitative research coding.

Streamline data coding

Use global data tagging systems in Dovetail so everyone analyzing research is speaking the same language

- What is coding in qualitative research?

This is the system of classifying and arranging qualitative data . Coding in qualitative research involves separating a phrase or word and tagging it with a code. The code describes a data group and separates the information into defined categories or themes. Using this system, researchers can find and sort related content.

They can also combine categorized data with other coded data sets for analysis, or analyze it separately. The primary goal of coding qualitative data is to change data into a consistent format in support of research and reporting.

A code can be a phrase or a word that depicts an idea or recurring theme in the data. The code’s label must be intuitive and encapsulate the essence of the researcher's observations or participants' responses. You can generate these codes using two approaches to coding qualitative data: manual coding and automated coding.

- Why is it important to code qualitative data?

By coding qualitative data, it's easier to identify consistency and scale within a set of individual responses. Assigning codes to phrases and words within feedback helps capture what the feedback entails. That way, you can better analyze and understand the outcome of the entire survey.

Researchers use coding and other qualitative data analysis procedures to make data-driven decisions according to customer responses. Coding in customer feedback will help you assess natural themes in the customers’ language. With this, it's easy to interpret and analyze customer satisfaction .

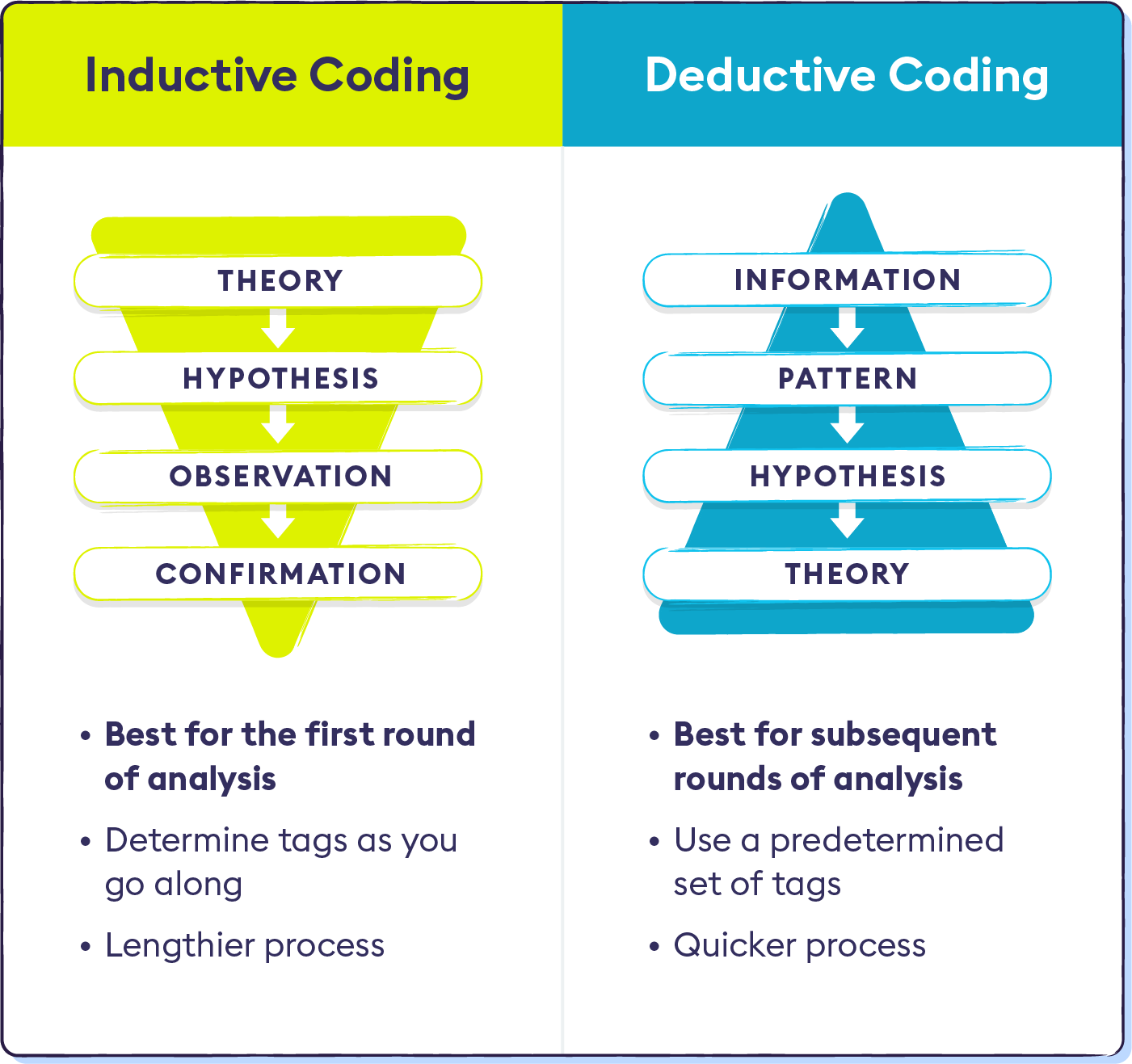

- How do inductive and deductive approaches to qualitative coding work?

Before you start qualitative research coding, you must decide whether you're starting with some predefined code frames, within which the data will be sorted (deductive approach). Or, you may plan to develop and evolve the codes while reviewing the qualitative data generated by the research (inductive approach). A combination of both approaches is also possible.

In most instances, a combined approach will be best. For example, researchers will have some predefined codes/themes they expect to find in the data, but will allow for a degree of discovery in the data where new themes and codes come to light.

Inductive coding

This is an exploratory method in which new data codes and themes are generated by the review of qualitative data. It initiates and generates code according to the source of the data itself. It's ideal for investigative research, in which you devise a new idea, theory, or concept.

Inductive coding is otherwise called open coding. There's no predefined code-frame within inductive coding, as all codes are generated by reviewing the raw qualitative data.

If you're adding a new code, changing a code descriptor, or dividing an existing code in half, ensure you review the wider code frame to determine whether this alteration will impact other feedback codes. Failure to do this may lead to similar responses at various points in the qualitative data, generating different codes while containing similar themes or insights.

Inductive coding is more thorough and takes longer than deductive coding, but offers a more unbiased and comprehensive overview of the themes within your data.

Deductive coding

This is a hierarchical approach to coding. In this method, you develop a codebook using your initial code frames. These frames may depend on an ongoing research theory or questions. Go over the data once again and filter data to different codes.

After generating your qualitative data, your codes must be a match for the code frame you began with. Program evaluation research could use this coding approach.

Inductive and deductive approaches

Research studies usually blend both inductive and deductive coding approaches. For instance, you may use a deductive approach for your initial set of code sets, and later use an inductive approach to generate fresh codes and recalibrate them while you review and analyze your data.

- What are the practical steps for coding qualitative data?

You can code qualitative data in the following ways:

1. Conduct your first-round pass at coding qualitative data

You need to review your data and assign codes to different pieces in this step. You don't have to generate the right codes since you will iterate and evolve them ahead of the second-round coding review.

Let's look at examples of the coding methods you may use in this step.

Open coding : This involves the distilling down of qualitative data into separate, distinct coded elements.

Descriptive coding : In this method, you create a description that encapsulates the data section’s content. Your code name must be a noun or a term that describes what the qualitative data relates to.

Values coding : This technique categorizes qualitative data that relates to the participant's attitudes, beliefs, and values.

Simultaneous coding : You can apply several codes to a single piece of qualitative data using this approach.

Structural coding : In this method, you can classify different parts of your qualitative data based on a predetermined design to perform additional analysis within the design.

In Vivo coding : Use this as the initial code to represent specific phrases or single words generated via a qualitative interview (i.e., specifically what the respondent said).

Process coding : A process of coding which captures action within data. Usually, this will be in the form of gerunds ending in “ing” (e.g., running, searching, reviewing).

2. Arrange your qualitative codes into groups and subcodes

You can start organizing codes into groups once you've completed your initial round of qualitative data coding. There are several ways to arrange these groups.

You can put together codes related to one another or address the same subjects or broad concepts, under each category. Continue working with these groups and rearranging the codes until you develop a framework that aligns with your analysis.

3. Conduct more rounds of qualitative coding

Conduct more iterations of qualitative data coding to review the codes and groups you've already established. You can change the names and codes, combine codes, and re-group the work you've already done during this phase.

In contrast, the initial attempt at data coding may have been hasty and haphazard. But these coding rounds focus on re-analyzing, identifying patterns, and drawing closer to creating concepts and ideas.

Below are a few techniques for qualitative data coding that are often applied in second-round coding.

Pattern coding : To describe a pattern, you join snippets of data, similarly classified under a single umbrella code.

Thematic analysis coding : When examining qualitative data, this method helps to identify patterns or themes.

Selective coding/focused coding : You can generate finished code sets and groups using your first pass of coding.

Theoretical coding : By classifying and arranging codes, theoretical coding allows you to create a theoretical framework's hypothesis. You develop a theory using the codes and groups that have been generated from the qualitative data.

Content analysis coding : This starts with an existing theory or framework and uses qualitative data to either support or expand upon it.

Axial coding : Axial coding allows you to link different codes or groups together. You're looking for connections and linkages between the information you discovered in earlier coding iterations.

Longitudinal coding : In this method, by organizing and systematizing your existing qualitative codes and categories, it is possible to monitor and measure them over time.

Elaborative coding : This involves applying a hypothesis from past research and examining how your present codes and groups relate to it.

4. Integrate codes and groups into your concluding narrative

When you finish going through several rounds of qualitative data coding and applying different forms of coding, use the generated codes and groups to build your final conclusions. The final result of your study could be a collection of findings, theory, or a description, depending on the goal of your study.

Start outlining your hypothesis , observations , and story while citing the codes and groups that served as its foundation. Create your final study results by structuring this data.

- What are the two methods of coding qualitative data?

You can carry out data coding in two ways: automatic and manual. Manual coding involves reading over each comment and manually assigning labels. You'll need to decide if you're using inductive or deductive coding.

Automatic qualitative data analysis uses a branch of computer science known as Natural Language Processing to transform text-based data into a format that computers can comprehend and assess. It's a cutting-edge area of artificial intelligence and machine learning that has the potential to alter how research and insight is designed and delivered.

Although automatic coding is faster than human coding, manual coding still has an edge due to human oversight and limitations in terms of computer power and analysis.

- What are the advantages of qualitative research coding?

Here are the benefits of qualitative research coding:

Boosts validity : gives your data structure and organization to be more certain the conclusions you are drawing from it are valid

Reduces bias : minimizes interpretation biases by forcing the researcher to undertake a systematic review and analysis of the data

Represents participants well : ensures your analysis reflects the views and beliefs of your participant pool and prevents you from overrepresenting the views of any individual or group

Fosters transparency : allows for a logical and systematic assessment of your study by other academics

- What are the challenges of qualitative research coding?

It would be best to consider theoretical and practical limitations while analyzing and interpreting data. Here are the challenges of qualitative research coding:

Labor-intensive: While you can use software for large-scale text management and recording, data analysis is often verified or completed manually.

Lack of reliability: Qualitative research is often criticized due to a lack of transparency and standardization in the coding and analysis process, being subject to a collection of researcher bias.

Limited generalizability : Detailed information on specific contexts is often gathered using small samples. Drawing generalizable findings is challenging even with well-constructed analysis processes as data may need to be more widely gathered to be genuinely representative of attitudes and beliefs within larger populations.

Subjectivity : It is challenging to reproduce qualitative research due to researcher bias in data analysis and interpretation. When analyzing data, the researchers make personal value judgments about what is relevant and what is not. Thus, different people may interpret the same data differently.

- What are the tips for coding qualitative data?

Here are some suggestions for optimizing the value of your qualitative research now that you are familiar with the fundamentals of coding qualitative data.

Keep track of your codes using a codebook or code frame

It can be challenging to recall all your codes offhand as you code more and more data. Keeping track of your codes in a codebook or code frame will keep you organized as you analyze the data. An Excel spreadsheet or word processing document might be your codebook's basic format.

Ensure you track:

The label applied to each code and the time it was first coded or modified

An explanation of the idea or subject matter that the code relates to

Who the original coder is

Any notes on the relationship between the code and other codes in your analysis

Add new codes to your codebook as you code new data, and rearrange categories and themes as necessary.

- How do you create high-quality codes?

Here are four useful tips to help you create high-quality codes.

1. Cover as many survey responses as possible

The code should be generic enough to aid your analysis while remaining general enough to apply to various comments. For instance, "product" is a general code that can apply to many replies but is also ambiguous.

Also, the specific statement, "product stops working after using it for 3 hours" is unlikely to apply to many answers. A good compromise might be "poor product quality" or "short product lifespan."

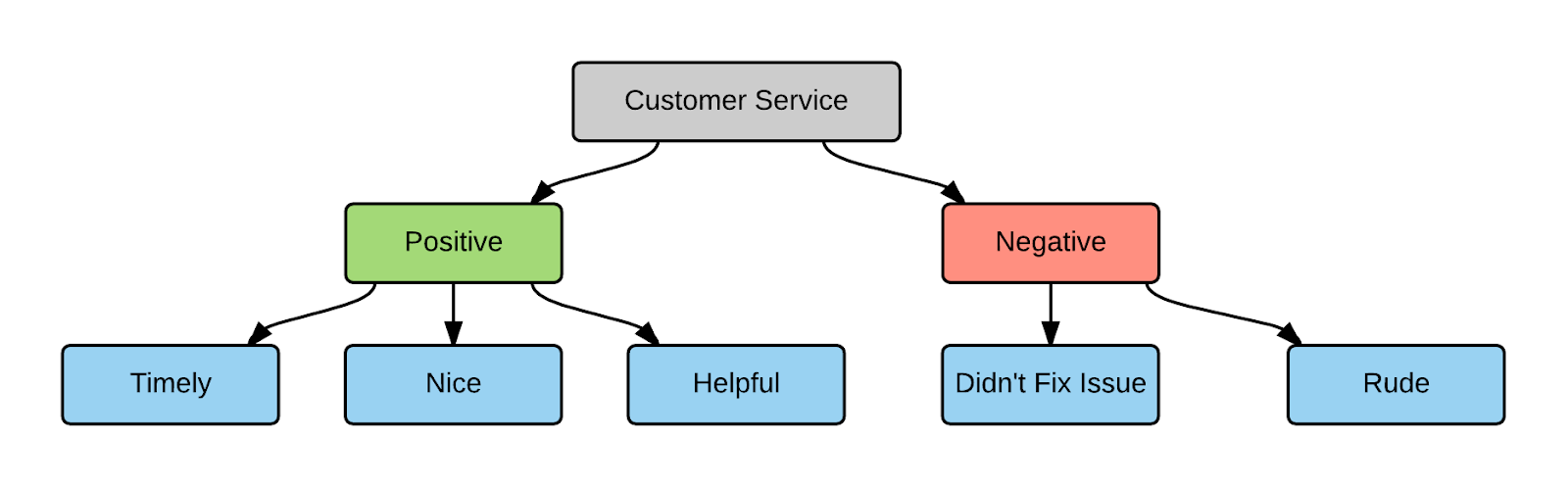

2. Avoid similarities

Having similar codes is acceptable only if they serve different objectives. While "product" and "customer service" differ from each other, "customer support" and "customer service" can be unified into a single code.

3. Take note of the positive and the negative

Establish contrasting codes to track an issue's negative and positive aspects separately. For instance, two codes to identify distinct themes would be "excellent customer service" and "poor customer service."

4. Minimize data—to a point

Try to balance having too many and too few codes in your analysis to make it as useful as possible.

What is the best way to code qualitative data?

Depending on the goal of your research, the procedure of coding qualitative data can vary. But generally, it entails:

Reading through your data

Assigning codes to selected passages

Carrying out several rounds of coding

Grouping codes into themes

Developing interpretations that result in your final research conclusions

You can begin by first coding snippets of text or data to summarize or characterize them and then add your interpretative perspective in the second round of coding.

A few techniques are more or less acceptable depending on your study’s goal; there is no right or incorrect way to code a data set.

What is an example of a code in qualitative research?

A code is, at its most basic level, a label specifying how you should read a text. The phrase, "Pigeons assaulted me and took my meal," is an illustration. You can use pigeons as a code word.

Is there coding in qualitative research?

An essential component of qualitative data analysis is coding. Coding aims to give structure to free-form data so one can systematically study it.

Should you be using a customer insights hub?

Do you want to discover previous research faster?

Do you share your research findings with others?

Do you analyze research data?

Start for free today, add your research, and get to key insights faster

Editor’s picks

Last updated: 18 April 2023

Last updated: 27 February 2023

Last updated: 6 February 2023

Last updated: 6 October 2023

Last updated: 5 February 2023

Last updated: 16 April 2023

Last updated: 7 March 2023

Last updated: 9 March 2023

Last updated: 12 December 2023

Last updated: 11 March 2024

Last updated: 6 March 2024

Last updated: 5 March 2024

Last updated: 13 May 2024

Latest articles

Related topics, .css-je19u9{-webkit-align-items:flex-end;-webkit-box-align:flex-end;-ms-flex-align:flex-end;align-items:flex-end;display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-flex-direction:row;-ms-flex-direction:row;flex-direction:row;-webkit-box-flex-wrap:wrap;-webkit-flex-wrap:wrap;-ms-flex-wrap:wrap;flex-wrap:wrap;-webkit-box-pack:center;-ms-flex-pack:center;-webkit-justify-content:center;justify-content:center;row-gap:0;text-align:center;max-width:671px;}@media (max-width: 1079px){.css-je19u9{max-width:400px;}.css-je19u9>span{white-space:pre;}}@media (max-width: 799px){.css-je19u9{max-width:400px;}.css-je19u9>span{white-space:pre;}} decide what to .css-1kiodld{max-height:56px;display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;}@media (max-width: 1079px){.css-1kiodld{display:none;}} build next, decide what to build next.

Users report unexpectedly high data usage, especially during streaming sessions.

Users find it hard to navigate from the home page to relevant playlists in the app.

It would be great to have a sleep timer feature, especially for bedtime listening.

I need better filters to find the songs or artists I’m looking for.

Log in or sign up

Get started for free

Coding Qualitative Data: A Beginner’s How-To + Examples

When gathering feedback, whether it’s from surveys , online reviews, or social mentions , the most valuable insights usually come from free-form or open-ended responses.

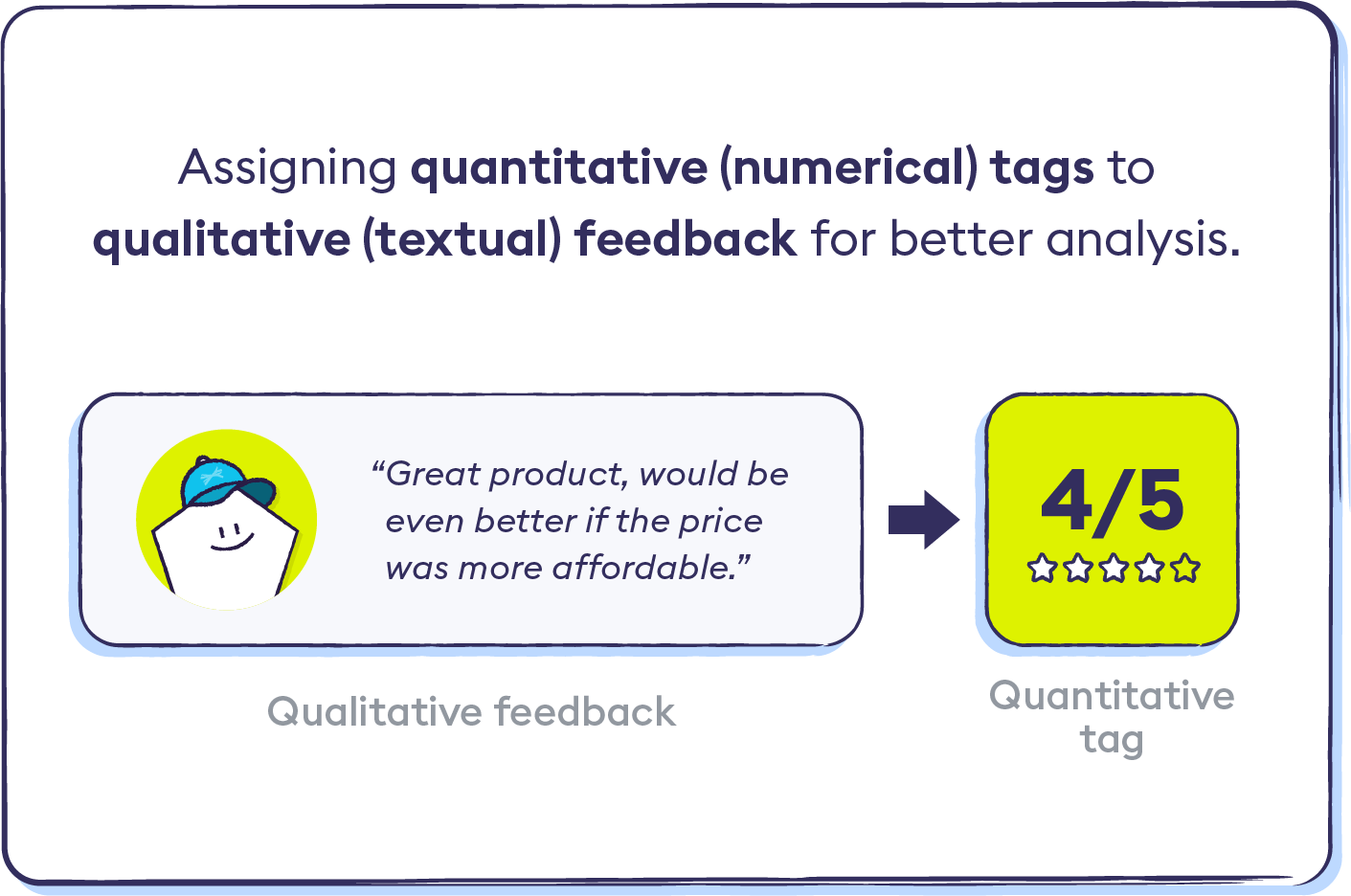

Though these types of responses allow for more detailed feedback, they are also difficult to measure and analyse on a large scale. Coding qualitative data allows you to transform these unique responses into quantitative metrics that can be compared to the rest of your data set.

Read on to learn about this process.

What is Qualitative Data Coding?

Qualitative data coding is the process of assigning quantitative tags to the pieces of data. This is necessary for any type of large-scale analysis because you 1) need to have a consistent way to compare and contrast each piece of qualitative data, and 2) will be able to use tools like Excel and Google Sheets to manipulate quantitative data.

For example, if a customer writes a Yelp review stating “The atmosphere was great for a Friday night, but the food was a bit overpriced,” you can assign quantitative tags based on a scale or sentiment. We’ll get into how exactly to assign these tags in the next section.

Inductive Coding vs Deductive Coding

When deciding how you will scale and code your data, you’ll first have to choose between the inductive or deductive methods. We cover the pros and cons of each method below.

Inductive Coding

Inductive coding is when you don’t already have a set scale or measurement with which to tag the data. If you’re analysing a large amount of qualitative data for the first time, such as the first round of a customer feedback survey, then you will likely need to start with inductive coding since you don’t know exactly what you will be measuring yet.

Inductive coding can be a lengthy process, as you’ll need to comb through your data manually. Luckily, things get easier the second time around when you’re able to use deductive coding.

Deductive Coding

Deductive coding is when you already have a predetermined scale or set of tags that you want to use on your data. This is usually if you’ve already analysed a set of qualitative data with inductive reasoning and want to use the same metrics.

To continue from the example above, say you noticed in the first round that a lot of Yelp reviews mentioned the price of food, and, using inductive coding, you were able to create a scale of 1-5 to measure appetisers, entrees, and desserts.

When analysing new Yelp reviews six months later, you’ll be able to keep the same scale and tag the new responses based on deductive coding, and therefore compare the data to the first round of analysis.

3 Steps for Coding Qualitative Data From the Top-Down

For this section, we will assume that we’re using inductive coding.

1. Start with Broad Categories

The first thing you will want to do is sort your data into broad categories. Think of each of these categories as specific aspects you want to know more about.

To continue with the restaurant example, your categories could include food quality, food price, atmosphere, location, service, etc.

Or for a business in the B2B space, your categories could look something like product quality, product price, customer service, chatbot quality, etc.

2. Assign Emotions or Sentiments

The next step is to then go through each category and assign a sentiment or emotion to each piece of data. In the broadest terms, you can start with just positive emotion and negative emotion.

Remember that when using inductive coding, you’re figuring out your scale and measurements as you go, so you can always start with broad analysis and drill down deeper as you become more familiar with your data.

3. Combine Categories and Sentiments to Draw Conclusions

Once you’ve sorted your data into categories and assigned sentiments, you can start comparing the numbers and drawing conclusions.

For example, perhaps you see that out of the 500 Yelp reviews you’ve analysed, 300 fall into the food price/negative sentiment section of your data. That’s a pretty clear indication that customers think your food is too expensive, and you may see an improvement in customer retention by dropping prices.

The three steps outlined above cover just the very basics of coding qualitative data, so you can understand the theory behind the analysis.

In order to gain more detailed conclusions, you’ll likely need to dig deeper into the data by assigning more complex sentiment tags and breaking down the categories further. We cover some useful tips and a coding qualitative data example below.

4 Tips to Keep in Mind for Accurate Qualitative Data Coding

Here are some helpful reminders to keep on hand when going through the three steps outlined above.

1. Start with a Small Sample of the Data

You’ll want to start with a small sample of your data to make sure the tags you’re using will be applicable to the rest of the set. You don’t want to waste time by going through and manually tagging each piece of data, only to realise at the end that the tags you’ve been using actually aren’t accurate.

Once you’ve broken up your qualitative data into the different categories, choose 10-20% of responses in each category to tag using inductive coding.

Then, continue onto the analysis phase using just that 10-20%.

If you’re able to find takeaways and easily compare the data with that small sample size , then you can continue coding the rest of the data in that same way, adding additional tags where needed.

2. Use Numerical Scales for Deeper Analysis

Instead of just assigning positive and negative sentiments to your data points, you can break this down even further by utilising numerical scales.

Exactly how negative or how positive was the piece of feedback? In the Yelp review example from the beginning of this article, the reviewer stated that the food was “a bit overpriced.” If you’re using a scale of 1-5 to tag the category “food price,” you could tag this as a ⅗ rating.

You’ll likely need to adjust your scales as you work through your initial sample and get a clearer picture of the review landscape.

Having access to more nuanced data like this is important for making accurate decisions about your business.

If you decided to stick with just positive and negative tags, your “food price” category might end up being 50% negative, indicating that a massive change to your pricing structure is needed immediately.

But if it turns out that most of those negative reviews are actually ⅗’s and not ⅕’s, then the situation isn’t as dire as it might have appeared at first glance.

3. Remember That Each Data Point Can Contain Multiple Pieces of Information

Remember that qualitative data can have multiple sentiments and multiple categories (such as the Yelp review example mentioning both atmosphere and price), so you may need to double or even triple-sort some pieces of data.

That’s the beauty of and the struggle with handling open-ended or free-form responses.

However, these responses allow for more accurate insights into your business vs narrow multiple-choice questions.

4. Be Mindful of Having Too Many Tags

Remember, you’re able to draw conclusions from your qualitative data by combining category tags and sentiment tags.

An easy mistake for data analysis newcomers to make is to end up with so many tags that comparing them becomes impossible. This usually stems from an overabundance of caution that you’re tagging responses accurately.

For example, say you’re tagging a review that’s discussing a restaurant host’s behavior. You put it in the category “host/hostess behavior” and tag it as a ⅗ for the sentiment.

Then, you come across another review discussing a server’s behaviour that’s slightly more positive, so you tag this as “server behaviour” for the category and 3.75/5 for the sentiment.

By getting this granular, you’re going to end up with very few data points in the same category and sentiment, which defeats the purpose of coding qualitative data.

In this example, unless you’re very specifically looking at the behaviour of individual restaurant positions, you’re better off tagging both responses as “customer service” for the category and ⅗ for the sentiment for consistency’s sake.

Coding Qualitative Data Example

Below we’ll walk through an example of coding qualitative data, utilising the steps and tips detailed above.

Step 1: Read through your data and define your categories. For this example, we’ll use “customer service,” “product quality,” and “price.”

Step 2: Sort a sample of the data into the above categories. Remember that each data point can be included in multiple categories.

- “This software is amazing, does exactly what I need it to [Product Quality]. However, I do wish they’d stop raising prices every year as it’s starting to get a little out of my budget [Price].”

- “Love the product [Product Quality], but honestly I can’t deal with the terrible customer service anymore [Customer Service]. I’ll be shopping around for a new solution.”

- “Meh, this software is okay [Product Quality] but cheaper competitors [Price] are just as good with much better customer service [Customer Service].”

Step 3: Assign sentiments to the sample. For more in-depth analysis, use a numerical scale. We’ll use 1-5 in this example, with 1 being the lowest satisfaction and 5 being the highest.

- Product Quality:

- “This software is amazing, does exactly what I need it to do” [5/5]

- “Love the product” [5/5]

- “Meh, this software is okay [⅖]

- Customer Service:

- “Honestly I can’t deal with the terrible customer service anymore [⅕]

- “...Much better customer service,” [⅖]

- “However, I do wish they’d stop raising prices every year as it’s starting to get a little out of my budget.” [⅗]

- “Cheaper competitors are just as good.” [⅖]

Step 4: After confirming that the established category and sentiment tags are accurate, continue steps 1-3 for the rest of your data, adding tags where necessary.

Step 5: Identify recurring patterns using data analysis. You can combine your insights with other types of data , like demographic and psychographic customer profiles.

Step 6: Take action based on what you find! For example, you may discover that customers aged 20-30 were the most likely to provide negative feedback on your customer service team, equating to ⅖ or ⅕ on your coding scale. You may be able to conclude that younger customers need a more streamlined way to communicate with your company, perhaps through an automated chatbot service.

Step 7: Repeat this process with more specific research goals in mind to continue digging deeper into what your customers are thinking and feeling . For example, if you uncover the above insight through coding qualitative data from online reviews, you could send out a customer feedback survey specifically asking free-form questions about how your customers would feel interacting with a chatbot instead.

How AI tools help with Coding Qualitative Data

Now that you understand the work that goes into coding qualitative data, you’re probably wondering if there’s an easier solution than manually sorting through every response.

The good news is that, yes, there is. Advanced AI-backed tools are available to help companies quickly and accurately analyse qualitative data at scale, such as customer surveys and online reviews.

These tools can not only code data based on a set of rules you determine, but they can even do their own inductive coding to determine themes and create the most accurate tags as they go.

These capabilities allow business owners to make accurate decisions about their business based on actual data and free up the necessary time and employee bandwidth to act on these insights.

The infographic below gives a visual summary of how to code qualitative data and why it’s essential for businesses to learn how:

Try Chattermill today today to learn how our AI-powered software can help you make smarter business decisions.

Related articles.

The faster horses myth and 3 CX lessons it teaches us

This week we take a look at what we can learn from the quotes attributed to Henry Ford - and the 3 timeless CX fundamentals of success.

Rules Are Made to Be Broken: Modernizing CX Feedback with Advanced AI

5 learnings of (nearly) a decade working with marketplaces

See chattermill in action.

Understand the voice of your customers in realtime with Customer Feedback Analytics from Chattermill.

- AI & NLP

- Churn & Loyalty

- Customer Experience

- Customer Journeys

- Customer Metrics

- Feedback Analysis

- Product Experience

- Product Updates

- Sentiment Analysis

- Surveys & Feedback Collection

- Try Thematic

Welcome to the community

Coding Qualitative Data: How To Guide

How many hours have you spent sitting in front of Excel spreadsheets trying to find new insights from customer feedback?

You know that asking open-ended survey questions gives you more actionable insights than asking your customers for just a numerical Net Promoter Score (NPS) . But when you ask open-ended, free-text questions, you end up with hundreds (or even thousands) of free-text responses.

How can you turn all of that text into quantifiable, applicable information about your customers’ needs and expectations? By coding qualitative data.

In this article, we will cover different coding methods for qualitative data, including both manual and automated approaches, to provide a comprehensive understanding of the techniques used in the first-round pass at coding.

Keep reading to learn:

- What coding qualitative data means (and why it’s important)

- Different methods of coding qualitative data

- How to manually code qualitative data to find significant themes in your data

What is coding in qualitative research?